Postwar Revival of Temple Planning

Richard O. Cowan, "Postwar Revival of Temple Planning" in A Beacon on A Hill: The Los Angeles Temple (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 27–52.

1947 Leaders visit site and apply for building permit (November)

1949 Plan to build temple is announced at meeting of California leaders (January 17)

Edward O. Anderson is named as sole temple architect (January)

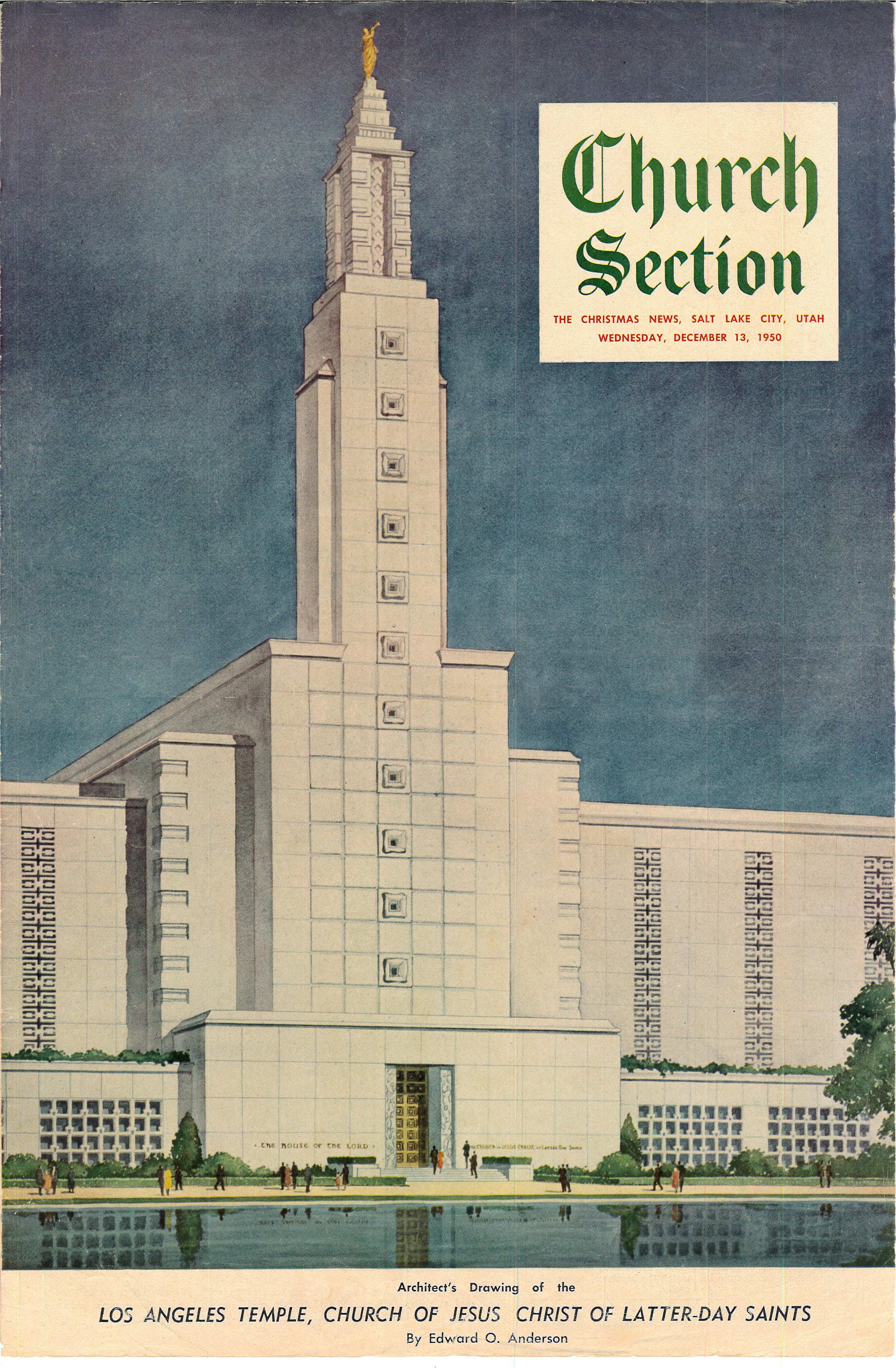

1950 Colored rendering of temple appears on Church News cover (December 13)

1951 Final approval is given by city (January 9)

Groundbreaking with small group of invited guests (September 22)

1952 Kick-off meeting for fund-raising campaign (February 3)

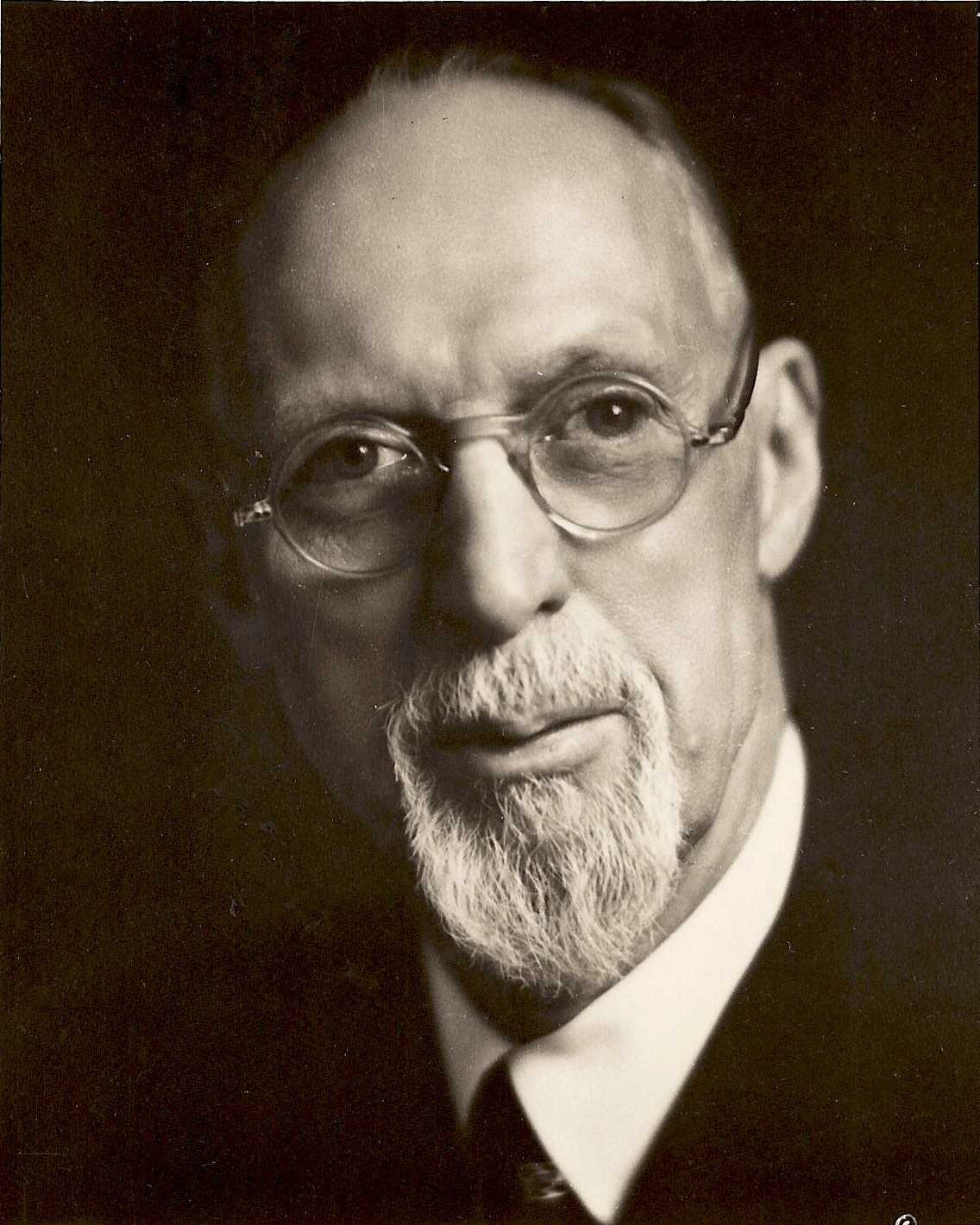

Within weeks of the end of World War II, Heber J. Grant died and George Albert Smith became the new President of the Church. Under his leadership, active planning for a temple in Los Angeles resumed. Ever since the site was purchased in 1937, faithful Latter-day Saints had visited the spot, eagerly looking forward to the time when the temple would be built there. World War II had halted the project for several years, and now concerns over zoning would add yet a further delay.

President George Albert Smith. (Courtesy of Intellectual

President George Albert Smith. (Courtesy of Intellectual

Reserve, Inc.)

Protecting the environment of the temple site was a major concern for Church officials. During the second weekend of November 1947, President George Albert Smith, his second counselor David O. McKay, and a number of local Church leaders visited the site. President Smith reported that the group “made a thorough inspection of the site” and determined that the Church owned ample property upon which to erect “a beautiful, commanding structure.” He explained that “we are thoroughly satisfied with the site, and if assurance can be had that zoning laws will protect the surrounding area, we will be ready to proceed with construction. . . . We’ve got the land, but we will not build until we are sure a warehouse or some similar project will not be erected next door,” he stressed. A decision was hoped for within a few weeks. Still, the Church formally applied to the Los Angeles Planning Commission “for permission to erect a $1,000,000 Temple on the [West Los Angeles] site.”[1]

At this time, the substantial growth in Southern California Latter-day Saints created another concern. When the temple site was purchased in 1937, there were only five stakes and approximately twenty-five thousand Latter-day Saints in Southern California. President Smith now observed that there were eight stakes and about seventy-five thousand Church members in the area and that the total was constantly increasing. Referring to the plans prepared by the board of temple architects a few years earlier, President Smith insisted that “the great increase in Church population in Southern California in recent years makes some changes necessary.” The increased size of the temple was reflected in the greater projected cost when compared with prewar estimates. Specifically, the possibility of adding a large priesthood assembly room was being considered—the first since the Salt Lake Temple.[2]

The Long-Awaited Announcement

About a year later, on December 27, 1948, the First Presidency wrote the eight stake presidents in Southern California informing them that “it would seem we have come to the point where we may with wisdom go forward with this long desired and anticipated construction of a House of the Lord.” The Presidency explained that “building the temple has been delayed because of problems related to World War II and the need to forestall if possible the establishment of industrial and business operations in the area surrounding the temple which would be undesirable.” The letter also recommended that the stake presidents meet soon to discuss fund-raising.[3]

The Wilshire Ward chapel.

The Wilshire Ward chapel.

The First Presidency then called a historic meeting for Monday evening, January 17, 1949, at the beautiful Los Angeles Stake Center or Wilshire Ward chapel. Invited to attend were stake presidencies and bishoprics from the temple area as well as officials from the California Mission. President Smith announced that the time was right to build the temple in Los Angeles in fulfillment of Brigham Young’s 1847 prophecy that “in the process of time the shores of the Pacific may yet be overlooked from the temple of the Lord.” He also explained that the new temple would be “substantially larger than the one envisioned in the pre-war plans. Instead of seating 200 in each ordinance room, the capacity would be 300—the same as the Salt Lake Temple. Furthermore, it was to add the large upper assembly room—one of only two temples during the twentieth century to include this facility (the Washington D.C. Temple being the other). When the President asked the group if they would approve plans to build the temple, the sustaining vote was unanimous. Conferring with Los Angeles civic leaders during this same trip, President Smith expressed his desire that the temple should be a “contribution to the architecture and culture of the community.”[4]

President David O. McKay, who had accompanied President Smith to Los Angeles, reported that Southern California Church leaders were enthusiastic about the new temple. “They are eager to go ahead with the construction and are pleased that the new temple is to be the second largest in the Church.”[5] It actually would become the largest temple the Church had ever built (and would retain that position until new facilities added to the Salt Lake Temple during the 1960s would once again make it the largest).

Soon after the January 17 meeting, area leaders sent a letter to Church members in Southern California outlining the advantages of having a temple in Los Angeles and the blessings from contributing to its construction. The leaders were convinced that over a decade earlier President Heber J. Grant was inspired in selecting the Santa Monica Boulevard site: “It is the highest point in elevation between Los Angeles and the ocean.” Furthermore, two major freeways, planned after the site was purchased, would intersect nearby and thus provide excellent accessibility. Additionally, the temple would add an important new dimension to the cultural life of the educational community in which it was to be located. The letter affirmed that the words of Brigham Young about the Salt Lake Temple might also be applied to the temple in Los Angeles: “It shall be a monument to the city and an acknowledgment of our faith and devotion to God.”[6]

It was anticipated that groundbreaking and fund-raising could happen right away; however, the necessity of new enlarged plans and overcoming legal obstacles delayed matters for two years.

Designing a Larger Temple

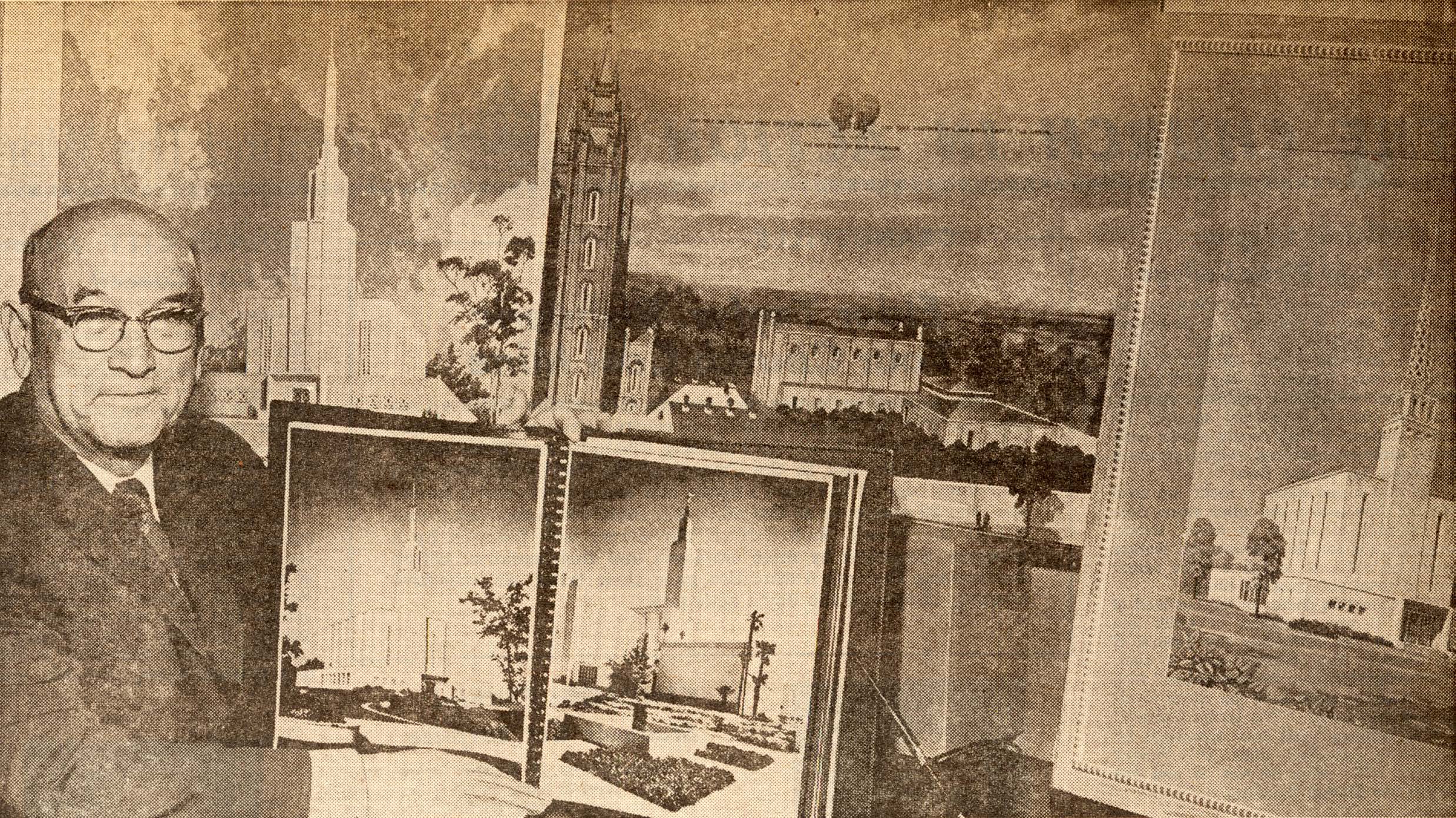

In January 1949, the same month as the meeting with Southern California leaders, the First Presidency appointed Edward O. Anderson, who had been a member of the prewar board of temple architects, to be the sole architect for the new temple. He had received his architectural training at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The Presidency instructed him to enlarge the design to accommodate growing Church membership in Southern California and to add the upper assembly room. This would involve thoroughly reworking the plans prepared over a decade earlier. Specifically, Anderson “borrow[ed] rather freely” from the design that had been prepared by Lorenzo S. Young and Ramm Hansen.[7]

Edward O. Anderson. (Church News, May 14, 1966, p. 3)

Edward O. Anderson. (Church News, May 14, 1966, p. 3)

Anderson prayed for the same inspiration that had guided earlier temple architects so that his design “might express in appearance” and facilitate “the spiritual work” to be carried on in the temple. He and his associates worked closely with the First Presidency, from whom they received constant inspiration and direction. He later testified that whenever a problem arose in designing the building, “the answers or individuals we needed were forthcoming.”[8]

After the architects had been at work for nearly two more years, the General Authorities in the closing weeks of 1950 approved the “essential design” for the Los Angeles Temple. On December 13, the cover of the weekly Church News featured a rendering in color. Southern California Latter-day Saints were thrilled to see this visual representation of their long-anticipated temple.

The Church News article described the temple design as having a Mayan character. The architect himself spoke of another dimension: “Although it would be difficult to detect architectural influence of the South Pacific in the design for the temple, I am sure that if one looked closely enough, the honest face of the Polynesians could be found in the solid walls.” Anderson confided that while he was planning the temple, his heart “was divided between two great loves, the love of the temple work and the love of the work in the South Pacific.”[9]

The temple proper would be three stories high and 301 feet long. There would be a fourth floor in the center of the building. A single-story annex in the form of a block U would enclose a 42-by-119-foot reflecting pool in front of the temple. The building would be 364 feet across by 241 feet deep, including the annex. It would be surmounted by a tower 257 feet 8½ inches high. Only one other building in Los Angeles was taller, the Los Angeles City Hall. The building’s six levels would include ninety rooms and cover 190,000 square feet or about four and a half acres of floor space—making this the largest temple the Church had built to that point. When completed, the temple was visible to ships twenty-five miles out to sea.

The design called for monolithic concrete walls with a cast-stone exterior, similar to the recently dedicated Idaho Falls Temple. The single tall tower was a striking feature of the design. It would be the tallest temple tower in the Church, exceeding the Salt Lake Temple’s east center tower by 47 feet. Only the Washington D.C. Temple’s main towers, built during the 1970s, would be taller. Another unique feature of the design included plantings in roof boxes on the annex around the large reflecting pool and in the building’s interior.[10]

According to the plans, the main entrance was in the center of the annex, on the southeast or Santa Monica Boulevard side of the temple. To the left were administrative offices and a large chapel seating 380 persons in the southwest corner. To the right from the entrance were linen and sewing rooms (later a smaller chapel), and in the southeast corner a dining room that could accommodate 300 persons. Dressing rooms were located on this same floor at the rear in the temple proper. The second floor had rooms for the sacred temple ordinances or ceremonies. These included the oval creation room, garden room, world room, terrestrial room, and celestial room, some with murals on their walls. A large priesthood assembly room, similar to that in the Salt Lake Temple, occupied most of the third floor. It measured 257 feet by 76 feet and had a ceiling 34 feet high. It would accommodate twenty-six hundred persons. The smaller fourth floor had study rooms and other facilities for temple workers. The baptismal font, resting on the backs of twelve oxen, was below ground level in the center of the temple.[11]

With the basic design approved, the next step was to prepare working plans and other specifications. This was to be done as quickly as possible so construction could begin. Still, over a year would be needed `to accomplish this step. The architect consulted with twenty-eight engineers and expert craftsmen in various fields in order to move from general design to detailed structural plans. “As much time was required to build the structure on paper as we needed to build it with concrete and stone,” he later observed.[12]

A particular concern was to design the temple to withstand the earthquakes for which California is known. Therefore Anderson early on consulted with structural engineer George S. Nelson, who pointed out that the quakes’ lateral thrusts might be compared to pulling the rug out from under a person. Therefore the temple’s footings were “designed to move with the earth’s crust, while the inertia of the superstructure resists such motion.” Hence “the whole building should react much like a cup of Jello that has been suddenly jarred.” The structure was “designed to be sufficiently elastic to absorb a powerful shock with a minimum chance of cracking.” The twenty-four-thousand-ton temple was structured in such a way that it would only “quiver on its foundation.” While from its exterior the temple would appear to be built of “massive stones eight feet wide, seven feet high, and of substantial thickness,” actually this would be just “a thin veneer” covering carefully engineered concrete walls with reinforcing steel.[13]

President David O. McKay. (© Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

President David O. McKay. (© Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

“To be assured that the temple was properly designed in every detail,” Anderson had his staff produce “an exact model” at the scale of 1/

During this planning process, hundreds of sketches had been made. The next step was to distill the approved sketches into the final plans. A corps of draftsmen was enlisted to draw them on ninety large linen sheets. Sixty-three of these pages depicted floor plans, elevations, and enlarged illustrations of details. The remaining pages were mechanical drawings of heating, ventilation, plumbing, and electrical facilities. From these cloth masters, fifty sets of blueprints would be made to guide the temple’s builders.

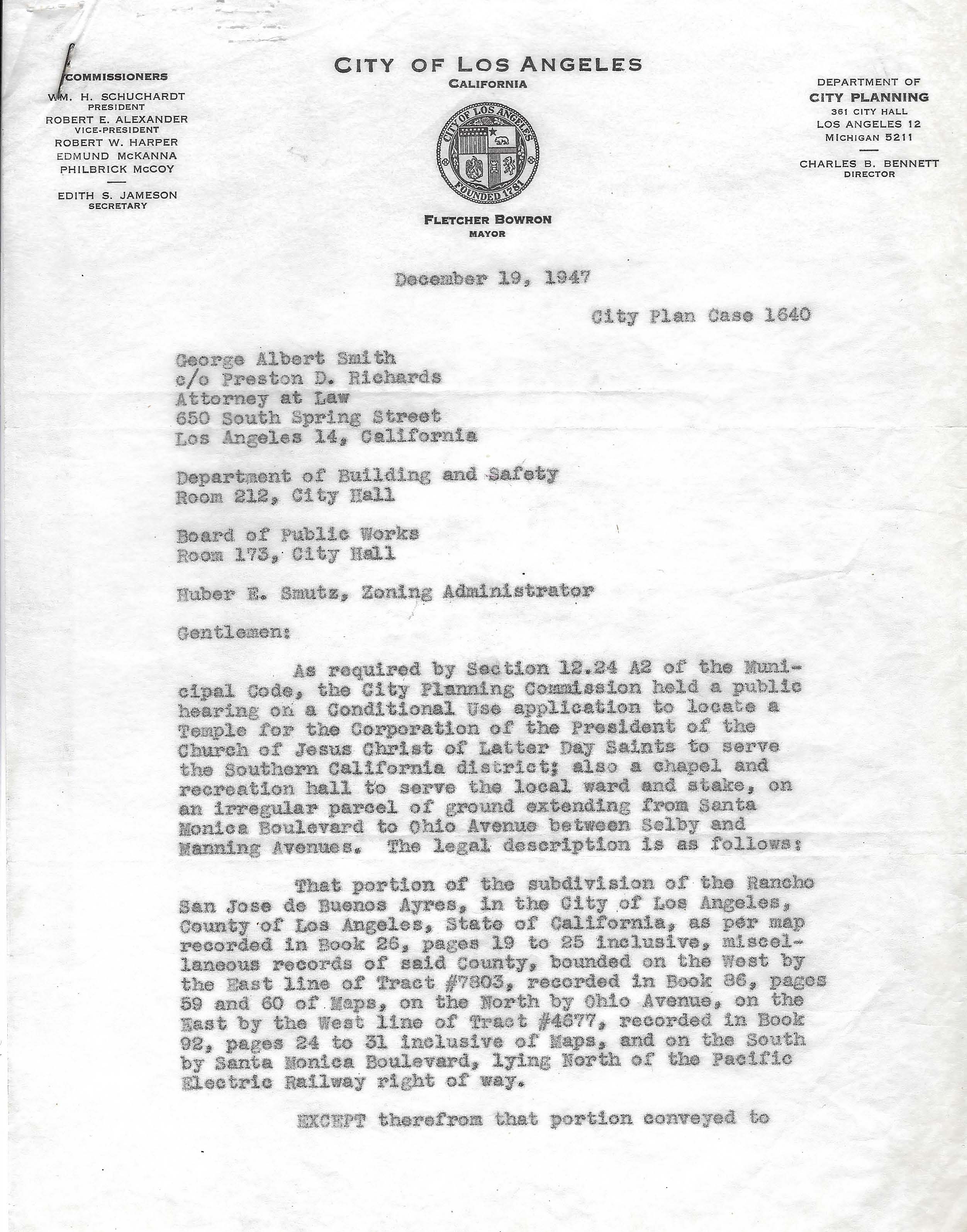

Governmental Approvals Secured

During the time architectural planning was going forward, Preston D. Richards, a Los Angeles attorney, worked pro bono in securing city approvals needed for the temple. Richards was a former member of the Los Angeles Stake presidency and had earlier been a law partner of J. Reuben Clark Jr. (a counselor in the Church’s First Presidency, who also had a noted diplomatic career) and of Apostle Albert E. Bowen; Richards set up branch offices of the firm in New York and Los Angeles. For four years Richards had served as assistant solicitor of the State Department during the administration of President William Howard Taft. While in Washington, Richards drafted at least one amendment to the US Constitution and also authored the proclamation of Arizona’s statehood. He was a noted constitutional scholar and wrote several articles on that subject. He also served the Church as a member of the Young Men’s Mutual Improvement Association general board.[15]

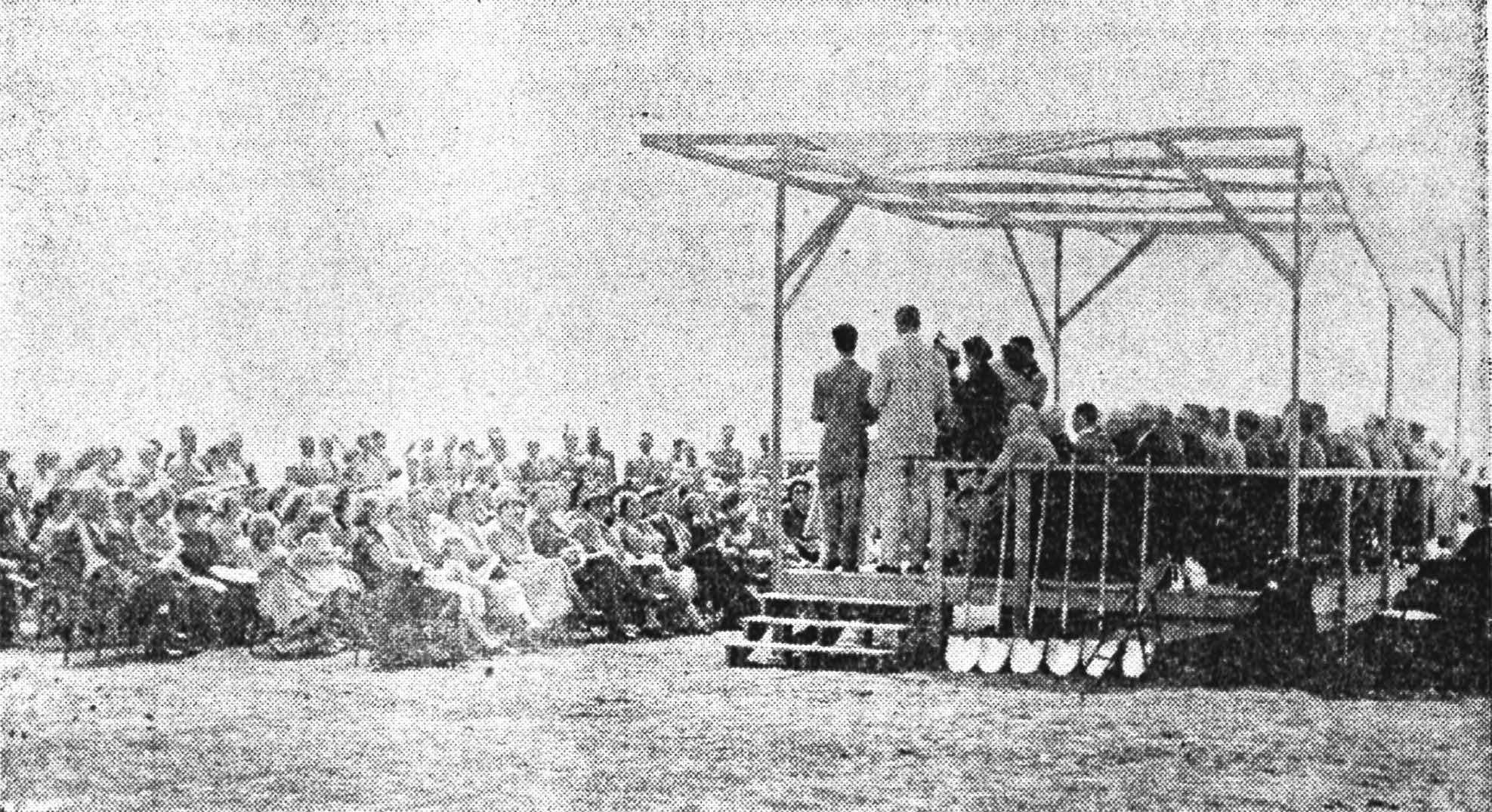

Speakers’ platform for the groundbreaking. (Howard Winn, Church History Library [CHL])

Speakers’ platform for the groundbreaking. (Howard Winn, Church History Library [CHL])

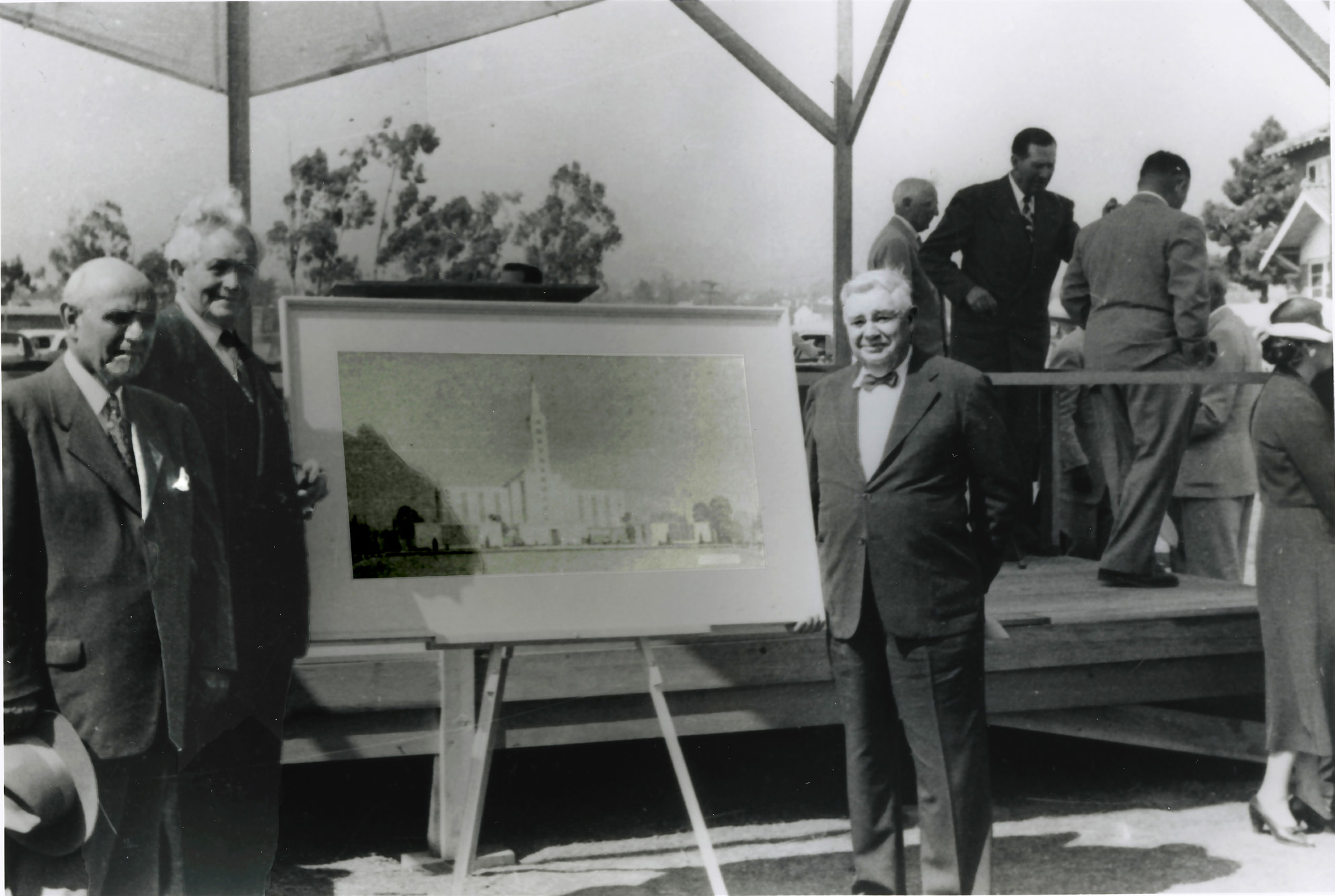

The First Presidency with an architect’s rendering of the temple.

The First Presidency with an architect’s rendering of the temple.

Over a period of more than two years, Richards contacted multiple departments of city government, including the Planning Commission, Engineer’s Office, and Department of Planning and Safety. All their regulations had to be met in order to obtain the needed permits. A zoning regulation was sought to prevent any undesirable businesses or industries from locating too close to the temple.

The final permit was approved by the city council on Tuesday, January 9, 1951, and signed that afternoon by Mayor Fletcher Bowron. As he witnessed the mayor signing the document, Richards acknowledged: “Full cooperation was given us by every branch of the city administration, and every department has now been satisfied. . . . The legal work is finished,” he gratefully declared.[16]

Reflecting back on this long process, a member of the Church Building Committee quipped, “I thought I knew what red tape was until I ran into the Los Angeles building restrictions and requirements.”[17] On the other hand, architect Anderson had a very positive experience as he explained the purposes of the temple to the Los Angeles Building Department. “When these men realized the importance of the temple and reviewed the record of Latter-day Saints living in California, they said they would be glad to have a Latter-day Saint temple in Los Angeles and help in every way to obtain the necessary permits.”[18]

By the time city permits were received, the United States was involved in the Korean War. Governmental restrictions on the purchase of structural steel “threatened to delay construction indefinitely.” The Church sent Preston D. Richards and architect Edward O. Anderson to meet with officials of the National Production Authority in Washington, D.C. Senator Arthur V. Watkins of Utah accompanied them to this meeting. “Although construction had not begun on the temple itself, Richards and Anderson argued that it was actually an integral part of a complex of buildings” that included the bureau of information, mission home, and ward chapel; “and since construction was already in progress on the other buildings, the temple should be considered part of an ongoing construction program. Whether because of the merits of the case or Watkins’ presence, the NPA official was sympathetic to their request.” He ruled that “this project had been started in January 1951 before restrictions were placed on churches; therefore the project could continue with other buildings such as the Temple, Bureau of Information, Boiler Room, Mission Home, and other improvements on the project.”

Later that day Richards and Anderson related their success to a local Church member who was an architect for the Federal Government. He was amazed and couldn’t imagine that “we had received word so soon, as the Supervising Architect of the Government was required to wait many weeks for a decision on the Government buildings.”[19]

Meanwhile, Church President George Albert Smith died on his eighty-first birthday, April 1, 1951, and his successor, David O. McKay, was sustained a few days later at a special “solemn assembly” during the Church’s annual general conference. President McKay recognized the indelible influence Church buildings, particularly temples, had in areas such as California where there was often turmoil and the Latter-day Saints were a small, sometimes unknown minority. With the new First Presidency in place and the matter of purchasing structural steel resolved, groundbreaking for the new temple could proceed.

Groundbreaking

The long-anticipated event took place on Saturday, September 22, 1951. President John M. Russon of the Los Angeles Stake “was in charge of local arrangements, assisted by Presidents W. Noble Waite of the South Los Angeles Stake and Howard W. Hunter of the Pasadena Stake. A speakers’ platform with a canopy was set up for the occasion. On an easel by the stand was a large color rendering of the future temple.”[20] A group of deacons and young girls of corresponding ages came to the site early to fulfill their once-in-a-lifetime assignment to pick up trash and help get things ready.

Heading toward the

Heading toward the

groundbreaking site.

The delegation from Church headquarters included the entire First Presidency; Joseph Fielding Smith, President of the Quorum of the Twelve; Eldred G. Smith, Patriarch to the Church; two members of the First Council of the Seventy; Presiding Bishop LeGrand Richards and his counselors; Preston D. Richards, attorney; Chairman Howard J. McKean and three members of the Church Building Committee; Edward O. Anderson, temple architect; and representatives of the Genealogical Society and Church Purchasing Department. Also invited were Southern California stake presidencies, presidents of the two missions in California, and their wives. Representatives of the press were also invited. Civic dignitaries present included Mayors Fletcher Bowron of Los Angeles and C. Dean Olson of Beverly Hills (who also was bishop of the Beverly Hills Ward). Because there were no facilities to accommodate the huge crowd that would likely attend, this significant event was not publicized and took place in the presence of only these 250 invited guests.

The first soil is turned.

The first soil is turned.

President David O. McKay with counselors J. Reuben Clark Jr. and Stephen L Richards.

President David O. McKay with counselors J. Reuben Clark Jr. and Stephen L Richards.

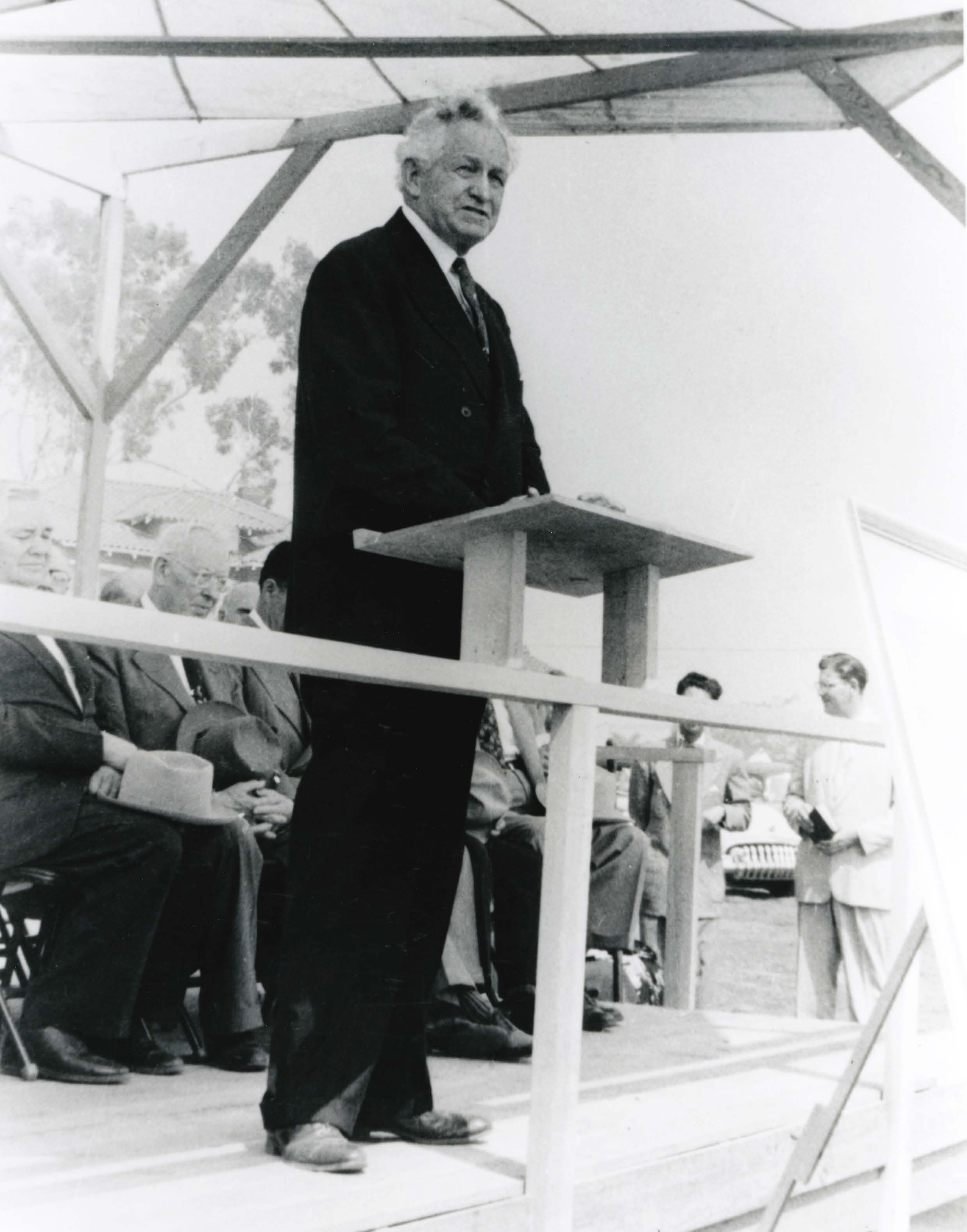

The program got under way at 1:00 p.m. The sun was shining, and a gentle sea breeze was blowing.President McKay greeted the group and reviewed the events leading up to the auspicious occasion. He introduced Preston D. Richards, who would offer the invocation, indicating that he had “been most devoted to the cause and has attended to a thousand and one details pertaining to the erection of this building.” Mayor Bowron declared that “the groundbreaking was a significant moment in the history of Los Angeles.” He affirmed that “the temple would be an asset to the city, appreciated by its residents, but the beauty of the structure is a small thing in comparison with the moral and spiritual values it will bring.”

The first General Authority speaker was LeGrand Richards, Presiding Bishop of the Church and former president of the Hollywood Stake; he declared that the groundbreaking would be “one of the most important events in the history of the world.”[21] President Joseph Fielding Smith praised the privilege of making ordinances available vicariously to those who died without hearing the gospel of Christ. President J. Reuben Clark Jr. asserted that the Saints would be blessed by the temple “in proportion to the sacrifice” they made toward its erection; he insisted that they then would be responsible to enter worthily so that they might come into the presence of God (see D&C 97:15–17). President Stephen L Richards anticipated that the temple would attract widespread admiration and that explaining its true purpose to exalt mankind would present a significant missionary opportunity.[22]

The group then moved to the southeast corner of the future temple’s footprint, where President David O. McKay turned the first spade of earth and announced, “I now declare the first shovel of dirt raised over the site of the Los Angeles Temple which is to be reared to the glory of God and to the salvation of His people.” As other leaders took their turns, the earth proved to be too hard; President McKay had to “soften it up” for them with his shovel, much to the delight of those present.

After the groundbreaking, the group returned to the speakers’ stand. President McKay then officially dedicated the temple site. He expressed gratitude that all, both living and dead, might obtain salvation “by obedience to the laws and ordinances of the Gospel” and that temples may “serve as a means of communication between loved ones, here and hereafter.” He specifically petitioned a blessing for those who would build the temple: “bless them with wisdom, with singleness of purpose, and with skill even above their natural or acquired ability.”[23]

Those present described experiencing “a feeling of happiness and spiritual uplift” during the program. The group then went to the partially completed Beverly Hills Ward chapel nearby, where they enjoyed a delicious luncheon prepared and served under the direction of the ward Relief Society president, Zatelle Sessions.[24]

The press gave favorable coverage to the groundbreaking. For example, the Los Angeles Times proclaimed, “The greatest temple ever built by the Mormon Church was officially begun yesterday.” The article appeared on the front page of the paper’s local section and provided a good description of what had taken place, including quotations from Mayor Bowron and the Church leaders who spoke during the program.[25]

Fund-Raising

Two weeks after the groundbreaking, during October general conference, stake presidents in the temple district met in Salt Lake City with President Stephen L Richards, First Counselor to President McKay, to receive their assignments for fund-raising. They were told that of the building’s estimated $4 million cost (equivalent to over $28 million in the early twenty-first century), $1 million would be their “fair share.” President Noble Waite of the South Los Angeles Stake and chairman of the fund-raising committee later commented that President Richards did not know how he nearly “knocked out fourteen stake presidents with that statement,” as this would average more than $70,000 per stake. “We kept our chins up,” Waite continued, “and it was only afterwards when we got out, and we confided in each other that really we were staggered. But we had received the commission, and so our instructions before we left were to make a plan, organize, and submit the plan, and get the approval of the First Presidency and then we would be given the green light to go forward.”

President David O. McKay (center) and Elder Alma Sonne (Assistant to the Twelve, to his right) join mission and stake leaders around a large replica of the proposed Los Angeles Temple. (Church News, February 6, 1952, 2)

President David O. McKay (center) and Elder Alma Sonne (Assistant to the Twelve, to his right) join mission and stake leaders around a large replica of the proposed Los Angeles Temple. (Church News, February 6, 1952, 2)

President Richards directed that the responsibility for raising the funds be shared equitably among the stakes and California Mission according to population. The First Presidency wanted no individual assessments. Each person should give what he or she was able. Still President Richards recommended that a guide be prepared suggesting how much those in different income brackets might contribute. Upon returning to California, the stake presidents worked out a plan that the First Presidency approved with only a few modifications.[26]

Another historic meeting convened on Sunday afternoon, February 3, 1952. At the large South Los Angeles Stake Center in Huntington Park, President David O. McKay met with stake presidencies, high councils, and bishoprics from throughout the temple district, as well as representatives from the California Mission, and their wives, to officially kick off the fund-raising campaign. He told the twelve hundred stake and ward leaders that the Church was about to begin construction on the “largest temple ever built in this dispensation,” unveiling the large model of the edifice. He challenged the leaders to raise their million-dollar share in three years. He counseled the leaders to let the “young people, even the children in the ‘cradle roll’ [Sunday School nursery], contribute to the temple fund, for this is their temple, where they will be led by pure love to take their marriage vows.”[27]

South Los Angeles Stake Center in Huntington Park.

South Los Angeles Stake Center in Huntington Park.

Each of the stake presidents was invited to respond. President Wallace W. Johnson noted that the San Diego Stake had already established a successful program of fund-raising dinners, so he quipped, “We are eating our way into heaven.” Even though the East Los Angeles Stake was in the midst of raising funds for its own new stake center, President Faun Hunsaker was confident that this effort would not suffer because of the great temple campaign. “The Lord has blessed and will bless again,” he affirmed. President Edwin S. Dibble of the Glendale Stake acknowledged that “building a temple will be easier for us than for the pioneer Saints. Materials are near and in good supply, and the people are relatively prosperous.” President Vern R. Peel of the San Bernardino Stake was convinced that the Lord had a million blessings for the people as they raised the million dollars. “No sacrifice goes unrewarded.”[28] President Noble Waite of the South Los Angeles Stake, who was conducting the session, urged the leaders to adopt the slogan “Over the top with a full subscription by April Conference.”[29]

President Waite was convinced that the fund-raising would “have fallen flat if it had not been for the soul-inspiring discourse of President McKay. He electrified those 1200 people, and they went out of that meeting with a determination in their hearts that they were going to consummate that commission that was given by the First Presidency.”[30]

While President McKay was in California, he learned of Preston D. Richards’s death on January 31. Reflecting on his contributions, the president concluded, “No one has done more toward the securing of the site, meeting with the city and building commission and preparing papers related to the proposed Los Angeles Temple, than had Preston D. Richards.”[31]

Each stake president was to set the example by first making his own contribution. He would next invite stake and ward leaders to do the same. They could then go to the members and invite them to follow their examples and donate to the temple fund. A pledge card was created, and each individual was asked to determine for himself the size of his temple contribution according to his own circumstances.[32]

Only a few years earlier, the Southern California Saints had been asked to raise funds to purchase a ranch at Perris, eighty miles southeast of Los Angeles, for use as a Church welfare farm. President John M. Russon of the Los Angeles Stake reflected: “This was the Lord’s way of preparing the hearts of the people of Southern California to respond to the request to help build the kingdom. I believe that that was the seed that enabled us to have fertile ground in the hearts of the people to gain their sustaining vote and have the overwhelming success that we did when it came to raising the funds for the temple.”[33] Howard W. Hunter, president of the Pasadena Stake, concurred: “We had been working hard on fund raising for the welfare project and for the construction of stake and ward buildings throughout the area. The growth had been large and the costs were great; nevertheless we pledged our best efforts in carrying out the wishes of the First Presidency.”[34] President Hunter met with his leaders and introduced the fund-raising effort to them, “Go out into the wards and sell this program, and give the people the opportunity of receiving great blessings by contributing generously to the temple.”[35]

Front and back cover

Front and back cover

of the fund-raising brochure.

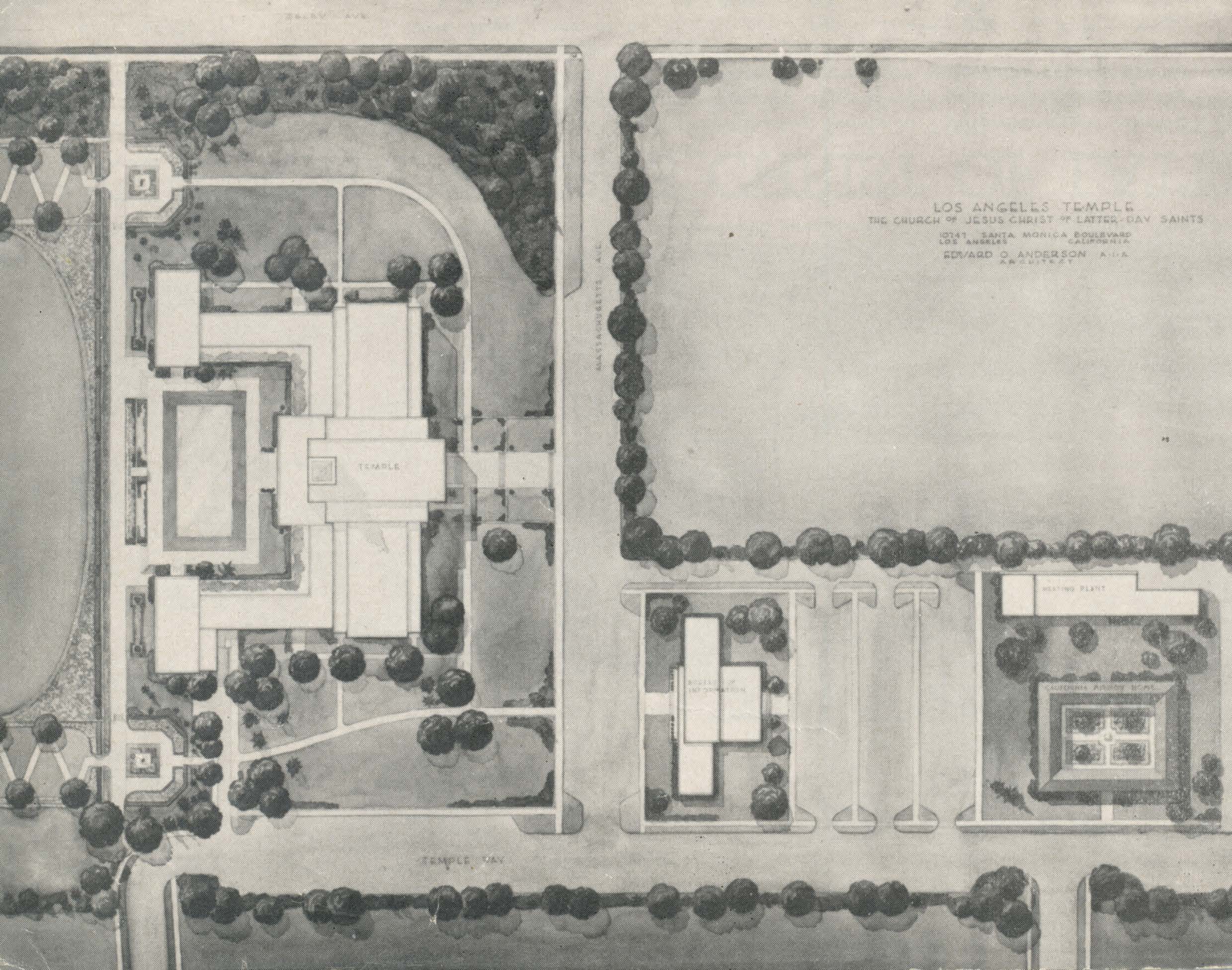

As a means of publicizing the fund-raising campaign, the Southern California Stake Presidents Temple Committee commissioned a brochure. Its outside covers featured front and back views of the temple. Inside, there was a plot plan and a number of construction photos. The brochure contained a fairly complete description of the temple and concluded, “To those who look upon the property from its richly landscaped gardens, to the gleaming Mo-sai walls, to the graceful tower with the Angel Moroni on top, the temple will reveal that here is an edifice sacred and holy in purpose, beautiful and pleasing in appearance—truly, a House of the Lord.”[36]

Because the temple would be located within the boundaries of the Los Angeles Stake, President Russon hoped his stake would be the first to report its pledge. The stake’s assigned share was $70,000. About a week after the February 3 kick-off meeting, each family received the souvenir brochure about the temple together with a pledge card. They were to prayerfully consider what their contribution would be, indicate it on the card, and seal it in an envelope. Sunday, February 17, was the day designated for the stake to collect these pledges. Between 2:00 and 4:00 p.m., a member of the bishopric, priesthood leader, or some other ward officer visited each home to answer any questions and to pick up the envelopes. Each bishop totaled the pledges and reported them to President Russon. He was thrilled to learn that stake members had pledged a total of $163,450, and he telegraphed this figure to President McKay that evening. The following morning President Russon received a telegram from the First Presidency: “Congratulations to Los Angeles Stake membership on being first in Los Angeles Temple District to complete canvas for temple subscription amounting to 238% of quota. Commendation and blessings.” An additional $18,000 of pledges came in during the next few weeks.[37]

Faithful Saints throughout Southern California sacrificed in a variety of ways to contribute to the temple fund. Families postponed or canceled plans for vacations or home improvements. Others decided to drive the old car a little longer. Teenagers went without new school clothes. Children emptied their piggy banks. When a twelve-year-old deacon in South Gate pledged $150, his bishop thought the boy had inadvertently put the decimal in the wrong place. However, the lad assured him it was no mistake. It took two years, but the young man paid the full amount from his paper route and lawn-cutting earnings.[38] An elderly widow, though in frail health and nearly blind, pledged $400. Over a period of two years she faithfully made payments from her meager resources in order to fulfill her pledge. She confided with her bishop, “I hope and pray the Lord will bless me and preserve my life until I can have the privilege of going through the Los Angeles Temple.”[39]

The plot plan in the brochure.

The plot plan in the brochure.

The Pasadena Stake sponsored another interesting project. Bishop J. Talmage Jones of the Los Flores Ward was treasurer of the Vernon Kilns. He arranged for this company to produce souvenir plates with a sketch of the temple drawn by Robert Perrine of the neighboring East Pasadena Ward. The plate’s border featured the design of the stone grill work that would cover the temple’s windows. Priced at $1.75, seven thousand of these plates were sold throughout Southern California that year, proceeds going to the temple building fund.[40]

At the April 1952 general conference, just six months after the stake presidents had received their fund-raising challenge, they once again met with the First Presidency. They reported that the faithful Saints had pledged to contribute over $1,648,600, more than half again what was requested. During this same period other Church donations did not suffer but actually increased.

Noble Weight, the stake president who had headed the temple committee, affirmed that building the temple had not been a sacrifice because “we have received rich blessings.” He noted that during the period of the temple’s construction tithe paying had increased 45–50 percent.[41] At the October 1952 general conference, he was invited to share this accomplishment with the whole Church: “We are enthusiastic. We are very happy and very proud, and we are very thankful that the First Presidency and the other General Authorities of the Church are building a temple in our area. I am sure it is going to do a great deal of good in Southern California. I vision a spiritual renaissance in that area. Our people will be spiritually uplifted. It will be a great blessing.”[42]

Front and back of a

Front and back of a

fund-raising plate.

By early 1955, South Los Angeles became the first stake to actually pay the amount pledged, $201,486.77. Stake president Waite affirmed: “We want every person who signed a pledge card to be given the opportunity of paying it in full. There are certain blessings which come to those who contribute to the House of the Lord that cannot be obtained in any other way. We want all our people to enjoy these blessings.”[43] By August of that year, the California Saints had paid over $1.3 million to the Church and promised they would complete the amount they had pledged before the temple was dedicated. They met that commitment. Stake presidents affirmed that this effort “has been faith-promoting and testimony-building, an experience that none who has participated [in] will ever forget. Peace and happiness have come to all as a result of having the opportunity to help build the house of the Lord.”[44]

View of Temple Hill from

View of Temple Hill from

across Santa Monica Boulevard. (George Bergstrom)

Meanwhile, by mid-1952 the fund-raising effort was progressing successfully. Working drawings and specifications had also been completed and approved. The time had finally come for actual construction to begin.

Notes

[1] “Los Angeles Temple Construction Now Awaits Favorable Zoning Decision,” Church News, November 15, 1947, 1.

[2] “Los Angeles Temple Construction,” 1.

[3] First Presidency to Southern California stake presidents, December 27, 1948, quoted in Chad Orton, More Faith Than Fear: The Los Angeles Stake Story (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1987), 179–80.

[4] Los Angeles Times, in Journal History of the Church, MS, Church Archives, January 17, 1949, 5; Deseret News in Journal History, January 18, 1949, 4; Improvement Era 52 (March 1949), 132.

[5] “News of the Church,” Church News, January 26, 1949, 4.

[6] Orton, More Faith Than Fear, 180.

[7] Paul L. Anderson, “Mormon Moderne: Latter-day Saint Architecture, 1925–1945,” Journal of Mormon History 9 (1982): 82.

[8] Joseph Lundstrom, “What It Takes to Build a Temple,” Church News, December 5, 1953, 9; see also Edward O. Anderson, “The Los Angeles Temple,” Improvement Era, November 1955, 803.

[9] Edward O. Anderson, “The Los Angeles Temple,” Improvement Era, April 1953, 226.

[10] “Design Approved,” Church News, December 13, 1950, 1–2.

[11] “Design Approved,” Church News, 2.

[12] “Los Angeles Temple,” Improvement Era, November 1955, 803; quoted in “Los Angeles Temple,” Ensign, May 1977, 120.

[13] George S. Nelson, “The Structural Design of the Los Angeles Temple,” Improvement Era, November 1953, 834–35.

[14] Joseph Lundstrom, “What It Takes to Build a Temple,” Church News, December 5, 1953, 8–9.

[15] “Late Preston D. Richards Plays Important Role in Early Legal Temple Work,” California Intermountain News, September 27, 1955, 6.

[16] “Architectural Splendor,” California Intermountain News, September 27, 1955, 5, 17.

[17] Orton, More Faith Than Fear, 181.

[18] Anderson, “Los Angeles Temple,” Improvement Era, April 1953, 226.

[19] Gregory A. Prince and Wm. Robert Wright, David O. McKay and Rise of Modern Mormonism (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2005), 257.

[20] “First Shovel of Earth Is Turned by President McKay at Temple Site,” California Intermountain News, September 27, 1955, 8–10.

[21] Orton, More Faith Than Fear, 181.

[22] “Groundbreaking Ceremony Launches Construction of Los Angeles Temple,” Church News, September 26, 1951, 2–3, 7–9; for a complete text of these remarks, see appendix C.

[23] “Dedicatory Prayer,” Church News, September 26, 1951, 2; California Intermountain News, September 27, 1955.

[24] “First Shovel of Earth,” 10.

[25] “Greatest Mormon Temple Begun Here,” Los Angeles Times, September 23, 1951, B1.

[26] William Noble Waite, in Conference Report, October 1952, 75.

[27] Quoted in Richard O. Cowan, Temples to Dot the Earth (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1989), 153.

[28] “All Stake Presidents Pledge Full Support of Membership,” California Intermountain News, September 1955, 12,13, 15.

[29] Henry A. Smith, “Pres. McKay Addresses Four Audiences in California,” Church News, February 6, 1951, 2.

[30] W. Noble Waite, in Conference Report, October 1952, 76.

[31] Smith, “Pres. McKay Addresses,” 2.

[32] Orton, More Faith Than Fear 182–23.

[33] Orton, More Faith Than Fear, 146.

[34] Eleanor Knowles, Howard W. Hunter (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1994), 126.

[35] Knowles, Hunter, 127.

[36] “L.A. Temple Described in Brochure,” Church News, July 4, 1953, 2.

[37] Orton, More Faith Than Fear, 183–84.

[38] California Intermountain News, September 27, 1955, 46.

[39] Orton, More Faith Than Fear, 185–86.

[40] “Souvenirs Aid Temple Fund,” Church News, April 16, 1952, 10; “Gift for President McKay,” Church News, October 10, 1953, 16.

[41] California Intermountain News, March 15, 1956, 1, 6.

[42] Waite, in Conference Report, October 1952, 77.

[43] “So. Los Angeles Fulfills Pledges,” California Intermountain News, September 27, 1955, 46.

[44] Edward O. Anderson, “The Los Angeles Temple,” Improvement Era, November 1955, 804.