“The Place Which God for Us Prepared”: Presettlement Wasatch Range Environment

Terry B. Ball and Spencer S. Snyder

Terry B. Ball and Spencer S. Snyder, “'The Place Which God for Us Prepared': Presettlement Wasatch Range Environment,” in Far Away in the West: Reflections on the Mormon Pioneer Trail, edited by Scott C. Esplin, Richard E. Bennett, Susan Easton Black, and Craig K. Manscill (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 99–133.

Terry B. Ball was a professor of ancient scripture, Brigham Young University when this was written.

Spencer S. Snyder was pursuing a master of health administration degree at Virginia Commonwealth University when this was written.

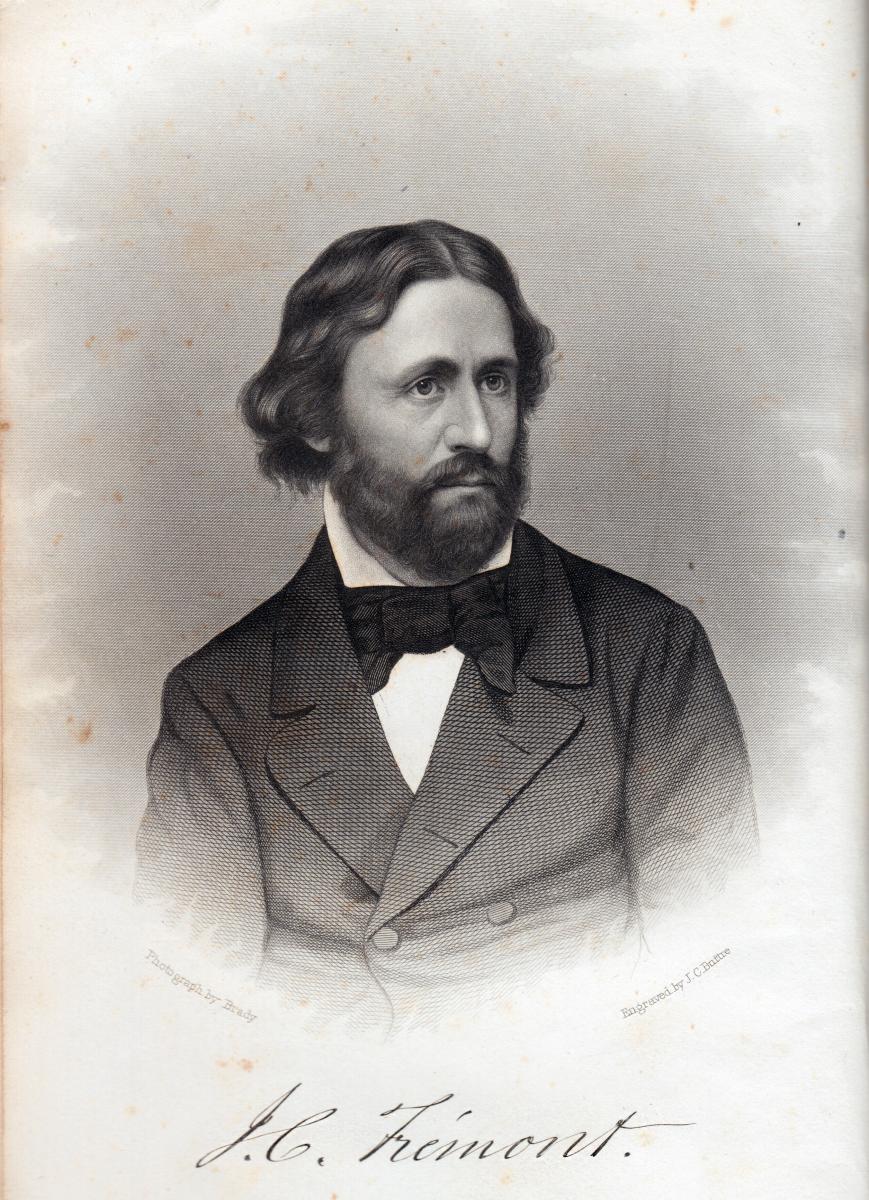

Steel engraving taken from a photograph by Mathew Brady in 1856.

Steel engraving taken from a photograph by Mathew Brady in 1856.

The Latter-day Saints’ flight from Nauvoo in the winter of 1845–46 shares some similarities with the biblical account of the exodus of the Israelites out of Egypt. Each saw themselves as an oppressed, prophet-led covenant people fleeing through a wilderness in hopes of finding peace and refuge in a promised land. But while the Israelites’ God assured them that their new home would be “a land flowing with milk and honey” (Exodus 3:8), as the Latter-day Saints headed out from Nauvoo, they seem to have been less certain about what they would find in their new home or even of its exact location. They had a general sense that they were headed for the Rocky Mountains, and by the time they had reached the Missouri River, their leaders appear to have understood that they would settle on the western side of the mountains in what is today known as the Wasatch Range[1] around the Great Salt Lake or the Bear River Valley.[2]

What they knew of the ecology and environment of their destination was primarily secondhand and sometimes conflicting. Perhaps they wondered if their promised land would also be one “flowing with milk and honey.”[3] They likely would not have been encouraged by a reported exchange between Brigham Young and the famous trapper Jim Bridger that occurred between the crossings of the Little Sandy and Big Sandy Rivers in June of 1847. President Young later recalled, “When we met Mr. Bridger on the Big Sandy River, said he, ‘Mr. Young, I would give a thousand dollars if I knew an ear of corn could be ripened in the Great Basin.’ Said I, ‘Wait eighteen months and I will show you many of them.’ Did I say this from knowledge? No, it was my faith; but we had not the least encouragement—from natural reasoning and all that we could learn of this country—of its sterility, its cold and frost, to believe that we could ever raise anything.”[4] Later generations of Latter-day Saints who have lived in the prosperous and productive Wasatch Range communities have delighted in recalling the story of Bridger’s wager and have seen evidence of divine providence as well as a testament of the faith, industry, and genius of their forefathers in proving Bridger wrong.[5]

Today, Latter-day Saints often view the success of those early pioneers as a fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy that the desert would “blossom as the rose” (Isaiah 35:1).[6] Such observations raise some intriguing questions: What was the Wasatch Range portion of the Great Basin really like before the early Saints settled in it? Was it a forbidding and desolate waste or a land ready to settle and make productive? Did it have any capacity to sustain life, or could only God’s intervention make it habitable? Was the land so destitute that no one else wanted it, or did others see its potential?

Some answers to these questions can be found in the writings of explorers and trappers who traveled through the Great Basin before the Latter-day Saints arrived. From their correspondence, diaries, and journals, we will show that although settling the land presented some challenges for a people unfamiliar with its ecology, the Wasatch Range was a resource-rich environment that provided well for the early Saints. It fulfilled the hope expressed in their exodus song, “We'll find the place which God for us prepared.”[7]

Dominguez-Escalante Expedition

Padre Francisco Silvestre Vélez de Escalante provided one of the earliest records of explorers traveling through the Wasatch Range.[8] Escalante was the designated recorder for a 1776 expedition led by Padre Francisco Atanasio Dominguez that was seeking to find an overland route from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to Monterey, California. They also were interested in identifying areas for future settlement along the way. The expedition failed to find the route to California they were seeking, but Escalante’s daily journal succeeds in providing glimpses into the settlement potential of the Wasatch Range.

The Dominguez-Escalante expedition appears to have entered Utah around September 12 of 1776 near modern-day Jensen and Vernal. They followed Cliff Creek westward to the Green River, followed it southwest to the Duchesne River where they turned west crossing over into the Strawberry Valley, then into the Diamond Fork drainage, down to Spanish Fork Canyon, and out into Utah Valley. At Utah Valley they headed primarily south, roughly following the current route of Interstate 15 for much of the way, passing through Utah’s Black Rock and Escalante Deserts and exiting the state near the Virgin River in late October.[9]

Along the way Escalante noted “an abundance of good pasturage” in the Green River Valley and “good land for farming with the help of irrigation.”[10] At the confluence of Brush Creek and Ashley Creek, Escalante observed that “from both of them irrigation ditches could be dug for watering the land on this side, which is likewise good for farming.”[11] Escalante mentioned that while his party followed the Duchesne River they encountered bison, camped by poplar groves, were forced to fight through “impenetrable” willow thickets and “marshy estuaries,” and trekked across stretches of sagebrush and prickly pear cactus.[12] Speaking of the upper and lower Duchesne Rivers and the Lake Fork River, Escalante recorded; “There is good land along these three rivers that we crossed today, and plenty of it for farming with the aid of irrigation—beautiful poplar groves, fine pastures, timber and firewood not too far away,” enough “for three good settlements.”[13]

Entering the Strawberry Valley, they came to Trout Creek, which is now largely submerged under Strawberry Reservoir. Escalante described the creek as “a medium-sized river in which good trout breed in abundance, two of which Joaquin the Laguna[14] killed with arrows and caught, and each one must have weighed more than two pounds. This river runs southeast along a very pleasant valley with good pasturages, many springs, and beautiful groves of not very tall or thick white poplars. In it there are all the conveniences required for a settlement.”[15]

The expedition’s passage from the Strawberry Valley over to the Spanish Fork River Valley and out into Utah Valley was especially arduous. Escalante speaks of passing through dense forests and “impenetrable swaths” of white poplar, scrub oak, chokecherry, and spruce, some so thick it was difficult for their loaded pack animals to break through.[16] Their relief at finally reaching the more open terrain of Utah Valley is perhaps reflected in the names they gave the region. They named Utah Valley “Our Lady of Mercy of the Timpanogotzis,”[17] and they called the valley meadow where they camped the first day “The Plain of the Most Sweet Name of Jesus.”[18]

In the valley, they observed recently burned meadows and surmised they had been burnt by the American Indians living in the valley to discourage the party from staying, but they also noted that the bottomland meadows were too large and extensive for the effort to be successful “even though they had started many fires.”[19] Escalante was impressed with the wide expanse of the valley, estimating it to be forty-two miles long and from twenty-six to thirty-two miles wide and describing it as “flat and, with the exception of the marshes along the lake’s edges, of very good farmland quality for all kinds of crops.”[20] He spoke specifically of four rivers in the valley and gave a lengthy description of its potential for settlement:

Of the four rivers which water it, the first one toward the south [Spanish Fork River] is the one of hot waters upon the spreading meadows, where there is sufficient irrigable land for two good settlements. The second one [Hobble Creek or Dry Creek], flowing three leagues northward away from the first one and having more water than it has, can sustain a good large settlement or two medium sized ones, all with an abundance of irrigable lands. This one splits into two branches ahead of the lake; on its banks are large alder trees besides the poplars. We named it Río de San Nicolás. Three leagues and a half northwest from this one is the third [Provo River], the area in between, consisting of flat meadows with good land for farming; it carries more water than the foregoing two, has a larger poplar grove and meadows of good soil which can be irrigated—all good for two or even three good settlements. . . . We did not get to the fourth river [American Fork River], although we made out its poplar grove. It lies northwest from that of San Antonio and has a great deal of level land extending in this direction, and good soil from what we saw. They told us that it carried as much water as the others, and hence some towns could be established on it. We named it Río de Santa Ana. Besides these rivers, there are many small outlets of good water in the bottomland, and several small springs which come down from the sierra. What we have finished saying concerning the settlements is to be understood as giving each one more land than it exactly needs. For if each town took only one league of farmland, as many Indian pueblos can fit inside the valley as there are those in New Mexico—because, even if along its upper reaches we give it the aforesaid measurements (which actually are greater), along the southern and other sides it has very ample nooks, and all consisting of good land. All over it there are good and very abundant pasturages, and in some sections it produces flax and hemp in such abundance that it seems as though it had been planted purposely. And the climate here is a good one, for after having experienced cold aplenty since we left El Río de San Buenaventura [Green River], we felt warm throughout the entire valley by day and by night. Over and above these finest of advantages, it has plenty of firewood and timber in the adjacent sierra which surrounds it—many sheltered spots, waters, and pasturages, for raising cattle and sheep and horses. This applies along the north, the northeast, and the eastern and southeastern sides. Adjacent along the south and southwest it has two other extensive valleys, in the same manner abounding in pasturages and water sources. The lake [Utah Lake] reaches up to one of these, and after it a large, very nitrous, section of the valley follows. The lake must be six leagues wide and fifteen long;[21] it extends toward the northwest and, as we were informed, comes in contact through a narrow passage with another much larger one. This one of the Timpanogotzis abounds in several species of good fish, geese, beavers, and other amphibious creatures which we did not have the opportunity to see.[22]

Utah Valley so enamored the mapmaker of the expedition, Captain Miera y Pacheo, that he later wrote to the King of Spain, “This is the most pleasing, beautiful, and fertile site in all New Spain. It alone is capable of maintaining a settlement with as many people as Mexico City and of affording its inhabitants many conveniences, for it has everything necessary for the support of human life.”[23]

The party did not travel north to the Great Salt Lake but were told it “covers many leagues . . . , and its waters are harmful and extremely salty, for the Timpanois assured us that anyone who wet some part of the body with them immediately felt a lot of itching in the part moistened.”[24]

Upon reaching Utah Valley, the expedition continued south, roughly followed the path of modern Interstate 15 into Juab Valley, passed Burraston Ponds, crossed the Sevier River, and eventually made their way through the Scipio Pass. Along the way Escalante regularly noted the many springs they encountered and the good pasturage they found.[25] After crossing through the pass, good water and forage became scarce as they encountered the salt plains and marshes of Utah’s Black Rock Desert. The desperation of the situation is evident in a portion of Escalante’s October 1 entry:

We thought we saw marshland or lake water nearby, hurried our pace, and discovered that what we had judged to be water was salt in some places, saltpeter in others, and in others dried alkaline sediment. We kept on going west by south over a plain and salt flats, and after traveling more than six leagues, we halted without having found water fit to drink or pasturage for the horses, since these already could go no farther. There was some pasturage where we stopped, but bad and scarce. All over the plain behind there had been none, either good or bad.[26]

Leaving the Black Rock Desert they crossed over into the Escalante Desert, where they found occasional water and forage in places such as along the Beaver River but also endured a morale-crushing snowstorm.[27] The length of the journey combined with the recent poor weather, forage, and water sources so discouraged the expedition that when they camped near the site of modern-day Milford on October 8 they began to reconsider their plans for finding a trail to Monterey, California. Three days later there was so much contention over the question that they decided to cast lots to determine whether they should continue to search for a trail to Monterey or return to New Mexico. The lot fell to return.[28]

Rather than backtracking to return they continued south, again roughly following the route of modern Interstate 15 and passing near the future sites of Cedar City, Kanarraville, Toquerville, and Hurricane. Along the way they again found forested land, good pasturage, and land suitable for dry farming. Camping near Pintura, Utah, Escalante observed that the valley

greatly abounds in pasturelands, has large meadows and middling marshes, and very fine land sufficient for a good settlement for dry farming because, although it has no water for irrigating more than some land by the rivulets of San José and El Pilar,[29] the great moisture of the terrain can supply this lack without irrigation being missed; for the moisture throughout the rest of the valley is so great that not only the meadows and lowlands but even the elevations now had pastures as green and as fresh as the most fertile of river meadows during the months of June and July. Very close to its circumference there is a great source of timber and firewood of ponderosa pine and piñon and good sites for raising large and small livestock.”[30]

As they traveled south they found a more temperate climate and noted that “the river poplars were so green and leafy, the flowers and blooms which the land produces so flamboyant and without damage whatsoever, that they indicated there had been no freezing or frosting around here. We also saw growths of mesquite, which does not flourish in very cold lands.”[31] Escalante wrote of the American Indians in the region, some who “dress very poorly, eat wild plant seeds, jackrabbits, piñon nuts in season, and yucca dates” and others “who apply themselves to cultivating maize and squash.”[32]

Eventually the expedition reached the Virgin River and exited Utah near Hurricane Wash, having made for modern readers a record that tells much about the pre-settlement ecology of the Wasatch Range and southern Utah.[33]

Peter Skene Ogden Expedition

Nearly half a century later, Peter Skene Ogden led a large Hudson’s Bay Company–sponsored beaver-trapping expedition through the “Snake Country”[34] that made a short foray into parts of northern Utah. Ogden and his chief clerk, William Kittson, both kept journals of the venture that provide some insights into the pre-settlement environment of northern Utah regions that the Dominguez-Escalante expedition did not explore.[35]

The company entered Utah sometime between May 4 and 7 of 1825. They appear to have followed the Cub River south, passing near the current town of Franklin, Idaho, and then headed southwest to camp on Bear River on the Utah side of the border.[36] They continued generally south through Cache Valley, Ogden Valley, and Weber Valley, passing near or through the modern locations of Richmond, Smithfield, Logan, Paradise, Eden, Huntsville, and Mountain Green, Utah. As they journeyed, they trapped beaver along the waterways they encountered, including the Bear, Cub, Little Bear, Logan, Blacksmith Fork, Ogden, and Weber Rivers and their tributaries.

At the time of the expedition there was fierce competition and confusion between the British Hudson’s Bay Company and the American Fur Company over trapping and territorial rights. Trappers from both companies apparently tried to discourage their competitors by thoroughly harvesting all the beaver in the contended regions. Thus, the trapping success of the Ogden expedition varied greatly in Utah, depending on whether they beat the American Fur Company to the trapping ground.[37] On May 23, while camped on the Weber River near present-day Mountain Green, Ogden’s expedition came face-to-face with the American Fur Company trappers. The meeting threatened to turn violent when the American fur trappers claimed exclusive rights to trap the area and convinced many of Ogden’s party to desert and join their company for better pay and provisions.[38] With his expedition thus reduced to just twenty trappers and with rumors of American Fur Company trappers’ plans to raid and plunder his camp, Ogden felt he had no choice but to leave Utah and go back the way he came, crossing back into Idaho on May 29, 1825.[39]

Although the Ogden expedition’s journey into Utah was relatively short, the information their journals give us about the pre-settlement environment of the area is rich. As they initially crossed the border from Idaho into Utah to make camp on the Bear River, Ogden described traversing “a fine Plain Covered with Buffaloes & thousands of Small Gulls the latter was a Strange Sight to us I presume some large body of Water near at hand at present unknown to us all.”[40] Kittson records that they harvested several bulls and calves from the herds they encountered.[41] The expedition lived off the land, subsisting on whatever game they could find. As beaver was the major item on the menu, buffalo would have been a welcome addition to the expedition’s diet.

At Blacksmith Fork several days later on May 11, Ogden recorded, “Buffalo scarce but grizzily Bears in abundance one of the men had a narrow escape three of them were killed.”[42] Kittson noted that on that day, one member of their advanced party reported climbing a high mountain and seeing a large lake about twelve miles away to the southwest into which the Bear River fell. This would be the first viewing of the Great Salt Lake for the expedition.[43] On May 22 two other trappers would report seeing the lake from a distance, but no one from the expedition apparently traveled to the lake.[44]

As the company moved to the southernmost end of Cache Valley to make camp a little past Paradise, Utah, on the Little Bear River, Ogden again described traversing “fine plains Covered with Buffalo.”[45] At the camp Kittson reported, “White Maple and Oak are to be found here. The river or Fork is lined with poplar and aspin. 79 Beaver, meat of Buffaloe and Elk brought into camp.”[46] On May 15 they moved camp about four miles farther south to find more grass for their horses to eat, but the move proved costly, as several of their horses died from eating poisonous weeds in the area, likely Death Camas or Loco Weed. Ogden despaired of losing all.[47]

Crossing over the mountains from Cache Valley, they descended into what is now called Ogden Valley, where Ogden commented on the rocky road and gravel soil they encountered and was surprised to find “the mountain Covered with white Oak & maple trees,” which he described as “a Strange Sight as we have Seen no Wood of any kind except Willows for these two months past.” Apparently Ogden had forgotten or had failed to observe the poplar, oak, maple, and aspen that Kittson described on the Little Bear River just two days earlier.[48] Judging from the abundance of beaver they found in the Ogden Valley, the company surmised that they had discovered a new spot that the American company had not trapped yet and named it “New Hole,” for as Kittson described it, the valley was a hole “surrounded by lofty mountains and hills,” “not being more than 50 miles in circumference.” They named the Ogden River “New River,” and Kittson described it as being “lined with poplar and willows and about 6 yards in breadth.”[49]

The company stayed in the Ogden Valley until they had trapped it out, taking a total of 563 beaver pelts,[50] and then proceeded south over the mountains to Weber Valley, camping there on May 22. The following day their face-to-face confrontation with the American company began, leading to their hasty departure on May 24. During their flight from Utah, Ogden’s and Kittson’s journals were so preoccupied with reporting the details of their conflict with the American company and the treachery of those who deserted them that they did not record further details on the environment.[51]

Warren Angus Ferris Journal

Five years later, in 1830, nineteen-year-old Warren Angus Ferris, although recently trained as a civil engineer, chose to join the American Fur Company and spent the next six years trapping in the Rocky Mountains. His journal was published as a series in the Western Literary Messenger from July 13, 1842, to May 18, 1844.[52] His is a romantic account rather than a detailed factual treatise, but his forays into the Wasatch Range provide another view of the pre-settlement environment.

On July 7, 1830, Ferris had his first glimpse of a portion of the Bear River Valley, describing it as “a beautiful valley, watered by a shining serpentine river, and grazed by tranquil herds of buffalo” of which they killed a “great many . . . which were all in good condition, and feasted, as may be supposed, luxuriously upon the delicate tongues, rich humps, fat roasts, and savoury steaks of this noble and excellent species of game.”[53] Bear Lake he described as

Navelled in the hills, for it is entirely surrounded by lofty mountains, of which those on the western side are crowned with eternal snow. It gathers its waters from hundreds of rivulets that come dancing and flashing down the mountains, and streams that issue not unfrequently from subterranean fountains beneath them. At the head of the lake opposite, and below us, lay a delightful valley of several miles extent, spotted with groves of aspen and cotton wood, and beds of willows of ample extent.

When first seen the lake appeared smooth and polished like a vast field of glass, and took its colour from the sky which was a clear unclouded blue. It was dotted over by hundreds of pelicans white in their plumage as the fresh-fallen snow.[54]

Ferris was likewise charmed by the Cache Valley, lauding it as “one of the most extensive and beautiful vales of the Rocky Mountain range . . . abundantly fertile, producing every where most excellent grass, and has ever for that reason, been a favorite resort for both men and animals, especially in the winter. Indeed, many of the best hunters assert that the weather is much milder here than elsewhere, which is an additional inducement for visiting it during that inclement season.”[55]

The company’s passage to Cache Valley from Bear Lake was a two-day ordeal as they followed Cache Valley Creek through

a narrow defile, nearly impassable to equestrians. On either side, rose the mountains, in some places almost, and at others quite perpendicularly, to the regions of the clouds. The sun could be seen only for a short time and that in the middle of the day. We were often compelled while struggling over the defile, to cross the stream and force our way through almost impenetrable thickets, and at times, to follow a narrow trail along the borders of precipices, where a single mis-step would inevitably have sent horse and rider to the shades of death. We saw a number of grizzly bears prowling around the rocks, and mountain sheep standing on the very verges of projecting cliffs as far above us as they could be discerned by the eye.[56]

In Cache Valley they continued to encounter grizzly bears, “one of which of a large size, we mistook for a buffalo bull, and were only convinced of our error when the huge creature erected himself on his haunches, to survey us as we passed.”[57]

Ferris had occasion in his journeys to visit the Great Salt Lake, which he called the “Big Lake.” He observed that “its waters are so strongly impregnated with salt that many doubt if it would hold more in solution; I do not however think it by any means saturated, though it has certainly a very briny taste, and seems much more buoyant than the ocean. In the vicinity of the Big Lake we saw dwarf oak and maple trees, as well on the neighboring hills as on the border of streams. This was the first time since leaving the Council Bluffs that we have seen timber of that description.”[58]

The winter of 1834–35 Ferris spent camped on Ashley Creek near modern-day Vernal. He described his winter subsistence there as pleasant:

We pitched quarters in a large grove of aspen trees, at the brink of an excellent spring that supplied us with the purest water, and resolved to pass the winter here. Our hunters made daily excursions in the mountains, by which we were half surrounded, and always returned with the flesh of several black tail deer; an animal almost as numerous as the pines and cedars among which they were found. They frequently killed seven or eight individually, in the course of a day; and consequently our encampment, or at least the trees within it, were soon decorated with several thousand pounds of venison. We passed the time by visiting, feasting, and chatting with each other, or by hunting occasionally, for exercise and amusement. Our camp presented eight leathern lodges, and two constructed of poles covered with cane grass, which grows in dense patches to the height of eight or ten feet, along the river. They were all completely sheltered from the wind by the surrounding trees. Within, the bottoms were covered with reeds, upon which our blankets and robes were spread, leaving a small place in the centre for the fire. . . . At night a good fire of dry aspen wood, which burns clear without smoke, affording a brilliant light, obviates the necessity of using candles.[59]

Though romanticized, Ferris’s record proves to be both entertaining and enlightening in regards to the pre-settlement Wasatch Range environment.

Osborne Russell’s Journal of a Trapper

As an adventurous twenty-year-old young man, Osborne Russell joined Nathaniel J. Wyeth’s expedition to the Rocky Mountains at Independence, Missouri. The expedition was under contract to deliver goods to the Rocky Mountain Fur Company at the 1834 trappers’ rendezvous on Ham’s Fork of the Green River. Unfortunately, by the time Wyeth’s party arrived at the rendezvous, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company was in the throes of fierce competition with the American Fur Company and defaulted on their contract. To recover from the loss, Wyeth built Fort Hall in the Snake River Valley about thirty miles north of present-day Pocatello, Idaho, and used the unsold goods he had transported to set up a trading post. Russell continued working for Wyeth’s Columbia River Fishing and Trading Company for a time, became one of Jim Bridger’s trappers in 1835, and eventually lived as a free trapper, working out of Fort Hall for many years.

During his tenure as a trapper in the Rocky Mountains, Russell kept a somewhat regular journal of his experiences. Though his volume, like Ferris’s work, reads more like a romantic narrative of his adventures than a careful chronicling of facts and events, his effort still provides some insight into pre-settlement Wasatch Range environment.

As he traveled along the Bear River on July 6, 1834, Russell described the valley as “a beautiful country. The river which is about twenty yards wide runs through large fertile bottoms bordered by rolling ridges which gradually ascended on each side of the river to the high ranges of dark and lofty mountains upon whose tops the snow remains nearly the year round.”[60]

In November of 1840 as he again traveled along the Bear River towards Cache Valley, Russell observed “thousands of antelope traveling towards their winter quarters.” He found twenty lodges of Snake Indians in Cache Valley and after a quick trip to Fort Hall for trading supplies returned to join them for the winter.[61] By December 15 the Cache Valley camp determined to relocate and spend the remainder of the winter by the Great Salt Lake. They first camped on the shore of the Great Salt Lake where the “Weaver’s,” or Weber, River enters in.[62] Of the location he wrote, “At this place the Valley is about 10 Mls wide intersected with numerous Springs of salt and fresh hot and cold water which rise at the foot of the Mountain and run thro. the Valley into the river and Lake—Weavers river is well timbered along its banks principally with Cottonwood and box elder—there are also large groves of sugar maple pine and some oak growing in the ravines about the Mountain—We also found large numbers of Elk which had left the Mountain to winter among the thickets of wood and brush along the river.”[63]

The region’s ability to provide for its inhabitants may be seen in Osborne’s colorful description of a Christmas Day feast they enjoyed:

The first dish that came on was a large tin pan 18 inches in diameter rounding full of Stewed Elk meat The next dish was similar to the first heaped up with boiled Deer meat (or as the whites would call it Venison a term not used in the Mountains) The 3d and 4th dishes were equal in size to the first containing a boiled flour pudding prepared with dried fruit accompanied by 4 quarts of sauce made of the juice of sour berries and sugar Then came the cakes followed by about six gallons of strong Coffee already sweetened with tin cups and pans to drink out of large chips or pieces of Bark Supplying the places of plates. on being ready the butcher knives were drawn and the eating commenced at the word given by the landlady.[64]

On January 3 the camp moved away from the shores of the Great Salt Lake to the foot of the Wasatch Range by the confluence of the Weber and Ogden Rivers. Russell recorded that the two rivers both come through “the mountain in a deep narrow cut The mountain is very high steep and rugged which rises abruptly from the plain about the foot of it are small rolling hills abounding with springs of fresh water. The land bordering on the river and along the Stream is a rich black alluvial deposite but the high land is gravelly and covered with wild sage with here and there a grove of scubby oaks and red cedars.”[65] They spent the remainder of January at this location where Russell recalls: “I passed the time very agreeably hunting Elk among the timber in fair weather and amusing myself with books in foul.”[66]

On February 24, 1841, Russell determined to travel to “Eutaw Village at the SE extremity of the Lake to trade furs.” As he journeyed down the Salt Lake Valley he described it as “a beautiful and fertile Valley intersected by large numbers of fine springs which flow from the mountain to the Lake and could with little labour and expense [be] made to irrigate the whole Valley.”[67]

He found the Eutaw Village on February 26 and became the guest of Chief Want a Sheep until the end of March. He greatly enjoyed the experience, finding the people to be living a content and well-sustained life: “I passed the time as pleasantly at this place as ever I did among Indians in the daytime I rode about the Valley hunting water fowl who rend the air at this season of the year with their cries.”[68]

Leaving the Eutaw Village on March 27, 1841, Russell headed north to return to Fort Hall with furs he had acquired. Passing through Salt Lake Valley he noted at one point that “fire had run over this part of the country the previous autumn and consumed the dry grass The new had sprung up to the height of 6 inches intermingled with various kinds of flowers in full Bloom. The shore of the Lake was swarming with waterfowls of every species that inhabits inland lakes.”[69]

Russell made one more foray into the northern end of the Salt Lake Valley later that year by following the Bear River to “near where it empties into the Salt Lake.” He observed that “Along the bank of this stream for about 10 Mls from the Lake extends a barren clay flat destitute of Vegetation excepting a few willows along the banks of the river and scattering spots of Salt grass and Sage in one place there was about 4 or 5 acres covered about 4 inches deep with the most beautiful salt I ever saw. two crusts had formed one at the bottom and the other on the top which had protected it from being the least soiled between those crusts the salt was Completely dry loose and composed of very small grains of a snowy whiteness.”[70]

After careful study of the Bible later in his trapping career, Russell became convinced that the trapper’s life was not in harmony with biblical teachings. In 1842 he gave up the mountain man life to settle in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, where he was a major player in founding the provisional government of Oregon and serving as its first supreme judge. After a series of subsequent political and business setbacks, Russell moved to California in 1848, where he operated as a merchant and served the gold-rush population. He died in Placerville, California, in 1892[71] but fortunately left us his record and recollections.

John C. Frémont Report

Designated as America’s “Pathfinder,” John C. Frémont was a well-known government-commissioned explorer whose reports became popular reading for adventurers headed west and, some speculate, may have influenced Brigham Young to consider the Salt Lake Valley as a future home for the Saints.[72] In 1843 he led an expedition that mostly followed the Oregon Trail from Missouri to Fort Vancouver. At Soda Springs, Idaho, he left the Oregon Trail for a time and headed south to see the Great Salt Lake.

On August 21 Frémont recorded that the expedition entered “into the fertile and picturesque valley of Bear river, the principal tributary to the Great Salt lake. The stream is here 200 feet wide, fringed with willows and occasional groups of hawthorns.”[73] The party followed the Bear River into Utah, through Cache Valley, and over to the Great Salt Lake, which they explored and mapped in a leaky rubber boat. Along the way they encountered encampments of American Indians with whom they frequently traded goods for locally gathered meat, roots, and berries. As they traveled, Frémont occasionally commented on the “pretty streams” they encountered and the elk, antelope, and mountain sheep they saw as well as the ducks, geese, cranes, and grouse they observed. He noted the good soil and grass when they traversed it and the flowering plants, groves of cedars, maples, cottonwoods, aspen, willow, elder and “cane thickets” they passed.[74]

As the explorers neared the Great Salt Lake, Frémont began to note the changes in vegetation and soil, mentioning salty and marshy areas interspersed with areas of good water and soil. Their dwindling supplies forced Frémont to send a party to Fort Hall for provisions, while the remainder continued on their way to explore the lake, sustaining themselves upon the local roots and waterfowl. On the eve of reaching the lake, September 8, 1843, Frémont recorded: “The evening was mild and clear; we made a pleasant bed of the young willows; and geese and ducks enough had been killed for an abundant supper at night, and for breakfast the next morning. The stillness of the night was enlivened by millions of water fowl.”[75]

They paddled their rubber boat the next day to what is now known as Fremont Island and spent the night thereon. Frémont described the many species of salt-loving plants he observed, giving one he thought a new species his own name—Fremontia vermicularis. Today the plant is known as Sarcobatus vermicularis, or common greasewood. They returned to the mainland the next day, September 10, spent the following day distilling salt from the lake water, and then headed back the way they came to resume their journey along the Oregon Trail.[76]

On the return trip Frémont again regularly commented on the flora, fauna, and soil they encountered. At one particularly well-timbered creek he made a list of the species he observed: “Among them were birch (betula,) the narrow-leaved poplar (populus angustifolia,) several kinds of willow (solix) [salix], hawthorn (crataegus,) alder (alnus viridis,) and cerasus, with an oak allied to quercus alba but very distinct from that of any other species in the United States.” Frémont then added, “We had to-night a supper of sea gulls, which Carson killed near the lake. Although cool, the thermometer standing at 47 [degrees], musquitoes were sufficiently numerous to be troublesome this evening.”[77]

Frémont described the rapid demise of the buffalo herds that once thrived in the area and lamented the scarcity of other game once common not only for the loss but also for the subsistence difficulties it caused themselves and the American Indians. The party dispatched to Fort Hall for provisions was slow in returning, and as hunger grew among the remaining party members, morale began to falter, but Frémont found a remedy: “The people this evening looked so forlorn, that I gave them permission to kill a fat young horse which I had purchased with goods from the Snake Indians, and they were very soon restored to gayety and good humor. Mr. Preuss and myself could not yet overcome some remains of civilized prejudices, and preferred to starve a little longer; feeling as-much saddened as if a crime had been committed.”[78]

Upon exiting the Bear River Valley Frémont gave his summary of the potential of this portion of the Wasatch Range.

The bottoms of this river, (Bear,) and of some of the creeks which I saw, form a natural resting and recruiting station for travelers, now, and in all time to come. The bottoms are extensive; water excellent; timber sufficient; the soil good, and well adapted to the grains and grasses suited to such an elevated region. A military post, and a civilized settlement, would be of great value here; and cattle and horses would do well where grass and salt so much abound. The lake will furnish exhaustless supplies of salt. All the mountain sides here are covered with a valuable nutritious grass, called bunch grass, from the form in which it grows, which has a second growth in the fall. The beasts of the Indians were fat upon it; our own found it a good subsistence; and its quantity will sustain any amount of cattle, and make this truly a bucolic region.[79]

In 1844 Frémont again led an expedition into Utah, this time following the Old Spanish Trail entering in the southeast corner of the state and then making their way up to Utah Valley, where they followed the Spanish Fork River up and over to the Uintah Basin before returning to the Midwest.

As they camped by the Santa Clara River, Frémont recorded: “The stream is prettily wooded with sweet cotton wood trees—some of them of large size; and on the hills, where the nut pine is often seen, a good and wholesome grass occurs frequently.”[80] The next day they entered Mountain Meadows, which they called “Las Vegas de Santa Clara.” Frémont reported,

We considered ourselves as crossing the rim of the basin; and, entering it at this point, we found here an extensive mountain meadow, rich in bunch grass, and fresh with numerous springs of clear water, all refreshing and delightful to look upon. It was, in fact, that las Vegas de Santa Clara which had been so long presented to us as the terminating point of the desert, and where the annual caravan from California to New Mexico halted and recruited for some weeks. It was a very suitable place to recover from the fatigue and exhaustion of a month’s suffering in the hot and sterile desert. The meadow was about a mile wide, and some ten miles long, bordered by grassy hills and mountains.[81]

As they neared Sevier Lake on May 17, 1844, he was impressed by the agricultural potential of the region: “We had now entered a region of great pastoral promise, abounding with fine streams, the rich bunch grass, soil that would produce wheat, and indigenous flax growing as if it had been sown.”[82] However, he further noted that “consistent with the general character of its bordering mountains, this fertility of soil and vegetation does not extend far into the Great Basin.”[83]

On May 25, 1844, they were encamped on the shores of Utah Lake near several American Indian camps from where they obtained fresh fish. Frémont mentioned two plants in the region of particular importance: “Here the principal plants in bloom were two, which were remarkable as affording to the Snake Indians—the one an abundant supply of food, and the other the most useful among the applications which they use for wounds. These were the kooyah plant, growing in fields of extraordinary luxuriance, and convollaria stellata, which, from the experience of Mr. Walker, is the best remedial plant known among those Indians.”[84] The region between the eastern shore of Utah Lake and the Wasatch Range Frémont described as “a plain, where the soil is generally good, and in greater part fertile; watered by a delta of prettily timbered streams. This would be an excellent locality for stock farms; it is generally covered with good bunch grass, and would abundantly produce the ordinary grains.”[85] He later generalized, “In this eastern part of the Basin, containing Sevier, Utah, and the Great Salt lakes, and the rivers and creeks falling into them, we know there is good soil and good grass, adapted to civilized settlements.”[86]

Frémont made additional trips through Utah after the Latter-day Saints arrived in the Salt Lake Valley and went on to have a remarkable military and political career.

William Clayton’s Journal

In addition to the records left by early trappers and explorers, the writings of the first Mormon pioneers to enter the Wasatch Range provide insights into the pre-settlement environment of the region. The journal kept by William Clayton is perhaps the most informative. Clayton was a trusted record keeper, as evidenced by his appointments as secretary to Joseph Smith in 1842 and later that year as temple recorder and recorder of the revelations. He was among the first of the Saints to enter the Wasatch Range. His journal frequently comments on the environments the Saints encountered on their trek west.

The Mormon pioneers received an advance report on what they would find in the Wasatch Range in a June 28, 1847, discussion with Jim Bridger. Clayton recorded that Bridger said, “In the Bear River valley there is oak timber, sugar trees, cottonwood, pine and maple. There is not an abundance of sugar maple but plenty of as splendid pine as he ever saw. There is no timber on the Utah Lake only on the streams which empty into it. In the outlet of the Utah Lake which runs into the salt lake there is an abundance of blue grass and red and white clover.”[87]

On Monday, July 12, the Saints crossed the Bear River, which Clayton described as “a very rapid stream about six rods wide and two feet deep, bottom full of large cobble stones, water clear, banks lined with willows and a little timber, good grass, many strawberry vines and the soil looks pretty good.” Continuing west, he recorded, “About a half mile beyond the ford, proceeded over another ridge and again descended into and traveled up a beautiful narrow bottom covered with grass and fertile but no timber.” They made camp that night by “a very small creek and a good spring” where there was “an abundance of good grass,” and Clayton noted that “the country appears to grow still richer as we proceed west, but very mountainous. There are many antelope on these mountains and the country is lovely but destitute of timber.”[88]

On July 14 they again camped by “a beautiful spring of good clear water” where the “feed” was good. On July 16 as they began their passage through the mountains toward the Weber River Canyon, the way narrowed and they encountered many more “springs of clear water all along the base of the mountains.” At one point Clayton observed: “for several miles there are many patches or groves of the wild currant, hop vines, alder and black birch. Willows are abundant and high. The currants are yet green and taste most like a gooseberry, thick rind and rather bitter. The hops are in blossom and seem likely to yield a good crop. The elder-berries, which are not very plentiful, are in bloom.”[89]

When they made camp that night, Clayton summarized, “We are yet enclosed by high mountains on each side, and this is the first good camping place we have seen since noon, not for lack of grass or water, but on account of the narrow gap between the mountains. Grass is pretty plentiful most of the distance and seems to grow higher the farther we go west. At this place the grass is about six feet high, and on the creek eight or ten feet high. There is one kind of grass which bears a head almost like wheat and grows pretty high, some of it six feet.”[90]

They reached the Weber River on Saturday, July 17, where Clayton wrote: “This stream is about four rods wide, very clear water and apparently about three feet deep on an average. Its banks lined with cottonwood and birch and also dense patches of brush wood, willows, rose bushes, briers, etc.” There they found the “mosquitoes plentiful,” but the nuisance was perhaps ameliorated by the good fishing. Clayton records that “several of the Brethren have caught some fine trout in this stream which appears to have many in it.”[91]

The pioneers’ westward push on July 20 was especially difficult as they passed “through an uneven gap between high mountains” by forging through swampy areas; they were forced to cross the creek they were following eleven times while pushing through dense “willow bushes over twenty feet high, also rose and gooseberry bushes and shaking poplar and birch timber” that threatened to tear wagon covers. Good grass was scarce, and the springs they encountered had poor water. Though they occasionally saw some pine on the mountains, the prospect for building timber seemed bleak. Clayton labeled it “a truly wild looking place.”[92]

Conditions improved a little the following day as they crested the mountains, locked their wagon wheels, and began their descent. At points they found good springs of cold water, an abundance of “good and rich” service berries to enjoy, “sugar maple,” and “considerable other timber along the creek.” The roughness of the road and a lack of quality grass for the livestock continued to be a concern that day.[93]

On July 22, while some worked to improve the rough road, Clayton hiked to the top of a hill where he “was much cheered by a handsome view of the Great Salt Lake lying, as I should judge, from twenty-five to thirty miles to the west of us.” He described the view and his feelings in elegant language:

There is an extensive, beautiful, level looking valley from here to the lake which I should judge from the numerous deep green patches must be fertile and rich. . . . The lake does not show at this distance a very extensive surface, but its dark blue shade resembling the calm sea looks very handsome. The intervening valley appears to be well supplied with streams, creeks and lakes, some of the latter are evidently salt. There is but little timber in sight anywhere, and that is mostly on the banks of creeks and streams of water which is about the only objection which could be raised in my estimation to this being one of the most beautiful valleys and pleasant places for a home for the Saints which could be found. Timber is evidently lacking but we have not expected to find a timbered country. . . . There is doubtless timber in all passes and ravines where streams descend from the mountains. . . . For my own part I am happily disappointed in the appearance of the valley of the Salt Lake, but if the land be as rich as it has the appearance of being, I have no fears but the Saints can live here and do well while we will do right.[94]

Leaving his hilltop vista, Clayton traveled down the creek, along the way noting

bull rushes of the largest kind I ever saw, some of them being fifteen feet high and an inch and a half in diameter at the bottom. The grass on this creek grows from six to twelve feet high and appears very rank. There are some ducks around and sand hill cranes. Many signs of deer, antelope, and bears. . . . The ground seems literally alive with the very large black crickets crawling around up grass and bushes. They look loathsome but are said to be excellent for fattening hogs which would feed on them voraciously. The bears evidently live mostly on them at this season of the year.[95]

After four hours of labor the road was ready, and Clayton joined the rest of the company to continue the descent:

We found the last descent even but very rapid all the way. At half past five, we formed our encampment on a creek supposed to be Brown’s Creek having traveled seven and a quarter miles today. We are now five and a quarter miles from the mouth of this canyon making the whole distance of rough mountain road from the Weber River to the mouth of the canyon on this side a little less than thirty-five miles and decidedly the worst piece of road on the whole journey. At this place, the land is black and looks rich, sandy enough to make it good to work. The grass grows high and thick on the ground and is well mixed with nice green rushes. Feed here for our teams is very plentiful and good and the water is also good. There are many rattlesnakes of a large size in this valley and it is supposed they have dens in the mountains. The land looks dry and lacks rain, but the numerous creeks and springs must necessarily tend to moisten it much. The grass looks rich and good.[96]

The next day, July 23, the company pushed on into the valley and began to settle their new home. Clayton was full of hope: “The grass here appears even richer and thicker on the ground than where we left this morning. The soil looks indeed rich, black and a little sandy. The grass is about four feet high and very thick on the ground and well mixed with rushes. If we stay here three weeks and our teams have any rest they will be in good order to return.”[97]

Settlement Begins

From these early accounts we can conclude that while much of the Great Basin was indeed a harsh and dry desert, the Wasatch Range was a land of great promise.[98] The pre-settlement composition of the plant communities consisted of grass-dominated meadows in the valley bottoms, bunch grass and sage on the foothill slopes, piñon-juniper on the upper valley slopes merging into mountain brush, and aspen and conifer forests in the higher elevations. Moreover, there were adequate water resources to be found in the streams, rivers, and lakes of the region. Wildlife had long sustained the American Indians in the area and could be counted on to supplement the settlers’ subsistence. In terms of vegetation, water, and wildlife resources, the land was indeed well outfitted for settlement.

Clayton recorded the following on arriving in the Salt Lake Valley:

As soon as the camp was formed a meeting was called and the brethren addressed by Elder Richards, mostly on the necessity and propriety of working faithfully and diligently to get potatoes, turnips, etc., in the ground. Elder Pratt reported their mission yesterday and after some remarks the meeting was dismissed. At the opening, the brethren united in prayer and asked the Lord to send rain on the land, etc. The brethren immediately rigged three plows and went to plowing a little northeast of the camp; another party went with spades, etc., to make a dam on one of the creeks so as to throw the water at pleasure on the field, designing to irrigate the land in case rain should not come sufficiently. This land is beautifully situated for irrigation, many nice streams descending from the mountains which can be turned in every direction so as to water any portion of the lands at pleasure. During the afternoon, heavy clouds began to collect in the southwest and at five o’clock we had a light shower with thunder. We had rains for about two hours.[99]

Within eight days the settlement had made remarkable progress, and the potential of the pioneers’ new home began to be realized as indicated in a report given by Colonel Markham:

There are three lots of land already broke. One lot of thirty-five acres of which two-thirds is already planted with buckwheat, corn, oats, etc. One lot of eight acres which is all planted with corn, potatoes, beans, etc. And a garden of ten acres, four acres of which is sown with garden seed. . . . there are about three acres of corn already up about two inches above the ground and some beans and potatoes up too. This is the result of eight days’ labor, besides making a road to the timber, hauling and sawing timber for a boat, making and repairing plows, etc.[100]

Learning how to irrigate was a critical challenge for the Latter-day Saints. Alfred R. Golze explained, “The Mormons were forced to make irrigation a success or perish.”[101] During the afternoon of July 23, they began “irrigation as it is practiced today” by building a dam across City Creek and diverting enough water to soak “five acres of exceedingly dry land.” By the spring of 1848 they already had five thousand acres of irrigated land under cultivation.[102]

Within thirteen years of their arrival in the Salt Lake Valley the Latter-day Saints had established most of the major settlements along the Wasatch Range. Years later, Great Basin ecologist Walter Cottam described how settlement sites were chosen. He observed that each settlement was “located at the base of a mountain front, at an altitude conducive to the growth of a variety of farm crops, on a valley plain of rich soil where mountain streams supply water sufficient for irrigation and culinary purposes.” Cottam also explained that “sites thus selected for settlement were provided with nearby pasture land that furnished year-round feed for farm livestock and with an expanse of desert range suitable for winter grazing.” He concludes that the “mountains nearby provided a perpetual flow of life-giving water, timber for building, wood for fuel, and forage for the summer grazing of range stock.”[103]

Conclusion

In 1877 renowned naturalist John Muir visited the Salt Lake Valley and reported his impressions of the city of the Saints. His account tells us much about the progress the Mormon pioneers had made in settling the land. Muir observed:

At first sight there is nothing very marked in the external appearance of the town [Salt Lake City] excepting its leafiness. Most of the houses are veiled with trees, as if set down in the midst of one grand orchard. . . . Perhaps nineteen twentieths of the houses are built of bluish-gray adobe bricks, and are only one or two stories high, forming fine cottage homes which promise simple comfort within. They are set well back from the street, leaving room for a flower garden, while almost every one has a thrifty orchard at the sides and around the back. The gardens are laid out with great simplicity, indicating a love for flowers by a people comparatively poor. . . . In almost every one you find daises, and mint, and lilac bushes, and rows of plain English tulips. Lilacs and tulips are the most characteristic flowers, and nowhere have I seen them in greater perfection.”[104]

Muir reported that he saw little evidence of great wealth among the Saints, “though many a Saint is seeking it as keenly as any Yankee Gentile. But on the other hand, searching throughout all the city, you will not find any trace of squalor or extreme poverty.”[105] Although he appreciated the gardens, homes, and communities the Saints had established, like many of the day, Muir was distressed by the Mormon practice of polygamy. He felt animosity towards the men because of the practice, feeling it rendered them “incapable of loving anything.” He felt pity for the wives of polygamists, who surprised him. He remarked, “Strange as it must seem to Gentiles, the many wives of one man, instead of being repelled from one another by jealousy, appear to be drawn all the closer together.”[106] He further observed, “Liliaceous women . . . are rare among the Mormons. They have seen too much hard, repressive toil to admit to the development of lily beauty either in form or color. In general they are thickset, with large feet and hands, and with sun-browned faces, often curiously freckled like the petals of Fritillaria atropurpurea. They are fruit rather than flower—good brown bread.”[107]

Although he was concerned about the adults, Muir admired the children: “The little Latter-Day boys and girls are as happy and natural as possible, running wild, with plenty of good hearty parental indulgence, playing, fighting, gathering flowers in delightful innocence. . . . these Mormon children, ‘Utah’s best crop,’ seem remarkably bright and promising.”[108] Over the years Muir’s assessment of promise has been realized. Time has demonstrated that the pioneer Latter-day Saints had indeed found a place for them and their posterity to prosper—the Wasatch Range—a place which they felt and feel today that “God [had] for [them] prepared.”

Notes

[1] The Wasatch Range is the western portion of the Rocky Mountains that extends about 160 miles from the Utah–Idaho border into central Utah. The range forms the eastern edge of the Great Basin, North America’s largest endorheic or closed watershed that includes most of Nevada and western Utah and extends into portions of eastern California and southern Idaho, Wyoming and Oregon.

[2] For a good discussion of the Saints’ understanding of the location to which they were headed, see Richard E. Bennett, We’ll Find the Place: The Mormon Exodus, 1846–1848 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1997), 8–10. See also Jared Farmer, On Zion’s Mount: Mormons, Indians, and the American Landscape (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008), 39–42.

[3] In an 1831 revelation, God assured Latter-day Saints that he would give them “a land flowing with milk and honey” (D&C 38:18). But at the time, this promise was typically understood to apply to the Zion they hoped to build in Jackson County, Missouri.

[4] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 13:173. Though Brigham Young reported that the meeting with Bridger took place on the Big Sandy River, other accounts place it closer to the Little Sandy River crossing. For a review of the issue, see LaMar C. Berrett and A. Gary Anderson, eds., Sacred Places, vol. 6: Wyoming and Utah (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2007), 126–28. While portions of the Great Basin, such as the Bonneville Salt Flats, are very sterile, Jim Bridger actually spoke highly of the Salt Lake Valley and encouraged Brigham Young to settle there. For a review of the debate about where to settle and about the information the Saints were receiving as they neared the Wasatch Range, see Bennett, We’ll Find the Place, 191–96; and Farmer, On Zion’s Mount, 41–42.

[5] For examples, see Heber J. Grant, in Conference Report, April 1921, 212; Adam S. Bennion, in Conference Report, October 1955, 119; and B. H. Roberts, Defense of the Faith and the Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1907), 1:96.

[6] For examples, see LeGrand Richards, in Conference Report, October 1948, 44; James E. Faust, “Perseverance,” Ensign, May 2005, 51–53; and Gordon B. Hinckley, “Look to the Future,” Ensign, November 1997, 67.

[7] William Clayton, “Come, Come, Ye Saints,” Hymns (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985), no. 30.

[8] Padre Francisco Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, The Dominguez-Escalante Journal, ed. Ted J. Warner, trans. Fray Angelico Chavez (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1995), xiv. Though his surname is Vélez, and he should properly be referred to as Padre Vélez as Warner points out, we will follow the common convention of referring to him as Escalante, a name preserved in Utah by such places as the Escalante Desert, the Escalante River, the Escalante Forest, the Escalante State Park and the town of Escalante. While Escalante was the designated recorder for the expedition, it is thought that Dominguez also contributed to the journal.

[9] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 51–97.

[10] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 51–52.

[11] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 54nn199–200.

[12] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 54–60, 56nn206–7.

[13] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 58n214.

[14] A Ute boy who joined the party along the way.

[15] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 60n221.

[16] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 60–64, 61nn223–24, 62nn227–28, 64n236, 64n239.

[17] In Spanish, Nuestra Sefora de la Merced de Timpanogotzis. Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 64n239.

[18] In Spanish, Vega del Dulcisimo Nombre de Jesús. Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 64n240.

[19] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 64.

[20] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 70n246.

[21] About 15¾ by 39½ miles. They typically overestimated distances in the Utah Valley.

[22] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 70–72, 70nn247–49, 71nn250–51, 72n252.

[23] William Mulder and Russell Mortensen, Among the Mormons (Salt Lake City: Western Epics, 1994), 220.

[24] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 72.

[25] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 73–78, 74nn259–61, 76n268, 78n273.

[26] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 78.

[27] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 80–83, 81n283, 82n285.

[28] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 83–90, 85n293.

[29] Ash Creek.

[30] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 91–96, 92n305, 94n310, 96n317.

[31] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 95.

[32] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 94, 96.

[33] Escalante, Dominguez-Escalante Journal, 97n319.

[34] Ogden’s Snake Country expeditions took him through areas that are now part of Washington, Oregon, California, Nevada, Idaho, and Utah. David E. Miller observes, “It is probably accurate to say that no other man led larger expeditions farther over more unexplored territory.” David E. Miller, ed., “Peter Skene Ogden’s Journal of His Expedition to Utah, 1825,” Utah Historical Quarterly 20, no. 2 (April 1952): 159.

[35] See David E. Miller, ed., “William Kittson’s Journal, Covering Peter Skene Ogden’s 1824–1825 Snake Country Expedition,” Utah Historical Quarterly 22, no 2 (April 1954): 125–42. In this article and in David E. Miller, ed., “Peter Skene Ogden’s Journal,” 159–87, Miller only includes those portions of the journals dealing with travel in Utah. Miller does an excellent work in the notes of tracing the journey using modern landmarks for current readers.

[36] Miller, “Peter Skene Ogden’s Journal,” 171n38.

[37] Miller, “Peter Skene Ogden’s Journal,” 167, 173–75, 177–78, 175n56, 178n66; Miller, “William Kittson’s Journal,” 134–35.

[38] Miller, “Peter Skene Ogden’s Journal,” 181–85; Miller, “William Kittson’s Journal,” 137–41. The Ogden expedition initially was large, boasting fifty-eight men and sixty-five women and children. Most of the men were “freemen,” meaning they worked for the company by choice. The deserters to the American Fur Company appear to have come from their ranks. See Miller, “Peter Skene Ogden’s Journal,” 160–61.

[39] Miller, “Peter Skene Ogden’s Journal,” 181–86; Miller, “William Kittson’s Journal,” 137–41.

[40] Miller, “Peter Skene Ogden’s Journal,” 171–72, 171n38, 172n39. When quoting sources originally written in English, we will use the authors’ original spelling and punctuation when known. Miller speculates the gulls mentioned here were California Gulls common around the Great Salt Lake.

[41] Miller, “William Kittson’s Journal,” 132; Miller, “Peter Skene Ogden’s Journal,” 161.

[42] Miller, “Peter Skene Ogden’s Journal,” 174.

[43] Miller, “William Kittson’s Journal, 134n26. Miller notes that this is the earliest known eyewitness, written account of the discovery of the Great Salt Lake, though Jim Bridger and likely others had seen it before.

[44] Miller, “Peter Skene Ogden’s Journal,” 180n79.

[45] Miller, “Peter Skene Ogden’s Journal,” 175n54.

[46] Miller, “William Kittson’s Journal,” 134–35.

[47] Miller, “Peter Skene Ogden’s Journal,” 176n59.

[48] Miller, “Peter Skene Ogden’s Journal,” 176n61.

[49] Miller, “William Kittson’s Journal,” 135n32; Miller, “Peter Skene Ogden’s Journal,” 178–79.

[50] Miller, “Peter Skene Ogden’s Journal,” 179n69.

[51] Miller, “William Kittson’s Journal,” 136–42; Miller, “Peter Skene Ogden’s Journal,” 178–86.

[52] Warren Angus Ferris, Life in the Rocky Mountains, ed. Herbert S. Auerbach and J. Cecil Alter (Salt Lake City: Rocky Mountain Book Shop, 1940).

[53] Ferris, Life in the Rocky Mountains, 39.

[54] Ferris, Life in the Rocky Mountains, 41.

[55] Ferris, Life in the Rocky Mountains, 42.

[56] Ferris, Life in the Rocky Mountains, 42.

[57] Ferris, Life in the Rocky Mountains, 43.

[58] Ferris, Life in the Rocky Mountains, 60, 61.

[59] Ferris, Life in the Rocky Mountains, 222n1, chap. 56. As the years passed, Ferris’s journal became less detailed about the location and environment in which he trapped.

[60] Osborne Russell, Journal of a Trapper: or, Nine Years in the Rocky Mountains, 1834–1843 (Boise, ID: Syms-York Co., 1921), 9.

[61] Russell, Journal of a Trapper, 113.

[62] Aubrey L. Haines, ed., Osborne Russell’s Journal of a Trapper (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965), 114n174.

[63] Russell, Journal of a Trapper, 114.

[64] Russell, Journal of a Trapper, 115.

[65] Russell, Journal of a Trapper, 117.

[66] Russell, Journal of a Trapper, 118.

[67] Russell, Journal of a Trapper, 121.

[68] Russell, Journal of a Trapper, 122.

[69] Russell, Journal of a Trapper, 122.

[70] Russell, Journal of a Trapper, 123.

[71] Haines, Osborne Russell’s Journal of a Trapper, v–xv.

[72] Farmer, On Zion’s Mount, 39.

[73] J. C. Frémont, Report of the Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the Year 1843, and to Oregon and North California in the Years 1843–44 (Washington DC: Gales and Seaton, 1843), 132.

[74] Frémont, Report of the Exploring Expedition, 132–41, 146.

[75] Frémont, Report of the Exploring Expedition, 149–53.

[76] Frémont, Report of the Exploring Expedition, 153–58.

[77] Frémont, Report of the Exploring Expedition, 158. The Carson referred to here is the legendary Kit Carson, who served as a guide for the expedition.

[78] Frémont, Report of the Exploring Expedition, 143–45, 159.

[79] Frémont, Report of the Exploring Expedition, 160.

[80] Frémont, Report of the Exploring Expedition, 270.

[81] Frémont, Report of the Exploring Expedition, 270.

[82] Frémont, Report of the Exploring Expedition, 271.

[83] Frémont, Report of the Exploring Expedition, 271, 272.

[84] Frémont, Report of the Exploring Expedition, 273; emphasis added. The kooyah plant is Valeriana edulis, commonly known as tobacco root, and convollaria stellate is a misspelling for Convallaria stellate, today renamed Maianthemum stellatum, commonly known as “starry false lily of the valley.”

[85] Frémont, Report of the Exploring Expedition, 274.

[86] Frémont, Report of the Exploring Expedition, 276. From this point, Frémont’s party turned by Spanish Fork Canyon and headed east out of the state. Frémont made another trip through Utah in 1845 that was not part of his congressional report and a final visit to the state in 1853.

[87] William Clayton’s Journal: A Daily Record of the Journey of the Original Company of “Mormon” Pioneers from Nauvoo, Illinois, to the Valley of the Great Salt Lake (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1921), 275.

[88] William Clayton’s Journal, 290, 291.

[89] William Clayton’s Journal, 294, 295.

[90] William Clayton’s Journal, 295, 296.

[91] William Clayton’s Journal, 297, 298.

[92] William Clayton’s Journal, 303, 304.

[93] William Clayton’s Journal, 304–6.

[94] William Clayton’s Journal, 308, 309.

[95] William Clayton’s Journal, 310, 311.

[96] William Clayton’s Journal, 311.

[97] William Clayton’s Journal, 312, 313.

[98] For further discussion on the Wasatch Range environment in comparison to other regions of the Great Basin, see Farmer, On Zion’s Mount, 20–23.

[99] William Clayton’s Journal, 312, 313.

[100] William Clayton’s Journal, 329–30.

[101] Alfred R. Golze, Reclamation in the United States (Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers, 1961), 8.

[102] Golze, Reclamation in the United States, 6.

[103] Walter P. Cottam, “Is Utah Sahara Bound?,” Bulletin of the University of Utah 37, no. 11 (1947): 6.

[104] John Muir, Steep Trails (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1918), 106–7.

[105] Muir, Steep Trails, 109.

[106] Muir, Steep Trails, 110.

[107] Muir, Steep Trails, 136–37. Liliaceous means lily like.

[108] Muir, Steep Trails, 112.