Uproar in Upper Austria (1904)

Roger P. Minert, Against the Wall: Johann Huber and the First Mormons in Austria (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 83–115.

As 1904 dawned, Johann Huber was nearly forty-three years old. He had a substantial and successful farm and a large family and had been a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for nearly four years. He led a tiny LDS branch—the only one in the Dual Monarchy—but had little contact with other Latter-day Saints. Despite his isolation, he was an ordained priest in the Aaronic Priesthood and had a vibrant testimony of the gospel that he regularly expressed to employees and neighbors. Nowhere in the surviving literature is there any hint that he regretted his decision to join the new faith or ever considered returning to his native church.

The Fledgling Rottenbach LDS Branch

Several other men who had joined the Mormons were living and working on the Michlmayr farm or nearby, enough that a small but independent LDS branch (with five members of record) was in operation in Rottenbach. Worship services were held in the granary in the northern corner of the farmhouse. Family lore has it that the trap door that opens from that thirty-by-forty-foot room into the equipment room below was of value on several occasions: “They had a boy [Johann] positioned at the window looking down the road toward town. If he saw police (or anybody else with harmful intent) coming toward the farm, he sounded the alarm and everybody used the trap door to get into the room below. From there, they could escape out the back gate of the farm buildings into the fields and orchards and pretend to be at work. That way nobody was ever able to invade their meetings.”[1]

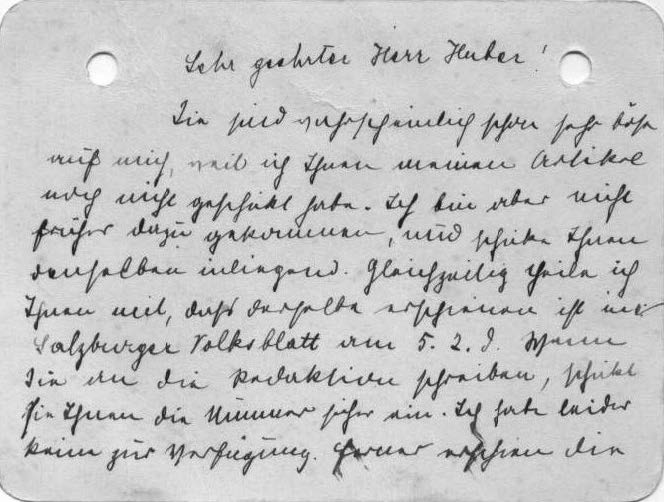

This card informed Huber that Spiegel's article on Mormonism had appeared in several major newspapers in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

This card informed Huber that Spiegel's article on Mormonism had appeared in several major newspapers in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

By 1904, the man who taught the restored gospel to Huber, Haag native Martin Ganglmayer, had concluded his missionary service in Germany and had returned to Salt Lake City. From there he wrote another long letter to the Rottenbach convert on January 6. While expressing his gratitude that Johann had written with news from the homeland, he easily became emotional: “But my blood boiled when I read of the unrighteous persecution and the sufferings to which you’ve been subjected.”[2] Had he remained in Austria, he would have gladly suffered with his friend (he wrote). As it was, he could only offer solace and support: “My soul rejoices at the thought that you’re made of such noble and unbending matter. You may be assured that the angels and saints who suffered persecution, mockery, and hatred for the testimony of Jesus are rejoicing with you now. . . . Let none of you be ashamed of the gospel or deny the treasures of truth, however unpopular they may be.”[3]

The controversy over confession in the public school had long been connected with the question regarding the capability of Johann and Theresia Huber to raise their children properly (i.e., as upright Catholics). Just when the future looked dark for the Hubers in this regard, the appellate court in Wels handed down a ruling that brought some relief. Huber had appealed the January 12 decision regarding Scheidinger’s appointment as guardian, which the Wels court granted, thus overturning the Haag County Court action. The Wels court reviewed many documents filed by various parties and decided that some of the charges against Huber stemmed from actions taken before specific court rulings were issued; those actions could not be classified as offenses committed by Huber. The final paragraph of the Wels decision forestalled any action against the Mormons: “It remains the duty of this court to determine whether and to what extent the reports are correct, given that Johann Huber disputes the content of the reports. Because the necessary evidence is lacking, the first court ruling must be considered null and void. A new case must be opened and the necessary ruling be issued anew.”[4]

While Michlmayr Johann Huber was dealing with these court issues, he was still smarting from the newspaper article that attacked him in late December 1903. As could be expected by now by anybody who knew him, he defended himself, not to the same newspaper but to the liberal Deutscher Michel that was published in the provincial capital city of Linz. He invested most of his text in describing the events that led him to consider leaving the Catholic Church in 1899 and even included quotations from the letters he had written to Pastor Aepflbaur and Vicar Schöfecker at the time.[5] He had threatened at least once to take his case to the public, and now, with this letter in the hands of a wider readership (albeit mostly liberals), his goal was achieved.

National Newspaper Coverage of Mormonism in Rottenbach

The year 1904 would be remarkable in the history of the LDS Church in Austria, thanks to other events that began in January. A Viennese reporter named Else Spiegel became the agent Huber needed to support his fledgling public relations campaign. It is not known precisely how Frau Spiegel learned of the existence of the LDS Church in Austria, but perhaps she had read letters in the Rieder Wochenblatt or the Deutscher Michel. In any case, she wrote to Johann Huber in January, and he responded by sending her some LDS literature. She wrote again just days later to ask if he would be willing to answer specific questions regarding the church and his faith—a golden opportunity for this self-appointed missionary. Frau Spiegel’s questions were insightful:

1. Where did you learn of the existence of Mormonism? Did a missionary come to Rottenbach?

2. When did he come there? How long has there been a Mormon congregation in Rottenbach?

3. Why were you chosen to be the leading elder?

4. Is the congregation in Rottenbach the only one, or is there another close by?

5. How often and where do you hold your worship services?

6. Would you describe for me a worship service? Are they held in secret or does the [Catholic] priest know about them?

7. How many members belong to your congregation? Do they own property in common, and what is the status of polygamy?

8. Is Mormonism recognized by the government as a legal church?[6]

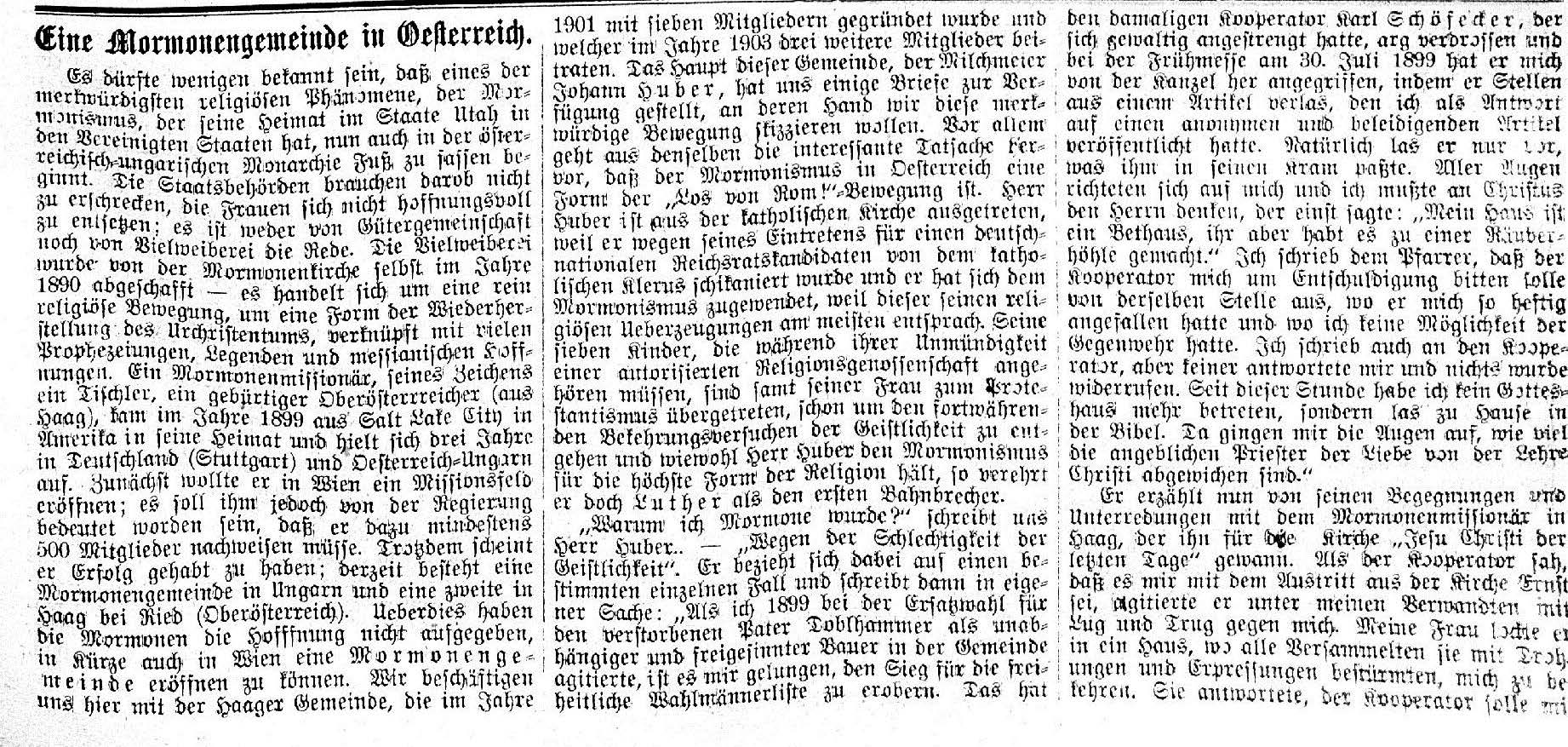

Although Spiegel's article appeared among classified advertisements on page 17-18, it offered the public a candid report on Mormonism. Salzburger Nachrichten, February 6, 1904.

Although Spiegel's article appeared among classified advertisements on page 17-18, it offered the public a candid report on Mormonism. Salzburger Nachrichten, February 6, 1904.

Else Spiegel then wrote a lengthy article on the LDS faith and the conversion of Johann Huber; it was published in newspapers in Vienna and Salzburg, Austria, and in Agram (now Zagreb), Croatia. Her letter to Huber in early February suggests that the article appeared in several other cities in the empire as well. The tone of the article was mostly positive. It appears she presented Huber’s comments with great accuracy, so he must have been pleased with this promotion of his new church. The article began with this paragraph:

It is probable that few people know about this, but one of the oddest religious phenomena, Mormonism, that has its home in Utah in the United States, has begun to gain a foothold in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. Government officials need not panic and women need not get their hopes up [!]. Nobody is talking about common property rights or polygamy (polygamy was discontinued by the Mormons themselves in 1890). This is purely a religious question, the restoration of a form of the original Christian church, in connection with many prophecies and Messianic hopes.[7]

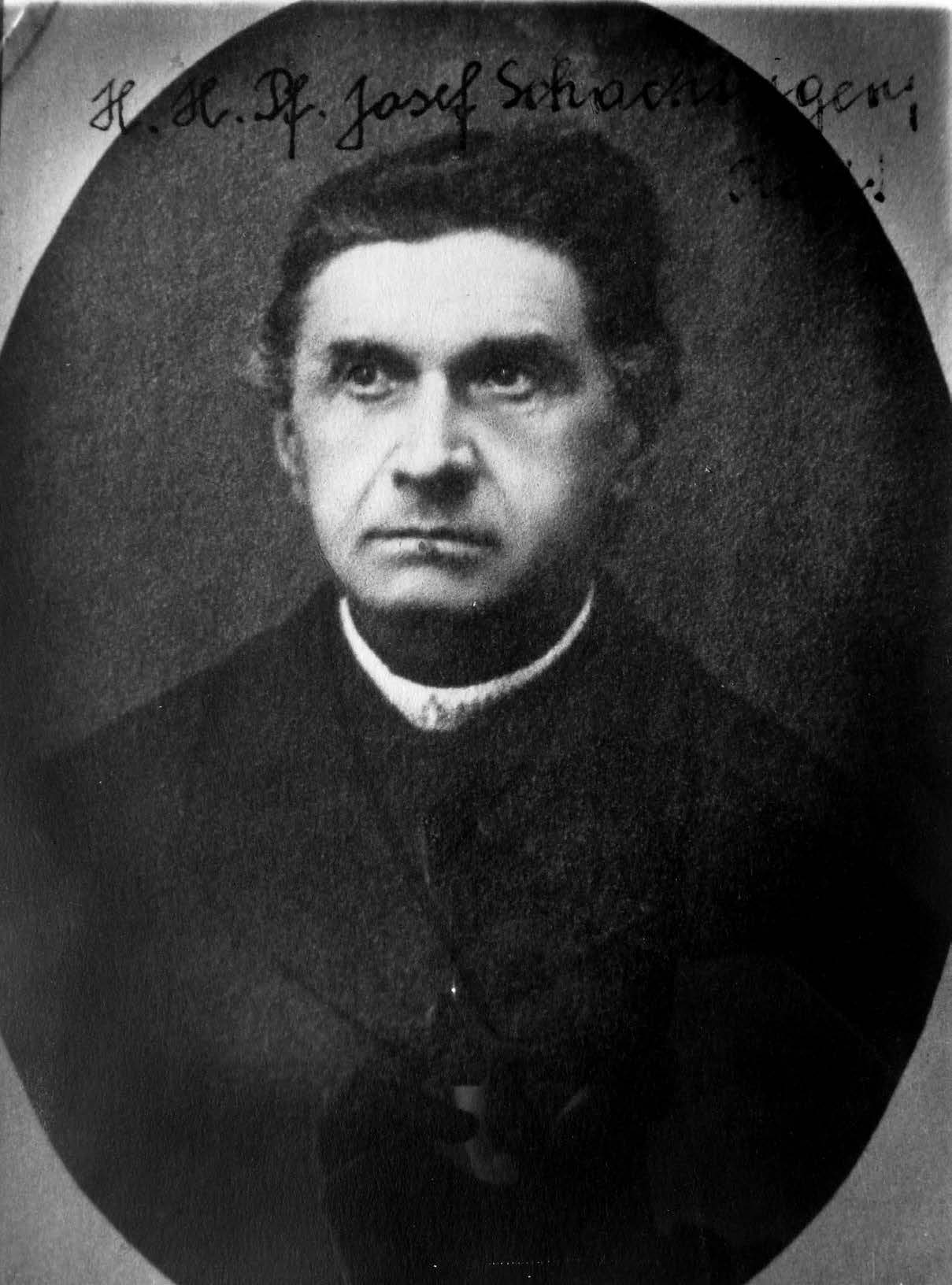

If Johann Huber wanted to get back at some of the people who had made his life miserable during the past four years, this was his golden opportunity. He named only Pastor Josef Schachinger of the Rottenbach Catholic Church, but his stories of general and specific persecution in Haag and Rottenbach were clearly accusatory. His views on Christian doctrine came through distinctly, leading Spiegel to refer to Mormonism as a kind of “away-from-Rome” movement. Like the vicious notices placed in newspapers in Upper Austria since 1899, this article likely set tongues wagging, and it is possible that some readers were sympathetic to Huber’s situation.

It is not known whether Pastor Schachinger ever saw Spiegel’s article, but he could hardly have perused it calmly. Huber was cited as saying that Schachinger’s “business was slacking off” and that the pastor was “using the most sophisticated means to intimidate him, his family and his followers.”[8] The latter comment was, of course, quite accurate; while it may have embarrassed the cleric, it did not dissuade him from his campaign against the local Mormons.

Pastor Schachinger bemoaned his problems with the Mormons in the parish history. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

Pastor Schachinger bemoaned his problems with the Mormons in the parish history. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

The suggestion that the Catholic pastor or the parish were being damaged by the growth of the LDS congregation in Rottenbach in 1904 was completely unfounded. At that time, the branch consisted of barely a dozen persons (counting children). Only about one-half of them were locals, the others having arrived from other towns in Upper Austria. Whatever their origins, these “apostates” would not be left in peace by a Josef Schachinger determined to bring them back to the fold and prevent any more departures from the Roman church.

However, the article may have brought the church a little positive attention. In late February 1904, Huber received an inquiry from an unnamed woman who requested literature about the church. Huber promised to send her what she requested, but he needed to get it from the LDS mission office first. Where that woman (whom he addressed properly as “miss,” i.e., Fräulein) learned about the Church remains unknown, but it is very likely that she saw the article by Spiegel in a major city newspaper.[9]

The Opposition Resumes and Higher Authorities Weigh in

The appearance of the Spiegel article may have represented a victory to Huber, but at the same time he may have overlooked the mettle of his numerous foes. For example, the large collection of documents that tell his story includes a note from the county office in Ried to the Rottenbach School on February 8 inquiring whether young Johann Huber missed attending church services on five specific Sundays in the previous November and December “without justification.”[10] The collection of data against the Michlmayr farmer continued unabated. Principal Binna was only too happy to supply evidence to support the charges, as was Pastor Schachinger, who was contacted by the county on February 10 with a request for similar information.[11]

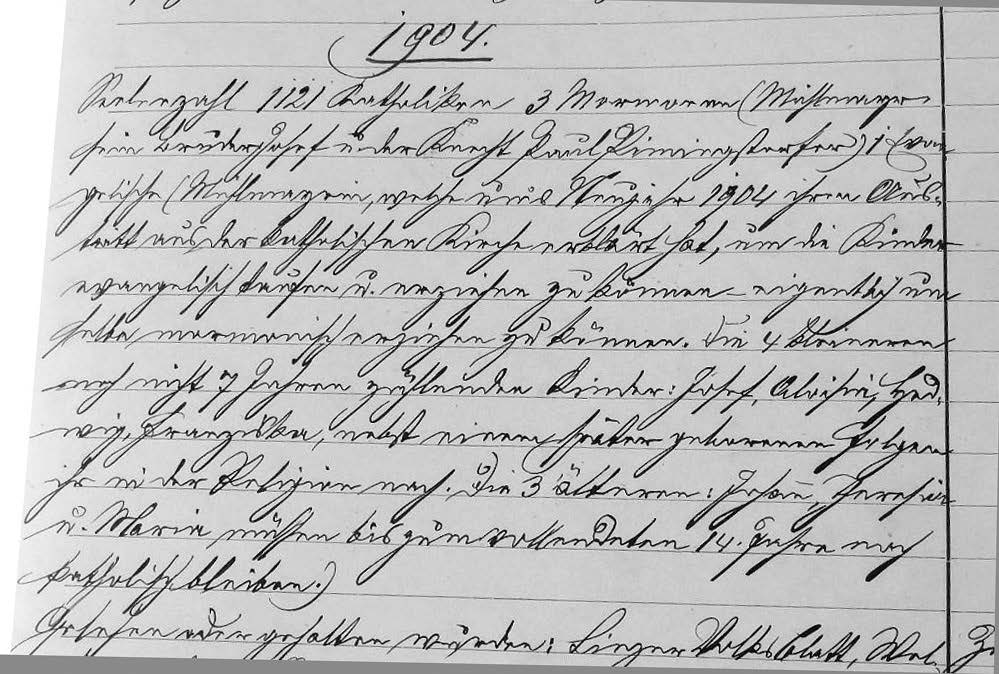

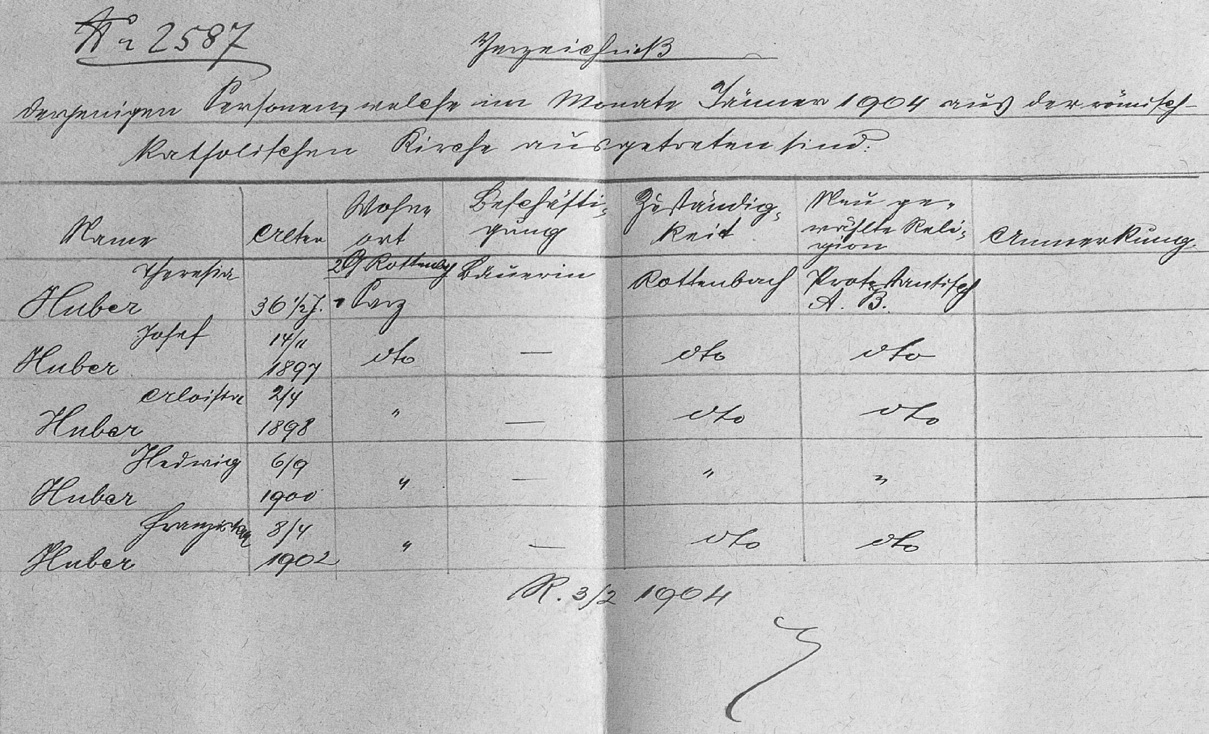

"The following persons withdrew from the Roman Catholic Church in Reid County in January 1904.

"The following persons withdrew from the Roman Catholic Church in Reid County in January 1904.

For the first time, the provincial government of Upper Austria in Linz became materially involved in this case on February 10, 1904, when it sent an edict to the Ried County Office. It is quite possible that somebody in Linz had seen the Spiegel article and felt compelled to act. The county office was instructed to investigate the activities of the Mormon “sect” in Rottenbach and Haag, the prime purpose being to determine if the imperial constitution of 1868 had been violated. The interest of the provincial government focused on paragraph 2 of article 7: “It is however forbidden for any religious group to attempt to convert persons of another religion through compulsion or deceit.”[12]

The provincial edict also mandated that county officials collect information about all persons associated with the church (name, age, and residence) and to indicate whether non-Mormon individuals were participating in worship services. Finally, the county was to append to its report all documents previously filed in the county office regarding the Mormons.

Because the Linz Catholic Diocese also brought this matter before the provincial government of Upper Austria, it is certain that Pastor Schachinger had been communicating with his superiors. Indeed, he had written to the bishop immediately after learning that Theresia Huber’s request to withdraw from the Catholic Church had been granted, lamenting that “the children are lost.”[13] The response from the diocesan office instructed Schachinger to pray for the children and to continue to encourage them to attend church. The final line of this letter suggests cautious action: “They should not be allowed to [take the sacrament] if it is feared that their attitudes will lead them to sacrilegious actions.”[14]

The decision made on February 19 by the Ried County Office represented a serious potential inroad into the private lives of local citizens. The instructions lend an ominous spirit to the campaign, communicated almost word for word from the provincial edict to the police offices of the following eight towns: Aurolzmünster, Eberschwang, Gaspoltshofen, Gurten, Obernberg, Ried, Taiskirchen, and Waldzell. The word vertraulich [confidential] was underlined in each letter. If any of the Latter-day Saints associated with Michlmayr Johann Huber had hoped to remain anonymous and thus escape persecution, that hope could hardly be realized now. But would they ever learn of this “confidential” investigation?

The response of each of the police offices named above may have disappointed the people behind this investigation, in that each office reported there were neither Mormons nor Mormon activities in their vicinity. There was no police office in Rottenbach at the time and the office in Haag received instructions that were slightly different from those given other offices. The Haag instructions cannot be found, but the response of that office to Ried is noteworthy:

In accordance with the edict issued to this office, we can report that based on our confidential investigation, the Mormon sect in Haag and Rottenbach has thus far in the exercise of their religion not overstepped the limits established by Article 16 of our national constitution. We were also not able to determine that any offense was committed against Paragraph 2 of Article 7 of the law dated May 25, 1868.[15]

The Haag police office determined that besides the six men already presumed to be members of the Mormon sect, only two other persons attended meetings in the granary at Parz 4: Huber children ages eleven and seven. Those two must have been Johann and Theresia (the two eldest), but in February 1904, Johann was eleven and Theresia was nine. The next child was Maria, age eight.

The report of Sergeant Bomer of the Haag police office was official and correct, but more important, it was merciful to the Latter-day Saints. It gave the provincial government no reason at all to make further inquiries about or take action against the little group. At the same time, it seems odd that there is no mention of any other attendees at Mormon meetings such as Mrs. Huber, the other Huber children, or the wives and children of the other men. Officially, only five men belonged to the Rottenbach Branch in 1904: Paul Haslinger, Johann Huber, Josef Huber, Matthias Huber (another brother of Johann), and Paul Pimmingsdorfer.[16]

Though the Mormons passed this test, more investigations were coming. In 1904, there were no non-Catholics in Rottenbach except for the members of the LDS Rottenbach Branch. It would seem that anytime Johann Huber attempted to practice his new religion, his actions were interpreted as offensive by local Catholics. So it happened that somebody reported to the county office that Huber was doing things that only the Catholic priest was allowed to do. The county took quick action to have the responsible police office investigate:

You will investigate and within five days submit to me a report whether Johann Huber did indeed conduct a funeral on October 10, 1903, and whether a Mormon did indeed come from Munich to conduct a funeral for Maria Haslinger who died on November 15, 1903, and to lead the funeral procession.[17]

The Haag police chief returned the requested information on March 8:

I can report that Johann Huber did in fact give a funeral sermon on October 10, 1903, at the Rottenbach cemetery for Mr. Haslinger, but I haven’t been able to determine what he said. Regarding the story that a Mormon came from Munich to conduct the funeral of Mrs. Haslinger on November 15, 1903, to lead the procession and dedicate the grave: this story is based on falsehoods. Only her husband, her daughter Marie, and an employee named Josef Huber accompanied her to the cemetery in Niedernhaag where she was buried without any ceremony. Later that afternoon after the grave had been closed, Johann Huber went to the cemetery in Niedernhaag with a stranger who is believed to be a journeyman carpenter from Munich and read aloud from a book there.[18]

Due to increased official interest in the activities of the Mormons in Rottenbach and Haag, the county office sent another edict to the local police offices mentioned above. The newest instructions were to keep an eye out for the activities of the members of that sect and especially to ensure that the Mormons were not publicly attacking the Roman Catholic Church.[19]

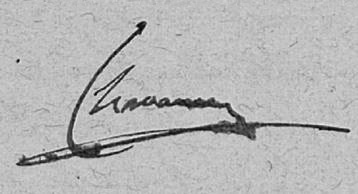

The signature (above) and rubber stamp (below) used by August Elder von Chavanne on county documents.

The signature (above) and rubber stamp (below) used by August Elder von Chavanne on county documents.

On February 19, 1904, a letter went out over Commissioner Chavanne’s signature initiating an impatient exchange. To the question, “Why didn’t we get a report right away about Johann Huber giving a funeral sermon for Alois Haslinger?” came the Haag police answer, “We just found out about it ourselves!”[20] The county official was determined to keep abreast of events. The most interesting aspect of the six-page communication that began with this question is the description of Johann Huber offered by another county employee:

Finally, regarding a description of the person of Johann Huber, I can offer the following: In general, he is known as a person who is under great religious stress. His farm is characterized by the greatest order and cleanliness and his employees have never made any charge against him for poor treatment.[21]

Another dispatch left Chavanne’s office on March 14, 1904, indicating that the only Mormon activities known to be taking place in Rottenbach were the worship services in the Michlmayr granary. This dispatch was sent to the Linz Provincial Office, the police offices of Haag and Gaspoltshofen, and the Catholic parish offices in Haag, Rottenbach, Gaspoltshofen, and Wendling.[22] The addressees were to report without delay any misbehavior on the part of the Latter-day Saints. With this directive, the county seems to have taken a break from this matter—but for just two weeks.

The Monumental Decision

Throughout the month of April 1904, the battle over the status of Mormon Johann Huber raged in various courts in Upper Austria. Surviving documents attest to the constant transfer of court rulings and requests for supporting documentation from office to office. Rulings were frequently appealed to higher courts. On April 2, the Haag County Court ruled that schoolchildren could not be required to attend church services, so Huber could not be charged with interference. Thus the plaintiffs suffered a serious defeat.

However, investigations into Mormon activities in Rottenbach and the surrounding region continued. On April 14, 1904, the county office sent a report to the diocesan office in Linz in response to the latter’s inquiry dated January 12:

We have the honor to report that the matter is being investigated and the appropriate directions have been issued. . . . According to our investigation, the members of this sect have not violated the statutes of Article 16 of the law of December 21, 1867. Nor has it been determined that members of the Mormon sect have attempted by compulsion or deceit to enlist converts from Christianity. . . . The county office in Ried has issued the appropriate instructions to see that the Mormons within their jurisdiction are watched.[23]

It is important to note that this is the only document in the existing collection that suggests that Mormonism was not a Christian faith. However, it is possible that the diocesan letter of January 12 (not extant) made such a suggestion and that the provincial office simply employed the same verbiage in response.

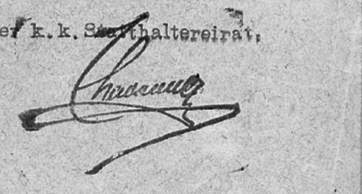

Another serious defeat to the anti-Huber forces came when the Wels Appellate Court ruled on April 30 that Huber could not be divested of his parental rights. The justification of the ruling was explained in the following text:

His personal religious views will only be of consequence if Johann Huber disturbs the religious instruction in school by the way he teaches his children or if he truly influences them in some other way. The father Johann Huber has stated repeatedly that he will not personally exercise influence over his children regarding religion. He is not opposed to his children attending church or participating in Catholic instruction. None of the witnesses could contradict this statement. As long as no facts can be presented to show that religious instruction has been interrupted or participation in the required religious activities hindered, the mere suspicion that the father is exercising damaging influence (while at the same time witnesses have attested to excellent conditions in the family and the raising of the children) does not warrant the revocation of the father’s parental rights.[24]

This ruling marked the end of the frequent attempts by Huber’s opponents to remove the children from his home. The fight lasted just five days short of a year with the result up in the air most of that time. The Huber family and their Mormon friends had a lot to celebrate that day, and the arrival of an offensive message from the county office just days before likely did little to dim the celebration on April 30:

In consideration of the ruling of the county court on April 14, 1904, file no. 6048/

IV, you are hereby informed that children required to attend school are specifically forbidden from being involved in the religious activities of the Mormons.[25]

Young Johann Huber

In April 1904, young Johann Huber was still a member of the Catholic Church because the imperial law prevented his parents from transferring to another church any child between the ages of seven and fourteen years. However, now that the parents and the younger children could not be compelled to be involved in any activity connected with the Catholic Church, why would Johann willingly attend mass and catechism and show interest in confirmation? As the heir apparent to the Michlmayr farm, he would never need confirmation to qualify for employment and his father would certainly oppose any such public statement of loyalty to the Catholic Church. As it turns out, the voluminous document collection contains no record that Johann ever participated in first communion.

The Wels Court clerk had a most consistent and uniform alphabet all his own. His complex syntax reflected the hihgfalutin style of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The Wels Court clerk had a most consistent and uniform alphabet all his own. His complex syntax reflected the hihgfalutin style of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

On May 1, 1904, Pastor Schachinger brought up another matter in reference to young Johann, namely that he was not to be moved to the Lutheran Church with his mother, but was required to remain Catholic until his fourteenth birthday. In his letter to the bishop in Linz, Schachinger asked for advice regarding having young Johann participate in communion with the other pupils of the class of 1893.[26]

The response from the diocesan office in Linz reminded Schachinger that based on the county ruling and the imperial law, none of the Huber children could be forced to participate in communion.[27] The bishop may have hoped that the Rottenbach priest would give up his battle against the Huber family, but Schachinger (despite his ongoing and nearly debilitating physical maladies) was not prepared to surrender.

Mormons in the News Again and More Police Investigations

In the summer of 1904, things were looking better for the Huber family. However, stories about the Mormons in Rottenbach were just too salacious (whether factual or erroneous) to be left alone. On July 1, the following notice appeared in the Oberösterreichische Volkszeitung:

Hohenzell, June 25. (Mormons) We have heard from Mrs. Granitz that Mormon meetings or lectures have been held several times in the home of farmer Hans in Brennigsham [sic], St. Marienkirchen Parish. The movement supposedly began with Michlmayr, a Mormon farmer in Rottenbach, who is already well known. One of his compatriots, a turner from Rabental, Pram Parish, went to work for farmer Hans during the hay harvest. We hear that he has been preaching (sometimes until late into the night) his Mormon doctrines and has been trying to make converts for Mormonism there and at other locations. It is known that the Mormon sect is not legally recognized in Austria because the Mormons teach polygamy and other doctrines. If government officials only cast a disinterested eye on these happenings, you Catholics will have to help yourselves! Just kick out these missionaries of an insane Mormon doctrine! We will save a few interesting items for a subsequent report.[28]

That bold but self-proclaimed missionary was not initially identified nor his treatment in Hohenzell described. However, the article was followed soon by a similar message in a Linz newspaper. The latter consisted of no fewer than fifty-six lines and expressed its goal to be the verification of the Ried report. The scandalous story featured the following details: a local farmer tricked the Mormon into the barn with the offer of letting him marry his daughter (as his first wife, because the Mormons believe in polygamy). However, it turned out that the Mormon was of a lower social class and thus not worthy of her. He then found work from another farmer in need and once in the home, revealed himself to be a Mormon missionary looking for converts. He was joined there by Michlmayr Johann Huber from Rottenbach, who volunteered to lay his hands on the head of an old woman who had suffered from paralysis for five years; he would heal her if she converted to Mormonism. Both men were then thrown out of the home. The long article ends with a hopeful message for Catholics: “Good Catholic literature is found in the homes they visited. We don’t need to worry about the people of [Breiningsham].”[29]

These articles came to the attention of the Ried County Office, thanks in part to Pastor Schachinger, who forwarded the Linz story to the commissioner “to show you what methods and means are used by Michlmayr to spread Mormonism.”[30] Instructions were sent to the Ried District Police Office that the veracity of the story should be checked out.[31] From there, the assignment went to the police office in Haag, where an officer claimed that the offending Mormon was, in fact, “the Johann Tischler named in the article.”[32] However, he was in error because neither article provided the Mormon’s name. The offending stranger was likely Ferdinand Kussberger, who was identified in Rottenbach as Huber’s associate and a turner by trade.

The scandal in Breiningsham was still in the public eye in July 1904. The district police commissioner in Ried contradicted his Haag counterpart with a lengthy report to the county dated July 11. The former had sent an agent named Anton Gierer to speak with the owner of the Hans farm in Breiningsham, a Mrs. Dürnberger, and learned that the offender was a man by the name of Ferdinand Kussberger. No Mormon meetings had been held, and Kussberger had made no overt effort to convert the locals to his faith, but he had told Mrs. Dürnberger that a farm laborer named Johann Tischler was to be baptized within the next two weeks at a location near Wels or Grieskirchen. Agent Gierer went to the home of Kussberger’s parents and pretended to be interested in Mormonism. They gave him three pieces of Mormon literature and told him that their son claimed to attend services at the Michlmayr farm nearly every Sunday. A sacrament service was said to take place in a special room there once each month.[33]

With county police agencies now well informed, instructions were issued to the local offices to monitor the distribution of Mormon literature.[34] The best information was submitted by the police office closest to Rottenbach, namely in Haag:

In response to your directive of the 4th inst. (no. 13.342), we can report that on the part of Mormon Johann Huber alias Michlmaier [sic] in Parz, town of Rottenbach, there have been no attempts of late to convert people. However, we did receive an inquiry for more information on this topic from the police office in Gallspach, Wels County. Attempts were being made there to spread Mormonism. Johann Huber is holding weekly religious services in his grainary [sic], but we don’t know any details about those services because non-Mormons have never participated. According to individuals who have walked past the building, they heard people singing hymns and praying. We haven’t been able to determine a precise reason why Matthias Huber alias Schusterbauer (a resident of Reischau and brother of Johann Huber) and turner Ferdinand Kussberger of Rabenthal, Pram Parish, converted to Mormonism. Matthias Huber probably joined because of his brother. The locals are making fun of Kussberger for joining the Mormons; he apparently did so because Johann Huber promised to buy him a work bench. It appears that all Mormons mentioned above have good reputations—except for their religious activities. Regarding Johann Tischler, the man mentioned in the report of the police office in Ried, nobody around here knows anything about him. In any case, he isn’t living within our jurisdiction.[35]

As far as the officials were concerned, the Mormons in Rottenbach did not represent any danger to the peace of the community—at least for the moment.

The Hubers may have been totally unaware of the investigations into their activities in the summer of 1904. They were quite busy with the usual farm work and with Theresia’s recent withdrawal from the Catholic Church. This was finalized in August when the Protestant Church in Wallern confirmed receipt of the necessary documentation from the Ried County Office. The four youngest Huber children were also named in the transfer certificate.[36] In Catholic Upper Austria, Wallern was the closest Protestant parish, but it was still twelve miles east of Rottenbach. There is no evidence that Theresia ever proposed to attend church so far away—even on high holy days. Although we cannot know what was in her heart at the time, she had expressed the hope (cited above) that this change would relieve her children from the pressure under which they suffered at school (and at the hands of an unfriendly Rottenbach pastor). It remains to be seen whether this outcome was actually achieved.

At the same time, we cannot determine what Frau Huber thought of her husband’s church with its doctrines and practices. The police reports cited above indicate that she did not attend Mormon services held in the granary just a few steps from her own kitchen. Could this have been true over the years? Would she have been so devoid of curiosity that she never attended even one of those services?

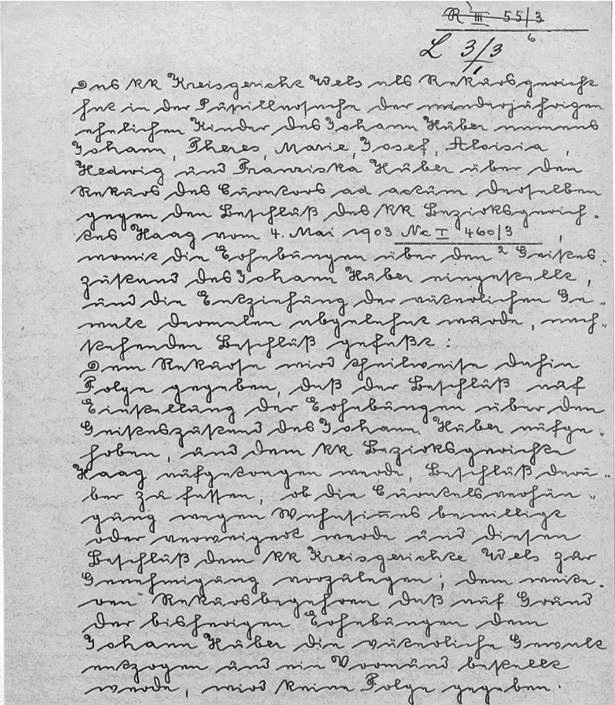

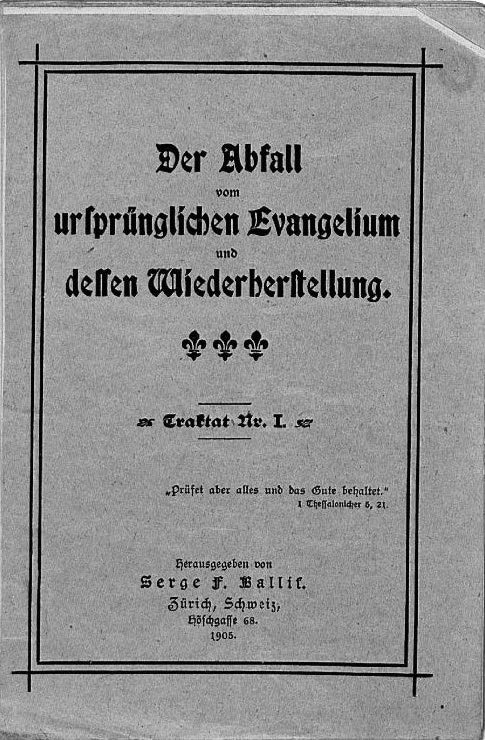

LDS pamphlet presented in evidence in the trial of Johann Huber: The Apostasy from the True Gospel and Its Restoration.

LDS pamphlet presented in evidence in the trial of Johann Huber: The Apostasy from the True Gospel and Its Restoration.

The battle continued over Huber’s proselytizing, both perceived and real. On July 10, 1904, Josef Schachinger submitted a complaint to the Ried County Office, insisting that Huber was again preaching his gospel in and around Rottenbach: “I am sending you the article in the Linzer Volksblatt that explains how the Mormon sect and Michlmayr are attempting to spread their religion.”[37] The county promptly investigated the claim. While it is true that none of the nine police offices asked to monitor Mormon activities reported that any were detected in their districts, the indomitable Michlmayr Johann Huber was often on the road preaching the restored gospel. Having done so in the town of Meggenhofen (six miles east of his home), Huber was charged with a crime. The District Court in Wels took little time to reach a legally tenable verdict of guilty and to impose a fine of ten crowns, as stated in the ruling of August 16, 1904:

The sentence is justified because the defendant, Johann Huber, confessed to having distributed without official permission the literature in question on June 6, 1904, in Meggenhofen in connection with a funeral. Said literature was designed to attract members for the Mormon Church and the persons among whom the literature was distributed had not been warned. As stipulated in Par. 23 P.G., the content of the literature is of no importance in this case. The sentence was mild due to the fact that the defendant confessed the deed and had not been convicted of any previous crimes. No additional charges were brought. The sentence is otherwise in direct correspondence with the law cited.[38]

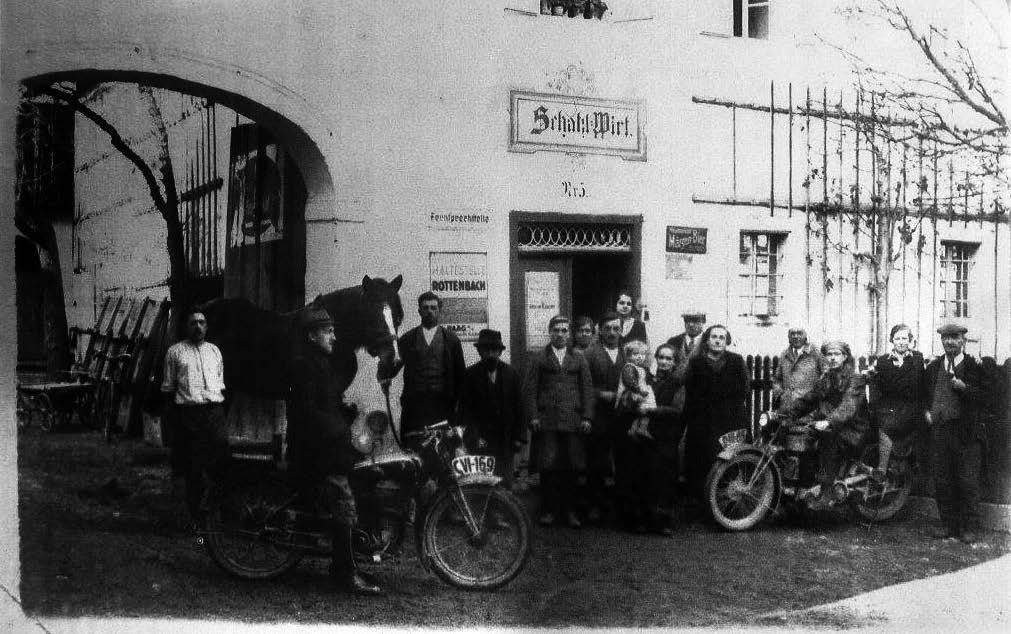

Huber preached his Mormon gospel in such places as the Schatzlwirt Inn on many occasions.

Huber preached his Mormon gospel in such places as the Schatzlwirt Inn on many occasions.

A week earlier, Huber had submitted to that court a request that sixteen witnesses—by name—be called to testify on his behalf. The request was denied because “the accused did not provide details regarding the testimony to be given by those witnesses in contrast to his own confession.”[39] It is likely that Huber asked those witnesses to testify to the fact that he had not attempted to convert them to his new faith. As could be expected, he didn’t pay the fine, and the court warned him on August 27 to do so within ten days (without specifying a penalty for noncompliance).[40] The official sentencing record shows that Huber was fined ten crowns and sentenced to twenty-four hours in jail. The records do not show that either penalty was enforced.[41]

Apparently the fact that Johann Huber confessed to distributing his literature put the Ried County Office on alert. A directive was sent to the Ried police station on August 29 that the activities of the Mormons (specifically the “spread” of Mormonism) were to be most carefully monitored and any activities observed reported immediately to the county office.[42] A week later, the same office issued an order to county police stations regarding the Mormons. Citing their directive of March 14, 1904, the county required the same nine police offices to watch out, because “not only has a leader of the Mormon faith been distributing literature very recently, but lectures have been given in public houses.”[43] As before, the investigations were to be conducted “confidentially.” Emphasizing the worries that had been reawakened among government agencies near Rottenbach, that directive went through a broad distribution:

1. to the town hall in Aistersheim, Gaspoltshofen, Geboltskirchen, Geiersberg, Haag, Pram, Rottenbach, Weibern, Wendling, and Hohenzell,

2. to the county police office in Ried,

3. to the Catholic Parish offices in Haag, Rottenbach, Gaspoltshofen, and Wendling,

4. to the Catholic Parish offices in Aistersheim, Geboltskirchen, Geiersberg, Hohenzell, Pram, and Weibern,

5. to the public schools in Aistersheim, Gaspoltshofen, Hohenzell, Geboltskirchen, Geiersberg, Haag, Pram, Rottenbach, Weibern, and Wendling.[44]

The directive dated September 4, 1904, initiated a regional search for Mormon adherents and activities. The territory under investigation measured approximately ninety square miles and included exclusively farming communities. With letters going specifically to thirty-one offices, it is easy to imagine that village gossip soon informed willing listeners of what could quickly become a witch hunt.

A Friend of the Mormons

As might be expected among any population, not everybody opposed Johann Huber in the question of religion. Seemingly out of nowhere, a man surfaced in the fall of 1904 to speak boldly in favor of the Michlmayr farmer. Identified only as “Master [Mathias] Pramerdorfer,” he wrote to Schachinger on September 3, 1904. He began by quoting the New Testament verses about ravenous wolves misleading people and hypocrites who do wrong things in the name of God, then expressed his gratitude that Johann Huber had attempted to save him. His letter continued:

Regarding what you wrote to me about Michlmayr, I know that what you did was done in love and patience, but your kind of patience is a different one because you came on like an angry rooster. Usually politeness reaps politeness. You see, Pastor, the shepherds often have dogs that bark too loudly at the sheep and even bite sometimes when they should just bark. How can one wonder if a sheep then jumps out of the pen and runs away from the flock?[45]

He next offered a defense of Mormonism:

Who can doubt the pure gospel of the Latter-day Saints? I can’t understand how you as a learned theological scholar could believe the basic premise that only the Catholic Church can save a person. How many souls will be perishing in outer darkness, not ever having heard anything about the gospel of Jesus Christ during their earthly life?[46]

After mentioning his belief that people who died without a knowledge of Christ would receive such knowledge in the next life, Pramerdorfer challenged the practice of infant baptism:

Pardon me, but I have to tell you that it’s an abomination in the eyes of God to baptize infants. It’s impossible for an infant to repent; an infant can’t sin. He’s totally dependent upon his parents. Furthermore, baptism is a symbol for death from which a person is born again, endowed with the Holy Ghost.[47]

His final comment reads like a condemnation: “If you say that we [the Latter-day Saints?] don’t have the doctrine and the pure gospel, I must respond that you don’t have the right one at all. . . . By the way, I just have to add that there are more fake Catholics than real Catholics.”[48]

Several months later, Schachinger reported to the bishop that he had written two letters in response to Pramerdorfer’s claims; he stated that Pramerdorfer had threatened to leave the Catholic Church, but had yet [March 1905] to do so.[49]

Pramerdorfer’s letter had made at least a small impression on the priest. Of course, Schachinger was neither distracted from his belief in Catholic doctrine nor weakened in his ongoing opposition to Mormonism within his parish. On September 14, 1904, he wrote to the county office in Ried:

In response to your directive of September 5 inst., the undersigned can report that currently a Mormon turner Ferdinand Kusberger [sic], a resident at the Schindlhamer farm in Poppenreith, is very active in spreading Mormonism. I have discovered that a certain Mathias Pramerdorfer alias Schettermacher Hiahl is a Mormon even though he has yet to declare his withdrawal from the Catholic Church. He is living with the blacksmith named Pimmingstorfer at Gotthanning in the Haag Parish. He’s all the more dangerous because he can write well and produce essays. His past life is said to be quite evil.[50]

Not far behind with his report was the police official in Haag. He confirmed Schachinger’s assertion that Kussberger was a Mormon living in Poppenreith near Rottenbach and provided this detail about his activities: “Several laborers have met with him on occasion, specifically Gabriel Auleitner and Engelbert Partinger. When interrogated by me, the former indicated that though Kussberger often talked about his religion, he made no attempt to convert anybody.”[51] The police office in Ried confirmed the statement regarding Kussberger.[52]

The typical Austrian postman in about 1900. One wonders if such men feared approaching the Michlmayr farm. http://

The typical Austrian postman in about 1900. One wonders if such men feared approaching the Michlmayr farm. http://

Having received the instructions about monitoring Mormon activities, Principal Karl Binna of the Rottenbach School again added his comments to the fracas. On October 23, 1904, he wrote the following to the Ried School Board in a remarkably unbiased tone:

I have learned through very discreet investigation that strangers have gone to the Michlmayr home in the evenings, probably to talk about Mormonism. The five Huber children who attend school are relatively unfriendly in their dealings with the teachers. When asked why they don’t attend church services, they give evasive answers or none at all. I’m not the kind of man who will say bad things about parents or children, but those children are definitely hearing and seeing things in their parents’ home that aren’t good for them. . . . I’ll continue to monitor related conditions here for you.[53]

Pastor Josef Schachinger of the Rottenbach Catholic Parish had lost the battle to keep the four youngest Huber children in the Catholic Church, but he could still make life difficult for the three eldest: Johann, Theresia, and Maria. On October 24, he brought up for the first time in seven months the matter of young Johann missing church services on four recent Sundays. Schachinger asked him about his absence and young Johann gave an unacceptable excuse. The priest wrote:

[I] informed Michlmayr of this in writing and reminded him that the Sabbath is not the day to herd cattle. If the boy truly must herd the cattle, at least he could attend the early Sunday service. But the boy was absent again on October 12. When the vicar asked him why he didn’t attend, he gave a haughty answer, “I had to herd the cows.” This allows the assumption that Michelmayer [sic] can’t be expected to cooperate unless he is punished.[54]

A Public Mormon Baptism

By now, Johann Huber was not the only Mormon whose activities were causing a ruckus in the vicinity of Rottenbach and Haag. Johann Tischler had eluded officials during the secret investigations of the fall of 1904 and was baptized a Mormon in late October. Two fascinating reports regarding this event were filed with the Ried County Office. Haag Police Chief Franz Bomer gave this detail:

It is reported that Johann Tischler has been thinking about converting to Mormonism for the past two years. He has been supported in this plan by Johann Huber alias Michlmayr of Parz 4. Tischler has worked for him during the current harvest season. The baptismal ceremony took place in a pond constructed for this purpose in the Rottenbach Creek in this manner: The baptist, Meslim [Winslow] Smith, and the convert were clad in nothing but shirt and underwear when they entered the water. The baptist gave the convert a light push so that he fell backward into the water, then the former pulled him out of the water and the baptism was completed.[55]

The clerk in the Rottenbach town hall added this detail after giving the date of the event as October 23: “Local Mormon leader Johann Huber arrived in a wagon with a Mormon apostle. Johann Tischler was required to put on two shirts and then the apostle baptized him. When he came out of the water, the evil spirit departed from him, or so he told another farm laborer in Parz.”[56]

The “apostle” was LDS missionary Winslow Smith, visiting from Munich, Germany. Neither report indicated that the baptism was done in secret or at night, but apparently there were few witnesses to the event. The mode of baptism differed in nearly every conceivable way from the ceremony performed in the Catholic Church and was likely a topic of discussion among farmer and laborer families for miles around.

The town hall report of Tischler’s baptism took three pages and listed other odd events and incidents associated with the Mormon movement. For example, “numerous complaints” had been received that people visiting the Michlmayr home had been confronted with Mormon literature, and arguments with Johann Huber had ensued. Visitors were told that Mormonism was the only true religion. Finally, the writer listed a few other persons in nearby towns who had been approached by missionary Huber and concluded with this request: “The town hall of Rottenbach asks if there is anything the county can do to stop the activities of Johann Huber.”[57]

On the same day, the Ried County Office instructed the Haag District Court to initiate legal action against Johann Huber for possibly breaking religious laws by participating with a “Meslim” Smith in the baptism of Johann Tischler. County commissioner August Edler von Chavanne had read the two reports regarding the baptismal ceremony in Rottenbach and inquired—quite correctly—whether the event violated Article 16 of the Austrian constitution of December 21, 1867, that dealt with rights of home religious worship. Chavanne also instructed the county to study paragraphs 23 and 304 of the civil code.[58]

On December 27, 1904, a new player arrived on the scene of this six-year-old religious controversy: the Wels district attorney. On that day, he wrote a letter to the county office in response to the county’s instructions that have not been preserved:

I understand it to be my charge to determine whether the Mormon sect (the so-called Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) has previously been declared to be not recognized by the Ministry of Culture and Education and if so, under what ruling, or whether this sect—though not officially recognized—is not specifically classified as not being allowed. Based on the Handbuch für den politischen Verwaltungsdienst (Mayer, 5th edition, 1898, volume 4, page 37), the Mormons are not specifically listed among the religious groups that are forbidden. Thus the principal question is whether the Ministry of Culture and Education has since then [1898] issued a new ruling forbidding the Mormon sect.[59]

On the penultimate day of 1904, the county office responded to the district attorney and officially accepted his clarification of the status of the Mormon sect in Austria.[60] This interpretation of the law was of critical importance to Michlmayr Johann Huber and his friends; had the ruling been to the contrary, the county would likely have taken action to shut down the LDS Rottenbach Branch, cancel all Mormon meetings, and punish anybody attempting to preach the Latter-day Saint gospel in public or in private. Indeed, this positive ruling may have served to embolden Johann Huber and his fellow Mormons at the conclusion of a long and arduous year that saw them under attack from all sides on nearly a weekly basis.

Catholic Priest Josef Schachinger was Huber's prime opponent in the early days of the LDS Rottenbach Branch. Courtesy of Rottenbach Catholic Parish.

Catholic Priest Josef Schachinger was Huber's prime opponent in the early days of the LDS Rottenbach Branch. Courtesy of Rottenbach Catholic Parish.

For reasons unknown, Johann Huber did not carry out the baptisms of his friends during these years of dispute; a missionary was dispatched from Munich on each occasion. Whether it was the LDS mission president or Huber himself who made this decision, it was definitely a wise one. Had Huber been the baptizer, local Rottenbach witnesses might have accused him of according himself the same status as a Catholic priest—a man trained for years in a seminary and officially ordained by the Roman Catholic Church to conduct such sacred ordinances. Although Huber had been ordained a priest in the Aaronic Priesthood of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints just a year after his baptism, nobody outside of the church could possibly have considered him equal in status to the priest of a Catholic parish.

Following the recent contests regarding infant baptism, confession for school children, transfer to the Lutheran Church, proselytizing efforts, and public baptisms in a highly unconventional manner, Johann Huber and his few LDS friends were still standing. But could they survive additional attacks against what they perceived to be a peaceful movement sanctioned by heaven?

Notes

[1] Gerlinde Huber Wambacher, interview, September 21, 2011, interviewed by Roger P. Minert. None of the surviving documents suggest that any such event ever occurred. Given the ongoing involvement of so many official agencies in this case, it is inconsistent to believe that police action would be taken on Sunday or that Huber’s neighbors would instigate invasive action against him.

[2] Martin Ganglmayer to Johann Huber, January 6, 1904, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection, Rottenbach, Austria.

[3] Martin Ganglmayer to Johann Huber, January 6, 1904, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[4] Wels Appellate Court Ruling, January 27, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[5] Johann Huber maintained copies of many letters he wrote to various offices, including handwritten copies of letters he sent to newspaper editors. Gerlinde Huber Wambacher and Wilhelm Hirschmann private collections.

[6] Else Spiegel to Johann Huber, January 21, 1904, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[7] Else Spiegel, Salzburger Volksblatt, February 6, 1904, 17–18.

[8] Else Spiegel, Salzburger Volksblatt, February 6, 1904, 17–18.

[9] Johann Huber to unnamed “Miss,” February 1904, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[10] Ried County Office to Rottenbach Elementary School, February 8, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[11] Ried County Office to Rottenbach Catholic Parish, February 10, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[12] “Gesetz vom 25. Mai 1868,” Artikel 7, Reichsgesetzblatt, ALEX Historische Rechts-und Gesetzestexte Online.

[13] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, February 7, 1904, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[14] Linz Diocesan Office to Josef Schachinger, February 9, 1904, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[15] Haag Police Office to Ried County Office, February 29, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[16] Record of Members, LDS Rottenbach Branch, 1883–1923, microfilm no. 38866, Family History Library, Salt Lake City.

[17] Ried County Office to Haag Police Office, March 2, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[18] Haag Police Office to Ried County Office, March 8, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach. The description of “journeyman carpenter” had been used on previous occasions to refer to Haag native Martin Ganglmayer, but he was already home in Salt Lake City at the time, so the missionary mentioned here had to be another man.

[19] Ried County Office to Aurolzmünster Police Office and others, March 14, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[20] Ried County Office to Haag Police Office, March 2, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[21] Ried County Office to Haag Police Office, March 2, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach. Oddly enough, an unknown reader later struck out the words “and cleanliness.”

[22] Ried County Office to Haag Police Office and others, March 14, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[23] Linz Upper Austria Provincial Office to Linz Diocesan Office, April 14, 1904, Diözesanarchiv Linz, CA/

[24] Wels Appellate Court Ruling, April 30, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen, GB Haag XI E 1904 Mormonen in Rottenbach. A witness named Weidenholzer stated that his property was adjacent to the Michlmayr farm in Parz.

[25] Ried County Office to Johann Huber, April 21, 1904, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[26] Eight years of public school attendance were required, after which many of the boys entered full-time training programs in the crafts, and many of the girls entered into similar training or domestic service. A few youths enrolled in secondary schools.

[27] Linz Diocesan Office to Josef Schachinger, May 3, 1904, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[28] Oberösterreichische Volkszeitung, July 1, 1904, 5.

[29] Linzer Volksblatt, July 9, 1904, 3..

[30] Josef Schachinger to Ried County Office, July 10, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[31] Ried County Office to Ried District Police Office, July 11, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[32] Ried County Office to Ried District Police Office, July 11, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[33] Ried District Police Office to Ried County Office, July 11, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach. Church records show that a Ferdinand Kussberger (born 1870) was baptized in Rottenbach in 1922. Record of Members, LDS Rottenbach Branch, 1900–, microfilm no. 38866, Family History Library.

[34] Ried Police Office to Ried County Office, July 16, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[35] Haag Police Office to Ried County Office, July 15, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[36] Wallern Protestant Church to Theresia Huber, August 1, 1904, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[37] Josef Schachinger to Ried County Court, July 10, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[38] Wels District Court Ruling, August 16, 1904, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[39] Wels District Court Ruling, August 10, 1904, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[40] Wels District Court to Johann Huber, August 27, 1904, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[41] Wels District Court Ruling, August 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[42] Ried County Office to Ried Police Office, August 29, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[43] Ried County Office to Aistersheim Town Hall and others, September 4, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[44] Ried County Office to Aistersheim Town Hall and others, September 4, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[45] Mathias Pramerdorfer to Josef Schachinger, September 3, 1904, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[46] Mathias Pramerdorfer to Josef Schachinger, September 3, 1904, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[47] Mathias Pramerdorfer to Josef Schachinger, September 3, 1904, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[48] Mathias Pramerdorfer to Josef Schachinger, September 3, 1904, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[49] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, March 3, 1905, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[50] Josef Schachinger to Ried County Office, September 14, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach. The county report of March 12, 1909, lists Pramerdorfer as a Mormon, but no such person is found in the LDS Rottenbach Branch records.

[51] Haag District Police Office to Ried County Office, September 27, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach. The writer of this report indicated that two men known to speak with Mormons were of the most questionable character, one of them having been convicted of misdemeanors twelve times.

[52] Ried District Police Office to Ried County Office, October 5, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[53] Karl Binna to Ried County School Board, October 23, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried X L 1904.

[54] Josef Schachinger to Ried County Office, October 25, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[55] Haag Police Office to Ried County Office, November 9, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[56] Rottenbach Town Hall to Ried County Office, November 8, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[57] Rottenbach Town Hall to Ried County Office, November 8, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[58] Ried County Office to Haag District Court, December 21, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[59] Wels District Attorney to Ried County Office, December 27, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[60] Ried County Office to Wels District Attorney, December 30, 1904, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.