Larry C. Porter, “The Brigham Young Family: Transition between Reformed Methodism and Mormonism,” in A Witness for the Restoration: Essays in Honor of Robert J. Matthews, ed. Kent P. Jackson and Andrew C. Skinner (Provo: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2007), 249–80.

Larry C. Porter was a professor emeritus of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published.

While living in Whitingham, Windham County, Vermont, 1801–4, members of the John and Abigail (Nabby) Howe Young family were devout adherents of the Methodist Episcopal faith. In 1804 they exchanged the environs of their Green Mountain home for a new opportunity in Sherburne, New York. A decade after the Youngs’ departure, a schismatic group from Whitingham and the adjoining town of Readsborough joined with other likeminded individuals in separating from the Methodist Episcopal Church and forming a Vermont congregation of that seceeding organization know as the Reformed Methodist Church in 1814. Years later a significant number of the John Young family joined the dissenting Reformed Methodist faith after its expansion from New England into the state of New York. However, the Youngs’ quest was not yet ended. They next became discontented with the doctrine of Reformed Methodism and showed their disagreement by breaking with all forms of Methodism, leaguing themselves instead with the early establishment of Mormonism under the Prophet Joseph Smith.

John and Nabby Young had moved their family from Hopkinton, Massachusetts, to the town of Whitingham, Windham County, Vermont, in January 1801. There Brigham Young was born on June 1, 1801. He later said of his father, “My father, John Young, was born March 7, 1763, in Hopkinton, Middlesex County, Massachusetts. He was very circumspect, exemplary and religious, and was, from an early period of his life, a member of the Methodist Church.”[1] Lorenzo Dow Young, another son, added that his father “was at first an Episcopal Methodist, but afterwards, in common with others, became a Reformed Methodist.”[2] John Young’s affiliation with the Reformed Methodists, along with that of other family members, did not occur until the New York years, however. During their brief stay in Whitingham, the Youngs would have been familiar with the Methodist Episcopal elders who preached on the Whitingham circuit, namely Daniel Bromley in 1801, Elijah Ward and Asa Kent in 1802, Phinehas Peck and Caleb Dustin in 1803, and John Tinkham in 1804. The Whitingham circuit was one of the first three formed in the state of Vermont.[3]

The Youngs left Vermont for the town of Sherburne, Chenango County, New York, in 1804,[4] ten years before a branch of the Reformed Methodist Church was organized locally in that state. However, it was from dissenters in the towns of Whitingham and Readsborough (the adjoining township on the west of Whitingham) that the Reformed Methodist movement had its Vermont beginnings in 1814—in the midst of the Youngs’ former neighborhood.[5] The devout Methodist household of John Young may have had at least tacit association with some of the very individuals who later became involved with the reform movement. The Young family’s attendance at the conferences of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Vermont could have provided such an acquaintance. Since they shared a similar background, the Youngs must have had a sympathetic ear to preachers and their principles, as is evident when the Reformed Methodists later made substantial inroads among them and their friends in New York.

Reformed Methodism

Organizational origins of the Reformed Methodist Church can be traced to Reverend Pliny Brett and others. Reverend Brett was engaged as a preacher in the New England conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church when the secession began. Brett had been admitted on trial to the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1805, and in 1808 he was granted full membership. Between 1805 and 1811, he served churches in the Maine and New London districts. Reverend Brett was in the Boston district in 1812 and moved there in 1813.[6] Soon after Brett’s relocation, Nathan Bangs, an early historian for Methodism, reported that Brett “put himself at the head of a party under the denomination of ‘Reformed Methodists.’ He lured from the Church several local preachers and a considerable number of members, almost entirely breaking up some small societies. . . . From thence his influence extended into Vermont, where he was seconded in his endeavors to draw away disciples after him by a local preacher by the name of Baily.”[7]

The “Baily” spoken of by Nathan Bangs was Elijah Bailey of the town of Readsborough, Bennington County, Vermont. Some years before, Daniel Davidson of the Methodist Episcopal Church had precipitated a revival in Readsborough that resulted in the conversions of Elijah Bailey, Jonas Bailey, and Ezra Amadon.[8] These men became zealous local preachers for the Methodist Episcopal faith. However, after several years they were among the instigators of what was called “a feeble secession” from the Methodist Episcopal Church in the towns of Whitingham and Readsborough, Vermont. It was termed “feeble” because only fourteen individuals participated in the initial separation.[9]

Dissatisfied with the Episcopal mode of church government, they “felt straitened in their religious rights and privileges. . . . The gospel precept is: to ‘esteem each other better than ourselves;’ but they feared that this precept of humility, under the practice of the Episcopal mode of church government, had been lost sight of.”[10] Their most salient points of disagreement were published in a “manifesto of grievances,” which declared that if their objections were not removed, they would separate. When their demands were ignored, dissenters held a convention in Readsborough on January 16, 1814, with Elijah Bailey as moderator and Ezra Amadon as clerk. The following resolutions were agreed to by the assembly:

- That it is the opinion of this meeting, that the methodist traveling connection, or preachers in this quarter, have too much fallen from the true spirit of religion.

- That they have left in practice (if not in theory) the true spirit of methodism, and their discipline, which was to raise a holy people.

- To form ourselves into a society, by the name of The Methodist Reformed Church, or Society, and to adhere as far as possible to the practical principles of primitive methodism, but to renounce the episcopal mode of church government.[11]

The Reformed Methodist Church was thus officially formed in the state of Vermont. When they again met February 5–6, 1814, the adherents adopted “Articles for Faith and Practice,” containing ten articles which were to be used as rules for guidance in matters of church government. [12] A local preacher for the Methodist Episcopal Church named William Lake also decided to cast his lot with the dissenters at this gathering and became a primary leader in the movement.[13]

In 1815 the War of 1812 came to a close. That same year, the leadership of the Reformed Methodists in Vermont decided to gather a central core of their membership into a single community of believers. Reverend Wesley Bailey described the rationale behind this common-stock society: “With a view to thrust labourers into the field, a sort of community was formed, Wm. Lake, E[lijah] Bailey, E[benezer] Davis, E[zra] Amadon, and several others being members of it. They bought a farm on the state line in the town of Bennington, Vt., and Hosack [Hoosick], N.Y. This farm consisted of several hundred acres, and the community, of near a dozen farmers.”[14]

The farm was situated on the state line between Vermont and New York and included portions of the towns of Bennington and Shaftsbury in Vermont and Hoosick and Cambridge on the New York side. The agreement to purchase the land was made with John Matthews, the brother of Elizabeth Matthews Lake, wife of William Lake of the Reformed Methodists. During the intricacies of negotiating the sale on November 11, 1815, certain properties were likewise deeded to John Matthews by William Lake and others.[15]

Solomon Chamberlin

Among the new converts attracted to the Reformed Methodists in 1816 was Solomon Chamberlin. Solomon lived in the town of Adams, Berkshire, Massachusetts, just over the state line from the town of Readsborough, Vermont. He had been enrolled with the Episcopal Methodist Church from 1805 to 1816. However, he now “felt uneasy and began to conclude they as a people had apostatized from God.” He began “to pray much to the Lord to shew me his true church and people.” Already the recipient of visions in the night, Solomon experienced yet another dream or vision in which he saw in detail a gathering of “some of God’s dear children.” Within a matter of days he learned of a quarterly meeting which was to be conducted at Readsborough, Vermont, by the Reformed Methodist Church. Solomon had never heard of the denomination before but decided to attend. In doing so, he said that as he descended the mountain into the valley and proceeded to the house of worship to be greeted by the people, he was astonished to discover that the entire setting was exactly the same as in his vision. Solomon was even able to distinguish William Lake as the same “man with a very solemn countenance” who had greeted him beforehand at the house of worship in his vision of the conference. Stirred by this divine witness, he “joined them to live and unite with, so long as they would follow the Lamb of God.”[16]

Completely enthralled by the circumstances of his new affiliation, Solomon sought to align himself with the other members of the community, stating, “In 1816, I moved to Shaftsbury [Vermont] into the combination.” He described the group’s ultimate goal: “At this time the heads of the Church and some families myself with the rest, purchased a farm that cost $25,000, and moved on to it, thinking that the day of the gathering had come; and we came into commonstock, striving to come on to the Apostles ground [see Acts 4:32–35]. We believed in revelation and the healing of the sick through faith and prayer.”[17]

Built by Captain David Matthews about 1783, the State Line House still stands. Members of the Reformed Methodist faith occupied the home at the time Solomon Chamberlin stated, “In 1816, I moved to Shaftsbury [Vermont] into the combination.” Photo from Grace Greylock Niles, The Hoosac Valley: Its Legends and Its History (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1912), 225.

Built by Captain David Matthews about 1783, the State Line House still stands. Members of the Reformed Methodist faith occupied the home at the time Solomon Chamberlin stated, “In 1816, I moved to Shaftsbury [Vermont] into the combination.” Photo from Grace Greylock Niles, The Hoosac Valley: Its Legends and Its History (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1912), 225.

Some of the members of the Reformed Methodist society occupied an imposing three-and-one-half-story brick structure known as the State Line House, built by David Matthews about 1800 and situated right on the state line between Vermont and New York.[18] Unfortunately, the society’s enjoyment of the premises and their beautiful farm was short-lived. Reverend Wesley Bailey, a son of one of the founders, Reverend Elijah Bailey, spelled out his own assessment of the early demise of the order as he observed:

Providence did not seem to smile on the undertaking, though conceived in the purest benevolence. The cold season’s coming on [‘Eighteen Hundred and Froze to Death,’ or ‘The Year Without a Summer,’ the year 1816], the want of funds to pay in advance for the farm, rendered it impossible for them to pay for the place, and after remaining near two years on the premises, they were compelled to scatter; not scattered to abandon their principles, but to promulgate them in other regions, where Providence might open the way.[19]

Disheartened by this turn of events in 1816, Solomon wished to know “whether there were any people on the earth whose principles were right in all things; for I was tired of all orders unless they had the true principles of God.” Exerting himself before God in mighty prayer, the Lord revealed to him an angel “in a vision of the night.” He asked the angel if the Reformed Methodists were right. The heavenly ministrant responded that “not one of us were right, and that there were no people on earth that were right; but that the Lord would in his own due time raise up a church, different from all others, and he would give power and authority as in the days of Christ; and he would carry it through, and it should never be confounded; and that I should live to see the day, and know the work when it came forth.” He was likewise informed “that great persecution should follow.” The angel also instructed Solomon “that there would a book come forth, like unto the Bible, and the people would be guided by it, as well as the Bible.”[20]

Following the disastrous results of “the combination,” or “community,” project, various members of the Reformed Methodist Church were indeed “scattered.” Elijah Bailey was very successful in taking the movement into the Cape Cod region, as well as to Pennsylvania and Ohio. In company with William Lake, Bailey also organized the Reformed Methodist Church in Upper Canada in 1817 and 1818. They were materially assisted in Canada by collaborators Robert and Daniel Perry. James Bailey, brother of Elijah, and Caleb Whiting planted churches for the denomination in central New York. Ezra Amadon took the reform movement into western New York, while Ebenezer Davis continued to expend his efforts in Vermont.[21] The difficulties encountered with the “combination” actually stimulated the work elsewhere, since these evangelists were given cause to spread the Reformed Methodist doctrines even farther afield. Solomon Chamberlin returned to his former home in the town of Adams, Berkshire County, Massachusetts, and by 1819 was again enrolled with the local Methodist Episcopal Church.[22] He appears in the U.S. census for 1820 at Adams, and then his movements become more difficult to trace. However, by February 26, 1828, Solomon had purchased an acre of land on the Erie Canal located just one mile northeast of the village of Lyons, Wayne County, New York.[23] His new home was just fifteen miles east of Palmyra, Wayne County, New York, where the members of the Joseph Smith Sr. family were residing. In the town of Lyons, he appears to have again affiliated with the Reformed Methodists, since there are regular references to his association with the members of that faith.

During the fall of 1829, Solomon was on his way to Upper Canada via the Erie Canal to Lockport, New York. He stopped overnight in Palmyra and, following the promptings of the Spirit and a helpful landlady, made his way to the Smith log house the next day. There he was met by Hyrum Smith, Joseph Smith Sr., Christian Whitmer, and others who were at the household. Solomon shared the contents of his 1829 pamphlet, which had just been published at Lyons. He was then instructed for two days and taken to the E. B. Grandin Bookstore in the village of Palmyra. There he received sixty-four unbound pages of the Book of Mormon to take with him on his journey. When the Church was organized the following year, Solomon Chamberlin was baptized by Joseph Smith in Seneca Lake a “few days after” April 6, 1830.[24] Filled with the spirit of proselytizing for the new faith, Solomon was now in a position to work among his friends and associates in the Reformed Methodist Church in western New York.

The Young Family and Reformed Methodism

During the decades that followed the John Young family’s move from Whitingham, Vermont, to western New York in 1804, the Youngs were drawn into a wide variety of occupations, matrimonial relationships, and geographical locations. If there was a commonality in their several pursuits, it stemmed from their individual desires to find God. The children had been raised in a household of faith and had been taught the importance of religion in life. The majority of them were avidly searching for knowledge of the true gospel of Christ. Initially, their primary avenue of pursuit was Methodism.

Brigham Young said of his own experience: “My parents were devoted to the Methodist religion, and their precepts of morality were sustained by their good examples. I was labored with diligently by the priests to attach myself to some church in my early life. I was taught by my parents to live a strictly moral life, still it was not until my twenty-second year that I became serious and religiously inclined. Soon after this I attached myself to the Methodist Church.”[25]

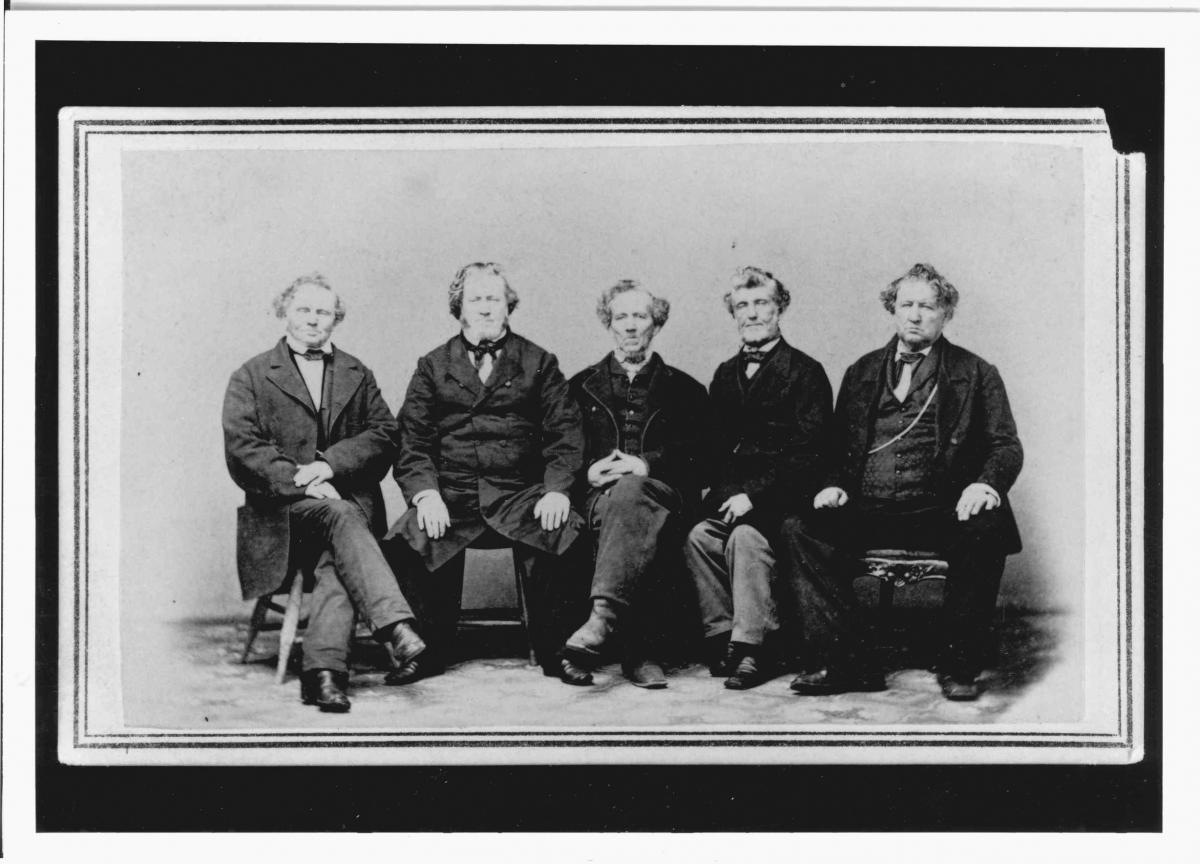

Brigham Young and his brothers, September 13, 1866, photograph by Charles R. Savage. Left to right: Lorenzo Dow Young, Brigham Young, Phinehas Howe Young, Joseph Young, and John Young. Courtesy of Church Archives

Brigham Young and his brothers, September 13, 1866, photograph by Charles R. Savage. Left to right: Lorenzo Dow Young, Brigham Young, Phinehas Howe Young, Joseph Young, and John Young. Courtesy of Church Archives

This connection was made at the time of his marriage to Miriam Angeline Works in the town of Aurelius, Cayuga County, New York, on October 8, 1824. Brigham and Miriam agreed to embrace the Methodist faith in that same year.[26]

Although the pattern of conversion of certain Young family members to the Reformed Methodist Church in New York appears to have begun with Brigham Young’s brother Phinehas Howe Young, the exact sequence is not known. At age nineteen, Phinehas married Clarissa Hamilton at Auburn, Cayuga County, New York, on January 18, 1818. He said, “I now began seriously to think of getting religion, and according to my best light I sought the Lord, but finding very little or no comfort in this I soon gave it up, and concluded to make the best of this world.”[27] However, in the fall of 1823, he again commenced “seeking the Lord with greater energy and a more fixed determination.” Finally, in “April [1824] I gave my name to the Methodist Reformed Church and thus was numbered with that body.” That fall he was baptized by immersion and soon “received license to speak in public.”[28]

As a traveling preacher, Phinehas went to the town of Canandaigua, Ontario County, New York, where he began preaching in the village of Cheshire. He was highly successful in his labors and generated a branch of forty-five members inside of forty-one days. Phinehas then returned home, packed up his family, and moved to Cheshire. He remained there for three years preaching the tenets he had embraced. In the fall of 1826, during a visit to the home of his sister Rhoda Young Greene and brother-inlaw John Portineus Greene in the nearby town of Mendon, New York, Phinehas spoke with John, who had joined the Reformed Methodists in 1825 and had become a preacher also. He also met Heber C. Kimball, who was “living within one hundred steps” of the Greenes. Here Phinehas learned that members of his father’s family were soon moving to Mendon. After concluding his affairs at Cheshire, he too made the move to the town of Mendon in the spring of 1828.[29]

Father John Young had come to Mendon from Tyrone, Steuben County (now Schuyler County), New York, in 1827.[30] He also became a Reformed Methodist, but the circumstances of his conversion are unknown.[31] Similarly, his son Joseph Young, who was then living with his father, was drawn to the Reformed Methodist faith. The date of his baptism into the Reformed Methodist Church is likewise unknown. Brigham Young moved his family to Mendon in the spring of 1829 and located on his father’s farm.[32]

We do not know when Brigham Young chose to align himself with the Reformed Methodist Church. He would have participated in the local Mendon congregation in association with his father and brothers. He was not an active preacher for the Reformed Methodists as were John P. Greene and Phinehas and Joseph Young. Brigham’s apparent passiveness might be attributed to his arduous work schedule in support of his family and invalid wife.

John Young Jr. was an orthodox Methodist. Brigham Young noted, “In the 15th year of his age, he joined the Methodist Church, and was devotedly attached to that religion. . . . In 1825 he received his license as a Methodist preacher, and zealously labored with that body until he heard the gospel as restored in this dispensation.”[33]

Lorenzo Dow Young was not drawn into the Reformed Methodist spectrum either. Brigham Young explained: “Though from his youth a professor of religion [he] was averse to joining any church, not believing that any of the sects walked up to the precepts contained in the Bible. . . . In 1832, while residing in Hector, Tompkins County, New York, having heard of the Latter Day Work, he borrowed a Book of Mormon from a neighbor, and having carefully perused it, became convinced of its truth.”[34]

Israel Barlow, a friend and neighbor of the Youngs, was another Mendon resident who was actively affiliated with the Reformed Methodist Church. The date and circumstances of his conversion to that faith are unknown. However, his exhorter’s certificate has survived as follows:

To all whom this may concern.

This may certify that We the Conference of The Methodist Reformed Church of the State of New York do grant to Br Israel Barlow license to improve his gift by Exhortation.

By order of the Conference.

[signed] Alvin Clark

[signed] L D G Pomfrey Aug 27th 1830.[35]

Recognizing an increased potential for proselytizing in the area, Phinehas related: “We immediately opened a house for preaching, and commenced teaching the people according to the light we had; a reformation commenced, and we soon had a good society organized, and the Lord blessed our labors. The members of the Baptist Church, with their minister, all seemed to feel a great interest in the work; the reformation spread, and hundreds took an interest in it. Thus things moved on until the spring of 1830.”[36]

The Young Family’s Introduction to Mormonism

During the month of April 1830, Phinehas had been preaching in the town of Lima, Livingston County, and was returning to his home in Victor, Ontario County, New York, by way of the town of Mendon, Monroe County. He stopped at Tomlinson’s Inn and “while engaged in conversation with the family,” Phinehas said, “a young man came in, and walking across the room, to where I was sitting, held a book towards me saying, ‘There is a book, sir, I wish you to read.’ . . . I hesitated, saying ‘Pray sir, what Book have you?’ ‘The Book of Mormon, or as it is called by some, the Golden Bible.’”[37]

Phinehas purchased the volume and took it home, as he described it, to “make myself acquainted with its errors, so that I can expose them to the world.” However, he reluctantly admitted, “To my surprise I could not find the errors I anticipated, but felt a conviction that the Book was true.”[38]

When members of the local congregation in Mendon asked Phinehas to give his views on the book, he rehearsed, “I had not spoken ten minutes in defence of the book when the Spirit of God came upon me in a marvelous manner, and I spoke at great length on the importance of such a work, quoting from the Bible to support my position, and finally closed by telling the people that I believed the book.”[39] He then shared his copy of the Book of Mormon first with his father, John Young Sr., and then his sister Fanny Young Murray. Both believed its contents to be the word of God.[40] Brigham also became aware of that very volume. He stated, “The next spring [1830] I first saw the Book of Mormon, which Bro Samuel H. Smith brought and left with my brother Phinehas H. Young.”[41]

The following August, Joseph Young, who had been preaching for the Reformed Methodists in Canada, came to see Phinehas and requested that he return with him to his field of labor. They left for Kingston, Upper Canada, on about August 20. Their route took them through the township of Lyons, Wayne County, New York, where they paused to visit with “an old acquaintance by the name of Solomon Chamberlin.” That acquaintanceship was undoubtedly associated with the mutual bond that the parties had previously shared within the Reformed Methodist faith. However, the Young brothers were surprised by Solomon’s unexpected declarations.[42] Phinehas recounted:

We had no sooner got seated than he began to preach Mormonism to us. He told us there was a Church organized, and ten or more were baptized, and every body must believe the Book of Mormon or be lost.

I told him to hold on, when he had talked about two hours setting forth the wonders of Mormonism—that it was not good to give a colt a bushel of oats at a time. I knew that my brother had but little idea of what he was talking, and I wanted he should have time to reflect; but it made little difference to him, he still talked of Mormonism.[43]

How much of an immediate impact this Book of Mormon discussion had on Joseph Young is difficult to measure. However, Joseph later recalled, “It was at this place I first had sight of the Book of Mormon. It was shown to us by Solomon Chamberlain. Nothing could have been more acceptable to my famishing soul. I hailed it as my Spiritual Jubilee, a deliverance from a long night of darkness and bondage.”[44]

Solomon had also given Phinehas some substantive matter to ponder. Phinehas observed, “This was the first I had heard of the necessity of another church, or of the importance of rebaptism; but after hearing the old gentleman’s arguments on the importance of the power of the holy priesthood, and the necessity of its restoration, in order that the power of the gospel might be made manifest, I began to enquire seriously into the matter, and soon became convinced that such an order of things was necessary for the salvation of the world.”[45]

Reaching Kingston, Ontario, Upper Canada, the brothers moved on to their principal destination at Ernestown, where a congregation of Reformed Methodists had been gathered. Their preaching centered in the Ernestown and Loughborough districts. Phinehas, however, was unable to concentrate on his teaching because he “could not think of but little except the Book of Mormon.”[46] Experiencing feelings of futility, he finally announced to Joseph his intentions to return to Mendon. En route to the United States, he attended a quarterly conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Kingston. At the hotel that night, he gave an impromptu address to some one hundred of the conference members on the subject of the “Golden Bible.”[47]

Phinehas next took boat passage to Oswego on Lake Ontario, then a canal packet to Manlius, Onondaga County, New York, where he attended an annual conference of the Reformed Methodist Church. There he met his old friend Solomon Chamberlin, who “had come to offer the conference the Book of Mormon, saying that if they rejected it they would all go to destruction.” Phinehas stated, “He soon filled his mission, and was driven from the place by the voice of the conference.”[48] Solomon later described the stiff opposition which greeted him at Manlius Center:

I thot if I could see the reformed Methodists I could convince them of the truth of the Book of Mormon. I accordingly went to one of their conferences, where I met about 40 of their preachers and labored with them for two days to convince them of the truth of the Book of Mormon, and they utterly rejected me, and the Book of Mormon. One of their greatest preachers so called, by the name of Buckly, (if I mistake not) abused me very bad, and ordered me off from their premises. . . . At this conference was Brigham and his brother Phinehas Young, they did not oppose me but used me well.[49]

While traveling back to Lyons, he attended the Reformed Methodist camp meeting where he contended about the Book of Mormon with “one of their greatest preachers,” William Lake, whom he had known in Vermont. Solomon said of the encounter, “He utterly condemned it and rejected it, who spurned at me and the Book and said, if it was of God, Do you think He would send such a little upstart as you are round with it[?]”[50]

The direct rejection of the Book of Mormon by the conference and associated camp meeting was certainly in keeping with Article I of the Articles for Faith and Practice of the Reformed Methodists as set forth in 1814.

ARTICLE I. Of the Scripture.

The scriptures of the old and new Testament, being written under the influence of the Spirit of God, are the only rule, and the sufficient rule of faith and practice (when received in and applied by the spirit of God, by which they were dictated.) For if God designed them as a rule, they must be adequate to the purpose intended; and therefore whatever contradicts express Scripture, or is not read therein, or can be proven thereby, is not to be enforced or adopted as matter of belief, or received as of divine authority.[51]

Phinehas returned to Mendon with John P. Greene, who had also come to attend the conference. At home he struggled to put his newfound knowledge in perspective. He observed, “I still continued to preach, trying to tie Mormonism to Methodism, for more than a year, when I found that they had no connection and could not be united, and that I must leave the one and cleave to the other.”[52]

The initial dilemma that Phinehas faced is understandable. Many attempted to reconcile the comparative beliefs with a design to make the pieces fit. In accounting for some of the successes experienced by Mormon missionaries working among the Reformed Methodists in Canada, Richard E. Bennett explained:

There existed many similarities between the gospel of Mormonism and that of the Reformed Methodists. For one to transfer his allegiance from one to another did not require widescale abdication of principle or even of major theological philosophy. Like Mormonism, Reformed Methodism was of very recent vintage, having split with the parent Methodist Episcopal Church in Vermont in 1814. Like Mormons, the Reformed Methodists believed that “the true church had apostatized,” which in turn demanded a restoration. Unlike the standard Episcopal Methodist Church from which they had broken off, the Reformed Methodists placed much emphasis on faith that worked miracles. They believed in spiritual gifts such as healing the sick, speaking in tongues, casting out of devils, etc. Repentance was a cardinal principle and admission into the church came by way of baptism by immersion. Once converted, members were expected to engage in zealous proselyting efforts to spread the new word to the world. . . . The missionary zeal of Mormonism fit perfectly well into their previous pattern of missionary labors.[53]

Conversions and Baptisms

At this time of great decision making, sometime during the fall or winter of 1831, Phinehas H. Young and other family members and friends were visited by five Mormon elders from Pennsylvania: Eleazer Miller and Daniel Bowen from Columbia Township, Bradford County; and Enos Curtis, Alpheus Gifford, and Elial Strong from Rutland Township, Tioga County. These men were performing short-term missions in the Mendon-Victor area, where they were instrumental in teaching Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and a number of others about the Church. Heber C. Kimball confirmed, “For the first time I heard the fullness of the everlasting gospel.” The Pennsylvanian missionaries also labored in Warsaw, Genesee County (later Wyoming County), and Angelica, Allegany County.[54]

In this context, it is interesting that during the fall of 1831, some of the Pennsylvania missionaries from this same branch at Columbia—Brothers Strong, Potter, and Bowen—served a mission to Shaftsbury, Vermont, the old stronghold of the Reformed Methodist Church and the “combination.” Elder Daniel Bowen was born in Shaftsbury, which probably accounts for their going there. Elder Elial Strong reported, “A few received the work.”[55]

An exchange visit was made to Pennsylvania by the Mendon-Victor investigators Brigham Young, Miriam Young, Phinehas Young, Clarissa Young, and Heber C. Kimball. They called on the branch of the Church in Columbia, Bradford County, during January 1832. Their visit lasted about a week, and they became, as Brigham said, “still more convinced of the truth of the work, and anxious to learn its principles and to learn more of Joseph Smith’s mission.” They returned to Mendon, “preaching the Gospel by the way” to relatives and friends.[56]

Energized by his experience with the Columbia Branch, Brigham Young immediately left for Canada to see his brother Joseph. Brigham traveled with his brother-in-law John P. Greene as far as Sackett’s Harbor, Jefferson County, New York. John was on his way to his preaching circuit under assignment from the Methodist Protestant Church. When Brigham found Joseph, he explained to him what he had learned concerning the gospel.[57] Later, as Joseph Young spoke of this period in his life and the events leading to his decision to return with Brigham, he mused, “I was Ripe for Receiving something that would feed My Mortal Cravings and this Seemed to Be the food I wanted.”[58] He further reminisced: “I heard something of a Golden Bible [in 1830]. . . . What then did I do? I followed along in the old way, (or Methodist order,) for two long[,] long years [until 1832]. After which when I had witnessed many of the visions [concerning the coming forth of the Golden Bible], I referred to, I left the Province of Upper Canada, with Brother Brigham and travelled some hundred miles, and arrived at my father’s house in Mendon, Monroe County, State of New York and there tarried a few days.”[59]

Phinehas, John Young Sr., and Joseph Young left immediately for Bradford County, Pennsylvania, to see the elders in the Columbia Branch. Convinced of the truth of Mormonism, Phinehas was baptized by Elder Ezra Landon, while his father was baptized by Elder Daniel Bowen, on April 5, 1832.[60] The next morning, April 6, Joseph Young was baptized by Elder Bowen. A man named William Quigly, who had joined the Youngs en route to Columbia, was also baptized. On April 7, Phinehas, his father, and William Quigly left on their return trip. However, Joseph chose to remain longer to absorb as many of the tenets of Mormonism as he could. While there he took a short-term mission into New York with Brother Lyman Leonard, who was laboring among his kinsman and others. They visited Dryden, Tompkins County; Homer, Courtland County; Smyrna, Sherburne, and Oxford, Chenango County; and Chenango Point (Binghamton), Broome County, New York.[61]

That same month, Brigham Young entered the waters of baptism in Mendon on April 15, 1832.[62] Elder Eleazer Miller of Pennsylvania performed the baptismal ordinance, confirmed him “at the waters edge,” and then ordained him an elder at Brigham’s home. The new convert confessed, “I felt a humble, childlike spirit, witnessing unto me that my sins were forgiven.” His wife, Miriam, was also baptized about three weeks later.[63]

Leonard Arrington commented on the baptisms taking place within the Young family in this period of the Restoration:

It is a remarkable fact that all of Brigham Young’s immediate family became Mormons, and all remained loyal, practicing Mormons throughout their lives. In the single month of April 1832, John Young and his wife, Hannah, Fanny and her new husband, Roswell Murray, Rhoda and John Greene, Joseph, Phinehas and his wife, Clarissa, Brigham and Miriam, and Lorenzo and Persis were all baptized. The remaining members of the family were not far behind. Susannah, married to William Stilson in 1829, was baptized in June, and Louisa and Joel Sanford joined later the same year. Nancy and Daniel Kent joined in Tyrone in 1833, while John, Jr., after a thorough investigation of the church and its tenets, was baptized in October 1833. Eleven of the Youngs proved to be “valiant” in the faith.[64]

Filled with the fire and zeal of missionary work, Joseph and Phinehas Young were joined by the Pennsylvania elders Elial Strong, Eleazer Miller, Enos Curtis, and one unnamed brother for a mission into Canada. The company left for Ernestown and Loughborough, Canada, in early June 1832. There a perfect seedbed had been prepared by Joseph and Phinehas Young as preachers for the Reformed Methodist Church. Their arrival coincided with the close of the annual conference of the Reformed Methodists and the quarterly meeting of that faith. The Mormon missionaries attended the quarterly meeting, but Phinehas said, “The priests had heard that I had become a Mormon, and consequently did not know me, although it was not two years since I had preached in the house and attended a conference with the most of them where we then were.”[65]

When the Reformed Methodist meeting ended, Phinehas requested permission to preach in their house at five o’clock that evening. Reluctantly they were told that they could do so. The Mormon leaders preached to a packed house, and Phinehas said that he enjoyed “good liberty.” A flood of invitations to preach followed. For six weeks, the brethren preached in the area and were gratified to raise “the first branch in British America.”[66]

The presence of the Mormon elders was electric. Elial Strong and Eleazer Miller reported, “Thousands flocked to hear the strange news; even so that the houses could not contain the multitude, and we had to repair to groves. Hundreds were searching the scriptures to see if these things were so. Many were partly convinced and some were wholly.”[67] Among the converts who came into the Church at this time were James and Philomela Smith Lake. The Lakes lived in the town of Camden, immediately north of Ernestown, and were baptized by Elder Eleazer Miller. The other elders elected to return to the United States in July 1832, but Joseph Young chose to remain in Canada until the following September. He was successful in organizing a second branch of the Church in the area.[68]

Unable to stay themselves from this productive field of labor, Joseph and Brigham Young started again for the West Loughborough area in December 1832 for a six-week mission. They were successful in baptizing some forty-five persons in the area. Among that number were Artemus Millet and Daniel Wood.[69] Wood explained that the previous summer (1832), the Mormon elders who came to the town of Loughborough had met in his house and that “a number of the neighbors with my self believed in baptism but they left before any of us were baptized.” The void occasioned by the departure of the elders opened a prospective door to the Reformed Methodist minister Robert Perry. Daniel Wood described the circumstance:

A little over a year passed before we saw any other Elder during which time quite a number of us continued to meet together and read the scriptures and we became so convinced that it was necessary to be baptised that we requested Mr. Robert Perry a reformed Methodist who was a reputed good man to baptize us. We continued to read and pray untill the beginning of Eighteen thirty three when two Elders Joseph and Brigham Young came and preached to us and showith us more perfectly the order of the Church of Christ then we all with one accord went forth and was rebaptized by one who had been called and ordained to administer in the ordinances of the house of God.[70]

Joseph and Brigham Young organized a branch at West Loughborough of twenty persons and then returned to Mendon, New York, during February 1833.[71]

Anxious about his Canadian charges, Brigham again left Mendon for Loughborough on April 1, 1833. He paused long enough in the town of Lyons, New York, to baptize thirteen people and to organize a branch of the Church before pursuing his journey to Canada. Following the doctrine of gathering, Brigham rallied the Saints from the greater Kingston area and formed them into a traveling company. The families of James Lake, Daniel Wood, and Abraham Wood were among the members of the camp. About July 1, 1833, Elder Young led the contingent to Kirtland, Ohio, where they were taught by the Prophet Joseph Smith. Brigham then returned to Mendon.[72]

Certain members of the John Young family left western New York in 1832 in response to the call to gather. Some journeyed to Kirtland while others initially headed for Jackson County, Missouri, before circumstances altered their plans. Other family members remained in New York until 1833 before undertaking the journey west.[73] As their dedication to the Church increased, the Youngs severed ties with the Reformed Methodist Church, save for occasional contact with members of that faith encountered in their proselytizing and daily living.

As for the fortunes of the Reformed Methodists, they continued as a recognizable entity for a season. In 1837 the sect began the publication of the South Cortland Luminary under the auspices of the New York conference, with Wesley Bailey as editor. The press operation was moved to Fayetteville, New York, in 1839, and the paper became the Fayetteville Luminary.[74] In 1845 the Reformed Methodist Church was enumerated as having “conferences, 5; preachers, 75; members, 3,000.”[75] Emory Stevens Bucke gave a synoptic portrayal of the church’s ebbing existence as a recognizable entity:

It must be admitted the denomination was growing weaker. Pliny Brett himself and one whole conference in Ohio joined the Methodist Protestant Church, and about 1838 one half of the ministers and several societies of the Massachusetts Conference also joined the Methodist Protestant Church.

In the fall of 1841 an association was formed between “the Reformed Methodists, Society Methodists, and local bodies of the Wesleyan Methodists” to aid one another without merging. The name of the magazine The Fayetteville Luminary was changed to The Methodist Reformer, and in 1842 it was move[d] to Utica, New York.

The denomination continued for a considerable time longer, its growth never reaching beyond five thousand members. Eventually most of its societies merged with the Methodist Protestant Church, and the denomination ceased to exist.[76]

Conclusion

In our quest to know the Young family, we should not overlook a careful investigation of the influences of the Reformed Methodist Church in its members’ lives. There are still source materials yet to be uncovered about the interaction of the Youngs and others with Reformed Methodism. Many of early Latter-day Saints, including the Youngs, either affiliated with the society or were associated with its members in the United States and Canada. A thorough examination of these Saints’ personal diaries and reminiscences could significantly add to our understanding of the denomination and its effect on Mormonism. Also, a careful perusal of the Reformed Methodist publications would open a valuable view into their doctrine and polity, which had such an appeal in those formative days surrounding the emergence of the Restoration under the Prophet Joseph Smith.[77]

Notes

[1] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 1844–1846,” 1, Church Archives, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

[2] James Amesy Little, “Brigham Young,” unpublished manuscript, Church Archives, 2; see also Larry C. Porter, “Whitingham, Vermont: Birthplace of Brigham Young—Prophet, Colonizer, Statesman,” in Lion of the Lord: Essays on the Life and Service of Brigham Young, ed. Susan Easton Black and Larry C. Porter (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1995), 6.

[3] Leonard Brown, History of Whitingham from Its Organization to the Present Time (Brattleboro, VT: Frank E. Housh, 1886), 169.

[4] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” 1.

[5] Wesley Bailey, “History of the Reformed Methodist Church,” in An Original History of the Religious Denominations at Present Existing in the United States, comp. I. Daniel Rupp (Philadelphia: J. Y. Humphreys, 1844), 466.

[6] Emory Stevens Bucke, ed., The History of American Methodism (New York: Abingdon, 1964), 1:622. Reverend Pliny Brett later left the Reformed Methodists and joined the Protestant Methodists (see Rupp, An Original History, 474).

[7] Bucke, History of American Methodism, 1:622.

[8] Lewis Cass Aldrich, ed., History of Bennington County, Vt. (Syracuse, NY: D. Mason, 1889), 486.

[9] Rupp, An Original History, 466.

[10] Rupp, An Original History, 466.

[11] The Reformer’s Discipline (Bennington, VT: Darius Clark, 1814), 3–4.

[12] The Reformer’s Discipline, 4–21.

[13] Rupp, An Original History, 467; Bucke, History of American Methodism, 1:622–24.

[14] Rupp, An Original History, 474.

[15] Land Deed Records, Book 7, 277–80; Book 7, 344–46, Shaftsbury Town Offices, South Shaftsbury, Vermont.

[16] Solomon Chamberlin, A Sketch of the Experience of Solomon Chamberlin, to Which Is Added a Remarkable Revelation, or Trance, of His Father-in-Law Philip Haskins: How His Soul Actually Left His Body and Was Guided by a Holy Angel to Eternal Day (Lyons, New York: n.p., 1829), 4–5. Solomon spelled his name Chamberlin rather than Chamberlain in his day.

[17] Dean C. Jessee, ed., “The John Taylor Nauvoo Journal, January 1845–September 1845,” in BYU Studies 23 (Summer 1983): 44–45.

[18] See Captain David Matthews file, Bennington Museum, Old Bennington, Vermont.

[19] Rupp, An Original History, 474.

[20] Jessee, “John Taylor Nauvoo Journal,” 45; Solomon Chamberlin, “A Short Sketch of the Life of Solomon Chamberlin,” 5, letter to Albert Carrington, July 11, 1858, Church Archives.

[21] Rupp, An Original History, 471–75.

[22] Chamberlin, Sketch of the Experience, 6–7.

[23] Wayne County, New York, Land Deeds, Book 5, 374–77.

[24] Chamberlin, “Short Sketch of the Life,” 5–11, 13.

[25] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” 10.

[26] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” 10; Leonard J. Arrington, Brigham Young: American Moses (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985), 16.

[27] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” 6.

[28] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” 6.

[29] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” see “Addenda” to 7, at back of manuscript ledger, 1. John P. Greene became a member of the Reformed Methodist Church in 1825. However, after three years of preaching for that sect, he joined the Methodist Protestant Church in 1828. He was initially united with a congregation of twenty to twenty-five persons. John became a licensed traveling preacher. See Andrew Jenson, comp., Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia (Salt Lake City: Andrew Jenson History Company, 1914), 2:633; Edward W. Tullidge, The Women of Mormondom (New York: n.p., 1877), 107.

[30] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” see “Addenda” to 7, at back of manuscript ledger, 2.

[31] James Amesy Little, “Brigham Young,” 2, unpublished manuscript, Church Archives.

[32] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” 10.

[33] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” 4.

[34] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” 7. In this reference, Brigham Young said that Lorenzo was baptized in 1832 by John P. Greene, who was “residing” in Warsaw, New York. However, Lorenzo’s biographer, James A. Little, specified that John was then living in the town of Avon, New York (see James Amasa Little, “Biography of Lorenzo Dow Young,” in Utah Historical Quarterly 14 [1946]: 35).

[35] In Ora H. Barlow, ed., The Israel Barlow Story and Mormon Mores (Salt Lake City: Publishers Press, 1968), 76 77.

[36] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” see “Addenda” to 7, at back of manuscript ledger, 2.

[37] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” see “Addenda” to 7, at back of manuscript ledger, 2.

[38] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” see “Addenda” to 7, at back of manuscript ledger, 3.

[39] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” see “Addenda” to 7, at back of manuscript ledger, 3.

[40] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” see “Addenda” to 7, at back of manuscript ledger, 3.

[41] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” 10.

[42] Joseph Young, Diaries, 1844–81, 6:16–17, Church Archives; “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” see “Addenda” to 7, at back of manuscript ledger, 3.

[43] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” see “Addenda” to 7, at back of manuscript ledger, 3.

[44] Joseph Young, “Autobiographical Sketch [ca. 1872],” 6, Church Archives.

[45] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” see “Addenda” to 7, at back of manuscript ledger, 4.

[46] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” see “Addenda” to 7, at back of manuscript ledger, 4.

[47] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” see “Addenda” to 7, at back of manuscript ledger, 4–5.

[48] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” see “Addenda” to 7, at back of manuscript ledger, 5.

[49] Chamberlin, “Short Sketch of the Life,” 11–12.

[50] Chamberlin, “Short Sketch of the Life,” 12.

[51] The Reformer’s Discipline, 6. There are ten articles of faith contained in this canon of beliefs.

[52] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” see “Addenda” to 7, at back of manuscript ledger, 5–6.

[53] Richard E. Bennett, “A Study of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Upper Canada, 1830–1850” (master’s thesis: Brigham Young University, 1975), 35–36.

[54] V. Alan Curtis, “Missionary Activities and Church Organizations in Pennsylvania, 1830–1840” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1976), 76–78; “Synopsis of the History of Heber Chase Kimball,” Deseret News, March 31, 1858.

[55] Evening and Morning Star 1 (May 1833): 7. A figure of five Shaftsbury converts is given; Curtis, “Missionary Activities and Church Organizations,” 72–73.

[56] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” 10, see also “Addenda” to 7, at back of manuscript ledger, 5–6.

[57] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” 10.

[58] Joseph Young, Diaries, 1844–81, 6:19.

[59] Joseph Young to Lewis Harvey, Salt Lake City, Utah, November 16, 1880, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah; Joseph Young, Diaries, 1844–81, 6:18–21.

[60] Joseph Young, Diaries, 1844–81, 6:21–23; “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” 2, 5.

[61] Joseph Young, “Autobiographical Sketch,” 7; Joseph Young, Diaries, 1844–81, 6:18–21; “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” see “Addenda” to 7, at back of manuscript ledger, 6.

[62] In 1862 Brigham Young stated, “It is thirty years the 15th day of next April (though it has accidentally been recorded and printed the fourteenth) since I was baptized into this Church” (Journal of Discourses [London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1855–86], 9:219).

[63] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” 10–11; for an extensive treatise of Brigham Young’s conversion and baptism, see, Ronald K. Esplin, “Conversion and Transformation: Brigham Young’s New York Roots and the Search for Bible Religion,” in Black and Porter, Lion of the Lord, 20–53.

[64] Arrington, Brigham Young: American Moses, 20.

[65] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” 5, see also “Addenda” to 7, at back of manuscript ledger, 3.

[66] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” see “Addenda” to 7, at back of manuscript ledger, 6.

[67] Eliel Strong and Eleazer Miller to Brethren in Zion, Rutland, Pennsylvania, March 19, 1833, in Evening and Morning Star, May 1833, 94; see also Melvin S. Tagg, “A History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Canada, 1830–1963” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1963), 17.

[68] Andrew Jenson, Biographical Encyclopedia, 2:387–89; Roy A. Prete, Carma T. Prete, and Mark Prescott, eds., Zion Shall Come Forth: A History of the Ottawa Ontario Stake (Kingston, Canada: Ottawa Ontario Stake, 1996), 7.

[69] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” 12.

[70] Daniel Wood, Journals (ca. 1862–1900), 2, Church Archives. The 1826 home of Daniel Wood still stands in what is today Sydenham, near the north shore of Sydenham Lake on the south side of Bedford Road.

[71] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” 5; Bennett, “A Study of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,” 38; Jenson, Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:187; Ben V. Bloxham, James R. Moss, and Larry C. Porter, eds., Truth Will Prevail: The Rise of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the British Isles, 1837–1987 (Solihull, West Midlands: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1987), 14.

[72] “Manuscript History of Brigham Young,” 12; Prete, Prete, and Prescott, Zion Shall Come Forth, 8–9.

[73] Arrington, Brigham Young: American Moses, 34–37.

[74] Rupp, An Original History, 476; see also Bucke, History of American Methodism, 1:624.

[75] American Almanac and Repository of Useful Knowledge for the Year 1845 (Boston: James Munroe, 1844), 199.

[76] Bucke, History of American Methodism, 1:624. For the rise of the Methodist Protestant Church from its regular organization in 1830, see James R. Williams, “History of the Methodist Protestant Church,” in I. Daniel Rupp, ed., History of All the Religious Denominations in the United States (Harrisburg, PA; John Winebrenner, 1849), 380–82.

[77] Such publications as The Reformer’s Discipline (Bennington, VT: Darius Clark, 1814); Elijah Bailey, Primitive Trinitarianism, Examined and Defended (Bennington, VT: Darius Clark, 1826); and Elijah Bailey, Thoughts on the Nature and Principles of Government, Both Civil and Ecclesiastical, ff. (Bennington, VT: Darius Clark, 1828), are highly instructive on Reformed Methodist beliefs and discipline. Access to the content of certain reformer periodicals is available at Olin Library, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, and the Fayetteville Public Library, Fayetteville, New York.