A Ruckus in Rottenbach (1899)

Roger P. Minert, Against the Wall: Johann Huber and the First Mormons in Austria (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 1–16.

As the nineteenth century approached its conclusion, Michlmayr Johann Huber (known by the name of his farm, Michlmayr) was in an excellent position to enjoy the life of an estate farm owner. As perhaps the wealthiest resident of the little town of Rottenbach, Austria, he had enough work not only to keep his growing family busy, but to require him to employ several young men and women from local families and neighboring towns as temporary laborers. Johann’s economic and social prospects were good, and he was proud to be a citizen of one of the greatest empires in Europe.[1] But it was not the local or national economy that would cause him grief in the coming decade—rather, it would be matters of faith and religion. In a matter of weeks, the peace on the Michlmayr farm would be dispelled and Huber’s security threatened.

In the spring of 1899, an election was approaching—the interim election of a replacement representative to the parliament of the province of Upper Austria. Despite the fact that Emperor Francis Josef I was still secure on his imperial throne in Vienna (after fifty-one years), many parties existed across the political spectrum and enjoyed official legal status; one of those was the German National Party. By virtue of Huber’s association with that party, he was numbered among the liberals in Rottenbach.

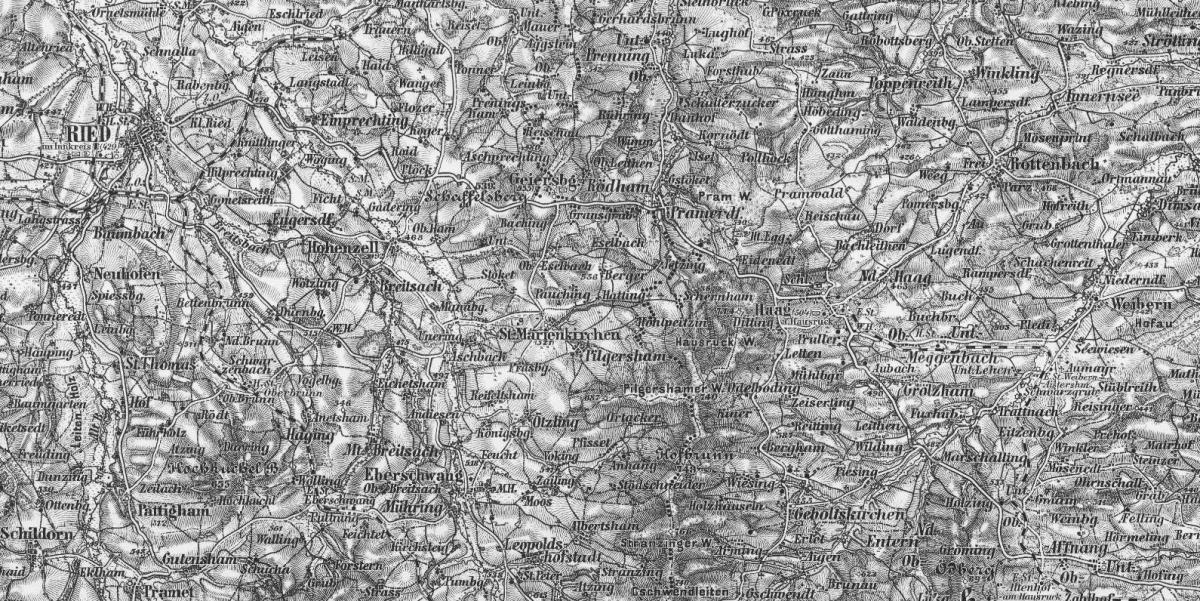

This part of the province of Upper Austria includes most of the territory where Johann Huber lived and worked-principally the towns of Rottenbach and Haag. The county seat of Reid is shown at upper left.

This part of the province of Upper Austria includes most of the territory where Johann Huber lived and worked-principally the towns of Rottenbach and Haag. The county seat of Reid is shown at upper left.

Johann Huber as a Liberal

Liberalism had existed in Austria since the time of Napoleon, despite setbacks suffered in the abortive popular uprising in Vienna in 1848. According to Jonathan Kwan, “in the period of Austria’s first long-term parliament, from April 1861 to September 1865, the liberals passed important laws and installed new institutions.”[2] It was a time of great upheaval, when Austria was expelled from the German League after the Imperial Army was soundly defeated by the Prussians at Königgrätz in 1866. Liberalist ideals became so popular that the Liberal Party achieved the majority in the national government in 1867. All cabinet members were liberals, and they led the movement that produced a new constitution for Austria in 1867–68. The three main planks in the Liberal platform were a unified state under a strong central government, universal rights coupled with bourgeois values, and a nation dominated in all respects by the German language and culture.[3]

The liberal movement was in direct contradiction to the traditional power of the Catholic Church that had been reaffirmed through the Concordat of 1855.[4] That contract solidified the relationship between the Catholic Church (in the person of Pope Pius IX) and the Austrian Empire (represented by Emperor Franz Josef I). With an almost total disregard of any other religion, the concordat granted important protections to the Catholic Church and its officials all over Austria, including control over public schools.[5] In return for this preeminent religious status, Catholic parish priests were required to swear an oath of loyalty to the emperor.[6]

But the new Austrian constitution of 1868 caused the Catholic Church to suffer serious setbacks in such areas as civil marriage and the public school system (thus nullifying most of the provisions of the concordat).[7] Then, despite what appeared in 1870 to be powerful position for the liberals, political fortunes suddenly reversed across Austria, and the Liberal Party suffered a crippling loss in the election of 1879.[8] By the 1890s, the party had declined to the point that those espousing liberal philosophies found it advantageous to establish a new organization called the German National Party. Their concept of nationalism fueled a campaign to defend the preeminence of the German language in the empire, and especially in such contested areas as Bohemia and Slovenia. National leaders such as Taaffe and Badeni had made concessions in previous decades to the minority populations in Bohemian and Slovenia, and the security of Austro-Germans was endangered in the eyes of the ever-fewer liberals.

From the argument that began in Rottenbach in 1899, it is clear that Johann Huber was not only an adherent of the liberalist-now-nationalist thinking, but an active representative of the cause. This made him, by default, at least a passive opponent of the Catholic Church. Because he was not alone in this camp, it was anything but certain that conservative candidates backed by the Catholic Church would win the local election in May 1899. As it turned out, the conservatives (namely, the Catholics) were indeed victorious, but in the wake of the election, Johann Huber came under attack from the church that was both his religious home and the principal opponent of his liberal philosophies.

The Fight Begins

The conflict commenced with a letter to the editor of the Rieder Wochenblatt (Weekly Newspaper) on June 6, 1899, that criticized Huber’s involvement with the liberal cause during the election campaign. At the time, Huber was serving on the finance committee of the local Catholic parish, but clearly felt free to engage in politics from whatever perspective he espoused—and to oppose officials of his native church if need be. The letter was published anonymously in the newspaper and included harsh remarks about Huber:

The Rottenbach Parish is well known. Whenever we have an election, there’s a real battle, because the members of the liberal German National Party use all possible methods to suppress the members of the Catholic Peoples Party. Especially one truly German National little farmer boy [meaning Johann Huber] spared no effort. He paid day-laborers and sent his employees out with notices with this wording: Get out and vote German [liberal]! This is a battle against the Catholics! . . . So what do we hear since the election? Lots of curse words were directed toward the clerics by the aforementioned little farmer. Curse words that we could never repeat. So what is it that has this little farmer so upset? First of all, he really wants to see his relative, Mr. [Josef] Schamberger, elected to the Reichsrat. Too bad Schamberger couldn’t get the votes. And no cleric should cast a vote in that election. Oh, you poor little farmer! Be of good cheer and don’t lose hope. Next time we’ll all help so that Schamberger of Pram can be elected to the Landtag and then on to the Reichsrat. Maybe that will make it possible for the German Nationals [liberals]—and especially this little farmer—to fulfill their dreams as they long for Germany. But since last Saturday when the [Catholic conservative] blacksmith Mr. August Etz of Ried won the election by a great majority, the German Nationals in Rottenbach will have to table their efforts and their joy until next time.[9]

Despite the correspondent’s accusations, none of Huber’s writings suggest that he leaned in the direction of Pan-Germanism. Some of the most enthusiastic Austro-German nationalists of the time were indeed promoting pan-Germanic views in an effort to strengthen the position of the German language in Austria, but the surviving liberal principle in Austria was to defend the dominant position of the German language in the dual monarchy, not to join German Austria to the young German Empire (established in 1871). Additionally, if Huber had supported the annexation of his homeland to another nation, he could hardly have called himself a loyal Austrian in subsequent letters. But the fact still stands: individuals in the community were beginning to antagonize Johann Huber.

Johann Huber was a loyal member of the Rottenbach Catholic Church in 1899. He was baptized in 1861 and married in 1890 at this alter. Photo by Roger P. Minert.

Johann Huber was a loyal member of the Rottenbach Catholic Church in 1899. He was baptized in 1861 and married in 1890 at this alter. Photo by Roger P. Minert.

A second letter was published anonymously in the newspaper two weeks later; it was written by the same correspondent, by his own admission:

If you read a liberal newspaper nowadays, it seems that anything that’s traditionally Catholic has to be berated and exterminated. . . . Our opponents are mostly upset about the fact that the conservatives have the majority among our [local] representatives. And it would be so nice if the National Liberals could gain the majority—because they could run up the debt and pass laws against the [Catholic] Church. . . . In the letter I wrote previously, I stated that the little farmer wanted to see his relative, farmer Schamberger, elected to the Reichsrat. . . . I simply wanted to indicate how much that little farmer was determined to advance his relative’s cause. As this little man has said, if he only had a better place to make his speeches, he’d gladly hold meetings in favor of his relative Schamberger. The German Nationals in Rottenbach insist that the Catholic Church hasn’t been damaged at all by the German National newspapers or politics. That’s a good indication of how short-sighted these farmers are; they can’t see as far as the end of their noses.[10]

Both letters may have been penned by a Catholic cleric. This supports the theory of John W. Boyer that the liberal movement and its monumental gains of 1867–68 were causes of “occupational anxiety” among Catholic priests at the parish level. It might appear that the loss of power and influence of the Liberal Party in Austria by the 1880s had compensated Catholic clerics in part for the emasculation of the concordat a few years earlier, but at least some of them harbored resentment for the weakening of the church’s hand in Austria since the new laws were passed in 1867–68.[11]

The writer’s final line in his letter of June 20 must have angered Huber: “If such people [as Huber] would just see the light, namely that only the Catholic religion can show them the way to temporal welfare and eternal happiness!”[12] Within a few months, Huber would seriously question this assertion.

Huber Responds to His Attacker

Huber was convinced that the author of the letter was assistant pastor Karl Schöfecker of the local Rottenbach Catholic parish. It could hardly have been Pastor Johann Aepflbaur, who, at ninety years of age, had no energy to invest in such a conflict. Huber responded to the same newspaper with a letter to the editor in his own defense. That lengthy letter (more than 1,400 words) appeared on July 9 in the Rieder Sonntagsblatt and included the following comments:

Long before the election, the clerics were openly active in this political campaign. No lies or twisting of the facts can help them now. We know all about it. It’s been said that I paid laborers and used them to aid my side. That’s a lie. Lying is a sin, indeed a very serious sin. But it would seem that lying isn’t a sin for certain clerics. Apparently they’re exempt from this law.[13]

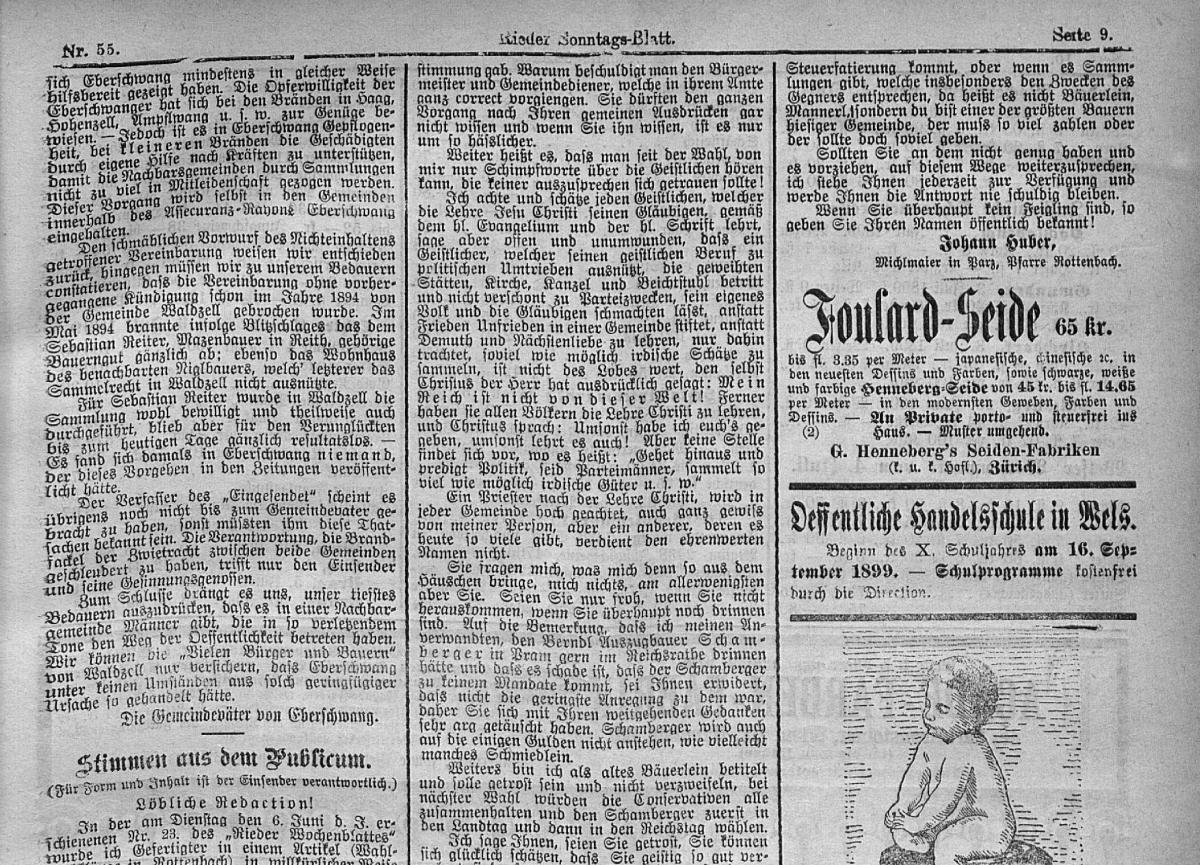

Johann Huber's first letter to the editor was published on July 9, 1899, and was more than 1,400 words long (shown here only in part).

Johann Huber's first letter to the editor was published on July 9, 1899, and was more than 1,400 words long (shown here only in part).

Those were strong words, but a few paragraphs later, he clarified his stance vis-à-vis church leaders in a subdued tone:

I respect and honor any cleric who teaches the gospel of Jesus Christ to his parishioners in accordance with the holy scriptures, but I’ll declare in public and without hesitation that any cleric who uses his church position to promote political causes, or abuses the pulpit, the sanctuary, or the confessional, rather than promote the welfare of his constituents, who spreads conflict rather than peace, instead of teaching humility and charity, is unworthy of praise.[14]

Huber defended his political party as one consisting of loyal subjects of the Austrian crown and ethnic Germans—not prospective citizens of the neighboring German Empire. In that same regard, he accused the Catholics of siding with the Empire’s native Poles and Czechs against ethnic Germans such as Huber and his Upper Austrian neighbors. Huber addressed his opponent as “our fine sir” and called him a “famose[s] Herrchen [most honored little master]” in an obviously sarcastic and condescending air.[15] In conclusion, he challenged the writer to identify himself publicly. The tone of the response suggests that Huber had no doubt that young vicar Karl Schöfecker had authored the defamatory letters.

St. Peter's Catholic Church in Rottenbach as it has appeared since 1698. Parts of the structure date back to AD 1387. Photo by Madeline Stoker.

St. Peter's Catholic Church in Rottenbach as it has appeared since 1698. Parts of the structure date back to AD 1387. Photo by Madeline Stoker.

If the Catholic Church had fired the first volley, Johann Huber was ready and willing to respond. What followed was a public airing of political and religious grievances that quickly escalated from skirmish to war. On Sunday, July 30, 1899, Schöfecker included in his sermon an energetic attack on Huber and his political stance. Totally unwilling to forgive such an offense, Johann responded within days with one letter to Schöfecker and a second to Pastor Johann Aepflbaur. To the supposed offender he wrote:

During the early service on Sunday, July 30, you made some very specific remarks about me in the presence of the faithful. . . . [I]s that morality and ethics and the proper way to stir up the believers? Is that the kind of speech that should be given from the pulpit rather than teaching the gospel? You know perfectly well that when you’re speaking from the pulpit nobody can contradict you . . . In a public forum you’d get the answer you deserve! By the way, you really let the German National Party have it on St. Peter and Paul’s Day [June 29]! That kind of preaching won’t earn you any accolades. You should take old Pastor Aepfelbauer as your example; he preached the gospel to the faithful without tiring.[16]

In his letter to Pastor Aepflbaur (likely written the same day), Huber expressed a spirit of reconciliation. He was not interested in continuing the hostilities Schöfecker had initiated:

Due to the fact that [Schöfecker] chastised me on July 30, I feel it my duty to write you a few lines to inquire whether that was justified. To read such things from the pulpit yields no good fruits. The Sabbath day exists to offer rest, courage, comfort, and peace as is shown in the teachings of Christ to be harvested in the church. It’s not a time for discord or anger as happened on that day. I’ve heard nothing but curses and mockery for an entire week. . . . I hereby formally request that you speak with the vicar and instruct him that he must recall his words at the [pulpit]. If this doesn’t happen, I’m inclined not to go to church again.[17]

Neither Aepflbaur nor Schöfecker responded, and no retraction was ever made. Huber’s recollection of the insult was still distinct more than four years later, when he wrote the following to the newspaper:

On July 30, 1899 the sermon wasn’t given by the pastor, but by his vicar Mr. Schöfecker. He appeared at the podium with issue no. 55 of the Rieder Sonntagsblatt and read a portion of my article—but of course only those parts that fit his argument. He didn’t mention the reasons why I’d written the article in my defense. While he was reading, all eyes in the church were on me and it occurred to me that Christ once said, “My house is a house of prayer, but ye have made it into a den of thieves!” At that moment I decided to never enter that church again as long as I lived, where from a sacred location I’d been attacked viciously in front of the entire congregation, without any opportunity to defend myself. Since that time I haven’t gone to any church building. I went looking for a Bible, a New Testament, and as I read, my eyes were opened. I realized just how far those so-called “priests of charity” had wandered away from Christ.[18]

A man of his word, Johann Huber ceased to attend mass in the Rottenbach church. Nevertheless, he expressed no animosity toward the Roman Catholic Church in general or proffered a rejection of its teachings; he had been offended only by local church leaders. However, he was apparently no longer a fiercely loyal parishioner and was in a state of mind to consider religious alternatives. A life-altering option presented itself almost immediately.

Johann Huber Meets a Mormon

In the summer of 1899, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) was almost totally unknown in Austria but was well established in Germany and Switzerland. Indeed, enough was known about the so-called Mormonen in central Europe that a significant number of tracts and books had appeared attacking the new religion. Thanks to that literature and to local newspapers, many Germans and Swiss knew about the Book of Mormon and the practice of polygamy among Mormons in the United States. As part of the novelty of Mormonism in Austria, an article in the local newspapers had reported missionary activities just weeks before Huber was attacked by Schöfecker. The article was entitled “Mormonen in Österreich” and indicated that the sect had been founded by Joseph Smith—a seeker of treasure and gold.[19] It explained that Smith “translated what he claimed to be holy scriptures from golden plates given to him by an angel named Moroni.”[20]

Just a few weeks after the vicar’s attack on Huber, LDS missionary Martin Ganglmayer made contact with the Michlmayr farmer. Ganglmayer, returning now to his hometown as a Mormon missionary, came into contact with Huber and learned of the recent controversy.[21] He was likely pleased to find an Austrian prepared to discuss an alternative to the dominant local church.

Ganglmayer apparently convinced Johann Huber of the truth of the restored gospel before the year 1899 came to an end. Huber later wrote the following about the process of his conversion and about the Mormon elder:

And so I remained by myself [in 1899], carefully studying the Bible in my closet. And I developed a yearning for a church with apostles and prophets as Christ set up his church in the earliest Christian times. As fate would have it, I met a missionary from the United States in Haag in the fall of 1899. He was there for a few days while on his way through Austria. And as fate would have it, we talked about religion and Christianity. He gave me some books that I enjoy very much and that uplift me.[22]

Ganglmayer was soon transferred back to Germany. Just two weeks into the new century, he wrote to Rottenbach from mission headquarters in Frankfurt am Main. He had recently received two letters from Huber detailing the family’s increasing difficulties; by then Huber was in the process of deviating from not only his native church but also from his neighbors and friends. Ganglmayer wrote back to Huber:

Although I was somewhat surprised by the bad news reported in your second letter, one basically couldn’t expect anything less to happen than that Satan and his minions would do everything in their power to discourage you if at all possible. It will really be a miracle if you come through this process unscathed.[23]

Ganglmayer went on to compare Huber somewhat grandiosely with Martin Luther, who, in the sixteenth century, boldly withstood the Catholic Church and the Holy Roman emperor in clinging to his reformist convictions. It is apparent from Ganglmayer’s letter that Johann had reported being assailed by locals. Perhaps his neighbors had read about polygamy among Latter-day Saints or believed the Rottenbach priest. In response, Ganglmayer gave the farmer some detailed advice (including scriptural references) about how to defend the new faith and the doctrine of polygamy, while indicating that polygamy had been officially discontinued. The missionary’s letter also provides insights into the religious and family struggles of Johann’s wife, Theresia:

It might be a bit difficult for you to calm your upset wife and to direct her onto the correct path. . . . Treat her with kindness and respect and try in peace and calm to explain the entire situation to her. . . . A good and true wife will never leave her husband when the storms of life rage, especially if she realizes that her husband’s motives are good and honorable and that he’s doing nothing but striving toward what is higher and more noble.[24]

One incident that occurred at about this time made Huber truly angry, as he later wrote: “When [Schöfecker] realized that I was serious about leaving the Catholic Church, he agitated against me among my relatives. Once he tricked my wife into going to a home where a lot of people assailed her with threats and bribery to get her to stop me.”[25]

The conflict that erupted in the summer of 1899 between farmer Johann Huber and the local Catholic clergy began as a public affair contested in the newspapers, but would soon escalate and involve many other individuals and groups in Rottenbach and nearby cities. If Johann Huber ever imagined that he could deviate from the Catholic Church and simply choose his own path without being noticed, he was sadly mistaken.

Notes

[1] The other two principal European empires at the time were Germany to the northwest and Russia to the east. In several letters written a few years later, Huber reminded his audience that he was a loyal, tax-paying citizen.

[2] Jonathan Kwan, Liberalism and the Habsburg Monarchy (Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 28.

[3] Kwan, Liberalism, 3–5. The liberals also believed that the Slavic culture of Bohemia and Slovenia had contributed little to the world in the areas of music, art, and literature. German ethnocentrism was a distinct characteristic of the Austro-German liberals.

[4] Erika Weinzierl-Fischer, Die Österreichischen Konkordate von 1855 und 1933 (Munich: R. Oldenbourg, 1960). The original text is presented on pages 250–58.

[5] Weinzierl-Fischer, Die Österreichischen Konkordate, 251. Article 8 provided that Catholic officials were to appoint teachers in all schools and “that nothing contrary to the Catholic faith and standards of decency be taught in those schools.”

[6] Weinzierl-Fischer, Die Österreichischen Konkordate, 254, article 20.

[7] Weinzierl-Fischer stated that the Austrian defeat at Königgrätz in 1866 meant the end of the Konkordat—much to the satisfaction of the liberals. Weinzierl-Fischer, Die Österreichischen Konkordate, 101–2. The new constitution allowed weddings to take place outside of the Catholic Church (meaning in the county office or in another church recognized by the government).

[8] Pieter M. Judson, Exclusive Revolutionaries: Liberal Politics, Social Experience, and National Identity in the Austrian Empire, 1848–1914 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996), 188–91.

[9] Rieder Wochenblatt, June 6, 1899, 2–3. Josef Schamberger was his brother-in-law, having married Johann’s sister, Franziska, in 1889.

[10] John W. Boyer, “Catholic Priests in Lower Austria,” 353. Boyer treated in great detail the plight of Catholic parish priests in his study of those men in Vienna and Lower Austria (the crown land bordering Huber’s native Upper Austria). He determined that those priests generally lamented what they believed to be their lower position in the socio-economic spectrum of their parishes. They expected to be treated as members of the same status as “public school teachers and the middle level state bureaucrats.” The fact that their salaries and benefits had been substantially improved by a law enacted in 1885 does not seem to have mollified them. John W. Boyer, “Catholic Priests in Lower Austria,” 353. Boyer treated in great detail the plight of Catholic parish priests in his study of those men in Vienna and Lower Austria (the crown land bordering Huber’s native Upper Austria). He determined that those priests generally lamented what they believed to be their lower position in the socioeconomic spectrum of their parishes. They expected to be treated as members of the same status as “public school teachers and the middle level state bureaucrats.” The fact that their salaries and benefits had been substantially improved by a law enacted in 1885 does not seem to have mollified them.

[11] Rieder Wochenblatt, June 20, 1899, 3.

[12] Johann Huber to the editor, Rieder Sonntagsblatt, July 9, 1899, 9.

[13] Johann Huber to the editor, Rieder Sonntagsblatt, July 9, 1899, 9.

[14] The word herrchen is also used to refer to the master of a dog or some other domestic animal. When applied to a human, it is highly derogatory.

[15] Johann Huber to Karl Schöfecker, August 1899, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection, Rottenbach, Austria.

[16] Johann Huber to Johann Aepflbaur, August 1899, Wilhelm Hirschmann private collection, Aggsbach Markt, Austria.

[17] Deutscher Michel, January 16, 1904, 13.

[18] Rieder Sonntagsblatt, June 18, 1899, n.p., Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[19] Rieder Sonntagsblatt, June 18, 1899, n.p., Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[20] Rieder Sonntagsblatt, June 18, 1899, n.p., Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[21] Teply, Das Licht Scheint in der Finsternis, 49. Ganglmayer arrived in the mission on August 11 and was apparently assigned to work in Munich, Germany.

[22] Johann Huber, Deutscher Michel, January 16, 1904, 13.

[23] Martin Ganglmayer to Johann Huber, January 15, 1900, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[24] Martin Ganglmayer to Johann Huber, January 15, 1900, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[25] Salzburger Volksblatt, February 6, 1904, 17–18.