Joseph Smith Goes to Washington, 1839-40

Ronald O. Barney

Ronald O. Barney, “Joseph Smith Goes to Washington,” in Joseph Smith, the Prophet and Seer, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2010), 391–420.

Ronald O. Barney is a historian in the Church History Department, a series and volume editor of The Joseph Smith Papers, and executive producer of the television series The Joseph Smith Papers when this was published.

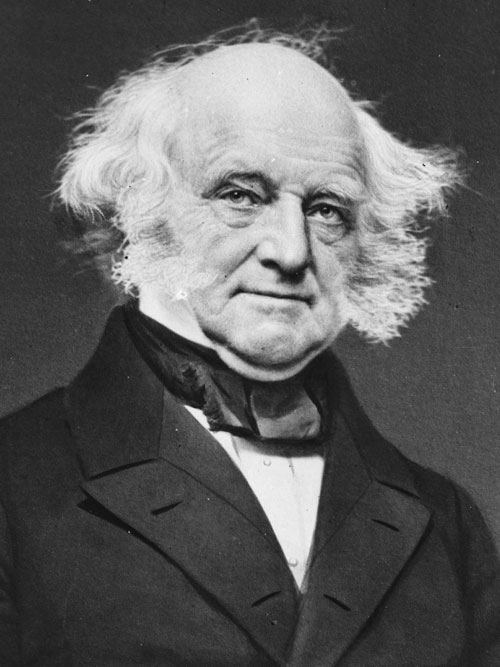

The Prophet Joseph Smith went to Washington to meet with Congress and the president of the United States regarding the Saints' plea for redress and restoration of their rights. After Joseph addressed President Martin Van Buren (pictured here), the president said, "What can I do? I can do nothing for you, -if I do anything, I shall come in contact with the whole State of Missouri." (Library of Congress.)

This chapter focuses on events during one winter of Joseph Smith’s life. I preface it with a disclaimer: this information is provisional, even tentative, and part of my work editing and annotating the fifth volume in the Documents Series of The Joseph Smith Papers. My purpose as documentary editor is, first, to create accurate transcriptions of the records and, second, to prepare annotation providing the context by which the records associated with the Prophet’s life can best be understood. This will be accomplished through published volumes, thirty of which are planned, and an Internet site, josephsmithpapers.org, where material too unwieldy to include in the already substantial books will be made available. While there has been a great deal of publicity regarding the work of the Joseph Smith Papers project, I will briefly introduce the project to provide some background for Joseph Smith’s trip to Washington DC.

As currently planned, there will be six series in the Prophet Joseph Smith’s papers, with several volumes within each series. For example, the first volume released the fall of 2008 is from the Journals Series, which will include three volumes. The History Series will probably include seven or eight books, the Legal Series will include three or four, and the Administrative Records Series will also include several books. The volume that I am working on is the fifth in a projected thirteen-part Document Series, the largest of the series within the Papers. Each book in the Journals Series will include the Prophet’s journals, and each book in the History Series will include the several efforts to produce his history. However, each volume within the Document Series will include a variety of contemporary records evidencing Joseph Smith’s life and ministry and his role as President of the Church. The Documents Series will contain his outgoing and incoming correspondence, scribal reports of his sermons (because scribal reports are all that exist of his speeches), his written epistles, his revelations in context, minutes of meetings—including conferences—at which he spoke, and essays and articles which he wrote or commissioned to be written under his name, along with various and sundry ephemeral items.

Each of the volumes within The Joseph Smith Papers will have two to four coeditors working on each book. My coeditor is Steven R. Sorensen, the former director of the Church Archives at Church headquarters. Our volume covers two years of the Prophet’s life, 1839 and 1840, and includes all of the documentary records for that period that I have mentioned above. I base my essay on several of these documents.

Expulsion from Missouri and Regrouping in Illinois

The story begins in 1838. In the fall of 1838 both the Democratically-controlled Senate and House of Representatives were lost to the surging Whig Party, evidence of President Martin Van Buren’s increasing vulnerability. The unanticipated baggage Van Buren had inherited from his predecessor, Andrew Jackson, had led to the economic reversal known as the Panic of 1837, which still held its grip on Americans. Earlier in the year the Underground Railroad had clandestinely begun operation, spiriting black slaves to liberation in the free states of the North. Sectional issues intensified as the first abolitionist was elected to the House of Representatives. And at the same time as the Saints’ expulsion from Missouri, the winter of 1838–39, a somewhat comparable number of Cherokee Indians were banished by the federal government from Georgia to designated lands in what is now Oklahoma. The weighty matters occupying America’s citizenry in 1838 subordinated the catastrophe consuming the Latter-day Saints in America’s westernmost state, Missouri.

With the Prophet’s followers in a panic after the state of Missouri pressed them into submission and flight, Joseph Smith was subjected to sequential incarcerations beginning the first week of November 1838—first in Independence, then in Richmond, then in Liberty, Clay County, Missouri, where he arrived on December 1, 1838. Four and a half months later, after surviving a bitter winter in the jail’s stone dungeon, Joseph “escaped” with four fellow inmates in collaboration with their sympathetic guards. A week later he was reunited with his wife and children in the Mississippi River city of Quincy, Illinois, on April 22, 1839.

The Prophet and several thousand of his fellow impoverished Latter-day Saint refugees soon made plans to relocate forty-some miles upriver to the villages of Commerce, Illinois, and Montrose, Iowa. On May 10, 1839, Joseph and Emma Smith moved with their four children into a log home near the bank of the huge river, in what would later be called Nauvoo. The emerging city had antecedents that stretched back to the beginning of the century; as early as 1805, government explorer Zebulon Pike marched across the site, and a farmstead was established in what later became Nauvoo. The first permanent white settler moved to this bend in the Mississippi River in 1823. Others followed. Six years later, the same year Hancock County was organized, the few who inhabited the future Mormon site established a post office with the exotic name of Venus. Five years later the small frontier village became Commerce, and a sister settlement, Commerce City, was organized three years later. The beauty of the peninsula, located within the westernmost county in Illinois, drew the Saints enthusiastically into the region. Here Joseph Smith’s vision for a flourishing metropolis quickly materialized.

The city’s initial success often masks the difficulties that confronted the new settlers in the late spring and summer of 1839. Indeed, there was nothing easy about preparing the site for occupation by a poverty-stricken people. Joseph Smith’s work as director of operations, city developer, and institutional strategist complemented the Saints’ significant efforts to build the new city. During the village’s first summer, Joseph shared the malarial sickbed with his fellow Saints. It was during this discouraging and difficult—though optimistic—period that the Lord inspired the Prophet to call the nascent Quorum of the Twelve Apostles to missionary service in the British Isles. Within weeks most of the Twelve embarked on their missions. While he did not join them in their apostolic mission, neither did Joseph Smith remain behind just to enjoy the fruits of their season’s work in the new city. A significant enterprise that portended great advance for the Church was in the making.

Mission to Washington

Though their frozen limbs had barely thawed from their winter ordeal, the Saints convened a Church conference in May 1839 in Quincy, Illinois, where many were rehabilitating. In the aftermath of their horrific expulsion from their lands and rights in Missouri, they had something on their minds. After all, Missouri officials had purged the state of American citizens whose forebears bore scars evidencing their patriotic sacrifice for free institutions. Because the Church had no representation in the nation’s capital, Sidney Rigdon, forty-six-year-old counselor in the Church’s First Presidency, was appointed by the conference to be the first Church agent to present the Saints’ Missouri plight to the federal government. However, by the time of the October conference that fall a revised strategy emerged. President Rigdon was to be accompanied by Elias Higbee, a very capable former Caldwell County, Missouri, judge, then forty-four; they would also be joined by the thirty-three-year-old Prophet Joseph Smith.

In an interesting window into Church government at the time, the Washington mission was authorized two weeks after the conference, not by the First Presidency or the Quorum of the Twelve, most of whom had left Nauvoo for Great Britain earlier in the year, but by the Nauvoo Stake high council. The next week the council affixed their final approval to a document ratifying the Prophet’s proposal for the trip. The following day, October 29, 1839, Joseph Smith and his team, which included twenty-five-year-old Orrin Porter Rockwell, departed Commerce for Washington. Although Sidney Rigdon, suffering from malaria, was in no shape for travel, he went with the group. After traveling only a hundred miles to the newly designated Illinois state capital of Springfield, Sidney’s worsening condition forced a decision. He needed help or he would have to be left behind. There in Springfield, on November 8 they found a young physician, a twenty-eight-year-old who had apparently just joined the Church by the name of Robert D. Foster, whom they induced to join them and tend to Sidney Rigdon.

With President Rigdon’s debilitation, he turned over all of the letters of introduction written for him and endorsed them to Joseph Smith, along with his own affirmation of Joseph, the latter a document dated November 9, 1839. With the expanded entourage, the group continued eastward, likely traveling by way of the National Road once they were in Indiana. On November 18, the group paused to allow Sidney some relief near Columbus, Ohio. But Joseph could not bear the delay and decided to continue, allowing Sidney time for recovery, accompanied only by Elias Higbee.

The information discussed to this point comes from disparate contemporary records that provide data leading to the Washington mission, as I will refer to it. Hereafter we rely on documents incident to the mission itself. But there is a consideration that we must include here that actually bears on other events surrounding Joseph Smith’s ministry; in particular it informs our understanding of this time in the Prophet’s life. Oftentimes, details of events reconstructed from memory years afterward—especially in the absence of contemporary records—have acquired an enduring shelf life, keeping them in the public discussion of the past. In some cases, though certainly not in all, the memory does not mirror the reality of the incidents. One example concerns the story at hand.

We will begin with the trip itself, where after nearly a month on the road, a notable event occurred that endures as an indicator of Joseph Smith’s character. Dr. Foster, the young physician who joined the Prophet’s small entourage en route to Washington, wrote:

After we got to Dayton, Ohio, we left our horses in care of a brother in the church, and proceeded by stage, part of us; and the same coach that conveyed us over the Allegheny Mountains also had on board, as passengers, Senator Aaron of Missouri, and a Mr. Ingersol, a member of congress, from New Jersey or Pennsylvania, I forget which, and at the top of the mountain called Cumberland Ridge, the driver left the stage and his four horses drinking at the trough in the road, while he went into the tavern to take what is very common to stage drivers, a glass of spirits. While he was gone the horses took fright and ran away with the coach and passengers. There was also in the coach a lady with a small child, who was terribly frightened. Some of the passengers leaped from the coach, but in doing so none escaped more or less injury, as the horses were running at a fearful speed, and it was down the side of a very steep mountain. The woman was about to throw out the child, and said she intended to jump out herself, as she felt sure all would be dashed to pieces that remained, as there was quite a curve in the road, and on one side the mountain loomed up hundreds of feet above the horses, and the other side was a deep chasm or ravine, and the road only a very narrow cut on the side of the mountain, about midway between the highest and lowest parts. At the time the lady was going to throw out the child, Joseph Smith . . . caught the woman and very imperiously told her to sit down

;,and that not a hair of her head or any one on the coach should be hurt. He did this in such confident manner that all on board seemed spell-bound; and after admonishing and encouraging the passengers he pushed open one of the doors, caught by the railing around the driver’s seat with one hand, and with a spring and a bound he was in the seat of the driver. The lines were all coiled around the rail above, to hold them from falling while the driver was away; he loosened them, took them in his hands, and although those horses were running at their utmost speed, he, with more than herculean strength, brought them down to a moderate canter, a trot, a walk, and at the foot of Cumberland Ridge to a halt, without the least accident or injury to passenger, horse or coach, and the horses appeared as quiet and easy afterward as though they had never run away.[1]

Of course, this is quite a story. And there are parts of it that are demonstrably true based on other documentation. But as one can ascertain from the narrative, the writer presents himself as an eyewitness to the event. The difficulty with this is that the narrator, Dr. Foster, who had stayed behind in Ohio with Sidney Rigdon to help him recuperate, was likely not on board the stage. He constructed the story, including names of government officials, for reasons that we do not know. However, there is an eyewitness report by Joseph’s companion, Elias Higbee, written on December 5, 1839 within two weeks of the event, that allows the modern reader to be much closer to the incident. It reads as follows:

We came with one of the Missouri members from Wheeling [in what is now West Virginia] to this place, who was drunk but once, and that however was most of the time; there was but one day but what he could navigate, and that day he was keeled over, so he could eat no dinner. The horses ran away with the stage; they ran about three miles; Brother Joseph climbed out of the stage, got the lines, and stopped the horses, and also saved the life of a lady and child. He was highly commended by the whole company for his great exertions and presence of mind through the whole affair. Elias Higbee [who was the reporter of this event, said of himself that he] jumped out of the stage at a favorable moment, just before they stoped, with a view to assist in stopping them, and was but slightly injured. We were not known to the stage company until after our arrival.[2]

Elias Higbee, now mostly unknown in historical circles because of his premature death in 1843 and the absence of surviving personal papers, had risen to play a significant role in the Prophet’s life at this time. The Twelve, of course, were not available to augment the delegation to Washington. Sidney Rigdon would have undoubtedly played a much more visible and influential part of this venture had his health not precluded him from doing so, and his absence elevated Elias Higbee to the important status of the Church’s first emissary, unofficial as it was, to Washington DC. After Joseph Smith’s encounter with Martin Van Buren, which will be discussed later, the Prophet stayed in or around Washington for three more weeks, trying to muster support for the Saints by lobbying primarily the Illinois delegation to Washington. But after determining that he could do no more in Washington, with confidence he left Elias Higbee alone in the nation’s capital to carry the Saints’ message to all who would listen. Joseph then conducted a ministry tour to groups of Latter-day Saints in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. We know that the Prophet then returned to Washington DC to continue his endeavor with the Congress, along with other enterprises.

Elias Higbee wrote two letters to the Saints in Nauvoo while he was with Joseph Smith in December 1839, and he penned six subsequent letters to Joseph in February and March 1840, after the Prophet’s departure from Washington. These, along with the communications Higbee received from congressional members, serve as the best primary sources of information about Joseph’s and the Church’s efforts with the U.S. president and Congress regarding the Saints’ plea for redress and restoration of their rights in 1839–40.

Arrival in Washington

What we know about the petitioners’ arrival in Washington DC is best represented in Elias Higbee’s letter of December 5, 1839, written to Hyrum Smith in Nauvoo. Higbee reported, “We arrived in this City on the morning of the 28th of November, and spent the most of that day in looking up a boarding house which we succeeded in finding, We found as cheap boarding as can be had in this city.”[3] In 1839, Washington DC was not the pride of American city making. In fact, it was considered a disappointment by many, if not most, Americans, and almost all Europeans, who were accustomed to the glitter and elegance of the flourishing capitals of Europe. One Viennese-born gentleman, Francis Grund, visited Washington somewhat contemporarily to Joseph Smith and wrote upon arriving in the nation’s capital:

The approach to the metropolis is anything but striking. . . .

Washington is, indeed, a city sui generis, of which no European who has not actually seen it can form an adequate idea. [This was not a compliment.] Mr. Serullier, formerly minister of France, used to call it “a city of magnificent distances;” but, though this be true, I should rather call it “a city without streets.” The Capitol, a magnificent palace, situated on an eminence called Capitol-hill, and the White-house, the dwelling of the President, are the only two specimens of architecture in the whole town; the rest being mere hovels, and even the public buildings, such as the Treasury, War and Navy Departments, and the General Post-office, little superior to the most ordinary dwelling-houses in Europe. The whole town is, in fact, but an appendix to those two public buildings, a sort of ante-chamber either to the Capitol or to the house of the chief magistrate. If such a town were situated in Europe, one would imagine those buildings to be the residences of princes, and the rest of the humble dwellings of their dependents.

The only thing that approaches a street in Washington is Pennsylvania Avenue, a sometimes single, sometimes double row of houses, leading from the Capitol to the White-house. In this street are the two principal hotels of the city, and a considerable number of boarding-houses. The former are two large barracks, capable of holding each from one hundred and fifty to two hundred people; the latter are, for the most part, mean insignificant-looking dens, in which a man finds the worst accommodations at the most exorbitant prices, and must often be glad to be accommodated at all.[4]

While we cannot claim that Joseph Smith and Elias Higbee’s experience was identical to Grund’s, the generalities described here conform to other similar opinions of the city and its residents. Grund continues:

The first thing that struck me in Washington was the unusual number of persons perambulating the streets without any apparent occupation, of which every other American city, with the exception of Philadelphia, seems to be entirely drained. If there be poor and idle persons walking the streets of New York, Boston, or Baltimore, it is, I am sorry to say, generally owing to some late arrival from Europe,—some of the steerage passengers being yet left without employment. Washington, however, is a city of American idlers,—a set of gentlemen of such peculiar merit as well to deserve a public comment. They live in what is called “elegant style,” rise in the morning at eight or nine, have breakfast in their own rooms, then smoke five or six cigars until twelve, at which time they dress for the Senate. . . .

The Senate of the United States is, indeed, the finest drawing-room in Washington; for it is there the young women of fashion resort for the purpose of exhibiting their attractions. The Capitol is, in point of fashion, the opera-house of the city; the House of Representatives being the crush-room. In the absence of a decent theatre, the Capitol furnishes a tolerable place of rendezvous, and is on that account frequented during the whole season—from December until April or May—by every lounger in the place, and by every belle that wishes to become the fashion.

After speaking and talking is over in the Senate, the idlers commence the regular performance of eating, which is no sort of amusement to any one in America who is obliged to dine at an ordinary [table]. For this reason they club together in numbers from four to six, to dine at their rooms; single dinners being too expensive, and the people who have the means of entertaining in Washington being not sufficiently numerous to secure every dandy a place at a private gentleman’s table.[5]

It is probably safe to say that, like Grund, Joseph Smith was equally underwhelmed by Washington and its adornments.

President Smith and his associate found lodging for a modest sum just west of the U.S. capitol building on the corner of Missouri and 3rd streets, a site that would today be located on Washington’s National Mall. Elias Higbee’s report to his brethren in Nauvoo continued, “On friday morning [November] 29th, [the day after they arrived] we proceeded to the house of the President—We found a very large and splendid palace, surrounded with a splendid enclosure decorated with all the finiries and elegancies of this world. We went to the door and requested to see the President.”[6]

Audience with the President

We now arrive at the center of the traditional story of Joseph Smith’s audience with the president of the United States, Martin Van Buren. This story has often been repeated by Latter-day Saints and others, although Joseph Smith and Elias Higbee’s efforts with the Illinois delegation to Congress in December 1839 and Higbee’s subsequent efforts on behalf of the Saints with the Senate Judiciary Committee were likely more important and held more promise than their brief encounter with the country’s president.

A contemporary newspaper account dated December 21, 1839, reported on the Mormon delegation (by then including Sidney Rigdon) after they had been in Washington for three weeks:

Several of the Mormon leaders are at present in the city. Their object is to obtain recompense for losses sustained by them in consequence of the outrages committed on them in Missouri. The statement which they have addressed to the President and Congress, presents details of robbery & butchery, at which the heart sickens. Houses burned, men slaughtered in cold blood, women driven into the woods to give birth to their off-spring in the den of the wolf, are pictures too horrible for contemplation. They appear to be peaceful and harmless, and if fanaticism has led them into error, reason, not violence, should be used to reclaim them.

Joe Smith, the leader and prophet of the sect, who professes to have received the golden plates on which the Mormon creed was transcribed, and who has figured so conspicuously in fight, is a tall muscular man, with a countenance not absolutely unintellectual. On the contrary, [he] exhibits much shrewdness of character. His height is full six feet, and his general appearance is that of a plain yeoman, intended rather for the cultivation of the soil, than the expounding of prophecy. Without the advantage of education, he has applied himself, with much industry, to the acquisition of knowledge; and although his diction is inaccurate, and his selection of words not always in good taste, he converses very fluently on the subject nearest to his heart, and whatever may be thought of the correctness of his opinions, no one who talks with him, can doubt that his convictions of their truth are sincere and settled. His eye betokens a resolute spirit, and he would doubtless go to the stake to attest his firmness and devotion, with as little hesitation as did any of the leaders of the olden time. It is not probable that any relief will be obtained by these persons from the Federal Government. Their remedy lies against the State of Missouri. But it is to be apprehended, from the deep sense of their wrongs, which rankles in their hearts, and the determination they evince to right themselves, if they cannot be protected by the law, that they will return to Missouri, and commence a retributive course of action, which, from their number may be productive of greater evils than those which have already occurred. I understand that the followers of this new creed, throughout the United States, already exceeds 200,000, and they are still on the increase. Persecution swells their ranks.[7]

Despite this newspaperman’s view of Latter-day Saint objectives at the time, only Mormons and Mormon observers, for the most part, were interested in Joseph Smith’s visit with Martin Van Buren. Van Buren’s biographers do not mention Joseph Smith or his visit with the president; Van Buren’s own nearly eight-hundred-page autobiography does not mention Joseph Smith or the Mormons (although it doesn’t mention his wife or marriage either). In Van Buren’s own papers, now part of the Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, the visit is not described. The several newspaper reports that later noted Joseph Smith and his small entourage’s presence in Washington did not mention him visiting with Van Buren. And other than two letters of introduction (one from Sidney Rigdon and the other from James Adams, a friend of Joseph Smith’s from Springfield, Illinois) presented by Joseph Smith to the president (now part of the president’s papers), no other documentation that I know of survives, except the following.[8]

Sixteen years after the fact, John Reynolds, the former governor of Illinois who became a U.S. congressman from Illinois in 1834, penned a memoir published in 1855. In it he described his role in the historic encounter:

In December, 1839, the prophet, Joseph Smith, appeared at Washington City and presented his claims to Congress for relief for the losses he and the Mormons sustained in Missouri at the City of the Far West.

When the prophet reached the city of Washington, he desired to be presented to President Van Buren.

I had received letters, as well as the other Democratic members of congress, that Smith was a very important character in Illinois, and to give him the civilities and attention that was due him. He stood at the time fair and honorable, as far as we knew at the city of Washington, except his fanaticism on religion. The sympathies of the people were in his favor.

It fell to my lot to introduce him to the President, and one morning the prophet Smith and I called at the white house to see the chief magistrate. When we were about to enter the apartment of Mr. Van Buren, the prophet asked me to introduce him as a “Latter-Day Saint.” It was so unexpected and so strange to me . . . that I could scarcely believe he would urge such nonsense on this occasion to the President. But he repeated the request, when I asked him if I understood him. I introduced him as a “Latter-Day Saint,” which made the President smile.[9]

Regrettably, Congressman Reynolds failed to include a report of the meeting’s content, leaving Higbee’s report as the primary source of information about the Prophet’s audience with the president.

It should be remembered that Van Buren was of Joseph’s father’s generation, having been born in 1782. When Joseph met him, the president was fifty-seven; Joseph, as mentioned, was thirty-three. Upon their arrival at the president’s mansion, the White House, Elias Higbee wrote, “We were immediately introduced into an upper apartment where we met the President and were introduced into his parlor, where we presented him with our Letters of introduction; as soon as he had read one of them, he looked upon us with a kind of half frown and said, what can I do? I can do nothing for you,—if I do any thing, I shall come in contact with the whole State of Missouri.”[10]

For generations this statement has been the iconic symbol of the Saints’ poor treatment by the federal government. At one time I tried to track the expression in Church literature and from tabernacle pulpits. Before long, it became evident that the account had been so pervasively recounted that calculating its breadth and distribution was of little value. It is etched into the corpus of our identity.

Before we move on to investigate the meaning of this encounter more broadly, let us consider the other things that Elias Higbee mentioned in his letter to his Nauvoo brethren. Even though the president had dismissed their plea, Higbee wrote: “We were not to be intimidated, and demanded a hearing and constitutional rights—Before we left him he promised to reconsider what he had said, and observed that he felt to sympathize with us on account of our sufferings,—Now we shall endeavor to express our feelings and views concerning the President, as we have been eye witnesses of his Majesty.”[11] While Higbee mocked the president’s regal air in biblical language—having been “eyewitnesses of his majesty” (2 Peter 1:16)—he also implied, perhaps, that Van Buren may have been willing to think more about the plea.

While I do not want to make too much of this, and because it is something that I am not entirely settled upon at present, that Van Buren was willing to “reconsider” his initial retort to their pleas suggests that perhaps later he might revisit with them the matter. It is a point of dispute as to whether Joseph Smith did indeed visit the president twice. A particular reading of the History of the Church implies that there was a later visit to the president, probably at the end of January or beginning of February 1840, after Joseph Smith had returned to Washington subsequent to his visits to the Saints in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. There is other evidence—some persuasive, I believe—that there was a second visit. However, there are contradictions within the evidence that may preclude us from ever knowing if the president and Joseph Smith met more than once. Whether there was a second visit or not, however, does not alter the story.

Report of John Reynolds

Before continuing, I want to return to some other things that John Reynolds said about Joseph Smith and the Mormons. Given his forthright declarations in his memoir, one particular acknowledgment is consequential, in light of what may appear to be dismissive criticism. Reynolds wrote in 1855:

In all the great events and revolutions in the various nations of the earth nothing surpasses the extraordinary history of the Mormons. The facts in relation to this singular people are so strange, so opposite to common-sense, and so great and important, that they would not obtain our belief if we did not see the events transpire before our eyes. No argument, or mode of reasoning, could induce any one to believe that in the nineteenth century, in the United States, and in the blaze of science, literature, and civilization, a sect of religionists could arise on delusion and imposition. But such are the facts, and we are forced to believe them. This sect, amid persecutions and perils of all sorts, has reached almost half a million souls, scattered over various countries, within twenty-five or thirty years.[12]

As Joseph and Elias entreated the Illinois congressional delegation to the Mormons’ Missouri plight, John Reynolds drew some conclusions about the Mormon leader: “Smith, the prophet, remained in Washington a great part of the winter, and preached often in the city. I became well acquainted with him. He was a person rather larger than ordinary stature, well proportioned, and would weigh, I presume, about one hundred and eighty pounds. He was rather fleshy, but was in his appearance amiable and benevolent. He did not appear to possess any harshness or barbarity in his composition, nor did he appear to possess that great talent and boundless mind that would enable him to accomplish the wonders he performed.”[13]

While Reynolds remained stumped by the contrast of Joseph’s humble circumstance and demeanor in juxtaposition to his notable accomplishments, he made this remarkable deduction: “No one can fore tell the destiny of this sect, and it would be blasphemy, at this day, to compare its founder to the Saviour, but, nevertheless it may become veritable history, in a thousand years, that the standing and character of Joseph Smith, as a prophet, may rank equal to any of the prophets who have preceded him.”[14]

There is also something else to note about John Reynolds before we leave him, and though it sounds like trivia, it is an irony much more than that. John’s brother was Thomas Reynolds, then the governor of Missouri. At the time of John’s acquaintance with Joseph Smith, Thomas Reynolds began efforts to extradite Joseph Smith to Missouri for alleged crimes that Thomas, as a Missouri judge, had dismissed before his ascension to the governorship.

Views about Van Buren

As mentioned previously, there is regrettably no record extant from President Van Buren that describes Joseph Smith, their visit together, or his opinion of the Mormons. However, we do have one viewpoint of the event and its outcome; the importance of Elias Higbee’s record, again, is noted. In his December 5th, 1839, portrait of the eighth president, he said:

He is a small man, sandy complexion, and ordinary features; with frowning brow and considerable body but not well proportioned, as [are] his arms and legs—and to use his own words is quite fat—On the whole we think his is without boddy or parts, as no one part seems to be proportioned to another—Therefore instead of saying boddy and parts we say body and part, or partyism if you please to call it, and in fine to come directly to the point, he [is] so much a fop or a fool, (for he judged our cause before he knew it,) we could find no place to put truth into him—We do not say the Saints shall not vote for him, but we do say boldly, (though, it need not be published in the streets of Nauvoo, neither among the daughters of the Gentiles) that we do not intend [that] he shall have our votes.[15]

While this statement and subsequent ones by Joseph Smith indict Martin Van Buren in person and principal, the story is much larger than this encounter. While some of Van Buren’s contemporaries disliked the president immensely, a condition applicable to many who have political rivals, there is a fairly uniform consensus among modern scholars that Van Buren was an honorable man and somewhat of a remarkable politician. Indeed, he is acknowledged by many to be the founding father of modern political parties. How can we explain the incongruity of Van Buren being an honorable man and yet completely indifferent to the Saints’ plight? There were three primary factors, in my judgment, that help explain this dilemma. I will identify these only generally and briefly. The first factor was Van Buren’s preoccupation with getting reelected. In late 1839, Van Buren’s return to the White House as a Democratic president, like that his two-term predecessor Andrew Jackson, was by no means guaranteed. The second factor was the condition of the country. The entirety of Van Buren’s administration had been a struggle; many considered the country to be in a mess. Not only were most national issues filtered through the contentions of sectionalism, not the least of which was slavery (something that Van Buren adamantly defended), but the residual effects of the Panic of 1837 also pulled down the country’s economic-bearing walls within two months of his assuming office, crippling any economic advance that he had hoped to make. Plus, there were international troubles with Great Britain that some thought might explode into war. The third and probably most important factor was that Mormons did not matter in the political landscape, especially in light of what they asked of the president.

Interceding on the Saints’ behalf against the state of Missouri would have required Van Buren to violate the very foundation of his political persona, the premise upon which he believed he had made his career and achieved his ascension to the presidency—the protection of states’ rights. Many have discussed Van Buren’s apparent inability to initiate federal intervention to protect American citizens and execute their demands for redress from an offending state. It is true that post–Civil War constitutional amendments that arguably provided for such intervention were not enacted at this time. But even if there had been statutes on the books that provided for federal action, it is my judgment that Van Buren was so concerned about keeping sectional animosity at bay that he would not have acted on the Saints’ behalf, even if he had had the law and the means to do so. Mormons did not matter. They were on nobody’s “radar,” to use today’s parlance. They especially were of no concern when it came to pitting the president’s entire career against what would have accelerated the unthinkable at the time—the unraveling of the republic.

This political worldview of the primacy of states’ rights was so fundamental to Van Buren, and his posture was so widely known among Americans, that it appears plausible to me that Joseph Smith did not go to Washington ignorant of what he might encounter. I have difficulty believing that the Mormons were that naive about the instincts and disposition of their nation’s president regarding the matter of states’ rights. If there is one word to describe what everyone knew about Van Buren, and it has been used repeatedly to describe him, even by modern scholars, it is the word “cautious.” A cautious states’ rights advocate likely never would have considered what the Saints proposed.

And, frankly, the president had other matters on his mind. The president’s annual message to Congress, delivered on December 2, 1839, just three days after his visit with Joseph Smith, was filled with his national agenda, including the mismanagement of Native American Indian difficulties, which he called an “embarrassment.” But his message centered on his continuing emphasis regarding the primary ambition of his presidency, the establishment of an independent national treasury. This goal was of such importance to the president, and he pushed so hard for its enactment, that until 1840 it dominated the discussions of the 26th Congress.[16]

Importuning at the Feet of the President

So how do we account for Joseph Smith’s venture to Washington? It may be rooted in a December 1833 revelation received by Joseph Smith regarding the eventual redemption of Zion—which, of course, was what underlay the redress petitions. My views about the effect of this revelation in the Prophet’s subsequent thinking and behaviors are informed by the work of my colleague Mark Ashurst-McGee. In his recently completed doctoral dissertation, he argues that the counsel in section 101 of the Doctrine and Covenants, regarding the Saints’ petition for government intervention in the aftermath of their expulsion from Jackson County, provided directives that motivated much of their future strategy. What I am advancing now, however, is my own interpretation of what compelled Joseph Smith to go to Washington. The divine logistics in applying for redress for wrongs committed against the Saints included this provision: “Let them importune at the feet of the judge; and if he heed them not, let them importune at the feet of the governor; and if the governor heed them not, let them importune at the feet of the president; and if the president heed them not, then will the Lord arise and come forth out of his hiding place, and in his fury vex the nation” (Doctrine and Covenants 101:86–89).

It is appears that there was nothing received by Joseph Smith later to mute this strategy. This revelatory directive was not necessarily a formula that anticipated the president’s refusal to act on behalf of the Saints. Joseph Smith apparently went to Washington informed of the president and his policies but with the expectation that Van Buren would somehow intuit through divine inspiration the necessity of aiding the Saints. The Saints, after all, were primarily Democrats. They had reason to believe that not only would they be heard, but that they would be justified. Joseph Smith’s disappointment came when it was apparent that Van Buren’s politics not only preempted the divinely granted freedoms of the Constitution but also spurred a heart hardened to the revelation and inspiration of God. The parallel to Moses’ encounter with Egypt’s pharaoh is vivid. It appears to me that Joseph Smith went to Washington thinking that Martin Van Buren would acquiesce and accept the pleas of a “much injured people.” John Reynolds explained the reversal in Joseph’s views in light of both the president and Congress: “His claim for damages done to the Mormons in Missouri, was submitted to the Senate, and both the senators of Missouri, Messrs. Benton and Lynn [Linn], attacked his petition with such force and violence that it could obtain scarcely a decent burial. Smith returned to the State of Illinois a red-hot Whig.”[17]

Frustration after the Visit

Joseph Smith arrived back in Nauvoo in early March of 1840. Coincidentally, his arrival at home coincided with the Whig Party assaulting Martin Van Buren, determined to unseat him in the fall election. Three newspaper reports in the spring of 1840 captured Joseph Smith’s immediate views upon his return to Nauvoo after his education in Washington. They illustrate, with whatever journalistic license we allow newspapermen or newspaper stringers, the Prophet’s thinking. On Sunday, March 22, a writer for the New York Journal of Commerce reported a discourse by Joseph Smith given to the Illinois Saints explaining his Washington experience:

After engaging in prayer to the Most High, and reading a chapter of sacred writ, he [Joseph Smith] commenced his discourse. He told his people he was their servant; that they had a right to know all the incidents of his journey; he would therefore endeavor to give them a minute account. He did [not] like to preach politics on the Sabbath, but he must free his mind, must tell the whole story.

The object of his visit at Washington, you well know, was to make application to congress for relief, touching their troubles in Missouri. But to the discourse. He said, on his arrival at Washington, he, with two of his elders, (Rigdon and Higbee,) called on Mr. Van Buren at the “White House” with a letter of introduction, and after making known to him the subject of their visit, and soliciting him to help them, Mr. Van Buren replied “Help you! How can I help you? All Missouri would turn against me.” But they demanded of Mr. Van Buren a hearing, and he, after listening a few moments to their tale of injured innocence, abruptly left the room. After waiting some time for his return, they were under the necessity of departing, disappointed, and chagrined.[18]

Apparently one of the reasons that Joseph Smith was so outraged over Van Buren’s response was that he had been subjected to personal insult, even though the president’s reputation was one of respectful deportment. Not having Van Buren’s side of the story, we do not know whether the president was busy or irritated about something else that would have influenced his treatment of the small delegation. The newspaper report continued: “He thought Mr. Van Buren treated them with great disrespect and neglect, and in conversation, among other things, [Joseph] told the president that he (the president) was getting fat. The president replied that he was aware of the fact; that he had to go every few days to the tailor’s to get his clothes let out, or purchase a new coat. The “prophet” here added, at the top of his voice,—‘he hoped he would continue to grow fat, and swell, and, before the next election burst!’”[19]

It appears that Joseph Smith took every occasion in the immediate weeks after his return to Nauvoo to report on Van Buren’s insult. At the general conference of April 7, Joseph’s rehearsal of what happened in Washington was reported by a Peoria, Illinois, newspaper:

On the first day [of the conference] Mr. S[mith], took occasion to give to the assembled multitude, consisting of about 3000 persons, a detailed account of his mission, which was related with great clearness, and heard with deep interest. He said that soon after reaching Washington, he called on Mr. Van Buren, and asked permission to leave with him the memorial with which he had been entrusted, at the same time briefly stating its contents. Mr. Van Buren’s manner was very repulsive, and it was only after his (Smith’s) urgent request that he consented to receive the paper and to give an answer on the morrow. The next day Smith again called [here is one of those contradictory sources that we have to sort out], when Mr. Van Buren cut short the interview by saying, “I can do nothing for you, gentlemen. If I were you, I should go against the whole state of Missouri, and that state would go against me in the next election.” Mr. Smith said he was thunderstruck at this avowel. He had always believed Mr. Van Buren to be a high-minded statesman, and had uniformly supported him as such; but he now saw that he was only a huckstering politician, who would sacrifice any and every thing to promote his re-election. He left him abruptly, and rejoiced when without the walls of the palace, that he could once more breathe the air of a freeman.[20]

In April 1840, another journalist-traveler, this one from the Alexandria [Virginia] Gazette, gave this report of Joseph Smith’s description of his visit to Washington by way of personal conversation:

It was a beautiful morning towards the close of April last [1840], when the writer of the foregoing sketch, accompanied by a friend, crossed the Mississippi River, from Montrose [Iowa], to pay a visit to the prophet. . . . We descended from his chamber, and the conversation turned upon his recent visit to Washington, and his talk with the President of the United States. He gave us distinctly to understand that his political views had undergone an entire change; and his description of the reception given him at the executive mansion was anything but flattering to the distinguished individual who presides over its hospitalities.

Before he had heard the story of our wrongs, said the indignant Prophet, Mr. Van Buren gave us to understand that he could do nothing for the redress of our grievances lest it should interfere with his political prospects in Missouri. He is not as fit said he, as my dog, for the chair of state; for my dog will make an effort to protect his abused and insulted master, while the present chief magistrate will not so much as lift his finger to relieve an oppressed and persecuted community of freemen, whose glory it has been that they were citizens of the United States.[21]

The net effect of the Mormon delegation to Washington in 1839–40 was frustrating disappointment, their entreaties dismissed by both the president and Congress. I previously implied that Joseph Smith changed his thinking about American government institutions and political personalities in the aftermath of his experience in Washington, as illustrated by the newspaper reports quoted above. But he had not given up on the foundational premise of American institutions being beholden to the people. In what was perhaps the first sermon he delivered upon his arrival home after the Washington venture, he reminded the Saints, as reported by his uncle John Smith, that “the affairs now before Congress [concerning the Saints] was the only thing that ought to interest the Saints at present. . . . He requested every exertion to be made to forward affidavits to Washington, and also letters to members of Congress.”[22]

In a subject for another time, what Joseph Smith did subsequent to his encounter with the president and Congress inaugurated what has been described as his role as statesman-prophet. Certainly Joseph Smith’s view of his prophetic ministry had expanded through his defense of his fellow Saints before the chief magistrates of the time. And he would petition another day.

Notes

[1] Robert D. Foster, “A Testimony of the Past: Loda, Illinois, February 14, 1874,” The True Latter Day Saints’ Herald (April 15, 1875): 225–26.

[2] Joseph Smith and Elias Higbee to Hyrum Smith, December 5, 1839, Washington City, “Corner Missouri and 3d Street,” Joseph Smith Collection, Letterbook 2:85–88, Church History Library.

[3] Joseph Smith and Elias Higbee to Hyrum Smith, “Corner Missouri and 3d Street,” Letterbook 2:85–88.

[4] Francis J. Grund, Aristocracy in America: From the Sketch-Book of a German Nobleman (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1959), 229–30.

[5] Grund, Aristocracy in America, 231.

[6] Joseph Smith and Elias Higbee to Hyrum Smith, “Corner Missouri and 3d Street,” Letterbook 2:85–88.

[7] Adams Sentinel, December 30, 1839.

[8] November 9, 1839: Rigdon, Sidney. Springfield, Ill. To Martin Van Buren and the Heads of Departments, Washington. Introducing Joseph Smith, Jr., and Elias Higbee, Mormons. A.L.S. 1 p.; and November 9, 1839: Adams, J. Springfield, Illinois, To M[artin] Van Buren, Washington. Introducing two Mormons, Joseph Smith, Jr., and [Elias] Higbee. A.L.S. 1p. Library of Congress: Calendar of the Papers of Martin Van Buren (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1910), 382.

[9] John Reynolds, My Own Times: Embracing Also the History of My Life (Chicago: Fergus Printing, 1879), 367.

[10] Joseph Smith and Elias Higbee to Hyrum Smith, “Corner Missouri and 3d Street,” Letterbook 2:85–88.

[11] Joseph Smith and Elias Higbee to Hyrum Smith, “Corner Missouri and 3d Street,” Letterbook 2:85–88.

[12] Reynolds, My Own Times, 359.

[13] Reynolds, My Own Times, 367.

[14] Reynolds, My Own Times, 359.

[15] Joseph Smith and Elias Higbee to Hyrum Smith, “Corner Missouri and 3d Street,” Letterbook 2:85–88.

[16] The Congressional Globe: Containing Sketches of the Debates and Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth Congress, First Session, Volume VIII (Washington: Globe, 1840).

[17] Reynolds, My Own Times, 368.

[18] Reprinted in “The Mormons for Harrison,” Peoria Register and North-Western Gazetteer, April 17, 1840.

[19] “The Mormons for Harrison.”

[20] “The Mormons for Harrison.”

[21] The [New York] Sun, July 28, 1840. This article, which received wide circulation, initially appeared in the Alexandria [Virginia] Gazette. It also appeared in the [Hartford] Connecticut Courant, August 29, 1840; and the Quincy [Illinois] Whig, October 17, 1840.

[22] Iowa Stake, Records, 1839–41, March 6, 1840, Church History Library.