From Obscurity to Scripture: Joseph F. Smith's Vision of the Redemption of the Dead

Mary Jane Woodger

Mary Jane Woodger, “From Obscurity to Scripture: Joseph F. Smith's Vision of the Redemption of the Dead,” in You Shall Have My Word: Exploring the Text of the Doctrine and Covenants, ed. Scott C. Esplin, Richard O. Cowan, and Rachel Cope (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 234–54.

Mary Jane Woodger was a professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this article was published.

I was one of those who casually participated in one of the most significant acts of common consent of my generation. I excuse my lack of understanding because I was young when in the April 1976 general conference I sustained and approved the actions of the First Presidency and Council of the Twelve in adding two new sections to the Pearl of Great Price, formally enlarging the official body of the standard works of the Church. [1] Though Elder Boyd K. Packer of the Quorum of the Twelve called that time a day of “great events relating to the scriptures,” [2] my reaction to the addition of scripture was nonchalant. I was not alone in that response. Indeed, Elder Packer felt that most Church members had the same reaction. He said: “I was surprised, and I think all of the Brethren were surprised, at how casually that announcement of two additions to the standard works was received by the Church. But we will live to sense the significance of it; we will tell our grandchildren and our great-grandchildren, and we will record in our diaries, that we were on the earth and remember when that took place.” [3] This paper will seek to attach the proper significance to the inclusion of Joseph F. Smith’s vision of the redemption of the dead in the standard works.

Today, more is known about how this scriptural passage came to be than what is known about probably any other section found in the Doctrine and Covenants. Most members are aware of the circumstances surrounding President Joseph F. Smith when he received this revelation. During his final illness in October 1918, President Smith was stricken by age and was undoubtedly pondering the recent death of his son and other family members. With his own looming death, which took place a few weeks after, he may have been “[wondering] about the nature of the ministry that would be his in the spirit world.” [4]

There has been some research about the global and personal context surrounding Joseph F. Smith’s vision. [5] Latter-day Saint scholars Thomas G. Alexander, Richard E. Bennett, and George S. Tate have described the context in which the revelation was received, citing the influence of the Great War, the 1918 influenza pandemic, and President Joseph F. Smith’s personal experiences with death as events that brought him to ponder the significant passages of 2 Peter. This paper, however, will examine the process by which this vision was eventually canonized as part of the standard works. While the vision affirms the great love of God, the timing of the vision’s canonization also clarifies and reiterates God’s great love for his children, especially his love for his valiant and obedient children who, as members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, shoulder the responsibility of performing ordinances for the dead.

The text of Joseph F. Smith’s vision of the redemption of the dead sets forth with remarkable clarity the manner in which the Savior before his resurrection declared liberty to the captives in spirit prison. This revelation revises the Bible: Christ himself did not go personally to the spirits in prison; rather, he organized others to teach. It also discloses the pattern by which the doctrines of the gospel are shared with those who have died without that knowledge. The vision itself answered many questions that had perplexed not only Latter-day Saint communities but the entire Christian world. Joseph F. Smith’s vision of the redemption of the dead answers many difficult theological questions, such as, what becomes of those who die without the opportunity to accept Christ while they lived? Of particular interest to Saints is the message of how the gospel is taught to the dead in the spirit world. Many religious scholars have made serious efforts at analyzing and expanding on the vision’s text, which answers those questions. [6]

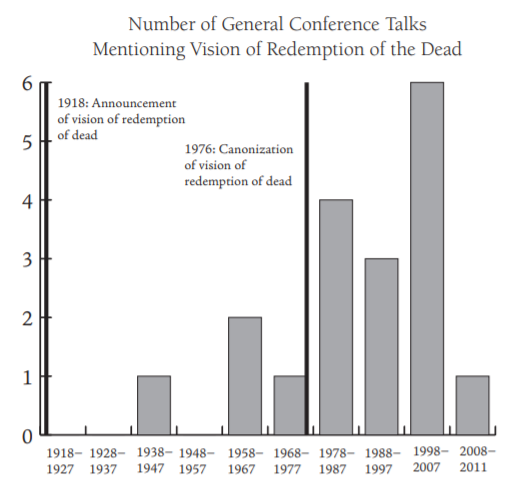

The vision of the redemption of the dead went through an incubation period until it was formally added to the Pearl of Great Price, and later to the Doctrine and Covenants. Church members had to mature in doctrines involving temple work before they could comprehend the responsibility to their kindred dead implicated in Joseph F. Smith’s vision. Later, General Authorities began referring to the doctrine in the vision in general conference addresses. The revelation was then taught, accepted, and ultimately applied by Church membership. When technological advancements made genealogical research practical, the Saints could more fully live by the teachings in President Smith’s revelation, and it was canonized as part of the standard works.

The research provided in this paper is “a thorough study of the historical process that brought this doctrinal statement out of obscurity and into the realm of modern Mormon scripture.” [7] This study centers on the use of this vision by General Authorities in general conference, exploring who quoted the text, the context of use, and the interpretation of the doctrinal insights shared.

Section 138 of the Doctrine and Covenants now serves as one of the foundational documents for the current practices and doctrines of the vicarious temple ordinances for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. With this in mind, it is important to understand the process that took place from the announcement of the vision in 1918 to its canonization in 1976 and the use of the canonized version by General Authorities thereafter. This paper will explore the factors that led to the vision’s canonization and will hypothesize why 1976 became the watershed year for the vision to become scripture. Making this revelation scripture before this time would have caused unnecessary hardship for the Saints, who lacked the technology and ability to accomplish the necessary family history work.

Announcement

Joseph F. Smith never described his vision in general conference. In October 1918, most Saints did not expect to see their prophet take the stand at general conference, since the prophet “[had] been undergoing a siege of very serious illness for the last five months.” [8] At the time, Joseph F. Smith was too ill to speak very long. However, it appears President Smith had every intention of sharing his vision at a future time when he was more capable of standing before a congregation. He said, “I shall postpone until some future time, the Lord being willing, my attempt to tell you some of the things that are in my mind, and that dwell in my heart. I have not lived alone these five months. I have dwelt in the spirit of prayer, of supplication, of faith and of determination; and I have had my communication with the Spirit of the Lord continuously.” [9] President Smith’s entire address may have lasted a total of five minutes, and the above statement was all that he said regarding the future new scripture. According to his son Joseph Fielding Smith, the prophet expressed “the fact that during the past half-year he had been the recipient of numerous manifestations, some of which he had shared with his son, both before and following the conference.” [10] At the close of the October 1918 conference, the prophet then dictated the vision of the redemption of the dead to Joseph Fielding Smith. [11]

Acknowledgment

On October 31, 1918, the dictated manuscript was presented to the First Presidency, the Quorum of the Twelve, and the Church Patriarch in a council meeting. At the time, the prophet was too ill to attend, so he asked his son Joseph Fielding Smith to read the revelation to the gathering. President Anthon H. Lund recorded in his journal, “In our Council Joseph F. Smith, Jr. read a revelation which his father had had in which he saw the spirits in Paradise and he also saw that Jesus organized a number of brethren to go and preach to the spirits in prison, but did not go himself. It was an interesting document and the apostles accepted it as true and from God.” [12] Elder James E. Talmage also wrote about the event in his journal:

Attended meeting of the First Presidency and the Twelve. Today President Smith who is still confined to his home by illness, sent to the Brethren the account of a vision through which, as he states, were revealed to him important facts relating to the work of the disembodied Savior in the realm of departed spirits, and of the missionary work in progress on the other side of the veil. By united action the Council of the Twelve, with the Counselors in the First Presidency, and the Presiding Patriarch accepted and endorsed the revelation as the word of the Lord. President Smith’s signed statement will be published in the next issue (December) of the Improvement Era, which is the organ of the Priesthood quorums of the church. [13]

The text of the vision then appeared in the November 30 edition of the Deseret Evening News. It was also printed “in the December Improvement Era, and in the January 1919 editions of the Relief Society Magazine, the Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine, the Young Woman’s Journal, and the Millennial Star.” [14] General Authorities seemed anxious for the Saints to have access to the text of the vision in a timely manner.

President Smith’s physical condition worsened, and on November 19, 1918, he died of pleuropneumonia. In his funeral address for President Joseph F. Smith, Elder Talmage mentioned the vision. He reminded the audience: “[President Smith] was permitted shortly before his passing to have a glimpse into the hereafter, and to learn where he would soon be at work. He was a preacher of righteousness on earth, he is a preacher of righteousness today. He was a missionary from his boyhood up, and he is a missionary today amongst those who have not yet heard the gospel, though they have passed from mortality into the spirit world. I cannot conceive of him as otherwise than busily engaged in the work of the Master.” [15]

Obscurity

Considering the prominence of the vision during the last weeks of Joseph F. Smith’s life and at his funeral, one has to wonder how it drifted into obscurity over the next twenty-seven years. There is no documentation of the vision being discussed by any Church leader in general conference until 1945. One has to wonder why the contemporaries of Joseph F. Smith, those closest to him, those who had sat in a council room and declared the revelation to be the word of God, did not speak of it in general conference. There must have been a reason for this neglect. Even the prophet’s own son Joseph Fielding Smith did not, as a General Authority, use the vision in his sermons, though he included it in his father’s biography (published in 1938) and also in the volume Gospel Doctrine. [16] Likewise, Elder Talmage did not discuss the vision in front of the Church congregations at general conference, despite speaking on the importance of genealogical work. It is interesting to note that a few weeks before Joseph F. Smith’s announcement that he had had a vision, Elder Talmage had given a talk in the Tabernacle, where he said:

The purpose . . . is that of promoting among the members of the Church a vital, active interest in the compilation of genealogical records, in the collating of items of lineage and in the formulation of true family pedigrees, so that the relationship between ancestry and posterity may be determined and be made readily accessible. . . .

It is a notable fact that the last seven or eight decades have witnessed a development of interest in genealogical matters theretofore unknown in modern times. . . . There is . . . an influence operative in the world, a spirit moving upon the people, in response to which the living are yearningly reaching backward to learn of their dead. [17]

And yet, after the prophet received a revelation just a few weeks later which detailed the activity of the spirit world, James E. Talmage never mentioned the vision in general conference.

After Joseph F. Smith’s death, his contemporaries simply did not refer back to the vision of the redemption of the dead. During Heber J. Grant’s administration, other pressing issues such as Prohibition, the Great Depression, and World War II dominated the teachings of the General Authorities. However, although World War II would take millions of lives, General Authorities said nothing about the revelation which so clearly outlined what would happen in the spirit world to the victims of the war.

Mentioning

It was not until April 1945 that Elder Joseph L. Wirthlin was the first to mention in general conference President Joseph F. Smith’s vision of the redemption of the dead. Elder Wirthlin used the revelation to counter the teachings of Cardinal Gibbons, a leading ecclesiastical leader of the day. Cardinal Gibbons taught “that the ordinance of baptism was changed from that of immersion to sprinkling for convenience’s sake.” Elder Wirthlin used President Smith’s vision to refute the premise of “convenience’s sake” and emphasized the validity of modern prophetic revelation over human deduction. He also answered the question of what would happen to those not born of the water and the spirit. Elder Wirthlin emphasized that the vision of the redemption of the dead showed the great kindness of a Father in Heaven who instituted a plan “whereby all his children, be they alive or dead, might have the privilege of accepting or rejecting the gospel of his beloved Son.” [18] This emphasis on God’s kindness was the first time the vision of the redemption of the dead had been used as a metaphor in general conference.

It would be another nineteen years before President Smith’s vision of the redemption of the dead would again be mentioned during general conference. In April 1964, Elder Marion G. Romney simply stated: “Another medium of revelation is visions. You know about Nephi’s vision, the Prophet’s great vision recorded in the 76th section of the Doctrine and Covenants, and President Joseph F. Smith’s vision of work for the dead in the spirit world.” It is interesting that Elder Romney said to the congregation, when referring to the vision, “you know about it” even though the vision had not been spoken of in general conference for nearly two decades. [19]

Two years later, in 1966, Elder Spencer W. Kimball spoke of continuing revelation, and merely said, “The visions of Wilford Woodruff and Joseph F. Smith would certainly be on a par with the visions of Peter and Paul.” [20] Elder Kimball then declared that the vision of the redemption of the dead a “most comprehensive” example of the revelation available to Latter-day Saints. [21] In the three addresses listed above, the vision is mentioned but the text of the revelation itself is not quoted. At this time, General Authorities made no attempt to connect the vision’s doctrine to the lives of the Saints.

Canonization

In October 1975, just six months before the vision’s canonization, Elder Boyd K. Packer made an interesting introduction to his general conference address: “I have reason, my brothers and sisters, to feel very deeply about the subject that I have chosen for today, and to feel more than the usual need for your sustaining prayers, because of its very sacred nature.” [22] One of the subjects Elder Packer felt strongly about was the vision of the redemption of the dead. For the first time in a general conference, a General Authority quoted directly from the vision. It had been fifty-seven years since the vision had been acknowledged to be the word of God; this was the first time words from the text were shared in conference.

This was also to be the first time that the vision would make the pivotal link to genealogical research. After quoting two verses from the future scripture, Elder Packer stated, “Here and now then, we move to accomplish the work to which we are assigned. . . . We gather the records of our kindred dead, indeed, the records of the entire human family; and in sacred temples in baptismal fonts designed as those were anciently, we perform these sacred ordinances.” Elder Packer may have sensed that the vision would soon become scripture for the Church. He taught that only through temple ordinances can spirits be released from bondage, which ordinances can only be realized after conducting genealogical research. [23]

Joseph Fielding McConkie believes that his father, Elder Bruce R. McConkie of the Quorum of the Twelve, was instrumental in introducing the subject of the vision’s canonization to the First Presidency. Joseph says that his father drew heavily upon the vision while writing his six-volume series on the Messiah: “Because of his position on the Scriptures Publication Committee and his love of the revelations of the Restoration, Elder McConkie was in a position to recommend that Joseph Smith’s vision of the celestial kingdom and Joseph F. Smith’s vision of the redemption of the dead be added to the canon of scripture.” At the time, Elder McConkie also desired to add other historical manuscripts to the canon, including the Wentworth letter, the Lectures on Faith, the Doctrinal Exposition of the First Presidency on the Father and the Son issued in 1916, the King Follett Discourse, and a similar discourse given by the Prophet Joseph Smith in the Grove at Nauvoo in June of 1844. The fact that the vision of the redemption of the dead and Joseph Smith’s vision of the celestial kingdom were canonized while the other manuscripts were not reveals the documents’ importance as Latter-day Saint doctrine. [24]

Additionally, President Kimball’s son Edward L. Kimball discloses that his father had “long wished for official recognition of two revelations dealing with the state of the dead” because of the significance they would accord genealogy work. [25] There is no doubt that President Kimball, in his sacred calling as prophet, felt a spirit of urgency to include these two visions in the standard works.

Non-Church stimuli at the time also incited Churchwide interest in the concept of life after death. With the publication of Alex Haley’s book Roots in 1975 and its dramatization as a television miniseries in January 1977, interest in family history increased nationally. A “genealogy mania” was sweeping the nation, and the Church certainly had enhanced the reason that this surge of genealogy was taking place. [26] Bicentennial celebrations in 1976, which fostered national pride and presentations of local history, may have also contributed to the Saints’ enthusiasm to accept the vision as scripture. [27]

At the April 1976 general conference, President N. Eldon Tanner, First Counselor in the First Presidency, stood at the pulpit and concluded the sustaining of the General Authorities and general officers of the Church by stating:

At a meeting of the Council of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve held in the Salt Lake Temple on March 25, 1976, approval was given to add to the Pearl of Great Price the following two revelations:

First, a vision of the celestial kingdom given to Joseph Smith, the Prophet, in the Kirtland Temple, on January 21, 1836, which deals with the salvation of those who die without a knowledge of the gospel.

And second, a vision given to President Joseph F. Smith in Salt Lake City, Utah, on October 3, 1918, showing the visit of the Lord Jesus Christ in the spirit world and setting forth the doctrine of the redemption of the dead.

It is proposed that we sustain and approve this action and adopt these revelations as part of the standard works of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. [28]

The congregation voted affirmatively, and the two visions were immediately added to the Pearl of Great Price. With that addition, the Pearl of Great Price received its first new scriptures since its own acceptance as a standard work in 1880. Five years later, these visions were transferred to the new 1981 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants as sections 137 and 138. Church administration followed the pattern of canonization of Doctrine and Covenants 87, which had also been a part of the Pearl of Great Price before it was moved to the Doctrine and Covenants. No changes were made in the text of section 138 as it moved from the Pearl of Great Price to the Doctrine and Covenants. Both sections 137 and 138 shed light on the salvation of the dead, so their addition to the scriptural canon was timely, arriving in “an era of unprecedented temple-building activity.” [29] Elder McConkie noted the timeliness of the canonization of section 138 with regards to temple work for the dead. In the August 1976 Ensign, he related:

It is significant that the two revelations which the Brethren chose at this time to add to the canon of scripture both deal with that great and wondrous concept known and understood only by the Latter-day Saints: the doctrine of salvation for the dead. With the recent dedication of new temples in Ogden, Provo, and Washington, D.C.; with the complete remodeling of the Mesa, St. George, and Hawaii Temples; and with the building of new temples in Japan, Brazil, Mexico, and Seattle, this basic Christian doctrine, which shows the love of a gracious Father for all his children, is receiving an emphasis never before known. [30]

As the vision became scripture, most Saints little understood that it would promote temple and genealogy work as never before. It appears that the revelation had not been canonized before because in 1976, hardly any genealogical technology existed, making the process impractical and tedious. After the revelation was accepted by the congregation, its doctrine became binding. The Saints had made a covenant to fulfill their obligation to save their dead as outlined in the vision of the redemption of the dead. General Authorities began to use section 138 on a more regular basis to better teach the Saints about this sacred responsibility.

Teaching the Vision

In the April 1981 general conference, Elder Royden G. Derrick of the First Quorum of the Seventy extensively reviewed what Joseph F. Smith saw in the spirit world in order to emphasize the urgency of temple work for the dead. He quoted verses 11–12, 14, 18, 20, 30–32, and 57–59. Never before had a General Authority quoted so comprehensively from the vision. At the end of his talk, Elder Derrick very clearly outlined how the scripture had become binding on the Saints, associating the scripture with the responsibilities of finding names, building temples, and performing ordinances. He said, “One of the major missions of the Church is to uniquely identify these individuals who have died and perform the necessary saving ordinances in their behalf, for they cannot do it for themselves. Once these ordinances are performed, if the individual accepts the gospel in the great world of spirits, then this work will be effective.” [31] For the first time, a General Authority in general conference stressed the necessity of doing individual family history research to produce the needed data for temple work.

Other Apostles have since taught of this responsibility of the living, but they have also suggested that joy would come to the dead who benefit from vicarious saving ordinances. In October 1992, President Thomas S. Monson of the First Presidency quoted Joseph F. Smith as he instructed, “Through our efforts in their behalf [the dead] their chains of bondage will fall from them, and the darkness surrounding them will clear away, that light may shine upon them and they shall hear in the spirit world of the work that has been done for them by their children here, and will rejoice with you in your performance of these duties.” [32] Likewise, Robert D. Hales of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles restated the joy the dead felt because their deliverance was at hand, intimating that the Saints would also feel joy in completing ordinances for the dead. [33]

In April 1993, President Ezra Taft Benson noted the timeliness of the vision of the redemption of the dead and its significance to living Latter-day Saints. He explained, “There has been considerable publicity and media coverage recently on the reporting of experiences that seemingly verify that ‘life after life’ is a reality.” [34] In his address, President Benson used Joseph F. Smith’s vision as the absolute declaration of the reality of life after life, reminding Church members that the vision of the redemption of the dead had been accepted as holy scripture and therefore truth from heaven.

In the October 2005 general conference, Elder Paul E. Koelliker of the First Quorum of the Seventy connected the vision with temple work, stating, “There is still available time in many temples to accommodate the counsel of the First Presidency to put aside some of our leisure time and devote more time to performing temple ordinances. I pray that we will be responsive to this invitation to come to the door of the temple.” [35] He used the doctrine in President Smith’s vision to emphasize to members the importance of temple work, especially above leisure activities.

General Authorities also used the vision of the redemption of the dead to show a pattern for personal revelation. Elder Joseph B. Wirthlin of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, in May 1982, and President Henry B. Eyring of the First Presidency, in October 2010, used the vision as a pattern for receiving revelation. They encouraged Church members to take the same approach that President Joseph F. Smith had taken to seek personal revelation. Before introducing the vision, Elder Wirthlin began his address by saying, “It is about pondering and what can be gained therefrom that I should like to address my remarks today.” [36] Likewise, President Henry B. Eyring used the vision as instruction for personal revelation: “For me, President Joseph F. Smith set an example of how pondering can invite light from God.” [37] These General Authorities used the vision to illustrate a pattern of pondering and revelation that all Saints can follow.

General Authorities also used the vision to show how God values women. In his vision, Joseph F. Smith saw Eve and her daughters involved in missionary work in the spirit world. In October 1993, Elder Dallin H. Oaks of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles emphasized Eve and her role in the plan of salvation. [38] In October 1999, President James E. Faust validated Latter-day Saint women in their “lasting legacy” of blessing the lives of “all men and women,” both living and dead. [39] Joseph F. Smith’s vision served to show how women too preach the gospel and bring lost souls to a knowledge of their God.

Fulfilling the Scripture

The great mercy of the Lord can be seen in the timing of making the vision of the redemption of the dead a binding covenant. The Lord appears to have waited until the means would be available to realize the work of saving the dead. Through his servant Joseph F. Smith, the Lord seemed to take preliminary steps in preparing the Saints for the inclusion of the vision of the redemption of the dead in the standard works. For instance, while dedicating the Washington DC Temple in November 1974, President Spencer W. Kimball prophesied that “the day is coming, not too far ahead of us, when all the temples on this earth will be going night and day.” [40] In his October 1975 conference address, Elder Packer stated that President Kimball’s prophecy represented “our signal that the great work necessary to sustain the temples must be moved forward.” He assessed, “Genealogical work has, I fear, sometimes been made to appear too difficult, too involved, and too time-consuming to really be inviting to the average high priest.” [41]

In the past, genealogy work had been slow, monotonous, and difficult. “Latter-day Saints had been encouraged for decades to research their kindred dead and provide completed family group sheets, which were verified by the Temple Index Bureau before the vicarious temple ordinances could be performed. This was a slow and tedious hand-checking process, and often information provided was incorrect and the sheets had to be rejected.” [42] An “acute shortage of names” had also plagued the Genealogical Society’s “efforts to keep the temples supplied.” [43] Although the Saints were encouraged to do their own genealogy and not be dependent on temple files for names, the names at the temples available for temple work were often insufficient for those wanting to serve. As Church membership increased, “the situation was critical, and solutions had to be found as quickly as possible.” [44]

Elder Packer and the other members of the Temple and Genealogy Executive Committee prayed and studied to understand “why the work was not going forward. . . . In these efforts Elder Packer worked closely with Elder Bruce R. McConkie in exploring and discussing the scriptural basis for the sure direction in which the committee was moving.” [45] The canonization of the vision of the redemption of the dead would play a large part in moving the work for the dead forward.

By assignment from the First Presidency, Elder Packer addressed the employees of the Genealogical Society on November 18, 1975, and pleaded for their cooperation: “Now I’m appealing to you all to set your minds to the task of simplifying basic genealogical research and of streamlining, in every way possible, the process by which names come from members of the Church and are ultimately presented in the temple for ordinance work.” [46]

On December 10, 1975, the Genealogical Society became the Genealogical Department of the Church. This action fully integrated the department as part of the Church’s central administration for the first time. [47] In addition, during the first part of 1976, all General Authorities visiting stake conferences were to instruct Church members “to prepare a life history and to make a record of events which had transpired in their lives.” [48] In this way the First Presidency encouraged personal participation in genealogical work, paving the way for even more hands-on participation in the process.

With the preliminary measures paving the way, the announcement that the two revelations were to become scripture was significant in moving the work ahead. Immediately after the vision of the redemption of the dead was canonized, genealogical work was simplified in major strides. In 1976, the year the vision became scripture, the Genealogical Department adopted long-range goals to simplify the process for the first time. [49] Before, long-range planning had been informal. The plan presented to and cleared by the First Presidency included the “creation of multiple automated data files” and “the widespread distribution of genealogical information through personal computers.” [50] The First Presidency envisioned that these goals would return the responsibility of finding names to the Church members, with whom the responsibility had resided until 1927. Elder J. Richard Clarke said this decision would “revolutionize family history work.” He hoped to “make family history work easy for anyone who would try”; this would “propel the Church into a new era of family history activity.” [51]

Lucille Tate, Elder Packer’s biographer, shows how the Genealogical Department took measures to make family history work easier after the vision became scripture:

By April 1 that year [1977], they had gained approval from the First Presidency for long-range goals that would move “a church and a people” nearer to what the Lord expected of them in redeeming their dead. The Genealogical Department was tooling up to enter the age of computers, and in order to become conversant with them Elder Packer attended a one-week crash course at IBM in San Jose, California.

By assignment from the committee, Elder Packer in a talk titled “That They May Be Redeemed,” said: “Billions have lived and we are to redeem all of them. . . . Overwhelming? Not quite! For we are the sons and daughters of God. He has told us that He would give ‘no commandments unto the children of men, save he shall prepare a way for them that they may accomplish the thing which he commandeth them’” (1 Nephi 3:7). [52]

Up to the canonization of President Smith’s vision, the majority of Church members did not have a way to perform vicarious temple work. However, in 1977, Elder Packer summed up the process as follows: “It is as though someone knew we would be traveling that way . . . and we find provision, information, inventions . . . set along the way waiting for us to take them up, and we see the invisible hand of the Almighty providing for us.” [53]

In general conference two years after the canonization, President Spencer W. Kimball asserted, “I feel the same sense of urgency about temple work for the dead as I do about the missionary work for the living, since they are basically one and the same. . . . We are introducing a Churchwide program of extracting names from genealogical records.” [54] In an interview with the Ensign, George H. Fudge of the Genealogical Department clearly stated that “new technology had been made available to mankind which can help us accomplish the Lord’s purposes at a much faster pace and with much greater accuracy than ever before.” [55] Fudge continued:

December 1978 marks the end of the current four-generation program for individuals and the beginning of the four-generation program for families. . . .

Now we come to a very significant idea associated with this thrust: as has been announced, original research beyond the four-generation level will be accepted but will no longer be required of individual members of the Church. Instead, the Church feels the responsibility to begin a massive records gathering and extraction program in order to prepare names for temple work. . . . By using computers, temples will be able to record their own information. And rather than sending tons of paper back to Salt Lake City, they will send a concise computerized record of all their work. Consequently, our indexes will be easier to compile. [56]

The computer would become the indispensable tool in genealogical research, allowing Church members to fulfill the responsibility that General Authorities had linked to section 138.

The Genealogical Department aimed to streamline and simplify. As a result, the material necessary to do genealogical research became available more easily and in greater quantity than ever before. Branch libraries were computerized in 1975. By March 1976, genealogical films circulated numbered 22,127, “a 45 percent increase from March 1975.” [57] The Family History Library in Salt Lake City was “flooded with an average of 3,500 visitors daily during the summer of 1977, up from a high of 2,000 per day in the previous year.” [58] In 1977, the stake record extraction program was introduced, and the program was declared “phenomenally successful.” [59] In 1981, just five years after Joseph F. Smith’s vision was canonized, the International Genealogical Index (IGI) was published. According to Eleanor Knowles, “Members could submit single-entry forms with individual names, without having to wait until the individual could be linked to a family.” [60] The IGI grew substantially with each edition, expanding by 34 million names in 1975, 81 million in 1981, 108 million in 1984, 147 million in 1988, and 187 million in 1992. The number of names increased by an average of 9 million names each year. [61] The Church News referred to the widespread interest as an “international genealogy mania.” [62]

Conclusion

The vision of the redemption of the dead has become central to the theology of the Latter-day Saints. It confirms and expands earlier prophetic insights concerning work for the dead and introduces doctrinal truths that were unknown before October 1918 and not fully instituted until 1976. [63] As religious scholar Trever R. Anderson describes, “Latter-day Saints view the words of the Prophet and Apostles as the words of God, yet canonized scripture still stands on a higher plane. Canonization of a revelation or vision validates its authority, prominence, and doctrinal power.” By being canonized, this 1918 vision “was elevated from obscure Church history to central core doctrine.” [64]

Since canonization, Doctrine and Covenants 138 has been linked by General Authorities to temple, genealogical, and family history work. Section 138 is now a major part of Church doctrine and has become the basis of Church teachings about salvation of the dead.

The process by which Joseph F. Smith’s vision of the redemption of the dead became part of the Doctrine and Covenants serves as an example of how revelation becomes canonized. Not until Church members were capable of fulfilling their responsibility to the dead did the revelation become binding as a scriptural command. Over time, Church leaders have gradually taught about the significance of section 138, and Latter-day Saints have accordingly lived by this doctrine in stages. Practices such as building temples and performing saving ordinances for the living and the dead demonstrate that the doctrines associated with the vision were first considered authoritative by the leadership of the Church in 1918 but are now binding to all the members of the Church.

The remarkable process of bringing this vision to scripture is worthy of sharing with our grandchildren and great-grandchildren now that the work of salvation for the dead is achievable. This doctrinal foundation will yet provide the way in which, as Elder Boyd K. Packer has expressed, “we can redeem our dead by the thousands and tens of thousands and millions and billions and tens of billions. We have not yet moved to the edge of the light.” [65]

Appendix A

1976 Long-Range Goals

|

No. |

Summary of Goal |

Current Implementation |

|

1 |

Develop and maintain a central genealogical file that shows family relationships and temple ordinance data for individuals |

FamilySearch, Ancestral File |

|

2 |

Design all name entry systems to place individuals in their proper family order |

Ancestral File |

|

3 |

Prepare a single index to all temple work for a given individual |

International Genealogical Index |

|

4 |

Make information in the central genealogical file available to Church members as a beginning point for their own genealogical research |

FamilySearch |

|

5 |

Establish genealogical service centers in temple districts, particularly overseas, and involve members in a records extraction program |

Family History Service Centers, Family Record Extraction |

|

6 |

Use modern technology in temple recording and enable service centers to process names locally |

Ordinance Recording System, TempleReady |

|

7 |

Transfer to families and local priesthood leaders the burden of determining the accuracy of name submission and responsibility for avoiding duplication of temple ordinances |

TempleReady |

|

8 |

Develop and maintain a family organization register to aid members in contacting other persons researching their same lines |

Family Registry, Ancestral File |

|

9 |

Provide a service to assist priesthood leaders in more difficult areas of genealogical research |

Published research outlines |

|

10 |

Continue the present program of gathering records of genealogical interest from around the world |

Expansion of microfilm acquisitions |

Adapted from James B. Allen, Jessie L. Embry, and Kahlile B. Mehr, Hearts Turned to the Fathers (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 1995), 271.

Notes

[1] N. Eldon Tanner, “The Sustaining of Church Officers,” Ensign, May 1976, 19.

[2] Boyd K. Packer, “Teach the Scriptures” (address to CES religious educators, October 14, 1977), 4.

[3] Packer, “Teach the Scriptures,” 4.

[4] Craig J. Ostler and Joseph Fielding McConkie, Revelations of the Restoration (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 1143.

[5] See Richard E. Bennett, “‘And I Saw the Hosts of the Dead, Both Small and Great’: Joseph F. Smith, World War I, and His Visions of the Dead,” in By Study and by Faith: Selections from the Religious Educator, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 113–35; George S. Tate, “‘The Great World of the Spirits of the Dead’: Death, the Great War, and the 1918 Influenza Pandemic as Context for Doctrine and Covenants 138,” BYU Studies 46, no. 1 (2007): 5–40; and Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition: A History of the Latter-day Saints, 1890–1930 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 282, 299.

[6] See H. Dean Garrett and Stephen E. Robinson, A Commentary on Doctrine and Covenants, vol. 4 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2001); Lyndon W. Cook, Revelations of the Prophet Joseph Smith: A Historical and Biographical Commentary of the Doctrine and Covenants (Salt Lake City: 1981); Ostler and McConkie, Revelations of the Restoration; and Donald W. Parry and Jay A. Parry, Understanding Death and the Resurrection (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003).

[7] Bennett, “‘And I Saw the Hosts of the Dead,’” 113.

[8] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, October 1918, 2.

[9] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, October 1918, 2.

[10] Cited in Robert L. Millet, “Salvation beyond the Grave (D&C 137 and 138),” in Studies in Scripture, vol. 1, The Doctrine and Covenants, ed. Robert L. Millet and Kent P. Jackson (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1989), 554.

[11] See Joseph Fielding Smith, Life of Joseph F. Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1938), 466.

[12] Anthon H. Lund, journal, October 31, 1918, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

[13] James E. Talmage, diary, October 31, 1918, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, box 5, folder 6, p. 62.

[14] Millet, “Salvation Beyond the Grave,” 561.

[15] James E. Talmage, in Conference Report, April 1919, 60.

[16] Gospel Doctrine: Selections from the Sermons and Writings of Joseph F. Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1946), 472–75; and Smith, Life of Joseph F. Smith, 466–69.

[17] James E. Talmage, “Genealogical Work Is Essential to Redemption of the Dead in the Holy Temples of the Lord” (address delivered in the Tabernacle, Salt Lake City, September 22, 1918).

[18] Joseph L. Wirthlin, in Conference Report, April 1945, 69, 71.

[19] Marion G. Romney, in Conference Report, April 1964, 124.

[20] Spencer W. Kimball, in Conference Report, October 1966, 23.

[21] Spencer W. Kimball, in Conference Report, October 1966, 26.

[22] Boyd K. Packer, “The Redemption of the Dead,” Ensign, November 1975, 97.

[23] Packer, “Redemption of the Dead,” 99.

[24] Joseph Fielding McConkie, The Bruce R. McConkie Story: Reflections of a Son (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003), 383, 389, 391.

[25] Edward L. Kimball, Lengthen Your Stride: The Presidency of Spencer W. Kimball (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2005), 377.

[26] Kimball, Lengthen Your Stride, 377.

[27] Kip Sperry, “From Kirtland to Computers: the Growth of Family History Record Keeping,” in The Heavens Are Open: 1992 Sperry Symposium on the Doctrine and Covenants and Church History, ed. Byron R. Merrill (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1993), 294.

[28] Tanner, “Sustaining of Church Officers,” 19.

[29] Richard O. Cowan, The Doctrine and Covenants: Our Modern Scripture (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1984), 208.

[30] Bruce R. McConkie, “A New Commandment: Save Thyself and Thy Kindred!,” Ensign, August 1976, 8.

[31] Royden G. Derrick, “Moral Values and Rewards,” Ensign, May 1981, 68.

[32] Quoted in Thomas S. Monson, “The Priesthood in Action,” Ensign, November 1992, 48.

[33] See Robert D. Hales, “Faith through Tribulation Brings Peace and Joy,” Ensign, May 2003, 18; and Robert D. Hales, “Your Sorrow Shall Be Turned to Joy,” Ensign, November 1983, 66.

[34] Ezra Taft Benson, “‘Because I Live, Ye Shall Live Also,’” Ensign, April 1993, 2.

[35] Paul E. Koelliker, “Gospel Covenants Bring Promised Blessings,” Ensign, November 2005, 95.

[36] Joseph B. Wirthlin, “Pondering Strengthens the Spiritual Life,” Ensign, May 1982, 23.

[37] Henry B. Eyring, “Serve with the Spirit,” Ensign, November 2010, 60.

[38] Dallin H. Oaks, “‘The Great Plan of Happiness,’” Ensign, November 1993, 73.

[39] James E. Faust, “What It Means to Be a Daughter of God,” Ensign, November 1999, 101.

[40] Quoted in Lucille C. Tate, Boyd K. Packer: A Watchman on the Tower (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1995), 198.

[41] Quoted in Tate, Boyd K. Packer, 198.

[42] Eleanor Knowles, Howard W. Hunter (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1994), 188.

[43] James B. Allen and others, Hearts Turned to the Fathers: A History of the Genealogical Society of Utah, 1894–1994 (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 1995), 174.

[44] Knowles, Howard W. Hunter, 188.

[45] Tate, Boyd K. Packer, 199.

[46] Quoted in Tate, Boyd K. Packer, 199.

[47] Allen and others, Hearts Turned to the Fathers, 267.

[48] Boyd K. Packer, “Someone Up There Loves You,” Ensign, January 1977, 10.

[49] See appendix A.

[50] Allen and others, Hearts Turned to the Fathers, 271.

[51] Allen and others, Hearts Turned to the Fathers, 308.

[52] Tate, Boyd K. Packer, 201 “That All May Be Redeemed;” compare (Regional Representatives Seminar, Tabernacle, Salt Lake City, April 1, 1977).

[53] Packer, “That All May Be Redeemed,” as cited in Tate, Boyd K. Packer, 202.

[54] Quoted in “New Directions in Work for the Dead,” Ensign, June 1978, 62.

[55] Kimball, “New Directions in Work for the Dead,” 62.

[56] “New Directions in Work for the Dead,” 64, 67.

[57] Allen and others, Hearts Turned to the Fathers, 286.

[58] Allen and others, Hearts Turned to the Fathers, 291.

[59] R. Scott Lloyd, “New Effort to ‘Harvest’ Millions of Names,” Church News, May 27, 1989, 5.

[60] Knowles, Howard W. Hunter, 191.

[61] Allen and others, Hearts Turned to the Fathers, 318.

[62] Quoted in Allen and others, Hearts Turned to the Fathers, 291.

[63] See Robert L. Millet, Life after Death (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1999), 85.

[64] Trever R. Anderson, “Doctrine and Covenants Section 110: From Vision to Canonization” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, August 2010), 154.

[65] Quoted in Tate, Boyd K. Packer, 203.