Conclusions

Roger P. Minert, Against the Wall: Johann Huber and the First Mormons in Austria (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 173–86.

Who Was This Johann Huber?

The massive documentation that has been collected regarding this remarkable man allows several reliable conclusions about his words, his deeds, and—to an extent—his thoughts. A fiercely loyal Austrian from the beginning, he exhibited a constant strength of conviction that inspires admiration. Not a man of flighty or capricious whims, he veered from a straight path only once in his life—when he learned of the teachings of a new and controversial religion. Like the classic Greek dramatic character, he had flaws such as a proclivity to anger (or a tendency toward quick reactions when offended) and a resolute if not stubborn nature. His conviction of the truth about religion allowed him to remain undaunted and unintimidated in the face of what he often called unrighteous oppression.

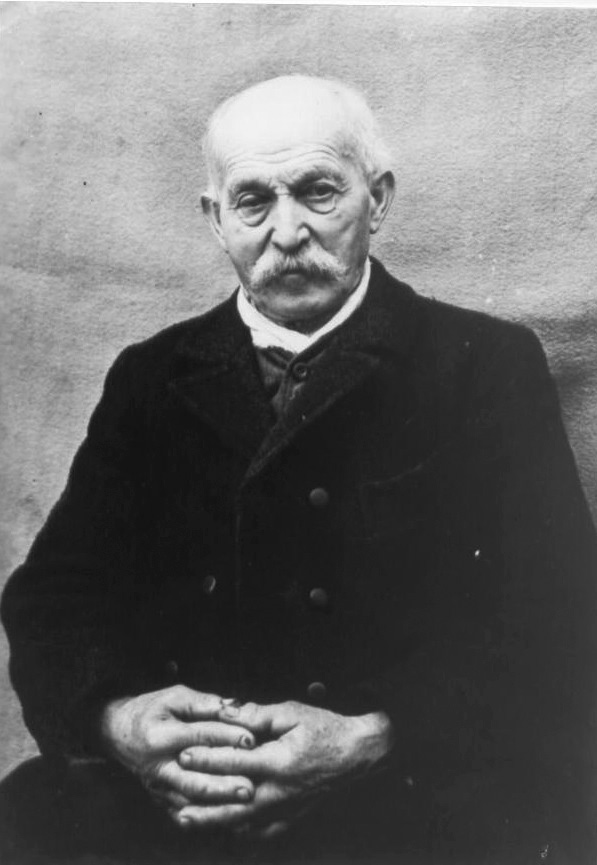

Grandson Wilhelm Hirschmann knew Huber in the 1930s and described him in these terms (see interview in appendix B): “He was about 5'6" and probably weighed no more than 160 pounds. He was a hardworking man who was up at three or four o’clock every morning. He had a majestic voice and never yelled or cursed. He had a fine reputation among the neighbors and was well known within fifteen miles from home.”[1]

It is easy to picture the Michlmayr farmer as an autocratic father—accustomed to supervising and leading his family with unquestioned authority—probably like the typical Austrian father of that era. If his nuclear family had been in disorder, his large farm could hardly have prospered. He was able to tolerate the fact that his first wife never officially embraced The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and he apparently never pressured her to do so. One can picture him telling young Johann and Theresia that the persecutions they were suffering in school would simply have to be accepted or ignored; their family would reject Catholic teachings, such as confession in the school, on the basis of correct principles. Other persons working on his farm and living under his roof (quasi-family members legally subject to the leadership of the family’s head) were apparently treated well in most cases, and several of them embraced the new religion. If Johann Huber had been the cruel and domineering boss the clergy claimed he was, the flight of laborers from the Michlmayr farm would have been constant and their replacement challenging.

Johann Huber as he appeared in 1939. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

Johann Huber as he appeared in 1939. Courtesy of Gerlinde Huber Wambacher.

As the heir to the largest farm in Parz, Johann Huber was essentially assured financial security if he simply managed the estate as previous owners had done for several centuries. He plowed, planted, and harvested in harmony with the owners of neighboring farms and the products of his estate were of sufficient quantity and quality to provide for his family and allow him to trade for goods and services not indigenous to the Michlmayr farm. He was a tireless worker, a trait apparent from his voluminous correspondence. One has to wonder how he could manage the estate while writing so many letters and interrupting work to answer frequent court summons.

Nothing about the way Huber did business in the neighborhood and the county gave rise to complaints by the neighbors, many of whom were invited to testify in court against him. Even before the conflict described above began in the spring of 1899, he demonstrated philanthropic ideals by donating more than 3,000 florins to the town welfare fund. As a man of integrity, he was only in his thirties when he served as a member of the financial committee of the Rottenbach Catholic Parish—not the kind of assignment bestowed upon a man of questionable integrity.

Johann Huber would have known everybody in his Parz neighborhood and probably also in his town of Rottenbach—perhaps even in the larger parish of Rottenbach with its several communities. Only those owners of farms and the men engaging in crafts and trades were his peers, but he seems to have enjoyed their association even after withdrawing from the Catholic Church. As much as the locals must have wondered what had overcome this Upper Austrian farmer, at least he continued to live an orderly life as much as possible. There is no evidence that he ever physically abused his wife, a child, a farm laborer, or a domestic servant. Those who tired of his incessant preaching were free to leave his employ, which some certainly did, according to several documents. Most neighbors probably overlooked his idiosyncrasies and chuckled over stories of his latest rows with authorities. It is possible that the number of social visitors at the Michlmayr farm decreased over the years, simply because some neighbors may have chosen to avoid the man who was surrounded by so much controversy and demonized by the Catholic priests.

We can’t tell just where and when Johann Huber became a follower of the liberal movement in Austria, but the historical documents make it clear that several of his peers were of the same political conviction. He was a devoted citizen, a veteran of national military service, and a dedicated political campaigner and voter. Huber and his political cronies looked forward to the day when the power and influence of the Catholic Church would be so greatly diminished as to render the Church politically impotent. Only then could free thinkers achieve political and social goals that contradicted traditional Catholic philosophies. Huber was loyal to Emperor Franz Josef, but wanted that same emperor to let go of his tight grip on Rome (as his reform-minded relative Emperor Josef II had done in the 1780s).[2]

Born into a family and a society that consisted totally of Roman Catholics, Johann Huber would have participated in every church practice and event experienced by his family and his neighbors. A mother like his, who walked one-third of a mile to morning mass every day until the last weeks of her life, certainly would have taught young Johann (who had lost his father when just five years of age) the tenets of the faith. Baptized for the removal of original sin the very day of his birth, he was taught the catechism and confirmed at age fourteen. For the next quarter of a century, he conducted himself as a good Catholic and thus fulfilled the expectations of his family and his neighbors in the parish. He married fellow parishioner Theresia Maier in 1890 and continued in the religious traditions of his small world.

It is unfortunate that the surviving documentation does not indicate whether Huber was a devout student of the Bible from his youth and thus perhaps for some time a dissenter in his mind. The fact that in 1904 he wrote to the newspaper that he “went out and got a Bible” in 1899 clouds the issue significantly. Why would he do so if he had been taught from the Bible all of his life? On the other hand, how could we believe that one of the wealthiest families in the parish had no Bible in the home? More important to this story is the question whether Johann Huber was in doctrinal disagreement with his church before he was attacked from the pulpit by vicar Karl Schöfecker in the spring of 1899 on political issues. Could he as a devout Catholic have left the church that day with such intense anger that he could soon resolve to never attend mass again (unless an apology was received) and without wavering maintain that belligerent stance?

When the LDS missionary and Haag am Hausruck native Martin Ganglmayer returned to his home in the summer of 1899, he encountered an unhappy Johann Huber ready to listen to the gospel of Jesus Christ as interpreted by the new American religion. Perhaps he had thoughts of this kind: “I can live without a church whose consecrated leaders humiliate the sheep of their fold from the pulpit on Sunday. In fact, I’ve had it with a church that preaches that infants are born under the damnation of original sin! And while I’m at it, to heck with a church that requires confession and offers forgiveness of sin—doctrines foreign to the Bible!” Or was it Ganglmayer—raised in the selfsame Catholic faith—who explained the erroneous base of such teachings to Huber for the first time? After joining the LDS Church in 1900 and officially withdrawing from the Catholic Church in 1902, Johann Huber rarely wrote about political questions again; he discussed primarily religious issues in his many letters to the church and the government.

Whatever the case may have been, by the late fall of 1899, Huber had a firm conviction of the truth of the doctrines of the Kirche Jesu Christi der Heiligen der Letzten Tage when Ganglmayer was dispatched to work in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Left to himself in matters of religion, Michlmayr strove to meet with other members of a church that was already ridiculed by the press in Europe; he was compelled to travel to Munich to worship and socialize with other Saints and was baptized there in April 1900.

Huber must have learned that many German converts to the LDS Church had emigrated to the United States as part of what was called the “gathering to Zion,” but not once did he mention such a possibility in his surviving letters. The sole occurrence of the word emigration is found when Huber insisted in a letter to the county that they cease prosecuting him. “Are you trying to get me to emigrate?” he asked. Why should he leave Austria? As the owner of a prosperous farm living among neighbors who respected him, why should he leave security and risk life in the foreign environment of the western United States among persons whose beliefs might indeed be identical but whose language and culture were quite strange? Would his wife, who apparently lacked LDS convictions, enjoy the new environment? Would he be able to learn English (a language not seen in any of his communications)?

Johann Huber probably owned LDS scriptures like these: Das Buch Mormon (below) and Lehre und Bundnisse; they were printed in Berlin in 1902 and 1903 respectively. Courtesy of Roger P. Minert Collection.

Johann Huber probably owned LDS scriptures like these: Das Buch Mormon (below) and Lehre und Bundnisse; they were printed in Berlin in 1902 and 1903 respectively. Courtesy of Roger P. Minert Collection.

Was Johann Huber an intellectual? Probably not in the classical tradition. Schooled with his peers through only the eighth grade, he apparently never engaged in any training in the trades or the crafts. Indeed, as the heir to the largest agricultural estate in the community, he needed only to know how to raise crops and deal with horticulture and animals (no small task to be sure). His many writings show clear patterns: his spelling is inconsistent, his syntax often incomplete, and his use of upper and lowercase letters imperfect. However, these deficiencies may have resulted in part from the intense emotional strain and haste under which many of his letters were written. If not an intellectual, Huber was in the very least a seeker. After embracing the LDS faith, he studied the Bible and the Church’s literature intently.

Huber’s disagreements with Catholic doctrines apparently began after his estrangement from the Church in 1899. The report he sent to the editor of the Deutscher Michel newspaper in Linz in 1904 contains a description of the events of 1899 and this interesting line: “I went looking for a Bible, a New Testament.” It is not known whether his study of the gospel of Jesus Christ was based only on the Bible or whether he also read literature distributed by Mormon missionaries.

Before 1907, two principal tracts were published by the LDS Church in the German language: Der Abfall vom Ursprünglichen Evangelium und dessen Wiederherstellung [The Apostasy from the Original Gospel and the Restoration] and Die Ewige Wahrheit: Ueber den Glauben und die Lehren der Heiligen der letzten Tage [The Eternal Truth: About the Faith and the Doctrines of the Latter-day Saints].[3] Each tract was printed in several editions in such cities as Basel, Hamburg, Berlin, and Leipzig, and editorial revisions were only slight from 1898 to 1907.

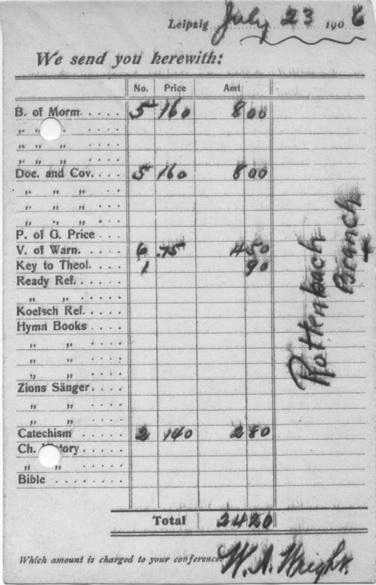

This receipt was sent to Huber with LDS literature in 1906. The total cost was an equivalent of about five US dollars.

This receipt was sent to Huber with LDS literature in 1906. The total cost was an equivalent of about five US dollars.

It would have been a simple task for Johann Huber to copy text and biblical references from the missionary tracts when he wrote to Pastor Schachinger or to county officials. However, a comparison of the passages he cited and those cited in the tracts is illuminating: of the fifty-six passages mentioned in the two tracts named above, only eight are found in Huber’s letters. On the other hand, Huber cited seventeen other passages from both the Old Testament and the New Testament that are not found in missionary tracts.

In addition, Huber wrote on several occasions about the Catholic doctrines of infant baptism and confession, as well as major events in Catholic Church history. None of those topics appear in the missionary tracts. One Huber letter mentions a “church historian named Morse,” whose writings were apparently available to Huber in German (nowhere is there evidence that Huber was acquainted with the English language).[4] All of this suggests that Huber did indeed study the Bible on his own, but there is no way to know what other literature he accessed in his attempts to find weaknesses in the Catholic Church’s arguments in favor of confession for elementary school pupils. This may be the extent of his scholarship, because no reference to classical literature or German-language authors is found.[5]

Whether the surviving documents allow a true or an erroneous description of Johann Huber, the tenth Austrian to join The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the first branch president of that church in Austria, one thing is clear: he must have been foreordained for the role that put his property, his reputation, and his very family in danger, but against which dangers he never faltered during at least ten years of unrelenting opposition. His is an inspiring story of faith and courage. As unofficial historian for the LDS Church in Austria, Heinrich M. Teply authored this commendation fifty years after Huber’s death: The history of the Rottenbach Branch “is inextricably connected with the person of Johann Huber, who is accorded the role of ‘pioneer’ of the LDS Church in Austria and to whom great honor is accorded even today among the church’s members.”[6]

Intellectually and spiritually, Johann Huber was at once an outsider and an interloper. He was so very different in his choices that to join the LDS Church as a rural Austrian in 1900 consigned him to lasting confrontations with his world; he departed his native society as a Catholic and re-\entered to confront it alone as a Latter-day Saint. He relinquished his ancestors’ heritage and initiated a new tradition. This remarkable man revered the great German reformer Martin Luther but would certainly not claim for himself the status of a modern Christian hero.

The town of Rottenbach recently placed historical markers on the old farms. To the left of this sign is the gate into the farm's courtyard. Photograph by Madeline Stoker.

The town of Rottenbach recently placed historical markers on the old farms. To the left of this sign is the gate into the farm's courtyard. Photograph by Madeline Stoker.

According to grandson Wilhelm (Willi) Hirschmann, the Michlmayr farmer never lost the desire to talk about Jesus Christ and the restored Church: “When we were walking home from our morning church meetings [in 1940], he would always stop and talk with anybody we met, . . . [and he] somehow always found a way to talk about the gospel.”[7]

Other Major Players in the Story of Johann Huber

Theresia Huber is the silent partner in the story. Because we have no documents from her hand and no eyewitness testimony, we can only speculate about her attitudes toward her husband’s new faith (and, possibly, her own new faith). She evidently cooperated in her husband’s efforts to leave the Catholic Church in which both had been raised, but she never attended the Lutheran Church to which she transferred her membership and very likely made the move merely to spare her children trouble in school. In the same vein, her attendance at mass in her last years (as reported by Schachinger) may have been nothing more than an attempt to maintain a good relationship with her neighbors. What she actually thought and believed regarding religious doctrines cannot be ascertained at this time. In any case, she had not been baptized into the LDS Church when she died in 1908.

Missionary Martin Ganglmayer returned to his family in Salt Lake City, Utah. Sometime before 1920 he moved to Los Angeles and spent the rest of his life there. As an active member of the church, he died there in 1939. There is no evidence that he maintained contact with Huber after 1906 and no way to determine whether he ever learned of the expansion of the church from Rottenbach. No descendants have been located as of this writing.

Pastor Josef Schachinger arrived in Rottenbach in 1901 in a poor frame of mind. His appeal for early retirement having just been rejected by the Catholic bishop in Linz, he found himself dealing with a man of radical thought and firm constitution. It seems in his many letters that Schachinger was genuinely concerned about the spiritual welfare of all of his parishioners—including Johann Huber. His apparent fears that Mormonism could suck the life out of his parish were distinct and his efforts to stop the movement dedicated and intense. His superiors in Linz were probably quite pleased with him for continuing this fight despite his lingering physical maladies. Indeed, it’s very possible that Schachinger’s attacks on the Mormons (including very likely several of the letters written anonymously to local newspapers) actually prevented members of the Rottenbach and Haag Catholic parishes from becoming converts of the LDS faith. Schachinger remained in Rottenbach as a retired priest. He died there in 1918.

Vicar Karl Schöfecker played a short-lived but crucial role in the emergence of the LDS Church in Rottenbach. It was likely this outspoken young assistant parish priest who pushed Johann Huber so aggressively (and refused to apologize for his attacks) that the latter turned his back on Catholicism forever. Transferred to the cathedral in Linz in 1901, Schöfecker served there in numerous assignments with distinction and died in 1955.

Principal Karl Binna of the Rottenbach Elementary School made his debut in this story as a supporter and ally of Pastor Schachinger and the locally dominant Catholic Church. To his credit, Binna withdrew from the fray when he understood the Austrian laws regarding church and school religious services. He died in 1929.

Schoolmaster Karl Binna as he appeared in 1918.

Schoolmaster Karl Binna as he appeared in 1918.

Young Johann Huber, this first son of Michlmayr Huber, born in 1893, probably fought his way home from school on several occasions when his friends sided with the Catholic priest or the school’s principal. As the first youth to join the new church, he was torn between it and the native religion he was not allowed by law to renounce until he was fourteen years of age. As it turned out, he did not officially withdraw from the Catholic Church until October 20, 1937, but was active in the LDS Church all the while.[8] Johann likely assumed direction of the farm when his father was ready to retire (no date is known) and successfully operated the estate until his death in 1977.

Notes

[1] Wilhelm Hirschmann, interviewed by Roger P. Minert. October 3, 2014. See appendix B.

[2] Emperor Josef II was the brother of Franz Josef’s great-grandfather Leopold II.

[3] Editors of Der Stern, Die Ewige Wahrheit (Hamburg: Schröder und Jene, 1898), Church History Library, Salt Lake City; and Hugh J. Cannon and Levi Edgar Young, Der Abfall vom Ursprünglichen Evangelium und dessen Wiederherstellung (Zürich: LDS German Mission, 1901), L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

[4] Johann Huber to Karl Schöfecker, July 28, 1901, Wilhelm Hirschmann private collection, Aggsbach Maskt, Austria.

[5] Gerlinde Huber Wambacher reported having no old books that belonged to Johann Huber.

[6] Heinrich M. Teply, Das Licht Scheint in der Finsternis, 1994, 47, L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

[7] Wilhelm Hirschmann, interviewed by Roger P. Minert, October 3, 2014.

[8] Franz Schoberleitner to Roger P. Minert, September 16, 2014.