Picturing the Crucifixion

Dawn C. Pheysey

Dawn C. Pheysey, “Picturing the Crucifixion,” in Behold the Lamb of God: An Easter Celebration, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, Frank F. Judd Jr., and Thomas A. Wayment (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2008), 155–64.

Dawn C. Pheysey was the curator of religious art at the Brigham Young University Museum of Art when this was published.

As an instrument of the Crucifixion, the cross has become a universal emblem of Christ’s suffering as well as a symbol for Christianity. For centuries it has been a constant reminder to believers of the Savior’s sacrifice. In the Beholding Salvation exhibition at Brigham Young University Museum of Art, held November 17, 2006–June 16, 2007, a diversity of images of the Crucifixion prompted reflections on the Savior’s atoning sacrifice. Depictions such as these have touched countless worshippers throughout the centuries.

The shape of the cross itself extending in four directions represents the universal effect of the Savior’s Atonement. The early Christian Church acknowledged that Paul, in his letter to the Ephesians, was speaking of Christ’s cross when he wrote,

“That ye . . . may be able to comprehend with all saints what is the breadth, and length, and depth, and height; and to know the love of Christ, which passeth knowledge” (Ephesians 3:17–19).[1]

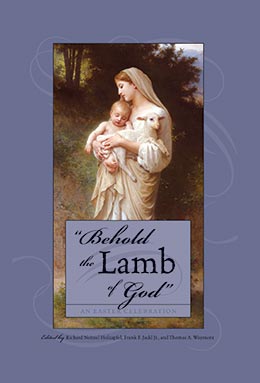

Over time, the varied nature of Crucifixion images has reflected changing religious thought and emphasized prevailing doctrinal teachings. For example, in linking the Fall of Adam with the Crucifixion and Resurrection of the Savior, medieval writers maintained that Christ’s Crucifixion occurred at the site of Adam’s burial.[2] Thus 1 Corinthians 15:22, “For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive,” takes an artistic form in images such as the 1511 engraving of the Crucifixion from the Engraved Passion series, by Albrecht Dürer (fig. 1). The skull at the base of the cross alludes not only to Golgotha as “the place of a skull,” but also specifically to Adam’s own skull.[3]

In the 1550 engraving of Calvary, by Giovanni Battista Franco (fig. 2), the crucified Savior occupies the central cross and the two condemned criminals are located on either side of Him, as recorded in Matthew and Mark (see Matthew 27:38; Mark 15:27). According to the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, the names of the two thieves were Dismas (the good thief on the right of Christ) and Gestas (the bad thief on the left). One method artists used to clearly differentiate these malefactors from Christ was to represent them as bound or tied to the cross, although they would have surely suffered the same Roman method of execution as did Christ. The anguish and the contorted bodies of the two thieves in juxtaposition with the dignity and majesty of the Savior offered another very obvious distinction. An additional convention derived from the medieval practice of associating size with holiness often resulted in the two thieves being depicted significantly smaller than the Savior.[4]

In accordance with the custom of placing a placard with the name and offense of the accused at the head of the cross, Pilate ordered the inscription, “Jesus of Nazareth the King of the Jews,” to be written in three languages—Hebrew, Latin, and Greek (see John 19:19–20). Artists usually used an acronym of the Latin Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeotrum (INRI) to identify the cross of Jesus (figs. 1 and 4).

Not all images of the Crucifixion were created simply to illustrate biblical text. Some were intended to stir up guilt in the sinner for causing the suffering of Christ, while others were meant to offer hope to the believer through the healing power of the Atonement.

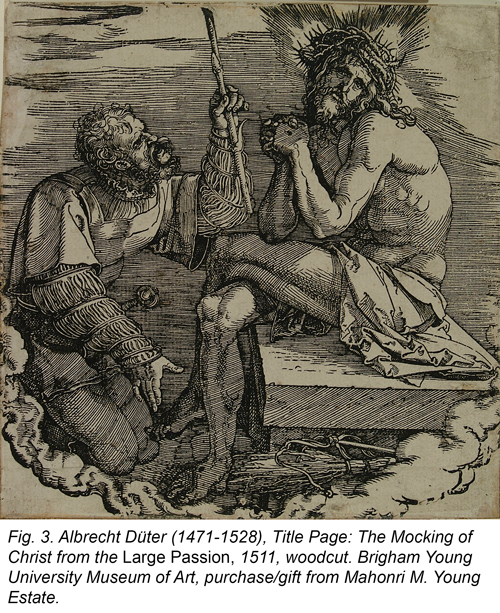

This first image type was intended to stir up guilt, but it does not depict a specific event; it is a devotional image that encourages the viewer to contemplate the suffering of Christ. It is called the Man of Sorrows or Suffering Christ in which the Savior, surrounded by the instruments of the Passion, prominently displays the wounds of the Crucifixion. These pictorial representations were developed from the Catholic doctrine of “Perpetual Passion,” an idea popularized in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.[5] Asserting that man was culpable in the eternal suffering of Christ, these images were intended to elicit strong feelings of remorse on the part of the sinner and to deter further transgressions. In Albrecht Dürer’s Title Page: The Mocking of Christ from the Large Passion series (fig. 3), Christ confronts the viewer as He displays the wounds in His hands and feet while He is seated on the lid of the sepulchre. This visual message was supplemented with a devotional poem. In the poem, Christ appeals to the viewer to cease from the sins that cause Him to suffer anew:

These cruel wounds I bear for thee, O man,

And cure thy mortal sickness with my blood.

I take away thy sores with mine, thy death

With mine—a God Who changed to man for thee.

But thou, ingrate, still stabb’st my wounds with sins;

I still take floggings for thy guilty acts.

It should have been enough to suffer once

From hostile Jews; now, friend, let there be peace![6]

This devotional image type was meant to encourage repentance through feelings of guilt.

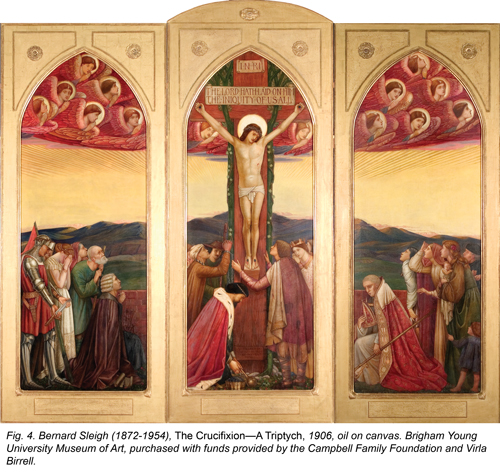

A second type of Crucifixion image, however, communicated salvation rather than condemnation. An excellent example of this is Bernard Sleigh’s The Crucifixion—A Triptych, an altarpiece commissioned for the chapel in London’s Holloway Prison in 1906 (fig. 4). The inscription at the head of the cross, “The Lord hath laid on Him the iniquity of us all,” made the altarpiece particularly poignant for its imprisoned viewers. Cognizant of his audience, Sleigh includes a man in chains at the foot of the cross who pleads for forgiveness and mercy. The painting also portrays a wide range of historical and symbolic figures dressed in contemporary costume, worshipping the Savior. Standing immediately to the left of the cross, the artist appears as a shepherd, most likely referring to the role of the shepherds at Jesus’s birth and also to the artist’s Welsh ancestors who were shepherds for many generations. [7] The artist’s wife, Stella, and their two young children are pictured on the far right.[8] By appearing as participants in the worship of the crucified Christ, the artist and his family invite believers to do likewise and place themselves within the context of the scene.

To expand this universal implication, Sleigh also incorporates four figures symbolic of key pillars of society: a knight (military), a judge (law), a king (government), and a bishop (religion). Each bows his head or knee to the Savior, offering up an emblem of his earthly power and authority. The knight holds out a broken sword, symbolic of the end of all war (see Isaiah 2:4). The king places before the judge a torn scroll and removes his crown to signify Christ as the new Judge, Lawgiver, and King (see Isaiah 33:22). The bishop, too, removes his miter and lowers his crosier, submitting to the supreme “Bishop of [our] souls” (1 Peter 2:25). By transforming the Crucifixion into a contemporary event and representing this cross-section of mankind, the work engages the viewer in an intimate manner.

Both the condemning and saving types of Crucifixion images were intended to evoke emotional responses from the viewer: one draws in the believer with guilt while the other draws in the believer with love. Although these two approaches seem diametrically opposed, they both anticipate the same result of bringing believers unto Christ. Regardless of the original tenets these artworks were intended to express, we as believers can ascribe personal understanding and meaning to these images that transcend doctrinal differences and bring us closer to Christ. [9]

In his epistle to his son Moroni, Mormon counseled that Christ’s “sufferings and death” were among those things that should “rest in [our] mind[s] forever” (Moroni 9:25). President Gordon B. Hinckley echoed this sentiment when he said:

[No one] must ever forget the terrible price paid by our Redeemer, who gave His life that all men might live—the agony of Gethsemane, the bitter mockery of His trial, the vicious crown of thorns tearing at His flesh, the blood cry of the mob before Pilate, the lonely burden of His heavy walk along the way to Calvary, the terrifying pain as great nails pierced His hands and feet, the fevered torture of His body as He hung that tragic day. . . .

We cannot forget that. We must never forget it, for here our Savior, our Redeemer, the Son of God, gave Himself, a vicarious sacrifice for each of us.[10]

Notes

[1] See Gertrud Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, vol. 2 The Passion of Christ (Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society, 1972), 93.

[2] See Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, 130–31.

[3] See James Hall, Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art (New York City: Harper & Row, 1979), 81.

[4] See Hall, Dictionary, 83.

[5] See Erwin Panofsky, Albrecht Dürer (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1945), 1:138–39.

[6] These verses, written by Benedictus Chelidonius, were added to the title page of the 1511 edition of the Large Passion series (Panofsky, Albrecht Dürer, 1:139).

[7] See Bernard Sleigh, “Memoirs of a Human Peter Pan,” unpublished autobiography, 1941–42. Information provided by Roger Cooper.

[8] Information provided by Warren Winegar of Warren Winegar Fine and Decorative Arts, New York City.

[9] See S. Kent Brown, Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, and Dawn C. Pheysey, Beholding Salvation: The Life of Christ in Word and Image (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2006), 81–82.

[10] Gordon B. Hinckley, “The Symbol of Our Faith,” Ensign, April 2005, 2–6.