Alonzo L. Gaskill (alonzo_gaskill@byu.edu) was an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this was published.

Even for the most imaginative among us, life seldom turns out as planned. It seems fair to say that BYU professor Spencer Palmer’s life went in directions he never anticipated in his youth. Some might say he lived a “charmed” existence, though “blessed” or even “divinely directed” seems a more fitting description. An awareness of Palmer’s life and legacy leaves you with a strong impression that God closed certain doors and opened others to ensure that this preacher of the gospel was where the Lord needed him to be during an important chapter in the unfolding of the Latter-day kingdom.

Born in Eden, Arizona, on October 4, 1927, Spencer John Palmer was the fifth of eight children (two brothers came from a second marriage). They weren’t blessed with monetary wealth, but they were happy and industrious. As Spencer described it, “it was a clean kind of poverty.”[1] The Palmers worked hard and were always grateful for what little they had. Nevertheless, the impoverishment of his youth developed within him deep feelings about suffering and sacrifice—and a profound sense of gratitude for the smallest of mortal blessings. Throughout his life, when called upon by Church leaders to serve, Spencer was able to do so with a willing heart. He had learned in his childhood that service was a joy, and to him, no sacrifice was too great for the kingdom!

In the work-a-day world of his youth, Spencer had not intended on becoming a scholar. Indeed, he once noted, “Until my mission I doubt I’d ever finished [reading] a single book.” However, during his mission, and under the tutelage of mission president Oscar W. McConkie, this young Arizona cotton farmer blossomed into a voracious reader and student of the gospel. From that time forward, Spencer said, “I had a book in my hand every available moment.”[2] In his postmission life he read a great deal and became a rather prolific writer, authoring more than a dozen books and numerous articles in his field.

After completing his bachelor’s degree in fine arts at BYU, Spencer was drafted into the US Army. Following boot camp, he applied to become an LDS chaplain, and was eventually assigned to South Korea. Upon his arrival, he was shocked by the rampant poverty. He described the land as “a forlorn and dejected county. The hills and the streams and the valleys were literally covered with impoverished shacks and homes, some made out of the flimsiest materials—pasteboard boxes for walls, pounded-out beer cans for roofs. Mere hovels, foul-smelling. The children were undernourished. Those in the refugee areas were wretched-looking, cold, and without shoes. It was pitiful. These were shocking conditions for me.”[3]

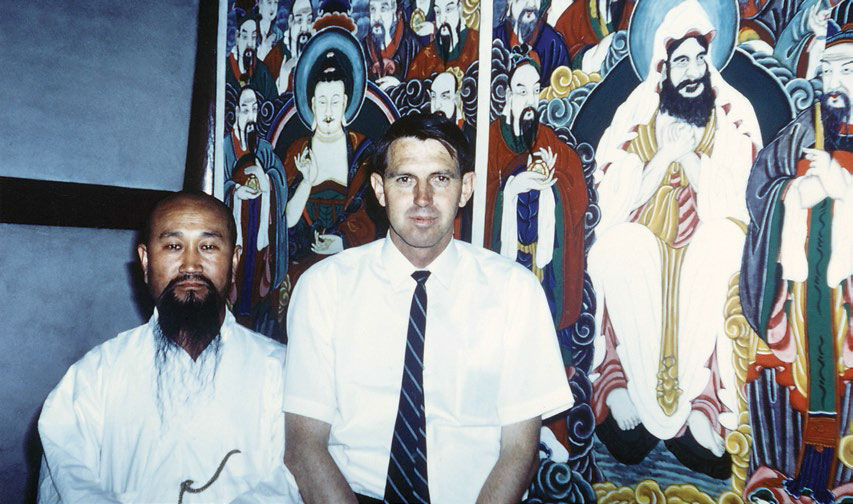

While the deplorable conditions may in many ways have reminded him of his youth, he was also mesmerized by the culture, language, and religions of that land— which did not in any way remind him of his early life in the Mormon pioneer community of Thatcher, Arizona! Poverty aside, Spencer quickly found himself drawn to the people, filled with compassion for their postwar plight, and intrigued by their culture and religious beliefs. He noted that he began to feel an “instinctive compassion for the Koreans,”[4] and he developed an ability to see Mormonism, for the first time in his life, through the lenses of those not of the Church. This had a profound influence on his life, education, and career. Little did Spencer realize that his short stint as a US army chaplain would change the course of his life and, in many ways, open new avenues for the Church on at least two continents.

One of Spencer’s happiest memories of his chaplaincy was, again, one of those “unexpected bends in the road.” Lieutenant Palmer had been assigned to a POW camp on Koje Island. Shortly after his arrival, however, it was determined that the camp was no longer needed. Therefore, the soldiers were instructed to dismantle it. The materials were not worth shipping back to the States, so Spencer— along with others—was assigned the responsibility of distributing construction materials among the locals to be used for humanitarian purposes. Making use of these materials, Chaplain Palmer and a handful of American GIs constructed orphanages and schools and even a nursing home for the elderly. In some ways this actually helped Spencer to deal with the distress he felt over the postwar plight of the people of that war-stricken nation.

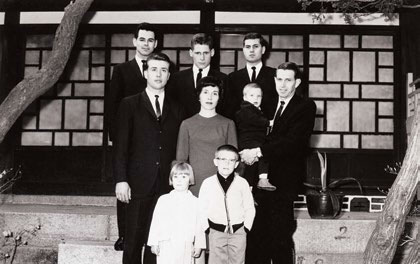

After completing his military service, Spencer intended to pursue a career in radio broadcasting. However, that quickly changed when, in September of 1954, he had the opportunity to spend several hours in the company of Elder Harold B. Lee of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, who was visiting Korea on a Church assignment. After talking “long into the night,” Elder Lee said to young Lieutenant Palmer: “I can see that we have a great future in this part of the world. Our problem is that we don’t have people prepared to undertake this work here. I want you to stay close to these Korean people and to the people of Asia. They need us, and they need you.”[5] Once again, things seemed to go in a different direction than Spencer had planned. He changed course in his education and his career, enrolling at the University of California in Berkeley, where he earned an MA in Asian studies (1959) and a PhD in history (1964). Upon graduation he was employed at BYU as an assistant professor of Korean studies and Oriental religions. However, shortly after beginning his professorial career, and much to his surprise, he received a call from the First Presidency to serve as mission president in South Korea.

In the three years (1965–68) in which he presided over the work in that developing nation, President Palmer oversaw surprising growth in the Korean Church. Membership increased by 31 percent. The Church organization expanded from one district with seven branches to two districts with thirteen branches and three dependent groups. Instead of calling young American missionaries to preside over congregations, President Palmer felt impressed to place Korean priesthood leaders over each of the branches. This greatly strengthened the Church membership. Under President Palmer’s predecessor, Gail Carr, work on translating the Book of Mormon into Korean began. Ultimately, it was finally completed and published while Spencer was serving as mission president—a milestone in Korean Church history. During Palmer’s presidency the first Latter-day Saint chapel in Korea was completed and dedicated, and the site for what would become the Seoul Temple was purchased. President Palmer organized the Korean Mission Genealogical Committee—thereby beginning the work of preparing Korean names for submission to the temple. Amazingly, he also accomplished the unthinkable: securing regular spots for the Church on Korean TV and radio. The image of the Church was greatly improved because of this fortuitous venture. It seemed evident that President Palmer was being inspired.

Spencer realized the need to make Mormonism meaningful to the people of Korea, who did not see the world through Western lenses. He had a unique ability to translate the faith into meaningful paradigms that made it attractive to many Korean nationals. Indeed, one of his colleagues, Dong Sull Choi, noted that Spencer Palmer “Koreanized” the Church, making it intelligible and palatable to the people of that land.[6] Someone once referred to Spencer as “Mister Korea.” He responded that he would rather be known as “Mister International.”[7] He had a profound respect for the people, language, culture, and religions of Korea, but he saw his ministry as being to the whole world, not just to the people of East Asia. Spencer traveled extensively and could not get enough of learning about and befriending others. He quickly won the respect and amity of those he met. As an example, a 1986 This People magazine article shared the following experience from his travels:

A case in point was Spencer’s visit to the Juju Man, or medicine man, who lived and operated out of a rain forest in Ghana. During a visit to a LDS branch in the area, he heard about the reputed power of the Juju Man. “They told me, for example, that the Juju Man may spread magic on a chair. When someone makes contact with the chair, that person may meet with an accident or untimely death.” Palmer wanted to meet the Juju Man. After some difficulty, he finally got one of the villagers to take him near the Juju Man’s hut. “The Juju Man gave me a mean stare and then did a violent dance to try to scare me,” Palmer says. “But after a while he saw that I was really enjoying it.” The Juju Man was soon disarmed. When Palmer left the hut, he had made another friend.[8]

Spencer’s dogged insistence on meeting this medicine man is rather remarkable, owing to his upbringing. His small hometown of Thatcher, Arizona, was hardly cosmopolitan. From Spencer’s description, it appears to have been void of what one might call “innovating” or “ecumenical” influences. In the later years of his life, speaking of his upbringing in a small community, Spencer recalled: “We had one nationality, one race, one culture, [and] one language. We were isolated from the world, and proud of it.”[9] That may have been the way he was reared, but it is the antithesis of how he viewed the world in his adulthood! One of his acquaintances called him “a cultural shock absorber . . . for whom there’s no such thing as foreign turf.”[10] He truly was “Mister International”—and could be happy no other way!

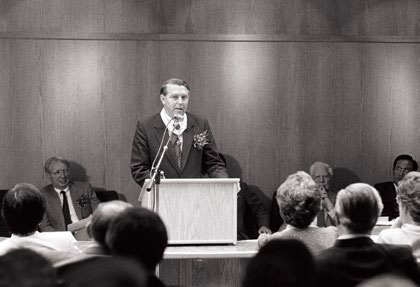

Upon his return to the United States, Palmer resumed his career as a professor of world religions at BYU. His focus on that particular discipline was born of his conviction that the Church was increasingly becoming an international faith. How can it possibly teach the world, he thought, if its members and missionaries don’t understand the people of the world and their religions? [11] One of his biographers pointed out, “Spencer Palmer was a man ahead of his time—maybe too far ahead, some might have said. . . . The young professor had come to BYU to teach world religions, which meant ‘heathen religions’ to some of his faculty peers. The propriety of teaching such a course at the Church-sponsored university was questioned; some wondered out loud if this might be an irrelevant or, worse, a testimony-weakening activity.”[12] Spencer gave no heed to the naysayers. Rather, he devoted himself to the work—taking a class which was not wildly popular at the time, and making it one of the staple offerings of the College of Religion. While serving as president of BYU, Jeffrey R. Holland noted of Professor Palmer, “Spence is as close to a true ‘mover and shaker’ as I know.”[13] Well, he certainly “shook” a few of his colleagues with his rather open-minded view of the world in a day and age when provincialism was the norm. But he quickly gained the trust and hearts of those who knew him—and all that he did attested to his testimony of and his faithfulness to the kingdom.

The textbook used for nearly a quarter of a century in BYU’s world religions course (and in the Church Educational System’s Institute of Religion classrooms) was Palmer’s brainchild. It exemplified his methodology, with phrases like “Look for similarities! Build bridges!” Professor Palmer rejected the “negative approach” to studying world religions which some Latter-day Saint teachers seemed to embrace. He came to realize that there was truth in every religion—and that the gospel could be found to one degree or another in every faith tradition. He looked for truth in all of them, and found it! He was not shy about praising that which was good, or that which he found beautiful, in another religion. Indeed, Roger Keller, who taught world religions alongside Professor Palmer for many years, noted that Spencer “had an appreciation for the breadth of God’s work” and could see “God’s hand working” in the lives of individuals, even “beyond the parameters of the LDS community.”[14]

Spencer was a popular teacher. He could captivate students with what has been described as his “dramatic, Spencer Tracy–like voice”[15] but also with his ability to change his students’ paradigms about the world and other people, cultures, and races. Many entered his classroom feeling that they pretty much “knew how things were” and left with a broader view about the gospel and the world than they ever imagined possible. In this regard, he was a master teacher.

In addition to coauthoring BYU’s world religions textbook, Dr. Palmer wrote many other books on the faith and cultures of the world—with a particular emphasis on all things Korean. His work in the field of Korean studies became so influential that in July of 1985 the Korean government bestowed upon him their Order of Cultural Merit and presented him with a citation from the president of South Korea honoring him for his contributions to Korean studies. He researched so that he could understand, and he wrote so that others would understand. He firmly believed that it was imperative that we understand others before we can empower them to understand us. Spencer’s wife, Shirley, noted of Spencer thus: “His main goal was to friendship people from around the world—that they would come to the university and see its good work, and see the ‘light on the hill.’ Spencer felt that, in so doing, visitors would be impressed by the Church and Latter-day Saint Christianity.”[16]

In 1993, Palmer was asked by the Chinese government to serve as a comparative religion professor for ethnic minority groups in Beijing. Midway through the semester, China’s State Committee on Minorities requested that Palmer translate his book, Religions of the World: A Latter-day Saint View into Chinese, for future use at the university. Professor Palmer, with the aid of several of his Chinese colleagues, worked feverishly to complete the project before the end of the semester.

Brother Palmer held many callings, and served in many capacities, within the Church. In his youth he served as a full-time missionary in California—something he had anticipated from his childhood. In 1969 he was asked to play one of the key roles in a film-based version of the temple endowment—a film that was shown daily in most Latter-day Saint temples for a decade and a half. Though Spencer had acted quite a bit in his youth, the concept of a film version of the endowment was at the time unimaginable to most members of the Church. The idea that he would be asked to be one of the actors was a blessing to him. Brother Palmer also served as a bishop, twice as a counselor in a stake presidency, as a regional representative of the Twelve in Southeast Asia, and as the president of the Seoul Korea Temple. Spencer was called upon by the Brethren to do some remarkable and high-profile things in the Church. He loved the Lord and loved to serve. He didn’t flaunt his accomplishments, nor did he see himself as being above those whom he served. No wonder his obituary stated he could “walk with kings but never lose the common touch.”[17]

Spencer Palmer spent the better part of thirty-five years educating the Latter-day Saints about the culture, beliefs, and beauty of the peoples and nations of this great planet. And, true to his initial commission from Elder Harold B. Lee, Spencer never severed his connections to the people of Korea. He spent more than three decades building bridges and gaining friends in East Asia and across the globe. His wife referred to him as “a preacher of the gospel to the world.”[18] Truly, he was! Spencer opened the eyes of thousands of students to the good in other people and their traditions—and he introduced countless non–Latter-day Saints to the faith for which he had devoted his life and boundless energy.

Notes

[1] Dong Sull Choi, A History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Korea, 1950–1985 (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 1990), 150.

[2] Denny Roy, “Man of the World,” This People, May 1986, 48; see also Choi, History of the Church, 150.

[3] See Roy, “Man of the World,” 48.

[4] Roy, “Man of the World,” 49.

[5] Roy, “Man of the World,” 49. See also Choi, History of the Church, 152.

[6] See Choi, History of the Church, 154.

[7] Roy, “Man of the World,” 50.

[8] Roy, “Man of the World,” 50.

[9] Roy, “Man of the World,” 48.

[10] Robert L. Millet, interview with the author, February 7, 2013.

[11] Shirley Palmer, interview with the author, January 10, 2013.

[12] Roy, “Man of the World,” 47.

[13] Roy, “Man of the World,” 53.

[14] Roger Keller, interview with the author, January 9, 2013.

[15] Roy, “Man of the World,” 48.

[16] Palmer, interview.

[17] Spencer Palmer obituary, Deseret News, November 30, 2000.

[18] Palmer, interview.