The Temple Site

Richard O. Cowan, "The Temple Site" in A Beacon on A Hill: The Los Angeles Temple (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 11–26.

1921 President Grant approves Saints settling in California (October 29)

1921 Church leaders inspect but ultimately decline temple site offered by Harry Culver (December)

1923 Los Angeles Stake is organized (January 21)

1937 Temple site is purchased on Santa Monica Boulevard (March 23)

Board of architects is appointed to design temple

The end of World War I brought a spirit of optimism to the United States that lasted a decade. During these years, record numbers of Americans, including Latter-day Saints, sought to realize their dreams in the Golden State. Between 1920 and 1930, 1,900,000 out-of-state migrants entered, and of these 1,368,000 settled in Southern California. It was the largest internal migration in the history of the United States, nearly ten times the size of the gold rush of the 1850s and the railroad land boom of the 1880s.

As in the past, the nation’s trend was reflected in the Church. The number of California Latter-day Saints increased more than fivefold, from 3,967 in 1920 to 20,599 in 1930.[1] In fact, Latter-day Saint growth was greater than that of the population as a whole. The Mormon share rose from 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 250. Church members came particularly for advanced education, a mild climate, an interesting and stimulating culture, and the comparatively favorable salaries and working conditions. The educational magnet quickly gave the Church a literate, enlightened membership, and out of this comparatively small group came a disproportionately large number of future business, political, Church, and other leaders.

Heber J. Grant at the Ocean Park dedication.

Heber J. Grant at the Ocean Park dedication.

The Santa Monica area was an example. While settlement of Ocean Park—the coastal community immediately south of Santa Monica—had begun in the 1870s, it accelerated after 1902 when the Los Angeles Pacific (later Pacific Electric) Interurban Line connected the beach resorts with downtown Los Angeles. Many of the new immigrants, including a substantial number of Latter-day Saints, settled in the hilly area just east of the town, which became known as Ocean Park Heights. By 1920 this community was growing rapidly, and in 1924 it officially changed its name to Mar Vista.

Despite the Church’s encouragement of growth outside the Intermountain area, some members still voiced concerns about settling elsewhere. For example, in 1921 the Ocean Park Saints wrote President Heber J. Grant asking if they were out of harmony with Church policy by living there. He answered their letter in person during one of his frequent visits to Southern California. At a special meeting on Saturday, October 29, he assured them that “at the present time the idea of a permanent Mormon settlement at Santa Monica was in full accordance with Church policies.”[2] Ten months later he would return to dedicate their new chapel. The first modern stake outside of the traditional “Mormon” intermountain area would then be organized just a few months later at Los Angeles on January 21, 1923.

Since Brigham Young had mentioned that “in process of time the shores of the Pacific may be overlooked from the temple of the Lord,”[3] there had been talk of a California temple. While the early Church had not been strong enough to warrant the construction of one of these sacred structures, the many talented, faithful Latter-day Saints now coming to California made thoughts of a temple more plausible.

Various Temple Sites Considered

The group inspecting the offered temple site. From left to right: Charles Short, Everard L. McMurrin (local attorney and mission president’s son), Elder Rudger Clawson of the Twelve, Presiding Bishop Charles W. Nibley, Anthony W. Ivins (President Grant’s Second Counselor), Mary Ellen (Mrs. Joseph W.) McMurrin, Joseph W. McMurrin (California Mission President), Lucile McMurrin (their daughter), President Heber J. Grant, and Harry Culver. The automobile was Culver’s Pierce Arrow. (Leo J. Muir)

The group inspecting the offered temple site. From left to right: Charles Short, Everard L. McMurrin (local attorney and mission president’s son), Elder Rudger Clawson of the Twelve, Presiding Bishop Charles W. Nibley, Anthony W. Ivins (President Grant’s Second Counselor), Mary Ellen (Mrs. Joseph W.) McMurrin, Joseph W. McMurrin (California Mission President), Lucile McMurrin (their daughter), President Heber J. Grant, and Harry Culver. The automobile was Culver’s Pierce Arrow. (Leo J. Muir)

The opening years of the twentieth century were a time of rapid growth and wild real estate promotion in Southern California. As early as 1916, promoters discussed organizing a new city to be known as Ocean Heights, extending from Sawtelle on the north to Playa del Rey on the south. However, chambers of commerce in surrounding communities—including Santa Monica, Ocean Park, Venice, Inglewood, and Culver City—opposed this move because they believed the new municipality would be unable to properly care for roads in its area. They noted that the new city would be larger in area than Santa Monica or Venice but would have a smaller population than either.[4] No record of an official incorporation has been found, but apparently the designation Ocean Heights continued to be used.

In 1921 Harry Culver, a Los Angeles–area real estate developer, offered to give the Church a six-acre site in Ocean Heights valued at about $50,000 (well over $600,000 in the early twenty-first century since the value of Southern California real estate has far outpaced the general inflation rate of the dollar), plus an additional contribution of $50,000 if the Church would build a $500,000 temple there. In December of that year, only a few weeks after President Grant had made his reassuring visit to the Ocean Park Saints, he and other General Authorities went to Los Angeles to inspect this property. He reported that “the people making the offer for the temple site near Los Angeles are enthusiastic over the prospect, as are the many Church members there.”[5]

At first Church leaders were favorably impressed with this offer but eventually declined because of the financial commitment to temples in Alberta and Arizona. Furthermore, as Elder B. H. Roberts observed, “temples are not built to further real estate schemes or enterprises; temple locations and temple buildings stand apart from all such considerations.”[6] Despite this disappointment, Southern California Saints continued to cherish the thought that a local temple would one day grace their area.

The street signs at the intersection of McCune and Wasatch. (Linda Gerber)

The street signs at the intersection of McCune and Wasatch. (Linda Gerber)

Church leaders hand-picked George W. McCune, a Utah native who was then serving as president of the Eastern States Mission with headquarters in New York City, to become the first president of a new stake in Los Angeles. He arrived in Southern California in September 1922 and became stake president four months later on January 21, 1923. He quickly became involved in real estate enterprises. With other Latter-day Saints, he organized the California Intermountain Investment Company. They purchased forty acres in Ocean Park Heights for development. McCune built his own home there and hoped to attract other Church members as neighbors. They even named two streets Wasatch and McCune to resonate with potential Mormon investors. In this area was the 200-foot Mar Vista Hill on which McCune later donated property to the Church as a possible temple site.

Depression difficulties and the expense of long-distance travel kept the California Saints yearning for their own temples. Meanwhile, these Church members made hundreds, if not thousands, of trips to Mesa in Arizona and to Salt Lake City or St. George in Utah to do temple work. But these lengthy journeys took a regrettable toll, and brought tragedy.

One of these tragic events occurred late Friday night, February 23, 1934, when thirty-six members of the Home Gardens Ward in southeastern Los Angeles left the Mesa Temple to return home. They were traveling in a bus owned by the Los Angeles Stake Genealogical Society. Slightly after one o’clock Saturday morning, the bus encountered a sharp detour where the highway was being rebuilt. Oil-burning warning lights had been set out, but they had been extinguished by winds and heavy rain. The driver was unable to make the turn safely, and the bus overturned. Passengers were thrown about the bus, and some were ejected through doors and windows. Six passengers were killed and many others were seriously injured. Emergency medical crews had to come from Wickenburg, over twenty-six miles away. At the request of the Los Angeles Stake presidency, the Church appropriated funds to care for the injured. Until this time, progress toward a California temple had been slow. But news of this tragedy must have intensified interest in having temples closer to the Saints.

The Search Intensified

Heber J. Grant, David Howells, George McCune, and their wives. (CHL)

Heber J. Grant, David Howells, George McCune, and their wives. (CHL)

As Church membership continued to mushroom in Southern California, interest in erecting a temple there increased. General Church leaders formed a committee headed by another Utah native, David P. Howells, to find suitable sites. A financier who was active in Los Angeles business circles, Howells also served as bishop of the Adams and then Wilshire Wards. He worked closely with Church President Heber J. Grant and in effect became his personal representative in securing the temple site.[7] He had also previously secured the site in an exclusive section of Los Angeles for the landmark Wilshire Ward chapel and Hollywood (later Los Angeles) Stake Center.

There were widely differing ideas about where the temple should be located. “Most Church members favored a site in the downtown area or in the eastern part of the city, which was more developed than the western section. Several times sites were found, but on more than one occasion desirable properties were taken off the market when the owners learned that the property would be used for a Mormon temple.” Other sites “were not approved by the Brethren in Salt Lake City,” including a location in Pico Heights just west of downtown, another near Griffith Park on Los Feliz Boulevard east of Western Avenue, one on Olive Hill on Vermont between Hollywood and Sunset, and a lot on the very prominent corner of Santa Monica and Wilshire Boulevards in Beverly Hills.[8]

President Heber J. Grant, who frequently visited the Los Angeles area, personally participated in the search for a temple site. On May 3, 1936, for example, he visited “Temple Hill” near the Santa Monica golf course in the area where Culver and then McCune had offered potential temple sites. David Howells, however, suggested the possibility of locating the temple on the property south of the Wilshire Ward chapel because it was close to public transportation, while the poorer Saints could not reach Temple Hill.[9] President Grant, however, wanted a site large enough so the building and its grounds would compare favorably with the Church’s other temples.

The First Presidency (J. Reuben Clark Jr., President Heber J. Grant, David O. McKay) at the time the temple site was purchased. (© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Courtesy of John Livingstone)

The First Presidency (J. Reuben Clark Jr., President Heber J. Grant, David O. McKay) at the time the temple site was purchased. (© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Courtesy of John Livingstone)

In early 1937, the President returned to Los Angeles to continue the search. He expected to be there only a week to ten days but spent an entire month. Eventually, he and David Howells were most impressed with property in West Los Angeles owned by silent screen star and comedian Harold Lloyd and his Motion Picture Company. Still they failed to secure the desired site. A day after returning to Salt Lake City, however, he received a telegram from David Howells reporting success in finally obtaining it.

The Site Secured

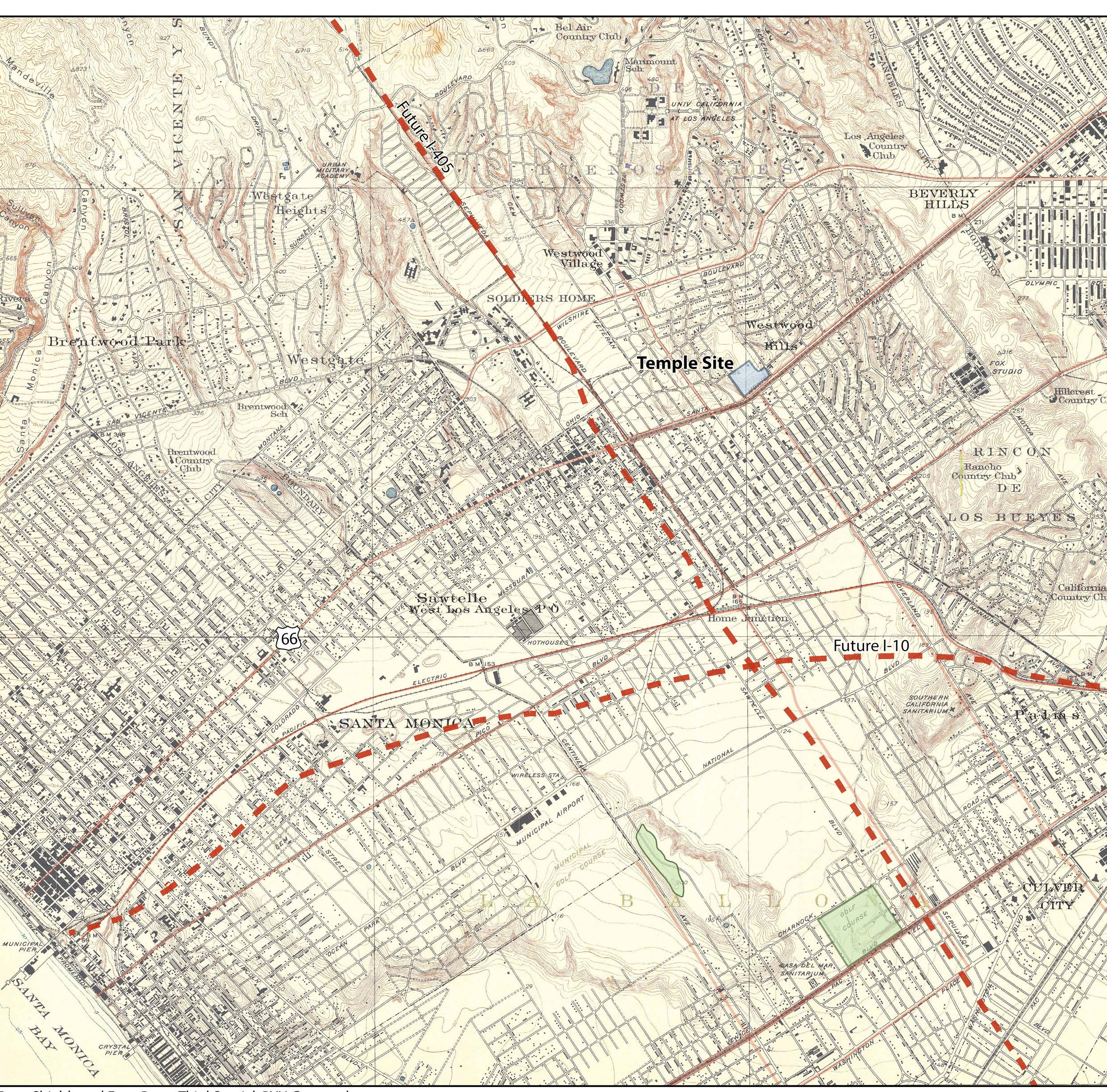

On February 17, 1937, President Grant announced to the First Presidency and the Twelve his intention to purchase the Lloyd property. Two days later, David Howells made a down payment of $5,000 on the chosen twenty-four-acre tract. Then on March 6, the Church publicly announced the purchase of the site in “the exclusive Westwood District of Los Angeles” for $175,000 (nearly $2.9 million in the twenty-first century). It fronted on heavily traveled Santa Monica Boulevard, which was a part of the famed Route 66. The plan was to erect a temple costing about $350,000.[10] President Grant enthusiastically told President J. Reuben Clark that “we have the best site in the entire country.” He personally planned to contribute at least $2,500. He anticipated that “the building will be of such a nature as to make of that spot, a tourist center in Los Angeles.”[11]

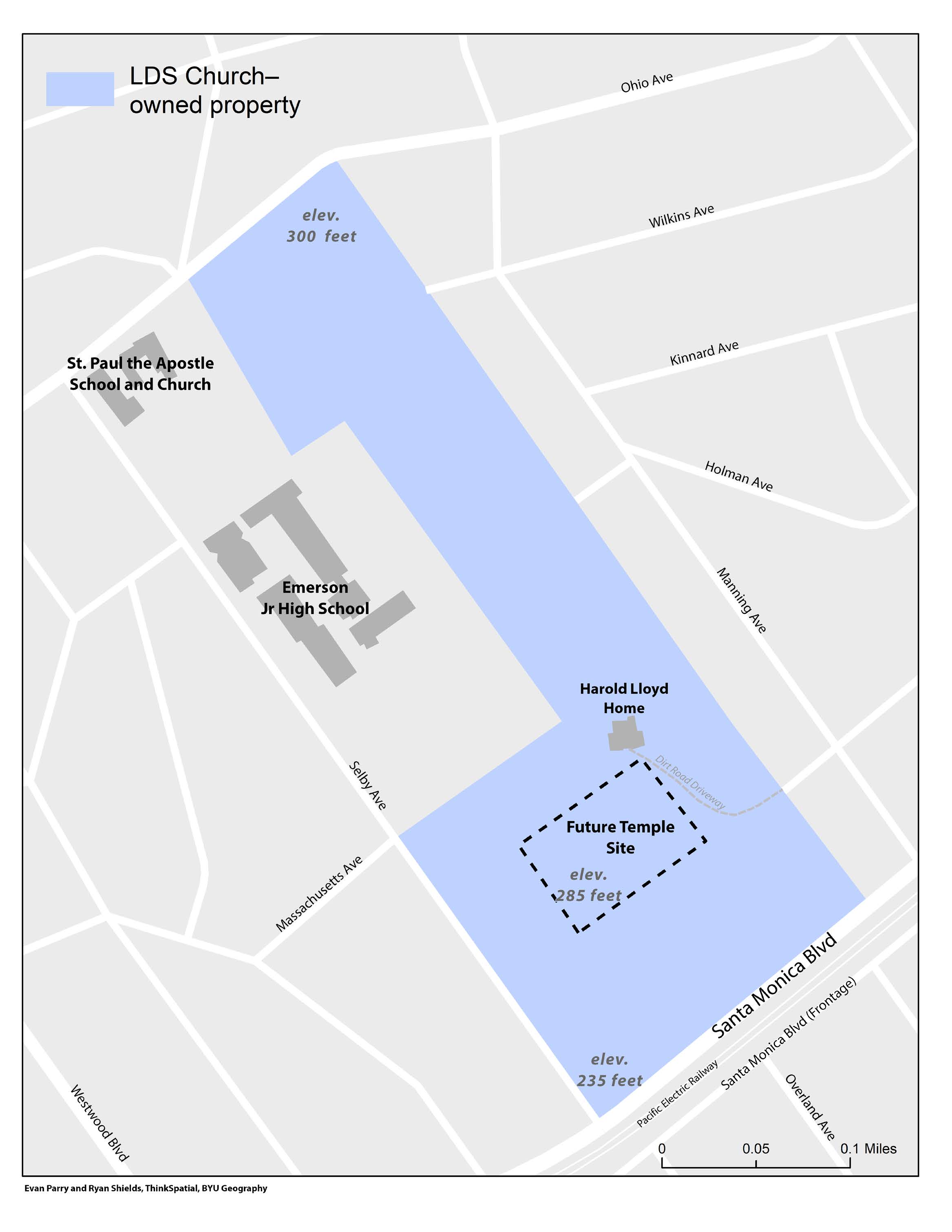

The site had a frontage of 775 feet on Santa Monica Boulevard, meaning that the temple would be easily visible from that important thoroughfare. The plot was 690 feet wide in the area where the temple would be situated, and it measured 2,080 feet long. It was bounded on the west by Selby Avenue for 724 feet and then by a middle school and Catholic church. On the east, it was bounded by a row of apartment houses. On the north, it opened to Ohio Ave., and on the south to Santa Monica Boulevard. Its lowest point, at the corner of Santa Monica and Selby, was 235 feet above sea level. The property then ascended a knoll to an elevation of 285 feet, where the temple would be built, and reached a maximum elevation of 300 feet at its north end.[12]

The title to the temple site can be traced back to the era of exploration. In 1542, when Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo became the first European to sail up the California coast, this area was claimed for King Charles I of Spain “by right of discovery and settlement.”[13] Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821 and assumed jurisdiction of California. In 1843 the Mexican government issued a series of land grants, creating vast ranchos throughout California. On February 24 of that year, Maximo Alanis, one of the soldiers who had accompanied the group that founded the pueblo of Los Angeles in 1781, received title to Rancho San Jose de Buenos Aires. It covered about one square league, or about seven square miles, from present-day Sepulveda Boulevard to Beverly Hills and included what is now Westwood, the UCLA campus, and Bel Aire. Over the next century, the land changed hands about a dozen times. Harold Lloyd purchased a twenty-four-acre parcel of the original rancho property in 1923, and the deed transferring ownership to the Church was dated March 23, 1937.[14]

On the property was Harold Lloyd’s former home—a large brick-and-stucco structure with tile roof—which had also served as his company’s business offices. When the Church purchased the site, this building was being used as a UCLA fraternity house. Also located on the property was a movie set of a New York City street scene that had cost $60,000 to build and later $40,000 to renovate. The Church allowed the Lloyd company to keep the set on the site temporarily, and some movies were shot there after 1937.

Apparently the people in Southern California were excited to have their temple site at last. On February 19, 1937, even before the Church’s purchase was finalized, the five area stakes and California Mission began planning for a sunrise service on the tennis court slab of the Lloyd property for Easter morning, March 28, and choruses began rehearsing. The service would begin at 5:40 a.m., with the possibility that it would be broadcast by radio station KMTR. At the last minute, the location was shifted to the nearby south entrance to the UCLA campus because the temple property was still in escrow.[15] Laraine Johnson of Long Beach (later more widely known as the movie star Laraine Day) gave an inspired reading at this service.[16]

The Saints were eager to get the temple started immediately. Just a week before the Easter service, the First Presidency counseled: “In the past the Lord has sometimes delayed the beginning of the work of building a temple and has carried on its construction for years . . . that people might come to an adequate appreciation of the spiritually high purpose toward which their efforts were directed.” For example, He showed wisdom “in prolonging the experience and sacrifice of the people” in connection with building the Salt Lake Temple. The date when a temple is completed is less important than “the spirit with which the building is erected and the righteousness which it shall bring into the hearts of the people. . . . The building of a temple is a matter . . . to be carried on with the greatest dignity, [and] a spirit of reverence and even with sanctification.”[17] Nevertheless, enthusiasm for the temple project continued to be high.

Designing the Temple

Bishop David P. Howells, who had played a key role in acquiring the property, was named “chairman of the building committee in charge of construction.” Members of the committee would be the presidents of the nine stakes in California—five in the south as well as the four in the northern part of the state.[18] Unfortunately, Howells would pass away two years later at the age of only fifty-five, before temple construction could begin.

Just three days before the Church announced the purchase of the temple site in Los Angeles, it had announced plans to build a temple in Idaho Falls. The prevailing practice was to conduct a “competition” in which qualified architects would submit their designs for a proposed new building. The First Presidency departed from this custom, however, and assigned a “board of temple architects” to design the temples for Los Angeles and Idaho Falls. They expected that this group of architects with varying backgrounds and ideas could work together and produce a superior temple design than would not be as likely a single architect working alone. Arthur Price, architect in the Presiding Bishopric’s Office, headed the group. Members of the board were Hyrum C. Pope, John Fetzer, Georgius Y. Cannon, Ramm Hansen, Lorenzo S. Young, and Edward O. Anderson. They inspected the site in September 1937 and arranged to test the strength of the subsoil and to evaluate the earthquake potential. “We were very sincere in our work,” Anderson later reflected. “One of the first things we did when we visited the site was to gather in a group to offer prayer to the Lord for help in this great work.”[19]

(Michael Whiffen)

(Michael Whiffen)

Church leaders instructed the architects to plan for the temple in Los Angeles to accommodate companies of 200 and the temple in Idaho Falls to accommodate 150. Early in 1938 the board began preparing sketches for the two temples. While plans went forward for a two-story temple in Idaho, the architects were delayed as they considered the possible advantages of a one-story structure for the large Los Angeles site. They even received the suggestion that the Harold Lloyd home might be retained behind the temple and serve as a kind of annex for clerical and related functions. Eventually they were instructed to prepare a two-story plan also for Los Angeles, which would be more stately and dignified. Five proposals were submitted to Church leaders, three for Los Angeles and two for Idaho Falls, but with the possibility that any of the plans could be used at either site. Finally, “the design by Lorenzo S. Young and Ramm Hansen [for the Los Angeles Temple] was favored enough to be published.”[20] While preliminary plans were completed for the temple, the outbreak of World War II brought work to a halt.

In 1942 the US Government rented about one acre of the temple site for one year and enclosed it with a wire fence. The Army set up a highly sensitive listening device to detect the sound of enemy aircraft at a distance and a powerful searchlight to use in case of a possible air raid. A small wooden barracks was constructed to house the fifteen men who would operate this site.[21]

Still, Church leaders were committed to the temple project. In 1943, while the war was still raging, President Heber J. Grant affirmed that “we are prepared to go forward with the building of the Los Angeles Temple on the beautiful site we have there, just so soon as it is possible to do so in view of the priorities and other war-time conditions.”[22]

Notes

[1] Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1996), 264.

[2] Manuscript History of the California Mission, 29 October 1921, MS, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[3] Journal History of the Church, 7 August 1847.

[4] “Protest against Incorporation,” Los Angeles Times, May 9, 1916, 16.

[5] “Temple Site on Coast Tendered L.D.S. Church,” Deseret News, December 8, 1921, 2:1.

[6] B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1957), 6:493; see also Leo J. Muir, A Century of Mormon Activities in California (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1952), 1:465.

[7] Muir, Century of Mormon Activities, 2:198–99.

[8] Chad Orton, More Faith Than Fear: The Los Angeles Stake Story (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1987), 120.

[9] Heber J. Grant diary, May 3–4, 1936.

[10] “24-Acre Plot Bought from Film Star for New Edifice,” Deseret News, March 6, 1937, 1.

[11] Heber J. Grant to J. Reuben Clark, correspondence, March 6, 1937; see also February 22, 1937, Church History Library.

[12] “California Temple Site Not Far from Pacific Ocean,” Church News, February 2, 1949, 4.

[13] Robert Glass Cleland, From Wilderness to Empire: A History of California 1542–1900 (New York: Knopf, 1949), 9–14.

[14] Noel C. Stevenson, “Land Title History of the Los Angeles Temple,” Improvement Era, April 1951, 238–40; see also Joseph Lundstrom, “History of the Los Angeles Temple Site,” Church News, October 24, 1951, 4; for a complete list of the owners, see appendix B.

[15] “Sunrise Service,” The Ensign (a temporary replacement of the California Intermountain News), April 18, 1937, 1; “Sunrise Service Changed,” The Ensign, April 25, 1937, 1; “Service on Temple Lot,” Church News, April 20, 1937, 2.

[16] John M. Russon, “Recollections,” California Intermountain News, March 11, 1971, 12.

[17] First Presidency to David P. Howells, March 17, 1937, First Presidency Letterbooks, MS, Church Archives.

[18] “24-Acre Plot Bought from Film Star,” 1.

[19] Edward O. Anderson, “The Los Angeles Temple,” Improvement Era, April 1953, 225.

[20] Paul L. Anderson, “Mormon Moderne: Latter-day Saint Architecture, 1925–1945,” Journal of Mormon History 9 (1982): 82.

[21] Preston D. Richards Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo Utah, box 4, folder 3.

[22] “Message of President Grant,” Church News, April 17, 1943, 4.