Introduction

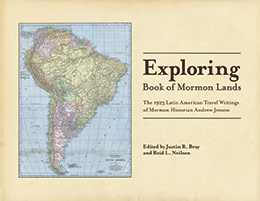

On July 11, 1923, assistant Church historian Andrew Jenson met at the office of the First Presidency in Salt Lake City, Utah, to report on his four-month, twenty-three-thousand-mile expedition throughout Central and South America from January to May of that year. Jenson, the foremost representative of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to visit the countries south of the Mexican border since Apostle Parley P. Pratt in 1851, had eagerly waited for two months to give his glowing assessment of Latin America as a potential missionary field to the Church’s three presiding high priests, Heber J. Grant, Charles W. Penrose, and Anthony W. Ivins.[1]

The journey through Latin America significantly differed from Jenson’s earlier overseas expeditions. Later described as “the most traveled man in the Church,” he had been a lifelong globe-trotter since his emigration from Denmark to Utah as a young boy in 1866.[2] Throughout his life, Jenson visited parts of Asia, Europe, the Middle East, Scandinavia, and the South Pacific, either preaching the gospel as a full-time missionary or compiling historical documentation of the Latter-day Saints as an employee of the Church Historian’s Office. Over the course of his career, Jenson gained a reputation as an ambitious self-starter, and he dedicated most of his life to tirelessly promoting Church history. By 1923, at age seventy-two, Jenson had long contemplated a needed vacation-expedition through Central and South America—regions generally accepted at the time by Latter-day Saints as Book of Mormon lands.[3]

Although lifelong interest in the whereabouts of ancient Nephite and Lamanite ruins propelled Jenson to visit the remote areas of Latin America, he returned with a powerful impression that the latter-day gospel should be spread south, beyond the borders of Mexico. He began his evaluation by providing the First Presidency with the demographics of the nineteen Latin American countries he either visited or passed by along his journey, including Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, British Honduras (Belize), Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Brazil, Venezuela, and the West Indies. Jenson then highlighted the languages spoken and religions practiced, and while Catholicism by far dominated Latin America, Jenson emphasized the “perfect religious liberty” currently granted to the inhabitants of Latin America and how “Latter-day Saint missionaries would be well received.” The peoples of Latin America would, Jenson asserted, “welcome messengers who could declare unto them the true gospel of Jesus Christ.”[4]

After highlighting the evangelistic success in Latin America of the Salvation Army, a Christian evangelical organization known for its charitable contributions around the world, to illustrate the potential for Latter-day Saint missionaries in that same region, Jenson concluded his spirited presentation to President Grant and his counselors with a direct recommendation to spread the gospel into Central and South America. “Knowing, as I do, that the Lord has commanded the Latter-day Saints to preach the gospel to every nation, kindred, tongue, and people, I deem it my duty or privilege to draw the attention of the First Presidency of the Church to conditions in these different countries as I found them in my travels.”[5]

While Jenson’s 1923 report did not immediately result in the dispatch of Mormon missionaries southward, it proved to be an important stepping-stone in that direction, seemingly turning the minds of the Brethren to consider opening new fields of labor. Thus the purpose of this introductory essay is to call attention to this overlooked landmark in the history of the Latter-day Saints in Latin America and to provide context to Jenson’s extensive north-south trip across the equator. Readers cannot fully understand nor appreciate the thirty-eight letters Jenson sent to be printed in the Deseret News without being aware of two things: the history of early Mormon missionary efforts in Central and South America and the growing Latter-day Saint fascination with Book of Mormon geography in the decades leading up to Jenson’s trip.

Early Mormon Missionary Efforts to Latin America

The earliest Latter-day Saint efforts to evangelize in Latin America developed during Joseph Smith’s lifetime. In April 1834, in Kirtland, Ohio, the Prophet gathered a number of Latter-day Saint men to a small, fourteen-foot-square schoolhouse for important instruction concerning the future of the Church. Although most of the priesthood holders at the time could fit into the modest-sized room, Smith promised his listeners that the gospel would spread and the “Church will fill North and South America—it will fill the world.”[6]

Despite Joseph Smith’s foresight, he did not deploy the first missionaries to South America until seven years after the Kirtland gathering. Joseph T. Ball, a Jamaican-American convert to the Church in Boston, Massachusetts, was called on August 31, 1841, to preach the gospel in South America. Ball was no stranger to missionary work; just two years earlier he had labored alongside Apostle Wilford Woodruff for several months in New England. Ball was expected to accompany Harrison Sagers as far as New Orleans, where the two would split for separate missions to South America and the West Indies, respectively. Members of the Quorum of the Twelve did not specify in which city or country Ball was to begin, perhaps leaving him to use good judgment. When he did not immediately embark for the southern hemisphere, Ball was reminded of his responsibility to travel southward a little over a month later in an early-October meeting of the Quorum of the Twelve. Still, for unknown reasons, Ball never fulfilled his missionary assignment.[7]

Further efforts to preach in South America were put on hold for the next decade, as members of the Church migrated to the Great Basin following the martyrdom of Joseph Smith in 1844. Even after overseas missionary work resumed, one important factor discouraged Church leaders from expansion southward: the Latter-day Saints had no familial, cultural, or language ties to Latin America. In contrast, Church leaders in the 1830s saw a number of converts accept the gospel and immigrate to Zion from places like Eastern Canada and the United Kingdom. Thus, Mormon missionaries were more eager to return to their homelands, preach to friends and family, and build the kingdom of God from centers of strength. Latter-day Saints did not yet have such connections in the southern parts of the New World.[8]

Finally, the first Mormon missionary made his way to South America after the Saints settled in Utah. In 1851, Apostle Parley P. Pratt traveled to California to preside over missionary work among the “islands and coasts of the Pacific.” The far-reaching mission covered “nearly one-half the globe,” including everything from California to China to the South Pacific, and Pratt ambitiously determined to oversee missionary work across the vast geography. Pratt was especially committed to preach to Native South Americans, whom he considered descendants of ancient Book of Mormon civilizations. Thus, together with his nine-months-pregnant wife Phoebe and missionary companion, Rufus C. Allen, he set sail for Chile in the fall of 1851. The trio would ultimately confront, as biographers Terryl L. Givens and Matthew J. Grow noted, “contested religious terrain,” particularly Catholicism’s sweeping presence in Latin America.[9]

With a small group of southbound travelers, Pratt sailed for sixty-four days on the Henry Kelsey, from September 5 to November 8. After an unpleasant voyage across the equator, they lodged at the Hotel ‘de France in Valparaíso, Chile, a coastal town about seventy-five miles northwest of the inland capital of Santiago. The Mormon missionaries immediately encountered the overarching presence of Catholicism and the limited religious liberty throughout the land, as the Chilean government “denied freedom of worship to other denominations, including the right to publish religious literature and hold services.” Political unrest, lack of food and money, the death of Phoebe’s newborn baby Omner, and Pratt’s difficulty with the Spanish language only made things worse.[10]

In mid-January 1852, the trio moved inland to Quillota, where they hoped new surroundings would bring better fortune. While the relocation alleviated some of the financial burden on the Mormon missionaries, a dense Catholic presence posed further evangelization obstacles, causing Pratt to alter his message from pro-Mormon to anti-Catholic. He denounced papal teachings and emphasized the need to be baptized by immersion until some literally “laughed [themselves] into hysterics.” By early March 1852, Pratt decided to abandon his ambitious undertaking, at least for the time being, and return to California to more effectively preside over the enormous mission and to better provide for his large, spread-out family. Nevertheless, his hope for future missionary work in South America would begin the following year.[11]

On August 28–29, 1852, at a special missionary conference, two thousand members of the Church packed into the Salt Lake Tabernacle to receive instruction from the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. After some initial remarks, President Brigham Young called on one hundred men to faithfully, and almost immediately, set out for missions around the world, including Africa, Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, France, Germany, India, Ireland, Norway, Prussia, Thailand, and the West Indies. Most of these countries did not already have missions established, and Church leaders expected the prospective elders to tarry overseas for several years. James Brown and Elijah Thomas were assigned to British Guiana, a small nation on the northernmost part of South America.[12]

While originally settled by Dutch colonizers in the 1500s, the land known as Guiana, or the Land of Many Waters, had come under British rule by the time the two Mormon elders embarked for South America in 1852. At the time, Guiana also covered much more acreage, including present-day French Guyana and Suriname. Catholicism prevailed throughout the territory, and the British made efforts to hinder the growth of other faiths. The Latter-day Saints proved to be anything but the exception.[13]

After being set apart by Heber C. Kimball of the First Presidency, Brown and Thomas started from Salt Lake City on October 18 and enjoyed an uneventful three-day journey to San Diego, California. They stayed in the Golden State for several days while securing passage on a ship to the Isthmus of Panama, where they hoped to disembark, trek across land by foot, and catch another ship along Panama’s Atlantic Coast to British Guiana. Without the Panama Canal to ford ships across land, this process was a typical course of action for travelers. On their way southward, yellow fever spread among the passengers, including Brown, who also became violently seasick from the tempestuous voyage. At one point during a storm, the Mormon missionaries, holding on for life within the ship’s cabin, believed the vessel was doomed to sink. However, Brown—too seasick to do so himself—told Thomas to leave the cabin, go to the upper deck of the ship, and rebuke the wind, which he did. The storm immediately ceased, and the passengers celebrated by thanking the Lord through prayer. The miracle seemed to prefigure smooth sailing and perhaps future missionary success for the two Mormon elders, but their luck would soon run out.[14]

The elders landed on the Pacific Coast of Panama on January 12, 1853, having sailed uncomfortably for eighteen days. Upon arrival they each acquired a mule for travel, rode overland to the seaports at Aspinwall (present-day Colón), and looked for a ship to finish their journey. At some point along the way, the missionaries had their luggage stolen, leaving them in want of food, clothing, and money.[15] Without the wherewithal to secure passage to British Guiana, they changed course and made their way to Kingston, Jamaica, where they landed on January 22 and stayed with four other Mormon elders serving on the West Indies isle. Finally they found a ship to British Guiana, but after paying for their tickets, the harbor agent boarded the ship, singled out the Mormon missionaries, put them on shore, and “said no such men could go to any English island or any boat they controlled.” Being forbidden to travel to their intended destination, Brown and Thomas gave up on preaching in British Guiana and parted company, Brown sailing to and preaching in New York and Thomas returning to Utah. Thus, as in the cases of Joseph T. Ball and Apostle Parley P. Pratt, Church leaders’ hope of establishing a mission in South America had dimmed once again.[16]

Two years later, in April 1854, President Brigham Young called Parley P. Pratt to preside a second time over missionary work in islands and coasts of the Pacific Ocean and to look for “new gathering places for the Saints.”[17] After six months of preaching in and around San Francisco, Pratt determined to explore new parts of California and the Pacific Northwest by calling for missionaries from Utah. On October 8, 1854, at the semi-annual general conference of the Church, the First Presidency called several missionaries to preach in the territories of Oregon and Washington as well as in the cities of San Diego and Santa Barbara, California. Interestingly, President Brigham Young further designated four elders, William Hyde, Lewis Jacobs, Isaac Brown, and John Brown, to evangelize in Valparaíso, Chile—the very place Pratt had labored unsuccessfully years earlier. When Pratt ceased his missionary efforts in South America in 1852, he openly regretted going to Chile and not Peru, a country that allowed “liberty of press, of speech, and of worship.” Yet the four new elders were inexplicably called in 1854 to Valparaíso rather than the more logical choice of Peru. No record exists about their experience in South America, suggesting they never fulfilled the assignment.[18]

The most contact the Church had with South America over the next two decades or so was in 1876, when Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil visited Utah on his tour across the United States. While generally enjoying visits to the Salt Lake Theater, Ogden hot springs, Salt Lake Tabernacle, and other sites in northern Utah, His Excellency did not leave with a very favorable outlook on Latter-day Saints because of “the harems of Brigham Young.” On the other hand, the Emperor’s vocal and public support for the Catholic Church in Utah reminded Mormon leaders of the strong Catholic presence in the southern countries of Latin America, “possibly reinforcing the view of South America Parley Pratt described over twenty years earlier.”[19]

Between 1852 and 1900, the federal government’s investigation into plural marriage, Utah’s bid for statehood, and other church-state conflicts overshadowed the ever-growing global expansion of the Latter-day Saints.[20] Still, by the turn of the century, missionary work in Latin America remained nonexistent beyond Mexico. That’s not to say the countries southward were not on the minds of Church leaders. In fact, in 1901, Church President Lorenzo Snow spent considerable time contemplating the role of the Apostles in “opening the door of the gospel to the nations of the earth.” He asked Brigham Young Jr., Acting President of the Quorum of the Twelve, to likewise reflect on his quorum’s scriptural responsibilities and to determine the “nations, not already visited, to whom the gospel might be carried by the Twelve.” In an October 1, 1901, meeting of the Twelve, Brigham Young Jr. explained how “his mind . . . rested upon South America, and possible fields might be opened up in Brazil, the Argentine Republic, La Plata [Argentina], Montevideo [Uruguay], and other places.” After some productive deliberation with the rest of his quorum members, Apostle John W. Taylor suggested “that an atlas be secured for reference and that a goodly portion of the time tomorrow be devoted to this subject.”[21]

The next day, October 2, the Quorum of the Twelve reconvened, studied the atlas, and together saw the “wisdom of opening the door of the gospel to South America.” They specifically imagined Montevideo, Uruguay, as an ideal location for mission headquarters and felt from there they could “extend the work into the regions round about.” In 1901 Montevideo was already becoming a metropolis-shipping hub with steam ferries across the bay to the greater Buenos Aires area. Newly completed railroads at the turn of the twentieth century helped transform Uruguay into a centralized locale between Brazil, Argentina, and the interior countries. Thus the Twelve wished not only to establish a mission there but also to “plant a colony” like the Mormon settlements in Northern Mexico. Moreover, John W. Taylor recommended that he and his brethren express their thoughts to the First Presidency the next day, and the decision among the Twelve was “carried by unanimous vote.” Mormon missionary work in South America once again seemed imminent.[22]

On Thursday, October 3, President Lorenzo Snow and his first counselor, Joseph F. Smith, met with the Twelve to discuss important matters pertaining to the Church’s upcoming general conference. Brigham Young Jr. made the highly discussed recommendation to open missionary work in South America, but the First Presidency was more reluctant and questioning than the Twelve had anticipated. President Snow, ailing from a lingering cold, “asked Brother Brigham as to whom the apostles would suggest to open a mission in South America. [Brigham] replied that the Twelve had no recommendation to make, but every one of them was ready to respond to a call.” No immediate decision was made, and President Snow took the matter under advisement. However, a week later, Snow passed away from pneumonia, and the matter of missionary work in South America was tabled for the time being.[23]

Six months later, at an April 1, 1902, meeting of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, Elder Reed Smoot assumed the decision regarding missionary work in South America had been postponed by the First Presidency, since the Twelve never heard back about the recommendation they had submitted months earlier. In June, Elder Heber J. Grant likewise wondered if missionary work in South America was still under consideration. He “remembered Pres. Snow’s last instructions to the effect that the apostles should be carrying the gospel to the nations” and believed “that in the near future there would be openings for the gospel in South America.”[24]

The lack of a Latter-day Saint presence in Latin America continued to concern members of the Quorum of the Twelve for years. However, the Apostles understood that the decision to open missionary work belonged to the First Presidency, and they remained reluctant to send themselves abroad without top-down approval from Joseph F. Smith, who had succeeded Lorenzo Snow as President of the Church. Still, members of the Twelve continued to express their opinion about missionary work from time to time in quorum meetings. In 1903, for example, John W. Taylor felt that South America was “being neglected” and “believed that that country ought to be visited by an apostle.”[25]

Over the next two decades, there were several forays by Latter-day Saints to South America but no apostolic visit. One venture began on August 6, 1906, when Hyrum S. Harris, president of the Mexican Mission, embarked on a two-man expedition into South America with Judge Henry Tanner of Payson, Utah, “to look for a new country for colonization purposes.” It is unclear whether leaders in Salt Lake City commissioned Harris to explore South America or if he went on his own impulse. Regardless, the two “never found what they were hunting for, neither did they find the probable location of Zarahemla, though they searched for it.” Harris returned to preside over the Mexican Mission until September 1907, when he was released and moved back to Utah.[26]

About twelve years later, in January 1919, Joseph J. Cannon, a prominent Latter-day Saint from Salt Lake City, moved with his wife and children to Colombia to pursue a business venture with the American Colombian Corporation. While there, he baptized his eight-year-old son, Grant, in the Magdalena River in April 1919, making him “the first in this dispensation to receive baptism in that land.” Cannon wrote several letters to President Heber J. Grant as well as Joseph Fielding Smith, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and the Church Historian. The Salt Lake City–based leaders encouraged Cannon to casually share the gospel, but they never called him as an official missionary or representative of the Church. The Cannon family remained in Colombia for about two years, after which they returned to Utah.[27]

Interestingly, Joseph J. Cannon lived in South America the same years his brother Hugh J. Cannon served an exploratory mission around the world with Elder David O. McKay of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Having a brother already residing in South America, Hugh Cannon and David McKay supposed that South America would be a logical place to pay a visit. Yet, for unknown reasons, the two globetrotters completed their extensive yearlong tour without visiting any part of Latin America.[28] Not long thereafter, however, the First Presidency finally sent someone southward to study the conditions of the countries of Central and South America, and that someone was an employee of the Church Historian’s Office, Andrew Jenson.

Expanding Lamanite Identity and Book of Mormon Geography

By 1923 assistant Church historian Andrew Jenson had long contemplated a trip to Latin America, after years of study of the Book of Mormon and a growing fascination with modern-day descendants of ancient Lehite America. Jenson had been interested in the Book of Mormon since boyhood, having read it over fifty times during his lifetime and revised its Danish translation twice. Therefore, the senior historian was well acquainted with the historical record of the ancient Nephites and Lamanites and believed that “to the Latter-day Saints it seems plain as daylight that some of [the ruins of Central and South America] at least are the remnant work of the ancient God-fearing and liberty-loving people called the Nephites.”[29]

Speculation by Latter-day Saints that Latin America was the location of ancient Book of Mormon lands was not necessarily new in the 1920s. Some Latter-day Saints had argued such theories since the earliest years of the Church. Joseph Smith and his contemporaries, for example, marveled at newly discovered ruins of Mesoamerican cities, and it was even common for official LDS newspapers, such as The Evening and Morning Star or Times and Seasons, to print stories about the recent archaeological findings in Central America. Even today, there exist maps and statements connecting Central and South America with Book of Mormon lands that were allegedly produced by Joseph Smith himself.[30]

Despite these early Mormon connections between Latin America and Book of Mormon civilizations, the Latter-day Saints primarily focused their missionary efforts on the American Indians of North America, whom they believed to be a branch of ancient Israelite lineage. Mormon missionaries began preaching the gospel among American Indians shortly after the constitution of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (now known as the Community of Christ) in 1830. The Lamanites in the latter days, according to prophecies in the Book of Mormon, would forsake their iniquitous past, embrace the true gospel of Jesus Christ, and help prepare the way for Christ’s Second Coming. Thus early Latter-day Saints saw American Indians “at the forefront of the eschatological drama then unfolding in preparation for the millennium.”[31] Whether a skeleton of Zelph, ruins of Nephite fortifications at Adam-ondi-Ahman, or burial grounds in Illinois, newly discovered relics of ancient America confirmed the faith of the Latter-day Saints in the Book of Mormon and its promises regarding the Lamanites.[32] While the first missions among American Indians proved unsuccessful, Latter-day Saints continued to hold them in high regard as a chosen people of God, waiting for them to “blossom as the rose.”[33]

Over the next fifty years and after their move to the Rocky Mountains, Latter-day Saints continued to reach out to the American Indians living along the western frontier in Utah Territory, oftentimes to no avail. Mormon missionaries enjoyed occasional missionary success but mostly encountered armed conflicts with Utes, Shoshone, and Southern Paiutes over the Great Basin’s limited resources and the various groups’ antithetical spiritual identity.[34] Latter-day Saints continued to wonder when American Indians would forsake their traditional religious background and accept the gospel as outlined in the Book of Mormon, which was not only a record of their history but also “a highly unusual manifesto of their destiny.”[35] In the meantime, Mormons “naturally extended [their] vision and researches to other tribes of Indians, besides those once powerful tribes within the boundaries of the United States.”[36] Lamanite identity thus shifted southward to Mexico, the Land of the Aztecs.

In June 1874, President Brigham Young, dissatisfied with the spiritual progress among the American Indians in Utah, called on two Mormon missionaries, Henry Brizzee and Daniel W. Jones, to introduce the gospel to Mexico. Young believed “that there were millions of the descendents of Nephi in the land” and felt obligated to reach out to “the children of Nephi, of Laman and Lemuel.”[37] In response, Brizzee and Jones formed a seven-man, ten-month, fact-finding expedition across the southern border of the United States and returned with a favorable report, including a recommendation to establish Mormon colonies in northern Mexico as a way to shelter those practicing polygamy and as a launching pad for spreading the gospel into the interior of Mexico. Perhaps the highlight of their journey, however, was coming across “some prehistoric ruins,” which the company noticed “had been large and several stories high.” The excitement surrounding further discoveries of ancient walled cities and fascinating sculptures confirmed, in the minds of curious and inquiring members of the Church, Mexico and the countries southward were indeed “the land where the Nephites flourished in the golden era of their history.”[38]

Some Latter-day Saints were eager to know the whereabouts of bygone Book of Mormon lands and would use scriptural passages, modern-day geography, and the abundance of ancient-American archaeology as a means to “locate” them.[39] To these members of the Church, positioning the acreage of ancient American Indians not only helped missionaries find “pure-blood Lamanite descendents,” but it also legitimized the validity of their sacred scripture, the Book of Mormon. Using physical evidence to support “the American scripture” snowballed toward the end of the nineteenth century, as reflected in well-circulated literature, including Apostle Orson Pratt’s 1879 edition of the Book of Mormon, George Reynolds’s 1891 Dictionary of the Book of Mormon, B. H. Roberts’s 1895 New Witness for God, and James E. Talmage’s 1899 Articles of Faith. Furthermore, by the turn of the twentieth century, a zealous expedition by members of the Church to find the location of the ancient Nephite capital of Zarahemla was not only commended, but it was also celebrated with parades, brass bands, and banquets.

On April 17, 1900, Benjamin Cluff Jr., president of Brigham Young Academy in Provo, Utah—which became Brigham Young University in 1903—organized a rather large, student-heavy, twenty-three-man march through the lush jungles of Central America, across what they believed to be the “narrow neck” at the Isthmus of Panama, with hopes of reaching the Republic of Colombia by year’s end. Literature and religion scholar Terryl L. Givens called the ambitious undertaking “a search for a Mesoamerican Troy.”[40] The city of Zarahemla was widely believed in some Latter-day Saint circles to have been located along the banks of the Magdalena River—the principal waterway of Colombia, flowing northward one thousand miles from the Andes Mountains to the Caribbean Sea. With the support of the Church’s highest officials, President Cluff’s longtime dream to take leave from Brigham Young Academy, uncover the city of Zarahemla, and substantiate the Book of Mormon seemed imminent. However, as Givens also wrote, “this first effort to authenticate the New World scripture was premature by any standard.”[41]

Frustrating delays along the way into Latin America as well as disunion among the travelers caused most of Cluff’s party to give up and return home before leaving United States territory. Despite being counseled to abandon the trip by Apostle Heber J. Grant at the Mexican border and later by Joseph F. Smith of the First Presidency, Cluff continued with his remaining contingent “to the wilds of strange lands.” Members of the expedition, traveling twenty-five miles a day and suffering all manner of affliction, including disease, hunger, snake bites, and even prison time, regularly penned lengthy missives about their travels and mailed them to Salt Lake City, where they were printed in the Deseret Evening News and perused by far-reaching readership.[42] By the time Cluff finally arrived in Colombia in December 1901, only six explorers remained, and violent conflict between Colombian revolutionists in the War of a Thousand Days prevented Cluff from conducting his research on the Magdalena River. One of the Brigham Young Academy professors, Chester Van Buren, tarried alone to collect wildlife samples for his botany research, while Cluff and the rest of his crew returned to Utah, arriving home on February 7, 1902.[43] While Cluff never uncovered ruins of the city of Zarahemla, his expedition “succeeded in stimulating interest in the Book of Mormon and Mesoamerican antiquities” and motivated curious members of the Church to embark on similar ventures not long thereafter.[44]

In fact, one year later, in February 1903, Joel Ricks Jr., a longtime Latter-day Saint student of American antiquities and secretary of the Book of Mormon Society at Brigham Young College in Logan, Utah, began a solo expedition to South America “in order to familiarize himself with the country formerly occupied by the Nephites.” He specifically set his sights on Colombia, where he, like Benjamin Cluff and others, believed the Magdalena River to be the River Sidon, with Zarahemla along its banks. Also like Benjamin Cluff’s South American exploration party, Ricks regularly corresponded with the Deseret Evening News, printing his letters and photographs as a series of articles entitled “In Book of Mormon Lands.”[45] Perhaps his anticipated return from South America in June 1903 helped increase interest in Book of Mormon geography, which was the theme of a convention at the Brigham Young Academy in Provo, Utah, in May of that year.

At the 1903 conference in Provo, Utah, Church President Joseph F. Smith cautioned overzealous Latter-day Saints “against making the union question—the location of the cities and lands—of equal importance with the doctrines contained in the [Book of Mormon].” This was perhaps the first occasion of a general Church leader reproving enthusiastic Book of Mormon geographers, and subsequent Church Presidents would echo Smith’s admonition. Still, Smith presided over the conference, found interest in the lectures, and even “endorsed the remarks of Dr. [James E.] Talmage and Elder [B. H.] Roberts,” both of whom presented their own ideas regarding external evidences of the Book of Mormon and the location of Nephite lands. Interestingly, one of the prominent people present at the conference was Andrew Jenson, who represented the Church Historian’s Office, along with Charles W. Penrose and Orson F. Whitney.[46]

The discouraging statements by President Joseph F. Smith apparently had no effect on Joel Ricks, who returned from Central and South America in June 1903 only to depart again for an even more historic exploration in September 1908. This second four-month trip southward resulted in a meticulously detailed and colorfully illustrated map of North, Central, and South America as the lands of the Book of Mormon, which Ricks began printing and distributing in 1915 to members of both The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. The map “confirmed” the Republic of Panama as the “narrow neck of land,” the countries of Colombia and Venezuela as the Land of Zarahemla, and the Magdalena River as the River Sidon, which were already widely held ideas, as described above. Furthermore, Ricks’s map included Lehi’s landing in southern Chile, the Land of Nephi in the Andean States of Ecuador and Peru, and many other Book of Mormon cities and geographical features throughout the Americas, including the Hill Cumorah in upstate New York. The map was printed as an appendix to Ricks’s self-published Helps to the Study of the Book of Mormon (1916), which also included photography from Ricks’s travels, a narrative history of the LDS Church, and a comprehensive glossary of Book of Mormon names, places, and other terms. The map portion of the study guide was especially popular among Latter-day Saints, and while it did not include any ecclesiastical endorsement or top-down approval, it spread until being used “in all Sunday Schools of the Church.”[47]

By 1921 Ricks had distributed over 6,000 copies of his maps, placing him at the forefront of amateur Book of Mormon cartographers at the time. Having never had the opportunity to personally present his maps to the General Authorities of the LDS Church, Ricks inquired of such an opportunity through a letter to Elder James E. Talmage, member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and chairman of the newly formed Book of Mormon Committee, which had only recently been formed in 1919. The committee had been formed in order to prepare a new edition of the Latter-day Saints’ sacred scripture, with the primary responsibility to conduct extensive research and prayerful investigation into some of the often-misunderstood passages in the Book of Mormon. However, two years into the project and after increased interest among the Latter-day Saints in the whereabouts of ancient Nephite and Lamanite lands, the committee “began hearing some of the proponents of different views on Book of Mormon geography.” Talmage even wittingly quipped, “Not a few maps have been put out.”[48]

One by one, several good-standing Latter-day Saints brought their ideas, maps, and conclusions to the four-day-long “Book of Mormon hearing,” January 21–24, 1921. Ricks, of course, made a case for northern South America as the primary setting of the Book of Mormon, while Willard Young, a supervisor over the LDS Church’s building program, campaigned for Guatemala and Honduras, and Elder Anthony W. Ivins, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, advocated for the Yucatán and Mexico. All three men had personally visited their respective regions and based their arguments on the latest archaeological discoveries. Talmage and the rest of the committee recessed on January 24 to consider the various Book of Mormon geographical theories, but the committee members, as far as can be surmised, never reconvened. Still, the buzz about the “Book of Mormon hearing” had already begun to spread at Church headquarters in Salt Lake City, easily reaching the Church Historian’s Office, where Andrew Jenson labored as an assistant Church historian.[49]

The Andrew Jenson-Thomas Page Latin American Expedition

A little over a month after the proposals to the Book of Mormon Committee, on March 2, 1921, Anthon H. Lund, first counselor in the First Presidency, the Church Historian and Recorder, and a fellow Dane, instructed Andrew Jenson to visit the Mexican Mission and gather pertinent data for the Church’s ongoing historical record. Jenson quickly complied, not wanting to miss the opportunity to go to a part of the world he had not previously visited. This first trip to Latin America would have a profound effect on him.[50]

Jenson rendezvoused at the United States–Mexico border with Rey L. Pratt, a member of the First Council of Seventy, president of the Mexican Mission, and a grandson of Parley P. Pratt. The two then traveled together to the mission’s headquarters in Mexico City and eventually to the Gulf of Mexico. Along the way, Jenson and Pratt visited ancient Aztec and Olmec ruins in Chapultepec, Mexico City, Puebla, and Vera Cruz, which captured Jenson’s imagination. He was especially moved by the Mexico City Metropolitan Catholic Cathedral, which was built atop the ruins of an age-old Aztec temple after Hernando Cortés of Spain conquered the region in the 1520s. Additionally, the impressive pyramids at Teotihuacan, particularly the 230-foot-high Temple of the Sun, about thirty miles northeast of Mexico City, awed Jenson. “It is not known who built these massive structures or when they were erected,” he noted that night in his journal.[51] Personally witnessing the imposing pyramids and timeworn ruins throughout Mexico caused Jenson to wonder about the modern-day descendants of the ancient Book of Mormon Lamanites and their role in the latter days. Jenson later admitted that it “was something I cannot dismiss from my mind upon my return home.”[52]

Jenson’s interest in these age-old relics and their connection to the Book of Mormon was reflected in several speaking assignments after his return to Salt Lake City. For example, on August 6, 1921, just two weeks after his special mission to the Latter-day Saint historic sites and the Republic of Mexico, Jenson visited a congregation at the Alpine Stake Tabernacle in American Fork, Utah, and “told of the future mission of the American Indian as referred to in the Book of Mormon.”[53] Furthermore, two months later at an October general conference overflow meeting at the Assembly Hall in Salt Lake City, Jenson detailed his special mission to Mexico and added to the already evolving conception that Central and South Americans are the modern-day Lamanites. He related:

While visiting old Mexico, together with President Rey L. Pratt and others, on my late mission, I began to study with greater interest than ever before the predictions contained in the Book of Mormon regarding the Lamanites and the possible fulfillment of these predictions. The remnants of the House of Israel, now known as the North American Indians, have so far disappointed us to a certain extent. We have had missionaries among the Indians since the beginning of 1831, and some of the very best and most faithful elders in the Church have devoted the principal part of their lives endeavoring to learn the various languages or dialects spoken by the several tribes of Indians in the United States. But after all their efforts in that regard they have only been able to reach a few people, and their labors have resulted in bringing a still smaller number of Lamanites to the knowledge of the truth. . . . We, therefore, cast a glance southward into old Mexico and through the great countries beyond—down through Central America and South America, where there are millions and millions of Lamanites, direct descendents of Father Lehi. . . . I would further suggest that whenever the time comes that these Lamanites in the south shall embrace the gospel, there will be a sufficient number of them to fulfill every prediction contained in the Book of Mormon concerning the Lamanites, and justify every expectation that we have had in regard to the help which these remnants of the House of Israel shall render in building up Zion in these last days.[54]

Jenson’s predictive declarations at the October 1921 general conference launched his personal campaign to convince Latter-day Saint leaders to reach out to the Latin American populations and spread the gospel into what he and many others considered Book of Mormon lands in Central and South America.

A year later, at the October 1922 general conference of the Church, Jenson again addressed an overflow meeting outside the Salt Lake Tabernacle about the future of the Lamanites living in the southern countries of the American continent. Almost verbatim from his discourse a year before, Jenson explained how the Native Americans in the United States “have disappointed us to a certain extent” as they “have not embraced the gospel in such numbers as we expected.” He then urged his audience to imagine the “millions and millions of another class of Lamanites, more civilized, in the South. . . . We hope the time will come when they will embrace the gospel in large numbers, and thus be able to fulfill everything contained in the Book of Mormon by way of prediction concerning that race.”[55]

Jenson also related an account of the Mormon Battalion, a Latter-day Saint contingent in the Mexican-American War from 1846 to 1847, to his general conference listeners. The five-hundred-member battalion’s nearly two-thousand-mile overland journey from Iowa to California was among the longest infantry marches in United States military history. While the Church Historian’s Office already housed documentation of the Mormon Battalion’s historic expedition, Jenson told onlookers of the need to collect even more information about not only the battalion but also the ship Brooklyn that brought early Latter-day Saint settlers to Northern California, the Mormon involvement in the California gold rush, and the Church’s settlement at Winter Quarters, Nebraska, between 1846 and 1848. These events, if not properly recorded, would become forgotten affairs in the annals of the Church’s history.[56]

Jenson’s longing to visit Latin America, coupled with his desire to compile historical information of early Latter-day Saints in California, culminated into a written request to President Heber J. Grant on January 5, 1923. His lengthy letter included several offers and requests—to donate his large collection of books to the Church Historian’s Office, to be refunded ten thousand dollars from previous Church history–related travels, and to take leave from his labors in Salt Lake City and enjoy a vacation trip to Central and South America.[57] After years of what he called “strenuous efforts” in gathering, compiling, and making inventory of the large collections of minute books, manuscripts, and other historic artifacts at the Church Historian’s Office, Jenson found his “eyesight impaired and threatening to a degree of nervousness.” He claimed never to have taken a vacation and believed in order to properly complete his life’s work, he needed “to get a little change.”[58]

While awaiting a reply from President Grant about his contemplated trip to Latin America, Jenson moved forward with his travel preparations. The following week he completed his medical evaluations, secured an updated passport, received letters of introduction, and created a tentative itinerary.[59] Thomas Phillips Page, his would-be travel companion, had already begun updating his passport for the trip southward on January 3, before Jenson had ever brought the idea to the First Presidency. Clearly the two men had been thinking about the pending trip for some time.

Thomas P. Page proved uniquely prepared for the imminent spin southward with Jenson. He was a fellow world traveler, amateur historian, and charter member of Jenson’s Round the World Club in Salt Lake City.[60] Page, described as a hard-of-hearing, often stuttering, toupee-wearing “smart duck,” owned his own mercantile in Riverton, Utah—the largest trade operation in the county outside Salt Lake City. He had served a three-year Mormon mission to Turkey from 1899 to 1901 and made a trip around the world from 1911 to 1912, visiting countries like Japan, China, the Philippines, Burma, India, Egypt, France, and England. In 1922, the year before the Jenson-Page expedition to Latin America, Page traveled along the west coast of Central America and crossed the Panama Canal on a pleasure trip to Cuba. Thus Page was already familiar with a large part of the southward journey.[61]

Having not received a formal reply from the First Presidency nearly two weeks after his initial request, Jenson again asked for approval through a January 16 letter to President Grant, who had traveled to California several days before. As the presiding quorums held the responsibility of opening missionary work in foreign lands, perhaps they felt reluctant to send Jenson southward and do what could be seen as their duty. Grant also wondered if the proposed trip was worth the hefty expense, as Jenson expected to be reimbursed for his incurred costs throughout Latin America as he had been on similar trips for the Church Historian’s Office.[62] Grant eventually responded by sending what Jenson called “an ambiguous telegram” to Anthony W. Ivins, second counselor in the First Presidency, giving only partial approval of the Latin American expedition and asking Jenson to pay his own way. Ivins then related the message to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in their weekly Thursday morning meeting with the First Presidency.[63]

Later that Thursday afternoon, January 18, Apostles Melvin J. Ballard, John A. Widtsoe, and Joseph Fielding Smith visited Jenson at his home to evaluate the personal library of books and manuscripts being offered to the Church Historian’s Office. After agreeing to acquire the large collection, Elder Smith informed Jenson that he could visit Latin America but “not as a regularly called missionary” and “not as a Church representative.”[64] While Jenson planned to, and ultimately did, compile historical information about Mormon pioneers in California and survey Latin America for the prospect of opening missionary work, the Brethren determined the trip to be a vacation and thus expected Jenson to pay for passage and board. Thomas Page willingly covered much of the cost.[65] It would be Apostles, not historians, who opened new missionary fields.

The following Monday, January 22, Jenson and Page bade farewell to their families and embarked on the much-anticipated expedition through Book of Mormon lands. They began by exploring historic sites of early Latter-day Saint pioneers in California, culling information related to the ship Brooklyn, which brought a large contingent of 238 Mormons from New York to Yerba Buena (present-day San Francisco) in 1846. At times the duo split up, Page making arrangements to sail southward and Jenson visiting the state library in Sacramento to research the Latter-day Saint involvement in the California gold rush as well as the march of the Mormon Battalion. After nine days in the Golden State, the two travelers sailed on the Colombia for the Panama Canal.[66]

Along the way the Colombia stopped at coastal towns in Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua. As a routine, Jenson and Page disembarked at each stop; gathered geographical, economical, and demographical details of each country; organized them in letters to the Deseret News; and sent them to Utah to be read by the curious Latter-day Saint readership. While waiting for a ship to South America at the Panama Canal, remaining there for about a week and a half, Jenson marveled at the workmanship of the massive waterway. He noted in his journal, “I had heard and read much about the Panama Canal, but I never could appreciate or understand the grandeur of the work until I saw it.”[67]

The two travelers left what they considered the “narrow neck of land” on March 1 and sailed for South America. They became just a few of the Latter-day Saints to set foot on South American soil in almost seventy years—since Apostle Parley P. Pratt in 1852. They landed in Peru, or the Land of the Incas, and paid particular attention to the ruins of bygone civilizations. Page even called the inland city of Cuzco, Peru, “the important place in America” because of the “ruins of temples and buildings of the Inca Indians before the coming of the Spanish to America.”[68] From Peru, the duo traveled by rail to the republics of Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina.

Argentina in particular left a lasting impact on Jenson. He found the capital of Buenos Aires comparable to his native Copenhagen, Denmark, and found a colony of Danes living outside the city. Jenson and Page even stayed at the Hotel Scandinavia during their nine-day stopover. After receiving the invitation, Jenson delivered a lecture on Utah and the Mormons to a group of curious Danes. He would have taken the opportunity to visit their homes and expound on the teachings of the Latter-day Saints, but he found it best not to preach without permission from President Heber J. Grant.[69] They continued their trip on April 12, passing through Uruguay, Brazil, and the West Indies on their lengthy homeward journey. Jenson learned in New York, while staying with his daughter Eleanore and her husband, George B. Reynolds, that President Grant disapproved the idea of returning to Utah by way of the overland Mormon Trail, so the two travelers arrived in Salt Lake City by train.[70]

Conclusion

Jenson and Page arrived home in Utah on May 10, 1923, and immediately began publicizing their adventurous southward exploration. Three days following their return, for example, Jenson addressed a congregation at the Granite Stake Tabernacle about his recent travels. He similarly spoke at the Salt Lake Tabernacle two weeks later, making a number of comparisons between the ruins, relics, and artifacts he saw in Latin America with various Book of Mormon passages related to the architecture, wars, and tools of the Nephites, Lamanites, and Jaredites of antiquity. He rhetorically asked the Mormon congregation, “Who built these fortifications? . . . It is a strange thing that intelligent people will not at least give the Book of Mormon a thought and a trial. They may not give its narrative full credence at once, but that book is the only book that gives us any important clue as to who these pre-historic people were.”[71]

Obviously, Jenson was not the first to champion such widely held ideas on Book of Mormon geography, but he was the foremost Latter-day Saint at the time, as assistant Church historian, to personally visit the countries of Central and South America and make those assessments. His lectures on Latin Americans as Lamanites gave newfound legitimacy to those already trending notions. However, Latter-day Saint General Authorities, as begun by President Joseph F. Smith in 1903, would continue to emphasize that “there has never been anything yet set forth that definitely settles the questions” of Book of Mormon geography. Still, Jenson’s 1923 trip and subsequent discourse brought a new sense of credibility to the arguments.[72]

After his discourse at the Salt Lake Tabernacle, Jenson continued to speak enthusiastically about his Latin American exploration not less than fifteen times between May and November 1923 at a number of venues, including the Sugar House Ward meetinghouse, Murray Second Ward meetinghouse, Ogden Stake Tabernacle, Salt Lake Seventeenth Ward meetinghouse, Mount Pleasant Ward meetinghouse, the Tooele South Ward meetinghouse, and Liberty Park, among others. Thomas Page also lectured at several events, including the Exchange Club meeting at the Hotel Utah and the Round the World Club meeting at his home in Riverton, Utah.[73]

Everywhere the duo visited, they described Latin America as the primary location of Book of Mormon civilizations and how the countries of Central and South America seemed ready for missionary work. They would encourage young men “to learn Spanish, so they can go on missions to South America.”[74] “Even in Brazil,” Jenson would say, “where the Portuguese language is the language of the country, a great number of people can speak and understand Spanish.” He could not “tell how willing the people of Latin America will be to listen to the restored gospel, but among so many it is reasonable to suppose that at least a small percentage would be interested in the declaration that God has raised up a prophet in our day and generation.”[75]

Jenson’s speaking tour, including his formal assessment to the First Presidency as mentioned above, did not immediately result in the sending of missionaries to Latin America. The First Presidency would not open the South American Mission for another two years, in December 1925, but Jenson’s report seemed to turn the minds of the senior Brethren to the lands of ancient Aztecs, Mayas, and Incas. When Apostle Melvin J. Ballard was called in September 1925 to take the gospel to South America, for example, he noted in his diary that “the First Presidency had had under consideration for a year and a half the question of opening a mission in South America,” dating the start of its consideration to roughly the time of Jenson’s report and various speaking assignments.[76]

Historically, a chain of events seems to always precede the opening of missionary work in every nation with a Latter-day Saint presence. Latin America followed the same pattern, beginning with prophecies by Joseph Smith in the 1830s. Jenson’s scarcely studied 1923 exploration of Book of Mormon lands proved to be another important link leading to the opening of the South American Mission in 1925.

Notes

[1] Andrew Jenson to Heber J. Grant, July 11, 1923, Church History Library.

[2] “Andrew Jenson Returns from 30,000 Mile Trip,” Salt Lake Telegram, August 14, 1935, 16.

[3] See Davis Bitton and Leonard J. Arrington, Mormons and Their Historians (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1988), 41–54.

[4] Andrew Jenson to Heber J. Grant, July 11, 1923.

[5] Andrew Jenson to Heber J. Grant, July 11, 1923.

[6] Wilford Woodruff, in Conference Report, April 1898, 57.

[7] Manuscript History of the Church, August 31, 1841 and October 7, 1841, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[8] Gordon Irving, “Mormonism and Latin America: A Preliminary Historical Review,” typescript, 1976, p. 4, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[9] Terryl L. Givens and Matthew J. Grow, Parley P. Pratt: The Apostle Paul of Mormonism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 290, 300.

[10] Givens and Grow, Parley P. Pratt, 308.

[11] Givens and Grow, Parley P. Pratt, 312–13.

[12] Reid L. Neilson, “Errand to the World: The 1852 Mormon Missionary Conference,” presentation at the annual conference of the Mormon History Association, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, June 2012.

[13] Barton Premium, Eight Years in British Guiana: Being the Journal of a Residence in that Province, 1840–1848 (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1850), 283.

[14] James Brown to George A. Smith and Robert L. Campbell, June 3, 1865, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[15] Edward W. Tullidge, Tullidge’s Histories: Volume 2, Containing the History of all the Northern, Eastern, and Western Counties of Utah, also the Counties of Southern Idaho, with a Biographical Appendix of Representative Men and Founders of the Cities and Counties (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor, 1889), 106.

[16] James Brown to George A. Smith and Robert L. Campbell, June 3, 1865, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[17] As cited in Givens and Grow, Parley P. Pratt, 390. See also Manuscript History of the Church, October 7, 1854, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[18] A. Delbert Palmer and Mark Grover, “Hoping to Establish a Presence: Parley P. Pratt’s 1851 Mission to Chile,” Brigham Young University Studies 38, no. 4 (1999): 117–18.

[19] Palmer and Grover, “Hoping to Establish a Presence: Parley P. Pratt’s 1851 Mission to Chile,” Brigham Young University Studies 38, no. 4 (1999): 130. See David L. Wood, “Emperor Dom Pedro’s Visit to Salt Lake City,” Utah Historical Quarterly 37, no. 3 (Summer 1969): 337–52.

[20] In May 1887, John Taylor, who was serving as President of the Church, received a letter from “Col. Ackerman” of Arequipa, Peru, wherein Ackerman gave “a description of the region and the advantages it offer[ed] to a people like the Latter-day Saints.” President Taylor found the idea of colonizing parts of Peru “very fascinating,” but he declined the offer. He wrote in response, “At the present we are not in a position to avail ourselves of the opportunity which you present.” No further word was heard from Colonel Ackerman. See John Taylor to Colonel Ackerman, May 20, 1887, John Taylor Family Papers, box 1B, folder 35, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

[21] Stan Larsen, ed., A Ministry of Meetings: The Apostolic Diaries of Rudger Clawson (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1993), 320.

[22] Larsen, Ministry of Meetings, 320.

[23] Larsen, Ministry of Meetings, 322.

[24] Larsen, Ministry of Meetings, 455.

[25] Excerpts from Weekly Council Meetings, George Albert Smith Papers, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

[26] See Rey L. Pratt, “History of the Mexican Mission,” Improvement Era, April 1912, 497. See also Hyrum Smith Harris Biographical Sketch, Hyrum S. Harris Collection, MS 9961, folder 4, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[27] See Joseph Fielding Smith to Joseph J. Cannon, June 13, 1919, Ramona Wilcox Cannon Papers, MS 1862, box 45, folder 1, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

[28] See Hugh J. Cannon and Reid L. Neilson, ed., To the Peripheries of Mormondom: The Apostolic Around-the-World Tour of David O. McKay, 1921–1922 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2011).

[29] Andrew Jenson, “Ancient Ruins in South American Lands Held to Be Evidence of Divine Authenticity of Book of Mormon,” Deseret News, June 6, 1923, 7.

[30] See Terryl L. Givens, By the Hand of Mormon: The American Scripture That Launched a New World Religion (New York: Oxford University Press, 89–116.

[31] Armand L. Mauss, All Abraham’s Children: Changing Mormon Conceptions of Race and Lineage (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003), 41.

[32] See Givens, By the Hand of Mormon, 96–101.

[33] Doctrine and Covenants 49:24

[34] See W. Paul Reeve, Making Space on the Western Frontier: Mormons, Miners, and Southern Paiutes (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2006), 1–9.

[35] Ronald W. Walker, “Seeking the ‘Remnant’: The Native American during the Joseph Smith Period,” Journal of Mormon History 19, no. 1 (Spring 1993): 3.

[36] Andrew Jenson, in Conference Report, October 1921, 120.

[37] Daniel W. Jones, Forty Years among the Indians: A True Yet Thrilling Narrative of the Author’s Experience among the Natives (Salt Lake City: The Juvenile Instructor’s Office, 1890), 220.

[38] Brigham Young to William C. Staines, January 11, 1876, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[39] For further information regarding early Mormon missionary activity in Mexico and the evolving conception of Mexicans as descendants of Book of Mormon peoples, see Matthew G. Geilman, “Taking the Gospel to the Lamanites: Doctrinal Foundations for Establishing the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Mexico” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2011), 8–46.

[40] Givens, By the Hand of Mormon, 106–7.

[41] Givens, By the Hand of Mormon, 106–7.

[42] Members of the Brigham Young Academy South American expedition mailed back at least half a dozen letters to the Deseret Weekly News, which were printed between June and December 1901.

[43] According to one newspaper account, Chester Van Buren remained in South America not only to collect plant and wildlife samples but also “to do missionary work.” However, no record exists of his apparent proselytizing efforts. See “Brigham Young Academy,” Deseret Evening News, September 27, 1902, 15. Another member of the expedition, Paul Henning, remained in Guatemala to study wildlife, botany, and ancient Mayan ruins. He received an official missionary call from the First Presidency in October 1901 to preach to the people of Guatemala. However, his short-lived mission proved unsuccessful, and he returned in early 1902. See Robert W. Fuller, “Paul Henning: The First Book of Mormon Archaeologist,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 9, no. 1 (2000): 64–65, 80.

[44] Givens, By the Hand of Mormon, 107–8. Interestingly, in November 1902, Benjamin Cluff’s uncle, Alfred A. Cluff, and other extended family members moved from Graham County, Arizona, to southern Guatemala in hopes of establishing a Latter-day Saint colony. The fertile and low-priced land seemed to be a promising business venture. The party had repeatedly asked the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles for permission to relocate southward, and they left after a year of no response. Once members of the Twelve learned of the Cluff family’s change of address, a letter was sent encouraging them to return. The Cluffs moved back to Arizona almost immediately in August 1903. See Larsen, Ministry of Meetings, 313. See also Harvey H. Cluff to the First Presidency, August 11, 1902, Scott G. Kenney Collection, MS 587, box 10, folder 10, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

[45] Ricks mailed back at least ten letters to the Deseret Evening News, which were printed between May and July 1903.

[46] “Book of Mormon Students Meet,” Deseret Evening News, May 25, 1903, 7.

[47] David O. McKay to Joel Ricks, March 28, 1919, Joel Ricks Papers, MSS 2857, box 1, folder 7, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

[48] James E. Talmage, journal, January 14, 1921, James E. Talmage Papers, MSS 229, box 6, folder 1, L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

[49] James E. Talmage, journal, January 21–24, 1921, James E. Talmage Papers, MSS 229, box 6, folder 1, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. The author would like to thank Joseph T. Antley for bringing to light these journal entries.

[50] For an account of Jenson’s two-week trip through Mexico, see Andrew Jenson, diary, March 2–13, 1921, 30–43, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[51] Andrew Jenson, diary, March 9, 1921, 38, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[52] Andrew Jenson, in Conference Report, October 1921, 119.

[53] “Two Days Quarterly Conference Well Attended,” American Fork Citizen, August 6, 1921, 5.

[54] Andrew Jenson, in Conference Report, October 1921, 119–20.

[55] Andrew Jenson, in Conference Report, October 1922, 132.

[56] Andrew Jenson, in Conference Report, October 1922, 129–31.

[57] Andrew Jenson to Heber J. Grant, January 5, 1923, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[58] Andrew Jenson to Heber J. Grant, January 16, 1923, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[59] Andrew Jenson to Heber J. Grant, January 16, 1923, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[60] The Round the World Club was a Utah-based organization, established by Andrew Jenson on May 15, 1913, with a total of seven members, including Thomas P. Page. To be inducted into the club, one had to have circumnavigated the globe, which according to Jenson was 24,901 miles. Club members met four times a year and shared stories of their distant travels. See Andrew Jenson, Autobiography of Andrew Jenson, Assistant Historian of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1938), 513–14.

[61] Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia: A Compilation of Biographical Sketches of Prominent Men and Women in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Western Epics, 1971), 2:318. See also Thomas P. Page Scrapbook, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[62] Andrew Jenson to Heber J. Grant, January 16, 1923, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[63] Andrew Jenson Diary, January 22, 1923, 267, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[64] Joseph Fielding Smith to Heber J. Grant, January 18, 1923, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[65] Andrew Jenson to Heber J. Grant, January 16, 1923, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. President Grant seemed unsettled over Jenson’s initial request to be reimbursed ten thousand dollars for previous Church history–related travels. Thus Jenson, as far as available sources suggest, never heard back about that request and was asked to pay his own way through Latin America.

[66] See Andrew Jenson, Autobiography of Andrew Jenson, Assistant Historian of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1938), 547–50.

[67] Andrew Jenson Diary, February 19, 1923, 287, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[68] Thomas P. Page to Maud Butterfield, March 15, 1923, Thomas P. Page Scrapbook, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[69] Andrew Jenson Diary, April 11, 1923, 330–31, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[70] Andrew Jenson Diary, May 3, 1923, 350, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[71] Andrew Jenson, “Ancient Ruins in South American Lands Held to Be Evidence of Divine Authenticity of Book of Mormon,” Deseret News, June 2, 1923, 7.

[72] “Book of Mormon Students Meet,” Deseret Evening News, May 25, 1903, 7.

[73] Jenson’s speeches are made known in short diary entries and brief notices in the Salt Lake Telegram. He likely used the same lengthy discourse at the many venues he visited, which was printed as “Ancient Ruins in South American Lands Held to Be Evidence of Divine Authenticity of Book of Mormon,” Deseret News, June 2, 1923, 7. For a full transcript of the discourse, see appendix 3 in this volume.

[74] Round the World Club Minutes, August 2, 1923, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[75] Andrew Jenson, “Ancient Ruins in South American Lands Held to Be Evidence of Divine Authenticity of Book of Mormon,” Deseret News, June 2, 1923, 7.

[76] As cited in Bryant S. Hinckley, Sermons and Missionary Services of Melvin J. Ballard (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1949), 89.