Samuel D. Brunson, "'To Omit Paying Tithing': Brigham Young and the First Federal Income Tax," in Business and Religion: The Intersection of Faith and Finance, ed. Matthew G. Godfrey and Michael Hubbard MacKay (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 255–288.

Introduction

On 3 January 1871, Daniel H. Wells, a member of the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, received a telegram announcing that it would be “wisdom for the Latter Day Saints to omit paying tithing.”[1] That telegram marked the first steps toward reversing a three-decade-old practice, one that both provided a sizable portion of the church’s revenue and represented an important religious obligation of church members. What would induce the church to take such a drastic step? According to the telegram, tithing was no longer sustainable because some federal officers wanted to “rob us of our hard earnings which are donated to sustain the poor and other charitable purposes.”[2]

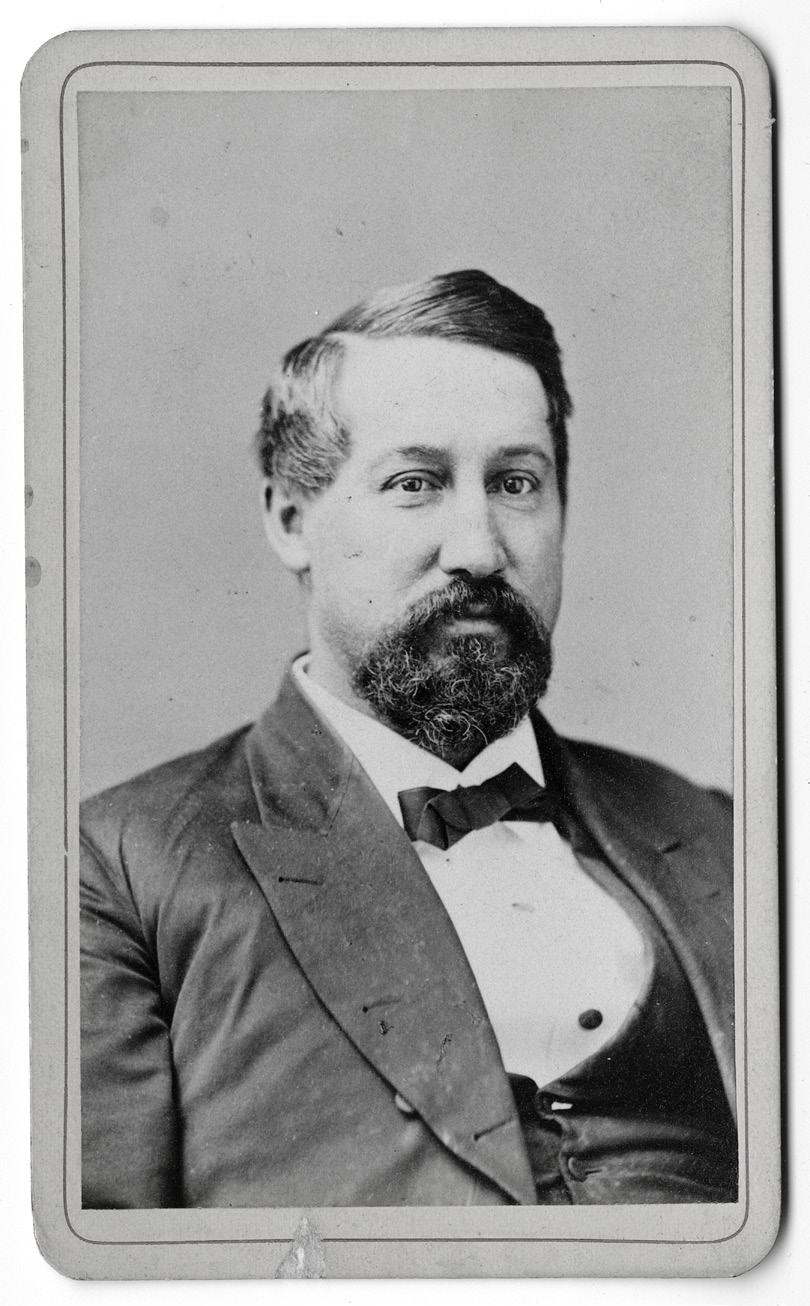

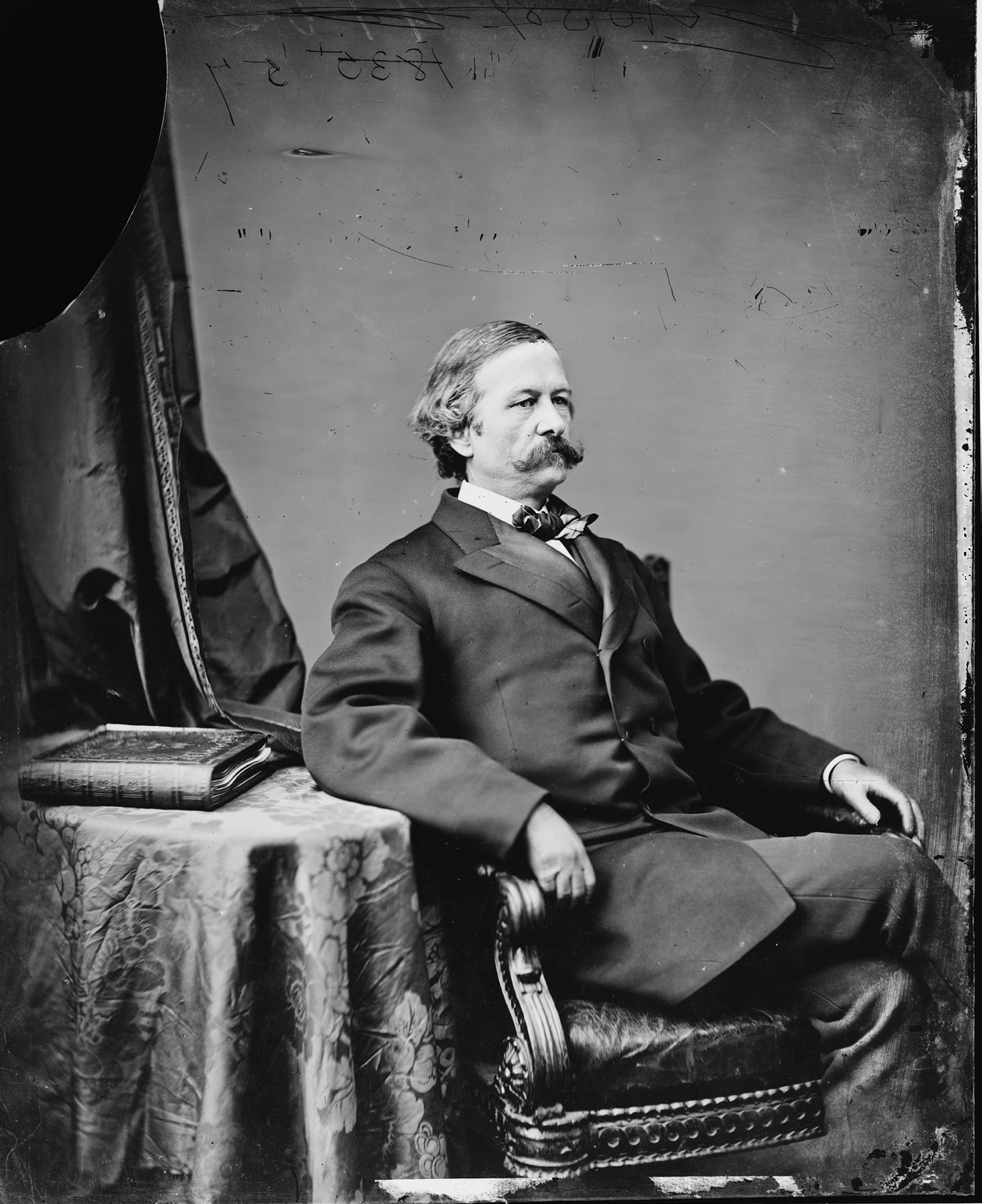

Brigham Young. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-cwpbh-01671.

Brigham Young. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-cwpbh-01671.

This robbery was neither hidden nor unlawful. Rather, it was enshrined in the relatively young federal income tax. And the first salvo in this robbery was an 18 August 1869 letter from John P. Taggart, the assessor of Internal Revenue for the Territory of Utah, to Francis M. Lyman, an assistant assessor. In the letter, Taggart told Lyman to “make an annual return” of the profits, gains, and incomes that had accrued to the church in 1868 and 1869.[3] That letter launched a battle between Taggart and church president Brigham Young that would encompass the next year and a half, as Taggart pursued Young for taxes on tithing members had paid to the church, while Young argued that tithing was not taxable income.

The Civil War Income Tax

Although it would expire by its own terms in 1872, in 1870, the federal income tax was still relatively young. The income tax can trace its roots to Great Britain, which in 1799 enacted the first modern income tax; that tax finally arrived on the shores of the United States in 1862, when the US federal government needed revenue to fight the Civil War.

Compared with the complexity and specificity of the modern federal income tax, the Civil War income tax was simplicity itself. The Revenue Act of 1862 taxed the annual “gains, profits, or income” of US residents.[4]

Prior to its enactment of the new income tax, the federal government had relied almost exclusively on tariffs to provide the revenue it needed.[5] Tariffs are taxes imposed on imported goods, and throughout the nineteenth century, the government collected the tariffs at customs houses.[6] These customs houses were located at various ports and were staffed with customs agents. The agents were responsible for inspecting ships and collecting tariffs on the goods being imported.[7]

The new federal income tax demanded a different collection mechanism than tariffs had. Administering the income tax “presumed an administration built around personal contact within limited geographic space.”[8] To allow the personal contact necessary to assess and collect the federal income tax, Congress created the Bureau of Internal Revenue, staffed by, among others, assessors and collectors.[9]

Taxing the Church

The year 1869—when Taggart assessed the church for income tax—proved an important year for the Territory of Utah and for the church members who lived there. The church and its members had initially moved west to escape persecution and to establish a relatively autonomous, isolated homeland.[10] But by 1869, the world they had left had definitely begun encroaching on their Zion in the desert. On 10 May 1869 the transcontinental railroad was completed at Promontory, near Ogden, Utah.[11] The railroad promised an end to the relative isolation of Utah and portended change, for good or for ill.[12]

The nation had largely turned its attention away from Utah during the Civil War, but that conflict ended in 1865.[13] Almost immediately, the country’s attention moved to Reconstruction, which attempted to bring the Confederate states back into the Union.[14] Initially, Congress enacted laws that required the transformation of Southern states’ governments; to be readmitted to the Union, states needed new constitutions, framed by individuals who took a loyalty oath, and the constitutions had to provide for African American suffrage.[15] While the federal government was intensely involved in the processes during the early years of Reconstruction, by the early 1870s, it had lifted voting restrictions on ex-Confederates, and its attention to and engagement with the Reconstruction process had begun to wane.[16]

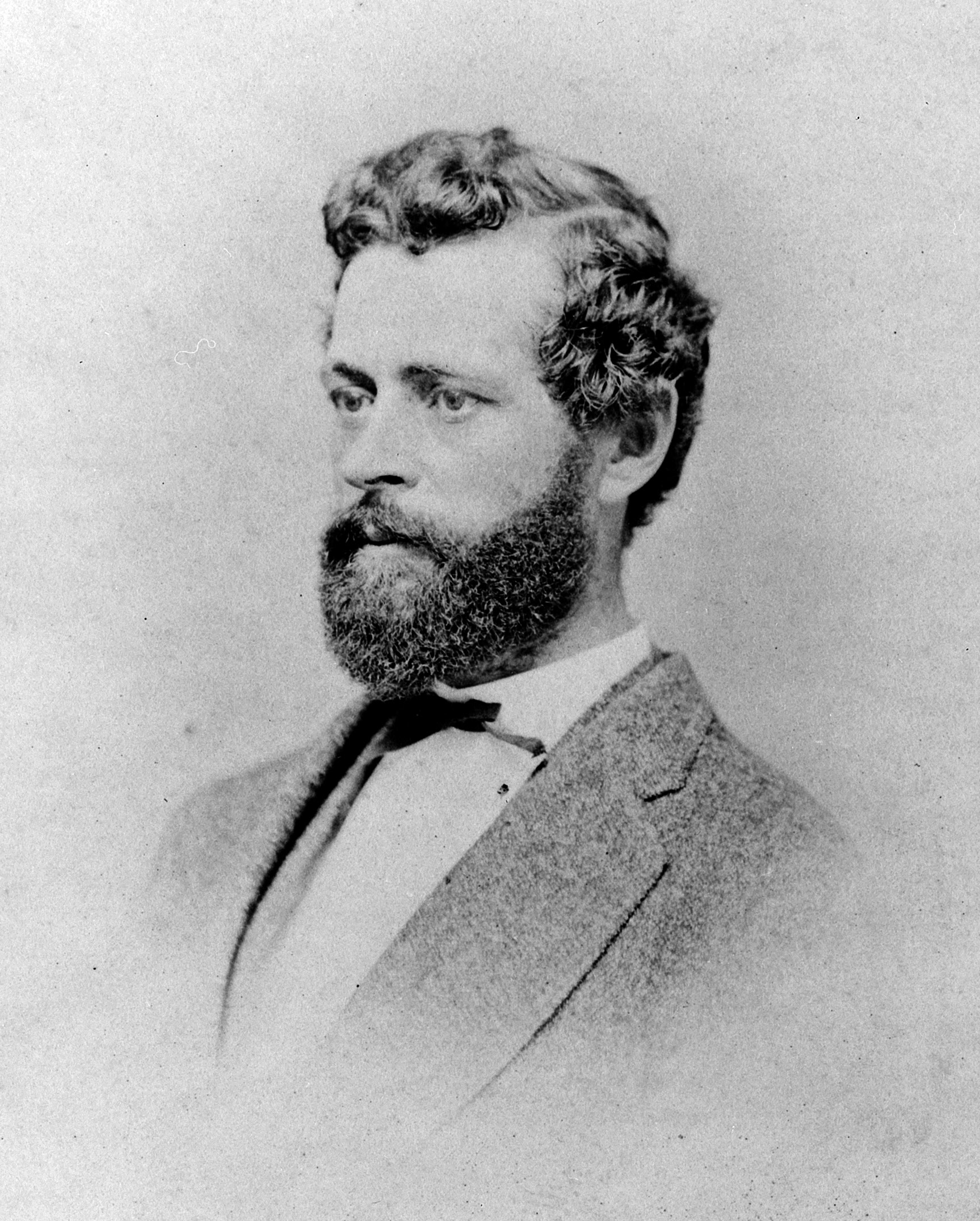

John P. Taggart. John P. Taggart papers USU_COLL MSS 520, box 1, folder 1. Special Collections and Archives, Utah State University, Merrill-Cazier Library, Logan, Utah.

John P. Taggart. John P. Taggart papers USU_COLL MSS 520, box 1, folder 1. Special Collections and Archives, Utah State University, Merrill-Cazier Library, Logan, Utah.

As the country’s focus on the South diminished, its collective eye turned again to Utah and its attempts to practice sovereignty and polygamy.[17] Speaking in Salt Lake City in October 1869, Vice President Schuyler Colfax told the assembled audience that the country was governed by law and that religious belief did not justify polygamy, which violated both American norms and federal law.[18]

In response to Utahns’ collective law breaking, the federal government began to work to reassert control over the largely church-controlled Utah. That goal was epitomized by the 1870 appointment of James B. McKean as the chief judge in Utah.[19] McKean asserted that he had a divinely commissioned duty to subjugate the church-run Utah government.[20] While the federal intervention in Utah may have been at least partly triggered by the Saints’ practice of polygamy, its immediate consequences were not the abolishment of “slavery’s ‘twin relic of barbarism.’”[21] While the practice of polygamy prevented Utah from achieving statehood, polygamists represented a significant majority of territorial officials and were able to insulate their fellow polygamists from civil and criminal consequences.[22] In fact, it was not until the Poland Act of 1874 that the federal government was able to successfully begin to prosecute polygamists.[23]

Even without a successful attack on polygamy, though, the federal attempt to reassert control over Utah’s government had consequences for the Latter-day Saints. Among other things, as part of this reassertion of federal control over Utah, John P. Taggart began his tenure as the assessor of Internal Revenue for the district of Utah.

Virtually from his first day on the job, Taggart proved unpopular among church members in Utah—and he returned their dislike in kind. While unpopularity may have been the rule for Internal Revenue assessors,[24] Utahns’ distrust of Taggart reflected something more than merely the generalized and near-universal dislike citizens have for tax collectors. His unpopularity reflected the 1869 distrust between church members and the federal government.

By February 1870, mere months after arriving in Utah, Taggart testified before the House of Representatives that “Mormons recognize and observe no law except such as they are compelled to observe. So far as my own department is concerned, I know they do not scruple at any means they can to contrive to evade the revenue law.”[25] He further testified that, when he arrived, “six of the assistant assessors . . . were Mormons.”[26] His investigations forced him to conclude that these assistant assessors “used partiality in behalf of Mormons,” and he soon fired them.[27]

Utahns took note of Taggart’s congressional testimony. In reporting what he had said, the Deseret News wrote that Taggart “despises the Mormons, religiously and every other way. And the Mormons, by his own showing, as cordially despise him.”[28] In a letter to Internal Revenue commissioner Columbus Delano, Brigham Young wrote, “Mr Taggart, I regret to say, had already made himself extremely unpopular among our citizens. They judged him as actuated not by the just and gentlemanly motives which characterized his predecessors, but by a bitter & deeply prejudiced animosity against the Latter-day Saints & their Institutions, in short, that he was an officious meddler in this & other matters with which he had no legitimate concern.”[29]

Tithing as Taxable Income

On 18 August 1869, Taggart wrote to assistant assessor Francis Lyman, instructing him to assess the income of the church for 1868 and 1869.[30] Lyman, likely one of the Latter-day Saint assistant assessors Taggart soon fired, wrote to Young, alerting him to Taggart’s instructions and interest in church income.[31]

About a month later, Taggart wrote directly to Young. Taggart informed Young that the commissioner of the Bureau of Internal Revenue had given him permission to go ahead with his assessment of the income of the “Society of Latter day Saints.” As Young had failed to comply with Taggart’s instructions, Taggart instructed him to appear at the assessor’s office with the church’s books and records, so that Taggart could accurately assess the church’s income.[32]

Four days later, Young responded to Taggart. He had, he said, made a return for the church’s income, and had delivered it to assistant assessor Richard V. Morris the month before. Young assured Taggart that the return “was correct and I trust will be satisfactory to you.”[33] He later reasserted that he had received the “form of Return” from Taggart on 19 August 1869, had “filled and returned [it] in the usual manner,” and had, to his knowledge and understanding, filled the form correctly.[34]

Young’s response proved unsatisfactory to Taggart, who informed Young that his office had no knowledge of any return being made by Young on behalf of the church. Because Young refused to make a return—or at least to make a return that satisfied Taggart—Taggart’s son Edwin[35] (who was also one of his assistant assessors) reported that he was “finally compelled to make the assessment myself.”[36] The tax law allowed assessors to fill in a return for taxpayers if they refused to do so. Because the Taggarts did not accept whatever Young filed as a return, Edwin did make a return on behalf of the church. According to Edwin, the church received between $2 million and $3 million in tithing annually.[37]

Ultimately, though, he assessed the church for just under $60,000 of income tax due. As part of their calculations, the Taggarts estimated that, for income tax purposes, the church had taxable income of $791,180.22. At a five-percent tax rate, it meant the church owed $39,559.01 in taxes. In addition, because Taggart believed Young had failed to file an honest return, he added a fifty-percent penalty, thus arriving at the $59,338.51 liability he assessed.[38] As trustee-in-trust of the church, Young was personally liable for the church’s taxes.[39]

The tax would have come as a surprise. With a few small exceptions, the Civil War income tax did not apply to corporations.[40] And even if it did, the Secretary of the Treasury had explicitly excluded charitable institutions, including churches, from its ambit.[41]

If the Secretary of the Treasury explicitly exempted charitable institutions from taxation, how did Taggart come to the conclusion that the Church of Jesus Christ should pay taxes on its tithing? He explained that “on seeing the decision of the Commissioner in regard to the property of a religious society in Ohio, deciding that the income of their church was taxable for revenue purposes, I became convinced that the Mormon church would come under the same rule.”[42]

The religious society Taggart referred to was a Shaker community in New Lebanon. Because the Shakers eschewed the private ownership of property, the community filed a single return. Commissioner Delano determined that, while corporate entities were not generally taxable, “person” in the tax law could be read broadly enough to encompass entities. While that reading was exceptional, Delano determined that the “whole purpose and intent of the law is to collect a tax upon the income of every citizen[,] of every resident, and from all business carried on in the United States.”[43] Exempting the Shaker community, where individual Shakers had no claim on the money, would run contrary to the spirit of the tax law.[44]

Taggart saw the facts underlying the commissioner’s Shaker determination reflected in the church’s receipt of tithing. He read the commissioner’s determination more broadly than the language comfortably permits; according to his reading, the determination “requires all religious Associations to make an annual return of all profits, gains, and incomes accruing to such Association.”[45] The actual determination was more nuanced than Taggart’s interpretation; the commissioner found that a religious association could be a person for tax purposes, and thus taxable. Still, Taggart’s reading allowed him to assess tax on the church’s “profits, gains, and incomes.”

Of course, the fact that Taggart saw an opening—and perhaps a legal obligation—to assess taxes against the church itself on its income did not mean that the church owed income tax. To be taxable, the church had to have profits, gains, or incomes. Again, though, Taggart was willing to elide the details. Rather than exploring what constituted profits, gains, or incomes, he asserted that it was a “well established fact that the society of Mormons have large profits, gains, and incomes arising from certain systems adopted among them and large accounts of property held by them in trust as an association.”[46] Ultimately, Taggart’s analysis was circular: the church had large profits, gains, and incomes, and the evidence of that was that it held significant property.

With the commissioner’s ruling on the Shakers in hand, on 15 January 1870, Taggart delivered his $59,338.51 tax assessment of the church to O. J. Hollister, the collector of Internal Revenue for the Territory of Utah.[47] The question of the church’s 1868 tax liability was now out of Taggart’s hands.[48]

Where church leaders detested Taggart, their dislike did not extend to Hollister.[49] A meeting with Taggart reportedly went so badly that it ended with Taggart “heaping upon us some of his vile insults [then] he finally left in a rage. Afterwards met with Hollister who to say the least was gentlemanly.”[50]

On 21 January 1870, less than a week after Taggart delivered the assessment to Hollister, Young wrote to Hollister requesting an extension of time to pay the assessed tax. Young explained that he did not understand why tithing was taxable and that he wanted time to hear from the commissioner.[51] Hollister granted the extension and promised not to move forward with collection without first notifying Young.[52]

On 23 February 1870, Young signed Form 47 (“Claim under Circular No. 21 for Remission of Taxes Improperly Assessed”). The form required Young to explain why he believed the assessment against church income was improper. He gave two reasons why the commissioner should abate the income tax.

First, he said, the return he had made on 26 August 1868 had been “true and correct without fraud or under estimate.” Taggart’s assessment, by contrast, had been “unjust,” and Young believed Edwin Taggart had created his assessment “without having a proper knowledge of the subject-matter.” No income tax had been due for 1868. The $60,000 assessment was, quite simply, wrong.[53]

Second, Young explained “that what is called Tithing is a free gift or donation by the members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to no person but to a Trust.” Agents of the trust, he continued, used that money to help the poor, to build places of worship, and to do other “charitable and benevolent” things. Tithing did not represent any kind of quid pro quo, and the church received no “pecuniary profits or gain” from it. Finally, Young said, he had never used, nor permitted anybody else to use, tithing monies for speculative purposes. Thus, the tithing the church had received was not taxable.[54]

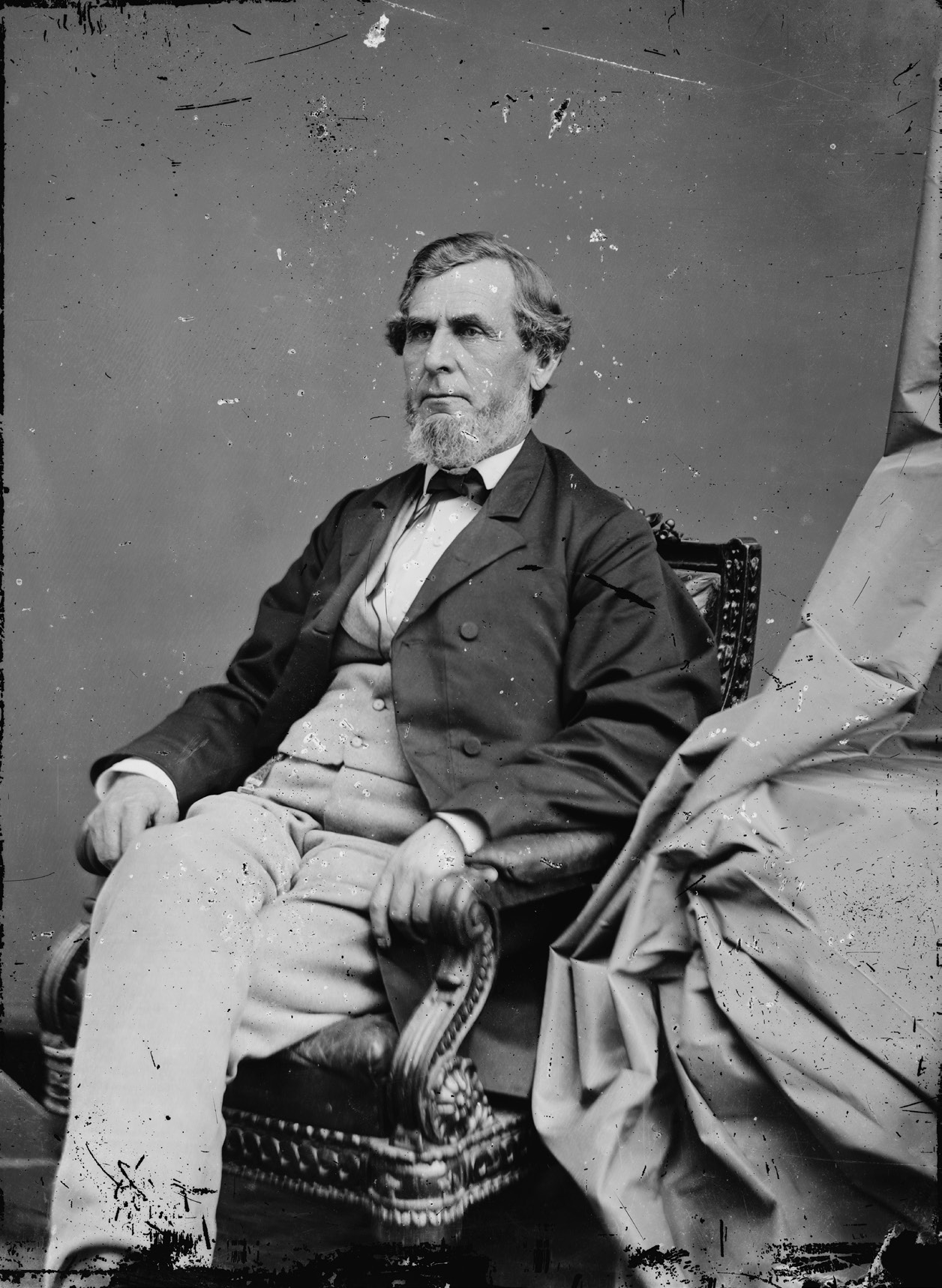

Hollister disagreed with Young’s characterization of tithing:

I believe, from all I can see & learn, that the tithing has been devoted to laudable enterprises in general, perhaps always, saving & excepting, begging your pardon the perverting of Christians to Mormonism. But I cannot see it to be in the nature of a voluntary contribution, nor a fund from which neither the Chh nor individuals derive gain or profit.[55]

O. J. Hollister. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-130758.

O. J. Hollister. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-130758.

Still, Hollister was unflaggingly polite in his correspondence with church leaders,[56] even while he firmly rejected their arguments. He excused his rejection, explaining to Young that, while he had nothing to do with making the tax law, and that he did not hold the office of collector by choice, he felt obligated to do his duty within that office. And, in the course of his duty, he was “dissatisfied with your explanation & statements, even your depositions.”[57] His dissatisfaction, he explained, arose primarily with respect to the alleged voluntariness of tithing. He did not believe that tithing was a voluntary contribution based on “statements I find in your Church history.”[58]

In his opinion, tithing could be called “voluntary” only in “a guarded sense if at all.”[59] Both Latter-day Saint scripture and Young speaking in his capacity as president of the church referred to tithing as a law, binding on its members. He explained that church members’ tithing obligations were treated by the church as an account due, and that account ran with them throughout their lives.[60]

Hollister was especially struck by the penalties imposed on non-tithe payers. Notably, he claimed, nonpayment of tithing could lead to excommunication. And excommunication was not merely inconvenient. According to Hollister, excommunication “involves, from the peculiar nature of the association & the (former) isolation of Utah, the theatre of its action, temporal as well as spiritual ruin if not loss of life.”[61] But even if nonpayment did not lead to excommunication in practice, Hollister believed that the enforcement or not of tithe paying was immaterial. Whether or not it was externally enforced, “the payment of tithing has been enforced upon the people at large by their own conscience, pricked thereto by the unflagging efforts of their priesthood for whose maintenance tithing was instituted of, according to the law (Mormon) & the prophets.”[62] Tithing was obligatory, if not in the legal sense, at least in the moral and practical sense.

In writing to the commissioner, Hollister raised one final objection to Latter-day Saint tithing escaping taxes—it was used in “what I regard as purposes of General Speculation, such as the construction of Canals, Railroads, and Public Buildings, Establishing Manufactures, Publishing Books and newspapers, improving if not acquiring farms & city-lots, sustaining a vast system of proselytizing and immigrations, &c &c.”[63] The important question was not whether these various enterprises were laudable, Hollister continued. The question was whether tithing represented “a source of profit or gain to the church or to individuals.” Hollister affirmed that it did, and was thus taxable.[64]

Still, Hollister’s conclusions were not a complete loss to the church. In examining the tithing accounts (and corroborating those numbers with various other balance sheets he had seen), he calculated that the church actually had about $85,058 of net income (that is, receipts reduced by costs associated with those receipts) in 1868. He recommended that, after a $1,000 exemption, the church be assessed a tax of 5 percent of that amount, plus an additional 50 percent penalty for “not making returns as required by law.”[65] Although Hollister concluded that tithing represented taxable income, he believed that the church should only pay about $6,300, rather than the almost $60,000 Taggart had assessed.

Church leaders were happy about Hollister’s recommendation for a reduced assessment. Although he had not accepted their argument that tithing was a voluntary donation not subject to taxation, he had accepted the accuracy of the tithing numbers they had presented to him.[66] Still, this significant reduction did not fully placate them, and Young pressed for the government to abate his tax liability.

After all, as Wells pointed out, other churches also raised money. Reverend Foote, for instance, had raised money to build a church in Salt Lake City. And other churches raised money to support the poor, publish tracts, and provide for missionaries. Did they pay taxes on donations they received, Wells asked. No, “and our Revenue Officers know it.”[67] Wells believed that, far from being fair, Taggart’s assessments were “gottn [sic] up against the Church in a spirit of persecutive animosity and [were] simply vexatious.”[68]

Both the amount of tax assessed and the idea that tithing represented taxable income troubled church leaders. But, while both of those objections to the assessment were deeply salient, the imposition of the income tax posed at least one other significant problem for the church: the majority of tithing the church received was paid in-kind.[69] Cash was scarce in Utah, and residents had little opportunity to earn cash before the early 1870s.[70] In fact, of the $143,372.77 that the tithing office received in 1868, only $25,114.12 was in cash.[71] The rest was paid in labor or in goods.[72] Young explained to Commissioner Delano that tithing donations were nearly always received in-kind.[73]

Thus, church leaders believed that the tax system was incompatible with the way they collected tithes. Young’s clerk balked at the idea that in-kind goods could even constitute income subject to taxation. However, if it were subject to taxation, he asked Representative Hooper ironically,

upon what principle should a money income tax be paid thereon? If such free will offerings must be taxed, it will be necessary for Government to build store houses as they will have to receive such tax in kind—there is no other way to pay such a tax, there is not money enough in the country to do it with.[74]

Later, he posed this precise argument to Hollister, contending “that if delivering potatoes to the Church was Church income—then the tax should be paid in potatoes, as they were disbursed to the poor & the work-men in kind & no money was realized at all.”[75]

Even if noncash donations represented income, church leaders believed it was unfair as applied to the church. Wells explained that the “labor, produce, merchandize &c. in which tithing is paid, if reduced to a cash basis for any one year, would scarcely pay the tax for that same year as now assessed.”[76] Ultimately, their argument that in-kind receipts were not income proved unavailing, and Young had to convince Commissioner Delano that tithing was not income, irrespective of the form in which it was paid.

Hon. Columbus Delano of Ohio. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-cwpbh-00685.

Hon. Columbus Delano of Ohio. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-cwpbh-00685.

Young made five substantive arguments for why the 1868 tax should be abated. First was a legal argument. He quoted the instructions provided to assessors, which said that gifts of money were not taxable income.[77] He assumed that if gifts of money were exempted from taxation, so were gifts of goods.[78]

And were tithe payers making gifts to the church? Absolutely, said Young. He disputed the affidavits Taggart had collected from nonpayers who claimed that enforcement of tithe paying led to “‘temporal as well as spiritual ruin, if not the loss of life.’ I totally deny their veracity, and brand the latter assertion as a malicious insinuation (as black as the soul that invented it.)”[79] While nonpayment of tithing may have been an additional factor in the excommunication of certain individuals, it had rarely, if ever, been the sole cause of excommunication.[80] He doubted that half the members of the church paid tithing, and he himself “sometimes [paid] a little, but not as much as I should.”[81] In any event, Young denied excommunication was as ruinous as Taggart and Hollister believed—he knew of individuals who had joined the church for financial advantage, and others who had left it for the same reason.[82]

Second, Young argued that the money used to pay tithing was both taxable and taxed in the hands of the donors.[83] They did not get to deduct the amount they paid in tithing, so taxing their donations to the church would represent double taxation.[84]

Third, he argued, Taggart’s assessment had been excessive. As evidence, he pointed to Hollister’s recalculation of church income.[85] Church leaders also believed it was excessive because of the nature of tithing in-kind and the decentralized nature of collecting and remitting it. A bishop, Young’s clerk explained, might collect twenty gallons of molasses as tithing, which would be recorded as a $40 tithe, meaning the church would owe $2 of taxes on the tithing. But it would cost the church $13.20 to transport it to Salt Lake, and its market price would be between seventy-five and ninety cents per gallon. At the low end, then, the twenty gallons would bring in $15, and the church would have a net revenue of $1.80.[86] If the assessor used church records to determine income, then, it was possible for the assessed tax to exceed the church’s net revenue on the tithing.

Young’s fourth and fifth arguments were that Taggart’s facts were wrong. Taggart believed that tithing was used for speculation. Young denied that this was the case.[87] Tithing was used primarily to build houses of worship and to pay clerks and other employees of the church. These individuals “of course pay their individual tax on their saleries [sic].”[88] In fact, an 1868 circular the church had sent to local bishops explained how the church used tithing: “The Tithing and offerings due the Church, if punctually paid, will enable us to carry on the Public Works, do the Church business, and sustain the poor.”[89]

He also believed that the penalty for failure to file was inappropriate, because he had, in fact, made a return within the requisite ten days.[90] Young’s clerk and two other church members were willing to testify that the return had been delivered and that Taggart received it, put it “in a drawer, or receptacle, & said ‘I shall take no notice of that,’”[91] insinuating, perhaps, misfeasance by Taggart.

At the same time Young was appealing the assessment, he was also making contingency plans in case the commissioner upheld Taggart’s determination that tithing represented taxable income. To limit the future harm to the church of such a conclusion, Young pursued two paths. On the one hand, he lobbied the government for relief. On the other hand, he looked at other ways he could structure the receipt of tithing to eliminate or reduce the amount of taxes owed on tithing receipts.

Young frequently wrote about the income tax issue to William H. Hooper, Utah’s territorial delegate to Congress.[92] Hooper, a merchant who had “converted to Mormonism,”[93] was charming and could often win over even those most opposed to the church.[94]

Church leaders did not immediately ask Hooper for his help in dealing with the tax assessment, but it brought him into the loop early in the process. On 20 January 1870—mere months after Taggart’s original assessment—T. W. Ellerbeck, one of Young’s clerks, wrote Hooper with details both about the tax assessment and about the nature and uses of tithing. Young, Ellerbeck assured Hooper, had not spoken to him about the notice from Hollister, “but I thought I would let you know that you may have the facts before you.”[95]

Church leaders in Utah continued to keep Hooper in the loop throughout the tax collection process. In March, Wells wrote to Hooper, updating him both on Hollister’s actions and on claims made by the church. Wells offered to send copies of various documents and affidavits the church had provided to the government in contesting the tax assessment; again, Wells did not ask for any particular help with the issue but did keep Hooper meticulously informed.[96]

By May church leaders began to request Hooper’s help. Young asked Hooper to examine Internal Revenue returns to discover the tax paid by Utah liquor manufacturers. He explained conspiratorially that “I should not like to affirm that Mr Taggert [sic] is in partnership here in that business, but from what has been presented to my notice I have no doubt of such being the case.”[97] By December, rumors had reached Utah that John W. Douglass, who had recently succeeded Delano as the commissioner of the Bureau of Internal Revenue, had instructed Hollister to collect the assessment Taggart had made against Young, while dropping the penalties. The church leaders requested that Hooper find out if it were true and, if so, to find out whether they could appeal the commissioner’s decision to the Secretary of the Treasury “in the same way as in land cases, where an appeal can be taken from the Commissioner to the Sec. of the Interior.”[98]

At the end of 1870, Young decided to take advantage of Hooper’s position as a representative of Utah and (indirectly) of the church. Even still, Young did not request any particular action from Hooper. Rather, church leaders provided him with explanations and suggestions in hopes that “you will get them presented at the proper place at the proper time.”[99]

Hooper seems to have found the proper place and time in mid-December of 1870, when he reported that he had spoken with Senator John Sherman on the Senate Committee on Finance. Hooper argued—apparently unsuccessfully—that recent legislation provided an exemption to the church from paying taxes on their income. He also argued for the suspension of collection.[100]

In case Young’s arguments proved unavailing and Hooper’s influence failed to convince the government that the income tax did not apply to tithing, Young and other church leaders began to think about how they could minimize the effects of income tax on tithing in the future. Ultimately, Young came up with two ideas and appeared ready to institute either or both of them.

First, he pointed out to other church leaders, the various bishops of the church collected much of the tithing. Moreover, in many cases they dispersed the tithing receipts themselves. Young argued that because they were responsible for tithing and “often disburse it at their own discretion, in fact, they are local Trustees-in Trust.”[101] If tithing was taxable, Young wanted the bishops outside of Salt Lake County to be assessed on the tithing they received and pay the income tax on it themselves. This was not merely to reduce Young’s personal tax bill. The income tax law provided a $1,000 exemption for each taxpayer; taxpayers only paid taxes on their income in excess of the exemption amount.[102] If each bishop were to pay taxes on the amount of tithing he received, Young reasoned, each bishop would get the $1,000 exemption.[103] Effectively, in Taggart’s assessment of the church for 1868, he permitted Young a single $1,000 exemption. In 1870, the church had 195 wards, led by 195 bishops.[104] If the government assessed tithing separately to each bishop, that would reduce the amount of tithing on which the church owed taxes by up to $195,000. Strategically, then, if tithing represented taxable income to the church, spreading it out among more taxpayers made significant sense.

Second, Young was prepared to invoke a nuclear option: ending tithing altogether. Rather than allowing the government to “rob us of our hard earnings which are donated to sustain the poor and other charitable purposes,” the church would have to “carry on our public works and assist the poor by some other method.”[105] The day after Young proposed to end tithing, Wells replied that he thought it was a good idea, and that he was preparing to publish a notice announcing the new no-tithing policy.[106] That same day, Young wrote a letter to the bishops throughout Utah, in which he said that church leaders “wish the people to pay no more tithing[,] nor you [bishops] to make any more returns to the General Tithing Office, until further notice.”[107]

Dropping tithing would have been a significant move, both religiously and financially. In Latter-day Saint scripture, God declared tithing “a standing law unto [my people] forever” (Doctrine and Covenants 119:4). Moving away from tithing would belie this divine declaration.

Financially, moving away from tithing would also represent a significant sacrifice and challenge to the church. Tithing made up a significant portion of its revenue—a decade after Young proposed ending tithing, it represented about $540,000 of the church’s $1 million revenue.[108] If the church were to give up tithing, it would have to replace at least half of its revenue, with no guarantee that the Bureau of Internal Revenue would not treat the replacement as taxable as well.

In the end, after nearly a year and a half of battle between the church and Taggart over the taxability of tithing revenue, Young and the church proved victorious. Their victory, though, represented a sudden and unexpected reversal, the kind of deus ex machina conclusion that would grace the ending of a poorly written play.

On 3 December 1870, the New York Times reported what it believed to be the end of the battle. John W. Douglass, the acting commissioner of the Bureau of Internal Revenue, had (mostly) upheld Taggart’s assessment. The Utah church, Douglass said, owed taxes on its tithing revenue, as assessed by Taggart. Harper’s Weekly reported gleefully to its national audience that “Brigham Young thought his income tax too large last year. He declared it was erroneous, and asked to have it abated. Not being so successful as he desired, the venerable householder revenges himself by complaining of the extravagance of his family.”[109]

Although Douglass found the church liable for taxes on its tithing revenue, his decision did not represent a complete loss for the church. He determined that Young had neither failed to file a return nor filed a fraudulent one. As a result, he relieved Young of the fifty-percent penalty. Hollister had immediate permission, though, to collect the $39,559 in back taxes that the church owed.[110]

About two weeks after Douglass’s decision, Young received a telegram informing him that collection would be postponed for ninety days.[111] (There seems to have been some confusion on this point: about a week later, Hollister received a telegram from Acting Commissioner Douglass instructing him to not “postpone collection of income tax assessed against Brigham Young if you think the chance of final collection will be thereby in any degree lessened.”)[112] As Young raced to figure out what to do, perhaps the most consequential occurrence in the question of the taxability of Latter-day Saint tithing happened: on 14 December 1870 Grant nominated Alfred Pleasonton as commissioner of Internal Revenue.[113] The next day, the Senate consented to his appointment,[114] and he was appointed effective 3 January 1871.[115]

Pleasonton had served as a general in the Civil War and had been an Internal Revenue collector in New York.[116] He also fiercely opposed the income tax. Shortly after his appointment as commissioner, Pleasonton wrote to the Committee on Ways and Means. In his letter, he said that he considered the income tax to be “the most obnoxious to the people, being inquisitorial in its nature and dragging into public view an exposition of the most private pecuniary affair of the citizen.” In light of the fact that, in his opinion, “the evils more than counterbalance the benefits from its longer retention,” he recommended “its unconditional repeal.”[117]

Gen. Alfred Pleasonton. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-cwpbh-00558.

Gen. Alfred Pleasonton. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-cwpbh-00558.

At roughly the same time Pleasonton was arguing for the repeal of the income tax, he also looked at Young’s appeal of his tax assessment. He concluded that, while income the Utah-based church received from speculative investments qualified as taxable income, “the tithes collected by said Church from its members were voluntary donations and as such not subject to an income tax.” As such, he ordered Taggart to make a new assessment consonant with his guidance, and to notify him so that he could abate the previous assessment.[118]

In the immediate aftermath of Pleasonton’s decision, church leaders celebrated. Optimistically, Wells reported to Young that “Taggart is rather abandoning the tithing matters.”[119] The church would no longer have to rethink how it would raise revenue and would not have to abandon their eternal “standing law.” Young wrote that “the Commissioner of Internal Revenue has decided that our Tithing is not taxable and we shall arrange our affairs so that those who desire, will have the privilege of paying their Tithing & donations.”[120]

This optimism proved unfounded, though. Even after Pleasonton’s determination, Taggart was unsatisfied. Church leaders reported that Taggart “affirms that his office is loaded down with the weight of evidence contrary to the commissioner’s ruling that tithing is a free donation.”[121] They also reported that he intended to collect affidavits to prove that “Comr Pleasanton’s decision regarding the income tax on tithing is erroneous; that tithing is not voluntary, &c.”[122]

In spite of Taggart’s continued insistence that tithing represented taxable income, church leaders took advantage of Pleasonton’s decision. In response to Edwin Taggart’s request that the church file a return for 1870, Young responded that he could not, because

I have made diligent examination of the facts, and cannot find that any of the free donations of tithes received by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have been used in any way so as to produce any income whatever for the year aforesaid, and I am therefore unable to make out any return of income for said Church for said year.[123]

After this, questions of the taxability of tithing largely disappeared from church leaders’ correspondence. Even with Pleasonton’s suspension as commissioner in the middle of 1871[124] and his replacement by Douglass that December,[125] the church’s fears about the income tax did not return.

Conclusion

Throughout the nineteenth century, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints had a fraught relationship with the federal government. The zero-sum battle over the practice of polygamy occupies the most salient example of that fraught relationship, but it is not the only example, and its conclusion—with the church ultimately giving up its peculiar institution—is not the only possible conclusion.

Brigham Young’s conflict over taxes provides an alternative window into conflict between the church and the federal government. Similar to the conflict over polygamy, church leaders saw (perhaps rightly) the imposition of the income tax as an assault on their religion and people. With the income tax issue, though, church leaders engaged with the government, following the procedures demanded by the Board of Internal Revenue and becoming more sophisticated in their understanding and use of the law.

Perhaps that difference resulted from the fact that the income tax itself did not represent an existential threat to their religious beliefs. Unlike the various federal antipolygamy laws, the income tax was not written to eliminate a particular church belief or practice; in fact, it was not written with the church members in mind at all. The law itself was not the problem, just Taggart’s application of the law. As such, church leaders merely had to demonstrate why his interpretation was wrong.

Churches, including The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, exist within a society of laws. This battle over the Civil War income tax, with its increasingly sophisticated give and take, presaged a future where the church could interact with those laws, not by avoiding them or denying their validity, but by actually engaging with the law.

Notes

[1] Unknown sender [probably Brigham Young] to Daniel H. Wells, 3 January 1871, box 73, folder 33, Brigham Young office files: President's office files, 1843–1877, Communications, 1854–1877, Letters and telegrams, 1870 December–1871 January, 1870 April, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[2] Unknown sender [probably Young] to Wells, 3 January 1871.

[3] John P. Taggart to Francis M. Lyman, 18 August 1869, box 49, folder 31, Brigham Young office files: 1869–1870 March, Church History Library.

[4] Revenue Act of 1862, ch. 119, § 90, 12 Stat. 433.

[5] John C. Chommie, The Internal Revenue Service (New York: Praeger, 1970), 8. In fact, the Tariff Act of 1789, which provided revenue to the federal government, was the first substantive piece of legislation Congress passed under the Constitution. David E. Birenbaum, “The Omnibus Trade Act of 1988: Trade Law Dialectics,” University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Business Law 10, no. 4 (22 September 1988): 655. Congress also raised some revenue through the sale of federal land, but very little from taxing its own citizens and residents directly. Chommie, Internal Revenue Service, 8.

[6] John M. Dobson, Two Centuries of Tariffs: The Background and Emergence of the U.S. International Trade Commission (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1976), 1.

[7] Peter Andreas, Smuggler Nation How Illicit Trade Made America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 17.

[8] Bryan T. Camp, “Theory and Practice in Tax Administration,” Virginia Tax Review 29, no. 2 (22 September 2009): 229.

[9] Joint Resolution Imposing a Special Income Duty, 13 Stat. 417 § 1 (4 July 1864) (creating Office of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue); Joe Thorndike, “An Army of Officials: The Civil War Bureau of Internal Revenue,” Tax Notes 93, no. 13 (24 December 2001): 1739.

[10] John G. Turner, Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet (Cambridge: Belknap Harvard, 2014), 170.

[11] Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830–1900 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005), 235.

[12] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 239.

[13] James M McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom; the Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 850.

[14] Joseph A. Ranney, In the Wake of Slavery: Civil War, Civil Rights, and the Reconstruction of Southern Law (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2006), 5.

[15] Ranney, In the Wake of Slavery, 6.

[16] Ranney, In the Wake of Slavery, 8.

[17] Sarah Barringer Gordon, The Mormon Question: Polygamy and Constitutional Conflict in Nineteenth-Century America, Studies in Legal History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 120.

[18] Ronald W. Walker, Wayward Saints: The Godbeites and Brigham Young (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 212–13.

[19] Quentin Wells, Defender: The Life of Daniel H. Wells (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2016), 300.

[20] Wells, Defender, 300.

[21] Gordon, Mormon Question, 13.

[22] Gordon, Mormon Question, 111.

[23] Gordon, Mormon Question, 111–13.

[24] Tax assessors were so unpopular among taxpayers that, in 1872, Congress eliminated the position entirely, shifting the assessor’s duties to district collectors and revenue agents. Thorndike, “An Army of Officials,” 1759.

[25] John Taggart, Testimony, 11 February 1870, H.R. Rep. 41st Cong. 2d sess. Rep. no. 21 pt. 2, 1 (1870).

[26] John Taggart, Testimony, 11 February 1870.

[27] John Taggart, Testimony, 11 February 1870. The accusation is probably not unfounded; when assistant assessor Lyman informed Young of Taggart’s initial inquiry into church finances, he also explained how he had responded in a manner that avoided providing Taggart with substantive information. Lyman ended with the hope that “I have not done wrong in this matter.” Francis M. Lyman to Brigham Young, 27 August 1869, box 49, folder 31, Brigham Young office files: 1869–1870 March, Church History Library.

[28] “An Act to Replenish Brothels,” Deseret News, 2 March 1870.

[29] Brigham Young to Columbus Delano, 18 March 1870, box 49, folder 31, Brigham Young office files: 1869–1870 March, Church History Library.

[30] Taggart to Lyman, 18 August 1869.

[31] Lyman to Young, 27 August 1869.

[32] John P. Taggart to Brigham Young, 25 September 1869, box 49, folder 31, Brigham Young office files: 1869–1870 March, Church History Library.

[33] Brigham Young to John P. Taggart, 29 September 1869, Brigham Young office files: Letterbooks, 1844–1877, Letterbook, v. 11, 1868 August 27–1870 February 9, Church History Library.

[34] Brigham Young to Columbus Delano, 24 January 1870, Brigham Young office files: Letterbooks, 1844–1877, Letterbook, v. 11, 1868 August 27–1870 February 9, Church History Library.

[35] Yda Addis Storke, A Memorial and Biographical History of the Counties of Santa Barbara: San Luis Obispo and Ventura, California (Chicago: Lewis, 1891), 541. The Bureau of Internal Revenue was plagued by patronage appointees. Thorndike, “An Army of Officials,” 1754. There is no reason to believe that such a system would have looked askance at nepotism.

[36] Edwin Taggart, Testimony, 11 February 1870, H.R. Rep. 41st Cong. 2d sess. Rep. no. 21 pt. 2, 2 (1870).

[37] Edwin Taggart, Testimony, 11 February 1870.

[38] Tax return, signed by Taggart on behalf of Young, for 1868, box 49, folder 31, Brigham Young office files: 1869–1870 March, Church History Library.

[39] Young to Delano, 18 March 1870.

[40] David J. Herzig and Samuel D. Brunson, “Let Prophets Be (Non) Profits,” Wake Forest Law Review 52, no. 5 (2017): 1128.

[41] Amasa A. Redfield, A Hand-Book of the U.S. Tax Law, (Approved July 1, 1862) with All the Amendments, to March 4, 1863: Comprising the Decisions of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Together with Copious Notes and Explanations. For the Use of Tax-Payers of Every Class, and the Officers of the Revenue of All the States and Territories. (New York: J. S. Voorhies, 1863) , 326.

[42] John Taggart, Testimony, 11 February 1870.

[43] Redfield, Hand-Book of the U.S. Tax Law, 326.

[44] Redfield, Hand-Book of the U.S. Tax Law, 326.

[45] Taggart to Lyman, 18 August 1869.

[46] Taggart to Lyman, 18 August 1869.

[47] O. J. Hollister to Brigham Young, 18 February 1870, box 49, folder 31, Brigham Young office files: 1869–1870 March, Church History Library.

[48] Although this article focuses on Taggart’s attempt to tax the Church of Jesus Christ on its tithing, that was not the only tax controversy between church leaders and Taggart. He also attempted to tax the city of Salt Lake for issuing currency, under the theory that issuing currency transformed the city into a bank. Church leaders argued that the putative currency was, in fact, IOUs, and that the city could not be held responsible if Utahns circulated those IOUs as if they were currency. Daniel H. Wells to W. H. Hooper, 30 January 1871, Brigham Young office files: Letterbooks, 1844–1877, Letterbook, v. 12, 1870 February 9–1872 March 15, Church History Library.

[49] This adoration would curdle over time, until, a decade later, Lorenzo Snow would describe a tax levied by Hollister as “illegal, unjust, and highly absurd.” Eliza R. Snow, Biography and Family Record of Lorenzo Snow: One of the Twelve Apostles of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1884), 308.

[50] Daniel H. Wells to Brigham Young, 1 January 1871, box 43, folder 16, Brigham Young office files: General correspondence, incoming, 1840–1877, Letters from Church leaders and others, 1840–1877, Daniel H. Wells, 1871 January–February, Church History Library.

[51] Brigham Young to O. J. Hollister, 21 January 1870, Brigham Young office files: Letterbooks, 1844–1877, Letterbook, v. 11, 1868 August 27–1870 February 9, Church History Library.

[52] O. J. Hollister to Brigham Young, 22 January 1870, box 49, folder 31, Brigham Young office files: 1869–1870 March, Church History Library.

[53] Form 47, 23 February 1870, box 49, folder 31, Brigham Young office files: 1869–1870 March, Church History Library.

[54] Form 47, 23 February 1870.

[55] O. J. Hollister to Brigham Young, 2 March 1870, box 49, folder 31, Brigham Young office files: 1869–1870 March, Church History Library.

[56] His general politeness may be why, even as he tried to collect income taxes from Young, church leaders never placed him in the “ring” that was out to get the Saints.

[57] Hollister to Young, 2 March 1870.

[58] Hollister to Young, 2 March 1870.

[59] O. J. Hollister to Columbus Delano, 7 March 1870, box 49, folder 31, Brigham Young office files: 1869–1870 March, Church History Library.

[60] Hollister to Delano, 7 March 1870. In fact, in an earlier unsent draft of the letter, Hollister put particular emphasis on the treatment of tithing as an account due, writing that it was “a matter of book a/

[61] Hollister to Delano, 7 March 1870. In the unsent draft, Hollister emphasized that nonpayment of tithing led to excommunication and that Young had suggested that apostates—including those who had been excommunicated—should be killed. Perhaps he moderated that point because, as he explained in the unsent draft letter, “I do not believe, myself, that as a rule the law has been enforced to the letter that men have been cut off from the Church for not settling their tithing & then killed for being apostates.” Hollister to Delano, [] March 1870 [unsent].

[62] Hollister to Delano, 7 March 1870.

[63] Hollister to Delano, 7 March 1870.

[64] Hollister to Delano, 7 March 1870.

[65] Hollister to Delano, 7 March 1870.

[66] Daniel H. Wells to W. H. Hooper, 15 March 1870, Brigham Young office files: Letterbooks, 1844–1877, Letterbook, v. 12, 1870 February 9–1872 March 15, Church History Library.

[67] Daniel H. Wells to W. H. Hooper, 2 January 1871, Brigham Young office files: Letterbooks, 1844–1877, Letterbook, v. 12, 1870 February 9–1872 March 15, Church History Library.

[68] Wells to Hooper, 2 January 1871.

[69] Moreover, the in-kind tithing was not always worth its purported value. One bishop received a letter telling him the eggs he sent to the tithing office “were all rotten. The butter too was in a terrible state and had to be retubbed before reaching the city. Please don’t forward any more rotten eggs, and butter put up so poorly.” A. Milton Musser to Daniel Daniels, 17 August 1870, Brigham Young office files: Letterbooks, 1844–1877, Letterbook, v. 12, 1870 February 9–1872 March 15, Church History Library.

[70] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 139.

[71] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 139.

[72] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 139.

[73] Young to Delano, 24 January 1870.

[74] T. W. Ellerbeck to W. H. Hooper, 20 January 1870, Brigham Young office files: Letterbooks, 1844–1877, Letterbook, v. 11, 1868 August 27–1870 February 9, Church History Library.

[75] T. W. Ellerbeck to W. H. Hooper, 17 December 1870, Brigham Young office files: Letterbooks, 1844–1877, Letterbook, v. 12, 1870 February 9–1872 March 15, Church History Library. To the extent that it is important, there is no question under the modern federal income tax that income received in-kind is subject to taxation. See Treas. Reg. § 1.61–1(a) (1957) (“Gross income includes income realized in any form, whether in money, property, or services.”).

[76] Daniel H. Wells to H. S. Eldredge, 24 January 1871, Brigham Young office files: Letterbooks, 1844–1877, Letterbook, v. 12, 1870 February 9–1872 March 15, Church History Library.

[77] Brigham Young to Columbus Delano, 29 September 1870, Brigham Young office files: Letterbooks, 1844–1877, Letterbook, v. 12, 1870 February 9–1872 March 15, Church History Library.

[78] Young to Delano, 18 March 1870.

[79] Young to Delano, 18 March 1870. Young’s clerk ironically emphasized the implausibility of the argument that nonpayment of tithing would lead to spiritual and temporal ruin, given the fact that the church did not receive 10 percent of the territorial income. He wrote, “Mr Taggarts report to the dept. concerning the tithing & how it is forced out of the people under threats of eternal damnation or something of that kind. Well now—if his statement of what the tithing would be is correct—how does it comport with what was actually received? There can be no manner of doubt as to the correctness of the Statement of the tithing products received by the Trustee in Trust at his office & the Genl Tithing Store, as set forth in the first statement, and it knocks into pie his statement about the full tithing be forced out of the people.” T. W. Ellerbeck to W. H. Hooper, 2 January 1871, Brigham Young office files: Letterbooks, 1844–1877, Letterbook, v. 12, 1870 February 9–1872 March 15, Church History Library.

[80] Young to Delano, 18 March 1870.

[81] The former assistant assessor of 8th Division District of Utah in conversation with President B. Young on the subject of the Government taxing the Tithing or donations paid by the people called Latter day Saints, box 49, folder 32, Brigham Young office files: 1870 July–1871, Church History Library.

[82] Young to Delano, 18 March 1870.

[83] While theoretically Young is correct, in fact, it is unlikely that most donors to the church paid taxes on their income. As a result of Congress’s raising the exemption amount to $1,000 in 1867, only 0.7 percent of the population paid the federal income tax. Steven A. Bank, Kirk J. Stark, and Joseph J. Thorndike, War and Taxes (Washington: Urban Institute Press, 2012), 48. While the incomes of the Latter-day Saint population likely did not mirror that of the country at large, it still seems likely that approximately 99 percent of members did not pay any income tax, whether or not they paid the required tithes.

[84] Young to Delano, 29 September 1870.

[85] Young to Delano, 29 September 1870. Young’s clerk asserted that Taggart’s assessment was “enormously exaggerated.” Ellerbeck to Hooper, 8 January 1871.

[86] Young to Delano, 29 September 1870.

[87] Even if it were, his clerk argued, the tithing would not represent income; the church should only pay taxes on returns from the speculative investments, not the capital it invested. Ellerbeck to Hooper, 17 December 1870. Ellerbeck’s argument misapprehends the government’s position here: the government was arguing that, even if tithing donations to the church were free-will offerings, they would be exempt from taxation only if they were used for charitable purposes. Ellerbeck, by contrast, assumed that tithing was not income.

[88] Ellerbeck to Hooper, 17 December 1870.

[89] Edward Hunter Letter, 1 November 1868, box 32, folder 16, Brigham Young office files: General correspondence, incoming, 1840–1877, General letters, 1840–1877, Ho-K, 1868, Church History Library.

[90] Young to Delano, 29 September 1870.

[91] Ellerbeck to Hooper, 17 December 1870.

[92] Wells, Defender, 237.

[93] Walker, Wayward Saints, 93.

[94] Walker, Wayward Saints, 221.

[95] Ellerbeck to Hooper, 20 January 1870.

[96] Wells to Hooper, 15 March 1870.

[97] Brigham Young to W. H. Hooper, 26 May 1870, Brigham Young office files: Letterbooks, 1844–1877, Letterbook, v. 12, 1870 February 9–1872 March 15, Church History Library. Whether or not Taggart was “in partnership” with liquor manufacturers, the accusation was not necessarily unfounded. The Bureau of Internal Revenue suffered from significant corruption surrounding the evasion of liquor taxes, including the so-called “Whiskey Ring,” formed and led by Internal Revenue agents. Thorndike, “An Army of Officials,” 1754.

[98] Daniel H. Wells to W. H. Hooper, 8 December 1870, Brigham Young office files: Letterbooks, 1844–1877, Letterbook, v. 12, 1870 February 9–1872 March 15, Church History Library.

[99] Wells to Hooper, 2 January 1871.

[100] W. H. Hooper to “Friend” [probably Brigham Young], 19 December 1870, box 62, folder 14, Brigham Young office files: Utah delegate files, 1849–1872, W. H. Hooper to Brigham Young, 1859–1872, 1870 December–1871, Church History Library.

[101] Brigham Young (per Daniel H. Wells) to W. H. Hooper, 15 March 1870, Brigham Young office files: Letterbooks, 1844–1877, Letterbook, v. 12, 1870 February 9–1872 March 15, Church History Library.

[102] Revenue Act of 1867, ch. 169, § 13, 14 Stat. 478.

[103] Young (per Wells) to Hooper, 15 March 1870.

[104] Deseret Morning News Church Almanac, 2006, 634.

[105] Unknown sender [probably Young] to Wells, 3 January 1871.

[106] Wells to Young, 4 January 1871.

[107] Brigham Young to the Bishops throughout our settlement, 4 January 1871, MS 4148, Church History Library.

[108] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 353.

[109] “Home and Foreign Gossip,” Harper’s Weekly, 14 January 1871, 35. The Harper’s Weekly article continued with a fictional dialogue between Young and an interlocutor, before explicitly making a connection between Young’s endeavor to have the income tax abated and polygamy. After the fictionalized Young complains about the expenses women cause him to incur, the writer asks, “If women make all this expenses and annoyance, why in the world does the gentleman trouble himself with so many of them?”

[110] “Brigham Young’s Income Tax: The Income from Mormon Church Property Decided to Be Taxable—Brigham Young’s Points Overruled,” New York Times, 3 December 1870.

[111] Brigham Young to Daniel H. Wells, 14 December 1870, box 73, folder 33, Brigham Young office files: President's office files, 1843–1877, Communications, 1854–1877, Letters and telegrams, 1870 December–1871 January, 1870 April, Church History Library.

[112] J. W. Douglass to O. J. Hollister, 20 December 1870, box 49, folder 32, Brigham Young office files: 1870 July–1871, Church History Library.

[113] Journal of Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States vol. 17 (1901): 581.

[114] Journal of Executive Proceedings of the Senate, 587.

[115] Romain Huret, American Tax Resisters (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), 42.

[116] Huret, American Tax Resisters, 42.

[117] “Letters from Commissioner Pleasonton on the Income Tax,” Chicago Tribune, 27 January 1871.

[118] Alfred Pleasonton to John P. Taggart, 18 January 1871, box 49, folder 32, Brigham Young office files: 1870 July-1871, Church History Library.

[119] Daniel H. Wells to Brigham Young, 14 January 1871, box 43, folder 16, Brigham Young office files: General correspondence, incoming, 1840–1877, Letters from Church leaders and others, 1840–1877, Daniel H. Wells, 1871 January–February, Church History Library.

[120] Brigham Young to John McCarthy, 23 January 1871, MS 6183, Church History Library.

[121] Wells to Hooper, 30 January 1871. Disagreements between rulings issued by the commissioner of Internal Revenue and interpretations of the tax law in the field were not unique to Taggart; they appeared to be symptomatic of the “growing pains” of the Civil War income tax. Chommie, Internal Revenue Service, 10–11.

[122] T. W. Ellerbeck to W. H. Hooper, 14 February 1871, Brigham Young office files: Letterbooks, 1844–1877, Letterbook, v. 12, 1870 February 9–1872 March 15, Church History Library.

[123] Brigham Young to Edwin Taggart, 23 March 1871, box 49, folder 32, Brigham Young office files: 1870 July–1871, Church History Library.

[124] Pleasonton quickly clashed with Treasury Secretary George S. Boutwell, developing a view on the income tax that conflicted with Boutwell’s and publicly arguing his case in front of congressional committees. “Abolition of the Revenue Commissionership—Why?,” Chicago Tribune, 23 December 1871, 4. The August 1871 news was filled with stories of the so-called “Boutwell-Pleasonton Imbroglio.” “The Boutwell-Pleasonton Difficulty Still Unadjusted,” New York Herald, 3 August 1871. On 8 August 1871, President Grant suspended Pleasonton against Pleasonton’s will. Congressional Globe, 4 December 1871, 2.

[125] Journal of Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States 18 (1901): 137.