Brazil: Spreading the Message

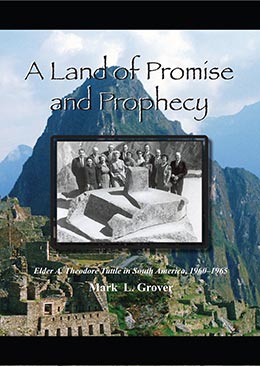

Mark L. Grover, "Brazil: Spreading the Message," in A Land of Promise and Prophecy: Elder A. Theodore Tuttle in South America, 1960–1965 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2008), 108–52.

William Grant Bangerter was excited to return to Brazil. When President Stephen L. Richards of the First Presidency called in October 1958 to set up an appointment to visit, Bangerter felt impressed he would be returning to Brazil. He knew President Asael T. Sorensen had been in Brazil for several years as president of the Brazilian Mission and a change in leadership would probably occur soon. The possibility of going back to his old mission to direct the missionary work in Brazil was something he was pleased to accept. His mission prior to World War II was a time pleasantly remembered often, since he met with a group of former missionary friends almost on a monthly basis. His wife, Geraldine (Geri), and their children were excited at the prospect of going to a place they had heard so much about.[1]

William Grant and Geraldine Bangerter.

William Grant and Geraldine Bangerter.

There were concerns, however. His mission to Brazil from 1939 to 1941 had been unusually challenging in spite of his love for the country and the people. At that time the Church was struggling to change the language of the mission from German to Portuguese. The missionaries were faithful and worked hard but experienced only limited success. President Bangerter had seen few baptisms result from nearly three years of work. Most of the branches were new, and there was not enough local leadership to direct the work. Many of the faithful members were female and could not provide priesthood leadership for the Church. The missionaries did almost everything. Bangerter had followed the development of the Church in Brazil since his mission, and though things had improved he didn’t believe there was significant difference in Brazil from the time of his mission to 1958, at least not as much as hoped.

These thoughts left him with persistent doubts. Was Brazil part of the Lord’s plan? He knew the stories of the missionaries who had gone to Europe in the mid—and late—1800s and baptized thousands. It was obvious the Spirit of the Lord had moved upon those European lands and the result was a harvest of souls that became the foundation for the Church in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. As a missionary he wondered where that Spirit was when he walked the streets of Brazil for three years with limited success. He was confused, and he was not sure Brazil was supposed to be a significant participant in the gathering: “We knew that it is necessary to present the message before all nations, but we don’t really expect that many people will respond anymore. The gathering is really over; we’re doing the gleaning now. If anyone wants to come, we’ll wave the message before them, and they’ll respond if they have the right spirit and the blood of Israel.”[2]

President Bangerter did not want to go back to Brazil as a gleaner. He wanted to go to establish the foundations of the kingdom of God in a land he loved. So concerned was he that soon after his call he went to his knees seeking an answer: “Father in Heaven, do you really intend to organize and establish a strong branch of the Church and kingdom in Brazil? Are we really serious about it down there?” The answer was immediate and powerful. He was inspired to go to the Book of Mormon and read the numerous passages that were directed to the Gentiles. “So many passages came to mind concerning the message to the Gentiles, and I was immediately informed by the Spirit that it didn’t matter whether they belonged to the house of Israel or not. The gospel was for them.” In this experience his questions were answered, and he was anxious and happy to return to Brazil, not only because it was a place he loved but because of the potential that lay ahead for the Church. “It gave me a sense of testimony and a feeling of destiny that has never has been questioned in my life since. And the developments have born out to the testimony. Where I would have thought up to that point that Brazil would be the least responsive of all nations in South America, it turned out in fact to be the most responsive.”[3]

Brazil

Brazil is different from the rest of South America. First, there is the language. Brazilian Portuguese, which has the same linguistic roots as Spanish, is different enough from Spanish that the two are not mutually understandable. Then there is the size of the country. It has almost 2,300,000 square miles and is larger than the rest of South America combined. Brazil’s land mostly contains untapped riches in minerals, wood, power, and agricultural products. In 1958 it had a population of about seventy-one million compared to Argentina, the next most populated country in South America, with twenty million. It had an annual population growth rate of 3.1 percent, which was higher than the rest of the region, foretelling even greater population growth.[4]

Then there is the difference in history. The plantation economy of Brazil resulted in a European and African population with only limited Indian influence. Its neighbors, on the other hand, were pure European, Native American, or mestizos—a mixture of Native American and European backgrounds. These differences are reflected in the way Brazilians act. Brazilians seem to be more carefree in the way they live. One is not sure they are happier, but they appear to be. They do not seem to suffer in difficult times as much as the rest of the region. Dancing and singing are important elements of their lives.

Maybe part of the reason for Brazil’s different outlook on life started with the accidental discovery of the region in 1500. Pedro Cabral, official navigator of the Portuguese court, was on his way to Africa through the Cape of Good Hope when he swung farther west than planned and encountered the northeast coast of Brazil, claimed it for Portugal, and was soon on his way to Africa. At the time spices from the East and gold from Africa were what the Portuguese were after, and Brazil offered neither and was ignored. When it was discovered that the soil and tropical climate of northeast Brazil was ideal for the growth of sugar cane, this became a lucrative substitute for gold for the Portuguese.[5]

The production of sugar brought about a cultural change that ensured that Brazil would be different. Raising sugar cane required significant labor, and since there were few natives to be captured and made to work the fields, slaves were brought across the Atlantic Ocean from Africa. The traditional Brazilian became a mixture of the blood and culture of three different and distinct populations: the Portuguese landowner, a limited influence from the native Brazilians, and the African slave. Though the history of the latter two is tragic, their presence and culture enriched the European Catholic Portuguese.

Brazil also had a different political history. The Portuguese governed Brazil with less political control than the Spanish did in the rest of the continent. As a result, a certain degree of freedom and independence developed among the elites born in Brazil. They did not feel the repression as much as their contemporaries had in the Spanish colonies. Their feelings toward Portugal were not intense or antagonistic. So when warfare in Europe in 1807 encouraged the king of Portugal to escape to his colony to the southwest, he was accepted with open arms. When independence from Portugal came in 1822, it came not as a result of war but a relatively easy transfer of power from the king of Portugal to his son Pedro I, who led the movement to leave the Portuguese empire. The empire created in Brazil continued to the end of the century before a republic was declared in 1889 and the monarch, Pedro II, was invited to leave. All this happened with little conflict, again in contrast to the civil wars that Brazil’s neighbors experienced.

This tradition of nonviolence continues to the present. Occasionally governments have been overturned by the military but without significant bloodshed. Probably the most important political figure in Brazil was Getúlio Vargas, who took over the presidency in 1930 and, with the exception of five years, was president until 1954. During his rule of both dictatorship and democracy, Brazil began the process of serious modernization. It went from a rural country with a coffee-based economy to a country beginning to industrialize and diversify. It was an economy that by the end of the twentieth century would be one of the strongest in the world.

This was the country that welcomed the Bangerters, a country with a history of diversity and change. In 1958 Brazil was on the verge of major change both economically and politically. The Church there would pass through transformations parallelling what was happening in the country.

The Church Comes to Brazil

The Church’s entrance into Brazil did not follow an easy or logical path. And it took some time in arriving. When Elder Parley P. Pratt returned home from his mission to Chile in 1852, he knew of Brazil’s monarchy and the dominating political presence of the Catholic Church. Pratt knew Brazil would not allow proselyting. Church leaders’ concerns about Brazil were increased in 1876, when the emperor of Brazil, Dom Pedro II, made a trip to Utah because he wanted to see “the harems of Brigham Young.” The emperor’s negative reaction to Utah combined with his outward support of the Catholic Church in Salt Lake further strengthened Church leaders’ perceptions that Brazil was not yet ready for missionaries.[6] When Elder Andrew Jenson, the Church historian, passed through Brazil in 1923, he was not impressed, and the first missionaries to South America went to Argentina and not Brazil.[7]

When Elders Ballard and Pratt left Argentina in 1926, they were replaced by a young German convert by the name of Reinhold Stoof as president of the South American Mission. Even though Rey L. Pratt’s letters to Salt Lake City stressed that missionary work should focus primarily on Spanish speakers, and even though there were several well-qualified Spanish-speaking men, Stoof, who did not speak Spanish, was called to head the mission. Stoof may not have been the logical person for Argentina, but he was important for Brazil. One of his early missionaries recalled that “Brother Stoof felt deep in his heart that his call was to work with the German-speaking people of South America, and that was the thinking when the mission was opened.”[8]

Stoof’s hope for Argentina was modified when he realized that the German population was scattered throughout the country. He quickly recognized that if the Church was to remain in Argentina, the missionaries would have to work primarily among Spanish speakers. Stoof concluded that the situation he had hoped to find in Argentina existed in southern Brazil. In Brazil’s four southern states, large numbers of German immigrants had settled in colonies and small cities, preserving the language and traditions of their homeland. Among the immigrants were Latter-day Saints who had sent requests for religious materials from the Church in Germany and Salt Lake City and suggested that missionaries be sent to Brazil. The letters to Germany were forwarded to President Stoof in Buenos Aires. In 1928 missionaries went to the German town of Joinville in southern Brazil and a small branch was established.[9]

The Church he envisioned for Brazil would be significantly different than the Church in Argentina. It was to be a German-speaking mission at first with limited interaction with the rest of the population. Missionaries went to the larger cities of São Paulo, Porto Alegre, and Curitiba, but none learned Portuguese. The strength of the mission was in Joinville and the surrounding German communities. One important small congregation was established in Rio Prêto (later called Ipomeia), where a German convert, Auguste Lippett, had moved. Her influence resulted in a small but active branch of the Church in this small place.[10]

Stoof was in South America until 1935, and upon his release the Brazil Mission was formed. The first president was Rulon S. Howells, a Salt Lake City attorney and former missionary from the Swiss-German Mission. He continued to focus missionary activities toward German speakers but realized that if the Church was going to prosper in Brazil it would have to expand beyond the small German-speaking population. Because of this concern, he had the Book of Mormon translated into Portuguese.[11]

The switch to Portuguese speaking occurred after Howells returned home and J. Alden Bowers became president between 1938 and 1942. It happened at the injunction of the Brazilian government, which began a program of forced integration of the large immigrant population into the mainstream of Brazilian society. One aspect of that program was the banning of non-Portuguese languages in public gatherings. This change occurred in 1938, just before World War II, which left little time for the Church to grow outside the already established branches.

The years after the change in the language difficult and frustrating for the Church. President Bowers struggled to maintain the Church among the German converts while at the same time opening missionary work in other parts of the country. That period was followed by World War II, when the missionaries were taken out of Brazil under the presidency of William Seegmiller. The return of the missionaries under the presidency of Harold Rex was an equally challenging period. During these years the focus of the mission was on rebuilding and reopening areas of the mission that had been closed because of the war. Rulon S. Howells, who had presided over the mission between 1935 and 1938, was asked to return in 1949 for a second mission.

Howells sent missionaries into new areas of the country, but he was more concerned with the members who were already in the Church. His missionaries while spending time proselyting also allotted considerable time to work on responsibilities related to the branches. He believed the Brazilian members deserved the same programs that existed in the United States, so he instituted a program of welfare that taught the members self-sufficiency and unity. Though the growth of the Church was not significant, members fondly remembered Howell’s concern for their welfare.

Howell’s successor was Asael T. Sorensen. He encouraged growth and development of the branches through increased missionary involvement in proselyting. The result was that much of Howell’s welfare program was eliminated because the administration of the program took too much of the missionaries’ time. Sorenson emphasized proselyting techniques and teaching methods. He also believed the key to Church recognition was chapel construction. So during the visit of President David O. McKay in 1954, he was given permission to begin purchasing land where chapels could be built. The initial five years President Sorensen was in Brazil was important in the evolution of the Church in Brazil.

Grant Bangerter

Coming to Brazil at this time in the life of the Bangerter family was not easy. His construction business was doing well, and Grant felt established. But he explained to President Stephen L. Richards during his call that they “had always been at the disposal of the Church and felt even more so at this time.”[12] They were scheduled to go to Brazil by boat but because Geri was in her ninth month of pregnancy they went by plane, one of the first flights for mission presidents. They were met by President Sorensen and his wife and children. The Bangerters settled into the upper three rooms of the mission home until the Sorensens left; after they left, the Bangerters began to get acclimatized. Sorensen and his family stayed an extra two weeks so the two presidents could tour the mission together.[13]

What President Bangerter found in the mission pleased him. Though the number of members was not particularly large and the units of the Church weak, the missionaries were working hard. He recognized a significant difference in missionary approach from his time as a missionary. The purpose of missionary work was the gathering of the elect. Because of the early success of missionaries in northern Europe, the concept of just whom those elect were had greatly affected how missionary work was done. The early leaders of the Church taught that those who accepted the gospel where part of a chosen people who were to be gathered back into the Church. This concept of the “chosen” had its origin in Old Testament history of the growth, scattering, and eventual gathering of the twelve tribes of Israel. Those beliefs concluded that within the human race, one special group of people had been chosen to receive the special blessings because of faithfulness and worthiness in the pre-earth life. They came to the earth as descendants of the prophet Abraham through the lineage of Jacob’s twelve sons and, though eventually scattered throughout the world, still carried the blessings and privileges of that special lineage. The Prophet Joseph Smith believed that the righteous descendants of the twelve tribes of Israel would eventually be reunited by accepting the restored gospel of Jesus Christ and gathering to Zion.[14]

These beliefs greatly affected missionary work in Brazil during the early years. During Bangerter’s first mission, who would be taught was an issue of great importance. “We thought that the blood of Israel meant blond, European people, and that we wouldn’t expect too much success among Latin peoples because they probably didn’t have the proper lineage. So under these conditions we weren’t too serious about the great overall purpose of missionary work in the Church. And according to our vision, so was our success. We had very little of either.”[15]

There are few in Brazil who fit that profile. Brazil’s population originally was a mixture of Portuguese and African, and then in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a significant immigration from Italy and Spain entered the mix. There was even a large Japanese immigration primarily to the state of São Paulo. Interracial marriage was common. So the types of people the missionaries were looking for were not in the majority. And with some racial restriction in the Church, the numbers who fit the profile were even smaller.

But over the years, these ideas of the chosen being from northern Europe had begun to change and the missionaries under President Sorensen were not preselecting based on ancestral origin. Bangerter was pleased as he visited the different branches in Brazil. President Sorensen had instilled in the missionaries a desire to work and baptize. But President Bangerter, like most new mission presidents, began to notice certain things he would do differently, not because what was happening was wrong but because it didn’t fit Bangerter’s perception of the best way to do missionary work. He started to instigate a few minor adjustments that would better fit his ideas and approaches.

The first thing he observed was that missionaries didn’t spend enough time doing proselyting. The missionaries were working, but owing to a lack of local leaders, the missionaries were heavily involved in the administration of the local congregations. Many of the branches did not have a local member as branch president, and consequently the missionary had to be the leader. Missionaries were also teaching Sunday School, keeping unit records, and participating in all branch activities. As a result, the number of hours actually proselyting was lower than Bangerter expected or wanted.[16] He also felt the missionaries needed a better understanding of what their calling as a missionary was. They needed to believe that their primary and most important responsibility was that of proselyting and teaching nonmembers, even though this was not easy. Often missionaries allowed nonproselyting activities to dominate their time. Going door to door, receiving rejection after rejection, was difficult. Bangerter stated, “The missionaries had innumerable preoccupations which gave them excuses to stay away from proselyting.” He felt that with a clear understanding of their purpose they would begin to have the type of experiences that would excite them about doing proselyting missionary work.

He felt a need for additional training. He saw discouragement because of the rejections they were receiving. The missionaries saw those rejections as apathy on the part of the Brazilians toward their message. This often caused missionaries to become depressed and discouraged. Missionaries needed to be trained to deal with rejection. After one meeting with his missionaries, he realized what was happening. “In the evening, after all the meetings, we interviewed all the missionaries and concluded that they were not too well organized for a full program of proselyting work . . . and asked the supervising elders who were in the district to help them get organized.”[17] President Bangerter felt the missionaries needed more personal contact with the mission president and mission leaders. They needed to become excited about something new. “This appeared to have slowed down the enthusiasm of many capable elders, and they seemed to be in the need of some new approach to arouse more interest.”[18]

The question was what new approach would excite the missionaries. At the time there was not a specific Church program on how to do missionary work. Bangerter himself had received only limited instructions from the General Authorities on how missionaries should function. Mission presidents experienced only one day of training in Salt Lake City before leaving for the field, and that training was primarily on how to administer a mission. He had been told that he should follow the Spirit in directing the mission.

His first few weeks were both exhilarating and frustrating—exhilarating because of the interaction with missionaries and members. He visited the entire mission with President Sorensen and then alone began a series of visits back to the branches where he met again with the missionaries and held member conferences. It was frustrating because he had to learn fast how to be a missionary president. He became particularly frustrated with his administrative duties: “It was a continual fight to gain an understanding of the administration and keep up on the outlined programs.” Then there were challenges common to a normal family, “problems with water plumbing and electricity,” as well as sickness among the missionaries. The pressures combined to create concern over not being able to spend enough time with his family. “I have been unable to do a good work with my children, especially Cory (thirteen-year-old son) who needs so my guidance. He spends much time with the missionaries, and he’s happy but I need to be with him more.” He soon learned that the pressures of being mission president took so much time that it became essential that he take special time to be with his family. His wife, Geri, was important in helping him maintain a balance between the work and family.[19]

Missionary Health

One serious challenge that had plagued the mission for many years was poor health. Young missionaries were often not careful with hygiene. One result was a high incidence of infectious hepatitis among the missionaries in all of South America. The disease often spread from missionary to missionary because of contact they had with each other in meetings. The disease debilitated missionaries so they were unable to work for about two months because of physical weakness. As soon as the disease was diagnosed, the missionary was quarantined in the mission home for the entire recovery period. The first case of hepatitis occurred shortly after the Bangerters arrived. Sister Bangerter, a nurse by profession, didn’t know much about the disease and decided to study it to determine if anything could be done. The infected missionary, Sister Audrey Olpin, was also a nurse and was given an assignment to find information on the disease. Sister Bangerter stated, “Now, Sister Olpin, I brought all my nursing books with me. Now is a good time for you to write up a research paper on hepatitis while you’re convalescing. I don’t know what’s in these books. You just search everything you can find.”[20]

What Sister Olpin discovered was that hepatitis attacked the liver and that the damaged parts could not be restored. Analyzing her research, Sister Bangerter determined that the most important response was to decrease the amount of damage to the liver during the initial period of the disease. The amount of damage was diminished if the liver received high levels of sugar. During the initial stages of the disease, however, the person was so ill and sensitive that food intake was problematic and vomiting likely. Sister Bangerter’s solution was for the sick missionary to immediately eliminate fats from their diet and take sugar intravenously. “From now on, standard policy is going to be that the very minute that an elder gets hepatitis he is going to the hospital and they are going to put him on glucose immediately and let it drip for a couple of days until he gets over the vomiting.” The treatment significantly reduced the longterm damage to the liver and subsequently the recovery period.

However, this change in treatment did not result in significantly fewer cases, just improved recovery. The problem became so serious that at one time during their first year in Brazil, sixteen missionaries had the disease, which represented almost 10 percent of the missionary force. Geri began to panic and feared that they were about to have an epidemic. She thought to herself, “Now, here you are a nurse and you are living in a modern day and age when they should be able to do something about this. Why don’t you do it?” She did further research on the disease and in the process contacted several doctors in São Paulo for help and advice. What she discovered was that an injection of gamma globulin serum caused a temporary immunity for hepatitis for about three months. She believed that if the missionaries received an injection every six months, they would eliminate most of the cases of hepatitis.

With the assistance of local doctors, syringes and medication were purchased and gamma globulin shots given to the missionaries at the regular district conferences, mostly by Sister Bangerter. Though not a pleasant experience because the shots were painful, the positive impact was significant. After they began to administer the shots, only two missionaries contracted infectious hepatitis during the last three years of their mission.

Sister Bangerter then began to look at less serious issues of health and diagnose general causes for health problems of the missionaries. She wrote a health manual that was distributed to the missionaries describing how to avoid common health problems. She gave regular talks to the missionaries and counseled them on ways to avoid difficulties. The number of hours lost to illness in the Brazilian Mission dropped significantly.[21]

After Geri discovered how to respond to hepatitis, she talked about her program at one of the regular conferences held with the other mission presidents. All the missions were having similar health problems, particularly hepatitis. President Tuttle instituted a similar program of gamma globulin shots for all the missionaries throughout South America under the direction of Sister Bangerter. She would purchase as much gamma globulin serum as possible in Brazil, bring the medication to the conferences, and distribute the serum to the mission presidents. The net result was a significant decrease in illness among the missionaries. Her hepatitis program was so significant that it was adopted in several missions worldwide.

Proselyting

A great help in developing a proselyting program for the missionaries occurred in March of 1959 with the visit of Elder Spencer W. Kimball of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. He was on a tour of the missions of South America with his wife, Camilla. They arrived in Brazil on March 7, and in the first meeting held in the southern city of Porto Alegre his message was clear. President Bangerter wrote, “Elder Kimball’s instructions consisted of missionaries keeping their time sacred for proselyting and proper conduct in preparation for life.” A week later in São Paulo, he suggested that the missionaries needed to be relieved of their responsibilities in branch and district administration and be replaced by local members. The emphasis of the mission president should be on priesthood development. With this happening, the missionary would be free to proselyte. The next day while meeting with the mission presidents from Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil, Elder Kimball’s message was the same. They needed to examine “the organization of branches and districts and to study how we can get all our missionaries proselyting full time.” Programs of leadership development “aimed at placing members in full charge and activity and to prepare for future stakes and wards.”[22]

But how to do what Elder Kimball suggested? Bangerter decided to concentrate first on helping the missionaries change their attitudes toward proselyting. Armed with Elder Kimball’s instructions, President Bangerter again visited with missionaries and emphasized proselyting. He was excited, and it began to show in his interaction with the missionaries. He suggested the first week of April to be “the best week in the history of the mission as far as proselyting goes.” On April 20, 1959, in a meeting with missionaries in Rio de Janeiro, he talked about Elder Kimball’s message: “Keep those hours sacred. The message appeared to be well received.” For the first week in June, the mission average for missionary work was fifty-eight hours proselyting and twenty-two cottage meetings. “It was a grand week of dedication, and the letters from the missionaries were full of happiness for the experiences they received.”[23]

The results were impressive in terms of proselyting hours of the missionaries, but administrative changes were needed. In the first place, administrating a mission as large as Brazil was almost impossible and exhausting. Just getting to all of the areas was a struggle. Bangerter had stressed this to Elder Kimball, and a promise of relief came on July 15 when he received notice from Elder Kimball and President Moyle that the mission would be divided. The lower three states—Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul—would be separated to form the Brazil South Mission. President Bangerter would continue to preside over the Brazil Mission, which included the rest of the country. In terms of administration, the split would be a blessing, but in terms of emotion, they were sad because they would not have contact with members in the south, whom they had learned to love.[24]

Asael T. Sorensen and the Brazil South Mission

The split took place in September 1959 with the visit of Elder Harold B. Lee. He made a surprise announcement that President Asael T. Sorensen would return as president of the Brazil South Mission. He had already spent five years as president of the Brazil Mission and would spend an additional two in the south. President Sorensen and his wife, Lorraine, were understandably surprised. President Sorensen was born in Burton just outside of Rexburg, Idaho. He attended the University of Idaho before accepting a mission call to Brazil in 1940 where he worked with a large number of talented missionaries who, like himself, would dedicate much of their lives to the Church. After serving in the military during World War II, marrying Lorraine Mason, and moving to California to work in sales, Sorensen returned to Brazil in 1953 as mission president. Five years was a long time to serve with the challenges of presiding over the expansion of the Church that occurred. Because he had little contact with his mission presidents during his own mission, he focused his attention on the missionaries while serving as president.[25]

After returning home in January 1959 and settling into their new home in California, Sorensen was invited to have lunch with President David O. McKay: “The President put his arm around me and said that the Lord wanted me to go back to Brazil a second time, and we were to get ready in a very short time.” The time was very short—they had a week to sell their new home, pack, and get to Salt Lake City. They joined Elder Harold B. Lee of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and his wife, Fern, on the passage liner Brazil. The Lees and the Sorensens arrived in Rio de Janeiro on September 7, where they held meetings with the members. President and Sister Sorensen then left Elder Lee to tour the southern mission with President Bangerter and flew to Curitiba, Paraná, where the mission home would be located. Sorensen’s recent experience with a quick move was helpful, and they were able to purchase a mission home and set up the mission office in the ten days before Elder Lee arrived in Curitiba to tour the southern part of Brazil.[26]

The Sorensens knew the southern mission would be a challenge because the Church had experienced significant upheaval and challenges during the thirty years it had been in southern Brazil. The new mission consisted mainly of small congregations still run by American missionaries. There were 1,144 members and, more important, only forty-four Melchizedek Priesthood holders, from which local leadership came. There were eleven branches, and the majority of the members lived in the two large cities of the region, Porto Alegre, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, and Curitiba. President Sorensen knew what had to happen—they needed to quickly organize and strengthen the mission so the missionaries could begin to attract new converts. The Sorensens were not sure how much time they would spend in Brazil, but they were ready to meet the challenge.[27]

The Challenges of Growth

During his visit Elder Lee regularly talked of high expectations for the growth of the Church in Brazil. He also suggested a need for the General Authorities to increase their understanding of Brazil.[28] Both mission presidents began to make adjustments in proselyting techniques. Bangerter stressed to the missionaries that Mormonism in Brazil was moving into a different stage of its history, a “new era.” This “new era” implied several things, but to the missionaries it meant that numerical growth was to be their number one priority. Therefore, their most important responsibility was to proselyte, convert, and baptize. An excerpt from a missionary conference report from the interior of São Paulo shows a change in attitude: “The New Era which started in March 1960 is now in full swing, and the power of it can certainly be felt here in the Bauru District. The conference helped all those who attended gain a deeper appreciation of what the New Era means in the lives of the various branches. Nothing can be seen in the future of our district but growth, progress, and success.”[29]

The changes that occurred were a result of the mission president’s increased attention to the missionaries. Bangerter began visiting with them more often, averaging about twenty trips a month away from the mission headquarters in São Paulo. During these visits, missionaries were asked to set goals for numbers of baptisms, and mission leaders made sure these goals were met. They were encouraged to determine early in the teaching process the real interest of investigators and not waste time teaching those who would not follow through with baptism. Missionaries were also encouraged to increase their effectiveness by bringing several families or individuals together at one time to hear the missionary discussions. Not only did this tend to increase effectiveness, but the group environment generally increased positive peer pressure.[30]

This approach was a significant change from what had been occurring in Brazil. For most of the history of the Church, the process of conversion took a long time. Members were taught a long series of lessons in which all the basic gospel tenets were presented. Investigators were expected to become involved in Church activities and participate in meetings for a long time. Often Church teaching and administrative positions were held by investigators who were still studying the gospel. There was a reluctance on the part of some missionaries to push for baptism. Often the investigator asked for baptism and not the other way around. The idea was that people should be baptized only after they had learned all about the Church and showed by continued and sustained activity that they were committed to the Church. Notice this quote by Flavia Erbolato, an early convert from Campinas, São Paulo. “In that time there was not an obligatory plan for missionary work. There was not the push for immediate baptism. . . . So there developed a sentimental connection with the missionaries.”[31]

President Bangerter decided to change the approach. Historically, waiting for the investigator to request baptism was not the way Christ had worked when He taught during His ministry, nor was it the way the early nineteenth-century missionaries had worked in the United States and Europe. Their method was based on the investigators’ receiving a testimony from the Spirit. When that occurred, they were baptized. Bangerter did not believe that the methodology of the missionaries, based on an intellectual or logical approach when a testimony came by months of teaching, was correct. Their approach needed to be modified to emphasize the spiritual. Elders were encouraged to spiritually prepare themselves to teach the gospel so they could carry over the Spirit to those contacted. Once those being taught felt the Spirit, they were baptized, often within a week after the initial contact. The complete intellectual explanation came after joining the Church.[32]

As it was explained in the mission newsletter, the method was simple: “We must pattern our actions and thoughts after the manner of our Savior: and to do this we must be directed at all times by His Spirit. Be Courageous! Challenge your contacts to hear the gospel message. Challenge them to be baptized. Do it, the Lord has promised His Spirit. Does your contact feel in his heart the truth of your message?—Baptize him: don’t wait.”[33]

The message was clear: it was time for change. On May 6, 1960, Bangerter recorded in his diary, “I’ve never felt so sure of the Spirit of the Lord as we move to new growth through the intense and faithful dedication.” On May 22 he noted in his diary the weather and also the number of baptisms: “It was a cold day, but once again there was a fairly large group at the mission home to receive baptism. The results of the new era are wonderful to our surprise each week.” Talking about the changes seen in the missionaries of the interior of São Paulo, he stated, “The new era has become a reality in this district also, and there is scarcely a flaw in the missionaries either in their spirit or capacity. . . . The spirit of this group is one of the best imaginable. The feeling is there that we will more than double the rate of progress and that the Church is certainly moving with greater power.”[34]

The changes also brought challenges with them. Bangerter believed that the adversary was working against what he was trying to do. There were the normal adversarial activities against the Church, primarily coming from other churches. Political problems affected the Church, including the resignation of President Jânio Quadros in 1960 and the tension created with the presidency of João Goulart. But the adversary was also more directed toward Bangerter and the missionaries. There were a series of problems with missionaries, including two excommunications for moral indiscretions, both in the same week. Bangerter felt that all the missionaries appeared to be under greater temptation because of the success that was occurring. He described what he felt was a cloud of darkness in the country: “I felt often that much of Brazil in our early days was under a cloud of darkness. I could feel the forces of darkness move across the land. It was a spiritual feeling that was evident with me. Often when I went into new areas I could feel that these clouds of darkness were obstructing the entrance of eternal light. . . . Over the years that we were there, when we introduced the Church and the gospel, I could feel the dispersion of those dark clouds and the feeling that the rays of light were coming forth with great power into the land of Brazil. I was aware of various waves of powerful effort on the part of the adversary to destroy us. They would come in different forms. I never knew how to anticipate them, but I learned they would come.”[35]

Those same beliefs were held by Elder Tuttle and some of the other mission presidents in South America. In a letter to Elder Harold B. Lee, Elder Tuttle expressed his feelings. “At times it seems that the pale of darkness and evil hangs heavy over this land and people, and threatens to smother the light of truth so recently kindled in this dark land. We are trying to go forward on a sound and reasonable basis, without exciting either the investigators or the missionaries, and yet move with the feeling of urgency that attaches to all of the Lord’s work.”[36]

That feeling was so great that in the first meeting of mission presidents, held in December 1961 in Montevideo, Elder Tuttle offered a special prayer rebuking that power.[37]

In June 1961 the Bangerters returned to Salt Lake City to attend the worldwide mission presidents’ conference. Wanting the entire Church to enter into a new era of missionary work, the First Presidency invited all the mission presidents to come to Salt Lake City for a special weeklong seminar in July 1961. Talks by Church leaders encouraged a renewed emphasis on missionary work, including President McKay’s well-known challenge, “every member a missionary.” The seminar was an important stage in the process of centralizing missionary work Churchwide and a subsequent increase of pressure on mission presidents to produce converts. It was an important landmark in the history of missionary work in the Church in the twentieth century.[38] Bangerter made two presentations at the seminar: one on his program of integration and the other on the use of street meetings in proselyting. He was pleased with the reactions to both of his presentations.

The major innovation presented in the meetings was the introduction of A Uniform System for Teaching Investigators, with instructions that all missionaries were to use this series of six discussions in teaching all investigators. Missionaries were to memorize the discussions and present them as they are written. The plan was close to the one President Asael Sorensen had earlier introduced in the mission. Bangerter felt the new lesson plans were “nothing greatly radical from our own program, but it has great possibilities, especially applied to teaching groups.”[39]

Bangerter returned to Brazil enthused and satisfied, having heard little that was not already being done in Brazil. He reported to the missionaries that “we will not have to make radical departures from our present procedure. We do expect to unite with the whole Church, however, in following the direction of the General Authorities in the missionary work.”[40] He did, however, have some frustration with the way things were presented: “I felt they were spending much time on the mechanics but not much was said about the Spirit which brings conversions.” He incorporated the new system the way he thought was best: “Need for simplicity. Impossibility of digesting all that we hear in spite of its great worth. Each mission president must make his own interpretation to his missionaries. It is far more a process of faith and testimony than knowledge of plans and systems.”[41]

President Finn and Sarah Paulsen

The Brazil South Mission received a new mission president after the worldwide mission conference. Finn Paulsen, a missionary colleague of both Presidents Bangerter and Sorensen, returned to Brazil to replace the Sorensens. Under President Sorensen’s leadership the region had experienced significant growth. The number of missionaries increased from the thirty-nine at the organization of the mission to over 140 when the Paulsens arrived. The number of members was over three thousand, and there were over forty congregations. The Paulsens were pleased at the growth that had occurred in the mission over the past two years.

Paulsen family.

Paulsen family.

During their first meeting with Elder Tuttle, they were challenged to have even greater growth and expansion. Elder Tuttle, who had also recently come to South America, realized the Sorensens would soon be released and decided to wait to work with the new president.[42] Elder Tuttle challenged the Paulsens to significantly increase the number of baptisms. This was not easy partially because of the geography of southern Brazil. There were many large cities in northern mission but not in the south. Curitiba and Porto Alegre were the only major population centers, and the rest of the region had smaller cities of between twenty thousand and one hundred thousand where missionaries could be sent. President Bangerter, on the other hand, seldom sent missionaries into cities with populations under one hundred thousand.[43]

President Paulsen soon began to focus on the two larger cities as the places where the Church would grow and expand the fastest. Curitiba, the capital of the state of Paraná, showed the most promise of missionary success. In March 1958 the one Curitiba branch was divided, and a year and a half later the Curitiba district was organized. President Paulsen was pleased with the leadership he found and began to focus on training with the expectation that Curitiba was where the first stake in the mission would be organized. He also began the construction of chapels: two chapels, in Londrina and Curitiba, were dedicated on January 12, 1963. One other chapel was dedicated, and five additional buildings began construction under Paulsen’s leadership. President and Sister Paulsen dedicated themselves to the principles Elder Tuttle espoused.[44]

Expansion North

With the division in the Brazil Mission and an increasing number of missionaries being sent to his mission, Bangerter began to look for places where the Church could expand. The first region was the center west. On April 27, 1960, he flew to the cities of Goiânia and Brasília. Goiânia was an important city in the western part of the country, and Brasília was the recently inaugurated national capital. Missionaries were soon sent to these two cities and started small branches. Then he began to look north beyond Rio de Janeiro where there were no missionaries. Mission presidents had always been careful to send missionaries only into areas with a large population of European immigrants and had not gone into the large cities of the northeast because of the distance and racial makeup of the population.

The cultural and racial differences between the immigrant cities of the south and the traditional cities of the northeast were significant. During most of the colonial period, the strongest area of the country economically was the coastal region of the northeast. This area was little affected by the European immigration of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that populated southern Brazil. Consequently, the people of the northeast more than any other region were racially mixed.[45]

President Bangerter first suggested the possibility of introducing missionaries into the northeast with President Henry D. Moyle of the First Presidency during his Brazilian tour in 1960. Bangerter informed Moyle that he had recently visited a number of the larger cities and felt that in at least three or four there was potential for success. Moyle suggested that missionaries be sent into one city for a short time as an “isolated experiment.”[46]

A few months later on April 2, 1960, missionaries arrived in Recife, capital of the state of Pernambuco, the largest city in the northeast. They experienced minimal success at first for a variety of reasons, including strong anti-American feelings. An almost complete lack of knowledge about the Church by most of the population added to the challenge. Their success improved when the missionaries taught and baptized the family of Milton Soares Jr. His devotion to the Church was so strong that within a few months they were able to organize a small but committed group. On June 2, 1960, Bangerter attended the branch meeting in Recife and was impressed. The missionaries had baptized twelve people in two months and were teaching several people: “They were doing very well in the city, which is huge, working an average of 70 hours per week.” At the sacrament meeting that night there were more than thirty in attendance. “There was a feeling of great strength and promise for stability in the future due to such a fine and capable group of leaders.”[47] Milton Soares was set apart as branch president on October 27, 1961. The success in Recife encouraged Bangerter to open one more area in the northeast, the neighboring city of João Pessoa.[48]

Mission Challenges

In 1962 missionary work in Brazil took an interesting twist, which significantly increased the number of convert baptisms but at the same time caused administrative problems. In the recently opened interior city of Franca in the state of São Paulo, two missionaries began having an unusually high number of baptisms. They took the concept of spiritual confirmation very seriously and began working with their investigators to help them have an experience of the Spirit. Once this happened, the investigator was immediately baptized, with the presentation of lessons occurring afterward. But in Franca the Church was so small and the organization of the Church so new that a program of integrating the members into the Church was weak, and converts did not stay. The new members did not have a strong commitment to the Church. The excitement of the missionaries in convert baptism percentages was accompanied by an almost equal percentage of inactivity, resulting in Franca’s ultimately being closed and the missionaries being taken out because attendance at meetings was so low.[49]

This same concern was found in other parts of the mission. The speed with which investigators were baptized was paralleled by a drop in the percentage of new converts remaining active in the Church. Local leaders became so concerned with the number of inactive converts entering the Church and the negative effect it was having on the organizations. They held meetings with the missionaries to discuss the issue: “The presidency of the Jardim Botânico Branch held a meeting with the missionaries of the branch in which they discussed the converts of the last six months. They found that of the converts of the last six months, very few had remained active and felt, therefore, that some steps needed to be taken to help the people become strong and integrated in the Church.”[50]

Bangerter took the steps he felt were necessary to ensure these members stayed active. In November 1960 in a district meeting they discussed integration. The program he developed was similar to one Bangerter had directed to prepare older Aaronic Priesthood holders to come back into the Church when he was a stake president in Utah.[51] Classes were given to the new converts that included information about the Church that had in the past been given before the person joined the Church. A series of twelve lessons taught the new members the basics of the Church beyond what they had learned as investigators. Missionary visits to their homes slowly decreased as the new members attended weekly meetings. They were introduced to members of the branch during the process. It was important that the person be integrated into the branch as soon as possible so that when the missionary stopped visiting they would have a relationship to the local members and not just the missionaries, as was happening before. By the time they finished the course of study, they had a position in the Church and felt comfortable with new friends they had made.[52]

Another challenge was that some of the longterm members resisted the entire proselyting program. Part of the problem was that local leaders had never experienced this type of growth before, and it challenged them. Some were resistant in particular because of the incident of inactivity. President Bangerter responded, “We know that when we have tried to move fast in our baptisms and bring many people into the Church, there is a great danger that we are going to lose them, and we have lost a lot, but we find out that we can go out and sweep them up again when we have a place to put them.”[53] He felt that with this type of program the members would be integrated into the Church with enough knowledge and understanding that they would remain active in the Church.

Member Organizations

President Bangerter loved missionary work and labored hard with the member side of his responsibility. He realized that time and effort was required to strengthen the local units in preparation for the organization of stakes. One issue was getting the local members to administer the ecclesiastical units so the missionaries could have increased time to do missionary work and increase the number of members. Bangerter’s own experience as a missionary pushed him in a direction of change because as a missionary he held administrative position over the branches: “There I felt according to the system of that time, that I was promoted away from doing actual missionary work. I was now an administrator and a leader. And I took pride in doing that which was not related to basic missionary work. For that reason I felt now that I lost out on the best part of my mission by being assigned to supervisory work.”[54]

That was not what he wanted his missionaries to feel. He wanted them doing missionary work. Historically, most mission presidents wanted branch leadership to be turned over to the Brazilians; however, that desire seldom became reality. Brazilian men were not given the priesthood until long after baptism and generally held minor positions in the branches. For instance, President Asael Sorensen commented during his presidency: “The missionaries felt that they had to be branch presidents and district presidents. . . . So we really didn’t build up a member organization.”[55]

Bangerter made it his personal goal to complete the transition of replacing all American missionaries with local Brazilians in the administration of branches and districts. After the split of the missions, he calculated there were nineteen branches, of which fourteen were presided over by missionaries. That left only five local members serving as branch presidents.[56] He stated in a missionary supervisors meeting, “The day we have the mission under local leadership will be the happiest day in the Brazilian mission. . . . The missionaries are here to proselyte, not to preside.”[57]

The first step was to ordain men to the priesthood. That process had historically happened slowly. To speed up the process, recently baptized men began to receive the Aaronic Priesthood shortly after being baptized. As soon as the required one year of membership was complete, they were ordained elders if found worthy. The consequence was significant. By 1962 there were 224 males who were elders, compared to 32 in 1952.[58]

The transition of moving these new converts into administrative positions took time and was difficult. There was a significant difference between having a testimony and possessing sufficient managerial and personal abilities to administer the branch organization. Men who were active members often failed when asked to work as branch presidents, not because of any lack of desire or commitment but because of a lack of skills.

There was also a problem of training. These new members had little idea of how the Church functioned. President Bangerter often did not have enough time to provide sufficient training before assigning some men as branch presidents. The branches often went through periods of tension and struggles as the changes occurred. Occasionally, a Brazilian branch president would be unable to measure up to the standards expected and had to be released. Problems such as this made the transition to member control difficult. During one week, six branch presidents notified Bangerter they were resigning. Bangerter complained that he was “on rolling waves of opposition that seemed to attack with the hope that they would destroy the Church.”[59]

When the resignations occurred, the missionaries returned to branch leadership until another lay member was considered worthy and capable to serve as branch president. When Bangerter left the mission, the number of branches had increased significantly, and all but three were presided over by local members.[60] Even with the challenges, Bangerter was satisfied with the results.

After the branches were turned over to local control, the goal became to turn the regional organization, the district, over to the Brazilians. When President Bangerter arrived, all the districts were under the leadership of missionaries. Bangerter wholeheartedly implemented a six-point plan developed by Thomas Fyans of the Uruguayan Mission to follow when organizing stakes. This plan became an important guidepost for Bangerter and other mission presidents throughout South America to determine their progress toward achieving the goal of a stake organization.

He moved quickly to put Brazilians into those positions while separating the missionary organization away from the member organization. Bangerter organized two districts, one in São Paulo and a second in Rio de Janeiro. José Lombardi was released as branch president of the Center Branch and made district president of the São Paulo District with Lionel Abarcherli and Hélio da Rocha Camargo as his counselors.[61] The new leaders of the district were not sure what a member district was since it had never been organized in Brazil before. President Camargo commented: “For a while, neither he [President Lombardi] nor us knew what it meant to be a district president. . . . There didn’t appear to be anything for us to do. . . . I remember that for a long time we were lost. . . . We felt it would be better to be returned to the branches where we had something to do.”[62] In a meeting with President Bangerter, Camargo suggested that they be released. Bangerter stated, “I was able to find the true basis of the testimony of these men and then had the opening to show them that the development of the small church depended on them and that now was the time when the Lord was raising up His servants for the establishment of His work in power in South America. Some were to be called to carry the burden, and it had fallen on them. I showed them that the reason there was not an adequate program in the mission was because they were the ones to provide it and strengthen it and for this reason they had been called.”[63]

Bangerter, with the help of the missionaries, began to instruct the district leaders. Little by little, responsibilities that had been the missionaries’ were turned over to the district organization. Problems normally handled by Bangerter or the missionaries were referred to district leaders. The three Brazilians began to travel each Sunday to different branches, holding meetings and conducting interviews. Slowly the new leaders began to understand what was expected of them.[64]

Observing the difficulties these district leaders had in their new positions, Bangerter recognized a need for some sort of systematic leadership training that would better acquaint Brazilians with the procedures and organization of the Church. Because of the limited native participation in the past, there had been no organized attempt to prepare Brazilians to move into administrative positions. On August 6, 1962, Elder Tuttle was in Brazil on a tour of the mission, and he and President Bangerter spent much of the day discussing the process that was occurring: “We investigated the organization of the Church from every aspect possible and attempted to reduce our thoughts to the simple and basic organization which should exist throughout. In this we felt greatly the power of understanding led by the spirit of the gospel and an assurance that we were studying one of the urgent problems of our time in South America as it pertains to the establishment of the Church in this land.” Their conversations continued into the next day, this time while eating several dozen sweet tangerines. By the end of the tour on August 14, Bangerter had his plan worked out.[65]

The leadership training programs, initiated by Bangerter, were designed to familiarize all of the leaders of the branches and districts with the organization of the Church, the responsibilities of each position, and the financial obligations of the members. Although not fully operational when he left, this leadership training program was perhaps the most important accomplishment of his presidency. “During the last year of our leadership, we actively engaged in an organized and outlined plan of leadership training. . . . We were impressed that their level of activity was on a par with many existing stakes of the Church.”[66]

After organizing the member districts, the next step was to replace Americans with Brazilians as counselors in the mission presidency. In 1959, Elder Spencer W. Kimball suggested that Bangerter turn over much of the supervision of member organizations to Brazilian counselors in order to put “members in full charge to prepare for future stakes and ward.” [source?] Bangerter called President Camargo, a counselor in the São Paulo District, to serve in the mission presidency. Bangerter explained, “He is a man of outstanding education and culture, now active in private business. He has unusual gifts of knowledge and understanding in leadership and organization united with complete and humble faith. His abilities as a speaker are to be unsurpassed as far as I know anywhere in the Church.”[67]

Camargo played an important role in the development of the Church during this immediate pre-stake period. Bangerter and his successor, Wayne Beck, gave the responsibility for member organizations to Camargo, which in turn allowed Bangerter more time to work with the missionaries. Camargo was instrumental in instituting many organizational changes and conducted several of the leadership training seminars held throughout the mission.[68] Later he served in numerous positions and was eventually called as the first Brazilian General Authority.[69]

The growth of the Church in the city of São Paulo was measured at the dedication of the Pinheiros chapel in 1962, when two separate sessions had to be held in order to accommodate the 1,500 who attended the meetings. Consequently, a few months before leaving Brazil, Bangerter split the São Paulo District into four small districts. He felt that this would allow for more members to have the experience of leadership. Bangerter’s goal of organizing a stake was realized after he left.

Bangerter was not as successful as he had hoped in making the changes, as can be seen in this comment made upon his leaving Brazil in 1963: “Right now in Brazil we are in the milk stage, not the meat. . . . The day we have the mission under local leadership will be the happiest day in the Brazilian Mission.”[70]

President and Sister Bangerter were released in August 1963. Bangerter had instituted major changes that modified the course of the Church in Brazil. His feelings about the direction of the country had changed from those he had five years earlier. At the time of his release, he wrote: “Today we feel an affinity for Brazil which is of the spirit by which we feel the rays of living light spreading and penetrating this vast nation to replace much of the dark and terrible influence which has dominated the land through barbarity, Catholicism, spiritualism, witchcraft, and other wiles of the devil. . . . This is a land of hope and promise for the Church and for a great people who live here.”[71]

One side note to the history of the Bangerters in Brazil: on January 12, 1963, President Hugh B. Brown of the First Presidency was making a tour of the Brazilian Mission and met with missionaries in São Paulo. Bangerter describes the meeting as “one of the outstanding meetings ever held in a mission field.” In the meeting, under the spirit of prophecy and revelation, President Brown predicted that within the group in attendance there were future General Authorities. This prophecy would come true when in 1975 Bangerter was called to serve as an Assistant to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. In that capacity he returned to Brazil to preside in additional developments related to the country he so loved.[72]

The Church in Brazil had changed significantly. Between 1958 and 1963 the Church grew from just more than 3,000 to 16,437, averaging about 2,700 baptisms per year. The number of Melchizedek Priesthood holders increased from 97 in 1959 to 476 in 1963.[73] Missionaries were spending the majority of their time proselyting. The next step was organizing a stake. That event was left to Bangerter’s successor, Wayne Beck.

Wayne Beck

President and Sister Wayne Beck.

President and Sister Wayne Beck.

Wayne Beck was a man with experience in Brazil. He had served as a missionary between 1938 and 1940, and he, his wife, and two children were asked to return immediately after the war as proselyting missionaries, serving from 1946 to 1948. He was pleased when he was asked to return to Brazil in 1963 as mission president for his third mission. At the time he was working as an administrator at the Church-owned department store, ZCMI, and they promised him a job for when he returned.

After he arrived in Brazil, he spent five days with President Bangerter and was impressed with the growth that had occurred since he was there last in 1948. He concluded that his goal would be to “do more vigorously what Bangerter had done.” He made a few small adjustments in the missionary program but nothing significant. His emphasis became leadership training of the members. As an administrator for ZCMI, Beck came to Brazil with administrative and training skills that were useful in the final push for the organization of a stake. Although no drastic changes were made in the program President Bangerter established, he did move into areas that had not received much attention. Beck reorganized the mission presidency so it included only Brazilian counselors. James Wilson, an American living in São Paulo, was released and Hélio da Rocha Camargo took his place as first counselor with José Lombardi as second counselor. These two men were given more responsibility for training and administering the member units. A second important change instituted by Beck was to place more emphasis on the responsibility of lower-level Church positions. He began by emphasizing the importance of being a good parent and spouse. Thus, during district leadership meetings, President Beck emphasized topics such as home teaching, family unity, and marital relations.[74]

Several events happened in the year and months prior to the organization of the São Paulo Stake that began to build the members’ confidence. One of the most significant was a meeting held with all the leaders of the priesthood and auxiliary organizations of the mission on December 16, 1965. Most of the meeting was a report by Hélio da Rocha Camargo, who had just returned from a one-month training session in Salt Lake City. He had gone to the United States to head a new translation and distribution center being set up in São Paulo. Along with specialized training pertaining to his new job, Camargo spent time visiting and examining the Church on all levels. He and his wife visited Church leaders, went to historical sites, and went to the Salt Lake Temple to receive their endowment and be sealed. His report to the leadership of the Church in Brazil was full of glowing detail.

Though Camargo portrayed an idealistic view of Mormonism in Utah, he saw a connection with the Church in Brazil. He believed that with work and dedication, the Brazilian Church could rise to the same level as in the United States. In this meeting, tears were shed, testimonies borne, and feelings expressed that the goal for which they were striving could someday be achieved.

As the moment for the organization of the stake came closer, the amount of time spent in training increased. A new district in São Paulo was organized, several new branches were opened, and adjustments were made in organizational structure. The weekly training sessions became daily during the last few months as the leaders prepared themselves for the stake organization. The extra training helped the members and leaders better prepare for the upcoming change.

President Beck expressed concerns about some leaders not responding to the training. For example, the branch presidency in Santo André said, “President Beck is afraid our branch and district presidents do not conduct very searching interviews.” He also wrote to the São Paulo district president, Walter Spät, about the need to nurture new converts, keeping them involved in their callings: “Presidents have to keep drawing members like a hen gathers in her chicks.”[75]

Organization of the São Paulo Brazil Stake

In 1965, elder Spencer W. Kimball submitted a request to the Quorum of Twelve Apostles to organize a stake in São Paulo. As the first twentieth-century Apostle to be called from an area outside of Utah (Arizona), Elder Kimball had long struggled against a somewhat recalcitrant attitude among the General Authorities toward the development of the Church outside of the immediate intermountain western United States. As a result, Elder Kimball felt that in order for a Brazilian stake to be approved, everything had to be better than what was normally required for other stake organizations. Consequently, Brazilian districts were functioning the same as stakes in almost every way before the request was submitted for approval. As Elder Kimball told the leadership in São Paulo, “There probably exists more than a 100 stakes in the Church with fewer members than here. . . . Many stakes have much weaker leadership than do you.” António Carlos de Camargo, second counselor in the new stake presidency, expressed the feeling of preparedness in the stake: “I think the time was right to organize the first stake. I think the leadership was right too.”[76]

The additional preparation helped bring approval. When Elder Kimball returned to the United States, he “felt so confident of the strength and vigor of the Church in South America, that he urged in the Council’s Thursday Temple meeting, that São Paulo be organized as a stake. . . . One of the General Authorities expressed strong reservations about the organization of more stakes outside of North America.”[77] After a long discussion on the worldwide growth of the Church, the Council voted and approved Kimball’s recommendation for the organization of only one stake. President Beck said, “We could have organized two, the Brethren thought it would be wise to start out on a little firmer base. They were a little cautious about the leadership.”[78]

In late April 1966, Elder Kimball, accompanied by Elder Franklin D. Richards, Assistant to the Twelve, arrived in São Paulo to begin the organization. Creating any new stake was a time-consuming and tiring experience. Many decisions were made concerning the new positions of leadership after interview with all the worthy males. The São Paulo organization was even more difficult and complicated, owing to the necessity of having a translator present in almost every interview. The process took two long, tiring days.

The man chosen to be stake president was Walter Spät. A German immigrant, Spät had joined the Church in São Paulo as a young man and followed Lombardi in branch and district positions. He had been involved in leadership training for the stake as a member of the mission presidency, though less actively than either Camargo or Lombardi. Besides his moral worthiness and dedication to the Church, Spät impressed the General Authorities with his leadership ability and mannerisms. Spät was a well-organized, effective leader who displayed little outward emotion. He exhibited a sense of authority which the Americans admired. Kimball felt that Spät would be able to maintain firmness and control of the stake during the crucial first years. He was not outgoing and occasionally had difficulties with personal relations, but his other qualities made up for these deficiencies. This statement characterized the way he was perceived: “He is a gruff old guy who sometimes puts you off by his German coldness, however, I think you just have to cut through that, or ignore it, and you will find him a fine man to work with.”[79]

After Elder Kimball returned to the United States, the stake leadership was left to function on its own. Although they continued to rely on President Beck for assistance and advice, they slowly began to move away from their former mentor. When Beck left and was replaced by Lloyd Hicken in July 1966, the transition was complete. Under direct supervision from Salt Lake, the new stake began to work with its new responsibilities and opportunities.

President Beck was pleased. He had been called to come to Brazil to preside over a mission and had accomplished a task that had been desired for many years. The organization of the São Paulo Stake was the final step in a long process that had begun so many years ago. It was also the first step to propel Brazil into the important role it plays today in the Church.

C. Elmo Turner and the Brazil South Mission

The organization of the Church in the south was significantly behind São Paulo. President Finn Paulsen had focused on the city of Curitiba as being the most likely place for the first stake in the Brazil South Mission to occur. During his three years, the mission experienced significant growth, expanding to over 6,900 members in 35 branches. The Paulsens left Brazil in 1964, mostly satisfied with what had occurred in their mission and with some regrets that more was not accomplished.[80]

C. Elmo and Lois Turner.

The Paulsens were replaced by C. Elmo and Lois Turner. President Turner had also served a mission in pre-war Brazil. Afterwards he finished his schooling at Brigham Young University and became a schoolteacher. When President Paulsen arrived, the Tuttles were also new, but the Turners were trained by an Elder Tuttle, who knew what he wanted and how to accomplish those goals. President Turner suggested, “His counsel is wise, I am going to follow it.”[81] Over the next few months, Tuttle emphasized the need for growth the need for growth in his instructions to President Turner but with a caution. Numbers were important, but the quality of converts who had potential for leadership was essential.[82] This concern was also expressed by Elder Kimball in 1965, who after examining the statistics for the mission, expressed pleasure with the numbers but had a concern about a low number of Melchizedek Priesthood holders.[83] Good leaders had come into the Church but did not have much time to mature. President Turner’s hope was that the Curitiba Stake would be organized before he left. His request for the organization of the stake was sent to Elder Kimball just over six months before Turner left. The request was turned down, primarily because of a lack of leadership.[84] It was five more years before a stake was organized in Curitiba and seven before one was organized in Porto Alegre. Although it took longer to bear the fruit than they hoped, Presidents Sorensen, Paulsen, and Turner planted the foundation of the Church in southern Brazil.

Conclusion

The five mission presidents in Brazil from 1960 to 1965 had served first missions around the World War II period. They had faced many challenges and experienced little success during a difficult transition period for the Church in Brazil. Consequently, when they returned as mission presidents, they were eager to ensure that that experience would not be duplicated for future missionaries. During their tenure, the number of members in the Church in Brazil increased from 2,644 to 10,428. All recognized the importance of a strong and vibrant missionary program in the evolution of the Church in Brazil. It would be a blessing for all to return to Brazil in later years to see the fruit of their success as represented in the growth of stakes throughout the country. In 2008 the membership of the Church surpassed one million baptized members and over 210 stakes. It has been a miraculous story, helped along the way by these five mission presidents.[85]

Notes

[1] William Grant Bangerter, oral interview, interviewed by Gordon Irving, 1976–77, transcript, 17–18, James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library, Salt Lake City; and William Grant Bangerter, oral interview, interviewed by Mark L. Grover, 2000, Alpine, Utah; copy in author’s possession.

[2] William Grant Bangerter, Irving interview, 17.

[3] William Grant Bangerter, Irving interview, 25.

[4] Arwin Ludwig, Brazil: A Handbook of Historical Statistics (Boston: G. K. Hall, 1984), 47. By 2005 the population of Brazil was over 186 million.

[5] Boris Fausto, A Concise History of Brazil (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 1–25.

[6] M. Robert Evans, “Emperor and the Saints: Dom Pedro II’s Visit to Utah in 1876” (honors thesis, Brigham Young University, 1993).

[7] Andrew Jenson, Autobiography of Andrew Jenson (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1938), 569; and Andrew Jenson, “South American Mission,” Encyclopedic History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1941), 810.

[8] J. Vernon Sharp, oral interview, interviewed by Gordon Irving, 1972, transcript, 20, James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[9] “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” July 15, 1926–May 31, 1927, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[10] For a description of Augusta’s conversion, see George F. Lippelt, “Quarenta Anos Depois,” A Liahona, April 1968, 58–59.

[11] For a history of the mission during this period, see Mark L. Grover, “Mormonism in Brazil: Religion and Dependency in Latin America” (PhD diss., Indiana University, 1985), 34–68.

[12] William Grant Bangerter, diaries, November 26, 1958, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.