The Pressure Is Off—Or So It Seems (1905–8)

Roger P. Minert, Against the Wall: Johann Huber and the First Mormons in Austria (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 118–41.

While the Wels District Court ruled that the Mormon faith was neither officially sanctioned nor forbidden in Austria, there are no surviving documents that report any court action against Johann Huber or any other adherent of the LDS Church in Ried County until the summer of 1909. If this was actually the case, Johann Huber would have had to deal for more than four years with agencies that had power only to harass and threaten him and burden him with small fines. However, during that same period of four years, he had no assurance that the courts would not summon him again to defend himself against invalid charges.

Saving the Souls of the Huber Children

On January 31, 1905, Pastor Josef Schachinger wrote to the Ried County Office to pursue new ways of forcing young Johann Huber to attend church services. He made reference to the fact that the Provincial School Board in Linz had offered the opinion on December 21, 1904, that “participation in religious instruction and church services was an integral component of the educational system in the public schools.”[1] Schachinger requested that the county take action to force Michlmayr Johann Huber to send his son to church services “lest the boy become estranged from the Catholic Church.”[2] Worse yet from the pastor’s perspective, “the boy probably has to help with Mormon worship services.”[3]

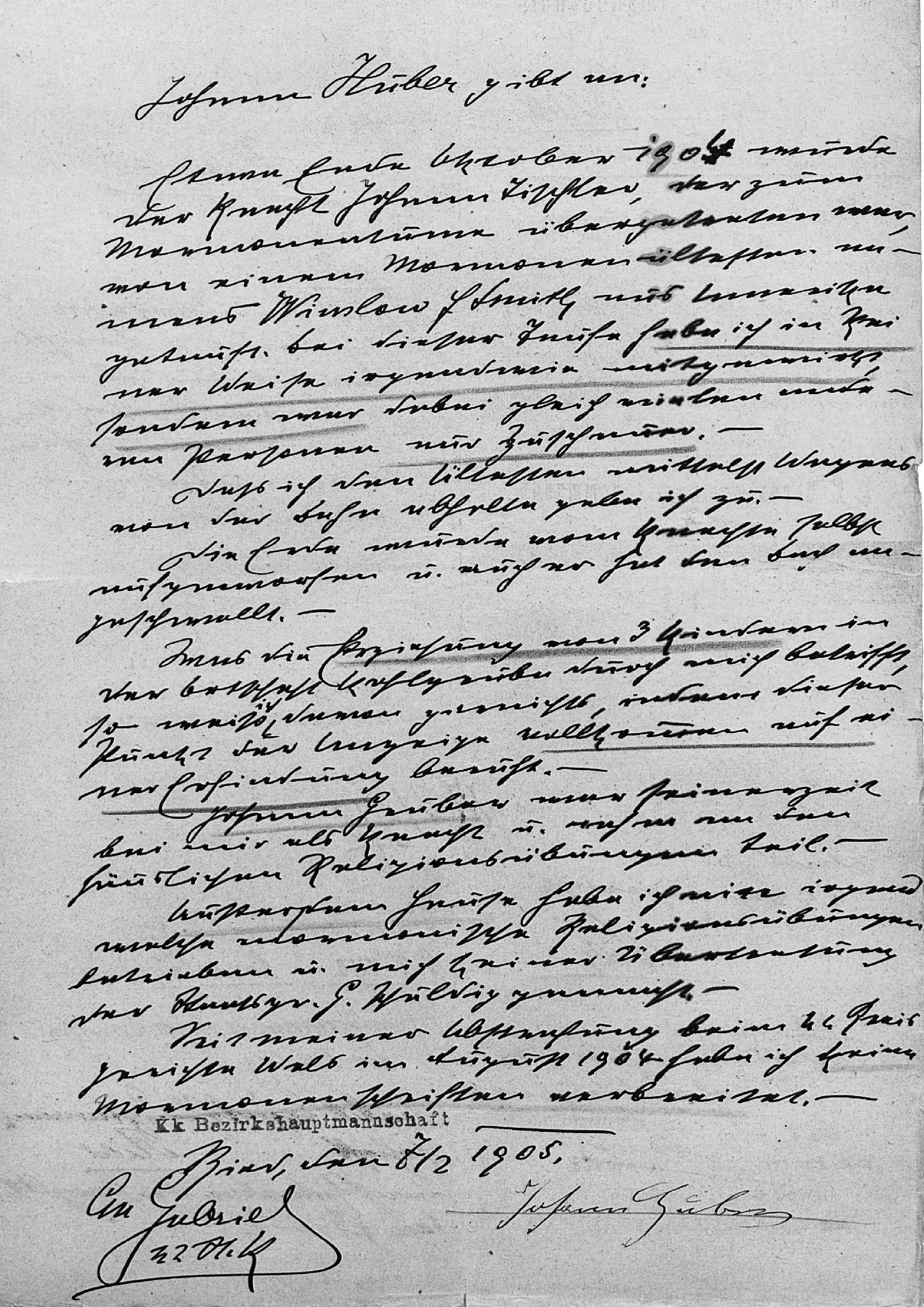

Perhaps in an attempt to prevent court actions against himself, Johann Huber traveled to the Ried County Office on February 7 to give his account of the Johann Tischler baptism that had taken place four months earlier (see pages 83–116):

I didn’t participate in this baptism in any way, but was simply an observer as were many others. I admit to transporting the elder in my wagon. The laborer [Tischler] himself blocked up the stream to make it deep enough. Regarding the instruction [reportedly] given by me to three children in Kohlgrube, I know nothing. This item in the report is totally fictional. Johann Gruber was at that time my employee and participated in our home worship services. Otherwise, I’ve never held Mormon services outside of my home and have thus never violated national laws. Since I was fined by the Wels District Court in August 1904, I haven’t distributed any Mormon literature.[4]

Johann Huber was wise to make this public statement. In it, he was able to refute an important charge—that he was preaching Mormonism to children. He could also clarify his role in the baptism of Johann Tischler—namely that he did not function as a church official in the event. Finally, county officials must have been pleased to hear him state that at the time, his religious activities away from home had decreased substantially. However, Huber didn’t state that he wasn’t talking about Mormonism in public. He wasn’t prepared to make that concession and cease to declare the teachings of his adopted church.

The Huber deposition of February 2, 1905, was penned by a clerk.

The Huber deposition of February 2, 1905, was penned by a clerk.

In writing letters to his ecclesiastical supervisors in Linz, Josef Schachinger had no reason to suppress his emotions or use polite language as he apparently felt required to do when writing to government entities. His letter of March 3, 1905, is an indication of his freedoms. He expressed his concerns that the elderly mother of Johann Huber might soon become ill and need the last rites as a pious Catholic woman. How could he visit her when there was a very mean dog on the property? he wrote. His letter ends with this postscript: “Michlmayr is much meaner than the dog! And his wife [Theresia] is just as mean!”[5]

The following statement is found in a Ried County School Board document dated February 23, 1905: “The [Catholic] Church office is in agreement with a previous decision that the Sunday church service is not a school church service as defined by the law.”[6] It would be important to know which Catholic Church office agreed with this decision. It could hardly have been the Rottenbach Parish, where Pastor Schachinger had pressed the issue for years. For him, such a decision would have constituted a major defeat in his campaign against the Michlmayr farmer.

The district school board gave full details on this policy five days later, citing a ruling of 1885 regarding the public schools and religious services. The ensuing edict declared that no action would be taken against Johann Huber in this regard. However, this final sentence is noteworthy: “If said pupil [Johann Huber] fails to attend church services regularly scheduled by the school’s principal, this office is to be informed immediately.”[7]

Pastor Schachinger could not be expected to receive this notice sitting down, and he wrote a spirited two-page letter to the county office in Ried to protest the policy. His missive included five points that can be summarized as follows:

1 The law states that Johann Huber [Jr.] must be raised Catholic.

2 Johann’s religious upbringing includes attendance in Catholic religion classes and at religious services.

3 Sunday mass must be considered one of the church services he must attend.

4 Absence from mass constitutes absence from school-related activities.

5 The recent ruling regarding church services should be rescinded.[8]

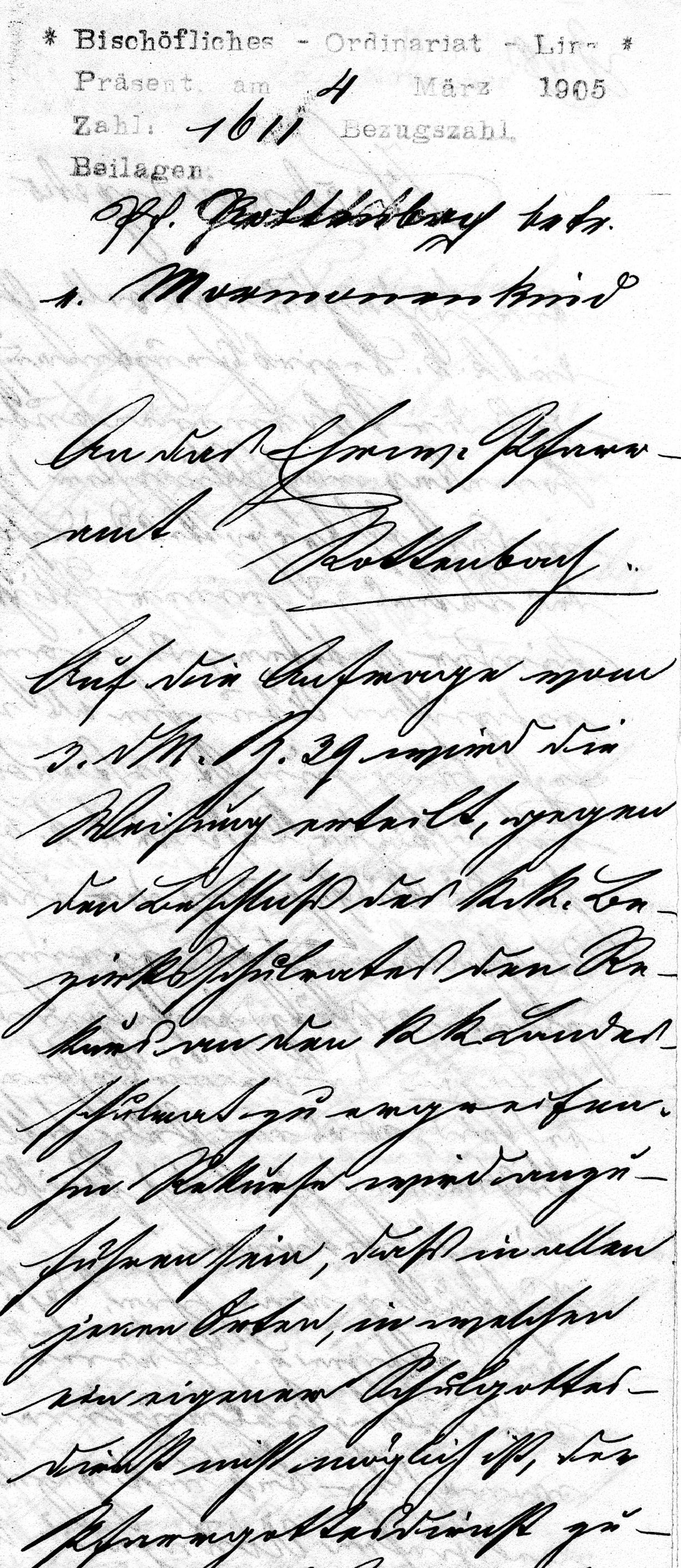

The bishop in Linz supported Schachinger in this campaign based on the following reasoning: if a parish is too small to have a separate worship service for the children in the public school, the general worship service must fulfill that purpose and thus the schoolchildren can be compelled to attend the general worship service. Schachinger was encouraged to use that logic when appealing to the county for action.[9] This opinion seems to contradict the county statement of February 23 (cited above).

The Catholic bishop in Linz spent quite a bit of time responding to Pastor Schachinger's letters regarding Mormonism in Rottenbach.

The Catholic bishop in Linz spent quite a bit of time responding to Pastor Schachinger's letters regarding Mormonism in Rottenbach.

Following his protest to the county office and acting on the advice he had received from the diocesan office in Linz, Schachinger appealed the ruling of the Linz District School Board to the Provincial School Board, also in seated Linz.[10] In a session held on March 24, the latter denied the pastor’s appeal and offered this justification: “It is not the responsibility of school officials to monitor the attendance of the pupils at church services on Sundays and holy days.”[11]

On April 3, 1905, Schachinger again took up the cause of young Johann Huber, by then twelve years old; the priest wanted very much to keep the boy in the flock. Johann had attended confession and communion on February 22 and had been absolved of his sins. However, the latter action was taken without approval—by the vicar who didn’t know the boy. Schachinger was concerned that if Johann were allowed to participate again, he would commit sacrilege twice. On the other hand, the priest expressed these concerns:

If we don’t allow him to participate, his father will be encouraged to keep the boy from coming to services again. Then he’ll certainly leave the church when he turns fourteen. The pastor and the vicar request your advice, because they don’t want to assume responsibility in this matter.[12]

The response from the diocesan office in Linz reads in part:

As long as Johann Huber belongs to the Catholic Church, he cannot be denied participation in confession or coming to the altar. It is up to the confessor to decide whether the boy is worthy of absolution or not. If he doesn’t choose to attend by his own free will, he shouldn’t be compelled. It would be good to call him in before Sunday to ask him if he’s absent from Sunday services by his own choice or because his father refuses to allow him to attend. If such is the case and the boy isn’t lacking in good will, it would be easier for the father confessor to absolve him of his sins. Perhaps participating in the sacrament could save him from apostasy.[13]

Refusing to end his campaign, Schachinger sought another, potentially more sympathetic, audience. He wrote to the Upper Austrian Ministry of Culture and Education on April 12 and not only rehearsed his numerous attempts to achieve his goal through the courts and the school boards, but reminded the ministry of several laws and rulings upon which he based his assertion that young Johann Huber and his sisters, Theresia and Maria, be required to attend religious services in the local Catholic church. The pastor’s dedication to his cause is reflected in the final sentence: “Otherwise, the children will be strengthened in Mormonism by their father and all will be lost.”[14]

On May 10, 1905, Principal Karl Binna of the Rottenbach School wrote to the District School Board in Ried to inquire whether the two Huber children attending his school, Johann and Theresia, were still Catholic or had been withdrawn from that church. He needed to know under which religion to enroll them, so that he could answer the question of the Catholic vicar regarding their absence from his religion class.[15] The school board forwarded the inquiry to the Ried County Office. Given the duration of the case against Johann Huber and the number of county documents devoted to this controversy, it is surprising that August Edler von Chavanne responded that the county didn’t know the answer to that question.[16]

Among the more than six hundred pages of documentation in historical archives relating to the Mormons in Rottenbach, only one deals with the summer of 1905. On June 14, Pastor Schachinger reported the results of the Whitsuntide processions in which nearly all parishioners took part. “Of course the Mormons didn’t participate. Thus the primary purpose of this celebration wasn’t achieved.”[17] Apparently the priest was hoping that at least some of the Huber children would attend, or that some kind of reconciliation with the family would be possible.

The letter written by Pastor Schachinger on September 30 of that year leads one to believe that few government officials were interested in the Rottenbach Mormons anymore. The pastor demanded to know why his appeal of April 12 had yet to be heard. His impatience is sarcastically expressed in one sentence: “Indeed, you could hardly act too soon on this question!”[18] The officious response from the county office (the last one approved by von Chavanne) stated quite properly that the matter at hand had yet to be dealt with formally.[19]

On November 14, 1905, an almost despondent Schachinger wrote a letter to the bishop in Linz. Although he had consistently attempted to keep Johann Huber coming to church, the boy had neither attended church services on Easter Sunday nor since then; he had only attended the religious class at school from November through May. “The boy is lost,” bemoaned the pastor. As if Johann’s spiritual status weren’t bad enough, his two younger sisters were still attending Catholic Church services, but not catechism.[20]

The office of the bishop in Linz offered little consolation: “We’re sad to read your report of November 14. If the county office doesn’t reach a beneficial decision, the only thing left is to pray for mercy for these unfortunate children.”[21]

The final official act in the legal proceedings against Mormon Johann Huber in the year 1905 was a ruling handed down by the Ministry of Culture and Education of the province of Upper Austria in Linz. Pastor Schachinger’s appeal for a reversal of school board edicts was denied.[22] Again, Huber could breathe a sigh of relief. The courts had been silent for months and it now appeared that attacks from the local Catholic parish might be losing their steam.

The Early Growth of the Rottenbach LDS Branch

At the onset of the year 1906, the various agencies of Ried County still knew very little about the fledgling LDS Rottenbach Branch (still conducting worship services on the Michlmayr farm), despite the voluminous reports coming and going. In reality, the missionary efforts of Johann Huber were much more ambitious and extensive than the monitoring agencies knew. By this time, no fewer than eleven persons had joined the LDS Church and were listed in the official records of the branch. Eight of those eleven were born in different towns in the province of Upper Austria and the city of Salzburg. Most of the towns were within a dozen miles of the Huber farm in Rottenbach and could thus be reached by an average person on foot within three hours.[23]

By the summer of 1906, the branch had grown by five additional members, who were born (and likely residing at the time) in five different towns.[24] One of them came from Bohemia, an Austrian province barely twenty-five miles to the north. It is clear that although the newspapers and police offices in the region were identifying relatively little Mormon activity, the church was active and growing.

Three LDS Church pamphlets printed in Zurich, Switzerland, and Berlin, Germany, were used by Johann Huber to support his preaching among his friends, employees, and neighbors in Upper Austria. (He listed them as items taken from him during the court proceedings of August 1904.) There is no discounting the idea that he was still determined to continue his missionary work ex officio when he turned his personal calendar to 1906. He wrote to the LDS mission office in Leipzig and requested that more literature be sent to Rottenbach. His request was granted and he paid the nominal printing costs for it.

It can come as no surprise that Huber’s efforts to share his new faith would unsettle the local Catholic clergy again once they found out. On March 15, Pastor Schachinger sent his latest and most emphatic message to the Ried county office:

Johann Huber has been preaching without interference to our sexton here in Haag. In a letter to our vicar, Ludwig Erkner, he announced that he will be preaching at 2 o’clock next Sunday in the Seidlhuber [inn] in Niedernhaag. He even invited the vicar so that he can convert him! Will this be allowed to happen in public, given the fact that the Mormons aren’t recognized by law? The letter in question was written to the vicar because he took from Johann and Aloysia Huber [born 1898] the Mormon catechism; they were showing them to other pupils and teaching them. Apostasy even in the schools! Now the county can see how honest the Hubers were when they told the church that they wanted to raise their children in the Protestant faith. Frau Huber said that she was converting to Protestantism just so she wouldn’t be forced to raise her children as Catholics. I’ve told your office about this several times but to no avail. Will you still not take action against Johann Huber?[25]

August Edler von Chavanne had left the office in Ried County in February, so his successor, Karl Planck Edler von Planckburg (another member of the lower nobility), read Schachinger’s latest complaint. Whether the new head county commissioner understood the Catholic Church’s crisis in Rottenbach or a lesser but better-informed official responded to this latest complaint, a directive was sent to the Rottenbach School stating that no unauthorized literature (i.e., Mormon tracts) would be approved for distribution there. The directive didn’t discuss the attendance of Huber children at school religious events but stated that the Mormon faith wasn’t making any progress anymore.[26]

Apparently, Schachinger wrote a similar letter to the county school board, who discussed the situation in a session held on March 29. Their simple resolution was to instruct the school personnel that pupils be allowed to bring only the required literature into the building.[27] A county writer added a short comment to the transmittal, stating that “Mormonism was not making any progress in Haag and Rottenbach.”[28]

Johann Huber may indeed have found that his life was less burdened with accusations and investigations in the year 1906. No documents bearing dates after April 20 of that year have survived. Had Schachinger given up the attempt to have Huber punished or at least restricted by the government? Had school boards and government offices grown tired of the controversy—convinced that Mormonism truly was no threat and would not spread?

As 1907 dawned, Pastor Josef Schachinger was still intensely concerned about young Johann Huber, whose fourteenth birthday was approaching (March 26). He and his vicar, Ludwig Erkner, reviewed the boy’s attendance record and were appalled. The vicar penned a report to the diocesan office with a very practical question:

Should J. Huber receive the grade of “satisfactory” on his elementary school report card or no grade at all? It is the opinion of the undersigned that Johann Huber (despite his frequent inability to pay attention) has received sufficient instruction to know the basics of Catholic doctrine, though he might not believe it. He received instruction in first confession and first communion in 1903 and 1904. Until Easter 1905 he also received the holy sacraments, but hasn’t since that time. It is anticipated that he will withdraw from the Catholic Church shortly after his fourteenth birthday. Nevertheless, the undersigned wishes to receive permission from your office to enter the grade of “satisfactory” onto the report card in order to divest his father, J. Huber of any reason to poison the other two Catholic children, Theresia and Maria, against the pastor.[29]

If the Rottenbach clerics expected the bishop to ease their burdens by making this decision for them, disappointment was their lot. “Give him the grade you feel is appropriate” was the simple response.[30] Schachinger took the matter to the county, again appealing on the basis of the law governing the Hubers’ eldest three children: their church affiliation could not be changed between the ages of seven and fourteen, at which time they would be free to choose their own church membership. Schachinger had asked the two Huber girls, Theresia and Maria, why they missed church services and they had answered, “Our father won’t let us go to confession anymore!”[31] The pastor stated that those two girls had previously enjoyed going to church. The Easter confession was approaching, and he had to know in advance who would be attending the event. As to young Johann Huber, “He is not learning anything in the Catholic religion course but his father has broken the law by teaching him about Mormonism.”[32] He had not attended confession and catechism instruction for more than two years and had not attended mass on Sundays and holy days for about three years. “So how can any Catholic priest enter a grade of ‘satisfactory’ in his grade book?”[33]

The first-grade class of the Rottenbach School in 1907. Vicar Ludwig Erkner is at the far left, and Prinicpal Karl Binna the second man from the right with the handlebar mustache.

The first-grade class of the Rottenbach School in 1907. Vicar Ludwig Erkner is at the far left, and Prinicpal Karl Binna the second man from the right with the handlebar mustache.

And what about the eldest daughter, Theresia? The good pastor indicated that she was finishing her seventh year in school and should be confirmed. Without this experience, he wrote, she could not advance to another school. In the final sentence of this latest letter to the county, the pastor again employed the term fanatisch to describe Johann Huber.[34] The Ried County Office replied that no fine would be imposed upon Huber for this offense, because he had been fined on previous occasions.[35]

The Huber family behind their barn in about 1908. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

The Huber family behind their barn in about 1908. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

The county then took no further action through the end of the year 1907. One wonders if Johann Huber was able to stay out of trouble for the next nine months, or whether other documents have simply disappeared. If the former was the case, he was certainly busy finding noncontroversial ways to spread the gospel as taught by the LDS Church.

Young Theresia Is Confirmed in the Catholic Church

A most curious event took place in the early summer of 1907 and was described in a letter written by Schachinger to the bishop in Linz on June 18: Theresia, the eldest Huber daughter, was given communion in the Catholic Church, but not in Rottenbach. Her sponsor had petitioned Huber four times to allow the girl to be confirmed, but he had rejected the notion each time. However, the “apostate mother” (Schachinger’s description) gave permission, and the participants (presumably without the father) “traveled in secret” to the town of Lambach (some ten miles to the south) for the event.[36] From several reports written by Schachinger, daughters Theresia and Maria had been attending church except when prevented by their father from doing so. The diocesan office in Linz responded in a positive tenor to Schachinger’s report and encouraged him to continue to prepare the next daughter (Maria, then only eleven) for the important Catholic youth events, primarily her anticipated communion in 1908.[37]

Was there religious dissension in the Huber home in June 1907? Were the girls bending to peer pressure (which is easy to imagine in the case of young teenagers)? Did the girls reject the teachings of Mormonism? Were they attempting to avoid the persecution suffered by their father and their elder brother? Because neither left an account of her life, these questions remain unanswered.

For reasons unknown, Theresia Maier Huber had not yet been baptized. Was she not convinced of the truth of her husband’s convictions? Was she concerned about what her friends and neighbors would say about her transfer to the Protestant Church and from that church to yet a third? Whatever her thoughts were, she had her hands full sharing the myriad trials of her husband, beyond the management of a household that included a large family and several hired laborers.

In November 1907, the Catholic priest was able to motivate the local school board to notify Huber of his duty to send daughter Theresia to church.[38] A similar notice was sent in December.[39] (Nothing was said about young Johann—had Schachinger given him up for lost?) There is no record that Michlmayr Johann Huber responded to the notices. After dealing with this question for nearly eight years, he likely treated those notices as just so much wasted paper.

Huber and Schachinger Square Off Again

Following a relatively quiet 1907 for Johann Huber—as far as persecution and prosecution were concerned—he reignited the struggle in 1908 by writing a four-page letter to Schachinger. It appears that the latter had again preached against the Mormons in his Sunday sermon. Huber was not willing to let the matter rest. His letter had a positive salutation: “Very honored friend, the pastor in Rottenbach.” But the tone quickly goes downhill from there.[40] He accused the priest of spreading lies in his sermon, specifically that the president of the LDS Church, Joseph F. Smith, had been jailed or forced to pay a fine. Huber offered to provide the correct details of the affair from the pages of Der Stern, the LDS Church publication in the German language.[41]

In his traditional, aggressive style, Huber began to preach in his letter to Schachinger about New Testament doctrines and teachings and referred to his own willingness to serve as a martyr for the Mormon cause; he believed he would be blessed for suffering persecutions in the name of Jesus Christ. He mentioned Old Testament prophets Abraham and Moses and even indicated that “a European war will start at any time now” so that the Jews may gather to Israel.[42]

Despite his spirited attacks on Schachinger and the Catholic Church, Huber began his final paragraph with another friendly salutation: “Dear friend, do not consider me to be your enemy. I am prepared to do good to all men. If we follow Christ, we can be the best citizens. That is the will of God—offering each other peace, love, respect, friendship.”[43] He signed the letter, “Respectfully, Johann Huber Michlmair Rottenbach,” but one wonders if the two salutations were penned with a hint of sarcasm.[44] It would require a remarkable Christian attitude for Huber to consider this longtime opponent his friend.

The distance from the Michlmayr farm (lower dot) to the Catholic Church (upper dot) is about one-third mile.

The distance from the Michlmayr farm (lower dot) to the Catholic Church (upper dot) is about one-third mile.

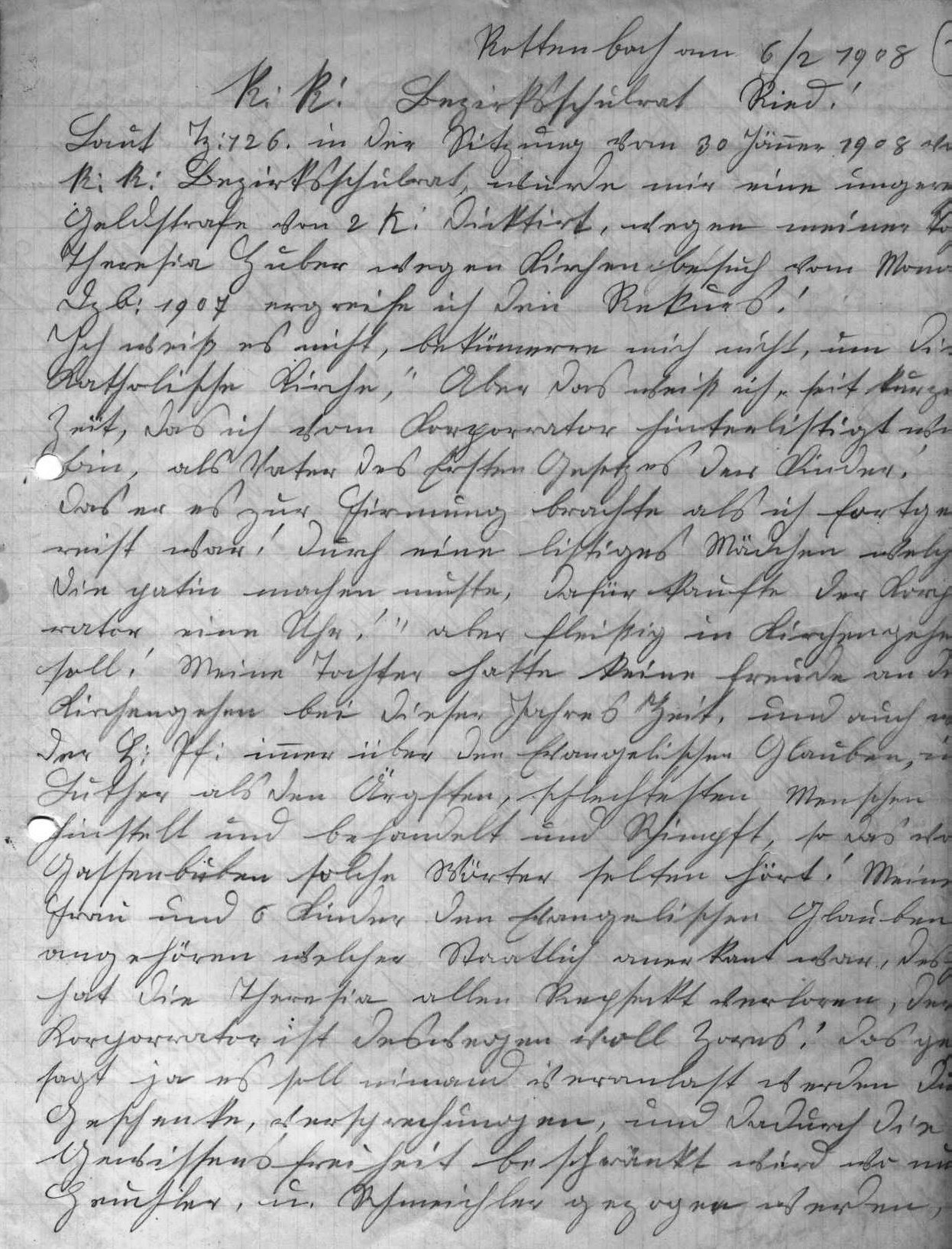

For school officials, the year 1908 opened with the reccurring question of the absence of young Theresia at school and church services. On January 30, the county school board met and decided to fine Huber two crowns for his repeated attempts to prevent his daughter from attending.[45]

The first page of Huber's letter to the county school board on February 6, 1908. He spent a great deal of time writing long letters. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

The first page of Huber's letter to the county school board on February 6, 1908. He spent a great deal of time writing long letters. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

In his verbose style, Johann responded to the district school board with a letter more than six hundred words in length. He rejected the fine and indicated that he would appeal the ruling, then went on the offensive, as he had on so many previous occasions:

I have been the victim of subterfuge on the part of the vicar. I am the father of my children according to the first law cited above. He took my daughter [Theresia] to confirmation while I was out of town. My wife found out about this through a very bright little girl. Then the vicar bought a watch for children who attended church regularly. My daughter wasn’t happy attending church at this time of year and the pastor was constantly criticizing the Protestant faith and Luther as the meanest and worst human being ever, using words rarely heard from street urchins. My wife and five children belong to the Protestant Church that is recognized by law. Thus, my daughter has lost all respect for [Catholics] and this has angered the vicar.[46]

Huber’s prime contention in opposing the fine was that Theresia had finished her required tenure in the elementary school (eight years) and was now working at home full time.[47] In another letter to Schachinger, he wrote, “I’m an Austrian citizen and am required to pay taxes. How can I do that without having people work for me? . . . My daughter’s strong body has supported me. She was asked to be available to carry grain and eggs and to take care of the younger children.”[48] His final comments addressed what he believed to be weaknesses and offenses committed historically by the Catholic Church.

The Ried District School Board met again and decided to fine Huber four crowns. This time he was threatened with incarceration for twelve hours if he failed to pay the fine within three days or present a certificate from the town hall stating that he was too poor to do so.[49] As with other fines, Huber either disregarded them or found a higher office to revoke them, or the agency imposing them simply gave up in the face of his stiff opposition.

In February 1908, the vigilant Ried County officials were again gathering evidence of continued Mormon missionary efforts. They sent a directive to the Haag Police Office regarding an article in the Oberösterreichische Volkszeitung that reported that a “Mormon apostle had held a meeting in our region.”[50] The police were instructed to determine whether the article was correct and responded on March 4 with the allegation that Johann Huber and his brother Matthias, who, also a convert, had preached to a Mr. Anzengruber:

Anzengruber’s sister, Zäzilie Wiesinger, lives in house no. 13 in Wendling. When she learned that [her brother] wanted to convert to Mormonism, she went to see him on February 23. She made several accusations in an attempt to stop him from doing this. A meeting similar to the one described in the newspaper article didn’t take place. The visit of the two Huber brothers [Johann and Matthias] was likely the basis of this claim.[51]

On March 8, 1908, Johann Huber appealed to the Ried District School Board to have the fine of four crowns revoked. The main theme of his long letter was that the Catholic Church and public schools should be separate, such that the school was not responsible for religious instruction. In maintaining this position, he was simply expressing the decades-old tenet of Austrian liberals that the power and influence of the Catholic Church should be, at the very least, reduced. He cited various Austrian laws regarding the exercise of personal religious beliefs and stated that his wife and six [sic] of his children were Protestant. In very bold language, he attacked the Catholic Church for what he believed to be its historical misdeeds.[52]

Again, there are no extant documents to describe the events of the spring and summer of 1908 in this otherwise quiet corner of Upper Austria. In the fall of that year, two events shrouded the Michlmayr farm in black. Johann’s mother, Theresia Polz Huber, became seriously ill in early September. As a devout Catholic, she deserved the best services the local clergy could offer, and Schachinger was determined to provide those—specifically the sacrament of extreme unction. Unfortunately, he was not permitted to do his duty. He described the circumstances in a distraught letter to the diocesan office on September 6:

The problems with the Mormons are never-ending. I found out on August 6 that old lady Michlmayr was ill. At the time I was able to walk a bit so I walked up there and offered her the last rites. “I can’t do it [she said], or else there’ll be real trouble with my family. Nobody’s taking care of me anymore. I have to ask God for forgiveness, etc.” When I was about to leave, Michlmayr came in and he was like a mad man, yelling and cursing at me and blaspheming: “The Catholic religion is the very worst on earth. You suck everything out of the people. You drive all of my employees away, etc.” He used wild gestures and made terrible faces. It was awful to behold! All of that was supposed to turn his mother away from Catholicism. “You’re not going to get her [body] for the funeral,” he said. Then a week later I got the message, “Get over here quickly! Old lady Michlmayr needs the last rites!” Mr. Raselseder [the vicar] had that privilege. But what happens when she dies? Will he allow her a church funeral? . . . I can’t visit old lady Michlmayr anymore. Either the door is slammed in my face or he yells at me like a mad man in the presence of his elderly mother because I won’t let him convert anybody to Mormonism.[53]

Johann Huber’s mother passed away the next day, September 7, 1908, at the age of seventy-nine.[54] As the heiress to the farm, she had been a widow since 1866. She is never mentioned in any other document as a party to the controversy that dominated the life of her sons, so we have no idea what her attitude may have been toward the question of Mormonism. It would seem that after nearly a decade of watching and listening, she would have known enough to make an educated if not inspired decision to embrace or reject the new church. However, it is also possible that her son never pressed her on this question or even instructed her about Mormonism. Perhaps she chose to ignore the issue, continued to attend Catholic services as expected, maintained her friendships, and lived out her life as any other elderly Catholic woman in Austria.

Mitzi Binna, wife of the Rottenbach schoolmaster, in the festive dress of the day (1911). The michlmayr women probably wore similar attire on church and national holidays.

Mitzi Binna, wife of the Rottenbach schoolmaster, in the festive dress of the day (1911). The michlmayr women probably wore similar attire on church and national holidays.

Josef Schachinger was sixty-three years of age at the time and in very poor health. The foot and back problems that had pained him for at least eight years were becoming unbearable. The letter cited above began with a lamentation: he had just returned from a reunion in Braunau to learn that his assistant Ludwig Erkner had fled the parish. The vicar had left a note explaining why he was leaving and asking for forgiveness, but Schachinger didn’t share those details with the bishop. In any case, the latter’s plea for a replacement was certainly sincere. Regarding his health, he wrote: “The instep of my foot has been draining seriously from a dozen spots since mid-August, as well as from an inch-long opening on the other side of my foot. The way my foot swells up every day is most frightening. In pain I can still read the mass, preach, receive confession and (sitting down) teach a few school classes, but nothing more.”[55] The Rottenbach pastor was clearly at the end of his rope and did not need additional aggravation from the Mormons within his parish.

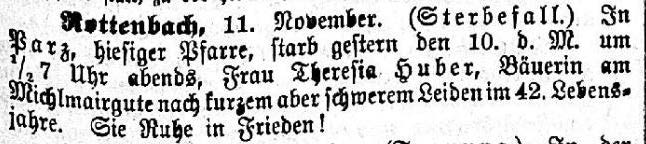

A modest entry in the local newspaper announced the passing of Theresia Huber in 1908.

A modest entry in the local newspaper announced the passing of Theresia Huber in 1908.

Another Death at the Michlmayr Farm

What should have been a joyful event at Parz 4 soon turned tragic. The Hubers’ twelfth and last child, Karoline, was born there on October 9. One month later, the family lost their mother; Theresia Maier Huber was only forty-one years of age when she died on November 10, 1908. The newspaper featured a respectful notice of the event, with no reference whatever to the controversy in which she had been embroiled: “Rottenbach. November 11 (death). Mrs. Theresia Huber, the wife of the farmer on the Michlmair estate in the Parz neighborhood of this parish, passed away yesterday, November 10, at 6:30 p.m. after a short but intense illness at the age of 41. May she rest in peace.”[56] At very least, the local correspondent for the newspaper harbored no ill feelings for the deceased. Perhaps the typical resident of the farming community of Rottenbach had no substantial argument with the Huber family. Theresia was still a Protestant of record but had never truly played the role.

New Controversies over LDS Missionary Activity

One week before Christmas 1908, the pastor of the Catholic Parish in nearby Altenhof recorded the following statement in the presence of three local men and sent it to the office of the Archdiocese of Linz: “Josef Hromadko stated that in the night of December 18–19 he was at the Michlmayr farm in Parz, Rottenbach Parish. [Huber] gave him several pamphlets and asked him to read them carefully and then to come back to him (on a Sunday, because he didn’t have any time during the week). [Huber] preached to his people on Sundays. He wants to give [Hromadko] a prayer book and accept him into the Mormon Church that he knows nothing about.”[57]

Johann Huber was again at work as a missionary. Due to previous rulings against such efforts, he should have restricted his preaching to his farm and among employees or others who came to the farm voluntarily. However, it is clear that his conviction of and dedication to the new faith made such reticence impossible. To the Michlmayr farmer, the commandments of God superseded the laws of men.

Notes

[1] As cited in Josef Schachinger to Ried County Office, January 31, 1905, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach. No copy of the original December 21, 1905, document can be found.

[2] Schachinger to Ried County Office, January 31, 1905.

[3] Schachinger to Ried County Office, January 31, 1905.

[4] Ried County Office, Johann Huber, Deposition, Ried County Office February 7, 1905, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1905, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[5] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, March 3, 1905, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[6] Linz District School Board, ruling, February 23, 1905, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried X L 1905. This record indicates that the county commission voted unanimously in favor of this statement.

[7] Linz District School Board to Rottenbach Catholic Parish and others, February 28, 1905. Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried X L 1905.

[8] Josef Schachinger to Ried County Office, March 12, 1905, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1904, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[9] Linz Diocesan Office to Josef Schachinger, March 11, 1905, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[10] Josef Schachinger to Linz Provincial School Board, March 12, 1905, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried X L 1905.

[11] Linz Provincial School Board, ruling, March 30, 1905, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried X L 1905.

[12] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, April 3, 1905, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[13] Linz Diocesan Office to Josef Schachinger, April 14, 1905, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[14] Josef Schachinger to Upper Austrian Ministry of Culture and Education in Linz, April 12, 1905, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1905, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[15] Karl Binna to Ried County Office, May 10, 1905, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1905, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[16] Ried County Office to Karl Binna, May 23, 1905, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1905, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[17] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, June 14, 1905, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[18] Josef Schachinger to Ried County Office, September 30, 1905, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1905, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[19] Ried County Office to Josef Schachinger, October 4, 1905, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1905, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[20] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, November 14, 1905, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[21] Linz Diocesan Office to Josef Schachinger, November 15, 1905, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[22] Linz Provincial School Board, ruling, December 11, 1905, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried X L 1905.

[23] Record of Members, LDS Rottenbach Branch, 1883–1923, microfilm no. 38866, Family History Library, Salt Lake City.

[24] Record of Members, LDS Rottenbach Branch, 1883–1923, microfilm no. 38866, Family History Library, Salt Lake City.

[25] Josef Schachinger to Ried County Office, March 15, 1906, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1906, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[26] Ried County Office to Rottenbach Elementary School, March 16, 1906, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried XI E 1906.

[27] Ried County School Board to Rottenbach Elementary School, April 4, 1906, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried XI E 1906.

[28] Ried County Office to Rottenbach Elementary School, April 18, 1906, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried XI E 1906.

[29] Ludwig Erkner to Linz Diocesan Office, February 9, 1907, Diözesanarchiv Linz, CA/

[30] Linz Diocesan Office to Rottenbach Parish Office, February 12, 1907, Diözesanarchiv Linz, CA/

[31] Josef Schachinger to Ried County Office, February 11, 1907, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1907, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[32] Schachinger to Ried County Office, February 11, 1907, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1907, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[33] Schachinger to Ried County Office, February 11, 1907.

[34] Schachinger to Ried County Office, February 11, 1907. The German word fanatisch is an intensely pejorative term.

[35] Ried County Office to Josef Schachinger, February 28, 1907, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1907, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[36] The event was, however, recorded in the Rottenbach Catholic Parish records on June 9, 1907. Franz Schoberleitner to Roger P. Minert, e-mail, September 16, 2014. Theresia did not officially withdraw from the Catholic Church until February 22, 1922.

[37] Linz Diocesan Office to Josef Schachinger, June 29, 1907, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[38] Rottenbach School Board to Johann Huber, November 19, 1907, Wilhelm Hirschmann private collection, Aggsbach Markt, Austria. This notice threatened possible action on the part of Ried County.

[39] Rottenbach School Board to Johann Huber, December 6, 1907, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[40] Johann Huber to Josef Schachinger, January 29, 1908, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[41] Johann Huber to Josef Schachinger, January 29, 1908.

[42] Johann Huber to Josef Schachinger, January 29, 1908.

[43] Johann Huber to Josef Schachinger, January 29, 1908.

[44] Johann Huber to Josef Schachinger, January 29, 1908.

[45] Ried District School Board to Johann Huber, February 1, 1908, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[46] Johann Huber to Ried District School Board, February 6, 1908, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[47] In many Austrian schools of the era, the eighth grade constituted the conclusion of public schooling. The church confirmation (Catholic in this case) coincided with the end of the eighth school year.

[48] Johann Huber to Josef Schachinger, January 29, 1908.

[49] Ried District School Board to Johann Huber, February 28, 1908, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[50] Ried County Office to Haag Police Office, February 28, 1908, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1908, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[51] Haag Police Office to Ried County Office, March 4, 1908, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1908, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[52] Johann Huber to Ried County School Board, March 8, 1908, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[53] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, September 6, 1908, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[54] Franziska Polz [LH6G-2YD], Family Tree database, FamilySearch, http://

[55] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, September 6, 1908, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[56] Anonymous letter in Oberösterreichische Volkszeitung, November 13, 1908, 3.

[57] Altenhof Catholic Parish to Linz Diocesan Office, December 19, 1908, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1908, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.