Images of Wilford Woodruff's Life: A Photographic Journey

Alexander L. Baugh

Alexander L. Baugh, “Images of Wilford Woodruff’s Life: A Photographic Journey,” in Banner of the Gospel: Wilford Woodruff, ed. Alexander L. Baugh and Susan Easton Black (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2010), 1–64.

Alexander L. Baugh was a professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this article was published.

Historians who have researched and written about the lives of the latter-day prophets and apostles unanimously conclude that each of these men lived remarkable lives. Wilford Woodruff was no exception. But he was different from his predecessors and successors in one particular way—he left an incredibly detailed handwritten record, spanning over sixty years, of just about everything he did and experienced. Furthermore, as he came to realize and sense just how much he actually accomplished, it amazed even himself. One example will suffice. In 1896, at the age of eighty-nine, still two years before his death, he numerically totaled his life and ministry. Here are just a few of the figures he gives—traveled 172,369 miles, held 7,455 meetings, attended 75 general conferences, attended 344 quarterly conferences, preached 3,526 discourses, organized 51 branches of the Church, added 1,800 people to the Church in Great Britain (1,043 of whom he personally baptized), confirmed or assisted in confirming 8,942 persons, oversaw 3,188 proxy baptisms and 2,518 endowments in behalf of his own deceased family members and friends, wrote 11,519 letters, received 18,977 letters—and the list goes on.[1]

Wilford Woodruff’s life of ninety-one years came just a few years short of spanning the entire nineteenth century (1807–98), something relatively uncommon then, although not as uncommon today. He outlived his two predecessors—Brigham Young (1801–77) by twenty-one years and John Taylor (1808–87) by eleven years. He was born on the East Coast in Connecticut and died on the West Coast in California, with the majority of his life spent in the high, arid mountain valleys of Utah. He journeyed from Arizona in the south to the western Canadian provinces in the north (British Columbia and Alberta), traveling even to Alaska. And he served two extended missions to Great Britain. For a person who lived in America during the nineteenth century, he could certainly be classified as living a life well traveled and full of adventure. The scope of this photographic essay is to capture for the reader some of the places and events that characterized the remarkable life of this humble servant and Church leader.[2]

Fig. 1. Birthplace and boyhood home of Wilford Woodruff. Photograph by Junius F. Wells, 1892, published in the Contributor, September 1892, 473.

Fig. 1. Birthplace and boyhood home of Wilford Woodruff. Photograph by Junius F. Wells, 1892, published in the Contributor, September 1892, 473.

Early Years and Young Adulthood

Born March 1, 1807, in Farmington (now Avon), Hartford County, Connecticut, Wilford was the third and youngest son of Aphek Woodruff (1778–1861) and Beulah Thompson (1772–1808).[3] The family home where Wilford was born stood for many years. In 1892, when Wilford Woodruff was eighty-five years old and serving as President of the Church, Junius F. Wells traveled to Connecticut to try to locate some of the properties associated with President Woodruff’s early life. Significantly, Wells discovered that the home where President Woodruff was born was still standing and photographed the structure (see fig. 1).[4] In 1998, a monument commemorating President Woodruff’s birthplace was erected under the sponsorship of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in a community park situated about three-quarters of a mile east of the Woodruff family home (see fig. 2).[5]

Fig. 2. Wilford Woodruff birthplace marker, Fisher Meadows Park, Avon, Connecticut, November 2007. The monument was dedicated on April 24, 1999, by Elder Donald L. Staheli of the Second Quorum of the Seventy. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 2. Wilford Woodruff birthplace marker, Fisher Meadows Park, Avon, Connecticut, November 2007. The monument was dedicated on April 24, 1999, by Elder Donald L. Staheli of the Second Quorum of the Seventy. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

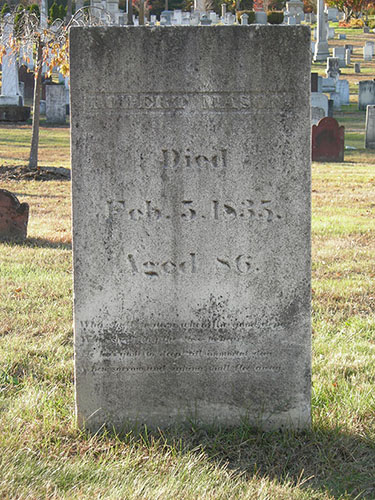

Fig. 3. Grave marker of Beulah Thompson Woodruff, mother of Wilford Woodruff, West Avon Congregational Church Cemetery, West Avon, Connecticut, November 2007. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 3. Grave marker of Beulah Thompson Woodruff, mother of Wilford Woodruff, West Avon Congregational Church Cemetery, West Avon, Connecticut, November 2007. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

On June 11, 1808, tragedy struck the Woodruff family when Beulah died at the age of twenty-six from spotted fever, leaving Aphek a widower to care for his three young sons—Azmon (age five), Ozem (age three), and Wilford (fifteen months).[6] Dinah Woodruff, Wilford’s paternal grandmother, also helped care for the children.[7] Still an infant, Wilford was too young to have any memories of his birth mother. However, in his early adulthood, his feelings for his mother surfaced. In July 1837, three and a half years after embracing Mormonism, while en route to Maine to preach the restored gospel, Wilford passed through Farmington, stopping for a time to visit family and relatives. His short stay there included a brief visit to the cemetery where many of his loved ones, including his mother, were buried (see fig. 3). His entry for July 6, 1837, reflects his feelings of the moment:

I gazed . . . upon the grave yard in which lay the bones of many of my progenitors & friends [and] my Mother. . . .

I read the following inscription upon the TOMB stone of my Mother BULAH WOODRUFF the daughter of Lot Thompson:

A pleasing form a generous gentle heart

A good companion Just without art

Just in her dealings faithful to her friend

Beloved through life lamented in the end}[8]

On November 9, 1810, Aphek married Azubah Hart. Together they raised Azmon, Ozem, and Wilford, and had six more children of their own (Wilford’s half brothers and half sister)—Philo (b. 1811), Asahel (b. 1814), Franklin (b. 1816), Newton (b. 1818), Julius (b. 1820), and Eunice (1821).[9]

Fig. 4. Remains of the millrace that was part of a mill owned and operated by Wilford’s father, Aphek Woodruff, Avon, Connecticut, November 2007. As a boy Wilford worked at the mill at this site with his father until 1816, when Aphek sold the mill and property to a man by the name of Phineas Lewis. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 4. Remains of the millrace that was part of a mill owned and operated by Wilford’s father, Aphek Woodruff, Avon, Connecticut, November 2007. As a boy Wilford worked at the mill at this site with his father until 1816, when Aphek sold the mill and property to a man by the name of Phineas Lewis. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

During Wilford’s formative years, the Woodruff family lived on a forty-acre farm, but Aphek’s livelihood centered in milling (see fig. 4). “My father was a strong constitutioned man,” Wilford wrote, “and has done a great amount of labor. At eighteen years of age, he commenced attending a flouring and saw mill, and continued about 50 years, most of this time he labored eighteen hours a day.”[10] When not enrolled in school, young Wilford followed his father’s line of work, laboring with him until the age of twenty (1827) when he struck out on his own. For the next seven years (1827–34) he managed and operated four separate mills.[11] However, in April 1834, four months after embracing Mormonism, he permanently abandoned the vocation.

Conversion to Mormonism

Fig. 5. Robert Mason grave, Simsbury Cemetery, Simsbury, Connecticut, November 2007. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 5. Robert Mason grave, Simsbury Cemetery, Simsbury, Connecticut, November 2007. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

About the same time he left home (1827), Wilford began an intensive personal examination of the Bible and attended religious meetings of both the Methodists and Congregationalists, supplicating God in earnest prayer in an effort to find the primitive Christian faith. In his early years he and his brother Azmon had come under the influence of a self-proclaimed prophet, Robert Mason, a former Episcopalian turned Congregationalist, living in Simsbury, Connecticut. In the spring of 1830, Wilford visited the eighty-year-old Mason once again. In the course of their visit, Mason rehearsed a vision he experienced some thirty years earlier. In the vision he found himself in a large orchard of fruit trees, none of which bore any fruit. The trees soon began to fall to the earth until none were left standing, but shortly thereafter, shoots began springing up forming new and beautiful trees with ripened fruit. While he was attempting to eat some of the fruit, the vision closed. Mason said he asked God to reveal the meaning of the revelation, which was given him as follows: “This is to show you that my Church is not organized among men in the generation to which you belong; but in the days of your children the Church and Kingdom of God shall be made manifest with all the gifts and blessings enjoyed by the Saints in past ages. You shall live to made acquainted with it, but shall not partake of its blessings before you depart this life.” After rehearsing the vision, Mason told Wilford, “I shall never partake of this fruit in the flesh, but you will and you will become a conspicuous actor in the new kingdom.” Continuing, Wilford stated, “Three years later which I was baptized into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, almost the first person I thought of was . . . Robert Mason. Upon my arrival in Missouri with Zion’s Camp, I wrote him a long letter in which I informed him that I had found the true gospel. . . . He received my letter with great joy. . . . He was very aged and soon died without having the privilege of receiving the ordinances of the gospel”[12] (see fig. 5). Confident that God would direct his path, Wilford continued his religious quest with assurance that he would eventually find the true Church possessing ancient priesthood and authority to perform the saving ordinances.

In early 1832, Wilford, along with his older married brother Azmon and Azmon’s wife Elizabeth, left Avon and journeyed north and west to Richland, Oswego County, New York, where the two brothers put down $800 on a $1,800, 140-acre farm that also included a home and a sawmill (see fig. 6).[13]

Fig. 6. Map showing the location of Richland, Oswego County, New York.

Fig. 6. Map showing the location of Richland, Oswego County, New York.

On December 29, 1833, two Mormon elders, Zera Pulsipher (from Onondaga County, just south of Oswego County), and his companion, Elijah Cheney, came to Wilford and Azmon’s house. Neither of the two brothers was home, but the Mormon elders informed Azmon’s wife, Elizabeth, about a preaching meeting to be held at a nearby schoolhouse. When the time for the meeting arrived, both Wilford and Azmon attended. Elder Pulsipher was the main speaker. “I felt the spirit of God . . . bear witness that he was the servant of God,” Wilford recorded. “He then commenced preaching, . . . and when he had finished his discourse I truly felt that it was the first gospel sermon that I had ever herd, . . . [and] I could not leeve the house without bearing witness to the truth before the people.”[14] Two days after the meeting, on the last day of the year, December 31, in water mixed with ice and snow, Elder Pulsipher baptized Wilford and Azmon (see fig. 7).[15]

Fig. 7. Zera Pulsipher, date unknown. Pulsipher baptized Wilford Woodruff in Richland, Oswego County, New York, on December 31, 1833. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Fig. 7. Zera Pulsipher, date unknown. Pulsipher baptized Wilford Woodruff in Richland, Oswego County, New York, on December 31, 1833. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Journal Keeper

Beginning in 1834, shortly after conversion to Mormonism, Wilford began keeping a journal. The opening pages of his first journal contain reminiscences of his early years, his conversion to Mormonism, and some of the events associated with his early months in the Church in Richland. He made a few sporadic entries beginning April 26, 1834, when he first arrived in Kirtland, Ohio, followed by a number of entries recounting some of his experiences on Zion’s Camp. However, in January 1835, he began making regular daily entries, a practice which he continued until just a few days before his death in 1898, a total of sixty-three years. Reflecting on his personal effort to keep a regular journal, he remarked:

I have many times thought the Quorum of the Twelve and others considered me rather enthusiastic upon this subject; but when the Prophet Joseph organized the Quorum of the Twelve, he counseled them to keep a history of their lives, and gave his reasons why they should do so. I have had this spirit and calling upon me since I first entered this Church. I made a record from the first sermon I heard, and from that day until now I have kept a daily journal. Whenever I heard Joseph Smith preach, teach, or prophesy, I always felt it my duty to write it; I felt uneasy and could not eat, drink, or sleep until I did write; and my mind has been so exercised upon this subject that when I heard Joseph Smith teach and had no pencil or paper, I would go home and sit down and write the whole sermon, almost word for word and sentence by sentence as it was delivered, and when I had written it was taken from me, I remembered it no more. This was the gift of God to me.

The devil has sought to take away my life from the day I was born until now, more so even than the lives of other men. I seem to be a marked victim of the adversary. I can find but one reason for this: the devil knew if I got into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, I would write the history of that Church and leave on record the works and teachings of the prophets, of the apostles and elders. I have recorded nearly all the sermons and teachings that I ever heard from the Prophet Joseph, I have in my journal many of the sermons of President Brigham Young, and such men as Orson Hyde, Parley P. Pratt and others. Another reason I was moved upon to write in the early days was that nearly all the historians appointed in those times apostatized and took the journals away with them.[16]

Zion’s Camp

In early April 1834, Parley P. Pratt, who had come from Kirtland to Richland, visited Wilford and Azmon, informing them that Joseph Smith had received a revelation (Doctrine and Covenants 103) instructing the Church to raise an army, later called Zion’s Camp, to march to Missouri, where they hoped, with the assistance of state militia mustered out by Missouri governor Daniel Dunklin, to assist the Saints who had been expelled from Jackson County. Wilford agreed to volunteer and wasted no time in settling his affairs, while Azmon chose to remain. On April 11, accompanied by two other local recruits, Harry Brown and Warren Ingles, Wilford left Richland. Although he probably anticipated returning at some point, as events played out, his departure ended up being permanent, although he visited on occasion.[17]

Wilford made the three-hundred-mile journey from Richland to Kirtland in two weeks, arriving on April 25. Here, he met Joseph Smith for the first time and even boarded at his home until May 1, when he left Kirtland bound for Missouri in the first company of the Mormon army. Although Zion’s Camp experienced a number of hardships and setbacks during the two-month-long trek to western Missouri (not to mention the return), his personal record and his later reminiscences fail to reveal the slightest hint of negativism or complaint, and, in fact, it appears he relished the adventure.

Fig. 8. Naples–Russell Mound #8, also known as Zelph’s Mound, Pike County, Illinois, October 2006. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 8. Naples–Russell Mound #8, also known as Zelph’s Mound, Pike County, Illinois, October 2006. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Wilford’s journal highlights several notable events that occurred during the Zion’s Camp expedition, but a particular event stands out as most unusual and extraordinary. On June 3, while camped on the western side of the Illinois River in Pike County, Illinois, several members of the company made an unusual discovery. While exploring and investigating a prominent mound near the river, several men unearthed the skeletal remains of the large man whom the Prophet Joseph Smith subsequently identified as an ancient Nephite warrior-leader named Zelph, who had been killed in battle centuries before. Intrigued, Wilford retained a thigh bone with the intent of reburying it in Jackson County after their arrival as a memorial to the fallen warrior.[18] The mound where the remains were found, identified today as Naples–Russell Mound #8, has been excavated by archaeologists, but the outline of the mound is still plainly visible (see fig. 8).[19]

As Zion’s Camp continued their westward journey through northern Missouri, word reached the company that Governor Dunklin had made the decision not to call out the state militia to assist the Saints, thereby eliminating the possibility that Church members would be restored to their homes and property. In spite of the unwelcome news, the camp pushed forward, intent on completing the journey. On June 22, while camped on a parcel of property belonging to fellow member John Cooper, who lived on the eastern border of Clay County, Joseph Smith received a revelation informing the company that because of the present circumstances, the redemption of Zion would yet be future (see Doctrine and Covenants 105:9). Furthermore, they were assured that their journey and sacrifice were not performed in vain. “I have heard their prayers, and will accept of their offering,” the Lord declared, indicating that it was expedient that the journey was undertaken “for a trial of their faith” (Doctrine and Covenants 105:19).

Fig. 9. Site of the Michael Arthur property situated about three miles south of Liberty, Missouri, May 2002. From July 1834 to January 1835, Wilford Woodruff lived with Lyman Wight. The two men contracted with Arthur to make a hundred thousand bricks and build the two-story home shown above (the first of the above two images). The home was razed around 1970. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh. Inset photograph courtesy of Bill Curtis, Independence, Missouri.

Fig. 9. Site of the Michael Arthur property situated about three miles south of Liberty, Missouri, May 2002. From July 1834 to January 1835, Wilford Woodruff lived with Lyman Wight. The two men contracted with Arthur to make a hundred thousand bricks and build the two-story home shown above (the first of the above two images). The home was razed around 1970. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh. Inset photograph courtesy of Bill Curtis, Independence, Missouri.

On July 3, a general meeting was held for the Saints then living in Missouri and the members of Zion’s Camp. The meeting was held on the property owned by Michael Arthur, situated about three miles south of Liberty. Arthur, a non-Mormon, had befriended the exiled Saints and employed a number of them. During the meeting, Joseph Smith officially disbanded Zion’s Camp and instructed them that they were free to return to their homes. While most men returned to their families in Ohio and elsewhere, Wilford, who was single, chose to remain in Clay County and secure employment. From July 1834 through early January 1835, Wilford lived with Lyman Wight. Together, the two men contracted with Michael Arthur to manufacture one hundred thousand bricks and construct a two-story home (see fig. 9).[20]

Marriage to Phoebe Carter

In January 1835, Wilford Woodruff embarked on his first proselyting mission, which lasted twenty-two and a half months and took him into the backwoods of Arkansas, Tennessee, and Kentucky. In late November 1836, he made his way back to Kirtland, where he found a bustling Mormon community and a stately temple. “I truly felt to rejoice at the Sight,” he wrote, “as it was the first time that mine eyes ever beheld the house of the Lord built by Commandment & Revelation.”[21]

Fig. 10. Joseph Smith home, Kirtland, Ohio, 2007. Wilford and Phoebe Carter were married in this home on April 13, 1837, by Frederick G. Williams. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 10. Joseph Smith home, Kirtland, Ohio, 2007. Wilford and Phoebe Carter were married in this home on April 13, 1837, by Frederick G. Williams. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

The first few months of 1837 were eventful days. His journal records the spiritual exuberance he felt worshipping with the Saints in the temple, attending meetings with his fellow Quorum of the Seventy members, participating in the ordinances of the Kirtland endowment, receiving his patriarchal blessing under the hands of Joseph Smith Sr., and listening to Joseph Smith preach. In late January 1838, Wilford was introduced to Phoebe Whitmore Carter, from Scarborough, Maine, who had joined the Church in 1834 and moved to Kirtland. Wilford and Phoebe were not only the same age (twenty-nine), but they were also born within a week of each other. Following a two-and-a-half-month courtship, they were married on April 13, 1837, by Frederick G. Williams, Second Counselor in the First Presidency, at the home of Joseph Smith (see fig. 10).[22]

Mission to New England and the Fox Islands

On May 31, 1837, just over six weeks after his marriage, Wilford embarked on his second extended mission. “I felt impressed by the Spirit of God to take a mission to the Fox Islands [Maine’s coastal islands], . . . a country he knew nothing about,” he wrote years later.[23] The fact that Phoebe was from Maine probably helped to influence his decision. And he wanted her to accompany him—after all, they were newlyweds—so she could live with her family while he proselyted and be relatively close to his field of labor. Wilford also knew the gospel was to be taken “unto the isles of the sea,” and although the Fox Islands lay just a few miles from Maine’s eastern shore, they still qualified as isles.

Wilford Woodruff and his companion Jonathan H. Hale first set foot on North Haven Island on August 20, 1837. The pair wasted no time in getting an audience, and secured permission from Gideon J. Newton, a Baptist minister, to preach at the Baptist meetinghouse that very night using Galatians 1:8–9 as his text. Writing about this occasion, Wilford recorded, “This was the first time that I or any Elder of the Church, (to my knowledge) ever arose before the inhabitants of one of the Islands of the sea to preach unto them the fullness of the everlasting gospel and the Book of Mormon.”[24] The meetinghouse where he delivered his first sermon on the island is still in use today (see fig. 11).

Fig. 11. Baptist meetinghouse on North Haven Island, Maine, June 2002. Wilford Woodruff delivered his first sermon on the north island at this meetinghouse on August 20, 1837. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 11. Baptist meetinghouse on North Haven Island, Maine, June 2002. Wilford Woodruff delivered his first sermon on the north island at this meetinghouse on August 20, 1837. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

From August 1837 until May 1838, Wilford labored primarily on the two Fox Islands (North Haven and Vinal Haven, the south island), but he also journeyed to the mainland, where he preached in a number of localities on Maine’s coastal shore. But most of his success took place on the two large islands. Following Elder Hale’s return to Ohio in October 1837 (they were together less than two months), Phoebe accompanied Wilford for two weeks before returning to her parents’ home in Scarborough. In January 1838, Wilford was joined by Elder Joseph Ball. The pair worked together for three months, after which Wilford was left to proselyte and preach on his own.

During the summer of 1838, Wilford left the Fox Islands and spent several weeks in Connecticut, and more particularly in Farmington, with his parents and other extended family members. On July 1, an exultant Wilford baptized his father; his stepmother, Azube; his half sister, Eunice; an uncle; two aunts; and two cousins.[25] Fourteen month earlier, in pronouncing upon Wilford his patriarchal blessing, Joseph Smith Sr. declared, “Thou are of the Blood of Ephraim . . . [and] if thou will claim it by faith thou mayest bring all of the [thy?] relatives into the Kingdom of God.”[26] Given the fact that by this time all of his immediate family members had joined the Church, one might think that the blessing was fulfilled. However, in later years, Wilford personally performed the vicarious temple ordinances for scores of other relatives, thus bringing about even greater fulfillment of the blessing.

In early August, he returned to the Fox Islands, where on August 9, he received a letter from Thomas B. Marsh in Far West, Missouri, notifying him of the revelation appointing him to be a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles (see Doctrine and Covenants 118). For the next three months, Wilford made arrangements for the Fox Island Saints to gather and relocate with the main body of the Church in Caldwell County, Missouri. Eight families, consisting of fifty-three people, left Maine to begin their overland journey on October 3. On December 19, two-and-one-half months later, having covered over a thousand miles, near Rochester, Illinois (located just a few miles southeast of Springfield), the company learned about Missouri governor Lilburn W. Boggs’s extermination order forcing the Saints to leave the state. Because of the situation, Wilford and the Fox Island Saints chose to spend the winter of 1838–39 near Rochester. The Woodruff family remained here until April 8, 1839, when they temporarily relocated to Quincy, Illinois.[27]

Ordination to the Apostleship

In mid-April, Brigham Young determined that the members of the Twelve who had relocated to Quincy should return to Far West, Missouri, to fulfill the revelation calling them to take leave from the temple site on April 26, 1839, for their missions to Great Britain (see Doctrine and Covenants 118:5). Accordingly, on April 18, Wilford Woodruff, in company with Brigham Young, Orson Pratt, John Taylor, and George A. Smith, crossed the Mississippi River into Missouri and made their way to Caldwell County. En route, John E. Page joined their company. On the evening of April 25, they arrived in the vicinity of Far West, where they were met by fellow Apostle Heber C. Kimball (who had remained in Missouri), bringing the total number of Apostles to seven. During the early morning hours of the appointed day, the Twelve ceremoniously recommenced laying the southeast cornerstone (the temple site had been previously dedicated on July 4, 1838). Although Wilford and George A. Smith had received their appointments to the Twelve, neither had been ordained, so the five ordained Apostles performed the ordinance—Woodruff first, followed by Smith—on the southeast cornerstone (see fig. 12). Following several prayers and the singing of the hymn “Adam-ondi-Ahman,” the company immediately left to make their way east back to Quincy.[28]

Montrose, Iowa

Fig. 12. Far West Temple site, southeast cornerstone, September 1996. Wilford Woodruff and George A. Smith were ordained Apostles on the cornerstone on April 26, 1838. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 12. Far West Temple site, southeast cornerstone, September 1996. Wilford Woodruff and George A. Smith were ordained Apostles on the cornerstone on April 26, 1838. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

In May 1839, with the help of Isaac Galland, a land speculator, the Mormons negotiated the purchase of property straddling both sides of the Mississippi River forty miles north of Quincy in Lee County, Iowa, and in Commerce (later Nauvoo), Hancock County, Illinois, for Mormon settlement. That same month Wilford moved his family into an abandoned army barrack, formerly part of Fort Des Moines, at Montrose on the Iowa side of the river. Just a few weeks after the Mormons began settling the area, an outbreak of malaria struck the region, afflicting nearly every household to some degree. On July 22, in an attempt to curb the sickness, Joseph Smith, assisted by members of the Twelve and others, administered priesthood blessings to scores of Church members scattered in homes, tents, and makeshift shelters on both sides of the river. After witnessing the Prophet perform a number of miraculous healings among the Saints in Montrose a non-Mormon whose five-month-old twins were gravely ill requested that the Prophet come to his house two miles away and administer to his children. The Prophet was about to ferry across to the Illinois side, so he could not give the blessing, but he turned to Elder Woodruff and said, “You go with the man and heal his children.” Wilford reported, “He took a red silk handkerchief out of his pocket, gave it to me, told me to wipe their faces with the handkerchief when I administered to them, and they should be healed.” The Prophet continued: “As long as you will keep that handkerchief, it shall remain a league between you and me.” Wilford did as he was told. “I went with the man, did as the Prophet commanded me, and the children were healed. I have possession of the handkerchief unto this day.”[29] In 2005, during the bicentennial anniversary of Joseph Smith’s birth, the Church History Museum in Salt Lake City displayed the handkerchief (see fig. 13).

Fig. 13. Joseph Smith’s silk handkerchief given to Wilford Woodruff on July 22, 1839, on display in the Church History Museum, 2005. Photograph by Kenneth R. Mays.

Fig. 13. Joseph Smith’s silk handkerchief given to Wilford Woodruff on July 22, 1839, on display in the Church History Museum, 2005. Photograph by Kenneth R. Mays.

Mission of the Twelve to Great Britain, 1839–41

On August 8, 1839, although somewhat ill from the lingering effects of the summer sickness that plagued the Saints, Wilford Woodruff and John Taylor left Commerce bound for Great Britain, the first of the Twelve to make their departure. The pair docked in Liverpool on January 11 and immediately began proselyting. Their fellow Apostles arrived four months later. During this mission Wilford labored for a total of sixteen months on British soil, primarily in three areas: (1) the Potteries (six communities that comprise Stoke-on-Trent in the Staffordshire region); (2) the tricounties of Worcester, Gloucester, and Herefordshire; and (3) London.

Significantly, of the nine members of the Twelve who labored in Great Britain on this mission, Elder Woodruff probably had the most success in terms of converts. At the close of 1840, he reported having assisted in the conversion of some fifteen hundred people, having personally baptized 336.[30] Considering the fact that he continued to labor in Great Britain until April 1841 (an additional four months), the number of converts he was responsible for might be closer to two thousand. Nowhere did he experience more success than in Herefordshire among the United Brethren, a break-off of the Methodists headed by Thomas Kington. Elder Woodruff succeeded in converting more than half of the entire church’s members, many of whom were baptized on the farm property of John Benbow, whose pond became a regularly used site for Mormon baptisms (see fig. 14).[31] Additionally, following the conversion of nearly the entire congregation of United Brethren near in Gadfield Elm, the chapel they had built in 1836 became the first Latter-day Saint meetinghouse in Great Britain and probably the entire Church.[32] In 1994, a group of Latter-day Saints in Great Britain formed a trust and bought the Gadfield Elm building, which had fallen into disrepair. However, through their efforts, the meetinghouse was restored in 2000. In May 2004, the group who had formed the trust gave ownership of the restored chapel to the Church (see fig. 15).[33]

Fig. 14. Benbow pond on the property once belonging to John Benbow, Herefordshire, England, June 2006. Many early Mormon converts were baptized in the pond. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 14. Benbow pond on the property once belonging to John Benbow, Herefordshire, England, June 2006. Many early Mormon converts were baptized in the pond. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 15. Restored Gadfield Elm chapel, Worcestershire, England, August 2001. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 15. Restored Gadfield Elm chapel, Worcestershire, England, August 2001. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

On April 20, 1841, seven of the Twelve, including Elder Woodruff, set sail from Liverpool on the ship Rochester to return to the States. During his absence, Phoebe had gone to live with her parents in Scarborough, so after arriving in New York, Wilford traveled to Maine where, on June 2, he was reunited with his wife following an absence of twenty-two months. Sadly, during his mission to Great Britain, their first child, Sarah, had died. However, in the meantime, Phoebe had given birth to the couple’s first son, Wilford Owen. The Woodruffs spent the entire summer visiting Phoebe’s family in Scarborough and Wilford’s family in Avon, Connecticut, before returning to Nauvoo in early October.

Nauvoo

Wilford settled quickly into the Nauvoo lifestyle and became an active participant in the community’s local affairs. Although he had many ecclesiastical responsibilities associated with the apostleship, he also served as a city councilman, assistant chaplain in the Nauvoo Legion, a member of the Masonic lodge, and co-office manager of the Nauvoo Neighbor and Times and Seasons, and he helped establish the Nauvoo Agricultural and Manufacturing Society. He also assisted in the construction of the Nauvoo House and Joseph Smith’s Red Brick Store.

On October 11, 1841, less than a week after returning from his first mission to Great Britain, Wilford moved his family from Montrose to Nauvoo, where he purchased a small log house near the bluff for eighty-five dollars. On May 22, 1843, Wilford began digging the foundation for a two-story brick home, twenty by thirty-two feet, located on the southwest corner of Hotchkiss and Durphy Streets. Work on the home progressed slowly, partially due to his being called, along with other members of the Twelve, to serve a mission from July to November in the East. The home was finally completed on May 4, 1844 (see fig. 16).[34]

Fig. 16. Wilford and Phoebe Woodruff home, Nauvoo, Illinois, September 2001. Wilford lived in the home a total of sixty days.

Fig. 16. Wilford and Phoebe Woodruff home, Nauvoo, Illinois, September 2001. Wilford lived in the home a total of sixty days.

The Woodruff family did not live in the Nauvoo brick home any great length of time. Five days after its completion, Wilford left on another mission—this one to Indiana, Michigan, New York, Massachusetts, and Maine to promote Joseph Smith’s candidacy for the U.S. presidency. While visiting with his in-laws in Maine, Wilford learned of the Martyrdom, compelling him to return to Nauvoo, where he arrived on August 6. But his stay there was short-lived. On August 12, four days after the meeting in which Brigham Young and the Twelve were sustained as the collective successors to Joseph Smith, Elder Woodruff was appointed to preside over the British mission, with headquarters in Liverpool. On August 28, accompanied by Phoebe and the children, the family left Nauvoo for England. The family’s travels and stay in Great Britain lasted nearly twenty months, after which they returned to Nauvoo on April 13, 1846. Two days later, Wilford sold the brick home and his Nauvoo property to William Allen, a non-Mormon, for $675. The Woodruff’s lived in the home until May 16, when they made their final departure from Nauvoo to begin the trek across Iowa.[35] All told, Wilford lived in the brick home a total of only sixty days.

Iowa and the Western Trek

On July 26, 1846, following a nine-week journey through Iowa Territory, the Woodruffs crossed the Missouri River at Council Bluffs, temporarily settling at Cutler’s Park. They subsequently settled at Winter Quarters, where they spent the winter of 1846–47. In early January 1847, Brigham Young received a revelation for the Camp of Israel containing instructions for outfitting the companies that would make the overland trek that year beginning in April. As a member of the Twelve, Wilford was chosen to be a company leader in the advance party (see Doctrine and Covenants 136:13). On the morning of April 14, he blessed his wife and children, then left them behind to embark on an overland trek to the unsettled Salt Lake Valley and back, a journey that would cover over twenty-two hundred miles.

Fig. 17. Wilford Woodruff’s wagon used on the 1847 trek to the Salt Lake Valley, Pioneer Memorial Museum, Salt Lake City, January 2006. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 17. Wilford Woodruff’s wagon used on the 1847 trek to the Salt Lake Valley, Pioneer Memorial Museum, Salt Lake City, January 2006. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Wilford’s detailed day-by-day journal entries provide an invaluable eyewitness account of the hardships, activities, and experiences of the vanguard company. But perhaps the most spiritually momentous events associated with the journey occurred during the last few days of the overland trek as the companies made their way out of the Wasatch Range. During this last leg, Elder Woodruff was carrying Brigham Young, who was suffering from the effects of Rocky Mountain fever, in a makeshift bed in the back of his wagon. Young later recorded catching their first glimpse of the Salt Lake Valley, which occurred on the afternoon of July 23: “[We] ascended and crossed over Big Mountain, when on its summit I directed Elder Woodruff, who had kindly tendered me the use of his carriage [wagon] to turn the same half way round so that I could have a view of a portion of the Salt Lake valley. The spirit of light rested upon me and hovered over the valley, and I felt that there the Saints would find protection and safety.”[36] The following day, Wilford and Brigham emerged from the mouth of Emigration Canyon, and after ascending a small rise, they had a view of the valley in its entirety. An exultant Wilford recorded: “July 24 1847 This is an important day in the History of the Church of JESUS CHRIST of Latter Day Saints. On this important day after trav[eling] from our encampment 6 miles . . . we came in full view of the great valley or Bason [of] the Salt Lake and land of promise held in reserve by the hand of GOD for a resting place for the Saints upon which A portion of the Zion of GOD will be built.”[37] The wagon used by Wilford on the historic 1847 trek is on display in the Utah Pioneer Memorial Museum in Salt Lake City (see fig. 17).

Elder Woodruff and the other members of the Twelve did not remain in the Salt Lake Valley for very long. Before leaving Winter Quarters, they had decided that after they located and established the main place of settlement, they would return to oversee operations to assist the main body of the Church to emigrate in 1848. The journey back to the Missouri River Mormon encampments took just over two months, less than half the time that it took to get to the valley. On October 31, Wilford recorded: “I drove up to my own door & was truly rejoiced to once more behold the face of my wife & children again after being absent over six months And having travled with the Twelve & the Pioneers near 2,500 miles [the figure was closer to 2,200] & sought out a location for the Saints And Accomplished one of the most interesting mishions ever accomplished at the last days.”[38]

Fig. 18. Replica reconstruction of the Kanesville Tabernacle, Council Bluffs, Iowa, September 2004. The original structure was situated a short distance to the west. Wilford Woodruff was present at the December 27, 1847, meeting in which the First Presidency was reorganized. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 18. Replica reconstruction of the Kanesville Tabernacle, Council Bluffs, Iowa, September 2004. The original structure was situated a short distance to the west. Wilford Woodruff was present at the December 27, 1847, meeting in which the First Presidency was reorganized. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Soon after the return of the Twelve to the Missouri River encampments, Brigham Young held several meetings with the Twelve to discuss his desires to reorganize the First Presidency. After considerable deliberation, on December 5, 1847, nine of the Apostles gave their approval to reconstitute the First Presidency with Brigham Young as President and Heber C. Kimball and Willard Richards as counselors. However, it was also deemed necessary to bring the matter before the general Church membership. To do this, plans were put into place to immediately erect a log tabernacle in Kanesville (present-day Council Bluffs, Iowa) which would accommodate as many as a thousand attendees. In less than three weeks, the structure was erected, and on December 27, exactly three and one-half years to the day since Joseph Smith’s martyrdom, the new First Presidency was approved and sustained (see fig. 18).[39]

The Eastern States Mission

Elder Woodruff probably anticipated he would relocate his family to the Salt Lake Valley in the early spring along with the other members of the Twelve. However, during the April 1848 Kanesville general conference, he was appointed to preside over the Eastern States Mission and to establish headquarters in Massachusetts. Accordingly, on June 21, Elder and Sister Woodruff and their children headed east. Following a tedious seven-week journey by wagon, lake steamer, canal boat, and rail, the Woodruffs arrived in the Boston area on August 12 and eventually secured a residence in Cambridge.

Fig. 19. Original home of Ezra and Sarah Fabyan Carter, parents of Phoebe Carter Woodruff, Scarborough, Maine, June 2002. Wilford and Phoebe visited and stayed with the Carters on several occasions from 1837 to 1850. Ezra, Sarah, three of their daughters, and one son were baptized into the Church. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 19. Original home of Ezra and Sarah Fabyan Carter, parents of Phoebe Carter Woodruff, Scarborough, Maine, June 2002. Wilford and Phoebe visited and stayed with the Carters on several occasions from 1837 to 1850. Ezra, Sarah, three of their daughters, and one son were baptized into the Church. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

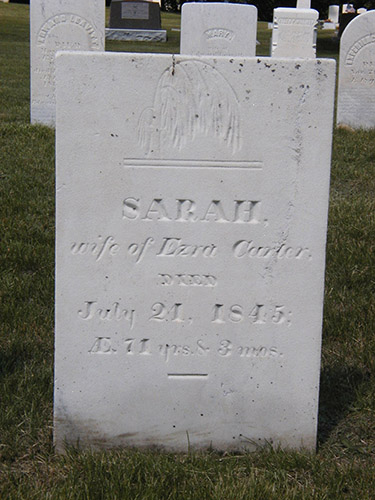

While living in Cambridge, Wilford and Phoebe had frequent contact with Phoebe’s family, particularly her parents who lived less than a hundred miles away in Scarborough, Maine. Significantly, in early 1849, while Ezra Carter, Phoebe’s father, was visiting the Woodruff family in Cambridge, Wilford baptized him. “I led my father in law Ezra Carter Sen[ior] and two others down into the sea And Baptized them,” Wilford wrote under the date of March 22. “Mrs Woodruff accompanied her Father to the water And Back again. . . . . [He] was 76 . . . and 3 days old this day that I baptized him. I have now baptized my Father woodruff & Father in law Carter. This is a great Consolation to my soul.” Phoebe’s mother, Sarah Fabyan Carter; three sisters; and one brother also subsequently joined the Church (see figs. 19, 20, and 21).[40]

Fig. 20. Grave marker of Ezra Carter (b. February 14, 1773, d. March 10, 1868, age 95), father of Phebe Carter Woodruff, Duston Cemetery, Scarborough, Maine, June 2002. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 20. Grave marker of Ezra Carter (b. February 14, 1773, d. March 10, 1868, age 95), father of Phebe Carter Woodruff, Duston Cemetery, Scarborough, Maine, June 2002. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 21. Grave marker of Sarah Fabyan Carter (b. April 8, 1775, d. July 21, 1845, age seventy-one), mother of Phoebe Carter Woodruff, Duston Cemetery, Scarborough, Maine, June 2002. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 21. Grave marker of Sarah Fabyan Carter (b. April 8, 1775, d. July 21, 1845, age seventy-one), mother of Phoebe Carter Woodruff, Duston Cemetery, Scarborough, Maine, June 2002. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

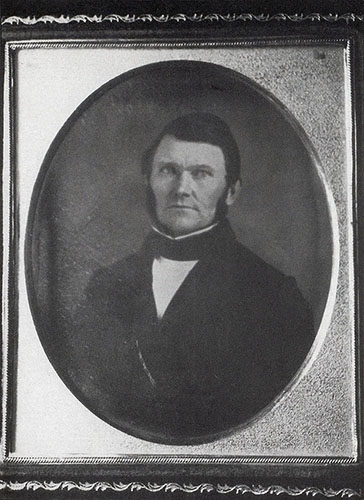

During the eighteen months Elder Woodruff presided over the Eastern States Mission, his responsibilities included not only supervising ongoing missionary work and preaching from New Jersey to New Brunswick, but also strengthening the branches and encouraging and assisting the Saints living in the mid-Atlantic states, New England, and Canada’s maritime provinces to gather with the main body of Saints in the Intermountain West. At home and on the road he enjoyed reading newspapers and books and writing letters, including the occasional prose. Fishing was his number-one amusement, but he enjoyed it only occasionally. Other pastimes included attending lectures, agricultural fairs, science exhibits, parades, and auctions; visiting foundries; shopping; and conducting personal business. While in the Boston area, he and Phoebe had the first known photographic images (daguerreotypes) taken of them by Marsena Cannon. One of those images, taken in 1849 or 1850, shows him in a fine suit, clean-shaven, with thick, dark hair and penetrating but soft eyes (see fig. 22).[41] A photograph of Phoebe, probably taken by Cannon later when the couple was in Utah, shows her in a colorful dress and dark dress coat holding a book, perhaps a copy of the Book of Mormon (see fig. 23).

Following the October 1849 general conference, Brigham Young sent word to Elder Woodruff to return to Salt Lake City. Accordingly, in early 1850, Elder Woodruff began making plans for the cross-country trip. After reaching Council Bluffs in May, Woodruff’s company began an arduous four-month journey on the overland trail, overrun by gold rushers also heading west. Their journey came to an end when they entered the Salt Lake Valley on October 14. Significantly, the completion of the 1848–50 mission to the eastern states, Woodruff’s seventh, also marked the end of his full-time missionary service, a period totaling over ten years (see table 1). From this time on, although his apostolic duties necessitated that he travel throughout the Mormon settlements in the Intermountain West and later the Pacific Coast, he lived the rest of his life in Salt Lake City, the only exceptions being when he lived for short periods of time in Randolph, Utah, in the early 1870s (Sarah Brown Woodruff, one of his plural wives, lived there); when he lived periodically in southern Utah while presiding over the over the St. George Temple (1877–84); and when he went into hiding in various locales to avoid arrest for practicing plural marriage (1879–80 and 1885–87).

Fig. 22. Wilford Woodruff daguerreotype taken in Boston while he presided over the Eastern States Mission, by Marsena Cannon, 1849 or 1850. Woodruff recorded in his journal that he had an image of him taken by Cannon on at least three occasions during the eighteen months he presided over the mission: March 14, 1849, May 16, 1849, and February 18, 1850. Wilford would have been forty-two or forty-three years old. Photograph courtesy of the Church History Museum, Salt Lake City.

Fig. 22. Wilford Woodruff daguerreotype taken in Boston while he presided over the Eastern States Mission, by Marsena Cannon, 1849 or 1850. Woodruff recorded in his journal that he had an image of him taken by Cannon on at least three occasions during the eighteen months he presided over the mission: March 14, 1849, May 16, 1849, and February 18, 1850. Wilford would have been forty-two or forty-three years old. Photograph courtesy of the Church History Museum, Salt Lake City.

Fig. 23. Phoebe Carter Woodruff, daguerreotype probably taken in Salt Lake City, Marsena Cannon photography, ca. 1850. Photograph courtesy of the Church History Museum, Salt Lake City.

Fig. 23. Phoebe Carter Woodruff, daguerreotype probably taken in Salt Lake City, Marsena Cannon photography, ca. 1850. Photograph courtesy of the Church History Museum, Salt Lake City.

Table 1. Wilford Woodruff’s missionary service, 1835–50.

| Wilford Woodruff’s Missionary Service, 1835–1850 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Arkansas, Tennessee, and Kentucky | January 13, 1835–November 25, 1836 | 1 yr., 10 ½ mos. |

| Fox Islands, Maine, and Connecticut | May 31, 1837–December 19, 1838 | 1 yr. 6 ½ mos. |

| Great Britain | August 8, 1839–October 6, 1841 | 2 yrs., 2 mos. |

| Eastern States | July 7–November 4, 1843 | 4 mos. |

| Eastern States | May 9–August 6, 1844 | 3 mos. |

| Great Britain | August 12, 1844–April 13, 1846 | 1 yr., 8 mos. |

| Eastern States | June 21, 1848–October 14, 1850 | 2 yrs., 4 mos. |

Total: 10 yrs., 2 mos. | ||

Fig. 24. Wilford Woodruff’s adobe brick home, situated on the northeast corner of West Temple and South Temple Streets, date unknown. The home faced South Temple. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Fig. 24. Wilford Woodruff’s adobe brick home, situated on the northeast corner of West Temple and South Temple Streets, date unknown. The home faced South Temple. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

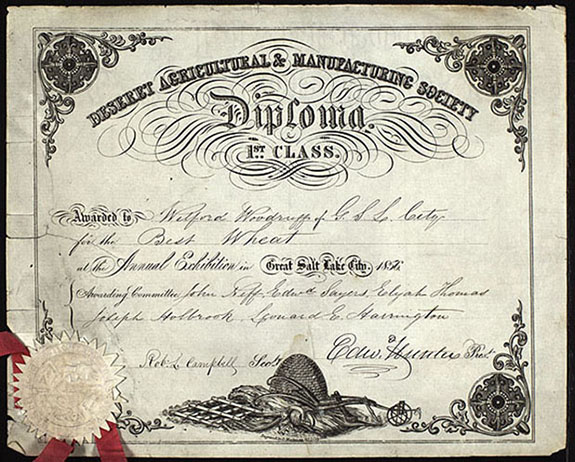

Fig. 25. Certificate awarded to Wilford Woodruff by the Deseret Agricultural and Manufacturing Society in 1856 for the best specimen of wheat. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Fig. 25. Certificate awarded to Wilford Woodruff by the Deseret Agricultural and Manufacturing Society in 1856 for the best specimen of wheat. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Salt Lake City Years

Within just a few days of his return from the East, Wilford moved two cabins he had constructed inside the original fort enclosure built in 1847 to a lot situated southwest of the temple block on what is today the northeast corner of West and South Temple streets. On this property, Elder Woodruff supervised the construction of a comfortable two-story adobe brick home (called the valley home) which became his and Phoebe’s main place of residence until 1871, when a new, smaller brick home was constructed south of the adobe home (see fig. 24).

During the early 1850s, Elder Woodruff earned his livelihood as a merchant, but by 1856 his main economic enterprise centered on farming, gardening, and raising livestock. Ever a promoter of agriculture, in 1855 he helped organize the Deseret Horticultural Society, and he played an active role in the establishment of the Deseret Agricultural and Manufacturing Society in 1856, where he won numerous awards and where he served as president from 1862 until 1877 (see fig. 25).

In civic affairs he was appointed a member of the short-lived legislature of the provisional State of Deseret, and he served for several terms in both the House and Senate of the Utah territorial legislature. In addition he was a member of the Board of Regents of the University of Deseret (later the University of Utah), and for a time he served as a chaplain in the territorial militia.

Recognizing Elder Woodruff’s invaluable skills as a record keeper led the First Presidency and his fellow Apostles to appoint him historian and clerk of the Quorum of the Twelve on December 22, 1852. Four years later his responsibilities expanded with his being called as assistant Church historian on April 7, 1856, a position he occupied until October 5, 1883, when he was sustained as Church historian and recorder.[42] He continued in that capacity until 1889.

St. George Temple President

Of all the members of the Twelve who served during the nineteenth century, perhaps none were more passionate regarding the importance of performing temple ordinances than Wilford Woodruff. In his journal he recorded a number of instances in Nauvoo where he performed baptisms for the dead in behalf of deceased family members and relatives in the Mississippi River (some of them even after the Prophet Joseph Smith instructed that they no longer be performed outside the temple), in the Nauvoo Temple baptistry, and even in the Missouri River when the Saints were preparing for the exodus to the West.[43] After 1855, Elder Woodruff regularly supervised and performed temple ordinances in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City. One historian reported he worked there at total of 605 days.[44] When it came time for the ailing and aging Brigham Young to appoint someone to preside over the St. George Temple, Elder Woodruff was the natural choice.

On November 1, 1876, Brigham Young, Wilford Woodruff, and several Mormon dignitaries left Salt Lake City for St. George, where the temple was in the final stages of completion. On January 1, the temple was sufficiently finished for the formal dedication. Wilford Woodruff offered the main dedicatory prayer, followed by additional dedicatory prayers given by Erastus Snow and Brigham Young Jr., also of the Twelve. At the close of the dedicatory prayers, a feeble Brigham Young gave some remarks, followed by a closing number by the choir, after which the three-hour meeting came to a close.[45]

Although large numbers of Latter-day Saints had been receiving their endowments in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City for over twenty years, the completion of the St. George Temple meant that the entire Church membership at large could receive their own ordinances in a dedicated temple. Not surprisingly, the ensuing months were busy ones for Woodruff as hundreds of Saints came to the St. George to receive their own endowments.

On January 9, nine days after the temple dedicatory services, Elder Woodruff performed the first temple proxy ordinances—baptisms for the dead for 141 persons, with Brigham Young pronouncing the confirmations. Two days later, the first endowments were performed in behalf of the dead.[46]

Recognizing the need to standardize the endowment ceremony, on January 14, Brigham Young commissioned Elder Woodruff and Brigham Young Jr. “to write out the Ceremony of the Endowments from Beginning to End,” a process that would take several weeks to complete.[47] On February 12, nearly a month later, Elder Woodruff recorded, “I spent the day writing on the Ceremonies & we spent the Evening with President Young reading the Ceremony.”[48] By March 21, the text for the temple endowment and sealing ceremonies was essentially complete. On this day Wilford wrote, “Presidet Young has been laboring all winter to get up a perfect form of Endowments as far as possible. They have been perfected I read them to the Company today.”[49]

Wilford Woodruff did not perform a proxy endowment of his own until March 30, 1877. “This is the first day I ever went [to] the [Temp?]le to get Endowments for the Dead,” he wrote. “I got Endowments to day for . . . . Robert Mason”—the same Robert Mason who spiritually mentored Woodruff during his younger years and told him he would live to embrace the true gospel. He also acted as proxy in the conferral of the priesthood, being ordained to two offices in behalf of Mason—high priest and patriarch.[50]

Although Wilford Woodruff’s service as the president of the St. George Temple and his invaluable labors in formalizing the temple ceremonies should not be underestimated, perhaps what he is most noted for in regard to temple work is his vision of the Founding Fathers, who appeared to him requesting the temple ordinances be performed in their behalf. He received this remarkable epiphany sometime in mid-August 1877, although he uncharacteristically made no mention of the vision in his journal. Nonetheless, in mid-September, while in Salt Lake City, he publically declared what took place:

I will here say, . . . that two weeks before I left St. George, the spirits of the dead gathered around me, wanting to know why we did not redeem them. Said they, “You have had the use of the Endowment House for a number of years, and yet nothing has ever been done for us. We laid the foundation of the government you now enjoy, and we never apostatized from it, but we remained true to it and were faithful to God.” These were the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and they waited on me for two days and two nights. I thought it very singular, that notwithstanding so much work had been done, and yet nothing had been done for them. The thought never entered my heart, from the fact, I suppose, that heretofore our minds were reaching after our more immediate friends and relatives. I straightway went into the baptismal font and called upon brother McCallister to baptize me for the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and fifty other eminent men, making one hundred in all, including John Wesley, Columbus, and others; I then baptized him for every President of the United States, except three; and when their cause is just, somebody will do the work for them.[51]

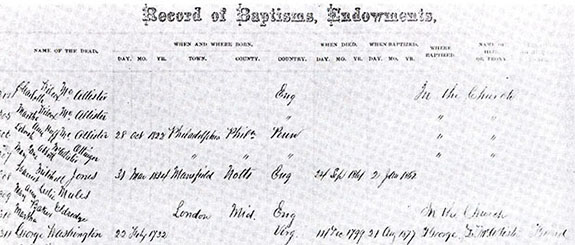

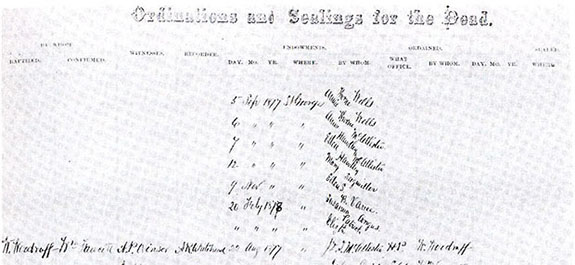

Entries in his journal beginning on August 21 and continuing through August 24 show what work was done and for whom. On August 21, he recorded that his assistant, John D. T. McAllister, baptized him for one hundred men (although the list in his journal gives only ninety-nine), including the signers of the Declaration of Independence (with the exception of John Hancock and William Floyd) and a number of other prominent men. Elder Woodruff also baptized McAllister for twenty-one individuals (including the deceased U.S. presidents), and Lucy Bigelow Young (a plural wife of Brigham Young) was baptized for seventy eminent women.[52] During the next three days, August 22–24, the endowment, including ordinations to the priesthood in behalf of the men, was administered for these individuals. Elder Woodruff specifically noted that George Washington, John Wesley, Benjamin Franklin, and Christopher Columbus were ordained to the office of high priest (see figs. 27 and 28).[53]

Fig. 26. St. George Temple Record, Book B, showing that John D. T. McAllister acted as the baptism proxy for George Washington on August 21, 1877 (#311). Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Fig. 26. St. George Temple Record, Book B, showing that John D. T. McAllister acted as the baptism proxy for George Washington on August 21, 1877 (#311). Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Fig. 27. Continuation of the St. George Temple Record, Book B, showing that Wilford Woodruff performed the baptism of John D. T. McAllister for George Washington. McAllister also acted as proxy for the endowment and ordination to the priesthood (high priest), with Wilford Woodruff performing the priesthood ordination. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Fig. 27. Continuation of the St. George Temple Record, Book B, showing that Wilford Woodruff performed the baptism of John D. T. McAllister for George Washington. McAllister also acted as proxy for the endowment and ordination to the priesthood (high priest), with Wilford Woodruff performing the priesthood ordination. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Polygamy Underground

Brigham Young’s death on August 29, 1877, elevated John Taylor to senior member of the Quorum of the Twelve, with Wilford Woodruff next in seniority.[54] However, like his predecessor Brigham Young, Taylor did not immediately reorganize the First Presidency but waited until the October 1880 general conference, when he was sustained as President of the Church, with George Q. Cannon and Joseph F. Smith as counselors.

During President Taylor’s administration, the Church encountered stiff political opposition from the federal government, primarily in the form of antipolygamy legislation from passage of the Edmunds Act (1882), which forced Mormon leaders, including Elder Woodruff, to go into hiding to avoid arrest and prosecution. Passage of the Edmunds-Tucker Act (1887) led to the disenfranchisement of the Church.

The year 1885 was a painful one for Woodruff. Hiding from the authorities caused him to be away from his quorum associates, friends, and loved ones, particularly his beloved Phoebe, whose health steadily declined. In October she took a bad fall, and within a few weeks her death became imminent. On November 2, Wilford left Atkinville, near St. George, where he had been living on the polygamy underground, and traveled to Salt Lake to be with Phoebe during her last days and hours. On November 9 he wrote: “At 6 oclock I Called to see my wife Phoebe who was vary low. I laid my hands upon her head & Blessed her And anointed her for her burial and at 2 oclok [November 10] she died.”[55] Her funeral service was held on November 12 in the Salt Lake Fourteenth Ward schoolhouse, but fearing arrest, Wilford did not attend. She was buried in the Salt Lake City Cemetery with the following epitaph, penned by her husband, inscribed on her grave marker:

Sleep on my dear Phebe, but ere long from this

The conquered tomb shall yield its captive prey

Then thou with husband, children, friends, in bliss

Shall reign a queen for an eternal day (see Fig. 29)[56]

Fig. 28. Grave marker of Phoebe Carter Woodruff, Salt Lake City Cemetery, May 2006. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 28. Grave marker of Phoebe Carter Woodruff, Salt Lake City Cemetery, May 2006. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

For the next two years, Woodruff was on the alert and frequently in seclusion. A favorite place of hiding was with the William and Rachel Atkin family, whose home lay ten miles southwest of St. George. Atkinville, as it was called locally, was an idyllic retreat for Elder Woodruff because it included a large pond where he could enjoy his favorite pastimes, fishing and hunting.[57]

Woodruff was in southern Utah in July 1887 when he began receiving reports of President John Taylor’s deteriorating condition. Sensing the worst, he and a small party left St. George on July 17 to travel to northern Utah to be with the President, who was in seclusion at the home of Thomas Rouche in Kaysville. However, on July 25, while Elder Woodruff’s company was en route through central Utah, Taylor died. Upon learning of his death, Wilford wrote, “President John Taylor Died to day, . . . which Lays the responsibility of the Care of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints upon my shoulders. . . . This places me in a vary Peculiar situation, A Position I have never looked for during my life. But in the Providence of God it is laid upon me, And I pray God my Heavenly Father to give me Grace Equil to my Day.”[58] He arrived in Salt Lake on July 28 and privately viewed Taylor’s remains in the Gardo House. Still fearing arrest, he did not attend the funeral service the following day, but watched as the procession passed the President’s office.

President of the Church

In the first few months of his leadership, President Woodruff and other Church officials were successful in negotiating with federal officials, judges, and U.S. marshals to “soften [their] attacks on the Latter-day Saints” and “relieve old and sick church leaders [i.e., Wilford Woodruff] . . . from the strain of potential prosecution.”[59] Although a number of Mormon polygamists continued to be arrested and prosecuted, authorities generally left President Woodruff alone, allowing him come and go in public as he pleased.

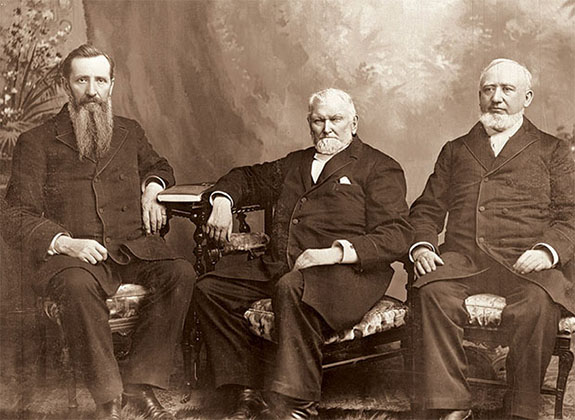

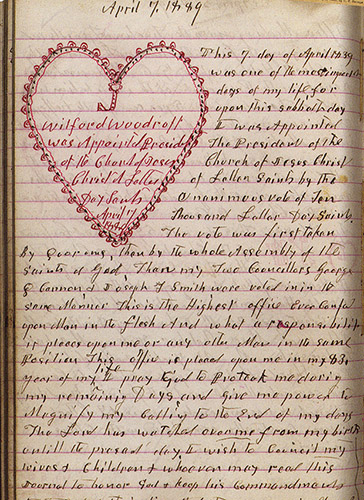

Because of internal disagreements among some members of the Twelve at the time of President Taylor’s death, Woodruff chose not to immediately reorganize the First Presidency but waited until the April 1889 general conference. By this time, the issues among the Twelve had been resolved and more amiable feelings prevailed. His official sustaining and the reorganization of the First Presidency took place on April 7, 1889. George Q. Cannon and Joseph F. Smith were selected as his counselors. Both men had acted as counselors to President Taylor, and both would serve during his entire administration (see fig. 30). On the occasion of his becoming the fourth President of the Church, a humble Wilford Woodruff wrote, “The 7 day of April 1889 was one of the most important days of my life, for upon this sabbath day I was Appointed The President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter [day] Saints by the Unanimous vote of Ten Thousand Latter Day Saints. . . . This is the Highest office Ever Confered upon Man in the flesh And what a responsibility it places upon me or any other Man in the same Position” (see fig. 31).[60]

Fig. 29. Wilford Woodruff (center) with George Q. Cannon, First Counselor (right), and Joseph F. Smith, Second Counselor (left), Sainsbury and Johnson photography studio, 1893. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Fig. 29. Wilford Woodruff (center) with George Q. Cannon, First Counselor (right), and Joseph F. Smith, Second Counselor (left), Sainsbury and Johnson photography studio, 1893. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Fig. 30. Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, April 7, 1889. The entry is on the occasion of his being sustained as the President of the Church and the reorganization of the First Presidency. The image also illustrates how President Woodruff frequently drew sketches and doodled in his journal. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Fig. 30. Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, April 7, 1889. The entry is on the occasion of his being sustained as the President of the Church and the reorganization of the First Presidency. The image also illustrates how President Woodruff frequently drew sketches and doodled in his journal. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

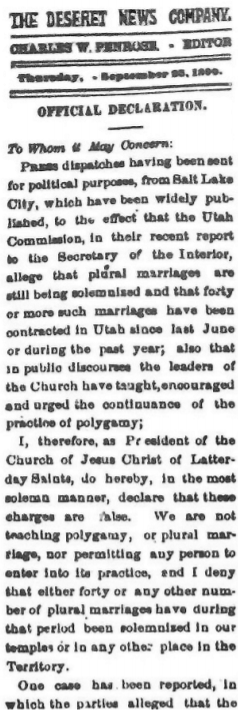

Wilford Woodruff’s progressive leadership role as President of the Church was impressive. He presided at a time when the winds of political, economic, social, and cultural change were blowing, particularly in Utah Territory, and if the Church was to move forward, radical adjustments would need to take place. First and foremost on his mind were the problems associated with the practice of plural marriage. Troubled by the ongoing efforts of the federal government to cripple the Church economically, President Woodruff sought for some type of solution that would cause the government to back off. Eventually, it became clear to him that cessation of plural marriage was the answer. After much discussion among his associates, and realizing the negative consequences that would follow if the Church continued in the practice, he sought for and received divine guidance. On September 25, 1890, he recorded in his journal the following:

I have arived at a point in the History of my life as President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints whare I am under the necessity of acting for the Temporal Salvation of the Church. The United State Governmet has taken a Stand & passed Laws to destroy the Latter day Saints upon the Subjet of poligamy or Patriarchal order of Marriage. And after Praying to the Lord & feeling inspired by his spirit I have issued the following Proclamation which is sustaind by My Councillors and the 12 Apostles.

That entry was immediately followed by an Official Declaration, generally referred to as the Manifesto, essentially declaring that the Church would attempt to bring its marriage practices in compliance with the laws of the land.[61] The announcement was printed in the Deseret News that very day (see fig. 32). Less than two weeks later, on Monday, October 6, the Manifesto was read at the morning session of general conference, where it was accepted by the general membership of the Church.

Fig. 31. “Official Declaration,” Deseret News, September 25, 1890.

Fig. 31. “Official Declaration,” Deseret News, September 25, 1890.

After Phoebe’s death in 1885, Wilford Woodruff’s main residence became the “farm home,” a modest two-story structure built in 1859–60 on his twenty-acre farm property on the outskirts of the city and used primarily as a residence for his wife Emma Smith Woodruff. After succeeding Taylor as Church President, Woodruff kept an office and a room in the Church-owned Gardo House, the official residence of the President of the Church until December 1891, when the structure was turned over to a government receiver, but most of his home time was spent with Emma at the farmhouse.[62] The home remains in the Woodruff family’s possession today and has been kept in excellent condition. It is located at 1604 South 500 East in Salt Lake City (see figs. 33 and 34).[63] Sometime in the early part of 1892, Wilford and Emma moved into the Woodruff Villa, a stately Victorian home built adjacent to the farmhouse the year previous. During a birthday celebration for President Woodruff held at the new residence on March 1, 1892, with members of the First Presidency, Quorum of the Twelve, and Presiding Bishopric and their wives as invited guests, Joseph F. Smith dedicated the home.[64] President Woodruff lived the remainder of his life in the home. The home, located at 1622 South 500 East, is privately owned, but like the farmhouse, it has been well maintained (see fig. 35).[65]

Fig. 32. The Woodruff farmhouse, main residence of Wilford Woodruff from 1885 until 1892, June 2006. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 32. The Woodruff farmhouse, main residence of Wilford Woodruff from 1885 until 1892, June 2006. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 33. Wilford and Emma Smith Woodruff, date unknown, ca. 1897, Fox and Symons. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Fig. 33. Wilford and Emma Smith Woodruff, date unknown, ca. 1897, Fox and Symons. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Fig. 34. The Woodruff Villa, main home of Wilford Woodruff from 1892 until his death in 1898, June 2006. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 34. The Woodruff Villa, main home of Wilford Woodruff from 1892 until his death in 1898, June 2006. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Fig. 35. Laying the capstone of the Salt Lake Temple, April 6, 1892. Photograph by Charles R. Savage. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Fig. 35. Laying the capstone of the Salt Lake Temple, April 6, 1892. Photograph by Charles R. Savage. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

After issuing the Manifesto, President Woodruff’s hopes and expectations turned first to completing the construction of the Salt Lake Temple, and second, to taking the necessary political steps to ensure that Utah could achieve statehood. Two landmark events occurred in connection with the completion of the Salt Lake Temple. The first was the placement of the capstone on the temple during the April 1892 general conference, essentially marking the completion of the exterior structure of the building. That event, held on Wednesday, April 6, was attended by tens of thousands of Latter-day Saints who assembled on Temple Square (and thousands more in the city streets) to observe the ceremony, presided over by President Woodruff, who triggered the switch of an electric hoist to set the top stone of the center east spire in place (see fig. 36). At the conclusion of the ceremony, Elder Francis M. Lyman of the Quorum of the Twelve challenged the Saints to furnish the money necessary to complete the temple so that it could be dedicated one year from that time. That goal was realized. Beginning April 6, 1893, precisely forty years since the dedication of the cornerstones for the foundation were laid, the Salt Lake Temple was formally dedicated by President Woodruff in the morning session of a solemn assembly held in the upper assembly hall, attended by three thousand people. President Woodruff recorded, “The spirit & Power of God rested upon. . . . The Hearts of the People were Melted and many thing[s] wer unfolded to us” (see fig. 37).[66]

Fig. 36. Wilford Woodruff on the occasion of the dedication of the Salt Lake Temple, April 6, 1893. Photograph by Sainsbury and Johnson, courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

Fig. 36. Wilford Woodruff on the occasion of the dedication of the Salt Lake Temple, April 6, 1893. Photograph by Sainsbury and Johnson, courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

Throughout his life, President Woodruff maintained an active lifestyle. Hard manual work invigorated him and gave him exercise. His heavy administrative duties, particularly when he served as President, included presiding over the normal day-to-day meetings of the First Presidency and the Twelve and other Church auxiliaries, speaking at stake and auxiliary conferences, dedicating buildings, attending board meetings, hosting dignitaries, signing thousands of recommends, negotiating the sale and purchase of Church properties and business, writing letters, conducting interviews and calling individuals to leadership positions, representing the Church at civic and government functions, and participating in social events. However, despite his numerous responsibilities, he seemed to find time for his favorite pastime, fishing, a sport he enjoyed throughout his entire life. His journal contains hundreds of entries noting his fishing exploits and activities.[67] After he became Church President, time and opportunities for fishing and other outdoor activities diminished significantly. To ensure that he would still be able to enjoy his favorite pastime, in November 1887 he had a pond dug in the northeast corner of his farm property where he could stock his own year-round supply of fish.[68]

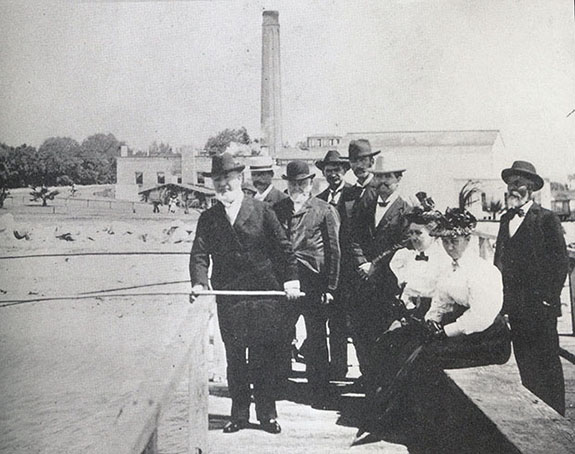

During his later years President Woodruff’s suffered from frequent medical maladies and periods of ill health, mainly abdominal ailments. In addition, age and work-related stress caused by his heavy ecclesiastical responsibilities compounded the problem. Recognizing that an occasional rest from his duties and a milder climate and lower altitude could perhaps offer some relief, between 1889 and his death nine years later, the Mormon leader went on seven excursions to the Pacific Coast. In April 1889, he spent time in Oakland and San Francisco, and later that fall he enjoyed the sights and natural scenery of British Columbia. He spent time in the Bay Area again in 1890 and 1891. To escape the heat of Utah’s summers, in July 1895 he and his counselors and a few family members went by steamer to the southeastern Alaskan coast, where they viewed icebergs, glaciers, waterfalls, rugged cliffs, sea otters, playful porpoises, and spouting whales. They even did some fishing off the side of the steamer anchored just offshore. But Mother Nature was not kind to President Woodruff on this occasion. “We flung out our hooks and lines,” he wrote. “One of the girls caught a halibut, and one of the boys a shark, weighing 150 pounds. I had two or three bites, but caught nothing.”[69] Although his fishing proved unsuccessful, the spectacular scenery renewed his body and spirit (see fig. 38).[70]

Fig. 37. Wilford Woodruff (sitting), Joseph F. Smith (left), George Q. Cannon (center), and Gustave Narth, first mate of the steamer (right), on board the Willapa, July 1895. Courtesy of Alaska and Polar Regions Archives, Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

Fig. 37. Wilford Woodruff (sitting), Joseph F. Smith (left), George Q. Cannon (center), and Gustave Narth, first mate of the steamer (right), on board the Willapa, July 1895. Courtesy of Alaska and Polar Regions Archives, Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

Fig. 38. George Q. Cannon (left) and Wilford Woodruff (behind Cannon), and their company fishing on the Hotel del Coronado pier in San Diego Bay, August 29, 1896. Photograph by S. P. Tressler, courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Fig. 38. George Q. Cannon (left) and Wilford Woodruff (behind Cannon), and their company fishing on the Hotel del Coronado pier in San Diego Bay, August 29, 1896. Photograph by S. P. Tressler, courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

In August and September of 1896, President Woodruff, George Q. Cannon, and several family members spent a month traveling the Pacific Coast from Portland, Oregon, to San Diego, California, with a side trip to Catalina Island. At San Diego, the party checked into the famous Hotel del Coronado, situated in the heart of San Diego Bay, where they spent three full days. On August 29, President Woodruff did some fishing from the hotel’s pier. “We went out on the pier. Got a fish pole and line. Caught a small Stinger fish,” he wrote.[71] A San Diego photographer captured photographs of the Church leader and the group (see fig. 39). Two days later, President Woodruff experienced the deep-sea fishing adventure of a lifetime eight miles off the southern California coast. The experience far eclipsed the stream and pond fishing he was used to:

The Captain tied 5 lines to the stern of the steamer and gave me the charge of them. These lines were for trolling for fish. They were about 200 feet long. The hooks were without beards and fastened with fine wire onto a white bone. We did not use any bait at all. The fish seeing the white bone grab it. It was the most interesting fishing I ever had in my life. We fished about two hours and caught some 600 lbs of fish. They were spanish mackerel, yellow tails and barracuda. I caught the largest. . . .

They kept us very busy for a while. Emma caught quite a number and helped me to haul in mine. The Barracuda fish that we caught would measure near three feet in length. It was the most exciting hook fishing I ever was in.[72]

In September the following year (1897), President Woodruff took another trip, this one lasting sixteen days, to northern California and Oregon, returning in time to preside over the Church’s October general conference.

Death and Burial

On August 13, 1898, Wilford Woodruff boarded the westbound Union Pacific train for what would be his final trip to California; it was during this excursion that he passed away. Arriving in San Francisco, his party boarded at the home of Isaac Trumbo, a prominent California businessman who had been born in Utah Territory but was not a Mormon. He was well connected to Latter-day Saint leaders and Utah politicians, having invested in Utah’s mining industry and lobbied national Republican Party leaders in helping Utah secure statehood.