The Pioneer Trail: Routes of the Iron Horse and the Horseless Carriage

Richard O. Cowan

Richard O. Cowan, “The Pioneer Trail: Routes of the Iron Horse and the Horseless Carriage,” in Far Away in the West: Reflections on the Mormon Pioneer Trail, edited by Scott C. Esplin, Richard E. Bennett, Susan Easton Black, and Craig K. Manscill (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 233–48.

Richard O. Cowan was a professor emeritus of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was written.

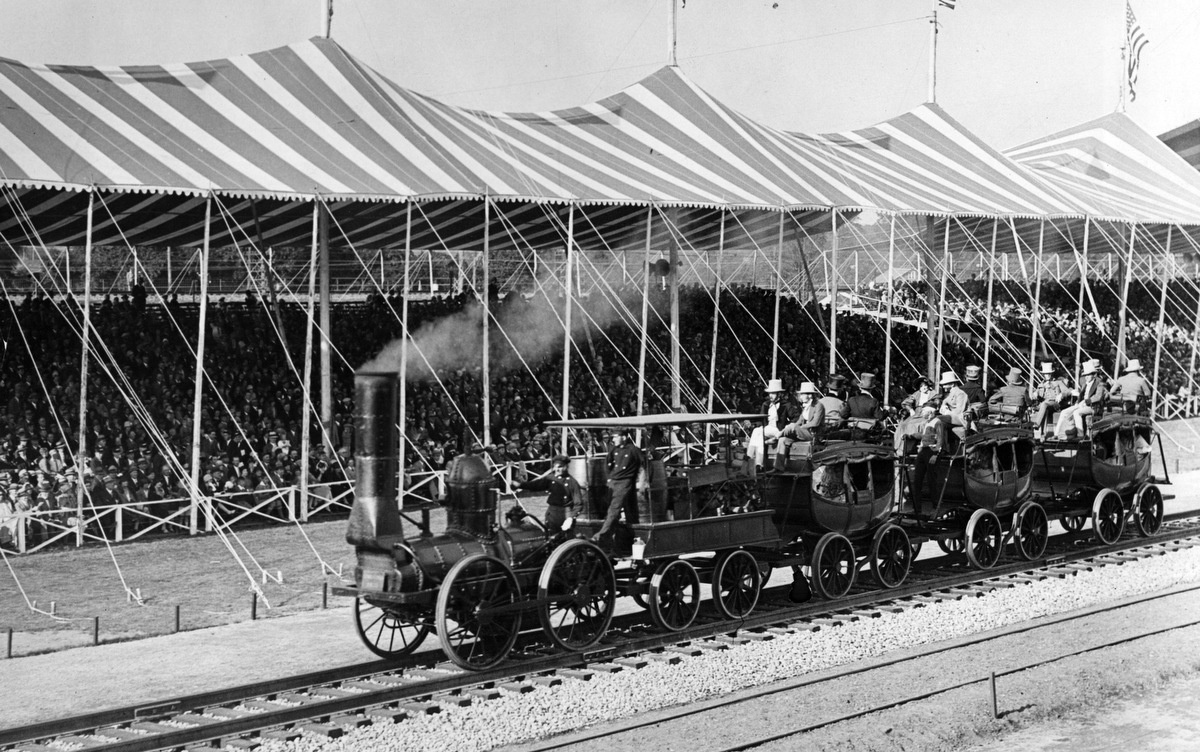

The Iron Horse. Photograph taken in 1827.

The Iron Horse. Photograph taken in 1827.

For the most part, the Mormon pioneers perfected already existing trails. The Mormon Trail would then be followed by thousands of others crossing the plains by wagon. Later, railroads and highways would also follow their route in a general way. How closely did these later travel arteries adhere to the pioneers’ trail? Did the earlier routes actually influence the choices made by those who came afterwards? What considerations did the planners of travel by wagon, train, or automobile have in common? What other considerations were unique to each mode of travel?

The Pioneer Trail

As Latter-day Saints faced the necessity to abandon Nauvoo, Illinois, they felt that they needed a place which could support their settlements but where they could be left alone in relative isolation to grow and develop—probably a place no one else wanted and where they would be free to live their religion.[1] Perhaps a refuge in the tops of the mountains could meet these requirements. The John C. Frémont maps that had just been published gave the Saints a good idea of the westward route through the Platte and Sweetwater Valleys to South Pass. Elder Parley P. Pratt wrote a letter in November 1845 in which he said:

Our Apostles, assembled in meeting, have debated the best method of getting all our people into the far west with the least possible hardship. We have read Hastings’ Account of California and Fremont’s Journal of Explorations in the West, and we have concluded that the Great Basin in the top of the Rocky Mountains, where lies the Great Salt Lake, is the proper place for us. Fremont visited this place, and he says that the soil is fertile and traversed by many mountain streams. This will make it possible to irrigate during the times of drought. And so, it looks as if we will head for the mountains where Joseph so longingly turned his eyes during his life.[2]

Leaving Nauvoo early in 1846, the Latter-day Saints hoped to reach their refuge in the mountains later that same year. As they crossed Iowa, they used established territorial roads as far as Bloomfield; from that point they followed routes that were often no more than Indian trails. In the early spring, they had to stay close to Missouri settlements where they could buy feed for their animals, but when grass began to grow, they were able to take the more direct route they originally had planned to follow, northwest toward the mouth of the Platte.[3] After they reached the Missouri River near present-day Council Bluffs, their plans were changed significantly. When five hundred of their strongest men were recruited by the United States Army and became the Mormon Battalion, the pioneers realized they couldn’t reach the Rocky Mountains that season, so they went into Winter Quarters, just north of present-day Omaha.

In the spring of 1847, the pioneer company assembled at the Platte River near Fremont, Nebraska, to recommence the trek west. In recent years, this river had become a major route for westward-bound settlers. The famed Oregon Trail, which originated about two hundred miles further south at Independence, Missouri, angled northwest to connect with the Platte near Kearney.

The Mormons had started on the north side of the Platte and found it easier to stay on that bank during the first five hundred miles of their trek rather than cross this very large river.

When they reached Kearney, where the Oregon Trail began following the river’s south bank, the Mormons deliberately chose to stay on the north side in order to avoid conflicts with other travelers, even though this required them to break a new trail. On May 4, the pioneers met some traders heading east. They encouraged the Saints to cross over to the south side of the river, where there was a better road already in existence. Furthermore, this would avoid the necessity of crossing the Platte twice upstream, which could be done only by ferry. William Clayton, the official clerk for the company, recorded, “The subject was then talked over and when it was considered that we are making a road for thousands of saints to follow, and they cannot ford the river when the snow melts from the mountains, it was unanimously voted to keep on this side as far as Fort Laramie at least.”[4] Wilford Woodruff, one of the Apostles, recorded the reasons for this decision:

When we took into consideration the situation of the next company and thousands that would follow after and as we were the pioneers and had not our wives and children with us, we thought it best to keep on the north side of the river and brave the difficulties of burning prairies and make a road that should stand as a permanent route for the saints independent of the old emigration route and let the river separate the emigrating companies that they need not quarrel for wood, grass, or water. And when our next company came along the grass would be much better for them than it would on the south side as it would grow up by the time they would get along.[5]

In the upper plains of western Nebraska, however, the Mormons entered the broken up land, which one pioneer described as “one of the wildest looking places I ever passed through.”[6] This terrain limited their options. At Fort Laramie, just inside present-day Wyoming, for example, the Mormon pioneers had to cross the Platte River and join the main Oregon Trail. At this point, the trail “struck west and away from the Platte, over parched hills in order to circumvent a wild river country.”[7] Near Casper, the trail crossed the Platte for the last time and then followed the Sweetwater Valley for about one hundred miles, crossing the Sweetwater several times. It then continued through South Pass and then on to Fort Bridger.

At this point, the pioneers could have continued north along the Oregon Trail to Soda Springs (now in Idaho) and then followed the Bartleson Trail along Bear River into the Great Salt Lake Valley, but Jim Bridger and Sam Brannan counseled them to follow the Hastings Cutoff to the southwest instead. This route, taken by the Reed-Donner party the year before, would be one-third the distance. However, following “a barely visible trail, they encountered some of the most difficult mountain trail” so far.[8]

Reaching the base of Echo Canyon, the pioneers had another choice. They could turn to the right and follow Weber Canyon down into the Salt Lake Valley, but Orson Pratt, as well as explorers the year before, ruled out this route for wagons, as it was “blocked up by the rocks, some places could not see two wagons ahead.”[9] Instead, they followed the Donners’ trail south into East Canyon and up Big Mountain, where they had the first view of the Valley. They then descended into Mountain Dell Creek and then over Little Mountain into Emigration Canyon. Near the mouth of that canyon, Orson Pratt and others departed from the trail the Donners had used the year before, creating their own road along the creek, “thus avoiding the strenuous Donner Mountain climb.”[10]

William Clayton, the camp clerk, recorded the following:

We found the [Donner] road crossing the creek again to the north side and then ascending up a very steep, high hill. It is so very steep as to be almost impossible for heavy wagons to ascend and so narrow that the least accident might precipitate a wagon down a bank three or four hundred feet—in which case it would certainly be dashed to pieces. Colonel Markham and another man went over the hill and returned up the canyon to see if a road cannot be cut through and avoid this hill. . . . Brother Markham says a good road can soon be made down the canyon by digging a little and cutting through the bushes some ten or fifteen rods. A number of men went to work immediately to make the road which will be much better than to attempt crossing the hill and will be sooner done.[11]

Trails historian Stanley Kimball therefore asserted, “The Mormons of 1847 actually blazed only about one mile of the entire trail from Nauvoo to Salt Lake City—the remaining mile from Donner Hill into the valley.”[12]

The pioneers felt a great sense of relief when they finally entered the Salt Lake Valley. One of them observed, “The mountains came almost together at the bottom. But when we got through it seemed like bursting from the confines of a prison.”[13] The pioneers had succeeded in improving a trail for over a thousand miles that other wagon trains would follow for more than two decades.

The Coming of the Railroad

The annexation of Texas in 1845, of Oregon the following year, and of the American Southwest in 1848 set the stage for considerable interest in a transcontinental railroad. The opening of China and Japan to Western trade at about this same time made a rail link to the Pacific coast even more attractive. The gold rush of 1849 focused yet more attention on the need for improved transportation west.

The early 1850s witnessed an increase in railroad fervor. Rail mileage in the United States mushroomed from 8,800 in 1850 to 21,300 just four years later.[14] Various cities vied for the honor of becoming the midwestern jumping-off point. Each section of the country wanted the anticipated economic advantage that the transcontinental railroad and trade with the Far East would bring. Because it was generally assumed that the economy could support only one transcontinental road, this rivalry became intense.[15] Therefore, in 1853, Jefferson Davis, the secretary of war, authorized surveys to scientifically compare the advantages of five proposed routes.

The secession of the Southern states and formation of the Confederacy in 1861 diverted attention from building a railroad to the West Coast. This left the Northern states alone in the competition for the transcontinental route. On July 1, 1862, Congress passed the legislation authorizing construction of the new railroad. Significantly, it was to be called the Union Pacific (UP), most likely because it would link the North, or Union, with the Pacific coast. Brigham Young immediately invested $5,000 in stock, and three years later he became one of the railroad’s directors.[16]

Even though the Mormons were located far to the west of the anticipated jumping-off points, their interest in railroads came early. Historian Edward Tullidge claimed, “It is a singular fact, yet one well-substantiated in the history of the West, that the pioneers of Utah were the first projectors and the first proposers to the American nation of a transcontinental railroad.”[17] Perhaps he overstated the case, but there is no doubt but that the Saints were early advocates for this concept.

On March 3, 1852, Utah’s first territorial legislative assembly memorialized Congress, urging the construction through Utah of “a national central railroad from some eligible point on the Mississippi or Missouri Rivers to San Diego, San Francisco, Sacramento, or Astoria.”[18] Then, on January 14, 1854, Utah’s legislature adopted yet another memorial to Congress recommending that a railroad be built essentially along the route of the pioneers—from Council Bluffs up the Platte River and then across the Laramie Plains. Specifically, they proposed that the line should cross the Green River near the mouth of Henry’s Fork, follow that stream for a distance, cross the headwaters of the Bear, and then reach the upper Weber River. It would then proceed south across the Kamas Prairie and then follow the Provo River into Utah Valley. “A Railroad could branch from this most eligible point,” the legislature argued, “to Oregon, on the one hand, and to San Diego on the other.”[19]

Brigham Young later reflected, “I do not suppose we traveled one day from the Missouri River here, but what we looked for a track where the rails could be laid with success, for a railroad through this Territory to go to the Pacific Ocean. This was long before the gold was found, when this Territory belonged to Mexico. We never went through the cañon, or worked our way over the dividing ridges without asking where the rails could be laid; and I really did think that the railway would have been here long before this.”[20]

Ground was broken for the Union Pacific Railroad at Omaha on December 1, 1863, but construction did not get under way until the end of the Civil War two years later. By this time, overland migration had become focused on the Platte River Valley, with Council Bluffs as the preferred point to cross the Missouri River. Not surprisingly, the new rail line was to begin at Council Bluffs. Grenville M. Dodge, the Union Pacific’s chief engineer, explored the route from that point, “obtaining from voyagers, immigrants and others all the information [he] could in regard to the country further west.” Specifically, Dodge acknowledged, “From my explorations and the information I had obtained with the aid of the Mormons and others, I mapped and made an itinerary of a line from Council Bluffs through to Utah, California and Oregon, giving the camping places for each night, and showing where wood, water and fords of streams could be found.”[21] Thus the experience of the Mormon pioneers contributed to the understanding of those who planned the railroad nearly two decades later.

In 1863, Thomas C. Durant, vice president of the Union Pacific, instructed Peter A. Dey “to organize parties for immediate surveys to determine the line from the Missouri River up the Platte Valley, to run a line over the first range of mountains, known as the Black Hills [Wyoming’s Laramie Mountains], and to examine the Wasatch range.”[22] Interestingly, these mountain ranges would be the only two places where the railroad would depart in any significant way from the route marked out by the Mormon pioneers. Railroad planners still needed water for their steam locomotives but obviously were not concerned about feed for animals. Instead, they wanted coal and timber to be easily accessible. They couldn’t go up grades as steep as had wagon trains, but construction equipment enabled them to tunnel through mountains and ford smaller streams; only bridges across larger rivers posed greater challenges. They favored straight lines and sweeping curves in order to facilitate faster speeds for their trains.

While returning from an expedition to the Powder River, Dodge had discovered a pass over the Black Hills “and gave it the name Sherman, in honor of my great chief [Gen. William T. Sherman].”[23] Descending the east slope of the pass, they encountered American Indians. “I then said to my guide that if we saved our scalps,” Dodge recorded, “I believed we had found the crossing of the Black Hills.”[24] This would become the route of the railroad west from Cheyenne.

By June 1, 1867, UP rails had reached North Platte. Just west of there, Dodge departed from the earlier pioneer trails and instead headed directly towards his recently discovered pass. He “marched immediately up the [South] Platte, then up the Lodge Pole to the east base of the Black Hills.” Military authorities had decided to “locate the end of the division” at Crow Creek, which he named Cheyenne.[25]

Dodge pointed out that he had also considered the Mormon pioneer route “by the way of the North Platte, Fort Laramie, Sweet Water Creek and the South Pass, reaching Salt Lake by the way of the Big Sandy and Black Fork. This line avoided the crossing of the Black Hills and the heavy grade ascending from the east to the summit and ninety-foot grade dropping down into the Laramie plains [Union Pacific’s famed Sherman Hill], but this line was some forty miles longer than the direct line by the Lodge Pole, and on this line there was no development of coal as there was on the line adopted by the company, and on presenting this question to the Government, they decided against the North Platte and South Pass line.”[26] This therefore accounted for the railroad’s first major deviation from the earlier pioneer trail.

Meanwhile, in the spring of 1854, as part of Jefferson Davis’s railroad surveys, Lieutenant E. C. Beckwith was assigned to explore the forty-first parallel route west of Fort Bridger. His report concluded that a passage through the Wasatch Mountains “may be effected by following Weber River, or by ascending to near the sources of the Timpanogos [Provo River] and descending that stream—both being affluents, directly or indirectly, of the Great Salt Lake.”[27]

In 1864 the UP appointed Samuel B. Reed to survey the route from the Green River into the Great Basin. Specifically, Dey instructed him to check out the very route the Mormons had pioneered east of the Wasatch: “The first line should start from Great Salt Lake City and run up the valley to the point where the Weber breaks through the Mountains, thence up the Valley to either Echo Creek or Morine fork called on some maps White Chalk Creek to the summit then down to Bear River from there to some branch of Blacks fork and probably following it to a point nearly opposite the mouth of Bitter Creek thence across the table land to Green River.”[28]

By late May, Reed was in Salt Lake City, where he was amazed at what he saw: “I have never been in a town of this size in the United States where everything is kept in such perfect order. No hogs or cattle [are] allowed to run at large in the streets and every available nook of ground is made to bring forth fruit, vegetables or flowers for man’s use.”[29]

Brigham Young provided Reed with teams, tents and other gear, and fifteen men. This party first explored Weber Canyon, discovering that the profile was, as Reed reported, “much more favorable than I expected to find.”[30] At Brigham’s direction, Mormon settlers along the way provided the surveyors with food. Reed continued his exploration east to Green River before returning to Salt Lake City by mid-August. Here he “pitched his tent in Brigham Young’s yard.”[31] The next day he received a telegram from UP headquarters instructing him to explore a second route through Provo Canyon. This would occupy another two months in the mountains. Following these extensive explorations, Reed still concluded that Weber Canyon was the “best line that [could] be found through the Wasatch range.”[32] The boulders which had discouraged the pioneers from taking their wagons through this canyon could now be removed by railroad builders with their machinery, so the rails did descend through Weber Canyon—the second major departure from the pioneer’s route. At Promontory Summit, about fifty miles north of Salt Lake City, the Union Pacific met the Central Pacific, which had been built east from California. The transcontinental railroad was formally completed with the driving of the golden spike on May 10, 1869.

Some national leaders thought that building the railroad would solve what they called the “Mormon problem.” For example, in writing to his friend Grenville Dodge, William T. Sherman asserted, “I regard this road of yours as the solution of the Indian affairs and the Mormon question, and therefore, give you all the aid I possibly can.”[33] Such statements by leaders may seem ironic in the light of Brigham Young’s interest in railroads and because, with Brigham Young’s personal encouragement, Mormon groups formed construction companies that contracted with both railroads to build the final segments of their line.

The Advent of the Automobile

The turn of the twentieth century brought yet another form of transportation—the automobile. Although self-propelled personal vehicles were invented earlier, they became more popular following the creation of the first assembly line by Ransom Olds in 1901 and especially following Henry Ford’s perfection of this manufacturing technique in 1913.[34] Slowly at first, new roads were created for the growing number of motorists. Yet a different set of challenges faced the planners of these roadways when compared to railroad builders. Automobiles could climb steeper grades and make tighter turns than could a railroad train. The general goal was to follow the shortest available routes between neighboring towns or population centers.

There was no single coast-to-coast highway, and a transcontinental trip was estimated to require “sixty days—ninety if difficulties were encountered.” One observer insisted that taking such a trip could be enjoyable, if one were willing to repeatedly “change tires and dig their car out of sand pits or mud holes.”[35] In 1913, the Lincoln Highway Association published the route of its proposed bridge across America, from New York to California. In many areas it would follow existing rail routes, but in others it would strike out on its own.

The Lincoln Highway crossed the Mississippi into Iowa at Clinton and then generally followed the route of the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad across the northern part of that state. This route was more level than the central route through Des Moines or the more southerly route taken by the Mormon pioneers.[36]

In Nebraska, the highway generally followed the Union Pacific Railroad. At first, the Lincoln Highway followed the stair-stepped boundaries between sections of land, requiring numerous rail crossings. These became the scenes of many fatal accidents and consequent delays for the railroad. Therefore, the UP was willing to give up some of its land so the highway could have a straighter route parallel to, rather than across, the tracks.[37] In many areas there were no fences to divide fields, “nothing but two ruts across the prairie.”[38]

In Wyoming, the highway continued to follow the general route of the railroad. The roadway often ran along ranch fences but sometimes crossed them, creating a new set of challenges. A 1912 motorist reported, “When we came to one of these we found a gate across the road, which had to be opened and closed. It said so right on the gate. And some days we would open and close dozens of these gates.”[39] East of Laramie, this motorist actually had to drive through a herd of cattle.

The highway continued along the UP tracks as it entered Utah through Echo Canyon. The original plan was to then head south and enter the Salt Lake Valley via Parley’s Canyon. Governor William Spry, however, insisted that the route pass through Ogden, Utah, first on its way to Salt Lake City. Interestingly, one argument advanced in favor of this route was that there were already two paved miles between the two cities, near Farmington, Utah. This existing pavement, even though minimal, was actually thought of as a major advantage. Eventually, however, the highway was built through Parley’s Canyon, thus following the route of the 1847 pioneers more closely than had the railroad.

Specifically, the highway entered Salt Lake Valley through Parley’s Canyon rather than via the route over the mountains. Since their 1847 arrival in the valley, the pioneers had sought an easier route for those who would come later. Parley P. Pratt, one of the Twelve Apostles, was impressed with Big Canyon (as Parley’s Canyon was originally known) and convinced the high council of Deseret to sponsor his exploring it further. He did so in June 1848 and reported that a better road could be constructed through this canyon. The infusion of capital as a result of the 1849 gold rush made such a road-building venture practicable. Pratt opened his “Golden Pass” the following year. One of the first issues of the Deseret News announced that this improved connection through the Weber River and the Salt Lake Valley would open on July 4, 1850, “avoiding the two great mountains, and most of the Kanyons so troublesome of the old route.”[40] Although it was a toll road, it quickly became the route of choice. The Lincoln Highway followed this variation on the pioneer trail and then entered Salt Lake City via 21st South and State Streets.[41]

A significant refinement of the existing highway system came in 1956 with the Federal-Aid Highway Act, signed into effect by Dwight D. Eisenhower. The 2,907 miles of Interstate 80 formed the first interstate highway spanning the continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific. It opened on August 22, 1986. Interestingly, the formal dedication of this highway took place only about fifty miles from the spot where the driving of the golden spike had completed the transcontinental railroad over a century earlier.[42]

Unlike earlier highways that typically connected nearby towns, the interstates typically followed the optimum routes between major urban centers, often leaving smaller communities off to one side. Modern heavy-duty construction equipment enables highway builders to create larger cuts and fills, creating “straight, smooth highways, with wide lanes and gentle banked curves designed for speed,” meaning that details of local topography have much less influence on the location or course of the freeways.[43] In Nebraska, planners of Interstate 80 found it politically expedient to depart from the Union Pacific’s more direct route in order to pass through the state capital, Lincoln, before heading to Omaha.

Conclusion

In sum, it seems that in pioneer times, topography was the major influence affecting the choice of routes. The Platte Valley offered abundant water and feed, as well as easy grades. South Pass was a convenient break in the Rocky Mountain barrier. The Latter-day Saints generally followed already existing routes—the Oregon Trail to Fort Bridger and the Hastings Cutoff from there into the Salt Lake Valley (except the last mile).

Technology became an increasingly important factor over the years. Machinery enabled builders of the Union Pacific to remove obstacles and make Weber Canyon a passable route. For similar reasons, highway builders were able to use Parley’s Canyon, which had not been accessible to the first pioneers. Heavier-duty equipment enabled designers of the interstates to create even more efficient roadways. While the railroads influenced where settlements would be established and where population would grow, the roles were reversed as automobile highways were routed to connect existing population centers.

Nevertheless, the route of the pioneers is still essentially followed by Interstate 80. The only major departure, in Wyoming, was made by the railroad in the 1860s and has been followed by subsequent highways. Therefore, the route improved by the Mormon pioneers is still, for the most part, the route of the iron horse and horseless carriage.

Notes

[1] For an excellent discussion of the pioneer’s westward trek, see Richard E. Bennett, We’ll Find the Place: The Mormon Exodus, 1846–1848 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1997).

[2] Quoted in Howard W. Hunter, “The Oakland Temple—Culmination of History,” Improvement Era, February 1965, 140.

[3] Stanley B. Kimball, Historic Sites and Markers Along the Mormon and Other Great Western Trails (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 21, 35; see also Stanley B. Kimball, Discovering Mormon Trails (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1979), 14.

[4] William Clayton’s Journal (Salt Lake City: Clayton Family Association, 1921), 130.

[5] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal 1833-1898 Typescript, ed. Scott G. Kenney (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1983), 3:168.

[6] Bennett, We’ll Find the Place, 148.

[7] Bennett, We’ll Find the Place, 180.

[8] Bennett, We’ll Find the Place, 208.

[9] Journal of Thomas Bullock, July 16, 1847.

[10] Bennett, We’ll Find the Place, 216.

[11] William Clayton’s Journal, 307.

[12] Allan Kent Powell, Utah History Encyclopedia (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1994), 380.

[13] Bennett, We’ll Find the Place, 216.

[14] Paul Neff Garber, The Gadsden Treaty (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1959), 19.

[15] William H. Goetzmann, Army Exploration in the American West, 1803–1863 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1959), 263.

[16] Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints 1830–1900 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1958), 236–37.

[17] Quoted in “Utah Railroads,” Daughters of Utah Pioneers lesson booklet for November 1966, in Our Pioneer Heritage, (comp. Kate B. Carter, Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1967), 10:137.

[18] Acts, Resolutions, and Memorials (Salt Lake City: Brigham Young, 1852), 225.

[19] Acts, Resolutions, and Memorials (Salt Lake City: Brigham Young, 1854), “Memorial in Relation to Pacific Railway,” approved January 14, 1854.

[20] “The Mass Meeting,” Deseret Evening News, June 11, 1868, 3.

[21] Grenville M. Dodge, How We Built the Union Pacific Railway and Other Railway Papers and Addresses (Council Bluffs, IA: Monarch Printing, 1866–70), 8: The author is not aware of any other references to the Mormons helping Dodge.

[22] Dodge, Union Pacific, 8, 13, 20–23.

[23] Dodge, Union Pacific, 20.

[24] Dodge, Union Pacific, 21.

[25] Dodge, Union Pacific, 23.

[26] Dodge, Union Pacific, 22.

[27] “Report of the Secretary of War Communicating the Several Pacific Railroad Explorations,” 3 vols. (33rd Cong. 1 Sess, 1855), 1:15–16.

[28] Letter from Peter A. Dey to Samuel B. Reed, April 25, 1864, quoted in “Railroads and the Making of Modern America,” University of Nebraska–Lincoln, http://

[29] Maury Klein, Union Pacific: Birth of a Railroad, 1862–1893 (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1987), 53.

[30] Samuel B. Reed, Report of Samuel B. Reed of Surveys and Explorations from Green River to Great Salt Lake City (Omaha, NE: Union Pacific Railroad, 1864), 4.

[31] Klein, Union Pacific: Birth of a Railroad, 54.

[32] Reed, Report of Samuel B. Reed, 9–11.

[33] Dodge, Union Pacific, 17.

[34] Robert W. Domm, Michigan Yesterday and Today (Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur Press, 2009), 29.

[35] For a good history of the Lincoln Highway, see Brian Butko, Greetings from the Lincoln Highway (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2005).

[36] Butko, Lincoln Highway, 124–25

[37] Butko, Lincoln Highway, 145–46.

[38] Butko, Lincoln Highway, 180.

[39] Butko, Lincoln Highway, 180.

[40] Parley P. Pratt, “The Golden Pass! Or, New Road through the Mountains,” Deseret News, June 29, 1850, 1; see also Terryl Givens and Matthew Grow, Parley P. Pratt: The Apostle Paul of Mormonism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 278–80.

[41] Butko, Lincoln Highway, 204.

[42] Dan McNichol, The Roads That Built America (New York: Barnes and Noble, 2003), 119.

[43] McNichol, Roads That Built America, 112.