The Council of Fifty and the Perils of Democratic Governance

Benjamin E. Park

Benjamin E. Park, “The Council of Fifty and the Perils of Democratic Governance,” in The Council of Fifty: What the Records Reveal about Mormon History, ed. Matthew J. Grow and R. Eric Smith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 43-54.

Benjamin E. Park is an assistant professor of history at Sam Houston State University. His first book, American Nationalisms: Imagining Union in an Age of Revolutions, is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press in 2018.

The winter of 1843–44 had been exceptionally cold in the Mormon city of Nauvoo, Illinois, and the following spring was especially rainy. The downpour was so strong on April 14 that Joseph Smith, prophet and president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, canceled Sunday meetings. Yet despite the gloomy weather, many Mormons’ hopes were buoyed by the formation of a new secretive political organization that they believed was destined to rule the world.

Joseph Smith and several dozen of his closest male followers gathered together twice on April 18 in the month-old Council of Fifty, once at 9:00 a.m. and again at 2:00 p.m. During the morning session, they discussed a new document that would take precedence over the American Constitution, which Mormons believed the United States government had abandoned. “We, the people of the Kingdom of God,” started the document, which was a mix of traditional republican language with theocratic principles. Though the new constitution was incomplete and required further revision, the delegates enthusiastically praised its general ideas. In the afternoon session, they debated its implications. Throughout, attendees were ecstatic. One participant, Ezra Thayer, remarked that “this [was] the greatest day of his life.” William Clayton, the secretary of the council, noted in his journal that “it seems like heaven began on earth and the power of God is with us.” The physical setting was wet and dreary, yet the theoretical future seemed anything but.

While part of a seemingly radical fringe response to a particular set of circumstances, the Council of Fifty embodied central American tensions concerning constitutionalism, democratic governance, and the separation between church and state. Understanding the council’s relationship to these broader themes is significant in reconstructing not only the turbulent Mormon settlement of Nauvoo but also the dynamic environment of antebellum America. This essay will focus explicitly on the intersections of religious, secular, and constitutional sovereignty and how these intersections were rooted in a culture in which all three spheres seemed to converge. To do so, it will focus on a single day of debates, April 18, 1844, and trace the cultural genealogies found within those discussions. How did the Council of Fifty’s radical solutions speak to the problems of democratic governance? The answers promise to add nuance to conventional understanding of America’s democratic tradition.

The Kingdom of God and the Church of God

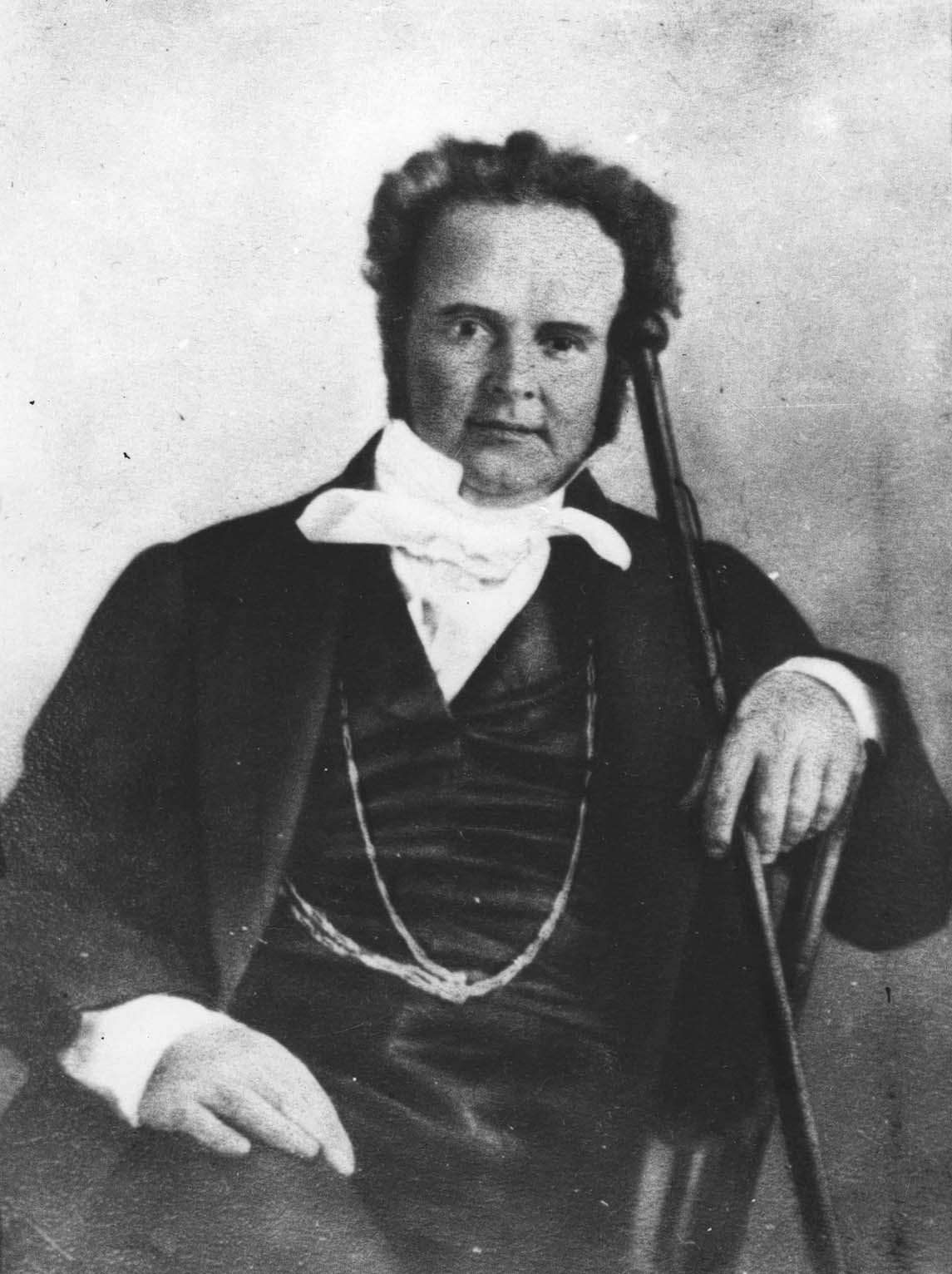

Willard Richards served as recorder of the Council of Fifty during the Nauvoo era. Copy of a photograph, circa 1845, likely by Lucian R. Foster. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Willard Richards served as recorder of the Council of Fifty during the Nauvoo era. Copy of a photograph, circa 1845, likely by Lucian R. Foster. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

The afternoon after the Council of Fifty received the first draft of its constitution, Apostle Willard Richards posed two important questions to his fellow council members. One dealt with religious and secular authority, and the other dealt with constitutional evolution. Was there a difference, he asked, between “the kingdom of God and the church of God”? In other words, is there a separation between church and state? While such a question had an immediate and parochial context (would the ecclesiastical and civic structures in Nauvoo overlap?) it also held much broader implications. And reflecting the complex issue, the question prompted a number of divergent, and discursive, responses, and the numerous opinions exemplified the disagreements even within the Church. The second question was even more nuanced. “Will the ‘kingdom of God’ become perfected as the legitimate results of the operation of the constitution now to be adopted,” he asked, “or will it be perfected through the alterations of the constitution which may take place hereafter to suit the situation of the earth and kingdom?” Put another way, are the founding documents binding as scripture—a position modern theorists define as originalism—or will governing principles evolve as leaders, generations, and circumstances develop? Few in the council seemed to grasp the significance of this latter question, and discussion soon spiraled out of control. But as we tease out the meanings and contexts of his questions, it becomes apparent that Richards was an acute observer of the democratic dilemma.[2]

Born in Massachusetts and trained in Thomsonian medicine, Richards converted to the Mormon faith in 1836 and became an apostle in 1840. Joseph Smith quickly recognized his able mind and steady hand. Richards was appointed as Joseph Smith’s scribe in 1841 and then as Church historian and recorder the following year. He was therefore a natural choice for the Council of Fifty’s recorder in 1844. Though William Clayton kept the council’s minutes, Richards was a constant presence, mediating voice, and reliable expositor. His questions on April 18, along with his other remarks throughout the council’s minutes, reveal him to be a keen observer of key issues. In many ways, his questions were more poignant than even he could have understood at the time.

Separation of Church and State

Richards’s first question, on the difference between the “kingdom” and the “church” of God, reflected how far American society had come in the half century since disestablishment. Those who framed the United States’ founding documents inaugurated a then-radical idea of religious liberty—in which there was a strict separation between political and ecclesiastical governance—over the more traditional practice of religious toleration, in which one religious institution would retain preference over others (even if all faiths received some form of liberty). States were slower to adapt to these new policies. Richards’s own Massachusetts, for instance, passed a constitution that argued that because “the happiness of a people and the good order and preservation of civil government essentially depend upon piety, religion, and morality,” the legislature had the right to establish a state-funded religion “for the support and maintenance of public Protestant teachers of piety, religion, and morality in all cases where such provisions shall not be made voluntarily.” Citizens could worship whatever religion they wished, but the state remained committed to the perpetuation of one particular church. Full disestablishment did not reach Massachusetts until 1833, only three years before Richards encountered Mormon missionaries. When Mormon leaders published a statement on government in 1835, it reflected this new understanding: “We do not believe it just to mingle religious influence with civil Government,” it declared. That Richards wondered in 1844 whether there was a separation between church and state—when the two institutions were clearly led by the same “prophet, priest, and king”—demonstrated how deep these cultural roots had taken.[3]

But there were still many who wondered if America’s disestablishment had gone too far. When the Constitution was being debated, a number of critics pointed to its failure to mention God, the Bible, or religion in general. Evangelicals in the South and Congregationalists in the Northeast insisted that political rights were based on religious principles and that to ignore the role of religion in society risked inviting God’s wrath and inaugurating anarchy. During the antebellum period, antislavery and suffragist activists accused America’s political system of forgetting its religious past. Women’s rights activist Angelina Grimké, for instance, argued that the rules dictated by “the government of God” should take precedence over federal policies that “subjected [women] to the despotic control of man.” Abolitionist Theodore Parker similarly argued that American laws must recognize the “absolute Right” dictated by “a moral Law of God,” which should serve as the basis for all laws and legislation. Many believed America’s morals had become unmoored from the anchor of divine oversight.[4]

The Mormon constitution sought to solve the problem. “None of the nations, kingdoms or governments of the earth do acknowledge the creator of the Universe as their Priest, Lawgiver, King and Sovereign,” its preface declared, “neither have they sought unto him for laws by which to govern themselves.” The constitution’s first article reaffirmed God’s supremacy, the second proclaimed the authority of the prophet and priesthood, and the third validated priestly judgment. There was no question where sovereignty should reside. George A. Smith “compared the situation of the world,” which did not recognize God’s true authority, “to an old ship without a rudder on the midst of the sea.” Revelation and divine authority provided the necessary guidance, and the members of the council were willing “to throw out our cable and try to bring the old ship to land.” The nautical metaphor emphasized the Council of Fifty’s role in providing a saving grace for the rest of the nations. Secular democracy had brought only unrest and war, and only a divine theocracy could reintroduce stability and peace.[5]

Participants in the council that afternoon were divided over what that precisely meant, however, as Richards’s inquiry regarding whether there was a difference between “the kingdom of God and the church of God” sparked a lively debate. Reynolds Cahoon could “not see any difference between them,” but Amasa Lyman disagreed. “The church has only jurisdiction over its members,” Lyman explained, “but the kingdom of God has jurisdiction over all the world.” Erastus Snow split the difference by explaining, “They are distinct, one from the other, and yet all identified in one.” Clearly, the boundaries were porous and contested. Council members tried to balance their allegiance to prophetic rule and democratic principles. At least four argued there was not a difference between the two entities, and just as many offered countering rejoinders. As much as they tried to reconcile the two spheres, however, their attempts were strained. Exacerbated with the discussion over Joseph Smith’s concurrent roles, David Yearsley asked, “How can a man be elected president when he is already proclaimed king[?]” It was a good question.[6]

Joseph Smith emphasized the distinction between the Church and the Council of Fifty. This portrait is believed to be by David Rogers, based on the work of Sutcliffe Maudsley. Courtesy of Church History Museum, Salt Lake City.

Joseph Smith emphasized the distinction between the Church and the Council of Fifty. This portrait is believed to be by David Rogers, based on the work of Sutcliffe Maudsley. Courtesy of Church History Museum, Salt Lake City.

Joseph Smith, for his part, emphasized there was “a distinction between the Church of God and kingdom of God.” The political kingdom had authority only in this world and did not play a role in the hereafter. “The church,” on the other hand, “is a spiritual matter and a spiritual kingdom.” To Joseph Smith, there was a separation between the spiritual and political spheres. A church functioned within the parameters protected by the government, and the temporal “kingdom” would eventually fade away in the Millennium. Further, even though he had earlier been received by the council as a “prophet, priest, and king,” Smith downplayed the monarchical language and connotations. “It is not wisdom to use the term ‘king,’” he urged. He personally preferred the ambiguous term “theodemocracy,” a neologism that captured the blended purposes of theocratic authority and democratic participation. A “theodemocracy,” explained Smith in an earlier council meeting, was when “the people . . . get the voice of God and then acknowledge it, and see it executed.” The popular American maxim Vox populi vox Dei should not mean the common translation of “the voice of the people is the voice of God” but rather “the voice of the people assenting to the voice of God.” To many outsiders, these would be distinctions without a difference. For Smith and his followers, however, even while the intersections between the Church, the kingdom, and the American government were never fully fleshed out, the resulting ambiguity enabled a space for creative innovation and theorizing.[7]

The Nature of Constitutions

But while they debated the first of Richards’s questions on April 18, members of the Council of Fifty failed to address his second query: “Will the ‘kingdom of God’ become perfected as the legitimate results of the operation of the constitution now to be adopted, or will it be perfected through the alterations of the constitution which may take place hereafter to suit the situation of the earth and kingdom?” Was this new constitution pristine in its original form, or will it have to be adapted as the kingdom, and society, advances? This seemingly abstract and theoretical question regarding originalism reflected a much broader American anxiety: What happens when founding documents fail to definitively answer pressing questions? In an era when the entire nation debated how to address the slave issue—what many saw as the “original sin” of the Constitution—theories concerning origins, alterations, and advancements were abundant.[8]

The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries witnessed an intellectual revolution regarding social evolution. Rather than staid institutions frozen in place, nations and governments were now understood to be organic and malleable structures that transformed with time and culture. The American Revolution inaugurated a new age in which the living had the right, even the obligation, to reform the works of the dead. “No society can make a perpetual constitution, or even a perpetual law,” declared Thomas Jefferson. “The earth belongs always to the living generation.” Jefferson’s belief concerning the permanence of government—he argued that “every constitution, and every law, naturally expires at the end of 19 years”—may have been extreme, but it was the product of a cultural environment no longer tethered to traditional forms of authority. In a world in which everything seemed in flux, it made sense to forgo installing permanent shackles.[9]

This anxiety only grew during the antebellum period, as antislavery theorists like William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips argued that existing governing mechanisms, even if they were enshrined in constitutional law, were not set in stone. When faced with the dilemma of America’s founding document being defined as a slaveholding compact, Garrison responded by “branding [the Constitution] a covenant with death, and an agreement with hell” and then burning it before an eager abolitionist audience. Representing a more moderate perspective, Abraham Lincoln argued that founding documents contained the “natural rights” owed to all men but that the governing texts must be amended to better secure those rights. Adapting the Constitution to natural rights was the work of the present. In all corners, the legal foundations upon which Americans placed political authority appeared in transition. Willard Richards’s question regarding originalism, then, tapped into a larger ideological debate.[10]

Even if Richards’s query went unanswered on April 18, it did not remain so for long. A week later, Smith recorded a revelation declaring that the entire council was “my constitution, and I am your God, and ye are my spokesmen.” A document could never supplant an authoritative body of chosen men. Divine law was so fluid, and human society so malleable, that constant deliberation was required. This was a culmination of nearly two decades’ worth of ecclesiastical development within the Church, as councils were given increasing authority and attention. To Smith, varying contexts and circumstances necessitated holy men who could appropriate ideas and practices as situations required. The constitutional tradition within the Mormon faith, therefore, was closer to the British approach of an unwritten constitution of laws and legislation than it was to the American system of authoritative founding documents. The Council of Fifty’s members were eager to receive this course correction. Apostle and prolific author Parley Pratt, who was one of the authors of the draft constitution, noted that he “burnt [his] scribbling” as soon as “a ray of light shewed” that the council was to be the constitution itself. The voice of God’s chosen people was the voice of God.[11]

This delicate balance would soon be tested by both internal personalities and external pressures. Most notably, Brigham Young was not as interested in squaring prophetic counsel with populist governance. At the same April 18 meeting, Young declared that it wouldn’t matter if “the whole church” disagreed with Smith, because Smith “is a perfect committee of himself.” The core democratic principle of compromise was misguided because it hindered progress and qualified God’s rule. Young could not conceive of a “difference between a religious or political government,” as the prophetic authority in the former also wielded control in the latter. This emphasis became only more apparent when Young took control of the council after Smith’s death. In April 1845, Young declared that he would “defy any man to draw the line between the spiritual and temporal affairs in the kingdom of God.” His fellow leaders took notice. Correctly reading the chasm between Mormons and their Illinois neighbors, William Phelps posited that “the greatest fears manifested by our enemies is the union of Church and State.” Yet Phelps was fine with this accusation: “I believe we are actually doing this and it is what the Lord designs.” Young, Phelps, and other Mormons were willing to embrace a principle theoretically alien to the American experiment. The martyrdom of their prophet left them wanting to turn back the errors of disestablishment in total.[12]

Conclusion

The Council of Fifty was, in an important way, a direct response to two issues central to American political culture, which were aptly embodied in Willard Richards’s two questions: What is the proper relationship between church and state? And how should a government evolve in response to the circumstances in which it governs? The Mormon answers to these questions were, admittedly, radical (not to mention short lived). The Church adopted America’s system of democratic governance by the twentieth century, and Mormons are seen as some of the biggest defenders of that tradition today. But in 1844, no solution to the problem of democratic rule appeared definitive. Within two decades, the nation would go to war over the issue of political sovereignty. And in many respects, the same questions posed by Richards remain precariously unanswered even today. So even if the Council of Fifty does not provide resolutions that are relevant for the twenty-first century, the anxieties from which they were birthed are anything but irrelevant.

Notes

[1] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844, in Matthew J. Grow, Ronald K. Esplin, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Jeffrey D. Mahas, eds., Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1844–January 1846, vol. 1 of the Administrative Records series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016), 108–10 (hereafter JSP, CFM); William Clayton, Journal, April 18, 1844, in An Intimate Chronicle: The Journals of William Clayton, ed. George D. Smith (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1995), 131. The rained-out Sunday meeting is mentioned in Joseph Smith, Journal, April 14, 1844, in Andrew H. Hedges, Alex D. Smith, and Brent M. Rogers, eds., Journals, Volume 3: May 1843–June 1844, vol. 3 of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2015), 230. The cold winter is described in William Mosley to Kingsley Mosley, February 18, 1844, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. The rainy spring is mentioned in Robert A. Gilmore to John Richey, July 5, 1844, Church History Library.

[2] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844, in JSP, CFM:121–22.

[3] Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, part 1, art. III, https://

[4] Angelina Emily Grimké, “Letter XII: Human Rights Not Founded on Sex,” in Angelina Emily Grimké, Letters to Catherine E. Beecher: In Reply to an Essay on Slavery and Abolitionism, Addressed to A. E. Grimke, Revised by the Author (Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1838), 115; Theodore Parker, “National Sins,” Sermon Book 10:421, Theodore Parker Collection, Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School, Cambridge, MA. For the religious critique of the Constitution, see Joseph S. Moore, Founding Sins: How a Group of Antislavery Radicals Fought to Put Christ into the Constitution (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015); and Spencer W. McBride, Pulpit and Nation: Clergymen and the Politics of Revolutionary America (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2017).

[5] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844, in JSP, CFM:110–15.

[6] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844, in JSP, CFM:121–25.

[7] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 11 and 18, 1844, in JSP, CFM:92, 95–96, 121–22, 128, emphasis added; see also Patrick Q. Mason, “God and the People: Theodemocracy in Nineteenth-Century Mormonism,” Journal of Church and State 53, no. 3 (Summer 2011): 349–75.

[8] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844, in JSP, CFM:122. For this context, see Jordan T. Watkins, “Slavery, Sacred Texts, and the Antebellum Confrontation with History” (PhD diss., University of Nevada, Las Vegas, 2014).

[9] Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, September 6, 1789, in The Portable Thomas Jefferson, ed. Merrill D. Peterson (New York: Penguin, 1975), 449; see Eric Slauter, The State as a Work of Art: The Cultural Origins of the Constitution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010); and Benjamin E. Park, “The Bonds of Union: Benjamin Rush, Noah Webster, and Defining the Nation in the Early Republic,” Early American Studies 15, no. 2 (Spring 2017).

[10] “The Meeting at Framingham,” Liberator, July 7, 1854; Abraham Lincoln, Speech, August 21, 1858, in Lincoln: Speeches, Letters, Miscellaneous Writings, vol. 1, The Lincoln-Douglas Debates, ed. Don E. Fehrenbacher (New York: Modern Library, 1984), 512. For Garrison’s constitutional views, see W. Caleb McDaniel, The Problem of Democracy in the Age of Slavery: Garrisonian Abolitionists and Transatlantic Reform (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2013); for Lincoln’s, see John Burt, Lincoln’s Tragic Pragmatism: Lincoln, Douglas, and Moral Conflict (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012).

[11] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 25, 1844, in JSP, CFM:137; Pratt is quoted in JSP, CFM:137n412; see Richard Lyman Bushman, “Joseph Smith and Power,” in A Firm Foundation: Church Organization and Administration, ed. David J. Whittaker and Arnold K. Garr (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2011), 1–13; and Kathleen Flake, “Ordering Antinomy: An Analysis of Early Mormonism’s Priestly Offices, Councils, and Kinship,” Religion and American Culture 26, no. 2 (Summer 2016): 139–83.

[12] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844; March 4, 1845; April 11, 1845, in JSP, CFM:119–20, 285, 401.