Kerry Muhlestein, “Seeking Divine Interaction: Joseph Smith’s Varying Searches for the Supernatural,” in No Weapon Shall Prosper: New Light on Sensitive Issues, ed. Robert L. Millet (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 77–91.

Some have asserted that Joseph Smith’s early life was full of superstitious beliefs and greedy practices. They insist that his claims to have found golden plates are but the latest of his many fanciful tales and escapades. For some, the idea that Joseph Smith may have sought for treasure using supernatural means makes them wonder if he could discern between things from God and things of the imagination. While the sources are confusing, a careful consideration reveals a boy who believed God cared about him and would be part of his life, a boy who sought for God and found him, a boy who was put through trials that were designed to make him into a great prophet.

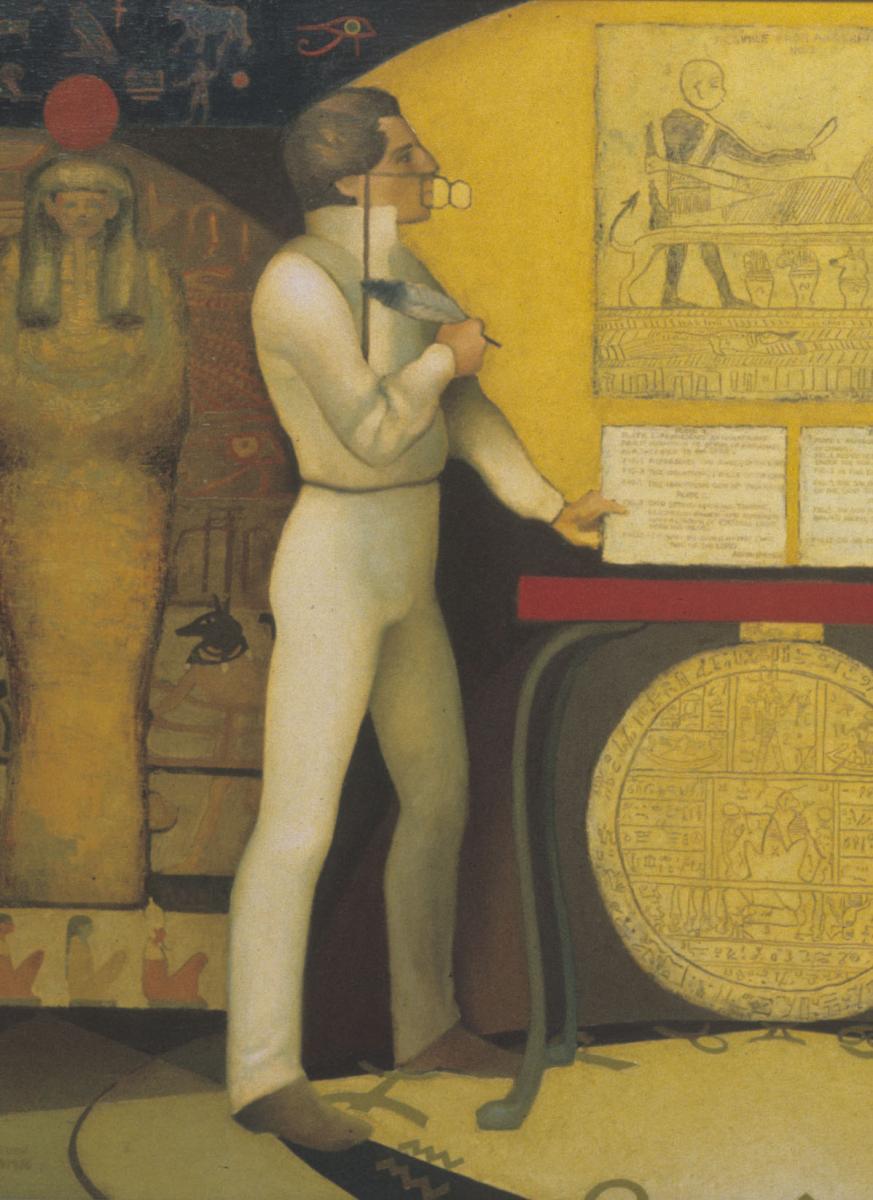

An artist's rendition of Joseph Smith using the Urim and Thummim. (Gary Ernest Smith, The Prophet and the Critic. Courtesy of Church History Museum, Salt Lake City.)

An artist's rendition of Joseph Smith using the Urim and Thummim. (Gary Ernest Smith, The Prophet and the Critic. Courtesy of Church History Museum, Salt Lake City.)

The Prophet Joseph Smith’s revelatory experiences were more varied, rich, and complex than any of us fully realize. We understand very little of how visions rolled “like an overflowing surge before [his] mind,” [1] and we may be at times uncomfortably surprised as we learn about some of Joseph’s revelatory undertakings.

Evidence suggests that Joseph Smith and others in his family had engaged in supernatural practices, some of which were aimed at discovering treasure. The bulk of this activity seems to have occurred between the First Vision and the reception of the plates from Moroni in 1827. Affidavits collected from neighbors of the Smith family in the 1830s mention both Joseph and Father Smith performing supernatural rituals to find treasure. Among the supernatural aids supposedly employed was a seerstone that was later used, along with the Urim and Thummim, to translate the Book of Mormon.

For some, this puts into question Joseph Smith’s claims to have interacted with God and angels. Treasure seeking is a magical practice seemingly out of keeping with prophetic revelation. Why would Joseph not be able to tell the difference between bona fide spiritual experiences and fraudulent ones? If he could not, are any of his spiritual experiences credible?

Truth versus Falsehood

“Was not Joseph Smith a money digger?” Yes. So said the Prophet himself in the Elders’ Journal. [2] However, the imputations of all manner of interaction with the supernatural in his pursuit of treasure are not nearly so credible as the Prophet’s above statement. Witnesses accused Joseph and his family of searching for gold and silver [3] in the form of watches, [4] bars, plates, coins, candlesticks, and so forth [5] by means of a seerstone, [6] protective circles, [7] protective swords, [8] animal sacrifices, [9] divining rods, [10] fortune-telling, [11] and close attention to special days and the phases of the moon. [12] Some believed that Hyrum owned magical parchments [13] and a ritual dagger [14] and that Joseph utilized an astrological Jupiter talisman right up to his martyrdom. [15] Others have claimed that Joseph originally described the golden plates as a treasure left by Captain Kidd that was guarded by a supernatural ghost and that, over time, the tale evolved into a religious story involving the angel Moroni. [16]

What are we to make of these claims? How are we to determine what is reliable and what is not? Some assertions are almost certainly true and stem from those who were closest and most friendly to the Prophet and his family. Some claims are easily dismissed. Yet the veracity of other reports is so muddled and byzantine it is almost impossible to detect truth from falsehood.

What Did Joseph Smith Do?

Examples of speculative critiques include allegations of a magical dagger, parchment, and talisman and the transformation of a treasure ghost into the angel Moroni. While Hyrum may have possessed an ornate dagger (the ownership is not clear), many people in his day had something similar. None of those who accused the family of magical involvement say anything about a dagger in their detailed descriptions of treasure seeking, and there is no evidence that it was seen as anything but a beautiful and useful knife. [17] Attempts to demonstrate more than this have fallen short, [18] and even if Hyrum held some superstitious beliefs about the knife it would make little difference. One day we may very well look back at our own lives with chagrin about some superstitions we unknowingly carry. They have little to do with our belief in correct principles. Similar problems exist with assertions made regarding the parchment and talisman. [19] These claims are just unsubstantiated.

Likewise, a careful analysis of the documents involved show that Moroni was represented as an angel even in the earliest accounts. [20] Statements by Joseph’s enemies describing Moroni as a treasure ghost arose in 1830 and grew from there; [21] it was these stories that evolved and changed over time, not descriptions of Moroni as an angel. [22]

While good research clarifies the above claims, in other allegations the evidence is so convoluted that no amount of study will yield a sure conclusion. Records of an 1826 trial and the 1833 affidavits against Joseph Smith comprise the bulk of the allegations that Joseph trafficked in the supernatural while searching for treasure. Many aspects of these documents argue against their veracity while others support it.

In the fall of 1833, D. P. Hurlbut arrived in Palmyra searching for accounts of Joseph Smith’s early history and character. [23] Hurlbut had been excommunicated, put under restraining order to prevent him from harming Joseph Smith, and was hired by an anti-Mormon group to collect testimonies that would verify the views of that group. The people he interviewed told stories about Joseph Smith Sr. and Jr. using all kinds of supernatural aids in their quest for treasure. Some of the most bizarre of these tales include finding the treasure by means of a seerstone [24] or divining rod; [25] creating magic circles with metal stakes, [26] witch hazel stakes, [27] or even the blood of sacrificed sheep; [28] and of finding treasure that kept moving through the ground of its own volition so that it could never quite be grasped. [29] Some also spoke of young Joseph using his stone to tell fortunes. [30]

While space does not permit a full analysis of Hurlbut’s recorded interviews, it must be acknowledged that there are a number of historical problems with these affidavits. First of all, they bear a striking resemblance to Abner Cole’s satirical, fanciful report of treasure seeking in the Book of Mormon, [31] and to a newspaper account of a different Smith family from Rochester, New York. [32] Moreover, inconsistencies among the statements and among later interviews cast some doubt on the authenticity of the affidavits. [33] For example, William Stafford claimed to have known the Smiths quite well. He provided stories about the Smiths using witch hazel stakes and the blood of a sheep while looking for treasure. [34] However, when asked about Stafford’s statement, his son (who was Joseph’s age) claimed that his father was not connected with the Smiths in any way, and that he did not believe the story about the sheep was true. [35] Many interviews and statements gathered from the Smith neighbors by less hostile interviewers paint a very different picture of the family than those gathered by Hurlbut. [36]

Such problems with sources make it difficult to know what information from the affidavits we can trust. Yet confirming testimonies from Latter-day Saint witnesses lend validity to some of the Hurlbut reports. For example, Joshuah Stafford writes “Joseph once showed me a piece of wood which he said he took from a box of money, and the reason he gave for not obtaining the box, was, that it moved.” [37] Later reports by Latter-day Saints in Utah claimed that, while treasure hunting with Joseph, Martin Harris and Porter Rockwell grabbed the lid of a chest, which slid away from them. A fragment of the lid broke off, and they kept it as a prized relic for years. [38] Brigham Young believed this story. [39] Other affidavits speak of Joseph finding gold watches, [40] and later Church members who knew Joseph also held this to be true. [41] It seems then, that there is some accuracy in the affidavits. What are we to make of these contradictory ideas? Are the affidavits reliable or not? Can we use them as evidence?

Similar questions apply to the records concerning an 1826 trial in which Joseph Smith was accused of disorderly conduct—specifically for trying “to discover where lost goods may be found.” [42] The only fully original documents we have from the trial are the bills from the justice of the peace who heard the case and from the constable who brought Joseph to trial. There are three main accounts of the proceedings: (1) an account published nearly one hundred years later, purportedly from pages the justice’s niece ripped from his trial docket book—though no one has been able to produce the actual pages, (2) a publication in Fraser’s Magazine similar but not identical to the account produced by Justice Neely’s niece, and (3) a reminiscence offered fifty years later by Dr. W. D. Purple (who wrote that he was asked to take notes at the court by Justice Neely) which also has distinct variations from the above documents. These accounts disagree about the number, names, and order of the witnesses, and even about the verdict. The evidence from these accounts and the bills have been used to demonstrate both that Joseph was found guilty [43] and that he was acquitted. [44] Further, none of these accounts pretend to be objective, they all include judgments which convey the authors’ harsh perception of the Smiths. This clear bias, the contradictions between the accounts, the lack of original documentation, and the lengthy period between the trial and the creation of any of the extant annals casts doubt on the reliability of these records.

Yet Justice Neely’s actual bill and a later account show that the justice charged $2.68 for his services, a precision that indicates some degree of accuracy. Furthermore, while the three main sources are decidedly anti-Mormon, they all record the strong testimony of Josiah Stowell in behalf of Joseph. His testimony and those of Joseph Smith Sr. and Jr. seem to accord with what we know of the men who made them. For example, Stowell avowed that he knew for certain that Joseph could see things in his seerstone. As proof he testified that when he traveled from Pennsylvania to Palmyra in order to enlist Joseph’s services, he tested Joseph’s ability as a seer. Joseph looked into his stone and described Stowell’s house, outhouses, and a tree with a hand painted on it. [45] When the Justice asked Stowell if he believed Joseph could use the stone to fifty feet below the ground, Stowell replied, “Do I believe it? No, it is not a matter of belief. I positively know it to be true.” [46] Stowell’s actions—employing Joseph and following the Prophet faithfully throughout his life—seem congruent with this statement.

The informal trial notes describe Joseph Jr. saying that when he looked in the seerstone “time, place and distance were annihilated, that all the intervening obstacles were removed, and that he possessed one of the attributes of Deity, an All-seeing-Eye.” [47] These statements are reminiscent of things he said later in life. [48]

According to Dr. Purple’s trial account, Joseph Smith Sr. testified that “both he and his son were mortified that this wonderful power which God had so miraculously given him should be used only in search of filthy lucre, or its equivalent in earthly treasures, and with a long-faced, ‘sanctimonious seeming,’ he said his constant prayer to his Heavenly Father was to manifest His will concerning this marvelous power. He trusted that the Son of Righteousness would some day illumine the heart of the boy, and enable him to see His will concerning Him.” [49] The timing of the rise and fall of treasure seeking in the Smith family seems to confirm the accuracy of these sentiments. Undoubtedly there is some truth in the trial notes, but it is difficult to know what to trust in these problematic documents.

Sifting the Evidence

Given the problems with the affidavits and trial documents, how can we determine what Joseph Smith did in regards to seeking supernatural aid while searching for treasure? The stories behind the documents are so complex that it seems impossible to use them to reconstruct an accurate picture. While the task may seem overwhelming, in actuality there is no point in quibbling over which lines from which documents are trustworthy. There is, however, evidence enough from those close and sympathetic to the Prophet, and from the Prophet himself, to get a general impression of what he did.

Undoubtedly, Joseph helped Josiah Stowell search for treasure, and Josiah sought Joseph’s services because of his abilities as a seer. We have already noted that friends believed Joseph found gold watches and was able to grab part of a treasure chest. Many reports also agree that Joseph used multiple seerstones for a variety of purposes. [50] This is probably what Joseph’s mother was referring to when she said that Josiah Stowell sought out Joseph’s services because he had “heard that [Joseph] ‘possessed certain means [she says “certain keys” in other editions] [51] by which he could discern things invisible to the natural eye.’ ” [52] Martin Harris tells an interesting story about Joseph’s use of the stone. Harris was once picking his teeth with a pin when he dropped the pin into some straw. When no one could find it, he asked Joseph to use his seerstone. “He took it and placed it in his hat—the old white hat—and placed his face in his hat. I watched him closely to see that he did not look one side; he reached out his hand beyond me on the right, and moved a little stick, and there I saw the pin, which he picked up and gave to me. I know he did not look out of the hat until after he had picked up the pin.” [53]

Many accounts agree that Joseph could not receive the plates for some time because he associated them with obtaining worldly wealth. [54] Joseph himself describes his first attempt—a failure—to get the plates thus: “I had been tempted of the advisary and saught the Plates to obtain riches and kept not the comandment that I should have an eye single to the glory of God therefore I was chastened.” [55] His mother and Oliver Cowdery both recorded that Joseph could not obtain the plates because he wondered what other valuable things might be in the box. [56] Martin Harris said that Moroni told Joseph he had to quit the company of the money diggers and have nothing more to do with them. [57]

Thus, while examining the trial documents and affidavits may be a worthwhile historical endeavor, in many ways it is just quibbling over the exact manner and extent of Joseph’s treasure seeking efforts. Reliable sources agree that Joseph sought supernatural aid in looking for treasure, and that his desire for treasure was something he had to overcome in order to receive the plates.

Joseph’s Situation

To properly assess Joseph’s activities, we have to understand Joseph’s situation. First, we must understand that Joseph and his family were desperately poor. They had suffered a series of devastating financial setbacks, [58] and it was during the years when Joseph was trying to obtain the plates that they lost their farm. [59] The financial needs of the family must have pressed relentlessly on the minds of Father Smith and his namesake. For them, every event in life was no doubt evaluated in terms of how it impacted the survival of their family.

Second, Joseph was part of a culture that fervently believed experiences with God could be a part of an individual’s life, and that seeking God’s help while searching for treasure was a viable part of Christianity. While this was a part of their religious heritage, [60] it was also a folk-religion reaction against ongoing Protestant movements that largely denied personal interaction with God, especially in tangible forms. [61] Joseph’s struggles to demonstrate that God continued to reveal himself in the lives of men began during this time period and lasted his entire life. Trafficking in the supernatural while searching for treasure was prevalent during his day and in his area, [62] and the participants viewed their activities as a genuine expression of Christianity. [63] Ministers were frequently involved, [64] as were prayer circles [65] and other Christian activities, [66] including the use of divining rods in establishing churches. [67] Those whose religious bent was to put God in a distant sphere castigated those who sought daily interaction with God through such practices, accusing them of employing magic. [68] Many negative characterizations of Joseph Smith reflect and are colored by this cultural conflict.

Joseph’s methods of interacting with the divine may seem strange to us, but this is largely because we are more cultural inheritors of the Protestant movement to remove God from daily life than we are of the folk religion of Joseph’s day. However, as Joseph consulted the Bible, he would have found instances of divining instruments; they were far from unfamiliar in a biblical culture. If David enquired of the Urim and Thummim (seerstones) for directions concerning military strivings (see 1 Samuel 30:7–8), could Joseph not inquire of a seerstone regarding the financial struggles of his family? If Joseph of Egypt used a silver cup for divining (see Genesis 44:5), and the book of Revelation records the use of white stones in receiving revelation (see Revelation 2:17; D&C 130:10–11) couldn’t Joseph also use a seerstone? After all, the Lord said he would prepare “Gazelem, a stone,” which would enable hidden knowledge to come forth (Alma 37:23). [69] If Jacob could use stakes to encourage the fertility of cattle, and Moses could use a rod to bring water to the Israelites, couldn’t divining rods be an appropriate means of communication with God for those who sincerely seek him? (Incidentally, appropriate interaction with God through rods was confirmed by God himself in his revelation to Oliver Cowdery, wherein Oliver was told, according to the earliest versions of Doctrine and Covenants section 6, that he had communed with God through a rod. [70] Similarly, in the earliest versions of section 8, when Oliver was told he had a gift for working with a rod, the rod was originally referred to as a sprout. When the rod was mentioned again, the earliest versions call it “this thing of nature.” [71] It would seem that Oliver had been using some kind of stick in a manner similar to a seerstone.) Is there a real difference between Nephi being told where to hunt through a brass ball and God helping those who believe find lost cows through a rod, or lost pins through a seerstone? Will God direct those who honestly turn to him in whatever manner they expect, or must he always give revelation through a fleece laid on the ground ( Judges 6:36–40)? [72]

In the end, the questions that really bother us may boil down to wondering if Joseph sought for treasure and if he used supernatural means to do so. And, if the answer to these questions is yes, we must ask ourselves if that disqualifies him as a prophet. Is it possible that after seeing God in the grove, Joseph felt he had a special relationship with the divine? And what if, after this experience, he still found the destitute poverty of his family an oppressive need, and he thought that his proven ability to communicate with God might help his family out of their impoverished circumstances? Would such a hope make his later claims to translate by the gift and power of God unbelievable?

It seems to me that there is another, more important question. Shouldn’t we expect the kind of youth who actually believes he can enter a grove of trees and receive an answer to his questions from God to also be the kind of youth who believes that God interacts with his children in their daily lives? Isn’t the characteristic that drove Joseph to the grove, and later to his knees the night Moroni came, the same quality that would lead him to seeking God’s help in all kinds of other things? Should we expect God to refuse interaction with such a youth because he was seeking God in ways not familiar to us? Is it possible that Joseph’s youthful employment of seerstones was a training ground for the great work he would later undertake? Perhaps it happened as Elder Oaks suggested when speaking of Joseph’s possible use of seerstones in searching for treasure: “Line upon line, young Joseph Smith expanded his faith and understanding and his spiritual gifts matured until he stood with power and stature as the Prophet of the Restoration.” [73]

It seems that the great tutorial and test for Joseph was to learn to use his gift only to build the kingdom of God, not for personal reasons. Should we expect him to have passed this test at age fourteen, or should we expect it to have taken years to school himself to the point of only using his gift of interaction with the divine for seeking the glory of God?

I think that Joseph Smith possessed a heartfelt belief that God cared about him and would be a part of his life. This caused him to seek God’s help in a variety of ways concerning a variety of things. It is this belief that led him to seek God in a secluded grove of trees, and thus I am personally grateful that Joseph possessed this quality, regardless of other ways it manifested itself.

Notes

[1] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957), 5:362.

[2] Elders’ Journal 1, no. 2 (1838) 29.

[3] See Joseph Capron Statement, Roswell Nichols Statement, and Peter Ingersoll Statement in Dan Vogel, ed. Early Mormon Documents, vol. 2 (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1998), 24, 38, 41 (hereafter cited as EMD).

[4] See Joseph Capron Statement and Joshua Stafford Statement in EMD, 2:24–25, 28.

[5] See William Stafford Statement in EMD, 2:60.

[6] See Peter Ingersoll Statement, William Stafford Statement, and Willard Chase Statement in EMD, 2:41, 60–61, 65–66.

[7] See Joseph Capron Statement and William Stafford Statement in EMD, 2:25, 60–61.

[8] See Joseph Capron Statement in EMD, 2:25.

[9] See William Stafford Statement in EMD, 2:61.

[10] See Peter Ingersoll Statement in EMD, 2:40–42.

[11] See David Stafford Statement and Henry Harris Statement in EMD, 2:57, 75.

[12] See William Stafford Statement in EMD, 2:60.

[13] D. Michael Quinn, Early Mormonism and the Magic World View, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1998), 97.

[14] Quinn, Early Mormonism, 70–71.

[15] Quinn, Early Mormonism, 71–83.

[16] See Ronald V. Huggins, “From Captain Kidd’s Treasure Ghost to the Angel Moroni: Changing Dramatis Personae in Early Mormonism,” in Dialogue 36 (Winter 2003): 17–42; Dale Morgan on Early Mormonism: Correspondence and New History, ed. John Phillip Walker (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1986), 266–75; and Quinn, Early Mormonism, 136–77. See also Dan Vogel, Joseph Smith: The Making of a Prophet (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2004), 35–52; John L. Brooke, The Refiner’s Fire: The Making of Mormon Cosmology, 1644–1844 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 152–56; Pomeroy Tucker, Origin, Rise, and Progress of Mormonism (New York: Appleton, 1867), 19–26; Fawn M. Brodie, No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith the Mormon Prophet, 2nd ed. (New York: Knopf, 1971), 16–21; and Marqardt and Walters, Inventing Mormonism: Tradition and the Historical Record (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1994), 63–77, 89–106.

[17] See William J. Hamblin, “That Old Black Magic,” in FARMS Review 12, no. 2 (2000): 77.

[18] See Stephen E. Robinson, “Review of Michael D. Quinn, Early Mormonism and the Magic World View,” in BYU Studies 27, no. 4 (1987): 91; and Hamblin, “Black Magic,” 65–77.

[19] See Robinson, “Review of Michael D. Quinn,” 91–92; and Hamblin, “Black Magic,” 95–99.

[20] See D&C 20:6 (composed at least by early June 1830, and first printed in “The Mormon Creed,” Painesville Telegraph, April 19, 1831, 4); “Testimony of the Three Witnesses” printed in The Book of Mormon, and composed mid-1829; and a hostile letter from Jesse Smith written in June of 1829 that refers to an 1828 account of the angel, as reproduced in Larry E. Morris, “I Should Have an Eye Single to the Glory of God,” FARMS Review 17, no. 1 (2005): 51; also printed in Mark Ashurst-McGee, “Moroni: Angel or Treasure Guardian?”, in Mormon Historical Studies 2, no. 2 (2001): 52. For other early sources, including letters and articles, see Morris, “Glory of God,” 30 and 51–53 as well as Ashurst-McGee, “Moroni,” 50–53.

[21] See Morris, “Glory of God,” 27; Ashurst-McGee, “Moroni,” 48–51; and Hamblin, “Black Magic,” 58–60.

[22] See Hamblin, “Black Magic,” 60; Ashurst-McGee, “Moroni,” 53; Morris, “Glory of God,” 33.

[23] Richard Lloyd Anderson, “Joseph Smith’s New York Reputation Reappraised,” BYU Studies 10, no. 3 (1970): 2.

[24] See Peter Ingersoll Statement and Willard Chase Statement in EMD, 2:41, 65–66.

[25] See Peter Ingersoll Statement in EMD, 2:41–42; see also Mark Ashurst-McGee, A Pathway to Prophethood: Joseph Smith Junior as Rodsman, Village Seer, and Judeo-Christian Prophet (master’s thesis, Utah State University, 2000), 122–38.

[26] See Joseph Capron Statement in EMD, 2:25.

[27] See William Stafford Statement in EMD, 2:61.

[28] See William Stafford Statement in EMD, 2:61.

[29] See William Stafford Statement in EMD, 2:61.

[30] See Henry Harris Statement in EMD, 2:75.

[31] See Henry Harris Statement in EMD, 2:75.

[32] See Morris, “Glory of God,” 26; and Rochester Gem, May 15, 1830, in Morris, “Glory of God,” 46–47.

[33] Hamblin, “Black Magic,” 61–62, 66.

[34] Hamblin, “Black Magic,” 61–62, 66.

[35] John Stafford interview with William H. Kelley in EMD, 2:120–22. See also Anderson, “Joseph Smith’s New York Reputation,” 10.

[36] See the Kelley collection in EMD, 2:81–164; and Anderson, “Joseph Smith’s New York Reputation,” 2–3. For other problems with the affidavits, see Robert Woodford on the Smith family reputation, also in this volume.

[37] See Joshua Stafford Statement in EMD, 2:27–28.

[38] Jensen as cited in Ronald W. Walker, “The Persisting Idea of American Treasure Hunting,” in BYU Studies 24, no. 4 (1984): 444.

[39] Brigham Young and others, “Trying to Be Saints—Treasures of the Everlasting Hills—The Hill of Cumorah, etc.,” Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1878), 19:37–39.

[40] See Joseph Capron Statement and Joshua Stafford Statement in EMD, 2:24–25, 28.

[41] See Charles C. Richards, “Address Delivered in Hawthorne Ward, Sugar House Stake, Salt Lake City, Utah,” April 20, 1947, in Walker, “Persisting Idea,” 447.

[42] Revised Laws of New York (1813), 1:114, sec. I, as quoted in Gordon A. Madsen, “Joseph Smith’s 1826 Trail: The Legal Setting,” BYU Studies 30, no. 2 (1990): 93.

[43] William D. Purple Reminiscence in Dan Vogel, EMD, 4:127–28. Also see Wesley P. Walters, “Joseph Smith’s Bainbridge, N.Y., Court Trials,” Westminster Theological Journal 36 (Winter 1974): 123.

[44] Madsen, “Joseph Smith’s 1826 Trail,” 91–108; Oliver Cowdery to William Phelps, October 1835, in Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate, October 1835, 46; also see Kirkham, New Witness, 1:105.

[45] See Shaff-Herzog Encyclopedia entry, reproduced in Kirkham, New Witness, 2:361.

[46] See Joseph Smith, Historical Reminiscences of the Town of Afton, reproduced in Kirkham, New Witness, 2:366.

[47] See Purple, in Kirkham, New Witness, 2:365.

[48] History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1978), 4:597.

[49] Purple, in Kirkham, New Witness, 2:366.

[50] Vogel, EMD, 2:65–66; Kirkham, New Witness, 2:365; for Wilford Woodruff and Brigham Young accounts, see Richard Lloyd Anderson, “The Mature Joseph Smith and Treasure Seeking,” BYU Studies 24, no. 4 (1984): 538; see also Ashurst-McGee, Pathway to Prophethood, 182–92.

[51] Anderson, “Mature Joseph,” 492.

[52] Lucy Mack Smith, History of Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1958), 92.

[53] Joel Tiffany, “Mormonism,” Tiffany’s Monthly, May 1859, reproduced in Kirkham, New Witness, 2:377.

[54] For an example, see Joseph’s own account in Joseph Smith—History 1:46.

[55] 1832 History, in Dean C. Jessee, Personal Writings of Joseph Smith, rev. ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1984), 13.

[56] Lucy Mack Smith, History of Joseph Smith, 83; Oliver Cowdery to William Phelps, October 1835, in Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate, 40; also in Kirkham, New Witness, 1:97.

[57] Tiffany’s Monthly, in Kirkham, New Witness, 2:318, and EMD, 2:309.

[58] Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Knopf: 2006), 46–48.

[59] See BYU Studies 46, no. 4 (2007): 9; Bushman, Joseph Smith and the Beginnings of Mormonism (Chicago: University of Illinois Press), 64–68.

[60] Stephen J. Fleming, “The Religious Heritage of the British Northwest and the Rise of Mormonism,” Church History 77, no.1 (March 2008): 75, 87, 92.

[61] Spencer J. Fluhman, Anti-Mormonism and the Making of Religion in Antebellum America (PhD dissertation, University of Wisconsin–Madison, 2006), 6; Fleming, “Religious Heritage,” 78, 81–82, 93–93, 103; Taylor, “The Context of Joseph Smith’s Treasure Hunting,” 141, 142; Walker, “Persisting Idea,” 430.

[62] Walker, “Persisting Idea,” 448, 452; Alan Taylor, “The Early Republic’s Supernatural Economy: Treasure Seeking in the American Northeast, 1780–1830,” American Quarterly 38, no. 1 (Spring 1986): 7, 9–10, 23.

[63] See Fleming, “Rise of Mormonism,” 87, 92–93; Richard L. Bushman, “The Mysteries of Mormonism,” Journal of the Early Republic 15, no. 3, Special Issue on Gender in the Early Republic (Autumn 1995): 505; Taylor, “Context of Joseph Smith’s Treasure Hunting,” 146; Taylor, “Supernatural Economy,” 17, 22; Walker, “Persisting Idea,” 430, 434, 441, 452.

[64] Taylor, “The Context of Joseph Smith’s Treasure Hunting,” 147; Taylor, “Supernatural Economy,” 23–24; Walker, “Persisting Idea,” 450; Fleming, “Religious Heritage,” 95.

[65] Walker, “Early Mormonism,” 450; Taylor, “Supernatural Economy,” 18.

[66] Walker, “Persisting Idea,” 441, 450–51; Taylor, “Supernatural Economy,” 18; Anderson, “Mature Joseph,” 524.

[67] Walker, “Persisting Idea,” 450.

[68] Fluhman, Anti-Mormonism, 6, 9; Taylor, “The Context of Joseph Smith’s Treasure Hunting,” 145; Ashurst-McGee, “Moroni,” 3, 18.

[69] Moreover, Joseph intimates that God’s knowledge of all things stems at least partially from the fact that he resides on a great Urim and Thummim. See D&C 130:7–8.

[70] See D&C 6:10–17. In the original publication of these verses it spoke of both Oliver’s gift and of his use of a rod. See Anderson, “Mature Joseph,” 521, 524, 527–30; Richard L. Bushman, “Treasure Seeking, Then and Now,” Sunstone (September 1987): 6; and Morris, “Glory of God,” 35–37.

[71] Robin Scott Jensen, Robert J. Woodford, and Steven C. Harper, eds., Revelations and Translations: Manuscript Revelation Books, vol. 1 of the Revelations and Translations series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: The Church Historian’s Press, 2009), 17.

[72] Dallin H. Oaks, “Recent Events Regarding Church History and Forged Documents,” Ensign, October 1987, 65, said, “It should be recognized that such tools as the Urim and Thummim, the Liahona, seerstones, and other articles have been used appropriately in biblical, Book of Mormon, and modern times.”

[73] Dallin H. Oaks, “Recent Events Regarding Church History and Forged Documents,” Ensign, October 1987, 65.