To Confess or Not to Confess (1903–4)

Roger P. Minert, Against the Wall: Johann Huber and the First Mormons in Austria (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 51–81.

If Johann Huber was fatigued after the trials of 1902, he could hardly have been surprised that the new year brought even more frequent tribulation. He would soon come under fire from the Rottenbach Catholic Church, the Rottenbach School, the Rottenbach Town Council, the Ried County Office, the Upper Austria Provincial Office in Linz, and several courts. And Huber was determined to survive the relentless onslaught.

The action that year began with fellow Latter-day Saint Johann Haslinger. He, too, had again become a father and was also instructed to have his daughter baptized in the Catholic Church. His refusal resulted in a dispute that lasted for three weeks. Because his wife had yet to withdraw from the Catholic Church, he too lost the battle and conceded to the baptism of his daughter by Pastor Schachinger on January 21.[1]

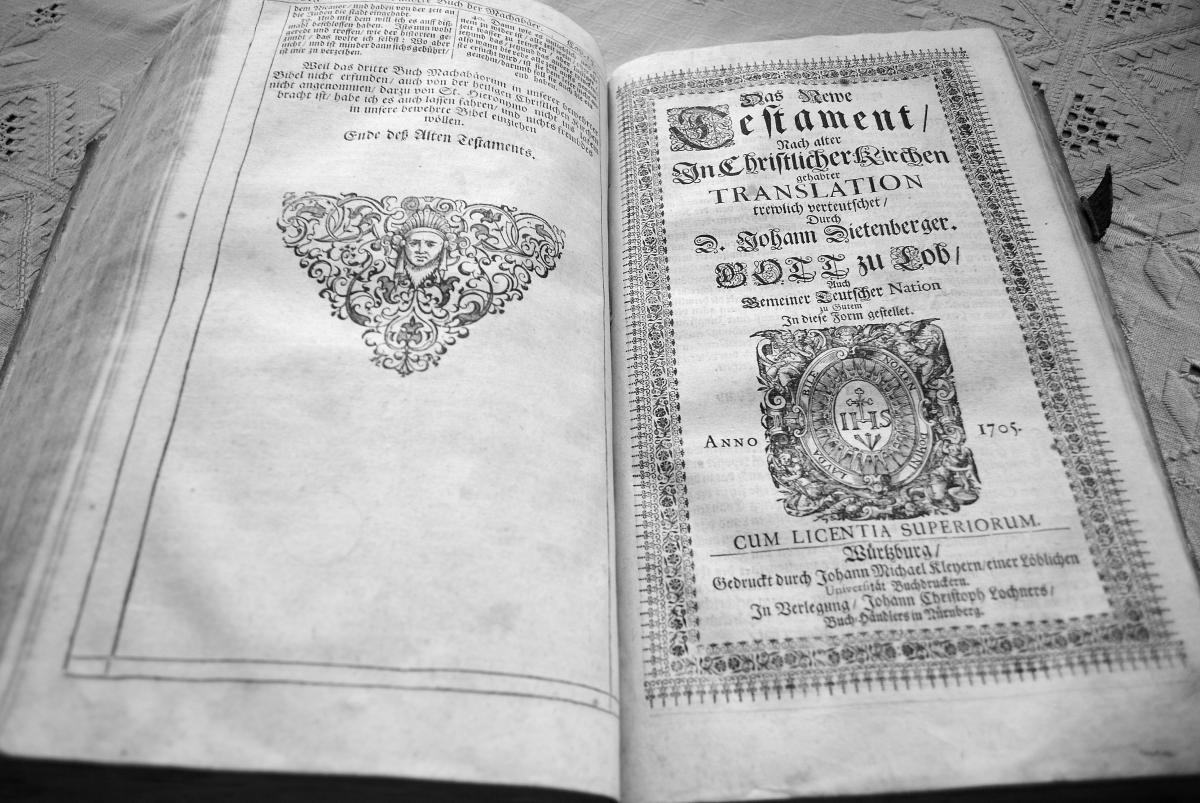

Johann Huber knew this 1705 Catholic Bible very well and quoted liberally from it in his letters to accusers. Photograph by Roger P. Minert. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

Johann Huber knew this 1705 Catholic Bible very well and quoted liberally from it in his letters to accusers. Photograph by Roger P. Minert. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

On February 18, 1903, Schachinger initiated the new year’s first attack on Johann Huber. The pastor wrote to the Ried County Office, reminding officials that Huber had refused to send his son Johann to confession the previous year:

Once again he’s not allowing his son to attend confession in church which is proved via a nasty letter he wrote to Schoolmaster Binna; the boy himself admits as much to the pastor. The boy has often told the pastor that he’s attended the early Sunday mass on occasion, but the other children always deny that. He isn’t learning anything at all in the catechism. Your humble servant, the undersigned pastor, thus requests that on the basis of interfaith laws some definitive action be taken against this Mormon, so that the children who were baptized in the Catholic Church can be raised as Catholics and not as Mormons. [Huber] doesn’t respond to reminders but only respects the police. Should it not be possible to raise the children in the Catholic faith, the undersigned requests that the children be placed in a Catholic home, such as that of the children’s godparents, Josef Vornberger, a farmer in house no. 2 in Oberstötten in this parish. The mother hardly dares to oppose her Mormon husband who often breaks out in rages. Therefore I again ask for decisive action, because nothing else will have any effect and the spiritual welfare of the children is at stake.[2]

The county office responded to the complaint by inquiring of the school whether young Johann Huber was still Catholic.[3] Principal Karl Binna replied that the boy was still a Catholic, then launched a bellicose attack of his own on Huber as a parent: “I ask that the county school board take these [three Huber] children into protective custody and thereby put a stop to the actions of this fanatical Mormon.”[4] He then listed four reasons for this suggestion; the third reads, “It can be anticipated that the parent of these pupils will be causing a lot of trouble for the local clergy, the school officials, and the local school board. The father has informed me in person that he won’t accept any instructions regarding religion and that he wants us to shut up.”[5] Binna’s letter ended with a request that the county office protect him from Huber’s “nasty letters.”[6]

Johann Huber’s Children under Fire

The suggestion that Huber’s school-aged children be removed from his custody was radical and could only anger the father. Preferring to take action carefully, the county office first requested details regarding young Johann’s absence from confession; Binna provided the requested information a week later. In the meantime, Huber had learned of the process and wrote a scathing letter to the principal. Two of the three pages of the letter have survived and provide ample evidence of Huber’s displeasure:

You threatened to give my son grades of 4–5 [D–F] if he didn’t attend confession and to report him to the county school board. Such actions reflect the powers of darkness. Is it your job to deal with religion and force the pupils to do things not taught in the Bible? You do a dishonor to your profession.[7]

Binna then approached the Rottenbach School Board for help, and they requested several reports regarding young Johann’s attendance at school and at the school confession sessions in the local church. Those reports were forwarded to the county school board in Ried, along with a statement that Johann Huber had been warned about the consequences of preventing his son from going to confession. A ruffled Huber refused to sign delivery confirmation cards for these reports.[8]

Principal Binna was partisan in his initial attacks on Huber, but seems to have lost interest in the conflict in subsequent letters.

Principal Binna was partisan in his initial attacks on Huber, but seems to have lost interest in the conflict in subsequent letters.

On April 1, 1903, the Rottenbach School Board informed Huber that he would be fined if his son did not attend confession (he had been absent in both January and February). Of course, Huber refused to pay the fine, and notices went back and forth for the next five months.

In one of the documents that has not been preserved, either Binna or the local board petitioned the Haag District Court to declare Johann Huber insane and thus incapable of exercising his parental rights. The court ruled that Huber was not insane, whereupon the plaintiff appealed the case to the Wels Appellate Court, which issued a ruling on May 4. This ruling contained two basic points: first, that the Hubers were ordered to raise their children in the Catholic faith; second, that should they fail to do so, penalties would be imposed.[9]

The Wels ruling may appear to have been in error, because imperial law stipulated that the son could be raised in the father’s religion; Johann Huber had officially withdrawn from the Catholic Church and therefore was not required to raise his son Catholic. But The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints had no legal status in Austria at the time, so the son was to be raised in the mother’s faith. He therefore could not be exempted from attendance at school confession sessions, as was the case with his two younger sisters, Theresia and Maria.

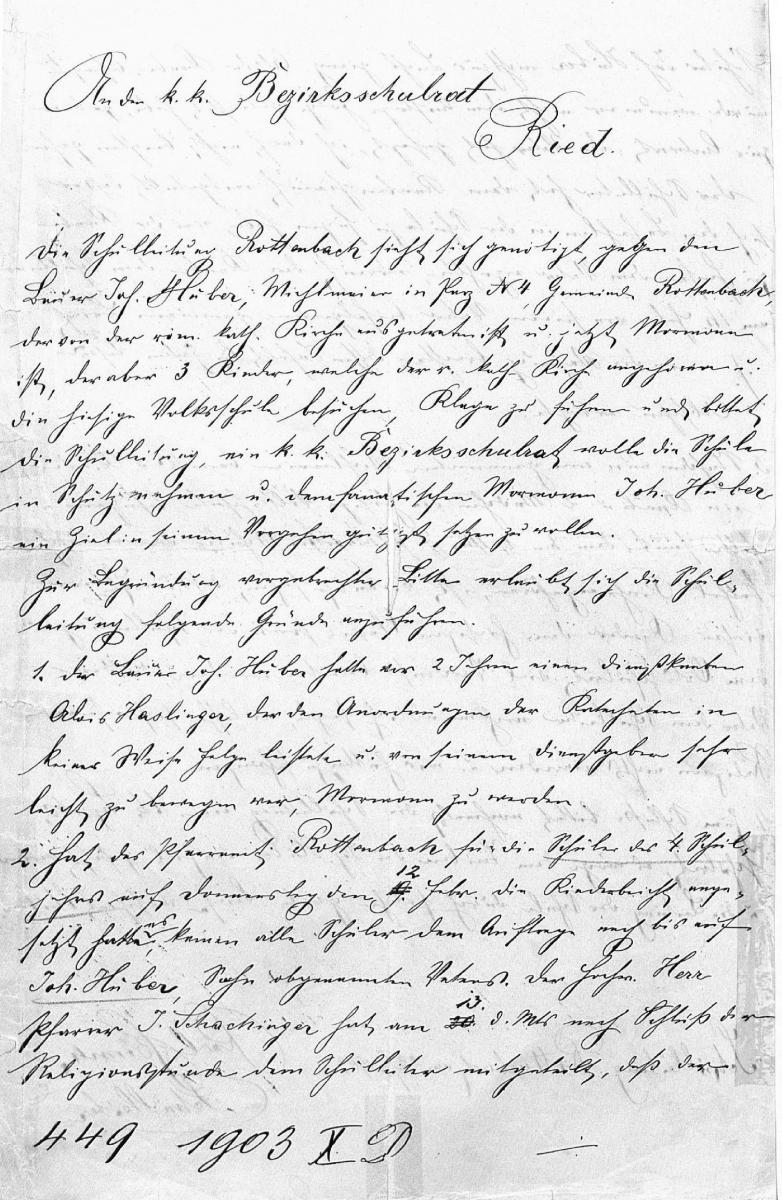

The first page of the county letter dated May 12, 1903, directed to "Mr. Michlmayr Johann Huber." Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

The first page of the county letter dated May 12, 1903, directed to "Mr. Michlmayr Johann Huber." Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

The case was concluded after being returned by the court in Wels to the court in Haag. The latter repeated the injunction that the children be sent to confession and added the threat of cancellation of parental rights.[10] Pastor Schachinger must have been informed of these rulings, because he pressed the issue anew by reporting to the county on May 12 (the date of the last Haag ruling) that none of the Huber children had attended confession recently.[11] The town office of Haag then sent agents to post a notice on the front door of the Huber home regarding the court ruling, then reported their actions to the local school board. The local school board informed the Ried County School Board of the action taken, and the Ried County Office summarized for Johann Huber the court’s instructions and threat of punitive action. This communication represents the most drastic action taken against Johann Huber to date:

In accordance with the notice of the Imperial and Royal District Court at Haag dated May 12, 1903, you were ordered to raise your children in the Roman Catholic religion. For this purpose you are to follow all instructions given by authorities of the school and the church, specifically regarding your children’s required participation in confession. Should you refuse to fulfill your duty to raise your legitimate children in the Roman Catholic faith, an order will be issued to cancel your paternal rights and to designate a guardian for your minor children such that their religious education can be effected. By reminding you again of this court order, it should be noted that if you continue to neglect your duty and we receive a report of such conduct, we shall issue an order without delay to have your paternal rights cancelled.[12]

For the Huber family, this was a dire threat. In typical Austrian bureaucratic fashion, the county commissioner wrote the same day to Pastor Schachinger and the Rottenbach School Board to inform them of the instructions given Johann Huber. For all practical purposes, Johann Huber would have been justified in characterizing the situation as “all against one.”

The confessional in St. Peter's Church in Rottenbach. Photograph by Roger P. Minert.

The confessional in St. Peter's Church in Rottenbach. Photograph by Roger P. Minert.

Pastor Schachinger wrote the following in his letter to the bishop in May 1903:

Finally the county office has responded to my repeated appeals and has given an ultimatum to the Mormon that he either raise his children in the Catholic faith or a guardian will be appointed. The Mormon and his wife have promised to do the former, and it appears that the wife is serious. She showed me a confession certificate from Ried and is attending church services again.[13]

Nevertheless, rather than give in, Huber wrote another appeal the very next day to the county office. His letter dated May 15 serves as a classic example of his righteous indignation; while defending his actions and refuting claims of local agencies, he delivered a long diatribe on religious doctrines, such as confession and indulgences, and reminded the reader of some of the historical misdeeds of Catholic priests. In his unabashed style, he repeated the offer to pay 1,000 florins to anybody who could show him in the New Testament where Christ or the Apostles taught the practice of confession.[14]

In his letters, Huber insisted that the Catholic Church didn’t introduce confession until AD 1215. One wonders where he found this date or where he learned of the many passages of scripture that he used to undergird his arguments on Christian doctrine. Had he studied the Bible all of his life? Did Ganglmayer and other LDS missionaries provide the references he quoted? Or did this Upper Austrian farmer commence an intense study of the Bible and church history since his conversion to Mormonism? Whatever the answer, Huber displayed fierce dedication to Mormonism in his constant defense against the Catholic Church.

During the spring of 1903, Josef Schachinger complained again to church officials in Linz about his health problems. He had succeeded in finding a physician capable of attesting to his maladies, but was unhappy that the physician had “understated” the pain. In a letter dated April 25, Schachinger asked to be granted retired status, naming one town where he would like to serve and another where the physical demands would be too much. He must have felt a lack of support from Linz, however, making reference to a recent visit of the bishop and quoting the bishop as saying, “Now that you’re here, you’ll be staying here.”[15] The bishop, wanting to avoid talk that he was not concerned with Schachinger’s personal and professional trials, did mention in a letter dated May 12, “We are pleased with the actions you have taken against the Mormon there.”[16] Schachinger’s physical constitution was almost certainly a contributing factor when he penned so many letters in an impatient and intolerant tone.

The Rottenbach Elementary School (center) on a postcard printed in about 1919.

The Rottenbach Elementary School (center) on a postcard printed in about 1919.

The effort on the part of Schachinger and Principal Binna to paint Huber as insane continued when one of them (or perhaps the Rottenbach School Board) took the question anew to the Wels Appellate Court in June 1903. The plaintiffs lost when the court ordered a cease to the investigations into the sanity of Johann Huber, but were victorious when the court reiterated the instruction that the Hubers raise their children in the Catholic faith.[17] However, somehow the matter of Huber’s mental condition became the subject of yet another ruling handed down by the Haag District Court on July 14, 1903. It certainly must have come as a relief to Huber that the court cited witnesses (Huber’s neighbors) who insisted that he was quite capable of managing his own affairs.[18] What might have been an excellent opportunity for those neighbors to do the family and Huber significant damage turned out to be a vote of confidence in his favor. Those witness statements must have rankled the men who continued their campaign against the Mormons in Rottenbach.

The Huber granary where the first LDS worship services in Austria were held. Photograph by Roger P. Minert.

The Huber granary where the first LDS worship services in Austria were held. Photograph by Roger P. Minert.

Church Confession or School Confession?

One week later, the Rottenbach School Board levied a fine of ten crowns against Johann Huber, because his son, the young Johann, had not attended Catholic confession during school in January. The same fine was levied for the same alleged offense in February. Huber staunchly refused to pay those fines, so the school board called upon the Haag Guardianship Court for help in enforcing the action. The court fined Huber fifty crowns and once again threatened to divest him of his parental rights.[19]

Huber’s response to this latest action was a detailed letter written on August 24. He first indicated that he would not pay the fine until his latest appeals to various courts had run their course. Then he mentioned what is not found in other documents, namely that action had already been taken to remove the children from his home: “I was told by Johann Weidenholzer, whom you appointed as guardian over my children, that he had refused to accept the appointment as of August 27 despite the threats expressed to him. First you want to punish me, then to take away my right to act as the father of my children, even if that means the ruin of my household.”[20]

Huber’s next contention in the letter was actually in error: he insisted that the 1868 law regarding religions in Austria-Hungary had an Article 12 that allowed parents of different religions to choose which religion would dictate the children’s upbringing. Article 12 of that law does not deal in any way with that topic, and this thus represents a rare mistake on Huber’s part.

The letter ended with another challenge and serves as additional evidence of the resolve of this farmer: “I request a formal hearing. I would like to face my accuser and a judge can easily determine after hearing the opinions of both parties just who is speaking the truth.”[21]

The distance from Rottenbach to Haag is two miles, and the distance to Ried ten miles. Johann Huber made frequent trips to the market town of Haag for farm business; therefore, an appearance in court there was no hardship. However, a trip to Ried would have taken several hours and seriously interrupted the work on the Michlmayr farm. To get to the county seat, Huber most likely walked five miles north and west to the railroad station at Pram; from there, the ten-mile ride to Ried would have taken less than twenty minutes. Fortunately, it appears that he was never required to travel to Linz—a distance of twenty-seven miles. Any costs of traveling to any of these places in connection with these legal procedures would have added to the investment he had decided to make in defending his new faith.

The Haag District Court denied Huber’s request for a formal hearing with wording that came dangerously close to breaking up the Huber family:

Thus there is sufficient evidence to rule that [Huber] is disregarding the court order of May 12, 1903 and that he is offering determined opposition to said ruling. If the Guardians Court has yet to carry out the previous threat of relieving him of his parental rights, because it is expecting that the fine will be paid, then this justifies the court action based on paragraph 19 of the imperial decree of August 9, 1854 (no. 208 of the RGB). Thus the appeal must be denied.[22]

As the conflict dragged on, Huber wrote another long letter to the Wels District Court insisting that his previous letter to the Haag District Court had never been forwarded to Wels, “otherwise the threatened fine of 50 Crowns would have been declared null and void.”[23] Further comments mention a concept that never appears in any of the more than seven hundred pages of documents collected for this study: emigration. “I have demanded that the church and school authorities prove to me that confession was introduced and practiced by Christ and his apostles. They can’t produce that proof and desire to continue their attacks until such time that I can no longer exist here and must emigrate.”[24] Johann Huber may have used the idea of emigration to make him appear to be a martyr, but the concept does not occur in any other of his numerous writings. He apparently never seriously considered leaving his home.

Throughout September and October 1903, the school and the local school board continued to report to the county office that the Huber children were not attending school confession. Two more fines of ten crowns each were imposed. Huber wrote to the provincial school board in Linz, carefully explaining that he had been fined for the wrong offense: whereas young Johann had indeed missed school confession services, he had not been absent from the religion class held in school by Pastor Schachinger. Huber knew that he had no chance to resist regular religious instruction, but he demanded again that somebody prove to him that confession was taught by Jesus Christ or his Apostles and could thus be required of school-aged children. Again he refused to pay the fifty-crown fine.[25]

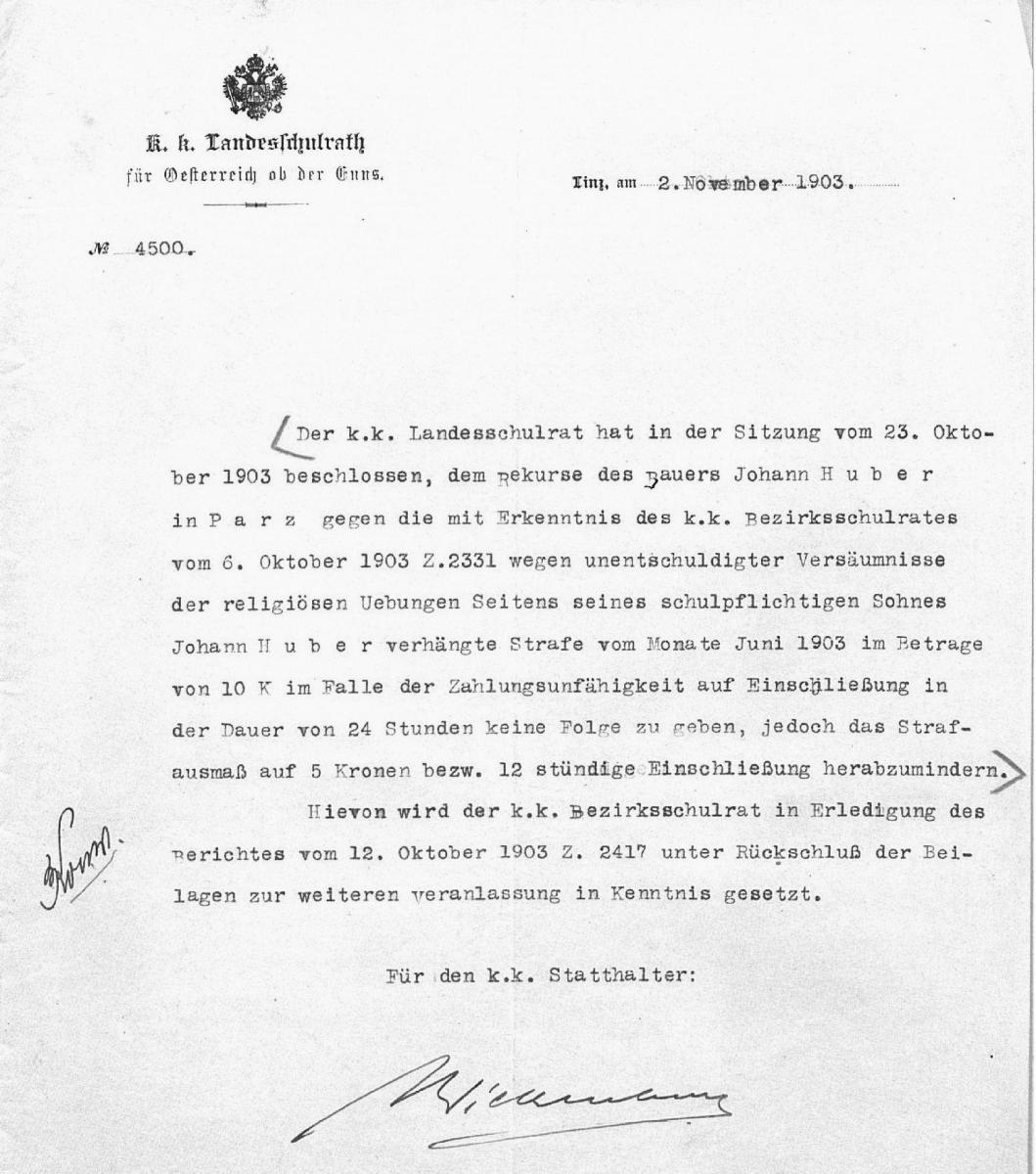

The November 2, 1903, letter from the Ried County Office is a rare typed document of the era.

The November 2, 1903, letter from the Ried County Office is a rare typed document of the era.

Following the process quite carefully, Pastor Schachinger was discouraged about the prospect of removing the Huber children from their home; he expressed this to the diocesan office in Linz: “There’s little chance of finding a man willing to serve as guardian and [Huber] laughs at the idea.”[26]

Amid the hail of documents coursing among various offices in Upper Austria in the fall of 1903 is a curious one issued by the Ried County Office. It stated that Johann Huber had declared himself financially incapable of paying a fine of ten crowns, thus the provincial school board in Linz recommended that the fine be reduced to five crowns. The county office agreed, but only if Huber would make the payment within five days. The officials must have known that the Michlmayr farm was large and prosperous but were growing tired of the furor around Huber and hoped his attackers would relent once he paid a fine.[27] If the officials’ theory was sound, the practice turned out to be quite the opposite. Huber again refused to pay and appealed for a cancellation of the fine. In another typically long diatribe, he quoted the imperial laws regarding religion as his defense.[28]

About this time, the Catholic Church offended Huber again by attempting to draw a local girl away from employment at the Michlmayr farm. Huber complained of the incident in a letter to the county office on November 16, 1903:

I ask the Imperial and Royal commissioner if it is right for the vicar to confront my servant girl in school on November 12 and demand that she quit working for me. Schachinger had her father called in on November 15 to take his daughter Maria Weber out of my home. On November 18, Mr. Binna, the school principal, told her that she should look for other employment. . . . (Is this the principal’s duty?) Aren’t these examples of breaking the law? They want to report her and have her punished for not quitting her job. What about the laws regarding domestic servants? Don’t they have to break a law one way or the other? This is definitely a kind of insanity.[29]

The Haag District Court chose on November 25 to override the action taken by the Haag County Court earlier that month, namely the ruling that sufficient property belonging to Johann Huber be sold to enable the county to collect the fifty-crowns fine.[30] At the same time, other agencies were planning the utilization of the fines to be collected from Huber: the county office informed the county tax office that the monies collected would be forwarded to the school fund.[31] Thus the Rottenbach School and the local school board would be padding their own coffers by pursuing punitive action against the Mormons at the Huber farm.

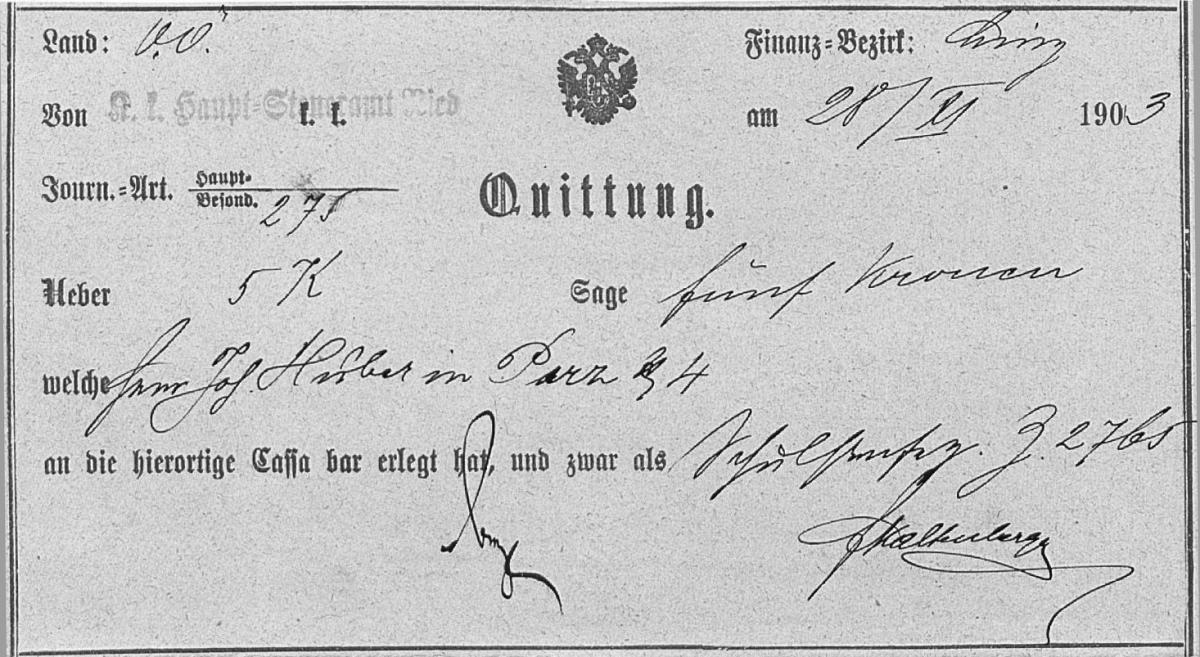

After seemingly endless debate, Huber paid the reduced fine of five crowns on November 28. The next day, the Linz Provincial School Board rejected his latest appeal.

After seemingly endless debate, Huber paid the reduced fine of five crowns on November 28. The next day, the Linz Provincial School Board rejected his latest appeal.

Theresia Huber Withdraws from the Catholic Church

Precisely when Huber’s wife, Theresia, decided to withdraw from the Catholic Church cannot be determined, but she properly communicated this decision to the Ried County Office on November 30, 1903.[32] That office then inquired of the Rottenbach Catholic Parish whether the Hubers were raising their children according to Catholic practice.[33]

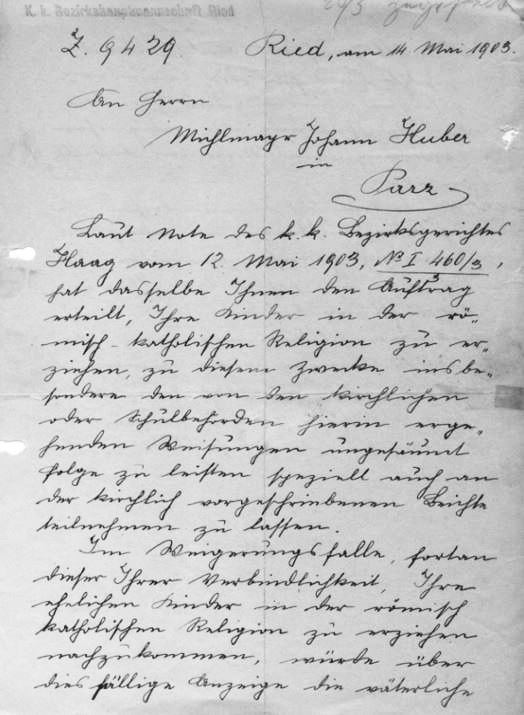

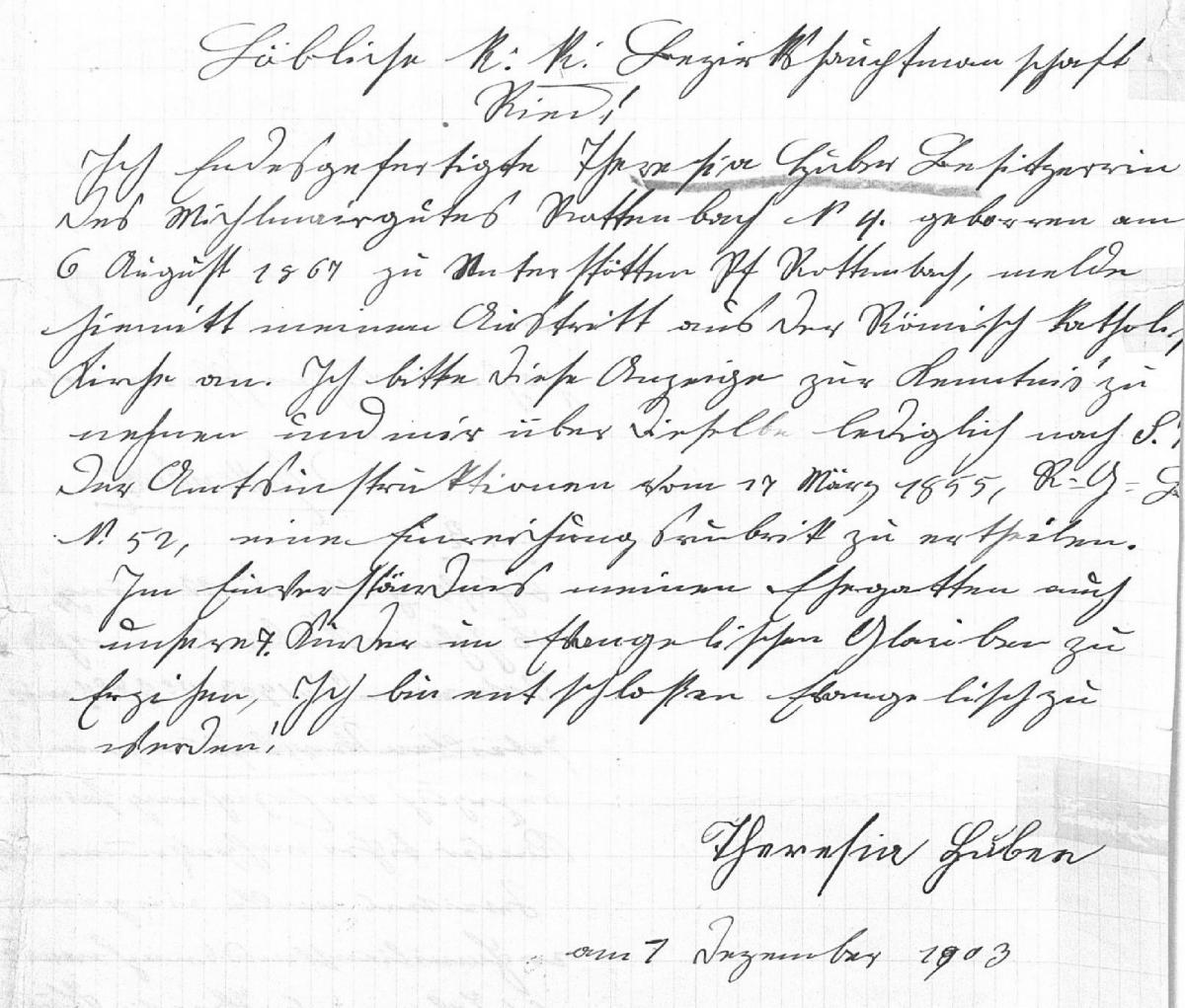

Pastor Schachinger's charge that this declaration was not written by Theresia Huber was justified; this is her husband's handwriting.

Pastor Schachinger's charge that this declaration was not written by Theresia Huber was justified; this is her husband's handwriting.

For some reason, Theresia’s first notice must have been deficient, so she submitted another one on December 7. This time she included the names of her children. Perhaps she had been reminded in the interim that the 1868 Austrian constitution required that the children’s religious affiliation automatically be that of the mother if the father embraced another faith not recognized by the state. Here is the text of her declaration:

I, the undersigned, Theresia Huber, [co-]owner of the Michlmayr farm in Rottenbach Parz no. 4, born on August, 6, 1867 in Unterstätten in the Rottenbach Parish, hereby declare my intention to withdraw from the Roman Catholic Church. I request that this declaration be accepted and that a certificate be issued in accordance with the Imperial Law of March 7, 1855 (RG no. 52). My husband is in agreement that our seven children should be raised in the Protestant faith. It is my intention to be Protestant.[34]

This declaration raises the question of whether Theresia truly planned to live and worship as a Protestant, when the closest parish of that faith was in Wels—sixteen miles to the east. Or was this merely a tactic to leave the Catholic Church in order to protect the family from further attacks in school, when her true intention was to join her husband as an adherent to the LDS faith? Given the documents available for study, this question must remain rhetorical.

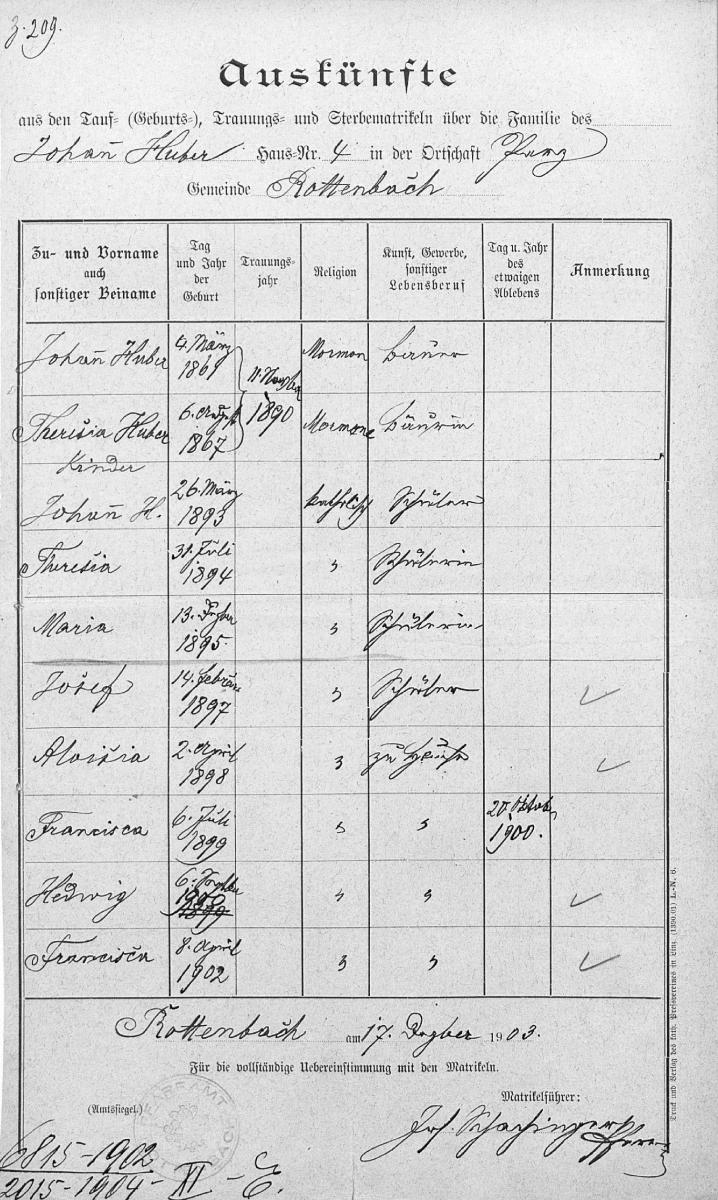

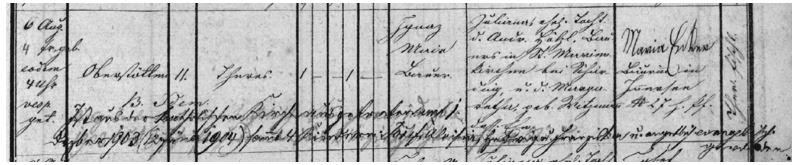

The Huber family data compiled by Schachinger for the county office in December 1903.

The Huber family data compiled by Schachinger for the county office in December 1903.

Theresia’s announcement immediately drew fire from Pastor Schachinger. He wrote a full-page letter to the county with four specific charges: (1) Theresia Huber did not write or even sign her declaration; (2) Theresia had no intention of becoming Protestant, but rather a Mormon, and had been encouraged to do so two weeks earlier when a “Mormon apostle” came from Munich for a visit; (3) young Johann Huber only attended confession once and then only to keep the authorities at bay, and the Huber children were learning nothing at all in catechism but were carefully schooled in Mormonism at home; and (4) Huber conducted a funeral for a deceased Mormon friend but had no right to do so because the sect is not recognized in Austria.[35]

Days later, on December 11, Theresia was instructed to appear at the county office. Was it the commissioner’s intent to learn whether she had a genuine interest in becoming Protestant or to become a Latter-day Saint after all? That cannot be determined because the documents suggest that she never actually made an appearance in Ried. On December 14 a physician in Haag issued a statement that Theresia was suffering from “an infection of the connective tissue (in her hand)” and could not travel to Ried. This was either a convenient and timely excuse, or the Hubers were playing this cat-and-mouse game to the hilt. Indeed, they once again eluded the officials, and their machinations are almost comical.

The next day, Theresia wrote to the county to inform them that she would be represented in this matter by her husband (her legal spokesman).[36] He traveled to Ried and informed the officials that his wife wanted to transfer to the Protestant Church “in order to prevent any more harassment of their children.”[37] It was not until February 2, 1904, that Theresia Huber filed a valid request to transfer to the Lutheran Church. That request was approved and as required by law, the county mailed the Catholic priest a similar notice on February 5. Schachinger wrote to Ried the next day to protest what he believed to be a dangerous decision.[38] By now, his prime argument and concern was that the Huber children would be raised in the Mormon faith.

The author examines the trap door reportedly used by the Mormons to flee the granary if intruders were seen approaching the farm house when a meeting was in session. Photograph by Jeanne Minert.

The author examines the trap door reportedly used by the Mormons to flee the granary if intruders were seen approaching the farm house when a meeting was in session. Photograph by Jeanne Minert.

In an evident attempt to stop the county office from allowing Theresia Huber and her children to withdraw from the Catholic Church, Pastor Schachinger corresponded with the county two days before Christmas. Five more charges were made against the Huber family: (1) the second application for withdrawal from the church was written by Johann Huber and his wife’s signature is not genuine; (2) the Huber children were not being harassed, counter to what Huber had claimed; (3) Theresia would not be going to Wels to church, nor would the Protestant pastor from Wels travel to the Huber farm; (4) the Hubers were not at all raising their children in the Catholic faith; and (5) the children should be placed in Catholic homes or in an orphanage.[39]

Pastor Schachinger must have been pleased to hear of the ruling handed down by the county office on December 28: the clerk noted that Theresia’s request to withdraw from the Catholic Church was denied because “she had not informed them precisely which church she wished to join.”[40] She was also reminded that the law prohibited her from changing the religious affiliation of any of her children between the ages of seven and fourteen years.[41] The last paragraph was especially distressing, because the court in Haag was asked to report what measures had been taken in divesting Johann Huber of his parental rights.

The Rottenbach Catholic Parish baptism record for Theresia Mair in 1867 was appended (in dark ink) with a statement regaring her withdrawl from the church, i.e., that she had become "reportedly Lutheran."

The Rottenbach Catholic Parish baptism record for Theresia Mair in 1867 was appended (in dark ink) with a statement regaring her withdrawl from the church, i.e., that she had become "reportedly Lutheran."

When Theresia Huber signed a postal card indicating that she had received the documents from the county office, she and her husband likely were grateful and relieved for having survived the year 1903 with their family intact, but they must have wondered how long this controversy could last; none of their antagonists had slackened in their efforts to combat the Latter-day Saints and anybody associated with Johann Huber.

Indeed, on December 22, 1903, the local newspaper published yet another warning against the Mormons in the region. The article bore the title “The Spread of Mormonism” and was more than 600 words in length. Written by a well-informed local resident, the article insisted that the number of “fanatical Mormons” was increasing: “This Johann Huber, who holds the office of Mormon elder [sic], also has seven children whom he wants to and will mislead to Mormonism if the proper steps aren’t taken to stop those parents.”[42] The writer continued in a passionate tenor:

Is this what we call education, when the parents tell their children at home that the Catholic priest is teaching them falsehoods, humbug? How then are the children to know their way in this most important aspect, religion? Don’t they have to become Mormons as well? It is high time that Michlmayr lose his paternal rights and that the children be sent to other homes to be raised correctly, or else Mormonism will spread all over Austria.[43]

This text bears all of the markings of Pastor Josef Schachinger, but no author’s name was printed in connection with the article. Who else could have been so consumed with the danger of Mormonism? So far, other than the Huber family, not one native member of the Rottenbach Catholic Parish had fled the mother church to join the new religion—after more than four years of Mormon activity in the town. The newspaper article ended with this impassioned plea: “It makes one tremble to consider such happenings. May this sect disappear very soon and may these sadly misled people be brought back to the true path.”[44]

Mormons in Nearby Haag am Hausruck

About this time, evidence of the missionary efforts of Michlmayr Johann Huber surfaced just two miles away. Mormons in the market town of Haag am Hausruck were causing trouble for Pastor Michael Dobler of the Catholic parish there. Johann Haslinger (the first man baptized in Austria) had a son, Alois, who had worked on the Michlmayr farm. The teenager had become seriously ill in October 1903, and Pastor Dobler reported his concerns about Alois’s condition to the bishop in Linz. Having already described Johann Haslinger as mentally weak, Dobler attributed the same flaw to the boy.[45]

Young Alois died on October 9, and his funeral became the newest bone of contention between the faiths. Schachinger reported the event to his superiors in Linz, because the boy died in the Huber home and thus in the Rottenbach parish:

The pastor sought out the [Huber] grandmother who showed him the room where the sick boy lay. But the door was locked. After he had knocked many times, the farmer’s wife [Theresia Huber] opened the door and yelled, “What did you come here for?!” The pastor answered, “To ask the boy if he wants to return to the Catholic Church.” When the sick boy heard the question, he shook his head energetically. The farmer’s wife said, “Now just get out of here!” The pastor said, “We’re all sinners so we all have to have our judgment day.” “Well, I’ll withdraw from the church and not have any church at all.” Pastor: “That’s very sad. Apostasy is a very serious sin. It’s your duty to raise your children as Catholics and to send them to church for confession, or I’ll have to report you.” “Just get out of here!” Then one of the Mormon servant boys chased after the pastor and said, “So you railed against us again on Sunday.” Pastor: “I just said that Mormonism is only 70 years old so it can’t be the Church of Christ.” Servant: “Get thee hence, Satan!”[46]

Schachinger was quite upset about the altercation (and the fact that Alois had died a Mormon) and concluded his letter with these words: “The pastor asks to be forgiven for this poor handwriting. Under such circumstances his hand starts to shake.”[47] The bishop in Linz responded by thanking Schachinger for his attempts to save the young man’s soul.[48]

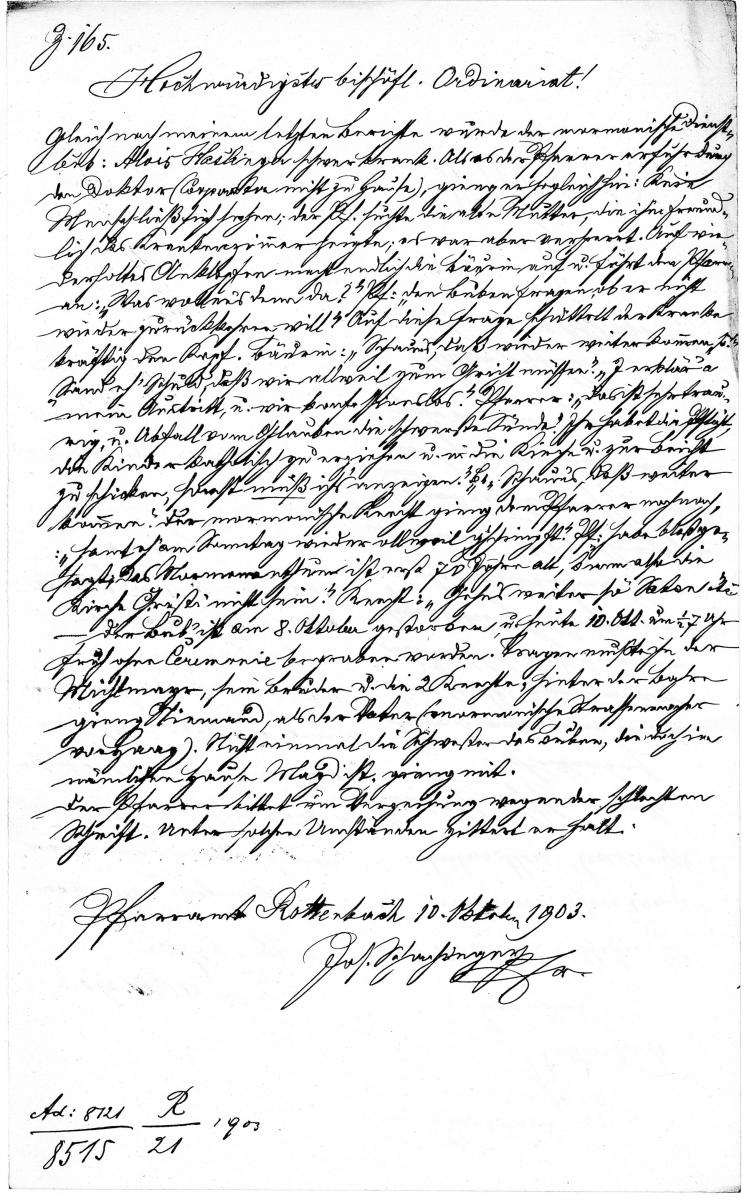

Pastor Schachinger complained in this letter that he was not allowed to tend to a sick parishioner in Huber's home.

Pastor Schachinger complained in this letter that he was not allowed to tend to a sick parishioner in Huber's home.

The Battle against School Confessions Rages On

The year 1904 dawned, and the fight over confession for the Huber children dragged on. The first communication on January 11 brought more bad news from the Haag County Court: “should [Huber] fail to obey the court order as stipulated in the ruling dated August 19, 1903, . . . and again refuse to send his children to church to participate in confession . . . , the court could then mandate new penalties.”[49] The metaphorical blade hovering over this farmer’s neck was the loss of his parental rights and the removal of his children from the home. How could he satisfy the court—in other words, how could he raise his children officially in the Catholic faith while educating them in Mormon doctrine?

The county government in Ried issued an order the very next day directing the court in Haag to appoint a guardian for the Hubers’ minor children.[50] The court did so, naming one Johann Scheidinger for that purpose. Fortunately, no further action was prescribed.[51] Apparently, Scheidinger was either never asked to fill this role or refused to do so.

From July 1895 to February 1906, the case between Huber and the school was handled by a member of the lower nobility, August Edler von Chavanne, who was the ranking official in the county of Ried.[52] His title was Staathaltereirat [governmental counselor] and his signature “Chavanne” or initials “Ch” are found on nearly one hundred documents emanating from or arriving in the Ried County Office and dealing with Johann Huber. By 1904 this man had apparently become a consummate bureaucrat, restricting the language of his communications to very neutral terms as he dealt with the case of religious renegade, Johann Huber, of Rottenbach. There is no hint in his writing that he took either side in the negotiations that would drag on for the last five years of his tenure.

On March 2, 1904, Chavanne wrote to the Rottenbach Catholic priest to request a description of the religious services held in connection with the school. This request must have been based on the repeated claim by Johann Huber that church services should not be associated with the school. Pastor Schachinger’s response reflects the attitude of his previous communications: “The following religious services are conducted in the Rottenbach School just as they are in other schools,” he wrote.[53] He then provided this list:

1. Prayer before and after class

2. Daily school mass (weather permitting)

3. Regular mass every Sunday and holy day all year long, including during vacations, as stipulated by diocesan edicts

4. Receipt of the holy sacrament of repentance at the altar as required by the bishop

5. Participation in the processions on Corpus Christi Day, Petition Day, and St. Mark’s Day

6. My own instruction for confession and communion after school hours as well as catechism before confirmation as required by the bishop

7. Attendance by pupils in the seventh and eighth grades at Christian instruction on Sunday afternoons; other pupils may attend if possible but are not required to, as stipulated by the bishop.

The list of religious programs and services that schoolchildren were required to attend under Pastor Schachinger was onerous. But what was it precisely that motivated Johann Huber to keep his children from participating in those services? Was he worried that they would be converted to Catholicism? Would there be no time left to teach them Mormon doctrines? Would the children be confused by the conflicting doctrines? Would Schachinger target the children for specific embarrasment and persecution before their peers? Would the children really be punished with bad grades if they missed the services, or was this just a power struggle between the pastor and the Mormon?

Schachinger’s insistence that all Rottenbach children were to attend regular worship services in the Catholic Church went too far from a legal perspective. As a result of the withdrawal of both parents from the Catholic Church, the Huber children were now officially exempt from attending services meant for the general Catholic population in the parish. However, the law did still require that all children enrolled in the public elementary school attend the religion class taught of necessity by the local clergy in the school. Such practices caused no contention at all in towns where everyone was of the same religion. Johann Huber had no argument with this law, but justifiably contested that his children were not bound to participate in any school-related activity conducted in the Catholic parish church. This was the subject of many letters and reports written by Huber, Schachinger, Binna, and officials on the county and provincial levels in March 1904.

For example, in the Rottenbach public school, Principal Binna responded to a request he received from the county school board dated March 11 by stating that he was not aware of any requirement of his pupils to attend church services. On the other hand, he wrote, most of the children were in attendance when the weather was good. His final statement is noteworthy: “For your information, Pastor Schachinger asks [young] Johann Huber every Tuesday afternoon whether he was in church the previous Sunday morning or not.”[54] Binna’s report was the last surviving document produced in the school office until the end of September—nearly seven months later. If there were indeed no others, we might conclude that school officials were satisfied to stay out of this fracas.

Toward the end of March 1904, the county office informed the county school board in Ried and the district court in Wels that Huber was in the right: his children were not required to attend such non-school events as confession in the church.[55] Investing all possible energy in his zealous effort to save the souls of the Huber family members, Pastor Schachinger wrote the following encouraging report to the diocesan office on April 28:

Since the fasting period began, young Johann Huber has been attending worship services regularly on Sundays and holy days. He has also attended confession and communion instruction regularly, though he hasn’t learned very much. The pastor believes that he should admit the boy to communion, because that might have a good effect on him. Maybe the boy will also attend confirmation catechism classes. However, he can hardly find a Catholic man to serve as his godfather. He will probably invite his father’s brother, the cobbler in Au, Haag Parish. That man has yet to declare his withdrawal from the Catholic Church (because his wife won’t allow it and she’s the owner of the property). So the pastor’s question is this: may he accept that man as a godfather? The man has been very ill of late and reportedly promised that if he recovers, he will distance himself from Mormonism.[56]

Despite Schachinger’s dedicated efforts, a heated contest that had begun nearly three years earlier involving many individuals, agencies, and offices had ended in a resounding victory for the Mormons. However, for Johann Huber, the leader of the first group of Latter-day Saints in Austria, more negative confrontations awaited him. Fortunately, the year 1904 had begun in a most positive manner.

Notes

[1] Haag Town Hall to Ried County Office, February 23, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[2] Josef Schachinger to Ried County Office, February 18, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[3] Ried County Office to Rottenbach School, February 19, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried XI E 1903.

[4] Karl Binna to Ried County Office, February 23, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[5] Karl Binna to Ried County Office, February 23, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[6] Karl Binna to Ried County Office, February 23, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[7] Johann Huber to Karl Binna, February 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried XI E 1903. Young Johann Huber later wrote that he was an excellent student in 1899—his first year in school. Johann Huber Jr., autobiography, ca. 1938, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection, Rottenbach, Austria.

[8] Rottenbach School Board to Ried County School Board, March 3, 5, 10, 14, and 16, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried XI E 1903.

[9] Wels District Court Ruling, May 4, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[10] Haag District Court Ruling, May 4, 1903, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[11] Josef Schachinger to Ried County Office, May 12, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[12] Ried County Office to Johann Huber, May 14, 1903, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[13] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, May 21, 1903, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[14] Johann Huber to Ried County Office, May 15, 1903, Wilhelm Hirschmann private collection, Aggsbach Markt, Austria.

[15] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, April 25, 1903, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[16] Linz Diocesan Office to Josef Schachinger, May 12, 1903, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[17] Wels District Court Ruling, June 5, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[18] Haag District Court Ruling, July 13, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[19] Haag Guardianship Court to Johann Huber, August 19, 1903, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[20] Johann Huber to Haag District Court, August 24, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[21] Johann Huber to Haag District Court, August 24, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[22] Haag District Court Ruling, September 12, 1903, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[23] Johann Huber to Wels District Court, September 20, 1903, Wilhelm Hirschmann private collection.

[24] Johann Huber to Wels District Court, September 20, 1903, Wilhelm Hirschmann private collection. The turn of the century was still a period of substantial emigration of Latter-day Saints from Europe to “Zion,” generally understood to mean the Rocky Mountains and specifically Utah. There is every reason to believe that one or more of the missionaries who contacted Johann Huber had mentioned that he might consider emigration as an escape from these apparently incessant persecutions. However, Martin Ganglmayer never discussed emigration when he wrote to encourage Huber to remain strong in the faith. Perhaps Huber maintained the hope that he could eventually weather the storms of persecution and prosecution (indeed defeat the forces of evil arrayed against him) and live the life to which he was born—as the owner of a large and prosperous estate farm in provincial Upper Austria.

[25] Johann Huber to Linz Provincial School Board, October 20, 1903, Wilhelm Hirschmann private collection.

[26] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, September 29, 1903, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[27] Ried County Office to Johann Huber, November 2, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[28] Johann Huber to Ried County School Board, November 9, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried X L 1903, 2646.

[29] Johann Huber to Ried County Office, November 16, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[30] Haag County Court Ruling, November 25, 1903, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[31] Ried County Office to Ried County Tax Office, November 28, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[32] Theresia Huber to Ried County Office, November 30, 1903, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection. Theresia Huber accorded herself the title “female owner of the Michlmayr farm,” reminding the reader that the farm had been her inheritance.

[33] Ried County Office to Rottenbach Catholic Parish, December 3, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[34] Theresia Huber to Ried County Office, December 7, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[35] Josef Schachinger to Ried County Office, December 7, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach. Schachinger sent the requested Huber family data to the county on December 17; all family members had been baptized in the Rottenbach Church, and the parents had married there.

[36] Theresia Huber to Ried County Office, December 15, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach. This statement was also written by Johann Huber.

[37] Ried County Office, Johann Huber Deposition, December 15, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[38] Josef Schachinger to Ried County Office, February 6, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[39] Josef Schachinger to Ried County Office, December 23, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[40] Ried County Office to Theresia Huber and Haag County Court, December 28, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[41] Ried County Office to Theresia Huber and Haag County Court, December 28, 1903, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1903, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[42] Rieder Wochenblatt, December 22, 1903, 2.

[43] Rieder Wochenblatt, December 22, 1903, 2.

[44] Rieder Wochenblatt, December 22, 1903, 2.

[45] Michael Dobler to Linz Diocesan Office, October 10, 1903, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[46] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, October 10, 1903, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[47] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, October 10, 1903, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[48] Linz Diocesan Office to Josef Schachinger, October 12, 1903, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[49] Haag County Court Ruling, January 11, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[50] Ried County Office to Haag County Court, January 12, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[51] Ried County Office to Haag County Court, January 12, 1904.

[52] Franz Pumberger to Roger P. Minert, e-mail, July 1, 2013.

[53] Josef Schachinger to Ried County Office, March 12, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[54] Karl Binna to Ried County School Board, March 13, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag X L Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[55] Ried County Office to Ried County School District, March 26, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried X L 1904; Ried County Office to Wels District Court, March 30, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried X L 1904.

[56] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, April 28, 1904, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/