From the Frying Pan into the Fire (1900–1901)

Roger P. Minert, Against the Wall: Johann Huber and the First Mormons in Austria (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 17–31.

After seven months of argumentation with his native Catholic Church and investigation into the new Latter-day Saint doctrine, Johann Huber was prepared to renounce the former and embrace the latter. Life following his Mormon baptism would never be the same, and the family’s comfortable lifestyle would be interrupted for a full decade. Despite fierce opposition, the LDS Church in Rottenbach would be officially established and would grow.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, there was, as yet, no unit of the LDS Church in Austria; the closest one to Rottenbach was the branch in Munich, Germany, some 110 miles to the west (as the crow flies—but a journey of several hours by rail).[1] This was one of the largest LDS branches in all of Germany, numbering nearly one hundred persons in 1900.[2] On April 21 of that year, Johann Huber took the train to the Bavarian capital city and was baptized there by a missionary.[3] The ceremony took place in a stream that ran through the public park known as the Herzoggarten just north of Munich’s city center.

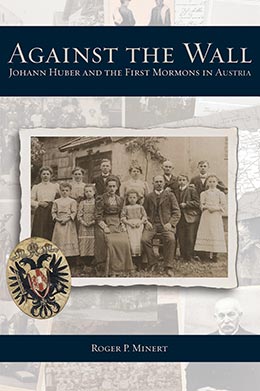

Elder Huefner's diary entry on April 21, 1990, mentions the baptism of Johann Huber. Courtesy of Jeffrey Huefner.

Elder Huefner's diary entry on April 21, 1990, mentions the baptism of Johann Huber. Courtesy of Jeffrey Huefner.

The missionary who baptized Johann Huber was Frederick George Ferdinand Huefner, a native of the kingdom of Wuerttemberg in southwest Germany. His diary contains the following entry for Saturday, April 21: “Had dinner at Bro. Dailer’s. Looked for John Huber from [Rottenbach] at Depot but missed him. . . . Met him at Bro Gronberger’s. I baptized him in Bach Herzoggarten and confirmed him also.”[4]

Four years later, Huber explained to a newspaper reporter his motivation for accepting Mormonism: “Because of the bad [Catholic] clergy. . . . After I quit attending mass, I began reading the Bible at home and my eyes were opened and I realized that these supposed priests had departed from the teachings of Christ.”[5]

Johann Huber as a Latter-day Saint

Thus Johann Huber became officially the tenth native Austrian to become a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—and immediately began to play the pivotal role in the growth of the church in that country for the next two decades.

It must have been quite clear to Michlmayr Johann Huber that his conversion to the LDS Church could be interpreted not simply as an alteration in religious conviction but as open rebellion against the Catholic Church and, as such, would cause new and significant difficulties in his life. As described before, those difficulties had begun even before his baptism but escalated quickly when he returned to Rottenbach from Munich. Elder Martin Ganglmayer, his friend and adviser, continued to send encouragement and instruction from Germany. On May 21, 1900, he wrote again from Frankfurt am Main:

You are so to speak the first fruits of my work in the mission field since I left my beloved family [in Salt Lake City] and all that is dear to me in Christianity in order to proclaim His restored gospel. . . . As long as you can stand fast and your faith is well rooted like an oak tree on the heath that must stand tall against wind and weather, this persecution will make you that much stronger in the gospel. In doing your duty, you’ll gain more character and dedication and become a strong pillar in this work of the last days.[6]

This letter indicates that Martin Ganglmayer was well grounded in his new faith and thus an example to Huber of a determined convert. The letter also provides important details about the life of Johann Huber, who was in most regards a typical farm owner in Upper Austria—for instance, the letter talks about Huber’s tobacco use. Convert Huber probably understood the LDS health standard known as the Word of Wisdom (a revelation received by Joseph Smith), namely that he needed to give up alcohol and tobacco (two mainstays of rural Austrian life). Ganglmayer reminded Huber in the letter of the importance of this standard, describing tobacco as “a fatal poison that has destroyed entire generations.”[7]

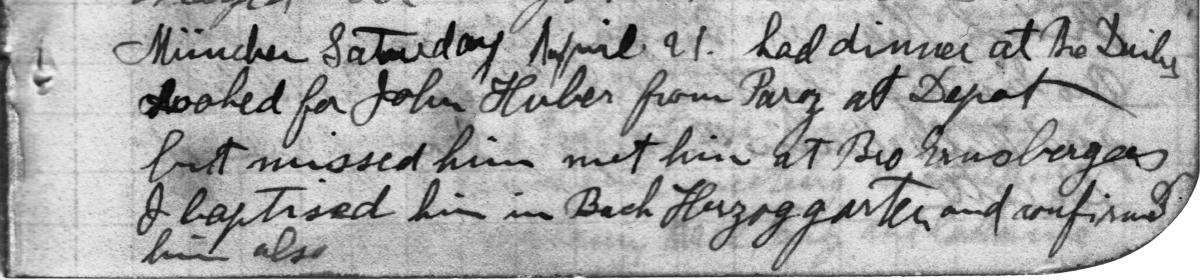

This membership record was filled out by Elder F. G. Huefner in Vienna and does not show the baptism date. Huber is designated a member of the "Upper Austrian" [Rottenbach] Branch. The certificate must have been issued after 1903. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

This membership record was filled out by Elder F. G. Huefner in Vienna and does not show the baptism date. Huber is designated a member of the "Upper Austrian" [Rottenbach] Branch. The certificate must have been issued after 1903. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

The question of ongoing missionary work in Rottenbach was also a topic in this letter. Ganglmayer encouraged his friend to spread the message of the restored gospel:

How’s your work doing? Is there a chance that somebody will listen to your message of truth? You can see how few embrace the truth when push comes to shove. But we don’t want any cowards in the ranks who are scared of suffering and dying for the gospel. It will someday be revealed just who accepted the testimony of Jesus Christ and maintained it in the face of hatred and mockery from the ignorant masses.[8]

This is an excellent piece of evidence that Johann Huber was actively sharing the news of his new faith with friends and neighbors, as attested in a letter written by relatives Josef and Franziska Schamberger in late 1900:

Dear brother Johann,

We’ve already read through your gospel [tracts] enough to be astonished about the principles explained therein. Please read the attachment that explains how we and you probably won’t be able to carry out this work. We returned again in a state of shock to the old gospel [Catholicism] that we’d been taught. Please don’t be angry with me. I’ll visit you soon and you can explain whatever you want to me.[9]

It is noteworthy that this letter expressed no animosity, so we can assume that at least the Schambergers did not exclude the new Mormon from their family circle.[10] Huber’s son, Johann, recalled years later the names of several individuals and families to whom his father preached this new religion. He indicated that very few of them were baptized and most moved away; nobody knew what became of them.[11] For numerous reasons, the LDS group in Rottenbach experienced very slow growth.

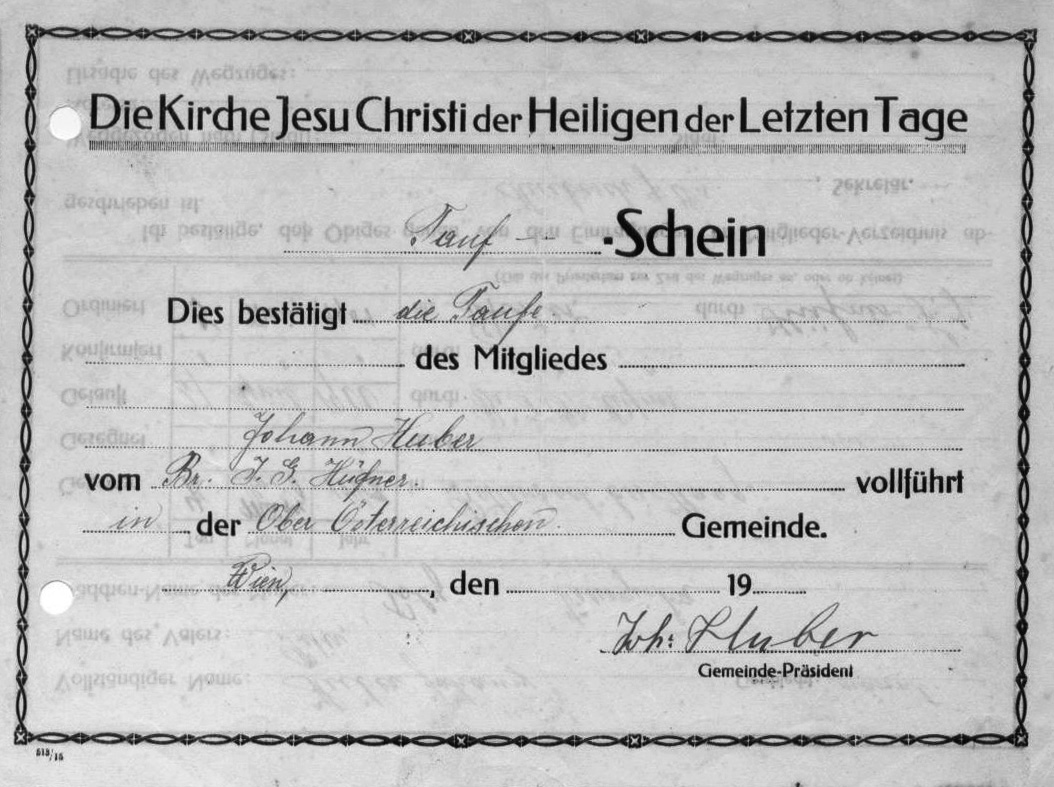

Johann Huber at about the time he was baptized into the LDS Church. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

Johann Huber at about the time he was baptized into the LDS Church. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

Just after the advent of the year 1901, Elder Ganglmayer again wrote to Johann Huber. Somehow the latter had understood that the missionary would soon be in Munich again and wanted very much to visit with him there. He seemed clearly desperate for LDS companionship by then and disappointed that his friend could not come south from Frankfurt. In his letter dated January 29, Ganglmayer wrote:

I was pleased to read the report by Brother Cannon who visited you in Haag several times.[12] I can see that you’ve been true and faithful in every aspect of the cause. I do hope that you’ll continue to enjoy the blessings of God in His kingdom and in His work. God has blessed you so much with light from above and has made it possible for you to understand a part of this plan of salvation so that you can discern between truth and error. That will allow any soul seeking the truth to see a ray of revelation. This conviction can then only be strengthened if for the light’s sake we are persecuted and shunned by those who perhaps were once our friends.[13]

Huber continued to correspond with Ganglmayer and in his letters apparently reported incessant persecution and shunning. On May 5, Johann was ordained a priest in the Aaronic Priesthood of the LDS Church by the same F. G. Huefner who had baptized him thirteen months before. Huber likely told nobody about this event, because the mere mention of the word “priest” among his Catholic friends, clergy, and neighbors in connection with the humble Michlmayr farmer would have been tantamount to heresy. After all, Johann Huber was still officially a member of the Catholic Church.

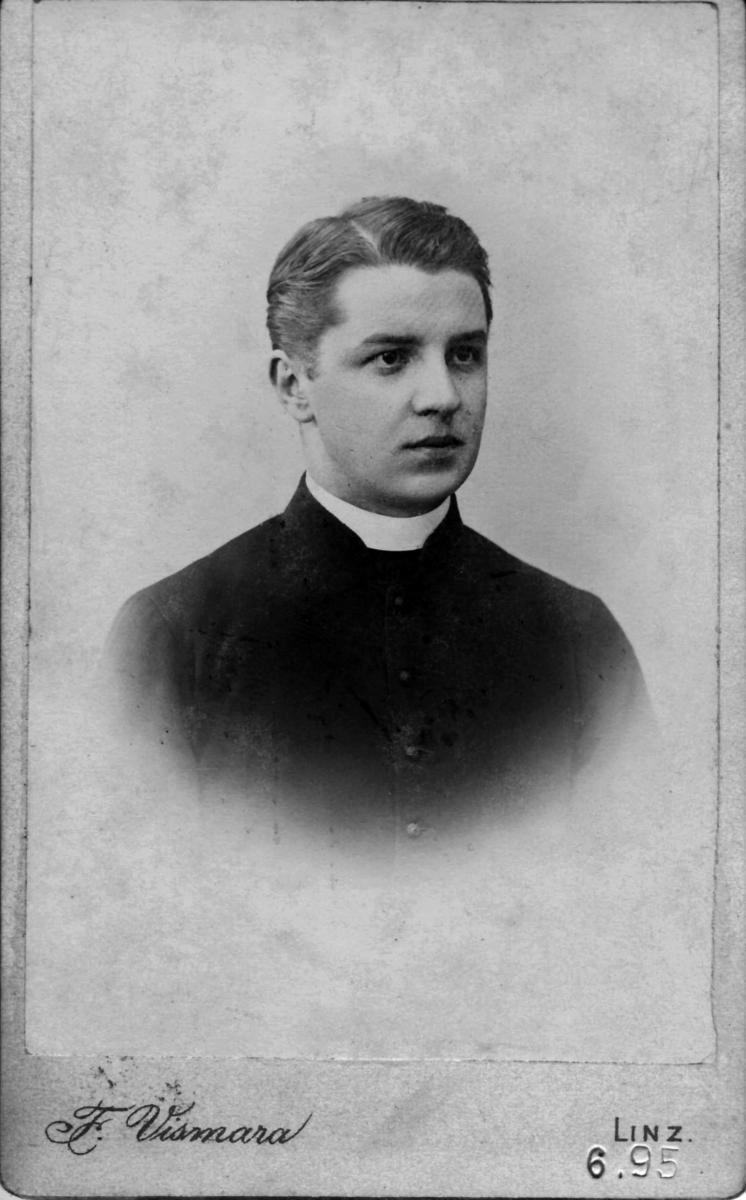

Vicar Karl Schofecker (shown here in a portrait from 1895) was probably responsible for Johann Huber's estrangement from the Catholic Church.

Vicar Karl Schofecker (shown here in a portrait from 1895) was probably responsible for Johann Huber's estrangement from the Catholic Church.

Schöfecker Keeps up the Pressure on Huber

On March 3, 1901, Rottenbach vicar Schöfecker sent a terse telegram to the diocesan office in Linz with this wording: “Pastor Aepflbaur of Rottenbach is dead. Funeral Saturday.”[14] Because no documents can be found written by or to Johann Aepflbaur by other Catholic clergy regarding the case of Johann Huber, it is assumed that this very old man (nearly 91 when he passed away) was not involved in the fray. With the pastor’s death, Schöfecker began a term as temporary pastor in Rottenbach. His tenure would last only a few months.[15]

The storm between Huber and Schöfecker had been raging for two years when the former wrote a lengthy letter to the vicar on July 28, 1901, seeing fit to lecture the priest on several topics. Apparently, Schöfecker had complained that Alois Haslinger, an eleven-year-old boy whom Huber had recently hired, was not attending school confession sessions with his classmates. (Alois was the son of Johann Haslinger, who had joined the LDS Church in Munich in 1895 and had since moved to Rottenbach.)

In his letter, Huber attacked the Catholic practice of confession, another evidence of his doctrinal quarrel with the Catholic Church: “So I would ask you if Christ taught this practice of confession. The Bible doesn’t teach us such foolishness. . . . My heart bleeds when I think about this stuff being taught to our children.”[16] Then he challenged the priest with harsh language that must have been interpreted as offensive: “Be converted. You are serving the god of men—not the god of the Bible. . . . If you are a friend of truth, then enlighten me if I’ve written anything false.”[17]

Regarding his own state of mind, Huber added this comment: “In closing I need to mention that I’m living a happy life and have received knowledge of the gospel. I live within the house of revelation, not outside of it.”[18] There is no record of Schöfecker responding to Huber’s remarks.

A New Catholic Priest in Rottenbach

Karl Schöfecker was clearly not afraid of Huber but may nevertheless have been relieved when he was transferred to the cathedral church in Linz on August 1, 1901. He was replaced by veteran pastor Josef Schachinger, another native of the province of Upper Austria. Born in 1845, Schachinger had served in five small Catholic parishes before arriving in Rottenbach. Whether his supervisors in Linz assigned him to Rottenbach because of the experience he would need in combating Mormonism is not known. Indeed, that situation may have had nothing to do with Schachinger’s transfer to the town, but for one specific reason, he may have been the wrong man for the job. Four months before his transfer—and apparently without any knowledge of his future—Schachinger had appealed to Linz for an early retirement. His letter of April 19, 1901, referred to previous requests in what apparently had been an ongoing discussion:

Currently it’s impossible for me to consult a county physician because I couldn’t bear the pain of the travel. And it would be just as expensive to pay for him to come to me as it would to pay for my substitute during my absence. Your humble servant hopes to be able to read the mass next Sunday despite severe pains and otherwise to survive somehow.[19]

Perhaps the Linz authorities transferred Schachinger to Rottenbach in order to give him easier access to a competent physician. In a letter to him dated August 8, the bishop in Linz expressed a hope that Schachinger’s foot and back ailments would be tolerable.[20] Nevertheless, the veteran priest arrived in Rottenbach on August 30, 1901, in very poor physical health and perhaps not in the mood to deal with a renegade parishioner.

Shortly after Schachinger’s arrival, the following relatively merciful entry in the history of the Rottenbach Parish was written:

It’s very sad that Johann Huber, the farmer at Michlmayr in Parz, has turned away from the Catholic Church and has been involved with Mormonism for about a year and a half. His brother and his farm laborers have gone along with him. Pastor Josef Schachinger has visited him twice and tried with love and tenderness to bring him back to the Church, but he has earned only insults for his efforts. The apostle Paul said that a heretic needs one or two warnings.[21]

This paragraph was written by Schachinger himself using the third person to refer to himself (as was the style of all of his letters) and treating the Huber case with some restraint. From these modest beginnings, Schachinger’s attitude toward Huber changed dramatically in a very short time. In fact, by October of that year, Schachinger was fully involved in a heated controversy surrounding Mormonism in Rottenbach.

Fortunately for the overworked parish priest, Johann Kreuzbauer soon arrived in Rottenbach to serve as vicar. Kreuzbauer too was caught up in the conflict and wrote to Linz for advice on how to deal with Johann Huber. Kreuzbauer’s emotional plea was written in what appears to be a loving but concerned tenor. He wrote that Mormonism had “sneaked into Rottenbach,” calling Huber’s conversion “an unbelievable error.”[22] According to the vicar, Huber “call[ed] himself a seer” and avoided associating with his neighbors; “the only visitor he has is a Mormon missionary from Munich, a carpenter by trade.”[23] (It would thus appear that Martin Ganglmayer had found his way back to see his friend and recent convert.) Kreuzbauer was most upset about the fact that the Huber children were being raised in the Mormon faith, as was a teenage boy, Alois Haslinger, who worked on the farm. When the vicar interviewed Alois in private, the boy told him “things that made me shudder. . . . He said that he had a dream in which heavenly beings appeared to him. He saw two bears that ate the boys who went to church. They didn’t harm him because he didn’t follow the vicar’s instructions. And then he saw many devils.”[24] Kreuzbauer’s letter ended with a plea for advice as to how to deal with the Huber family.

Later that month, Pastor Schachinger was aware enough of the Mormon crisis to write about it to his superiors in Linz for the first time. His message of three pages included these comments:

As you already know, a local farmer (called Michlmayr) joined the Mormon movement about a year and a half ago and a [Mormon] missionary comes here now and then (they say he is a carpenter from Munich). [Huber’s] wife still goes to [the Rottenbach Catholic] church every Sunday and his mother goes every day, according to the neighbors. The children must listen to their father when he preaches to them, etc. The undersigned thought it would be possible to visit him and encourage him in love to return to the church and this was done on Tuesday, October 8 with a heavy heart. The effort was in vain. The man responded with lots of Protestant philosophies. If you try to explain [church doctrine] to him, he doesn’t let you get a word in edgewise and he yells as if he were mad. It’s good that he doesn’t go to the pubs or he could do lots of damage among the farmers. Thus the undersigned didn’t achieve anything by this visit. We hear that a child will be born to this man soon. He didn’t want to have the last one baptized. The child needs to be baptized later (according to Mr. Kreuzbauer). How are we to deal with this? He’ll teach his children about Mormonism; he’s determined to do so. When the Galveston sank [on the Mississippi River], supposedly only four persons (Mormons) were rescued. He says that his own son was ill and Mormon missionaries laid their hands on his head and a half hour later he was healed. “Just try to do something like that!” he said triumphantly.[25]

The new Rottenbach priest may have been in constant physical pain, but he was dedicated to the struggle against what he considered to be heresy among his flock. His letter ends with this resolve: “But enough of that! Please forgive me for writing so much detail. This is like trying to clean out the Augean stables, but I haven’t lost my courage yet.”[26] The response from Linz two days later requested that Schachinger provide more detail about local conditions and about the work being done by Ganglmayer.[27]

In the meantime, the Michlmayr farmer was busy speaking to locals about his newfound faith. In November 1901, he wrote to the Berlin office of the LDS German Mission to request literature that he could distribute as part of his unofficial proselytizing. The response from Elder Huefner must have been disappointing to Huber: Huefner had just left the Berlin office for Stuttgart and was unable to procure the Bible and the “other testaments” requested, but he promised to ask Ganglmayer to do so when the latter arrived in Berlin. Elder Huefner did send Huber’s priesthood ordination certificate and indicated that it was meant for the Saints in Munich (and likely nobody else). Huefner would soon be on his way home to Utah and expressed his wish to see Huber again—in the next life if not in this one.[28]

From the onset, Johann Huber was a determined if unofficial missionary, a sign of true conversion. Because of this determination, he did have success in his work, and Mormonism began to spread. One of Huber’s first converts was a street cleaner named Johann Haslinger, a native of the neighboring Haag Catholic Parish. Once converted, Haslinger too had the missionary spirit and caused enough furor with his evangelizing that the diocesan office in Linz got word of him, and they inquired of the Haag pastor about the problem. That pastor, Michel Dobler, penned an adamant response, namely that there was absolutely no Mormon activity among his flock in Haag; all reports to the contrary were incorrect. He stated that Frau Kürner (the woman mentioned in the introduction above) had left Haag for the United States two years earlier. Regarding Haslinger, Dobler described him as “totally harmless to other people. One can see from his appearance from far away that he’s an idiot and incapable of rational thought.”[29] If Mormonism ever appeared in Haag again, Dobler was prepared to “counter it with all possible energy and to report such to his superiors.”[30]

The final document relating to the case of Mormon Johann Huber in 1901 was written on December 30 by Pastor Schachinger. It was again directed to his superiors in Linz and paints Huber in a very negative light:

On 20 December inst. the undersigned [Schachinger] made a second attempt to bring the Mormon [Huber] back into the Church. Following an impolite greeting, he allowed me to calm him and explain some things to him for a while. But when his employee came in, that all ended and he began to attack the Catholic Church and the bishop, saying he couldn’t tell the difference between his hands and his feet and that he was the worst possible liar, much worse than [deceased Pastor] Aepflbaur. “You’re the devil, the worst possible devil!” He said this in a terrible rage and in a loud voice he yelled at me when I was already leaving, “Satan, get thee hence!” And that’s what I get for telling him in love and kindness, even begging him that he should leave his erroneous ways and come back to the church. That poor wife! Those poor children! Such are the challenges of a pastor in Rottenbach![31]

It may seem from this impassioned plea that Schachinger was afraid of losing his battle against Mormonism in Rottenbach. His description of Huber as an unsavory character may simply have been an attempt to underscore the possibility that Huber could lead this tiny sect to expand. Could converts be found among the Rottenbach Catholics and significantly weaken the congragation? Pastor Josef Schachinger appears to have been a strong character in his own right—one who would prove a most formidable competitor in this struggle for the souls of men—but Huber refused from the beginning to bow to the power of his native church or its representatives. A classic duel between well-matched adversaries had begun.

Notes

[1] The organization of the LDS Church in Europe at the time consisted of branches grouped in conferences (later called districts). The first wards and stakes were established in 1961.

[2] Der Stern, February 1, 1901, 40–41. Only Hamburg had a larger branch in the LDS German Mission at the time (with 158 members).

[3] LDS Munich Branch, book 2, 1898–1900, 3–4, microfilm no. 38866, Family History Library, Salt Lake City.

[4] Frederick George Ferdinand Huefner, diary, April 21, 1900, Jeffrey Huefner private collection, West Bountiful, Utah.

[5] Else Spiegel, “Eine Mormonengemeinde in Oesterreich,” Salzburger Volksblatt, February 6, 1904, 17.

[6] Martin Ganglmayer to Johann Huber, May 21, 1900, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection, Rottenbach, Austria.

[7] Martin Ganglmayer to Johann Huber, May 21, 1900, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[8] Martin Ganglmayer to Johann Huber, May 21, 1900, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection. Ganglmayer indicated that he was free to preach in Germany, but he believed that such was not (yet) the case in Austria. This suggests that he understood that Huber might be in trouble with the law for preaching Mormonism in Rottenbach.

[9] Josef and Franziska Schamberger to Johann Huber, November 18, 1900, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection. This is the same Schamberger who received Huber’s support when he campaigned for a seat in the Upper Austrian parliament in May 1899.

[10] The Schambergers apparently lived some distance from Rottenbach, because the writer described recent weather conditions along the way.

[11] Johann Huber Jr., autobiography, ca. 1938, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection. Johann recalled traveling with his father as far as Hörsching (twenty miles to the east) to talk with the Jungwirt family about the gospel. They too moved away, but may have joined the Church later in Wels.

[12] The visits may have taken place in the Ganglmayer home in Haag or at the Michlmayr farm in Rottenbach. No verifiable accounts of these events can be located.

[13] Martin Ganglmayer to Johann Huber, January 29, 1901, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection; Johann Huber Jr., autobiography, ca. 1938, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[14] Karl Schöfecker to Linz Diocesan Office, March 1, 1901, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[15] Karl Schöfecker, service record, n.d., Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[16] Johann Huber to Karl Schöfecker, July 28, 1901, transcription by Gottfried Huemer Huber on March 31, 1958, Wilhelm Hirschmann private collection, Aggsbach Markt, Austria.

[17] Johann Huber to Karl Schöfecker, July 28, 1901, transcription by Gottfried Huemer Huber on March 31, 1958, Wilhelm Hirschmann private collection.

[18] Johann Huber to Karl Schöfecker, July 28, 1901.

[19] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, April 29, 1901, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[20] Linz Diocesan Office to Joseph Schachinger, August 8, 1901, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[21] Parish History, 1901, Rottenbach Catholic Parish, Rottenbach, Austria.

[22] Johann Kreuzbauer to Linz Diocesan Office, October 2, 1901, Diözesanarchiv Linz, CA/

[23] Johann Kreuzbauer to Linz Diocesan Office, October 2, 1901.

[24] Johann Kreuzbauer to Linz Diocesan Office, October 2, 1901.

[25] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, October 15, 1901, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[26] This reference is to the seven labors of Hercules. When required to clean out the Augean stables, Hercules circumvented the daunting task via a brilliant idea: he diverted a river that washed the stables clean.

[27] Linz Diocesan Office to Josef Schachinger, October 17, 1901, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[28] F. G. Huefner to Johann Huber, December 2, 1901, Gerlinde Huber Wambacher private collection.

[29] Michel Dobler to Linz Diocesan Office, December 10, 1901, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/

[30] Michel Dobler to Linz Diocesan Office, December 10, 1901.

[31] Josef Schachinger to Linz Diocesan Office, December 30, 1901, Diözesanarchiv Linz, Pers-A/