What Had Gone Before

Virginia Hatch Romney and Richard O. Cowan, The Colonia Juárez Temple: A Prophet’s Inspiration (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 1-15.

The story of the Colonia Juárez Chihuahua Temple has its roots in American Latter-day Saint history. Since The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was organized in 1830, its members were continually on the move. These Saints traveled from upstate New York, to Ohio, to Missouri, to Nauvoo, across the Mississippi to Winter Quarters, and finally to the Great Salt Lake. These moves were generally made in response to persecution and mob action. Each time, there were those who said, in effect, “I’ve had enough. I’m going to stay here and let the rest move on.” At each place there were those who fell by the wayside while the faithful continued forward. Thus these persecutions and movements served as a refiner’s fire. Those who reached the valley had been weighed in the balance and were not found wanting (see Daniel 5:27).

President Brigham Young, however, understood that the Salt Lake area was not the final resting place for some of the Saints. Settlers were called on colonizing missions, and once again they were on the move to begin scores of new communities in the north and south. For many, not even these new locations were the final destination.

New Beginnings in Mexico

In 1874 President Young called Daniel W. Jones and Henry Brizzee on a mission to Mexico. In the autumn of the following year, Jones and others entered Mexico at El Paso. Their purpose was twofold: to preach the gospel and to look for possible colonization sites. After preaching in Chihuahua City, they headed home in the spring. They visited the Paquimé ruins on the Casas Grandes River, thus becoming the first Latter-day Saints to see the area where the colonies would later be established. In 1879 Church leaders assigned Elder Moses Thatcher of the Quorum of the Twelve to open a mission in Mexico. At Mexico City on January 25, 1880, he dedicated the land for the preaching of the gospel. Then on April 6 of the following year, Elder Thatcher and a few others ascended the slopes of Mount Popocatépetl, held a conference, and once again blessed the land for preaching and colonizing.[1]

The 1880s brought intense persecution of Saints in Utah who had entered the practice of plural marriage, and many men were imprisoned. In 1885 President John Taylor, Brigham Young’s successor, announced that a gathering place had been designated near the Casas Grandes River. It was to serve as a place of refuge for many who would not abandon their plural families. He explained that the colonies would also serve a “more enduring” purpose as “a focal point for spreading the gospel in Mexico.”[2] The first colonizers left Arizona in February 1885 and once again undertook a new beginning.[3]

A tract of land was found, and several hundred americanos set up camp two miles north of Ascención until papers could be finalized. However, when legal ownership of the land was questioned, their arrangements fell through. Other possible locations were found. In the meantime, General Carlos Fuero, acting governor of Chihuahua, sent the new immigrants an expulsion order. In the colonists’ efforts to revoke this order, they were told that Americans’ colonizing Mexican lands had already cost Mexico the state of Texas. The governor’s order was revoked by higher authorities, however, and lands were eventually secured. Mexican president Porfirio Díaz favored foreign investment to help develop his nation. He stressed that not only were the Latter-day Saint immigrants welcome, but they were urged to stay and help build up the country.

Over three thousand people made their way into Mexico to begin anew. Primitive conditions, epidemics, and discouragement all took their toll, but within a few years, eight colonies were established in two Mexican states. In 1885 Colonias Díaz, Juárez, and Pacheco were founded in Chihuahua; Colonia Dublán followed in 1888, and Colonias García and Chuichupa in 1894. In Sonora, Colonia Oaxaca was organized in 1892, and Colonia Morelos in 1899.

Townsites were selected, rivers dammed, canals dug, farms and orchards planted, and permanent homes established. The progress of the new colonists was impressive during the next few years. They had their own blacksmith; tannery; saddle, leather, shoe, and carpentry shops; sawmills; grist mills; dairy and egg farm; and lime kiln. Mercantile co-ops were established. Apostles Moses Thatcher, George Teasdale, and Erastus Snow were instrumental in helping the colonists get settled. Elder Thatcher told the Saints that they were a people of destiny with a promising future.

Colonia Juárez looked much like a southern Utah town.

Colonia Juárez looked much like a southern Utah town.

But water—there was never enough. The river in Colonia Juárez dried up that first summer and threatened to end the success of the colonists. On May 3, 1886, following fasting and prayer, an earthquake struck the area, causing fissures in the canyon walls along the river that released additional water.

Before 1895 the Latter-day Saint colonies in Mexico were under the jurisdiction of the Mexican Mission. On December 9 of that year, however, the Juárez Stake was organized with Anthony W. Ivins as president. This was the first stake organized in Mexico and the second stake established outside of the United States (the Alberta Canada Stake having been organized six months earlier). As an increasing number of Hispanic neighbors joined the Church, the first Spanish-speaking branch in the stake was created in about 1909, and Toribio Ontiveros became the first native Mexican to serve as branch president. In 1952 this branch became the Dublán Second Ward.

From the beginning, education and worship had been foremost in the colonists’ minds. In each colony, a crude building was erected and became the first schoolhouse as well as the center of religious services. In 1897, as a result of the colonists’ desire for better education for their children, the Juárez Stake Academy (JSA), was established, and Guy C. Wilson became its first principal. Beginning with the Brigham Young Academy in Provo, Utah, the Church had established about thirty high school academies. The JSA was the last of these to survive. In its first year, 225 students enrolled. In 1901, JSA produced its first six graduates.

By 1910, twenty-five years after the arrival of these faithful pioneers, and despite much hardship, they had succeeded in making the desert “blossom as a rose” (Isaiah 35:1). The outbreak of the Mexican Revolution, however, would permanently change their lives. The colonists desired to be loyal to President Díaz because of his support in making land available to them and for his encouragement to stay and help develop the country. However, they were also sympathetic to the cause of the revolutionaries, whose standard proclaimed “Land and Liberty!” As a result, the colonists decided to remain neutral.

Even with this declared neutrality, the Latter-day Saint colonies were an excellent source of supplies for the revolutionary troops. At first the troops paid for their purchase of horses, saddles, shoes, flour, and other food supplies, but later offered only receipts or promissory notes. Ultimately, goods were simply expropriated. The Saints were threatened and robbed, and a few were even killed.

On July 26, 1912, the women and children were evacuated by train to El Paso, taking with them what few possessions they could carry. “We got a cattle car,” Lorna Call Alder remembered. “We put our trunks and bedding on top and we just sat on it. It was very, very slow and tiresome.”[4] The men and boys followed shortly thereafter, driving what cattle and horses they could, entering the United States via Hachita, New Mexico. Most of them found temporary shelter at El Paso in “sheds at a deserted lumber yard” or on “the upper floor of an old building” with a corrugated iron roof that became “red hot under the burning rays of a southern sun.”[5] Within several weeks, some of the more daring colonists returned to their homes to find them raided: stock was gone, and gardens and pantries were left empty. Under the wise direction of local Church leaders, they weathered the next seven years, some of them having to evacuate up to three times.

When the situation improved, only about a third of the original colonists returned to begin anew. They were only able to reestablish five of the original eight colonies. Isolation, transportation difficulties, and the lack of schools eventually caused all but two of the colonies to be abandoned. By the mid-twentieth century, only Colonia Juárez and Colonia Dublán remained as viable agricultural communities, and these two continued as strong centers of Latter-day Saint activity. Still, the colonies’ isolation was an asset, and the faithful Saints were able to create an environment that encouraged living the gospel. “It’s a lot easier to do what’s right because most of your friends are doing it too,” Brandon Hatch, a young man in Colonia Dublán, remarked.[6]

Many felt the colonies were a great place to live and to raise their children. Colonists have a saying, “You can take the boys out of the colonies, but you can never take the colonies out of the boys.” To maintain this atmosphere, they believed, “We must never become complacent. Our wellbeing—spiritually and otherwise—lies in keeping the commandments.”[7]

Progress in the Colonies

In 1956 the colonies’ relative isolation came to an end when the government built a paved road from the Chihuahua Highway into Nuevo Casas Grandes and then on to Colonia Juárez. In the early 1970s another highway was built from Ciudad Juárez directly to Nuevo Casas Grandes. This facilitated the colonists’ trips to El Paso, where they went to buy goods not available locally.

The new highways also benefited the colonists’ expanding fruit business. Earlier, the government had invited them to participate in state and national fairs, and at this time they did. They won several ribbons for their impressive displays of fruit, grain, vegetables, canned produce, and leather goods. They were rewarded for their efforts one year by receiving the prize for the best exhibition at the fair.

The climate, elevation, and soil produced excellent apples and pears. The growers’ recognition at these fairs began the development of Mexico’s first commercial apple business. Many colonists began to specialize in growing fruit. In 1975 the growers of the area, Church members and nonmembers alike, united and formed a fruit-grower co-op. They named their venture Empacadora Paquimé, after the name of the Indian tribe that had once inhabited the area. This business refrigerated, packed, and marketed their fruit all over Mexico. It was visited and consulted by other growers and government officials to learn the group’s secrets of success.

Mexico’s president, Carlos Salinas Gortari, visited Colonia Juárez on November 11, 1989, with the intent of meeting the Saints. Many were invited to attend a banquet in his honor along with Chihuahua governor Fernando Baeza. The dignitaries were very impressed with the academy’s band performance, homemade turkey dinner, candy, gifts, displays, and general respect extended to them. The president was so impressed that he invited those present to a dinner at Los Piños (the Pines), also called the “Mexican White House” by some. Three years later on September 22, 1992, about 270 members of the Church accepted his invitation and traveled to Mexico City to dine with President Salinas. Many attended the Mexico City Temple, and the youth were able to perform baptisms for the dead.

Colonia Juárez in its valley setting (above) and Colonia Dublán in the flatlands (below), October 1998. Courtesy of Marvin Longhurst.

Colonia Juárez in its valley setting (above) and Colonia Dublán in the flatlands (below), October 1998. Courtesy of Marvin Longhurst.

The colonists’ contact with national political leaders continued. History was made in 1997 when Jeffrey Max Jones, a member of the Dublán Ward, was elected as diputado federal for his district in Chihuahua. He was the first Anglo-Saxon to be elected to the Mexican Congress, becoming one of five Latter-day Saints serving in that body. After being a congressman, Jones served as a senator. Currently he is serving in President Calderon’s cabinet in Mexico City as undersecretary of agriculture for the development of agrobusiness.

Meanwhile, as Church growth accelerated worldwide, the names of stakes (including those in Mexico) had been modified in 1974 to more completely reflect their location. Therefore the Juárez Stake became known as the Colonia Juárez Mexico Stake. This was a time of rapid growth for the Church in the colonies region as an increasing number of converts from the local area were baptized. This growth increasingly added Hispanic Latter-day Saints to the earlier groups of Anglo colonists. Between 1968 and 1979 the number of Church units in Mexico mushroomed from six to sixteen. On February 25, 1990, this stake was divided to form the new Colonia Dublán Mexico Stake. The Colonia Juárez stake retained six wards and one branch, having a membership of about 2,500, while the Colonia Dublán stake consisted of six wards and four branches, with a membership of 2,090. Each of the two stakes had only one English-speaking ward, with a combined membership of about 450; the rest of the units were Spanish speaking. Meredith I. Romney remained president of the Colonia Juárez stake, and Carl L. Call became president of the new Colonia Dublán stake.

Education continued to be important to the Saints in the colonies. In the 1980s, when the Church announced that it was closing most of its schools in Mexico, the local Saints were willing to assume the rather sizable financial responsibility to keep the elementary schools in Colonia Dublán and Colonia Juárez open. Some Saints from other parts of Mexico moved to the colonies to give their children the opportunity to have a better education. These newcomers, together with converts to the Church from the local area, increasingly added Hispanic Latter-day Saints to the earlier groups of Anglo colonists.

On the secondary level, the Church continued to support the Juárez Stake Academy, which had become known as the Academia Juárez; its curriculum had for some time been incorporated with the Mexican government education system. It is the only one of the original academies established by the Church during the nineteenth century that still serves its original function (a few of the others having become colleges or universities but the majority having been abandoned). Annual enrollment during the 1990s surpassed four hundred students. The largest graduating class to date was in 1996, with ninety-two graduates. During this decade, the Church invested a large amount of money to remodel the school buildings and grounds. The resulting campus became a great asset to the Church and surrounding communities.

The Academy’s Centennial

Within a period of a dozen years, three important centennials were celebrated: 1985, the founding of the colonies; 1995, organization of the original stake; and 1997, the establishment of the Juárez Stake Academy. The last of these events, celebrated June 2–6, would prove to be the most significant in terms of its future impact. The academy centennial theme was “One Hundred Years in Excellence.” The Church Educational System produced a special video film for the occasion entitled Juárez Academy: Seedbed of the Lord, 1897–1997 Centennial pointing out that nine General Authorities, three Area Seventies, thirteen regional representatives, more than eighty mission presidents, and eight temple presidents could trace their roots to the colonies and the academy. The General Authorities included Anthony W. Ivins and Marion G. Romney, who served in the First Presidency, as well as Rey L. Pratt, Antoine R. Ivins, Waldo P. Call, Jorge Rojas Ornelas, Jerald L. Taylor, Eran A. Call, and Robert J. Whetten of the Seventy.[8] Since this film was produced, these totals have continued to grow (see appendix B).

Centennial activities included a band concert, parade, pageant, class and family reunions, graduation exercises, a fireside, barbecue, alumni talent show, grand ball, and fireworks. A receptionist area and museum were set up in the grade school, where books, souvenirs, and food were also available. The JSA centennial would have a lasting impact on the people because of the visit of the President of the Church, Gordon B. Hinckley, who had come specifically to rededicate the refurbished academy buildings.[9]

President Gordon B. Hinckley at Academia Juárez. Courtesy John Hart.

President Gordon B. Hinckley at Academia Juárez. Courtesy John Hart.

A reported 5,500 people gathered for the Thursday evening fireside held in a large tent set up on the grounds. Elder Eran A. Call of the Seventy, a JSA graduate, was in attendance.[10] Elder Call reminisced about his experiences at the academy and spoke about the impressive contributions the colonies had made to Mexico and the Church. President Hinckley then spoke:

I am satisfied [your forebears] must have been led here by the inspiration of the Almighty. I believe with all my heart that God was watching over them and that they planted here not only a colony, but a future for the work of the Lord in these narrow valleys. I thank the Lord for the faith and the testimony and the conviction of the people of Colonia Juárez and Colonia Dublán. God bless you for your tremendous contribution, for your great faith, for your love of the Lord. . . . You seem to be so far away from everybody, but your very isolation has been your strength. . . . You have helped one another in times of trouble and distress. . . . You have become as one great family. . . . Keep it up. . . . Live as you have lived in the past.

And now there are being added to your number these marvelous and wonderful Latter-day Saints who are of Mexican descent, who are natives of this nation and of the people of this land. Build them and strengthen them. They are a wonderful people. I want to tell you how much I love you. I mean that. I love you.

President Gordon B. Hinckley greeting the congregation at the Centennial Fireside. Courtesy of John Hart.

President Gordon B. Hinckley greeting the congregation at the Centennial Fireside. Courtesy of John Hart.

President Hinckley blessed the congregation and admonished them to continue to be faithful, reminding them that they constituted an island of faith in a great land of opportunity.[11] (For the complete text, see appendix A.)

Little did anyone know what would follow this declaration, including the erection of a sacred temple, which would surprise but please the people whom President Hinckley had just praised so highly. The significance of this development can best be appreciated in light of the Saints’ long-standing emphasis on temples.

A Temple-Building People

Latter-day Saints have been a temple-building and temple-attending people.[12] For them, temples are more than ordinary meetinghouses. They truly are houses of the Lord, where, through holy ordinances and instructions, the faithful learn of their eternal destiny and enter into sacred covenants with God.

At Kirtland, Ohio, the Saints overcame poverty and persecution to build their first temple. Their sacrifice brought forth the blessings of heaven. The Saints who met in the temple enjoyed a rich outpouring of spiritual gifts, including prophecy, speaking in tongues, and visions of angels. Joseph Smith declared that “this was a time of rejoicing long to be remembered.”[13] These events climaxed with the daylong dedication of the temple on March 27, 1836. One week later, the Prophet recorded that Jesus Christ appeared in glory to accept the temple and that Elijah the prophet restored the sealing keys “to turn the hearts of the fathers to the children, and the children to the fathers” (D&C 110:15).

Kirtland Temple, dedicated 1836. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Kirtland Temple, dedicated 1836. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Sacred temple ordinances were revealed while the second temple was being built at Nauvoo, Illinois. In 1840 Joseph Smith taught the Saints that they could be baptized in behalf of the dead (see 1 Corinthians 15:29). They eagerly went into the Mississippi River to perform this ordinance, thus making gospel blessings available to their loved ones who had died without this opportunity. In 1842 the Prophet presented the endowment which was a “course of instructions” describing the path that leads back into the presence of God and “setting forth the keys” by which this can be achieved.[14] Soon couples were being sealed, or married with solemn covenants “for time and for all eternity” (D&C 132:7; see also vv. 8–20). These teachings and promises enabled the Saints to understand their true identity and potential as children of God.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, the Latter-day Saints built four more temples in Utah, including the great temple at Salt Lake City. These larger buildings included beautiful rooms with murals on their walls.

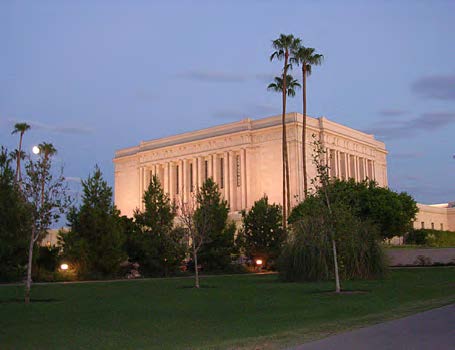

Four more temples were built during the first half of the twentieth century—in Hawaii, Alberta, Arizona, and Idaho—reflecting the Church’s expansion beyond Utah. These temples included a cafeteria for the convenience of temple patrons and workers who often needed to be in the temple over mealtimes and laundering facilities where rented temple clothing was cared for.

Salt Lake Temple, dedicated 1893. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Salt Lake Temple, dedicated 1893. Courtesy of Church History Library.

At least two Church leaders considered the possibility of temples in Mexico. At a general conference in 1915, President Joseph F. Smith lamented, “We were in hopes, not many years ago of being able to build another temple near the borders of the United States, in Mexico; but that nation’s unfortunate people, oppressed by rulers ambitious for power at the cost of the lives of their fellowmen, have driven out or expelled practically our people from their land.”[15] Then during a 1947 tour of the Mexican Mission, Elder Spencer W. Kimball envisioned its destiny: “I saw a temple and expect to see it filled with men and women.”[16] At that time, there were no wards and stakes in Mexico outside of the colonies.

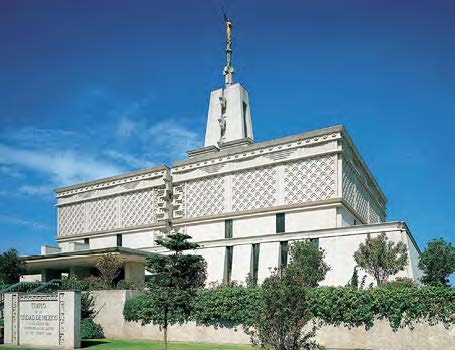

The 1950s brought the first overseas temples—Switzerland, New Zealand, and England. During the early 1980s, two dozen temples were dedicated. These included smaller structures in the Pacific Islands, Asia, Europe, Africa, and South America. A larger temple was constructed at Mexico City. Dedicated in December 1983, it became the largest temple outside of the United States and fifth largest in the world.

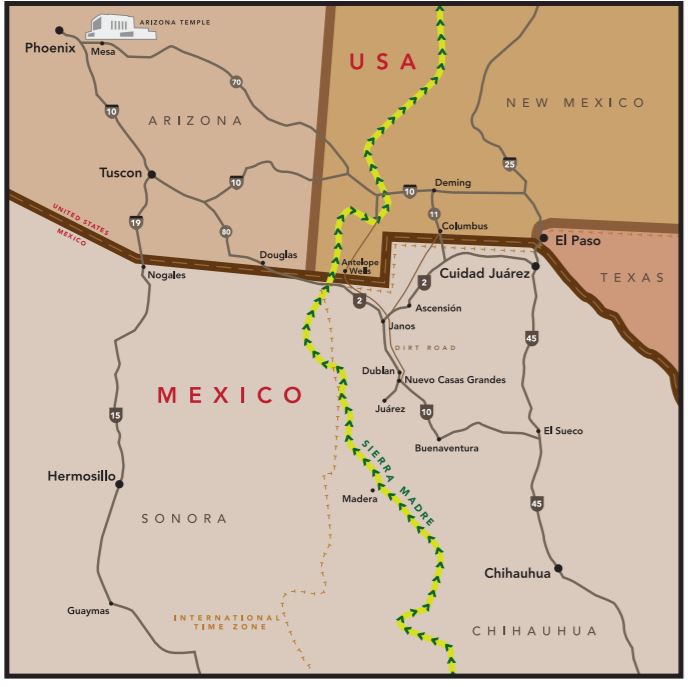

The temple at Mesa, Arizona, dedicated in 1927, would be the closest to the colonies in Mexico for over seventy years. At first the colonists had to travel by dirt roads part of the way, and the journey to Mesa often took a full day. Even when the paved highway reached the colonies in the 1950s, it came via Sueco and Buenaventura to the southeast, so the route to the temple was still rather roundabout. After the more direct road to El Paso was paved in the 1970s, and especially when the highway was opened during the 1980s across the northwestern mountains to Douglas, Arizona, driving time was shortened significantly. (See the map in this chapter.) Still, it took six to seven hours to reach Mesa. In contrast, the bus trip from the colonies to the temple in Mexico City, over one thousand miles, required at least sixteen hours. In addition to long trips of more than six or seven hours to get to a temple, the trip from the colonies involved crossing an international border, which sometimes involved expensive and time-consuming paperwork. Furthermore, many of the members were quite poor and could not afford such a trip.

Mesa Arizona Temple, dedicated 1927. Courtesy of Tyler Nebeker.

Mesa Arizona Temple, dedicated 1927. Courtesy of Tyler Nebeker.

Forty-seven temples were in service when Gordon B. Hinckley became President of the Church in 1995. For at least two decades, he had been concerned with making temple blessings more readily available to the scattered international Saints. “Too many times he had organized stakes in various areas of the world in which few of the brethren interviewed for leadership positions had been to the temple. He found himself wondering if there weren’t a way to build smaller, less expensive temples and to build more of them throughout the world.”[17] He discussed these concerns with Church President Harold B. Lee as early as the 1970s. His 1997 visit to the Mormon colonies in Mexico inspired the answer he was seeking.

Mexico City México Temple, dedicated 1983. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Mexico City México Temple, dedicated 1983. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Colonies’ Milestones

1875: First Latter-day Saint missionaries enter Mexico. One of their purposes was to scout out possible colony sites to be refuges from persecution.

1885: Colonia Juárez is established.

1888: Colonia Dublán is established.

1895: Juárez Stake is organized.

1897: Juárez Stake Academy is founded.

1912: Colonists flee during Mexican revolution; only about one-third return.

1927: Mesa Arizona Temple is dedicated; it is the closest temple to colonies at this time.

1956: First paved highway reaches colonies from El Paso.

1990: Stake divided to form new Colonia Dublán Stake.

1997: President Gordon B. Hinckley receives inspiration for small temples following visit to the colonies.

1999: Colonia Juárez Chihuahua Temple is dedicated.

Notes

[1] Importantes Eventos en Historia del Mormonismo en Mexico 2003, (Mexico City: El Museo de História del Mormonismo en Mexico, 2003); Rey L. Pratt, “History of the Mexican Mission,” Improvement Era, April 1912, 487.

[2] LaVon B. Whetten and Don L. Searle, “Once a Haven, Still a Home,” Ensign, August 1985, 43.

[3] Good sources include B. Carmon Hardy, “The Mormon Colonies of Northern Mexico: A History, 1885–1912” (PhD diss., Wayne State University, 1963); Thomas C. Romney, The Mormon Colonies in Mexico (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1938; University of Utah Press, 2005); Nelle S. Hatch, Colonia Juárez: An Intimate Account of a Mormon Village (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1954); Hannah Skousen Call, The History of Colonia Dublán (n.p., c. 1985); LaVon B. Whetten, The Mormon Colonies in Mexico: Commemorating 100 Years (Deming, NM: Colony Specialities, 1985); Lorna Call Alder and William G. Hartley, Anson Bowen Call: Bishop of Colonia Dublán (n.p., 2007); LaMond Tullis, Mormons in Mexico: The Dynamics of Faith and Culture (Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 1987).

[4] John L. Hart, “Faith Learned in Colonies Fosters Long Life of Service,” Church News, November 15, 1997, 7.

[5] Romney, Mormon Colonies, 189.

[6] Lisa M. Grover, “Trail of Faith,” New Era, June 1997, 22.

[7] Whetten and Searle, “Once a Haven,” 45.

[8] “Academy Exports Leaders across Church,” Church News, June 14, 1997, 7.

[9] John Whetten, e-mail to Richard Cowan, March 15, 2007.

[10] John L. Hart, “Bueno! Juárez Academy Centennial,” Church News, June 14, 1997, 3.

[11] Gordon B. Hinckley remarks at Academia Juárez Centennial Fireside, June 5, 1997; typescript in Virginia Romney’s possession.

[12] For a discussion of Latter-day Saint temples, see James E. Talmage, The House of the Lord (Salt Lake City, Bookcraft, 1962); Boyd K. Packer, The Holy Temple (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1980); Richard O. Cowan, Temples to Dot the Earth (Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, 1997).

[13] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1948), 2:392.

[14] Talmage, House of the Lord, 99–100; Smith, History of the Church, 5:1–2.

[15] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, October 1915, 8.

[16] Dell Van Orden, “Emotional Farewell in Mexico,” Church News, February 19, 1977, 3.

[17] Sheri L. Dew, Go Forward with Faith: The Biography of Gordon B. Hinckley (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1996), 325.