"How We Got the Book of Moses"

Kent P. Jackson

Kent P. Jackson, “How We Got the Book of Moses,” in By Study and by Faith: Selections from the Religious Educator, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009).

Kent P. Jackson is a professor of ancient scripture at BYU.

The book of Moses is an extract from Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible. It was revealed to the Prophet in 1830 and in early 1831, beginning not long after the organization of the Church. This article is a brief introduction to the origin of the book of Moses and the Bible translation from which it derives.

Beginning in June 1830, Joseph Smith began a careful reading of the Bible to revise and make corrections in accordance with the inspiration he would receive. The result was the revelation of many important truths and the restoration of many of the “precious things” that Nephi had foretold would be taken from the Bible (see 1 Nephi 13:23–29). In a process that took about three years, the Prophet made changes, additions, and corrections as were given him by divine inspiration while he filled his calling to provide a more correct translation for the Church. [1] Today the Prophet’s corrected text is usually called the Joseph Smith Translation (JST), but Joseph Smith and his contemporaries referred to it as the New Translation. [2] The title Inspired Version refers only to the edited, printed edition, published in Independence, Missouri, by the Community of Christ (formerly the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints). The book of Moses in the Pearl of Great Price is the very beginning of the New Translation, corresponding to Genesis 1:1–6:13 in the Bible.

The Translation

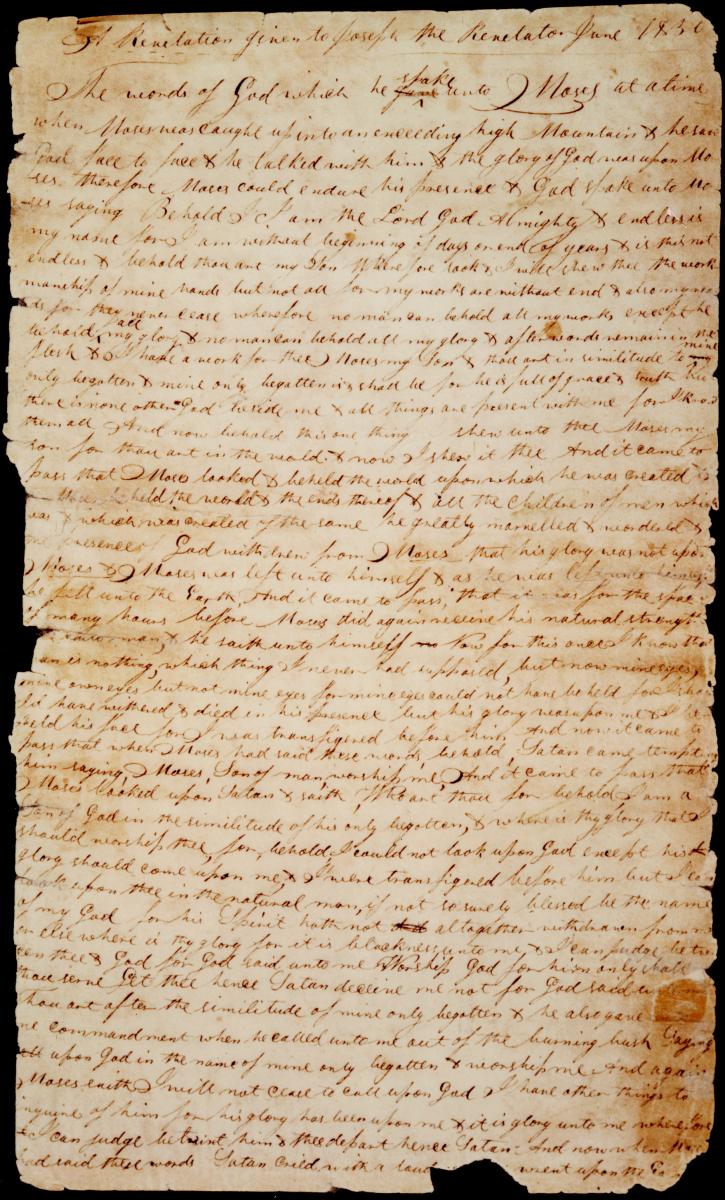

The first revelation of the JST was what we now have as Moses 1. It is the preface to the book of Genesis. It begins the earliest manuscript of the New Translation, designated Old Testament Manuscript 1 (OT1). [3] Serving as scribes for what is now in the book of Moses were:

|

Oliver Cowdery |

Moses 1:1–5:43 |

Beginning June 1830 |

|

John Whitmer |

Moses 5:43–6:18 |

October 21, November 30, 1830 |

|

Emma Smith |

Moses 6:19–52 |

December 1, 1830 |

|

John Whitmer |

Moses 6:52–7:1 |

December 1830 |

|

Sidney Rigdon |

Moses 7:2–8:30 |

December 1830, February 1831 |

Dictating the text of the New Translation to these scribes, the Prophet progressed to Genesis 24:41, when he set aside Genesis to begin translating the New Testament as he was instructed by the Lord on March 7, 1831 (see D&C 45:60–62). He and his scribes worked on the New Testament until it was finished in July 1832, when they returned to work on the Old Testament. [4]

A second Old Testament manuscript, designated Old Testament Manuscript 2 (OT2), started as a copy of the first manuscript (OT1). John Whitmer had made the copy in March 1831 while Joseph Smith was working on the New Testament with Sidney Rigdon. After OT2 was started, it became the manuscript of the continuing translation through the rest of the Old Testament. The earlier manuscript (OT1) remained essentially unused, as a backup copy. The translation of the Old Testament began anew in July 1832 and continued for about a year. At the end of the Old Testament manuscript, after the book of Malachi, the following words are written in large letters: “Finished on the 2d day of July 1833” (OT2, p. 119). That same day the Prophet wrote to Church members in Missouri and told them, “We this day finished the translating of the Scriptures for which we returned gratitude to our heavenly father.” [5]

Moses 1:1–19, on Old Testament Manuscript 1, page 1, “A Revelation given to Joseph the Revelator.” This is the beginning of Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible. Dated June 1830, in Oliver Cowdery’s handwriting. Courtesy of Library-Archives, Community of Christ, Independence, Missouri.

During the course of the Prophet’s work with the Bible, changes were made in about thirteen hundred Old Testament verses and in about twenty-one hundred verses in the New Testament. [6] Most of the changes are rewordings of the existing King James Version. But other changes involve the addition of new material—in some cases substantial amounts. Presumably, every book in the Bible was examined, but no changes were made in fifteen of them (Ruth, Ezra, Esther, Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon, Lamentations, Obadiah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Malachi, 2 John, and 3 John). The books with no corrections are identified on the manuscripts with brief notations like “Micah—Correct” (OT2, p. 118). Ecclesiastes is the only book not mentioned at all. Regarding another book, the manuscript notes, “The Songs of Solomon are not Inspired writings” (OT2, p. 97).

Most passages in the New Translation were revealed in clarity the first time and show little need for later refining. But some passages show that the Prophet struggled with the wording until he was satisfied it was acceptable to the Lord. His careful effort was in harmony with the instruction he had received previously that we should “study it out in [our] mind” as we listen to the Spirit and apply our best efforts, after which a confirmation will come if it is correct (see D&C 9:7–9).

On many of the manuscript pages, there are revisions that were made some months after the original dictation, when the Prophet went through parts of the Bible again to add words to the text or revise existing wording. [7] Some of these changes simply correct errors in the original recording, such as when his eyes skipped words while he was dictating or when his scribe recorded words incorrectly. But some insertions revise the writing or add words or phrases to produce new meanings not recorded in the original dictation. Many important revisions were made to the book of Moses in this process. Joseph Smith called this second pass through the text the “reviewing.” He finished the reviewing of the New Testament in February 1833, and he probably finished all, or virtually all, of his work on the text of the Old Testament that summer. [8]

Was the translation finished? The best answer is yes, but this requires some explanation. The Bible, even in its purest and fullest form, never contained the complete records of those who are mentioned in it. The book of Genesis, for example, was a revelation to Moses that provided mere summaries of important lives and events. Certainly there are other truths from ancient times that could have been revealed in the New Translation and other additions that could have been inserted to make it more complete. But from July 1833 on, the contemporary sources show that Joseph Smith considered it finished. He no longer spoke of translating the Bible but of printing it, [9] which he wanted and intended to accomplish “as soon as possible.” [10] He sought to find the means to publish it as a book, and he and other Church leaders encouraged the Saints to donate money for the project. Excerpts were printed in the Church’s newspapers and elsewhere, so some sections of it were available for the early Saints. [11] But because of poverty, continuing persecutions and relocations, and the other priorities of members of the Church, when the Prophet was martyred in 1844, he had not seen the realization of his desire to have the entire New Translation appear in print.

In the decades after Joseph Smith’s death, Latter-day Saints in Utah lacked access to the manuscripts of the New Translation and had only limited knowledge about how it was produced. None of the participants in the translation process were with the Church when the Saints moved west in 1846. [12] This and related circumstances resulted in many misconceptions about it that eventually made their way into our culture. Among those misconceptions are the beliefs that the Prophet did not finish the translation and that it was not intended to be published. Careful research by BYU professor Robert J. Matthews shows that these ideas are refuted in Joseph Smith’s own words. [13] But was the New Translation ready to go to the printer the day Joseph Smith died? The manuscripts show that after the translation was completed, much work was done to get it ready for printing. Joseph Smith or his assistants went through the text and inserted punctuation and verse breaks and corrected the capitalization. By today’s standards, we might say that more work was needed to make the punctuation and spelling more consistent, and a few of the Prophet’s changes to the text had resulted in uneven wording that had not yet been smoothed out. But the translation was finished, and there is every indication that the Prophet believed that the text was ready to go to press. Perhaps he felt that any remaining refinements would be worked out during the typesetting and proofing.

Types of Changes

Joseph Smith had the authority to make changes in the Bible as God directed. In one revelation, he is called “a seer, a revelator, a translator” (D&C 107:92), and in several other Doctrine and Covenants passages, his work with the translation is endorsed by the Lord (see D&C 35:20; 43:12–13; 73:3–4; 90:13; 93:53; 94:10). The Prophet called his Bible revision a “translation,” though it did not involve creating a new rendering from Hebrew or Greek manuscripts. He never claimed to have consulted any text other than his English Bible for the translation, but he “translated” it in the sense of conveying it in a new form.

It appears that several different kinds of changes were involved in the process, but it is difficult to know with certainty the nature or origin of any particular change. I propose the following categories of revisions:

- Restoration of original text. Because Nephi tells us that “many plain and precious things” would be “taken away” from the Bible (1 Nephi 13:28), we can be certain that the JST includes the restoration of content that was once in original manuscripts. To Moses, the Lord foretold the removal of material from his record and its restoration in the latter days: “Thou shalt write the things which I shall speak. And in a day when the children of men shall esteem my words as naught and take many of them from the book which thou shalt write, behold, I will raise up another like unto thee; and they shall be had again among the children of men—among as many as shall believe” (Moses 1:40–41). Joseph Smith was the man like Moses whom the Lord raised up to restore lost material from the writings of Moses, as well as lost material from the words of other Bible writers. But Joseph Smith did not restore the very words of lost texts because they were in Hebrew or Greek (or other ancient languages) and because the New Translation was to be in English. Thus, his translation, in the English idiom of his own day, would restore the meaning and the message of original passages but not necessarily the words and the literary trappings that accompanied them when they were first put to writing. This is why the work can be called a “translation.” Parts of the book of Moses—including Moses’s vision in chapter 1 and Enoch’s visions in chapters 6 and 7—have no counterparts in the Bible. It is likely that those passages are restoration of material that was once in ancient manuscripts.

- Restoration of what was once said or done but was never in the Bible. Joseph Smith stated, “From what we can draw from the scriptures relative to the teachings of heaven we are induced to think, that much instruction has been given to man since the beginning which we have not.” [14] Perhaps the New Translation includes teachings or events in the ministries of prophets, apostles, or Jesus Himself that were never recorded anciently. It may include material of which the biblical writers were unaware, which they chose not to include, or which they neglected to include (see 3 Nephi 23:6–13).

- Editing to make the Bible more understandable for modern readers. Many of the individual New Translation changes fall into this category. There are numerous instances in which the Prophet rearranged word order to make a text read more easily or modernized its language. Examples of modernization of language include the many changes from wot to know, [15] from an to a before words that begin with h, from saith to said, from that and which to who, and from ye and thee to you. [16] In many instances, Joseph Smith added short expansions to make the text less ambiguous. For example, there are several places where the word he is replaced by a personal name, thus making the meaning more clear, as in Genesis 14:20 (KJV “And he gave” = JST “And Abram gave”), and in Genesis 18:32 (KJV “And he said. . . . And he said” = JST “And Abraham said. . . . And the Lord said”).

- Editing to bring biblical wording into harmony with truth found in other revelations or elsewhere in the Bible. Joseph Smith said, “[There are] many things in the Bible which do not, as they now stand, accord with the revelation of the Holy Ghost to me.” [17] Where there were inaccuracies in the Bible, regardless of their source, it was well within the scope of the Prophet’s calling to change what needed to be changed. Where modern revelation had given a clearer view of a doctrine preserved less adequately in the Bible, it was appropriate for Joseph Smith to add a correction—whether or not that correction reflects what was on ancient manuscripts. The Prophet also had authority to make changes when a passage was inconsistent with information elsewhere in the Bible itself. Perhaps the following example will illustrate this kind of correction: The Gospel of John records the statement, “No man hath seen God at any time” (John 1:18), which contradicts the experience of Joseph Smith (Joseph Smith—History 1:17–20) as well as several examples in the Bible itself of prophets seeing God (e.g., Exodus 24:9–11; 33:11; Numbers 12:6–8; Isaiah 6:1; Amos 9:1). The JST change at John 1:18 clarifies the text and makes it consistent with what we know from other revealed sources.

Later History

When Joseph Smith died, the manuscripts of the New Translation were not in the possession of the Church but of his family, who remained in Illinois when the leaders of the Church and the majority of the Saints moved to the West. In 1867, the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints published the New Translation under the title The Holy Scriptures, Translated and Corrected by the Spirit of Revelation, By Joseph Smith, Jr., the Seer. The name Inspired Version, by which it is commonly known, was added in an edition of 1936, but it is not inappropriate to refer to it by that name since its first publication in 1867. The RLDS publication committee undertook substantial editing for punctuation and spelling. [18]

In 1851, Elder Franklin D. Richards of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles was serving as president of the British mission in Liverpool. Sensing a need to make available for the British Saints some of Joseph Smith’s revelations that had been published already in America, he compiled a mission pamphlet entitled The Pearl of Great Price. [19] His intent was that his “little collection of precious truths” would “increase [the Saints’] ability to maintain and to defend the holy faith.” [20] In it he included, among other important texts, excerpts from the Prophet’s New Translation of the Bible that had been published already in Church periodicals and elsewhere: the first five and one-half chapters of Genesis and Matthew 24. Elder Richards did not have access to the original manuscripts of the New Translation, and the RLDS Inspired Version had not yet been published. For the Genesis chapters, he took the text primarily from excerpts that had been published in Church newspapers in the 1830s and 1840s. But those excerpts had come from OT1 and did not include Joseph Smith’s final revisions that were recorded on OT2. The Genesis material was in two sections: “Extracts from the Prophecy of Enoch . . .” (Moses 6:43–7:69) and “The Words of God, which He Spake unto Moses . . .” (Moses 1:1–5:16, 19–40; 8:13–30). [21]

In the late 1870s, the decision was made to prepare the Pearl of Great Price for Churchwide distribution at Church headquarters in Salt Lake City. Elder Orson Pratt of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles was assigned to prepare the edition, which was published in 1878. Knowing that Joseph Smith had made later corrections to the New Translation, Elder Pratt drew the Genesis chapters not from the original Liverpool Pearl of Great Price but from the printed RLDS Inspired Version, which he copied exactly for the book of Moses. Again, the material was in two sections, this time called “Visions of Moses” (Moses 1) and “Writings of Moses” (Moses 2–8).

The Genesis text in the 1867 Inspired Version, though more accurate than the Liverpool version of 1851, was not always consistent with Joseph Smith’s intentions. The RLDS publication committee apparently did not understand the relationship between OT1 and OT2 and excluded a significant number of the Prophet’s corrections from the Inspired Version. As a result, our book of Moses today still lacks important corrections that were made by Joseph Smith. [22]

In the October 1880 general conference, the new Pearl of Great Price was presented to the assembled membership for a sustaining vote and was canonized as scripture and accepted as binding on the Church. Since then, the Pearl of Great Price has been one of the standard works, and the few chapters of the Joseph Smith Translation in it (the book of Moses and Joseph Smith—Matthew) have been recognized not only as divine revelation—which they always were—but also as integral parts of our scripture and doctrine.

Later editions of the Pearl of Great Price made changes to the Genesis material to make the book of Moses as it is today. The 1902 edition was the first to use the name “The Book of Moses,” and it was the first to add chapters, verses, and cross-reference footnotes. Revisions were made in the text, but the Church did not have the original manuscripts to guide the process. The 1921 edition was the first to be printed in double-column pages. The current name, “Selections from the Book of Moses,” was added in the edition of 1981. This name acknowledges that the Pearl of Great Price does not contain all of Moses’s record.

Because the Saints in Utah knew little about the Joseph Smith Translation and did not have access to its original manuscripts, for many years the translation was not widely used within the Church, except for the excerpts that are part of the Pearl of Great Price. During the 1960s and 1970s, Professor Robert Matthews conducted exhaustive research on the manuscripts. [23] His study confirmed the general integrity of the printed Inspired Version and taught us many things about the New Translation and how it was produced. [24] In the process, Professor Matthews brought the JST to the attention of members of the Church. [25]

In 1979, when the Church published a Latter-day Saint edition of the Bible in the English language, it included generous amounts of material from the New Translation in footnotes and in an appendix. In subsequent years, JST excerpts were included in the “Guide to the Scriptures,” a combination concordance–Bible dictionary published with the LDS scriptures in languages other than English. And in 2004, the Religious Studies Center at Brigham Young University published a typographic transcription of all the original manuscript pages, complete with original spelling, cross-outs, and insertions. [26] A significant aspect of these publications is the fact that they have made the JST accessible to an extent that it never had been before. Now General Authorities, curriculum writers, scholars, and students can draw freely from it in their research and writing, bringing the JST to its rightful place alongside the other great revelations of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Latter-day Saints know that Joseph Smith was appointed by God to provide a corrected translation of the Bible (see D&C 76:15). God endorsed it in strong language: “And the scriptures shall be given, even as they are in mine own bosom, to the salvation of mine own elect” (D&C 35:20). The New Translation is, as Elder Dallin H. Oaks of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles observed, “a member of the royal family of scripture” that “should be noticed and honored on any occasion when it is present.” [27]

Notes

[1] See Scott H. Faulring, Kent P. Jackson, and Robert J. Matthews, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004); Kent P. Jackson, The Book of Moses and the Joseph Smith Translation Manuscripts (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005). In 1975 Robert J. Matthews published “A Plainer Translation”: Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible—A History and Commentary (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1975). These newer studies have clarified many matters discussed in Matthews’s book, including scribal identifications, dates, and the process of the Prophet’s work.

[2] See Doctrine and Covenants 124:89; Times and Seasons 1, no. 9 (July 1840): 140; Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957), 1:341, 365; 4:164.

[3] The original JST manuscripts are located in the Library-Archives of the Community of Christ in Independence, Missouri. Note that in Matthews’s “A Plainer Translation” and other early publications, an old archival numbering system was used for the manuscripts, resulting from an early misunderstanding of the order in which the manuscripts were written. OT1 was previously designated OT2, and OT2 was previously designated OT3. Matthews was the first to question the accuracy of the numbering system (see Matthews, “A Plainer Translation,” 67–72; Richard P. Howard, Restoration Scriptures: A Study of Their Textual Development, rev. and enl. [Independence, MO: Herald, 1995], 63n1).

[4] In a letter dated July 31, 1832, the Prophet stated, “We have finished the translation of the New Testament . . . , we are making rapid strides in the old book [Old Testament] and in the strength of God we can do all things according to his will” (Joseph Smith to W. W. Phelps, July 31, 1832, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library, Salt Lake City; published in Dean C. Jessee, ed., The Personal Writings of Joseph Smith, rev. ed. [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2002], 274).

[5] Sidney Rigdon, Joseph Smith, and Frederick G. Williams to the Brethren in Zion, July 2, 1833, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library; published in Joseph Smith, History of the Church, 1:368.

[6] Matthews, “A Plainer Translation,” 425.

[7] Some of these insertions required more room than was available between the lines of the text and were written on small pieces of paper and attached in place with straight pins—the nineteenth-century equivalent of paper clips or staples.

[8] “This day completed the translation and the reviewing of the New Testament” (Kirtland High Council Minute Book, February 2, 1833, 8, Church History Library; published in Joseph Smith, History of the Church, 1:324).

[9] The evidence is collected in Matthews, “Joseph Smith’s Efforts to Publish His Bible Translation,” Ensign, January 1983, 57–64; see also Matthews, “A Plainer Translation,” 40–48, 52–53.

[10] “You will see by these revelations that we have to print the new translation here at Kirtland for which we will prepare as soon as possible” (Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, and Frederick G. Williams to Edward Partridge, August 6, 1833, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library).

[11] The Evening and the Morning Star 1, no. 3 (August 1832): 2–3 (Moses 7); 1, no. 10 (March 1833): 1 (Moses 6:43–68); 1, no. 11 (April 1833): 1 (Moses 5:1–16); 1, no. 11 (April 1833): 1–2 (Moses 8:13–30); Doctrine and Covenants of the Church of the Latter Day Saints (Kirtland, OH: F. G. Williams and Co., 1835), “Lecture First,” 5 (Heb. 11:1); “Lecture Second,” 13–18 (Moses 2:26–29; 3:15–17, 19–20; 4:14–19, 22–25; 5:1, 4–9, 19–23, 32–40 ); Times and Seasons 4, no. 5 (16 January 1843): 71–73 (Moses 1); Peter Crawley, A Descriptive Bibliography of the Mormon Church, Volume One, 1830–1847 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1997), 60–61 (Matthew 24).

[12] Joseph Smith (died 1844), Oliver Cowdery (excommunicated 1838), John Whitmer (excommunicated 1838), Emma Smith (did not go west), Sidney Rigdon (excommunicated 1844), Jesse Gause (excommunicated 1832), and Frederick G. Williams (excommunicated 1839, died 1842).

[13] See Matthews, “Joseph Smith’s Efforts.”

[14] The Evening and the Morning Star 2, no. 18 (March 1834): 143.

[15] The manuscript at Exodus 32:1 revises wot to know with a note that know “should be in the place of ‘wot’ in all places.”

[16] These changes are not universally consistent in the manuscripts.

[17] Joseph Smith, The Words of Joseph Smith: The Contemporary Accounts of the Nauvoo Discourses of the Prophet Joseph, comp. and ed. Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1980), 211; spelling and capitalization modernized.

[18] See Jackson, Book of Moses, 20–33.

[19] The Pearl of Great Price: Being a Choice Selection from the Revelations, Translations, and Narrations of Joseph Smith, First Prophet, Seer, and Revelator to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Liverpool: F. D. Richards, 1851).

[20] Preface, 1851 Pearl of Great Price, page [v].

[21] See Jackson, Book of Moses, 18–20.

[22] Some of these are noted in Matthews, “A Plainer Translation,” 145–61. For a full discussion, see Jackson, Book of Moses, 20–36.

[23] Robert J. Matthews, “A Study of the Doctrinal Significance of Certain Textual Changes Made by the Prophet Joseph Smith in the Four Gospels of the Inspired Version of the New Testament” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1960), and “A Study of the Text of the Inspired Revision of the Bible” (PhD dissertation, Brigham Young University, 1968). “A Plainer Translation” was published in 1975.

[24] See Matthews, “A Plainer Translation,” 141–61.

[25] See Thomas E. Sherry, “Changing Attitudes Toward Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible,” in Plain and Precious Truths Restored: The Doctrinal and Historical Significance of the Joseph Smith Translation, ed. Robert L. Millet and Robert J. Matthews (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1995), 187–226.

[26] Faulring, Jackson, and Matthews, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts.

[27] Dallin H. Oaks, “Scripture Reading, Revelation, and Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible,” in Millet and Matthews, eds., Plain and Precious Truths Restored, 13.