“The Poorest of the Poor and the Sickest of the Sick”: The Luman Andros Shurtliff Poor Camp Rescue

Wendy Top

Wendy Top, “'The Poorest of the Poor and the Sickest of the Sick': The Luman Andros Shurtliff Poor Camp Rescue,” in Far Away in the West: Reflections on the Mormon Pioneer Trail, edited by Scott C. Esplin, Richard E. Bennett, Susan Easton Black, and Craig K. Manscill (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 81–97.

Wendy Top was an independent historian in Pleasant Grove, Utah when this was written.

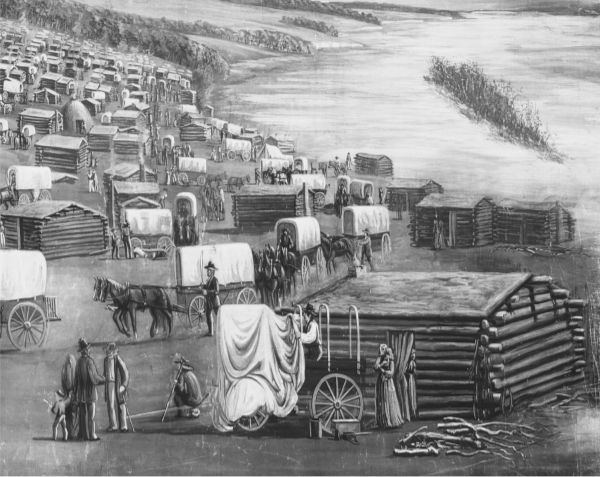

Painting by C. C. A. Christensen courtesy of the Brigham Young University Museum of Art.

Painting by C. C. A. Christensen courtesy of the Brigham Young University Museum of Art.

For most of the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the third and last rescue of the “poor camp” Saints who had been expelled from Nauvoo in the latter half of September 1846 seems to have gone unnoticed. Early sources mentioned the Orville M. Allen rescue team that set out from Winter Quarters to retrieve the poor even before word was received that these last Saints had been driven from Nauvoo at gunpoint. A few more gave additional notice to a second team sent by the Pottawattamie High Council on the eastern side of the Missouri River.[1] But until the sesquicentennial of the exodus it is difficult to find any reference to a third rescue effort sent out by the struggling Latter-day Saints at Garden Grove, Iowa.[2] Even though some information about this rescue has come to light in recent years, it has not yet received the full coverage and credit it deserves. This chapter will analyze the contribution that this rescue party, led by Luman Andros Shurtliff, made to the removal of the poor camp Saints from the Montrose area and why it deserves special mention in the accounts of those rescues.

“Bring a Load of the Poor from Nauvoo”

As early as July 7, 1846, President Brigham Young began to express concern about the poorer Saints who had not yet made the exodus from Nauvoo to the western half of Iowa.[3] Beginning in February of that year, the majority of the Saints had escaped the now-oppressive atmosphere of their once-beloved city. Yet by September, summer was ending, and the most helpless remained in Illinois. Hindered by pervasive sickness and death, poverty, and the inability to sell property and procure equipment and supplies necessary for the long journey, between seven hundred and one thousand beleaguered Saints were left in Nauvoo in September 1846.[4] This number included recent converts who had arrived with no means left to go further. It also included wives of men who had gone to establish themselves in western Iowa and who were supposed to return for their families but had joined the Mormon Battalion instead.[5] A few were widows, left to manage with their families as best they could.[6] On September 7, 1846, President Young suggested to the Winter Quarters High Council the “propriety of taking measures about sending teams to Nauvoo to help up the brethren.” Undoubtedly mindful of the oncoming winter, he added, “and if we send back we must do it immediately.”[7]

Immediate action was difficult at the time. Not only were communication and travel slow but the exiles trying to dig in for the winter at the Missouri River were in little better condition than the Saints on the Mississippi River. It would be a case of the poor and sick rescuing the poorer and sicker. Yet by September 14, 1846, the Saints at Winter Quarters were able to send off a rescue party that included thirty-six yoke of cattle and eleven men headed by Orville M. Allen.[8] The number of wagons involved is unknown, but Brigham Young had also instructed rescuers to take additional teams of oxen for those in Nauvoo who had wagons but no means of drawing them. Young further directed Allen to drop off the Saints he rescued at settlements along the trail but also gave Allen a list of people, including Saints such as clerk Thomas Bullock, whose services were needed at Winter Quarters.

Eleven days after the Allen team’s departure, news reached Winter Quarters of the Battle of Nauvoo and the expulsion of the remaining Saints. The news of the refugees’ pitiful conditions on the west bank of the Mississippi stirred President Brigham Young. On September 27, he and the other leading brethren at Winter Quarters sent a letter to the high council at Council Point on the eastern side of the Missouri, informing them that “the poor brethren and sisters, widows and orphans, sick and destitute, are now lying on the west bank of the Mississippi, waiting for teams, and wagons, and means to remove them.” The statement was followed by this now often-quoted exhortation reminding Church members of the covenant they had made first in Missouri and again in the Nauvoo Temple to sacrifice all they had to help the poor gather with the Saints:

Let the fire of the covenant which you made in the House of the Lord, burn in your hearts, like flame unquenchable, till you, by yourselves or delegates, have searched out every man, within your council limits, who has his arrangements made for the winter, or can leave them for others to make, and impart the fire to his soul, till he shall rise up with his team and go straitway, and bring a load of the poor from Nauvoo, or the river to his own encampment, if they can be provided for there, or to some place in the intermediate country where they can get work, and find shelter for the winter.

The letter concluded, “This is a time of action and not of argument.”[9] There was no time to be lost with another frigid prairie winter looming.

In faithful response, a second rescue team from the eastern side of the Missouri was on the road to Nauvoo shortly after October 2, even though the members on that side of the Missouri River felt they were already giving their all in bearing the support of the families of the Mormon Battalion. James Murdock and Allen Taylor were chosen to lead this company with an unknown number of wagons and teams.

Copies of the letter from Winter Quarters were also to be “sent to Elders Charles C. Rich Mt. Pisgah and Johnson and Fullmer Garden Grove.”[10] We know that the appeal reached Garden Grove because Luman Shurtliff, who was building a home at Garden Grove, begins the account of his rescue with these words: “Just as I finished my home, we got a letter from Brigham Young asking us to go back and bring away the poor Saints on the west bank of the Mississippi, having been driven from Nauvoo at the point of bayonets across the river in September.” The struggling little band of Saints at Garden Grove was able to come up with “18 yoke of oxen and wagons and teamsters.”[11] Though from a much smaller settlement, the response was almost as large as each of the first two companies.[12] It may be that Shurtliff and the Garden Grove Saints were sensitive to the plight of those left behind because they themselves had been left behind at Garden Grove the previous spring due to their own poverty, sickness, and inability to go further west (see note 8). Shurtliff, as one of the leaders of the settlement, was chosen to be captain of the rescue. He reported: “The next morning when we came together to start, 75 cents was all the expense money raised to accomplish a journey of 340 miles.[13] This was the best we could do so we loaded in some squashes and pumpkins for the teams and rolled out, thus equipped to gather home the poor Saints. This was the 18th of October, 1846.”[14] This third group, though seemingly unknown to, or at least unrecorded by, those at Winter Quarters and perhaps even the Pottawattamie High Council, proved to be the salvation of the most destitute of all the Saints.

The First Company Reaches the Poor Camp

Orville Allen and his men from Winter Quarters awakened the stranded, poor Saints in the Montrose, Iowa, area early on the morning of October 7, 1846. Soon after arriving, Allen urged the camp to “yoke up [their] Cows [teams] and make every exertion to get away.”[15] Yet, for many of the sick and destitute, this was easier said than done.

As previously mentioned, Allen had a list of passengers, including their families, to bring back to Winter Quarters. Several of the rescuers with him had come back for their own families and had little or no room in their wagons for others. Thus, many available spots were already taken by those better prepared. Additionally, some of those in the poor camp had their own wagons and were only waiting for teams but were not willing or able to take needy passengers. Clerk Thomas Bullock complained that “some would not carry a Widow with only 250 pounds luggage altho’ they were offered a yoke of Oxen to carry them, they being without.”[16] In the end, Allen’s return company did agree to take three widows, and forty-four of the company’s passengers were described as “sick,”[17] but how many of these were adults who could not fend for themselves is not known. In reality, this company did not rescue many of the sicker and poorer Saints. In fact, Henry Young, one of the inhabitants of the camp, sent a letter to Brigham Young after Allen’s departure, complaining that the wagon train had left the most indigent behind.[18]

Shurtliff later noted in his recollections that “other teams that ware first their had taken those who ware able to travel and had provisions and left those who ware sick and destitute until cooler weather cleansed the atmosphere and the sick began to revive.”[19] Perhaps Orville Allen knew or believed that more rescue teams were on the way. At any rate, the Allen camp left the Mississippi on the afternoon of October 9.[20] A few other Saints joined the Allen train along the way, and clerk Thomas Bullock recorded on October 22 that the departing group consisted of 157 people in 28 wagons.[21]

The Murdock-Taylor Company

The Murdock-Taylor wagon train arrived at the poor camp near the end of October. Undoubtedly this camp of rescuers deserves a great deal of credit, but there is no record of their passengers or of the details of their actual journey. Thomas Bullock, the clerk who was traveling with the Allen company that had departed Montrose on October 9, noted that the second company caught up to and passed them by November 15. Bullock complained that it had taken thirty-seven days for his company to get to the point where they were but only seventeen days for the Murdock-Taylor company to reach the same spot. This would mean that the Murdock-Taylor company had departed the Montrose area as late as October 30, about the time that Shurtliff’s company arrived. Many have supposed that this second rescue team gathered up the rest of the Saints who wanted to leave the poor camp. This may be partly because the Luman Shurtliff account was unknown for so long and partly because of a report made by Bishop Newel K. Whitney to Church leaders at Winter Quarters that fifty wagons would be enough to haul the refugees to safety. Thus historians have estimated the numbers of the poor camp at between three hundred and four hundred people and have assumed that the supposed fifty wagons in the first two companies were sufficient.[22]

The Shurtliff Rescue

Perhaps another reason Shurtliff’s expedition had been overlooked by historians until recent years is that the only detailed record of the events was created by Shurtliff himself many years later.[23] Yet his account evidences all the legendary faith, optimism, and resourcefulness of other accounts of Mormon pioneers. Despite setting out from Garden Grove with so little money and few supplies, he recounts that they “traveled on cheerfully as though we had been rich and plenty of money at our command.” Their provisions and the squash they had brought for their teams ran out twenty miles from Nauvoo, “but there were some Saints living there. They gave us some food,” he recalled. Shurtliff then sent his teamsters out to find work with local farmers to help meet expenses for the return journey. They were all to meet up again at Montrose at the end of October.[24]

Shurtliff proceeded alone toward the Mississippi River. He gave a touching account of seeing Nauvoo again and then continued on his mission. As he traveled up the river from Montrose, he found what was left of the “poor, sick and persecuted Saints.” His description of the besieged refugees echoes that of others who had witnessed their suffering. He observed that most were sick or dying, and for some, “a ragged blanket or quilt laid over a few sticks or brush comprised all the house a whole family owned on earth.” A few had improvised a bed or a meager shelter with boards and were a little better off. Those who were less sick took care of those who were sicker. As he wandered about among “these poor helpless people” he was surprised to hear them tell not of their misery and abuse at the hands of their tormentors but of their deep gratitude that God had delivered them from “disease, death and starvation.”[25]

Though they rejoiced in their blessings, they were the most disadvantaged and immobile of the stranded Saints. Unlike those before him, Shurtliff seemed determined not to leave behind those who were unable to travel.[26] He realized that he was their last hope for the season and resolved to do just that. “I spent the first day in learning their circumstances and ascertaining who it was my duty to take away as I could not take them all and I learned that we were the last company that could be there this fall,” he recollected. “I made up my mind to take the poorest of the poor and the sickest of the sick and only take well ones enough to care for the sick and cook for the company.[27]

At least one of those who may have been well enough to care for the sick was Abigail Smith Abbott Brown, whose own brief account of leaving Nauvoo verifies that Luman Shurtliff led a third rescue company. Abigail, widowed earlier, had recently become one of Captain James Brown’s wives. Brown had departed in the spring exodus, leaving Abigail in Nauvoo with the intention of sending for her as soon as he had established himself. Instead, he joined the Mormon Battalion and counted on others to bring her along. In later years she recounted that she “started for garden Grove with the Widow Holister and 2 Daughters and 4 of my youngest Children to one Waggon with all of our effects under the direction of Br Luman Shirtliff as Capt. The Camp proceeded on their journey. I walked, I supposed, nearly half of the way.”[28]

The next day, as if to emphasize the great sacrifice he and those in his company were making, Shurtliff crossed over the river for one last look at his “to me lovely City of Joseph.”[29] He inspected the evidence and damage of the recent battle that scarred the once-peaceful refuge of the Saints. He visited his home and the grave of his first wife and one of their children. He paid his last respects to them and to the mostly empty city and then turned his back on his past and went forward with his duty. “When I had satisfied my feelings,” he wrote, “I crossed the river into Iowa, and spent the next day helping those families I intended to take west.”

Luman Shurtliff’s account of the rescue’s return journey is a narrative underscored by the certainty that God led them along by small miracles. “In this journey the hand of God was manifest to all who was acquainted with the circumstances,” he declared.[30] In keeping with this testimony that the Lord prospered his company, Shurtliff included several illustrative incidents in his account. Some of these events took place as the camp prepared to depart. For instance, on October 30, the other teamsters met up with Shurtliff at Montrose. According to Shurtliff, one of the teamsters had accidentally shot one of his own oxen. Trying to make the best of it, the teamster dressed the meat for food but was still short one ox for his team. While the men debated what to do, a steamboat landed nearby. Shurtliff directed the teamster to sell three-fourths of the beef to the passengers and then buy a new ox with the proceeds. The plan was not only successful but they were able to sell the hide as well and buy a barrel to put the meat in for salting.[31]

Other provisions for the journey were also forthcoming. The three trustees in Nauvoo were busy helping both Shurtliff’s party and other dependent Saints to get away from Nauvoo. At the request of the trustees, Shurtliff agreed to add two sick widows and their children, some of whom were also sick, to his party. In return, the trustees agreed to provide a wagon and some provisions. Accordingly, they sent a prairie schooner and two barrels of flour. Shurtliff placed the two barrels of flour into the middle of the huge wagon. He then loaded the sick widows on beds at each end along with their children and belongings.[32]

Another seemingly minor incident occurred before departure that later proved providential. In the evening after the wagons were loaded, a young man approached Shurtliff and asked if he and his wife could have their large trunk and some blankets carried in one of the wagons. In return, they would walk the whole distance and give their last ten dollars to the company. Shurtliff “took pity on them” and accepted their offer because he “saw in this the hand of God and told [the young man] if he could put up with us, we would try to with them.” And then he added, “I felt that we should need this money.”[33]

Though things seemed to be falling into place, the successful outcome of the rescue was far from certain. On the last day of October 1846, nearly sixty people, most of them sick, and their meager belongings were loaded into the company’s wagons. In his reminiscences, Shurtliff recalled the concerns he felt as they left the riverbank on November 1: “All the provisions put together would have made only one good meal and we were now about to start in November with this poor sick company on a journey of 170 miles through an uncivilized and mostly uninhabited wilderness. I felt like crying, ‘O, God, help us’ as we left.” When he turned around for one last look at the sad scene, he saw “a few weeping Saints” left standing on the riverbank and thought, “How [they would] live through the winter I knew not, but God knew.” [34] Despite these apprehensions, Shurtliff comforted himself with the thought that God had three faithful trustees in Nauvoo who would take care of the remaining Saints.[35]

The Return Journey

Even as the Shurtliff wagon train began its return journey to Garden Grove, another unexpected opportunity to provide for the company presented itself. Shurtliff remembered a written order for tithing he had received while still living in Nauvoo. It had come from a man who was now an “apostate elder” living only four miles west of Montrose. The chances of collecting on the note seemed “naturally a dull show” to Shurtliff, but, calling upon his personal faith, he determined to make the attempt: “I asked God to have mercy on me and these few poor, afflicted Saints, and touch the heart of the man who I was now about to visit and prepare the way that I might obtain something for the good of the camp.” Approaching the apostate at his home and handing him the note, Shurtliff explained that his party needed help. The man was sympathetic after all and asked what was needed. Shurtliff replied, “Anything that these poor Saints can use.” When the man offered some white beans, Shurtliff told him that would be “first rate” and jubilantly added, “I could but exclaim when I left him, ‘God bless you.’ ”[36]

The suffering Saints whom Shurtliff had rescued likewise shared his simple but certain faith: “The first night in camp our souls actually rejoiced like the children of Israel after their deliverance from the Egyptians,” he remembered. “We had prayers morning and evening, and the Lord blessed us.”[37] Shurtliff records one more incident in which their faith seemed efficacious. As the rescue party followed the trail cut by previous Mormon pioneers, they came across a member of the Church who had stopped on his way and put in a late crop of several acres of corn. Wanting to move further west immediately, this brother willingly sold the crop to Shurtliff and his group.[38] Shurtliff remarked, “We now saw the benefit of the money we got in Montrose for fetching the young man’s trunk.”[39]

Thus it was through these small but seemingly providential incidents that Shurtliff’s company of poor Saints survived day by day and even prospered. Shurtliff makes no mention of major difficulties but does add an amusing incident that illustrates the good humor of the party despite their destitute circumstances:

We got along well together except the two widows in the schooner. They and their teamster made some sport. As before stated, the widows were both sick and could not sit up and several of their children were also sick. Their beds were made with their heads to each end of the wagon and their feet against the flour barrels, and as they could not get out to exercise m[uch], their children would get to play together, and like other children, got at variance when the mothers would take the children’s part. And when this took place the teamster would strike in and sing as he said to dround the noise. Sometimes the women would get so engaged as to try their strength on each other’s hair, then the teamster would shout at the top of his voice, “Captain Shirtliff, come quick! The Women are at play. Come quick!” But by the time I could get their, all would be still and quiet, so we had somethings to amuse us as well as some other.[40]

In such spirits and with a keen awareness of the hand of God upon their venture, the group concluded their journey. “We arrived in Garden Grove, November 15, 1846. In 30 days we had accomplished a journey of 340 miles without [means], except the Lord had furnished [al]most without exertion on our part,” wrote Shurtliff. And then he noted what he might have considered the most important miracle of all: “Our teams looked well. The teamsters had no sickness and the sick we brought were on the gain except one sister who died soon after we arrived.[41] . . . I had twice the money I had when we left. I also had beef, flour, corn, salt, and cotton yarn to devide among the needy Saints.”[42]

Contributions of the Shurtliff Rescue

Luman Shurtliff and his fellow rescuers had relied on their pioneer faith as they cheerily set out from Garden Grove, leaving their marginally established families behind them. Their confidence seemed to grow even as they progressed along their journey. With a certainty that God was guiding them, they had helped the “poorest of the poor and the sickest of the sick.” In the September 28 letter calling for rescue teams, Brigham Young had promised that those like Shurtliff who responded “shall prosper, and the blessings of those ready to perish shall rest upon their heads.”[43] According to his account, Luman Shurtliff certainly felt this was the case, perhaps even the more so because he and his cohorts had been willing to save those least able to help themselves.

The Shurtliff story is another legacy of faith that should be added to the telling of the poor camp rescue and the storied lore of Latter-day Saint faith and sacrifice. Yet it is not merely faith promoting. Its contributions included not only the temporal salvation of the most destitute Saints but also an exclamation point to the larger lessons of the poor camp itself.[44] Surely the plight of the poor Saints was weighing heavily upon Brigham Young as he contemplated moving the entire body of the Church to the West. Indeed, in January of 1847, President Young received specific instructions by revelation that “each company [should] bear an equal proportion, according to the dividend of their property, in taking the poor, the widows, the fatherless, and the families of those who have gone into the army, that the cries of the widow and the fatherless come not up into the ears of the Lord against this people” (D&C 136:8). These instructions confirmed the admonition Brigham had originally given to the rescue teams to “be as fathers to the poor . . . and not leave them till they are comfortably situated.”[45] Surely he was now determined to avoid yet another debacle of suffering and destitution like that which befell the poor camp at Nauvoo.[46]

Notes

[1] Richard E. Bennett referred to the second team as being “heretofore little known.” Bennett, “Eastward to Eden: The Nauvoo Rescue Missions,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 19, no. 4 (Winter 1986): 105. See also Church History in the Fulness of Times (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1993), 318.

[2] Other than a brief reference to the rescue in the obituary of Luman Shurtliff in the Ogden Standard-Examiner (Journal History of the Church, August 26, 1884, 5, in the Selected Collections from the Archives of the Church, Harold B. Lee Library online database), the earliest reference I have found is David R. Crockett, “Cattle Driven North for the Winter,” Church News, October 26, 1996. http://

[3] Church Historian’s Office, “History of the Church, 1839–circa 1882,” 16:32, in the Selected Collections from the Archives of the Church, Harold B. Lee Library online database.

[4] On August 31, 1846, Nauvoo trustees estimated that there were 750 adults left in the city, though many were in process of leaving. Richard E. Bennett, Mormons at the Missouri: Winter Quarters, 1846–1852 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004), 268. William G. Hartley estimates seven hundred to one thousand in “The Pioneer Trek,” 40.

[5] Abigail Smith Abbott to Brigham Young, June 28, 1852, correspondence, as quoted in “I Trusted God and Improved Every Opportunity: Abigail Smith Abbott (1806–1889),” Women of Faith in the Latter Days, 1775–1820, ed. Richard E. Turley Jr. and Brittany A. Chapman (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 1:10–11.

[6] Thomas Bullock journals, 1843–1849, October 8, 1846, microfilm, Church History Library. See also Wayne Stout, “Asenath Slafter Janes,” biographical sketch, 47, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[7] Winter Quarters Municipal High Council Minutes 1846–1848, September 7, 1846 in the Selected Collections from the Archives of the Church, Harold B. Lee Library online database.

The original spelling has been retained in all quotes in this paper.

[8] Orville M. Allen, journal, 1, Church History Library, microfilm. Some historians have estimated that twenty-five wagons set out with this group and about the same number went with the second group, but there is no actual record. These estimates seem to be based on the letter from Bishop Newel K. Whitney that suggested to leaders at Winter Quarters that fifty wagons would be enough to rescue those left on the west bank of the Mississippi, though this letter was not received until October 6, after the first two companies had left. Journal History of the Church, October 6, 1846, 1, Church History Library.

[9] Journal History of the Church, September 28, 1846, 5, in the Selected Collections from the Archives of the Church, Harold B. Lee Library online database.

[10] Journal History of the Church, September 28, 1846, 3.

[11] Biographical Sketch of the Life of Luman Andros Shurtliff, 1807–1864, typescript condensed from journals, 47, microfilm, Church History Library (hereafter referred to as Biographical Sketch). Shurtliff gives the departure date as October 15 in another account found in Luman A. Shurtliff, journal, 1841 May–1856 April, 245, microfilm, Church History Library.

[12] See Orville M. Allen, journal, 1, microfilm, Church History Library. See also explanation in footnote 8.

[13] This was the shortest of the three rescue missions.

[14] Biographical Sketch, 47.

[15] Thomas Bullock journals, October 9, 1846.

[16] Thomas Bullock journals, October 9, 1846.

[17] Bennett, “Eastward to Eden: The Nauvoo Rescue Missions,” 105.

[18] Henry Young to Brigham Young, October 27, 1846, as quoted in Bennett, “Eastward to Eden: The Nauvoo Rescue Missions,” 105.

[19] Luman A. Shurtliff, journal, 1841 May–1856 April, 245, microfilm, Church History Library; original spellings preserved.

[20] Thomas Bullock journals, October 9, 1846. This is the same day that several huge flocks of quail miraculously flew into the poor camp and were caught alive and feasted on throughout the day. Between the rescue and the miracle, the poor camp was sustained for another day and may have felt reassured that God had not forgotten them.

[21] Thomas Bullock journals.

[22] Though Luman Shurtliff carried away only about sixty more Saints, he also made mention of “a few weeping Saints left behind.” Luman Andros Shurtliff autobiography, circa 1852–1876, 323, microfilm, Church History Library. On November 4, 1846 (right after Shurtliff left), the Nauvoo trustees sent a letter to Brigham Young telling him that some twenty families remained on the west bank but that the trustees could take care of them. However, they also acknowledged that Nauvoo trustee Almon Babbitt had sent some wagons back empty. See Journal History of the Church, November 11, 1846, 2–3. Some historians have taken issue with the 640 sufferers estimated by Thomas L. Kane, the great friend of the Saints who also came upon the scene of destitution during the last week of September. They may not have taken into account the fluidity of the situation. Thomas Bullock reported on October 2 (after Kane’s visit) that “The brethren kept moving away from the River side to different places as fast as they can.” See Thomas Bullock journals. Several went to nearby towns to live and work until they had the means to move on and some made their way to Mormon settlements in western Iowa. It is also possible that some left the camp and then returned. On October 4, Bullock walked through the camp and counted eight wagons and seventeen tents. See Thomas Bullock journals. This may not have included the many Saints who had no shelter at all according to Kane and other observers. Also, Bishop Whitney may have taken teamless wagons that were already in the camp into account when suggesting that fifty wagons would suffice to bring the poor west.

[23] His account was written circa 1873.

[24] Biographical Sketch, 47.

[25] Biographical Sketch, 47. This would undoubtedly include the miracle of the quail. See note 20.

[26] In fairness to the Murdock-Taylor company that had just left, maybe they had taken as many of the sick and poor as they could, or perhaps they knew that another train of wagons was on the trail and had left the neediest in hopes that they would soon be in better condition for travel.

[27] Biographical Sketch, 47.

[28] Abigail Smith Abbott to Brigham Young, June 28, 1852, as quoted in “I Trusted God,” 1:10–11.

[29] Shurtliff autobiography, 324.

[30] Shurtliff autobiography, 327.

[31] Biographical Sketch, 47.

[32] Shurtliff autobiography, 323.

[33] Shurtliff autobiography, 323.

[34] Luman A. Shurtliff, journal, 1841 May–1856 April, 245. Asenath Janes (see note 6), another widowed member of the company, confirmed this date as well, although Abigail Brown later states that the company started out on November 3. See Abigail Smith Abbott to Brigham Young, June 28, 1852, as quoted in “I Trusted God,” 1:10–11.

[35] Shurtliff autobiography, 323–24.

[36] Shurtliff autobiography, 324.

[37] Biographical Sketch, 47.

[38] Shurtliff records, “The women kept camp and shucked and shelled corn. The men and boys that were able picked and drawed corn and at daylight we had our corn all in our wagons, and ready to start as early as usual.” Shurtliff autobiography, 325. This detail coincides with Abigail Brown’s account. She recalled, “Suffice it to say I traveled what I could through the Day and at Night prepared for the next day and guarded my wagon, and Husked Corn at Night.” Abigail Smith Abbott to Brigham Young, June 28, 1852, as quoted in “I Trusted God,” 1:10–11.

[39] Shurtliff autobiography, 325.

[40] Shurtliff autobiography, 326–326.

[41] This sister was most likely Harriet Nixon, my third-great-grandmother. She had given birth to her seventh child in July of 1846 and was too sick to leave Nauvoo. She and her family were forced out of Nauvoo at gunpoint and became part of the poor camp. Her death was later recorded by clerk Thomas Bullock at the request of her husband, Stephen: “Harriet Nixon wife of Stephen—died at Garden Grove Nov. 14, 1846.” Historian’s Office of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Subject File-LC, “Temple Ordinances Sealings—Wives to Husbands 9 Feb. 1847–6 May 1849 Adoptions—29 Mar. 1847–2 Mar 1849.” See also Sealing Record B, 804. Stephen Nixon probably confused the date. Luman Shurtliff also gave conflicting information in his accounts about exactly when the death occurred.

[42] Shurtliff autobiography, 327.

[43] Journal History of the Church, September 28, 1846, 6.

[44] See Mark Brown, “Providing in the Lord’s Way, Part 1,” By Common Consent, http://

[45] Journal History of the Church, September 27, 1846, 6.

[46] President Young took this divine directive seriously. In September 1847 when he met the emigrant company of the Saints in Wyoming on his return trip from the Salt Lake Valley, he was very unhappy to discover that his well-laid plans for them had been upended. He pointedly rebuked company leader Parley P. Pratt in front of the Quorum of the Twelve and later John Taylor because they had changed the organization he and the other Apostles had spent the winter putting in place according to the revelation. Pratt and Taylor, perhaps with good reason, had permitted the company to become much larger than planned and top heavy with the more prepared Saints who didn’t want to remain behind. As a result, too many of the poor, widows, and Battalion families had been left at Winter Quarters. See Terryl L. Givens and Matthew J. Grow, Parley P. Pratt: The Apostle Paul of Mormonism (New York City: Oxford University Press, 2011), 269.