Cartographic Representations of the American West on the Eve of the Mormon Exodus

Douglas Seefeldt

Douglas Seefeldt, “Cartographic Representations of the American West on the Eve of the Mormon Exodus,” in Far Away in the West: Reflections on the Mormon Pioneer Trail, edited by Scott C. Esplin, Richard E. Bennett, Susan Easton Black, and Craig K. Manscill (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 1–21.

Douglas Seefeldt was an assistant professor of history at Ball State University when this was written.

The history of western exploration is as much intellectual history as it is the story of voyages, routes, trails, and landscapes. In many ways, every exploration begins with a trip taken in the imagination by remembering ancient lore, reading venerable texts, and examining the latest reports from predecessors in the forms of expedition journals, maps, and charts, all from the safety and relative comfort of the study, the library, or the mercantile office. A body of maps and journals created by cartographers and explorers influenced the course of empire from America’s colonial era through the revolutionary period and on to the establishment and expansion of the early republic. Men of westering vision, such as Thomas Walker and James Maury, Thomas Jefferson and Meriwether Lewis, and Heber Kimball and Brigham Young, all studied and interpreted these documents—comprising part fact and part fantasy—as they sought to understand and exploit the promises that the West presented. Led by their imaginations and the maps such visions created, American military explorers and religious colonizers alike went off into the unknown, prepared to find what it was they sought, be it the contest for commercial opportunities that attracted an expanding young nation or the preordained haven from persecution that drew a beleaguered band of Latter-day Saints to the Far West.

Inventing the West

The idea of the West defines Western civilization and has animated debate over the fate of nations, in one form or another, for a very long time. Historian Loren Baritz describes this idea as a composite vision made up of many strands, including the intellectual yearning for a place of eternal life as well as the motivation behind the imperial destiny of nations, drawing them ever westward. Entangled within these strands, Baritz contends, are the many ideas of the West, “a west that might be either a place, a direction, an idea, or all three at once.”[1] What was out there, in the minds of the ancient Greeks contemplating the Elysian Plain and the ancient Romans seeking the Islands of the Blest, embedded in the medieval Irish pagan stories of the Isle of Fair Women and Celtic Christian tales of the voyages of St. Brendan, was the idea of a west to be discovered and put to use for economic opportunity or religious salvation, an idea that was carried down through the ages to the Enlightenment explorers and cartographers. From this seventeenth-century Christianized idea of the West, Baritz argues, “eighteenth-century Americans secularized it by recalling the west of empire.”[2] Perhaps best articulated by the nineteenth-century imperial doctrine of manifest destiny, the combined secular and the sacred ideas of the West motivated the emerging nationalistic expansion across the continent. A project that began, as Baritz notes, over two thousand years ago with the Augustan poet Horace, extended across the millennia to the mid-nineteenth-century American newspaper publisher Horace Greeley.[3] “Maps are complex constructions,” geographer John Rennie Short contends in his study of cartography and national identity Representing the Republic: Mapping the United States, 1600–1900. They are more than text; a map is “also a theory, a story, a claim, a hope, a scientific document, an emotional statement, an act of imagination, a technical document, a lie, a truth, an artifact, an image, an itinerary, a mode, an inscription and a description.”[4]

After Lewis and Clark

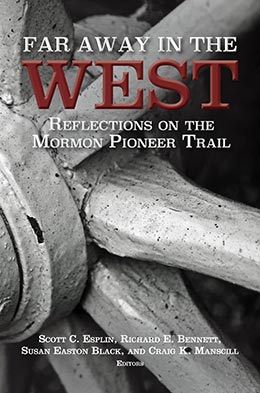

Despite the best efforts of generations of cartographers, very little was truly known about the geography of the trans-Mississippi West. Even after over two centuries of North American mapmaking, cartographers could not agree on the height or extent of the Rocky Mountains; it was simply known that they existed. For example, Aaron Arrowsmith and Samuel Lewis’s New and Elegant General Atlas, published in 1804, contained two maps showing the West. One of them displayed an empty region beyond the Mississippi River, while the map titled “Louisiana” depicted several breaks through the “Mt. de le Roche, or Stoney Mts.” range that could enable a passage to the Pacific (see figure 1).[5] This map is based on a map drawn in the 1790s by a St. Louis surveyor named Antoine Soulard for the Spanish governor of Louisiana. While Soulard’s original map was obscured by the secrecy of the geopolitical contest for North America, his representation of the upper Mississippi River Basin and Missouri River Basin came to the attention of the public a decade or so later by way of Arrowsmith and Lewis’s Atlas. Carl I. Wheat, one of the preeminent historians of cartography, considers this map to be “the most ambitious, and—despite its many obvious infirmities—the most informative published attempt to portray the West and Northwest of what is now the United States.” This map serves as an important document of the geographical ideas prevalent prior to the publication of William Clark’s map in 1814.[6]

Figure 1. Samuel Lewis, “Louisiana,” in Aaron Arrowsmith and Samuel Lewis, A New and Elegant General Atlas, 1804. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Figure 1. Samuel Lewis, “Louisiana,” in Aaron Arrowsmith and Samuel Lewis, A New and Elegant General Atlas, 1804. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

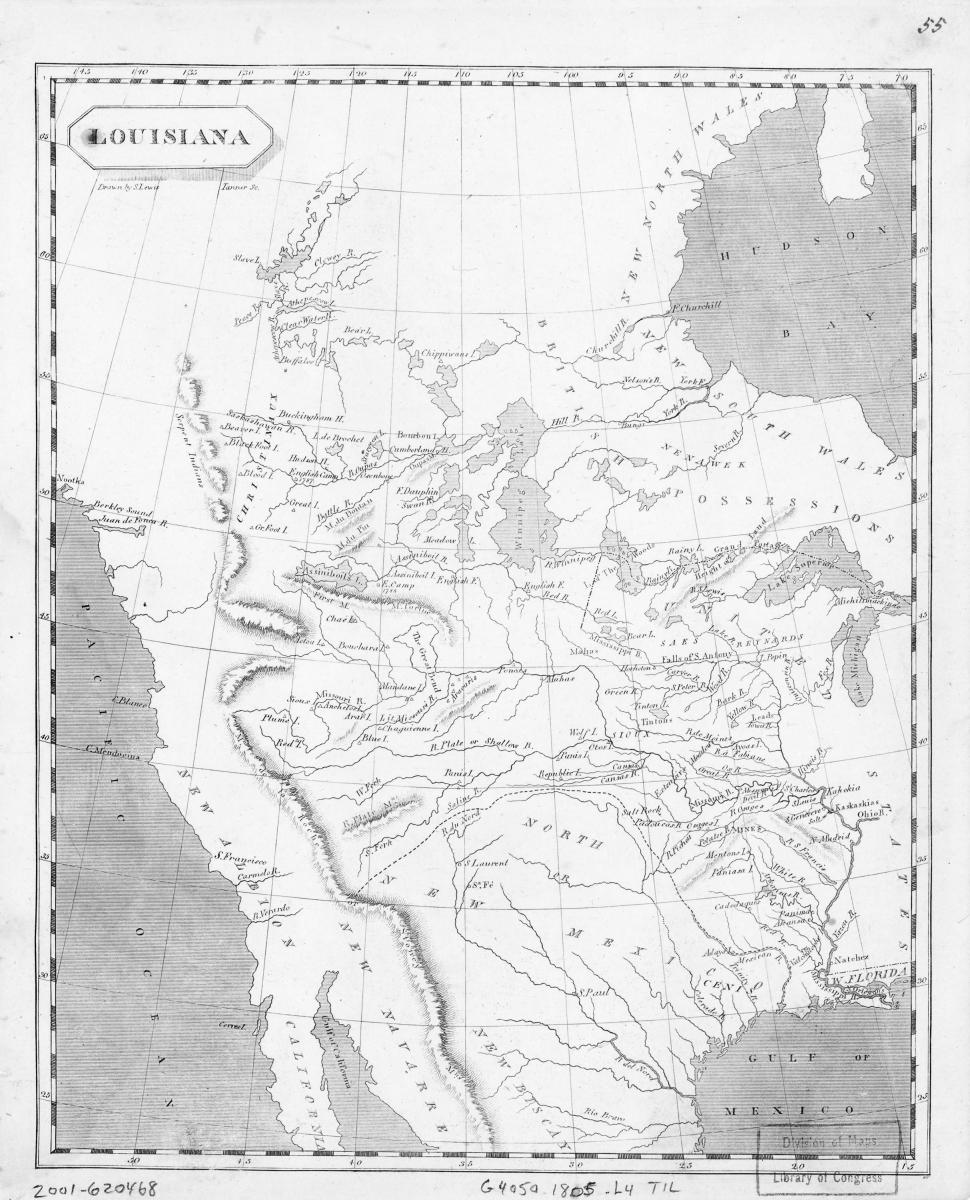

A skillful cartographer by practice, not by formal training, Clark served as the primary mapmaker for the Lewis and Clark expedition and created all but two of the sixty maps contained in the expedition journals. Clark’s task was to compile his firsthand cartographic data from the expedition with information gleaned from contemporary maps and other western explorers active in the years immediately following his return from the Pacific Ocean. During the expedition’s winter 1804–spring 1805 layover at Fort Mandan, Clark created a large map that that was forwarded along with Meriwether Lewis’s notes to Thomas Jefferson in April 1805. Clark’s map, “compiled from the Authorities of the best informed travellers,” features a representation of the West “laid down principally from Indian information” (see map). Once received by the War Department, the map was sent to Nicholas King, who copied it in pen-and-ink and watercolor (see figure 2). This map represents that Lewis and Clark had, even by this point in the expedition, gathered more specific information about the region than had any previous explorers, but this vast amount of new data gave the misconception of the scale of the Missouri River and its tributaries as it promoted the idea of merely “eight days march to the Missouri” (see map) from a tributary of the Columbia River. Or, as geographer John Logan Allen concludes, “The overextension of the Missouri basin toward the Pacific was the consequence more of the expansion of known or partly known geography to fill areas of terra incognita than of any other single factor.” This map, for all of its added detail, presents little more than a reaffirmation of earlier colonial depictions of geographical concepts of the pyramidal height-of-land theory, the symmetrical continental river system, and the short portage to the “Great River of the West” that will provide the passage to India.[7] King would make a similar map using information from expedition notes recorded during the winter of 1806 at Fort Clatsop on the Oregon coast; these notes depicted the trip west from Fort Mandan and the return trip from the Pacific coast to St. Louis.[8]

Figure 2. William Clark, “Map of Part of the Continent of North America,” 1805. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Figure 2. William Clark, “Map of Part of the Continent of North America,” 1805. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

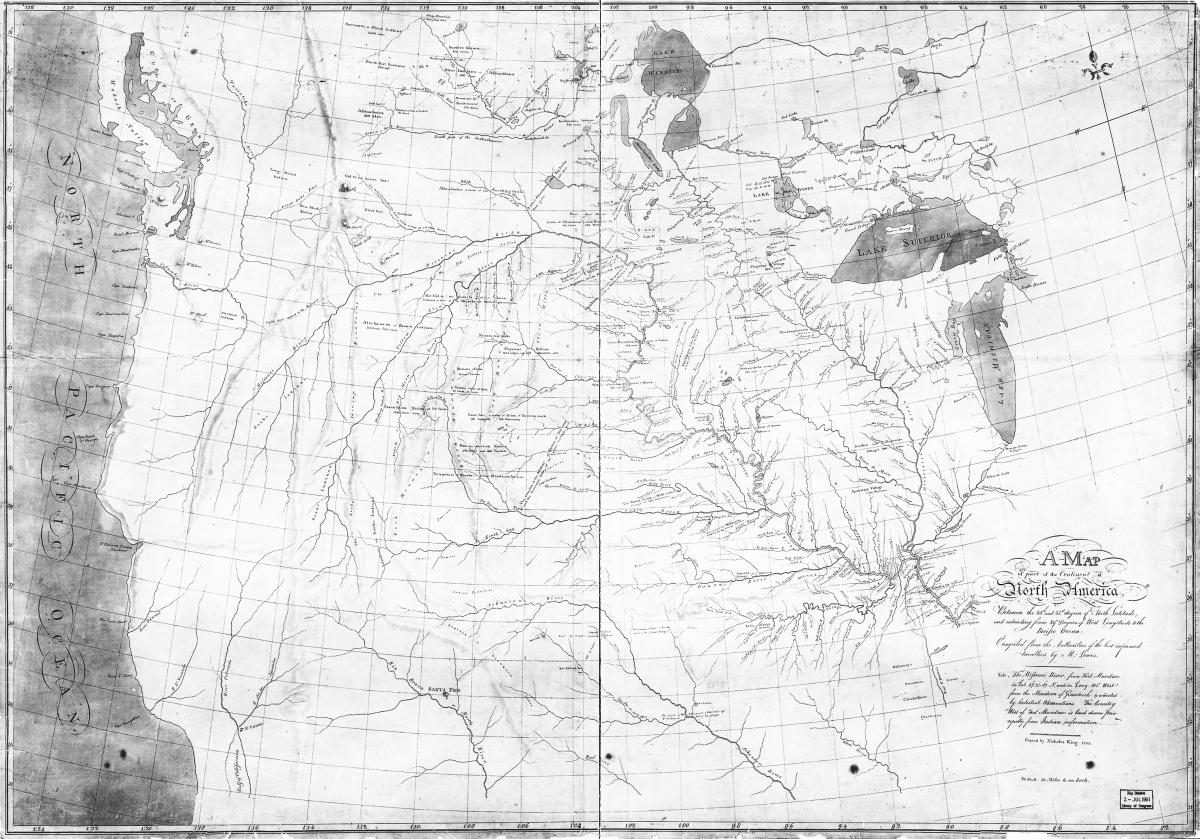

In the years that he was posted in St. Louis as superintendent of Indian affairs for the Louisiana Territory, William Clark made another important map based on data collected from his own field observations and the reports of just about every trader and trapper who went up the Missouri River. The mountain men John Colter and George Drouillard (both members of the Lewis and Clark expedition), along with various Astorian fur traders, gave Clark firsthand information on the Yellowstone River and Big Horn Basin geography during visits to St. Louis in 1808.[9] Referred to as “Clark’s Map of 1810” by historians, the resulting collage in an extraordinary manuscript map went from simply hanging on Clark’s office wall to helping to shape new conceptions of western American geography once it was reproduced and widely distributed (see figure 3).[10]

Figure 3. William Clark, “Clark’s Map of 1810,” 1810. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Figure 3. William Clark, “Clark’s Map of 1810,” 1810. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

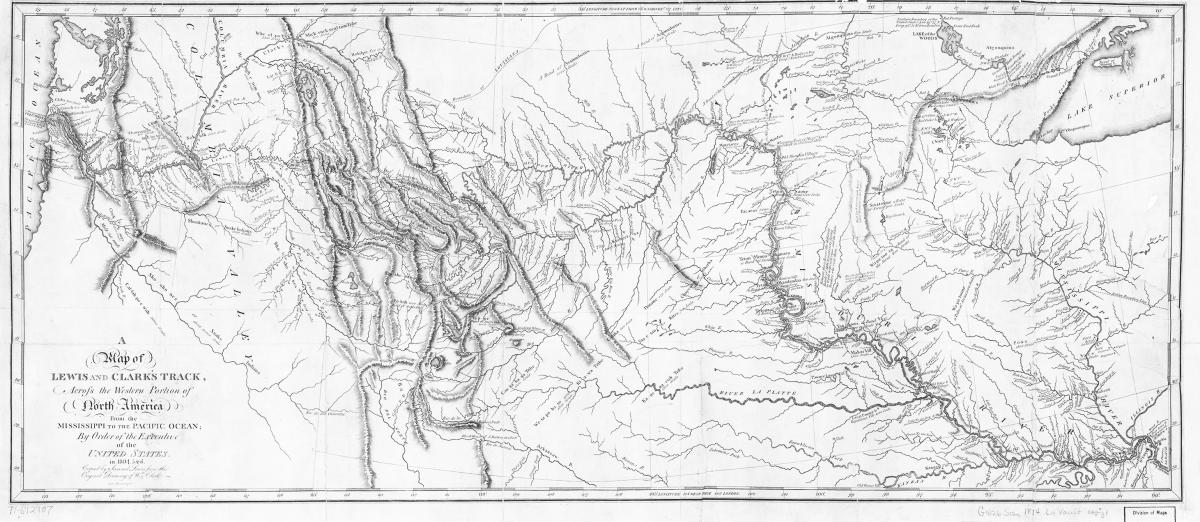

Clark’s manuscript map is significant in many ways on its own, but its greatest contribution is that it served as the source for Samuel Lewis’s engraving titled “Map of Lewis and Clark’s Track, across the Western Portion of North America from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean” that appears in Nicholas Biddle and Paul Allen’s two-volume edited narrative of the Lewis and Clark expedition that was published in 1814.[11] Biddle edited the scope of Clark’s manuscript map in order to focus viewers’ attention on the principal route traveled by Lewis and Clark (see figure 4). This engraving, “Copied by Samuel Lewis from the Original Drawing of Wm. Clark,” had a tremendous impact on subsequent maps and atlases of the western regions. Incorporating sophisticated references to established topographical features, this map ushered in a new generation of accurate cartographic representation of the American West. With its complex rendering of the Cascades and the Rocky Mountains, its precise locations of the headwaters of the Missouri and Columbia Rivers, and its accurate placement of the Continental Divide, this map influenced contemporary cartographers in England, France, and the United States, for three decades and played an important role in establishing American claims to the Northwest.[12] Wheat, writing a century and a half after the publication of the map, contends that the “1814 map was a progenitor of many later maps, and one of the most influential ever drawn, its imprint still to be seen in maps of Western America.”[13]

Figure 4. Samuel Lewis, “A Map of Lewis and Clark’s Track,” in History of the Expedition under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark, to the Sources of the Missouri, Thence across the Rocky Mountains and down the River Columbia to the Pacific Ocean. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Figure 4. Samuel Lewis, “A Map of Lewis and Clark’s Track,” in History of the Expedition under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark, to the Sources of the Missouri, Thence across the Rocky Mountains and down the River Columbia to the Pacific Ocean. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Ultimately, however, the Lewis and Clark expedition did little to disturb the well-established images of the West. Despite the accurate information that was increasingly made available by skilled mapmakers with information from firsthand observations, the interior of the region continued to be the place of fables and remained a blank spot upon which to project American hopes and fears for decades to come.

The West on the Eve of the Mormon Exodus

The last strand woven into the idea of the West was an old one, dating back at least to 1752 with the publication of Bishop Berkeley’s dictum “westward the course of empire takes its way,” that became so popular in America after it was frequently reprinted in magazines and newspapers during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.[14] The sacred West and the secular West fused together in the American experiment, a phenomenon best articulated in the mid-nineteenth-century United States by the concept of manifest destiny.[15] Even though he believed that Americans possessed “a chosen country, with room enough for our descendants to the thousandth and thousandth generation,” Thomas Jefferson would live to witness the beginning of the rapid movement westward in the early 1800s that would, within a century, expand the boundaries of the nation he helped found beyond even his substantial ambitions.[16]

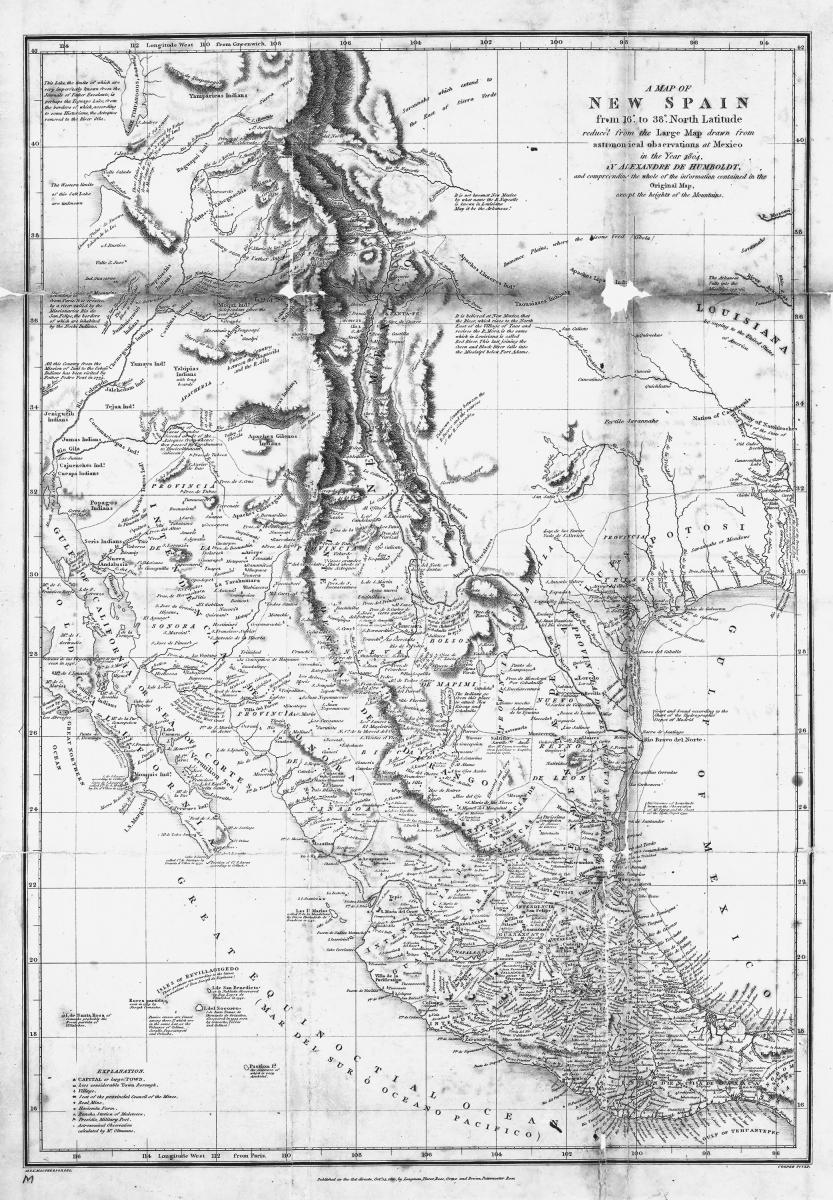

Expeditions launched during the first half of the nineteenth century and the maps created due to such expeditions reflected more detailed geographic information while simultaneously projecting an image of the providentially inspired expansion of the American empire ever westward. Reports published on the United States government expeditions led by Zebulon M. Pike (1806–7), Stephen H. Long (1819–20), and the four expeditions led by John C. Frémont (1842–48), along with information from the mercantile fur trappers and traders, Canadian explorers, emigrant trailblazers, reconnaissance conducted as part of the Mexican-American War, and the great Pacific railroad surveys, found an eager American readership who devoured it all. Some maps, like Alexander von Humboldt’s “A Map of New Spain,” published 1810, were more modestly circulated (see figure 5). This map accurately depicts the end of the era of maps created from Spanish sources and notes on its upper left-hand edge, “The Western limits of the Salt Lake are unknown.”

Figure 5. Alexander von Humboldt, “A Map of New Spain, from 16° to 38° North Latitude Reduced from the Large Map; Drawn from Astronomical Observations at Mexico in the Year 1804” (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1810). Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Figure 5. Alexander von Humboldt, “A Map of New Spain, from 16° to 38° North Latitude Reduced from the Large Map; Drawn from Astronomical Observations at Mexico in the Year 1804” (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1810). Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

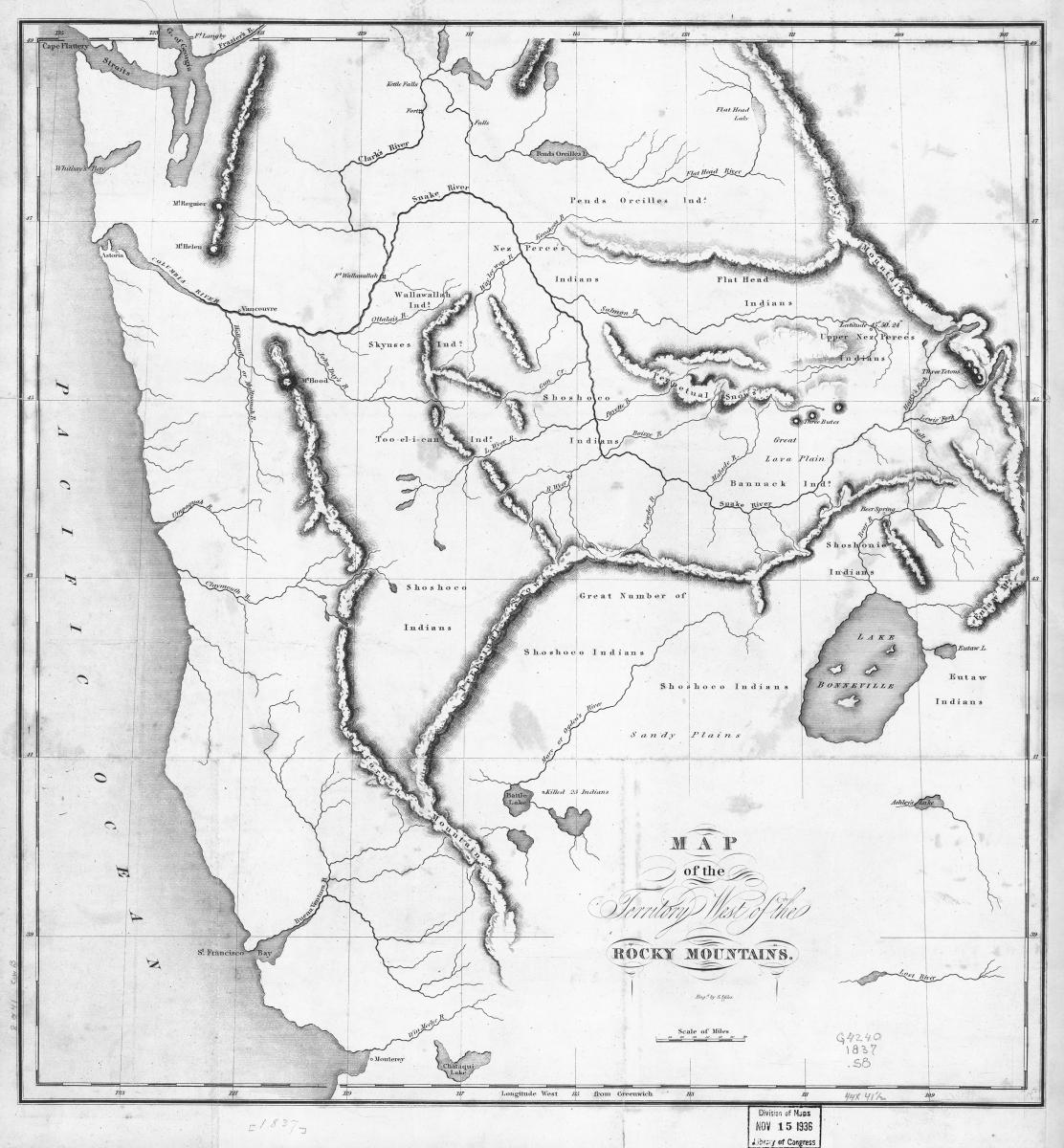

Other maps of the same area, like the ones made from the notes of Captain B. L. E. Bonneville’s failed fur trading venture from 1832 to 1834 and published in Washington Irving’s popular two-volume work, The Rocky Mountains; or, Scenes, Incidents, and Adventures in the Far West, enjoyed broad circulation and easy access to those interested in the West (see figure 6). His maps depict something approximating the Great Salt Lake—dubbed here “Lake Bonneville”—and the hydrography of the region in sufficient detail to dispel the long-standing myth of the source of the Rio Buenaventura, or Great River of the West, located at the highest point of land that, by process of elimination, had to be in either the Arctic or the Great Basin.[17] The latter has sparse, unnavigable rivers that “often dry up in the summer and, instead of flowing to the sea, end in salty lakes or sinks or disappear into the desert floor.”[18]

Figure 6. Benjamin Louis Eulalie de Bonneville, “Map of the Territory West of the Rocky Mountains,” in Washington Irving, The Rocky Mountains; or, Scenes, Incidents, and Adventures in the Far West; Digested from the Journal of Captain B. L. E. Bonneville, of the Army of the United States, and Illustrated from Various other Sources, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: Carey, Lea and Blanchard, 1837). Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Figure 6. Benjamin Louis Eulalie de Bonneville, “Map of the Territory West of the Rocky Mountains,” in Washington Irving, The Rocky Mountains; or, Scenes, Incidents, and Adventures in the Far West; Digested from the Journal of Captain B. L. E. Bonneville, of the Army of the United States, and Illustrated from Various other Sources, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: Carey, Lea and Blanchard, 1837). Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

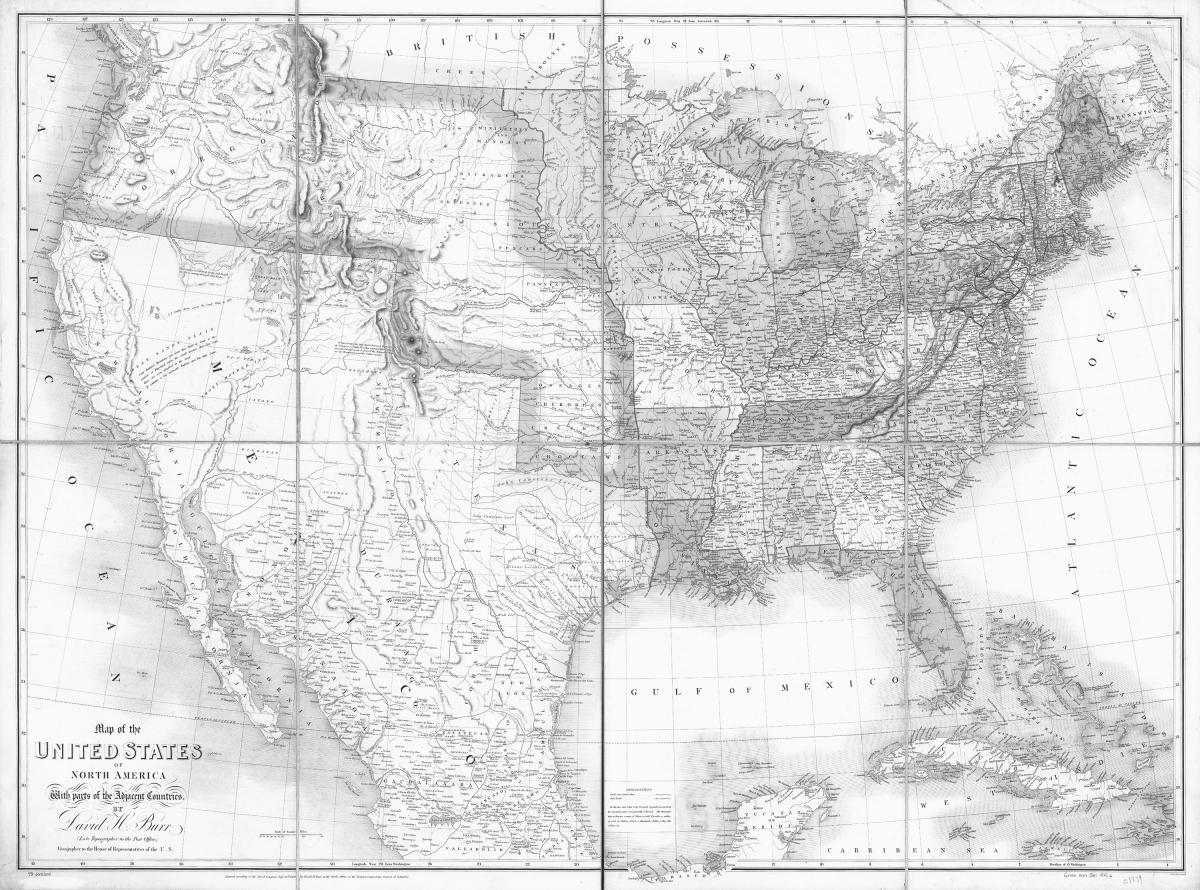

The tremendous 1839 map created by David Burr from information provided by fur trapper Jedediah Smith’s travels through the Great Basin during the 1820s is an important depiction of the empty part of the land west of the Rocky Mountains (see figure 7). Considered as the first American to enter California from the east and return back overland, Smith was one of the most significant, if largely unsung, explorers of the American West. Burr held the office of geographer to the U.S. House of Representatives and was given access to Smith’s maps by his former St. Louis fur trade partner General William Ashley, by then a member of Congress representing Missouri as a Jacksonian Democrat from 1831 to 1837. While Burr’s map had little influence at the time of publication, it stands today as a rare example of the intimate detail that the mountain men like Jedediah Smith could provide, even if in this case it was provided indirectly; Smith died at the age of thirty-three in a skirmish with Comanches along the Santa Fe Trail, leaving General Ashley to seek publication of Smith’s geographical information.[19]

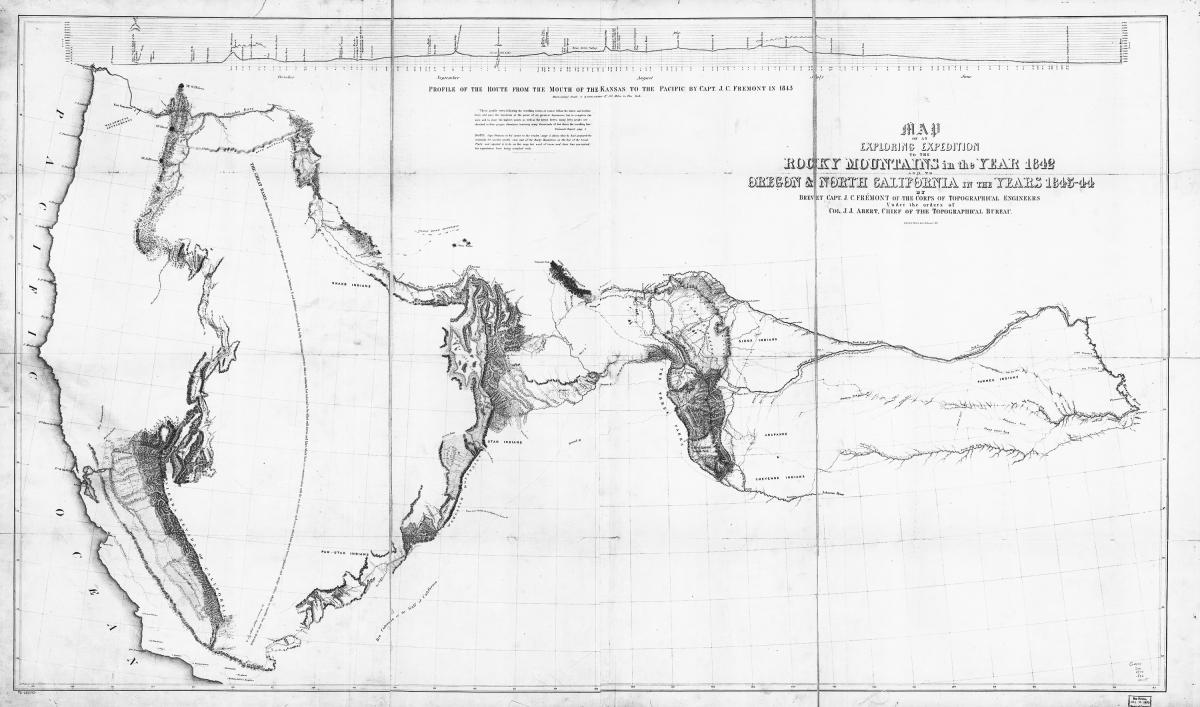

By the 1840s, more detailed information had been collected about the West than had been yet depicted on widely available maps. This situation was remedied in 1845 with the publication of Frémont’s reports of his 1843–44 trek to Oregon and California. These reports, composed from Frémont’s expedition-journal notes by Frémont and his wife, Jessie Benton Frémont—a talented writer and the daughter of the Democratic US senator Thomas Hart Benton, a staunch advocate of westward expansion—and the map that accompanied it were a publishing sensation on two continents. Congress authorized a ten-thousand-copy print run for sale to the public that provided fodder for national newspapers hungry to reprint excerpts of thrilling accounts of western exploration. The American edition went through six printings, a British edition went through two printings, and the work was even made available in translation to continental Europeans.[20]

The report’s map, drawn by German-born cartographer Charles Preuss, became the latest in the line of influential maps of the American West, following those by Clark and Long (see figure 8). Owing to the fact that Preuss only drew the areas covered by the expeditions, the considerable emptiness of the map makes it distinctive and gives it something of an air of accuracy. The map’s most striking feature is its emphasis of the “Great Basin,” and it also features the first accurate depiction of the Great Salt Lake. Historian Donald Jackson dubbed this map “the right map at the right time,” and James Ronda contended that “the nation was now ready to act on the information and vision expressed in the map.”[21]

The Gathering of Zion

The popular press dubbed Frémont “the Pathfinder” and elevated him to the lofty status of “the ideal symbol for a rising American Empire,” just as increasing numbers of emigrants took to the wagon roads.[22] Frémont had, in the words of historian Dale Morgan, “made the West neighbor to the nation’s mind,” and Mormon settlers would soon join this wave of migration westward to extend Thomas Jefferson’s “Empire of Liberty” across the continent.[23] Fueled by a keen sense of manifest destiny, American political leadership cast its eyes upon the Far West as the locus for national expansion. This line of thinking is evident in President John Tyler’s third annual message to Congress that he delivered in December of 1843, wherein he called for continued resolve in negotiations with Great Britain over ownership of the Oregon Territory.[24] Recognizing that American expansion into the region was well under way, Tyler remarked, “many of our citizens are either already established in the Territory or are on their way thither for the purpose of forming permanent settlements, while others are preparing to follow.” The president then renewed his call for “the establishment of military posts at such places on the line of travel as will furnish security and protection to our hardy adventurers against hostile tribes of Indians inhabiting those extensive regions.” He further notes that American law should follow, enabling the “free system of government” to develop the republican model in the West, “giving a wider and more extensive spread to the principles of civil and religious liberty.”[25]

Figure 7. David Burr, “Map of the United States of North America with Parts of the Adjacent Countries,” in The American Atlas (London: J. Arrowsmith, 1839). Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Figure 7. David Burr, “Map of the United States of North America with Parts of the Adjacent Countries,” in The American Atlas (London: J. Arrowsmith, 1839). Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Figure 8. Charles Preuss, “Map of an Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the Year 1842 and to Oregon and North California in the Years 1843–44 by Brevet Captain J. C. Frémont of the Corps of Topographical Engineers,” in Report of the Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the Year 1842, and to Oregon and North California in the Years 1843–44 (Washington, DC: Blair and Rives, 1845). Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Figure 8. Charles Preuss, “Map of an Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the Year 1842 and to Oregon and North California in the Years 1843–44 by Brevet Captain J. C. Frémont of the Corps of Topographical Engineers,” in Report of the Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the Year 1842, and to Oregon and North California in the Years 1843–44 (Washington, DC: Blair and Rives, 1845). Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

In the months before his death, American religious leader Joseph Smith would act on Tyler’s recommendation by requesting authorization from Congress to gather a hundred-thousand-man army to march into, settle, and govern Oregon, ostensibly to strengthen the northern border and prevent foreign intrusion from Britain. Smith also closely followed the events surrounding the conditions in the Texas Republic, and in 1844 he appealed to Congress for permission to raise a volunteer army to guard the Texas or Oregon frontiers while simultaneously entering into negotiations with the Republic of Texas with hopes of acquiring a strip of land along the border with Mexico where he might relocate his followers.[26] Smith sent Orson Hyde and Orson Pratt to Washington in early April 1844 to present memorials to Congress and inquire about Oregon and Texas. They arrived in Washington by April 23, 1844, and Hyde met with President John Tyler and Stephen A. Douglas, Illinois representative. From Douglas, Hyde received a map of Oregon and a report of Frémont’s first expedition containing the map of the expedition route drawn by Preuss.[27] Hyde wrote to Smith on April 26, 1844, to convey the details of this meeting: “Judge Douglass [sic] has given me a map of oregon, and also a Report on an exploration of the Country lying between the Missouri River and the rocky Mountains on the line of the Kansas, and great Platte Rivers: by Lieut. J. C. Fremont of the Corps of topographical Engineers. On receiving it, I expressed a wish that Mr Smith could see it. Judge D. says it is a public document, and I will frank it to him, I accepted his offer, and the book will be forth coming to him.”[28] Hyde returned to Nauvoo later in 1844 with the map and report he had obtained from Douglas.

With much of the Far West allocated as American Indian territory by treaty, Smith and the Church leadership were limited in their options for potential places to settle that would provide them with the sufficient buffer between the Gentiles that had forced their exodus. As President Tyler had noted the previous year, the Oregon Territory was rapidly filling up, and Texas was on the front line of the impending Mexican-American War.[29] The Great Basin offered a large area of land that the Mormons could potentially inhabit without interference from outside influences; the land described by Frémont seemed ideal for this purpose, as it was, in Wallace Stegner’s words, “the land nobody wanted,” a country “secluded from the world, a wilderness that would be overlooked and bypassed by emigrant trains moving to Oregon and California.”[30] Church documents reveal that as Joseph Smith fled Nauvoo in June 1844, he declared to colleagues, “Be ready to start for the Great Basin in the Rocky Mountains.”[31]

Over the course of the next three years, Brigham Young, Smith’s successor as prophet and Church president, along with other Church leaders, consulted the recently published exploration journals and maps in their search for a place where they could escape persecution once and for all. Church-published newspapers Nauvoo Neighbor and Millennial Star both reprinted extensive excerpts of Frémont’s descriptions of the Great Basin in 1845 and 1846, respectively. In an entry dated December 20, 1845, Heber C. Kimball—a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles—noted in his journal that several “members listened to Franklin D. Richards read in the Temple from Frémont’s journal concerning Frémont’s trip to California.” Nine days later, Kimball recorded that excerpts from Frémont’s narrative were again read to a governing body of the Church, and after that, Brigham Young “spent near an hour reading Capt Fremont’s Narrative.” In his entry for the last day of 1845, Kimball told of a time that he and Young spent examining “maps with reference to selecting a location for the Saints west of the Rocky Mountains and reading the various works which have been written by travelers.”[32]

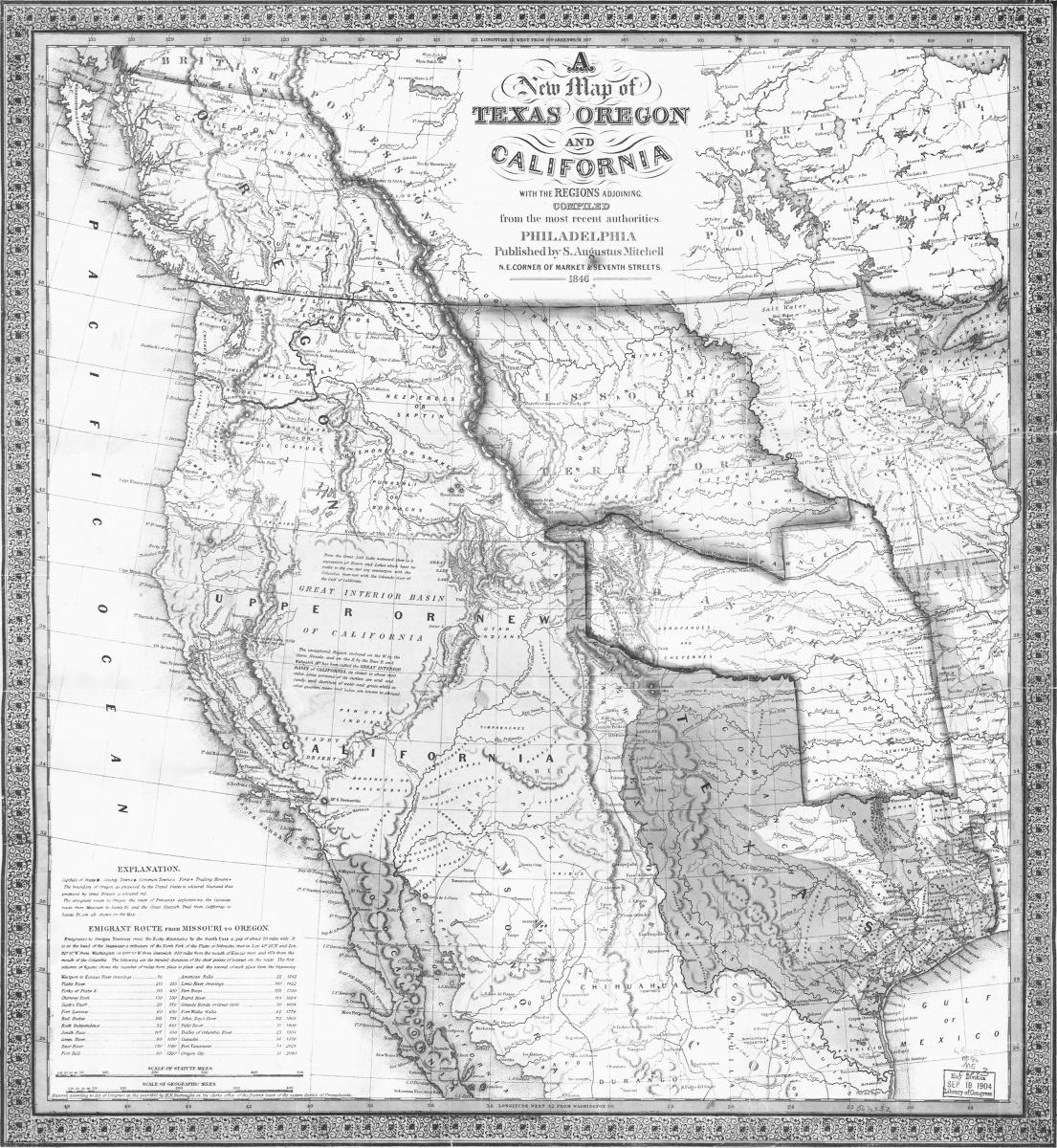

Surely one of those maps was S. Augustus Mitchell’s “A New Map of Texas, Oregon, and California” (see figure 9). Published by the Philadelphia mapmaker in 1846, it was the most recent cartographic representation of the region that Brigham Young could acquire as he and his colleagues made final plans for removing their followers from persecution in Illinois. On February 18, 1847, Young wrote to a contact in Saint Louis, instructing him to bring “one half dozen of Mitchell’s new map of Texas, Oregon, and California and the regions adjoining, or his accompaniment to the same for 1846, or rather the latest edition and best map of all the Indian countries in North America; the pocket maps are the best for our use. If there is anything later or better than Mitchell’s, I want the best.”[33] Two legends occupy the blank space labeled “Upper or New California.” One explains that “the unexplored Region enclosed on the W. by the Sierra Nevada and on the E. by the Bear R. and Washatch Mts. has been called the Great Interior Basin of California, its circuit is about 1800 miles, some portions of its surface are arid and sandy, and destitute of water and grass, while in other quarters, rivers and lakes are known to abound.” The other makes plain that there is no navigable water route to the Pacific: “From the Great Salt Lake westward, there is a succession of Rivers and Lakes which have no outlet to the sea, nor any connection with the Columbia river, nor with the Colorado river of the Gulf of California” (see map). Claiming to be “compiled from the most recent authorities,” including Frémont’s Report, this map is mentioned in more than one Mormon diary from the exodus and was another in the long line of maps influential on both the public mind and the work of other cartographers.

Figure 9. Augustus Mitchell, “A New Map of Texas, Oregon, and California,” 1846. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Figure 9. Augustus Mitchell, “A New Map of Texas, Oregon, and California,” 1846. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

The Church leadership’s plans for emigrating west came to the attention of President James K. Polk by the end of January 1846, but it was not until the United States had declared war against Mexico in May of that year that the Church members’ plight caught the attention of those highest up in the halls of political power in the nation’s capitol. In order to manage the Mormons’ westering impulse—fueled as it was by strong feelings of persecution and redemption—so that they would not inadvertently complicate the national designs on California and geopolitical war agenda, the federal government decided to intervene. As historian Dale Morgan argues, “It was expedient to do something generous for the Mormons. War made it desirable. War also made it possible.” As noted in Polk’s diary, Polk’s plan was “to receive into service as volunteers a few hundred of the Mormons who are now on their way to California, with a view to conciliate them, attach them to our country, and prevent them from taking part against us.” From July 1846 to July 1847, some 526 Church members served in the Mormon Battalion, the only religiously based unit in United States military history, and marched from Council Bluffs, Iowa, opening a nearly two thousand-mile wagon road to San Diego, California.[34] Appearing two years after the 1847 Mormon exodus, the first constitution of the State of Deseret would provide a new imaginary map of the American West, one envisioned by a contemporary religious worldview in the service of national manifest destiny that led to the establishment of the stake of Zion, the settlement of the Great Basin, the creation of Utah Territory, and eventually the state of Utah.[35]

Notes

This is a revised version of a lecture given by Douglas Seefeldt to the Brigham Young University Religious Education faculty at Omaha, Nebraska, on July 17, 2012. The author thanks former graduate student Brent M. Rogers, historian for the Joseph Smith Papers Project, for his research assistance.

[1] Loren Baritz, “The Idea of the West,” American Historical Review 66, no. 3 (April 1961): 618–19.

[2] Baritz, “The Idea of the West,” 637.

[3] Baritz, “The Idea of the West,” 638, 640.

[4] John Rennie Short, Representing the Republic: Mapping the United States, 1600–1900 (London: Reaktion Books, 2001), 11–12.

[5] Aaron Arrowsmith and Samuel Lewis, A New and Elegant General Atlas, Comprising All the New Discoveries, to the Present Time. Containing Sixty-Three Maps, Drawn by Arrowsmith and Lewis (Philadelphia: John Conrad and Co., 1804), maps of Louisiana and United States.

[6] Carl I. Wheat, Mapping the Transmississippi West, 1540–1861 (San Francisco: Institute of Historical Cartography, 1958), 2:5–8.

[7] John Logan Allen, Passage through the Garden: Lewis and Clark and the Image of the American Northwest (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1975), 231, 250–51.

[8] Wheat, Mapping the Transmississippi West, 2:43–44. This manuscript map is held by the Boston Athenaeum.

[9] Wheat, Mapping the Transmississippi West, 2:49–56.

[10] Allen, Passage through the Garden, 375–76.

[11] Paul Allen, ed., History of the Expedition under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark, to the Sources of the Missouri, Thence across the Rocky Mountains and down the River Columbia to the Pacific Ocean (Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep, 1814).

[12] Allen, Passage through the Garden, 382–83. The original copper-plate engravings of Samuel Lewis’s “A Map of Lewis and Clark’s Track” reside with the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia.

[13] Wheat, Mapping the Transmississippi West, 2:58–59.

[14] Gordon S. Wood, Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 546.

[15] Baritz, “The Idea of the West,” 638.

[16] Thomas Jefferson, “First Inaugural Address,” in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2006), 33:148–52.

[17] Wheat, Mapping the Transmississippi West, 2:157–59.

[18] Michael S. Durham, Desert between the Mountains: Mormons, Miners, Padres, Mountain Men, and the Opening of the Great Basin, 1772–1869 (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1997), 18–19.

[19] Wheat, Mapping the Transmississippi West, 2:167–70.

[20] David Roberts, A Newer World: Kit Carson, John C. Fremont, and the Claiming of the American West (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000), 138.

[21] Donald Jackson and Mary Lee Spence, eds., The Expeditions of John Charles Frémont, 3 vols.; Map portfolio (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1970–84); map portfolio, 12, referenced in James P. Ronda, Beyond Lewis and Clark: The Army Explores the West (Tacoma, WA: Washington State Historical Society, 2003), 43.

[22] Ronda, Beyond Lewis and Clark, 41.

[23] Dale L. Morgan, The Great Salt Lake (1947; repr., Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico, reprint edition, 1973), 146.

[24] John Tyler, “Third Annual Message,” The American Presidency Project, http://

[25] Tyler, “Third Annual Message,” http://

[26] Morgan, The Great Salt Lake, 176.

[27] J. C. Frémont, A Report on an Exploration of the Country Lying between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains, on the Line of the Kansas and Great Platte Rivers, S. Doc. No. 243 (1843).

[28] Orson Hyde to Joseph Smith, Washington, DC, April 26, 1844, MS 155, box 3, folder 2, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Smith’s journal indicates that he received Hyde’s letter on May 13, 1844, but does not indicate receiving the package from Douglas.

[29] Durham, Desert between the Mountains, 120–21.

[30] Wallace Stegner, Mormon Country (New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1942), 33.

[31] Joseph Smith, in History of the Church, 6:548, quoted in Leonard Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830–1900 (1958; repr., Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1966), 40–41.

[32] Heber C. Kimball, journal, November 1845– January 1846, MS 3469, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[33] Wheat, Mapping the Transmississippi West, 3:31, 34–35.

[34] Morgan, The Great Salt Lake, 180–81.

[35] Constitution of the State of Deseret, with the Journal of the Convention Which Formed It, and the Proceedings of the Legislature Consequent Thereon, House Misc. Doc. No. 18 (1850). Written between July 1 and July 18, 1849, and published in Kanesville, Iowa, that September by Orson Hyde.