John Taylor: Beyond “A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief”

Jeffrey N. Walker

Jeffrey N. Walker, “John Taylor: Beyond ‘A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief,’” in

Champion of Liberty: John Taylor, ed. Mary Jane Woodger (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 63–110.

Jeffrey N. Walker was manager and coeditor of the Legal and Business Series for the Joseph Smith Papers Project and an adjunct professor in the Church History and Doctrine Department and the J. Reuben Clark Law School at Brigham Young University when this was published.

John Taylor chose to remain that fateful day at Carthage with Joseph and Hyrum Smith. The scene of these men in the jail’s upstairs bedroom referred to as the “debtor’s cell” is forever etched in Latter-day Saint memory. Little is remembered about what was discussed during that long afternoon in June 1844 between these leaders. Scriptures were read. Legal strategies were discussed. A few letters were drafted. Time was essentially suspended as the men waited for a legal hearing to determine whether the prophet and his brother would be released on bail. John Taylor recounted of that day, “All of us felt unusually dull and languid, with a remarkable depression of spirits.”[1] The humid afternoon heat led the men to remove their jackets, and Taylor sang a tune recently introduced in Nauvoo, “A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief.” The lyrics embody the Savior’s teaching in Matthew 25:40: “Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.” How could they have known at the time that this song would forever become connected to the Martyrdom that occurred later that day?

Elder John Taylor accompanied Joseph and Hyrum Smith to Carthage Jail on June 25, 1844. He stayed with them two more days. In the afternoon of June 27, he reluctantly sang “A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief.” Following Elder Taylor’s second rendition of the hymn, an armed mob stormed the cell, killing Joseph and Hyrum and leaving John Taylor seriously wounded. (Photo by Kenneth R. Mays)

Elder John Taylor accompanied Joseph and Hyrum Smith to Carthage Jail on June 25, 1844. He stayed with them two more days. In the afternoon of June 27, he reluctantly sang “A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief.” Following Elder Taylor’s second rendition of the hymn, an armed mob stormed the cell, killing Joseph and Hyrum and leaving John Taylor seriously wounded. (Photo by Kenneth R. Mays)

Defender of the Faith

To understand what brought John Taylor to be at the vortex of the Restoration, one must place him within the context of his meteoric rise in the Church. Born in England on November 1, 1808, John Taylor immigrated to Toronto in 1832, he having become a skilled carpenter[2] and a staunch Methodist.[3] In Canada, Taylor continued to pursue his religious convictions by becoming a traveling preacher.[4] There he met and married Leonora Cannon[5] and started a family. In the ensuing years, Taylor worked during the week as a carpenter to support his growing family and preached Methodism on Sundays. As his faith matured, so did his questioning over doctrine.[6] In the midst of his religious struggles he was introduced to Elder Parley P. Pratt, who was serving a mission in Upper Canada in 1836. Taylor and Pratt would almost immediately share a pulpit,[7] with Taylor raising doctrinal questions about what he saw as missing elements of the gospel and Pratt describing the restoration of all things through the Prophet Joseph Smith. Taylor was captivated by the message,[8] and shortly thereafter he and his wife were baptized.[9] Others in the congregation, including Joseph Fielding, were also baptized. Before leaving his mission, Pratt ordained Taylor to be the presiding elder in Canada.

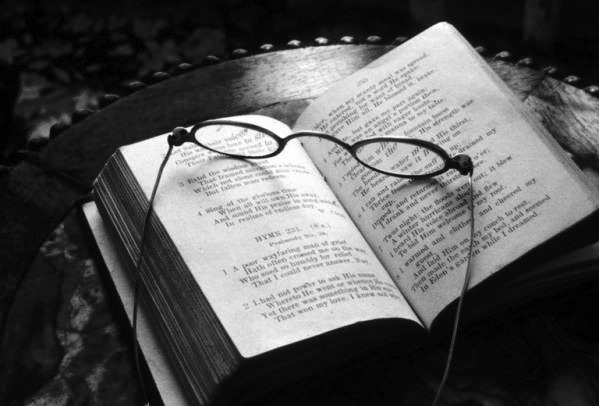

John Taylor’s glasses and 1852 edition of a Latter-day Saint hymnal. (© 2002 Brigham Young University. All rights reserved.)

John Taylor’s glasses and 1852 edition of a Latter-day Saint hymnal. (© 2002 Brigham Young University. All rights reserved.)

John Taylor first met the Prophet Joseph Smith in Kirtland in March 1837 and was called upon to defend him in the midst of dissension.[10] In August 1837, Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, and Thomas Marsh traveled to Canada to hold conferences, and Smith ordained Taylor a high priest.[11]

By fall 1837, John Taylor learned that he had been called as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles[12] and was asked to move to Far West, Missouri.[13] Taylor and his family arrived in Missouri by the end of summer 1838, in time to experience the persecutions that followed the Saints, including the incarceration of Joseph Smith and other leaders at Richmond and Liberty. His ordination as a member of the Twelve in December 1838[14] was coupled with responsibilities to assist in moving Church members from Missouri to Illinois in response to Governor Lilburn W. Boggs’s extermination order.[15]

He returned to Missouri with other members of the Twelve in late April 1839 to fulfill the revelation pertaining to their proselyting mission to England. This revelation noted that their mission was to commence at the temple site in Far West.[16] Traveling back through Quincy, Illinois, where the Saints had temporarily settled, he participated in the selection of Commerce, Illinois, and Montrose, Iowa, as permanent sites for the Saints to settle.[17] Leaving his family poor and sick[18] in abandoned army barracks in Montrose, Iowa, he traveled east with Wilford Woodruff. In Springfield, Illinois, Taylor published 1,500 copies of a pamphlet he wrote about the Missouri persecutions.[19] His travels to New York and then to England are a testament to his tenacity and faith matched only by his missionary efforts in England, Ireland, and the Isle of Man.[20] After nearly two years away, John Taylor and six others of the Twelve serving in England sailed home in April 1841. President Brigham Young summarized their missionary efforts: “We landed in the spring of 1840, as strangers in a strange land and penniless, but through the mercy of God we have gained many friends, established churches in almost every noted town and city in the Kingdom of Great Britain, baptized between seven and eight thousand, printed 5000 Books of Mormon, 3000 Hymn books, 2,500 volumes of the Millennial Star, and 50,000 tracts, and emigrated to Zion 1000 souls.”[21]

Political Leader and Confidant

Reaching Nauvoo in July 1841, Taylor and his fellow apostolic missionaries found a thriving and vibrant city. Literally hundreds of buildings were under construction. Such expansion was coupled with a city charter for Nauvoo which was approved by the legislature, signed by the governor, and made effective in February 1841. The charter gave broad rights for the administration of Nauvoo, including the creation of a municipal government, judiciary, university, and militia. Taylor spent the next three years not only as a prominent Church leader and close confidant to the Prophet Joseph Smith but also as an important political, civic, business, and military leader. These cumulative sacred and secular roles inescapably led him to Carthage that fateful day.

Taylor’s return to Nauvoo coincided with a concerted expansion in the role and duties of the Quorum of the Twelve. In August 1841, the Prophet Joseph Smith taught “that the time had come when the Twelve should be called upon to stand in their place next to the First Presidency.”[22] As a member of this quorum, Taylor was also part of the inner circle of doctrinal development, including the introduction of polygamy. Taylor found polygamy, in his words, “the most revolting, perhaps, of anything that could be conceived. . . . I had always entertained strict ideas of virtue, and I felt as a married man that this was to me . . . an appalling thing to do. The idea of my going and asking a young lady to be married to me, when I had already a wife!”[23] Yet, despite such strong feelings, Taylor evidenced his loyalty to Joseph Smith by taking his first plural wife in secret in December 1843.[24]

As the responsibilities of the Twelve expanded to encompass immigration of the Saints (the fruition of the “gathering”), missionary efforts, financial issues, and expanding the business affairs of the Church, Taylor found himself traveling, presiding, and organizing congregations of the Church. Taylor was also chosen to the Saints’ grievances against the Missourians, the Saints’ first effort to petition the federal government for assistance for losses sustained in Missouri proved unsuccessful.[25] In this role Taylor emerged as a spokesperson for the Church’s legal and financial interests.

These political efforts served as a catalyst for Taylor’s increased role in the local government of Nauvoo. In September 1841, Taylor was appointed a member of the board of regents for the University of the City of Nauvoo. By January 1842, Taylor joined the Nauvoo city council, serving on the powerful police committee.[26] Taylor was also appointed judge advocate with the rank of colonel in the Nauvoo Legion, a position that made him the public prosecutor in military affairs.[27]

Editor and Business Manager

Taylor’s literary skills were tapped in November 1841 when he became an editor for the Times and Seasons,[28] and in November 1842 when he became the editor of the Wasp (subsequently renamed the Nauvoo Neighbor).[29] Wilford Woodruff partnered with Taylor as the business manager for these publications. To increase revenue, Taylor and Woodruff expanded their operations to include freelance printing, bookbinding, and bookselling. By January 1844, Taylor acquired the printing house and fixtures—including the presses, type, and bindery—from Joseph Smith.[30]

Taylor’s talents were again called upon as Joseph Smith fought his legal battles against the Missourians’ extradition attempts. After the failed assassination of former governor Lilburn W. Boggs, Missouri’s governor sought the extradition of Joseph Smith as an accessory before the fact.[31] When attempts were thwarted by the use of writs of habeas corpus,[32] Joseph Smith was forced to go into hiding to prevent possible kidnapping or otherwise illegal arrest. Based on legal advice from several prominent lawyers and judges,[33] Joseph agreed to have the matter heard before federal district judge Nathaniel Pope in Springfield, Illinois.

Joseph traveled to Springfield in December 1942 with an entourage of the leading men of Nauvoo, including John Taylor. One local newspaper reported that Joseph Smith “was attended by a retinue of some fifteen or twenty of as fine looking men as my eyes ever beheld.”[34] The Speaker of the House of Representatives even offered the Representatives Hall to the Saints for their Sunday services.[35] John Taylor was asked by Joseph Smith to give one of two sermons to a packed congregation.[36]

After a two-day trial, Judge Pope ruled that the extradition request from Missouri’s governor was not supported by sufficient evidence and released Joseph Smith. Taylor published the court’s ruling in the Times and Seasons on January 4, 1843 and the Wasp on January 28, 1843..[37]

By summer 1843, Taylor once again became intimately involved in Joseph Smith’s legal entanglements as new charges of treason were filed in Missouri, resulting in Missouri’s governor again seeking the extradition of Smith. This time Taylor used his position as editor of the Nauvoo Neighbor and the Times and Seasons to inform the citizens of Nauvoo about the nature of the events and to vigorously defend Joseph Smith. In the July 1, 1843, edition of the Times and Seasons, Taylor penned: “It is impossible that the State of Missouri should do justice with her coffers groaning with the spoils of the oppressed and her hands yet reeking with the blood of the innocent. Shall she yet gorge her bloody maw with other victims? Shall Joseph Smith be given into her hands illegally? Never! No Never!! NO NEVER!!!”[38]

In the July 5, 1843, issue of the Nauvoo Neighbor, Taylor further staked out his position: “Without entering here into the particulars of the bloody deeds, the high-handed oppression, the unconstitutional acts, the deadly and malicious hate, the numerous murders and the wholesale robberies of that people, we will proceed to notice one of the late acts of Missouri, or of the governor of that state, towards us. We allude to the late arrest of Joseph Smith.”[39]

Both sides of the dispute used the full arsenal of legal maneuvers. Arrests begat counterarrests. Claims begat counter-claims. Joseph Smith described the outcome: “I was a prisoner in the hands of Reynolds, the agent of Missouri, and Wilson, his assistant. They were prisoners in the hands of Sheriff Campbell, who had delivered the whole of us into the hands of Colonel Markham, guarded by my friends, so that none of us could escape.”[40] The ensuing trial before the Nauvoo Municipal Court exonerated Joseph Smith. Taylor chronicled the events and outcome in his papers.

Political Adviser

Taylor shifted efforts in the fall of 1843 to the upcoming presidential campaign. In the October 1, 1843, issue of Times and Seasons, he initiated his efforts by using the press at his disposal to raise the question, “Who shall be our next president?” Having both lived through and participated in the aftermath of the persecutions in Missouri, Taylor was uniquely positioned to voice the concerns of the Mormons. He concluded his editorial, noting:

We make these remarks for the purpose of drawing the attention of our brethren to this subject, both at home and abroad; that we may fix upon the man who will be the most likely to render us assistance in obtaining redress for our grievances—and not only give our own votes, but use our influence to obtain others, and if the voice of suffering innocence will not sufficiently arouse the rulers of our nation to investigate our case, perhaps a vote of from fifty to one hundred thousand may rouse them from their lethargy. We shall fix upon the man of our choice, and notify our friends duly.[41]

From such editorials Taylor emerged as a leading spokesperson and adviser to Joseph Smith on political matters. This included assisting Smith in writing to each presidential candidate seeking support of the Saints’ cause,[42] to ultimately nominating him for the presidency in a lengthy editorial in the Times and Seasons. In February 1843, Taylor again raised the question, “Who shall be our next president?” This time he concluded:

Under these circumstances the question again arises, who shall we support? General Joseph Smith. A man of sterling worth and integrity and of enlarged views; a man who has raised himself from the humblest walks in life to stand at the head of a large, intelligent, respectable, and increasing society, that has spread not only in this land, but in distant nations; a man whose talents and genius, are of an exalted nature, and whose experience has rendered him every way adequate to the onerous duty. Honorable, fearless, and energetic, he would administer justice with an impartial hand, and magnify, and dignify the office of chief magistrate of this land; and we feel assured that there is not a man in the United States more competent for the task.[43]

As his presidential bid took form, Taylor was appointed not only to serve as Joseph Smith’s campaign manager but to remain in Nauvoo and utilize his newspapers as vehicles supporting the campaign. Joseph explained to John the year previous, “John Taylor, I believe you can do more good in the editorial department than preaching. You can write for thousands to read; while you can preach to but a few at a time. We have no one else we can trust the paper with.”[44]

Role in Nauvoo Expositor Incident

In his capacity as a member of the Nauvoo city council and specifically as a member of the police committee, Taylor participated in the municipal decisions pertaining to the controversial first edition of the Nauvoo Expositor in June 1844. As the owner, editor, and publisher of Nauvoo’s two newspapers—Times and Seasons and Nauvoo Neighbor—Taylor had both publishing expertise and business interest in evaluating the Nauvoo Expositor. As the campaign manager and political adviser to Joseph Smith’s presidential bid, Taylor was uniquely positioned to understand the political dynamics of the timing and focus of the Nauvoo Expositor. Finally, as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve, Taylor had a pivotal responsibility to protect the interests of the Church over many of the claims in the Nauvoo Expositor.

The single issue of the Nauvoo Expositor was published on June 7, 1844. This newspaper was published by a group of prominent civic and former Mormon leaders in Nauvoo. While it did contain advertising, poetry, a short story, a song, and some national news, the sting of the paper was a direct assault on Joseph and Hyrum Smith and the Church generally. These attacks were multifaceted to include financial, political, and religious claims. On the financial front the Nauvoo Expositor claimed that under the direction of Joseph Smith, the Church was financially exploiting the newly arriving immigrants. On the political front, it claimed that under the direction of Joseph Smith, unconstitutional ordinances were being passed in Nauvoo (including the expansive use of writs of habeas corpus) and a lack of separation between church and state (highlighted by Joseph Smith’s presidential bid and Hyrum Smith’s run for his brother William Smith’s seat in the Illinois legislature). Yet the most concerted attack in the Nauvoo Expositor came on the religious or moral front and centered on two doctrinal theses: the eternal potential of man to become like God and the private practice of polygamy. The overall objective of the Nauvoo Expositor was succinctly noted in its previously distributed prospectus that was reprinted in the paper:

The Expositor will be devoted to a general diffusion of useful knowledge, and its columns open for the admission of all courteous communications of a Religious, Moral, Social, Literary, or Political character. . . . A part of its columns will be devoted to a few primary objects, which the Publishers deem of vital importance to the public welfare. Their particular locality gives them a knowledge of the many gross abuses exercised under the pretended authorities of the Nauvoo City Charter, by the legislative authorities of said city; and the insupportable of the Ministerial powers in carrying out the unjust, illegal, and unconstitutional ordinances of the same. The publishers, therefore, deem it a sacred duty they owe to their country and their fellow citizens, to advocate, through the columns of the Expositor, the Unconditional Repeal of the Nauvoo City Charter.[45]

Reaction to the Nauvoo Expositor was immediate. Sidney Rigdon recalled, “The first number of this paper made its appearance, and it was inflammatory and abusive to an extreme. This raised the excitement to a degree beyond control, and threatened serious consequence.”[46] Taylor further explained:

Emboldened by the acts of those outside, the apostate ‘Mormons,’ associated with others, commenced the publication of a libellous paper in Nauvoo, called the Nauvoo Expositor. This paper not only reprinted from the others, but put in circulation the most libellous, false, and infamous reports concerning the citizens of Nauvoo, and especially the ladies. It was, however, no sooner put in circulation, than the indignation of the whole community was aroused; so much so, that they threatened its annihilation; and I do not believe that in any other city in the United States, if the same charges had been made against the citizens, it would have been permitted to remain one day. As it was among us, under these circumstances, it was thought best to convene the city council to take into consideration the adoption of some measures for its removal, as it was deemed better that this should be done legally than illegally.[47]

Taylor participated in meetings of the Nauvoo city council held the day after the publication of the Nauvoo Expositor, a Saturday, for six and a half hours and then again on the following Monday for seven and a half hours. The deliberations included examining the publishers and backers of the Nauvoo Expositor, as well as the content of the publication. The city council then turned their attention to legal options. Taylor recalled of these meetings, “Being a member of the city council, I well remember the feeling of responsibility that seemed to rest upon all present.”[48]

Under the leadership of Joseph Smith, the city council concluded that the publishers of the Nauvoo Expositor were guilty of libel and the paper itself was a public nuisance[49] and should be removed. Taylor recalled his participation in the process: “I arose and expressed my feelings frankly, as Joseph had done, and numbers of others followed in the same strain; and I think, but am not certain, that I made a motion for the removal of that press as a nuisance. This motion was finally put, and carried by all but one; and he conceded that the measure was just, but abstained through fear.”[50] Additional records detail Taylor’s participation in these deliberations:

Councilor Taylor said no city on earth would bear such slander, and he would not bear it, and was decidedly in favor of active measures. . . . Councilor Taylor continued—Wilson Law was President of this Council during the passage of many ordinances, and referred to the records. ‘William Law and [Sylvester] Emmons were members of the Council, and Emmons has never objected to any ordinance while in the Council, but has been more like a cipher, and is now become editor of a libelous paper, and is trying to destroy our charter and ordinances.’ He then read from the Constitution of the United States on the freedom of the press, and said—‘We are willing they should publish the truth; but it is unlawful to publish libels. The Expositor is a nuisance, and stinks in the nose of every honest man.’[51]

Based on the libelous nature of the paper and its propensity to, as Alderman Orson Spencer stated, “bring a mob upon us, and murder our woman and children, and burn our beautiful city!”[52] the Nauvoo city council passed a resolution ordering that both the paper and the printing establishment “be removed without delay.”[53] As mayor, Joseph Smith ordered that city marshal John P. Greene carry out the resolution by destroying “the printing press from whence issues the Nauvoo Expositor, and pitch the type of said printing establishment in the street, and burn all the Expositor and libelous handbills found in said establishments.”[54]

Soon after the press and paper were destroyed, criminal charges were filed against the Nauvoo city council, including John Taylor, and others claiming that such destruction constituted a “riot” pursuant to Illinois law. Three hearings were held the ensuing week over the riot allegations. On June 12, Carthage Justice of the Peace Robert Smith (one of the captains of the anti-Mormon Carthage Greys), based on the complaint filed by Francis M. Higbee, issued a writ for the arrest of Joseph Smith, as mayor, the Nauvoo City Council, and others involved in the destruction of the paper and press. These men were arrested and immediately petitioned for a writ of habeas corpus under the municipal laws of Nauvoo for the warrant to be reviewed in Nauvoo. The Nauvoo Municipal Court, in special session, granted Joseph Smith’s petition and after hearing testimony discharged Smith, finding that the destruction did not constitute a riot.

The following day the rest of the defendant’s petitions were heard and they too were discharged.[55] Unfortunately, these hearings only served to further inflame the antagonists, and based upon advice from various parties, including Judge Thomas,[56] the previously enumerated defendants allowed the issue of the arrest over riot to be heard again before Judge Daniel H. Wells, then a non-Mormon. After a full day of testimony on June 17, 1844, Judge Wells found in favor of the defendants, ruling that there was not probable cause to find that destruction of the press and papers constituted a riot.[57] The defendants were all discharged a second time.

Escalating Conflict

During these evidentiary hearings, anti-Mormon editors and antagonists waged an escalating campaign against Joseph Smith, the Church, and the civic leaders of Nauvoo. As a result of the rhetoric of defamatory articles calling for an armed conflict and extermination,[58] Joseph’s tethered hold on the situation seemed to be slipping. Taylor recorded the immediate reaction by the non-Mormon community as he tried to publish his newspapers to explain the city’s position: “But such was the hostile feeling, so well arranged their plans, and so desperate and lawless their measures, that it was with the greatest difficulty that we could get our papers circulated; they were destroyed by postmasters and others, and scarcely ever arrived at the place of their destination, so that a great many of the people, who would have been otherwise peaceable, were excited by their misrepresentations, and instigated to join their hostile or predatory bands.”[59]

In an effort to protect Nauvoo from threatened armed attack, Smith put the city under martial law on June 18, thereby restricting people from entering and exiting the city. By June 20, Governor Thomas Ford arrived in Carthage to seek a resolution. He wrote to Mayor Smith and the city council requesting an explanation of the circumstances. Joseph Smith appointed John Taylor and John M. Bernhisel to meet with Governor Ford in Carthage, carrying various documents and affidavits explaining the recent events. Taylor described the events on their arrival: “On our arrival we found the governor in bed, but not so with the other inhabitants. The town was filled with a perfect set of rabble and rowdies, who, under the influence of bacchus, seemed to be holding a grand saturnalia, whooping, yelling and vociferating, as if bedlam had broken loose. . . . That night I lay awake with my pistols under my pillow, waiting for any emergency.”[60]

Their meeting the next day with the governor was marred by insults and impatience of both the governor and the men that accompanied him. Taylor recounted:

He was surrounded by some of the vilest and most unprincipled men in creation; some of them had an appearance of respectability, and many of them lacked even that. Wilson, and I believe, William Law were there, Foster, Frank and Chauncey Higbee, Mr. Mar, a lawyer from Nauvoo, a mobocratic merchant from Warsaw, the aforesaid Jackson, a number of his associates, among whom was the governor’s secretary; in all, some fifteen or twenty persons, most of whom were recreant to virtue, honor, integrity, and everything that is considered honorable among men.

I can well remember the feelings of disgust that I had in seeing the governor surrounded by such an infamous group, and on being introduced to men of so questionable a character; and had I been on private business, I should have turned to depart, and told the governor that if he thought proper to associate with such questionable characters, I should beg leave to be excused; but coming as we did on public business, we could not, of course, consult our private feelings.[61]

The meeting ended with Governor Ford sending back written instructions requiring that Joseph Smith and the others accused in the two previous cases for riot come to Carthage and have the issue heard again there. Ford pacified Taylor’s concern about Smith’s safety, “strenuously advised us not to bring any arms, and pledged his faith as governor, and the faith of the state, that we should be protected, and that he would guarantee our perfect safety.”[62] Taylor remembered that had Joseph Smith wanted, there were in Nauvoo “about five thousand men under arms, one thousand of whom would have been amply sufficient for our protection.”[63]

Anticipated Exodus from Nauvoo

The next couple of days in Nauvoo further evidenced Taylor’s loyalty and friendship to the Prophet. When Joseph and Hyrum Smith left Nauvoo and crossed the Mississippi River in anticipation of going west,[64] Taylor also made preparations to leave Nauvoo. He packed the stereotype plates for the Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants at his printing office[65] and crossed the Mississippi River to meet up with the Smiths, then anticipating heading north to Canada. When the Smiths decided to return to Nauvoo and meet Ford in Carthage, Taylor followed.

Joseph and Hyrum Smith, along with the city council—comprised of the aldermen and councilors—Marshal Greene, and others who assisted in the destruction of the newspapers and press, arrived in Carthage on June 25. Taylor explained:

[They] appeared before Justice Smith, the aforesaid captain and mobocrat, to again answer the charge of destroying the press; but as there was so much excitement, and as the man was an unprincipled villain before whom we were to have our hearing, we thought it most prudent to give bail, and consequently became security for each other in $500 bonds each, to appear before the county court at its next session. We had engaged as counsel a lawyer by the name of Wood, of Burlington, Iowa; and Reed, I think, of Madison, Iowa. After some little discussion the bonds were signed, and we were all dismissed.[66]

For virtually everyone who had traveled from Nauvoo with Joseph and Hyrum Smith and surrendered to the dictates of Governor Ford, their experience in Carthage was over.[67] Yet Taylor’s experience in Carthage was only beginning. In addition to the riot charges previously filed by Higbee, upon arrival to Carthage Joseph and Hyrum Smith were also charged with treason apparently arising from the ordering of martial law in Nauvoo the previous week. While a hearing was held that day over the riot charge, resulting in the defendants’ release on bail, the treason charges were not heard. Instead, in contravention of all procedural protections, justice of the peace Robert Smith issued a mittimus ordering Joseph and Hyrum Smith confined to Carthage Jail.

Taylor, freed on bail, took the role as one of Joseph and Hyrum Smith’s principal advocates. He immediately went to Governor Ford to seek redress. Incensed over the injustices imposed upon the Smiths, Taylor recalled:

As I was informed of this illegal proceeding, I went immediately to the governor and informed him of it. Whether he was apprised of it before or not, I do not know; but my opinion is that he was.

I represented to him the characters of the parties who had made oath, the outrageous nature of the charge, the indignity offered to men in the position which they occupied, and declared to him that he knew very well it was a vexatious proceeding, and that the accused were not guilty of any such crime. The governor replied, he was very sorry that the thing had occurred; that he did not believe the charges, but that he thought the best thing to be done was to let the law take its course. I then reminded him that we had come out there at his instance, not to satisfy the law, which we had done before, but the prejudices of the people, in relation to the affair of the press; that at his instance we had given bonds, which we could not by law be required to do to satisfy the people, and that it was asking too much to require gentlemen in their position in life to suffer the degradation of being immured in a jail at the instance of such worthless scoundrels as those who had made this affidavit.[68]

Taylor accompanied Joseph and Hyrum Smith to Carthage Jail. He stayed with them[69] two more days,[70] when they were killed by a mob on June 27, 1844, while under the promised protection of the state of Illinois.[71]

The murder of Joseph and Hyrum eclipsed any other event that day. Joseph Smith wrote his final letter to his wife Emma that morning: “Dear Emma, I am very much resigned to my lot, knowing I am justified, and have done the best that could be done. Give my love to the children and all my friends, Mr. Brewer, and all who inquire after me; and as for treason, I know that I have not committed any, and they cannot prove anything of the kind, so you need not have any fears that anything can happen to us on that account. May God bless you all.”[72]

“A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief”

Sometime between three and four in the afternoon, John Taylor sang “A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief.”[73] John Taylor’s memory of that song, possibly tainted by the events that followed, are in some conflict with the reverenced place it now holds. He opined that “the song is pathetic, and the tune quite plaintive, and was very much in accordance with our feelings at the time for our spirits were all depressed, dull and gloomy and surcharged with indefinite ominous forebodings.”[74] Taylor sang the song twice that day. The first time was of his own accord. Shortly before the mob stormed the ill-guarded jail, Hyrum requested he sing it again, to which John replied, “Brother Hyrum, I do not feel like singing.” Hyrum persisted, replying, “Oh! never mind, commence singing, and you will get the spirit of it.”[75] So John sang it a second time.

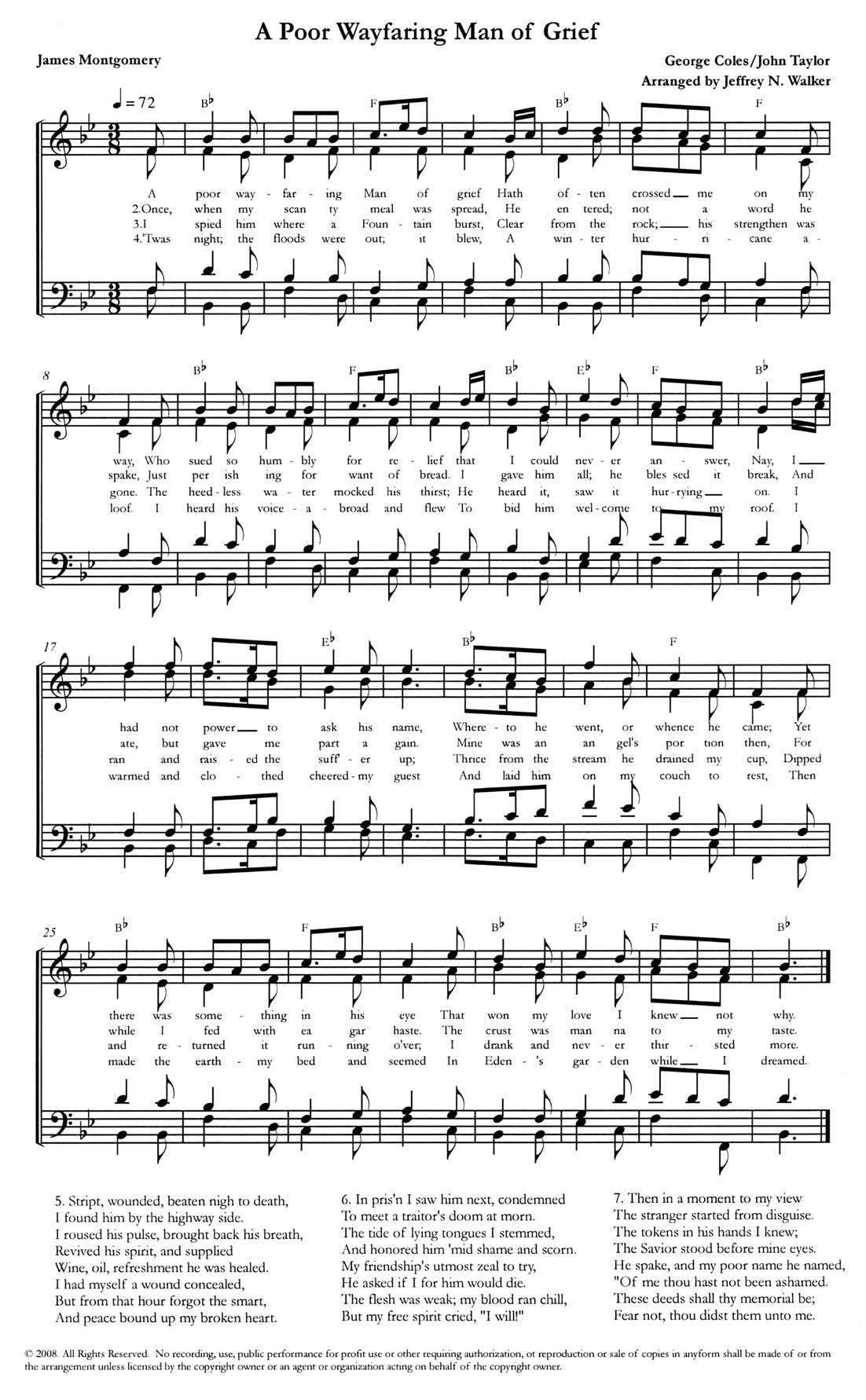

This hymn has been printed in Church hymnals since 1840. Under the direction of John Taylor, Brigham Young, and Parley P. Pratt, it was included it in an 1840 hymnal published in Manchester, England.[76] This hymnal would be known as the “Manchester Hymnal.” The words for the hymn are from a poem written in December 1826 by James Montgomery, a well-known Christian and English poet.[77] He entitled his poem “The Stranger and His Friend.”[78] While both a poet and hymnist, Montgomery never considered the poem as text for a hymn. He published it in several of his collections of poetry under the shortened title “The Stranger.”[79] By the 1840s his poetry was often reprinted in Christian publications in America, including newspapers in Nauvoo.[80]

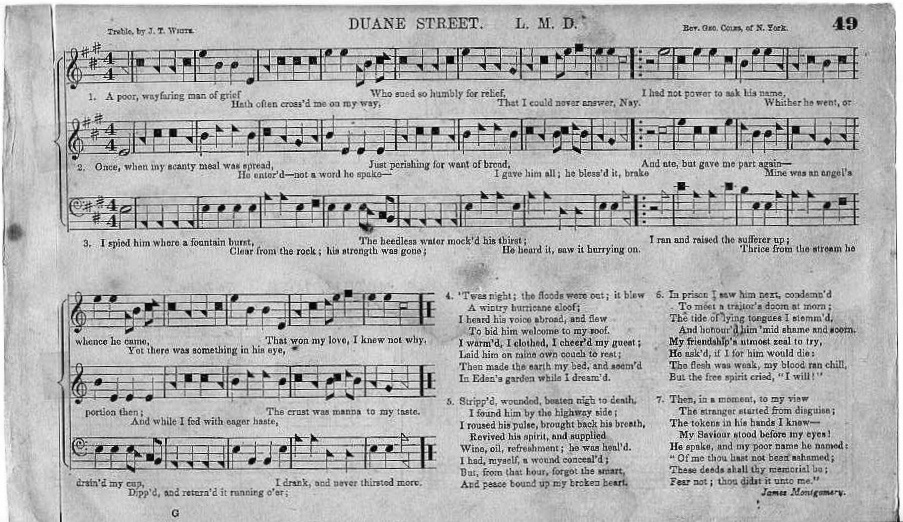

George Coles, a British minister and musician living in New York, put “The Stranger” to music in 1835.[81] Naming the tune after a New York City church at which he had preached, “Duane Street” became the most popular tune accompanying Montgomery’s poem. This tune was the basis for what John Taylor sung at Carthage Jail. Taylor noted that this song had “been lately introduced into Nauvoo.”[82] However, he was surely aware of it before that time as he included it in the Manchester hymnal that he assisted in publishing four years earlier. While the earliest known print version of “The Stranger” put with Cole’s tune “Duane Street” is B. F. White’s Sacred Harp, published in 1844,[83] one can assume that Taylor already was familiar with the poem put to this music, as evidenced by his singing of it at Carthage Jail. White’s Sacred Harp was advertised in Taylor’s Nauvoo Neighbor.[84]

Benjamin F. White, Sacred Harp (Philadelphia: 1844).

Benjamin F. White, Sacred Harp (Philadelphia: 1844).

The tune “Duane Street” differs markedly from the version found in the LDS hymnals, although they are clearly related. The following is the earliest version of “Duane Street” with the words of “The Stranger” and is followed by the version that is currently found in the LDS hymnal:[85]

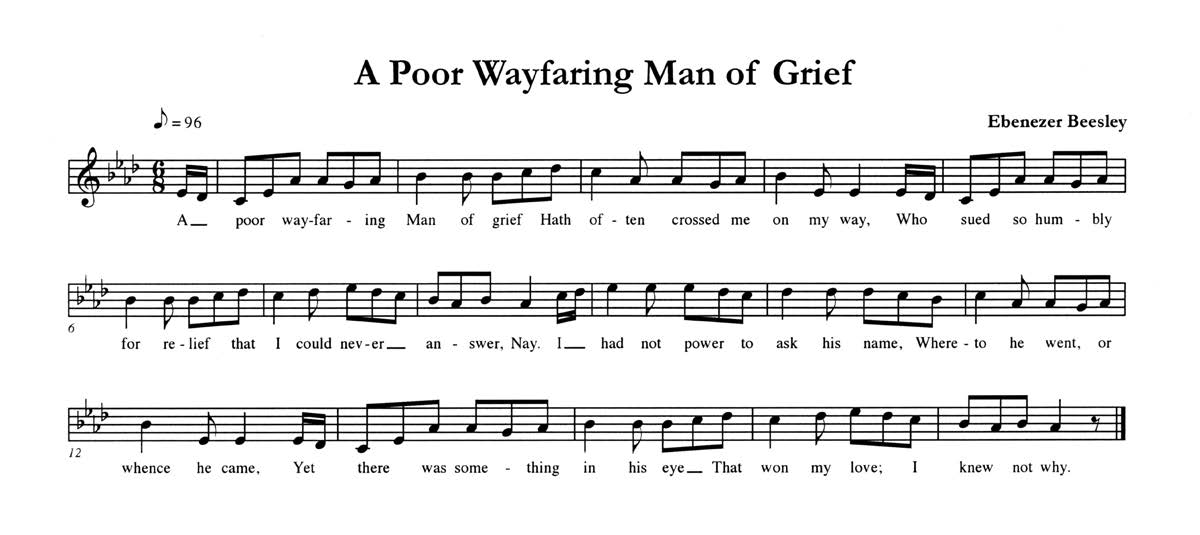

“A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief,” as arranged by Ebenezer Beesley and found for the first time in Latter-day Saints’ Psalmody (1889).

“A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief,” as arranged by Ebenezer Beesley and found for the first time in Latter-day Saints’ Psalmody (1889).

Michael Hicks provides a thorough discussion about the differences between these two versions in his 1983 BYU Studies article, ‘“Strains Which Will Not Soon Be Allowed to Die . . .’: ‘The Stranger’ and Carthage Jail.”[86] Yet this discussion does not address why or when the hymn’s tune was changed. For Latter-day Saints the starting point has to be Taylor. How did he sing this “plaintive” tune? Frederick Beesley, the son of Ebenezer Beesley (an early Utah pioneer musician and composer and one of five men called by President Taylor in 1886 to produce the first hymnal with music) records the following about Taylor singing this hymn at Carthage Jail: “Father [Ebenezer Beesley] was once called upon by President John Taylor to write down the melody of ‘A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief,’ just as Brother Taylor had sung it in Carthage Jail on the day of the Prophet Joseph Smith’s martyrdom. This father did and then arranged the four parts, as we have the piece at present in our Latter-Day Saint Hymns.”[87]

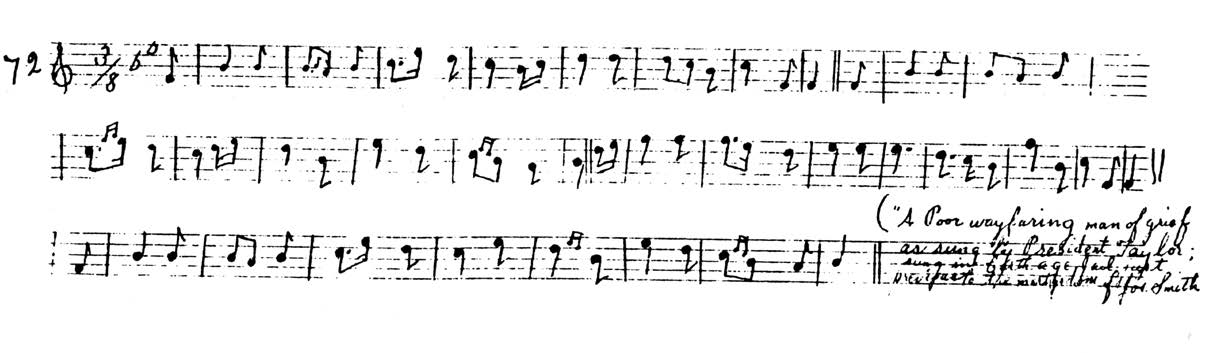

This notation penned at Taylor’s request “appears on page 72, the last page of Ebenezer Beesley’s copy of the bass part of the manuscript compilation of hymns for the Tabernacle Choir.”[88] The following is a copy of his notation:

Manuscript notation of “A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief,” as sung by John Taylor and recorded in 1886 by Ebenezer Beesley.[89]

Manuscript notation of “A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief,” as sung by John Taylor and recorded in 1886 by Ebenezer Beesley.[89]

The tune sung by Taylor is obviously derived but different from the traditional “Duane Street.” This includes changing the key signature from A major to B-flat major. Beesley moved the key signature further down a half step to A-flat major. The time signature was changed from 4/

It appears that Beesley’s changes were made as a result of Taylor’s version. Perhaps Beesley not only considered Taylor’s version but also knew Taylor viewed the song as “pathetic, and . . . quite plaintive.”[91] Beesley’s version is certainly a more elegant, formal piece—a hymn appropriate for a memorial to the tragic events of the Martyrdom.

A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief” arranged by Jeffrey N. Walker and based on the version sung by John Taylor.

A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief” arranged by Jeffrey N. Walker and based on the version sung by John Taylor.

Yet the tune sung by Taylor in June 1844 is compelling. Being different from what we are accustomed to, it can transport us back to 1844. The tune gets into your head, and you find yourself humming it. It is not hard imagine John Taylor humming it too, and then softly singing it in the upstairs bedroom at Carthage. The tune helps us understand more clearly why Hyrum asked that it be sung again. We need to know the tune, the one John sang and Hyrum liked. Such intrigue and interest in the tune resulted in the arrangement as a traditional four-part hymn.

Taylor was seriously wounded during the rampage at Carthage Jail, being shot four times.[92] One ball was never extracted.[93] He was dragged by Williard Richards to a cell within the jail and covered with an old, filthy mattress.[94] His bravery and leadership was evidenced as, despite the seriousness of his injuries and the unthinkable associated pain, he sought to comfort the Saints and prevent retribution.[95]

We may never know if John Taylor really liked “A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief” after the Martyrdom. To Latter-day Saint it is held in reverence as a memorial to the tragic events at Carthage Jail. Clearly President Taylor understood the historic importance of the song, as he had Beesley document his version. Yet Taylor later penned his own hymn in memory of the Martyrdom, entitled “O, Give Me Back My Prophet Dear.”[96] The words capture the loss Taylor felt for the remainder of his life as he was a unique witness to the events of the Martyrdom:

O, give me back my Prophet dear,

And Patriarch, O give them back,

The saints of Latter-days to cheer,

And lead them in the gospel track!

But, O, they’re gone from my embrace,

From earthly scenes their spirits fled,

Two of the best of Adam’s race,

Now lie entombed among the dead.

Ye men of wisdom, tell me why—

No guilt, no crime in them were found—

Their blood doth now so loudly cry,

From prison walls and Carthage ground?

Your tongues are mute, but pray attend,

The secret I will now relate,

Why those whom God to earth did lead,

Have met the suffering martyrs’ fate.

It is because they strove to gain,

Beyond the grave a heav’n of bliss,

Because they made the gospel plain,

And led the saints to righteousness;

It is because God called them forth,

And led them by his own right hand,

Christ’s coming to proclaim on earth,

And gather Israel to their land.

It is because the priests of Baal

Were desperate their craft to save,

And when they saw it doomed to fall,

They sent the prophets to their grave.

Like scenes the ancient prophets saw,

Like these the ancient prophets fell,

And, till the resurrection dawn,

Prophet and Patriarch farewell.[97]

Notes

[1] John Taylor, Witness to the Martyrdom: John Taylor’s Personal Account of the Last Days of the Prophet Joseph Smith, comp. and ed. Mark H. Taylor (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1999), 84.

[2] At the age of fourteen, Taylor apprenticed with a cooper in Liverpool prior to learning the trade of a turner (a carpenter specializing in using a lathe). After five years of apprenticing as a turner, John returned home at age twenty and opened a business with his father, who also was a carpenter (John Taylor, “History of John Taylor by Himself,” MS, Church History Library, 1-3).

[3] Taylor recounts that he was a member of the Church of England until age sixteen, when he joined the Methodist faith. He became a voluntary preacher or exhorter for the Methodists when he was seventeen. He notes about this period of his life, “I was strictly sincere in my religious faith and was very zealous to learn what I then considered the truth believing that ‘every good and perfect gift proceeded from the Lord’” (Taylor, “History of John Taylor,” 5).

[4] Taylor, “History of John Taylor,” 7.

[5] John Taylor and Leonora Cannon married on January 28, 1833. Leonora was twelve years older than John and the daughter of Captain George Cannon (grandfather of President George Q. Cannon) of Peel, Isle of Man. Leonora immigrated to Canada, where she was a “companion to the wife of Mr. Mason, the private secretary of Lord Aylmer, Governor General of Canada” (Brigham H. Roberts, The Life of John Taylor [Salt Lake City: George Q. Cannon & Sons, 1892], 12).

[6] Speaking about this period, Taylor remembers, “I often wondered why the Christian religion was so changed from its primitive simplicity, and became convinced, years before I dare acknowledge it, that we ought to have Apostles, Prophets, Pastors, Teachers and Evangelists—inspired men—as in former days” (Taylor, “History of John Taylor,” 7). Taylor recalled that for two years prior to meeting Parley P. Pratt, “a number of us met together for the purpose of searching the Scriptures; and we found that certain doctrines were taught by Jesus and the Apostles, which neither the Methodists, Baptists, Presbyterians, Episcopalians, nor any of the religious sects taught; and we concluded that if the Bible was true, the doctrines of modern Christendom were not true; or if they were true, the Bible was false. Our investigations were impartially made, and our search for truth was extended. We examined every religious principle that came under our notice, and probed the various systems as taught by the sects, to ascertain if there were any that were in accordance with the word of God. But we failed to find any. In addition to our researches and investigations, we prayed and fasted before God; and the substance of our prayers was, that if he had a people upon the earth anywhere, and ministers who were authorized to preach the Gospel, that he would send us one. This was the condition we were in” (in Journal of Discourses [London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1883], 23:30).

[7] During this time of investigating, Taylor addressed his friends and followers: “We are here, ostensibly in search of truth. Hitherto we have fully investigated other creeds and doctrines and proven them false. Why should we fear to investigate Mormonism? This gentleman, Mr. Pratt, has brought to us many doctrines that correspond with our own views. We have endured a great deal and made many sacrifices for our religious convictions. We have prayed to God to send us a messenger, if He has a true Church on earth. Mr. Pratt has come to us under circumstances that are peculiar; and there is one thing that commends him to our consideration; he has come amongst us without purse or scrip, as the ancient apostles traveled; and none of us are able to refute his doctrine by scripture or logic. I desire to investigate his doctrines and claims to authority, and shall be very glad if some of my friends will unite with me in this investigation. But if no one will unite with me, be assured I shall make the investigation alone. If I find his religion true, I shall accept it, no matter what the consequences may be; and if false, then I shall expose it” (Roberts, Life of John Taylor, 18–19).

[8] Taylor recounted, “I wrote down eight of the first sermons that he [Pratt] preached and compared them with the Scriptures. I also investigated the evidence concerning the Book of Mormon and read the Doctrine and Covenants. I made a regular business of it for three weeks and followed Br. Parley from place to place. At length being perfectly satisfied of the truth of Mormonism” (Taylor, “History of John Taylor,” 10).

[9] Parley P. Pratt baptized John and Leonora Taylor in Black Creek, on the outskirts of Toronto, on May 9, 1836 (Roberts, Life of John Taylor, 19).

[10] Taylor took three trips to Kirtland. It was on his first visit that he was called on to defend Joseph Smith against criticism from his mentor, Parley P. Pratt, replying to Pratt’s complaints: “I was surprised to hear him [Pratt] speak so, that before he left Canada he had borne a strong testimony to Joseph being a Prophet of God and to the truth of the work, these things he knew by revelation and the gift of the Holy Ghost, and that he gave me a strict charge that if he, or an angel from Heaven was to declare anything else I was not to believe them. Now Br. Parley, it is not man that I am following, but the Lord. The principles that you taught me led me to Him and I now have the same testimony that you then rejoiced in. If the work was true six months ago, it is true today; if Joseph Smith was then a Prophet, he is now a Prophet.” Taylor further defended Joseph Smith at a meeting in the Kirtland Temple during this first trip. Taylor concluded, “This was my first introduction to the Saints collectively and while I was pained on the one hand to witness the hard feelings and hard expressions of apostates on the other I was rejoiced to see the firmness faith, integrity and joy of the faithful and returned home rejoicing” (Taylor, “History of John Taylor,” 15–16).

[11] Taylor, “History of John Taylor,” 13–14.

[12] Taylor recorded about his calling to the Twelve: “I will state that I was living in Canada at the time, some three hundred miles distant from Kirtland. I was presiding over a number of churches in that region, in fact, over all of the churches in Upper Canada. I knew about this calling and appointment before it came, it having been revealed to me. But not knowing but that the devil had a finger in the matter, I did not say afnything about it to anybody. . . . A messenger came to me with a letter from the First Presidency, informing me of my appointment, and requesting me to repair forthwith to Kirtland, and from there to go to Far West. I went according to the command” (John Taylor, The Gospel Kingdom: Selections from the Writings and Discourses of John Taylor, ed. G. Homer Durham [Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1987], 190; see also Taylor, “History of John Taylor,” 18).

[13] Taylor made plans to move to Kirtland for nearly two years. He recounted he had “purchased a house and barn and five acres of ground within about one quarter of a mile from the Kirtland Temple” (Taylor, “History of John Taylor,” 20).

[14] Taylor was sustained as an Apostle during the October 1838 conference in Far West. Yet due to the vicissitudes that ensued, his ordination under the hands of Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball was delayed until December (The Conference Minutes and Record Book of Christ’s Church of Latter Day Saints [Far West Record], December 19, 1838, 176, MS, Church History Library).

[15] Susan Easton Black and Richard E. Bennett, eds., A City of Refuge: Quincy, Illinois (Salt Lake City: Millennial Press, 2000), 11–15, 132–33. John Taylor chaired the committee organized to facilitate the orderly implementation of Boggs’s extermination order, the removal of the Saints from Missouri (Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1932], 3:250–51).

[16] See Doctrine and Covenants 118:4–5. Taylor returned to Far West with Brigham Young, Orson Pratt, Wilford Woodruff, George A. Smith, John Page and Heber C. Kimball. Woodruff and Smith were ordained as Apostles at the temple site at Far West, thereby making a majority of the Quorum of the Twelve present to fulfill the revelation.

[17] Joseph and Hyrum Smith, along with Lyman Wight, Alex McRae, and Caleb Baldwin, were released en route to Boone County, Missouri, as a result of a change in venue following their grand jury indictments in Gallatin on April 16, 1839 (Jeffrey Walker, “A Change of Venue: Joseph’s Release from Liberty,” address at the Mormon History Association conference, Sacramento, 2008; in author’s possession). Joseph Smith agreed to the recommendation that the Saints settle in Commerce while in Liberty Jail in March 1839 by purchasing land offered by Isaac Galland (Dean C. Jessee, Personal Writings of Joseph Smith [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2002], 439). Smith and his fellow prisoners arrived in Quincy, Illinois, on April 22, 1839 (Rough Draft Notes of History of the Church [“RDN”] 1838–038 [December 16, 1838] Church History Library). At the end of April 1839, John Taylor accompanied Joseph Smith and others in selecting a settlement location for the Saints. This included Lee County (Montrose), Iowa, and Hancock County (Commerce), Illinois. RDN 1838-038 (December 16, 1838); Manuscript History of the Church, Addenda, 15, 19 (December 25, 1838), Church History Library.

[18] Ronald K. Esplin notes of this period, as captured in a series of fall 1839 correspondence between John and Leonora Taylor, “These letters are also important as illustrations of the dedication and faith required for the apostles to answer the call to England at that difficult time, with their families suffering from poverty and disease” (“Sickness and Faith, Nauvoo Letters,” BYU Studies 15, no. 4 [Summer 1975]: 425–34).

[19] This was Taylor’s first published work and was entitled “A Short Account of the Murders, Robberies, Burnings, Thefts, and Other Outrages Committed by the Mob and Militia of the State of Missouri, upon the Latter Day Saints” (Springfield, IL: n.p., 1839). He noted pertaining to the publication of this pamphlet, “Some distance from Nauvoo, we met with Brother [George] Miller, whom I had baptized some time previously, who offered me a horse if I would accept it. . . . Another brother by the name of [John] Vance gave me a saddle and bridle. I then rode my horse to Springfield, Illinois, where I got a brother to sell it, and with the proceeds I published a short detail of our Missouri persecutions, in pamphlet form” (Samuel W. and Raymond W. Taylor, The John Taylor Papers: Records of the Last Utah Pioneer, vol. 1 (Redwood City, CA: Taylor Trust 1954), 40).

[20] James B. Allen, Ronald K. Esplin, and David J. Whittaker, Men with a Mission, 1837–1841: The Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in the British Isles (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 173–80.

[21] Manuscript History of Brigham Young, Church History Library, 61.

[22] Times and Seasons, August 16, 1841, 521–22.

[23] Taylor, John Taylor Papers, 56–57.

[24] Taylor’s first plural wife was Leonora’s cousin, Elizabeth Kaighin. Taylor later explained, “Where did this commandment come from in relation to polygamy? It also came from God. It was a revelation given unto Joseph Smith from God, and was made binding upon His servants. When this system was first introduced among this people, it was one of the greatest crosses that ever was taken up by any set of men since the world stood. Joseph Smith told others; he told me, and I can bear witness of it, ‘that if this principle was not introduced, this Church and kingdom could not proceed.’ When this commandment was given, it was so far religious, and so far binding upon the Elders of this Church, that it was told them if they were not prepared to enter into it, and to stem the torrent of opposition that would come in consequence of it, the keys of the kingdom would be taken from them” (Journal of Discourses, 11:221).

[25] Joseph Smith led a Latter-day Saint delegation comprising of Sidney Rigdon, Elias Higbee, Orrin Rockwell, and Robert Foster to Washington DC in November 1839. This trip included meeting with President Van Buren, who made the famous remark: “Gentlemen, your cause is just, but I can do nothing for you” (B. H. Roberts, The Rise and Fall of Nauvoo (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 2002), 54).

[26] Matthew J. Haslam, John Taylor: Messenger of Salvation (Amercan Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2002), 74.

[27] Roberts, Life of John Taylor, 75.

[28] The Times and Seasons, a bimonthly publication, was initially owned and operated by Don Carlos Smith, Joseph Smith’s brother, and printed using a press that was buried in Far West, Missouri, during the 1838 conflict. Don Carlos died on August 7, 1841, of malaria at age twenty-five. Thereafter, Joseph Smith was the initial chief editor with Taylor as his assistant. By the following November, Taylor assumed Joseph’s position as editor, although it appears almost from the outset that Taylor functioned as the chief editor.

[29] The Wasp was a weekly newspaper published by William Smith, a brother of Joseph Smith and a member of the Quorum of the Twelve. As the name implied, William was not afraid to use the paper to sting those in conflict with his views. When William was elected to the Illinois state legislature in 1842, the editorial control of the paper was turned over to John Taylor. Taylor softened the tone of the paper and focused more on “the general news of the day.” He changed the name of the paper from the Wasp to the Nauvoo Neighbor in March 1843.

[30] In early February 1842, Joseph Smith purchased the printing operations from Ebenezer Robinson, Don Carlos’ business partner. Smith transferred this property in January 1844 to John Taylor. In an agreement, Taylor assumed the liabilities and responsibilities for the guardianship of the estate of Edward Lawrence for which Joseph Smith was previously responsible in “consideration of which said Joseph Smith agrees to make to the said John Taylor a good and sufficient Warranty Deed for a part of Lot No 4 in Block 150 in the City of Nauvoo together with the Printing Office and all the fixtures furniture, printing materials” (agreement, January 23, 1844, 1 p., MS, in the hand of William Clayton, Trustee in Trust, Miscellaneous Financial Papers, Church History Library). We find further confirmation of this sale in Smith, History of the Church, 6:185: “W. W. Phelps, Newel K. Whitney and Willard Richards valued the printing office and lot at $1,500; printing apparatus, $950; bindery, $112; foundry, $270; total, $2,832. I having sold the concern to John Taylor, who in consideration was to assume the responsibility of the Lawrence estate.” See also Gordon A. Madsen, “Joseph Smith as Guardian—The Lawrence Estate (unpublished paper in possession of author), 18–20, 23, 26. It should be noted that this printing establishments was located at Water and Basin Streets in Nauvoo. In May 1845, Taylor moved the operations to Kimball and Main Street in Nauvoo. This location is where the printing office has been restored. Dean C. Jessee, John Taylor Nauvoo Journal (Provo, UT: Grandin Book Co., 1996), 13n18.

[31] Edwin Brown Firmage and Richard Collin Mangrum, Zions in the Courts: A Legal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 1830–1900 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 95–101; Monte McLaws, “The Attempted Assassination of Missouri Ex-Governor Lilburn W. Boggs,” Missouri Historical Review, October 1965, 50–62.

[32] For a summary of the initial efforts by Joseph Smith in using a writ of habeas corpus to quash the arrest warrant arising from the extradition request, see “Persecution,” Times and Seasons, August 15, 1842, 886–89. For a discussion on the propriety of using a writ of habeas corpus under Nauvoo ordinance, see Dallin H. Oaks, “The Suppression of the Nauvoo Expositor,” Utah Law Review 9 (1965), 862, 883.

[33] Sidney Rigdon contacted Justin Butterfield, the U.S. attorney for the District of Illinois, seeking his advice pertaining to the situation. Butterfield believed that since Joseph Smith had never “fled” from Missouri after the assassination attempt he could not be deemed a “fugitive” as alleged in the extradition request (Justin Butterfield to Sidney Rigdon, October 20, 1842, Sidney Rigdon Collection, Church History Library). Joseph Smith and other Church leaders met with Governor Ford in Springfield. Ford, after polling the Illinois Supreme Court justices (Ford was a justice prior to becoming governor) informed Smith that the court was ready to rule in his favor (Governor Thomas Ford to Joseph Smith, December 17, 1842, 3 pp., MS, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library). Butterfield confirmed Ford’s legal opinion (Justin Butterfield to Joseph Smith, December 17, 1842, 2 pp., ms, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library). Judge James Adams, a Latter-day Saint state judge living in Springfield, further supported these opinions (James Adams to Joseph Smith, December 17, 1842, 2 pp., MS, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library).

[34] Alton Telegraph & Democratic Review, January 7, 1843.

[35] Joseph Smith, Journal, January 1, 1843, MS, Church History Library. Sunday services fell on New Year’s Day, January 1, 1843.

[36] Taylor spoke at the afternoon session, taking his text from Revelation 14:6–7: “And I saw another angel fly in the midst of heaven, having the everlasting gospel to preach unto them that dwell on the earth, and to every nation, and kindred, and tongue, and people, saying with a loud voice, Fear God, and give glory to him; for the hour of his judgment is come: and worship him that made heaven, and earth, and the sea, and the fountains of waters” (Joseph Smith, Journal, January 1, 1843, MS, Church History Library).

[37] Judge Pope found the underlying affidavit from Lilburn W. Boggs was legally insufficient, as it improperly contained legal conclusions rather than factual allegations. Consequently, the affidavit did not support the extradition request from Missouri governor Reynolds. His ruling first appeared on January 19, 1843, in the Sangamo Journal and subsequently was officially published as Ex parte Smith, 6 Law Rep. 57, 3 McLean 121 (D. Illinois, January 5, 1843).

[38] “Missouri vs. Joseph Smith,” Times and Seasons, July 1, 1843, 243.

[39] Nauvoo Neighbor, July 5, 1843.

[40] Manuscript History of the Church, D-1, 1592, MS, in handwriting of Robert L. Campbell, Church History Library.

[41] Times and Seasons, October 1, 1843, 344.

[42] Taylor assisted Smith in writing to each of the then presidential candidates—John C. Calhoun, Lewis Cass, Richard M. Johnson, Henry Clay, and Martin Van Buren—in November 1843, to determine their respective position over the Latter-day Saints, specifically their claims against Missouri for losses sustained when they were expelled from the state in 1839. Each letter poised the same question, “What will be your rule of action relative to us, as a people, should fortune favor your ascension to the chief Magistracy?” (Joseph Smith to John C. Calhoun, November 4, 1843, 2 pp., MS, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library). Only three candidates responded and none proffered any support for the Mormons (Arnold K. Garr, Setting the Record Straight: Joseph Smith: Presidential Candidate [Orem, UT: Millennial Press, 2007], 37–38).

[43] Times and Seasons, February 15, 1844, 441. Taylor also argued in this editorial of nomination: “Under existing circumstances we have no other alternative, and if we can accomplish our object well, if not we shall have the satisfaction of knowing that we have acted conscientiously and have used our best judgment; and if we have to throw away our votes, we had better do so upon a worthy, rather than upon an unworthy individual, who might make use of the weapon we put in his hand to destroy us with. Whatever may be the opinions of men in general, in regard to Mr. Smith, we know that he need only to be known, to be admired; and that it is the principles of honor, integrity, patriotism, and philanthropy, that has elevated him in the minds of his friends, and the same principles if seen and known would beget the esteem and confidence of all the patriotic and virtuous throughout the union. Whatever therefore be the opinions of other men our course is marked out, and our motto from henceforth will be GENERAL JOSEPH SMITH.”

[44] Quoted in Smith, History of the Church, 6:443.

[45] Joseph Smith, Journal, April 19, 1843, Church History Library.

[46] Sidney Rigdon to Governor Thomas Ford, June 14, 1844, MS, Sidney Rigdon Papers, Church History Library. B. H. Roberts explained, “The publication of such a paper aroused great indignation within Nauvoo; and such was the bitterness engendered in the public mind outside of Nauvoo, both in Hancock county and in the surrounding counties, that to allow its continued publication meant, undoubtedly, the rising of mob forces and open war upon the saints with the destruction of Nauvoo as the inevitable result” (A Comprehensive History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints [Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1965], 2:228).

[47] Taylor, Witness to the Martyrdom, 30.

[48] Taylor, Witness to the Martyrdom, 31.

[49] Council member and attorney George P. Stiles opined that “a nuisance was anything that disturbs the peace of a community.” He reportedly read from Blackstone, concluding, “The whole community has to rest under the stigma of these falsehoods (referring to the Expositor); and if we can prevent the issuing of any more slanderous communications, he would go in for it. It is right for this community to show a proper resentment; and he would go in for suppressing all further publications of the kind” (Nauvoo Neighbor Extra, June 17, 1844). Stiles’s reading from Blackstone “vol. 2, page 4,” was most likely the following:

A fourth species of remedy by the mere act of the party injured, is the abatement, or removal of nuisances. . . . whatsoever unlawfully annoys or doth damage to another is a nuisance; and such nuisance may be abated, that is, taken away or removed, by the aggrieved thereby, so as he commits no riot in the doing of it. . . . And the reason why the law allows this private and summary method of doing one’s self justice, is because injuries of this kind [example omitted], which obstruct or annoy such things as are of daily convenience and use, require an immediate remedy; and cannot wait for the slow progress of the ordinary forms of justice.

As to private nuisances, they also may be abated. . . . So it seems that a libelous print or paper, affecting a private individual, may be destroyed, or, which is the safer course, taken and delivered to a magistrate. (5 Coke, 125, b. 2 Camp 155; 2 Blackstone, Commentaries 4–6, and n.6 [Am. ed. 1832])

Joseph Smith would confirm this understanding in his letter to Governor Ford dated June 22, 1844: “The press was declared a nuisance under the authority of the charter as written in 7th section of Addenda, the same as in the Springfield charter, so that if the act declaring the press a nuisance was unconstitutional, we cannot see how it is that the charter itself is not unconstitutional: and if we have erred in judgment, it is an official act, and belongs to the Supreme Court to correct it, and assess damages versus the city to restore property abated as a nuisance. If we have erred in this thing, we have done it in good company, for Blackstone on ‘Wrongs,’ asserts the doctrine that scurrilous prints may be abated as nuisances” (Smith, History of the Church, 6:538).

[50] Taylor, Witness to the Martyrdom, 32.

[51] Nauvoo Neighbor Extra, June 17, 1844.

[52] Nauvoo Neighbor Extra, June 17, 1844.

[53] The resolution stated: “Resolved, by the City Council of the city of Nauvoo, that the printing-office from whence issues the Nauvoo Expositor is a public nuisance and also all of said Nauvoo Expositors which may be or exist in said establishment; and the Mayor is instructed to cause said printing establishment and papers to be removed without delay, in such manner as he shall direct” (Nauvoo Neighbor Extra, June 17, 1844).

[54] Nauvoo Neighbor Extra, June 17, 1844.

[55] Francis Higbee filed the subject complaint on June 12, 1844 in Carthage for riot against the following city officials: Joseph Smith, Samuel Bennett, John Taylor, William W. Phelps, Hyrum Smith, John P. Greene, Stephen Perry, Dimick B. Huntington, Jonathan Dunham, Stephen Markham, William Edwards, Jonathan Holmes, Jesse P. Harmon, John Lytle, Joseph W. Coolidge, Harvey D. Redfield, Porter Rockwell, and Levi Richards (June 12, 1844, ms, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library). The Nauvoo Municipal Court, in special session, heard the matter later that day. Eleven witnesses testified. The court ruled, apparently from the bench: “Joseph Smith had acted under proper authority in destroying the establishment of the Nauvoo Expositor on the 10th inst. that his orders were executed in an orderly & judices [judicious] manner, without noise or tumult, that this was a malices [malicious] prosecution on the part of FM Higbee and that said Higbee pay the costs of suit, and that Joseph Smith be honorebly discharged from the accusations and of the writ & go hence without day.” The next day the same court, with Joseph Smith as chief judge, discharged the rest of the defendants (Nauvoo Municipal Court Record, 110, MS, Church History Library).

[56] Judge Jesse B. Thomas, who was a circuit court judge for Hancock County, came to Nauvoo on Sunday, June 16, 1844, to meet with Joseph Smith and discuss the situation. He advised Smith “to go before some justice of the peace of the county, and have an examination of the charges specified in the writ from Justice Morrison of Carthage; and if acquitted or bound over, it would allay all excitement, answer the law and cut off all legal pretext for a mob, and he would be bound to order them to keep the peace” (June 16, 1844, MS, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library).

[57] The case involved the same defendants as the first, as well as the same claim of riot (June 17, 1844, ms, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library).

[58] Thomas C. Sharp, editor of the Warsaw Signal, wrote: “We hold ourselves at all times in readiness to co-operate with our fellow citizens . . . to exterminate, utterly exterminate, the wicked and abominable leaders” (Warsaw Signal, June 19, 1844).

[59] Taylor, Witness to the Martyrdom, 29.

[60] Taylor, Witness to the Martyrdom, 45, 47.

[61] This meeting took place on June 21, 1844 at the Hamilton hotel in Carthage, where Governor Ford was staying (Taylor, Witness to the Martyrdom, 48–49). Hamilton’s hotel, often referred to as the Hamilton House, was located on the northwest corner of Main and Washington street. In the 1840s the hotel was known as the Hamilton Tavern (Charles J. Scofield, History of Hancock County, Illinois [Chicago: Munsell Publishing, 1921], 717).

[62] Taylor, Witness to the Martyrdom, 51.

[63] Taylor, Witness to the Martyrdom, 51.

[64] Taylor explained, “It was Brother Joseph’s opinion that, should we leave for a time, public excitement, which was so intense, would be allayed; that it would throw on the governor the responsibility for keeping the peace; that in the event of an outrage, the onus would rest upon the governor, who was amply prepared with troops, and could command all the forces of the state to preserve order; and that the act of his own men would be an overwhelming proof of their seditious designs, not only to the governor, but to the world. He moreover thought that, in the east, where he intended to go, public opinion would be set right in relation to these matters, and its expression would partially influence the west, and that, after the first ebullition things would assume a shape that would justify his return” (Taylor, Witness to the Martyrdom, 54).

[65] Taylor explained, “I called together a number of persons in whom I had confidence, and had the type, stereotype plates, and most of the valuable things removed from the printing office, believing that should the governor and his force come to Nauvoo, the first thing they would do would be to burn the printing office” (Taylor, Witness to the Martyrdom, 53–54).

[66] Taylor, Witness to the Martyrdom, 61.

[67] Much has been written pertaining to the legal propriety of the destruction of the first issue of the Nauvoo Expositor and the printing press and type used to publish it. The most comprehensive discussion is by Dallin H. Oaks in “The Suppression of the Nauvoo Expositor,” Utah Law Review 9 (1965): 862. Oaks’ concludes that the destruction of the newspaper itself was supported by then-existing law; however, the destruction of the press and type probably was not (891). The outstanding issue was one of damages—whether against or in favor of the owners of the press. On the side of the owners, they could claim damages equal to the value of the press and its type. On the side of the city council, the damages against the owners could be, as suggested by councilman and attorney Warrington, in the form of a fine that could be assessed for each libelous statement. Warrington suggested a fine of three thousand dollars for each such statement. Further, under a then-existing city ordinance an additional five-hundred-dollar fine could be assessed for the nuisance itself (Smith, History of the Church, 6:445). Under this scenario, while the owners may have had a legitimate legal claim for damages against the city for the value of the press and type, it would have been only a fraction of the fines that the city council could have imposed. This possibility is confirmed as the Nauvoo city council settled with the owners of the Nauvoo Expositor in October 1844. The settlement was for $725—the amount that the owners had paid (and still owed) for the printing press (Nauvoo City Council, Minutes, July 1, 1844, September 14, 1844, and October 12, 1844, MS, 212, 213, 218, and 220, Church History Library). The decision to destroy the press by the city council was actually the most cost-effective consequence for the Laws, Higbees, and Fosters. I can find no record that the city council thereafter ever sought any fines against the Laws, Higbees, or Fosters for libel.

[68] Taylor, Witness to the Martyrdom, 64. Taylor summarized Ford’s conduct: “Governor Ford is certainly a man who performed mighty wonders. He not only compelled two innocent men, by virtue of his office as Governor of Illinois, to go before two different magistrates on the same charge, contrary to the Constitution and laws of the state; to surrender themselves into the custody of a mob magistrate (not the one who issued the writ); go to prison under a military guard on an illegal mittimus, granted contrary to law, without any examination; put in a criminal cell without having been examined for crime; brought them out of prison contrary to law; thrust them back again under the most solemn and sacred pledges of his personal faith, and the faith of the state, for their protection; guarded them with men whom he knew to be treacherous, and to have resolved on the death of the prisoners, until they were murdered in cold blood, and then professed to be ‘thunderstruck’!” (B. H. Roberts, ed., History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Part 2: Apostolic Interregnum, 2nd ed. rev. [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1932], 7:2).

[69] Taylor suggested to Joseph Smith a possible escape: “When conversing about deliverance, I said, ‘Brother Joseph, if you will permit it, and say the word, I will have you out of this prison in five hours, if the jail has to come down to do it.’ My idea was to go to Nauvoo and collect a force sufficient, as I considered the whole affair a legal farce, and a flagrant outrage upon our liberty and rights. Brother Joseph refused” (Taylor, John Taylor Papers, 82).

[70] Joseph Smith and his followers spent June 26 trying to understand the parameters of his and his brother’s incarceration. This included compiling a list of potential witnesses; meeting with their attorney Hugh Reid, who proposed moving for a change of venue; meeting with Governor Ford; and attending a brief court hearing. Taylor provides the most complete record of these events (Manuscript History of the Church, F-1, Addenda, pp. 3–8, MS, in handwriting of Leo Hawkins, Church History Library).

[71] Taylor personally expressed his concern over the protection of the Smiths to Governor Ford: “He [Governor Ford] replied that he would detail a guard, if we required it, and see us protected, but that he could not interfere with the judiciary. I expressed my dissatisfaction at the course taken, and told him that if we were to be subject to mob rule, and to be dragged, contrary to law, into prison at the instance of every infernal scoundrel whose oaths could be bought for a dram of whiskey, his protection availed very little, and we had miscalculated his promises” (Taylor, Witness to the Martyrdom, 65).

[72] Joseph Smith to Emma Smith, June 27, 1844, MS, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library.

[73] Diary, Willard Richards, June 27, 1844, MS, Church History Library.

[74] Taylor, Witness to the Martyrdom, 84.

[75] Taylor, Witness to the Martyrdom, 84. The Manuscript History of the Church notes that Joseph Smith asked Taylor to sing the song a second time (Manuscript History of the Church, F-1, 181, ms, in hand of Leo Hawskins, Church History Library). However, Taylor corrected this to Hyrum Smith in his own history.

[76] A Collection of Sacred Hymns for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Europe, informally known as the “Manchester Hymnal,” was first published in Manchester, England, in 1840. Like the first Latter-day Saint hymnal, it was text-only. Karen L. Davidson, “Hymns and Hymnody,” Encyclopedia of Mormonism (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 667. Its title was the same as the first hymnal compiled by Emma Smith in January 1836 with the addition of “in Europe.” Michael Hicks, Mormonism and Music: A History (Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 1989), 20. “The Manchester hymnal and its twenty-four succeeding editions and reprints were used officially for eighty-seven years. In 1912 the twenty-fifth and final edition was issued in Salt Lake City. It was used in the temples, in the Salt Lake Tabernacle, and in the Assembly Hall until 1927. Eventually it was replaced by other hymnals containing music as well as texts” (Michael F. Moody, “Latter-day Saint Hymnbooks, Then and Now,” Ensign, September 1985, 11).

[77] James Montgomery was born in Irvine, England, on November 4, 1771. Originally trained to be a minister, at age twenty-one, he began working at a weekly newspaper business. He eventually became both the proprietor and editor of the paper. He had several run-ins with the law pertaining to his newspaper work and twice serve time in York Castle, a prison. He wrote in explanation, “No man who did not live amidst the delirium of those evil days and that strife of evil tongues, could imagine the bitterness of animosity which infatuated the zealous partisans” (Robert Carruthers, The Poetical Works of James Montgomery With a Memoir [Boston: Houghton and Mifflin, 1881], xviii). In 1841 a collected edition of his works were published in four volumes and in 1853 he published a series of his hymns. “His history altogether affords a fine example of virtuous and successful perseverance, and of genius devoted to pure and noble ends,—not a feverish, tumultuous, and splendid career, like that of some greater poetical heirs of immortality, but a course ever brightening as it proceeded,—calm, useful, and happy” (Carruthers, Poetical Works of James Montgomery, xxi). Montgomery died in Sheffield, Scotland, in 1854 at the age of eighty-two.

[78] Montgomery described his process of writing the poem in a letter to a friend dated February 28, 1827: “Your sister mentions my little piece of the Stranger and his Friend. She will not feel less interest in it when I tell her that, except the first verse (composed in the dark in the coach on the morning that I set out from Sheffield to York), the sketch was written with pencil on a scrap of blank paper which I found in my pocket, while I was travelling alone in a chaise from Whitby to Scarborough, on that tempestuous Saturday, ten days before Christmas. These rough stanzas, so inspired by ‘vapours, clouds, and storms,’ on the wild and melancholy moors along that lofty coast, were afterwards painfully, yet pleasantly, elaborated, in my walks during the short stay which I made at Scarborough; and I shall never forget the accomplishment of the fourth verse, on the height of Oliver’s Mountain, on a gloomy, threatening afternoon, which naturally made me anticipate the horrors of such a night as is there described” (John Holland and James Evertt, Memoirs of the Life and Writings of James Montgomery [London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1855], 191–92).

[79] Michael Hicks, “‘Strains Which Will Not Soon Be Allowed to Die . . .’: ‘The Stranger’ and Carthage Jail,” BYU Studies 23, no. 4 (Fall 1983), 391.

[80] Hicks, ‘“Strains Which Will Not Soon Be Allowed to Die,”’ 391.

[81] Hicks notes that it was likely composed while Coles was living in Poughkeepsie, New York. Unfortunately the only possible account of Cole writing Duane Street is found is his autobiographical work, “Incidents in My Later Years,” of which no extant copy is known (Hicks, “‘Strains Which Will Not Soon Be Allowed to Die,’” 392n7).