New Challenges at Home (1909–10)

Roger P. Minert, Against the Wall: Johann Huber and the First Mormons in Austria (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 143–60.

New Challenges at Home (1909–10)

As the owner of the largest farm in Rottenbach, Johann Huber was a very busy man. Add to that the religious conflicts that had already lasted more than a decade and his role as the leader of the small but active LDS Rottenbach Branch, and he had more work to do than a single parent could handle. He likely greeted the year 1909 still grieving for his wife of eighteen years, the mother of his twelve children. Unfortunately, things got worse for him before they got better.

Baby Karoline succumbed to an infantile illness four months after the passing of her mother.[1] Johann was now responsible for the work inside his house as well as on his large estate. Theresia, still only fourteen, needed to assume the management of the household functions, but was certainly aided by one or more domestic servant girls from nearby homes, as was the case on large farms in those days.

Renewed Police Investigations

In the meantime, unbeknownst to Johann Huber, the archdiocese reacted to the Altenhof Parish report by sending a request to the provincial government office in Linz:

In reference to the report submitted by the parish of Altenhof in the county of Ried on December 19, 1908, this office requests that legal action be taken to curb the disruptive activities of Johann Huber, Michlmayr in Parz, Rottenbach Parish, in support of the Mormons. This farmer has been creating trouble for some time and nobody has been able to stop him. Because he is not able to achieve any success in Rottenbach, he is taking his campaign to adjacent parishes.[2]

No response by the provincial government in Linz is available for study, but the Ried County Office may have received instructions from the former and responded with a six-page statement dated January 14. In this document, the county commissioner repeated verbatim almost all of the directions given in the spring of 1904, naming all eight men known at that time to be members of the LDS group in Rottenbach. Karl Planck then issued the same instructions given by his predecessor in 1904 to local and county governmental agencies: keep the office informed about the Mormons by name and their activities.[3]

The response from the Ried District Police Office featured a single sentence: “There are no Mormons within our jurisdiction.”[4] However, Officer Bromer of the Haag Police Office wrote a detailed report in which he named nine men known to be members of the Mormon sect—the last a certain Franz Holzinger, who was supposedly baptized in January 1909. Regarding recent activities by Mormon adherents, Bromer had little to report:

Religious meetings take place now and then in the home of Johann Huber, usually in the living room. They sing hymns and pray. The school-age children of Johann Huber usually attend the meetings. On one Sunday in February of this year, several young men from the neighborhood attended one such meeting. They had been there dancing and were invited by Johann Huber to attend; he told them that they had done nothing wrong or secret in attending the meeting.[5]

The baptism of the five eldest Huber children on May 16, 1909, in Rottenbach Creek caused quite a stir among the locals. A certain Johann Haager submitted a report to a local newspaper that came to the attention of county officials. Instructions were sent to the Haag Police Office to collect details about the event. Officer Bromer dutifully reported:

We can report that we couldn’t find anybody who could give us details about the baptismal ceremony conducted by the Mormons in Rottenbach Creek on May 16 inst. Even the writer of the newspaper article, Johann Haager of house no. 4 in Frei, didn’t know anything more about the event. Then I questioned the man known as the leader of the local Mormons, farmer Johann Huber, “Michlmayr,” of Parz 4 in the Rottenbach Parish. He indicated that the newspaper article in question was only partially correct. There were not seven persons baptized, but only five: his children Johann, Theresia, Maria, Josef, and Aloisia Huber, ages 16, 15, 13, 12, and 10 years. The ceremony was conducted in the Rottenbach Creek by Mormon Elder Karl Ries from Stuttgart. Home owners Josef and Ludmilla Anzengruber of house no. 20 in Haag were not baptized, as was assumed by local residents; they only witnessed the baptism. I then questioned the Anzengrubers and they confirmed Huber’s statement. Others who attended the ceremony were shoemaker Franz Holzinger of house no. 4 in Innernsee of Rottenbach Parish and shoemaker Leopold Zöllner, who lives on Burggasse in Wels.[6]

The records of the LDS Rottenbach Branch actually give the date of this event as May 9.[7] Although Johann Huber was a priest and according to LDS Church order could have baptized his own children, he probably had an official missionary conduct the ceremony for three reasons: to avoid attracting further persecution by functioning as a religious leader, to have the event officially sanctioned by the leadership of the Swiss-German Mission, and to avoid possibly violating Austrian law. The Leopold Zöllner named in the police report was already a Latter-day Saint, having been baptized in Wels three years earlier.[8]

On June 26, the Ried County Office summoned the following to appear: Josef Huber, Aloisia Huber, Josef and Ludmilla Anzengruber, and Franz Holzinger. They were charged with “conducting public religious activities associated with a church not recognized under national law.”[9] This was not a trial in court, but a hearing conducted by the county (in an auxiliary office in Haag), an entity empowered to administer penalties. Michlmayr Johann Huber made the following statement in his defense:

On May 16, the baptism of five of my minor children was conducted in the Rottenbach Creek near the Wimm in the parish of Rottenbach in accordance with Mormon practice. The ceremony was conducted by Carl Ries, a priest from Stuttgart. I deny breaking the law because I didn’t personally conduct the ceremony. I was only in attendance. Of my children, only the two youngest, Josef and Aloisia, were summoned [by the court] today. Johann Huber.[10]

Huber’s defense was to no avail: the county fined him twenty crowns and stipulated that he serve a term of forty-eight hours in jail if he failed to pay the fine. As in all such previous actions, he immediately appealed the ruling.[11]

At the same time, Franz Holzinger, a friend of the Mormons, appeared to defend himself against the same charge. He too was unsuccessful. The letter he wrote to the Ried County Office was actually written by Johann Huber and bears all of the hallmarks of the latter’s typical message style (and thus could hardly fool the county officials):

On July 5 I was summoned before the office in Haag because I had watched a Mormon baptismal ceremony that was conducted by an elder Karl Reess. I was fined 2 Crowns and am appealing that ruling! I’m very upset because I’m a Catholic and the law allows me complete freedom of conscience. Once I’ve passed fourteen years nobody can tell me if I can observe the ceremonies of a church that is or is not recognized by the government. The law can’t stop anybody. If that were possible, then freedom of conscience would be restricted! Certainly we haven’t gone back to the 16th century? Our laws in Austria don’t allow for a man to be fined just because he watches a ceremony conducted by a church that isn’t recognized by the government. I’m just a poor common laborer with a wife and five children to support. This ruling screams to high heaven. Therefore I request that the Linz Provincial Office revoke this penalty.[12]

The Anzengrubers also duly appeared and defended themselves as casual observers who were members of the Catholic Church. They, too, received fines of two crowns.[13] They too submitted an appeal to have the fine revoked and used almost identical wording. It seems that they copied Huber’s appeal. Two ideas are prominent in the depositions recorded by a clerk: “I have lived nearly three times fourteen years and this ruling restricts my freedom of conscience. Have we returned to the sixteenth century?”[14]

As could be expected, Johann Huber wrote yet another lengthy letter to protest the punishment. Two points made in his letter are noteworthy. Regarding his religious status, he wrote, “Because I’ve officially withdrawn from the Catholic Church, the state should treat me as totally independent in religious matters.”[15] Then, for the first time, he attacked the government in its treatment of citizens: “We believe that governments were instituted by God for the benefit of man. . . . We believe that no government can exist in peace without [making and] enforcing laws to protect the freedom of conscience of its citizens, as well as their rights to life and property.”[16] A part of the wording of this letter is taken verbatim from section 134 of the LDS scripture entitled the Doctrine and Covenants. Huber was likely quoting from a version published in 1903 in Berlin, which gives further evidence that Huber had access to and was acquainted with LDS Church literature.[17]

While it is hardly surprising that the Ried County commissioners would fine Johann Huber for his involvement in the baptism of his children, it isn’t at all clear why the county would fine three local adults who were lifelong members of the Catholic Church. Was this an attempt to dissuade Holzinger and the Anzengrubers from joining the LDS Church? Would this prevent other local residents from attending such ceremonies in the future? Would this convince the Mormons that such ceremonies should never again take place in Rottenbach?

Karl Planck Edler von Planckburg, county commissioner in Ried, delivered his ruling on August 6, 1909, regarding the four appeals to fines levied on July 5. He granted the appeals submitted by the three Catholics, but denied Huber’s appeal with this justification sent to the Linz Provincial Office: “The Mormon baptismal ceremony that took place in Rottenbach on May 16 was arranged by Johann Huber, the leader of the Mormons in Rottenbach. He invited Mormon elder Karl Rees [sic] to come.”[18] Apparently the county officials realized that Michlmayr Johann Huber was no innocent bystander. Without his request, there would have been no baptism in Rottenbach on May 9, 1909.

The Linz Provincial Office agreed with this ruling, reminding Huber that the religious affiliation of children ages seven to fourteen could not be altered; Huber, they maintained correctly, had knowingly violated that statute.[19] The decision was communicated to all involved parties, as well as to the office of the Wallern Protestant Church, because several of the children baptized that day had been affiliated with that church since Theresia Huber withdrew from the Catholic Church in 1904.

Johann Huber’s unwillingness to admit defeat led to a series of notices circulating from county to town to his home at Parz 4 in Rottenbach regarding the collection of the twenty-crown fine. After six weeks, Huber yielded and paid the fine and county records indicate that the money was forwarded to the public poor fund.[20] But though he lost this battle, he may have won the war. In the county archive of Ried and the province of Upper Austria, there are no more documents relating to court actions directed against Johann Huber.

On January 10, 1910, the Catholic Diocesan Office in Linz reported to the provincial government that Mormon missionaries from the United States were expected to arrive in the region soon. The provincial office reacted by informing the Ried County Office of the news and directing that the usual vigilance be exercised. It was believed that Mormon literature would also be offered to the locals.[21]

The Haag Police Office was well informed, evidenced by the fact that as early as April 11, 1910, Officer Bromer reported to the county office that whereas no Mormon activities of note could be reported from Haag or Rottenbach, he had heard that “Mormon leader Johann Huber would likely take another wife, a Mormon from Berlin, this summer.”[22] News got around fast in those days, and the rumor reported by the police proved to be correct.

Right upon the heels of the diocesan report, the Linzer Tagespost featured an article that reads:

M. Hafnergasse. We had received the first reports from you that so-called Mormon priests are going about Linz from house to house trying to gain converts. If such people are about, perhaps they have totally different intentions, such as casing out apartments for example. You should probably report the matter to the police. By the way, the following should be noted regarding this sect: they’re not officially recognized in Austria and may not hold public meetings or preach in public, etc. Initially, the Mormons embraced Christian doctrines, but since then they have moved on to the most immoral and heathen practices. In 1843, the organizer of the movement, Joseph Smith, supposedly received a revelation to institute polygamy. The doctrine has since been deleted from the Mormon sect. It is reported that the sect is spreading their propaganda, but is this actually happening in Linz?[23]

The Second Mrs. Johann Huber

Johann Huber likely knew about the LDS goings-on in Linz, but other matters occupied him at the time. Soon after the death of his wife, the president of the still-small LDS Rottenbach Branch began to wonder how he could find another wife to assist him in raising the children and managing the large Michlmayr farm. At the time of Theresia’s death in late 1908, there were no single LDS women living in or near Rottenbach. If he wanted to find a new partner who shared his faith, Johann would need to look elsewhere. But would he be able to find a woman who was both mature in the faith and willing to carry on the fight at his side? Not only would she be expected to move into the home of the forty-eight-year-old widower and his nine surviving children ages four to seventeen, but she might be a stranger to his culture and the local dialect—not to mention being considered an infidel by the native Catholics of Rottenbach.

Given the conditions on the Michlmayr farm in 1910, everyone who knew Huber would expect him to marry again. Remarriage was primarily an economic necessity, because the Huber girls were not of age to assume the permanent domestic leadership in cooking, baking, sewing, cleaning, and caring for the barnyard animals. But other factors put pressure on this man—especially religious concerns. The fact that his first wife had not joined the LDS Church in ten years of marriage gives rise to important questions. Had she never understood the gospel as taught by the Mormons? Had she resisted his invitations (or even urgings) to be baptized? Had the question caused tension and strife in the home? Why were her eldest children not baptized during her lifetime?

If Huber could find a second wife among the ranks of the German-speaking Latter-day Saints—even as far away as Switzerland or the large cities of northern Germany—he could avoid the risk of marrying a Catholic or a Protestant who might never join him in the new faith. From the beginning, he could enjoy the support of a partner who understood Latter-day Saint theology, assist him in teaching his nine children and in resisting the forces that had assailed him for years.

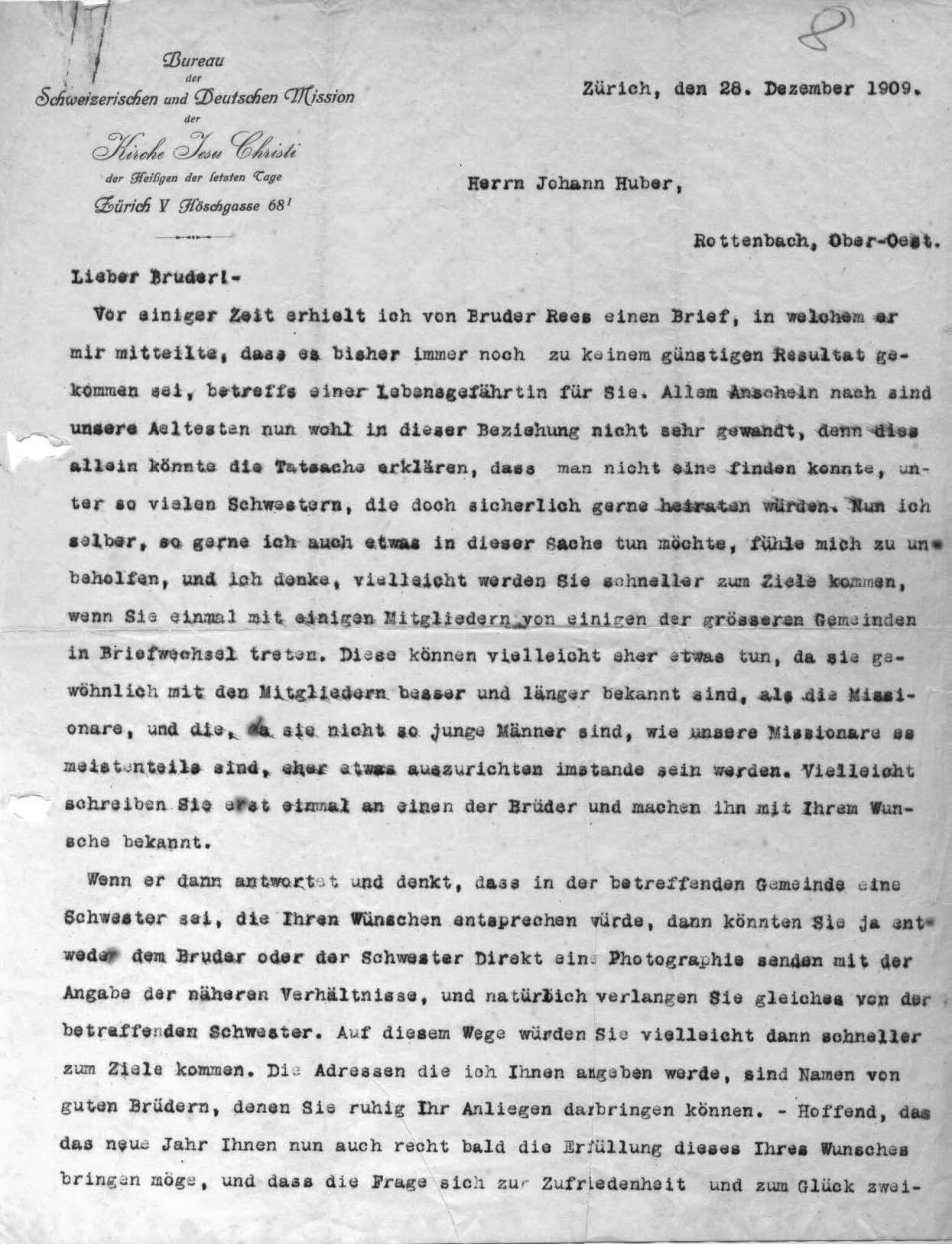

With this daunting challenge in mind, Huber turned to missionary Charles W. Reese, who had baptized the Huber children in May 1909. Perhaps the two discussed this question on that occasion. What little information we have regarding this weighty matter comes from a letter written by the president of the LDS Swiss-German Mission in Zürich, Switzerland. Thomas E. McKay had been called to that office only recently, but he did what he could to assist the Michlmayr farmer in his quest. Part of McKay’s letter reads:

I recently received a letter from Brother Reese informing me that he has as yet nothing successful to report regarding the search for a life partner for you. It appears that our elders are not very talented in this regard. Only this could explain why our elders cannot seem to find even one sister among so many sisters who certainly would like to be married. As for me, as much as I’d like to help in this search, I’m just not suited for such. I think you might make better progress if you began to write to members in some of the largest branches. They might be able to render better help because they’ve known other members better and longer than have the missionaries. Unlike the young missionaries, the members are better informed. Try writing to some of the brethren and introducing your request to them. If a brother responds in the belief that there is a sister in his branch who might be suitable for your purposes, then you could perhaps send a photograph to him or her with details of your situation. Of course, you would then request the same of the sister. This might be a more efficient way to reach your goal. The addresses I’m providing are those of good brethren to whom you can entrust details of your situation. I hope that the new year [1910] will offer you the achievement of this goal and that the fulfillment of your wish will be beneficial to two people. I also wish you success in all of your endeavors.[24]

McKay’s official duties did not include marriage brokering, but copies of the letter were sent dutifully to one man in Breslau, two in Berlin, and one in Hamburg—three of the largest LDS branches in Europe at the time. Perhaps the message also went by other means to missionaries assigned to large cities in Germany and Switzerland. We cannot know precisely who was involved in the negotiations, but a candidate for second wife was found far from Rottenbach—in Berlin, the metropolitan capital of the German Empire.

Back in 1909, the president of the German Mission took time to help Johann Huber find a wife. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

Back in 1909, the president of the German Mission took time to help Johann Huber find a wife. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

Anyone familiar with the inhabitants of turn-of-the-century Berlin and Upper Austria might consider such a union to be anything but promising: a big-city, recently baptized, formerly Protestant Berlin woman and a small-town, formerly Catholic Austrian man. Just to speak with each other in their vastly differing dialects of German might be a significant challenge.

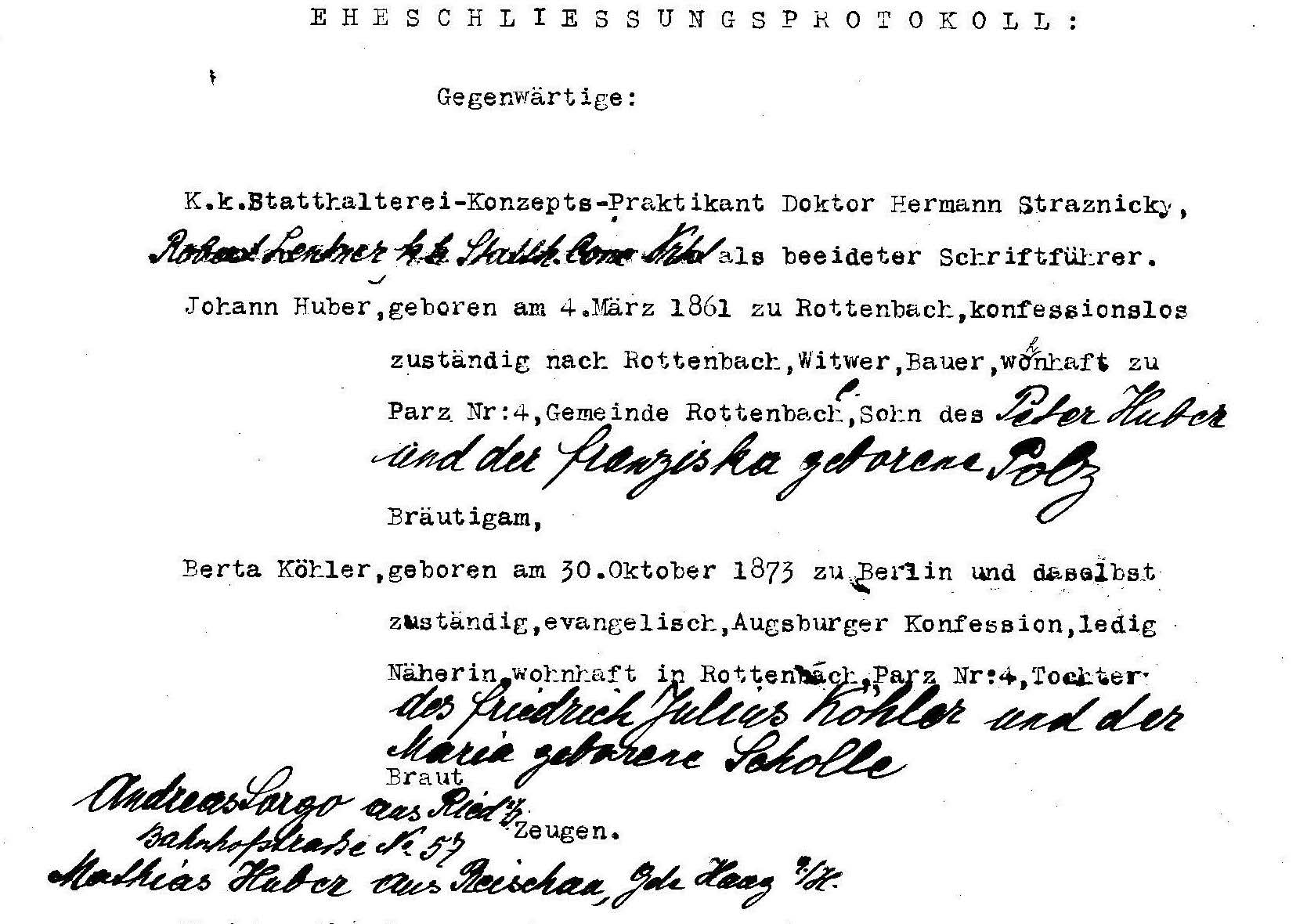

The official Ried County record shows that Johann and Anna Bertha were married in the county office on August 14, 1910. Courtesy of Bezirkshauptmannschaft Ried.

The official Ried County record shows that Johann and Anna Bertha were married in the county office on August 14, 1910. Courtesy of Bezirkshauptmannschaft Ried.

These concerns may explain the fact that candidate Anna Bertha Koehler arrived in Rottenbach on April 13, 1910, and lived on the Michlmayr farm for four months before marrying this controversial man.[25] The farmhouse was large enough to ensure proper conditions for these two as Miss Koehler weighed the possibilities of becoming a member of the family. (At the same time, he was deciding whether she was suited for the task.) None of the children ever wrote about this interim period, so we can only assume that Anna Bertha eventually felt good about her prospects for spending the rest of her life there—far from the huge city and the large LDS Berlin Branch that had welcomed her into the church.

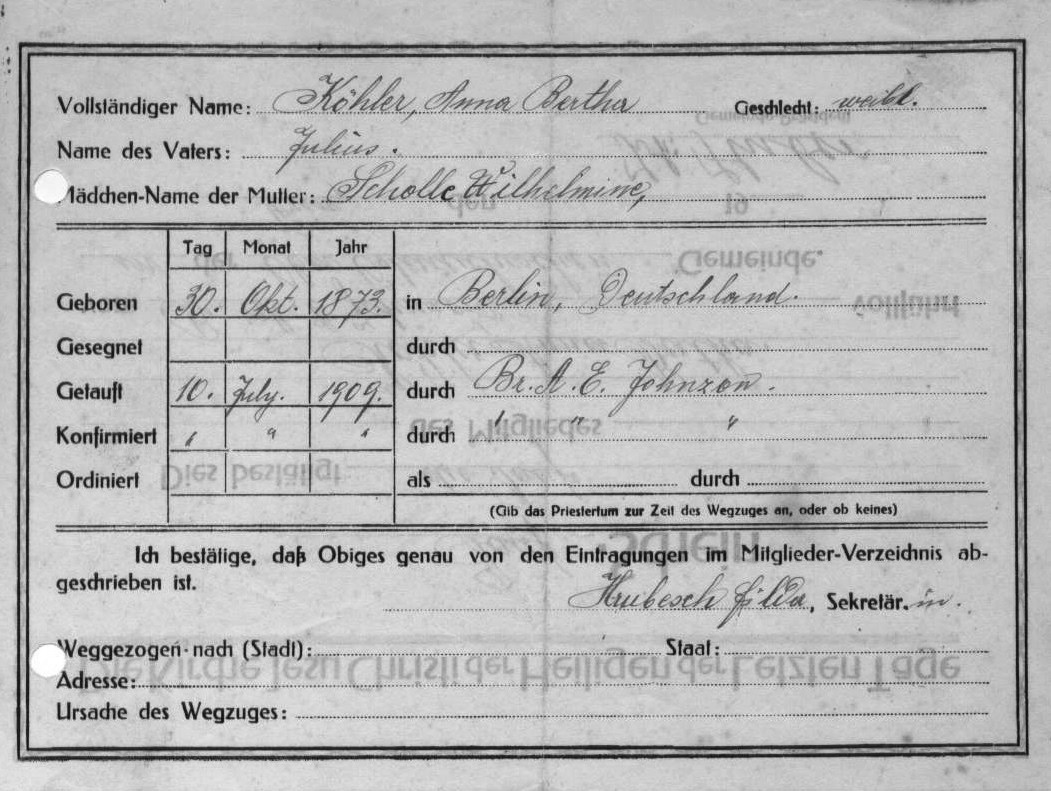

Born in Berlin on October 30, 1873, Anna Bertha Koehler was baptized into the LDS Church there on July 10, 1909.[26] Tradition has it that she and Johann Huber were married in Rottenbach on August 4, 1910, but the recent discovery of an official document sets the record straight.[27] The two were actually married in the office of the county government in Ried on August 14. Perhaps an unofficial Church ceremony was conducted previously or later on the farm by an American missionary sent from Germany or from Vienna, Austria.[28] In any case, the newspapers didn’t report anything about the event.

Bertha Koehler Huber as she appeared shortly after her arrival in Rottenbach.

Bertha Koehler Huber as she appeared shortly after her arrival in Rottenbach.

The couple had filed for a marriage license on July 17 and the bride presented an official birth certificate to county officials on August 8. The actual license described the groom as being konfessionslos (without religious affiliation) and the bride as evangelisch (Protestant). Those incorrect designations would have been provided by Johann and Anna Bertha. Did they make such statements fearing that their marriage petition would be declined if they told the truth? Possibly, but it is more likely that Bertha claimed Protestant status because her birth record would indicate that and because Huber’s four youngest children were Protestant in the eyes of the law.

Regarding Bertha (as she was called) Huber, the following statement written in 1969 by Johann Jr. survives:

Then Father married again—a sister from Berlin. Her name was Bertha Koehler. A missionary found her because my younger sisters still needed a mother. They married in August 1910. Then she had to get used to living on a farm, because she was [from the city].[29] [She was] a member of the Church. She was nice and a hard worker and kept the house in order. So life was good.[30]

Many years later, grandson Willi Hirschmann recalled that the older Huber children didn’t welcome Miss Koehler into the family with open arms, believing that they didn’t need another mother due to their maturity.[31]

Bertha Koehler joined the LDS Church in Berlin just thirteen months before marrying Johann Huber. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

Bertha Koehler joined the LDS Church in Berlin just thirteen months before marrying Johann Huber. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

The Departure of Pastor Josef Schachinger

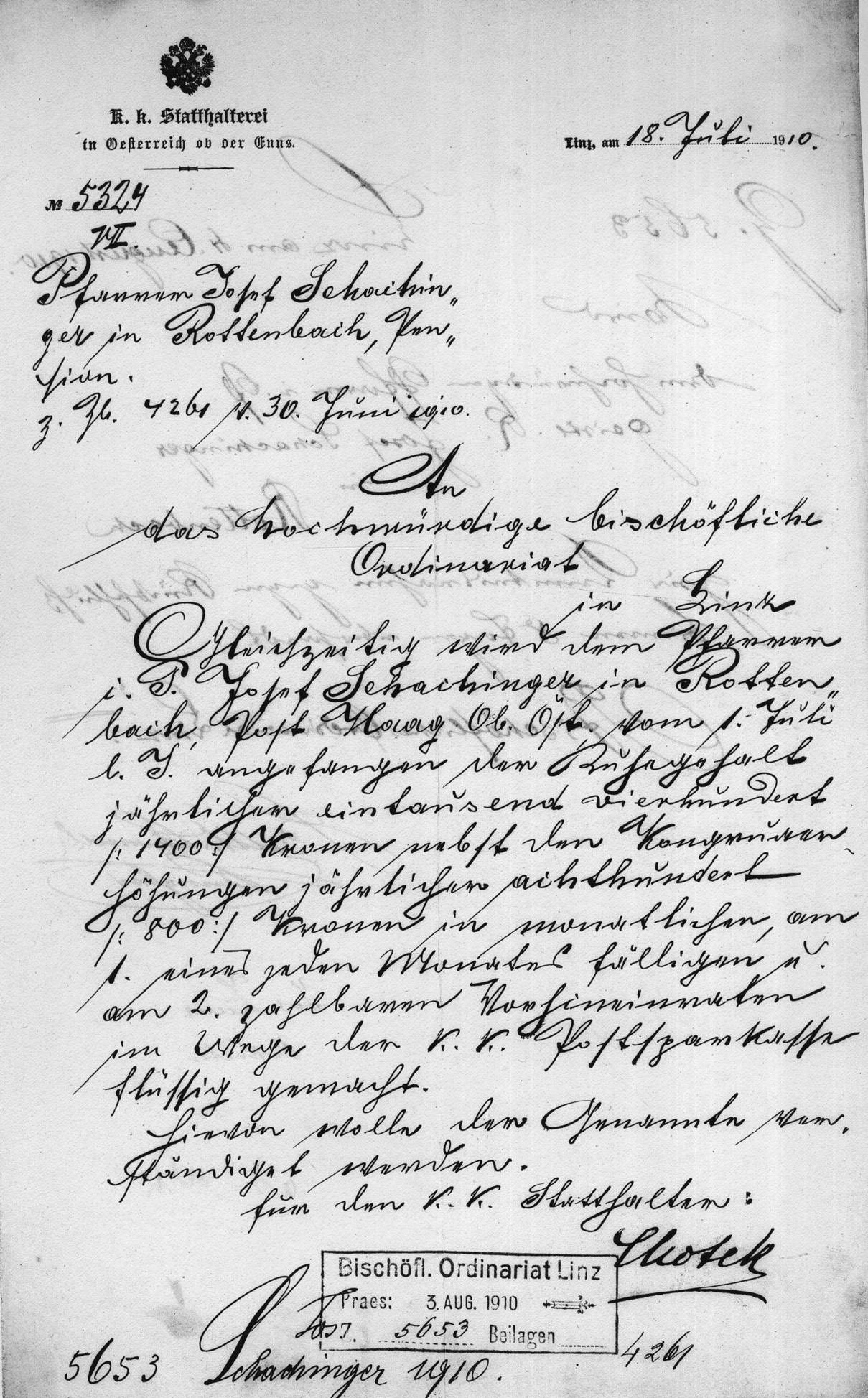

The fact that no Rottenbach correspondent reported the Mormon wedding to the local newspapers is likely a result of an event at least two men had anxiously awaited for as long as nine years—the retirement of Josef Schachinger. The provincial government in Linz wrote to the diocesan office in that city on July 18, 1910, to report that the veteran Catholic priest was to receive retirement benefits as of July 1.[32] The funding was established at 2,200 crowns per annum, to be paid in equal amounts on the first day of each month. It would seem that Schachinger immediately retreated from public life and gave up his battle against Huber and the upstart Mormons of Rottenbach.

The conditions of Pastor Schachinger's retirement were stipulated by the provincial office in Linz.

The conditions of Pastor Schachinger's retirement were stipulated by the provincial office in Linz.

Bertha Koehler arrived in Rottenbach at what could be called the tail end of a decade of persecutions heaped upon her new husband by individuals and agencies in and near Rottenbach. The end of those persecutions was in sight, and the Hubers could probably sense that, but they still had to take precautions in sharing their faith.

The family of Johann and Bertha Huber in 1910. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

The family of Johann and Bertha Huber in 1910. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

Notes

[1] Karoline Huber [KJ4C-K81], Family Tree database, FamilySearch, http://

[2] Linz Diocesan Office to Linz Provincial Office, January 12, 1909, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1909, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[3] Ried County Office to Ried District Police Office and others, March 12, 1909, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1909, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[4] Ried District Police Office to Ried County Office, March 16, 1909, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1909, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[5] Haag Police Office to Ried County Office, April 4, 1909, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1909, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[6] Haag Police Office to Ried County Office, May 29, 1909, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1909, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[7] Record of Members, LDS Rottenbach Branch, 1883–1923, microfilm no. 38866, Family History Library, Salt Lake City.

[8] Record of Members, LDS Rottenbach Branch, 1883–1923.

[9] Ried County Office to Josef Huber and others, June 26, 1909, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1905, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[10] Ried County Office, ruling, July 5, 1909, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1909, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[11] Ried County Office Ruling, July 5, 1909, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1909, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[12] Franz Holzinger to Ried County Office, July 6, 1909, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1909, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[13] Ried County Office, ruling, July 5, 1909, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1909, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[14] Ludmilla Anzengruber to Ried County Office, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1909, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach; Franz Anzengruber to Ried County Office, July 7, 1909, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1909, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach. The number 14 represents the age at which an individual in Austria could choose his or her own religious affiliation in accordance with the law of 1868 (cited above).

[15] Johann Huber to Ried County Office, July 6, 1909, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1909, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[16] Johann Huber to Ried County Office, July 6, 1909, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1909, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[17] Das Buch der Lehre und Bündnisse (Berlin: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1903), 482–83.

[18] Ried County Office to Linz Provincial Office, August 4, 1909, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1909, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[19] Linz Provincial Office Ruling, September 24, 1909, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1909, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[20] The county was compelled to have Rottenbach town officials go to the Michlmayr farm to collect the fine that Huber was so unwilling to pay and deposit the money into the town poor fund. It took five more weeks to get Huber to pay the fine. Rottenbach Town Hall to Ried County Office, November 21, 1909, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1909, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[21] Linz Provincial Government Office to Ried County Office, January 14, 1910, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1910, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[22] Haag Police Office to Ried County Office, April 11, 1910, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1910, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[23] Linzer Tagespost, February 6, 1910, 4.

[24] Thomas E. McKay to Johann Huber, December 28, 1909, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[25] The neighbors probably had plenty to gossip about during the four months before the Hubers’ wedding.

[26] Membership record of Anna Bertha Koehler, ca. 1910, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[27] Bezirkshauptmannschaft Ried, journal entry and marriage license for Johann Huber, 1910, Ried County Office, Ried, Austria. The birth certificate presented by Anna Bertha Koehler was issued by the Lutheran Church in Berlin, where civil registration did not begin until the year after her birth. She apparently decided not to mention that that she had been baptized a Mormon in 1909.

[28] A branch of the LDS Church had been established in Vienna in 1909. Elder Charles W. Reese was serving there at the time; it was Reese who had traveled to Rottenbach in 1909 to baptize the younger Huber children.

[29] Johann Huber Jr., autobiography, ca. 1939, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[30] Johann Huber Jr., autobiography, April 29, 1969, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[31] Wilhelm Hirschmann, interview, October 5, 2011, interviewed by Roger P. Minert.

[32] Linz Provincial Government Office to Linz Diocesan Office, July 18, 1910, Diözesanarchiv Linz, CA/