The Golden State: California, January 1923

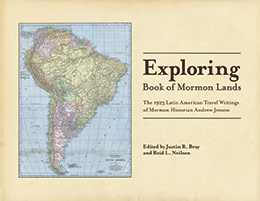

Justin R. Bray and Reid L. Neilson, eds., Exploring Book of Mormon Lands: The 1923 Latin American Travel Writings of Mormon Historian Andrew Jenson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2014), 29–66.

“Jenson’s Travels, Excerpts from the Journal of Andrew Jenson on His Journey to the Pacific Coast, Central America, South America, and Other Parts of the Western World,” January 25, 1923[1]

Placerville, Eldorado County, California

I have done service as a correspondent to the Deseret News since 1873, when I left my home in Utah to fill my first mission to Scandinavia.[2] I was then only twenty-two years old; now I am fifty years older.[3]

I am starting out on what may perhaps be my last long journey in mortality, and I feel impressed on this occasion to write to our Church organ[4] an account of my travels in journal form and give a sample of how the world looks through the eyes and understanding of a Mormon elder of advanced years and how a man after having had all kinds of experience and endured hardships and disappointments is still clinging with a firm grip to the “faith once delivered to the Saints.”[5]

I have in past years traveled extensively as a missionary and historian for the Church,[6] have visited many lands and climes, and have circumnavigated[7] the globe twice; and, after making this tour on which I am now starting to Central and South America, I shall feel that I have had enough and that I shall be satisfied to spend the remainder of my years in the gathering places of the Saints; and I trust that I, with my knowledge of good and evil and right and wrong, may be enabled to impress the young and rising generation of Latter-day Saints with faith-inspiring inspirations or that which will make them wise unto salvation.[8]

Monday, January 22. I bade farewell to my family and dear ones in the city which I love—love it because it is the place where many of the faithful sons and daughters of God reside and where my own domicile has been located for upwards of forty years.[9] With Elder Thomas P. Page,[10] of Riverton, Utah, as a traveling companion, I left Salt Lake City at 1:00 p.m. on a Western Pacific train for California.[11] After parting with relatives and friends at the railway depot,[12] we enjoyed the ride across the southern extremity of the Great Salt Lake. When the railroad was first built, the grade was hugging the shore of the Great Salt Lake very closely, but now, as the water in the lake has risen several feet, a strip of water of considerable width separates the roadbed from the south shore of the great inland sea. Tooele Valley, with its settlements on the south and the lake and Church Island on the north, caused the passengers to look first in one direction and then in the other with continued interest—the lake, of course, being very closely observed by those who have not seen it before. On such occasions a Mormon elder can easily become popular with his fellow passengers, who are usually in the proper mood to listen to his explanations of Utah and the Mormons.

After passing a mountain point, we obtained a broad view of Skull Valley, in which there are now only a few scattered ranches. The Hawaiian settlement Iosepa, which was founded with a view to make it a gathering place for the Hawaiian Saints, has long ago been abandoned.[13] The climate in Skull Valley was not suitable for the Polynesians, who had been used to the mild, continuous summer weather of the tropical islands of the Pacific.

In crossing the low mountain range west of Skull Valley, we look across the great salt desert towards the majestic mountain called Pilot Peak in Nevada.[14] We remember then the ill-fated Hastings company who crossed that desert in 1846. As we looked at Pilot Peak from the top of the ridge west of Skull Valley, that mountain seemed only a few miles away, though the real distance is about eighty miles. As these immigrants were from the east, they knew not that the clear sky, the thin air, and the desert itself were most deceiving to the eye of strangers out early one morning hoping to cross the desert in a few hours. They might have crossed it in two days had not a rain storm turned the hard, crusted desert surface into soft, sticky mud, which clung so tenaciously to the wagon wheels and the feet of men and horses that they could scarcely move at all. The consequence was that the emigrants had to leave many of their animals and wagons in the mud and be thankful to reach the western edge of the desert alive. But after the loss of so many animals, the company could travel only very slowly; and after reaching the Sierra Nevada Mountains, they were caught in terrific snowstorms, and nearly half of them perished before help could reach them from California. This is known in history as the Donner Party tragedy, Captain [George] Donner being leader of that part of the Hastings company.[15]

Traveling in up-to-date Pullman cars,[16] we experienced no hardship in crossing this desert. We soon reached Wendover, situated on the boundary line between Utah and Nevada. The main town is in Utah, but the Nevada part has a most unsavory reputation for bootlegging.[17] If the Nevada people engaged in that unlawful traffic find themselves in danger of being caught by the officers, they flee to Utah for protection.

Leaving Wendover, we traveled a long distance in sight of Pilot’s Peak, which is sometimes called the Fuji of Nevada,[18] as it in form somewhat resembles the “sacred mountain” of that name in Japan. Darkness overtook us as we crossed a high summit and descended into the historic Steptoe Valley.

Tuesday, January 23. Having traveled all night, we found ourselves early in the morning traveling down the picturesque Feather River Canyon, which is 116 miles long, and in that distance the train descends from an elevation of nearly five thousand feet to nearly sea level. In the upper end of the canyon, the mountains were covered with deep snow, while at the lower end, where Oroville is situated, the green fields and early spring verdure greet the eye and almost suggest the thought of having reached another world.

The frequent or continuous rain in the great Sacramento Valley has caused swollen streams everywhere. Many of the farms and meadows were seen partly covered with water, and as the rain still continued, everything seemed clammy and cold. We arrived safely at Sacramento at 1:00 p.m., where we were met by Mr. Harry Peterson, a California state official, and were conducted to a hotel. We found Sacramento, which now has a population of about eighty thousand inhabitants, a very busy city indeed. The state legislature is in session and all seemed bustle and hurry, notwithstanding the rain.

Soon after our arrival in Sacramento, I was busily engaged in research work in the magnificent state library and soon learned that certain historical information, which I expected to hunt for in San Francisco, could be obtained much more easily and more completely in Sacramento, where about three hundred thousand volumes of choice literature are safely and conveniently housed in the state capitol. The library occupies an entire wing of the great building from basement to garret, and there is a special collection of California literature in charge of Miss Eudora Garoutte, who rendered me all possible assistance in my work.[19]

Wednesday, January 24. I continued my labors in the state library in Sacramento. A special program and parade had been planned by a special committee in memory of the discovery of gold on the American River January 24, 1848, just seventy-five years ago today, but the rain interfered very much with the preparations and the carrying out of the details of the program. A few hundred people, however, gathered in front of the capitol and listened to a short speech by the governor of California [Friend W. Richardson], after which a small procession, headed by Harry A. Peterson, Esq., marched through some of the streets and put markers on several buildings of historical interest. In the procession there were a number of men (members of the Sacramento Whiskers Club),[20] women, and children dressed in the styles of 1848, or rather clothed as the miners and their families were garbed when gold was first discovered in California seventy-five years ago.

Both before and after leaving the capitol an old man, a mountaineer, personifying a pioneer fiddler of 1848, entertained the crowd by playing melodies of long ago. The children who participated in the parade and who were dressed to suit the occasion showed much enthusiasm and seemed to enjoy the occasion immensely. The so-called Whiskers Club (not Whiskey Club) incorporated under the laws of California was organized last year at the 1849 celebration for the purpose of perpetuating the history, romance, and memories of the historic days of 1849. The governor of the state, many of the state senators and representatives, congressmen, etc., are members of this club, which is the only organization of its kind in the whole world.

Today at 3:00 p.m. Elder Page and I boarded a local train and traveled sixty miles through a country abounding in vineyards and fertile fields to Placerville, Eldorado County, where we are stopping overnight.[21] Placerville, containing 2,500 inhabitants, is an old mining town situated in a hollow of the foothills near the base of the Sierra Nevada Mountains at an elevation of 1,830 feet above the level of the sea. In the evening we were invited by Leon Fairchild, a druggist of Placerville, to visit his father’s home, where a number of pet skunks are cared for like so many pet kittens. Mr. Fairchild understands how to tame these pretty, but generally detested, animals, and not only could he handle them in almost every conceivable way without “danger,” but he assured us that we, as strangers, could do the same. We accepted his invitation to do so with a degree of reluctance, and not until he had assured us that the pets were in good humor and well behaved did we allow them to crawl around our necks and otherwise receive our caresses. It is the first time I have handled a skunk, and it may perhaps be the last.

Mr. Fairchild told us of an amusing incident which happened in San Francisco quite recently when he was permitted to take his pets into a first-class San Francisco hotel where even dogs of every description were debarred from entry. Mr. Fairchild explained how the guests at the hotel at first sight of the skunks fled in all directions but how they soon returned one by one and found themselves on the very best of terms with the little striped creatures, who exhibited unusual affection for all, especially the ladies. Tomorrow morning we go to Coloma, the place where gold was first discovered January 24, 1848.

“Jenson’s Travels,” January 26, 1923[22]

Mormon Island, California

Thursday, January 25. Early in the morning, in company with Elder Page, I left Placerville (in the earlier days called Hangtown) and traveled about ten miles over a hilly and heavily timbered country in a northwesterly direction to Coloma, where gold was discovered January 24, 1848. The honor of discovery has been given to James W. Marshall, who acted as foreman for Mr. John A. Sutter in the erection of a sawmill in 1848, although members of the Mormon Battalion,[23] who worked under Mr. Marshall while digging a millrace, were in reality the ones who first turned up the red metal into their shovels. They, however, did not know that the reddish particles in the dirt which they handled was gold. But Mr. Marshall seemingly did, and when he took samples of the particles to Sutter’s Fort (on the present site of Sacramento) to have it analyzed, it was found to be gold, and thus he got the honor of being the discoverer.

A monument costing about $10,000 was erected in 1887 in memory of Mr. Marshall on the top of a hill rising to the height of about two hundred feet on the south side of the South Fork of the American River. The granite base of the monument is 30½ feet high, while the bronze statue of Marshall is 11½ feet in height. Considerable public money has been spent in improving the grounds immediately surrounding the monument and in constructing necessary roads. The name Marshall appears in large letters on the front of the monument, facing north. On the west side of the monument is the following inscription: “Erected by the State of California in memory of James W. Marshall, the discoverer of gold, born Oct. 8, 1810; died Aug. 10, 1885. The first nugget was found in the race of Sutter’s mill Jan. 24, 1848.”

The remains of Mr. Marshall lie buried under the monument. At the foot of the hill stands the original log cabin in which Mr. Marshall lived at the time gold was discovered, and close to the banks of the river two iron poles (about thirty-five feet high) have been erected on the very spot where the gold was first found. On the top of each of the poles is a square box painted white; these are visible for quite a distance.

Changed by Digging

Coloma is now an important village with a post office, a hotel, a small store, and a few private residences. In the day of the gold excitement, it was a large town, said to contain ten solid blocks of business houses. A modern steel bridge spans the river near the point where gold was first discovered. There is no trace of the millrace or site of the old sawmill left, as the surface of the lower grounds about Coloma have all been changed by miners who have been digging for gold.

In passing, I may say that James W. Marshall, the discoverer of gold, was a native of New Jersey and early in life learned the trade of a coach and wagon builder. He went to California in 1845 and engaged to work for General John A. Sutter. Marshall was a handyman around the fort. He made plows, wagons, and spinning wheels, besides doing general carpenter work, being a good mechanic. In 1847 General Sutter, who was in need of lumber for a contemplated flouring mill, sent Mr. Marshall off exploring the surrounding country for a suitable site for a sawmill. Presently he branched off on the South Fork of the American River and at length reached a place called by the Indians “Culloomah”[24] and afterwards, at the suggestion of Samuel Brannan,[25] named Coloma. Here he found an ideal mill site with abundant waterpower and inexhaustible supplies of timber on the hillsides. He reported back to General Sutter, and they formed a partnership. Then Marshall organized a company and returned to Coloma, where he commenced work on the sawmill August 28, 1847. After encountering many difficulties, the mill was at last completed, but it did not commence running until April 28, 1848.

On January 24, 1848, while Marshall was out, as usual, with his men at work (among whom were several members of the Mormon Battalion) gold was discovered. He later reported that he went down to the mill site that day as usual, and after shutting off the water from the tailrace, he stepped into it near the lower end, and there, on a rock about six inches beneath the surface of the water, he discovered particles of a red substance. Immediately the thought flashed across his mind that the particles might be gold. He gathered up a number of the largest, and going to the cabin of one of the workmen, Mr. Peter Wimmer, he asked for lye to test out his theory, for he thought if it was any other metal than gold the lye would affect it. Mrs. [Jennie] Wimmer informed him that she was making a kettle of soft soap and suggested that he throw the metal into the boiling liquid. This was done; and when, after a few minutes, the pieces of metal were taken out and appeared brighter than when they were put into the kettle, Marshall, who had previously paid some attention to minerals, concluded that he had indeed found gold. Four days after the discovery, on January 28, 1848, Marshall went to Sutter’s Fort, taking with him a few ounces of the gold, which he and General Sutter tested with nitric acid. This final test removed all doubts. Gold indeed had been found at Coloma.

At that time Sacramento, then called Sutter’s Fort (also New Helvetia, General Sutter being of Swiss descendants), was a mere village, and even San Francisco was but a small town. But after the discovery of gold had been heralded abroad, so many people arrived within two years after the discovery became known that California from a very sparsely settled country grew in population to such an extent that it could be admitted into the Union as a state September 9, 1850, on the same date that Utah was created a territory.

It should be remembered that of the many thousand gold diggers who helped swell the population of California a great number passed through Great Salt Lake City in 1849 and in 1850, on their way to the Pacific Coast, and that on account of this great rush to the gold fields a remarkable prophecy of the late Heber C. Kimball[26] was fulfilled to the effect that clothing and other things were sold in Great Salt Lake City at New York prices.[27] These gold-seeking immigrants who crossed the plains and mountains for the gold mines were both willing and anxious to exchange their dry goods, etc., for provisions and fresh animals in order to hasten on to their destination.[28]

We may here add that Mr. Marshall in his later days became addicted to drink and died a poor man.

For many years there had been some doubt in regard to the exact date on which gold was discovered at Coloma, and January 19, 1848, was for some time generally accepted as the date of discovery; but after consulting the private journals of Henry W. Bigler[29] and Azariah Smith[30] (both Mormon Battalion boys who kept daily journals) and other sources of information, it was decided that January 24, 1848, was the true date of discovery. The California legislature of 1917 empowered Governor William D. Stephens to appoint a committee “to determine the exact date of the discovery of gold” at Coloma (Sutter’s Mill). The committee, headed by Philip Baldwin Bekeart, investigated the matter thoroughly and proved positively that January 24, and not January 19, was the date of discovery.[31] Hence, the California legislature passed a resolution in 1919 approving the report of the committee and “decrees and recognizes January 24, 1848, as the date upon which gold was discovered in California by James W. Marshall.” The legislature further resolved “that the board of trustees of Sutter’s Fort is hereby authorized and directed to change the inscription upon the monument erected in memory of James W. Marshall at Coloma, El Dorado County, so that the correct date of the discovery of gold in California by James W. Marshall will appear thereon.”

In the History of Stanislaus County, by George H. Tinkham, published by the Historic Record Company in Los Angeles, California, 1920, the following paragraph occurs:

“James W. Marshall discovers gold. One of the commanders in the California department of the Mexican War was John C. Fremont,[32] and in his battalion was a soldier named James W. Marshall. He crossed the plains with his family in 1846, and soon after the close of the war, he traveled to Sutter’s Fort, looking for work. Captain Sutter gave him employment, as he was a good mechanic, and in December 1847 the captain sent Marshall into the mountains to find a good location for a sawmill. He found a good site at a point now known as Coloma, and the workmen began erecting the framework of the mill. In digging a millrace January 24, 1848, Marshall found some pieces of gold. The workmen, many of them Mormons, immediately left their work and began digging for the gold nuggets. The land on which the gold was found belonged to Captain Sutter, who had obtained the grant from [Manuel] Micheltorena, the Mexican governor.”[33]

With the Elders

After making the necessary investigation at Coloma and securing pictures and literature relative to the gold discovery, etc., Elder Page and I returned to Placerville, whence we traveled by stage (automobile) to Folsom, distant twenty-eight miles. Here we hired an automobile and traveled 3½ miles to Mormon Island,[34] where we made the needed observations, and then returned via Folsom (a town of 1,500 inhabitants) to Sacramento, where we visited with five of our elders from Zion who are laboring in the city of Sacramento and vicinity—namely, Thomas Brigham Smith,[35] of Santaquin, Utah (president of the Gridley Conference); Benjamin F. Zimmerman,[36] of Rexburg, Idaho; William Floyd Montgomery,[37] of North Ogden, Utah; William V. Denning,[38] of Idaho Falls, Idaho; and Forest L. Packard,[39] of Nampa, Idaho. From these elders we learned that there are upwards of two hundred Saints in the city of Sacramento and that regular meetings are being held; that a branch of the Church had been organized; and that the branch had a good choir, a fine Sunday School, a Relief Society, a young people’s association, etc. The elders occupy comfortable quarters in a building near the place of holding meetings.

The Sacramento Branch[40] is a part of the Gridley Conference.[41] This conference embraces that part of California, which extends from Stockton on the south to the state line on the north and from the Coast Range on the west to the state line (Nevada) east. It includes the branches in Sacramento, Yuba City (including Marysvale), Gridley, Liberty, and Grenada. There are, besides this, Sunday Schools in Stockton and Orland. The Sacramento Branch (including Stockton) has about four hundred members; meetings and Sunday School are held in Muddox Hall, corner of Thirty-Fifth Street and Fifth Avenue (3599 Fifth Avenue).[42] The elders’ headquarters are at 2980 Thirty-Sixth Street. Until December 1922, several branches in Nevada and others in California were also included in the Gridley Conference; but the branches in Nevada (formerly part of the Gridley Conference) were organized as the Nevada Conference[43] in December 1922; and the Fresno Conference[44] had been organized in January 1922. Eleven elders and four missionary sisters are at present laboring in the Gridley Conference; Sacramento is the conference headquarters.

We assisted the elders in holding a successful open-air meeting on a street corner in the central part of the city of Sacramento in the evening. Only a few people stopped to listen in the beginning, but as we proceeded, quite a crowd gathered and gave us a respectable hearing. Elders Thomas B. Smith, Andrew Jenson, and William V. Denning were the speakers. When we explained that there were Mormons in California one year before there were any in Utah, our audience became interested and after that listened attentively to a short historical recital of the Brooklyn company of Saints,[45] the Mormon Battalion, the settlement of San Bernardino,[46] etc.[47]

“Jenson’s Travels,” January 27, 1923[48]

Sacramento, California

Friday, January 26. Elder Page left Sacramento for San Francisco to arrange for our transportation to South America, while I was solicited to make another visit to Mormon Island in company with the following gentlemen, prominent citizens of Sacramento: Stanley J. Richard, president of the Sacramento Chamber of Commerce; Dr. James A. B. Scherer, a local historian and lecturer; Harry C. Peterson, assistant librarian of the state library; and Frank B. Durkee, reporter on the Sacramento Bee.[49]

We traveled by automobile to our destination, where we did considerable climbing on the hills bordering Mormon Island; took some photographs; and returned to Sacramento toward evening, where I stopped overnight with the LDS missionaries.

Mormon Island was a very noted spot at an early day when gold mining was booming on the American River and on other streams in California. The bar in the river called Mormon Island only contained a few acres and only suggested the name of the town that sprang up on the banks of the South Fork of the American River near the point where the North and South Forks of that historic river unite and become one stream, which about thirty miles below empties into the greater Sacramento River. The bar called Mormon Island was formed by the river dividing into two channels and flowing thus for a short distance, but these channels seemed to have been continually changing, as at the present time there is no island and as the water in the river all runs in one channel where there were formerly two. The town of Mormon Island is believed to have had between two thousand and three thousand inhabitants, living on both sides of the river. Now there is only a store and three or four private residences at, or near, the island. Mormon Island is about 1½ miles northeast of the Folsom Penitentiary,[50] where the worst criminals of California (most of them being called “third termers,” i.e., men who are serving their third term in state prison) are doing time. The town of Folsom, the nearest railroad point, is about 3½ miles southwest of Mormon Island, and the distance from Mormon Island by nearest road is about twenty-five miles.

The following concerning Mormon Island is culled from different authorities, of which one says:

“Mormon Island is the name given to a small island in the South Fork of the American River about halfway between Coloma, or the point in Coloma Valley where gold was first discovered in California on January 24, 1848, and Sutter’s Fort, at the junction of the American and Sacramento Rivers. Thus Mormon Island is about twenty-five miles west of Coloma and about the same distance east of Sutter’s Fort.”

Of this place Samuel Brannan wrote in the Calistoga Tribune of April 11, 1872:

Night of Discovery

“On January 19, 1848, when James W. Marshall let the water into the millrace and the water had run clear, he picked up a piece of gold—or rather what he supposed to be gold—at the bottom of the race. . . . A number of young men from the Mormon Battalion were at work on the mill for Marshall and Co. . . . Marshall, Weimer, Bennett, and Captain Sutter claimed the right to the discovery of gold and charged every man who worked there 10 percent of what they found. Some of the boys became dissatisfied and went prospecting down the river for themselves and found good digging about twenty-five miles below on an island which has ever since been known as Mormon Island. I put up a store there and called the place Natoma after the name of the Indians who lived there. I also put up a store at the mill and called the place Coloma after the name of the tribe there.”[51]

The historian Bancroft[52] in his history of California says:

“About February 21, 1848, Henry W. Bigler, one of the Mormons working on Sutter’s sawmill, wrote to certain of his comrades of the Mormon Battalion—Jesse Martin, Israel Evans, and Ephraim Green, who were at work on Sutter’s flour mill—informing them of the discovery of gold and charging them to keep it secret or to tell it to those only who could be trusted. The result was the arrival on the evening of the twenty-seventh of three men: Sidney Willis, Levi Fifield, and Wilford Hudson, who said they had come to search for gold. Marshall received them graciously enough and gave them permission to mine in the tailrace. Accordingly, next morning they all went there, and soon Hudson picked up a piece worth about six dollars. Thus encouraged, they continued their labors with fair success till March 2, when they felt obliged to return to the flour mill; for to all except Martin, their informant, they had intimated that their trip to the sawmill was merely to pay a visit and to shoot deer. Willis and Hudson followed the stream to continue the search for gold, and Fifield, accompanied by Bigler, pursued the easier route by the road. On meeting at the flour mill, Hudson expressed disgust at being able to show only a few fine particles, not more than half a dollar in value, which he and his companion had found at a bar opposite a little island about halfway down the river. Nevertheless, the disease worked its way into the blood of other Mormon boys, and Ephraim Green and Ira Willis, brother of Sidney Willis, urged the prospectors to return that together they might examine the place which had shown indications of gold. It was with difficulty that they prevailed upon them to do so. Willis and Hudson, however, finally consented; and the so lately slighted spot presently became famous as the rich Mormon Diggings, the island, Mormon Island, taking its name from these battalion boys who had first found gold there.”[53]

Details Confirmed

Henry W. Bigler confirms the above with details as follows:

“In the evening of Sunday, February 27, 1848, three of the boys from below arrived in our shanty, they having heard through a letter I had written to my messmates while in the battalion that we had found gold here at the sawmill. This letter had been written in a confidential way with the understanding that nothing should be said about it. As these men had been told of the discovery of a secret, they had now come up to see for themselves, and it happened that Mr. Marshall was in and sat till a late hour talking, he being in fine humor, as he mostly always was, and very entertaining. When about to leave for his own quarters on the hill a quarter of a mile away, one of the men (Mr. Hudson) asked the privilege of prospecting in the tailrace, which was readily granted, and the next morning (Monday, February 28) three men (Sidney Willis, Wilford Hudson, and Levi Fifield) went into the race. Soon afterwards, Hudson, with his butcher knife, dug out a nugget worth six dollars; they tarried with us a day or two, and as they returned, they prospected all along the creek and found a few particles of gold at the place which afterwards became known as Mormon Island. This eventually proved to be one of the richest finds in California.”[54]

“On July 4, 1849, at a meeting held at Mormon Island, W. C. Bigelow in the chair, and James Queen, secretary, resolutions were adopted declaring that in consequence of the failure of Congress to provide a government the separation of this country from the mother country has been loudly talked of, but those present at the meeting pledged themselves to discountenance every effort at separation or any movement that would tend to counteract the action of the general government of California. The meeting also resolved that, believing slavery to be injurious, they would do everything in their power to prevent its extension to their part of the country.”[55]

In the History of Sacramento County, published by Thompson and West, Oakland, California, 1880, the following article appears under the caption “Mormon Island”:

A Fine Prospect

“In the spring of 1848, two Mormons, one of whom was Wilford Hudson,[56] being on their way from Sutter’s Mill (now Coloma) found themselves near sunset at the spot now known as Willow Springs, in Sacramento County. Concluding to go no farther that night, they shot a deer and made their way to the nearest point of the South Fork of the American River, where they could procure water for themselves and their horses. They descended the bluff bank of the river to a flat covered with underbrush and then cooked and ate their supper. After this was accomplished, it being still light, one of the men remarked: ‘They are taking out gold above us on the river; let us see if we can find some at this place.’ They scraped off the topsoil, took a tin pan which they carried with them for cooking purposes, panned out some dirt, and attained a ‘fine prospect.’ Being satisfied that gold abounded in this vicinity, they went to the fort (Sutter’s Fort) the next day and communicated the news to Samuel Brannan, then of the firm of C. C. Smith & Co., proprietors of a small trading post where goods were bartered for hides, tallow, and wheat. Brannan at that time was spiritual guide and director of the Mormon population of New Helvetia (Sutter’s Fort) and other districts of California. He proceeded to the spot indicated by Hudson and his companion, set up a preemption claim, and demanded a royalty of 331/3 percent on all the gold taken out on the bar. So long as the Mormons were largely in the majority of those engaged in mining on the bar, this royalty was rigidly exacted. In course of time, however, unbelievers flocked into the mines and refused to pay tribute to the pretended owner of the land, who was compelled to give up the collection. In the meantime, however, Brannan had accumulated several thousand dollars, with which he formed partnerships with Mellus, Howard, & Co. of San Francisco, under the name of S. Brannan & Co., which laid the foundation of the large fortune acquired by him subsequently. This was the origin of Mormon Island. The extent of the village proper is now (1880) about eighty acres.

“As the news of the gold discoveries spread through the state, miners came flocking in from all quarters, till, in 1853, the town had a population of about 2,500 people, nine hundred of whom were voters.”[57]

The first hotel at Mormon Island, called the Blue Tent, was opened soon after the place became populated. Samuel Brannan opened the first store in 1848. He sold out to James Queen, one of Sacramento’s pioneers. J. P. Markham opened a hotel and store at Mormon Island in 1850.

Stage Line Established

A stage line to Mormon Island was established in 1850, one of the lines running from Sacramento to Coloma passing through Mormon Island, and the other from Sacramento to the island and return. These lines were undoubtedly running when George Q. Cannon[58] and others were called at the mines to go on missions to the Hawaiian Islands.[59] In 1856 a stage line was running from Folsom to Coloma, passing through Mormon Island; this line was still in operation in 1880. In 1849 about four hundred people were working on the Bar (Mormon Island). The only mining going on in the vicinity of Mormon Island in 1880 was at Richmond Hill, about one-half mile north of the village proper. In 1856 a fire destroyed the southwest portion of the village, which was never rebuilt. At one time there were four hotels, three dry goods stores, five general merchandise stores, two blacksmith shops, an express office, a carpenter shop, a butcher shop, a bakery, a livery stable, and seven saloons on Mormon Island. In 1880 the population had dropped to about twenty people. The decadence of Mormon Island began with the completion of the railroad to Folsom in 1856. A school was opened at Mormon Island in 1851, and the first schoolhouse was built in 1853. The only bridge in the township of Mormon Island is known as the Mormon Island Bridge. The first structure was built in 1851; this was a wooden bridge which was washed away in 1854. A wire suspension bridge was built soon afterwards; this was washed away by the flood of 1862 and was again rebuilt and still stood in 1880. Now a fine modern iron bridge spans the south branch of the American River on the site of the old bridges.

In perusing printed volumes and manuscripts in California libraries, I have found much historical data concerning Mormon Island and vicinity which no doubt will be woven into Church history at some future day.

“Jenson’s Travels,” January 27, 1923[60]

Stockton, San Joaquin County, California

I left Sacramento early in the morning and traveled by rail to Modesto, the county seat of Stanislaus County, California.

I took this journey in order to find the exact location of New Hope, the first Anglo-Saxon settlement in the great San Joaquin Valley, which now contains seven of the most flourishing settlements in California. This settlement was founded by a part of the Brooklyn company of Saints in 1846. On my arrival at Modesto, I called on the mayor of the city, Solomon P. Elias, Esq., who is one of the oldest settlers of Modesto now alive and a man very much interested in local history. He received me with courtesy but informed me that the site of New Hope was not in Stanislaus County, it being on the north side of the Stanislaus River, which forms the boundary line between Stanislaus and San Joaquin Counties. While in Modesto, which is a town of about fifteen thousand inhabitants, I visited with Elder Alfred E. H. Cardwell,[61] a former resident of the 27th Ward, Salt Lake City. He presides over the Modesto Branch,[62] which was organized January 7, 1923, and has already 115 members. This branch constitutes a part of the Fresno Conference of the California Mission.[63] Meetings and Sunday Schools are held regularly in the Seiots Hall, hired for the purpose, but the Saints are contemplating the erection of a chapel in the near future. Two elders from Zion are at present laboring as missionaries in Modesto and vicinity.

Failing to obtain the desired information concerning New Hope, I returned by rail to Stockton, the county seat of San Joaquin County, where I buried myself in the historical department of the public library and was successful in finding what I sought, at least in part. I was busy doing so until the steamer, on which I took passage to San Francisco, sailed.[64]

The following extracts are chosen from among a number of others which I have made from sundry publications.

Samuel Brannan, in writing from Yerba Buena (now San Francisco) on January 1, 1847, said:

“We have commenced a settlement on the River San Joaquin, a large and beautiful stream emptying into the Bay of San Francisco: but the families of the company are wintering in this place (Yerba Buena), where they find plenty of employment, and houses to live in; and about twenty of our number are up at the new settlement, which we call New Hope, ploughing and putting in wheat and other crops and making preparations to move their families up in the spring, where they hope to meet the main body of the Church by land some time during the coming season.”[65]

Site of New Hope

The site of New Hope was on the north bank of the Stanislaus, about a mile and a half from the San Joaquin. William Stout[66] was in charge of the party and went in a launch from Yerba Buena to found the first settlement in San Joaquin County. A log house was built and a sawmill; eighty acres of land were seeded and fenced, and in April 1847 the crops promised well, but not much more is known of the enterprise, except that it was abandoned in the autumn. Bancroft states that in April 1847 New Hope boasted ten or twelve colonists and several houses.[67]

The reason for abandoning the enterprise was the receipt of news that the Church had decided to settle in Salt Lake.

In Bancroft’s History of California the following is printed:

“Samuel Brannan went east to meet Brigham Young[68] and the main body, leaving New Helvetia (Sacramento) late in April, reaching Fort Hall[69] on June 9, and meeting the Saints (pioneers under President Brigham Young) at Green River about July 4 to come on with them to Great Salt Lake Valley. He was not pleased with the decision to remain there and found a city, and he soon started back, sorrowful, with the news. In Sierra he met the returning members of the Mormon Battalion on September 6, 1847, giving them a dreary picture of the chosen valley and predicting that President Young would change his mind and bring his people to California the next year.

“The members of the Brooklyn company were likewise disappointed to learn that the new home of their people was to be in the far interior. Some declined to leave the coast region, the rest, giving up their dreams of a great city at New Hope, devoted themselves half regretfully to preparations for a migration eastward.

“Nearly one hundred adults, with some forty children, found their way in different parties, chiefly in 1848–50, to Utah.”[70]

In the History of San Joaquin County, the settlement of New Hope is called Stanislaus City.

From an Old MS

William Glover,[71] one of the members of the Brooklyn company, states in his “Mormons in California” MS: “The company was broken up, and everyone went to work to make an outfit to go to the valley as best he could. The land, the oxen, the crop, the houses, tools, and launch all went into Brannan’s hands, and the company that did the work never got anything.”[72]

In An Illustrated History of San Joaquin County, published by the Lewis Publishing Company in 1890, the following occurs:

“There is one account very explicit as to the settlement of Mormons in Castoria Township in 1846. It is probably correct, although we do not find it elsewhere. It must be given as a part of this narrative. It says in substance: In the fall of 1846, the Mormons made an attempt at settlement. They came—some thirty of them—up the San Joaquin River in a schooner, landing on the east bank near where the Central Pacific Railroad (now Southern Pacific) crosses, and then went over the country to the north bank of the Stanislaus River to a point about 1½ miles from its mouth, where a location had been previously selected by Samuel Brannan, under whose orders the settlers were acting. The party, all of whom were well armed with rifles and revolvers, had come intending to stay. The first schooner that brought them—the first probably that ever ascended the San Joaquin River—was loaded with wheat, a wagon, and implements necessary to found a settlement and put in a crop. They soon completed a log house, covered with oak shingles made on the ground. They erected a Pulgas[73] redwood sawmill and sawed the boards from oak logs with which to lay the floor. As soon as the building was completed, they plowed the ground and sowed wheat, fencing it in. In this way, by the middle of January 1847, they had eighty acres sowed and enclosed. The fence was made by cutting down and cutting up oak trees, rolling the butt and large pieces into a line and covering them with limbs. The native Californians made their fences in this way. Then dissensions arose among them, and the leader, Stout, left the county. The author states that this was the first permanent settlement in the valley, as [Thomas] Lindsay’s house had been burned and he killed; but it can hardly be regarded as permanent from what follows. The account continues:

Wildlife Aplenty

“The valley was filled at this time with wild horses, elk, and antelope, which went in droves by thousands. Deer were very plentiful. The ground was covered with geese and the lakes and rivers with ducks, and the willow swamps along the riverbanks were filled with grizzly bears. The paths of the bears were as much worn and well defined as the paths of the horses and cattle. A bear’s path can never be mistaken; they travel with their legs apart, and in going over a road a thousand times they invariably step in the same place, so that a regular grizzly bear’s path is nothing but two parallel lines of holes worn in the ground. Bear oil took the place of lard in cooking. The only provisions sent for the colony were unground wheat, sugar, and coffee. All else had to be procured by the rifle. They had a mill with steel plates instead of burrs, driven with a crank by hand. The wheat was cut or ground up in this way, but not bolted; every man had to grind his own supply and do his own cooking. The winter of 1846–47 was very wet and stormy. In consequence of the rain, the river rose very rapidly—eight feet an hour on the perpendicular was marked. About the middle of January 1847, the river overflowed its banks and the whole country was under water for miles in every direction. The San Joaquin River was three miles wide opposite Corral Hollow. After digging their first meager crop of potatoes, which were mostly rotten, the enterprise was abandoned. Mr. Buckland,[74] who afterwards built Buckland House in San Francisco, was the last of the little colony to leave the place. [William H.] Fairchilds, afterwards county supervisor, moved him to Stockton in 1847.

The Gold Excitement

“The balance of the colony had gone to the lower country; but when the gold excitement broke out, they concentrated at what is known as Mormon Island and worked the mines, depositing their dust with Samuel Brannan, ‘in the name of the Lord’; and when they wanted their money it is said he told them he would be happy to honor their check signed by the Lord and until this was done he should keep the deposit secure.

“Subsequently in the early settlement of Stockton, a small company of Mormons settled near the bulkhead of Mormon Channel, and after them the channel was named. Somewhat corroborative of this account of the settlement of Castoria Township, it is known that in 1846 eighty acres of land were sown in that township, but there was no yield. . . .[75]

“In May 1851, Henry Grissim took up the land abandoned by the Mormons, not supposing he was ranching the lost site of Stanislaus City, the name given by the Mormons to their locality; he in turn sold to William H. Lyon, and Lyon sold to H. B. Underhill.

“Succeeding the trappers in 1845 came the Mormon settlement on the Stanislaus River (in 1846), their abandonment in 1847, the discovery of gold in January 1848, and the establishment of Doak and Bonsell’s Ferry in the fall of that year; and in August 1849 Colonel P. W. Noble and [Jonathan D.] Stevenson took possession of the old French campground. They kept a public house as well as a store. . . . These gentlemen were the first white men to occupy any portion of Castoria after the abandonment of the Mormons.”[76]

In the History of Stanislaus County, by George H. Tinckham, published by the Historic Record Company, in Los Angeles, California, in 1921, the following paragraph on New Hope appears: “Stanislaus City Founded—About thirty of the Mormons, under instructions from Samuel Brannan, sailed up the San Joaquin River in a little schooner and landed at a point near Mossdale, the Southern Pacific Railroad bridge. They brought with them in the vessel provisions sufficient to last for two years, a wagon, agricultural implements, and various kinds of seed.

An Irrigated Tract

“Traveling overland across San Joaquin County, they located on the north bank of the Stanislaus, about 1½ miles from its mouth. There they founded a city called by some Stanislaus City, by others New Hope. Setting up a small sawmill, they sawed out shingles and floor timbers from the large oak trees in the vicinity and built a log cabin. Then, enclosing about eighty acres of land with fence built of oak logs covered with brushwood, they planted the ground to wheat. The land was all sown in wheat by January 1847. They also raised a considerable variety of vegetables and irrigated the soil by means of ditches, drawing water from the river by the primitive method of a pole and bucket.

“‘They also sowed,’ said Carson, ‘a red top grass, the best the farmer can sow in the Tulare Valley, as it forms excellent pasture during the year and when cut equals the best red clover. It can now be seen where it has spread from the Stanislaus to French Camp above Stockton.’

“Their only provisions were whole wheat, coffee, and sugar. They had, however, a small hand mill, and any man, if he so desired, could grind his wheat to coarse flour. They also had plenty of ammunition and firearms, and there was plenty of game for the killing. Each man was compelled to do his own cooking.”

Samuel Brannan, in writing to a friend on January 1847, said: “‘We have commenced a settlement on the Stanislaus River, a large and beautiful stream emptying into the Bay of San Francisco.’ His settlement, however, did not long continue. Some say the Mormons were there only one year, others three or four years. Their manager was a man named Thomas Stout,[77] who was disliked by all the party. Quarreling with him one day the colony later voted to leave the place. One of the last Mormons to leave the locality was a man named Buckland, who later built the Buckland House in San Francisco.”[78]

It stands to reason that our California historians have made mistakes in their narratives, but they are in the main correct. We have material at the Church Historian’s Office which will adjust all differences.

“Jenson’s Travels,” January 28, 1923[79]

San Francisco, California

Sunday, January 28. Having spent the night on the bay sailing from Stockton to San Francisco, I arrived at the latter city early in the morning, where I found Elder Isaac E. Riddle,[80] president of the San Francisco Conference[81] of the California Mission; Elder Alonzo L. Hanson[82] and other elders; and also two missionary sisters.

In company with Elder Hanson, I crossed the bay to Oakland, where I attended Sunday School and afterwards visited Elder Elbert D. Thomas[83] and family from Salt Lake City, at Berkeley. There are about one thousand Latter-day Saints in Oakland and vicinity, and in the spring a fine chapel, or church, which has cost about $38,000, will be dedicated in Oakland.[84] Elder William A. McDonald,[85] late of Arizona, presides over the Oakland Branch,[86] which is a growing and lively organization. Many of the Saints at Oakland and vicinity hail from Utah and Idaho, and among the brethren there are a number of mechanics who have come to California to seek employment. I returned to San Francisco in the afternoon and, together with Elder Richard R. Lyman,[87] who was visiting California in the interest of Boy Scout work, I preached at the Saints’ hall on Hayes Street in the evening.[88] We had a good and well-attended meeting. There are at present about six hundred Saints in San Francisco and vicinity, and half a dozen elders from Zion and two missionary sisters are at present endeavoring to promulgate the principles of the gospel in the metropolis of Northern California.

Ever since the arrival of the ship Brooklyn in San Francisco Bay July 11, 1846, there have been Latter-day Saints in California, and there never were as many Saints in San Francisco and Oakland and vicinity as there are at the present time.[89] As in Oakland, many of the members of the Church in San Francisco were formerly residents of Utah, Idaho, and other intermountain states.

Perusing Records

Monday, January 29. I attended to business in San Francisco pertaining to our contemplated trip to Central and South America and also spent some time perusing records regarding the activities of the Latter-day Saints in California in early days. In the evening I attended a meeting of the priesthood of the San Francisco Branch,[90] over which a local elder (Brother Storey)[91] acts as president.

While the Latter-day Saints do not seek for the applause of the world, it is nevertheless pleasing to us to hear honorable men of the earth speak well of our people when they mean what they say, and we deserve their praise; and as the Latter-day Saints were privileged to take a most prominent part in introducing Anglo-Saxon civilization in California, we are grateful to certain California historians who have endeavored to do us justice.

In the history of San Francisco by John P. Young, published in San Francisco in 1912, it is stated that Yerba Buena had 200 people in the midsummer of 1846, indifferently accommodated in forty to fifty houses. A year later the town, which then had become San Francisco, had 459 residents; of this number, 375 were whites, most of whom were Latter-day Saints who had just arrived from the eastern states in the ship Brooklyn under the leadership of Samuel Brannan. The remainder was Sandwich Islanders, Indians, and Negroes. Of the whites, 268 were adults. The 107 children were made up of 51 under five years of age, 32 who were between five and ten, and 24 between fifteen and twenty. Of Indians there were 34, and they, like the 10 Negroes, were chiefly in domestic service. The 40 Sandwich Islanders were almost all sailors, Captain [William] Richardson and the few others engaged in transportation finding them the only material available for that purpose. The larger part of the addition during the first year of American occupation was made up of whites born in the United States. There were 228 who called themselves Americans, 38 Californians, 2 from the Mexican departments, 5 Canadians, 2 Chileans, 22 Englishmen, 3 Frenchmen, 27 Germans, 14 Irish, 14 Scotch, 6 Swiss, 4 born at sea; and Peru, Poland, Russia, Sweden, the West Indies, Denmark, New Holland, and New Zealand had one representative each.[92]

A Vast Solitude

In a work entitled The Beginnings of San Francisco, by Zoeth Skinner Eldredge, published in 1912 in San Francisco, the following is to be found: “In the year 1835, the Bay of San Francisco was a vast solitude through whose bordering groves ranged the red deer, the elk, and the antelope, while bears and panthers and other ferocious beasts frequented the hills and often descended upon the scattered farmyards. The five mission establishments in its vicinity did not contain above two hundred white inhabitants, while the few ranches were of great extent and widely separated. Boats manned by Indians came down the creeks from the missions with their loads of hides and tallow for the ships anchored in Yerba Buena Cove. The growth of the little settlement was slow, and in 1844 it contained only a dozen houses and not over fifty permanent inhabitants.

“In 1839, Governor Alvarado ordered a survey of Yerba Buena, and the alcalde,[93] Francisco de Haro, employed Jean Jacques Vioget, a Swiss sailor and surveyor, to do the work, which was completed in the fall of that year. Vioget’s survey laid out the blocks between Pacific, California, Montgomery, and Dupont Streets and shows Dupont Street intersected at Clay by the Calle de la Fundacion, which branched off to the northwest towards the ‘Puerto suelo.’ Montgomery Street is interrupted at Clay Street by a lagoon that occupied portions of the two Montgomery Street blocks between Clay and Pacific Streets. On the south, Montgomery Street was again interrupted by a freshwater pond (Laguna Dulce) at the foot of Sacramento Street, which was supplied by a stream that ran down Sacramento Street from above Powell. No names were given to the streets, and the cross streets were 2½ degrees from a right angle. Down to 1846, lots were granted by Vioget’s map, and lots previously granted were made to conform to it. No street improvements were attempted, the line of streets being merely indicated by buildings and fences.”[94]

The foregoing describes Yerba Buena before the arrival of the Brooklyn. Mr. Eldredge continued his narrative as follows:

Project Abandoned

“On July 31, 1846, the ship Brooklyn arrived from New York, with about two hundred Mormons in charge of elder Samuel Brannan. They had sailed from New York February 4, and June 20 they were at Honolulu, where they met Commodore [Robert F.] Stockton, about to sail for Monterey. Surmising that California would soon be occupied by the United States and not knowing what they might find there, Brannan bought in Honolulu 150 stands of arms and drilled the men of his company on the way over. He had announced to Brigham Young before sailing that he would select the most suitable site on the Bay of San Francisco for the location of a commercial city, but finding the United States in possession, the project was abandoned.

“The landing of the Mormons more than doubled the population of Yerba Buena. They camped for a time on the beach and on the vacant lots, and then some went to the Marin forests[95] to work as lumbermen; some were housed in the old mission buildings and others in Richardson’s “Casa Grande” (big house) on Dupont Street. They were an honest and industrious people, and all sought work wherever they could find it. [. . .] The Fourth of July 1847 was celebrated in San Francisco with appropriate ceremonies. [. . .] The population of the town had increased over 100 percent during the twelve months following the American occupation, and the opinion was expressed that San Francisco was destined to be the New York of the Pacific. The California Star estimated the population in June 1847 at 449, exclusive of the New York volunteers, and the number of buildings was 187, half of which had been erected during the past four months. Before the gold excitement had begun to depopulate the town in May and June 1848, the number of inhabitants had increased to about 850 and that of buildings to two hundred. [. . .]

“The first newspaper in California appeared in Monterey August 15, 1846, edited by Walter Colton and Robert Semple and called the Californian. A portion of its contents was printed in Spanish. The printing apparatus was an old press and type belonging to the Mexican government at Monterey, which had not been in use for several years so that the type had to be scoured and rules and leads made from tin plates. The paper was the Spanish foolscap used for official correspondence. It appeared every Saturday until May 1847, when it was transferred to San Francisco and later merged in the California Star.[96] Sam Brannan, Mormon chief and elder, a printer by trade, had published for several years in New York a Church organ called the Prophet.[97] He brought with him on to the Brooklyn the press and outfit of his paper, and on January 9, 1847, he published in San Francisco, then called Yerba Buena, the first number of the weekly California Star,[98] with Elbert P. Jones as temporary editor, succeeded later by Edward C. Kemble. It was a sheet of 8½ x 12 inches of print. The paper was temporarily suspended during the gold excitement in the summer of 1848, but from November of that year, the publication was regular. It had been slightly enlarged in January 1848, when publication was resumed, but in November of that year, Kemble bought out the Californian (formerly published in Monterey) and consolidated it with his own paper under the name of the California Star and Californian. In January 1849, the name was changed to the Alta California, with Edward Gilbert as editor, and Kemble proprietor. The Alta California became a great daily and was published continuously until June 2, 1891, when it was suspended. Kemble came with Brannan on the Brooklyn, though he was not a Mormon. He took an active part in the politics of the town and was connected with the paper until he went east in 1855.

Educational Matters

“Soon after the American occupation, educational matters began to engage the attention of the people. The California Star of January 16, 1847, urged the importance of establishing a school for the children of the rapidly growing town and offered to contribute a lot and fifty dollars in money towards the erection of a schoolhouse. In April 1847, J. D. Marston opened a private school in a shanty on the west side of Dupont Street between Broadway and Pacific. This was the first school in San Francisco and was attended by some twenty or thirty children. It lasted but a few months. At a meeting of the council September 24, 1847, Leidesdorff,[99] William Glover (Latter-day Saint and member of the Brooklyn company), and William S. Clark[100] were appointed a committee to attend to the building of a schoolhouse. The building was erected on the western side of the plaza, and on April 3, 1848, the school was opened under Thomas Douglas, a graduate of Yale College. The school prospered until the gold excitement carried teacher and trustees to the mines. From the date of its completion in December 1847, the schoolhouse served the purpose of town hall, courthouse, people’s court for trial of culprits by the first vigilance committee, school, church, and, finally, jail. Owing to the range and variety of its uses, the building was dignified by the name of Public Institute. [. . .] From the second Sunday after their arrival at San Francisco (Yerba Buena), the Mormons held religious services in Captain Richardson’s “Casa Grande” on Dupont Street,[101] where Sam Brannan exhorted the Saints to remain faithful in this land of Gentiles, but some twenty of them ‘went astray after strange gods,’ as did their eminent leader[102] a few years later.”[103]

“Jenson’s Travels,” January 30, 1923[104]

San Francisco, California

Tuesday, January 30. I spent most of the day at the public library in San Francisco,[105] looking up historical data concerning the ship Brooklyn, the Mormon Battalion, etc., and was quite satisfied with my day’s work. The following items represent a small part of the information obtained:

In the Monterey Californian (the first newspaper published in California) of Saturday, August 15, 1846, the following appears:

“The Brooklyn with 170 Mormon immigrants on board arrived at San Francisco on the third instant in thirty days from Honolulu. These immigrants are a plain, industrious people; most of them are mechanics and farmers.”[106]

Three weeks later the editor had become better posted as to the number of immigrants. Hence, in the Californian of September 5, 1846, under the heading “Marine Intelligence,” the following was published: “Arrivals—July 31 (1846) American ship Brooklyn 230 passengers from New York via Sandwich Islands, landed passengers and freight, and sailed for Bodega, and will touch at Monterey.”

The Reverend Walter Colton, USN [United States Navy], who navigated in the United States frigate Congress (Commodore Stockton, commander), wrote in a book entitled Deck and Port (published in New York in 1856), “The Congress touched at Honolulu in January 1846.” Under date of Sunday, June 25, 1846, Mr. Colton writes: “We left at Honolulu the American ship Brooklyn with 175 (230) Mormon immigrants on board bound for Monterey and San Francisco, where they propose to settle. They look to us for protection and expect to land if necessary, under our batteries. I spent the greater part of a day among them and must say I was much pleased with their deportment. The greater portion of them are young, and have been trained to habits of industry, frugality, and enterprise. Some have been recently married and are accompanied by their parents. They are mostly from the Methodist and Baptist persuasions. Their Mormonism, so far as they have any, has been superinduced on their previous faith, as Millerism[107] on the belief of some Christians. They are rigidly strict in their domestic morals, have their morning and evening prayers; and the wind and the weather have never suspended, during their long voyage, their exercises of devotion.”[108]

Under date of June 27, 1846, the Reverend Mr. Colton journalized as follows: “We have at last a slant of wind which has put us on our course. The Mormon ship must make haste if she expects to overtake us before we reach Monterey. It is a little singular that, with a company of 170 (230) immigrants confined in a vessel of only four hundred tons depending on each other’s activity and forbearance for comfort, unbroken harmony should have prevailed. They have had their momentary jars, but I was assured by the captain, who is not of their persuasion, that no serious discord has occurred. They put their money into a joint stock, laid in their own provisions, and have everything in common. They chartered their vessel, for which they pay twelve hundred dollars per month. It will cost them for their passage alone some ten thousand dollars before they disembark in California.”[109]

Yerba Buena

William Antonio Richardson—an Englishman by birth, who as a young man of twenty-two had reached Alta, California, in 1822 as mate of a British ship, which he deserted—was appointed by the noted Jose Tigueron (governor and one of the greatest men in the history of Alta, California) as captain of the port of San Francisco. Richardson went there in 1835 and put up the first building (a rude structure on the beach) on the present site of San Francisco—other than those at the less conveniently located presidio and mission. Around this house as a nucleus, a settlement called Yerba Buena sprang up, where the shipping and business interests of the bay region centered, eventually to become the principal district of the city of San Francisco. (A History of California, by Charles E. Chapman, published in New York, 1921.)[110]

In 1836, Jacob P. Leese built a comfortable frame house near Richardson’s. As time went on, Leese added a store and made the place something of a trading center for ships taking on wood and water across the bay at Sausalito. In 1841, however, Leese sold his property to the Hudson’s Bay Company,[111] which thereafter for four or five years became the chief factor in the commercial life of the little village. Yerba Buena was seized by the Americans July 8, 1846.[112] The Brooklyn arrived July 31, 1846. In the spring of 1847, the name of Yerba Buena was changed to San Francisco.

With the American occupation, Yerba Buena rapidly began to increase its scant population, and by the spring of 1848, it could boast nearly nine hundred inhabitants. (Robert Glass Cleland’s A History of California.)[113]

In the History of California by Theodore H. Hittell, the following paragraph appears: “On July 31, 1846, there was a large and unexpected accession to the population (of California). A strange vessel was reported coming in through the Golden Gate;[114] and for a while there was much excitement and agitation in reference to it on board the Portsmouth, then lying in the harbor, as well as in the village. It was observed, however, that the stranger was not a warship and that it flew the American flag. As it drew nearer, it could be seen that its deck was crowded with men, women, and children. In a short time the mystery was explained. The ship proved to be the Brooklyn, and the passengers were a colony of 238 Mormon immigrants. They had left New York in February under the direction of the leaders of their church. [. . .] The men were as a class industrious and steady, good mechanics and good farmers and well supplied with implements and tools for making a new settlement. Their leader was Samuel Brannan. He was a native of Maine, born in 1819, had been a printer by trade, and was of a speculative mind. In 1842 he joined the Mormons and published a newspaper devoted to the interests of the sect in New York. In the winter of 1845–46, he took hold energetically of the project of founding a Mormon colony on the Bay of San Francisco, and the result was the chartering, freighting, and sailing of the ship Brooklyn, a vessel of 370 tons, which had been fitted up for the purpose of carrying the immigrants. It was well provided with everything that was deemed necessary for the proposed colony; and, among other things, Brannan brought along a printing press, type, paper, ink, and compositors. The Mormons landed at Yerba Buena, pitched their tents on the sand hills around the village, and in a short time built a number of houses and shops. Brannan himself set up his press in September and did job printing work. In October he announced the publication of a weekly newspaper and issued an extra in advance of it, containing General [Zachary] Taylor’s official report of the battles of Palo Alto and Resaco de la Palma. On January 9, 1847, appeared the first regular issue of the newspaper itself, which was called the California Star. In the meanwhile the failure of the primary object of the colony in establishing a settlement exclusively Mormon, and the new and promising career opened in Brannan’s speculative mind by the aspect of affairs in California, led to disagreements, and these disagreements finally led to irreconcilable quarrels.

“In 1848, after the discovery of gold and while the Saints in California were very successfully engaged in laying up earthly treasures, if not heavenly ones, at Mormon Island, Brannan assumed the right as high priest of the Church to exact the payment of tithes and in this manner collected a large amount of money. There was much dissatisfaction with his proceedings on the part of some, who were perhaps not entirely orthodox or who rather had not entire faith in Brannan, and, among others, on the part of William S. Clark, a prominent San Franciscan, from whom Clark’s Point derived its name. In July 1848, when Governor Mason visited the mines and stopped on his way at Mormon Island, Clark, in the course of conversation, inquired, ‘Governor, what business has Sam Brannan to collect tithes here?’ Mason answered, ‘Brannan has a perfect right to collect the tax, if you Mormons are fools enough to pay it.’ ‘Then,’ said Clark, ‘I, for one, won’t pay it any longer.’ From that time the payment of tithes ceased; but Brannan had already collected enough to lay the foundation of a large fortune.[115] He was not disposed to recognize the claims of the Church as owner of this wealth and the result was a lawsuit, the high priest’s apostasy, and the breaking up and dissolution of the Mormon association of which he was the head.”[116]

While the statements in the foregoing are perhaps somewhat overdrawn, they are in the main correct.[117]

“Jenson’s Travels,” February 1, 1923[118]

On board the steamship Colombia, Pacific Ocean

Wednesday, January 31. At 1:00 p.m. we sailed from San Francisco as passengers on board the steamship Colombia[119] on our way to South America. The day was one of sunshine and fine weather, and after passing out through the Golden Gate we soon found ourselves on the broad face of the Pacific Ocean and sailing southward along the hilly or mountainous coast of California. About 10:00 p.m. the lights of Monterey, the old capital of California, were visible from our ship.

Before leaving San Francisco, I obtained additional information concerning matters associated with the history of the Latter-day Saints in California. The following is selected:

In the History of California by Theodore H. Hittell (published in San Francisco in 1898), the following paragraph appears.

“Captain [Francis J.] Lippitt (commanding American soldiers in California) [. . .] seemed unable to restrain his soldiers, and their conduct became so disorderly that it was feared the people would rise and put a violent stop to their excesses. [. . .] The conduct of these soldiers compared very disadvantageously with that of the Mormon Battalion, which had followed [Stephen W.] Kearny across the continent and during the past year had been stationed at and in the neighborhood of San Diego. Their term of office expired on July 16, 1847, a few days previous to which they were marched up to Los Angeles to be honorably discharged.

“Notwithstanding the prejudices felt against them on account of their religious professions and notwithstanding Stevenson, who was in command at Los Angeles, imagined them to be engaged in a diabolical conspiracy to get military control of California—which notion he communicated in a private and confidential letter—Mason (the governor of California) spoke of them in terms of high praise.[120] He said that for patience, subordination, and general good conduct they were an exemplary body of men. They had religiously respected the rights and feelings of the conquered Californians, and not one syllable of complaint had ever reached his ears of a single insult offered or outrage done by a Mormon volunteer. So high an opinion in fact did he entertain of the battalion in general and of their especial fitness for the duties of garrisoning the country that he made strenuous efforts to engage their services for another year. But the great mass of them desired to meet their brother and sister Saints on the shore of the Great Salt Lake; and only one company would consent to remain in service.”[121]

In order to show what the Californians think of Samuel Brannan, the following sketch of his life may prove interesting reading:

The Brooklyn Company

“Samuel Brannan, Mormon elder and chief of the ship Brooklyn company, was born in Saco, Maine, March 2, 1819. In 1833, he moved to Ohio, where he learned the trade of a printer, and for five years from 1837 visited most of the states of the Union as a journeyman printer. In 1842, he joined the Mormons and for several years published the New-York Messenger—later the Prophet, organs of the Mormon Church.[122] Of the Mormon scheme to colonize California Brannan was an integral part, and he had charge of the New York end of it. In pursuance of the plan, Brannan chartered the ship Brooklyn, 370 tons, and sailed from New York February 4, 1846, for San Francisco, with 238 men, women, and children, the first installment of the Mormon colony. He brought his printing press, types, and a stock of paper; flour mill, machinery, plows, and other agricultural implements; and a great variety of articles such as would be useful in a new country. At Honolulu, where the ship arrived in July (June), Samuel Brannan purchased 150 stands of arms to provide for the probable chance of war between the United States and Mexico. On July 31 the Brooklyn arrived at San Francisco (Yerba Buena), and the passengers immediately landed and squatted among the sand hills on the beach. They were anxious to work and were ready to accept any that was offered; glad to make themselves useful—the women as well as the men—and a party of twenty was sent into the San Joaquin Valley to prepare for the great body of the Saints that were coming overland.

“On January 7, 1847, Brannan brought out the first number of the California Star, edited by Dr. E. P. Jones, the second newspaper published in California, the first being the Californian, published by Walter Colton and Dr. Robert Semple, in Monterey.

A Leading Man

“Samuel Brannan preached on Sundays and during the week engaged in all sorts of business and political activities and was from the first a leading man in San Francisco. As a preacher he was fluent, terse, and vigorous, and he conducted the first Protestant service held in San Francisco, August 16, 1846, in Richardson’s casa grande (big house) on Dupont Street.

“In the spring of 1847, Brannan went east to meet Brigham Young and the main body of the Mormon migration. He met them in the Green River Valley and came on with them to Salt Lake. He was much displeased with their decision to remain and found a city in the Salt Lake Valley, and he returned to California.

“In 1847, Brannan established a store at Sutter’s Fort, or New Helvetia, and furnished on Sutter’s account the supplies for Marshall, Weimer, and Bennett, the men who were putting up the mill for Sutter on the South Fork (of the American River); and after the discovery of gold, he put up a store at the mill, which he named Coloma, after the Indians who lived there, and also one at Mormon Island, which he named Natoma, after the name of the tribe there. A large number of Mormons were engaged in mining on the American River, and Brannan insisted on their paying over to him, as head of the Mormon Church in California, the 10 percent claimed by the Church. [. . .]

“Through his mining operations at Mormon Island; the enormous profit of his stores at Sacramento, Natoma, and Coloma; and the increase in value of his real estate in San Francisco, Brannan became the richest man in California. There was scarcely an enterprise of moment in which he did not figure, and he was as famous for his charity and open-handed liberality as he was for his enterprise. He was straightforward in his dealing and had the respect and confidence of the business community. Mingling in California with men of affairs, of education and refinement, he abandoned the Mormon religion. In ridding San Francisco of the thieves, gamblers, and desperadoes that infested it, none was more active, outspoken, and fearless than Brannan, and he lashed the malefactors and their official supporters with a vigor of vituperations that has rarely been equaled.

Later Reverses

“In company with Peter F. Burnett and Joseph W. Winans, he established in 1863 the first chartered commercial bank in California, the Pacific Accumulation and Loan Society, the name being afterwards changed to Pacific Bank. His later years were marred by the habit of drink to which he gave himself up and which greatly affected his excellent business faculty. Unlucky speculations made inroads upon his fortune, and his vast wealth melted away. He was divorced from his wife, whom he had married in 1844 and who came with him on the Brooklyn. About 1880 he obtained a grant of land in Sonora in return for help rendered the Mexican government during the French invasion,[123] and thither he removed and embarked on a large colonization scheme; but his old-time energy was gone. He died in Escondido, Mexico, May 5, 1889.”[124]

Notes

[1] Jenson, “Jenson’s Travels,” Deseret News, February 3, 1923, 12.

[2] Andrew Jenson (1850–1941), a Danish-American member of the Church, immigrated to Utah in 1866 and served the first of five missions to his native Denmark, 1873–75. See Jenson, Autobiography, 66–86.

[3] Jenson, later known as the “most traveled man in the Church,” sailed for South America at age seventy-two, nineteen years before his death in November 1941. See “Andrew Jenson Returns from 30,000 Mile Trip,” Salt Lake Telegram, August 14, 1935, 16.

[4] The Deseret News was the first newspaper published in the Territory of Utah, with its first issue printed in June 1850. As an official organ of the Church, the News included Latter-day Saint–related stories, messages, and reports as well as other local and national news. At times the Deseret News was a weekly (1850–89) and a semiweekly (1889–1922), but by the time Jenson left for South America, the newspaper was a daily. See Holley, Utah’s Newspapers, 11–15.

[5] See Jude 1:3: “Beloved, when I gave all diligence to write unto you of the common salvation, it was needful for me to write unto you, and exhort you that ye should earnestly contend for the faith which was once delivered unto the saints.”

[6] Jenson worked as a part-time employee with the Historian’s Office in Salt Lake City, 1886–97. He later served as assistant Church historian, 1897–1941. See Jenson, Autobiography, 140, 389. See also Bitton and Arrington, Mormons and Their Historians, 41–54.

[7] Jenson traveled around the world on two occasions, once on a special mission for the Historian’s Office (1895–97) and again on his way home from presiding over the Scandinavian Mission (1912–13). See Neilson and Moffat, Tales from the World Tour. For an account of Jenson’s 1912–13 journey through Europe, Russia, and Japan, then back to Salt Lake City, see Jenson, Autobiography, 495–511.

[8] Possibly referring to 2 Timothy 3:15: “And that from a child thou hast known the holy scriptures, which are able to make thee wise unto salvation through faith which is in Christ Jesus.”

[9] In 1882 Jenson moved from the southern part of Salt Lake Valley to a two-story home a few blocks north of Temple Square, within the boundaries of the Salt Lake 17th Ward. There he built a secured vault with custom shelving for his large personal library and study. See Jenson, Autobiography, 228.