Egypt's New Kingdom

Krystal V. L. Pierce

By the end of the Second Intermediate Period, the thirty-year war between the Seventeenth Dynasty in Thebes and the Hyksos in the Delta was in full swing. The second-to-last ruler of the Seventeenth Dynasty died by extreme violence, as evidenced by a large horizontal axe cut in the forehead of his mummy. He was succeeded by his son, who was also not successful in expelling the Hyksos from Egypt. But a second son, named Ahmose (ruled 1548–1523 BCE), became the first king of the reunified New Kingdom and founder of the Eighteenth Dynasty.

Ahmose and the Reunification of Egypt (1548–1523 BCE)

When Ahmose succeeded to the throne, he was probably quite young, and his mother ruled in his stead. Evidence of the queen mother’s power comes from a stela at Karnak dated to the eighteenth year of Ahmose’s reign, where the king states that the queen pacified Upper Egypt, expelled rebels, and governed the land. Ahmose’s mother was provided with a lavish burial in western Thebes, and weapons placed in her coffin feature eastern Mediterranean motifs and techniques mixed with an Egyptian style, showing the foreign cultural influences that were popular in Egypt during this period. Ahmose took the Hyksos capital of Avaris, identified with Tell el-Dabaa in the eastern Delta, during the eighteenth to twenty-second years of his reign.

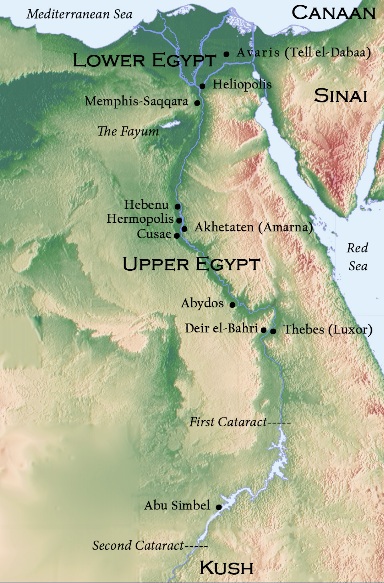

Egypt during the New Kingdom.

Egypt during the New Kingdom.

Evidence for the campaign against Avaris itself arrives from physical remains at Tell el-Dabaa, as well as contemporary temple and tomb reliefs and inscriptions. Narrative war scenes in Ahmose’s temple at Abydos show Egyptian horses and chariots, a royal battle fleet, soldiers destroying crops, and Hyksos captives and troops wearing long-sleeved fringed garments of a non-Egyptian style. Apparently, a treaty was established between Ahmose and the Hyksos that allowed the Hyksos to leave in a mass exodus.

After Avaris was taken, Ahmose followed the enemy into the southern Levant, either to destroy the remnants of the Hyksos or to exploit the vacuum left behind by their defeat and departure. He first campaigned at Sharuhen, which has been identified with a site near Gaza named Tell el-Ajjul. Archaeological destruction levels at the site are associated with this period, along with an Egyptian-style center-hall house, which may have been used as an Egyptian administrative headquarters. Ahmose then pushed northward into Phoenicia.

With the Hyksos defeated, the reunification and rebuilding of Egypt could begin. Ahmose secured the southern border at Kush (modern Sudan) and the northern border at Avaris, where excavations revealed that the Hyksos palace and fortifications were destroyed and replaced with new structures decorated with Minoan-style art. Ahmose spent his final years concentrating on a massive building program at the major religious centers of Egypt, where he focused on the traditional gods: Ptah at Memphis, Osiris at Abydos, and Amun at Thebes. At Thebes, he centered his work on the Amun temple at Karnak.

Two stelae at Karnak present Ahmose as a great benefactor to the temple, with the king rebuilding Theban tombs and pyramids destroyed by a storm. A third stela lists ritual equipment he commissioned and dedicated to the temple, including gold and silver vessels, offering tables, necklaces, and musical instruments. Ahmose was most likely buried in the area of Thebes, although his mummy had been moved in antiquity to a royal mummy cache at Deir el-Bahri, and his original tomb is unknown.

Hatshepsut, the First Female King (1473–1458 BCE)

The great religious and economic power enjoyed by the mother of Ahmose set the groundwork for Queen Hatshepsut (ruled 1473–1458), who would later become the first real female pharaoh. Just like Ahmose and his mother, when Hatshepsut’s stepson Thutmose III came to the throne, he was a small child, and so the queen acted as regent. A contemporary document states that Thutmose was the king but that Hatshepsut was actually the one who executed the affairs of Egypt. Although Hatshepsut capitalized on her role as “God’s Wife of Amun,” which supported her regency, she went further by transforming herself publicly into a male king, including giving herself a throne name. The queen added more legitimacy to her reign through scenes and inscriptions in several Theban temples, depicting her divine birth from the gods.

Obelisk of Queen Hatshepsut. A scene on a red granite obelisk at Karnak depicts Queen Hatshepsut wearing male royal regalia, including the king’s kilt and war crown, kneeling before the god Amun-Ra, who is blessing and crowning Hatshepsut as king of Egypt. The inscription reads, “Words said by Amun-Ra, Lord of the Sky, ‘I gave the entire office of kingship of the Two Lands (Egypt) to my daughter, Maat-ka-Ra (Hatshepsut), beloved of my body—Life, Prosperity, Health!’” The name, epithet, and image of Amun-Ra were removed, most likely during the reign of Akhenaten, and later restored, probably in the Ramesside Period.

Obelisk of Queen Hatshepsut. A scene on a red granite obelisk at Karnak depicts Queen Hatshepsut wearing male royal regalia, including the king’s kilt and war crown, kneeling before the god Amun-Ra, who is blessing and crowning Hatshepsut as king of Egypt. The inscription reads, “Words said by Amun-Ra, Lord of the Sky, ‘I gave the entire office of kingship of the Two Lands (Egypt) to my daughter, Maat-ka-Ra (Hatshepsut), beloved of my body—Life, Prosperity, Health!’” The name, epithet, and image of Amun-Ra were removed, most likely during the reign of Akhenaten, and later restored, probably in the Ramesside Period.

Hatshepsut constructed more building projects than any of her predecessors. In a lengthy inscription, she claims to have been the first king since the expulsion of the Hyksos to rebuild the temples of Horus at Hebenu, Thoth at Hermopolis, and Hathor of Cusae. Most of her building programs took place at Thebes. With Egypt at peace, the wealth of the country’s natural resources, such as gold from the eastern deserts and several types of stone from the quarries, was exploited to the full extent. Valuable materials also poured in from foreign locations, including cedar from Lebanon, ebony from Africa, gold from Kush, and other exotica from Punt (perhaps somewhere along the coast of east Africa).

At Karnak, Hatshepsut constructed the Eighth Pylon as a new southern gateway to the temple precinct, shifting attention away from the previous king’s gateway at the Fourth Pylon. She also built a palace for ritual activities at Karnak, where she depicted her acceptance and purification by the gods. Her great quartzite bark shrine, which was later dismantled and moved, featured scenes of processions associated with several Theban festivals, including one where Amun of Karnak visits the Luxor temple and another where Amun leaves Karnak to travel west to Deir el-Bahri and other royal temples. The latter festival was the most prized event on the Theban west bank in the New Kingdom, and Hatshepsut’s constructions described and celebrated her divine birth from Amun, which was also featured in the temple she built at Deir el-Bahri for worshiping her after her death.

Foreign excursions during Hatshepsut’s reign included trading expeditions—north to Byblos for cedar and other wood, east to the Sinai for turquoise, and south to Punt for gold, incense, ivory, panther skins, and elephants, as recorded in inscriptions at Deir el-Bahri and in the Sinai. Possible campaigns against Gaza and Sharuhen in Canaan are hinted at in the royal annals of Thutmose III, and several military expeditions were sent to Kush to quell local uprisings and exact tribute. Hatshepsut left many building remains in Kush, including a temple for Horus, where her coronation was depicted and where Thutmose III later replaced her name with the names of his father and grandfather.

Thutmose III (1479–1425 BCE)

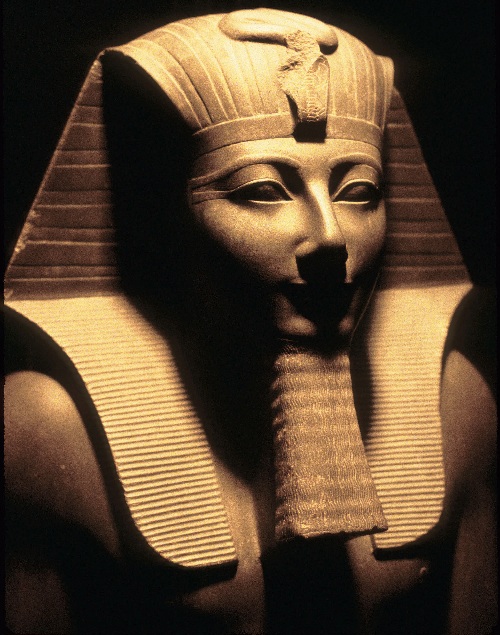

Thutmose III; Luxor Museum, Luxor.

Thutmose III; Luxor Museum, Luxor.

All traces or mention of Hatshepsut disappeared about fifteen or twenty years into her reign when her stepson and brother, Thutmose III, began his sole rule. It is unclear what happened to Hatshepsut, but Thutmose desecrated her monuments by removing and replacing her name and obscuring her building constructions, probably to eliminate the claims of her family line. The king wanted to establish a reputation in his sole rule, so he set his sights on the Levant, where gaining control of the trade routes dominated by other kings and traders would be a key advantage. This began almost two decades of campaigns in the Levant, which resulted in establishing Egyptian control over the region.

Thutmose’s first military expedition was sent to Gaza and Sharuhen in southern Canaan to stop a local rebellion. In the twenty-third year of his reign, the king left the south and planned an attack on Megiddo, a major city-state occupied by the ruler of Kadesh and protected by a group of chiefs from several of the surrounding regions. The annals of the king, which are inscribed in the Temple of Amun at Karnak, provide a detailed record of the battle. After a seven-month siege, Thutmose was successful in taking Megiddo and brought back the spoils of war to Egypt, including chariots, suits of armor, horses, other animals, and captives.

After the Battle of Megiddo, Thutmose spent the next eight years focusing on gaining or regaining control over cities in the Levant, where he sent expeditions to retain Egyptian vassals. Destruction levels at Jaffa, Akko, and Hazor could possibly correspond to his military action in the area. He replaced rebellious rulers and sent the sons of rulers back to Egypt to be raised and taught in an Egyptian manner. Vassals were taxed with a fixed portion of their harvest to be sent to Egypt, and precious metals, wood, oils, and foodstuffs were also gathered. Egyptian and Egyptian-style buildings, pottery, burials, and other objects at Beth-shean, Jaffa, Gezer, Lachish, and other sites may be evidence of Egyptian garrisons or headquarters that Thutmose set up.

In year thirty-three of his reign, Thutmose moved north on a conquest of Syrian vassals, and he recorded in the annals, on an obelisk at Karnak, and elsewhere his crossing of the Euphrates River and placement of a boundary stela. He continued to campaign and travel in the northern Levant, Lebanon, and Syria for the next decade, where he focused on stopping rebellions, setting up garrisons and administrative centers, destroying crops, hunting, accepting diplomatic envoys, marrying foreign princesses, and building and inscribing monuments.

Canaan during the New Kingdom.

Canaan during the New Kingdom.

The wars, diplomacy, and trade between Egypt and the Levant during the time of Thutmose had a profound effect on the Egyptian homeland itself. Some foreign deities began to be accepted and worshipped in Egypt, and Syrian-style glass, silver, and gold vessels became status symbols in the country. Three wives of Thutmose bore Asiatic names and were buried in wealthy tombs in western Thebes, illustrating more of a sense of diplomacy than hostility toward the region.

The building regime of Thutmose in Egypt was prolific, but the king focused on the Theban area, especially Karnak. He restructured the central area of the Temple of Amun, removing previous constructions and replacing them. He added the Sixth and Seventh Pylons, a temple to Ptah, and two shrines of granite and Egyptian alabaster. His major building project at Karnak was decorated with reliefs focused on the renewal and veneration of kingship, while his later decorating program centered on his military campaigns, with episodes of warfare and plunder lists.

Thutmose was buried in the Valley of the Kings, and his tomb is covered with black and red hieratic renditions of several netherworld texts, including one which called on the names of the sun-god to aid the king in his journey through the afterlife and another which provided the king with a map of the underworld and spells to achieve eternal life after death.

Akhenaten and the Amarna Period (1349–1332 BCE)

The successful military conquests of Thutmose III set the stage for the next three rulers of the Eighteenth Dynasty, whose reigns were marked by seven and a half decades of domestic and foreign peace, diplomacy, and affluence. A gradual shift toward a theology that centered on the sun god also took place during the reigns of those three pharaohs, culminating in the reign of Amenhotep IV (ruled 1349–1332), who made radical changes in the religion, art, architecture, and culture of Egypt during what we call the Amarna Period.

The sun god had already been set apart from the other gods as the supreme deity before the reign of Amenhotep, but it was really with his rule that all other gods became aspects of the sun god in a step beyond henotheism toward monotheism (the belief that only one god exists). In year five of his reign, Amenhotep changed his name to Akhenaten, which means, “The Creative Manifestation of the Aten,” removing the reference to the god Amun from his name and replacing it with the god Aten. Aten was depicted as a sun disc with extended solar rays terminating in human hands holding symbols of life (ankh) and power (was).

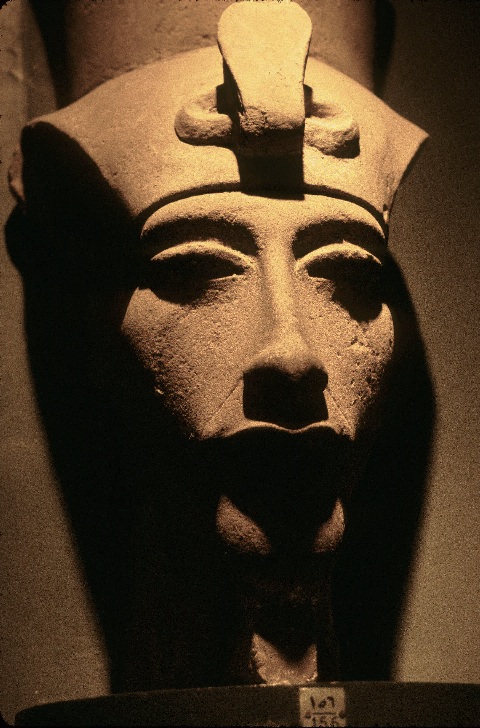

Akhenaten; Luxor Museum, Luxor.

Akhenaten; Luxor Museum, Luxor.

Akhenaten then took the extreme step of banning all other gods, in favor of Aten, campaigning to remove the names and images of the traditional gods, especially Amun. The long-established state temples were closed all over Egypt, and the festivals and processions of the gods, with the exception of Aten, were eradicated. At the Temple of Karnak in Thebes, Akhenaten began a major building program, not to Amun, but to Aten, whose name was placed in a royal cartouche, a symbol previously only reserved for the pharaoh. Aten was centralized in rituals as the “Divine Father,” ruling Egypt in the role of celestial co-regent with the king.

Akhenaten then went even further in severing his links with Amun by building a new capital at the site of modern Amarna. He called it Akhetaten, meaning “The Horizon of the Aten.” Thebes had been the religious center of Egypt throughout the New Kingdom, and the move to a new site must have brought opposition from the priests of Amun there, as all money and power was diverted to the new capital. All construction at Thebes was halted, with the exception of updating the king’s name to Akhenaten and destroying the names and images of Amun and the other gods.

In the new city, the king and his wife Nefertiti were conveyed via royal chariots in a daily procession that essentially replaced the earlier divine processions of the gods that took place during national festivals. The two temples dedicated to Aten were of a radically new nature, with open courtyards to the sky and featuring many small altars and having little shadow or darkness. Traditionally, Egyptian temples began with an open court and then continued with more rooms that gradually became smaller and darker until the innermost sanctuary, which held the shrine and image of the god in total darkness. Since Aten was essentially the sun disc in the sky, his temples needed to be open to the heavens, which did not require a man-made statue of the god.

Although the god Aten was there in the sky for all to see, the deity could not be worshipped by anyone but the pharaoh and the royal family. Personal piety consisted of total loyalty to the king, and non-royal citizens kept small shrines with altars and stelae dedicated to the royal family instead of to the usual local deities. In private tombs at Amarna, the royal family also dominated, and hymns to Aten were addressed and given solely by the pharaoh, instead of by the tomb owner.

It is unclear how Akhenaten’s religious reforms affected Egyptian citizens outside of Amarna. Most scholars believe that they continued to worship traditional and local gods. On the other hand, those outside Amarna must have been affected by the newly created official language, today called “Late Egyptian,” which was closer to the common spoken language of Egypt.

Akhenaten inherited a country that was at peace with its neighbors, and only one rebellion in Kush was recorded during his reign. Beginning in the 1880s CE, an archive full of cuneiform texts was discovered at Amarna that recorded correspondence between the royal court and foreign rulers. The letters show evidence that a new powerful enemy had emerged in northern Syria—the Hittites—which led to the loss of some of Egypt’s northernmost territory. The Amarna Letters, along with texts from the Hittite archives, record information about rebellious vassals, the detainment of Canaanite rulers, northern coastal campaigns, deportations of foreigners to Egypt, requests for trade, and the establishment of military governors and bases in the Levant.

Akhenaten ruled for less than two decades. His successor must have been either the son of Nefertiti and Akhenaten or Nefertiti herself. Nefertiti became an official co-regent with her husband and held a prominent position at Amarna. She even had a structure entirely dedicated to her at Karnak, where she was shown performing rituals previously only reserved for the king, such as smiting the enemy. She may have been another female king.

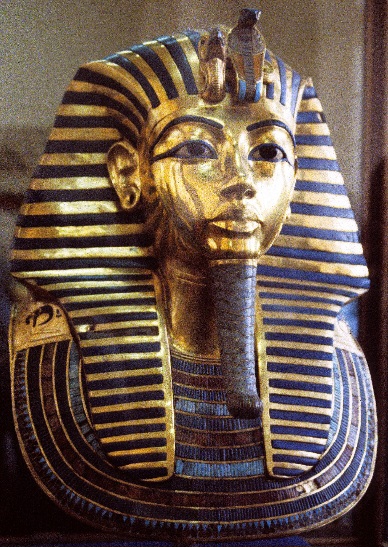

Tutankhamen and the Response to the Amarna Period (1328–1319 BCE)

The king following Akhenaten ruled only for a few years before he or she disappeared and was replaced by a new pharaoh named Tutankhaten. Tutankhaten, who came to the throne as a young child, was probably the son of Akhenaten but not of Nefertiti. Unlike some of the adolescent kings who came before him, like Thutmose III, Tutankhaten did not have a strong female ruler like Hatshepsut to act as co-regent. But under the influence of his military commander, in the first or second year of his reign, Tutankhaten abandoned the city of Amarna, restored the worship of the traditional gods, made Thebes again the religious capital, and replaced the Aten in his name with Amun. The newly named king, Tutankhamen (ruled 1328–1319), undertook a major campaign to restore the traditional temples, demolish monuments to Akhenaten, and reorganize the administration of the country. His Restoration Stela describes the state of Egypt in the aftermath of the Amarna Period, where the temples of the gods were in ruins and their worship abolished, resulting in the gods abandoning Egypt, not answering the people’s prayers, and not assisting the army in expanding Egypt’s borders.

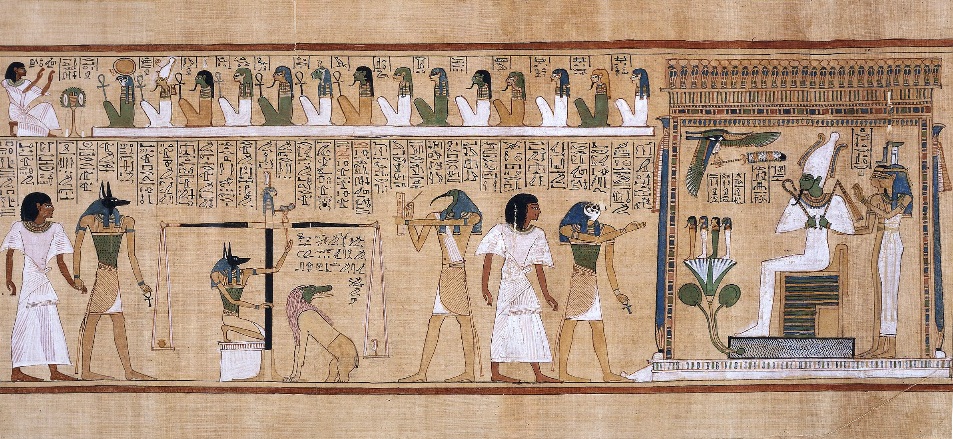

The royal response to the end of the Amarna Period was not the only powerful change seen in the reign of Tutankhamen and the rest of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Tombs belonging to the elite also underwent major alterations. At Memphis and Thebes, private tombs began to resemble the layout of divine and royal temples. Statues that were usually reserved for offerings placed in divine temples now appeared in private tombs, and the grave took on the role of a private mortuary temple for the owner. Artistic representations in these tombs no longer included the traditional scenes of the owner’s professional occupation but instead concentrated on the deceased adoring Ra, Osiris, and other gods, as opposed to the sole adoration of the king during the Amarna Period.

During the Amarna Period, the army was restricted to actions within Egypt, including Akhenaten’s removal of the names, images, and worship of the traditional gods. Under Tutankhamen and his co-regent army general, the military again attempted to reassert Egyptian authority in Kush and the Levant. Tutankhamen died before he reached the tenth year of his reign and was buried in the Valley of the Kings. Around the time of his death, the Egyptian army was in a major confrontation with the Hittites in Syria, where, according to texts in the Hittite archives, the Egyptians were defeated. Tutankhamen’s widow wrote to the Hittite king requesting an alliance with the Hittites through her marriage to a prince, who would become the new king of Egypt. The Hittite ruler did indeed send his son to Egypt, but the prince was murdered before he could reach the queen.

Sety I and the Nineteenth Dynasty (1301–1290 BCE)

The death of young Tutankhamen, with no royal heir, led to a series of three rulers who were military men of non-royal blood. With the first two pharaohs, the Eighteenth Dynasty was finished, and with the third, the Nineteenth Dynasty began. Sety I was the second king of the Nineteenth Dynasty. He was also the High Priest of Seth, a god worshipped at the site of Avaris in the Delta, the hometown of his family.

Although he reigned for just over a decade (1301–1290), Sety is credited with the bulk of the repair of the traditional temples, where he restored both the inscriptions of the pre-Amarna pharaohs and the names and effigies of the god Amun. He had an ambitious building program in which he constructed new temples and expanded old religious centers. In the north, he expanded the temple of Seth at Avaris and built a cenotaph temple for Osiris at Abydos. The cenotaph featured a list of kings and royal ancestors that skipped the Amarna Period completely, leaving out Akhenaten. In Thebes, Sety built the Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak, an enormous room (102 by 53 meters) containing 134 huge columns inscribed in deep relief and painted. Sety also built a mortuary temple on the west bank and restored Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el-Bahri. He also opened and re-opened the gold and stone mines in the Eastern Desert.

Hypostyle Hall, Temple of Amun, Karnak, Luxor.

Hypostyle Hall, Temple of Amun, Karnak, Luxor.

Abroad, Sety sent military operations to the Levant in the north, Libya in the west, and Kush in the south. In the first year of his reign, he began a small-scale campaign against Bedouin on the highway from Egypt to Gaza in Canaan. Egypt needed to reassert authority in the Levant for resources, and Sety continued northward, going against the Apiru in the central highlands, conquering several cities and cutting cedar timber to send back to Egypt. Battle reliefs at the Amun temple in Karnak and royal stelae record these military events, including an inscription left at Beth-shean that is now on display in the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem. Later in his reign, Sety moved into territory held by the Hittites, conquering Kadesh and causing the Amurru (the Amorites) to defect to the Egyptian side. This led to another war with the Hittites, which resulted in the Egyptian loss of both Kadesh and the Amurru vassals. Sety’s presence in the Levant can also be recognized at other locations where Egyptian and Egyptianized architecture and material culture are located. He faced incursions by Libyan tribes along the western border of the Delta, and he sent raids to Kush to take captives for labor and security of the gold mines located in the region. The reliefs in the Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak document many of the king’s military campaigns and feature a new realistic artistic style, influenced by Amarna Period art, showing battle scenes in a less traditional and symbolic manner and more like an actual historical event.

Ramesses II and Merenptah (1290–1214 BCE)

Sety appointed his son and heir, Ramesses II, as co-regent while the prince was still a child. This resulted in one of the longest reigns in Egyptian history, with Ramesses ruling over six decades (1290–1224). Ramesses had at least seven Great Royal Wives, leading to a large progeny of forty daughters and forty-five sons, many of which died before the pharaoh and were buried in a massive tomb in the Valley of the Kings. He used the myth of the divine king to legitimize his rule, but by year eight of his reign, he began the process of deifying himself. Colossal statues called “Ramesses-is-God” began to appear in all of the major temples in Egypt, where they received a regular rite and were publically worshipped along with other deities. He is even shown making offerings to his own deified self. Elsewhere in Egypt, the king usurped hundreds of statues and temples of previous rulers, especially those of Akhenaten’s father and the pharaohs of the Twelfth Dynasty, which was considered to be the classical period of Egyptian history that could serve as a model for a perfect post-Amarna Period Egypt.

Ramesses focused on building projects in the north, where he designed underground galleries for the burial of sacred Apis bulls of Ptah at Saqqara and expanded the site of Avaris, which became the new royal residence. Some scholars identify Avaris with the biblical Raamses (Exodus 1:11) and Rameses (Exodus 12:37). Due to the site’s location near the road leading from Egypt to the Levant, Avaris became the most important international trade center and military base in Egypt. The pharaoh also built at Luxor, where he added a courtyard to the temple of Amun at Karnak and constructed his own mortuary temple, the Ramesseum, directly across the Nile from the divine temple. He also built a series of eight rock temples in Lower Kush, including two at Abu Simbel.

The king’s first military campaign took place in Kush, where reliefs at a rock temple show the quelling of a local rebellion and a young Ramesses with two of his children. In the Eighteenth Dynasty, Egyptian princes rarely appeared in royal reliefs, but they are prominent in Ramesside-period scenes, with the emphasis now on the hereditary nature of kingship. The first military campaign to the Levant took place in year four of his reign, and although he was able to re-conquer Amurru, the Hittite king regained control of the vassal soon after. In the following year, Ramesses went to war against the Hittites in the famous Battle of Kadesh. Both sides claimed victory, and Ramesses featured the battle in a huge propaganda campaign on the walls of all the major temples in Egypt.

Because a growing kingdom of Assyria was threatening the Hittites across several regions, the Hittite king opened peace discussions with Ramesses, which led to a formal treaty and Ramesses’s marriage to a daughter of the Hittite king. Under the treaty, the Egyptians lost Kadesh and Amurru, but international trade blossomed under the new stability. Egyptian and Egyptian-style architecture, burials, and objects appeared at many sites reaching across the northern and southern Levant in this period, and Egyptianized deities were worshipped in temples at Beth-shean and Gaza. A Levantine presence was felt in Egypt as well, with Asiatic deities like Baal, Resheph, and Astart worshipped in Lower Egypt, where many foreigners were in residence.

Ramesses was succeeded by his son Merenptah (ruled 1224–1214). Only a few monuments are known from Merenptah’s ten-year reign. In the early years of his rule, he subdued the rebellious vassals Ashkelon, Gezer, and Yenoam, as recorded on his famous Victory Stela. This inscription records the first reference to the word Israel, with the hieroglyphic sign marking the word as a people or tribe, and not as a location or country. The actual focus of the Victory Stela was the invasion of a massive coalition of Libyan tribes into Lower Egypt. There is evidence of major crop failure and famine around the Mediterranean during this time, and this is believed to be a cause of mass migrations around the region. Merenptah recorded in an inscription at Karnak that he sent grain to starving Hittites during a famine.

Mass migrations of people from the Aegean and western Anatolia swept across the eastern Mediterranean, destroying the centers of Mycenaean Greece and causing the collapse of the Hittite Empire. Those groups, together called the Sea Peoples, joined with the Libyan tribes upon reaching Egypt, bringing women, children, and cattle with the plan to settle in the country, first by penetrating the western Delta and then by moving south. Merenptah confronted the Libyans and Sea Peoples at Memphis and Heliopolis. He was victorious, crediting the triumph to the god Atum blessing his son Merenptah.

Ramesses III and the End of the New Kingdom (1195–1086 BCE)

The first king of the Twentieth Dynasty ruled for only a few years and was succeeded by his son Ramesses III, who reigned for over three decades (1195–1164). In the fifth year of his reign, Ramesses was forced to fight off groups of Libyan tribes who had penetrated from the west. It was only three years later that the Sea Peoples launched an attack via both land and sea in the Delta. Invaders had already destroyed the Hittite capital of Hattusas in modern Turkey and Alalakh and Ugarit in Syria. They settled their people in each area as it was conquered. By the time the Sea Peoples reached Egypt, Ramesses was well prepared, having reinforced troops and garrisons in both the Levant and Egypt. Because of these preparations, the Sea Peoples never succeeded in conquering Egypt.

Foreign excursions by Ramesses included expeditions to Punt and Atika, which can probably be identified with the copper mines at Timna in the Arabah, where inscribed votive objects and a rock stela dating to the time of Ramesses were found. In Egypt proper, the king’s main project consisted of a large mortuary temple at Medinet Habu, across the Nile to the west of Thebes, decorated on the exterior with scenes of the battle with the Sea Peoples.

Toward the end of Ramesses’s reign, there were clear signs of major problems in Egypt. A contemporary record reports that there was such corruption in Egypt that he had to inspect and reorganize the temples and donate huge amounts of land to the great temples in Thebes, Memphis, and Heliopolis. The donations were so substantial that by the end of his reign, one-third of all cultivable land in Egypt was owned by the temples, and three-fourths of this land was owned by the Temple of Karnak at Thebes. This upset the balance of power between the temple and the state, allowing the priests to control the Egyptian economy.

Funerary Temple of Rameses III, Medinet Habu, showing the vibrant colors of paint that once covered most of the carved surfaces in Egyptian temples.

Funerary Temple of Rameses III, Medinet Habu, showing the vibrant colors of paint that once covered most of the carved surfaces in Egyptian temples.

The loss of control over Egyptian finances led to an economic crisis, where grain prices soared and state employees were not paid their monthly rations. In the twenty-ninth year of Ramesses’s reign, state-employed men from the area of the Valley of the Kings stopped working in the first organized labor strike recorded in history. Strikes, economic crises, and repeated raids by Libyan nomads led to a gradual breakdown of the centralized state. An assassination attempt on the pharaoh originated among the officials and women of the royal harem. The ringleaders included the scribe of the harem and one of Ramesses’s wives, whose goal was to place her son on the throne after the king was murdered. The conspirators were also found in possession of magical spells and wax figurines intended to help in the assassination. According to the records of the court hearings and sentences, many of the guilty party were forced to commit suicide.

The remainder of the Twentieth Dynasty saw eight kings all named Ramesses, who mostly had short reigns characterized by a lack of building construction and a loss of control over the Levantine territories. Problems in the economy and bureaucracy of Egypt continued, including political corruption, inflation, crime, and famine. Those issues led to the rise of the priestly class in Egypt and lessened the power of the pharaoh, resulting in a civil war and military coup at the end of the dynasty. With the end of the Twentieth Dynasty came the end of the New Kingdom (c. 1086) and a decentralized state at the beginning of the Third Intermediate Period.

For Further Reading

Bard, Kathryn. An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015.

Robins, Gay. The Art of Ancient Egypt. Rev. ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008.

Shaw, Ian, ed. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Simpson,William K. The Literature of Ancient Egypt. New Haven: Yale University, 2003.

Taylor, John H. Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Hatshepsut's Funerary Temple.

Hatshepsut's Funerary Temple. A scene on an altar from a house in Amarna depicts Akhenaten (left) and Queen Nefertiti (right) embracing and kissing three of their daughters underneath the sun-disc of the Aten, whose solar rays and hands bestow the hieroglyphic sign for life (ankh) to the royal family. Because only royalty could directly worship Aten, private Egyptians dedicated offerings to the king and queen at these altars in their private houses instead. The scene showcases many of the significant artistic changes that appeared in the Amarna Period, including exaggerated body proportions and facial features. Neues Museum, Berlin.

A scene on an altar from a house in Amarna depicts Akhenaten (left) and Queen Nefertiti (right) embracing and kissing three of their daughters underneath the sun-disc of the Aten, whose solar rays and hands bestow the hieroglyphic sign for life (ankh) to the royal family. Because only royalty could directly worship Aten, private Egyptians dedicated offerings to the king and queen at these altars in their private houses instead. The scene showcases many of the significant artistic changes that appeared in the Amarna Period, including exaggerated body proportions and facial features. Neues Museum, Berlin. Death mask of Tutankhamen; Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

Death mask of Tutankhamen; Egyptian Museum, Cairo.