Joseph Smith’s Developing Relationship with the Apocrypha

Thomas A. Wayment

Thomas A. Wayment, “Joseph Smith's Developing Relationship with the Apocrypha,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 331–55.

Thomas A. Wayment was a professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University and publications director of the Religious Studies Center when this was written.

Several approaches to interpreting Joseph Smith’s use of the so-called Jewish and Christian apocryphal literature have been employed both by critics of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (hereafter LDS), and by those professing faith in the Church and whose interests may be classified as apologetic. These approaches span the range of being probative of Joseph Smith’s restoration of lost texts and scripture and being dismissive of Mormonism generally, because its sacred religious texts are founded on flagrant plagiarism of apocryphal literature.[1] Before one can answer the most important historical question at hand, how Joseph Smith used the Apocrypha and what relationship that body of literature had to early Mormon writings, it seems prudent to first of all establish some controls on the discussion. This is necessary because previous discussions have largely contented themselves with drawing out parallels between apocryphal writings and early Mormon publications without any discussion of whether or not Joseph Smith had access to the texts under discussion. Moreover, a wide variety of modern translations of ancient apocryphal texts are often employed when there is no possible way that someone living in the early nineteenth century could have known them. This is particularly important when citing phrases or words that Joseph Smith might have incorporated into the language of his revelations.

An additional concern is that the context in which these events took place has had little bearing on the discussion. At issue is the way that Joseph and his contemporaries handled and approached extrabiblical texts. It is necessary to ascertain their willingness to use extrabiblical literature in the establishment of doctrine and in the shaping of their theological teachings, and whether or not extrabiblical literature had any normative value for faith and faith communities. From an examination of the available literature on the subject, it would appear that the presence of themes, concepts, teachings, and phraseology from the Apocrypha in the Prophet’s writings has been viewed as extraordinary by both LDS scholars and those scholars wishing to undermine the claims of Mormonism. For LDS scholars, the presence of parallels to intertestamental and Christian Apocrypha in early Mormon writings has demonstrated that Joseph Smith restored ancient doctrines and practices. For non-LDS scholars, the presence of parallels has been used to draw attention to the possibility that Joseph plagiarized available sources. Unfortunately, neither solution is probable. The larger reality is that the presence of such parallels may arise out of a much more mundane event: his family, or perhaps even Joseph, was accustomed to reading a Bible in which the Apocrypha were included and that the language of the Apocrypha is echoed in Joseph’s early writings.[2] This paper will demonstrate that like many of his contemporaries, Joseph Smith was interested in apocryphal literature for its overall implications regarding the Christian biblical canon, its potential to hold hidden truths, and its allure in presenting “historical” details within the well-known biblical accounts.

Apocrypha in Nineteenth-Century New England

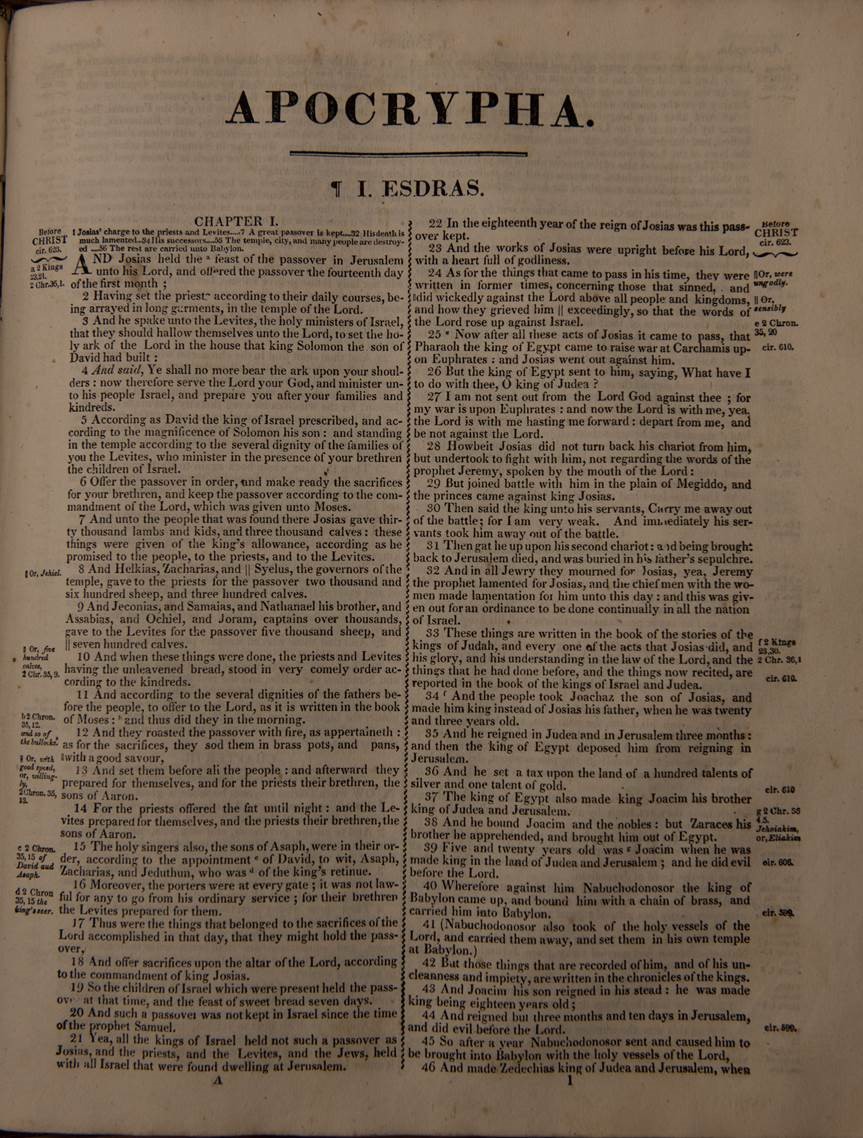

Of course, a discussion of this length cannot have as its aim a complete analysis of the history of the use of the Apocrypha in early nineteenth-century New England. Such a scope is simply too broad for a single, article-length study. However, there are contours of this discussion that are rather informative to laying a foundation for understanding Joseph Smith’s use of and interest in the category of texts known as Apocrypha.[3] Unlike today, studying the Apocrypha largely meant studying the Bible in nineteenth-century America, because until the very influential edition of the Apocrypha published by William Hone in London in 1820, the only real access a person had to the texts of the Apocrypha was through the commonly available English translations, printed in household or family Bibles. Despite Presbyterians lobbying for the removal of the Apocrypha from printed Bibles in 1825, Bibles still frequently contained the extracanonical books printed between the two testaments. There are no accurate figures as to what percentage of Bibles contained the Apocrypha in the early 1800s, but surviving Bibles from the time period suggest that the printing of the Bible with the Apocrypha was more frequent than the printing of the Bible without those texts. Unfortunately, we cannot state with any certainty what printing of the Bible Joseph Smith and his family were using in the period prior to his purchase of a Bible in April 1829. They could have owned a family Bible that had been around for some time, or they may have had a more recent printing that had been influenced by the Presbyterian ban on printing the Apocrypha. Thus, it is key to this discussion to recognize that any conclusions drawn from Joseph Smith’s use and reliance upon the Apocrypha in the pre-1829 period must be intimately connected to his study of the Bible with the realization that the Bible he used during that period may not have contained the printed Apocrypha.[4]

First page of the Apocrypha from an 1828 H. & E. Phinney Bible, the Bible used by Joseph Smith for the JST. Photo courtesy of Thomas A. Wayment.

First page of the Apocrypha from an 1828 H. & E. Phinney Bible, the Bible used by Joseph Smith for the JST. Photo courtesy of Thomas A. Wayment.

Joseph Smith and his family were not atypical for New Englanders of their day. They were religious Christians, so Bible study was part of their lives.[5] However, despite their interest in and family gatherings devoted to the reading of the Bible, Lucy Mack Smith, Joseph’s mother, would later claim apologetically that Joseph “never read the Bible through in his life.”[6] At least some people close to Joseph saw him less a student of the Bible and more of a cultural Bible reader, but also as one who was given to meditation and study.[7] Perhaps the most significant piece of evidence regarding Joseph Smith’s knowledge of the Bible comes from his report of the visit of the angel Moroni, who quoted from Malachi 3 in the vision. Joseph was able to note differences between the printed KJV translation of Malachi and the way Moroni quoted the same passages.[8] Some of these early reminisces have obvious apologetic and explanatory interests, and one can readily appreciate the fact that Lucy Mack Smith’s statement is partially interested in expelling the myth that her son Joseph was a careful student of the Bible in the time period surrounding the translation of the Book of Mormon. Despite this apologetic interest, her summary is consistent with other accounts that Joseph was ponderous, but not perhaps engaged in long periods of focused reading. Joseph’s account of Moroni’s visit, however, can be interpreted to mean that Joseph was very conversant with biblical language. Even this conclusion, however, must be tempered, because Joseph may have left out important details in his account, such as the fact that it required study to discover the differences between Moroni’s recital of Malachi and the printed edition of that text.

In addition to these statements, Joseph Smith Sr. in an interview once claimed that his son Joseph was “illiterate,” intending to convey that Joseph had not had formal academic training.[9] That Joseph Smith Jr. was “illiterate” has direct bearing on the question of whether he might have used the Apocrypha in shaping his Book of Mormon narrative. It speaks to his approach to using the Bible or biblical texts, how he used books as academic sources, and what academic resources he might have used. Overall, the picture of Joseph studying texts, reading books, and using those sources to shape his narrative seems unlikely. An additional piece of evidence strengthens the case. When translating the Book of Mormon, Joseph frequently and extensively cited from the Old Testament, and the language of the New Testament often permeates the Book of Mormon narrative. Rather than attempting to conceal Old Testament quotations, Joseph quoted them in nearly verbatim language to the printed KJV text at his disposal in large blocks, while at the same time frequently attributing them to their proper source (see 2 Nephi 11:2).

Important also to this discussion is Joseph Smith’s revelation recorded as Doctrine and Covenants 91. Pragmatically, the revelation is a statement on the printed Bible in Joseph’s possession during the time that he was working on his new translation of the Bible. As Joseph worked sequentially through the Bible—beginning with Genesis, then skipping to Matthew and working through the end of the New Testament, then returning to finish translating the Old Testament—he came to a section of his printed Bible that contained the Apocrypha. The section entitled “Apocrypha” in his Bible was printed in a smaller typeface and contained other minor formatting features that gave it a slightly different appearance than the canonical books.[10] For unknown reasons, Joseph sought divine guidance on the matter of what to do with the Apocrypha and received a revelation declaring, “Verily, thus saith the Lord unto you concerning the Apocrypha—There are many things contained therein that are true, and it is mostly translated correctly; There are many things contained therein that are not true, which are interpolations by the hands of men. Verily, I say unto you, that it is not needful that the Apocrypha should be translated” (D&C 91:1–3). This revelation would characterize Joseph’s future interactions with the Apocrypha, and it effectively became the way nearly all early Latter-day Saints approached apocryphal writings.

1 Enoch[11]

There has been a rather lively debate as to whether or not Joseph Smith used the pseudepigraphical book of 1 Enoch during the time he wrote about Enoch in a work that was later entitled the Book of Moses. Several new stories of Enoch are included in Joseph’s Book of Moses, and some have argued that he drew upon a published edition of Enoch while creating the new Enoch material. There was a widely available translation of 1 Enoch that was done in 1821 and was published in England,[12] a book that was potentially available to Joseph. The first definitive reference to the Lawrence edition of 1 Enoch is made by Parley P. Pratt, and there appears to be no concrete reference to the Lawrence edition during the time that Joseph Smith was writing the Book of Moses.[13] Instead, it appears that there are general similarities of theme between the two works, but there is no clear evidence of borrowing. Two viewpoints have arisen to explain this phenomenon: the “parallelist” viewpoint, which argues that Joseph Smith was able to provide a text with striking similarities to 1 Enoch but that was created independently of Lawrence,[14] and the “derivativist” viewpoint, which argues that Joseph Smith knew Lawrence’s text and was influenced by it in his writings.[15] Ultimately, the discussion of the Enoch material in early Mormonism relies on parallels that are quite general and clearly not based on slavish textual borrowing. If Joseph did use a source in composing the Book of Moses, then he used that source in a rather limited way, using it to broadly shape his ideas but not to provide language and structure to his narrative.

Echoes of the Apocrypha in Joseph Smith’s Early Writings

The process of translation of the Book of Mormon is described in a number of firsthand accounts, none of which mention the use of books that were consulted or other materials that were used in the translation, apart from the plates that Joseph kept mostly covered with a cloth and the paper sheets upon which his various scribes recorded the translation. We can be confident that Joseph did not look things up in secondary sources, read through books, or consult notes as he carried out the actual translation process. Emma Smith specifically claimed that Joseph did not use manuscripts, probably meaning he did not use loose sheets of paper with writing on them, or books during the writing process: “He had neither book nor manuscript that he read from . . . if he had anything of the kind he could not have concealed it from me.”[16] Others who were involved in the translation also affirm that no books were used or open during the translation process.[17] However, it is possible that in the months between receiving the plates in September 1827 and the end of 1828, Joseph may have studied and pondered the plates without actually translating the characters on them. During this time, it appears that he spent some time attempting to translate, but without any notable success. Joseph noted, “In December following [1827] we mooved to Susquehana. . . . the Lord had shown him [Martin Harris] that he must go to new York City with some of the c<h>aracters so we proceeded to coppy some of them and he took his Journy to the Eastern Cittys and to the Learned <saying> read this I pray thee . . . and he [Martin Harris] returned to me and gave them to <me to> translate and I said [I] cannot for I am not learned but the Lord had prepared spectacles for to read the Book therefore I commenced translating the char-acters.”[18] One way to understand this passage is to interpret it to mean that Joseph intended to say that he had not been able to translate any characters from the plates prior to the visit to Charles Anthon, an event that took place in the fall of 1828 and that is described here as visiting the “learned” in “new York City.”[19]

Important for this study is whether or not Joseph had time to carry out research that may have included, among other things, reading the Bible and the Apocrypha prior to beginning his translation of the Book of Mormon.[20] Although no sources indicate that Joseph was devoted to study during the months prior to beginning his translation of the gold plates, it is possible that some of his time was spent in reading. It may be that he read the Apocrypha during this time. This window of opportunity for study is important, because several words and phrases from the Apocrypha appear in the Book of Mormon narrative, an occurrence that has been noted with some enthusiasm in discussions of the matter.[21] The most significant piece of evidence in this regard is the appearance of the name Nephi in both the Book of Mormon (e.g. 1 Nephi 1:1) and the Apocrypha (2 Maccabees 1:36).[22] Because the name appears only in 2 Maccabees and the Book of Mormon, one can confidently surmise that Joseph Smith had heard or read the name in 2 Maccabees. The uniqueness of the name Nephi is alone sufficient evidence to suggest literary borrowing from 2 Maccabees. It is important to note that some editions of the Apocrypha printed in the years 1820–30 printed the name as Nephtai instead of Nephi. However, the 1828 Phinney Bible that Joseph Smith owned does print the name as Nephi in 2 Maccabees 1:36. Other examples of parallels between the Book of Mormon and the Apocrypha will show a similar pattern, namely that random phrases and names appear in both sources, even though no structural parallels are evident.

The most striking of the parallels, apart from the appearance of the name Nephi, is the occurrence of the name Ezias in 1 Esdras 8:2 and in Helaman 8:20.[23] Other examples of shared or similar language include, “for he was filled [drunk] with wine” (Judith 13:2; 1 Nephi 4:7), “took hold of the hair of his head” (Judith 13:7) versus “took . . . by the hair of his head” (1 Nephi 4:18), and “make an abridgment” (2 Maccabees 2:31; 1 Nephi 1:17).[24] These parallels bear strong overlap in language, but none of them arguably alters or informs the structure of the Book of Mormon. If the parallels were formative for the structure of the Book of Mormon narrative, or if the parallels followed an identifiable linear or sequential development, then one could argue that Joseph Smith indeed borrowed from the Apocrypha to build the Book of Mormon, at least in 1 Nephi. Instead, these parallels show that the language of the Apocrypha crept up in Joseph’s wording and phraseology. To a much larger extent, the language of the Bible—both the Old and New Testaments—also informed Book of Mormon language. This is unsurprising given Joseph’s lack of formal education, and it is reasonable that the parallels that exist can be explained in light of the fact that Joseph was most likely unaware of their source. But important to this discussion is the strong suggestion that Joseph read the Apocrypha early in his career and most likely during the time shortly prior to beginning translation of the characters on the gold plates.

The Acts of Paul and Joseph Smith’s Description of John C. Bennett

By 1841, the Saints had moved from New York to Ohio to Missouri and then to Nauvoo, Illinois, and had begun to openly embrace a more traditional model of education, where leading men of the city met together in a school setting and studied the languages of the Bible and topics associated with religious thinking and history. In that setting—the Nauvoo Lyceum—Joseph Smith offered a physical description of John C. Bennett, a man who had recently been baptized into the faith and who had only just arrived in Nauvoo. Joseph described Bennett in terms that are reminiscent of a passage from the Acts of Paul. LDS scholars have long recognized the potential parallel and have commented upon the possibility that Joseph Smith may have been aware of the description of Paul found in the Acts of Paul and the public description given of John C. Bennett.[25] The Prophet’s description of Bennett is recorded as follows: “He is about five foot high; very dark hair; dark complexion; dark skin; large Roman nose; sharp face; small black eyes, penetrating as eternity; round shoulders; a whining voice, except when elevated and then it almost resembles the roaring of a Lion.”[26] One can readily see the broad parallel language in the Acts of Paul: “At length they saw a man coming (namely Paul), of a low stature, bald (or shaved) on the head, crooked thighs, handsome legs, hollow-eyed; had a crooked nose; full of grace; for sometimes he appeared as a man, sometimes he had the countenance of an angel.”[27]

Fortunately, the genetic relationship between the Acts of Paul and Joseph Smith’s description of John C. Bennett is clearer and more direct. We can state with near certainty that Joseph Smith owned a copy of William Hone’s influential The Apocryphal New Testament, where he would have had access to the Acts of Paul and its description of Paul. Specifically, we know that Joseph owned a copy of Hone’s edition of the Apocrypha from the 1832 Ravenna, Ohio, printing and that he later donated that copy to the Nauvoo Library.[28] The Acts of Paul description shows several marked parallels to Joseph’s description of John C. Bennett. But rather than quote from the Acts of Paul directly, it once again appears that an ancient source shaped and molded Joseph’s language, perhaps even without Joseph being openly aware of the source of the parallel. When compared side by side, the parallels suggest that Joseph was drawing upon memory to aid him in the description and that the parallel was not overt or perhaps even intentional.[29] Joseph was attempting to flatter Bennett, the former quartermaster general for the state of Illinois, and endear him to the audience gathered at the Lyceum.

Further evidence of the use of William Hone’s The Apocryphal New Testament can be seen in an 1842 editorial authored by W. W. Phelps, wherein he made allusion to the Protevangelium of James.[30] The editorial mistakenly connects two figures named Zacharias: Zacharias the son of Barachias, who was murdered (Jesus is recorded to have mentioned Zacharias’s murder in Matthew 23:35, when he lists the first and last martyrs of the Old Testament), and Zacharias the father of John the Baptist, who as far as we know was not the son of Barachias.[31] This mistake most likely stemmed from Phelps’s reading of Hone’s Apocryphal Testament; in the Protevangelium of James 24, Zacharias the father of John the Baptist is specifically mentioned as being murdered by Herod the Great in the Temple at Jerusalem. The editorial no doubt has the Protevangelium of James in mind when it also mentions the murder of Zacharias by Herod and adding the detail “as Jesus said,” thus alluding to Matthew 25:35.[32] Because these two sources uniquely connect Zecharias son of Barachias in this way, we can be confident that Joseph Smith and other LDS leaders were reading William Hone’s Apocryphal Testament during the Nauvoo period and that snippets from that volume were at times used to bolster statements made in the canonical gospels. Joseph’s usage of the Apocrypha from this period is rather loose and probably relied on memory, whereas Phelps’s usage was more direct and explicit.

These positive assessments of apocryphal literature must be counterbalanced with two somewhat negative appraisals of the Apocrypha in the first church-owned newspaper, the Evening and Morning Star. In July 1832, the newspaper ran an editorial summarizing the validity and reliability of various biblical accounts. At the end of the second paragraph, 2 Maccabees is quoted with the intent to establish and confirm biblical accuracy. But in doing so the editorial states, “which is recorded in the second Chapter of II Maccabees, which the wisdom of man has seen fit to call Apocrypha.”[33] The statement is hardly a ringing endorsement of the Apocrypha as a source of history, but at the same time the reference also demonstrates open and rather uncritical usage of the Apocrypha. In January 1833 the Evening and Morning Star again mentioned the Apocrypha with reference to the additions to the book of Esther in the Apocrypha where it states, “ancient men of the world, put down as doubtful.”[34] Both editorials suggest that the saints were putting into practice a principle that would be revealed in March 1833 as Doctrine and Covenants 91, which reads, “concerning the Apocrypha—There are many things contained therein that are true.”

The Book of Jasher

To help document whether or not Joseph Smith’s perceptions and opinions towards the Apocrypha developed over time, it is important to consider Joseph’s and other’s reactions to the English publication of the Book of Jasher, a book that has always been considered apocryphal both in content and origins. On June 1, 1840, the Times and Seasons reran a short announcement publicizing an English printing of the apocryphal Book of Jasher that would eventually appear in print in August of that same year.[35] Like other nineteenth-century Americans, the Saints were quite excited by the publication of what was supposedly the lost Book of Jasher in August 1840.[36] What is key to the excitement surrounding the publication of the Book of Jasher is that it is mentioned twice in the Old Testament (2 Samuel 1:18 and Joshua 10:13), and was and is considered a lost book of the Bible. For these reasons, it has over the centuries been of great antiquarian and religious interest.

In the hype leading up to the publication, a rather public exchange in England between a publisher and scholar included claims of discovery and antiquity for a forthcoming edition of the Book of Jasher.[37] Interestingly, the debate was founded in part upon a relatively recent forgery of the Book of Jasher by Jacob Ilive (printed in 1756), who printed his forged account for monetary gain and public recognition.[38] In 1828 a translation of the Book of Jasher based on Moses Samuel’s edition of a medieval text of the Book of Jasher was published in England. That publication, in part, helped end efforts by an English printer to republish the eighteenth-century forgery, but the Moses Samuel translation had very little claim to antiquity either. But despite the questionable basis of the Samuel text and dubious claims for its antiquity, the publication was well received and caused quite a stir. It appears that a letter written by Joseph Smith, Sidney Ridgon, and Frederick G. Williams to the Saints in Missouri on June 25, 1833, was an attempt to address some of the public concerns regarding the questions being raised in England over competing claims to having found the original Book of Jasher. The letter reads in part, “We have not found the Book of Jasher, nor any other of the lost books mentioned in the Bible as yet; nor will we obtain them at present. Respecting the Apocrypha, the Lord said to us that there were many things in it which were true, and there were many things in it which were not true, and to those who desire it, should be given by the Spirit to know the true from the false.”[39] Because the letter corresponds roughly to the time after Samuel’s translation appeared in print but seven years prior to the American publication of the Book of Jasher by Samuel Mordecai in 1840, this suggests that the saints were interested in the discussion taking place in England and were hopeful that a genuine edition of the Book of Jasher would soon be available to them. The letter takes a skeptical tone, but ironically the copyright to the English edition criticized in the letter was later sold to an American printer in 1839 (Mordecai Manuel Noah). Noah succeeded in publishing the translation of Moses Samuel, and copies of that book would eventually influence several articles written by Latter-day Saints. Despite rather grand claims in the original publication of Moses Samuel’s translation and the later printing of it in the United States, Joseph Smith demonstrates a certain level of caution in equating the book with the actual lost Book of Jasher.

John Taylor, and not Joseph Smith, appears to have offered the most enthusiastic endorsement of the Mordecai Noah Book of Jasher. In a Times and Seasons editorial entitled “The Book of Jasher” from June 1, 1840, John Taylor offered the following words of praise and endorsement of the Mordecai Noah edition: “It is full of interest, and written with a warmth of piety and sacred devotion, worthy of taking an equal rank with any of the missing books, not strictly canonical.”[40] Of course, Taylor had not read the book yet, but his prepress excitement is obvious. Additionally, Taylor stated that the book “amplifies the events recorded in Scripture” although in a later editorial entitled “Persecution of the Prophets,” he did detail a minor difference between the contents of the Book of Jasher and the canonical book of Genesis.[41] In that same editorial, Taylor used the Book of Jasher as a proof text to prove the recently published Book of Abraham, where he stated, “Abraham, the prophet of the Lord, was laid upon the lion bedstead for a slaughter; and the book of Jasher, which has not been disproved as a bad author, says he was cast into the fire of the Chaldees.”[42]

In the December 15, 1844, issue of the Times and Seasons, Taylor again returned to the topic of the Book of Jasher, where he used the contents of that book to confirm historical facts: “To strengthen this idea let us introduce a few paragraphs from the Book of Jasher, not allowing it to be revelation but history sustained by other history.”[43] That same “history” probably influenced the connection that Shem and Melchizedek were the same person, a teaching that also appears in the Lectures on Faith, a publication that was also edited by John Taylor.[44] The Book of Jasher also conflates the two people, and the proximity of Taylor’s endorsement of the Book of Jasher, followed immediately by the idea that Shem and Melchizedek are the same person, provide fairly conclusive evidence that Taylor was using Jasher as a source.[45]

In 1872 John Taylor again offered a public endorsement of the history of the Book of Jasher, but he stopped short of endorsing it as doctrinally accurate or as having canonical status.[46] The overt acceptance of Jasher as a historical source by Taylor, however, confirms earlier evidence that Joseph Smith was also likely to accept the Apocrypha as having historical value that should be used judiciously. Of course the evidence in this instance relates to John Taylor and is not directly derivative of Joseph Smith’s sentiments, but it does show that the prevailing opinion regarding the use of Apocrypha was precisely that given in a revelation dated March 9, 1933, by Joseph Smith: “There are many things contained [in the Apocrypha] that are true, and it is mostly translated correctly; There are many things contained therein that are not true, which are the interpolations of men” (Doctrine and Covenants 91:1–2). The evidence preceding and continuing up through the Nauvoo period seems consistent in suggesting that the saints were open when using the Apocrypha as a source to document history and that they were very often willing to accept parts of the Apocrypha as being able to fill out the canonical record in minor ways.

General Remarks on the Apocrypha

Taylor’s approach to the Book of Jasher and the revelation on the subject of the Apocrypha demonstrate a tone that is also expressed in an experience of Joseph Smith’s, where he commented upon a family Bible owned by Edward Stevenson. The event took place in Pontiac, Michigan, in 1834, when Joseph visited a small gathering of saints in that city. According to Stevenson’s journal, “the Prophet looked over our large Bible and remarked that much of the Apocrypha was true, but it required the Spirit of God to select the truth out of those writings. He also looked over a ‘large English Book of Martyrs,’ and expressed sympathy for them and later reported that he had asked through the Urim and Thummim regarding the lives of the martyrs mentioned in the book.”[47]

Joseph Smith may also have expressed support for the Apocrypha during the Nauvoo Temple dedication. As part of the dedication ceremony, several books were to be sealed up in the cornerstone of the temple, including a Bible. Although the source of information for the report is given nearly fifty years after the event took place, Joseph Smith is reported to have remarked publically that the Bible that was being laid up in the cornerstone was lacking the Apocrypha. When Joseph recognized that it did not contain the Apocrypha, he asked Reynolds Cahoon to find a Bible that did. Cahoon volunteered to go home and cut out the Apocrypha from his family Bible and donate it. Joseph accepted the offering and placed the emended Bible in the cornerstone of the temple.[48]

Both of these examples serve to confirm that Joseph Smith publicly and openly used the Apocrypha and that he most likely had a great deal of trust in the history contained in at least some of the Apocryphal books. Other statements show that he held hope that other books belonging to what we might refer to nowadays as the Apocrypha would someday be discovered. In connection with a comment on Jude 1:14–15, Joseph Smith mentioned that there were “lost books” of the Bible.[49] He also noted in a discourse on October 5, 1840, that Enoch had at some point in time appeared to Jude.[50] A similar interest in Enoch can be seen in a statement made by Parley P. Pratt regarding the publication of Laurence’s 1838 Book of Enoch, which Pratt called a “remarkable book.” Finally, the heading to Doctrine and Covenants 7 states, “The revelation is a translated version of the record made on parchment by John and hidden up by himself.”[51] This promising introduction carries with it the insinuation that the revelation known today as section 7 of the Doctrine and Covenants is a literal translation from an ancient parchment. No manuscript was ever produced by Joseph Smith or his scribes, and there is no evidence in the sources that his experience with the “parchment” that John hid up was anything other than a visionary experience, but it does support the conclusion that Joseph was consistently interested in lost books of the Bible, particularly books that could inform and expand the Saints’ understanding of the ancient apostles and biblical writers.

Conclusions

The surviving evidence favors the conclusion that Joseph Smith was influenced directly by the Apocrypha. As a reader of the Bible, Joseph would have encountered the Apocrypha during personal or family reading of the Bible. Those early experiences are now rather difficult to trace, but the presence of several names in the Book of Mormon that have parallels to unique names in the Apocrypha suggest that these Apocryphal names may have influenced Joseph in some way. These names, places, and events might have become a part of Joseph’s vocabulary, surfacing perhaps randomly in the translation of the Book of Mormon.

Because those same apocryphal writings do not bear any direct influence on the narrative structure of the Book of Mormon, it is unlikely that the parallels between them are anything more than memories that surfaced in Joseph’s thoughts during the translation process; reports of the translation confirm that no outside books were used or consulted during that time. Joseph may not have even been aware that the parallels between some books of the Apocrypha and the Book of Mormon existed. The process of translation relied in part upon Joseph and his personal abilities.

A similar occurrence is demonstrated in Joseph Smith’s description of John C. Bennett, where there are evident parallels to the Acts of Paul, a Christian apocryphal source that was not part of his Bible but another book that came into Joseph’s possession in the 1830s. Again, the connection between the Acts of Paul and the description of John C. Bennett seems to be memory. Joseph appears to have remembered a structure and general subject outline, but he did not remember precise phrases and exact content. Later Latter-day Saint writers show a marked interest in the Apocrypha because they found it probative of Joseph Smith’s teachings and revelations. They found proof texts for the doctrines of early Mormonism, and as a result they began to trust the history of those sources in other matters as well. That growing relationship of trust in the Apocrypha as a source of history is also evident in several statements attributed to Joseph Smith. Therefore it is a safe conclusion that Joseph often exhibited an open trust in the Apocrypha as genuine history.

Notes

[1] These two extremes can be seen in the widely read work by Hugh Nibley, Since Cumorah (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: FARMS, 1988), 80–83, 95–101 and in the rhetorically heavy-handed approach of Jerald and Sandra Tanner: “Joseph Smith’s Use of the Apocrypha,” Salt Lake City Messenger 89 (December 1995): 1–14. For a general Latter-day Saint treatment of the theme, see C. Wilfred Griggs, ed., Apocryphal Literature and the Latter-day Saints (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1986). Nibley’s approach was to use apocryphal texts to support LDS claims to authority, lost texts, etc. without discussion of the quality or context of the sources he was citing from. Equally problematic is the work of the Tanners, who generate rather weak parallels to Apocryphal literature and then offer the rather simplistic explanation of forgery and plagiarism without assessing the quality of the parallels. Nibley’s work is carried to the extreme in the review of the Tanners’ work by John A. Tvedtnes and Matthew Roper, “Joseph Smith’s Use of the Apocrypha: Shadow or Reality?” FARMS Review 8, no. 2 (1996): 326–72. Surprisingly, Tvedtnes and Roper respond to the Tanners’ assertion by noting more parallels to the Apocrypha (and the Old Testament) rather than assessing the quality of the parallels presented by the Tanners. See also Matthew Roper, “Review of Covering up the Black Hole in the Book of Mormon, by Jerald and Sandra Tanner,” Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 3 (1991): 170–87; John A. Tvedtnes, “Review of Covering up the Black Hole in the Book of Mormon,” Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 3 (1991): 188–230.

[2] This conclusion cannot address the thematic parallels that have been discussed in Latter-day Saint writings. Those conclusions must be assessed individually and on their own merits.

[3] The modern distinctions between the word apocrypha, which now frequently refers to texts written by Christians and for Christians, and the word pseudepigrapha, which is used to describe apocryphal texts arising from the intertestamental period, cannot be maintained in this discussion, because it would certainly be anachronistic. These modern distinctions are completely arbitrary and were unknown to nineteenth-century readers.

[4] The Bible purchased at the Grandin bookstore in April 1829 contained fourteen apocryphal texts printed between the Old and New Testaments in a typeface that was smaller than the canonical texts. Joseph Smith Jr. owned three Bibles in his lifetime that are known to scholars. He owned an 1828 H. & E. Phinney Bible, published in Cooperstown, NY; a Bible published by Charles Yost in Philadelphia (year unknown); and a miniature Bible also printed on the Phinney Press. I have been able to examine the first two Bibles, but not the miniature Bible, which is privately owned. I would like to thank Richard P. Howard for carefully checking the 1828 Phinney Bible for markings in the section of the Apocrypha and Brent Ashworth for allowing me to look at the Joseph Smith Bible published by Yost. Neither Bible shows any indication of markings or notations in the Apocrypha that would signal usage of those books. From what I am able to ascertain, the miniature Bible does not have any markings in it other than Joseph Smith’s signature on one of the early pages of the Bible.

[5] Milton V. Backman Jr., Joseph Smith’s First Vision: Confirming Evidences and Contemporary Accounts, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1980), 155–57;Rodger I. Anderson, Joseph Smith’s New York Reputation Reexamined (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1990), 171. Compare Philip L. Barlow, Mormons and the Bible: The Place of the Latter-day Saints in American Religion (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), 13; Barlow argues that Joseph was familiar with biblical language.

[6] Lavina F. Anderson, ed., Lucy’s Book: A Critical Edition of Lucy Mack Smith’s Family Memoir (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2001), 344.

[7] Anderson, Lucy’s Book, 344; Roberts, Studies, 151. Compare Dan Vogel, Joseph Smith: The Making of a Prophet (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2004), 27; Vogel cites Joseph Smith Sr.’s blessing to his son as evidence that Joseph had deeply meditated on the Bible from his childhood. Given the available evidence, it seems that the language of the 1834 blessing is derived from its 1834 context than a clear statement on practice when Joseph was a teenager.

[8] Jan Shipps, “The Prophet Puzzle: Suggestions Leading toward a More Comprehensive Interpretation of Joseph Smith,” in The Prophet Puzzle: Interpretive Essays on Joseph Smith, ed. Bryan Waterman (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1999), 34; Stephen E. Robinson, “Review of D. Michael Quinn, Early Mormonism and the Magic World View (1st ed.),” BYU Studies 27, no. 4 Fall (1987): 94.

[9] Dan Vogel, comp., Early Mormon Documents,5 vols. (Salt Lake City: Signature books, 1996), 1:457.

[10] The earliest copies of the revelation known as D&C 91 entitle the section, “A Revelation concerning Apocrypha.” The revelation is in the handwriting of Frederick G. Williams and was likely recorded in Kirtland, perhaps in 1833. The lack of the definite article before Apocrypha is peculiar, but it represents the title of the section exactly as it appeared in the printed Bible Joseph was using.

[11] I would like to thank Professor Jared W. Ludlow for his help in looking at the Enoch parallels in early Mormon writings. The number of articles and chapters on the subject are considerable, particularly in light of such meager evidence.

[12] See Richard Laurence, trans., The Book of Enoch, the Prophet: An Apocryphal Production, Supposed to Have Been Lost for Ages (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1821).

[13] For a discussion of Joseph Smith’s Enoch references and their relationship to the Lawrence edition, see Jed L. Woodworth, “Extra-Biblical Enoch Texts in Early American Culture,” in Archive of Restoration Culture: Summer Fellows’ Papers 1997–1999, ed. Richard L. Bushman (Provo, UT: Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for Latter-day Saint History, 2000), 185–93.

[14] See Hugh Nibley, Enoch the Prophet, Collected Works of Hugh Nibley, vol. 2 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: FARMS, 1986).

[15] See D. Michael Quinn, Early Mormonism and the Magic World View, rev. ed. (Salt Lake City: Signature, 1998). Compare Salvatore Cirillo, “Joseph Smith, Mormonism, and Enochic Tradition” (master’s thesis, Durham University, 2010). Cirillo was heavily influenced by Quinn’s work and argues against Nibley’s conclusions. Cirillo thinks instead that Joseph Smith or his scribes were familiar with Enoch texts and thereby informed Joseph during the period that he created the book of Moses.

[16]“Last Testimony of Sister Emma,” Saints’ Advocate 2, no. 4 (October 1879): 51.

[17] Interview, October 17, 1881, in the Chicago Times, cited in David Whitmer Interviews: A Restoration Witness, ed. Lyndon W. Cook (Orem, UT: Grandin, 1991), 76; J. W. Chatburn, interview, June 15, 1882, in Saints’ Herald, cited in David Whitmer Interviews, 92; Interview, July 16, 1884, in St. Louis Republican, cited in David Whitmer Interviews, 139–40.

[18] Dean C. Jessee, ed., The Personal Writings of Joseph Smith, 1:9. Compare Brant A. Gardner, The Gift and Power: Translating the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2011), 259–60; David E. Sloan, “The Anthon Transcripts and the Translation of the Book of Mormon: Studying It Out in the Mind of Joseph Smith,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 5 (1996): 57–81.

[19] Joseph Smith, comp., History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1978), 1:62–65.

[20] On the possibility that Joseph studied at the Manchester, New York, library, see Robert Paul, “Joseph Smith and the Manchester (New York) Library,” BYU Studies 22, no 3. (Summer 1982): 1–26.

[21] Jerald and Sandra Tanner, “Joseph Smith’s Use of the Apocrypha,” 1–14.

[22] John Gee, “A Note on the Name Nephi,” Insights, November 1992. The source suggests that it is possible that Joseph Smith was familiar with the name Nephi from the Apocrypha. The newsletter states, “The Apocrypha was a part of the Smith family Bible, so it is possible that Joseph Smith was acquainted with the name from that source.” See also John Gee, “Four Suggestions on the Origin of the Name Nephi,” Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 1–3, which responds to the idea that the name Nephi derives from Maccabees. Compare John Gee, “A Note on the Name Nephi,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 1 (1992): 189–91. The name Nephi may indeed have an ancient Egyptian (or otherwise) origin, but that does not disprove the possibility that Joseph learned the name through reading 2 Maccabees.

[23] The parallel to 1 Esdras 8:2 is not mentioned in either Dennis L. Largey, ed., Book of Mormon Reference Companion (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003), or Melvin J. Thorne, “Ezias,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 2:481.

[24] All quotations of the Apocrypha are taken from the 1828 Phinney Bible.

[25] Richard Lloyd Anderson, Understanding Paul (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983), 399–402; Alexander L. Baugh, “Parting the Veil: The Visions of Joseph Smith,” BYU Studies 38, no. 1 (Winter 1999): 23–24; Thomas A. Wayment, “Joseph Smith’s Description of Paul,” Mormon Historical Studies 13 (Spring/

[26] Dean C. Jessee, ed., The Papers of Joseph Smith, 2 vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1989–92), 1:431, as reported by William Clayton.

[27] Translation from William Hone, The Apocryphal New Testament (London: Ludgate Hill, 1820), Acts of Paul 1:7.

[28] Kenneth W. Godfrey, “A Note on the Nauvoo Library and Literary Institute,” BYU Studies 14, no. 3 (Summer 1974): 387.

[29] Thomas A. Wayment, “Joseph Smith’s Description of Paul,” 39–53.

[30] Gerald E. Jones, “Apocryphal Literature and the Latter-day Saints,” in Apocryphal Writings and the Latter-day Saints, ed. C. Wilfred Griggs (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1986), 26.

[31]“Persecution of the Prophets,” Times and Seasons, September 1, 1842, 902.

[32] Latter-day Saints have associated the W. W. Phelps editorial with Joseph Smith for many years because the editorial was published in the volume Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, comp. Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1979), 261. The contents of the editorial were reprinted in that volume as though they were spoken directly by Joseph.

[33]“Hosea III,” Evening and Morning Star, July 1832, 6.

[34]“The Book of Esther,” Evening and Morning Star, January 1833, 6.

[35] Brandt, “The Book of Jasher and the Latter-day Saints,” in Apocryphal Writings and the Latter-day Saints, ed. C. Wilfred Griggs (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1986), 300; this source mistakenly reports that the original article appeared in the New York Sun. The original actually appeared in the New York Star and was reprinted in the Times and Seasons, June 1, 1840, 127.

[36] The publication mentioned in the Times and Seasons was the Sefer ha-yashar, The Book of Jasher Referred to in Joshua and Second Samuel: Faithfully Translated from the Original Hebrew into English (New York: M. M. Noah & A. S. Gould, 1840).

[37] See Arthur A. Chiel, “The Mysterious Book of Jasher,” Judaism 6, no. 3 (Summer 1977): 371–72. The debate took place in 1828 when the publisher Philip Rose claimed in November 1828 in the Bristol Gazette that he would soon publish the book of Jasher that he had recovered from a scroll discovered in Persia. On November 19, 1828, Moses Samuel, a scholar from Liverpool, reported in the London Courier that he had also come to possess a copy of the ancient book of Jasher and that he had plans to publish it.

[38]“The Mysterious Book of Jasher,” 372–73.

[39] Smith, History of the Church, 1:363.

[40] Times and Seasons, June 1, 1840, 126. The information in the editorial was found in pre-press releases in the United States and was not a result of John Taylor having read the published edition, which did not appear in print for two months.

[41] Times and Seasons, September 1, 1842, 902.

[42] Times and Seasons, September 1, 1842, 902.

[43] Times and Seasons, December 15, 1844, 745.

[44] Times and Seasons, December 15, 1844, 745–46; N. B. Lundwall, comp., Lectures on Faith (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1999). These lectures were delivered in 1834 and published in 1835. For the issue of authorship, see Larry E. Dahl and Charles D. Tate Jr., eds., The Lectures on Faith in Historical Perspective (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1990); Noel Reynolds, “Case of Sidney Rigdon as Author of the Lectures on Faith,” Journal of Mormon History 31 (2005): 1–41; A. J. Phipps, The Lectures on Faith: An Authorship Study (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1977).

[45] This was noted first by Gerald E. Jones, “Apocryphal Literature and the Latter-day Saints,” 53–107.

[46] Journal of Discourses, 14:356–57.

[47] Hyrum L. Andrus and Helen Mae Andrus, They Knew the Prophet (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1999), 96, where the journal of Edward Stevenson is published.

[48]“Recollections of the Prophet Joseph Smith,” Juvenile Instructor, March 15, 1892, 174.

[49] HC 1:132.

[50] The discourse is reported by Robert B. Thompson in Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook, eds., The Words of Joseph Smith: The Contemporary Accounts of the Nauvoo Discourses of the Prophet Joseph (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1980), 41.

[51] The source for the heading is somewhat in doubt. The first printing of this phrase is in the 1833 printing of the Book of Commandments (chapter 6), but it is quite unlikely that Joseph Smith authored the phrase himself. The phrase does not appear on the manuscript whereon the revelation was first recorded, and thus Joseph did not dictate the phrase at the time of the revelation. During the time that the Book of Commandments was being typeset in Missouri, Joseph was in Kirtland and had not been in Missouri in the previous year. If he did write the phrase, he would have either sent it in a letter or via Oliver Cowdery, who was traveling back and forth between Ohio and Missouri.