Constructing the Temple

Richard O. Cowan, "Constructing the Temple" in A Beacon on A Hill: The Los Angeles Temple (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 53–118.

1951 Presiding Bishop LeGrand Richards breaks ground for ward chapel on site (January 13)

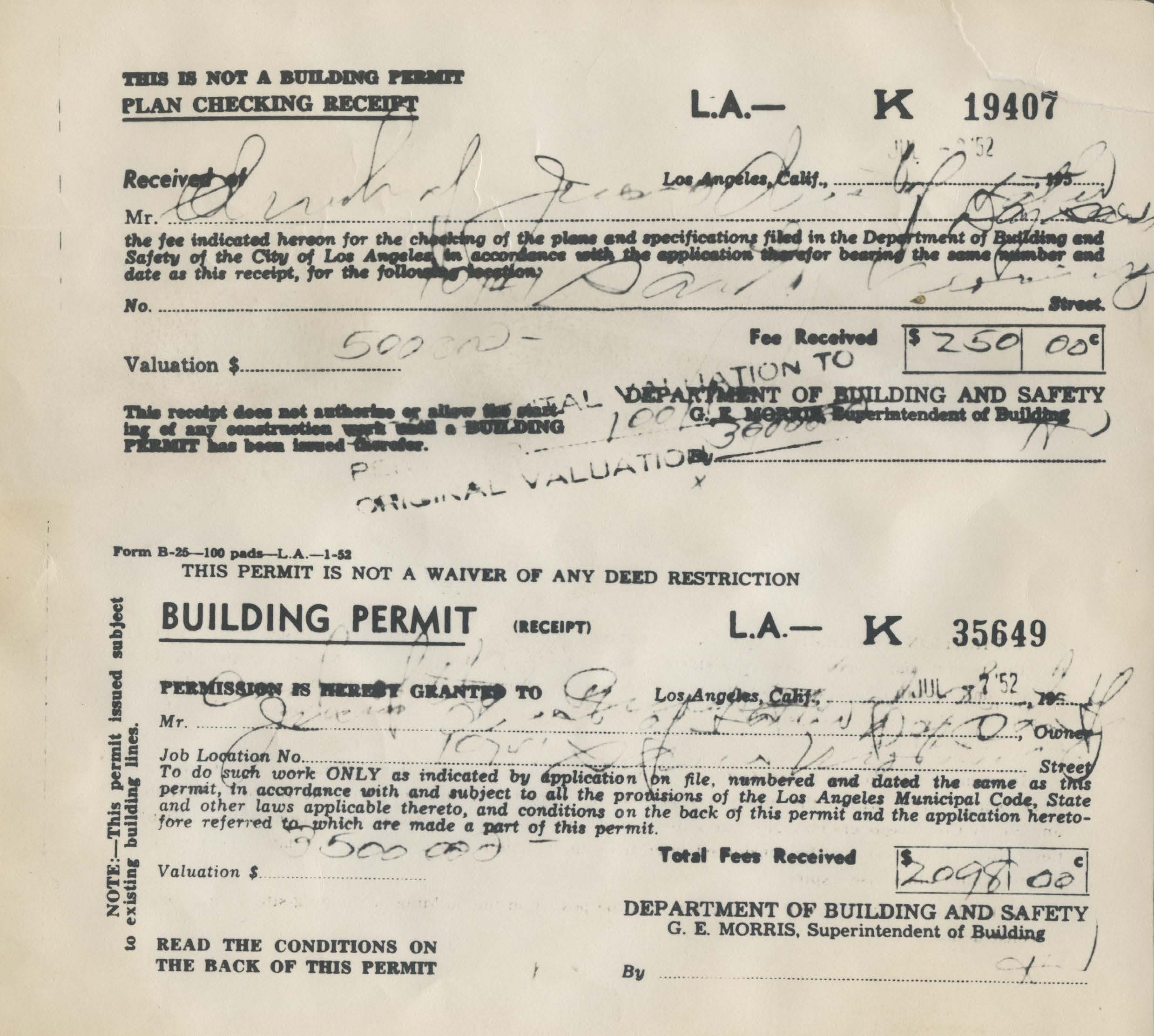

1952 City permit authorizes temple construction to begin July 7

Actual construction begins (August 11)

1953 Edward Anderson moves office to temple site (January)

Groundbreaking for mission home by President McKay (January 5)

Pouring cement for temple’s first floor is completed (February)

Westwood chapel is dedicated by Elder Harold B. Lee (April 12)

Bureau of information construction begins (July)

Heating plant construction begins (October)

Temple cornerstone laying (December 11)

1954 “Topping out” of tower steel structure (February 12)

Moroni statue is placed on tower (October 19)

On Thursday afternoon, July 3, 1952, Paul E. Iverson received the final permit from the Department of Building and Safety of the City of Los Angeles authorizing construction on the Los Angeles Temple to begin on Monday, July 7. Iverson had become the general legal counsel for the Church in Southern California following the death of Preston D. Richards in January. He gave the permit to Edward O. Anderson, temple architect, who had come from Salt Lake City for the occasion.

At a meeting on the temple site Saturday morning, July 5, Anderson formally handed the building permit to Soren N. Jacobsen, whom the Church had designated supervisor of construction. Jacobsen was born in Denmark and emigrated to America as a teenager. He went to work building houses in Iowa, and decided to stay away from Utah because he didn’t want to become a Mormon. Much to his surprise, on his way west, he was stranded in Salt Lake City, where he met and married his wife, Anna. Following the great earthquake of 1906, he supervised carpenters on important projects in San Francisco. While there, “unannounced and completely unexpected,” he joined the Mormon Church, giving up his beer and cigars. Back in Utah, he was enthusiastically active in the Church and also gained experience working with cement. Eventually he had his own contracting business. Among his major projects was the original Primary Children’s Hospital in Salt Lake City.[1]

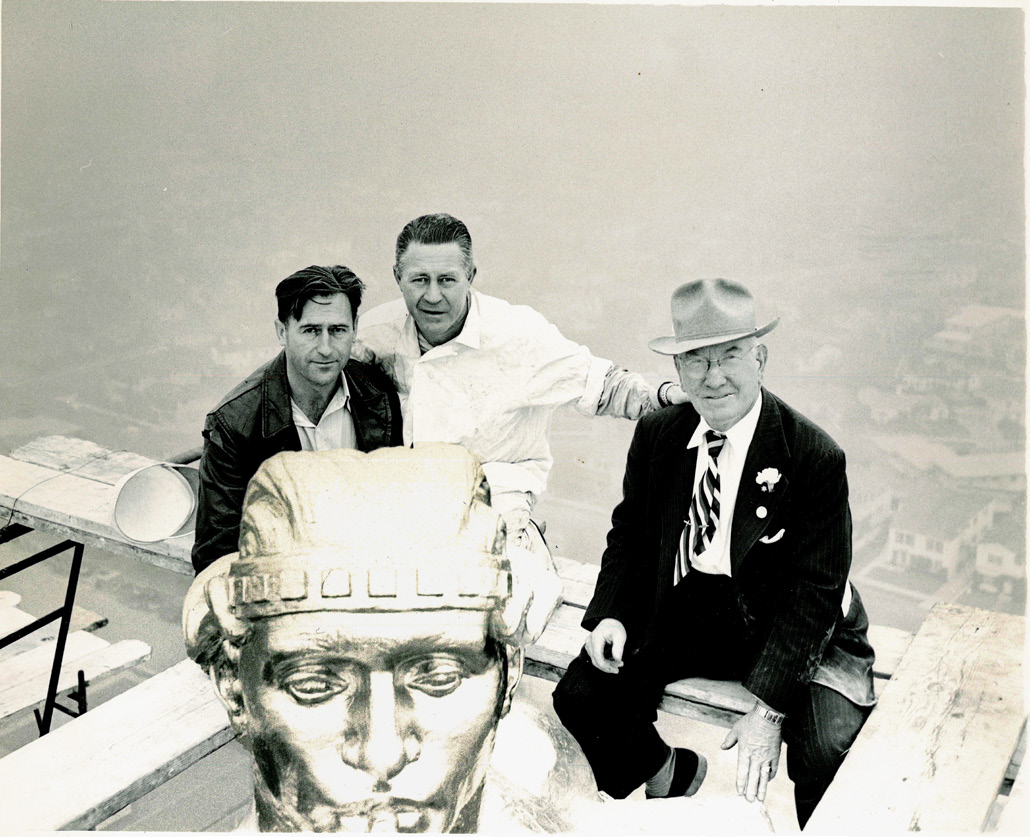

Edward O. Anderson handing the building permit to Soren N. Jacobsen as Attorney Paul E. Iverson looks on. (California Intermountain News)

Edward O. Anderson handing the building permit to Soren N. Jacobsen as Attorney Paul E. Iverson looks on. (California Intermountain News)

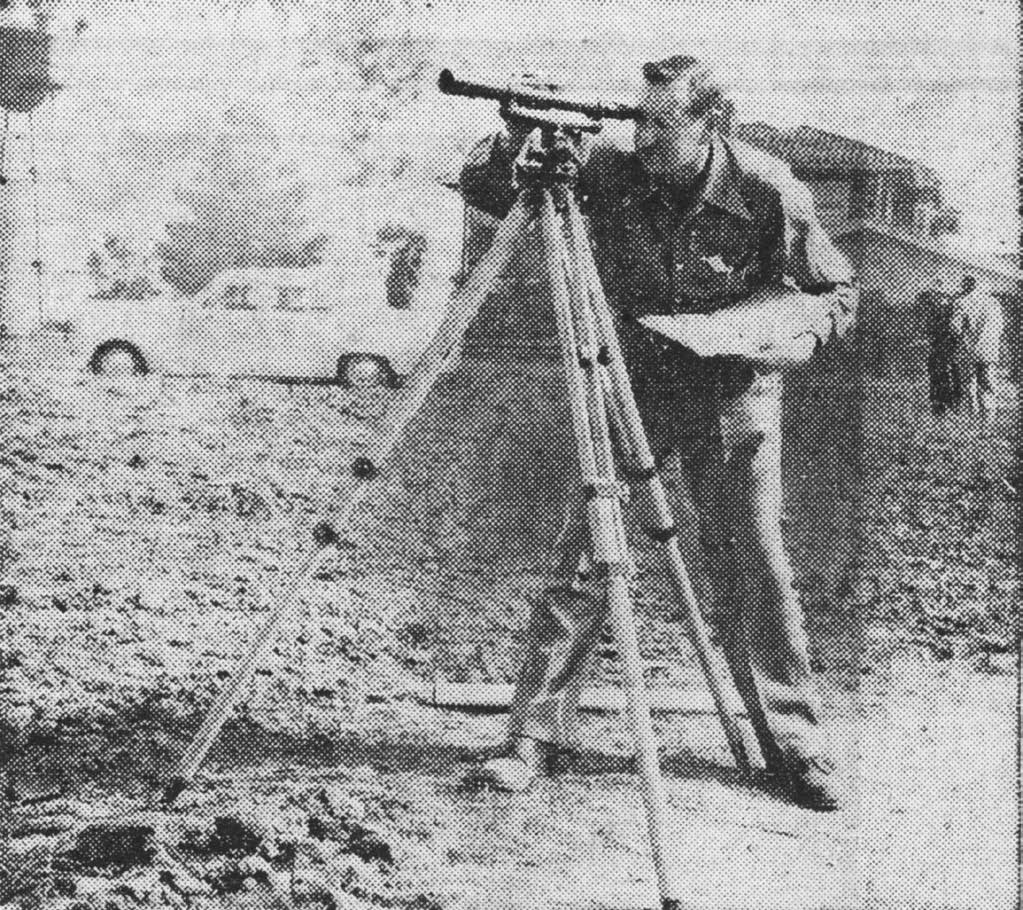

He and his sons would later form a construction company that would build more than a dozen temples for the Church. Those also attending the July 5 meeting included Paul E. Iverson, general counsel; Harold Burton, architect of the ward chapel and mission home that would be built on the property; Douglas Burton; Richard C. Sharp of Salt Lake City, who was assigned to be architectural inspector; R. E. Caldwell, head of the Church building committee in Southern California; Noble Waite, president of South Los Angeles Stake and executive chairman of the temple committee; Hugh C. Smith, president of San Fernando Stake and chair of the publicity committee; Ned Redding, in charge of press relations (and publisher of the weekly California Intermountain News, a Southern California Latter-day Saint newspaper); contractors William and Harold Jackson; Harry Beitler, surveyor; as well as Art Mortenson, Ellis Craig, Joseph Lundstrom (who would submit numerous articles to the Church News), Howard Winn (who would make a photographic record of temple construction), and Lyman Pinkston, members of the public information committee.[2]

With the building permit in hand, the plan was to finish leveling the ground and to put in roads, curbs, and sidewalks before actual construction on the temple could begin. The Jackson Brothers Construction Company had begun this work—the first major contract of the temple building project. William and Harold Jackson, members of the Beverly Hills (later Westwood) Ward, had built shopping centers and other significant projects in the Los Angeles area.[3]

Construction Begins

Harry Beitler, surveyor. (California Intermountain News)

Harry Beitler, surveyor. (California Intermountain News)

President David O. McKay was on hand to witness the first load of lumber being delivered to the temple site on Monday morning, August 11, 1952. Some of the lumber would be used in remodeling the elegant home of movie star Harold Lloyd into the on-site headquarters for temple construction. The Church President was there that morning to meet with Edward O. Anderson, Soren N. Jacobsen, members of the Church building committee, and local officials and contractors. He had the honor of offering the prayer on the first day workmen appeared on the site to begin building the temple. “President McKay went over the entire grounds, helped to settle some minor issues on the spot, and cleared the way for the commencement of actual construction.”[4] Following the meeting, Jacobsen suggested that excavation work could commence that same afternoon.

Standing in front of the Harold Lloyd home are architect Harold Burton, contractor William Jackson, surveyor Harry Beitler, and contractor Harold Jackson as they examine site plans. (California Intermountain News)

Standing in front of the Harold Lloyd home are architect Harold Burton, contractor William Jackson, surveyor Harry Beitler, and contractor Harold Jackson as they examine site plans. (California Intermountain News)

Beginning that week, the temple site became a beehive of activity. Powerful bulldozers and graders were leveling the ground, moving earth around, and storing some for future use. Utilities, including gas and water pipelines, were being rerouted where necessary. Workmen were also busy constructing sheds to house equipment and supplies. It was obvious that the long-anticipated construction of the temple was finally underway.

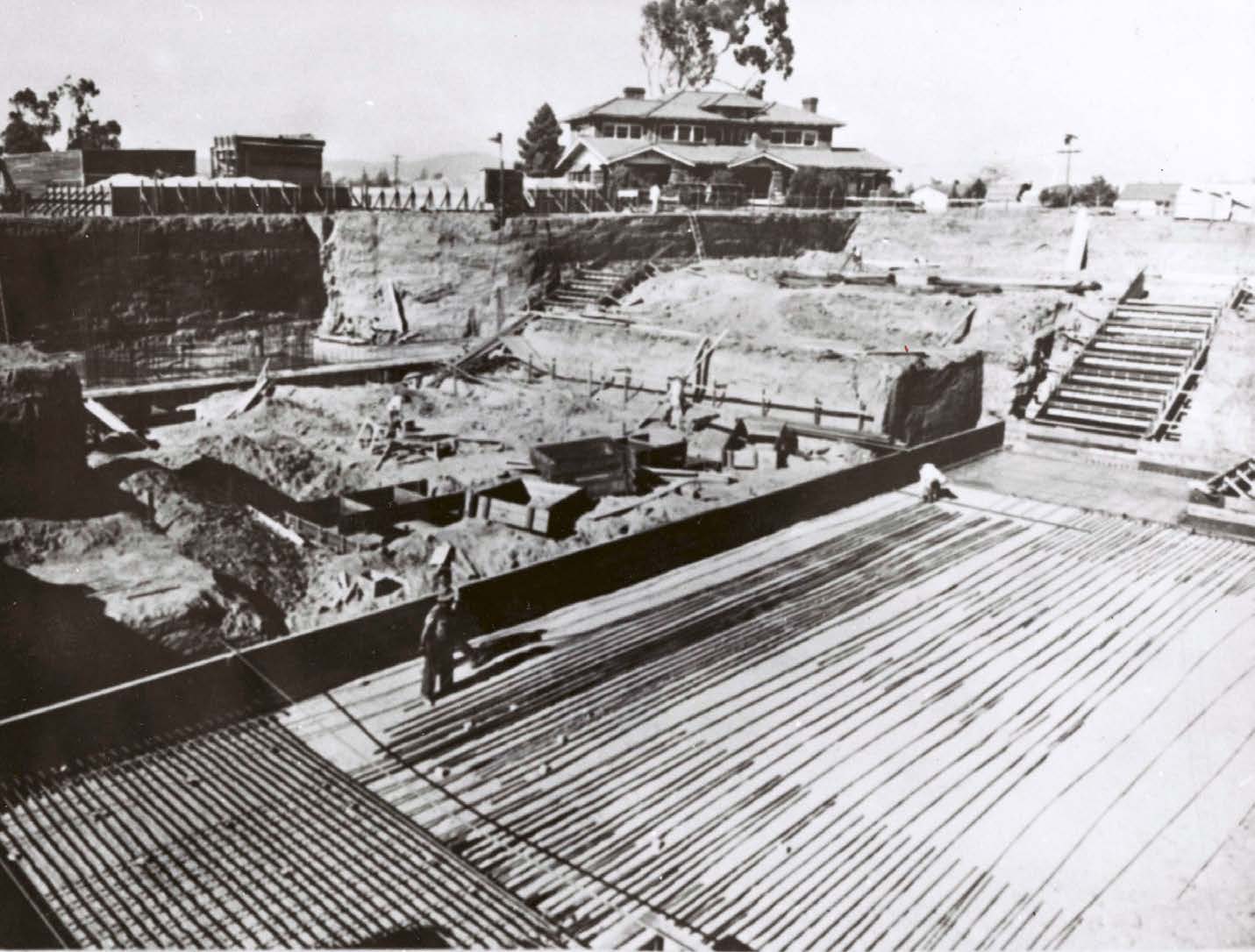

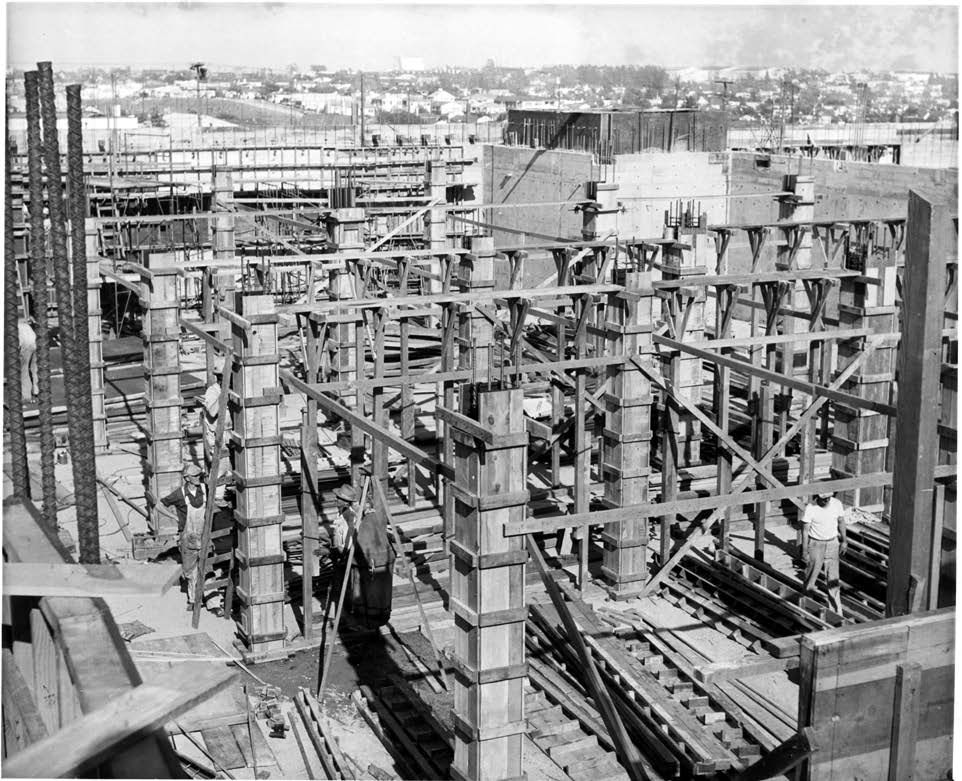

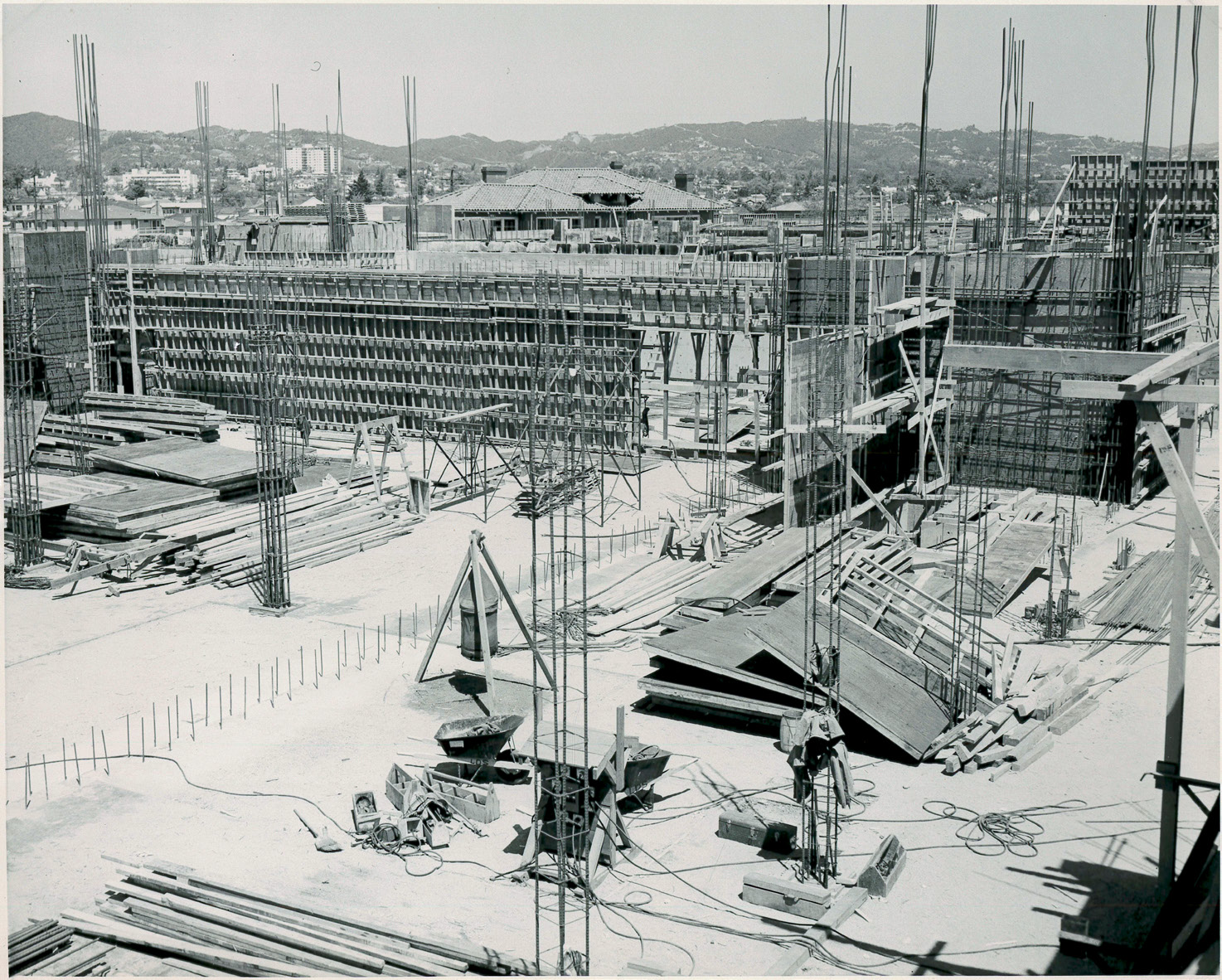

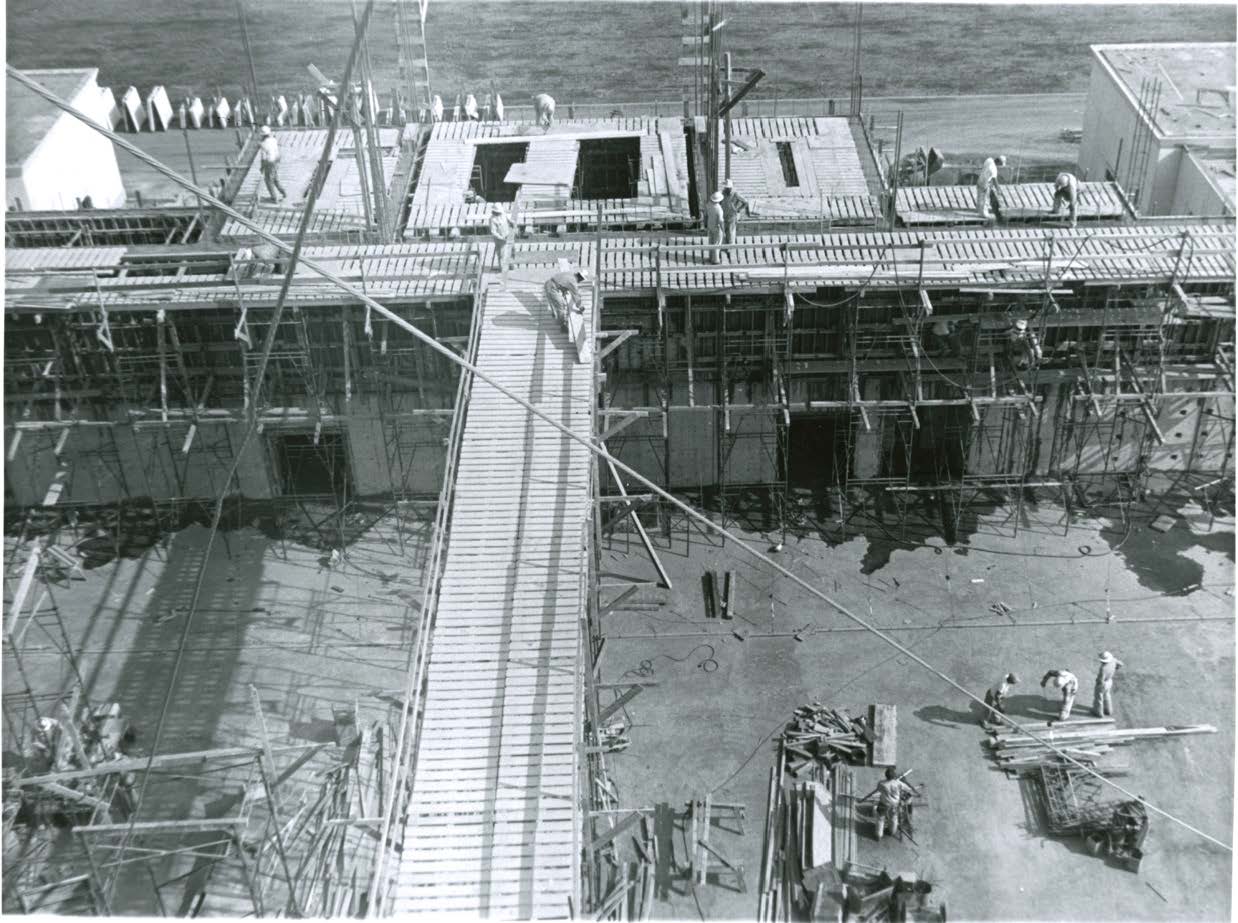

Some 25,000 cubic yards of earth were excavated for the temple’s footings, foundation, and basement, reaching a depth of more than 25 feet. “Since the temple is being built on very hard ground,” the architect explained, “shovels operated by compressed air [were] required to trim up the trenches.”[5]

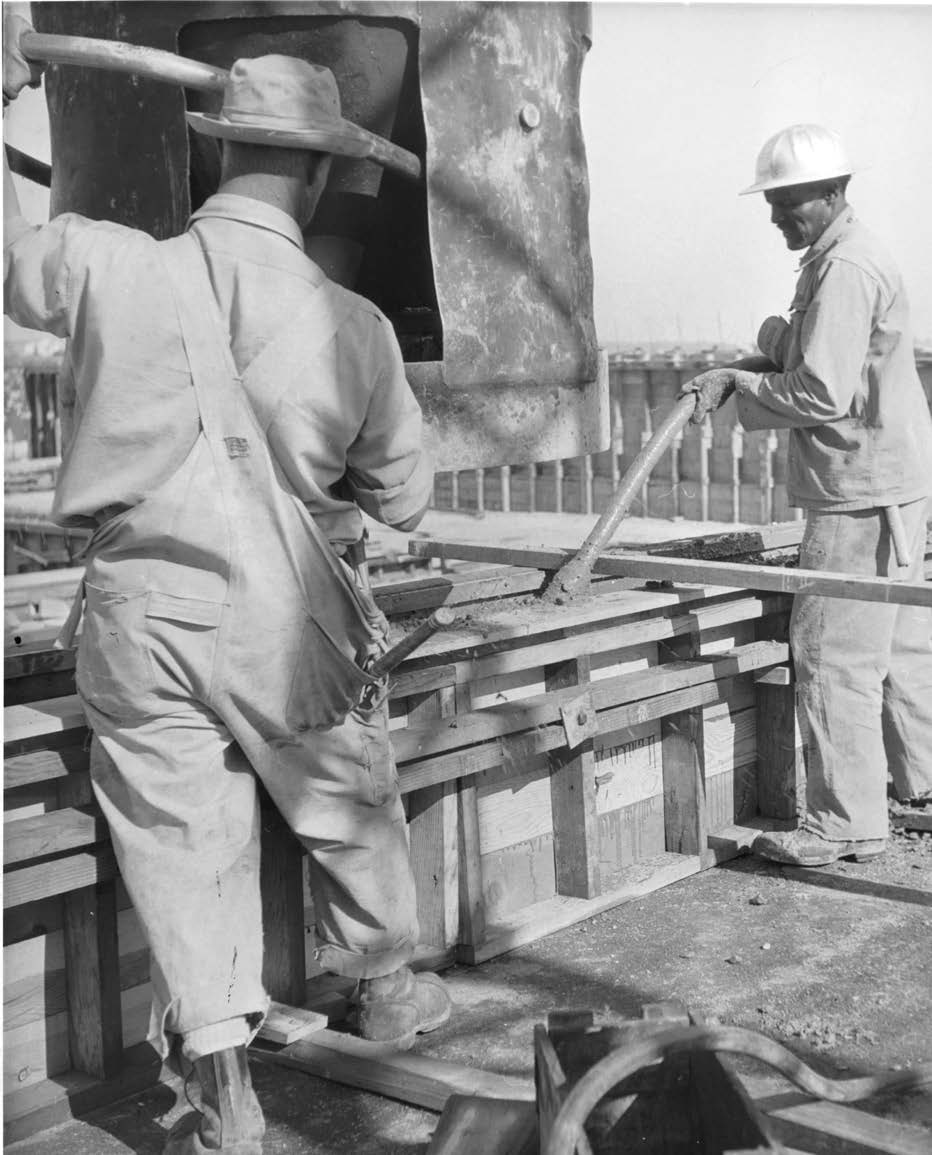

By October 1952 cement was being poured. It was mixed on-site, with the precise blend of carefully selected sand, gravel, cement, and water monitored to produce concrete with the needed quality and strength. By means of a large crane, the wet cement was lowered bucket after bucket to workmen waiting the equivalent of two stories below. On a single day that month, 385 yards of cement were poured into frames surrounding reinforcing steel rebar to form one of the two massive footings located in the center of the building.[6]

In December, Edward O. Anderson, who had been serving as the supervising architect for the whole Church, was relieved of responsibility for all other projects so he could devote his full time to the temple. He had just returned from inspecting Church buildings in the South Pacific. His new title would be “supervising architect for the Los Angeles Temple.” In the early days of the New Year, he moved his family from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles and officially established his office in the former Harold Lloyd home. This move allowed Richard G. Sharp, who had acted as Anderson’s on-site representative, to return to his work in the architect’s office at Church headquarters. Thus Anderson, who had designed the temple, would be in a position to personally direct its construction.[7]

Excavation begins. (George Bergstrom, courtesy of the Church History Library [CHL])

Excavation begins. (George Bergstrom, courtesy of the Church History Library [CHL])

The architect described construction procedures as “systematic” and “efficient.” “Details of construction are taken up first with the architect by the head foreman, Elder Severne D. Loder; the project engineer, Elder Virge M. Butler; and the construction supervisor, Elder Soren N. Jacobsen. Drawings are made for the concrete forms in the shop drafting room on the site; shop drawings of sub-contractors and of all manufactured items are checked by the architect; they are then rechecked with the foreman and the project engineer. When finally approved, they are sent to the sub-contractors and to the manufacturers for fabrication. Only the best materials are being used in the construction of the temple.”[8]

In earlier years, Church members had enjoyed a feeling of brotherhood and involvement as they worked along with professional craftsmen in building their local meetinghouses. Therefore, many members had hoped they could donate labor as well as money to building the temple. This was not possible, however, because the contractor was using only union labor for at least two reasons—to ensure consistent quality and to avoid possible liability. This second concern was underscored by a tragic accident during construction of the adjoining ward chapel, when a scaffold collapsed, dropping two volunteers to the ground below; one had only minor injuries, but the other suffered a spinal injury causing permanent quadriplegia. In the wake of this event, the company insuring temple construction issued a “notice of cancellation” covering workmen “because they will not take the policy with the provision of contributed labor.”[9] Still, qualified Latter-day Saint craftsmen were hired when possible. Dakon Broadhead, a counselor to Howard W. Hunter in the Pasadena Stake presidency, coordinated this employment effort.[10]

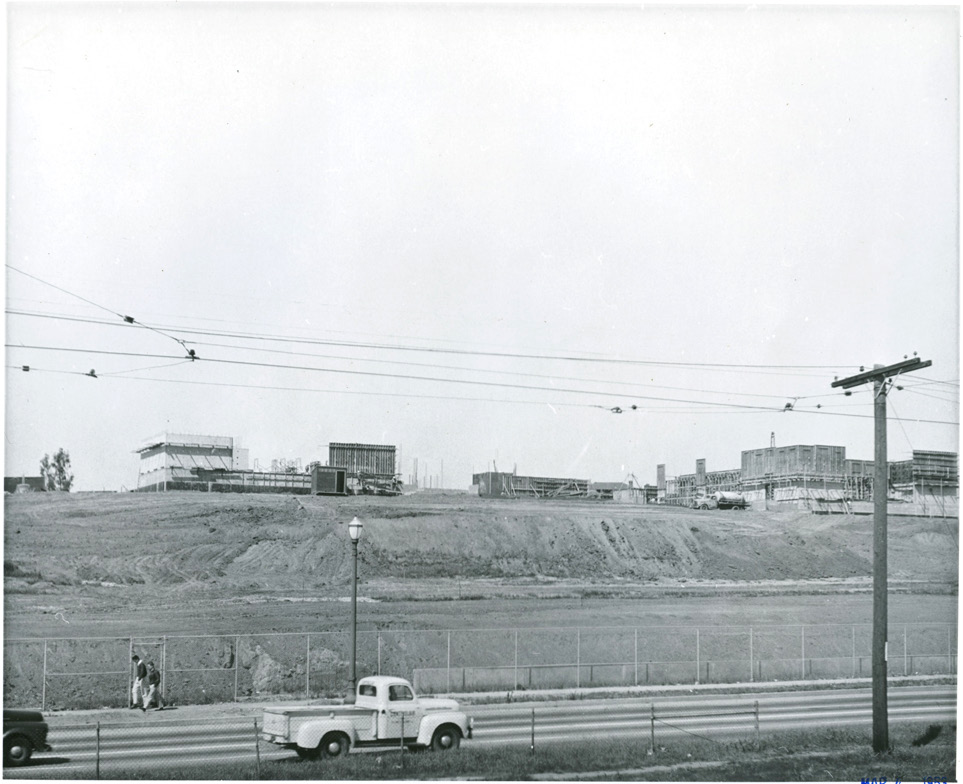

The view from Overland Avenue, September 1952. (Paul L. Garns)

The view from Overland Avenue, September 1952. (Paul L. Garns)

Many workers found building the temple to be a spiritual experience. The builders, only about eighty percent of whom were Church members, felt the need for divine assistance. After checking in for work each morning, they had the opportunity to gather for prayer, and most participated. Among them were men who had never prayed before in their lives or who didn’t even believe in prayer. As construction progressed, however, some of these men were so touched by the devotionals that they eventually requested the privilege of leading the prayer themselves.[11] Four even asked for baptism. One, whose wife was a Church member, sent his son on a mission; upon the missionary’s return, he baptized his father. One carpenter had worked on the temple in Mesa during the 1920s. Although he was not a member of the Church, he now moved from Arizona specifically to work on the Los Angeles Temple. “I’ve learned to love the Mormon people,” he acknowledged, “and I’m now a regular attender at the Mormon services at the Westwood Ward chapel.”[12] The workers felt they were blessed, as construction was completed without serious accident. Furthermore, during a particular three-month period, it rained almost every weekend, but never enough during the week to interfere with the work.[13]

Excavation continues (Harold Lloyd’s home in the background), September 1952. (Paul L. Garns)

Excavation continues (Harold Lloyd’s home in the background), September 1952. (Paul L. Garns)

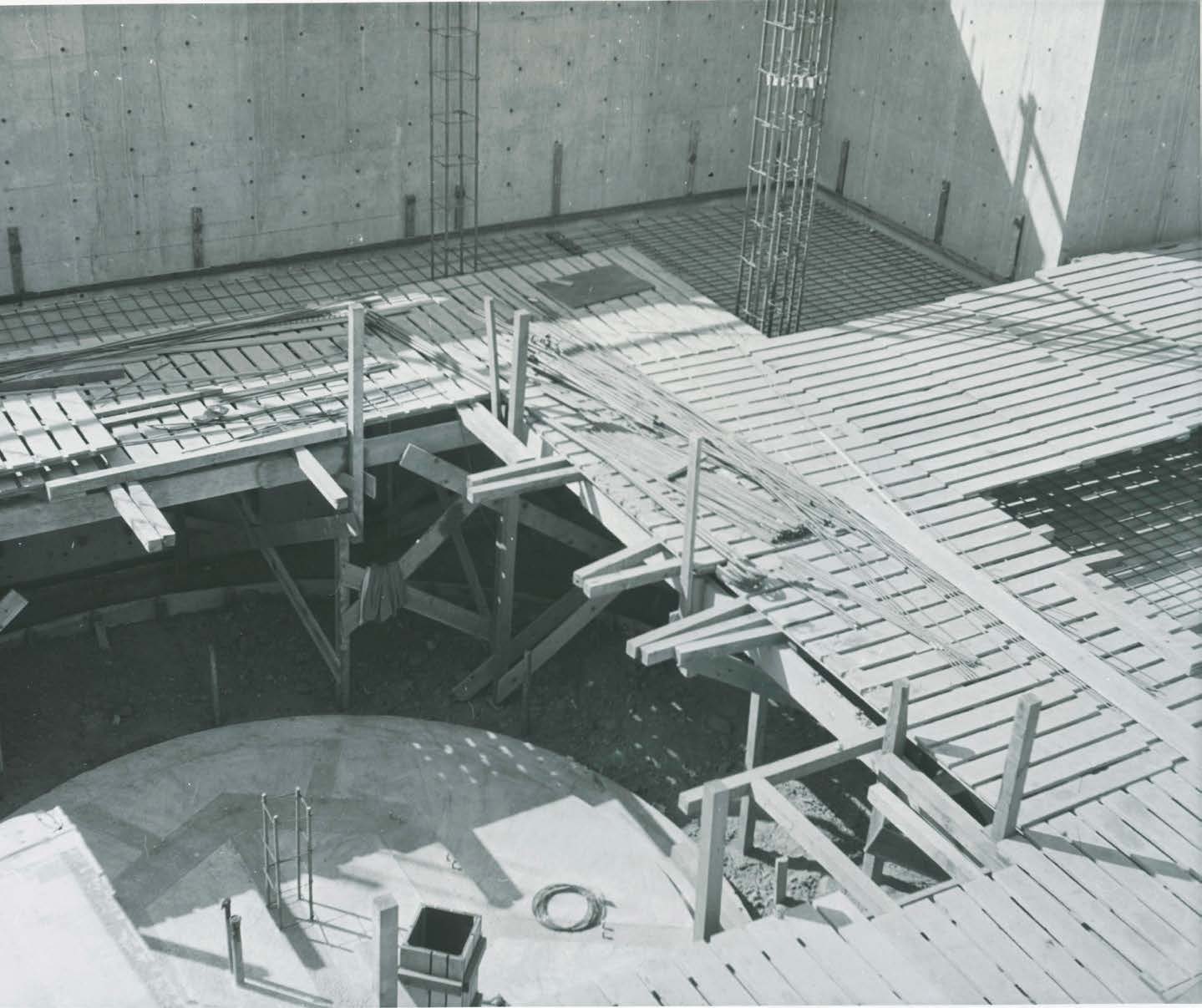

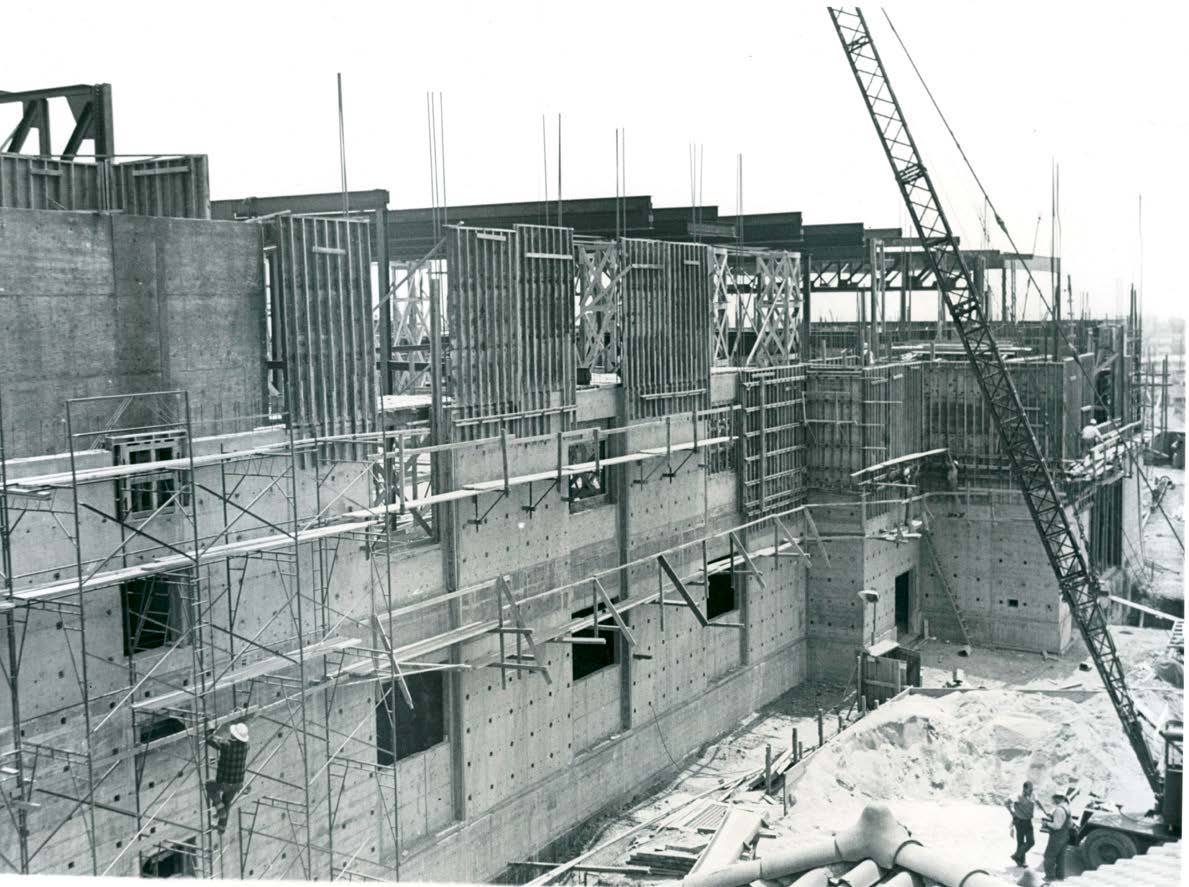

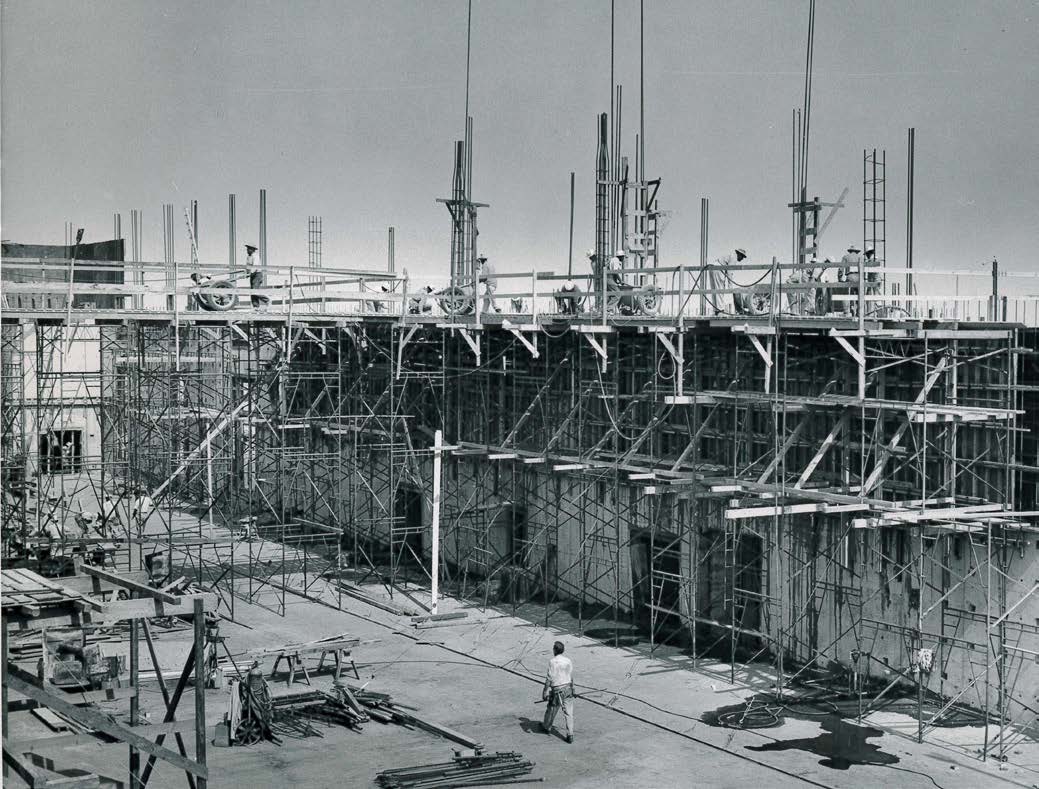

The temple was built of reinforced concrete and structural steel, specifically engineered to withstand Southern California’s earthquakes. Foundation walls were two feet thick and extended to a depth of at least 24 feet. Early in 1953, architect Anderson reported: “Work is running well ahead of schedule. Forms are being built. Reinforcing steel is being placed, and concrete is being poured.” By this time, foundation and basement walls were completed, and concrete for the first floor was poured beginning early in February.[14] By early March, first-floor walls began to rise. Favorable weather during the winter allowed cement to be poured at a faster rate than planned, so the schedule was revised from 200 to 300 cubic yards per week. At this pace, contractors anticipated that all concrete work could be completed within one year.

Arranging the rebar for the basement floor, October 8, 1952. (George Bergstrom)

Arranging the rebar for the basement floor, October 8, 1952. (George Bergstrom)

During the first half year of construction, 5,690 cubic yards of cement and more than 300 tons of reinforcing steel had been put into the temple. Drainage facilities, heating and ventilation ducts, and miles of electrical conduits were already being placed into the cavernous basement spaces. At this time, approximately 145 men were employed directly on temple construction, and 50 to 60 specialists or employees of subcontractors were also present on the property.[15]

Church President David O. McKay took a keen personal interest in the temple’s construction. During his frequent visits to Southern California, he avidly followed each phase of the work. He freely shared suggestions and offered encouragement to his lifelong friend Soren Jacobsen.[16] Still, on one of his visits he reportedly remarked that he couldn’t imagine that he had ever approved such a massive building project.[17] On another visit, however, President McKay declared, “It’s marvelous,” as he expressed appreciation for the quality and pace of construction.[18]

Digging deeper, September 1952. (Paul L. Garns)

Digging deeper, September 1952. (Paul L. Garns)

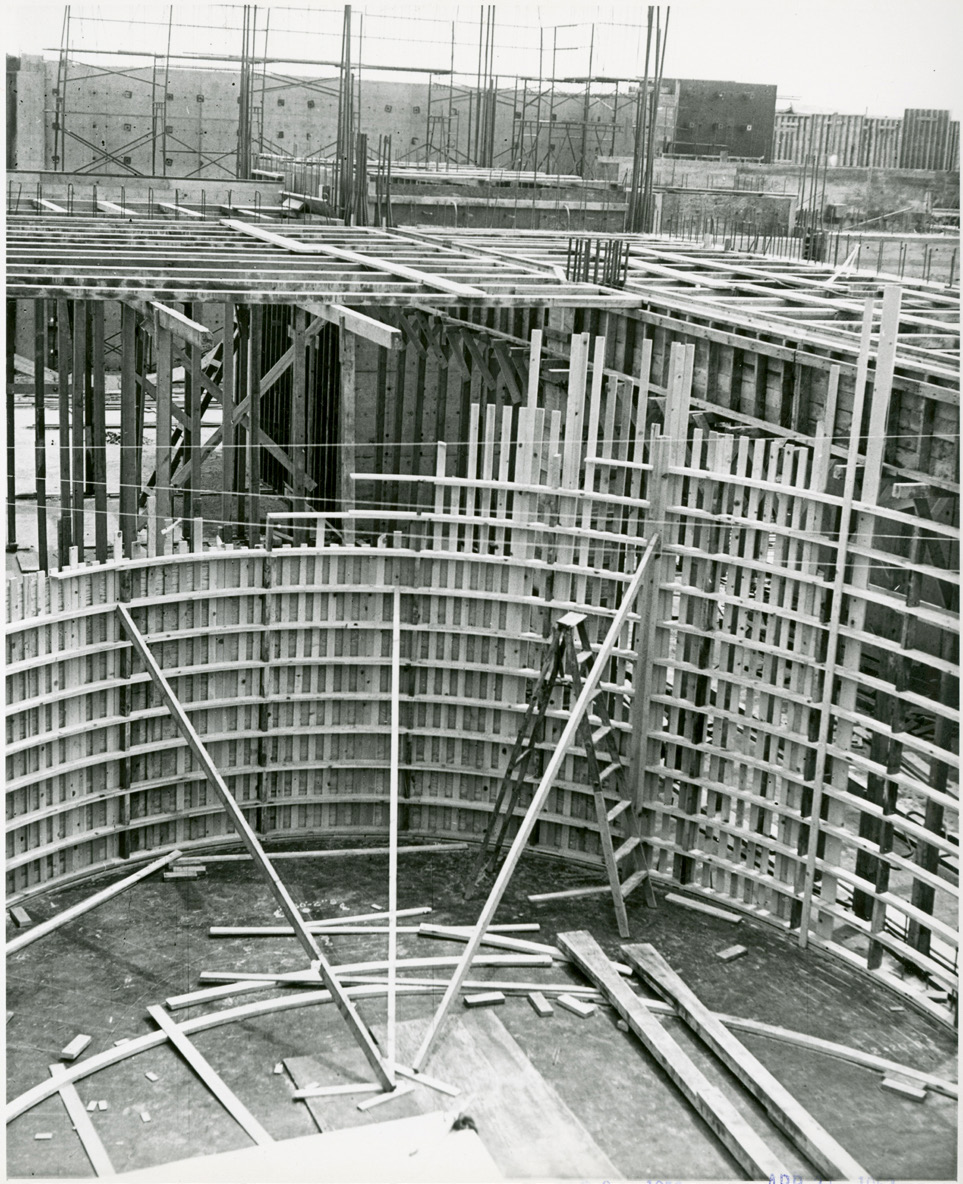

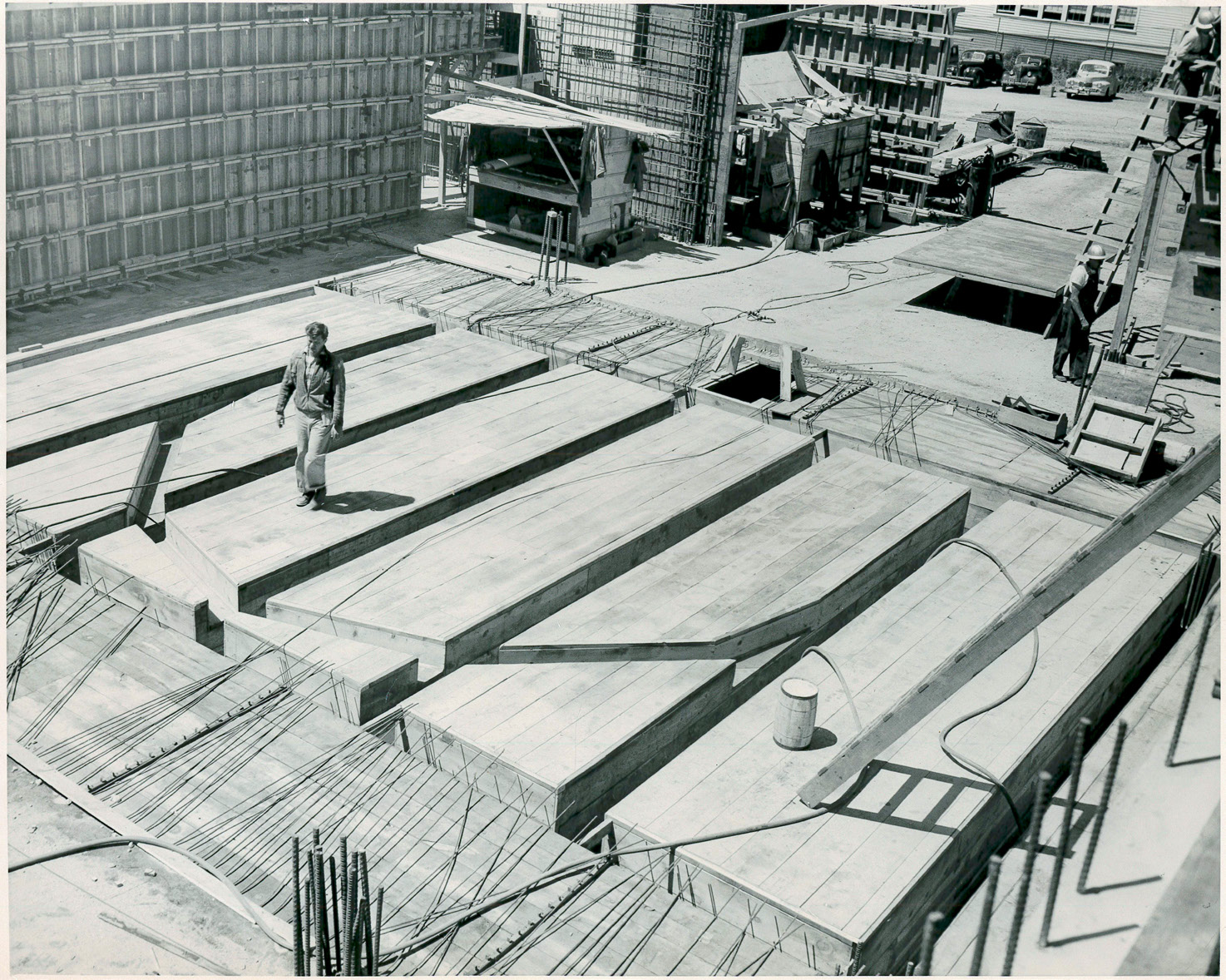

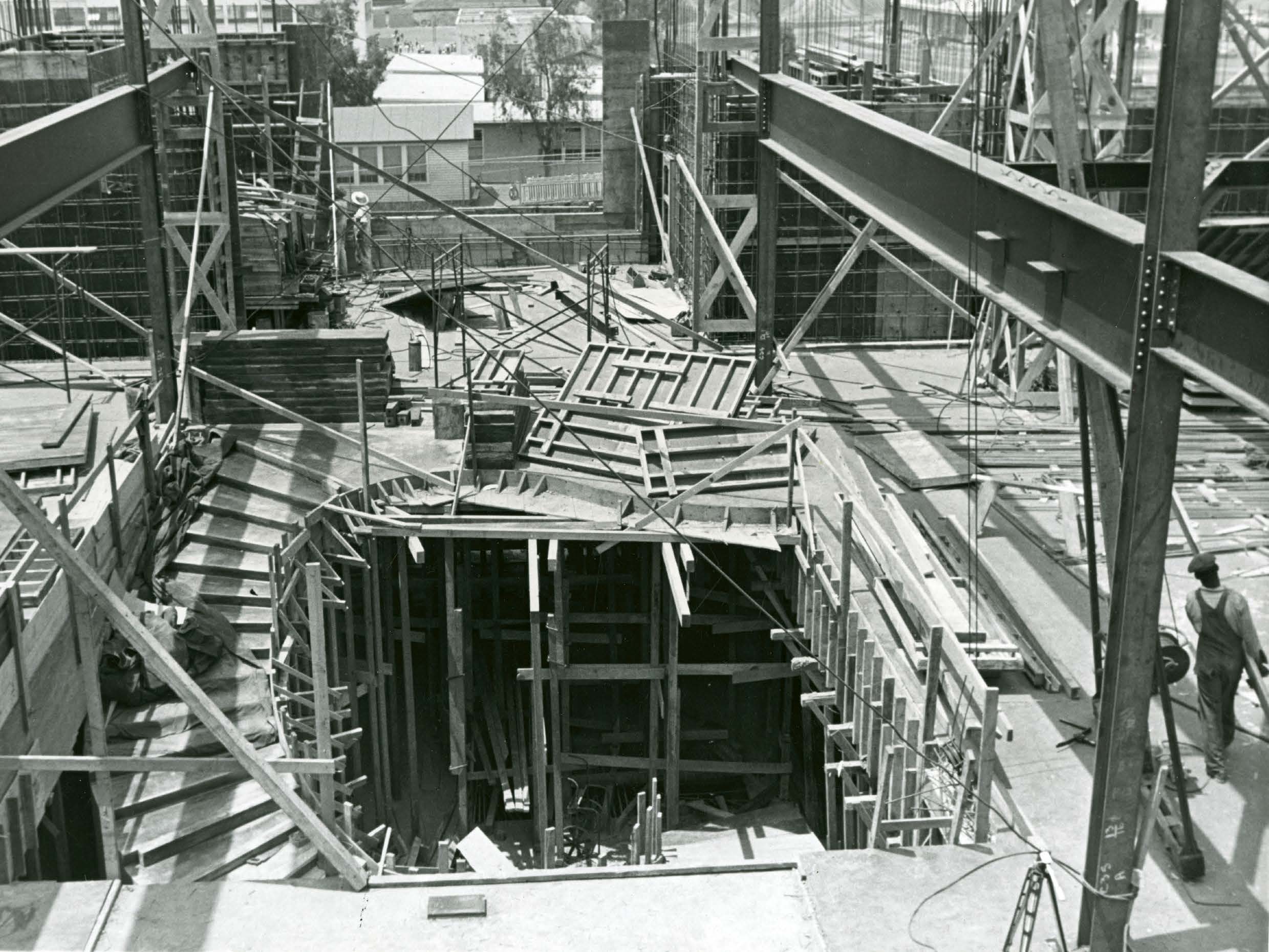

Two of the temple’s beautiful features began to be visible as construction pushed toward the second floor. A grand spiral stairway near the center of the building would ascend 16 feet from the first to the second floor. Each of the thirty-two steps would be 5½ feet wide. The rising walls also revealed the space for the temple’s main entrance. The majestic bronze doors would be 26 feet high. In September, the precast stone bearing “delicate script letters eight inches high” proclaiming the structure’s true nature—“The House of the Lord, Los Angeles Temple”—was put in place just west of this main entrance.[19]

Perfection was the standard for all work. Construction supervisor Soren Jacobsen was responsible for meeting this standard. He was assisted by construction superintendent Vern Loder, chief engineer Virge Butler, and concrete supervisor Dick Drysdale. After most of the crews had left for the day, these men could be seen walking through the building, checking on the work which had been done and planning projects for the next day.

The Los Angeles Temple construction site, November 3, 1952. (Edward O. Anderson Collection, CHL)

The Los Angeles Temple construction site, November 3, 1952. (Edward O. Anderson Collection, CHL)

For example, the evening before a portion of the second floor was to be poured at 7:00 a.m., Butler noted that a few pieces of steel reinforcing rod had been omitted. “Not much, just a bar here and a rod there. The concrete could have been poured and nobody would have ever known. The concrete was poured, and on time the next morning, but not before the steel men were on the job several hours ahead of time to get the proper amount of steel in place.”[20]

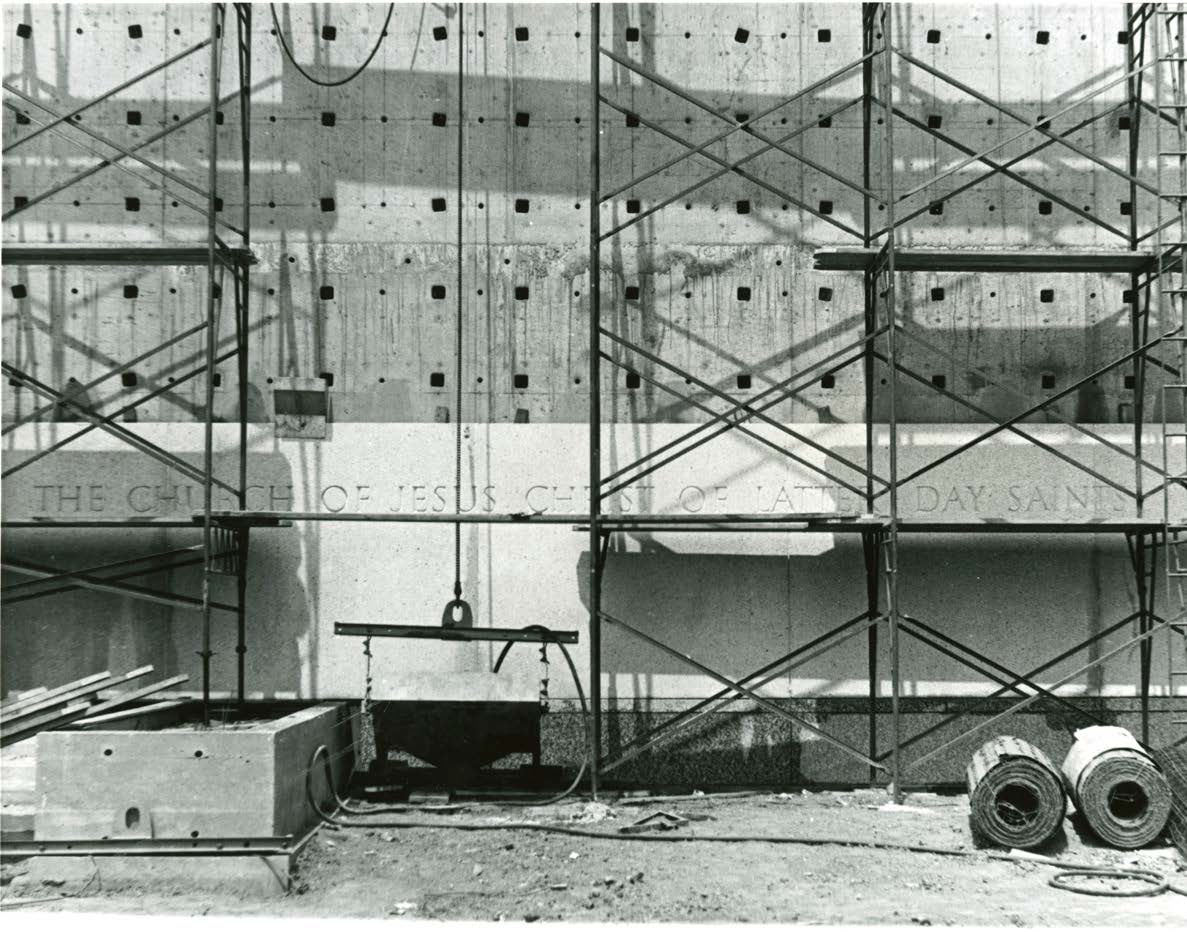

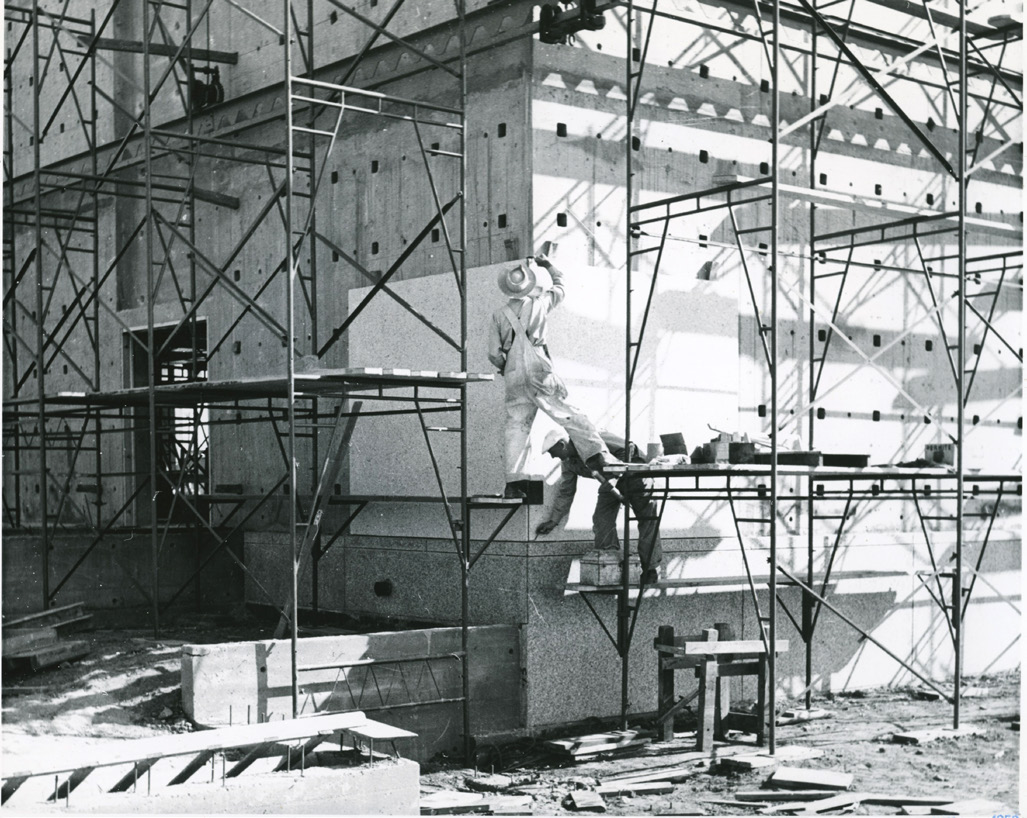

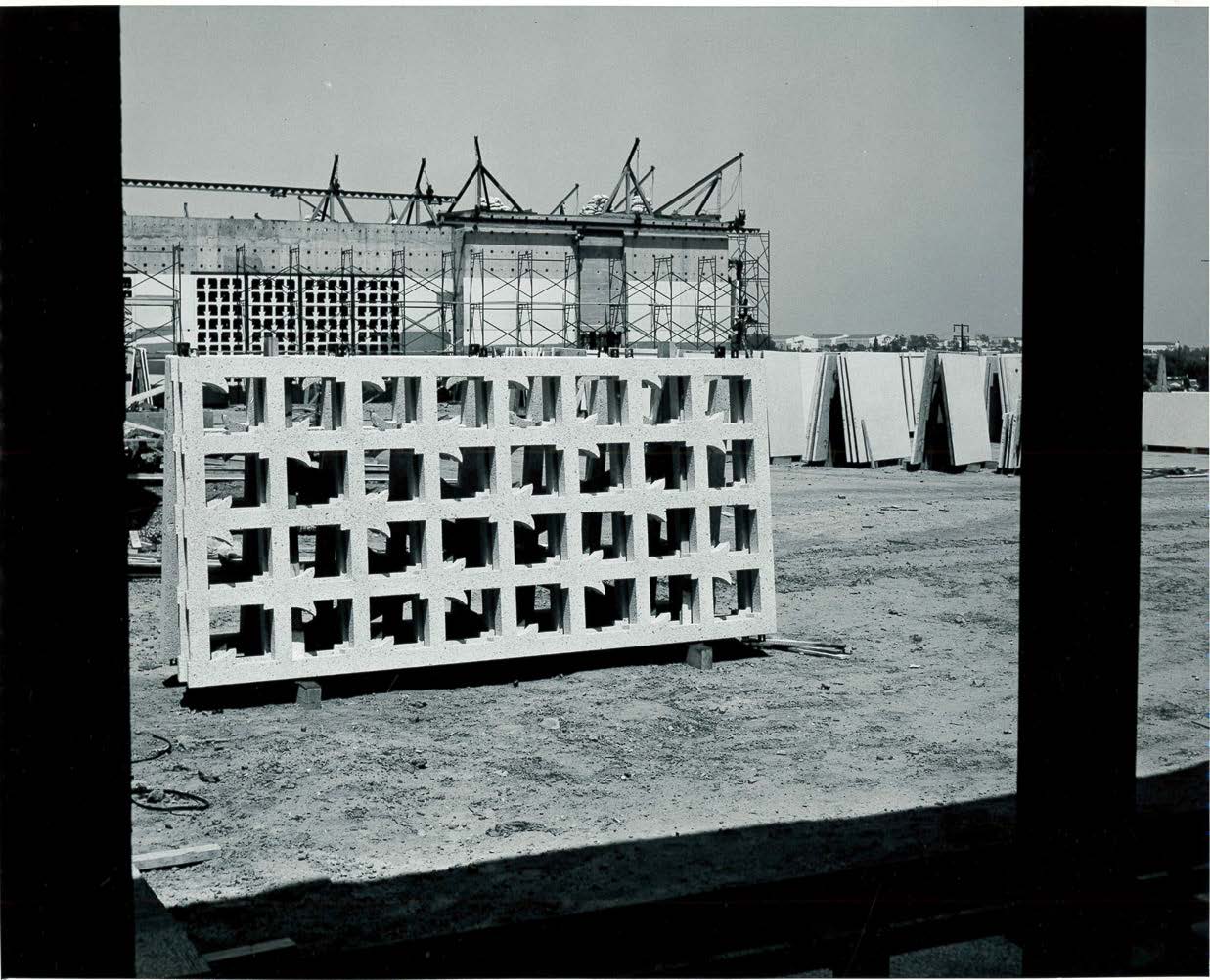

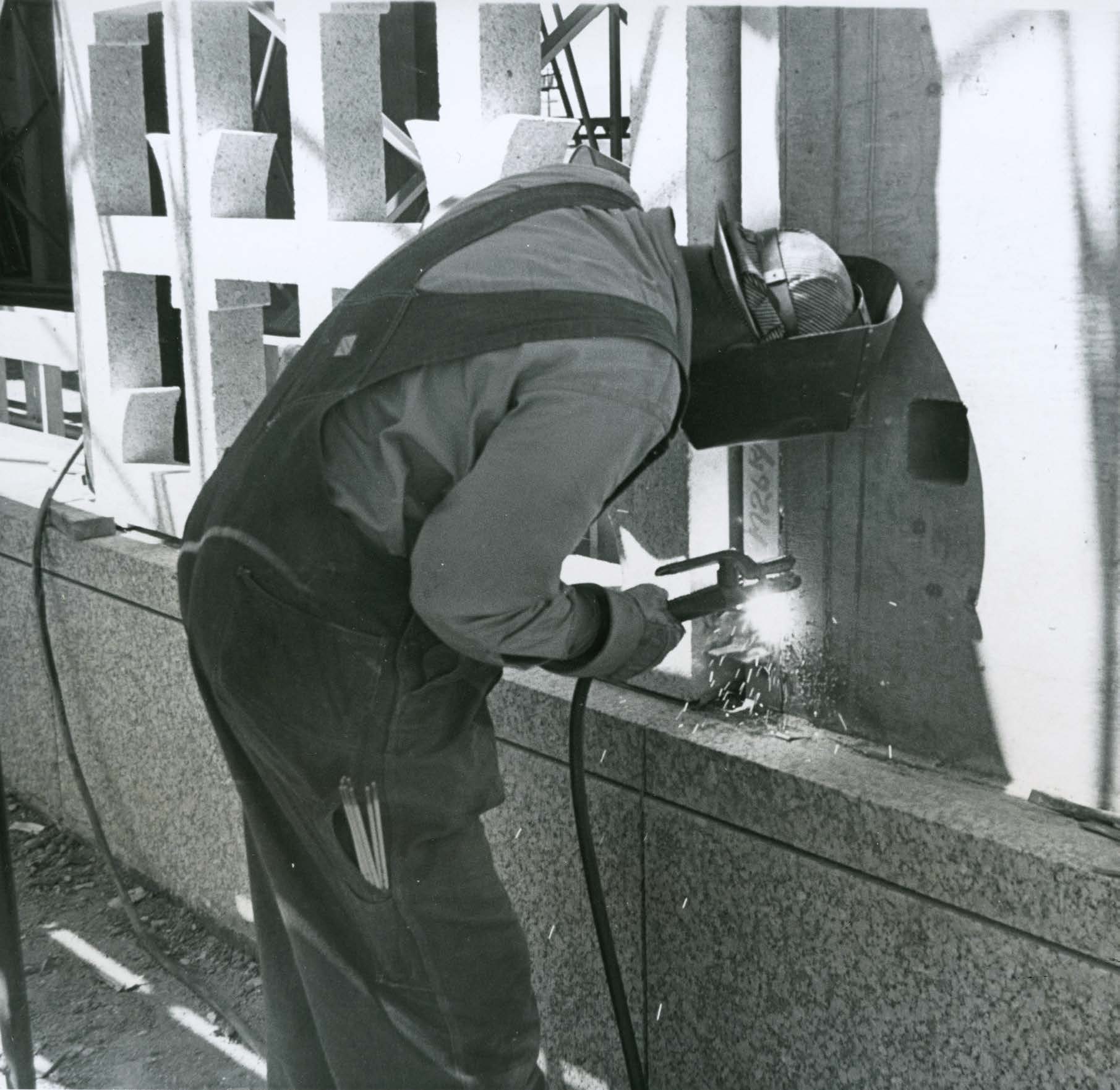

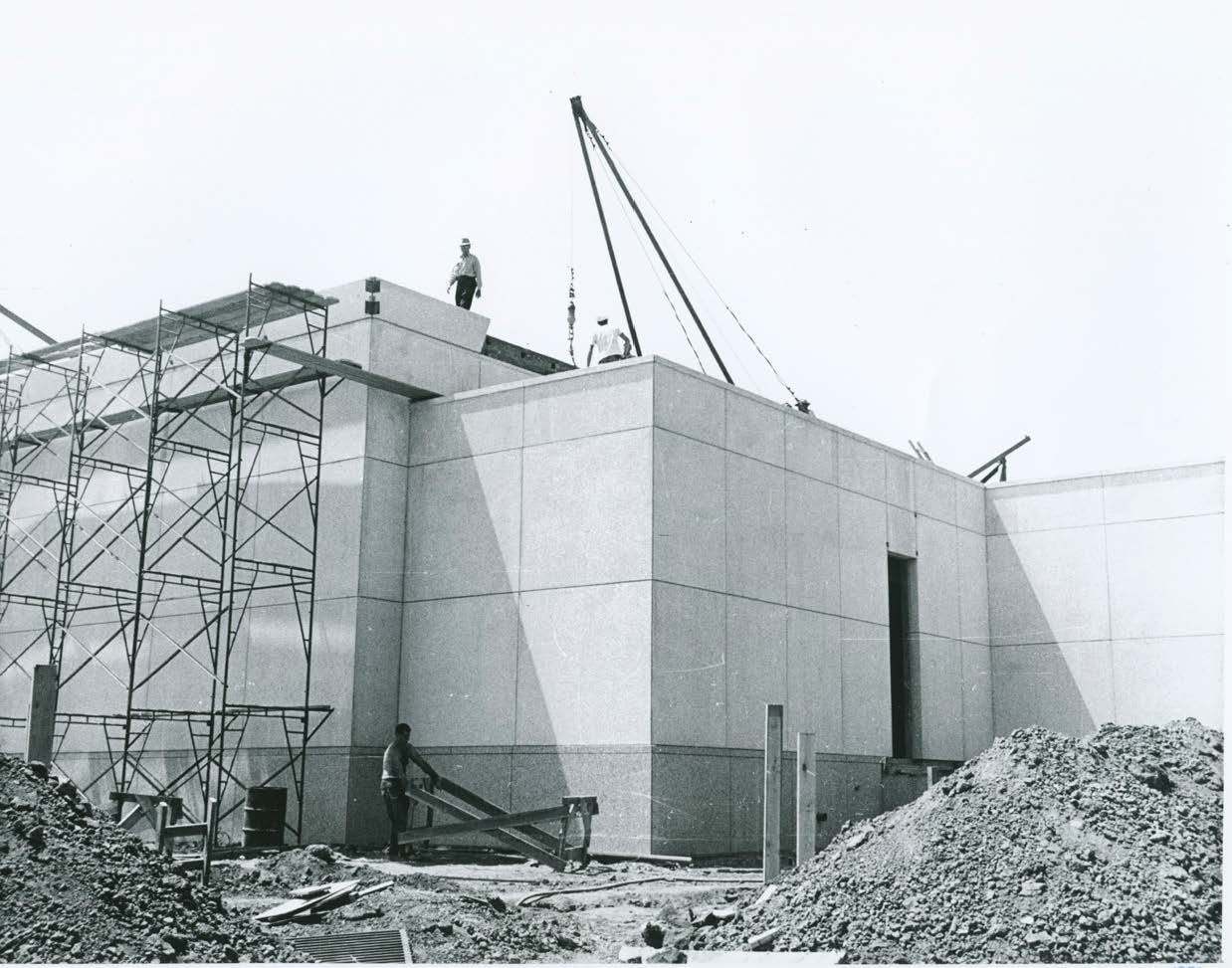

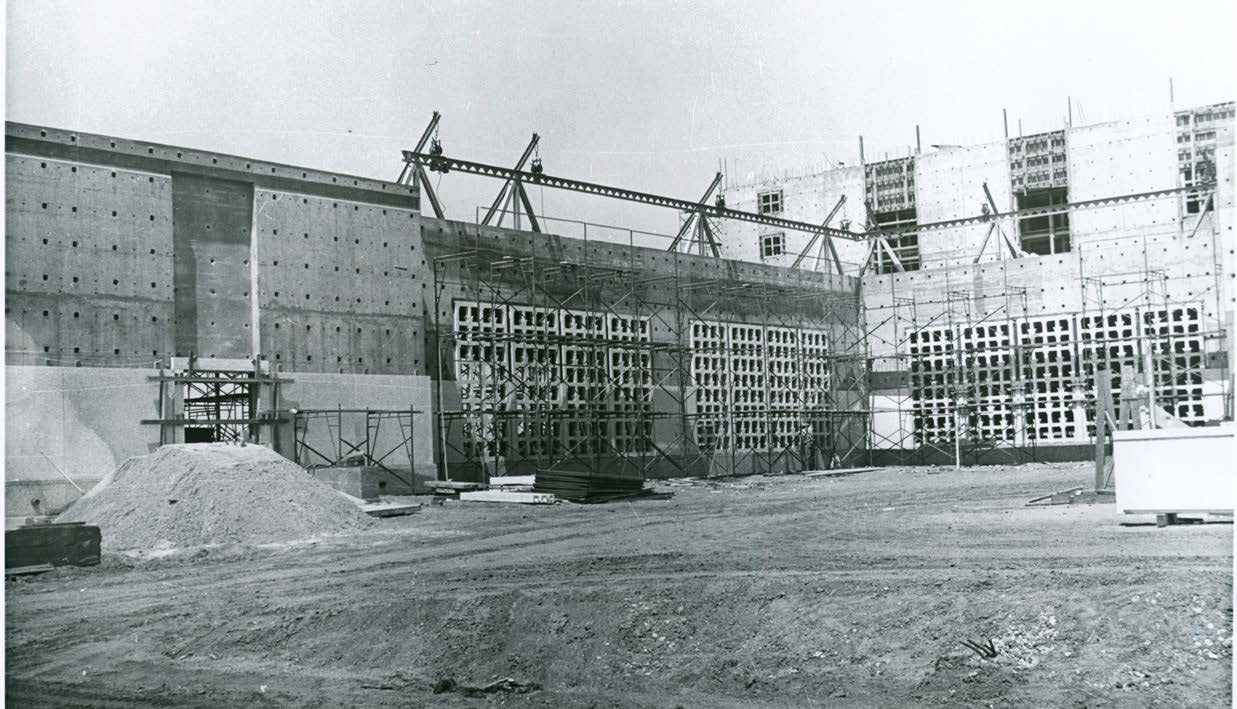

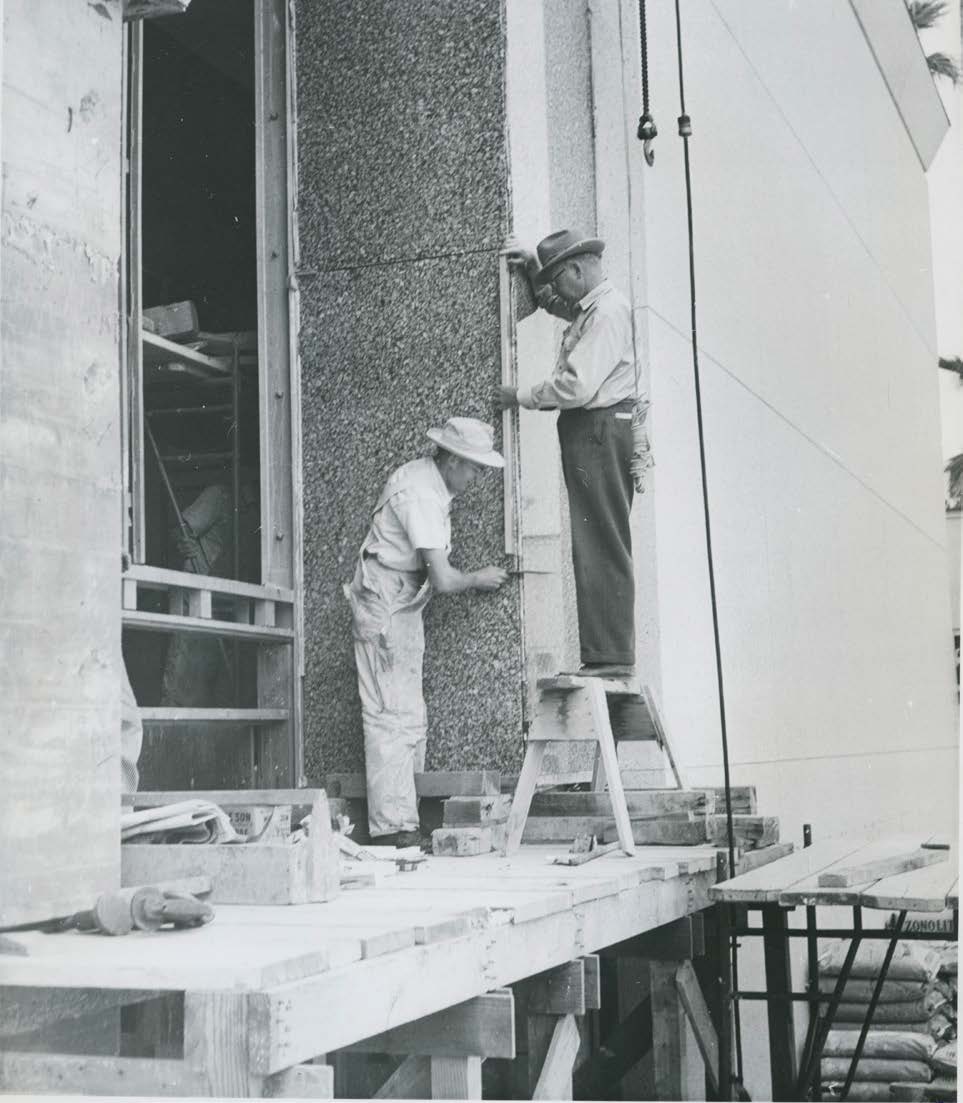

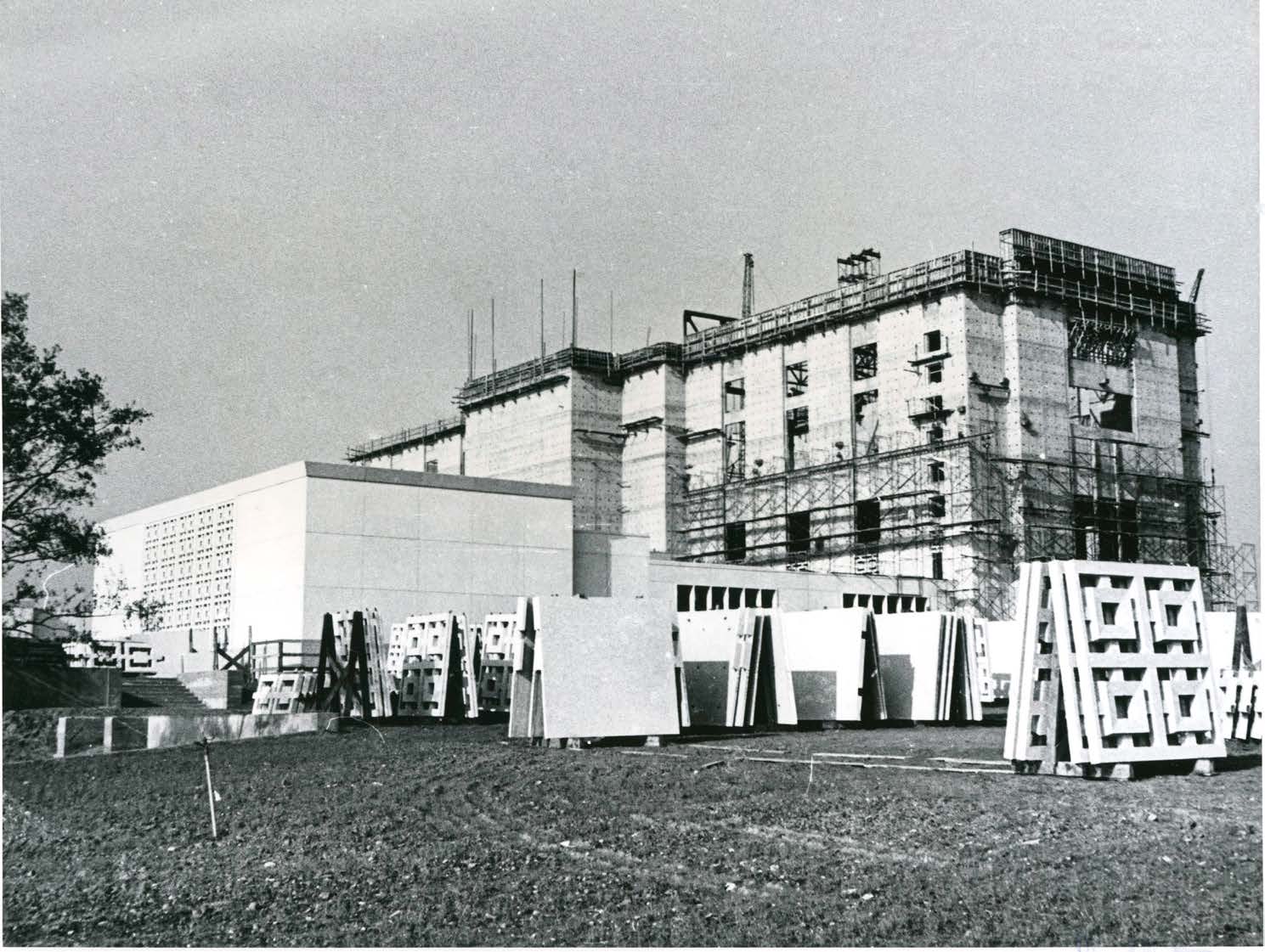

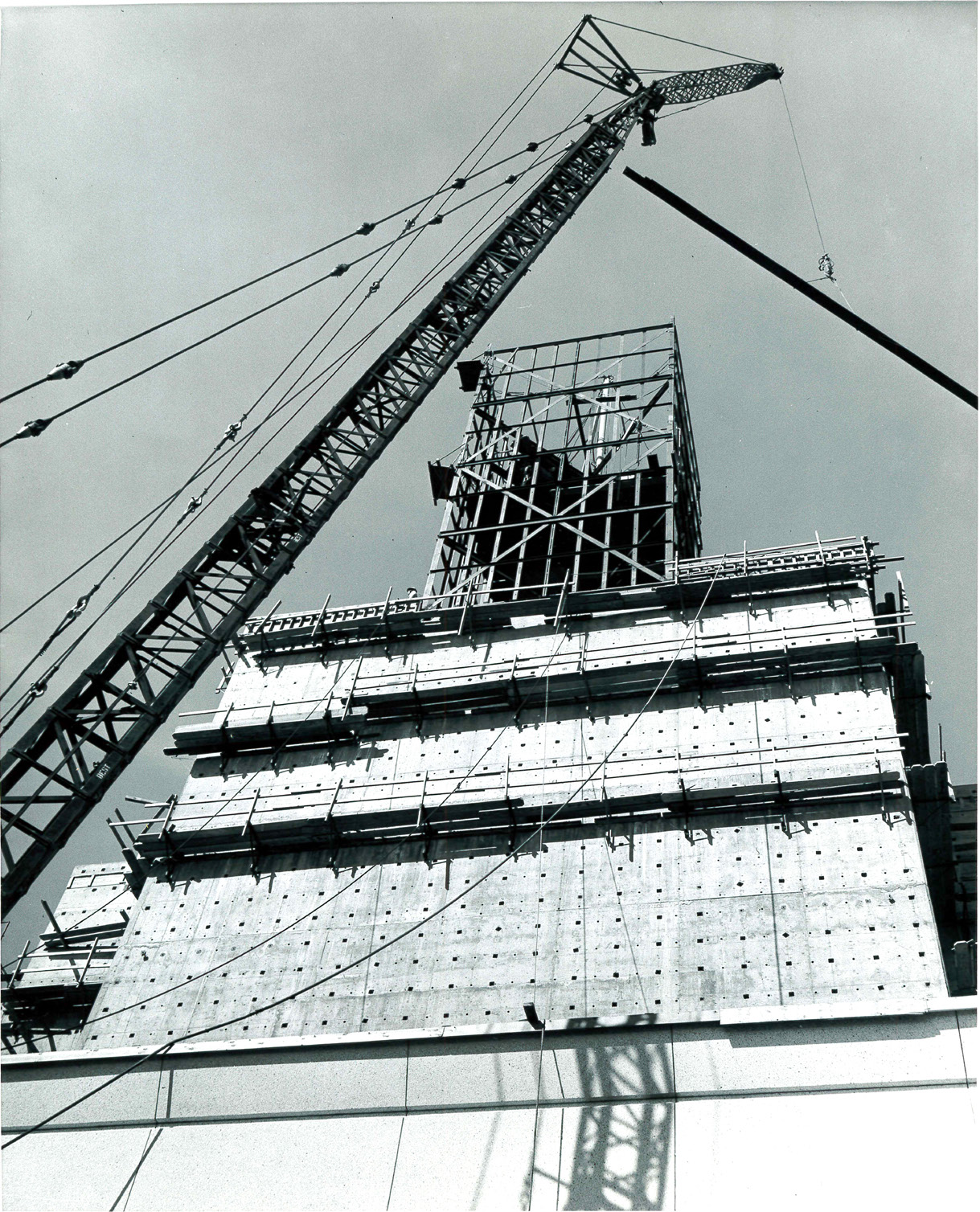

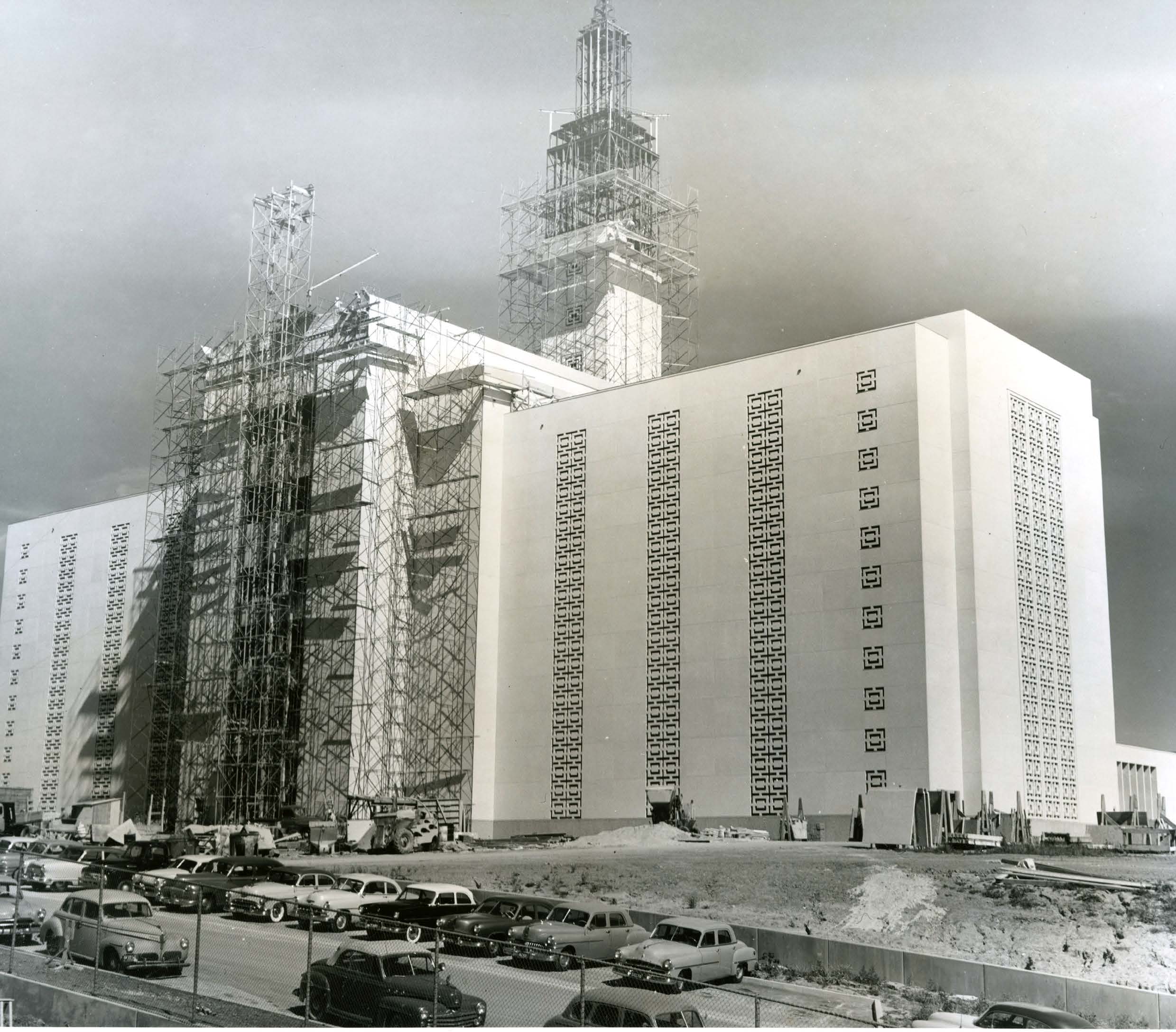

Beginning in the summer of 1953, as the temple’s concrete exterior walls were climbing skyward, they were covered with a beautiful veneer. The foundation walls were covered with Rockville granite from Cold Spring, Minnesota. These slabs were 2½ inches thick and light gray in color. Above this level, the huge building was faced with some 2,500 perfectly matched Mo-Sai panels of white Portland cement and crushed quartz stone, quarried in Utah and Nevada. Most panels measured about 7 by 8 feet, also were 2½ inches thick, and weighed 1,600 pounds. They were firmly attached to the cement walls with bolts and grout. Small square holes to receive the bolts and grout formed a conspicuous grid on the building’s exterior.

Forms going up for the basement walls, November 6, 1952. (Paul L.

Forms going up for the basement walls, November 6, 1952. (Paul L.

Garns)

Concrete being delivered, November 6, 1952. (Paul L. Garns)

Concrete being delivered, November 6, 1952. (Paul L. Garns)

One observer humorously suggested that they could be gun ports through which defenders would shoot to protect the temple. A thin space was left between the panels to allow for expansion; these spaces were then filled or “pointed” with a special plastic filler that would never harden. These panels covered over 146,000 square feet, more than the area of three football fields. This work was done by the masonry crew headed by Stanley C. Child. The panels were etched with acid in such a way that the stone crystals in them sparkled in the light, day or night. This surface was also self-cleaning.

The Buehner brothers of Salt Lake City received the contract to provide the exterior stone, which they regarded as a fulfillment of their father’s prophetic patriarchal blessing decades before that his family would “help erect temples of this Church.”[21] One of the brothers, Carl W. Buehner, a counselor in the Presiding Bishopric, reported that when the specific material was chosen for the temple’s exterior, “there was just enough to make the stone for this building and the Bureau of Information [Visitors’ Center]—no more, no less.” He added, “Each employee who worked on this project was made to feel he was making stone for a temple of God, and with this thought in his mind, gave his very best.”[22]

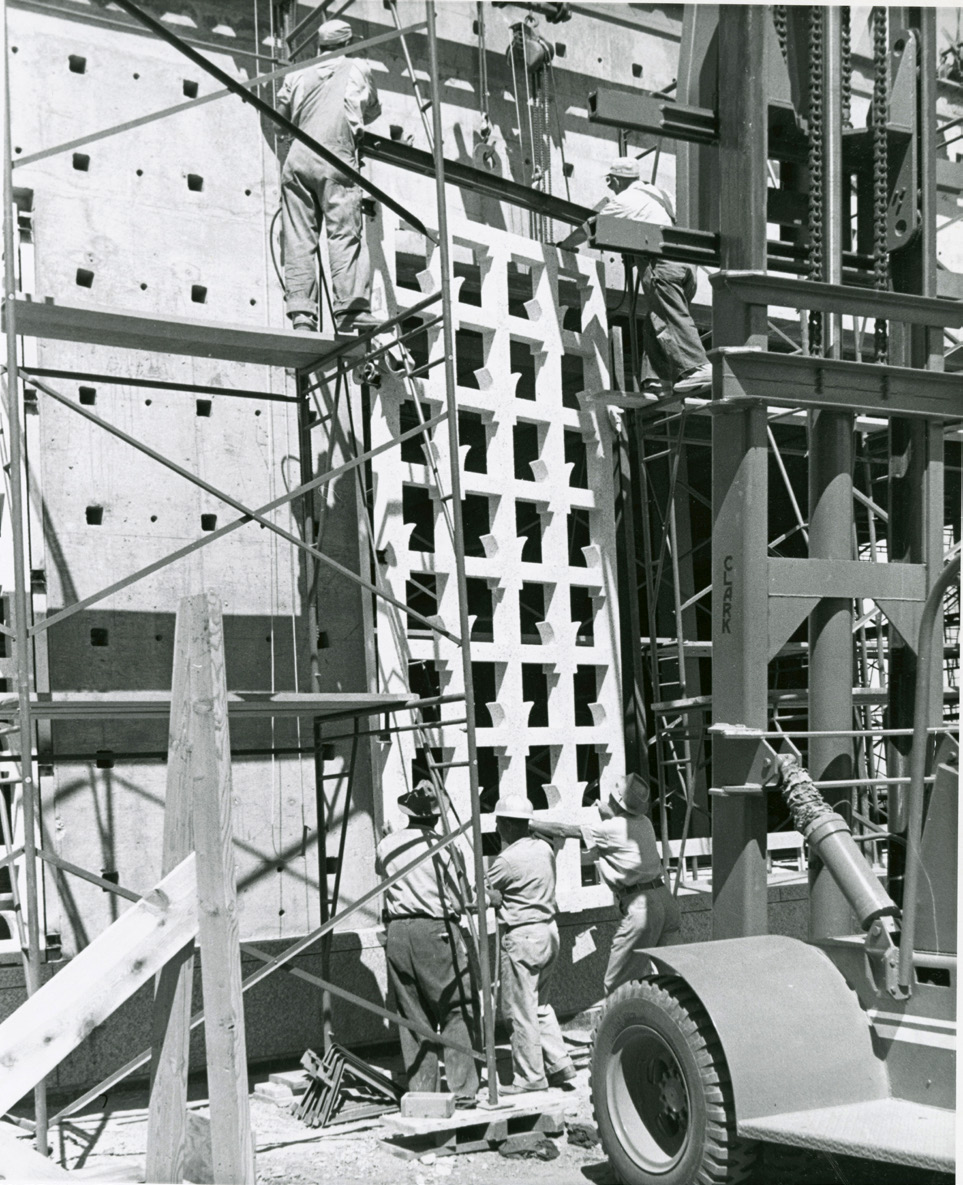

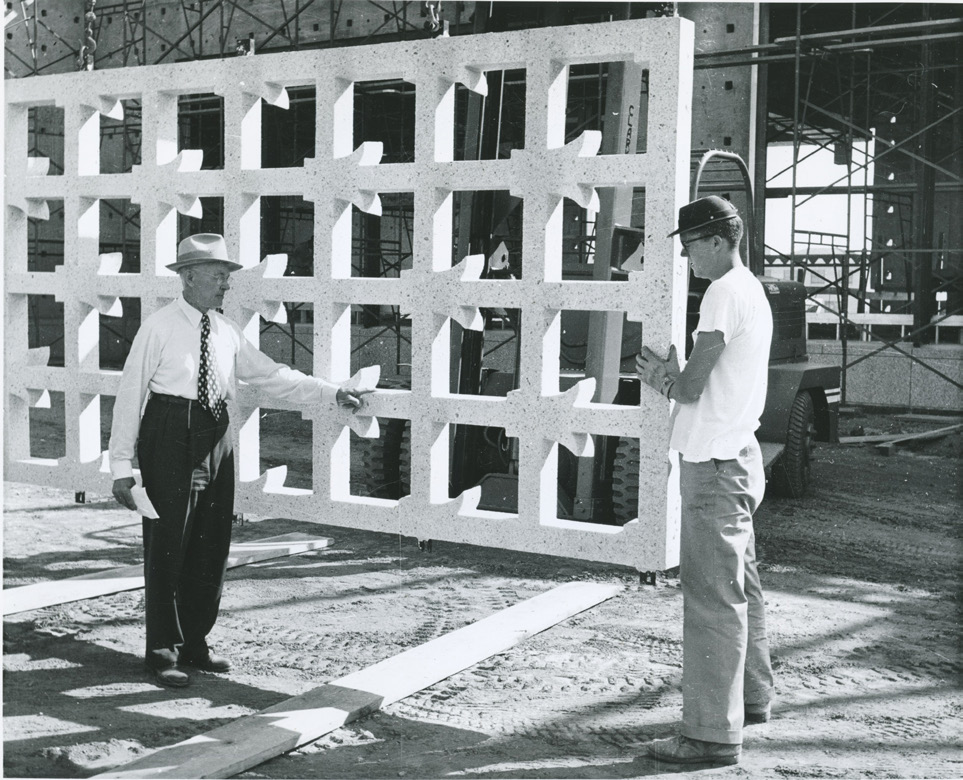

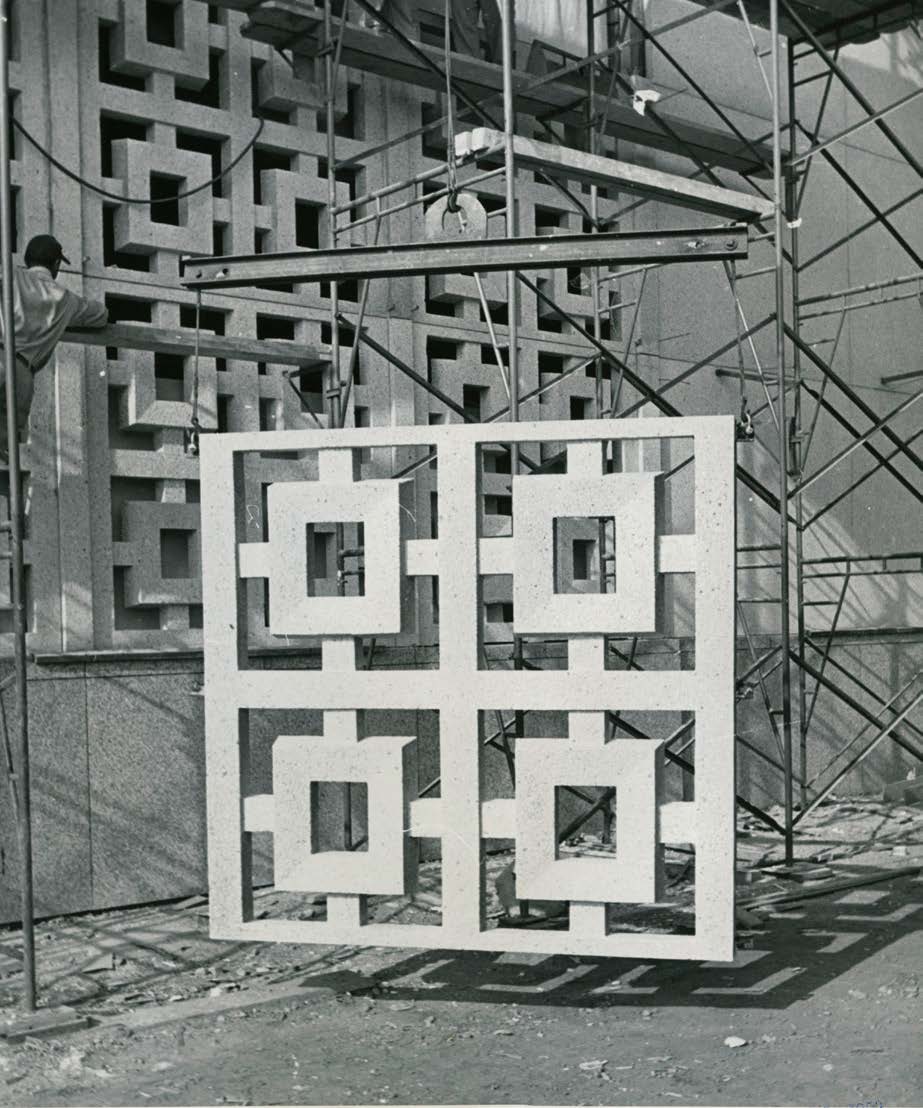

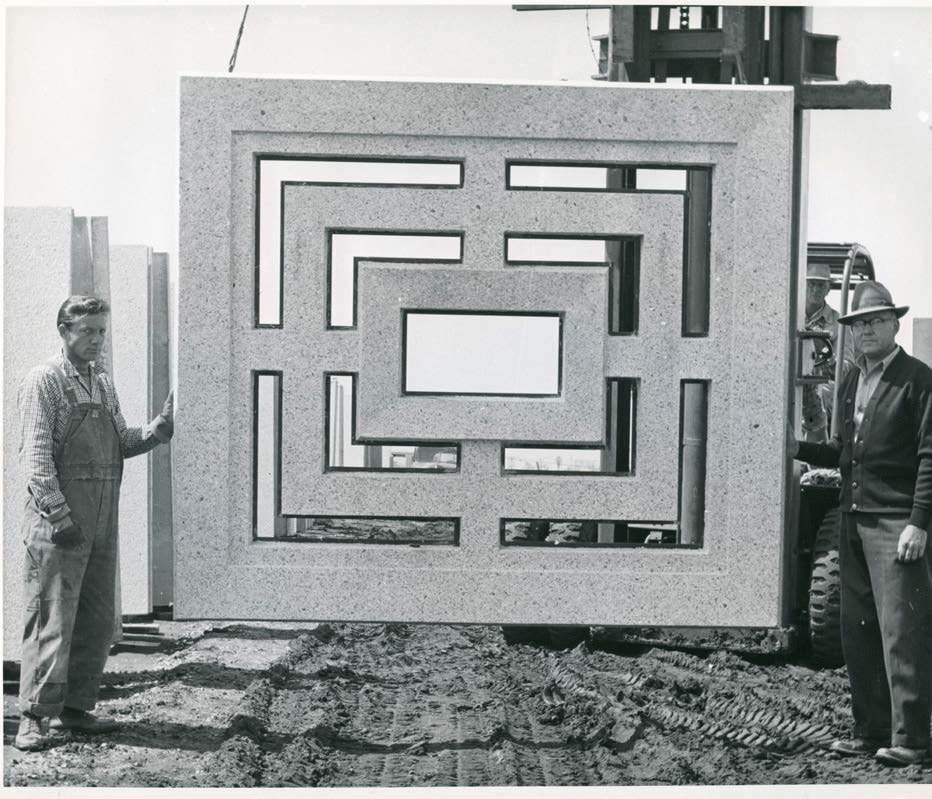

Ornamental stone grills over the windows not only brought “interest and grace” to the temple’s design, but they also would cut down outside sounds and admitted the maximum light while reducing glare from direct sunlight. Three designs were employed. Grills over the ground floor annex windows had a leaf design. Those on the main sides of the temple had a square motif. Grills on the ends of wings employed a shadow-box design.[23] In the main body of the temple, these grills formed tall narrow panels almost the full height of the building. Behind them, dark marble on the walls above and below windows had almost the same appearance from outside as the glass. At night, long fluorescent tubes at the edge of the space between the grills and the window glass would give an even illumination from top to bottom, creating a striking effect.[24]

Basement walls complete, January 2, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

Basement walls complete, January 2, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

December 10, 1952. (Paul L. Garns)

December 10, 1952. (Paul L. Garns)

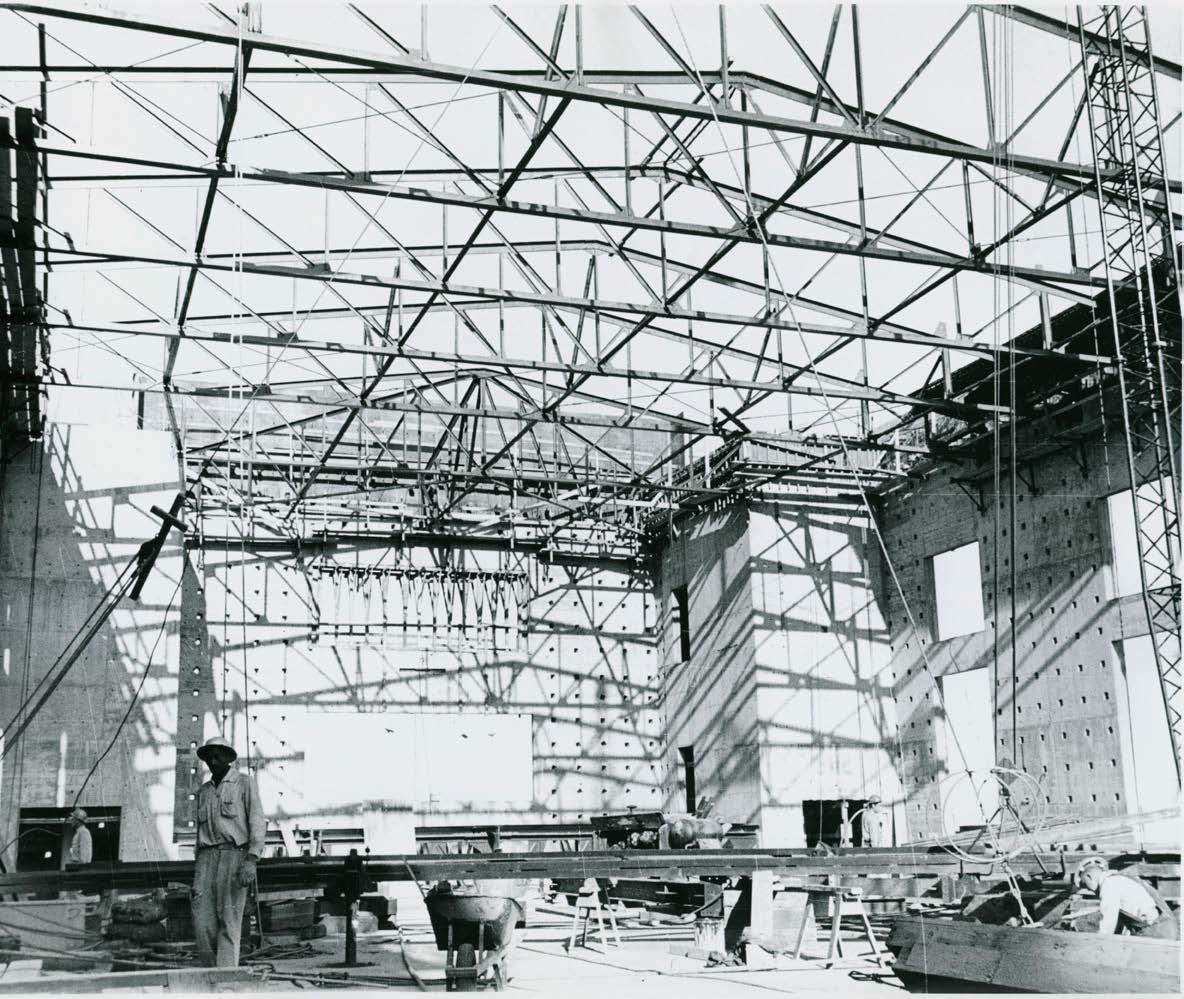

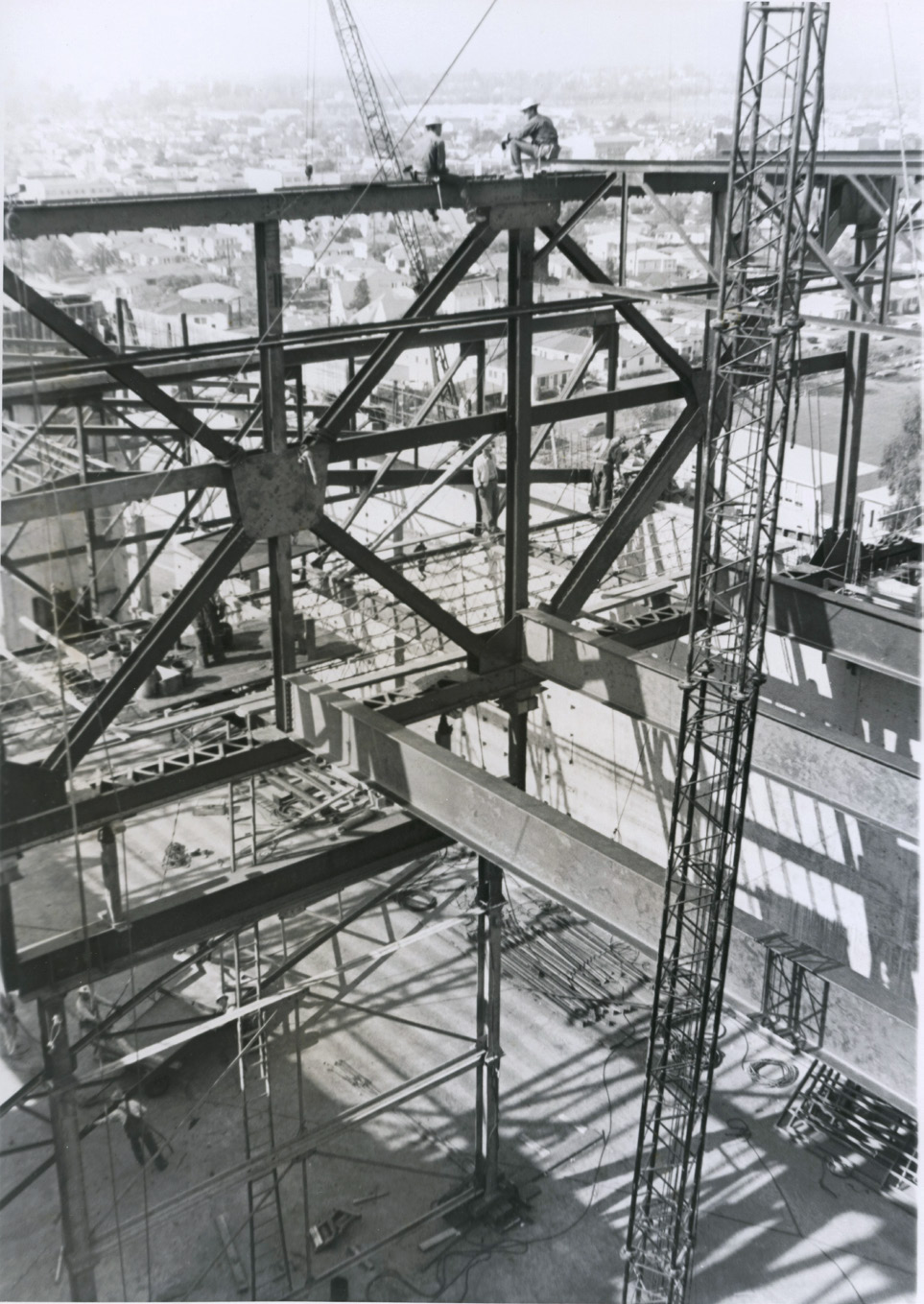

In August 1953 construction passed its one-year mark. By this time, the third-story slab had been poured, a three-day project; this would be the floor of the large priesthood assembly hall. As the building’s height increased, getting construction materials such as concrete, lumber, or steel to where they were needed became a growing challenge. A steel tower enclosing a “skip load” elevator was set up against the back wall of the temple. Its height could be extended as needed. By the time the temple was completed, 90,258 sacks of cement were used, and 15,043 cubic yards of concrete were poured.

As construction progressed, both Edward Anderson and Soren Jacobsen gratefully reported that several subcontractors and many other suppliers “have been more than generous” and have “saved us much in the way of material and expenses with their knowledge and assistance.”[25] By early December 1953, the third-floor walls were up, and the roof was being poured. Hence the exterior of the temple’s main body appeared to be complete. Only the small fourth floor section in the center needed to be added. Rebar for its walls was already in place. At this point, the temple was ready for a significant event, the ceremonial placing of the cornerstone.

The base for the baptismal font, March 1, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

The base for the baptismal font, March 1, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

(Bottom left) Workmen gather at the Lloyd home. (Paul L. Garns)

(Bottom left) Workmen gather at the Lloyd home. (Paul L. Garns)

Workmen in front of the main temple entrance, November 22, 1953. (Paul L. Garns)

Workmen in front of the main temple entrance, November 22, 1953. (Paul L. Garns)

March 4, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

March 4, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

Cornerstone Laying

Temple cornerstones are reminders of Paul’s description of the Church as “built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Jesus Christ himself being the chief cornerstone” (Ephesians 2:20). In the nineteenth century, when temples were built of large hewn stones, the placing of the cornerstone marked the beginning of construction, as with the Kirtland, Nauvoo, and Salt Lake Temples. When reinforced concrete became the norm during the twentieth century, a cornerstone-laying ceremony was purely symbolic and conducted at some point after the walls were at least partially completed. This was the case with the Los Angeles Temple. In the early 1980s, however, the cornerstone laying would become part of the dedication proceedings after the temple was finished. Hence, over the years, the placing of cornerstones shifted from the beginning to the completion of construction.

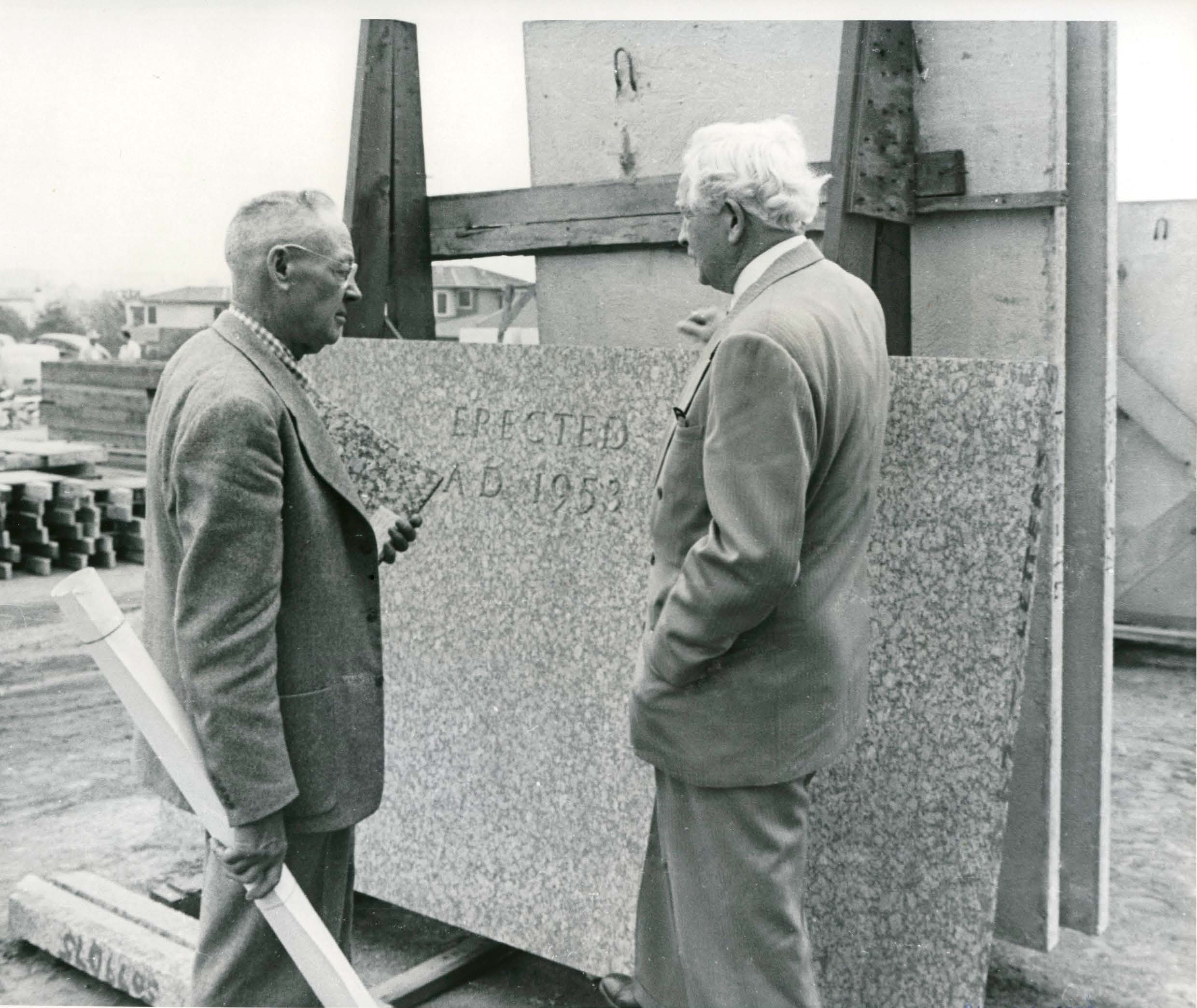

The original plan was to place the Los Angeles Temple’s cornerstone on about January 20, 1954. However, when President McKay visited the temple site the previous October, he inspected the cornerstone plaque and noticed that already carved into it was “Erected 1953.” Therefore the ceremony was shifted one month earlier to December 11, 1953.[26]

The southeast cafeteria wing, March 5, 1953. (Paul L. Garns)

The southeast cafeteria wing, March 5, 1953. (Paul L. Garns)

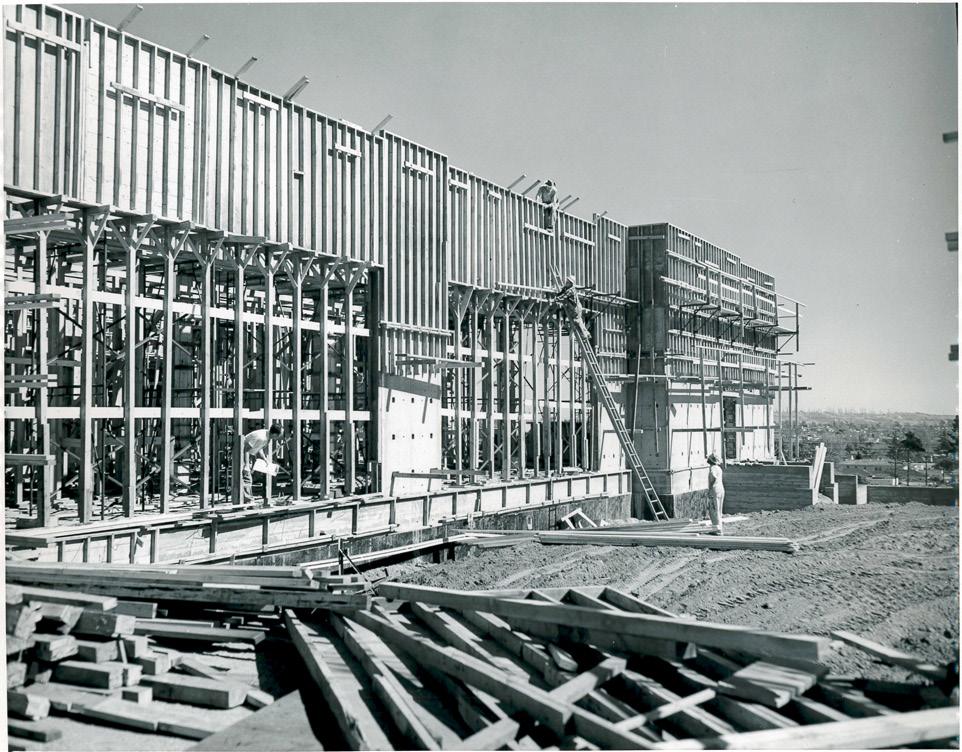

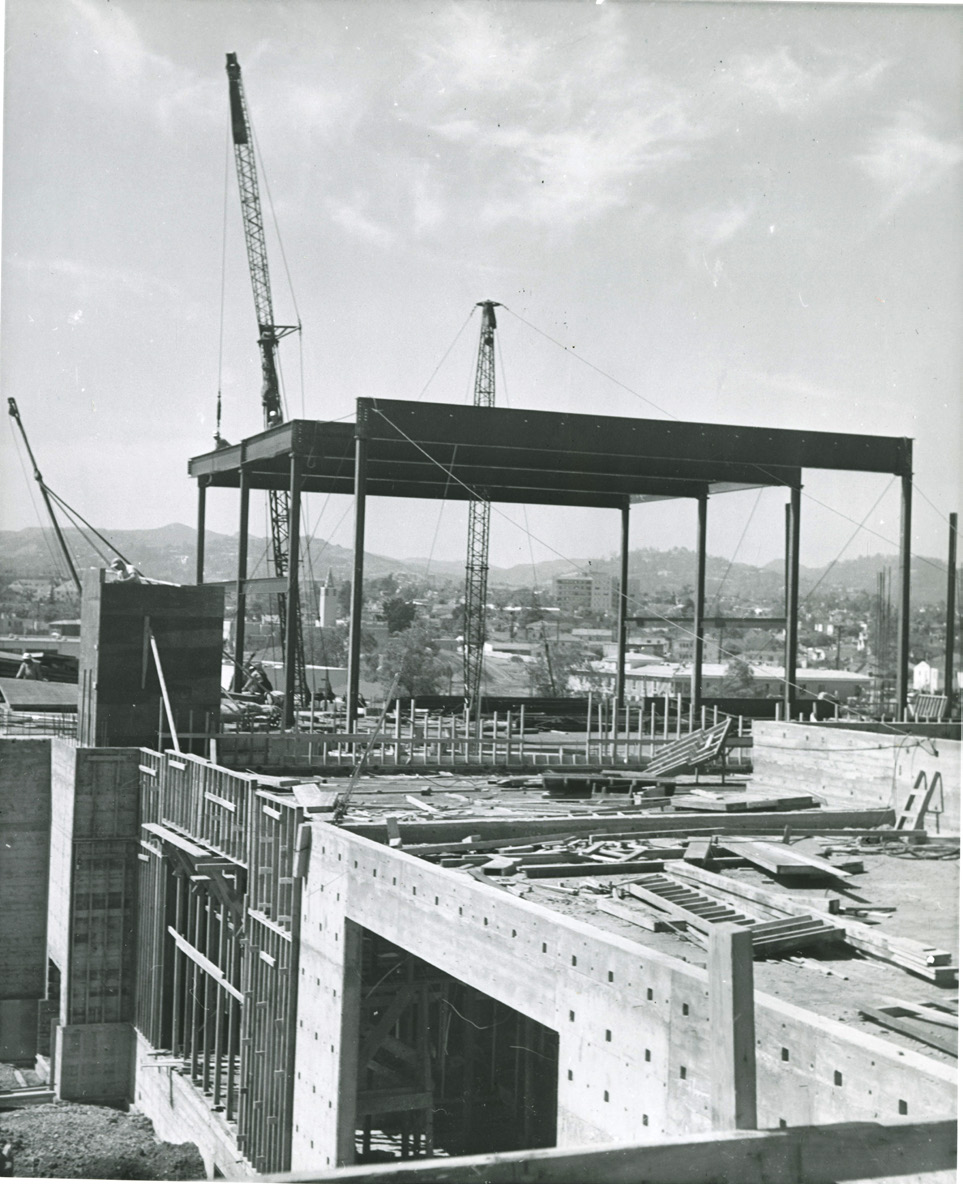

The support columns being formed. (Howard Winn, CHL)

The support columns being formed. (Howard Winn, CHL)

A party of sixty-seven persons, including most of the General Authorities, boarded Union Pacific’s “Los Angeles Limited” for the overnight trip to Southern California. “Only on a few other occasions,” observed the Church News editor, “have all the General Authorities made such an exodus from the city.”[27] They were met at the Los Angeles Union Station downtown by local Saints in sixteen automobiles to take them directly to the temple site about twelve miles away. Two motorcycle policemen escorted the group; the lead officer was Albert J. Aardema, who happened to be bishop of the nearby Elysian Park Ward.[28] Before the ceremony, the visitors from Salt Lake were treated to lunch in the outdoor patio of the newly completed mission home next to the temple.

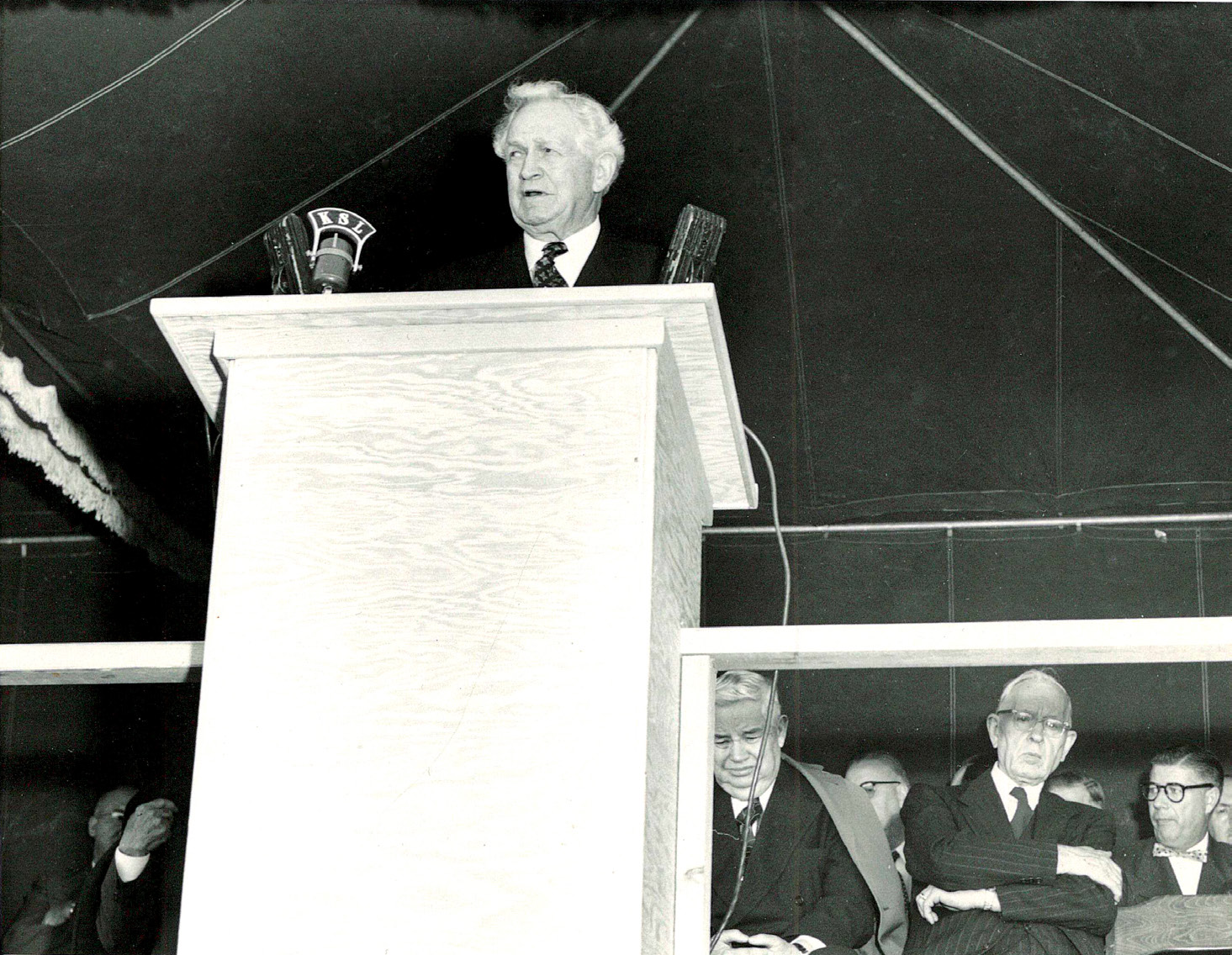

Some ten thousand people, the largest gathering of Latter-day Saints in California to that date, filled the grounds east of the partially completed temple. Countless others listened by radio or watched by television as the proceedings were broadcast both in Los Angeles and Salt Lake City.

President David O. McKay conducted the session, which commenced at 1:30 p.m., and he read congratulatory messages from several government leaders. Mayor Norris Poulson of Los Angeles declared: “This magnificent new Latter-day Saint edifice will stand as a monument to the industry, vision, and sacrifice of a persevering people. Congratulations, and may the wisdom of the Almighty be with you always.” The City Council believed that “this Temple will be a mecca to faithful Latter-day Saints the world over and a point of interest to thousands of visitors who come to Southern California annually” and commended “the architectural excellency and beauty of the edifice,” which would “add dignity to the city of Los Angeles.” The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors presented a formal resolution congratulating the Church, which “is well known and highly respected for its good work of charity and for the many fine contributions to our American way of life” and affirmed that the temple would be “both a landmark and a great asset to the County of Los Angeles, and the entire Southern California Region.”[29]

Music was provided by the recently organized Mormon Choir of Southern California, led by H. Frederick Davis, a native of Tonga who had significant music experience in New York and Salt Lake City before coming to Los Angeles in 1950. He had been invited to organize a three-hundred-voice Latter-day Saint choir for special events in the famed Hollywood Bowl in 1951 and 1952. Following these successful experiences, the choir was organized on a permanent basis.[30] On September 17, 1953, under the direction of the First Presidency, stake president Howard W. Hunter set apart the choir’s officers and conductor.[31] At the cornerstone laying, the group sang “Battle Hymn of the Republic” and “The Spirit of God.”

April 24, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

April 24, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

The entry foyer wall, April 25, 1953. (Howard Winn, CHL)

The entry foyer wall, April 25, 1953. (Howard Winn, CHL)

May 21, 1953. (Howard Winn, CHL)

May 21, 1953. (Howard Winn, CHL)

The first speaker was President Noble Waite, chairman of the temple-building committee who was invited to represent the stake presidents in the temple district. He expressed appreciation to Elders Harold B. Lee and Adam S. Bennion of the Quorum of the Twelve, who had planned the day’s events, and to the local leaders, who had handled the considerable logistics of transportation of visitors from Church headquarters, parking, and the seating of the vast audience. He assured the First Presidency that the Saints would honor their pledge to contribute $1,648,000 before the temple’s dedication.

President McKay’s second counselor, J. Reuben Clark Jr., then gave the main address. He commenced by noting that this was not only the largest temple built during this dispensation, but, he affirmed, “this is the largest temple erected for the purposes for which this temple has been erected, in the entire Christian era.” He cited the Savior’s teachings on the necessity of baptism and also spoke of the sealing ordinance that unites families for eternity. He noted that in this temple the faithful can perform these rites vicariously for those who had died without the blessings of the gospel of Jesus Christ. “There can be no greater blessing come to any man,” President Clark concluded, “than the blessing of trying to save his fellowmen, than the blessing which comes from unselfishness.”

Stephen L Richards, First Counselor in the First Presidency, then placed the metal box, which had been contributed by the Kennecott Copper Company, into the space left in the foundation near the temple’s southeast corner. The box contained copies of the scriptures, newspapers, and other items of significance to the temple’s construction.[32] President Richards formally placed the cornerstone plaque over the opening and then offered a prayer dedicating the cornerstone. He prayed that the temple might be a “powerful missionary force” and that those who come “to admire the symmetry and beauty of this structure may more deeply and fully appreciate its meaning and significance.” He also petitioned that the Saints’ faithful contributions toward its erection might “bring increased devotion to the principles of the Everlasting Gospel, to the keeping of Thy commandments and to the extension and enlargement of the borders of Zion.”

President McKay closed the service with the hope that “the spirit of this great occasion” may be “an encouragement to the architects, the contractor, the workmen, the artists who will continue their labors until the Temple shall have been completed.”

The joy of this occasion was marred two days later when it was learned that Matthew Cowley of the Quorum of the Twelve had died unexpectedly in his Los Angeles hotel room early Sunday morning, December 13. Elder Cowley, who had a known heart condition, died at the age of 56. He was noted for his remarkable spiritual experiences during service among the Polynesian people of the South Pacific.

Looking toward the Santa Monica Hills, April 9, 1953. (Paul L. Garns)

Looking toward the Santa Monica Hills, April 9, 1953. (Paul L. Garns)

The base for the grand staircase, April 9, 1953. (Paul L. Garns)

The base for the grand staircase, April 9, 1953. (Paul L. Garns)

The grand staircase, May 27, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

The grand staircase, May 27, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

The inscription stone for the main entrance. (Howard Winn)

The inscription stone for the main entrance. (Howard Winn)

May 27, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

May 27, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

Inside the east wing looking toward the west. (Paul L. Garns)

Inside the east wing looking toward the west. (Paul L. Garns)

The upper section of the second floor walls being formed, June 4, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

The upper section of the second floor walls being formed, June 4, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

Soren Jacobsen supervises the installation of granite veneer (note the square holes in the concrete walls to receive bolts anchoring Mo-Sai panels). (Howard Winn)

Soren Jacobsen supervises the installation of granite veneer (note the square holes in the concrete walls to receive bolts anchoring Mo-Sai panels). (Howard Winn)

Author Richard Cowan witnessing the installation of the first grill panel. (Edith O. Cowan)

Author Richard Cowan witnessing the installation of the first grill panel. (Edith O. Cowan)

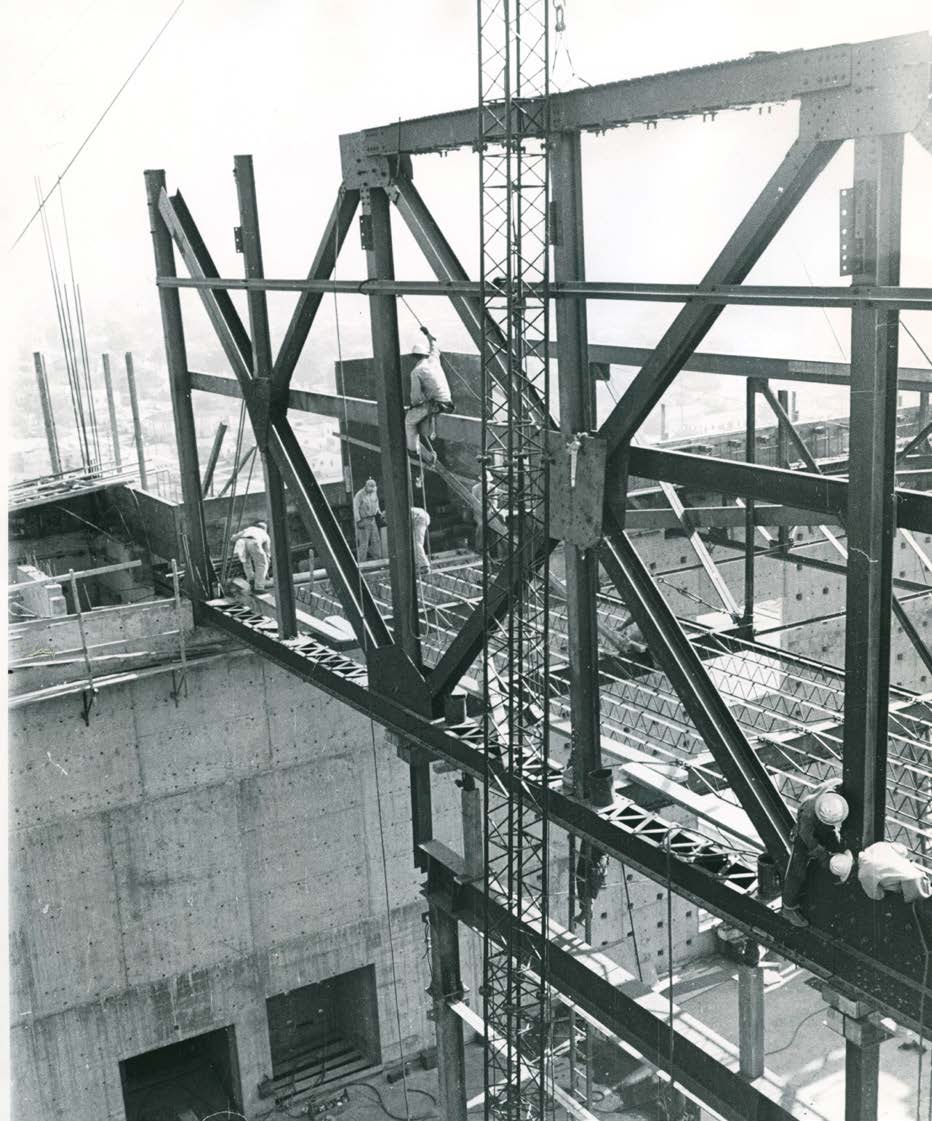

A construction worker balancing on the scaffolding. (Anderson

A construction worker balancing on the scaffolding. (Anderson

Collection, CHL)

The view from above (note the mission home and ward chapel). (Anderson Collection, CHL)

The view from above (note the mission home and ward chapel). (Anderson Collection, CHL)

Mo-Sai anchor holes as seen from inside. (George Bergstrom)

Mo-Sai anchor holes as seen from inside. (George Bergstrom)

Mo-Sai panels being installed, June 4, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

Mo-Sai panels being installed, June 4, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

Mo-Sai panels being delivered to the temple site, October 1953. (George Bergstrom)

Mo-Sai panels being delivered to the temple site, October 1953. (George Bergstrom)

Installing a grill with a forklift. (Howard Winn)

Installing a grill with a forklift. (Howard Winn)

Soren Jacobsen inspecting the decorative grillwork for the annex windows, July 1, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

Soren Jacobsen inspecting the decorative grillwork for the annex windows, July 1, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

Mo-Sai panels ready to be installed, July 8, 1953. (Paul L. Garns)

Mo-Sai panels ready to be installed, July 8, 1953. (Paul L. Garns)

A man welds a decorative grill in place. (Howard Winn)

A man welds a decorative grill in place. (Howard Winn)

The cafeteria walls completed. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

The cafeteria walls completed. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

The pulley system for lifting exterior panels, August 4, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

The pulley system for lifting exterior panels, August 4, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

The square motif design, October 1, 1953. (Howard Winn)

The square motif design, October 1, 1953. (Howard Winn)

Soren Jacobsen aiding with the installation of marble veneer. (Winn)

Soren Jacobsen aiding with the installation of marble veneer. (Winn)

September 1, 1953. (Paul L. Garns)

September 1, 1953. (Paul L. Garns)

A shadow box grill. (Winn)

A shadow box grill. (Winn)

The third-floor second wall section being constructed. (Paul L. Garns)

The third-floor second wall section being constructed. (Paul L. Garns)

October 1, 1953. (Winn)

October 1, 1953. (Winn)

The vibrator used to remove air bubbles from the concrete. (Winn)

The vibrator used to remove air bubbles from the concrete. (Winn)

The steel structure for the fourth floor, November 4, 1953.

The steel structure for the fourth floor, November 4, 1953.

Finishing the concrete top of the third floor, September 1, 1953. (Garns)

Finishing the concrete top of the third floor, September 1, 1953. (Garns)

A makeshift drinking fountain on the third floor, September 1, 1953.

A makeshift drinking fountain on the third floor, September 1, 1953.

The third-floor roof construction, October 1, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

The third-floor roof construction, October 1, 1953. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

Looking toward Santa Monica Boulevard, September 1, 1953.

Looking toward Santa Monica Boulevard, September 1, 1953.

Workers waiting for the next beam to arrive, November 6, 1953.

Workers waiting for the next beam to arrive, November 6, 1953.

Pouring and leveling concrete on the third-floor roof. (Winn)

Pouring and leveling concrete on the third-floor roof. (Winn)

President David O. McKay and Soren Jacobsen reviewing patterns, October 10, 1953. (Howard Winn)

President David O. McKay and Soren Jacobsen reviewing patterns, October 10, 1953. (Howard Winn)

Soren Jacobsen and David O. McKay inspecting the cornerstone plaque. (Howard Winn)

Soren Jacobsen and David O. McKay inspecting the cornerstone plaque. (Howard Winn)

Large crowds at the cornerstone ceremony. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

Large crowds at the cornerstone ceremony. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

On the way to the Los Angeles cornerstone ceremony.

On the way to the Los Angeles cornerstone ceremony.

The Mormon Choir of Southern California. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

The Mormon Choir of Southern California. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

President David O. McKay at the cornerstone ceremony (Paul L. Garns)

President David O. McKay at the cornerstone ceremony (Paul L. Garns)

President J. Reuben Clark giving the main address. (Paul L. Garns)

President J. Reuben Clark giving the main address. (Paul L. Garns)

Closing the cornerstone box, directed by Stephen L Richards. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

Closing the cornerstone box, directed by Stephen L Richards. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

Placing the cornerstone box. (Scrapbook)

Placing the cornerstone box. (Scrapbook)

Remarks at the cornerstone laying. (Paul L. Garns)

Remarks at the cornerstone laying. (Paul L. Garns)

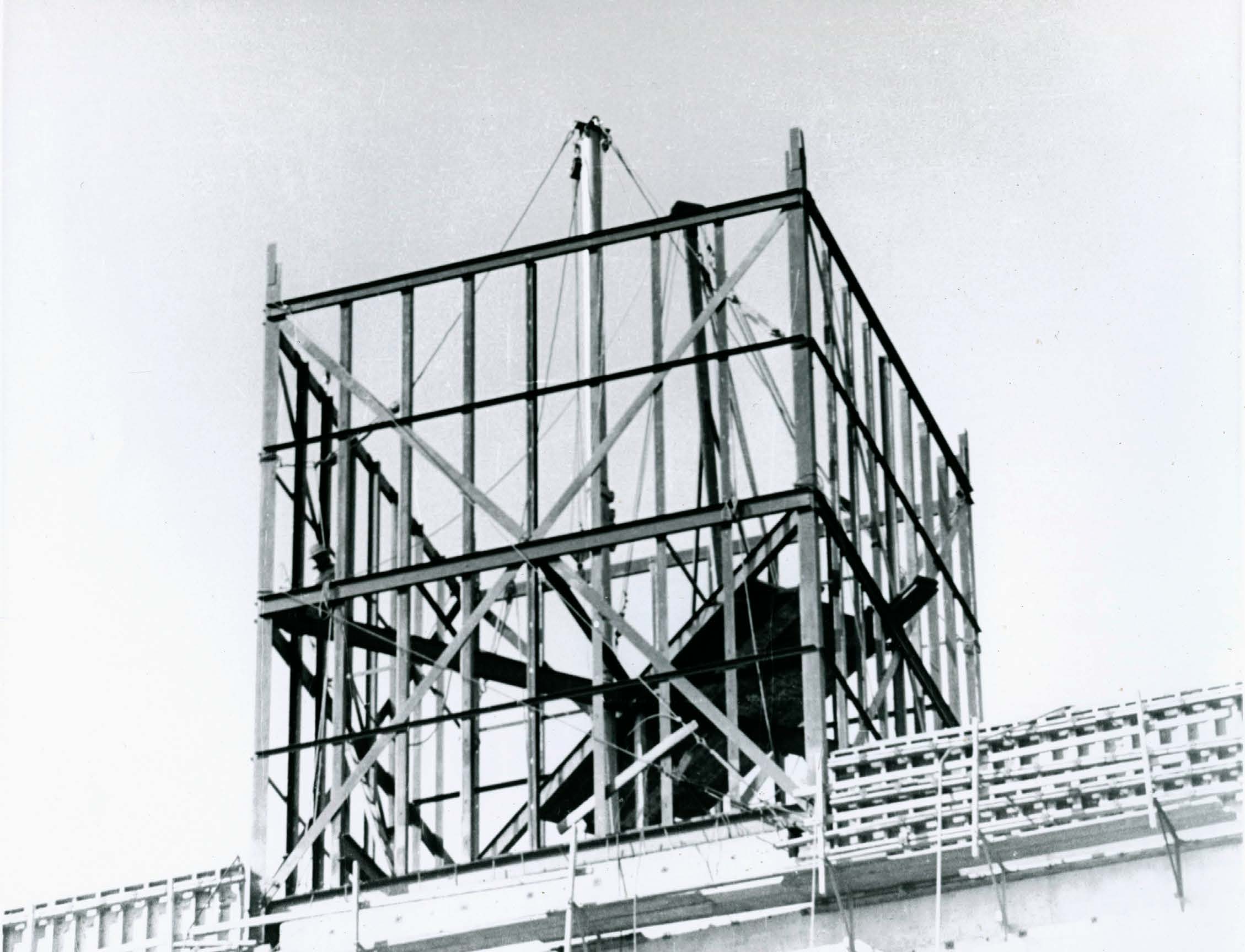

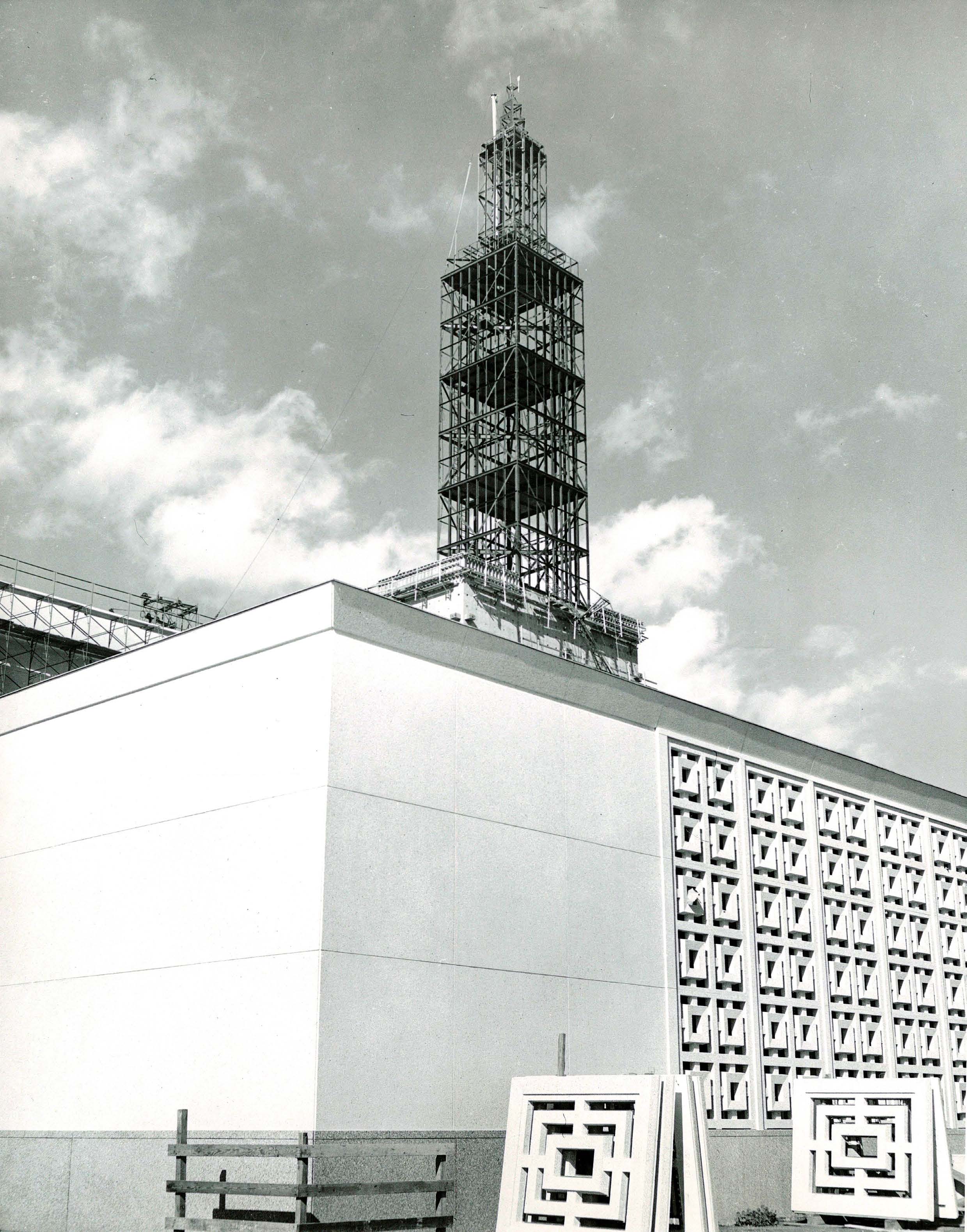

Early tower construction, January 5, 1954. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

Early tower construction, January 5, 1954. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

The tower in construction.

The tower in construction.

(Paul L. Garns)

Statue of the Angel Moroni atop the Temple’s Tower

“Topping out,” February 12, 1954.

“Topping out,” February 12, 1954.

(Anderson Collection, CHL)

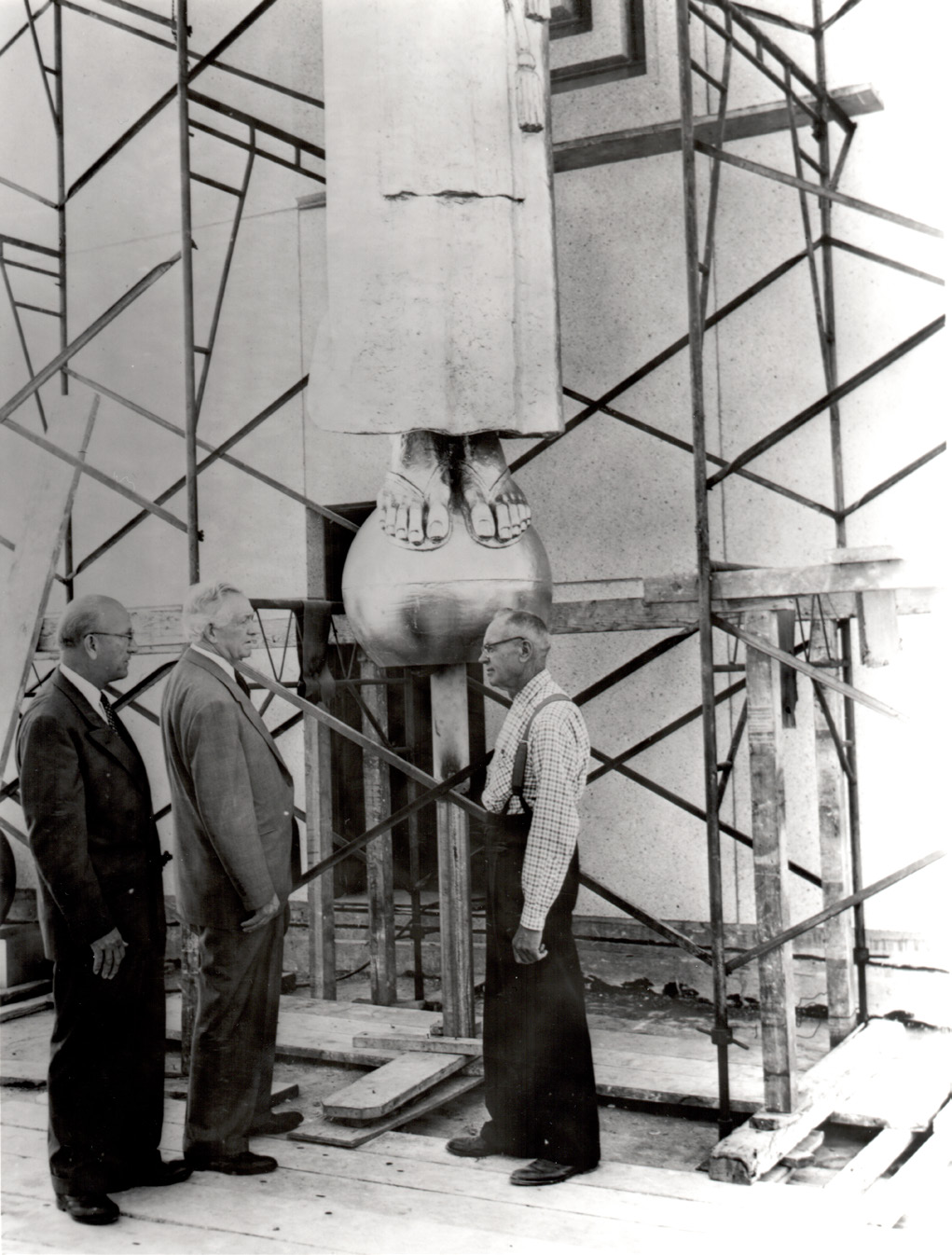

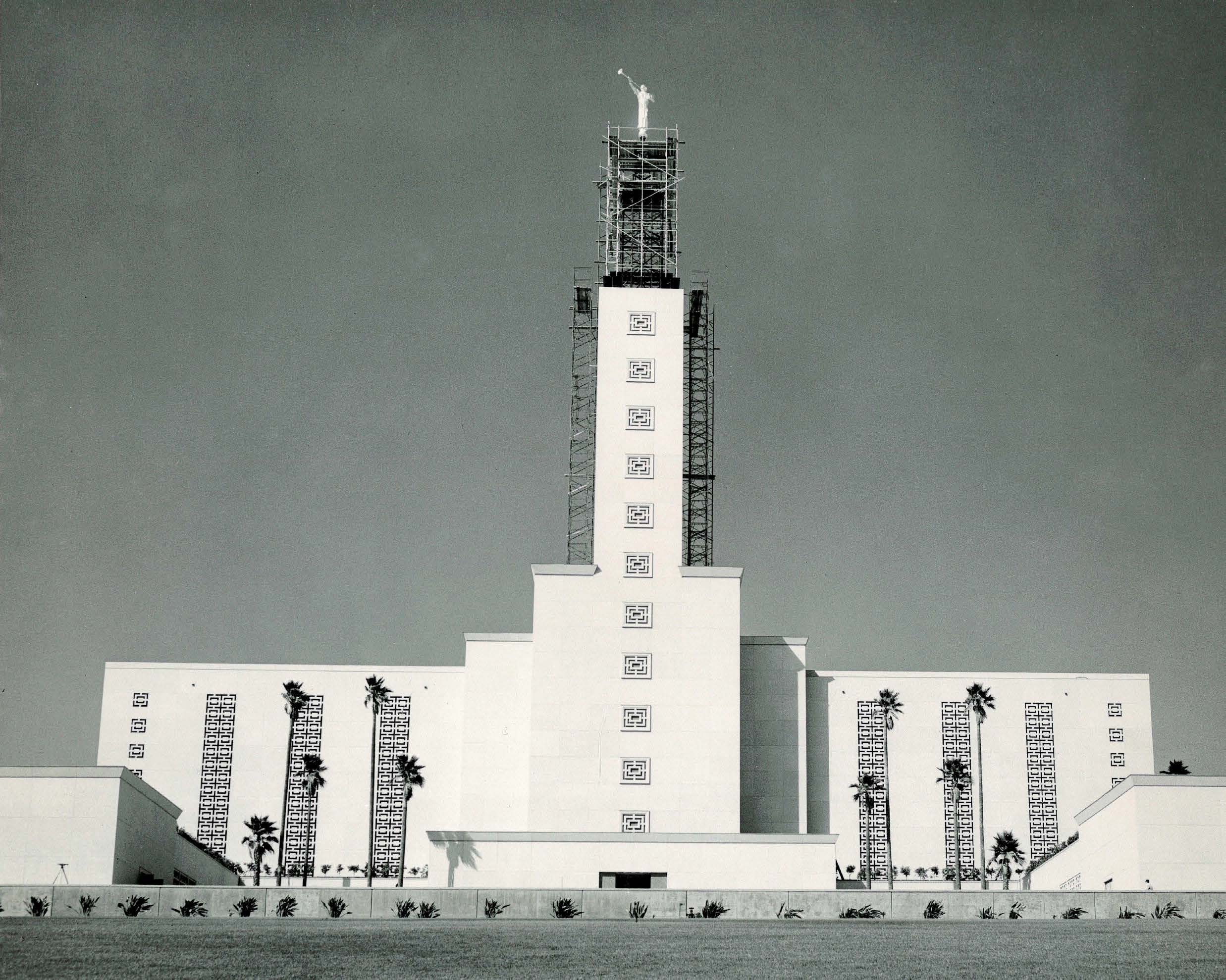

During the early months of 1954, the most noticeable new feature of the temple was its growing tower. It would rise to a height of 135 feet above the temple’s roof. Its structure was entirely of steel, no concrete being used. Sections of the steel framework were fabricated on the ground and then lifted by a huge crane to the roof of the fourth floor. A separate boom then raised them into place on the tower. The uppermost section was fastened into place on February 12, thus constituting what steelworkers refer to as “topping out.” Mo-Sai stone panels, matching those covering the body of the building, were bolted directly to this steel framework. The tower has no rooms but did provide an inside utility ladder.[33]

By the time construction reached the two-year mark in August 1954, outside work focused on finishing details. The reflecting pool in the temple’s forecourt had just been completed, and the steps to the main front entrance were finished with marble. The walks up the hill from Santa Monica Boulevard were being built, and many others were already in place. Elevators were functioning inside the temple.[34]

The view from Overland Avenue. (Scrapbook)

The view from Overland Avenue. (Scrapbook)

Plans called for the tower to be surmounted by a statue of the angel Moroni, who had told young Joseph Smith about the record that would become the Book of Mormon. Latter-day Saints often associate him with John’s vision of “another angel flying in the midst of heaven, having the everlasting gospel to preach unto them that dwell on the earth” (Revelation 14:6). Thus Elder Thomas S. Monson taught that “the Moroni statue which appears on the top of several of our temples is a reminder to us all that God is concerned for all His people throughout the world, and communicates with them wherever they may be.”[35] Furthermore, because Moroni is specifically associated with the Book of Mormon—whose announced mission is to convince all that Jesus is the Christ—these herald statues remind us of the Savior and the need to prepare for his Second Coming.

Surprisingly, placing these statues atop Latter-day Saint temples was not the usual practice at the time the Los Angeles Temple was built. Ten temples (including Kirtland and Nauvoo) had been built before construction on the Los Angeles Temple commenced. Only the largest, the Salt Lake Temple, was adorned with the familiar statue of the herald angel. The Nauvoo Temple had a weathervane in the form of a prone flying angel atop its tower; this was a common adornment of church steeples at that time, so the Nauvoo angel was not necessarily linked with Moroni. Following Los Angeles, nine more temples would be built during the next quarter century (including the Swiss Temple, which was started after Los Angeles). Only one of these, the Church’s third largest temple, dedicated in 1974 at Washington, D.C., would have the angel. Hence the Los Angeles Temple with its figure of Moroni represented a significant departure from the norm.

Only after 1980 would statues of Moroni become a regular part of Latter-day Saint temples. Three moderately large temples—Seattle Washington, 1980; Jordan River Utah, 1981; and Mexico City Mexico, 1983—were designed with the angel. In 1980 and 1981, the Church announced plans to construct sixteen smaller temples. As a means to achieve desired economy, towers were omitted. As these smaller temples were still in the planning stages, however, their designs were modified to include a spire, and it would be surmounted by a statue of the angel Moroni. Hereafter, the figure of Moroni would adorn virtually all new temples regardless of their size. Following the decision to incorporate the angel Moroni into the design of most temples, the familiar statues were also added to several temples that had earlier been built without them.[36]

Progress as of March 8, 1954. (Paul L. Garns)

Progress as of March 8, 1954. (Paul L. Garns)

The temple entrance,

The temple entrance,

July 15, 1954. (Paul L. Garns)

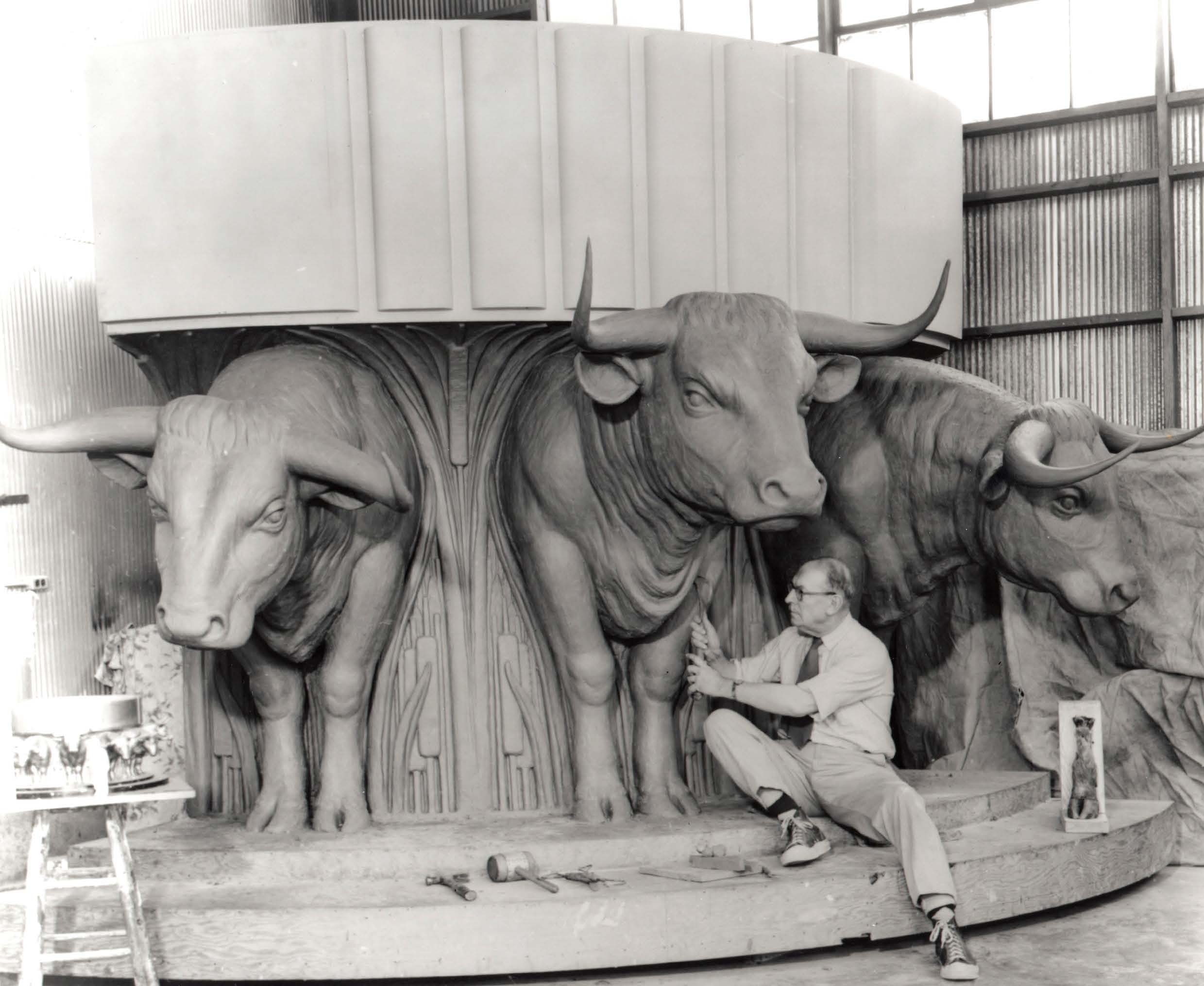

Sculptor Millard F. Malin at work. (Scrapbook)

Sculptor Millard F. Malin at work. (Scrapbook)

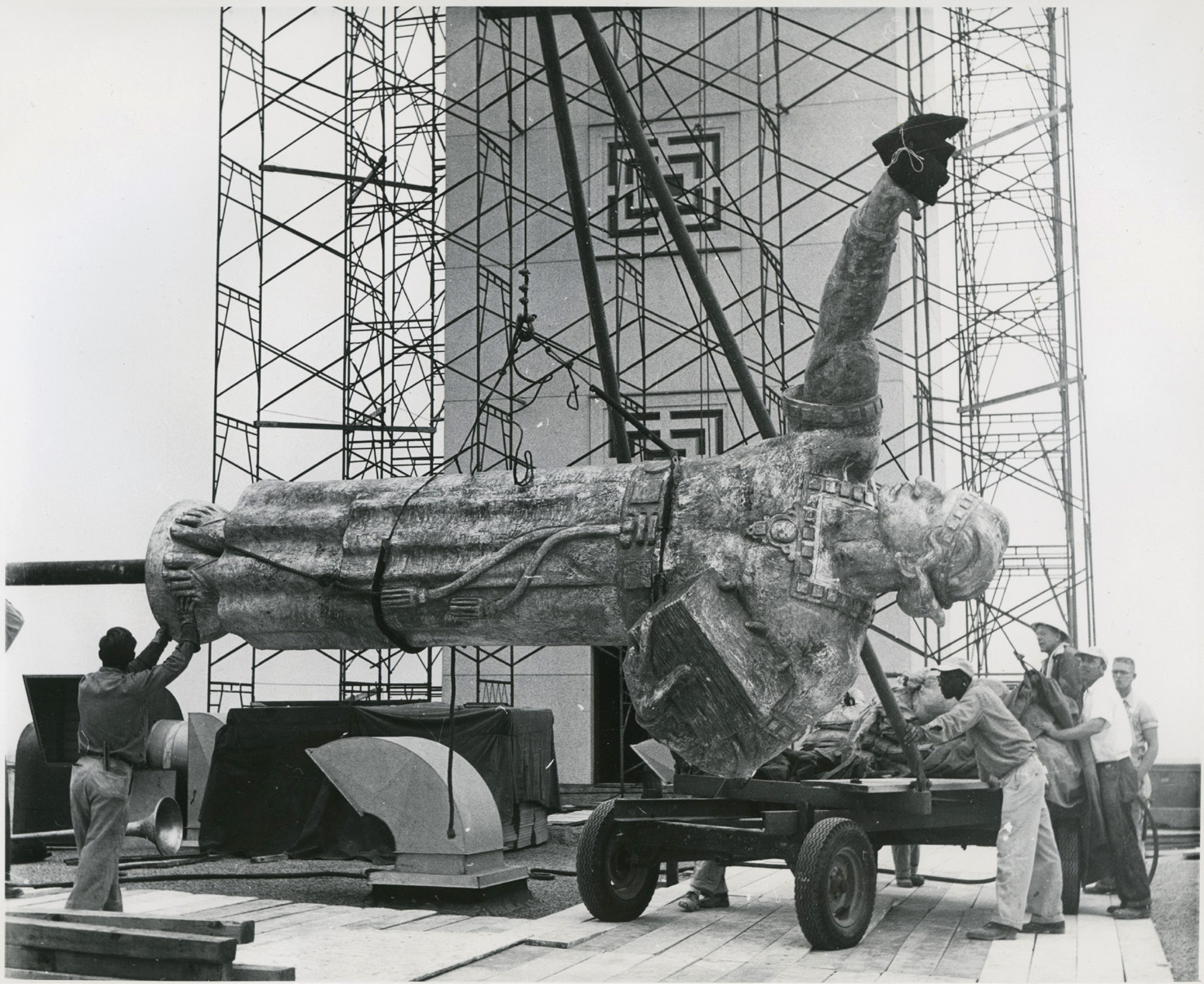

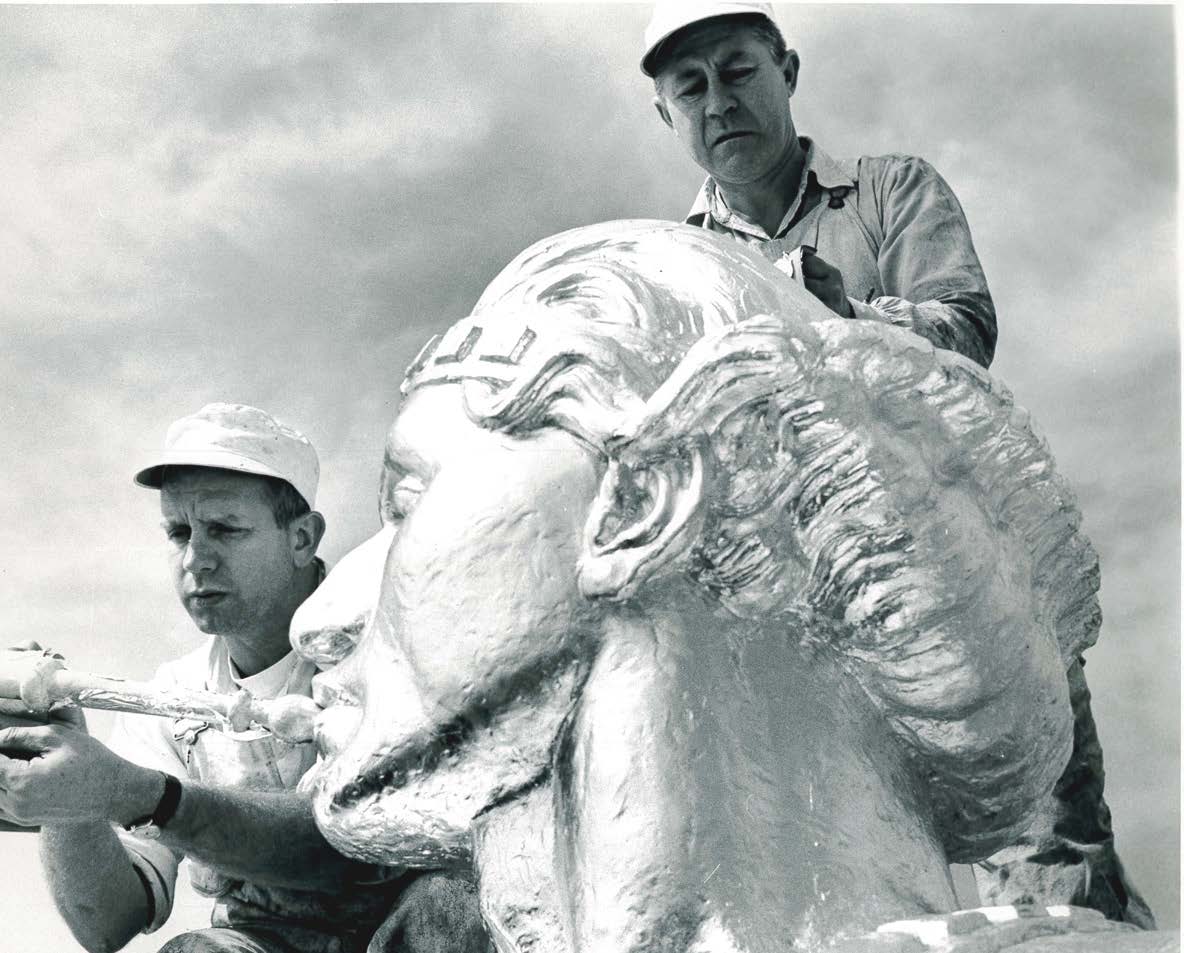

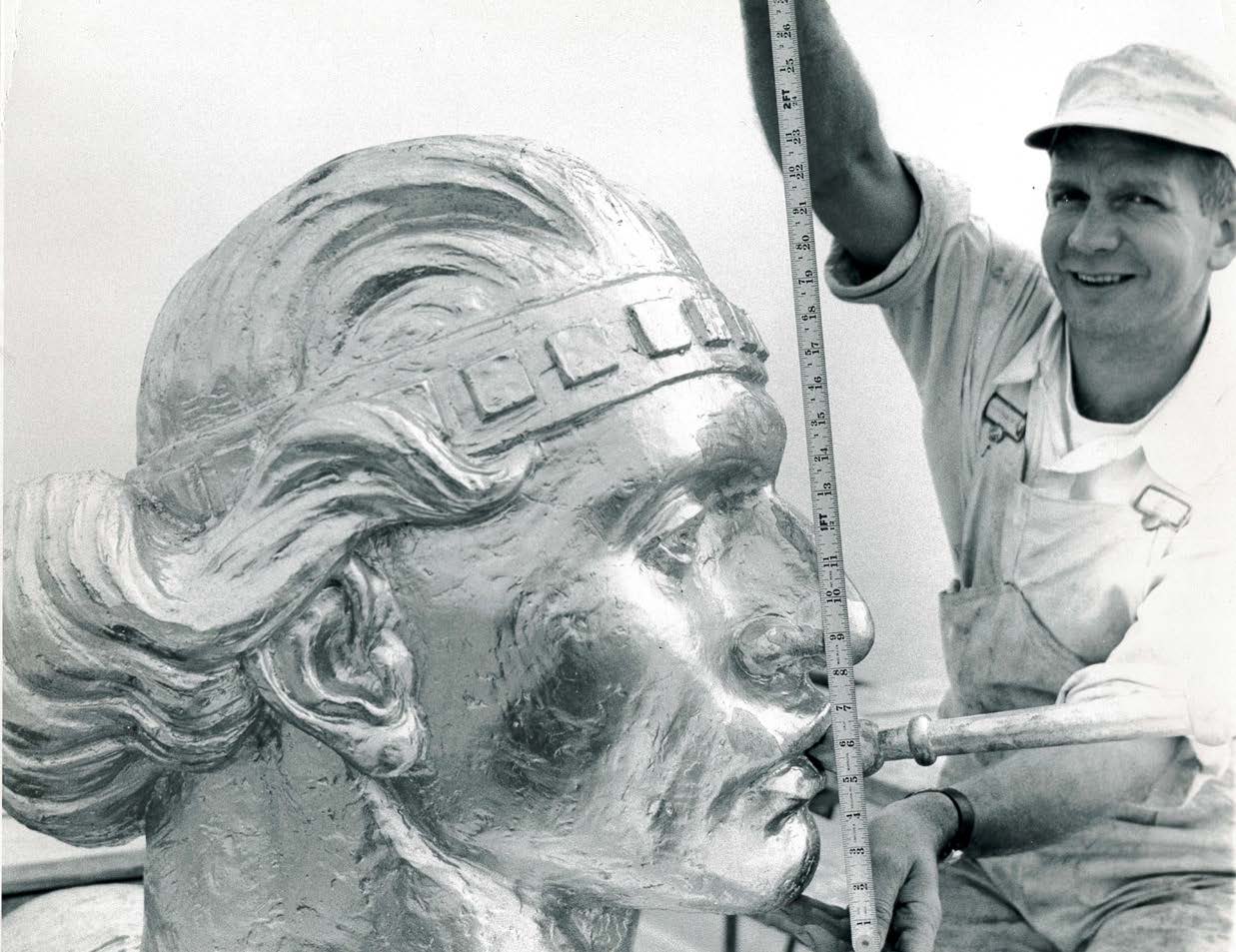

The 15½-foot figure of the angel Moroni, as well as the baptismal font and oxen for the Los Angeles Temple, was sculpted by Millard F. Malin, “a well-known Intermountain sculptor, especially noted for his work in marble.” He studied art and anatomy at the University of Utah before going on to the National Academy and the Beaux Arts Institute in New York City. He learned sculpturing techniques from Gutzon Borglum and Herman A. MacNeil. Malin commenced his work on Moroni by making a small model that was approved by the First Presidency in 1953.

Soren Jacobsen oversees the detail work. (Scrapbook)

Soren Jacobsen oversees the detail work. (Scrapbook)

Working on the reflecting pool, July 19, 1954. (Paul L. Garns)

Working on the reflecting pool, July 19, 1954. (Paul L. Garns)

Originally, President McKay liked everything except for the angel’s face, which he thought looked too feminine; after the sculptor made some adjustments, the President approved.[37] A special studio was then constructed for Malin at the Otto Buehner Cast Stone Company in Salt Lake City—the same firm that produced the Mo-Sai veneer panels for the temple—where he created the full-sized angelic statue and font in clay during the fall of that year. The first step was to construct a strong “armature”—the structural framework or skeleton that would support the two-ton weight of the plastilina soft modeling clay.”

A close study shows that the figure has “Lamanite features and the cloak is of Mayan design and compliments the architecture of the [Los Angeles] Temple.” The angel stands on a ball 33 inches in diameter. His right hand, which includes a lightning rod, raises the 8-foot trumpet, and in his left arm he carries the gold plates from which the Book of Mormon was translated. Malin did not use a living model, but he consulted freely with other artists, particularly with painter Arnold Friberg. He was assisted by Torlief S. Knaphus (who had created the figure of Moroni for the Hill Cumorah monument twenty years earlier), Maurice Brooks, and Elbert Porter.[38]

The back side of the temple, May 4, 1954 (note the skip-load lifting device). (Howard Winn)

The back side of the temple, May 4, 1954 (note the skip-load lifting device). (Howard Winn)

Just before his death, Elder Matthew Cowley visited the Buehner plant to inspect the huge sculpture of the angel. Stories are told about how he placed his stamp of approval by carving his initials in the clay. According to one version, he carved them in the big toenail of the figure’s huge left foot. Another version has him placing “MC” on the lower back of the angel’s robe. Later close-up photographs of the angel, however, do not show any evidence of these initials in either location.[39]

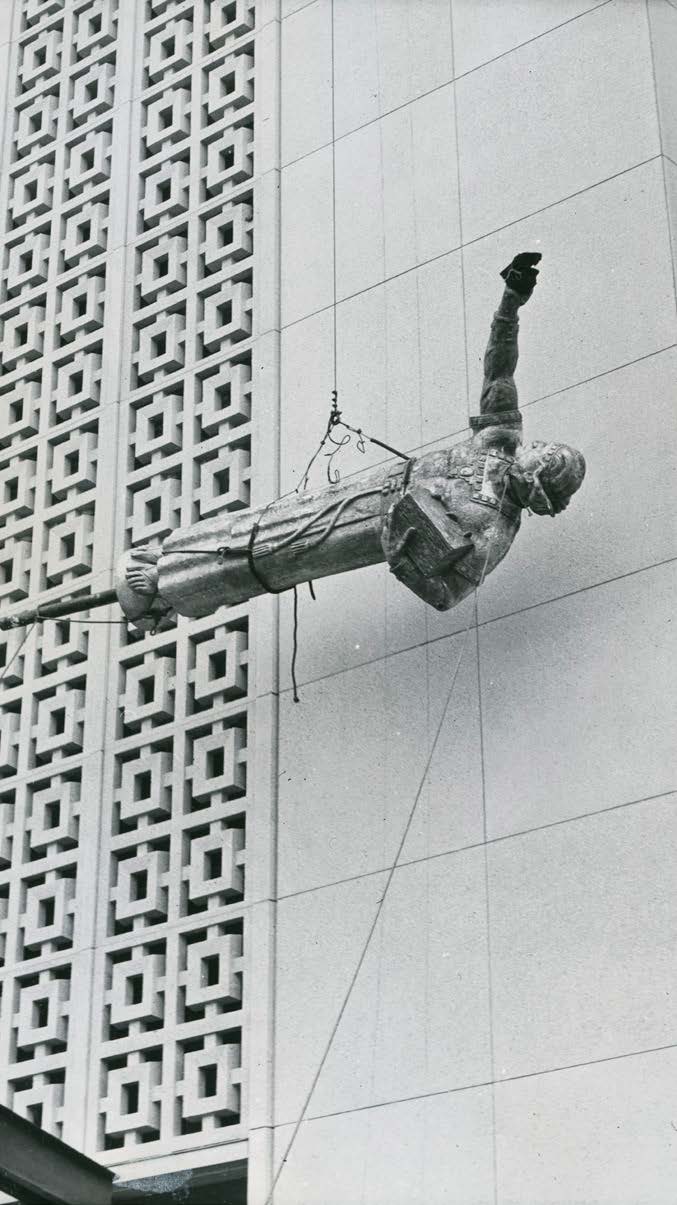

The plaster cast of the clay sculpture was sent to the Roman Bronze Works in Columbia, New York, in five pieces; there they were cast in metal and then welded together. The whole process took three months. It was done in aluminum rather than bronze, because Los Angeles building codes prohibited such a heavy weight being placed so high above the ground. Still, the figure weighed 2,100 pounds, the thickness of the aluminum ranging from 3/

The one-ton statue was trucked across the continent, an eight-day trip. The truck pulled up the hill onto the site and parked behind the temple early in the morning, October 6, 1954, and the angel was found to be in perfect condition. It was immediately hoisted by means of the skip load elevator to the temple’s roof, set upright, and surrounded with scaffolding. The statue was then draped with heavy canvas to protect the gilding process, which started right away. The figure was sized first with zinc oxide and then white lead. Next the layer of twenty-three carat gold was carefully brushed onto the sticky surface and burnished to produce the desired shine. Approximately a week was needed to cover the entire statue. The work was done by the Lippold Interior Decorating Company of Salt Lake City. Alfred A. Lippold was an immigrant from Germany who had studied under a master artist.[41]

Inspecting the angel Moroni. (Scrapbook)

Inspecting the angel Moroni. (Scrapbook)

The angel Moroni. (Scrapbook)

The angel Moroni. (Scrapbook)

On Tuesday morning, October 19, Stanley Child and the masonry crew raised the statue to the top of the tower. President David O. McKay came from Salt Lake City specifically to be present and witness this milestone event.[42] A group of about forty interested spectators gathered east of the temple to watch. Among them were President McKay; the sculptor, Millard Malin; the temple architect, Edward O. Anderson; and stake presidents W. Noble Waite, John M. Russon, and Howard W. Hunter. President McKay noted in his diary that “it took ten men two and a half hours to move [the angel] up inch by inch and place it on the pole, an iron rod coming down and fitting into a socket, and it is anchored into the ground.”[43] Anderson explained that the crew used a compressed-air “tugger” hoist to lift the statue and a monorail to move it into place. Los Angeles newspapers covered this event. The Examiner quoted President McKay’s assessment of the angelic figure: “This is a work of art. Mr. Malin, I think, proved his artistry and produced a magnificent statue. The workmanship is excellent and the character of the statue typifies the laymanites [sic].”[44]

On the temple roof preparing for gilding. (Howard Winn)

On the temple roof preparing for gilding. (Howard Winn)

Moroni being lifted to the fourth floor roof, October 6, 1954. (Howard Winn)

Moroni being lifted to the fourth floor roof, October 6, 1954. (Howard Winn)

According to the architectural plan, the angel was placed to face the front of the temple, which was toward the southeast. President McKay, however, asked the temple architect to have the statue turned so that it faced due east.[45] This eastward orientation may be symbolic of watching for the Lord’s Second Coming, which has been compared to the dawning in the east of a new day (Matthew 24:27; compare Joseph Smith—Matthew 1:26). Not all Latter-day Saint temples face east, but more face that direction than any other. Necessary planning for the change took more than three months, and scaffolding was left in place around the top of the tower. The angel finally was turned in January 1955. The scaffolding was then stored in the tower to facilitate possible future regildings or other attention the angel might require.[46]

A unique spectacle occurred on an afternoon early in 1955. About one hundred seagulls flew in from the ocean and began circling the golden figure of Moroni. Gene Sherman, a columnist with the Los Angeles Times, stated that “the scene startled passersby on Santa Monica Blvd.” He believed the symbolism was appropriate because seagulls had played such a key role in the Mormon pioneers establishing their settlement in the Salt Lake Valley.[47]

The figure on the tower became a source of local interest. One neighbor reported that she had always felt uneasy when her husband was away on business, but since the angel on the spire was watching over her home, “she had a sense of security that she had never felt before.”[48] Another neighbor told the director of the temple visitors’ center that each morning she looked out of her window and saw “St. Moroni blessing the people” and felt sure he was blessing her as well.[49] The story was told of a neighbor east of the temple who was asked if she had visited the temple grounds and unwittingly replied “No, I’m waiting until the angel turns around and faces me. Imagine my surprise when I woke up one morning and discovered that the angel was looking right down my street.”[50]

The angel being lifted to the tower top, October 19, 1954 (note that the horn has not been added). (Howard Winn)

The angel being lifted to the tower top, October 19, 1954 (note that the horn has not been added). (Howard Winn)

The angel being lifted to the tower top, October 19, 1954 (note that the horn has not been added). (Howard Winn)

The angel being lifted to the tower top, October 19, 1954 (note that the horn has not been added). (Howard Winn)

The gilding under way. (George Bergstrom)

The gilding under way. (George Bergstrom)

Gilding the horn after the angel is in place atop the temple tower. (Paul L. Garns)

Gilding the horn after the angel is in place atop the temple tower. (Paul L. Garns)

Moroni’s head, nearly two feet tall. (Garns)

Moroni’s head, nearly two feet tall. (Garns)

Moroni’s head, nearly two feet tall. (Garns)

Moroni’s head, nearly two feet tall. (Garns)

President David O. McKay inspects the gilded angel on the roof. (Scrapbook)

President David O. McKay inspects the gilded angel on the roof. (Scrapbook)

Left to right: Photographer Paul Garns, gilder Alfred Lippold, and contractor Soren Jacobsen posing with Moroni. (Paul L. Garns)

Left to right: Photographer Paul Garns, gilder Alfred Lippold, and contractor Soren Jacobsen posing with Moroni. (Paul L. Garns)

The angel Moroni. (Paul L. Garns)

The angel Moroni. (Paul L. Garns)

The Temple’s Interior

Construction nearly complete. (Paul L. Garns)

Construction nearly complete. (Paul L. Garns)

While the exterior of the temple was being completed, work was starting on its interior. During the closing weeks of 1953, plastering of the temple’s walls and ceilings commenced. This decorative plaster demanded a particularly high skill level. Specific steps were taken to prevent the condensation of moisture on the surfaces of concrete walls, a problem that had plagued the recently constructed Idaho Falls Temple. Using wire brushes and muriatic acid as necessary, workmen first made sure cement walls were perfectly clean. Lightweight plaster was next applied to the wall; it was then given a vapor seal. A network of metal lath held a second layer of plaster in place. If the lathing were laid out end to end, it would reach 122 miles. Acoustical plaster was four layers thick, while all the rest was three layers thick. Wall plaster was at least ¾ inches thick and was polished to a glass-smooth surface. Architect Anderson later explained that “the two layers of plaster with vapor seal and air space between provide excellent protection for the decorative murals.” Thirty-nine men worked on this project, Joseph E. Young heading the plasterers and Lee Freeman heading the lathing crew. Three of Young’s four sons worked with him on the plastering crew. In all, there were thirty-four father-son combinations that worked on the temple. By the time the plasterers finished, 1.75 million pounds of plaster had been mixed with three million pounds of “clean white river-bottom sand” to cover the walls.[51]

Working on the temple ceiling. (Howard Winn)

Working on the temple ceiling. (Howard Winn)

Eight varieties of marble, quarried in Vermont, Tennessee, Italy, and France, also adorned the temple’s interior. Vert d’Issorie from Italy was used in the annex. Westland Cippolino from Vermont and Tennessee Pink adorned other areas of the first floor. The grand spiral stairway and second-floor halls featured Rose de Brignoles from France. The altar in the creation room was of Rouge Antique from France. Roman Travertino and Botticino from Italy adorned the Garden Room. Botticino was also found in the celestial and sealing rooms. Loredo Chiaro with Garnet from Italy was placed in the bureau of information. Edward O. Anderson not only designed the temple itself, but he also “arranged its landscaping and selected its interior carpeting, draperies, and furnishings.”[52]

The empty celestial room. (Howard Winn)

The empty celestial room. (Howard Winn)

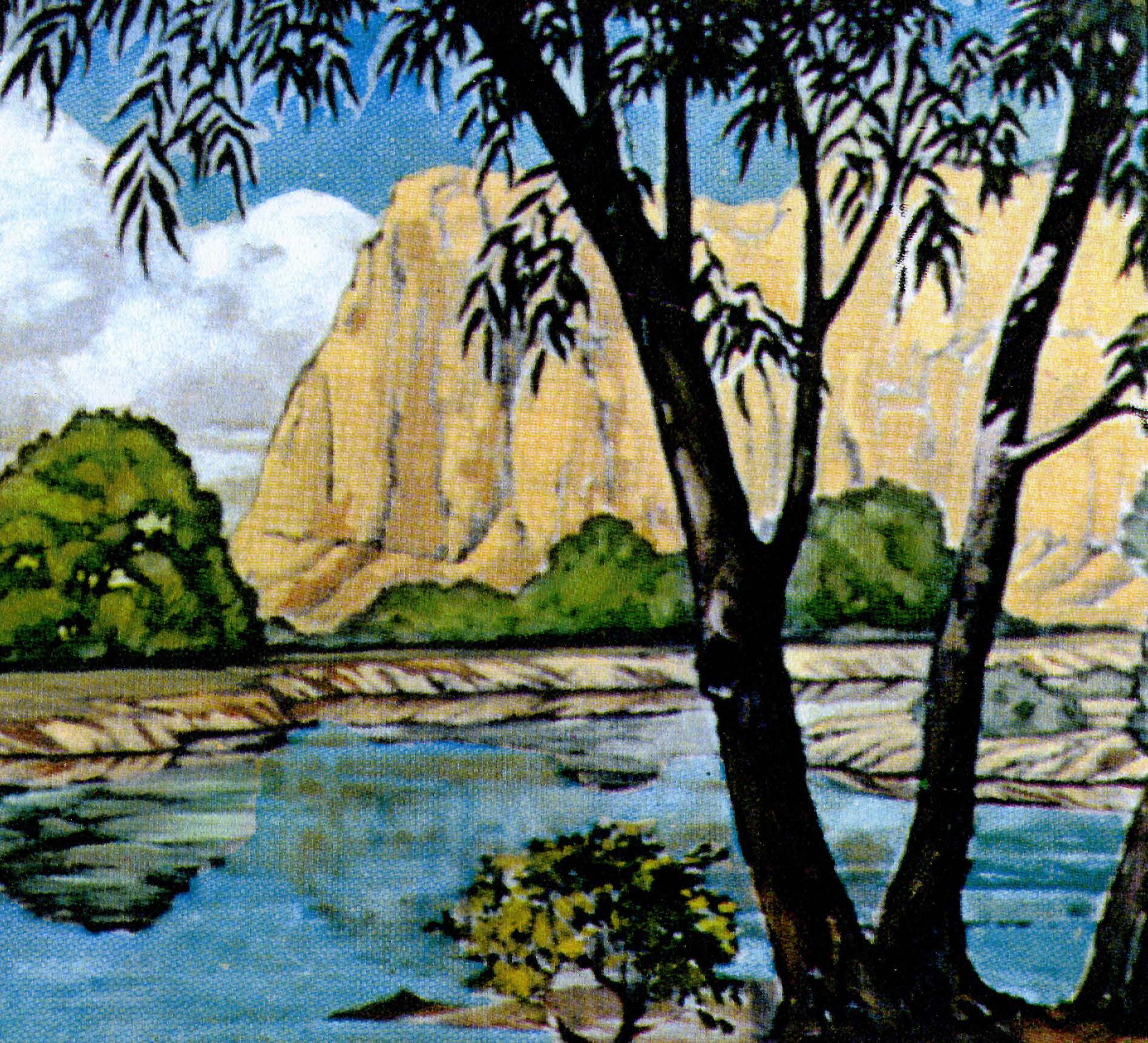

The temple’s large ordinance rooms featured beautiful murals. The creation room was long and oval. One wall depicted in swirling reds, oranges, and golds the formation of the universe; while the other represented a starry blue sky. Tiny lights twinkled like stars from the ceiling. The garden room was wider and had a large window on each side and at the back. It portrayed the idyllic pastoral scenes of Eden with animals at peace. Potted plants would complement the murals. The world room, another long space, “captures the stark but enchanting beauty of the desert” from California’s Death Valley on one wall and from southern Utah’s Monument Valley on the other. The terrestrial room “was planned for peace and comfort with subdued colors.” It was more highly illuminated and featured a large mirror panel at its back.

Joseph Gibby’s original sketch for the baptistry mural. (Courtesy of Joseph Gibby)

Joseph Gibby’s original sketch for the baptistry mural. (Courtesy of Joseph Gibby)

Wilshire Ward member Joseph Gibby, a Los Angeles artist and technical illustrator who taught college art courses, received the assignment to paint the baptistry mural. Harris Weberg, a noted book illustrator from Ogden, Utah, who had painted murals in the Idaho Falls Temple, was commissioned to paint the creation room. Edward Grigware, a nationally known muralist who was not a Latter-day Saint, received the assignment to paint the garden room murals. He had studied at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts and was a resident of Cody, Wyoming. Robert L. Shepard, who had also painted in the Idaho Falls Idaho and Manti Utah Temples, would create the world room murals (see images of the murals in chapter 6, pp. **). At the time he was serving as a bishop in the San Fernando Valley and was acting as an artistic consultant to Cecil B. DeMille during his production of The Ten Commandments. Each artist submitted preliminary drawings of his proposed murals to the First Presidency for approval. These drawing would later be one of the first displays in the new Los Angeles Temple Bureau of Information. The elegant celestial room was decorated by Alfred Lippold under the direction of Edward Grigware.[53]

The artists started their work in the Los Angeles Temple in October 1954 after the plastering in the room had been completed and had time to cure. Rather than painting on ordinary canvas, they would do their work on fine-quality Irish linen, which had been a gift to the temple. Each went about his work in a different way. Gibby projected a slide image of his approved drawing on the wall and traced it in charcoal. Grigware divided the wall into squares before sketching his Edenic pastoral drawing. Shepard sketched his “stark but enchanting beauty of the desert” depiction of “the lone and dreary world” freehand in charcoal before beginning the painting. Weberg didn’t do much preliminary drawing on the wall before starting his painting depicting the forces of creation.[54]

The steel support for the baptismal font. (Howard Winn)

The steel support for the baptismal font. (Howard Winn)

Each artist worked independently but took an interest in the work of the others. For example, Joseph Gibby recalled how he visited Edward Grigware in the garden room during a lunch break. “I stood there as he painted a delicate highlight on a little lamb’s eye. As he finished, he turned to me and said, ‘Brother Joe, has the Lord ever held your hand while you have been painting your mural in the font room?’ I answered, ‘no.’ He said ‘He has been holding my brush all this morning.’”[55]

Gibby’s mural in the baptistry depicted John baptizing the Savior in the River Jordan. As this work neared completion, the artist experienced a problem so went to visit with President David O. McKay, who happened to be visiting Los Angeles at the time. “‘I cannot paint the Savior’s face to my satisfaction. I need to know his complexion and coloring.’ Without hesitation President McKay said, ‘He had chestnut hair, hazel eyes and a fair complexion.’ Note that he said “had” (past tense) indicating his mortal state. That was all the Prophet said and I knew by the way he looked as he said it that he knew Jesus.”[56]

Latter-day Saint temples include a font where baptisms are performed vicariously in behalf of those who died without the blessings of the gospel. Typically temple fonts are situated on the backs of twelve oxen, representing the tribes of Israel. They are patterned after the “sea” at Solomon’s temple (see 1 Kings 7:23–26). The font and oxen for the Los Angeles Temple were sculptured by the same group who produced the statue of the angel Moroni for the temple. They worked in the same studio at the Buehner Company where the angel was created. The sculptors determined that “they could not use modern beef cattle for models because of their squarish bred-for-beef appearance. They have selected instead the rangier Spanish fighting bulls with large horns.” The result was praised as being more realistic. The artists first constructed a framework or “mandril,” applied the modeling clay, and then carefully finished each figure. They produced the heads, necks, and forequarters of only three oxen. They were each then cast in plaster four times and shipped to the foundry in New York for casting in metal. In the temple they were assembled to form the font’s full circle.[57]

Landscaping the Grounds

Preparing a tree for transportation to the temple site. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

Preparing a tree for transportation to the temple site. (Anderson Collection, CHL)

The temple was surrounded by beautiful grounds, covering thirteen acres of the twenty-four-acre site. The architect pointed out that the temple grounds are higher than the immediately surrounding neighborhoods. For example, the temple’s forecourt is 50 feet above Santa Monica Blvd. “On account of this elevation and by careful planting,” he believed the temple grounds could be secluded from their surroundings. “With the elevation, the setting, and with the mountains and ocean in view in the background, we feel that a type of spiritual isolation can be attained on these temple grounds much as though they were surrounded by a wall.”[58]

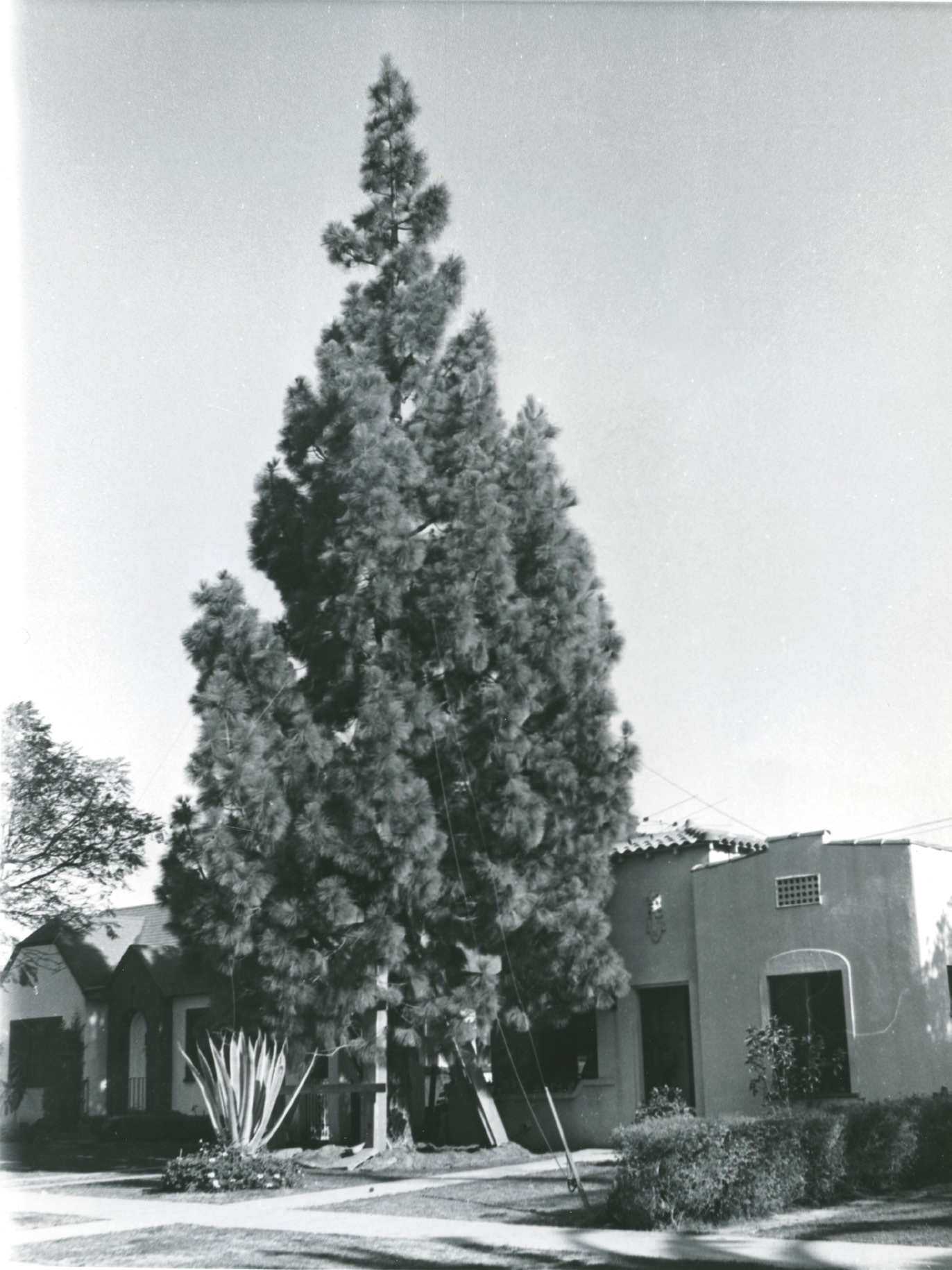

Work on the landscaping started early, while the temple was still under construction. During the summer of 1953, for example, the automatic sprinkler system for the four acres of lawn was being installed. Twenty-two olive trees, which are popular “shade and ornamental trees in Southern California,” lined the walks up from Santa Monica Blvd. Although they were rumored to have been grown from slips or shoots taken from trees on the Mount of Olives in the Holy Land, they actually came from the La Mirada area in Orange County thirty miles southeast of the temple, where a new subdivision forced the removal of an olive grove.[59] These trees, 35 to 40 feet wide and 35 feet tall, were brought in at night “under special permits because of the great width.” During January 1954 a large pine tree that had been growing for many years only four blocks from the temple was dug up, boxed, and moved to the temple site; this was accomplished by the crew headed by Bishop Max Tollman, landscaping supervisor. Trees and shrubbery were also being planted along the east side of the property where telephone poles had been removed and wires buried.[60]

Landscaping as of July 1, 1954. (Howard Winn)

Landscaping as of July 1, 1954. (Howard Winn)

While full-time laborers did the actual building, Church members, some highly paid professionals in daily life, lent willing hands and hearts to perform cleanup work around the site. They hacked and hoed as they prepared the thirteen-acre grounds for landscaping. On one Saturday, 250 high school graduates from Southern California LDS seminaries gathered to pull weeds from temple lawns. Trees and other plants came from all over the world, including Canary Island Pines, three varieties of palms, bird of paradise trees, Coast Redwoods, liquid amber trees, coral trees, maidenhair trees, and two very rare Chinese ginkgo trees. Moving and planting these large trees was a major project; but when completed, the grounds would “appear as if they had been planted for many years.” Tall stately palms in front of the temple were held in place by guy wires until their root systems could become established. Teenage Latter-day Saint girls from the area contributed roses for a beautiful, quiet “MIA Maid” garden.[61]

Other Buildings on the Site

In addition to the temple, four other buildings were located on the site. Space was also left for an “inter-stake auditorium,”[62] but this facility was never built.

Presiding Bishop LeGrand Richards broke ground for the Beverly Hills Ward chapel on Saturday, January 13, 1951, as part of the Los Angeles Stake’s quarterly conference. During the 1930s, Bishop Richards had served as president of this stake. The 17,000-square-foot building was designed by Harold W. Burton, a ward member who had designed the Los Angeles Stake Center or Wilshire Ward chapel a quarter of a century earlier and who would be the architect for the Oakland Temple a decade later. The building would include a 350-seat chapel, cultural hall, seventeen classrooms, outdoor patios, and would be surmounted by a 70-foot clock tower.[63] Ward members worked hard to raise their share of the $200,000 cost. An outstanding event was a show staged at the noted Carthay Circle Theatre, which netted $11,000.[64] The chapel was constructed by Jackson Brothers contractors, headed by ward members Harold and William Jackson; volunteer labor was also used extensively. In 1952 the name of the ward was changed from Beverly Hills to Westwood to be consistent with the chapel’s location. The first meetings in the new building were on December 15 of that year. It was dedicated by Elder Harold B. Lee of the Twelve on April 12, 1953.[65]

The nearby Westwood Ward chapel. (Linda Gerber)

The nearby Westwood Ward chapel. (Linda Gerber)

The temple site looking north from the top of the temple, showing (from left to right) the ward chapel, the mission home, and the excavation for the bureau of information. (Anderson Collection, CHL

The temple site looking north from the top of the temple, showing (from left to right) the ward chapel, the mission home, and the excavation for the bureau of information. (Anderson Collection, CHL

Ground was broken for the California Mission home by President David O. McKay in a simple ceremony on Monday afternoon, January 5, 1953. It was located midway between the Westwood Ward chapel and the temple. This was the first mission headquarters actually built by the Church in California, others having been purchased or rented. Also designed by Harold W. Burton, it was a one-story structure measuring 130 by 100 feet. Its exterior featured golden-colored Roman tapestry brick. It included office facilities, an apartment for the mission president’s family, and rooms for elders, sister missionaries, and guests grouped around a 72-by-45-foot open-air patio.[66] By November of that same year, mission president Bryan L. Bunker, his family, and missionary staff were moving into these new facilities.[67]

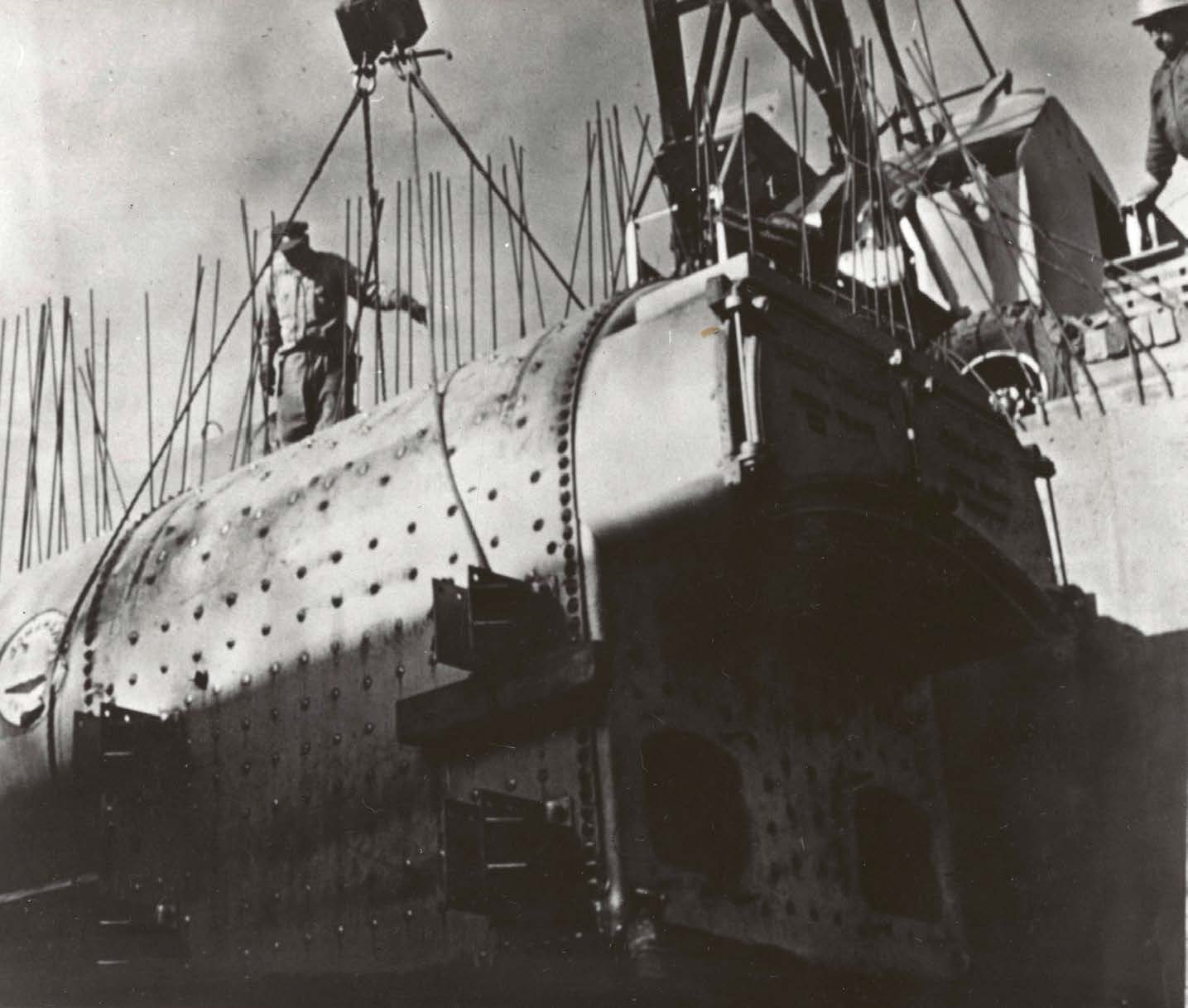

The boiler being raised into position. (George Bergstrom)

The boiler being raised into position. (George Bergstrom)

Following the positive experience on Temple Square in Salt Lake City, the Church established bureaus of information or visitors’ centers at several of its temples and historic sites during the first half of the twentieth century. The bureau of information in Los Angeles was designed by Edward O. Anderson, who also was architect for the temple. Measuring 160 by 78 feet, the bureau was located just north of the temple. Construction on this facility commenced in July 1953. By the summer of the following year, it was completed to the point that temple construction offices could be moved from the Harold Lloyd home into the bureau’s basement. The old home was then razed to open the way for road work and landscaping to move forward. As a fund-raising project, Church member volunteers then carefully cleaned the salvaged bricks from the home for sale and reuse.[68] Like the temple, the one-story bureau was faced with off-white Mo-Sai panels, so the exteriors of these two buildings were matched in appearance. By the spring of 1955, the bureau was receiving visitors.

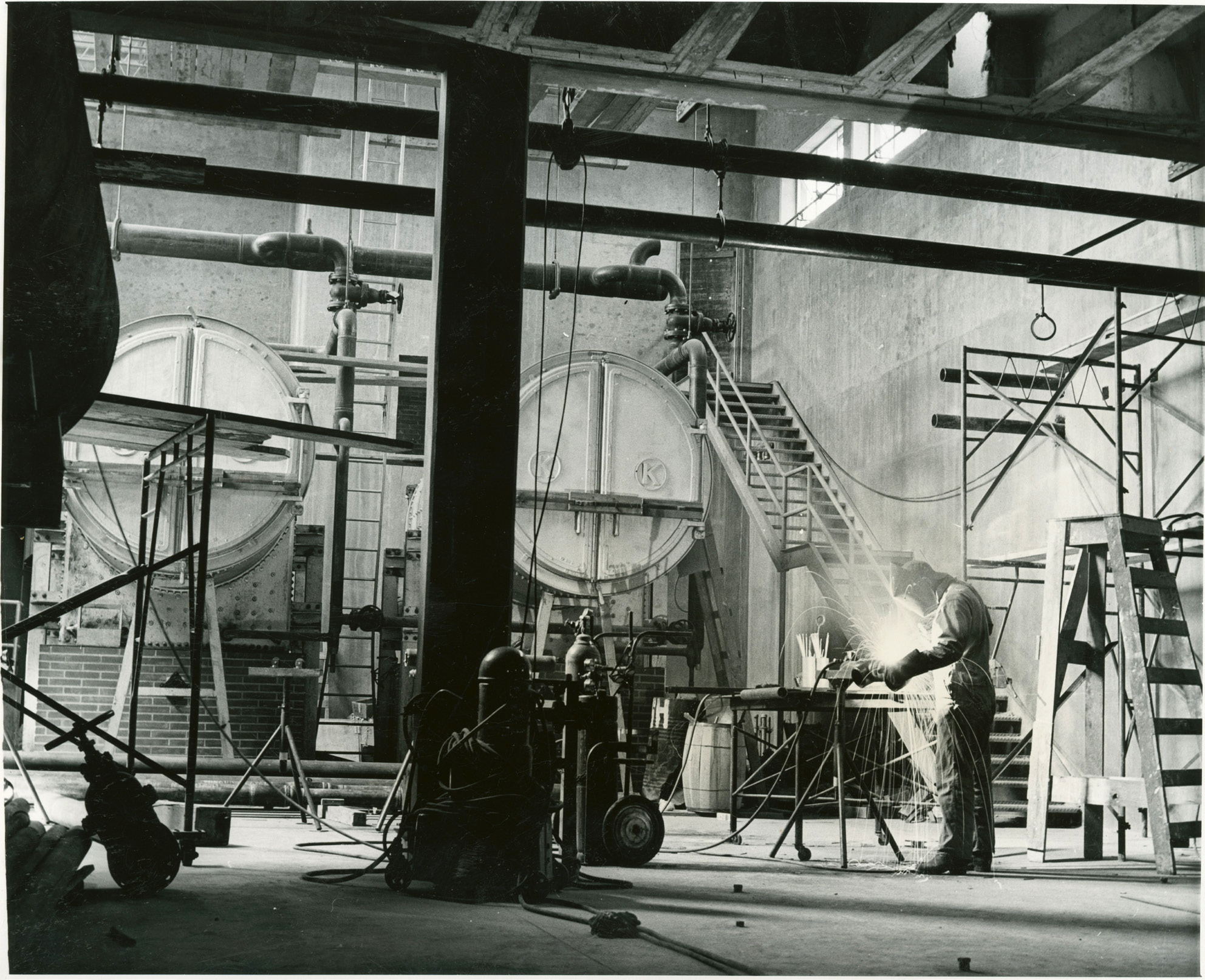

The fourth auxiliary structure was the utilities building. It measured 180 by 32 feet and included both heating and air-conditioning equipment. It contained two 500-gallon boilers for steam and two Carrier ice machines for chilled water. These were connected to the temple by more than 18 miles of pipe in a 512-foot reinforced concrete tunnel. This equipment permitted air throughout the temple to be changed every fifteen to twenty minutes. The pipes and air ducts were the work of Edmond P. Evans of Evans Plumbing in Salt Lake City and of Thomas Hodge Sheet Metal in Los Angeles. The plant also provided hot water for the laundry, baptismal font, and culinary needs. It also served the bureau of information and mission home. The latest safety devices and alarms were installed, and there was a 10,000-gallon oil tank buried just outside to provide emergency fuel.[69]

While all these facilities were being completed, plans were being made for the temple’s open house and dedication.

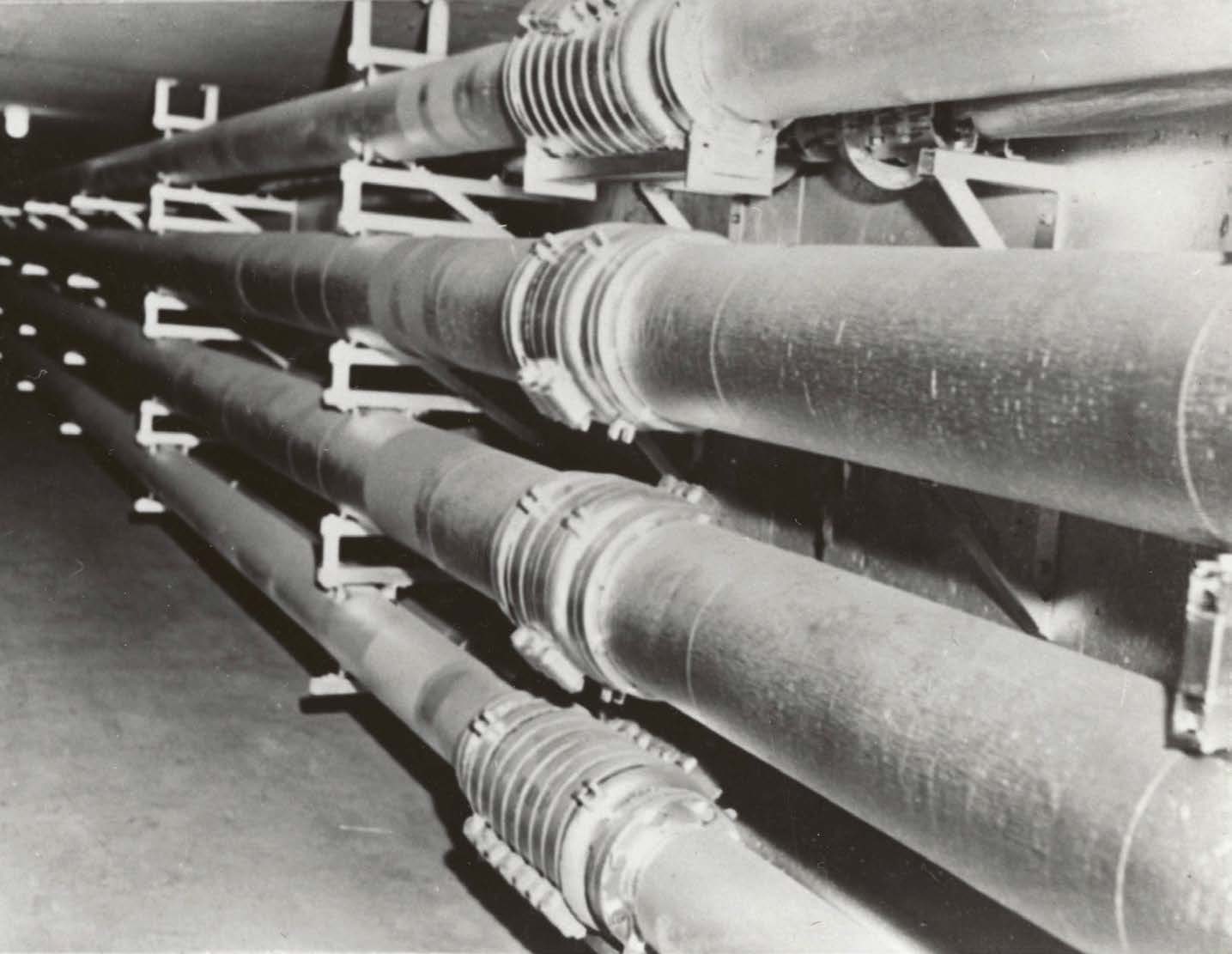

The utility tunnel. (George Bergstrom)

The utility tunnel. (George Bergstrom)

The boilers in the utility building. (Howard Winn)

The boilers in the utility building. (Howard Winn)

The utility building. (Katie Hendrickson)

The utility building. (Katie Hendrickson)

Notes

[1] “‘Our’ Los Angeles Temple,” Instructor, November 1955, 352.

[2] Joseph Lundstrom, “Okeh Given to Build L.A. Temple,” Church News, July 9, 1952, 3; “Paul Iverson Delivers Permit from City to Temple Builder,” California Intermountain News, September 27, 1955, 16.

[3] “Weed Cutting Signifies Start of Actual Work on Building” and “Jackson Brothers Commissioned to Prepare Temple Ground,” California Intermountain News, September 27, 1955, 16 and 17.

[4] “Special Meeting Held to Plan Construction,” Church News, August 13, 1952, 2.

[5] Edward O. Anderson, “The Los Angeles Temple,” Improvement Era, April 1953, 225.

[6] “385 Yards of Concrete Poured in One Day for Los Angeles Temple,” Church News, October 18, 1952, 3.

[7] “Los Angeles Temple Architect: Elder Anderson Given Assignment,” Church News, December 27, 1952, 7.

[8] Anderson, “Los Angeles Temple,” 226.

[9] Gregory A. Prince and Wm. Robert Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2005), 258.

[10] W. Noble Waite in Conference Report, October 1952, 77.

[11] Carl W. Buehner, Do unto Others . . . (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1957), 152.

[12] Mary S. Jordan, “The Los Angeles Temple—Where Workmen Pray Together,” Instructor, July 1953, 196–97.

[13] Chad M. Orton, More Faith Than Fear: The Los Angeles Stake Story (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1987), 184; Arthur and Elna Wallace Stories Related to the Construction of Los Angeles Temple, in Los Angeles Temple scrapbook.

[14] Anderson, “Los Angeles Temple,” 225.

[15] Joseph Lundstrom, “Los Angeles Temple Construction: Foundations Completed; Walls Push Upward,” Church News, March 14, 1953, 5, 11; “Los Angeles Temple Grows Apace,” Church News, April 25, 1953, 8–9.

[16] Francis M. Gibbons, David O. McKay: Apostle to the World, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1986), 357–58.

[17] Orton, More Faith Than Fear, 185.

[18] “Temple Progress Pleases President McKay,” Church News, August 8, 1953, 4.

[19] Joseph Lundstrom, “Perfection Is Watchword: Los Angeles Temple Builds Skyward,” Church News, June 6, 1953, 14; Lundstrom, “LA Temple Nears Eventual Height,” Church News, September 19, 1953, 6.

[20] Lundstrom, “Perfection Is Watchword,” 14.

[21] Quoted in Richard O. Cowan, Temples to Dot the Earth (Springville, Utah: Cedar Inc. 2011), 159.

[22] See Joseph Lundstrom, “Mo-Sai—25,000 Pieces Beautify L.A. Temple,” Church News, May 8, 1954, 1, 8; Buehner, Do unto Others,153.

[23] Edward O. Anderson, “Solidity and Grace: Keynote of Mormon Temple,” Architectural Concrete, No. 61 (1957): 3.

[24] Edward O. Anderson, “The Los Angeles Temple,” January 19, 1956, typescript, Church History Library, MS 757, 2.

[25] Joseph Lundstrom, “Millions in Donations within Sight,” Church News, March 13, 1954, 14.

[26] Prince and Wright, David O. McKay, 258; “Cornerstone Ceremonies: Los Angeles Temple Rites Slated, Dec. 11,” Church News, November 21, 1953, 2.

[27] Henry A. Smith, “L.A. Temple Cornerstone Ceremonies Readied,” Church News, December 5, 1953, 1.

[28] California Intermountain News, September 27, 1955, 3, 45.

[29] “Appreciation and Gratitude Voiced by Church Leader,” Church News, December 19, 1953, 6–11; for a complete transcript of the proceedings, see appendix F.

[30] “Mormon Choir of South California Will Sing at Cornerstone Laying,” Church News, November 28, 1953, 2.

[31] Kenneth R. Jensen, “California Mormon Choir Notes Seventh ‘Birthday’ at Dinner,” Church News, September 17, 1960, 7.

[32] For a complete list of the cornerstone box’s contents, see appendix G.

[33] Joseph Lundstrom, “140-Foot Tower Hoisted into Place,” Church News, January 23, 1954, 7; “Spire Crowns Tower of Temple,” California Intermountain News, September 27, 1955, 30.

[34] Joseph Lundstrom, “L.A. Temple Construction Enters Third Year,” Church News, August 7, 1954, 8–9.

[35] Elmer W. Lammi, “Moroni Statue Tops D. C. Spire,” Church News, May 19, 1973, 3.

[36] J. Michael Hunter, “I Saw Another Angel Fly,” Ensign, January 2000, 30–36.

[37] Prince and Wright, David O. McKay, 258.

[38] Jack Sears, “A Sacred Witness to All Men,” Instructor, March 1956, 73–74.

[39] Elaine Cannon, The Truth about Angels (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1996), 88–90; Sears, “Sacred Witness to All Men,” 74.

[40] Henry A. Smith, “Another Monument to Moroni,” Church News, January 16, 1954, 1, 6–7; Prince and Wright, David O. McKay, 258.

[41] John L. Hart, “Man with a Midas Touch,” Church News, August 8, 1981, 3.

[42] “Angel Moroni Statue Lifted to Temple Top, “California Intermountain News, October 12, 1954, 1; “Angel Moroni Statue atop Temple,” California Intermountain News, October 26, 1954, 1; Francis M. Gibbons, David O. McKay: Apostle to the World, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1986), 342–43, 357–58; Joseph Lundstrom, “Angel Moroni Statue Lifted to Top of L.A. Temple Steeple,” Church News, October 23, 1954, 4; “Statue of Angel Hoisted atop Los Angeles Temple.” Church News, March 15, 1958, 16.

[43] McKay diary entry for October 19, 1954, David O. McKay papers, MS 668, box 33, folder 8.J Willard Marriott Library Special Collections, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

[44] “Statue of Angel Placed on Los Angeles Temple,” Los Angeles Examiner, October 20, 1954.

[45] “Now Faces East,” Church News, February 5, 1955, 13.

[46] “Now Faces East,” Church News, February 5, 1955, 13.

[47] “Seagulls Salute the Statue of Angel Moroni,” California Intermountain News, February 15, 1956.

[48] Buehner, Do unto Others,157.

[49] California Intermountain News, September 27, 1955, 39.

[50] Orton, More Faith Than Fear, 187.

[51] Joseph Lundstrom, “Immense Plastering Job Nearly Finished,” Church News, November 6, 1954, 4; Anderson, “Solidity and Grace,” 4.

[52] “‘Our’ Los Angeles Temple,” Instructor, November 1955, 352.

[53] Edward O. Anderson, “Los Angeles Temple,” Improvement Era, November 1955, 806.

[54] Joseph Lundstrom, “Artists Paint Temple Murals,” Church News, March 5, 1955, 1, 6–7; Anderson, “Los Angeles Temple,” Improvement Era, November 1955, 806.

[55] Joseph Gibby, letter to Richard Cowan, June 23, 1988.

[56] Joseph Gibby, letter to Betty McEwan, June 30, 1986, copy in possession of author.

[57] “Baptismal Font Sculptured for Los Angeles Temple,” Church News, January 23, 1954, 1, 6; “Sculpture Work Progresses for New Temple Fonts,” Church News, September 4, 1954, 1.

[58] Anderson, “Los Angeles Temple,” April 1953, 227.

[59] Anderson, “Los Angeles Temple,” 1956 typescript, 1.

[60] “Baptismal Font Sculptured for Los Angeles Temple,” Church News, January 23, 1954, 1.

[61] Albert L. Zobell Jr., “Los Angeles,” Improvement Era, November 1963, 953; Anderson, “Los Angeles Temple,” November 1955, 807; Henry A. Smith, “L.A. Temple Construction in Final Stages,” Church News, July 16, 1955, 6–7.

[62] “Pres. McKay’s Address at Opening Conference Session,” Church News, April 14, 1956, 2.

[63] “Beverly Hills Ward Breaks Ground for New Chapel,” Church News, January 24, 1951, 14.

[64] “Ward Show Nets $11,000,” Church News, April 2, 1952, 3.

[65] “Now Westwood Ward,” Church News, July 16, 1952, 13; “Westwood Ward Chapel Dedicated by Elder Lee,” and Beatrice Sparks, “Westwood Members First Meeting in Beautiful Chapel,” California Intermountain News, September 27, 1955, 37, 68.

[66] Joseph Lundstrom, “President McKay Breaks Ground,” Church News, January 10, 1953, 1; Lundstrom, “Foundations Completed; Walls Push Up,” Church News, March 14, 1953, 5, 11; “Ground Broken on Temple Site for California Mission Home,” California Intermountain News, September 27, 1955, 36.

[67] “California Mission Office Moved,” Church News, November 21, 1953, 12.

[68] Orson Haynie interview, February 2017.

[69] “Air Conditioning, Cooling Unit Ready,” Church News, February 5, 1955, 13.