Brent R. Nordgren (brent_nordgren@byu.edu) was managing editor of the BYU Religious Education Review magazine when this was published.

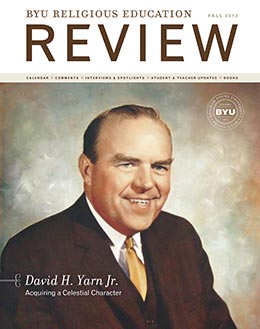

One of my first memories of my neighbor David H. Yarn Jr. is when I observed him regularly walking to his mailbox wearing a tie and a jacket. This scene may not appear so peculiar except for the fact that he was retired and spent much of his time at home reading and writing. I wondered why anyone would dress up just to go to the mailbox.

Before meeting him I knew nothing about David Yarn. I didn’t know of his achievements or his career at BYU, but for the next twenty years I was privileged to become his friend and learn about him and from him by spending many hours with him and his wife. As our friendship developed, I grew to admire and love him.

Those who knew him agree that David had a cheery temperament. His daughter Rebecca Yarn Allen said, “He had a great sense of humor and an infectious laugh.”[1] He was almost always smiling or laughing a lot, and he seemed extraordinarily happy. He was fun to be around and loved everyone. In fact, the only times I remember him not brimming with delight were when he was emphasizing something of an important or solemn nature. He was also profoundly spiritual and extremely articulate on a vast array of significant topics.

To fully capture the essence of David Yarn, one must know that he was born and raised in the South. Chauncey Riddle, a longtime friend and colleague, said of David, “One of his unique and pronounced characteristics was his warm and hospitable Southern manners. He was always polite, deferential, soft-spoken, generous, and his speech was graced by his delightful Southern accent.”[2]

After my early encounters with David, I realized that he was the personification of a true Southern gentleman who had enough class and style to always dress up—even if it was to simply go to his mailbox. His daughter said, “It wasn’t because he was vain. He liked to look appropriate and presentable because he was a gentleman.”[3]

The Early Years

David Homer Yarn Jr. was born July 7, 1920, in Atlanta, Georgia, to D. Homer and Bessie Haskell Herring Yarn.[4] As a youth, David pursued several passions. These weren’t just casual pursuits for young David. Throughout his life, he poured his heart and soul into most everything he did. For example, he was involved in several sports and lettered in those that offered letters and helped teams win championships. Similarly, he excelled in oratory, glee club, and his work on the school newspaper and the school yearbook. While in high school, he also joined the ROTC, where he was commissioned second lieutenant, then captain, and finally major. When he graduated from high school, he was given a number of awards and received the student government medal.

When David went on to college, his popularity continued, as he was a member of at least four fraternities—elected president of two of them—and was on the Georgia Tech freshman football squad.[5] But life as he knew it was put on hold when he was called to serve in the Western States Mission. He completed his mission in February 1943.

Shaping the Future

With the end of World War II in sight, David left home to attend BYU. On March 24, 1945, the day after he arrived in Provo, he met Dr. Sidney B. Sperry. David had great respect for Dr. Sperry. He recalled, “I met Dr. Sperry and had that wonderful relationship with him. Brother Sperry was the big wheel. I mean he was really the big wheel. He was a very humble man; he was trained in many fields at the University of Chicago.” David remembered their first meeting: “We just hit it off. . . . It just seemed to be a natural relationship. He became a great friend.” Within a week Dr. Sperry employed David as a student assistant. This friendship continued through Dr. Sperry’s life. David spoke at the funeral of Dr. Sperry and later the funeral of Dr. Sperry’s wife, Eva. [6]

David’s mission and some of his early experiences as a BYU student provided insights that would influence his entire life. After he retired, he wrote to his granddaughter, Rachel Yarn Allen, to respond to her question, “What factors influenced you to become a teacher?” He explained how his mission and the satisfaction he found in sharing ideas and learning played a part. He also credited the enjoyment he had in the academic association with fellow students and with Dr. Sperry. David was likewise inspired by the experiences he had when he and his roommate, B. West Belnap, would regularly conduct Sunday night firesides in their dormitory living room.[7]

In September of 1945, David met the woman he would marry, Marilyn Stevenson, but didn’t go on a date with her until December. He and his friend B. West Belnap went on a double date to West’s missionary reunion. West served his mission in the Southern States Mission, where David grew up. Each couple eventually married their date. David graduated in June 1946, and he and Marilyn were married that August.

Up to the Challenge

Before leaving to attend graduate school at Columbia University, David taught three theology classes at BYU. In February 1949, he was awarded his MA in philosophy from Columbia University. After returning to Provo in August 1950, he was hired to teach at “the BYU,” as he liked to call it. The first faculty meeting he attended was held at the Karl G. Maeser Building, and he remembers that there were just 123 faculty members campus-wide who attended. In that meeting, the President of the Church, George Albert Smith, introduced the new president of BYU, Ernest L. Wilkinson.[8]

As a new assistant professor of philosophy and theology in the Division of Religion, David began teaching in the fall of 1950. Within a year, he became the chairman of the Department of Theology and Religious Philosophy. Although the department name was changed during his tenure, he continued to be the chair until 1957, when he took a sabbatical leave to finish his EdD in philosophy and education at Columbia University.

Upon his return to BYU in August 1958, David was advanced to associate professor and made the director of the Division of Religion. As the director, he felt that the division was not given the respect it deserved. It was regarded as subpar, and many faculty members across campus didn’t think much of it. David believed the appointment of a dean would establish the Division of Religion on an equal footing with the rest of the university. He wrote to President Wilkinson and recommended that a college be established and that a dean be appointed. His recommendations were approved. Though he certainly didn’t seek the position, Yarn was advanced to full professor and became the first dean of the new College of Religious Instruction on January 14, 1959.[9]

Growth and Direction

During 1959, a review of the religion curriculum was the subject of extensive discussions in college faculty meetings. During those deliberations, Dean Yarn reminded the faculty that “one of the purposes of revising the curriculum was to make sure that the courses offered . . . would be of fundamental value to the student.” He pointed out that because students take a limited number of courses in religion, they should be encouraged to study the basics of the gospel.[10]

There were two sides to the debate. Those who favored a rudimentary theology course claimed that it would provide a complete coverage of gospel principles. Those favoring the Book of Mormon course emphasized that this book had been given as the prime instrument for converting people to Christ in this day.[11]

Dean Yarn personally favored the basic theology course but sought to know the desires of the Lord. He explained:

I prayed and prayed and prayed. Finally, one night I knelt behind the bed and just as clearly as anything I ever experienced, I heard the words, “The Book of Mormon is the course that should be taught.” At that point I knew what should be taught and that was not what I had chosen, because I leaned the other way. And so it was just two or three days later, President Wilkinson called and said, “President McKay said that they, in the Board of Trustees meeting yesterday, decided that the Book of Mormon should be the course that should be taught.” I was so grateful that I had been given my own personal witness before President Wilkinson made that call to me because I knew that the Brethren had also been inspired that the Book of Mormon was to be the course.[12]

Richard O. Cowan, who was hired by Dean Yarn in 1961 and continues to teach at BYU as of this writing (2012), commented on how Dean Yarn handled the situation: “Brother Yarn’s kindly and almost fatherly leadership helped heal this division and enabled Religious Instruction to embrace its key mission to strengthen the faith and testimonies of BYU students.”[13]

In 1962, due to illness, Dean Yarn was given an honorable release as the dean.

Philosophy

When David first came to BYU as a student, he wanted to pursue philosophy. He earned degrees in philosophy. Within the Division of Religion, he served as the chair of the Department of Theology and Philosophy. When Philosophy was separated from Religious Instruction, David went too. Philosophy became its own department within the College of Humanities where David was the acting department chair in 1979. He certainly left his mark in philosophy, as he did in religion. To this day, the Philosophy Department holds an annual David H. Yarn writing contest and maintains a David H. Yarn fund to further the interest of the department.

Service

In a devotional address given at BYU in August 1996, David Yarn stated, “As stewards of all the circumstances and things entrusted to us, it is our responsibility to so administer, manage, and use these things that we bless the lives of all with whom we associate. The Lord said, ‘He that is greatest among you shall be your servant’ (Matthew 23:11).” [14] David was the embodiment of this statement. He served people in numerous callings and assignments where many of those he served considered him the greatest among them.

In December 1967, Elder Marion G. Romney asked David to write a biography of President J. Reuben Clark Jr. David says he “naively” accepted, having no idea that this assignment would eventually take him twenty years to complete. During those years, David reported to Elder Romney and eventually to the First Presidency. They often had dinners at one place or another, and David would report on the progress of the work.[15]

David often visited Elder Romney in his office, where Elder Romney had a picture of Brother Clark on his shelf. On many visits Elder Romney would say, “Every time I come into my office and look at that picture, I hear him say, ‘Boy, when are you going to get this project finished?!’” After David had worked on the project several years, he would respond to Elder Romney, “At the rate we are going I bet it’s going to take twenty years.” That prediction proved to be accurate. David’s work produced six published books and several articles, papers, and presentations that have provided extraordinary insight into the life and teachings of President Clark.[16]

Under the direction of the Twelve and often the First Presidency, David was asked to write and prepare numerous lessons and teachers’ supplements for the official Church Melchizedek Priesthood and Sunday School manuals. These assignments by the Brethren were in addition to his numerous Church callings. Some of his callings included branch president, counselor in bishoprics, member of the Young Men’s Mutual Improvement Association and Sunday School General Boards of the Church, stake high councilor, counselor in a stake presidency, bishop, stake president, sealing officiator, and temple president of the Atlanta Georgia Temple.

David was an excellent orator and asked to speak on behalf of the Church in weekly addresses on KSL radio. He was also often invited to speak at stakes, wards, firesides, and graduations. At BYU he delivered a forum address and two devotional addresses. In 1966, he received the Karl G. Maeser Award for Teaching Excellence.

A Teaching Legacy

Another of David’s friends and neighbors, Brad Wilcox, a professor of education at BYU, explained, “David was a scholar. He read deeply and broadly. He wrote with power and passion, and he taught with effectiveness. There are countless people all over this Church who can trace not only their testimonies, but their love of learning, their love of gospel scholarship right back to David Yarn.”[17]

At David Yarn’s funeral, Elder Jeffrey R. Holland paid tribute to him:

David Yarn was one of those remarkable men who truly was as good as he seemed to be. Everything about David Yarn had style. . . . I have been sitting at David Yarn’s feet, admiring him, and seeking his counsel, and listening to his lectures for forty-nine years. I first met him as a brand-new student at BYU in the fall of 1963, when I enrolled in a philosophy class from David, and that began the adoration that I have had for him now for half a century, and it will go on forever. I then took another class from him as a graduate student, a class in religious, ethical, moral problems—it was a terrific class. I went away and came back as a faculty colleague. I loved and admired the tradition that he had established as the first dean of a faculty that I was later privileged to serve as dean, and how often I sought his counsel and how often I went to him for advice. I went off to be Commissioner of Education for a while and still talked to and sought out David’s advice about a host of things, particularly religious education.

I remember as I finished my undergraduate work . . . I had to decide what I was going to be when I got big, and didn’t really know who knew my heart any better than David Yarn. I can still picture the afternoon. I can still see his face, as we sat and I talked about what my dreams might be in the world of education, and was there any chance I could succeed in a graduate program somewhere? I still remember the conversation to this day, and his love, and his attention, and his thoughtfulness, his gentlemanly quality always, always uppermost, and the encouragement that he gave me that he thought better of me than I thought of myself at that point. I will always be indebted to him. I put David in such a sweet and special place. . . . I’ve wanted not to disappoint him, and I hope that I haven’t or that I won’t.[18]

Consummate Disciple of Christ

Elder Holland also described David as a “consummate disciple of Christ. . . . His love of the Lord was so conspicuous in his life and in his service.” Speaking as a representative of the First Presidency and the Twelve, Elder Holland said how he and Elder Dallin H. Oaks “both loved David as a friend and faculty member, and all of the Brethren have loved him for all his years of Church service.”[19]

In a letter, the First Presidency added, “Brother Yarn’s life was a model of diligence and of hard work. He was indeed an extraordinary man and an exceptional educator who achieved great success in his many years at Brigham Young University. His example of devotion as a husband, father, grandfather, great-grandfather, and stalwart servant of the Lord influenced the lives of loved ones and all with whom he came in contact.”[20]

The Purpose of Life

David was a prolific journal writer. Once I asked him how many pages he had written. His answer was in the tens of thousands. I suggested to him that his journals would be appreciated by his descendants someday, but he seemed doubtful. Then I very seriously suggested to him, “Someday, whether it be your children, grandchildren, or generations yet unborn, people will undoubtedly benefit from the journals you kept.” To this he said, “I hope you are right.” Fortunately, he donated the bulk of his writings to the library at “the BYU.”

David Yarn accomplished so much during his lifetime, and his journals are filled with a who’s who of his frequent interactions and encounters with prophets, apostles, and many other prominent people. But he remained a very humble man. He always made everyone feel that they were his equal or even his superior, despite all that he accomplished and all those with whom he associated. He would undoubtedly be embarrassed by my bringing attention to his accomplishments. At a retirement dinner in his honor, he advised, “May we always be humbly grateful for all of the learning that has been made available to the world in our time, along with its innumerable benefits. May our perception always be such that it enriches us and enlarges us and does not entrap us. May our influence upon our students, be it great or small, contribute not to the inflation of their egos, but to the exaltation of their souls. May our vision of the human always be seen in the context of the divine.”[21]

What a legacy David Yarn left—not only through his written word but through his posterity and his exemplary life. At a BYU devotional he taught, “Our first endeavor in our preparation for eternal life is to seek to develop and acquire celestial character.”[22] I believe that throughout his life David Yarn indeed sought, developed, and acquired celestial character.

Notes

[1] Rebecca Yarn Allen, “Funeral Services: David H. Yarn Jr.,” March 10, 2012.

[2] Chauncey C. Riddle, “Memories of David H. Yarn Jr.,” June 2012.

[3] Allen, “Funeral Services: David H. Yarn Jr.”

[4] David H. Yarn Jr., Vita, Plus (Provo, UT; n.p., 2006), 1.

[5] Several of David H. Yarn Jr.’s early experiences, rewards, and achievements were garnered from his self-published journal, Vita, Plus.

[6] David H. Yarn Jr., interview by Scott C. Esplin and Brent Nordgren, October 8, 2009.

[7] Yarn, Vita, Plus, 32.

[8] Yarn, interview by Esplin and Nordgren.

[9] David H. Yarn Jr., interview by Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, April 22, 2008; Yarn, interview by Esplin and Nordgren; Ernest L. Wilkinson, memorandum of conference with the First Presidency, January 15, 1959.

[10] College of Religious Instruction faculty meeting minutes, May 28, 1959.

[11] College of Religious Instruction faculty meeting minutes, May 28, 1959.

[12] Yarn, interview by Esplin and Nordgren.

[13] Richard O. Cowan, memories of David H. Yarn Jr., June 2012.

[14] David H. Yarn Jr., BYU devotional address, August 6, 1996.

[15] Yarn, interview by Esplin and Nordgren.

[16] Yarn, interview by Esplin and Nordgren.

[17] Brad Wilcox, “Funeral Services: David H. Yarn Jr.,” March 10, 2012.

[18] Elder Jeffrey R. Holland, “Funeral Services: David H. Yarn Jr.,” March 10, 2012.

[19] Holland, “Funeral Services of David H. Yarn Jr.”

[20] First Presidency to the family of Dr. David H. Yarn Jr., March 10, 2012, in possession of the family.

[21] David H. Yarn Jr., “Retirement Dinner Remarks,” September 18, 1985.

[22] David H. Yarn Jr., BYU devotional address, August 6, 1996.