Memories of Matthew Cowley: Man of Faith, Apostle to the Pacific

Glen L. Rudd

Glen L. Rudd, “Memories of Matthew Cowley: Man of Faith, Apostle to the Pacific,” in Pioneers in the Pacific, ed. Grant Underwood (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005) 15–31.

Glen R. Rudd was an emeritus member of the First and Second Quorums of the Seventy, a former mission president of the New Zealand Wellington Mission, and former president of the New Zealand Temple when this was published.

Fig. 1. Matthew Cowley Courtesy of Kia Ngawari Trust

Fig. 1. Matthew Cowley Courtesy of Kia Ngawari Trust

Nearly a half century has come and gone since Matthew Cowley passed away, and still there are many individuals who ask me about him. I regularly get invitations to speak about him. In the past, I have appreciated the opportunities; however, the time has come that I feel I can no longer do it. So, for the record, I would like to share a number of thoughts and stories that may add to our understanding of the unusual life of this truly humble and interesting man.

Matthew Cowley was a simple, uncomplicated, ordinary, wonderful man. He was not the greatest man I have ever known, not the smartest or the best leader, the best organized, or the hardest worker. But of all the men I have ever known, I have never known one with more faith, and over the years I have traveled with some pretty great souls and men of great faith.

Matthew Cowley was born in Preston, Idaho, in 1897 in a big, beautiful rock home, not far from the old Oneida Stake Academy. Before he was born, one of the members of the Quorum of the Twelve visited that home. While he was there, Brother Cowley’s father, Matthias, asked him to dedicate the home. Abbie Cowley, Matthias’s wife, wrote in her journal that the Apostle prayed that therein “might be born prophets, seers, and revelators to honor God; that great faith, the greatest of all gifts should be exercised.” [1] Two years later, Matthew Cowley, who eventually became a man of great faith and a “prophet, seer, and revelator,” was born in that home.

I first got to know Matthew Cowley when he was my mission president in New Zealand, and I was one of his secretaries and his traveling companion. We would go from place to place blessing the sick, holding meetings, and so forth. What a privilege it was to sit side by side with this magnificent mission president who, at the time, was only forty years old. To sit with him, to live in his home, to pray and to eat at his dinner table, and to be his close companion were some of the great blessings of my life. He told me stories and all kinds of interesting things. For instance, he grew up on the block known as “Apostles’ Row,” just northwest of Temple Square. He lived next door to Anthon H. Lund, who was a counselor to President Joseph F. Smith, two blocks away from President Smith himself, and less than a block away from John Henry Smith and his son George Albert Smith. He told me about some of the troubles the kids got in. The sons of the Apostles were not always as obedient as they should have been. Once during a meeting in the Salt Lake Tabernacle, they were up in a nearby barn trying to figure out how to smoke, and they set the barn on fire. The fire engines roared on both sides of Temple Square, and the meeting was dismissed so the barn that the sons of the Apostles had set on fire could be rescued. Brother Cowley was a rascal as a boy. He never did anything bad but still always seemed to get into difficulties.

When he was just sixteen years old, Matthew asked his father if he could go on a mission. His father said that if the President of the Church would call him, he could do anything. So Brother Cowley let everybody know that he wanted to go and that he hoped to be called to Hawai‘i, where his older brother Moses had served. Not long thereafter, a letter came from President Joseph F. Smith calling him to go to Hawai‘i on a mission, and this young boy, about to turn seventeen, jumped with joy. When his next-door neighbor, President Anthon H. Lund, drove up from work, Brother Cowley ran to tell him the great news.

President Lund said, “It’s about time!” Imagine, Brother Cowley was just turning seventeen, but the neighbors wanted to get rid of him fast! President Lund said to him, “You know, you have caused a lot of trouble in the neighborhood. You’ve broken my fence, my hedge, ruined our flowers, and caused all kinds of trouble. Hawai‘i is not far enough away. You need to get as far away from us as possible.” And then, more seriously, he said, “I don’t think you’ve been called to the right place. Would you care if I took this mission call back to the President of the Church and discussed it with him? I’m dead serious when I say that I think you should go to the ‘uttermost bounds of the earth’ to preach the Gospel.”

Then he took from this very disappointed young boy his mission call and discussed it with the President of the Church. Within a couple of days, another letter came from President Smith asking Matthew to accept a call instead to go to New Zealand, which was definitely the “uttermost bounds of the earth.” [2]

So off this young boy went to New Zealand. He had just turned seventeen when he arrived at the mission headquarters in Auckland. Soon he boarded a boat and headed for his first assignment. About four miles south of the little coastal town of Tauranga lies a small Maori village, all Latter-day Saint, known as Huria (Judea). Here Matthew Cowley commenced his labors in New Zealand. Early in his mission, he became seriously ill and for some time was unable to do much physical work. He was left without a companion for six weeks. During that time he read the Maori language out of the Bible and the Book of Mormon. Typically he would rise in the morning, go over to a little grove of trees, and spend most of the day studying the Maori language, sometimes from six in the morning until dark. Interestingly, in the late 1880s, his cousin Ezra Foss Richards had been the lead translator of the Book of Mormon into Maori. Often, young Elder Cowley would read aloud to the older Maori lady in whose dwelling he lived. As she listened to him speak the Maori language, she corrected him, helped him, and taught him. And he prayed and prayed. Eventually, he became one of the greatest Maori speakers of all time. He was a magnificent orator. He also knew the English language well, better than almost anyone I have ever known. His vocabulary was absolutely beautiful and seemed to be limitless. He received the gift of languages.

His interest in and gift for languages remained with him throughout his life. When he became an Apostle, we ate quite often together. We would go into a Greek café and he would want to see the Greek chef, or the Chinese chef in a Chinese café, or the Japanese chef in a Japanese café—he would go back and talk to them in their own language. He would say, “How do I say this?” or “How do I ask you about your wife and children?” They would tell him in their own language, and he never forgot. He had a memory that was unbelievable. It was wonderful to go with him and hear him talk to the Chinese, the Greeks, the Italians, the Japanese, and always be able carry on a little conversation.

On one occasion near the beginning of his mission, he was returning to Judea on horseback and dozed off and had a dream. He saw himself as a little boy sitting on his father’s lap. He was scared, but his father put his arms around him and held him. A man with a long beard came over and put his hands on his head. Then he woke up, still on the horse, and the thought came to him, “I wonder if I have ever had a patriarchal blessing?”

So when he got back to Judea, he wrote his mother a letter asking if he had ever had a patriarchal blessing. Two months later (it took a month for the mail to go one way), he received a letter from his mother. She said that when he was five years old, he went with his father down to Mancos, Colorado, and stayed in the home of an old patriarch named Luther Burnham. While visiting, Matthew’s father asked the patriarch to give his little boy a patriarchal blessing. Just as in the dream, his mother reported that her husband said Matthew was shivering and scared, so he put his arms around him. The patriarch, who did indeed have a long beard, put his hands on Matthew’s head and bestowed upon him his patriarchal blessing. Matthew’s mother enclosed the patriarchal blessing with her letter.

For the first time in his life, this wonderful young man read his magnificent patriarchal blessing:

My beloved son Matthew, I place my hands upon your head and confer upon you a patriarchal blessing. Thou shalt live to be a mighty man in Israel, for thou art a royal seed, the seed of Jacob through Joseph. Thou shalt become a great and mighty man in the eyes of the Lord, and become an ambassador of Christ to the uttermost bounds of the earth. Your understanding shall become great, and your wisdom reach to Heaven. . . . The Lord will give you mighty faith as the brother of Jared, for thou shalt know that he lives and that the Gospel of Jesus Christ is true, even in your youth.

What a wonderful blessing!

Toward the end of his great first mission, Brother Cowley was assigned to retranslate the Book of Mormon into Maori and to translate the Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price into Maori for the first time. Brother and Sister Wi Duncan dedicated two rooms in their beautiful home in Tahoraiti for Brother Cowley’s use. Years later, when he was mission president and I traveled with him, he invited me to stay with him in the room he had used to translate. But the Maori people would not let me sleep there. They said it belonged to the mission president, and nobody but Brother Cowley could go in there. I have been in that house many times since, and I always considered it a very sacred place.

While Brother Cowley was translating the Pearl of Great Price, he was asked to bless two little cousins, a boy and a girl. An interesting thing about the Maori is that when they ask you to name and bless a child, you have the privilege of choosing the name; the parents never tell you what to do. When they ask you to use the priesthood, they do not dictate. So he picked up the little girl and named her Pearl. Then he picked up the little boy and named him Great Price. I have often thought how lucky it was that he was not translating the Doctrine and Covenants instead at that time! Great Price (we always called him Price; I knew him well) has been in our home and stayed with us as a bishop, as a member of the stake presidency, and as a patriarch. What a wonderful man he was! People did not call him Great Price, but he was.

When Brother Cowley returned home from his mission, he was twenty-two years of age. He still had not graduated from high school but managed to get into the University of Utah in any case. I have to say parenthetically that Brother Cowley was a great reader. He was the first and best speed-reader I ever saw. He could read an ordinary book of three hundred pages in just a couple of hours. It was unbelievable to watch him read, which I did many times. He had read and studied and schooled himself. After the University of Utah, he went to George Washington University in Washington DC, where he spent four years going to law school. He had the great honor of working as an assistant to Senator Reed Smoot, who also was an Apostle. Senator Smoot was the chairman of the Senate Finance Committee and one of the most powerful men in the Senate because he held the purse strings.

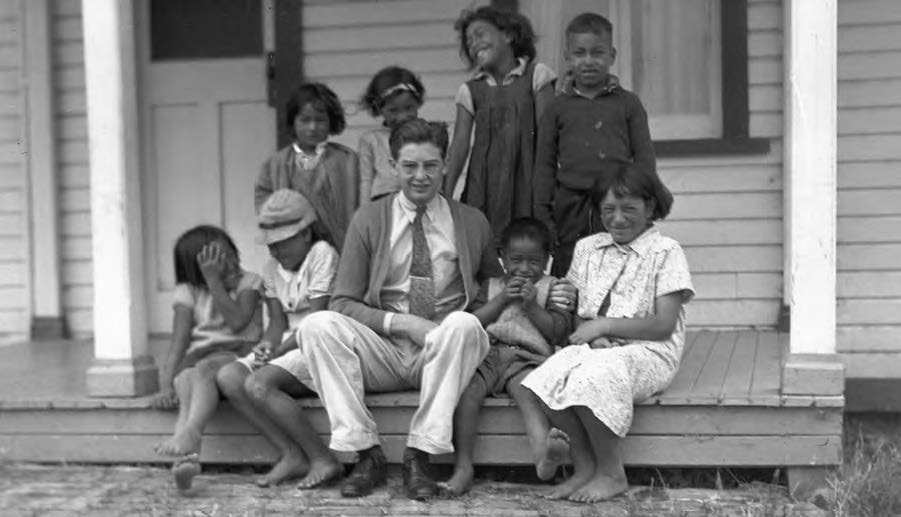

Fig. 2. Glen L. Rudd as a missionary in New Zealand Courtesy of Glen L. Rudd

Fig. 2. Glen L. Rudd as a missionary in New Zealand Courtesy of Glen L. Rudd

After graduating from law school, Brother Cowley and his wife returned to Salt Lake City to live. For a dozen years he practiced law, but his humanitarian impulses prevented him from making much money. Then in the late 1930s he was called to return to his beloved New Zealand as mission president. While his first mission to New Zealand lasted five years, Matthew Cowley’s second mission to New Zealand, thanks to World War II, lasted nearly eight years. He spent much of his time as mission president trying to teach all of the people of New Zealand to kia ngawari. This simply means to be changeable, to be supple, to be bendable, to be willing to roll with the punches, to be willing to follow the leadership of the Church, and make all the necessary changes to do so. One day I asked him what kia ngawari meant, and he said, “It’s the thirteenth article of faith in two words.” After Brother Cowley’s death, Walter Smith, that great and wonderful Maori musician, wrote a lovely anthem by the same name to honor Brother Cowley. It has now been sung pretty steadily in America and in New Zealand and in other places for the past half century.

I received a mission call to New Zealand on August 31, 1938. When the great ship pulled into Auckland Harbor, we were getting our briefcases and things out of our stateroom. We heard a man stand in the door and call out, “Are there any Mormons here?” We turned around and there stood President Matthew Cowley, the man who was to be our mission president and our leader for the rest of our lives. I can remember what he looked like. He had a coat on that did not match his pants, and he wore a pair of softsoled shoes. He was a short, stocky man, about five feet eight inches tall, and only forty years old at the time. He had been in the mission for about eight months. President Cowley began almost immediately to impress us with something that was wonderful—his ability to radiate a great spirit, a spirit of love for those around him. And he particularly loved the Maori people.

I had my own experiences with the Maori that helped me feel similarly. On one occasion, while standing on the sidewalk in front of a store, an old Maori man came up to me. He tried to give me a coin, a two and sixpence, worth about fifty cents. At that moment I had fifty dollars in my pocket, which was enough for me to live on for three months. I did not need his money. He tried to give it to me. He did not speak any English. I did not know any Maori. But I could tell that he was trying to give me this money. I finally sent him on his way. When my companion came out, I said, “See that old Maori man walking down there? He tried to give me some money!” He said. “What did you do?” I said, “I wouldn’t take it!” He said, “Well, go get it!” I said, “I don’t want it! I don’t need it! I’ve probably got ten times or twenty times more money that he’s got.” Elder Dastrup said to me, “Go on down the street—run down—and get a hold of him, and tell him to give you the money.” So reluctantly I did. When I got to him, I held out my hand. As he gave me the coin, I saw some tears come to his eyes. I realized that it was something special to him. I think he saw in me, a young pakeha (Caucasian) boy, more than I thought I was. I was a servant of the Lord. He was giving me his last money, knowing that the Lord would bless him and pour out great blessings upon him because he was good to a humble servant of the Lord. That day I began to fall in love with the great Maori people of New Zealand. I learned what it meant to let somebody do something for you that they wanted to do.

Matthew Cowley was very good at that. On one occasion, while traveling with President Cowley to Tahoraiti, we stopped in Palmerston North to see Wi Pere Amaru, one of our Maori brothers who taught music. When he heard where we were going, he asked to go along. Before leaving the city, President Cowley went to the post office and sent a telegram to Sister Polly Duncan that said, “Kill the fatted calf; we’ll be there for supper—signed Cowley, Rudd, and Amaru.” When we arrived, she had a great banquet prepared with chop suey and about five other things that she knew President Cowley enjoyed. He never refused to let people do things for him. As a result, everybody loved him.

Hospitality is a hallmark of Polynesians. One day while we were traveling on our bicycles, we arrived at a little home south of Waipukurau. It was the home of Sam Thompson and his family. I remember we drove up to this little shack that looked to me like it was about to fall in, and I saw all of those kids and realized they wanted us to stay and spend the night with them. We had been traveling on our bicycles for quite a while. They immediately began to prepare food for us, which they always did, no matter where we went. Anyway, after we ate, we wanted to have a little meeting. I thought, “Well surely because we’re missionaries, we need to have a little cottage meeting or at least bear testimony.” We could tell they were good Latter-day Saints. They really did not need it, but I thought they ought to get it. Anyway, all the kids were anxious for us to go to bed. It was getting dark. I was not anxious to go to bed. The family was pushing us to go to bed. I thought, “I wonder what’s so different here?” So finally it was decided that it was time for us all to retire. And then they did a marvelous thing. They took us out in the back of this old shack of a house they lived in and through some trees, and there stood a beautiful new home that had been built and finished for probably two or three months. They said, “This is where you’re going to sleep tonight.” Sister Thompson fixed us a place to sleep on the floor in that home.

Now the kids were jumping for joy, and I could not imagine what was happening. The answer was that they wanted to move into their new home, but they could not move there until the servants of the Lord had spent the first night in that home, and when they were gone, then the family could move in. We had a fairly good night’s sleep, but they were up early. They almost rushed us out of the house so they could leave that little shack that they were in and move into their beautiful new home. Once again I saw a happy family, and my love for the people of New Zealand grew and grew.

I remember going from home to home, staying with people, sometimes showing up just as it got dark. I would see the mother make the bed, get out some clean sheets, and put them on the bed so that the elders could sleep in the bed. Not only sometimes but most of the time, those who were going to sleep in the bed ended up on the floor. It was hard for me to see a mother who was about to have a baby get out of bed and sleep on the floor while I slept in the only good bed in the house. I heard Brother Hare Puke tell about his mother sending him next door to borrow some sheets for the bed. They did not have sheets. This was during the Depression, but he went to get sheets so the elders could sleep on good, clean sheets. Those kind of things are difficult for missionaries, just like taking money from the Maori man who was giving us his last. It was marvelous for us to be blessed by them, even though it was hard. I tell you, the people of Polynesia, and it does not make any difference where, have sacrificed for the American missionaries, and now they sacrifice for their own local missionaries so they can do what they feel they ought to do.

Let me tell you how I ended up in the mission home and became President Cowley’s constant companion. I had had some sickness, and after four or five months of boils and carbuncles and haki haki (itchy skin disease) and whatever a pakeha boy could get, I wondered if I was ever going to pull through. A doctor told me I would die within thirty days if I did not get back to America. We prayed, and old Pop Hamon, whom we lived with in Gisborne, gave me the blessing that I needed. The very next day after the doctor told me I could not live more than thirty days, I received a telegram from President Cowley while he was on the road, saying, “Pack your bags and go immediately to Auckland headquarters.” I do not think he ever knew how sick I was. When I asked President Cowley why he transferred me, he said, “I got up in the morning, and I thought about you.” I wondered why he would think about me when he had a whole group of missionaries to worry about. Then he said, “I didn’t do anything. But by noon, I had been thinking about you all through the morning. Finally in the afternoon, I thought I’d better listen to the Lord, and I sent the telegram.” When I got to headquarters, the doctor began to help me. He took a pair of pliers and pulled off my badly infected toenail and scraped the bone a little bit. Since we did not have any aspirin or anything to ease the pain, that was an event!

When I could get around and walk a bit, I started tracting again. Then one day President Cowley said to me, “I want you to be the assistant secretary to the mission, but I don’t want you to do any work.” I said, “Well, what do you want me to do?” He said, “Well, just help Elder Haslam. He’s the secretary. But don’t get too involved, because when I want you to go with me, I don’t want you to be in the middle of a report or anything.” He said, “You pack your briefcase, put a couple of shirts in it, and some socks and some underwear, and leave it right by your desk. And when I open the door and say, ‘Let’s go,’ you grab your briefcase and beat me to the car, and then don’t ask any questions.” So that began to happen, and for several months, I had the privilege of traveling from one end of New Zealand to the other with this great man.

Many times we were not sure where we were going. President Cowley never planned his days, never organized what he was going to do. He just went where the Lord wanted him to go. Once we had driven for maybe an hour, and he said, “You probably want to know where we are going.” “Yes,” I replied, “but I am not going to ask you.” And he said, “Well, I’d tell you if I knew. We’ll just go out and visit the people, and we’ll find where we’re supposed to go.” It made you wonder how a man could preside over a whole mission with missionaries spread all over the two big islands of New Zealand and never plan or organize like you think he would.

Fig. 3. Glen L. Rudd and local children during his mission in New Zealand Courtesy of Glen L. Rudd

Fig. 3. Glen L. Rudd and local children during his mission in New Zealand Courtesy of Glen L. Rudd

Often when we would drive to a location, he would stop at the post office and send a birthday telegram to one of his missionaries having a birthday. He had a marvelous memory; he remembered everyone’s birthday, without ever having to write it down, clear up until the day he died. On one of these occasions, after traveling about eight hours, we pulled up at the post office. There were two sisters of the Church standing there waiting for him. He got out and asked what was happening. One of them said, “My mother told me that if we came to the post office, you’d be here today. We’ve been praying for you to come. Someone is sick.” Then he would realize why he had been prompted to travel to that location. People prayed President Cowley all over the mission.

President Cowley did love to bless people. One time he blessed a little boy named Te Rauparaha “Junior” Wineera, who was born blind. His father said to President Cowley, “When you give him his name, give him his eyesight.” President Cowley described that as a tough assignment. He blessed him, hemmed and hawed around for a while, waiting for the inspiration to come. Then it came, and he blessed him with the ability not only to see but also to hear. And he blessed him that over his young childhood, he would gradually overcome all the problems dealing with his equilibrium. The family did not know that this little baby was also deaf and that he had a problem gaining balance. Junior is in his sixties now and has superb vision. My wife and I have had our picture taken with him on various occasions. We both have glasses, and Junior, standing between us, has no glasses. He can read signs farther away than anybody I know. What a humble, sweet Maori man!

One day we went over to Tauranga and down to Judea to see a dear old Maori sister. President Cowley said, “I have to go see my Maori mother.” This is the lovely old sister who had taught him the language and then helped him so much in the early months of his mission. We went to see her. She was almost blind, living in a little lean-to. We had to get on our hands and knees to crawl back to where she was. We knelt down, and I heard him give her a magnificent blessing. It was one of the greatest I have ever heard. I felt his love for this great Maori sister who had done so much for him.

I told you about Great Price and Pearl. Down in that same village of Tahoraiti were two young Maori men—Nitama Paewai and Luxford Walker— who had wanted to become professional men, a doctor and a dentist respectively. So they went to the principal of their high school from which they were ready to graduate. They asked for three days off to study for their final examination. It was the examination on which everything depended. They did not want to go to school to study; they wanted to prepare at home. The principal said, “You can’t do that. Everyone has to be here; you have to do your studying here at school.” But they promised that if he would let them stay home, they would not do anything wrong, that they wanted to graduate with high honors. They just wanted to stay home to fast and pray. The principal said he would think about it and that they should come back in a half an hour.

Fig. 4. Matthew Cowley with four Maori boys dressed for a cultural performance Courtesy of Church Archives

Fig. 4. Matthew Cowley with four Maori boys dressed for a cultural performance Courtesy of Church Archives

After they left, he called up Wi Duncan, who was at that time one of the most influential men in the town of Dannevirke, and asked, “Wi, what does it mean to fast and pray? I know a little about praying, but I don’t know anything about fasting and prayer. What do these kids of yours want to do?” Wi asked who the kids were. When the principal told him who they were, he said, “Let them stay home. Let them fast and pray. They won’t disappoint you. I’d advise you to grant their request.” The principal said he would, and when the boys came back in a half hour, he told them to go ahead, but to come back and do well. On the final exam, they did well; they ended up first and second in scoring and both received scholarships to the big university on the South Island so that Nitama could study to be a doctor and Lux could study to be a dentist. They went down to Otago University to become professional men. This was before many Maori went to the university. Most never got through high school.

Three or four months passed. President Cowley went to hold a branch conference in Tahoraiti. Sitting in the congregation very near the front were Lux and Nitama. When the meeting was over, he called them up and asked them what they were doing there since they were supposed to be studying at Otago University.

They said, “Tumuaki, those professors, the students, everybody down there is against us.” Let me explain parenthetically that among the Maori members and the missionaries, President Cowley was known as Tumuaki, a word of utmost respect meaning “president” in the Maori language. “Tumuaki,” they continued, “they don’t want Maori boys to get an education. They ridiculed us, laughed at us, and ran us out of school. We just couldn’t stand it anymore. We had to quit.” Tumuaki said, “Well, that’s okay with me. What are you going to do now?” “Get a job,” they replied. Tumuaki said, “You’re both nineteen years of age. Would you like to go on a mission?” Boy, did they jump for joy! So when the afternoon meeting was over, President Cowley ordained them and set them apart as full-time elders for the Church. Then he walked away from them. Nitama and Lux ran after him and asked him where they were to start or what they should do. Tumuaki said to Nitama, “Your mission is to go back to the university and become a doctor.” And then to Lux, “Your mission is to go back and become a dentist. And you’re not going to be released from your priesthood calling until you have achieved those accomplishments.”

So they went back and both became successful men. Nitama became one of the most famous doctors in New Zealand. I returned there more than twenty times and always saw Nitama. He died in 1990 at age seventy. He was known all over New Zealand. In addition to being a renowned doctor, he was a famous rugby player. He also became the mayor of the largest city in the northern part of New Zealand. And he was called over to England to receive a great honor from the queen of England for the work he did among the Maori people. This young boy, who wanted to be something, really became a somebody because a special mission president had the courage to call him on a mission to become a doctor. Nitama said to me, “I’ve never been released from my mission call.”

President Cowley was a great person in many, many ways and was a joy to be around. As a grown man, he had the exuberance and zest for life of a fifteen-year-old boy. He was the most humorous man I have ever known. He could see humor in almost all of life’s circumstances. He did not try to be funny; he just kind of radiated it. He told me about district conference down in Korongata, where a particularly lively bunch of Latter-day Saint boys lived. “We just had a wonderful hui [gathering],” he reported. “You won’t believe it, but we had a very special rest song. The song that was sung for us by three or four Maori boys was, ‘Roll Out the Barrel.’” President Cowley must have laughed for a month. He had the ability to handle those kinds of things well. You know, I have lived with President Hinckley before and known him intimately for almost fifty years. He could handle that! Some of the other General Authorities would almost have a stroke! But President Hinckley is a lot like President Cowley. He could handle “Roll Out the Barrel” about as well as anybody I know today.

President Cowley was always interested in missionaries who were filled with life and a little mischief. In fact, after we (six missionaries) had been in the mission home for some months, he called us together and said he thought he would transfer all of us back out into the districts and bring some missionaries in who could create a little more havoc and bring a little more activity into the home. That was all we needed, and that particular little problem ended.

The six of us living in the mission home had a basketball team (and invited one New Zealander to play with us as a sub). On occasion, President Cowley walked to the YMCA to watch the missionaries play. One night he was sitting up in the balcony, heckling the missionaries rather vigorously. “Throw the ball to Elder Soand- so; he’ll fumble it,” or “Don’t give it to Elder So-and-so; he won’t know what to do.” After he had enjoyed heckling for a period of time, a couple of young but large Maori men walked over to him and said, “Mister, we don’t know who you are, but don’t you talk like that to those young men anymore. They’re Mormon missionaries out here performing missionary work, and they’re ministers. We’re not going to sit here and allow you to ridicule them or talk like that to them anymore!” President Cowley immediately quit heckling and returned home. He told us later that he did not think he would attend any more basketball games, that they were too dangerous for him.

President Cowley loved to cook, especially breakfast while we held our early-morning study class. He thought he was a great cook. By the way, he was pretty good. We read out loud so that he could participate. If we said a word wrong or misinterpreted something, he would correct us from the kitchen and thus add to our study. President Cowley loved to read. He often walked down the main street of Auckland to the bookstores that sold used books and would buy a dozen or more. His reading habits were wonderful, and he retained almost everything he read. He would wake up around five in the morning, grab a book by his bed, and lie in bed reading for the next two hours. He often gave us a book report at breakfast on a rather fascinating book he felt we should know about and understand.

I remember on one trip with President Cowley we had a very unpleasant task. Sometimes mission presidents have things to do that are not good. We went down and did it. We ended up in Wellington. He said, “Would you like to go fishing?” I had never been fishing in my life. Between the north and the south islands of New Zealand is a very rough body of water known as Cook Strait. Out in this rough water are many small and beautiful islands. On D’Urville Island lived a large group of wonderful Maori people who were members of the Church. Most were related to one another as part of the Elkington clan and were mainly professional fishermen. President Cowley liked to visit D’Urville Island and go fishing with them. We got on one of the interisland steamers. The only way for a passenger to get off the ship anywhere near D’Urville Island was to climb down a rope ladder lowered from the side of the ship at about two o’clock in the morning. This little maneuver did not frighten me too much until the time to perform it approached.

It was a dark night with no moon and few stars. As the ship slowed down to stop, President Cowley and I could see off in the distance a little light bobbing up and down in the water. It was a lantern held by one of the Maori men who were rowing out to pick us up. As it got closer, we could tell that the water was very rough. Finally the boat was right under us and we could look over the railing and see them. Then we heard one of them shout for us to come down. The deck steward on the ship opened a gate in the railing and threw down the rope ladder. I looked down into the water that dark night, turned to President Cowley, and said, “You are the mission president. You go first.” He looked down that rope ladder into the darkness of the night and said, “I am the mission president. You go first.”

Fearfully, yet bravely, I started down the ladder. Never in my life had I ever climbed a rope ladder more than two or three rungs long. The first and second steps were easy because I could still feel that I was near the side of the ship. But the further down I went, the further the ladder hung away from the side of the ship. After I had gone down about six steps I felt very much alone and was hanging on for dear life, praying with each step. I was frightened, but I hung on and slowly and carefully took one step at a time. Finally a large Maori hand grabbed me by the ankle, and a voice assured me, “You’ve made it!” I managed to get into the rowboat and put on a raincoat to keep me from getting wet. I sat down and relaxed. Then I looked up the long rope ladder to watch my wonderful mission president begin to climb down. I am sure he prayed just as hard as I did, and finally he made it into the boat. We were then with friends, feeling safe and secure. In a short while we were on dry land on D’Urville Island. The whole branch was out to greet us in the middle of the night.

There was a man by the name of Sid Christy who lived in the Maori village of Nuhaka on the east coast of New Zealand. Nuhaka, at that time, was a large branch of the Church with about four hundred members. One Saturday afternoon after a long eight-hour drive, President Cowley arrived at this village and went directly to see his old friend Sid. As a young man Sid had been an outstanding athlete. Some missionaries had taken him to America where he attended high school and some college. He became a well-known basketball player, and, as an all-star athlete, he received a lot of publicity. His picture was in the papers many times, and everybody knew about this fine athlete from New Zealand. He was ordained a member of the Seventy while he lived here, but when he went back to New Zealand, he found he was the only member of the Seventy in the whole country. He did not have a quorum to belong to, and he became somewhat inactive. The first thing he knew he was tampering with the Word of Wisdom and was in the habit of taking it easy, but deep within his heart he still knew the gospel to be true.

Now, as mission president and personal friend, President Cowley called on Sid. He found him sitting in a rocking chair on his front porch smoking a big cigar. Sid did not stop chewing on his cigar as President Cowley sat beside him to visit. After they had talked and laughed for a while, President Cowley became serious and said, “Sid, I want you to come to church tomorrow.” They both looked toward the old chapel that was there, and Sid said, “I think it’ll fall in. I haven’t been there for a long time. I don’t think I’d better risk it.” President Cowley said, “Sid, I want you to be there. I’m going to do something important tomorrow.” Sid inquired, “What are you going to do?” President Cowley answered, “I’m going to release the branch president and put in a new one.” Sid said, “Why don’t you just tell me who the new branch president will be, and then I won’t have to get myself cleaned up for church in the morning.” President Cowley said, “Well, I’ll tell you who it is. It’s going to be you.” Sid had that old cigar in his mouth. He pulled it out and looked at it and said, “Tumuaki, you mean me and my cigar?” President Cowley said, “No, Sid, just you. We don’t need your cigar.” Then Sid threw the cigar out on the ground in front of the porch. He thought for a minute, turned to President Cowley, and very humbly said, “Tumuaki, I don’t break the Word of Wisdom anymore. I’m a full-tithe payer. I’ll be the branch president, and I’ll be worthy. Tomorrow morning I’ll be there, and I promise you that I’ll be the best branch president in the whole country. You won’t have to worry about me and whether or not I’m living the gospel.”

For the next several years, Sid served as one of the strongest and finest leaders in the mission. His son became the first bishop in the ward when the stake was created, and just recently his grandson was released as a bishop and made a stake president. His whole family is strong and active in the Church today and is one of the great families in New Zealand. Why? Because old Sid knew how to repent. He repented on the spot. When he was called to repentance, he quit his worldly ways. He became and remained a faithful Saint until the day he died.

In October 1940, my companion and I picked up a telegram for President Cowley at the post office. We rushed back to the mission home with it, knowing pretty well what it contained. We had been expecting to be called home on account of the war. The missionaries had already been called out of Europe, and we knew our turn was coming. President Cowley read the cable to us and confirmed our suspicions: “RETURN ALL ELDERS TO UNITED STATES SOON AS POSSIBLE.” President Cowley, however, stayed in New Zealand for the next five years for the duration of the war with his wife, Elva; daughter, Jewell; and their little adopted Maori boy, Toni. On his first mission he was in New Zealand for five years during the entirety of World War I. Altogether his two missions comprised thirteen years, and he missed out on both wars!

Fig. 5. Family picture of Matthew and Elva Cowley, daughter, Jewell, and adopted Maori son, Toni Courtesy of Kia Ngawari Trust

Fig. 5. Family picture of Matthew and Elva Cowley, daughter, Jewell, and adopted Maori son, Toni Courtesy of Kia Ngawari Trust

In response to the cable from the First Presidency, we had one week to gather all the missionaries to headquarters to catch the Mariposa. It was a hectic week, but we managed to get everyone into Auckland on time, including the last group of missionaries from Australia who sailed into New Zealand for a one-day layover. The Sunday before we were to leave, President Cowley wanted to hold meetings all day. Priesthood meeting was held with just the missionaries, during which he spoke with great tenderness. He gave excellent instructions on honoring our priesthood and serving the Lord. He hated to see us go home. “Up to now,” he said, “I have been your mission president; but next time I see you, I’ll just be your friend. If any of you have any legal problems or run into difficulty, be sure to call on me. As a friend, I would love to help you.” The rest of the meetings that day were attended by more than five hundred Saints who came to bid the missionaries farewell. Every missionary was called upon to give a short talk in at least one of the meetings.

When the day arrived to leave on the Mariposa, we shook President Cowley’s hand and bid him farewell. My companion and I, who were the secretaries of the mission, were two of the last to leave. President Cowley, however, did not follow us down to the boat. He was “too busy vacuuming” the carpets in the mission home, which he had been doing for the last hour, and just could not quit. How lonely he seemed as we walked away. He was a very tender man. He enjoyed having missionaries around, and he truly loved them.

Several months later President Cowley wrote me a letter and said, in his humorous way, “I now know what was wrong with our mission, why we didn’t do very well and baptize very many. It was you missionaries. You were the ones who were holding up the work. Now that you’re gone, local missionaries and local people are doing better than ever. Tithing and fast offerings have greatly increased, activity in the Church has grown, and I am now convinced where our problem was.”

When in 1945 he finally returned home after nearly eight years in New Zealand, President Cowley wondered what he would do for a living. He had been a lawyer, but he did not have a practice to come back to. Their insurance had lapsed, and they had absolutely no money. They lived for a while with Sister Cowley’s brother. Shortly after their arrival home, October general conference began. I told President Cowley I would pick him up and take him. On the way to the Salt Lake Tabernacle I said to him, “Tumuaki, how are you going to get into the Tabernacle? You don’t have a ticket of any kind.”

“Well, how are you going to get in?” he asked.

I replied, “I’m a bishop, and I’m going to go sit where the bishops sit.”

He said, “Well, last night President George Albert Smith called me and asked me to sit on the front row. Frequently, they have five extra minutes and call on a returned mission president to come up and bear his testimony. If there isn’t any extra time, I’ll probably be called on to pray. So I’m to tell the ushers that I’m supposed to be on the front row.”

So when we arrived at the Tabernacle, he talked his way in. After the opening song and prayer, George Albert Smith was sustained in a solemn assembly as the President of the Church and prophet of the Lord. Next, the names of the Twelve were presented, including Matthew Cowley’s name to fill the vacancy created by the passing of President Heber J. Grant. Matthew Cowley did not know anything about it. None of us did. It was an exciting moment. President Smith knew where he was. He was President Smith’s pride and joy and always had been since he was a little boy. President Smith did not even tell him what was going to happen; he just had him sustained.

Elder Cowley did not know at the time he was called to be an Apostle that Senator Elbert D. Thomas from Utah, who was a very close friend to President Harry S. Truman, was working on the proposition that Matthew Cowley be called by the U.S. government to represent the United States in the New Zealand consulate. It would have been a great assignment for Elder Cowley, and he, no doubt, would have accepted the proposition, except that the Lord had other plans. Instead, President George Albert Smith called him to be an Apostle.

In this new assignment, Elder Cowley still wanted one of his missionaries to travel with him, and I was the one closest at hand. But I did not want to because I had been made a bishop and felt I needed to be home. I did go with him on a few out-of-town trips, but we were together almost every single day that he was in town. He would come to my place of business and wait; then we would almost always go bless someone. I have no idea how many hundreds of people we administered to and blessed, but it was day after day.

Elder Cowley and I used to go into a special part of the County Hospital in Salt Lake to bless all the people with polio. We went time and time again but were never afraid. Polio was a dreaded disease in those days. We would scrub up and put on gowns and hats so all that could be seen were our eyes. Then we would go in and bless the people. They were in iron lungs, on rocking beds, some just in their beds. Elder Cowley had the faith of the brother of Jared. He had the great ability to lift people, to love people, to bless people. We saw marvelous things happen because of the faith of this good man.

On one occasion Elder Cowley received a request from a distressed mother asking if it was possible for him to bless a little girl who had been run over by a car and was left paralyzed. We went to their home in Salt Lake City to bless the little girl. She was unable to see, hear, or speak properly, and was, of course, unable to move her body. In his great and wonderful way, Elder Cowley blessed this little girl to live, to dance and sing and walk and run, and do most things that normal young girls do. A couple of years later, we were invited to the little girl’s home, wherein we saw the result of another great miracle. She sang for us, did a lovely little dance, and displayed the truth that every promise pronounced on her had been fulfilled since the accident.

One day a young cousin of mine was run over by a big city bus; the rear wheels ran over her whole body and crushed her head. My mother called me and said, “Get a hold of Tumuaki and go to the hospital as fast as you can!” So we did. When we got there, the good Latterday Saint doctor said to Elder Cowley, “Don’t bless this little girl to live. If she lives, she will be a vegetable. Her brain has been completely crushed worse than anything you can imagine. Whatever you do, bless her to pass away quickly.” We went in the room. The doctor left us. Elder Cowley said to me, “What do you think we ought to do?” I said. “Well, we came to bless her. We’d better bless her.” So he blessed her. He blessed her to be made well. He blessed her to run and jump and live a normal life, to grow up and to become married and have a family. He poured out upon her the great feelings of love of his heart and gave her promises that were almost impossible to think about. Then we left.

For the next thirty days, he fasted quite frequently. He went to that same hospital room and would spend two or three hours sitting at the bed of that little girl who was about ten or eleven years of age, just praying for her. And they kept wondering why she did not die. They did not fix any of the broken bones. The doctors just did not do anything because they knew she would not last. After several days, more than a month, she moved a couple of muscles. She was still unconscious, of course. They began to work with her. It was not too long before she began to respond. The faith and the fasting of this magnificent man who was God’s noble servant began to pay off.

About two years ago, it dawned on me that this little girl, now a lovely mother of four or five children, had never been told what happened in the hospital. She knew that Elder Cowley and I had been to bless her on many different occasions, but she did not know that he had spent a great deal of time at her hospital bed. She did not know that he had promised her some blessings. I went to see her. I said, “Janice, how bad are you from the accident?” “I’m okay.” “Do you have a lot of scars on your body?” She said, “Not a single scar.” I said, “Do you limp? Do you have any aches and pains?” She said, “Not really.” She is a woman now, over fifty years old. She said, “Just the normal problems.” I told her of her blessing. Then I wrote it down and gave her a copy of what had happened so many, many years ago under the hands of this wonderful man. I shall never forget that miracle.

It got to be that Elder Cowley could hardly go anywhere to bless the people without me or one of the other missionaries. He would come to my office, to my place of business. And I was always busy. We were in the business of selling poultry, and I had to get all the orders out. But he would wait an hour or an hour and a half in my office till I could clean up and go with him to the hospital or to wherever someone was waiting for a priesthood blessing. It was wonderful to know how he loved to bless people. Sometimes the phone would ring at my office. It would be the secretary to President George Albert Smith. She’d say, “Brother Rudd, President Smith’s trying to find Brother Cowley. Have you got him down there?” And I’d say, “Yeah. He’s sitting right here.” “Well, tell him that the President wants him right now.” You know, Elder Cowley was not lazy, but he did not like to stay in his office. He just had to get out of the Church Office Building because he knew of half a dozen people who needed blessings. And so he played hooky an awful lot from office work, and he would come and wait and President Smith knew how to find him. It was wonderful what great teamwork we had in trying to get Elder Cowley back uptown where President Smith could use him.

I used to get after him. I would ask him, “Don’t you have a guilty conscience, Tumuaki, knowing how Brother Lee, Brother Kimball, Brother Benson, and all of them are hard at work up at headquarters, and here you are, sitting here, waiting for me?” He said, “Well, we’re just going to talk about finances today, and I don’t know anything. When I go to the Finance Committee Meeting, all I do is wait and watch for what Brother Lee does. If his hand goes up, I put my hand up. I’m not any good. You know, I don’t even know what a thousand dollars is, and they’re talking about tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, once in a while, even a million dollars. I’m no good in those meetings.”

Elder Cowley had a heart attack about a year and a half after he became an Apostle. He was speaking at Brigham Young University. When he finished, he admitted he was really sick and they got him in a car and rushed him back to Salt Lake City. He would not go to the hospital. Sister Cowley phoned me to come over with another former New Zealand missionary and give him a blessing. Sister Cowley met us at the door and said. “Hurry! He’s in terrible pain.” We went in the bedroom. There was our wonderful mission president. I remember he said, “Hurry, you birds! Give me a blessing.” Well, he usually called us elders, but sometimes we were just birds. Anyway, we gave him a blessing, and immediately the pain was gone. So we stood there and talked to him, and I heard the front doorbell ring. I was closest, so I went to the front door. And there stood the President of the Church, President George Albert Smith. He said to me, “Bishop, is Matt here?” And I said, “Yes, come right in, President.” And I ushered him into the bedroom. When we got in he said, “Matt, I came as fast as I could.” President George Albert Smith loved Elder Cowley, loved him with all his heart. He had called him to be an Apostle. He had helped raise him as a young boy. He traveled with him to New Zealand when President Cowley went there to be the mission president. Anyway, he stood there and said, “Matt, I came to give you a blessing.” Then Elder Cowley did one of the few things he did that was not too bright. He said, “Well, I’ve already had a blessing. These missionaries have just blessed me.” And then President Smith said, “Wouldn’t it be all right if the President of the Church also gave you a blessing?” So he invited us to help him. He then gave a priesthood blessing to this great soul.

Elder Cowley was a humble man, a man who was comfortable living an ordinary life in many ways. When I was in the business of selling baby chicks, early one morning several boxes of chicks arrived, which I was to deliver to American Fork. Since Elder Cowley was to speak at BYU that morning, he invited me to go along and deliver the chicks on the way. When we arrived in American Fork and began carrying in the boxes of baby chicks, the lady of the house almost fainted when she realized that a member of the Quorum of the Twelve was delivering her baby chicks to her—just one of those little things that seemed to happen quite frequently. When his son, Toni, was a teenager, he got a paper route, which he took care of after school. However, because he was often late or otherwise unable to deliver the papers, Elder Cowley soon learned how to deliver the papers and became a reasonably good newspaper boy, even though he was a member of the Twelve. Elder Cowley loved to stop by the poultry processing plant that I owned. In the front by the office was a deep freezer, and we generally filled it with Snelly’s Ice Cream Bars from the Snelgrove Ice Cream Company, which were bought by the dozen. He often stopped in to pick up a couple of Snelly’s, hop back into the car, and be on his way. One day, while on his way to Provo with a carload of men, he stopped long enough to get a Snelly’s for everyone, then waved good-bye to us as he went on his way.

Elder Cowley had been instructed by President Smith not to write his talks out. However, he had the assignment to give the “Church of the Air” talk on one occasion, which had to be perfectly timed. Therefore, he was required to write it all out and give it to Brother Gordon B. Hinckley (not yet a General Authority), who was in charge of the broadcasts. Elder Cowley and Brother Hinckley had quite a debate over the talk. Brother Hinckley insisted that Elder Cowley could not give it in the exact time, and Elder Cowley was sure he could. They wrestled back and forth for a while, and finally Elder Cowley agreed to take a rather large paragraph out of the talk, which made Brother Hinckley happy. However, when he got before the microphone to give the talk, he put the paragraph back in and finished right on time. I am sure he and Brother Hinckley smiled over this unusual occurrence.

As an Apostle, Elder Cowley was assigned to be the president of the Pacific missions of the Church, and so as an Apostle he was able to again travel throughout that part of the world. On one occasion, while attending a district conference in Savai‘i, Sa-moa, he decided to write to his former missionaries: “I am heading off a nervous collapse by writing letters,” he wrote to me in a long letter I still have. “The congregation thinks I’m taking notes; . . . these people are great for blessings. I have blessed more than fifty yesterday and today. . . . Tomorrow I will be walking five miles to the beach, where I will return by launch to Apia [mission headquarters]. Then I’ll be on my way to Tonga, where I will go to Fiji and try to make some connections to visit Tahiti; . . . then I will go back to Honolulu and return home in time for a big chop suey dinner with you and the elders.” [3]

He and Sister Cowley enjoyed nothing more than to get a group of missionaries together and go out to supper, particularly to Chinese restaurants with chop suey. Usually there were enough of us to require two tables, with the men at one table and the women at the other. He had the time of his life when he visited with us and told us his stories. He would visit at the wives’ table—he was wonderful with them—and play little jokes on them and do little things to make them smile. Once he told my wife, Marva, “My, you’re getting better looking all the time. Before you married Glen, you must have been a mess, but now you’re just beautiful!”

In June 1949, while Elder Cowley was in Hawai‘i, he sent me another letter stating that he was leaving Honolulu for Tokyo and that Mira Petricevich from New Zealand was leaving Honolulu for Salt Lake City and would be staying for a month. While she was not a member of the Church, she was a friend of the Church and could continue to assist the Church upon her return to New Zealand. Though still young and single, she was one of the outstanding leaders of the Maori race (in 1951 she became one of the founding leaders of the Maori Women’s Welfare League). He gave instructions on how to meet her and held responsible the Kia Ngawari group (returned missionaries who had served in New Zealand) to assist her while she was in town by finding her a place to stay and having her meet the general Relief Society president Belle Spafford and Elder Spencer W. Kimball, as well as some of the First Presidency, if possible, and the leading men in the welfare committee. He scribbled an additional note to me: “Take her to my office and show her where I am supposed to be working.” He insisted we should show her a good time and see that her trip was “financed with means I have raised.” On that score, he urged me to get my brother Sam “to ante in a little.” He also asked about his favorite baseball team: “How are the Pittsburgh Pirates doing?” [4] I never knew what he would have us do next, but we were usually able to assist him.

While in the Hawaiian Islands, Elder Cowley visited a small settlement in Moloka‘i, known as Kalaupapa, which was a leper colony. About that occasion, he wrote: “I flew over there to spend an afternoon with our leper Saints. It was my first experience with those people. I went there expecting and apprehending that I would be depressed. I left there knowing that I had been exalted. I attended a service with those people. I heard a chorus sing our beautiful anthem, conducted by an aged man, blinded by the dread disease. I heard them sing ‘We Thank Thee, O God, for a Prophet,’ and as long as I live, that song will never ring in my soul with such beautiful harmony as came from the hearts and the voices of those emaciated lepers of that colony.” [5]

About two months before Elder Cowley died, he had a little sickness, and then he had to miss a couple of conference assignments. He went to the doctor, and the doctor said to him, “You’re all well.” His doctor was his brother-inlaw and gave him a good physical. Elder Cowley said to me, “The doctor says there’s not a thing wrong with me, but he doesn’t know. He doesn’t know what I know. I’m not going to live very long!” That was in November 1953. He said, “The Lord and I have made an agreement, and I’m not going to stay on the earth very long.” And I said, “Oh, Tumuaki, you’re just tired. You’ll be okay.” He said, “No.”

Time and again during the next few weeks he told me that he was going to die. I am amazed, as I look back, at the many times we debated the length of his life. On December 3, 1953, he went to Logan to participate in a panel discussion at Utah State University and insisted that I take him. I was busy in the turkey business and did not want to leave, but he insisted. So we left early that morning and drove to Logan. All the way up he talked to me about his life. As we returned home he asked me to take care of a couple of things after he died. When we got to Salt Lake, he suggested that we go get a bowl of soup at a Chinese restaurant. We sat in the back booth until almost midnight, when the owner finally asked us to please go home so he could close up. Elder Cowley had a lot of things to tell me that day, and I must confess that he had me convinced that he knew what he was talking about.

He knew exactly how he would die and that he would go at the normal time he woke up every morning, about five o’clock. “I will get a good night’s sleep,” he said. “I’m not going to the other side all tired out. When I go to bed at night, I’ll give my wife an extra big kiss, get into bed, and go to sleep. If I wake up on this side, I’ll do what President McKay tells me to do. If I’m on the other side, there’ll be someone there to give me orders. So what difference does it make?” I told him I would not sleep at night if I knew I was going to die. And he said, “Oh yes, you would; you know as well as I do that life is eternal.”

On December 12, Elder Cowley went with the other General Authorities to Los Angeles to lay the cornerstone for the Los Angeles Temple. That was on a Saturday. He had a wonderful time and a good night’s sleep. At nearly five o’clock the following morning, Elder Cowley took a big, deep breath, then quit breathing. Sister Cowley was awake and realized that he was no longer breathing. She pounded on the door to the next room, and President and Sister Kimball came in, but it was too late. Matthew Cowley was gone, just exactly as he had said. Without fear or anxiety, this great and wonderful man slipped to the other side.

When he passed away he was only fifty-six years of age, a very much loved and honored Apostle of the Lord. As I said in the beginning, Matthew Cowley was an unusual man: simple, uncomplicated, ordinary, and wonderful. He was not the greatest man I have known—nor the smartest, best organized, or the best leader or hardest worker. He did a lot of wonderful things but in a Polynesian style. But of all the men I have ever known, I have never known one with more faith.

Notes

[1] Quoted in Henry A. Smith, Matthew Cowley: Man of Faith (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1954), 31.

[2] See Smith, Matthew Cowley: Man of Faith, 42.

[3] Private communication in author’s possession.

[4] Private communication in author’s possession.

[5] [Matthew Cowley], Matthew Cowley Speaks (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1954), 45.