Beginnings

Richard O. Cowan, "Beginnings" in A Beacon on A Hill: The Los Angeles Temple (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 1–10.

1830 The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is organized in western New York

1846 Ship Brooklyn sails from New York (February 4)

Mormon Battalion is recruited in Iowa (July 15)

Brooklyn Saints arrive at San Francisco Bay (July 31)

1847 Mormon Battalion arrive at San Diego (January 29)

Brigham Young and Mormon pioneers arrive at Salt Lake Valley (July 24)

President Young sends epistle to California Saints (August 7)

1857 Brigham Young calls Saints to return to Utah (fall)

1895 Los Angeles Branch is organized (October 20)

1906 San Francisco earthquake (April 18); mission headquarters is moved to Los Angeles

1917 United States enters World War I (April 6)

The story of the Los Angeles Temple did not begin in California during the twentieth century. Rather, its roots go back to the early nineteenth century in the state of New York.

Latter-day Saint Beginnings

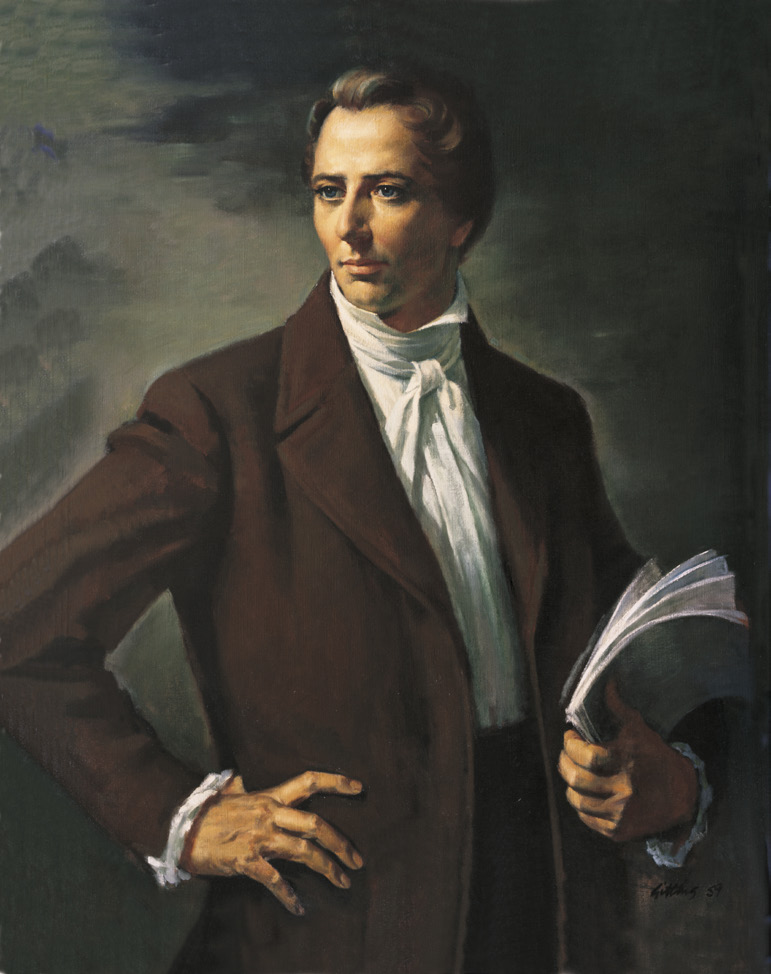

Western New York in the early 1800s has been called the “burned-over district” because of the revivalist fervor that prevailed there. Confused by the conflicting claims of the different churches in his area, in 1820 fourteen-year-old Joseph Smith turned to the Bible for help. He was moved by a New Testament promise: “If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God, that giveth to all men liberally, and upbraideth not; and it shall be given him” (James 1:5). Joseph therefore went to a nearby grove of trees to seek enlightenment through fervent prayer. He reported that God the Eternal Father and his Son, Jesus Christ, appeared to him. The young man affirmed that their “brightness and glory defy all description” (Joseph Smith—History 1:17). He was promised that he would be instrumental in restoring the true faith to the earth.

Prophet Joseph Smith. (© Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Prophet Joseph Smith. (© Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

This was only the first in a series of divine manifestations that Joseph recorded. Three years later, an angelic messenger named Moroni told him the whereabouts of a religious history of the ancient inhabitants of America. Translated by Joseph Smith, this record was published as the Book of Mormon and was named for one of the ancient historians most responsible for its compilation. Among other things, it relates how Jesus Christ visited the Western Hemisphere following his Resurrection and Ascension in the Holy Land to bless his “other sheep” in the New World (see John 10:14–16). Thus the Book of Mormon has been designated as “Another Testament of Jesus Christ.” In 1829, other heavenly ministrants brought back the authority of the lesser Aaronic and higher Melchizedek Priesthoods. All these events led to the formal organization of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints the following year. Thus Latter-day Saints regard their Church as a restoration of New Testament Christianity.

Almost from the beginning, Latter-day Saints have been a temple-building and temple-attending people.[1] For them, temples are more than ordinary meetinghouses. They regard temples as truly the “house of the Lord,” where, through holy instructions and sacred “ordinances,” or ceremonies, the faithful learn of their eternal destiny and enter into sacred covenants with God.

At Kirtland, Ohio, the Saints overcame poverty and persecution to build their first temple in the mid-1830s. As the temple neared completion, the Saints who met in it enjoyed a rich outpouring of spiritual gifts—including prophecy, speaking in tongues, and visions of angels. Joseph Smith declared that “this was a time of rejoicing long to be remembered.”[2] These divine phenomena, long missing from the earth, culminated in glorious experiences during the day-long dedication of the temple on Sunday, March 27, 1836. One week later, on April 3, Joseph recorded that Jesus Christ appeared in glory to accept the temple and that Elijah the prophet restored the “sealing keys” (or authority) “to turn the hearts of the fathers to the children, and the children to the fathers” (D&C 110:15; see Malachi 4:5–6). Within a few years, the first genealogical societies were organized in both Europe and North America. Latter-day Saints often refer to this interest in our ancestors as “the spirit of Elijah.”

The Kirtland Temple.

The Kirtland Temple.

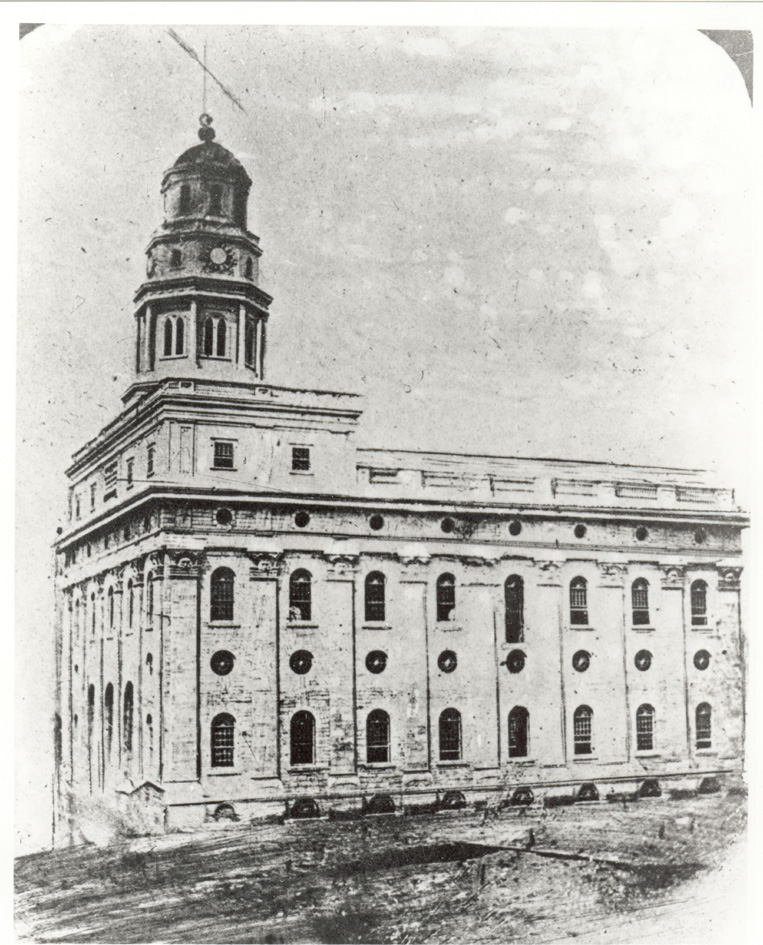

Sacred temple ordinances were unfolded while the second Latter-day Saint temple was being built at Nauvoo, Illinois. In 1840, Joseph Smith taught the Saints that they could be baptized in behalf of the dead (compare 1 Corinthians 15:29). They eagerly went into the Mississippi River to perform this ordinance, thus making gospel blessings available to their loved ones who had died without this opportunity. In 1842, the Prophet presented the endowment, which teaches participants how to return to the presence of God through making and keeping sacred covenants.[3] Joseph recorded that on May 4 he had “spent the day” with a select group “instructing them in the principles and order of the Priesthood, attending to washings, anointing, endowments and the communication of keys pertaining to the Aaronic Priesthood, and so on to the highest order of the Melchisedek Priesthood” and teaching all the “principles by which any one is enabled to secure the fullness of those blessings” and be prepared to dwell in the presence of God “in the eternal worlds.”[4] Soon couples were being “sealed,” or married, “for time and for all eternity” as they made solemn covenants to be faithful to one another and to keep God’s commandments (see D&C 132:7–20). Children could also be linked to their parents through sacred ceremonies performed by priesthood authority.

The Nauvoo Temple.

The Nauvoo Temple.

The forces of religious bigotry against the fledgling Church escalated with the murders of Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum in 1844. As anti-Mormon persecution continued, the Saints in Nauvoo, under the leadership of Smith’s successor, Brigham Young, made preparations for their now-famous trek across the plains to new homes in the Rocky Mountains.

Beginnings in California

Church leaders in Nauvoo counseled members living in the northeastern United States not to join them for the lengthy and difficult journey across the plains but rather to charter a ship, sail to the West Coast, and then make the relatively short overland trip to the Great Basin. Therefore, Samuel Brannan, the presiding elder in the New York City area, chartered the sailing ship Brooklyn and began collecting needed supplies. With 238 Latter-day Saints on board, the ship sailed from New York on February 4, 1846—interestingly the same day that the first overland pioneers departed from Nauvoo and crossed the Mississippi River on their way west.[5]

The Brooklyn’s six-month voyage around Cape Horn was undoubtedly one of the longest religious voyages in history. The ship arrived in San Francisco Bay on July 31, 1846, doubling the population of the small Mexican village of Yerba Buena. They were the first Anglo group to settle in what would become the city of San Francisco. Thus they established the first Mormon settlement in the West—a year before Brigham Young and the pioneers reached the Salt Lake Valley.

The Mormon Battalion

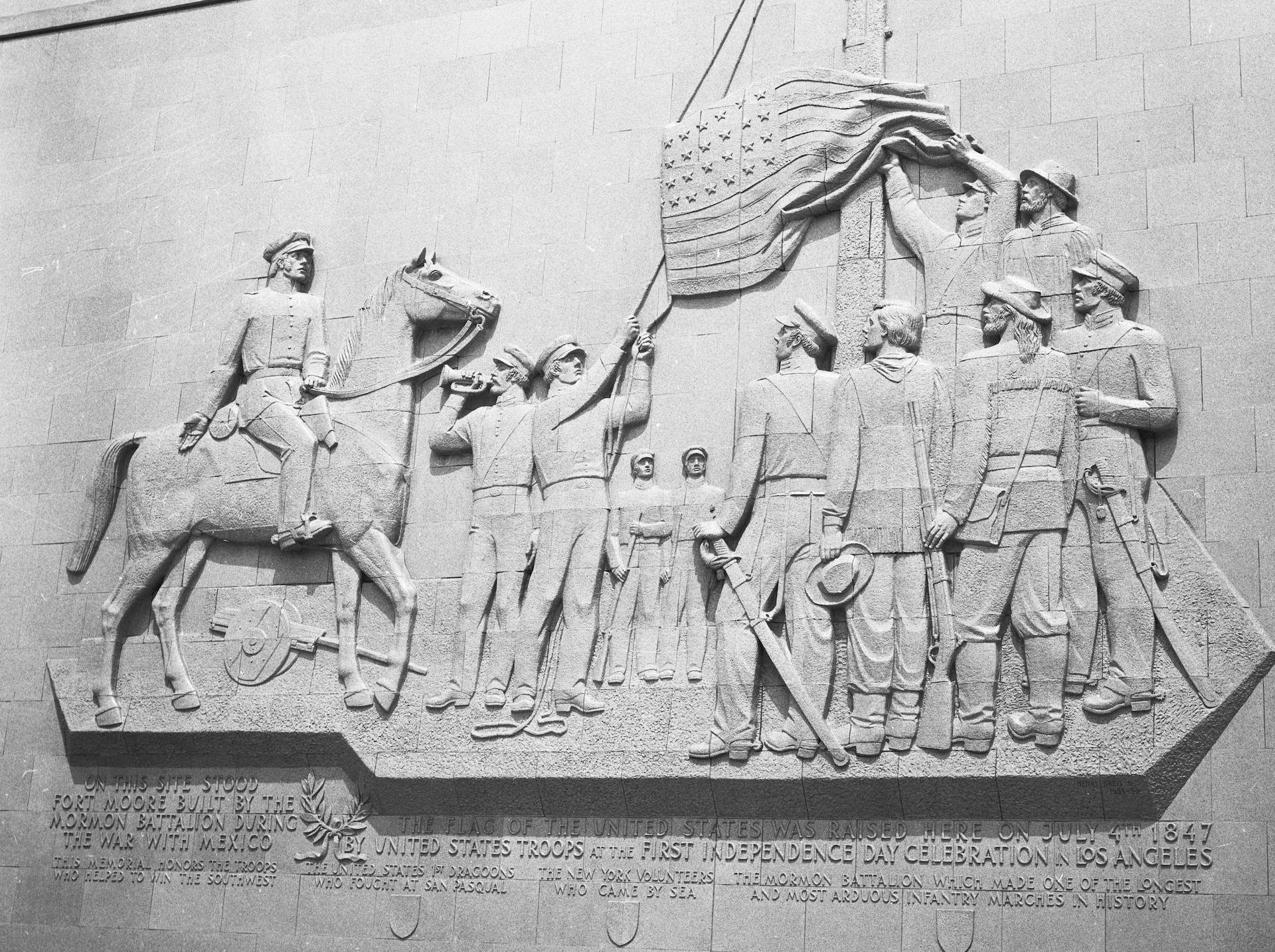

The Mormon Battalion

Historic Site, San Diego.

In 1846 the United States Army recruited five hundred able-bodied men from among the Mormon pioneers in western Iowa to fight in the war against Mexico. On July 15, as President Brigham Young was bidding farewell to the volunteers, he declared: “I said I could prophesy that the time would come when some one of the Twelve or a High Priest would come up and say, can we not build a Temple at Van Couvers Island, or in California.” Even though he insisted that the next of these holy houses would be built in the tops of the mountains, this may be the earliest hint of a temple also in California.[6] Following one of the longest infantry marches in military history, the Mormon Battalion reached the Pacific Coast in January 1847. While assigned to duty in San Diego and Los Angeles, these Latter-day Saint soldiers helped to build up both communities. Following their discharge, many of the Battalion men went to Northern California to find work before rejoining their families. One group was digging the millrace on the American River when gold was found. The exact date of this momentous event remained in doubt until the discovery of an entry in the diary of Mormon Battalion member Henry Bigler, who recorded that it occurred on January 24, 1848.

Meanwhile, in the spring of 1847, Brannan crossed the Sierra Nevada and Great Basin to meet Brigham Young, with the hope of persuading him to bring the Mormon pioneers to California. Brannan met them in present-day Wyoming and then continued with them to the Salt Lake Valley. On August 7, just two weeks after the first body of overland Saints trekked into the valley, Brannan was preparing to return to the coast, undoubtedly disappointed that the main group was not coming with him. Brigham Young and the Twelve Apostles wrote a five-page “epistle” to the Saints in California. In this letter, they reemphasized their decision to remain in the Valley of the Great Salt Lake. The epistle agreed that California was “a goodly land” and that the Apostles did not wish to “depopulate” it of all Latter-day Saints, but they did wish to make the Salt Lake Valley the “stronghold” of the Saints. Nevertheless, the epistle stated that “in the process of time the shores of the Pacific may be overlooked from the temple of the Lord.” A century later, Latter-day Saints would interpret this statement as a prophecy that a temple, or perhaps temples, would one day be built on the West Coast.[7]

In 1851 Church leaders in the Great Basin assigned two Apostles, Amasa M. Lyman and Charles C. Rich, to establish a colony near Cajon Pass in Southern California. After purchasing the San Bernardino Rancho, the colonists set to work laying out their community, following the grid pattern characteristic of most Mormon towns. This colony was to serve as an outfitting station for Latter-day Saint immigrants coming by sea and then traveling to the Great Basin via a chain of settlements known as the Mormon Corridor. Although the settlement lasted only a few years, the Saints made an enduring contribution to the region in terms of roads, structures, and more advanced agricultural methods, including irrigation.

In 1857, allegations were made to US President James Buchanan that the Mormons in Utah Territory were rebelling against federal appointees. Without confirming these reports, Buchanan sent an army of twenty-five hundred men to restore order. Not knowing what the presumably hostile army would do, Brigham Young called all missionaries who were abroad, as well as settlers in outlying colonies, to come home and prepare to “defend Zion.” Following these instructions, most Latter-day Saints in California prepared to leave for Utah.

For the next three decades, there was no regular Latter-day Saint organization maintained in the Golden State. Many of the Saints who had chosen to remain in California became disaffected. During the 1880s, however, many Latter-day Saints fled from anti-Mormon persecutions in Utah. Some went to California and became the nuclei around which Church activity would revive.

The Church reopened its California Mission in 1892. For a decade, the focus of Latter-day Saint activity was in the San Francisco Bay Area. During the 1890s, Oakland had the largest and most active branch. In 1894, Karl G. Maeser, the famed Mormon educator, was called to preside over the mission and to direct an exhibit on education in Utah at San Francisco’s Midwinter Fair. His efforts attracted favorable publicity, and the Church began to grow more rapidly.

While most of the Church’s activity in California was concentrated in the north, things were happening in Southern California that would dramatically alter the face of the state and the Church. Los Angeles did not have a deepwater port and thus had remained a mediocre town until connected by rail to the north and the east. In 1887 the population was only 11,000, the same as it had been ten years earlier. In that year, however, the Santa Fe completed a rail line from Kansas City to Los Angeles. A memorable fare war broke out with the Southern Pacific. As passenger fares from the Midwest plummeted from one hundred dollars to just one dollar, suddenly thousands of people who had long dreamed of going to the coast decided that now was the time to make the move. The Southern Pacific alone brought 120,000 people in 1887. This avalanche of land boomers that flooded into Southern California matched the number who came during the gold rush.

Latter-day Saints were caught up in this excitement. In July 1884 Eliza Woolacott had come from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles with her wine merchant husband, two children, and two grandchildren. The Woolacott home became the focal point of Church activity for many years. Eliza, whose gracious hospitality had brought numerous Church dignitaries to her home, pleaded for missionaries and “wept with joy” in 1895 when two elders were assigned to serve in Los Angeles.[8] On October 20 of that year, the first conference of Southern California members since 1857 was held in Los Angeles and a branch was organized. At the close of that year, California’s Church membership had increased to 204, nearly doubling in two years. Los Angeles now had the largest congregation in the state, with 51 members. San Francisco had 46; Sacramento, 29; San Bernardino, 12; and San Diego, 9.

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire interrupted Latter-day Saint progress in the Bay Area. At 5:12 a.m. on April 18, the devastating earthquake struck. The resulting fires destroyed 490 blocks, including the headquarters of the California Mission. Rather than rebuilding in San Francisco, the Church decided to move mission headquarters to Los Angeles, where the work was still expanding rapidly.

On April 6, 1917, the very day Latter-day Saints gathered in the Salt Lake Tabernacle for their annual general conference, the United States entered World War I. The war would attract more Church members to California than ever before, ushering in a new chapter of Latter-day Saint history in the Golden State.

Notes

[1] For a discussion of Latter-day Saint temples, see James E. Talmage, The House of the Lord (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1962); Boyd K. Packer, The Holy Temple (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1980); Richard O. Cowan, Temples to Dot the Earth (Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, 1997).

[2] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1948), 2:392 (hereafter History of the Church).

[3] Talmage, House of the Lord, 99–100; History of the Church, 5:1–2.

[4] History of the Church, 5:1–2.

[5] For a more complete review of Latter-day Saint history in California, see Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1996).

[6] Leland R. Nelson, comp., The Journal of Brigham: Brigham Young’s Own Story in His Own Words (Provo, UT: Council Press, 1980), 170.

[7] Journal History of the Church, 7 August 1847.

[8] Leo J. Muir, A Century of Mormon Activities in California (Salt Lake City: Deseret Press: 1950), 1:108–9.