Huber’s Withdrawal from the Catholic Church (1902)

Roger P. Minert, Against the Wall: Johann Huber and the First Mormons in Austria (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 33–49.

Martin Ganglmayer was released from missionary service in January 1902. Just after his return to Salt Lake City, he addressed a long letter to the readers of Der Stern (the official German-language publication of the LDS Church) in which he preached the gospel one last time but made no reference to his work in Austria.[1] Johann Huber must have wondered if he would ever again see the man who introduced him to the new faith. In the meantime, the conflict between Catholics and Mormons raged on in Rottenbach.

In response to Schachinger’s 1901 year-end plea for help, the diocesan office in Linz instructed the priest to be gracious in dealing with Huber: “We have read your report. All indications are that this Mormon isn’t mentally normal. The only thing we can do is pray for God’s mercy and make sure that he doesn’t convert anyone else.”[2]

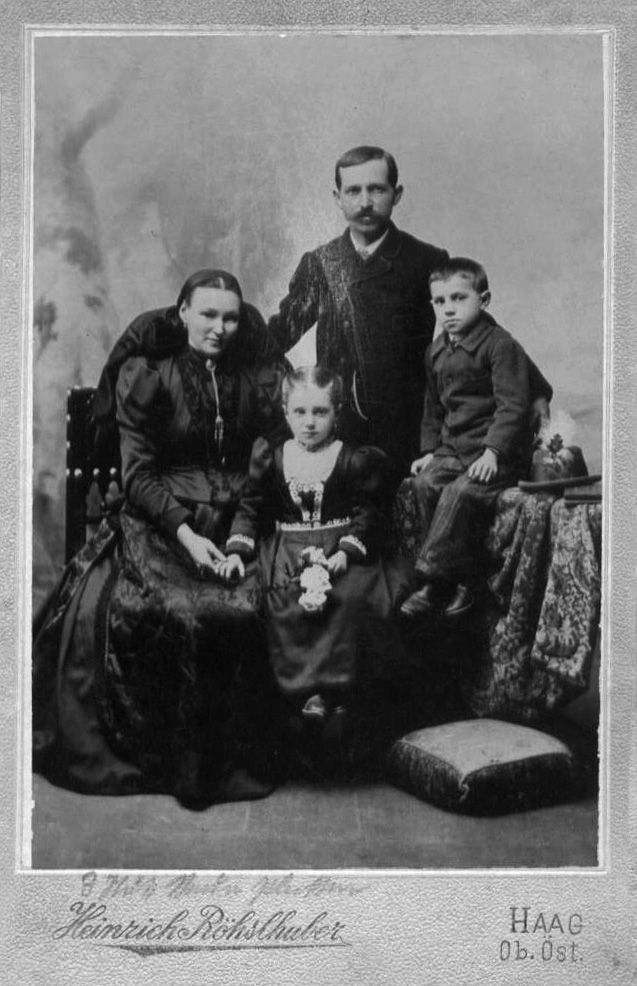

Johann and Theresia Huber with their namesakes Johann (born 1893) and Theresia (born 1894) in about 1898. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

Johann and Theresia Huber with their namesakes Johann (born 1893) and Theresia (born 1894) in about 1898. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

Less than two weeks later, Schachinger wrote to Linz again:

The undersigned dares to inform you that because of the [most recent apostasy] case, [the writer] is under great stress. If he doesn’t absolve them but refers them to the vicar, they’ll never confess again and will eventually fall victim to the Mormon. [Huber] is full of hatred toward the [Catholic] Church and the pastors. . . . Sometimes he goes alone to visit the sick, sometimes together with the so-called Mormon apostle or missionary, to convince the sick to join their “faith.” Then he claims to lay his hands upon their heads to heal them, etc. He did that with the son of the godparent who (being a good man) immediately sent for the pastor. The same with the wife of the bricklayer, who told the story to the vicar yesterday! [Huber] is very active. Thus the undersigned implores you to allow him to say whatever needs to be said without restriction—as he sees fit. [The writer] has been absolved in a previous similar case and asks for your permission ex post facto.[3]

The response from the bishop in Linz was a formal declaration: “I hereby grant you authority to act independently in this matter for a period of five years.”[4] Thus Schachinger was to enjoy unrestricted autonomy in dealing with the Mormon question in Rottenbach.[5]

The Religious Conflict Spreads to the Local School

After only five months in this Upper Austrian town, Schachinger had become quite upset with Johann Huber, the few other local Mormons, and the visiting missionaries. In order to gain control of the problem and with the full support of his supervisors, he next directed his attention to other members of the Huber family, particularly the two eldest children of Johann and Theresia. Named after their parents, son Johann was born in 1893, and daughter Theresia in 1894. Both attended public school in Rottenbach. Unfortunately for them, they soon became embroiled in the conflict between their father and the Catholic Church, specifically with regard to the question of school confessions. This must have already been a matter of public record in 1901, but escalated substantially in early 1902. Documents show that on February 24, the Rottenbach School Board filed a complaint with the school board in Ried, the county seat. The report itself has not survived, but the cover sheet of the transmittal has. A summary reads, “We will continue our court action against Johann Huber.”[6]

However, while attempting to compel Huber to send his eldest children to confession, the school board also showed respect for his rights under the national school law of 1868 and was willing to hear his side of the story. On April 3, 1902, the County School Board in Ried recorded the following deposition from Johann Huber, partially in third person and partially in first person:

[Plaintiff] Johann Huber, Michlmair [sic] in Parz, born at and a citizen of Rottenbach, a Mormon, married. He complained that the local [Catholic] church leaders are inciting his neighbors against him, telling them that they shouldn’t allow their daughters to work on his farm, because the members of the Mormon Church are the worst kind of people. Because the pastor in Geboltskirchen announced this from the pulpit on Easter Monday, I request that the county office protect me from these attacks. I also state that the pastor in Geboltskirchen is inciting people against me because I’ve joined the Mormon Church.[7]

The school board sent the deposition to the police office of Haag, and officials there dutifully investigated Huber’s claims. Their response to the school board is dated May 4:

In response to your instructions dated April 3, 1902 we can report that reliable statements from trustworthy persons have been received in secret; they say that Pastor Josef Schachinger of Rottenbach has indeed often spoken out in church against the growth of the Mormon faith and has warned people against joining that church. However, we couldn’t find any evidence that said pastor warned locals against allowing their daughters to work on Johann Huber’s farm. Nor could we find any evidence that Pastor Franz Bodingbauer in Geboltskirchen had aroused the locals against Johann Huber because of his conversion to the Mormon Church.[8]

The controversy regarding young Johann and Theresia and confession in the local public school would reemerge a year later and rage with intensity for many months.

Huber Rejects the Catholic Doctrine of Infant Baptism

Fortunately, there were in that year some positive events in the Hubers’ lives, such as the healing of young Johann from meningitis. He wrote his own story years later:

In 1902 I got really sick with meningitis. Dr. Steinbrückner came from Haag to treat me but he told my father he couldn’t help me and that I was going to die. Father telegraphed to Munich to get the elders of the Church of Jesus Christ. They came and laid their hands on my head and anointed me with consecrated oil and said a prayer. Then I got well and that was a great testimony for [Father].[9]

Still other positive events heartened the Hubers. But an otherwise blessed event on the farm brought new cause for conflict—the birth of their eighth child. Franziska Huber was born on April 8, 1902, but her father—who had been studying the New Testament with renewed interest—staunchly refused to have her baptized in the Catholic Church.

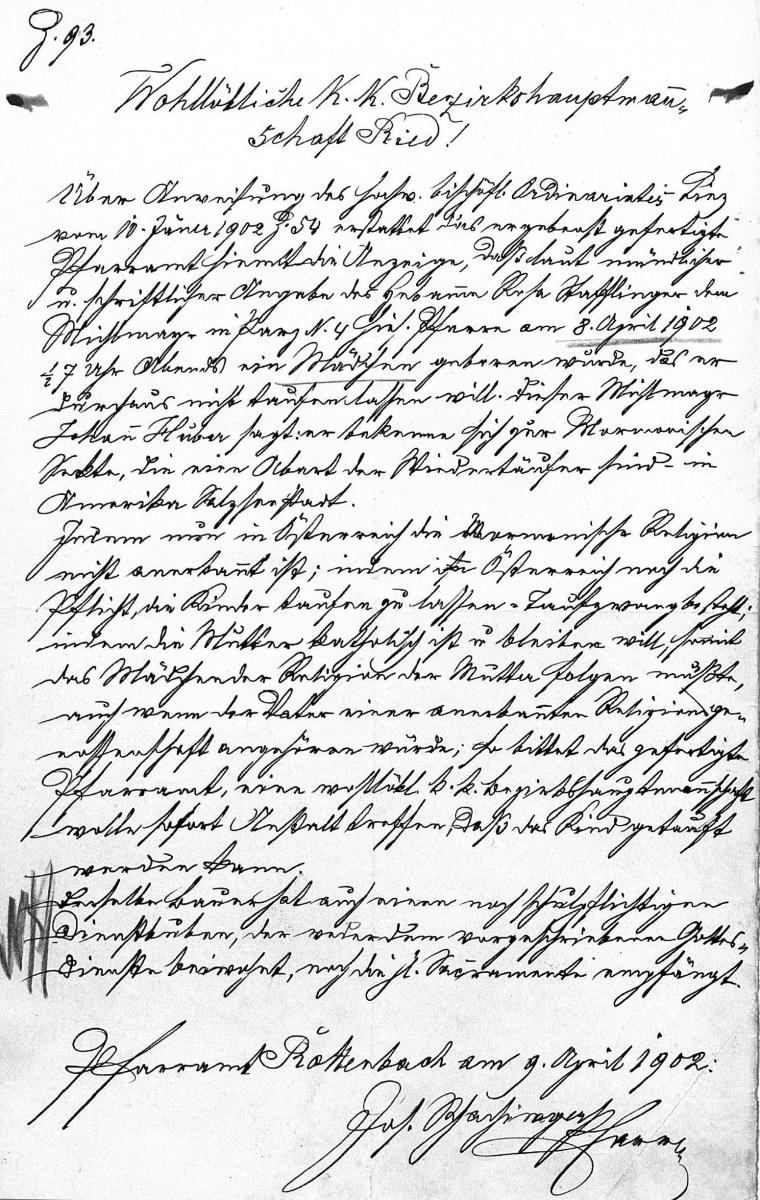

Pastor Schachinger was a fastidious penman whose writings reveal intense passion.

Pastor Schachinger was a fastidious penman whose writings reveal intense passion.

What complicated matters is that Huber had not yet withdrawn from the Catholic Church, for two main reasons. First, he was waiting for his wife to accept Mormonism and therefore withdraw with him. Second, he was trying to avoid as much persecution as possible by avoiding a public break with the Catholic Church.

But persecution still came. The day after Franziska Huber was born, Pastor Schachinger took action to counter this act of defiance, addressing his complaint to the Ried County Office:

Based on the oral and written reports of midwife Rosa Stafflinger, an infant girl was born to Johann Huber of the Michlmayr farm at no. 4 in Parz on April 8, 1902 at 6:30 p.m. He is determined to not have her baptized. This Michelmayr [sic] Johann Huber claims to be a member of the Mormon sect (a kind of Anabaptist faith) in Salt Lake City in America. The Mormon Church is not recognized in Austria and in Austria children are still required to be baptized [Catholic] if the mother is Catholic and plans to remain so.[10] Thus the infant girl must be allied with the faith of the mother, even if the father belongs to a different church. Your humble servant requests that the County Office order that the child be baptized [Catholic].[11]

Schachinger sent a similar message to the bishop in Linz.[12] Each letter suggests that he had communicated with the addressee on this topic as early as January and had been advised on how to proceed once the baby arrived.

Huber must have learned very soon that Schachinger had requested help from the county government to force Franziska to be baptized in the Rottenbach Church. In a statement filed in the county office, Huber’s argument was more religious than legal; he insisted that infant baptism was not taught by Jesus Christ or found in the teachings of his Apostles in the New Testament. Huber implored the county to exempt him from this requirement.[13]

The response to Huber’s plea was penned by the county clerk the very next day and was certainly received as a major disappointment. Quoting imperial laws dating 1854 and 1867, the county government reminded the Hubers that because they were all still members of the Catholic Church, they were required to have Franziska baptized according to Catholic ritual. They were ordered to do so within one week (i.e., by May 7) or face the penalties prescribed by law.[14]

Pastor Schachinger’s letters to the county office were proper and discreet, but he revealed his true emotions when writing to his ecclesiastical superiors in the diocesan office in Linz. By April 28, he was clearly becoming desperate:

I have tried on two occasions with kindness and love to bring the Mormon to repent, but am rewarded with curses such as “the worst devil” as you have heard from me before. Because I don’t possess enough pastoral intelligence, I sent the godfather to him yesterday and the former tried with all possible kindness and love, but he too failed. He got this response: “I’d be committing the worst sin if I allowed my child to be baptized. We read: he who has faith and is baptized shall be saved, but children can’t have faith, so they don’t need baptism.” People around here are curious about how this will turn out. If the baptism doesn’t take place soon, the Mormon will be triumphant. People will think he’s right and will go crazy, like the craftsmen who work for him, to whom he preaches for hours with Bible in hand. Johann Huber’s wife is still Catholic and received the sacrament at Easter, and his mother is too, but he brags about being able to convert his wife soon. The bishop should not underestimate this problem. The Mormons are preaching in homes in other parishes. . . . If they’re victorious, they could win additional converts. . . . I haven’t had a good day since I got here. . . . I don’t have enough pastoral intelligence and energy to resist this evil and must express my wish, indeed I must ask to be allowed to retire in May, to be replaced by another pastor with enough intelligence and energy to resist this evil. . . . Oh, if I had just known this before [coming to Rottenbach]!”[15]

Schachinger couldn’t know at the time that retirement was still years away. But, despite his exhaustion and whatever other weaknesses he may have revealed in his private letters, he apparently never displayed them to the public during his tenure in Rottenbach.

Huber Withdraws from the Catholic Church

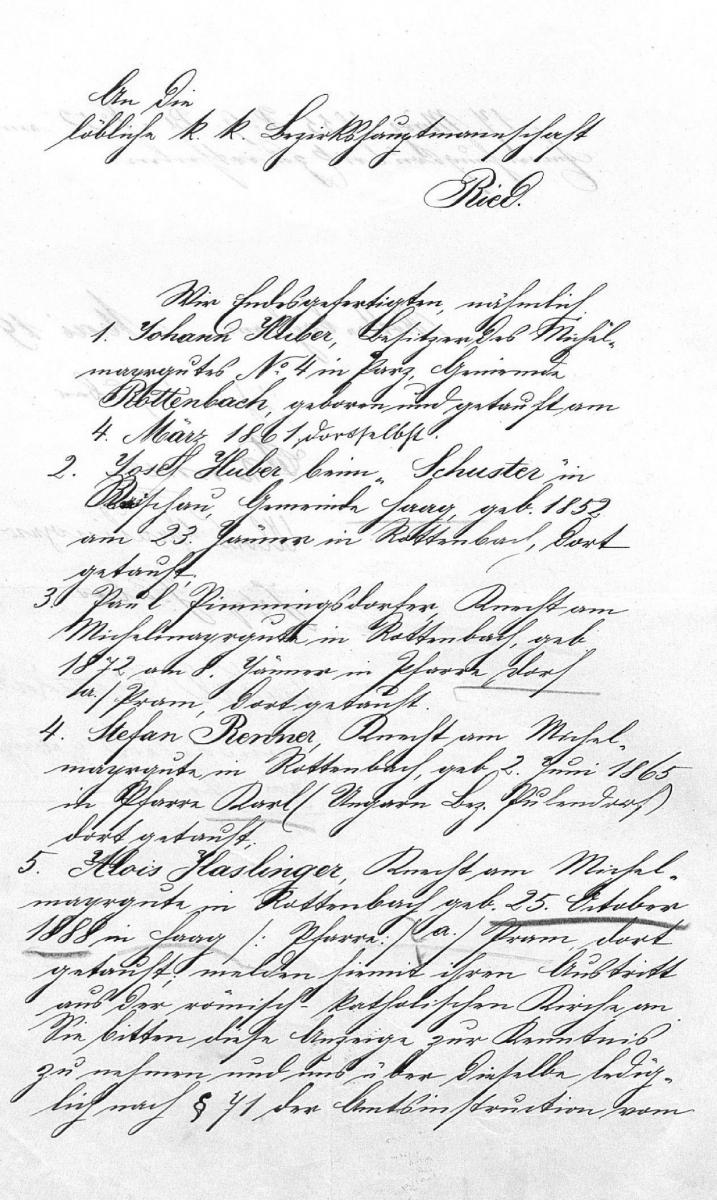

If Johann Huber had entertained any thoughts of escaping persecution by avoiding a public break with the Catholic Church, he abandoned those thoughts when he received the county’s negative ruling regarding his daughter’s religious status. On May 2 he followed legal procedures by submitting an application to the county office for withdrawal from the Catholic Church. (The church itself could not legally grant such a withdrawal.) Huber included four other men in his petition to leave the church: his elder brother, Josef, who had returned recently to the family farm from employment elsewhere; Paul Pimmingstorfer, who had been baptized recently and worked on the Michlmayr farm; Stefan Renner from Hungary, who was also employed on the farm; and Alois Haslinger (now thirteen years old), who was still an employee on the farm.[16] These men had come to Rottenbach in part because of Huber’s enthusiastic missionary efforts.

The application for withdrawal from the Catholic Church was quickly denied by the county—not because the government wasn’t willing to entertain such a request or wished to delay the process, but because the law very clearly required that each person submit such an application individually.[17] Huber’s second petition was granted, and on May 11, 1902, the Ried County office removed his name from the membership of the Catholic Church’s Rottenbach Parish.[18] However, as will be shown below, this change did not resolve the question of Franziska’s baptism in the Catholic Church.

On June 8, the Rieder Sonntagsblatt reported that four men had left the Catholic Church to become Mormons (only four, because Alois Haslinger was still too young). The report was also correct in stating that Johann Huber was resisting the baptism of his daughter as a Catholic.[19]

The first page of the petition of five Rottenbach men to withdraw from the Catholic Church in 1902.

The first page of the petition of five Rottenbach men to withdraw from the Catholic Church in 1902.

The First LDS Branch in Austria Is Established and Missionary Work Expands

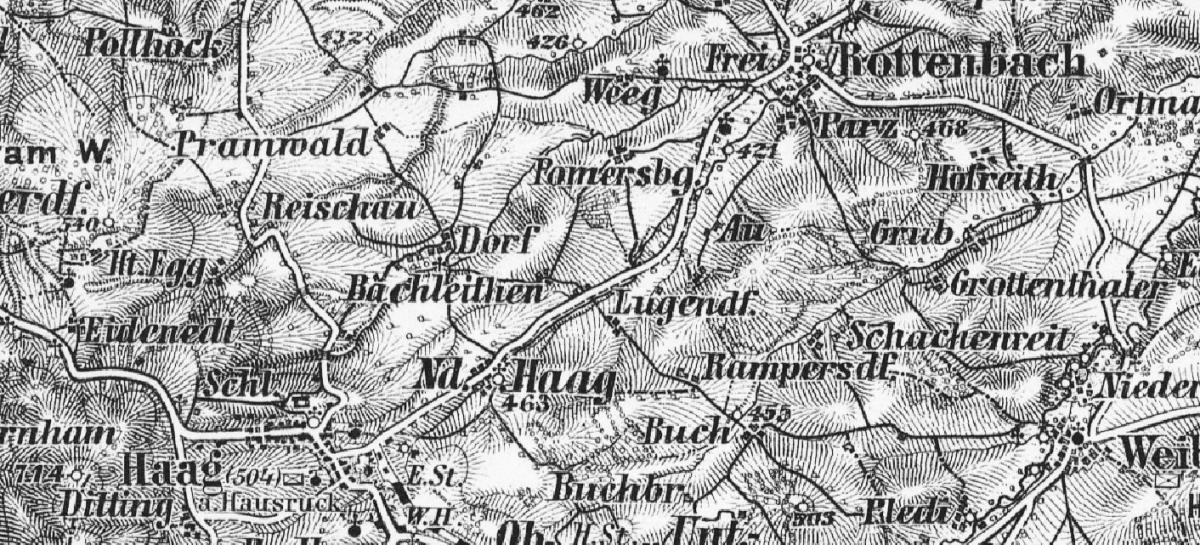

The town of Rottenbach (upper right) and the market town of Haag (lower left) are less than two miles apart.

The town of Rottenbach (upper right) and the market town of Haag (lower left) are less than two miles apart.

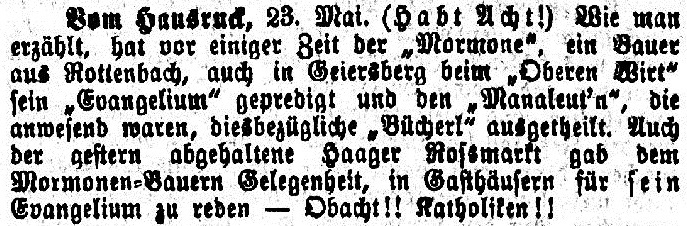

The records of the LDS German Mission report a significant entry in May 1902, but the wording is simple: “A branch was established in Rottenbach.”[20] From several other documents and family tradition, we know that the meeting place was a room at the Michlmayr farm. No document generated by any other office mentions the event, and newspaper correspondents did not hear of it at the time. This lack of notoriety was probably to Johann Huber’s advantage. After Johann Huber withdrew from the Catholic Church, the persecution continued. The newspaper Oberösterreiche Volkszeitung (published in Ried) announced the following to its readers:

From the Hausruck region. May 23. (Beware!). We are told that the “Mormon,” a farmer in Rottenbach, has been preaching his “gospel” recently in the Oberer Wirt Gasthaus in Geiersberg and has distributed “pamphlets” among the “devoted” listeners. The horse market held yesterday in Haag offered the Mormon farmer another opportunity to preach his gospel in local establishments.[21]

The same newspaper soon printed a second article about Huber. After informing the readers that the five men named above had petitioned the county to withdraw from the Catholic Church, the reporter offered this information—powerful evidence of Huber’s missionary zeal:

These [men] will now join the Mormons who give themselves the title of “Latter-day Saints” and revere polygamy. They also go to great lengths to win other converts to their cause by distributing literature and spreading their wisdom everywhere they can—especially in public houses. If nobody would listen to them or read their tracts, this illegal activity would come to its logical end in and of itself. Thus may all be forewarned![22]

"Habt Acht!" means "Beware!"

"Habt Acht!" means "Beware!"

The activities of the Mormons were reported again in October for one or both of two reasons: this new religion was a curiosity to the provincial inhabitants of Ried County, and there was a distinct fear that this new religion could mislead and thereby harm innocent people. The latter concern is reflected in the article published on October 10, 1902, under the title “A New Way to Marry”:

From the Hausruck area. October 7. (A new way to get married.) A rumor is going around that a totally new way to hold a wedding has been introduced in our local town of Rottenbach. If one wishes to marry the love of his life, he doesn’t need a church or a pastor. Even less important is the permission of the local government office. One simply needs to become a Mormon. The physical location of the church is represented by a grainary and the pastor and the county commissioner by a man known as “Michelmaier.” He has acquired no small amount of fame in Rottenbach and the vicinity as a zealous apostle of a sect called “Mormons” that is even banned in America due to its immoral practices. The story is told that this farmer who is filled with the Holy (?) Ghost conducted a wedding between a farm hand and a domestic servant using a handkerchief. The two are now living together in love and harmony under one roof and consider themselves officially married by the authority of this unknown ceremony. Evil tongues even claim that this “marriage” is blessed. We will be interested to see whether the Imperial and Royal county office makes a statement regarding this new kind of wedding that is not prescribed by law.[23]

The tone of this article is almost comical, but the final sentence seems to be a plea by the reporter that the county government take action against the Mormons. As with any newspaper article, this one could either have caused readers to fear and shun the converts to this new faith or to make sincere inquiries and possibly join the movement. History will show that the latter was a rare occurrence.

As if Johann Huber hadn’t yet experienced enough opposition to his new religious orientation and activities, the police office in nearby Haag issued a statement to the county on May 6 dealing with his missionary efforts. The first page of the text is missing, but the final page shows this wording:

The fact that parents who hire out their daughters as servants don’t want to send them to Huber is based on the report that as soon as he hires a servant girl, he supposedly attempts to convert her to Mormonism. In general, the entire population of Rottenbach and nearby towns is upset about Huber’s activities, because he refuses to have a child baptized who was born to his wife about three weeks ago. We’re still negotiating about the baptism of the above-mentioned child.[24]

The Argument over Franziska’s Baptism Is Finally Resolved

Huber’s successful efforts to withdraw from the Catholic Church on May 11 turned out to be merely a skirmish in this escalating war. He continued to disregard the county’s ruling to have Franziska baptized by May 7, relying on the fact that he was still within the two weeks granted him to appeal the ruling. In his newest letter to the county officials he stated what they already knew—that he had officially withdrawn from the Catholic Church and thus refused (again) to have his daughter baptized there.

The response to Huber’s petition of May 12 was issued by the county clerk, who made careful reference to the pivotal religious law of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in force since 1868: “In marriages in which the partners espouse different religions, the [underage] sons follow the faith of the fathers and the daughters that of the mothers.”[25] The interpretation was unmistakable: Franziska must be baptized Catholic because her mother was still a member of that church.

The county had ruled on the issue, but Huber again refused to yield. The conflict over Franziska’s baptism dragged on for more than six months. During that time, Pastor Schachinger wrote to his superiors in Linz several times, complaining that the county declined to take timely action, repeatedly granting Huber more time for appeals. One letter shows that his concerns were entirely consistent with his calling as the shepherd of the local flock:

Thanks to the latest delay by the court, Franziska Huber will be a full year old before she can be baptized. If she were to die before then, would she be allowed a church burial, if she were given an emergency baptism by the midwife? The Mormon [Huber] wouldn’t allow it, but would want to bury her himself as an elder. This is so aggravating![26]

Huber next went over the heads of county officials by appealing to the provincial government of Upper Austria in Linz, but the ruling of that office went against him as well. Finally, the county office in Ried ordered him to allow the baptism to take place. Under threat of legal penalties, he relented.[27] Little Franziska was more than seven months old when the baptism was performed on November 16 in the Rottenbach Catholic Church. Pastor Schachinger was likely both triumphant and relieved when he penned a report of the event to the county office that very evening:

Johann Huber sent me a message via the sexton: “He’ll allow his child to be baptized, but he won’t bring her to church. The pastor or the vicar has to come to his home to baptize the child, and we don’t need any godparent!” (Nobody wants to be the godparent!). The pastor sent a reply via the sexton: the sexton can bring the child to the church and the grandmother (the Mormon’s mother) can come along and be the godparent. . . . At 4:00 the grandmother came to church with the child for the baptism. She comes to mass every day and promises to remain true to the faith. The grandmother entered her name in the record under “godparent” and the pastor added a comment explaining the delay of the event.[28]

The events of 1902 were momentous and must have dominated life on the Michlmayr farm. The give and take between Johann Huber and his adversaries was constant, and each side could claim victories, but it is likely that nobody considered the question of Mormonism in Rottenbach to be resolved.

Notes

[1] Martin Ganglmayer, “An alle meine werthen Geschwister und Freunde in der deutschen Mission,” Der Stern, June 1, 1902, 167–70.

[2] Linz Diocesan Office to Josef Schachinger, January 10, 1902, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[3] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, January 23, 1902, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[4] Linz Diocesan Office to Josef Schachinger, January 27, 1902, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[5] Linz Diocesan Office to Josef Schachinger, January 27, 1902. The Latin text reads facultas dispensandi in casibus milu reservati.

[6] Rottenbach School Board to Ried County School Board, February 24, 1902, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried X L 1902.

[7] Johann Huber, deposition, April 3, 1902, Ried County Office, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried X L 1902.

[8] Haag Police Office to Linz County School Board, May 4, 1902, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried X L 1902.

[9] Johann Huber Jr., autobiography, ca. 1938, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection, Rottenbach, Austria.

[10] Baptism among Lutherans was also legal under Austrian law. Religions classified as sects did not enjoy legal status.

[11] Josef Schachinger to Ried County Office, April 9, 1902, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1902, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[12] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, April 9, 1902, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[13] Johann Huber, deposition, April 29, 1902, Ried County Office: Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1902, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[14] Ried County Office to Johann Huber, April 30, 1902, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1902, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach. In very correct but apparently contradictory wording, the county informed Huber that he had two weeks to appeal the ruling.

[15] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, April 28, 1902, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[16] Johann Huber and others to Ried County Office, May 2, 1902, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1902, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[17] Young Alois Haslinger had difficulty in his petition to the county: he was not yet fourteen years of age and in matters of religion could not legally represent himself. He appealed for an exception to this ruling, but was turned down. It is clear that Huber had been encouraging him in the effort, because the appeal was written by Johann Huber and simply signed by Alois Haslinger. Ried County Office to Johann Huber and others, May 3, 1902, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Ried VC 1902, XI E.

[18] Baptismal records, 1861, Rottenbach Catholic Parish, Rottenbach, Austria.

[19] Rieder Sonntagsblatt, June 8, 1902, 5.

[20] LDS German Mission Report, 1840–1898, LR 3168 v. 1, CRMH microfilm, German Mission History, Church History Library.

[21] Oberösterreichische Volkszeitung, May 30, 1902, 3.

[22] Oberösterreichische Volkszeitung, May 30, 1902, 3.

[23] Oberösterreichische Volkszeitung, October 10, 1902, 4.

[24] Haag Police Office to Ried County Office, May 6, 1902, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1902, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[25] Artikel 1, Reichsgesetzblatt, Gesetz vom 25, May 1868, ALEX Historische Rechts-und Gesetzestexte Online.

[26] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, August 27, 1902, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[27] Ried County Office to Johann Huber, November 6, 1902, Oberösterreichisches Landesarchiv, BH Grieskirchen 1902, GB Haag XI E Mormonen in Rottenbach.

[28] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, November 16, 1902, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/