The Holy Land, June 1896–July 1896

Reid L. Neilson and Riley M. Moffat, eds., Tales from the World Tour: The 1895–1897 Travel Writings of Mormon Historian Andrew Jenson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 323–61.

As I sat alone upon the top of the ruined walls of the ancient castle at Tiberias and looked upon the desolation around me, I tried to conceive of the days of Christ, when he and his disciples traveled through the numerous towns and villages situated on the shore of this beautiful lake, teaching the plan of life and salvation to the inhabitants. There are no prophets and Apostles in this land now. The voice of inspired men has not been heard for many generations, save on a few occasions during the present century when elders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have visited Palestine, and then, like myself, they have had no real opportunity of teaching the people the gospel in its purity.

But while I sighed over the great change which had taken place both physically and spiritually in this once-favored land, I felt truly thankful to the God of Israel that I could think of some other country far away beyond the broad expanse of the “great sea” and the Atlantic Ocean where the inspired teachings of prophets and Apostles are still heard, and where the ordinances of the everlasting gospel are being taught and administered in the same manner and by the same divine authority as they were eighteen hundred years ago, around the beautiful Sea of Galilee.

—Andrew Jenson [1]

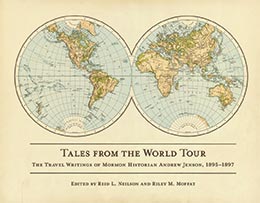

Palestine, The Times Atlas (London: Times, 1895), 75

“Jenson’s Travels,” June 27, 1896 [2]

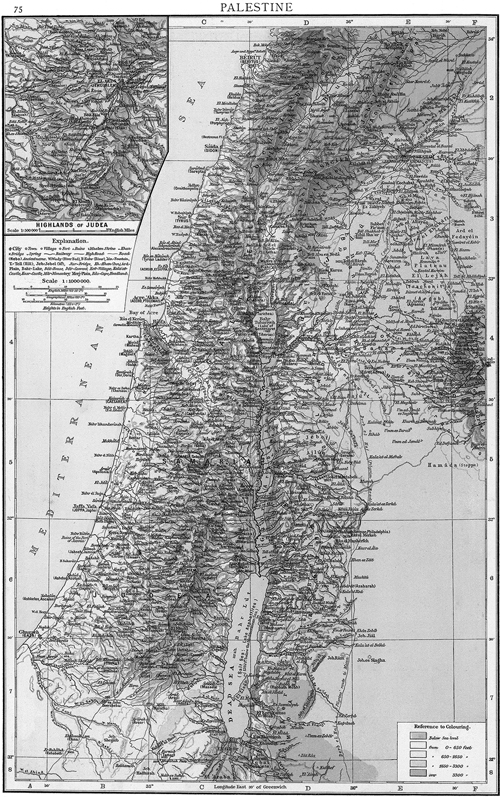

Saturday, June 27. After lying at anchor for about four hours of[f] Tyre, we resumed our journey soon after midnight, and at 4:30 a.m. anchor was cast off Haifa, after sailing 87 miles from Beirut and 35 miles by sea from Tyre. Haifa, situated at the foot and on the north slope of Mount Carmel, appeared most picturesque and pleasing to the eye, as one approaches it from the seaside. At 5:15 a.m. I landed and walked about half a mile to the German colony, where I had no difficulty in finding the only family of Saints residing here, namely Jacob Hilt and wife, with whom the elders from Zion, when visiting Haifa, have made their home of late; here I also met Johann George Grau, who has been in Utah, from whence he came with a missionary license but is now attending to temporal duties connected with his property in Haifa. He lost his wife several years ago. Sister Caroline Hilt and Sister Christine F. Kegel are the only two other Saints in Haifa, making five members altogether. Of the twenty-three persons baptized in Palestine since the mission was first opened up here in 1886, ten have emigrated to Zion, four have died, two are now living at Yafa and four in Haifa, besides Brother Grau who has returned; two have removed to Alexandria, Egypt, and one to Malta. Though neither of the five members in Haifa could talk or understand English, I got along with them remarkably well, my very limited knowledge of German again doing excellent service. Brother and Sister Hilt made me welcome to their hospitality—something that I appreciated highly, as they were the first Saints I had met with since leaving Australia. During my stay Mr. Grau was also very attentive to my wants and accompanied me on my short excursions to the different points of interest in and around Haifa.

Haifa is picturesquely situated on the south angle of the Bay of Acre and at the base of Mount Carmel. Between the shore and the mountain is only a narrow strip of land, which is covered with houses, gardens, and, particularly toward the west, with olive trees, and an occasional stately palm. The town itself has considerably increased and has quite outgrown its old walls. It contains about 7,250 inhabitants, including 700 Europeans, among whom are 400 Germans. Half the natives are Muslims; about 2,200 Roman Catholics; 600 Greeks; the remainder Maronite Christians and Jews. There are two mosques and several Christian churches.

Haifa, Palestine and Syria: Handbook for Travellers (Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1898)

Haifa, Palestine and Syria: Handbook for Travellers (Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1898)

Haifa is the Sycamimum of ancient Greek and Roman authors, and in the Talmud both names occur. In 1100 [AD] Haifa was besieged and taken by storm by Tancred, but after the Battle of Hattin it fell into the hands of Saladin. In the eighteenth century, Haifa extended more towards the promontory of Carmel, but it was destroyed by Zahr-el Omar, pasha of Acre, in 1761, after which the new town sprang up further to the east. Since the steamers have been in the habit of touching at Haifa, the town has enjoyed increasing commercial prosperity and has attracted to itself a great share of the trade of Acre. Wheat, maize, sesame, and oil are exported in considerable quantities, and soap is manufactured on a large scale. The harbor, however, is not good, and the steamers have to cast anchor at a considerable distance from the shore.

The German colony dates back to 1869, when the German Templars founded a settlement here. Their clean and neat dwellings, built in European style, situated northwest of Haifa proper, present a pleasant contrast to the dirty houses of the Orientals. The town site is also laid out with taste, and the main street, which reaches clear from the base of Carmel to the sea and is perfectly straight, is one of the finest thoroughfares I have seen in the Orient so far. Shade trees have been planted on each side of the street with much regularity, and flower gardens also abound in front of the houses, nearly all of which are two stories high. Northwest of the town site lies the farming lands of the colony, most of which is well cultivated. Vineyards have been planted by the colonies on the slopes and on the top of Mount Carmel, from which excellent wine is produced. The Templars now number about 240 souls and possess a meetinghouse and a school; the numerous Germans in the colony who are not Templars have also established a school.

After resting myself a short time in the house of Brother and Sister Hilt in the German colony at Haifa, I walked back to the native town, where I saw a carriage starting out with passengers for the town of Acre, situated on the other side of the bay. I immediately secured a seat and rode about twelve miles along the beautiful sandy beach to that most interesting and historic place. Between Haifa and Acre, and not far from the former place, we crossed the brook Kishon, of Bible fame. The beach is strewn with beautiful shells, and among them are still found the Murex brandaris and Murex trumculus, the prickly shells of the fish which in ancient times yielded the far-famed Tyrian purple. The Phoenicians obtained the precious dye from a vessel in the throat of the fish. The place where these fish were most plentiful was the river Belus, now called Nahr N’aman, which puts into the sea a short distance south of Acre and which we crossed just before we entered the town. The historian Pliny asserts that glass was made from the fine sand of this river, and according to Josephus, a large monument of Memon once stood on its banks. Beyond the river inland rises the hill on which Napoleon Bonaparte planted his batteries in 1799.

We arrived at Acre at 9:00 a.m., and after rambling through the town for some time alone, I came across an Arabian youth from Nazareth by the name of Nami Nucho, who for his own pleasure, as he said, accompanied me to every point of interest in the place. He spoke good English and was anxious to obtain a more thorough English education.

Acre is almost thirty miles south of Tyre and twelve north of Mount Carmel. The town, the key of Syria, is more strongly fortified than any other in the country. The appearance of its defenses is still very formidable, notwithstanding all the vicissitudes of war which it has survived. It stands on an angular promontory jutting into the sea. The walls are in many places double; and those on the land side are protected by strong outworks of mounds with facings of stone. Ages after Acre has flourished, with alternate peace and war. It was the stronghold of the Crusaders, and was besieged by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1799. In 1832 it sustained a siege of six months against Harhim Pasha, during which 35,000 shells were thrown into it. Again in 1840, it was bombarded by the united fleets of England, Austria, and Turkey, and was reduced by the explosion of the powder magazine by which 2,000 soldiers were hurried into eternity without a moment’s warning. [In biblical history Acre is mentioned in connection with the tribe of Asher (Judges 1:31) and with the travels of the Apostle Paul, who on one of his journeys to Jerusalem called there (Acts 21:7). The place in the days of Christ was called Ptolemais.] [3] Acre of the present time contains about 10,000 inhabitants, of whom 8,000 are Muslims. The only gate is on the east side, and no buildings are permitted to be erected outside the walls. The ramparts date in part back to the time of the Crusaders. The wall next to the sea is provided with subterranean magazines, many of which, however, have fallen in. The market of Acre is of some importance, the traffic being centered in a well-covered bazaar. The export trade is considerable, consisting of wheat from the Hauran, rice, oil, cotton, etc., but is gradually being absorbed by Haifa; the harbor is now much choked with sand. A strong guard of Turkish soldiers is stationed here. The town having so often been destroyed by war is almost destitute of antiquities; but one does not tire for a long time looking at its walls and fortifications. From a point of the wall near the sea, where my guide took me, I enjoyed an excellent view of the sea and the country surrounding Acre. Towards the south, Mount Carmel, with the town of Haifa at its base, presents a pleasing picture. To the east, the mountains of Galilee; to the north, beyond the nearer caps of Ras en-Nakura, is seen the Ras el-Abyad, or white promontory, while the lower end of the great plain of Esdraelon stretches from Acre in a southeasterly direction.

Having satisfied myself with my observations in Acre, I walked along the beach back to Haifa, where I arrived very tired and fatigued in the middle of the afternoon. The day was unusually hot and oppressive. Just as I entered Haifa I met a large company of Turkish soldiers starting for the seat of war. Nearly all were mounted on good horses, but their uniforms were shabby and old. I spent the remainder of the day with the Saints at the German colony.

“Jenson’s Travels, June 29, 1896 [4]

Sunday, June 28. I arose early and in company with Elder Johann Georg Grau I walked up to the Latin monastery and lighthouse on the top of Mount Carmel, from which we had a most excellent view of the sea, a small portion of the plain of Sharon to the south, the Bay of Acre to the northeast, and the farming lands, orchards, vineyards, etc., belonging to Haifa, at the foot of Mount Carmel.

Mount Carmel is a noble bluff which juts boldly out into the sea forty miles south of Tyre and about twenty miles west of Nazareth. It forms the Bay of Acre and is the most conspicuous headland upon all this coast of the Mediterranean. From an elevation of 1,500 feet in height, it breaks almost perpendicularly down to the water’s edge, leaving only a narrow pathway around its base to the coast below. The chain to which it belongs runs off in a southeasterly direction across the country, forming the southern limit of the Plain of Esdraelon and the boundary between Samaria and Galilee. Lifting high its head, covered with rich verdure, it greets the distant mariner with a cheerful welcome to the Holy Land, which it guards and adorns so well. Radiant with beauty wherever seen, the “excellency of Carmel” is still to every traveler as much his admiration and his praise as of old it was to the inspired bard. Mount Carmel is particularly noted in Bible history for the exciting scenes of Elijah and the prophets of Baal (1 Kings 18:1–21). The Kishon, where the prophets of Baal were slain, is a fordable stream, fifty or sixty feet wide, which drains the waters of Esdraelon, and empties into the sea at the northern slope of Mount Carmel, about two miles east of Haifa. The highest point of Mount Carmel is 1,910 feet above sea level; the point where the monastery stands has an elevation of 480 feet. The mountain consists of limestone with an admixture of hornstone and possesses a beautiful flora. The rich vegetation of the mountain is due to the proximity of the sea and the heavy dew. As it remains green, even in summer, it forms a refreshing exception to the general aridity of Palestine in the hot season. The original inhabitants regarded the mountain as sacred, and at a very early period it was called the Mount of God (1 Kings 18:19[–20]). The beauty of Carmel is also extolled in the Bible (Isaiah 35:2; Song of Solomon 7:5). It does not seem to have been thickly populated in ancient times but was frequently sought as an asylum by the persecuted (2 Kings 2:25; Amos 9:3). On the west side of the mountain are numerous natural grottos. Some of the hermits’ grottos still contain Greek inscriptions. In the twelfth century the hermits began to be regarded as a distinct order, which in 1207 [AD] was organized by Pope Honorius III. In 1238 [AD] some of these Carmelites removed to Europe. In 1252 [AD] the monastery was visited by St. Louis. Since then the monks have frequently been ill treated. In 1291[AD] many of them were killed; and the same was the case in 1635, when the church was converted into a mosque. Afterwards, however, the monks regained their footing on the mountain. In 1775 the church and monastery were plundered. When Napoleon besieged Acre in 1799, the monastery was used by the Franks as a hospital. After Napoleon’s retreat, the wounded were murdered by the Turks and are buried under a small pyramid outside the gate of the monastery. In 1821, on the occasion of the Greek revolt, Abdallah, pasha of Acre, caused the church and monastery to be entirely destroyed under the pretext that the monks might be expected to favor the enemies of the Turks. But the present new buildings were soon afterwards erected. At present there are about twenty monks in the monastery. The church which forms a part of the monastery buildings is built in the modern Italian style. Below the high altar, which we were permitted to see, is a grotto, to which five steps descend and where Elijah the prophet is said once to have dwelt. The spot is revered by both Christians and Muslims.

Descending to the plain north of the mountain, we visited the so-called School of the Prophets, consisting of a large cavern, partly artificial, in which the holy family is said to have reposed in returning from Egypt. The walls of the cavern, which is a favorite resting place for both Christians and Muslims, are covered with names of pilgrims.

On our way to the colony, we visited the fine German graveyard in which lie the earthly remains of two of our elders from Zion, who died while in the discharge of their duties as missionaries in Palestine. The monuments, almost like, were erected over their resting places recently. Each consists of a marble shaft, broken off at the top, resting upon a square pedestal of grey sandstone. A marble plate containing the inscription is encased on the front side of the pedestal. On one I read:

“In fond remembrance of John A. Clark, son of Ezra and Susan Clark, born February 28, 1871, at Farmington, Utah, USA; died February 8, 1895, at Haifa, Palestine. A missionary of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.”

The German inscription on the other monument read as follows:

“Adolf Haag, von Payson, Utah, USA, geb. 19 Febr., 1865, in Stuttgart, Deutschland. gest. 3. Oct., 1892, in Haifa, Palastina. Ein Missionar der Kirche Jesu Christi der Heiligen der letzten Tage.”

The two graves are only sixteen feet apart. Besides the monuments each grave is enclosed with a neat frame of sandstone; and the flowers and shrubs growing on them show that some friendly hand is engaged at times in bestowing the necessary attention for proper preservation.

After our return to the house of Brother Hilt, we held a little meeting, at which we partook of the sacrament and bore testimony. I addressed the congregation in a manner hitherto unknown in all my missionary experience; but I was understood; for the Spirit of God rested upon us and caused our hearts to rejoice and ours souls to be drawn together in the love of the gospel of Jesus Christ. There were only five of us present, as Seded Kegel, one of the members, did not attend. In the afternoon, accompanied by Elder Grau and Seded Magdalina Hilt, I paid another visit to the graveyard, for the purpose of taking snapshot with my Kodak. We spent the evening singing German and English hymns; and thus I spent my first Sunday in Palestine.

Monday, June 29. After breakfast I visited Sister Kegel, a widow 75 years old, and Sister Caroline Hilt, after which I spent most of the day writing. Toward evening Elder Grau accompanied me to the sanitarium and hotel on the top of Mount Carmel, just behind the German colony, about two miles away. From the sanitarium, which has a healthy and romantic situation about 900 feet above sea level, a road leads off in a southeasterly direction along the ridge or summit of the mountain to El-Muhraqa—the place of burning—which is the southeast point of Mount Carmel. On the summit is a little Latin chapel, and a little lower toward the east, hidden in the wood, are ruins, possibly the remains of an old castle. This spot is said to have been the scene of the slaughter of the prophets of Baal (1 Kings 18:40).

“Jenson’s Travels,” July 1, 1896 [5]

Tuesday, June 30. After arranging for my transportation to Nazareth and administering to Brother Grau, who was sick, I took an affectionate leave of the Saints at Haifa, and started at 1:00 p.m. as a passenger in a carriage for Nazareth, about 23½ miles distant in a southeasterly direction. Though the heat in the middle of the day was oppressive indeed, I enjoyed the ride very much. Our route lay along the base of Mt. Carmel, and thence across the plain of Kishon, which really is the lower end of the great Plain of Esdraelon. We forded the Kishon about ten miles from Haifa and then crossed a low range of hills covered with oak forests to the Plain of Esdraelon proper. We stopped to rest and drink at a beautiful spring, situated by a fine orchard, which was surrounded by an enormous cactus fence. Continuing our journey, we entered the hill-lands of Galilee, and from the top of the ridge beyond Mujedil we had our first view of Mount Tabor and also the mountains of Bashan beyond the Jordan River. Soon afterward we passed on our left the village of Yafa, the Japhia of Joshua 19:12, situated on a lofty hill; and after reaching the top of another hill the town of Nazareth suddenly came into view; but as the sun had already disappeared beyond the distant height of Mount Carmel and it was getting somewhat dark, the impression on the mind was perhaps not so complete as it otherwise might have been. Still, as it was, the first sight of that historic town where our Savior spent the greater portion of his life on earth produced an effect upon me which I shall never forget. We soon reached the lower end of the town, where I put up at a neat little hotel kept by a German, who treated me kindly and who subsequently arranged for my transportation to Jerusalem.

Wednesday, July 1. I left the hotel in the outskirts of Nazareth at 5:00 a.m. and took a walk through the heart of the town. At Mary’s Well I turned off to the right and then struck out on foot for Mount Tabor, distant about six miles in a southeasterly direction. By following Baedeker’s guide too closely, or perhaps not close enough, I got on the wrong trail, which brought me in a roundabout way to the east base of Mount Tabor into the midst of a Bedouin camping ground. Determined to reach the top of the mountain, where the monastery buildings appeared in plain sight, I struck out cross lots over rocks, valleys, and groves of timber but had not gone far when I met a big and vicious-looking Bedouin, armed with a gun, who placed himself in the path before me and demanded “baksheesh” (money). Assuming the attitude of not understanding him, I darted past him, having my eye on a pile of cobblestones near by; but as he did not follow, I had no occasion to arm for self-protection with rocks. At length I reached the path leading up the mountainside and finally reached the top with tired limbs and parched lips, almost dying for the want of water. I made my way straight to the Latin monastery, where nothing greeted me at first but a horde of ugly-looking barking dogs, which made music for me while I was helping myself to a drink of water from the monastery well. At length a friendly monk appeared, who, after treating me to a drink of pure Palestine wine, took me around and showed me the ruins crowning the summit of the mountain and other objects of interest. He then conducted me into an apartment where the monks entertain their visitors. There I enjoyed a refreshing sleep and did not awake till a servant, a Canadian-Frenchman, who could speak a little English, called me to dinner, which was prepared for me in an adjoining room.

Mount Tabor (2,018 feet above the level of the sea) is called Jebel el Tor by the Arabs. When seen from the southwest, it has the form of a dome, but from the northwest that of a truncated cone. The slopes of the hill are wooded. Oaks formerly covered the summit, but most of them have been felled by the Greek and Latin monks. Partridges, hares, foxes, and various other kinds of game abound. The ruins on the mount belong to several different periods. The substructions of the wall inclosing the summit, and forming a plateau of about four square miles, consists of large blocks, some of which, particularly on the southeast side, are drafted and are at least as old as the Roman period. The castle which occupied the highest part of the plateau dates from the Middle Ages and is now a large and shapeless heap of cut stones. Within the Latin monastery are still to be seen the ruins of a Crusaders’ church of the twelfth century, consisting of a nave and aisles and three chapels in memory of the three tabernacles which the Apostle Peter wished to build. The Greeks and Latins differ here, as in many other places, as to the actual spot where the Transfiguration took place, each claiming it to be within their own church.

The view from Mount Tabor is very extensive. To the east the north end of the Lake of Tiberias is visible, and in the extreme distance the blue chain of the mountains of the Hauran in ancient Bashan. To the east of the lake is the deep gap of the Yarmuk Valley. Toward the south on the slope of Jebel Dahi lie Endor, Nain, and other villages. Toward the southwest can be seen the battlefield of Barak and Sisera; to the west rises Mt. Carmel, which, together with several ranges of hills, almost entirely shut out the view of the sea. To the north rise the hills of Ez-Zerbud and Jermaq, near which is the mountain town of Safed. Above all presides majestic Harmon, on the top of which I still noticed some of last winter’s snow.

Mount Tabor has a long history. It was on the boundary line between Isaachar and Zebulon. It was here that Deborah directed Barak to assemble an army, and from hence the Israelites marched into the plain and defeated Sisera (Judges 4). In the Psalms, Tabor and Hermon are extolled together (Psalms 89:12). The hill was afterwards called Itabyrion or Atabyrion. In the year BC 218, Antiochus the Great founded a town of the same name on the top of the hill. In AD 53, a battle took place here between the Romans under Gabinins and the Jews. Josephus afterwards caused the place to be fortified and the plateau on the top to be enclosed by a wall. Origen and Jerome speak of Mt. Tabor as the scene of the Transfiguration (Mark 9:2–10); but many critics claim that this could hardly have been the case, as the top was covered with houses at the time of Christ. The legend, however, attached itself to this, the most conspicuous mountain in Galilee, and as early as the sixth century three churches had been erected here in memory of the three tabernacles which St. Peter proposed to make. The Crusaders also erected a church and a monastery on Mt. Tabor, but these suffered much during the wars with the Muslims. In Mt. Tabor, but these suffered much [6] el-Adil, the brother and successor of Saladin. Five years later this fortress was unsuccessfully besieged by the Christians. It was afterwards dismantled by the Muslims themselves, and the church was destroyed. The two monasteries, one Greek and the other Latin, which now occupy the top of the hill, are comparatively modern.

After resting and refreshing myself at the Latin monastery on Mt. Tabor for about five hours, I decided to continue my walk to Tiberias, instead of returning to Nazareth. Accordingly, at 2 p.m. I left my friends, the monks, and commenced descending the northeast slope of the mountain without following road or path. I reached the base without accident and then struck across the country in a northeasterly direction to Khan-al-Tujjar, where I found good water to drink. Continuing the journey, I passed the village of Kfar Kama, situated on high ground on the right of the path, and also met a number of caravans coming in from the desert beyond the Jordan. After descending a deep basin, I met some traveling Bedouins, who accosted me as if bent on mischief and made the usual demand for baksheesh without getting away. They made a terrible noise, and for awhile it looked as if they were determined to make me a prisoner, but they didn’t; and after that I was troubled with nothing but tired limbs.

I found that my climbing experiences on Mount Tabor had drawn very heavily on my physical strength, and before I reached the top of the plateau called by the Arabs Ard-el-Hamma, which overlooks the Sea of Galilee, I was almost give out, and my thirst knew no bounds. But the lovely view, which I enjoyed as I sat down to rest on the brow of the hill overlooking the beautiful lake about 1,100 feet below, made me partly forget my exhausted condition for the time being. It was now after sundown, and as I had been warned of the dangers of being out alone in the night in a Bedouin country, I proceeded to descend the steep incline and finally reached the town of Tiberias, situated on the lakeshore, at 9:00 p.m. After some little difficulty I found the only hotel in the place and retired at once, being too tired to eat supper. During the day I had walked about 25 miles, on account of my roundabout course. Otherwise, the distance from Nazareth by way of Mt. Tabor to Tiberias is only about eighteen miles.

After this day’s experience I decided not to undertake any more excursions on foot during my sojourn in Palestine. To venture out alone like I did through a country inhabited partly by roving and hostile Bedouins is fraught with considerable danger; and though a servant of the Lord has a claim upon the preserving care of his Master, he should not unnecessarily expose his life or property. And besides this, walking in a semitropical land in the heat of summer is altogether different to the same kind of exercise in a more temperate clime and a cooler part of the season.

In making my usual arrangements for stopping at the hotel in Tiberias, I was somewhat amused at the look with which my Arabian host surveyed me when I told him that I was a missionary without much money and would like him to give me his lowest terms. “A missionary without much money,” he repeated after me. “That certainly sounds strange; for missionaries are always supposed to have plenty of money.” Had I told him that I was a banker or merchant with only little money I believe he would have been less surprised. And who can blame him, for the priests and pastors, missionaries and colporters of the various so-called Christian denominations in Palestine are considered the best-paid people in the land. They generally live in pompous style and in elegant homes, having lots of native servants to wait on them—all on the strength of the liberal donations which pious Christians in Europe and America are contributing toward the relief of the “poor suffering Jews.” And when they travel they can afford always to go first class, and live on the fat of the land. Consequently it was something like a new revelation when I told my Arab host about missionaries who travel without purse or scrip, or at least on their own expenses. He, however, gave me the reduction asked for and treated me with kindness.

“Jenson’s Travels,” July 3, 1896 [7]

Thursday, July 2. Feeling somewhat rested, I arose quite early in order to take in the sights in and around Tiberias. My first number on the program was a short sail on the Sea of Galilee, being careful to make proper contract in regard to time and amount to be paid. For these Arab boatmen have the audacity to make the most extortionate charges of tourists for a sail on the lake. One traveler, an Irish pilgrim who visited the Sea of Galilee some time ago, engaged an Arab to take him across the lake without agreeing about the price beforehand. On returning in the evening the villainous native demanded $10 for his day’s work. “Ten dollars,” repeated the astounded Irishman! “By the h— v—, it is no wonder that Jesus walked.”

I truly enjoyed my short boat ride on the historic lake, and by my request the boatmen landed me a short distance south of the town from where I walked to the hot springs situated on the lake shore, about one and a half miles south of Tiberias. A short distance beyond these springs, around a point, I took a refreshing bath and swam in the clear waters of the lake, after which I returned to the town, walked around its walls, ascended the ruins of the old castle situated immediately north of the town, and walked through the principal streets, the bazaar, etc. I also took a walk along the lakeshore gathering shells and small stones to carry away with me. When finally night came, I chose to sit up in a chair on the hotel porch rather than submit to a repetition of the experience of the previous night, when the unmerciful fleas perpetrated such outrages upon my person that I looked a complete smallpox patient in the morning.

The Sea of Galilee, also called the Lake of Tiberias, which is the scene of so many incidents connected with our Savior’s ministry, lies in a deep valley encircles by mountains, which rise on the east from the water’s edge by steep acclivities, until they reach the height of a thousand or twelve hundred feet. On the west, and especially in the northwest, the hills are lower and more broken. Occasionally they recede a little from the shore and form small plains of great fertility. The greatest length of the lake is thirteen miles and six broad; the waters are pure and limpid and abound with fish as in the days of the Savior. From its position between high hills it is exposed to sudden gusts of wind. The rocks bordering the lake are mostly limestone, and the whole region volcanic. Near Tiberias, on the southwest shore of the lake, are several hot springs, and on the opposite side several others at a short distance from the shore. The opinion has been advanced by some that the lake itself occupies the crater of an extinct volcano. The surface of the lake, according to the last surveys, is 680 feet below the level of the Mediterranean; its depth is from 154 to 230 feet, and in the north as much as 820 feet. The height of the water, however, varies with the seasons. We learn from the Gospels that the lake was once navigated by numerous vessels, but there are now a few fishing boats only.

Tiberias, mentioned in John 6:23, is the only town on the lake at the present time. The city of Tiberias, so renowned in history, was built by Herod Antipas, by whose order John the Baptist was beheaded, and is supposed to have been one of his residences. It is now mostly in ruins. The terrible earthquake of January 1, 1837, seriously damaged the walls and houses, causing the death of about one-half of the population. Of the 4,000 inhabitants who reside here at present about two-thirds are Jews, nearly 1,200 are Muslims, 200 orthodox Greeks, and a few Latins and Protestants. Nearly all of the inhabitants are poor and sickly. Some travelers describe Tiberias as the most wretched of all the towns in Palestine.

It lies directly upon the shore on a narrow strip of undulating land, beyond which the mountains rise very steeply. Near the celebrated hot springs are found various fragments of columns of red and gray granite and marble, together with other indications which mark the sight of the ancient town. The water flows from the earth too hot to be borne by the hand, and it is excessively salt and bitter and emits a strong smell of sulfur.

The heat of the summer at Tiberias, as at Jericho, is almost insupportable, and the climate sickly. The inhabitants of the coast find profitable employment in raising early vegetables, grapes, and melons for the markets of Damascus. These productions mature in this valley much earlier than on the high land of Galilee or Gilead. The scenery of the lake has not the stern and awful features of the Dead Sea, but is more rich in hallowed associations and more attractive in the softened beauties of the landscape. The view of it from the western height, when I last saw it, breaks upon the approaching traveler with singular power.

Near the northern extremity of the lake there were in the days of the Savior two towns of the name of Bethsaida; one is in the neighborhood of Capernaum and Chorazin, on the west side of the lake; the other, on the eastern shore. The situation of the former, which was the city of Peter and Andrew and which was involved in the doom of Capernaum and Chorazin, is lost; the latter, mentioned by Luke (9:10), near which Jesus fed the five thousand, was enlarged by Philip the Tetrach. The ruins of it are just beyond a small plain of surpassing fertility, at the distance of a little more than an hour’s journey beyond the Jordan, where it enters into the lake. They occupy a knoll, or hill, which is a spur from the mountain on the east, running down into the plain toward the Jordan. After feeding the five thousand, Jesus ordered His disciples to cross over into the other Bethsaida on the western shore, which he went up into the eastern mountain to pray. It was while crossing the lake on that occasion that a storm struck their little craft, and that Jesus, who had been asleep, rebuked the wind (Matthew 8:18–27). Modern Bible students, however, disclaim the theory of two Bethsaidas, and assert that there never was but one place of that name.

As I sat alone upon the top of the ruined walls of the ancient castle at Tiberias and looked upon the desolation around me, I tried to conceive of the days of Christ, when he and his disciples traveled through the numerous towns and villages situated on the shore of this beautiful lake, teaching the plan of life and salvation to the inhabitants. There are no prophets and Apostles in this land now. The voice of inspired men have not been heard for many generations, save on a few occasions during the present century when elders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have visited Palestine, and then, like myself, they have had no real opportunity of teaching the people the gospel in its purity.

But while I sighed over the great change which had taken place both physically and spiritually in this once-favored land, I felt truly thankful to the God of Israel that I could think of some other country far away beyond the broad expanse of the “great sea” and the Atlantic Ocean where the inspired teachings of prophets and Apostles are still heard, and where the ordinances of the everlasting gospel are being taught and administered in the same manner and by the same divine authority as they were eighteen hundred years ago, around the beautiful Sea of Galilee.

Friday, July 3. After several fruitless endeavors the day before to get a muleteer on reasonable terms to take me back to Nazareth, I at last obtained one by waking up the hotel servant in the middle of the night. About 4:00 a.m., just at the break of day, an Arab with a grey horse appeared at the hotel door; and I, being in readiness, mounted at once, and started on my return trip to Nazareth, but taking a more northerly route than the one leading past Mount Tabor. After climbing the long hill we traveled through a broken country to the village of Lubiya, which lies on a hill of considerable height. Immediately north of the village, in a narrow valley, we passed a great number of the inhabitants, both men and women, engaged in harvesting barley in real oriental fashion. Every village has its common threshing floor, and in every town through which I have passed so far in Palestine some of the people have been engaged in threshing grain in ancient fashion. My muleteer falling behind, as he was walking, and the animal I rode was a good traveler, I took the wrong road; and before the native could overtake me I had reached the little village of Tur’an, situated on the north boundary of the Plain of Battuf and surrounded by a greater growth of cactus than I have ever seen up to date in any part of the world. Nearby, however, there are some fine olive groves. Changing our course we now crossed the valley, or plain, mentioned in a southwesterly direction, in doing which I saw the longest caravan that I had seen yet. There were over seventy-five camels traveling in a string nearly a mile long from the sea inland. We soon reached Kefr Kanna, the ancient Cana in Galilee, where Jesus changed water to wine. Here I visited the Greek church where the hypocritical-looking priest showed me, among other things, one of the earthenware jars claimed to have been used at the time of the miracle (John 2:1–11). There were also a number of beautiful pictures of the church walls illustrative of Bible scenes. Cana is about four miles northeast of Nazareth and lies between the lower hills bordering the Plain of Battuf on the south. It has about six hundred inhabitants, half of whom are Muslims and the remainder mostly Greek Christians with a few Latins and Protestants. Immediately south of the village is the only spring of the neighborhood, from which I drank water and by which we rested for a short time. If the Kefr Kanna really is the ancient Cana, the tradition alleging that from this spring was obtained the water which Christ turned into wine is undoubtedly correct.

From Kefr Kanna, the road leads up among the hills, and after crossing several ridges and passing several villages we reached Nazareth about 11:30 a.m. Among the villages named between Cana and Nazareth was Mash’had, the ancient Gath-Hepher, a town in the territory of Zebulon and the birthplace of the prophet Jonah (2 Kings 14:25). The tomb of that prophet is shown here.

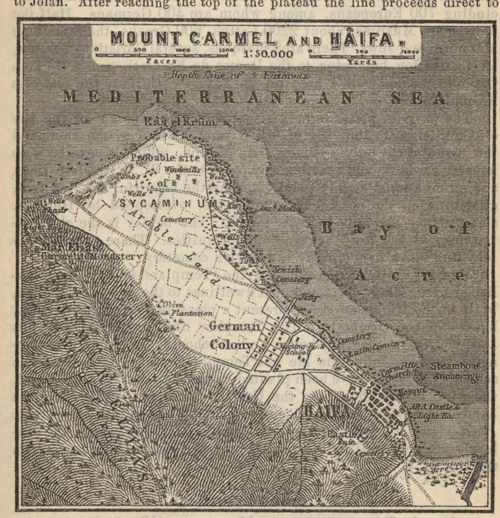

On my arrival in Nazareth I dismissed my muleteer, after which I spent the afternoon taking in the sights of that town. First, I visited the Latin monastery, in which the Church of the Annunciation is situated. It contains several altars, one of which is dedicated to the angel Gabriel. A handsome flight of fifteen marble steps descends to a vestibule called the angel’s chapel. From here a passage leads to the Chapel of the Annunciation, to which two steps descend. The chapel was originally larger than the angel’s chapel but is now divided by a wall into two parts, the first of which contains the altar of the Annunciation with the inscription on the back: “Hic verbum caro factum est.” (“Here the word was made flesh.”) Immediately to the left of the entrance are two columns, one of which marks the place where the angel stood, while one and one-half feet distant is the column of Mary. It is really a fragment of a column descending from the ceiling and said to be miraculously supported above the spot where the Virgin received the angel’s message. On the rock here, which is now richly overlaid with marble, the House of the Virgin is said to have stood. Adjoining this chapel is a second dark chamber called the Chapel of St. Joseph, which contains an altar bearing the inscription: “Hic erat subditus illis.” (“Here he became subject to them.”) From this chamber a staircase leads into the monastery; but on the way is still another dark chamber—an old cistern called the Kitchen of the Virgin, the mouth of which is said to be the chimney. A kind, German-speaking monk took me through the whole and explained all to me.

Nazareth, Palestine and Syria: Handbook for Travellers (1989)

Nazareth, Palestine and Syria: Handbook for Travellers (1989)

I next visited the United Greek church, where I was shown an old synagogue, in which tradition alleges that Christ preached. This tradition is traceable as far back as the year AD 570. The building has experienced many vicissitudes. In the thirteenth century it was converted into a church and has had different situations at different periods. My next visit was to the Church of Gabriel, or the Church of the Annunciation of the Orthodox Greek, which is partly underground. Under the altar is a well connected with a spring situated north of the church, which spring is the supply source of Mary’s Well nearby. Greek pilgrims use the water drawn up by the priestly attendant from under the altar for bathing their eyes and heads; but, being thirsty, I drank with great relish the cup offered me. One of the priests, after being told that I was from America, asked me if I was a Mormon. Receiving a reply in the affirmative, he held a consultation with several of his fellow priests, the substance of which I never learned. But he must have met some of our elders before. Though he spoke Greek and I English, we managed to exchange views on different points, among which the mode of baptism by immersion, which the Greeks have always maintained as the proper mode. He seemed pleased when I made him understand that I also believed in that form and condemned sprinkling as being no baptism at all. A large and rather richly embellished baptismal font which I examined with considerable interest gave occasion for their remarks.

St. Mary’s Well situated near the Church of Gabriel supplies the whole town with water. The spring is also known as Jesus’ Spring and Gabriel’s Spring, and a number of different traditions are connected with it. As this is the only spring that the town possesses, it is all but certain that the child Jesus and his mother were once among its regular frequenters. Toward evening, which was the time I visited the well, a motley throng, mostly women, had collected around the spring waiting for their turn to get water. The water is brought in a conduit from the spring some distance up the hill to the forks of the road, where an arch of masonry has been built, from the front of which the water flows regularly in two small streams through pipes placed sufficiently high up in the wall for the jars or water vessels to be placed under them for filling. It was very interesting to me to watch the women, some of whom were really good looking, coming and going, carrying their water vessels on their heads, just as I used to see it illustrated in family Bibles when I was a boy. Thus the interest of the scene was greatly enhanced by the thought that it was probably very similar to that which might have been witnessed in the same place upwards of eighteen centuries ago.

From St. Mary’s Well I returned to the Latin monastery, from where a servant with keys accompanied me to the house or workshop of Joseph, where stands a little chapel built in 1858–59. The tradition to the effect that this is the spot where Joseph had his workshop dates from the beginning of the seventeenth century. The Franciscan monks obtained possession of this spot in the middle of last century.

Next we crossed the market and proceeded to a Latin chapel situated on the west side of the town, in which is shown the so-called table of Christ. It consists of a block of hard chalk, 11½ feet long and 9½ feet broad, on which Christ is said to have dined with His disciples both before and after the Resurrection. The tradition is not traceable further back than the seventeenth century; hence is not believed in by any except the Latins and perhaps not conscientiously even by them. Last of all I visited the Protestant church.

Nazareth is not mentioned in the Old Testament at all, and in the time of our Lord it was an unimportant village in Galilee (John 1:46). The name of Nazarene was applied as an epithet of derision, first to Christ Himself and then to His disciples (Matthew 2:23; Acts 24:5). The Oriental Christians call themselves Nasara.

The name of the place is also preserved in the modern name of En-Nasirah. The first historians who mention the town are Eusebius and Jerome. Down to the time of Constantine, Samaritan Jews only occupied the village. About the year AD 600, a large basilica stood here; but the bishopric was not yet founded. In consequence of the Muslim conquest, Nazareth again dwindled down to a mere village. In 970 it was taken by the Greek emperor, Zimisces, but before it came into the possession of the Franks it was destroyed by the Arabs. It came into the possession of the Franks as a fief. The Crusaders afterwards erected churches here, and transferred hither the bishopric of Scythopolis. After the Battle of Hattin, Saladin took possession of Nazareth in July 1187. In the Middle Ages, Nazareth was much visited by pilgrims. In 1229 the Emperor Frederick II rebuilt the place, and in 1250 it was visited by Louis IX of France. When the Franks were finally driven out of Palestine, Nazareth lost much of its importance. After the conquest of Palestine by the Turks in 1517, the Christians were compelled to leave the place. At length, in 1620, the Franciscans, aided by the powerful Druse chief, Fakhreddin, established themselves at Nazareth, and the place began to regain its former importance, though still a poor village and frequently harassed by the quarrels of the Arab chiefs and the predatory attacks of the Bedouins. In the middle of the eighteenth century, the place recovered a share of its former prosperity under the Arab sheikh, Zahr el-Amr. In 1799 the French encamped near Nazareth.

The modern Nazareth (En-Nasira, in Arabic) is situated in a basin on the south slope of the Jebel el Sheikh, a hill of considerable height and of lime formation. The appearance of the little town, especially in spring when its dazzling white walls are embosomed in a green framework of cactus hedges, fig and olive trees is very pleasing. The population numbers about 7,500 souls, namely, 1,850 Muslims; 2,900 Orthodox Greeks; 950 United Greeks; 1,350 Latins; 250 Maronites; and 200 Protestants. Most of the inhabitants are engaged in farming and gardening, and some of them in handicrafts and in the cotton and grain trade. The inhabitants are noted for their turbulent disposition. Many pretty women are to be seen. The district is comparatively rich, and the Christian farmers have retained many peculiarities of custom, which are best observed at weddings. On festivals the women wear gay, embroidered jackets and have their foreheads and breasts laden with coins, while the riding camel, which forms an indispensable feature in such a procession, is smartly caparisoned with shawls and strings of coins.

Nazareth to all Christians is the most interesting town in Galilee. It is the seat of the kaimakam, and the chief town of a district.

“Galilee, after the captivity,” writes Lyman Coleman, in his Historical Text Book and Atlas of Biblical Geography, “had been settled by a mixed race of foreigners and Jews. Two great caravan routes passed through this country, one from the Euphrates through Damascus to Egypt, and one from the same regions to the coast of the Mediterranean. It was also near the great centers of trade and commerce on the Mediterranean, at Tyre and Sidon, which in the days of Christ were still cities of considerable trade, and at the more modern city of Ptolemais, Acre.

“The northern part of Galilee, comprising the hill country north of the Plain of Esdraelon, was, in the days of Christ, termed heathen Galilee, or Galilee of the Gentiles (Matthew 4:15), because among the Jewish population there were intermingled many foreigners such as Phoenicians, Syrians, Greeks, and Arabs.

“From their intercourse and admixture with foreigners, the Galileans had acquired a strong provincial character and dialect, which made them particularly obnoxious to the Jews. Their language had become corrupted by foreign idioms so as to betray them as was charged upon Peter (Matthew 26:73; Mark 14:70). For the same general reasons the Galileans were less bigoted than the Jews of Judea, and more tolerant toward Christ as an apparent innovator of their religion. He accordingly passed the greater part of his public ministry, as well as of his private life, in Galilee and chose his disciples from this country, where his miracles and instructions excited less hostility than at Jerusalem.

“Josephus expatiates at length on the extreme fertility of Galilee, and all travelers confirm his representations. In proof of its populousness, it is related by Josephus that here were in this country comprising scarcely thirty miles square, 200 towns and villages, each containing 15,000 inhabitants, He, himself, in a short time, raised 100,000 volunteers for the war against the Romans. ‘Surrounded,’ he adds, ‘by so many foreigners, the Galileans were never backward in warlike enterprises, or in supplying men for the defense of the country. They were numerous and accustomed to war from their infancy.’” [8]

“Jenson’s Travels” [9]

Saturday, July 4. I ascended the hill called Jebel el Sheikh, standing back of Nazareth northwest. From the top of a tomb known as Neby-Sain, which stands on this height 1,600 feet above the level of the sea, the view is simply grand. It commands a complete survey of the little valley in which Nazareth lies. Over the lower mountains to the east peeps the green and partly cultivated Mt. Tabor, to the south of which are the Nebi Dahi (Little Hermon), the villages Endor, Nein, and Zerin and a great part of the Plain of Esdraelon (as far as Jenin). To the northwest Mt. Carmel projects into the sea, to the north of which is the Bay of Acre, the town itself being concealed by intervening hills. To the north stretches the beautiful valley, or plain, of El-Battuf, at the south end of which rises the ruins of Saffuriya; to the northeast is seen Safad on an eminence, in the midst of confused ranges of hills, beyond which rises the majestic Mt. Hermon. To the east beyond the Sea of Galilee are the distant hills of Golan.

At 2:30 p.m. I left Nazareth on horseback, accompanied by an Arab muleteer on foot, and commenced my overland journey to Jerusalem. We descended the hills on a very rocky and steep path to the Plain of Esdraelon below, meeting on our way ever so many camels and donkeys laden with grain in the sheaves from the harvest fields on the plain. Their destination was Nazareth. After reaching the plain we took a southerly direction, passing to the right of and within easy view of the villages of Nein, where Jesus raised the daughter of Jairus (Luke 7:11–15), and Zerin, the ancient Jezreel. We also passed to the right of Little Hermon, called Nebi Dahi in Arabic tongue, and Gilboa (Jebel Fuqua). Directly on our route were the villages of Afula and Mukebelch, while both on our right and left numerous other villages were seen on the great plain. We arrived at Jenin, about twenty miles from Nazareth, a little after sundown, and I put up for the night Dr. Nasif Kawar, a Syrian who could talk English. He treated me kindly, felt greatly interested, so he said, in our conversation, and charged me nothing direct for stopping with him. The servants, however, did not forget their baksheesh.

The great Plain of Esdraelon is twenty miles long from east to west and from eight to twelve miles wide. The range of Carmel constitutes its southwestern, and the Bay of Acre its northwestern, boundary. The mountains of Gilboa, Little Hermon, and Tabor define its eastern; but between these it sends off arms down to the valley of the Jordan. This plain presents an undulating surface of great fertility and beauty, which preserves an average level of 400 feet above the sea. For thousands of years it has been the highway of travel and the battlefield of many nations. “No field under heaven,” writes Lyman Coleman, in his Historical Text Book and Atlas of Biblical Geography, “has so often been fattened by the blood of the slain.” It has been the chosen place for encampment in every contest that has been carried on in this country from the days of Deborah and Barak until the disastrous march of Napoleon Bonaparte from Egypt to Syria. Egyptians, Persians, Arabs, Jews, Gentiles, Saracens, Turks, Crusaders, Druses, and French—warriors out of every nation which is under heaven—have pitched their tents upon the Plain of Esdraelon and have beheld their banners wet with the dew of Hermon and Tabor. In the history of the Jews this plain is frequently referred to under the names of Megiddo and Jezreel.

“North of Esdraelon, for thirty miles, are the mountains of Galilee, presenting a confused succession of hills and mountains, which form a country singularly picturesque and beautiful but highly productive.” [10] Beyond the mountains of Galilee rise the lofty ridges of Lebanon, whose peaks often lift their heads into the regions of almost perpetual snow and ice and condense the clouds of heaven and send them off, borne on the cold winds of the mountains to refresh the scorched and thirsty plains which are opened out before them. The headwaters of the Jordan spring from the southern base of Lebanon, which may be termed the great condenser, refrigerator, and fertilizer for the land of Palestine; and in this regard sustains the same position to that land as do the Wasatch Mountains to the valleys of Utah.

The village of Nein lies on the north slope of Little Hermon, about six miles in a straight line southeast of Nazareth, but considerably farther by road. It consists of wretched clay huts. Near it are rock tombs. Between Nain and Nazareth, but much nearer the last-named town, is the so-called Mount of Precipitation, over the perpendicular ledge of which the people of Nazareth were about to throw Christ on a certain occasion.

Nebi Dahi is supposed to be identical with the hill Moreh mentioned in Judges 7:1. It was first called Hermon by St. Jerome and has since been known as Little Hermon; its top is 1,815 feet above sea level. On the southwest slope of Nebi Dahi lies the village of Sulam, which anciently was a town of the tribe of Issachar. The form Sulam is found in the word “Shulamite” (Song of Solomon 6:13). Here, too, probably stood the house of the Shulamite woman (2 Kings 4:8).

Zerin is the ancient Jezreel, a town if Issachar. Close by was the scene of the great battle fought by Saul against the Philistines. The Israelites were posted around Jezreel (1 Samuel 29:1), while the Philistines were encamped at Sulam on the opposite Jebel Dahi. Saul fell here (2 Samuel 1:21). After Saul’s death, Jezreel remained for a long time in possession of his son Ishbosheth (2 Samuel 2:8–9). Jezreel was afterwards the residence of King Ahab and Jezebel. On the vine-clad hill lay the vineyard of Naboth, where Joram, Ahab’s second son, was afterwards slain by Jehu. In the book of Judith, Jezreel is called Esdraelon. In the time of the Crusaders it was mentioned as Parvum Gerinum. The modern town is situated on a northwest spur of the Gilboa Mountains, which forms the watershed between the Mediterranean and the Jordan Basin. The hill on which the town is situated is partly artificial and slopes down on almost every side. There are ancient winepresses on the east and southeast slopes.

The Gilboa Mountains, called by the Arabs Jebel Fuqua, reach an elevation of 1,717 feet above sea level at the highest point. It runs from southeast to northwest. The north side toward the valley of Jezreel is precipitous and stony. On the east lies the Ghor, or Valley of the Jordan. The mountain was anciently included in the territory of Issachar. Though it at present presents a bare appearance and is used as arable and pasturelands, it was probably covered with timber in olden times.

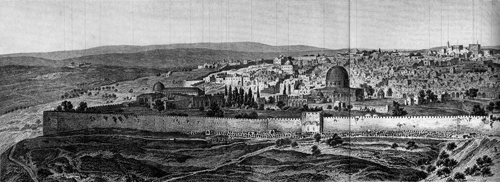

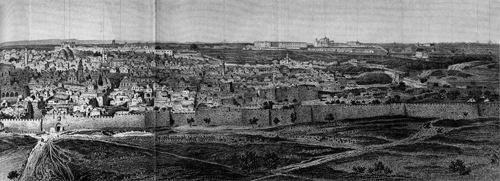

Panorama of Jersualem, Palestine and Syria: Handbook for Travelers (1898)

Panorama of Jersualem, Palestine and Syria: Handbook for Travelers (1898)

Sunday, July 5. We continued our journey from Jenin about sunrise and traveled through a hilly country with small plains and narrow valleys intervening. We also passed through and near several villages, some of which are mentioned in Bible history. A short distance on our right we passed the ruins of the ancient Dothan (Genesis 37:17), for which reason it is still called Jubb Yusuf (Joseph’s Pit). In the time of Elisha a village seems to have stood here (2 Kings 7:13). We met lots of people traveling, some on camels, others on horses, donkeys, and mules, and many on foot. Among the latter were a large number of very dirty-looking and ragged women carrying fuel and other heavy burdens on their heads. The heat during the middle of the day was very oppressive, and my umbrella, which had served as a parasol, burst in several places, thus leaving me exposed to the full powers of the sun. At 11:30 a.m. we arrived at the village of Sebastya, the ancient Samaria, where I viewed the ruined church of St. John, in which Muslim attendants pointed out the tomb of John the Baptist, the tomb of Obadiah (1 Kings 18:3), and the tomb of Elisha, and many other absurdities, all for the purpose of exacting money from pious pilgrims. I also walked through the village to the top of the hill, on the eastern slope of which, just above the village threshing floor, is a dozen or more columns without capitals, forming an oblong quadrangle. They are supposed to be remains of the ancient temple which Herod the Great is said to have erected in honor of Augustus “on a large open space in the middle of the city.” The top of the Samaria hill is 1,542 feet above the level of the sea, which in Isaiah 28:1, is compared to a crown and commands an unobstructed view including the Mediterranean on the west. Samaria is surrounded by ranges of gently sloping hills. Numerous villages are visible, but none of them have any historical significance so far as it is known. On a terrace on the south side of the hill runs the street of columns with which Herod embellished the town. The columns, all of which have lost their capitals, are 16 feet high. The colonnade was about 20 yards wide and over 1,800 yards in length. It runs around the hill, but is often interrupted or is buried beneath the soil. The whole hill, which rises to the height of 330 feet from the surrounding valley, is terraced from base to top, and ruins abound everywhere. The hill stands isolated in the valley.

Samaria was built by Omri, one of the kings of Israel, about 926 years before Christ, and he made it, instead of Tirzah, the capital of the kingdom of Israel. After that the city became distinguished in the history of that kingdom, and of the prophets Elijah and Elisha, in connection with the various famines of the land, the unexpected plenty of Samaria, and the several deliverances of the city from the Syriana. It continued for two hundred years the seat of idolatry and the subject of prophetic denunciations, until the carrying away of the ten tribes into captivity by Shelmaneser. Five hundred years afterwards it was taken by John Hyrcanus and razed to the ground according to words of prophesy (Micah 1:5–6). The prejudice and enmity of the Jews toward the Samaritans in the days of the Savior was most bitter, even more so than towards the Galileans. The Samaritans were remnants and representatives of the revolted tribes. They had been the most violent antagonists of the Jews in the rebuilding of the temple in Jerusalem. They had erected another temple on Mount Gerizim. They rejected the sacred books of the Jews, with the exception of the book of Moses. Their religion was an abomination to the Jews, being a profane mixture of Judaism and paganism. For these reasons the Jews had no dealings with the Samaritans. The term Samaritan became to a Jew suggestive only of reproach, insomuch that when they would express their deepest disgust and abhorrence of Christ, they said, “Thou art a Samaritan and has a devil.” For the same reason the Jews avoided traveling through Samaria and, when compelled to pass through the country, carried their own provisions and refused the entertainment of the people.

While engaged in examining the ruins and present status of Samaria, I was considerably annoyed by an Arabian youth who insisted in following wherever I went, calling for “baksheesh.” At last I made a pass at him without hitting him, after which he disappeared. I never saw such impudence as these Arabs exhibit. Whenever a decently dressed European on the travel makes his appearance in any Arab town it is the signal for the general cry of “baksheesh.” Even little children, mere infants, who as yet are unable to talk plain, are taught by their mothers to call for the much coveted baksheesh when they see a white stranger.

After spending about an hour and a half in Samaria, we continued our journey to Nablus, distant about six miles in a southeasterly direction, where we arrived at 4:00 p.m. in time to attend the Church of England afternoon service. I put up with the Reverend Christian Falscheer, the Protestant missionary of Nablus. He is a German by birth but has spent over thirty years of his life in his present position in Nablus. After the services the Arab servant of the house accompanied me a short distance upon the slope of Mount Gerizim to view the town from an elevation; he then piloted me through the narrow, crooked streets of the town, many of which were arched over and were actual tunnels under tall buildings. At length we reached the quarter of the Samaritans, where I, for a small fee, was conducted into the old synagogue and shown a very old copy of the Pentateuch (the five books of Moses), which these people claim to have been written by a great-grandson of Aaron but which cannot possibly be older than the Christian era. As I had been told that a more modern copy is generally exhibited to visitors instead of the original, I insisted on seeing a second copy, which was finally permitted; and thus I have reason to think that the old copy was actually shown me. It was written upon parchment and mounted on rollers.

The quarter of the Samaritans is in the southwest part of the town. Their synagogue consists of a small, whitewashed chamber, the pavement of which is covered with matting, and must not be trodden on with shoes. Their worship is interesting. The prayers are repeated in the Samaritan dialect, although Arabic is now the colloquial language of the people. The men wear white surplices and red turbans. The office of high priest is hereditary, and Yakub, the present holder of it, is a descendant of the tribe of Levi. He is the president of the community and, at the present time, one of the district authorities. His stipend consists of tithes paid by his flock. He took great pains to explain by signs and gestures what he thought I should know about him and his relics; and when I was leaving, he handed me his portrait. I thought as a token of friendship and remembrance. But I was soon reminded of an extra baksheesh. At first he struck up two of his fingers and cried out franks. This of course, to a man of ordinary intelligence, meant two franks. I was about handing back the specimen of the photographer’s art, instead of the money, when up came one finger only, and so I paid him his frank and passed on; and the face of Yakub is on exhibition in my private collection to this day.

Shechem, under the name of Nablus, is still an inhabited city of 20,000 souls. Sheltered in quiet seclusion between Ebal and Gerizim, “the mounts of blessings and of curses,” which tower high above it, like lofty walls on either side, and surrounded by groves and gardens, this ancient town—the Sichem, or Shechem of the Old Testament, and the Sychar of the New—present a scene delightful in itself and of surpassing interest in its historical associations. It is on the line of the central or middle route from Jerusalem to Galilee, at the distance of 35 miles from Jerusalem and about 40 miles from Nazareth, and midway between the coast of the Mediterranean and the Jordan, in a narrow dell between the famous summits of Ebal and Gerizim. The valley which separates these mountains opens at the distance of two miles east of Shechem into a fertile and beautiful plain, extending from eight to ten miles from north to south and varying in width from two to four miles. This is the Plain of Moreh, whose luxuriant fields afforded an inviting place of encampment for Abraham and of pasturage for his flocks, wasted and wearied by reason of their long march from their former abode in the east, for Shechem is the first place in the land of Canaan where the great patriarch made his temporary home. From the time of Abraham’s arrival till the final overthrow of the Jewish nation, Shechem was an important landmark in the geography of Palestine. Here God renewed His covenant with Abraham (Genesis 12:6). Jacob, on his return from Padan-Aram, pitched his tent over against this city, at Shalem, on the east of the plain. Here was also Jacob’s field, a parcel of ground which he gave to his son Joseph (Genesis 33:18–19). His sepulcher is there to this day. At the distance of about 600 feet from Joseph’s tomb, is Jacob’s Well, at the mouth of which the Savior sat in His interview with the woman of Samaria (John 4:5). Here was enacted the terrible tragedy connected with the dishonor of Dinah by the son of Hamor, prince of the country (Genesis 3:4). Here Jacob kept his flocks, even when at Hebron fifty or sixty miles distant. At Dothan, fifteen miles northwest, Joseph was betrayed by his brethren (Genesis 37). The Israelites, immediately after their return from Egypt, here ratified the law of the Lord. While six tribes were encamped on Ebal and six on Gerizim, the ark and the attendant priests in the valley below, pronounced the blessings and the curses, and all the assembled multitude raised to heaven their solemn “Amen” (Deuteronomy 27). Here they buried the bones of Joseph. Here Joshua met the assembled people for the last time (Joshua 24:1, 25, 32). Shechem was allotted to Ephraim and assigned to the Levites. It was the scene of the treachery of Abimelech (Judges 9), the parable of Jothan and of the revolt of the ten tribes. It was and ever has been the abode of the sect of Samaritans, a little remnant of whom still go up on Mount Gerizim to worship God on that mountain, as did their forefathers in the time of the Savior (John 4:20). It was captured by Shalmaneser, king of Assyria, under Hosea and repeopled by a strange people, and again in the days of Nehemiah and of Ezra (2 Kings 17; Ezra 4:9). A vast temple, the ruins of which still remain, was built here by Sanbaliat, in the time of Alexander the Great, which two hundred years later was destroyed by the Maccabees.

“Jenson’s Travels” [11]

Monday, July 6. Having enjoyed a good night’s rest in the hospitable home of Mr. Falscheer in Nablus, who insisted on charging me nothing for my keep, I arose at early daylight and continued the journey toward Jerusalem. Immediately east of the town of Nablus, we came to Jacob’s Well, which we stopped to examine. I desired a drink from that historic fountain, but the attendant informed me that it was positively dry in the summer months; so I had to content myself with a peep into its dark excavation. Jacob’s Well belongs to the Greeks and has been enclosed with a wall. Jews, Christians, and Muslims all agree that this is the well of Jacob, and the tradition to that effect is traceable as far back as the fourth century. Situated as it is on the high road from Jerusalem to Galilee, it accords with the narrative in John 4:5–30. The Samaritan woman who conversed with Jesus at the well did not come from Shechem but from Sychar, which is probably identical with the modern Asker. In that case, tradition pointed to this place as Jacob’s Well in the day of Christ (John 6:5,6) and the field which Jacob purchased and where Joseph was afterwards buried (Joshua 24:32). The well or cistern is 75 feet deep and 7 ½ feet in diameter; it is lined with masonry. Joseph’s tomb is shown in a building about half a mile to the northeast of Jacob’s Well. The Jews burn small votive offerings in the hollows of the two little columns of the tomb.

From Jacob’s Well we traveled up the plain of Makhna, or Moreh, where Abraham pastured his flocks after their long and weary march from the land of the Chaldeans.

Beyond the plains of Makhna we crossed the “mountains of Ephraim,” traversed several valleys, among which is Luban, the ancient Lebonah (Judges 21:19), which is situated in the northeast corner of a small plain. Beyond this plain we crossed a mountain of considerable height. During the entire day’s journey we traveled over very bad roads, which were generally enclosed with rock walls on both sides, with numberless rocks thrown in the center where animals and people travel. In fact, we simply rode along the ridges of huge artificial rock walls most of the way from the Plain of Makhna to Jerusalem. At 2:00 p.m. we arrived at Baytin, the ancient Bethel. From the rocky ridge immediately north of this place, I obtained the first glimpse of the Holy City; but particularly the Mount of Olives, on which the Russian Greeks have built a high tower, which is visible for a long dis[tance]. Baytin consists of miserable hovels with about 400 inhabitants and stands on a hill, 15 miles north of Jerusalem, and 20 miles south of Shechem, or Nablus. If Baytin is really identical with the ancient Bethel, the place has a long history. It was originally called Luz, and here Abraham built an altar unto the Lord (Genesis 12:8). In the year following his return from Egypt, he again encamped here and parted on friendly terms from Lot (Genesis 13:3–10). Jacob, flying from Esau toward Haran, saw here the vision of the ladder and the angels ascending and descending upon it (Genesis 28; 31:13). Twenty years later, on his return from Padan Aram, he lingered at this sacred spot, built an altar to the Lord, and received the promises of God, and erected here a pillar (Genesis 35; 32:28; 28:20–22). Here Deborah also died. Three hundred years after this, in the distribution of the land under Joshua, Bethel became the portion of Benjamin on the boundaries of Ephraim into whose hands it afterwards fell (Joshua 18:13, 22; 16:1, 2). It was for some time the consecrated place of the ark of the covenant (Judges 20:18, 26; 1 Samuel 10:3). Samuel held here his court in his annual circuit. Near Beth-aven Jonathan smote the Philistines (1 Samuel 14:1–23). From Jeroboam to Josiah, more than three hundred years, it was desecrated by the worship of the golden calves (1 Kings 12:28, 29; 13:1; 2 Kings 10:28, 29; 23:15–18). By reason of this, it was under the name of Beth-aven, the frequent subject of prophetic denunciation (Hosea 4:15; verse 8; 10:5, 8; Amos 5:5). Elisha was going from Jericho to this place when mocked by the impious children who were torn in pieces by wild beasts (2 Kings 2:23–25). After the captivity it was rebuilt (Ezra 2:28; Nehemiah 7:32). In the time of the Maccabees it was fortified and finally destroyed by Vespasian. The hill upon which it was built was quite overspread with ruins, among which are the remains of an immense cistern, 314 feet in length and 217 in breadth.

Having watered ourselves and animals at the spring near Bethel, we continued our journey through Al-Birah, mentioned in Joshua 9:17 and 2 Samuel 4:2–3. Passing on, we traveled immediately to the right of Ramallah, the ancient Rameh of Benjamin. This place is situated on the top of a hill, and in ancient days it formed a kind of frontier castle between the Northern and Southern kingdoms (1 Kings 15:17). After the captivity it was repeopled; it is now occupied by about fifteen families only. This place is about six miles north of Jerusalem. About three miles further south we passed the hill called Tell el Fur, which is identical with Gibeah of Benjamin (Judges 19 and 20). If Gibeah of Saul was identical with Gibeah of Benjamin, this was then also the place where David was permitted the murder of the seven sons of Saul (2 Samuel 21). A little nearer the Holy City we pass the village of Shu’fat, which is supposed to be the Nob mentioned in 1 Samuel 21:23. Beyond Shu’fat we ascended the hill Scopus, from the top of which we obtained a most beautiful view of the city of Jerusalem and its surroundings. Though exceedingly tired of my long ride, the first sight of the Holy City made such an impression upon my mind that the body accommodated itself to the fatigue without murmuring. About half an hour’s ride from the hill of Scopus brought us across the upper Kidron Valley to the so-called Yapa suburb, where I secured lodgings of the Olivet House, kept by Mr. and Mrs. Hinsman, and dismissed my muleteer, who had been a pretty good and faithful servant to me during my three days’ ride from Nazareth. We had traveled about eighty miles, part of the time, particularly the last day, in company with many other travelers who were going up to Jerusalem with beasts of burden loaded with goods for the market. The last day we had traveled about thirty-eight miles, and that two in one stretch, as the Arabians seem to know nothing about stopping to rest themselves and animals in the middle of the day. I have reason to believe that I traveled over the same road that Jesus made use of in his journeys between Galilee and Jerusalem, as this is the only direct road leading through the heart of the country from north to south.

After eating supper at the Olivet House, I went out for a walk, on which I entered the city of Jerusalem proper through the Yafa Gate. I traversed nearly the entire length of David Street and then returned to the hotel to enjoy my first night’s rest in the ancient city.

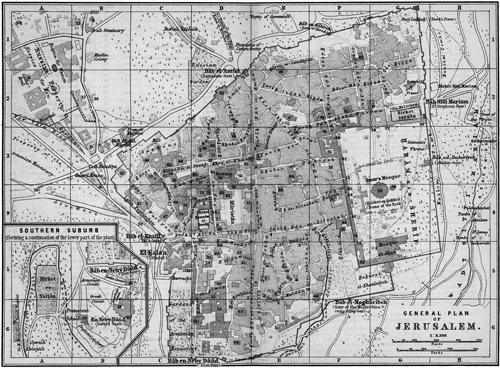

Tuesday, July 7. After taking a long morning walk through the suburbs outside of the Jaffa Gate, I called on the representative of the American consul (the consul himself being absent from the city), who sent his dragoman with me to the Mosque of Omar, situated on Mount Moriah. We also visited the Mosque of El-Aksa, Solomon’s stables, and other points of interest within the great mosque enclosure. After the dragoman left me I visited the Church of the Sepulcher, a local guide taking me through all its numerous departments. Next I visited the Zion part of the city, passed through the Zion Gate, which is called Bah en-Neby Daud by the Arabs, and rambled through the suburb lying on the brow of the hill on the outside. I also climbed to the top of the wall near the Zion Gate, where a good view is obtained. My next move was to pass through the heart of the city, which I then left behind as I passed through St. Stephen’s Gate on the east. I now crossed the Brook Kidron on the upper bridge, passed the garden of Gethsemane and ascended the Mount of Olives, where I first visited the Chapel of the Ascension in the Muslim village, and was afterwards permitted to ascend the lofty Belvidere tower, from the top of which a most magnificent view was obtained of Jerusalem and surrounding country; also the north end of the Dead Sea and part of the Jordan Valley is visible from the lofty elevation. On my return to the city I visited the so-called Tomb of the Virgin in an underground Greek chapel, situated near the bridge across the Kidron. Jerusalem is situated in the midst of the central chain of mountains, which runs north and south through Palestine, 33 miles from the sea, 24 from the Jordan, and nearly the same distance north of Hebron. It occupies an irregular promontory in the midst of a confused sea of rocks, crags, and hills. This promontory begins at the distance of a mile or more northwest of the city at the head of the valleys of Jehoshaphat and Gihon, which gradually fall away on the right and left, and sinking deeper as they run in a circuitous route around the opposite sides of the platform of the city, unite their deep ravines at some distance southeast of the city, and many feet below the level of its walls. Perched on this lofty promontory, the historical city dwells on high, at an elevation of from 2,200 to 2,589 feet above the level of the sea; surrounded on three sides by the entrenchments of her valleys and rocky ramparts, her place of defense is the munitions of rocks. The Valley of Jehoshaphat, on the north, runs nearly east for some distance, then turns at a right angle to the south, and opens a deep defile below the eastern walls of the city, between it and the Mount of Olives. The valley of Gihon pursues a southerly course for some distance, then sweeps in a bold angle around the base of Mount Zion and falls by a rapid descent into a deep narrow water course, which continues in an easterly direction to its junction with the Valley of Jehoshaphat. (Insert panoramic view of Jerusalem from Baedeker guide)

The platform or site of the city is divided into four quarters of unequal elevation, two of which are familiar to the reader of sacred history as Mount Moriah and Mount Zion. Near the line of the valley of Jehoshaphat, before it turns to the south, a slight depression begins at the north gate of the city. This depression, the head of the valley of Tyropoeon, as it runs south through the city, sinks into a deep valley, and divides the city into two sections, of which the east is terminated by Mount Moriah, on which the temple stood. The western division is terminated by Mount Zion, where was David’s house and the royal residence of his successors. These two heights were anciently united by a bridge crossing the Tyropoeon by a lofty arch, or rather by a series of arches it would seem (for the Tyropoeon Valley is here 380 feet wide), of which one of the bases still remains. The Tyropoeon below the walls on the south corresponds to the valley of Hinnom, which name is also applied to the lower part of Gihon, south of the city.