“Appoint among Yourselves a Teacher” (D&C 88:122)

Religious Education and the Training of Gospel Teachers

Scott C. Esplin

Scott C. Esplin (scott_esplin@byu.edu) was an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this was published.

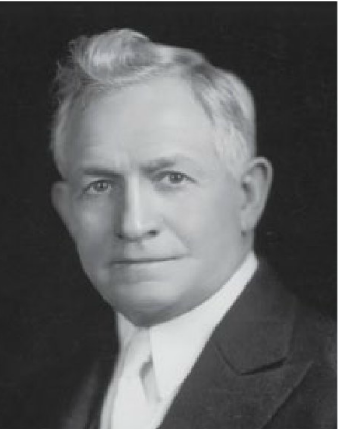

The training of gospel teachers has brightened some of the darkest days in the history of BYU. As the Church was divesting itself of its expansive academy system during the 1920s, replacing it with the current seminary and institute program, Church Commissioner of Education Joseph F. Merrill warned members of the BYU Board of Trustees, “At the Board meeting yesterday it was not definitely stated so, but it seemed to be the minds of most of those present that the BYU as a whole was included in the closing movement.”[1] When questioned about the future of BYU, Church President Heber J. Grant expressed similar concern that “the policy covered all the schools and that eventually BYU would have to be considered as we are now about to consider the individual junior colleges.”[2]

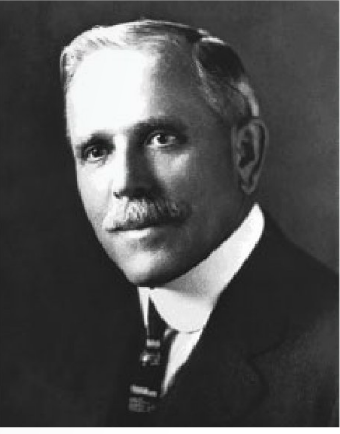

David O. McKay, a former teacher and administrator at the Church’s Weber Academy prior to his call to the apostleship, was gravely troubled by the decision to close schools. Expressing the desire that he not “be considered as not sustaining the First Presidency,” Elder McKay nevertheless cast a lone dissenting vote against the elimination of Church schools in 1929. In particular, Elder McKay’s defense of Church schools focused on their ability to train educators. Arguing for their preservation, Elder McKay favored the “retaining of junior colleges at this time because by their elimination the Church would lose its hold on the training of its teachers.”[3] His argument ultimately saved BYU when Commissioner Merrill declared in 1930, “The General Church Board of Education has announced the policy of withdrawal from the field of secular education, except that the BYU will be continued.” Echoing Elder McKay’s position, Merrill linked the school’s salvation, in part, to the training of religious educators for the growing seminary program. “The key to the seminary system is a university where the teachers may be trained for the work,” Merrill explained. “We employ no teachers who do not meet the requirements of respective state boards for high school teaching. In addition every teacher must receive the equivalent of a teaching major in the field of religious education. This means, of course, that the Church must maintain an institution where this training in the field of religion may be received.”[4] When challenged to explain why BYU was preserved, Merrill further connected the school to the training of gospel teachers. “The Church has established a great seminary system—the greatest one in America,” Merrill responded. “A seminary system without a university to head it would be like a U.S. Navy without Annapolis, without the Naval Academy. A navy must have officers, and officers must be trained. The Naval Academy is therefore an indispensable unit in the Navy. And just so is a university an essential unit in our seminary system. For our seminary teachers must be specially trained for their work. The Brigham Young University is our training school.”[5]

Partnering with Seminaries and Institutes, Religious Education at BYU has worked to fulfill the vision of training gospel teachers that saved the school more than eight decades ago. The current seminary training program has its roots in an era when the Church Educational System was headquartered on campus from 1953 to 1970. During the early years of seminary training, Leland Anderson, Marshall Burton, Robert Christensen, Paul R. Warner, and Jay E. Jensen served as some of the university’s earliest teacher trainers, operating a teaching lab and classroom in the McKay Building, the Fletcher Building, and the Smith Family Living Center before occupying rooms in the current Joseph Smith Building. Coinciding with an era of dramatic growth for Church Education, these men began a program that annually trained hundreds of students in principles of gospel teaching, with as many as thirty each year receiving full-time appointments in the Church school system upon graduation.

For more than forty years, Religious Education at Brigham Young University has offered a class on gospel teaching, known today as Religion 471—Teaching Seminary. Presently, more than two hundred students enroll in the class each year, with as many as twenty-five of them continuing in part-time positions at seminaries across Utah Valley. While only a small number eventually receive full-time employment in the seminary system, administrators view the program as a success. Paul Warner, retired religious educator and longtime director of the seminary teacher training program, describes those who were not hired: “Some were disappointed at the time. However, even those teachers we did not hire would often come back and say it was their most important experience at BYU. Taking the seminary teacher training classes prepared them to be teachers across the Church.”[6]

For those hired in Church education, the relationship between Religious Education and Seminaries and Institutes continues. Some participate in the annual Sidney B. Sperry Symposium, an “outreach to the entire religious community” sponsored jointly by Religious Education and Seminaries and Institutes as a benefit for the local community but also as a midyear “in-service enrichment experience for full-time teachers of religion.”[7] Others return to campus as visiting professors, teaching courses in Religious Education while pursuing graduate degrees at the university. Every two years since 2000, a handful of seminary and institute teachers come to campus to begin study in a master’s degree in religious education, a program “designed to help full-time teachers in the Church Educational System (CES) better serve the Lord . . . by providing them with advanced training and preparation for teaching in the Church Educational System.”[8]

Through these interactions, Religious Education at BYU works hand in hand with Seminaries and Institutes to improve gospel teaching. While the training of religious educators once saved BYU, the program’s reach today extends “far and wide into the Church. It is much bigger than just those who are hired in Church education,” Paul Warner concludes.[9] By improving gospel teaching in the Church, Religious Education helps members access the Lord’s promised blessing, “Teach ye diligently and my grace shall attend you” (D&C 88:78).

Notes

[1] Joseph F. Merrill to Thomas N. Taylor, February 21, 1929, in Ernest L. Wilkinson, Brigham Young University: The First Hundred Years (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1975), 2:87.

[2] General Church Board of Education Minutes, February 20, 1929, in William Peter Miller, Weber College, 1888–1933, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

[3] General Church Board of Education Minutes, February 20, 1929.

[4] Cited in Bruce Emanuel Millikin, “The Junior College in Utah: A Survey” (master’s thesis, Stanford University, 1930), 125–26.

[5] Joseph F. Merrill, “Brigham Young University: Past, Present, and Future,” Deseret News, December 20, 1930, 3.

[6] Interview with Paul R. Warner, July 26, 2012.

[7] Cited in Richard O. Cowan, Teaching the Word: Religious Education at Brigham Young University (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2008), 44, 46.

[8] “Master of Arts in Religious Education: Program Purpose,” http://

[9] Interview with Paul R. Warner, July 26, 2012.