Appendix: In Sickness and in Health

Mental Health Issues and Access to Treatment

Debra Theobald McClendon and Richard J. McClendon, "'Appendix: In Sickness and in Health: Mental Health Issues and Access to Treatment," in Commitment to the Covenant: Strengthening the Me, We, and Thee of Marriage (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 363–400.

What Is Mental Illness?

Mental illness is complex. It is not always easy to understand how it develops, and it is not always easy to define. We will briefly address these two complexities and then discuss defining mental illness, or psychological disorders.

Understanding the development of mental illness (including addiction) involves examining many intersecting factors coming from a variety of sources, including genetics, childhood development, current and ongoing stressors, the availability of supportive resources, and the ability or inability to use adaptive coping skills. Even with the best assessment techniques available, psychologists may not always be able to explain the origins of certain difficulties. For example, among the most heritable disorders, such as schizophrenia, genetics can only account for up to 50 percent of the contribution to the disorder.[1]

Defining mental illness is also challenging. Even though the professional psychological community attempts to categorize and define mental illness in standard terms so that researchers may contribute to the development of effective treatments, those categorizations have changed, and continue to change over time, as the culture changes. For example, homosexuality was considered a mental disorder in 1980 in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders[2] , yet this is no longer the case.

Thus, for our purposes here, we will define mental illness with a broad-stroke definition that captures its essence without getting tangled up in the details of competing arguments or political correctness that can change over time. In general, mental illness is the presence of all three of the following elements: dysfunction, distress, and atypical cultural response.[3] Let’s take a look at each of these. We will then provide a brief list of disorders that have been classified as mental illness.

Dysfunction

A psychological dysfunction refers to a breakdown of normal functioning in the cognitive, emotional, or behavioral areas.[4] Experiencing uncontrollable crying and grief, restricted emotional reactions (i.e., appearing to have only one emotion, such as anger), memory problems, chronic fear when situations are nonthreatening, and such are all examples of a psychological dysfunction. In this manner, addiction to substances, pornography, gaming, and the like also qualify as mental illness because compulsive behaviors override peoples’ ability to regulate themselves despite consequences. An example of this is someone with substance abuse problems who continues to use drugs in spite of knowing they will lose custody of their children—and then continues to use the drugs once they have lost custody of their children even though they are well aware that they cannot regain custody of their children until they are clean.

How do you know if you or your spouse has experienced a breakdown in normal functioning? Many symptoms (such as fear, agitation, hopelessness, insomnia, obsessions) contribute to the type of dysfunction we are describing. Here are some examples of dysfunction: If you or your spouse cannot seem to get out of bed, take care of basic personal hygiene, or attend required activities—such as work, school, or church activities—there is a problem. If you or your spouse is restricted emotionally so that there seems to be only one emotional response to every situation, there is a problem. If previously enjoyed activities or hobbies provide no interest or excitement and you or your spouse consistently turns down invitations to participate or socialize in order to stay home in isolation, there is a problem. If compulsive behaviors or activities are taking over life so that there is no time or mental space for meaningful interactions and relationships with loved ones, there is a problem. If you or your spouse is seeing or hearing things that others do not seem to see or hear (hallucinations), there is a problem.

Distress

Personal distress is also a required factor in defining mental illness and generally accompanies the breakdown in functioning. This is understandable from a commonsense perspective.

People may suffer from a host of symptoms throughout their life for which they may never seek treatment because the symptoms don’t distress them. In other words, when there is no distress there is no problem. Many symptoms are just a transient part of normal life and nothing to worry too much about (such as an occasional headache or nervousness before trying something new). A common maxim Debra shares with clients is “Normal is not symptom free.” For example, it is possible to have an isolated panic attack that does not lead to continued anxiety problems. In this case an individual would not be given a panic disorder diagnosis because they are not experiencing ongoing distress.

Yet if there is distress, there is a problem. The symptoms which cause us a great deal of concern are the ones that take us to a doctor to seek a diagnosis in hopes of getting treatment. In our panic attack example, when a person has had a panic attack and is very distressed about it, that individual may begin to worry excessively about having another panic attack. With that worry they may then begin to alter and restrict their life and thoughts according to that fear. That type of distress contributes to the possible diagnosis of a panic disorder.

Every disorder has its own flavor of distress. For example, those with depression or bulimia nervosa (vomiting or other purging of their food after eating) are generally very distressed by their symptoms, even experiencing self-hatred. Or those with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have chronic, extreme fears that keep them continuously on edge, which sucks energy away and keeps them agitated. Yet, while those with various disorders all experience distress differently, generally they hate how they feel and what they are doing but are paralyzed and stuck, not knowing how to change it because of the severity of their dysfunction.

However, our definition of mental illness does not necessarily require the individuals suffering from a psychological dysfunction to experience distress. Rather, their behavior can create distress for others. Indeed, it may be an individual’s spouse, family members, or friends that are distressed by their dysfunctional behavior. For example, those with the eating disorder anorexia nervosa starve themselves. As they lose weight and become emaciated, they feel good; they are happy to be skinny and like the attention it may get them. Often, they will not claim they are distressed. Yet family members and friends may become quite distressed as they watch their loved one restrict healthy eating options and become weak and unhealthy, even (rightfully so) fearing for their life in some extreme cases.

Another (trickier) example is when someone has a personality disorder. Personality disorders represent personality types that are rigid, making it very frustrating and difficult to get along with these individuals. Personality disorders develop as an individual develops, line upon line, and their presence may often be very subtle to those who do not know the person well and have limited contact with them. The intensity and pathology of the disorder may not be fully understood by the one with the disorder, as they may respond to those with concerns with an uninterested shrug of their shoulders: “I’ve just always been this way.” In other words, they are not bothered or distressed by their dysfunction. Yet, for loved ones interacting with this person on a daily basis, a personality disorder flavors almost every interaction with deep pathology, such that it makes day-in and day-out interactions very difficult and at times almost unbearable. The loved ones’ distress becomes the red flag that there is a problem, even if the one with the problem doesn’t register it.

Atypical Cultural Response

In defining mental illness, it also becomes important to look at how commonly the problem occurs. Even if there is dysfunction and distress, if the individual’s experience is just like everybody else’s, we just don’t diagnose mental illness. A diagnosis at that point would become meaningless. Instead, the problem is atypical or not culturally expected if it is a deviation from the norm. Generally, most psychological disorders have a prevalence rate of 1 percent, meaning that only one person out of one hundred people has this problem. This represents an atypical cultural response. However, the problem may also be considered atypical for the culture if it is a severe violation of social norms.[5]

Mental Illness Labels and Diagnoses

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders is now in its fifth edition, with 697 pages dedicated to the current perspectives of the American Psychiatric Association regarding defining and describing each mental disorder.[6] These disorders are classified into groups that share common features.

As can be seen in the truncated list above, the scope of possible mental health problems extends well beyond the more ubiquitous problems of depression and anxiety or the more rare but commonly known problems of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Therefore, we have chosen to keep our discussion of mental illness herein at a broad, introductory level, presented in a question and answer format, so as to allow applicability to as many couples as possible.

If you need additional support for a particular mental health challenge, please consult more specialized treatment materials through Internet resources and available books, or seek personalized individual or couple treatment through a licensed mental health professional.

How Do I Know If My Spouse or I Need Professional Help?

If you wonder whether you or your spouse needs professional intervention, we encourage careful consideration of our discussion above. Are all three elements of our definition (dysfunction, distress, and atypical cultural response) present? Perhaps you are not quite sure. If that is the case, we offer three tips on what mental illness is not in order to help you clarify how your particular issues may or may not necessitate professional intervention.

First, mental illness is not the same as struggling with the difficulties of life. We all struggle, and life is hard for the majority of us much of the time. We are taught in the scriptures that “it must needs be, that there is an opposition in all things” (2 Nephi 2:11). Indeed, this opposition is what enables us to become strong. Ralph Parlette has said: “Strength and struggle go together. The supreme reward of struggle is strength. Life is a battle and the greatest joy is to overcome.”[8] Sometimes a person who appears to be struggling with mental illness concerns may be cured with simple changes made to their problematic lifestyle. Such changes can include getting a babysitter for a few hours a week to help with the kids, changing majors at school, changing jobs, getting appropriate medication to assist with chronic medical difficulties, getting enough sleep, improving nutrition, etc.

Second, mental illness is not having particular little quirks, habits, or beliefs that may be a bit extreme or compulsive.

Debra: For example, I laugh at myself over my obsessive quirk of wanting all the books I purchase from the same author, or as part of the same series, to match as they line up on the bookshelf. I will only buy printings from the same publisher and with the same cover design. I will not buy paperback books if the other books I own from the series are hardback.

Once, I ordered a particular copy of a book online for our older daughters specifically because the cover was supposed to match a set I already had at home on the bookshelf. This book was a popular book that the girls were excited to read, and I ordered it without the girls knowing so that I could offer it as a surprise. When it arrived in the mail, it was the right book but did not have the right cover on it. I am embarrassed to admit it, but I was unwilling to give the girls the book. In fact, I did not give the book to them for many months, waiting in hopeful expectation of finding the particular printing I wanted at a local thrift store. It was only after writing about it in this chapter, and laughing at how silly I was, that I finally gave our daughters the book. However, even now, when I look at that series of books on the bookshelf, it still bothers me that that book doesn’t match the others from the same author.

Admittedly, this is quite obsessive, but as my urge for book matching does not interfere with my general ability to function in life and since I have no other extreme obsessive symptoms, we can chalk it up to a silly quirk and simply laugh at it.

Third, mental illness is not struggling with common spiritual struggles of unrepentance, which may bring guilt or emotional fear. A person experiencing significant guilt over unresolved sin may display many of the symptoms of mental illness, particularly those of depression; however, this doesn’t mean they are depressed. In the Book of Mormon, Alma described the state of his soul as he recognized the reality of his guilt:

I was racked with eternal torment, for my soul was harrowed up to the greatest degree and racked with all my sins.

Yea, I did remember all my sins and iniquities, for which I was tormented with the pains of hell. . . .

Oh, thought I, that I could be banished and become extinct both soul and body, that I might not be brought to stand in the presence of my God, to be judged of my deeds. (Alma 36:12–13, 15)

Yes, these symptoms and feelings can be extremely distressing. But when the sin is confessed and dealt with through a bishop or other ecclesiastical leader with appropriate priesthood keys, the symptoms dissipate. Alma also illustrates this miracle of light returning to him when he turned his thoughts to the Savior: “And now, behold, when I thought this, I could remember my pains no more; yea, I was harrowed up by the memory of my sins no more. And oh, what joy, and what marvelous light I did behold; yea, my soul was filled with joy as exceeding as was my pain!” (Alma 36:19–20).

Therefore, if we reflect on these three considerations and remain true to our definition of mental illness—the presence of impairment or dysfunction, distress, and atypical cultural response—the question as to the necessity of treatment for ourselves or our spouses becomes easier to answer. In each of these areas (common life struggles, obsessive quirks, or spiritual trials resultant from unrepentant sin), mental illness would not be considered as a contributing factor to the mental health difficulties.

Ecclesiastical Leader or Mental Health Professional?

In a quick note here about the difference between ecclesiastical leaders and mental health professionals, we look to Elder Alexander B. Morrison, who has given specific attention to mental illness in large measure because of his own experiences trying to help his daughter, Mary, with long-term panic attacks and depression.[9] In an Ensign article, he carefully outlined the respective roles of bishops and professionally trained mental health workers:

Those who, like Alma, experience sorrow during the repentance process are not mentally ill. If their sins are serious, they do require confession and counseling at the hands of their bishop. As part of his calling, each bishop receives special powers of discernment and wisdom. No mental health professional, regardless of his or her skill, can ever replace the role of a faithful bishop as he is guided by the Holy Ghost in assisting Church members to work through the pain, remorse, and depression associated with sin. . . .

We must understand, however, without in any way denigrating the unique role of priesthood blessings, that ecclesiastical leaders are spiritual leaders and not mental health professionals. Most of them lack the professional skills and training to deal effectively with deep-seated mental illnesses and are well advised to seek competent professional assistance for those in their charge who are in need of it. Remember that God has given us wondrous knowledge and technology that can help us overcome grievous problems such as mental illness. Just as we would not hesitate to consult a physician about medical problems such as cancer, heart disease, or diabetes, so too we should not hesitate to obtain medical and other appropriate professional assistance in dealing with mental illness. When such assistance is sought, be careful to ensure, insofar as possible, that the health professional concerned follows practices and procedures which are compatible with gospel principles.[10]

Richard: As a second witness to what Elder Morrison has said here, may I say that during my time as a bishop I found that the Lord helped guide me in knowing the difference between a spiritual matter and a mental health problem regarding a member of my ward. Often I could help support them and teach them about spiritual things, but I knew that my abilities were limited when it came to counseling about a mental health challenge either for them or a family member. In these cases, I directed them to a mental health professional, who could assist them in ways that I could not. It was truly satisfying to see how, after a few weeks or months of treatment, they were able to improve and manage their life in a much healthier way.

Mental Health Symptoms and Related Factors

So what types of behaviors do indicate that you or your spouse may need professional mental health intervention? In addition to considering our earlier discussion about dysfunction, distress, and atypical cultural responses, warning signs include such things as extreme spending or erratic behavior, loss of interest in sex, sloppy grooming and housekeeping, chronic insomnia, aggressive or violent behavior, and the like. Particularly concerning are issues relative to personal safety, such as frequent suicidal ideation or fantasy, self-harm or self-mutilative behaviors (e.g., cutting, burning, and hair pulling), or outright suicidal behaviors (such as overdosing on pills and then going to the emergency room to get their stomach pumped).

As mentioned earlier, the frequency and longevity of problems are also factors in deciding if treatment is necessary. If mental health difficulties are infrequent or transient, it is not likely necessary to seek treatment; those types of issues are common and mostly indicative of the heightened stress typical of life’s challenges. If those same symptoms, however, come and go over a lengthy period of time, masquerading as transient problems but wielding their ugly heads repeatedly, they may be indicative of deeper issues. In that case, treatment from a qualified mental health professional would be useful to improve quality of life, but it may not necessarily be required if the individual shows good levels of resilience and if normal functioning is maintained. But if those same symptoms largely take over one’s life by causing difficulty in functioning in day-to-day activities, thus making the individual incapable of engaging appropriately in life or unable to bounce back after even small setbacks, treatment would be highly recommended—if not considered mandatory. Additionally, if a problem is severe, such as a suicidal gesture, one instance may be enough to warrant seeking professional mental health treatment.

Also important in considering the necessity of treatment is taking inventory of one’s coping capacities. A person with little stress tolerance and few coping skills will generally require treatment at an earlier stage than will a person with a high tolerance for distress and a cornucopia of resources to assist them in maintaining adaptive functioning.

A word of caution may be useful here. The assumption could be made that someone who is functioning externally in life does not need treatment. Many depressed clients are severely emotionally impaired—with suicidal ideation or engaging in self-harm behaviors—even though they still succeed in school or excel in their professional endeavors. Outward functioning does not necessarily equate with level of dysfunction. To have a better idea of what the level of dysfunction is, you or your loved one should reflect on the following questions: How do you feel you or they are coping? What is your or their quality of life? Do you feel you or they are out of control? Are you or they in control, but the effort required to retain that control is an exhausting, constant struggle?

Finally, the onset of mental health symptoms is another important consideration relative to the necessity to seek professional mental health treatment. A common adage used in abnormal psychology is “The earlier the onset, the poorer the prognosis.” Early onset of mental illness is, therefore, generally indicative of a more severe disorder that will be more difficult to treat and have a poorer outcome. For example, if your spouse begins having memory difficulties in their early fifties, even if symptoms appear mild you would be wise to get them assessed and involved in treatment as soon as possible, as this could be an early onset of neurocognitive disorder, formerly known as dementia.

How Do We Get the Right Treatment for Our Needs?

Initial efforts to seek treatment will be specific to the difficulties you or your spouse are experiencing. For some psychological symptoms that mimic symptoms of common physical ailments, the first trip to the doctor may be to a physician’s office. For example, people with panic disorder often go to the emergency room of the hospital, as the symptoms of panic mimic symptoms of a heart attack. Sometimes, after several emergency room visits and test results assuring a patient that there is no medical problem with their heart, a doctor may suggest the problem could be psychological, offer a prescription of some sort of tranquilizer to help with the anxiety, and make a referral to a mental health professional. For others who know the issue to be of a psychological nature—such as a person who is struggling with deep, complicated grief following the death of a loved one—the first appointment they make may be to see a psychologist.

Be aware that the medical and psychological communities operate from different perspectives and thus have different biases and treatments. Understanding this basic premise is critical to be informed consumers of treatment. If you or your spouse is struggling with depression, anxiety, or another such psychological difficulty and you go to a physician, the physician will likely recommend taking antidepressants, antianxiety medications, or other relevant medications. In a study examining primary care physicians’ approach to treating depression, 72.5 percent of the doctors gave the patient an antidepressant medication prescription compared to only 38.4 percent that gave patients a referral to a mental health provider.[11]

On the other hand, psychologists have a bias that often leads them to avoid medications altogether, especially for those with mild or moderate problems. One meta-analysis, which compares the results of several research studies in order to examine overarching patterns, shows that antidepressants work no better than a basic placebo for most people and that these drugs are most helpful for those at the extreme level of depression only.[12] Thus, many clinicians tend to avoid recommending medications and will only do so for more severe cases. In the aforementioned panic scenario, panic attacks are easily treated with psychological treatment, and generally psychologists or other mental health professionals will not suggest that an antianxiety medication is needed due to the effective nature of panic treatment and the high relapse rates of medications.

Therefore, when faced with the decision of what types of treatments to secure, the best thing you can do is to do your homework; get opinions from both the medical and psychological communities and then make the decision that you feel would be best for you and your spouse in regard to treatment, taking into account your specific problems, long-term goals, and treatment objectives.

Types of Mental Health Professionals

In seeking psychological treatment, people often have questions regarding what type of mental health professional they should be seeing. First know that psychotherapy is a licensed profession and that all mental health professionals, regardless of type, should be currently licensed with their state. You can check the status of a clinician’s license through online resources.

There are many types of licensed professionals that provide psychotherapy, yet their level of training, experience, and areas of focus vary widely, so it is important to be aware of the similarities and differences between them. Professional counselors, licensed clinical social workers, and marriage and family therapists are generally master’s level (MA) clinicians with high levels of experiential hours. Professional counselors assist in general counseling and often in substance-abuse treatment. Licensed clinical social workers are social workers who have also received general counseling training to assist with mental health difficulties or daily living problems. A marriage and family therapist has training in general mental health issues and counseling interventions yet focuses their work on the family system and its role in perpetuating mental illness or other difficulties. A psychologist is a doctoral level (PhD or PsyD) clinician with expert training in mental illness (abnormal psychology) and its treatments, high levels of experiential hours, and experience in mental health research.

Research has suggested that therapist training is a relative factor; those with more training tend to produce better client outcomes.[13]

Psychotherapy, also referred to as simply therapy or counseling, is an effective process by which many people are strengthened, healed, and given valuable coping skills. Researchers who have studied the effectiveness of therapy have consistently found that it produces positive outcomes. They have found a range of therapeutic benefits by examining the results of many studies through meta-analysis and found moderate effect sizes of 0.60 to large effect sizes of 0.85.[14] This means, generally speaking, that the person who engages in psychotherapy treatment is better off than 60 to 85 percent of those who do not receive treatment.

Psychotherapy usually consists of individualized treatment sessions in which you visit alone with a mental health provider who then develops a personalized treatment plan and works with you on that plan throughout the treatment process. Psychotherapy can also be done with others, such as your spouse, a parent, a sibling, or others if familial relationships are problematic and contributing to the mental health difficulties.

Psychotherapy can also be done in groups. Group therapy is often used as an adjunct treatment for those already in individual treatment, but this is not necessarily the case and may also be used as a primary treatment. In group therapy, the dynamic relationships of group members become tools of therapeutic intervention, so one does not just benefit from insights and treatments from the therapist but learns from their fellow group members through the modeling of various behaviors, gaining a sense of not being uniquely alone in their problems (universality), and helping and supporting each other (altruism).[15]

Generally, psychotherapy treatment is done on an outpatient basis, in which you attend a session, perhaps once a week, as you continue living in your own home and engaging in your own activities, such as going to school or work. For those with more severe disorders that are interfering with daily functioning, more intensive treatments—such as day programs (living in the home but attending treatment for several hours a day), inpatient treatments (living in a hospital for a number of days to weeks), or even residential programs (living in a treatment facility generally for several months to years)—are available. In the more intensive programs, you will often receive a combination of individual, family, and group therapies to maximize outcomes.

Be aware that the higher the level of intensity, the greater the cost of the program. An average inpatient or residential treatment center is approximately $1,000 per day. Therefore, you always want to begin with the least invasive, less expensive treatment that will meet your treatment needs. If you find the treatment you have selected is not meeting your needs, you would be wise to increase the level of intensity with a more invasive treatment program.

Psychological treatment is a process that requires a varying number of treatment sessions: a few sessions for mild problems, a protracted process for more long-term or severe difficulties. It is not uncommon for many difficulties to be effectively treated in eight to fourteen sessions.[16] This is an important point—for many people who attend treatment, psychotherapy is a short-term process.

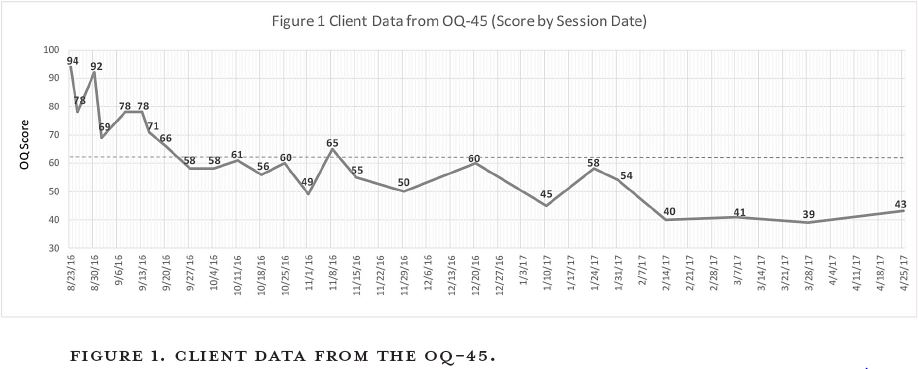

Debra: As an example, I was contacted by the parents of a twenty-two-year-old young man suffering with obsessive-compulsive disorder complicated with depression and attention deficit problems. His distress was very high, his quality of life was poor, and his issues were creating problems in his new marriage relationship. He had tried medication for eight months and felt it made things worse. He was willing to attend therapy because he was tired of suffering and didn’t want to destroy his new marriage. Due to the severe nature of his difficulties, treatment began with two sessions per week for the first five weeks. Within a few sessions, his distress levels dropped significantly, and he began thinking in different ways that allowed him to process reality in a healthy way again. His distress and symptom levels continued to drop, and within nineteen sessions (four and a half months) he was functioning well within the normal range. You can see data collected during his treatment sessions in figure 1. These data points are from the OQ-45 that was developed by BYU researchers.[17] The OQ-45 is a measure that tracks symptom distress and functioning over the course of treatment. Please note that in this chart a score of 45 is the average score for someone not in therapy while a score of 63 is the clinical cutoff, meaning an individual warrants treatment if their distress score is higher than 63. This client’s initial score was a high 94, whereas the last score shown on this chart is a 43.

Although this client’s level of functioning was well within normal range after four and a half months (as seen by his score of 45 plotted on the graph), we continued to meet to work on relapse prevention as well as to address some of the marital issues that had developed over the course of his illness. As you can see on the graph, he continued to stabilize in the normal range thereafter. He reported: “The speed at which I can process reality now averages within five seconds to five minutes. Don’t get me wrong; there are occasionally a few setbacks where it takes me a day to recover, but that is very seldom. I would recommend therapy to everyone.”

Although this client began treatment with two therapy sessions per week (whereas most people will generally begin treatment with one session per week), please note that this example is not unusual in regards to the speed by which he began to heal and regain his quality of life; many people have similar treatment outcomes after relatively brief therapeutic interventions.

Before I move on, it is important to note that this client’s story has another side to it—how his healing blessed his wife and the quality of their marriage. In addition to regaining health and an improved quality of life, he also regained a positive relationship with his spouse.

My husband’s crippling anxiety was plaguing our relationship. We were newlyweds, and our relationship was full of misunderstandings and unfounded accusations that made it difficult to perform well in school and work. Therapy didn’t change him overnight; however, after months of hard work he overcame his challenges. Through therapy he gained improved communication skills, emotional intelligence, confidence, and empathy . . . in addition to learning to manage his anxiety. It has transformed our marriage! The difference is like going from night to day. I finally feel like I can be myself around him without worrying that he will interpret something I do or say the wrong way. He is now my biggest source of support and comfort, instead of a burden and source of angst. We trust each other more, treating ourselves as equal partners in the marriage. I will be forever grateful that my husband courageously sought the help he needed.

We hope the point we make here is clear: treatment will not only bless you but it will also bless your spouse and your marriage. If your own misery is not enough to spark a willingness to seek appropriate treatment for your mental health concerns, then please humbly seek the treatment you need for the sake of your spouse and your marriage. Allow that concern and welfare for them to encourage you to move toward health.

What to Expect in the Treatment Process

In the therapeutic community, the modal number of therapy sessions is one. This means that many people attend therapy once and never return. Debra was once told by a client whose husband resisted attending marital counseling that her husband might be willing to go to a therapist, but only once—that if the therapist was worth anything, they’d get the job done in one session. In this case the problems that led to the need for therapy had developed over a thirty-year period. If only mental health professionals had a magic wand! We hope to educate you enough about the treatment process here to understand that you will need to attend therapy more than one time.

When you meet with a therapist, the first session or two are actually assessment meetings in which the therapist is largely gathering information in order to develop a treatment plan. Generally, there is no official therapeutic intervention employed during this initial process other than the offering of hope and encouragement that things can improve for you in your particular difficulties as you commit to return and work the therapy process.

These assessment sessions are also important for you as the client. This is a time to get a feel for the therapist and assess goodness of fit. If there is not a feeling of connection to the therapist or a strong sense that they know how to assist you, consider seeking another treatment provider. If you or your spouse is not comfortable with a particular mental health counselor, it is likely that you will not feel comfortable allowing that person into the vulnerable or painful parts of yourselves that need healing, thus limiting the helpfulness of the therapy process.

In addition, researchers have identified therapist variables associated with creating better outcomes for clients. In the first couple of meetings, you will want to get a sense for “(1) the therapist’s adjustment, skill, and interest in helping patients; (2) the purity of the treatment they offer; and (3) the quality of the therapist/

So shop for a therapist like you would shop for a car; test drive them before committing to one in particular. A good way to reduce the time, stress, and expense of this searching process is to get referrals from those you trust or to read reviews posted online by those who have met with that treatment provider.

Generally speaking, the therapist will assess your personal history and needs, set some therapy goals, and then work with you collaboratively to address each of those goals. You will be the expert on your life experience, the therapist will be the expert on how to enact therapeutic change on your behalf, and you will both bring your expertise to the table to create a wonderful partnership of healing and growth. Some of the therapeutic goals may be quickly addressed (such as improving sleep, diet, or hygiene), while some may take more substantial amounts of time (such as working through issues and trauma related to abuse, chronic depression, or personality difficulties).

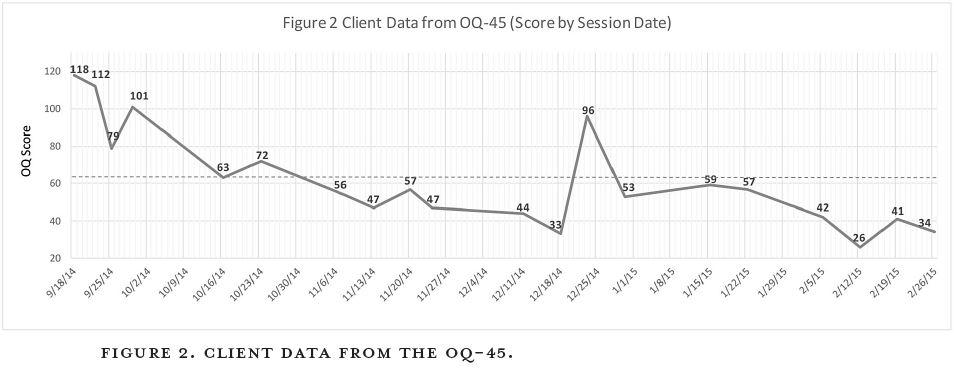

Debra: For example, one client struggling with severe depression came in to see me. As I assessed her symptoms, distress, and personal circumstances, I had an initial sense of where treatment should begin. However, as we talked together I asked her about her goals for therapy, what she wanted to accomplish. After she laid out her goals, I asked her which goal felt like the biggest priority to her—what was most strongly driving her depression at that time. Her answer was not what I expected. Instead of beginning treatment with what I thought, we began with what she thought was most important. She knew what she needed!

Instead of immediately getting into deeper issues related to a negative cognitive style, difficult circumstances from her adolescence, insecurities about her professional competence, or the like—all important, and all topics we did eventually work with in therapy—we began with parenting issues for her young toddlers. The intensity of parenting two toddlers had ramped up the level of distress and her feelings so that she could not cope in her life. Within five sessions, her distress level had dropped significantly. We were then able to see more clearly how the deeper issues were playing into her depression and work with those issues without the feelings of desperation and crisis she had experienced initially because of feeling out of control with her children. Her treatment was very successful. We can see in figure 2 the OQ-45 scores for her first twenty sessions. Although this chart shows her distress level well within the normal ranges after twelve sessions (with a score of 33), we continued therapy for a time to address some deeper, long-standing painful issues from her adolescence.

It is quite clear that her score shot up to a 96 on session thirteen. Confronting her deepest pains and torments terrified her and caused her a great deal of distress. Yet she bravely kept with therapy and did what she needed to do to get healthy. After that one difficult session when her fears were highly activated, her distress levels went back under the clinical cutoff, although the distress of that particular therapy content kept her distress score a bit higher than it had been previously for three more sessions. You then see her scores drop again, and her distress level was almost identical to where she was before we began the really tough stuff, dropping to her lowest scores yet, 26 and 34. This illustrates well the ups and downs of the therapy process on any given day but also shows the overall trajectory that occurs as one continues treatment.

The critical thing about this data is that these numbers represent real pain and distress. This client started with an exceedingly high score of 118. In just under five and a half months her distress level registered a score of 34, well within the average range for someone not in therapy. The tremendous impact of this type of change in her life cannot be understated. The client said this about her change:

It’s amazing the baggage I was carrying that I wasn’t even aware of. It’s so much lighter being able to be a normal, functioning adult instead of one who is carrying all this unseen and very heavy baggage. At a score of 118—there aren’t even words to describe it. I couldn’t picture a future. I-didn’t-think-I-would-be-there-to-see-my-kids-grow-up type of thing. It just wasn’t feasible in that state of mind. It was just nothing and it was just so overwhelming. I could only do the bare minimum. At a score of 34—it’s like being a different person. It allows me to be who I really am rather than being clouded by depression. I am actually enjoying being alive and actually enjoying being a mom and enjoying everything I never thought would be possible for me to enjoy ever again.

This type of change changes lives! This type of change is possible in your life or in the life of your spouse. Therapy works.

What you actually do in your therapy sessions will vary based on your particular needs, the therapy goals you and your therapist have established, and the style of your therapist. There are many theoretical orientations taken by clinicians. This means there are a variety of psychological theories that look at how mental illness develops and how to enact change in that illness in order to break through the “stuckness” that the dysfunction and distress are causing in the person’s life. That theoretical orientation will influence the approach your therapist takes to your problems. In addition, the personality style of the therapist will also impact their approach in the therapy process.

You may spend your time in therapy doing some of the following: working on starting healthier behaviors or working to quit problematic ones, talking about dynamics or events from your childhood, role-playing current interpersonal difficulties to learn more adaptive responses, learning new cognitive skills, journaling about past or present scenarios, filling out worksheets or other written exercises, and the like. Your therapy will be your personal process, and the course of your treatment will be determined together by you and your therapist. As seen with the client above, sometimes the work you do in therapy will elevate your distress because you are facing difficulties that you have spent many years trying to avoid. A metaphor I commonly use as I describe the therapy process is that of doing a really good deep cleaning of your bedroom. Deciding to do a thorough cleaning requires you to start pulling things out from under your bed, from the upper recesses of your closet shelf, and from behind the door. As you do this, you just throw it all in a massive pile on your bed or in the middle of the floor. Ten minutes into the cleaning process, your messy room is now completely trashed! Do you panic and say, “I better quit cleaning my room; it’s making it worse”? No, because you understand what you are doing and you trust the process. You keep going. And, generally speaking, it doesn’t take too long after that to start sorting and organizing and getting everything into its proper place in the room.

So too with the therapy process. It is understandable that you may not trust the therapy process because it is unfamiliar to you and you may not see how it can help you, but your therapist knows it. Trust your therapist to help see you through the process, and you, too, can enjoy the benefits that come—just as you enjoy the benefits of a clean and orderly bedroom when you do the work.

Sometimes, as part of the treatment process, you may need medication (you may hear the term psychotropic medication). If this is the case, you or your spouse would generally secure the assistance of a psychiatrist, which is a medical doctor (MD) who has done specialty training in mental illness and psychopharmacology (drugs). Psychiatrists generally do not conduct psychotherapy but meet with patients for brief appointments to discuss medications compliance, side effects, and needed medication adjustments. Thus, it is common for an individual to meet regularly with a mental health counselor for therapy and then meet with a psychiatrist once every few months for medication management. Psychotherapy providers, such as psychologists and master’s-level clinicians, do not prescribe medication (although some states are making additional training available for what are termed prescription privileges).

Once treatment begins, it is critical that you or your spouse follow the treatment protocol established by your treatment providers. Haphazardly taking medication will not provide a therapeutic dose, and failing to attend therapy or to do planned interventions or assignments between therapy sessions limits the therapeutic benefit of psychotherapy.

How Do We Find a Therapist?

Finding a therapist usually starts with an assessment of the financial resources already available to you through insurance coverage if applicable. If you check a summary of your insurance plan’s coverage, you can examine the mental health coverage listed for in-network and out-of-network providers. Some plans have excellent mental health benefits, but some have very poor coverage.

For individuals with mental health benefits, finding a therapist can be as simple as going to your insurance company’s website and locating a list of contracted or in-network providers in your area. You then choose one of those based on location, recommendations or reviews, or other such criteria. In those circumstances, you will pay the co-pay established by your insurance company for each treatment session or service rendered.

If you have insurance coverage but choose a therapist outside of the insurer’s contracted network, you may still be able to get your insurance company to reimburse you with a portion of the service fees if it so states in the insurance plan summary. In those cases you would choose a therapist (such as a local provider that has good reviews posted online or one for which you received a strong recommendation) and simply go to them and pay their standard treatment fee. The therapist will provide a receipt that you then submit personally to the insurance company. The company then reimburses you the amount established by your insurance plan for an out-of-network provider.

For those who do not have insurance coverage for mental health treatment but have access to sufficient financial resources, you may choose any therapist and pay their fee directly. Paying out of pocket may be a difficult decision for some, as it can be difficult financially and emotionally to commit to pay for therapy. This decision to pay for therapy (rather than foregoing treatment) may prove to be one of your best investments.

Debra: One of my cash-paying clients had tight finances but, knowing she needed help, chose to enter therapy anyway. At the end of her treatment, which lasted ten sessions, this client said that it was “worth every penny.” Three years later, she and I had a brief email exchange in which she strengthened her conviction and wrote to me, “It was definitely worth every penny!”

For those who do not have access to sufficient financial resources, seeking out community clinics in your area may be a wise choice. If you attend school, counseling services are often included for free or for reduced fees on college and university campuses. If you live near a university, there are often training facilities in which graduate programs give their students supervised therapy experience by offering reduced-fee services to the general, nonstudent public. If your employer has an employee assistance program, it may be possible to receive therapy benefits. For example, some companies offer a certain number of therapy sessions for free each calendar year. LDS Family Services may also be a lower-cost option than seeking treatment from a private therapist.

Lastly, there are times when LDS bishops have intervened financially to help a ward member receive at least initial treatment intervention. As these financial helps use fast-offering funds, they should only be sought out as a last resort and with careful counseling with your bishop. A bishop may agree to pay for initial sessions but may contract with you to provide service or such in return for the financial assistance.

Do We Need an LDS Therapist?

It is common for Christians with high levels of committed religiosity to desire to see Christian therapists.[19] Likewise, many LDS individuals and couples may feel a desire to work with LDS therapists.

Debra: When I first began seeing therapy clients, I lived in California. My clients generally had no religious orientation, and they never asked if I had a religious orientation. It was simply a nonissue. In an LDS community, it plays out very differently. Since I am now located in Utah, the majority of my clients have been LDS, and the fact that I am an active member of the LDS Church has been of paramount importance to them. Here are some thoughts on this issue from a few of my clients:

It was extremely important to me. I had seen another therapist previously who wasn’t LDS, and even though she tried, we couldn’t discuss spiritual things the way I wanted to.

It was very important to be able to relate to someone who I thought shared my same values and standards . . . an understanding of my frame of reference in discussing my experiences. A solid LDS therapist has a much better idea of where I want to go. They are also better able to help me resolve issues where I think I’m out of balance with LDS values. I’ve been to a marginally active LDS therapist who was way too far into theories of self-actualization. It didn’t work for me.

I cared more about the therapist being Christian. I didn’t want to have to spend therapy time defending or introducing my values. Also, I didn’t want to have to spend session time to explain about the sex culture and other LDS cultural terms.

It was important to me because some of the things I was struggling with were of a religious nature, specifically through LDS beliefs. I don’t think another counselor outside of the LDS religion would have understood.

In the beginning I was dealing a lot with feelings of returning home early from an LDS mission, and with therapy or opening up to any person, it’s important for me to feel connected and understood. I didn’t think I could achieve that with someone who was not LDS and didn’t understand the mission aspect.

There’s a definite advantage to having an LDS therapist; they understand the stresses from the Church without encouraging you to just leave and find a new church.

For couples living in Utah, it is not difficult to find therapists from all professional areas of training who are members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints if they so desire. For others this may become a problem, as LDS therapists may not be readily available in their area. For LDS couples in rural areas, the task of finding an LDS therapist may be virtually impossible. It is not uncommon to have members of the Church travel many hours each direction in order to be able to meet with an LDS therapist.

Is this necessary? We believe there are several points for consideration as you decide whether finding an LDS therapist is the right choice for you.

First, for what purpose are you seeking therapy? If you are seeking sex therapy, we would, as we recommended in chapter 6, encourage you to seek an LDS therapist if at all possible. An LDS therapist would be more likely to be sensitive to your sexual culture and the types of sexual interventions they will recommend during your treatment process. If you are seeking marital counseling relative to difficulties in the relationship that are faith based, such as issues around gender roles, priesthood, and the like, we believe it would be most useful to meet with an LDS therapist.

We do believe that a well-trained, more advanced therapist of any religious affiliation (or of no religious affiliation) will be sensitive to religious influences. They will encourage you to teach them about your religious belief and be respectful to those influences in your life. They will use interventions that will not violate your personal or religious beliefs. However, not being familiar with the tenets of the religion, or especially with its cultural nuances, could impose some limitations during the therapy process, as they may miss things or fail to provide insights an LDS therapist may readily see or provide that may prove critical to healing.

If you are seeking psychotherapy treatment for nonreligious issues—such as dealing with anger, money or time management, basic communication skills, substance abuse, or the like—we believe the religious orientation of the therapist may not need to be a major consideration in your selection of a therapist. In these cases, issues such as the therapist’s level of training, area of expertise or the focus of their practice, and goodness of fit would likely be of greater importance than religious affiliation.

Second, as you consider whether to seek treatment with an LDS treatment provider, it is important to remember that not all LDS therapists are of equal training and competence. One of Debra’s clients shared this feedback:

I preferred an LDS therapist because I needed someone who would understand my faith and its part in the healing process and in my progress. I can’t separate my faith and my therapy. They need to go hand in hand. But not just any LDS therapist would do. Therapists, even LDS ones, are not created equal. There are other factors as well, such as knowledge, experience, maturity, style, theoretical philosophy, and approach to diagnostic testing.

A good therapist will ask you what it means to you to be LDS, regardless of their religious orientation. We mentioned this above, but it is necessary to highlight the point that this is also important if your therapist is LDS. If you have a therapist that is highly trained, competent, and conscientious about providing good treatment, they will ask you questions rather than make assumptions. Therapists may make the mistake of assuming that because they share religious affiliation with you as a client, what it means to them to be LDS is what it means to you. This assumption can become a problem in your therapy if your meanings are indeed different.

If you find an LDS therapist who is not sensitive to this issue, the fact that you share your religious affiliation may not necessarily be useful in the therapeutic process and you may be better off with another therapist, even if that means meeting with someone who is not affiliated with the LDS Church. One research study supports this idea, indicating that religious similarity between the client and therapist did not necessarily produce the best therapeutic outcomes.[20]

A third consideration is the cost of seeking treatment from an LDS therapist, relative to money, time, and energy. If you find a great LDS therapist that seems ideal for your particular needs but meeting with them requires a three-hour drive each direction, you may want to rethink the plan. A lengthy drive each direction adds a great deal of money to the cost of the treatment process when taking into account transportation costs. It also adds significant stress to the therapeutic process by requiring a greater time and energy commitment and a dramatic rearrangement of your weekly schedule. This puts pressure on both therapist and client that does not allow the treatment process to unfold naturally (and therapy is already a lot of work, so the additional stress may be counterproductive).

For example, a client living a great distance from a particular LDS therapist may decide that they can only handle making the long drive a handful of times, so they would then limit the therapist to only a few sessions. Putting this type of arbitrary session limit on the therapeutic process is likely to only create disappointment and frustration for both of you. Instead, a therapist closer to your home, even if they do not share your LDS religious affiliation, may offer you a much better treatment experience because they have the space to provide treatment that can promote true healing.

Lastly, as you consider whether it is necessary to the success of your therapeutic process to have an LDS treatment provider, it may simply come down to your personal preference and comfort. It may simply be the case that you want an LDS therapist that understands doctrinal and cultural nuances, as it gives you more faith that the therapist will understand you and your specific needs. Comfort with the therapist is very important and may prove more important to you than the distance of the drive or other considerations.

Debra: When all is said and done, if it is your preference to meet with an LDS therapist and you are unable to do so, please do not use the inability to locate an LDS therapist as a reason (or an excuse) to not go to therapy. One of my clients had this feedback about the importance of the therapist’s religious orientation:

[Meeting with an LDS therapist] was not my priority. I wouldn’t be able to talk about church stuff straight up [with a non-LDS therapist], but that was not a priority for me at the time. I was focused on getting healthy. Spiritual stuff could wait.

I want to underscore the importance of this point. If you prefer to work with an LDS therapist and an LDS therapist is not available, please make getting healthy your priority and go see a competent licensed professional in your area, regardless of religious orientation.

What Do I Do If My Spouse Refuses Treatment?

You may be more than willing to seek your own treatment, but what if it is your spouse that needs the mental health treatment or you need treatment as a couple and your spouse is not so inclined?

Here are some considerations.

Some aspects of treatment may be more amenable to your spouse than others. Even if you feel strongly that your spouse needs a particular type of treatment that they are currently refusing, if there is any facet of therapy they are willing to engage in, go for it. As some healing occurs, their willingness to pursue additional treatment may increase. Allow time for the process to unfold. Take whatever your spouse is willing to put their energy into and support them in any way that you can. Yet be cautious that you do not micromanage them, causing resentment toward both you and the treatment process. Allow them stewardship over their own process and offer to be a support and comfort when needed.

Elder Jeffrey R. Holland reminds us: “Broken minds can be healed just the way broken bones and broken hearts are healed. While God is at work making those repairs, the rest of us can help by being merciful, nonjudgmental, and kind.”[21]

Ultimately, your spouse has the power to exercise their agency and refuse treatment. In these cases, you can seek support for yourself through accessing online support groups, reading self-help books, or seeking personalized psychological treatment to learn how to cope with the difficulties the mental illness is producing for you and your relationship with your spouse. Family therapy operates on a basic premise that by changing one member of the family the whole family can change, since the habitual and dynamic patterns of interpersonal relationships by necessity change when one person is behaving differently. So the therapeutic community generally believes that if your spouse refuses treatment, you should still go. You can help your spouse by getting help yourself.

What Do I Do If My Spouse Is in Crisis?

Agency is a powerful gift from God. In the Pearl of Great Price we read, “In the Garden of Eden, gave I unto man his agency” (Moses 7:32). Thus, we should seek to support another’s use of agency, that “every man may act in doctrine and principle pertaining to futurity, according to the moral agency which I have given unto him, that every man may be accountable for his own sins in the day of judgment” (D&C 101:78).

We seek to respect the agency of our spouse. Yet, in some isolated circumstances, you as a spouse must decide to act in a way that limits your spouse’s exercise of agency. This will only occur in rare circumstances and usually when there is a safety issue at play.

For example, if your spouse is struggling with dementia and they have repeatedly overdosed on their medications, you will likely make the choice to take their medications from them and only distribute them at the appropriate times to take them, even if your spouse protests.

In like manner, a person who becomes acutely suicidal does not have the mindset to be able to exercise their agency clearly, and you will likely need to take them to an emergency room, even if they attempt to physically resist you or verbally assault you in the process. In a circumstance such as this, if your spouse becomes physically aggressive, do not put yourself in danger, but call 911 and have a police officer escort them to the emergency room. Do not try to transport them yourself if they are in the middle of a psychotic episode, panic attack, or other extreme emotional meltdown.

If your spouse becomes verbally aggressive, insulting, or abusive, don’t take it personally but don’t back down. You can continue to assure them that you are trying your best to support them and keep them safe and that you love them. This will ultimately lead to a strengthening of marital ties when energies are calm and stability is reclaimed.

If you have to involve the police in an acute situation with a spouse who is mentally ill or under the influence of drugs or alcohol to maintain your safety, be aware that the authorities may hold an individual against their will (involuntary commitment) for a specified period of time (this varies from state to state but is often between three to five days). This time allows the authorities to conduct their own assessment to see if additional services, such as a hospitalization, may be warranted. If the state finds that additional treatment is required and the individual will not consent to treatment, a court order may be issued to continue to hold and treat the individual.

Conclusion

As you can see throughout this discussion of mental illness and treatment considerations, mental health issues are tricky and complicated. Taking a thoughtful approach is imperative to getting the appropriate assistance for you or your spouse. If you continue to be unsure about the need for mental health intervention, we would recommend a mental health assessment conducted by a licensed mental health professional. Let them tell you if they believe treatment is needed and how they see treatment will benefit you. Then you and your spouse can evaluate your circumstance from a more informed position.

Treatments are available—and they work in the large majority of cases! There is no need to continue to suffer and endure a poor quality of life. Be willing to work at therapy and to find the peace and stability of living with greater emotional resources and resilience and of living free of the debilitating effects of mental illness.

Notes

[1] David H. Barlow and V. Mark Durand, Abnormal Psychology: An Integrative Approach, 6th ed. (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 2012), 34.

[2] American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed. (Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1980).

[3] Barlow and Durand, Abnormal Psychology, 1–2.

[4] Barlow and Durand, Abnormal Psychology, 2.

[5] Barlow and Durand, Abnormal Psychology, 2.

[6] American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. (Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013), 31–727.

[7] American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th ed., 87, 123, 155, 189, 235.

[8] Spencer W. Kimball, The Miracle of Forgiveness (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1969), 164.

[9] Carrie A. Moore, “Elder Morrison Gets Service to Humanity Award,” Deseret Morning News, 2 April 2004, http://

[10] Alexander B. Morrison, “Myths of Mental Illness,” Ensign, October 2005, 33–34. See also Alexander Morrison, “Mental Illness in the Family,” in Helping and Healing Families: Principles and Practices Inspired by “The Family: A Proclamation to the World,” ed. Craig H. Hart et al. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2005), 288–94.

[11] John W. Williams Jr. et al., “Primary Care Physicians’ Approach to Depressive Disorders: Effects of Physician Specialty and Practice Structure,” Archives of Family Medicine 8, no. 1 (1999): 58–67.

[12] Jay C. Fournier et al., “Antidepressant Drug Effects and Depression Severity: A Patient-Level Meta-Analysis,” JAMA 303, no. 1 (2010): 47–53.

[13] David M. Stein and Michael J. Lambert, “Graduate Training in Psychotherapy: Are Therapy Outcomes Enhanced?,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 63, no. 2 (1995): 182–196.

[14] Michael J. Lambert, “The Efficacy and Effectiveness of Psychotherapy,” in Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 5th ed., ed. Michael J. Lambert (New York: Wiley, 2004), 141.

[15] Gary M. Burlingame and Debra Theobald McClendon, “Group Psychotherapy,” in Twenty-First Century Psychotherapies: Contemporary Approaches to Theory and Practice, ed. Jay L. Lebow (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2008), 354.

[16] Lambert, “Efficacy and Effectiveness,” 156.

[17] Michael J. Lambert et al., Administration and Scoring Manual for the Outcome Questionnaire (OQ 45.2) (Wilmington, DE: American Professional Credentialing Services, 1996); Michael J. Lambert et al., “The Reliability and Validity of the Outcome Questionnaire,” Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy 3, no. 4 (1996): 249–58.

[18] Lambert, “The Efficacy and Effectiveness of Psychotherapy,” 168.

[19] Donald F. Walker et al., “Religious Commitment and Expectations about Psychotherapy among Christian Clients,” Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 3, no. 2 (2011): 98–114.

[20] L. Rebecca Propst et al., “Comparative Efficacy of Religious and Nonreligious Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for the Treatment of Clinical Depression in Religious Individuals,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 60, no. 1 (1992): 102.

[21] Jeffrey R. Holland, “Like a Broken Vessel,” Ensign, November 2013, 42.