Peace at Last and the Later Life of Michlmayr Johann Huber (1911–41)

Roger P. Minert, Against the Wall: Johann Huber and the First Mormons in Austria (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 161–74.

Peace at Last and the Later Life of Michlmayr Johann Huber (1911–41)

Lambert Lechner arrived in Rottenbach in July 1910 to assume the leadership of the local Catholic Church. There is no way to determine whether he had been informed of the presence of the Mormon congregation there, but if he had been living anywhere near Ried County, he would have read or at least heard stories. He almost certainly spent some time with Schachinger (who remained in Rottenbach), so that information about Huber would have been transferred. However, Lechner may have noticed that the Mormons were still very few in number and considered the threat to his flock to be inconsequential.

In any case, only two documents have been located regarding Lechner’s service in Rottenbach, and those papers involve Johann Huber. Pastor Lechner wrote to his superiors in Linz on August 30, 1912: “On August 29 inst. the local resident, Mormon apostle [sic] Johann Huber, brought to this office the death certificate of a stillborn child. The father of the child is officially without church affiliation and the mother is Protestant [sic]. Therefore this parish office isn’t responsible to these people. This office can’t certify that the Mormon and the mother of this child were married by civil or ecclesiastic authority, or whether a wedding even took place. This office requests instructions as to whether this child’s birth and death are to be recorded in the parish baptismal registry.”[1] The response from the Catholic bishop was that Lechner was to send the child’s death certificate to the county office in Ried for action.[2] The resolution of the problem is not known. In any case, this is the only evidence that Johann and Bertha attempted to have a child of their own; at the time, Bertha was already thirty-eight years old. There would be no more children in the Michlmayr household.

If the newly arrived Catholic priest did indeed choose to disregard the family as non-Catholics—as his letter implies—he saved himself a great deal of grief. Whatever his course of action, the trail of documents telling the story of Johann Huber and his struggles to establish the LDS Church in Austria ends abruptly in 1912. No one could have been happier about this than Michlmayr Johann Huber; he had successfully defended himself against neighbors, the Catholic Church, government offices on three levels of jurisdiction, four different courts, several police offices, the local public school, and school boards at three different levels. It appears that he was finally free to enjoy a modest life in peace.

The Next Three Decades for Michlmayr Johann Huber

By 1912, social and political conflicts throughout the sprawling Austro-Hungarian Empire filled the pages of the newspapers and when those conflicts erupted in August 1914 into World War I, Johann Huber and the Mormons at Parz 4 in Rottenbach were largely forgotten, except by their neighbors and the LDS Church. They were able to conduct their own religious affairs without interruption, and indeed were required to do so without the help of missionaries from other countries until 1919. Like so many other Austrian fathers, Johann Huber lost a son: Josef (born 1897) was killed on October 28, 1918—precisely two weeks before the Armistice. Family lore has it that he had been released from military service and was bound for home on a train in the Italian Alps when a sniper’s bullet took his life.

Johann Huber saw this view of Rottenbach whenever he walked from church in Haag back to the Michlmayr farm in Rottenbach, which he did until the very end of his life. The Michlmayr farm is behind the tallest tress at right. Photograph by Roger P. Minert.

Johann Huber saw this view of Rottenbach whenever he walked from church in Haag back to the Michlmayr farm in Rottenbach, which he did until the very end of his life. The Michlmayr farm is behind the tallest tress at right. Photograph by Roger P. Minert.

The records of the LDS Rottenbach Branch show baptisms of new members at a very humble but steady pace. By 1920 there were still fewer than twenty-five Latter-day Saints in Rottenbach and neighboring Haag.

That same year, a remarkable event took place that greatly enhanced the LDS Church in Rottenbach and Austria in general—the triple wedding of Huber’s daughters on May 21, 1920. Eldest daughter Theresia (born 1894) married Haag native Franz Rosner; Maria (born 1895) married Karl Hirschmann; and Aloisia (born 1898) married Konrad Hirschmann. The Hirschmann brothers were members of the Vienna Branch who had become acquainted with the Michlmayr family during their leave from the Imperial Army (they had requested an assignment to help with the Michlmayr harvest in the fall of 1918). Rosner joined the LDS Church in 1922.

The triple Huber wedding of 1920 was a grand affair in Rottenbach. The three couples are in the center with father Johann at the far right on the front row. Bertha is at the opposite end. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

The triple Huber wedding of 1920 was a grand affair in Rottenbach. The three couples are in the center with father Johann at the far right on the front row. Bertha is at the opposite end. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

While the Hirschmann brothers took their brides back to Vienna, the Rosners established a home in Haag. In 1927, the Rottenbach Branch found small rooms behind the apartments at Markt 38 (the main street and market square in Haag) and moved there from the Michlmayr farm. After twenty-five years, Johann Huber was released as branch president. In about 1935, Franz Rosner built a home across the main street from the Catholic Church in Haag and soon afterwards erected an addition to his home specifically for the LDS branch. The Saints moved into the spacious facility and met there until 1964.

Sometime in the 1930s, Michlmayr Johann Huber became a member of the National Socialist German Workers Party (later known as the Nazi Party), an organization growing at a rapid pace in an economically and politically impotent Austria. With the great majority of postwar Austrians, Huber probably longed for a union with a Germany that was fast becoming the dominant nation in Europe. Franz Rosner and several other members of the LDS Haag branch also joined the Nazi Party and enthusiastically greeted the arrival of the German army when Hitler annexed Austria in March 1938.[3]

Family photographs of Johann Huber's funeral in early October 1941. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

Family photographs of Johann Huber's funeral in early October 1941. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

By 1941, Johann Huber was the head of a very large family. Despite his eighty years, he still walked the two miles to church meetings in Haag. In late September of that year, he was picking apples when he suffered a heart attack and fell from the tree. He was carried to the farmhouse where he passed away a few days later. The photographs of the huge funeral procession that escorted his casket from the family home to the cemetery surrounding the Rottenbach Catholic church illustrate that he was a respected member of the community.[4] Copious flower arrangements were donated by family, LDS Church members, and neighbors, and the town band was on hand to provide the traditional musical ambience of a small-town funeral in Upper Austria. It would appear that any squabbles with neighbors (and there is no evidence that there had been any for thirty years) had been resolved by that time. Johann Huber enjoyed an excellent reputation in Rottenbach.[5]

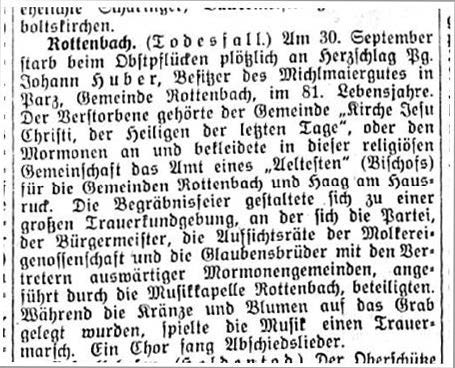

The regional Nazi Party newsletter announced the death of Johann Huber in 1941. Courtesy of Austrian National Library.

The regional Nazi Party newsletter announced the death of Johann Huber in 1941. Courtesy of Austrian National Library.

From liberal to national liberal to German national, Johann Huber concluded his political life as a member of the National Socialist German Workers Party. As such, he earned mention in the regional Nazi Party newsletter when he died:

Rottenbach (death). Johann Huber, owner of the Michlmaier [sic] farm in Parz in the town of Rottenbach, suffered a sudden heart attack while picking fruit at the age of 81. He was a member of the “Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints” (called Mormons) and was an “elder” (bishop) [sic] in that organization in Rottenbach and Haag am Hausruck. The funeral was a great event and was attended by party members, the mayor, members of the dairy association, and members of other Mormon congregations. The procession was led by the Rottenbach band; they played while flowers were placed on the grave and a choir rendered several numbers.[6]

Bertha Koehler Huber survived her husband by five years, dying in 1946 at the age of seventy-two as the venerated mother of this remarkable family. Somehow she had been successful in making the transition from the Protestant metropolis of Berlin, Germany, to the distant Catholic farming community of Rottenbach, Austria, with all of its provincial idiosyncrasies.

City girl becomes country farm wife: Bertha Koehler Huber at work in the later years of her life. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

City girl becomes country farm wife: Bertha Koehler Huber at work in the later years of her life. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

A remarkable life of more than eight decades had ended, but the memory and influence of Johann Huber likely will never cease. His descendants numbered more than 430 in 2015, and today they are members of many LDS congregations in Austria and the United States (see appendix C). The farm remains in family hands, and the small LDS Haag am Hausruck Branch meets in a beautiful building constructed for them by the Church on a main road on the outskirts of Haag.

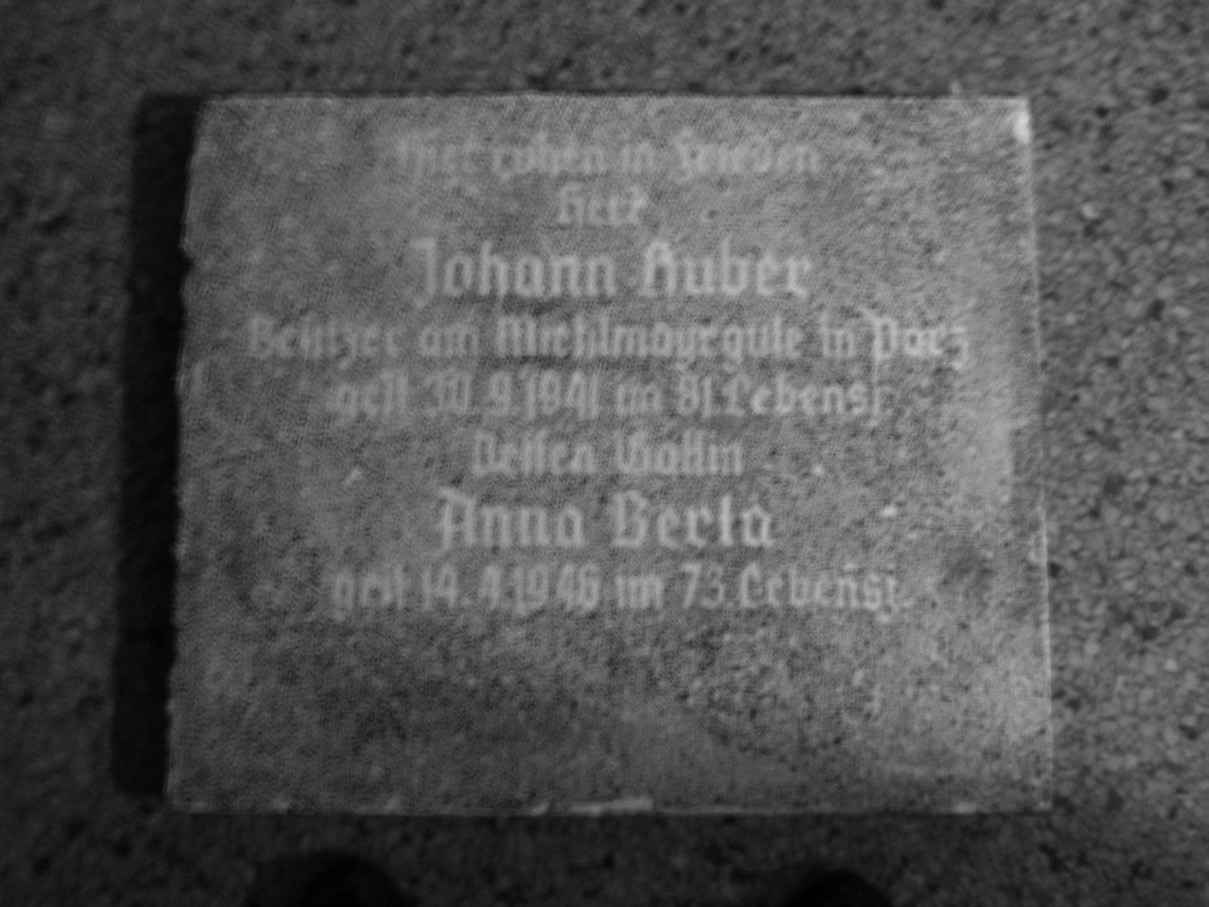

Johann Huber's gravesite disappeared during the construction of a funeral chapel in the 1980s, but his stone can still be seen at the Michlmayr home at Parz 4. Photograph by Roger P. Minert.

Johann Huber's gravesite disappeared during the construction of a funeral chapel in the 1980s, but his stone can still be seen at the Michlmayr home at Parz 4. Photograph by Roger P. Minert.

The Early Growth of the LDS Church in Austria

Nothing in the letters of Johann Huber suggests that he envisioned a significant presence of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in his native Austria. There is no evidence that his missionary efforts were designed to result in a huge congregation of Mormons in Rottenbach or anywhere else in Austria—he apparently wanted simply to share his new faith with other Catholics who had likewise been misled. He informed all listeners of what he had recognized as the restored gospel of Jesus Christ because he believed that they would benefit from knowing about it. He invited them to be baptized because he was convinced the true priesthood of God must be the basis of such saving ordinances.

Haag LDS Church. Courtesy of Kendal Babbitt Taylor.

Haag LDS Church. Courtesy of Kendal Babbitt Taylor.

As described above, the first persons to join the LDS Church due to interaction with Huber were his farm employees and eldest children. Then little by little, others heard or read about the new faith and came to Rottenbach to be informed, or possibly requested that Huber visit them elsewhere. As in Rottenbach, the LDS Church membership grew very slowly in two nearby towns and in distant cities:

Wels

Although not officially home to a branch until 1981, the town of Wels (fifteen miles directly east of Rottenbach) experienced Mormon activities as early as 1904. Teply attributes the first baptisms performed there to the missionary efforts of Huber.[7] Anton Josef Jungwirth and his wife Margarethe were baptized in Wels on April 30, 1904, but the official LDS Church membership records give the location of the event as Haag.[8] Another list of the Linz Branch members indicates that the Jungwirths were baptized in Oedt on the Traun River, eight miles downstream from Wels.[9] In both Linz lists, American missionary Winslow Smith (the same man who baptized Johann Tischler in Rottenbach in October 1904) conducted the ordinance.

Either the Jungwirth family (two daughters were baptized a few years later) or the converts in Rottenbach spread the word among friends, relatives, and others such that ten more individuals were baptized in five locations near Wels or Rottenbach by 1910. For some reason, however, the members in Wels were not successful in achieving the growth necessary to become a branch. According to Teply, the group functioned as an auxiliary of the Linz Branch, and missionaries provided the leadership.[10] Until at least 1920, the Latter-day Saints in Wels gathered in homes or in small rented rooms to conduct their worship services.

Linz

As seen above, LDS missionary activity apparently began in earnest in Linz, the capital of the Upper Austria Province, in 1910. The first LDS family in Linz was that of Peter Mareska, who had been baptized in Wels in 1906.[11] A few years later he moved to Linz and rendered substantial help to missionaries who ran afoul of the police there.[12] Several more persons baptized because of the testimony of Johann Huber found their way to Linz and joined the growing branch in that great industrial city on the Danube River, twenty-eight miles east-northeast of Rottenbach. Perhaps the most influential of those converts was Rudolf Niedermair. As another native of Wels, he had been baptized a member of the LDS Church in 1909.[13] Following his service in the Imperial Army during World War I, Niedermair moved to Linz and remained in military service.

After years of true and faithful service in the Church, the Saints in Linz were organized into a branch in 1921, and Niedermair was called as the first branch president. As discussed above, the Linz Saints supported Church activities in the Wels group for many years. By the time Austria was annexed by Germany in 1938, Niedermair had risen to the rank of major. He was still serving in 1941 when he died of blood poisoning, and his funeral was attended by many Austrian Saints, local citizens, and military personnel.[14]

Salzburg

Although this major Austrian city was located on the border of Germany just eighty miles from Munich, where there was a very strong LDS branch in 1900, there is no record of LDS missionary activity there until well into the twentieth century. The first member of the Church to make the forty-mile journey from Rottenbach southwest to Salzburg was Josef Duschl, a native of Haag. Duschl was actually a stepbrother to LDS missionary Martin Ganglmayer, the former born in Haag in 1874 and the latter in 1870. The boys shared the same mother but had different fathers.[15] Whether Duschl was first instructed about Mormonism by Ganglmayer or by Huber, his ongoing association with the Michmayr farmer led to his baptism several decades later: Duschl had married and was the father of two children by the time he invited Johann Huber to Salzburg for his baptism on May 12, 1920. Perhaps the secondary significance of that baptism is that it was Huber’s first such ordinance; he had never baptized anybody during his first twenty years as a priesthood holder. While in Salzburg, Huber blessed Duschl’s children, Adolf and Mariane, according to LDS practice. Duschl was joined in Salzburg by at least one person converted in Rottenbach, but he must have been pleased when missionaries were sent to Salzburg in 1923. Duschl served faithfully as the president of the Salzburg Branch through the difficult decades of the 1920s and 1930s, then during World War II. He died there in 1946, still the branch leader.

Vienna

Officially established as a branch of the LDS Church in 1909, the Vienna Branch history began with just a few members after the turn of the century. A mission report published in Der Stern in 1903 mentioned Eugen Weber serving in Vienna, but no details were given.[16] Again in 1904 and 1906 Der Stern noted the existence of an “Austrian District” of the Church. Activity in Vienna picked up substantially with the arrival of two missionaries from the United States in 1909, one of them being Charles W. Reese. This energetic American baptized more Austrians than any other missionary serving in the Dual Monarchy before its demise in 1918, including Huber’s eldest five children and several other persons in the Rottenbach Branch.

Two of Reese’s converts would later become Huber’s sons-in-law: Karl and Konrad Hirschmann, sons of a blacksmith. One day in 1909, Reese was walking along Mollardgasse in Vienna’s District VI and saw the two young men at work in their father’s smithy.[17] Reese stopped to initiate a discussion of religion with them and they were baptized in November of that year.

During its first decade, the Vienna branch struggled to find places to meet and to avoid interruptions by police and neighbors. Johann Huber had no reported involvement with the branch until World War I broke out in 1914. With all of the adult males in the Vienna Branch serving in the Imperial Army, there was nobody left to carry out priesthood functions in that city. Fortunately, Huber was available and able to travel by rail to Vienna on a number of occasions to bless the sacrament for those isolated Saints.

It was because of Huber’s interaction with the Church members in Vienna that brothers Karl and Konrad Hirschmann learned that the Michlmayr farmer had several daughters their age. Once the dust of the world conflict had settled and a new Austria emerged, the Hirschmann boys traveled to Rottenbach. Upon their return Maria and Karl were married on May 21, 1920, as were Aloisia and Konrad. The Hirschmann grooms took their Huber brides back to the Mollardgasse in Vienna and spent the rest of their lives there, substantially strengthening the LDS Vienna Branch. Their descendants are members of several wards in Austria’s capital city even today.

There is of course no way to know if or when the LDS Church units now found in Haag am Hausruck, Wels, Linz, and Salzburg would have been founded had it not been for the missionary efforts of Michlmayr Johann Huber of Rottenbach. Indeed, rural units such as Rottenbach are rare anywhere in modern Austria, and it is very likely that missionaries would not have been sent to that town to preach in virgin territory. The branch in Vienna might have survived the war years, but it would almost certainly have grown much more slowly without the Huber daughters and grandchildren living there.

The fact that Johann Huber could contribute to the formation of a branch of the LDS Church in a totally Catholic environment is unique in several ways. From the beginnings of the Church in German-language territories of Europe, missionary work was only really successful in Protestant lands. With the exceptions of branches in Munich (Bavaria) and in the Rhineland, LDS branches in Catholic lands were rare. Indeed, missionary work in Italy had been attempted and discontinued; Latter-day Saints in France and Belgium were few in number, and proselytizing had not even begun in Spain or Portugal.

Converts with the energy of a Johann Huber were also rare in central Europe. Karl G. Maeser comes to mind, but his influence was minimal in Dresden, possibly because he resigned his employment as a teacher soon after he left the Lutheran Church. Another reason for his minimal influence in Germany was because he immigrated to England within a year of his baptism to join with the Saints there. There is no way to know whether his dedication to the new faith would have led to the establishment of LDS branches outside of Dresden.

Gustav Weller was responsible for the spread of Mormonism in the Netze River Valley in northeastern Germany. As an avid missionary in the early 1920s, he is credited with having founded branches in five cities.[18] This was a most remarkable feat in the history of the LDS Church in central Europe.

For the most part, the growth of the LDS Church in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland was agonizingly slow before World War I, and converts came in most cases from the Protestant ranks. Church statistics for the year 1900 show branches in only three cities with populations more Catholic than Protestant: Munich, 82 percent; Cologne, 78 percent; and Saarbrücken, 54 percent.[19] In so many ways, Johann Huber and the Rottenbach (later Haag am Hausruck) Branch did not fit this mold. It was of course not by chance that Martin Ganglmayer returned to Haag as a new LDS missionary at the precise moment in time when Huber’s loyalty to the Catholic Church was waning. Huber’s new faith expanded in isolation, within a province that was almost totally dominated by the Roman Catholic Church.

Notes

[1] Lambert Lechner to Linz Diocesan Office, August 30, 1912, Diözesanarchiv Linz, CA/

[2] Linz Diocesan Office to Lambert Lechner, September 2, 1912, Diözesanarchiv Linz, CA/

[3] One photograph was taken in front of the Haag City Hall in November 1938 when a national vote was held to accept the annexation (Anschluss). The photograph shows branch president Rosner with his right arm raised in the Nazi salute. As an older man, Rosner stated that “none of the branch members were Nazis.” Franz Rosner, interview, March 16, 1974, 17, interviewed by Douglas Tobler, MS 18882, Church History Library.

[4] The Catholic doctrine that had forbidden the burial of non-Catholics or unworthy Catholics from being buried in church cemeteries was overruled by the 1868 constitution: All church cemeteries were classified as communal cemeteries. Huber’s grave was located at the southern edge of the property, likely next to his first wife, who died a member of the Lutheran Church. Bertha died in 1946 and was also buried next to Johann. All three graves were replaced in the 1980s when a small funeral chapel was constructed in that corner of the cemetery. There were no bones to be removed by then, because they had been buried in wooden coffins with no metal parts and no vault. The stone was retained by the family and can be seen at the Michlmayr farm today.

[5] Gottfried Huemer Huber, interview, August 21, 2012, interviewed by Roger P. Minert. In the photographs of Huber’s funeral, several small swastika flags are visible among the flowers on Huber’s casket. Adoptive son Gottfried Huemer Huber recalls seeing a party flag in the attic of the Michlmayr home as recently as 2000, but believes that it was removed during the renovation of the roof and attic. “Obituary of Johann Huber,” Heimatblatt 41, October 10, 1941, 8.

[6]“Obituary of Johann Huber,” Heimatblatt 41, October 10, 1941, 8.

[7] Heinrich Teply, Das Licht Scheint in der Finsternis, 99, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[8] Record of Members, LDS Linz Branch, 1904–1923, microfilm no. 38866, Family History Library, Salt Lake City.

[9] Record of Members, LDS Linz Branch, 1904–1923, microfilm no. 38866, Family History Library, Salt Lake City.

[10] Teply, Das Licht, 99, L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

[11] Record of Members, LDS Linz Branch, 1904–1923, microfilm no. 38866, Family History Library, Salt Lake City.

[12] Teply, Das Licht, 94, L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

[13] Record of Members, LDS Linz Branch, 1904–1923, microfilm no. 38866, Family History Library, Salt Lake City.

[14] Roger P. Minert, Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2011), 456–58.

[15] Martin Ganglmayer [KWJV-BZT], Family Tree database, FamilySearch, http://

[16]“West German Mission Report,” Der Stern, March 1, 1903, 70–71.

[17] Wilhelm Hirschmann, interview, October 5, 2011, interviewed by Roger P. Minert.

[18] The LDS branches in Driesen, Flatow, Kreuz/

[19]“West German Mission Report,” Der Stern, February 1, 1901, 40–41. Distribution by religion was calculated based on Meyers Orts-und Verkehrverzeichnis des Deutschen Reichs (Leipzig: Bibliographisches Institut, 1912; 2000), 230, 300, 660.