From Scripture to Screen

Films Depicting Jesus and the World of the New Testament

Scott C. Esplin and Matthew J. Grey

From an interview by Scott C. Esplin, publications director for the BYU Religious Studies Center, with Matthew J. Grey, associate professor of ancient scripture at BYU.

Esplin: How did you get interested in the genre of biblical cinema and, specifically, films depicting Jesus?

Grey: My professional interest in Jesus films began when I started teaching courses on the New Testament at BYU. In doing so, I quickly found that a careful and historically contextualized reading of the Gospels often challenged the preconceived notions many students have about Jesus, including his appearance, demeanor, and relationship to early Judaism, as well as the cultural world in which he lived. As I would ask students what informed their previous assumptions, the most common response indicated that they were influenced by the ways in which Jesus is depicted in art or in the movies. This prompted a feeling of professional obligation to become more familiar with Jesus films and how they contribute to students’ understanding of the New Testament so I could better mediate between their preconceptions and what we find in the scriptural text.

Photo by Cody Bell. Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Photo by Cody Bell. Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Esplin: What have you learned about the ways Jesus has been depicted in film?

Grey: Biblical films have always both reflected and influenced the religious sensitivities of the generations in which they are produced, and it has been fascinating to explore how, over the last hundred years, certain cinematic themes and images have helped shape public perception of Jesus in particular. For example, beginning with the silent films of the early twentieth century and continuing through the Hollywood epics of the 1960s and ’70s, Jesus was typically depicted in ways that closely parallel the European artistic tradition with which religious audiences have long been familiar. In these depictions, Jesus is most often portrayed as a middle-aged northern-European who is well groomed, wears long white robes, has a beatific countenance, teaches in opposition to his Jewish contemporaries, functions in a highly sanitized world, and is extremely limited in his emotions, all of which reflects traditional notions of Jesus’s divinity but distances him both from his first-century Jewish context and from his human surroundings. As a result, such depictions—advertently or inadvertently—have often made it difficult for film audiences to connect with Jesus since in the portrait of him they are used to seeing he doesn’t seem to get dirty on the roads of first-century Galilee, be at home in his Jewish environment, or even interact with others on a human level.

However, in a careful and historically contextualized reading of the New Testament Gospels we see a Jesus who physically does not stand out from his contemporaries (but who instead was eastern Mediterranean in his ethnicity, complexion, and appearance), would have worn the common clothing of Roman Palestine (a short tunic and mantle, rather than a long white robe), operates fully within his early Jewish context (rather than in opposition to it), and expresses a wide range of human emotions that make him a much more compelling and dynamic personality than audiences are used to seeing.

I have enjoyed trying to help students navigate these differences between biblical cinema and the scriptural text—not in a way that dismisses the artistic qualities of Jesus films (which often contain beautiful images, convey inspiring emotions, and should be appreciated in their own right), but in a way that allows students to become more aware of the influence films have on popular perceptions, deepens students’ scriptural literacy, and increases their historical awareness. I have found that by placing Jesus films into conversation with the New Testament and other historical sources, students can have a much richer experience both reading the Gospels and watching scripture-based media.

Esplin: How have Jesus films changed or developed in recent decades?

Grey: Beginning around the turn of the millennium, there have been a number of subtle but important shifts in the way Jesus has been depicted on screen. For example, in films of the last twenty years we have begun to see hints of Jesus’s humanity that go beyond the more pious portrayals of their cinematic predecessors, such as allowing him to smile or laugh, showing him dance or banter with his disciples, or showing him experience emotions of pain, frustration, and annoyance along with feelings of happiness, understanding, and sympathy for those around him. I believe that these shifts are a fascinating reflection of the changing spiritual and entertainment needs of audiences in the early twenty-first century. Unlike their moviegoing parents and grandparents (who embraced more traditional forms of biblical storytelling and the image of an emotionally distant deity), viewers of the current generation seem to resonate more with a depiction of Jesus they can relate to, whose human experience contributes to his divine attributes, and who extends compassion to those who are broken, marginalized, or longing for a sense of purpose (all of which has gradually begun to appear in more recent Jesus films).

Also, within the last twenty years, films have started to depict Jesus in more ethnically appropriate ways (by casting non-European actors to play the role), to show more of the grittiness of first-century life (by recreating the poverty of Galilean villages), and to highlight ways in which Jesus operated within his early Jewish religious setting (by having him say Jewish prayers, wear Jewish religious items, and observe Jewish holy days). These developments have not only made important strides toward reflecting a greater historical accuracy in Jesus films, but have attempted to speak to the spiritual needs of modern viewers, many of whom want to see Jesus working in a more realistic setting and yearn to engage with a more relatable style of biblical storytelling.

Esplin: In your view, how do these depictions impact Latter-day Saints?

Grey: Like other religious viewers, Latter-day Saints are heavily influenced by the images and messages of the films they watch. Historically, the more traditional Jesus films seem to have had a significant impact on Latter-day Saint perceptions of Jesus and the world in which he operated. This can have a lot of spiritual benefits (especially as many of these films have provided valuable inspiration and faith-informing perspectives), but it can also have its disadvantages. For example, if Latter-day Saint viewers are accustomed to imagining Jesus as an emotionally distant divine being that is fundamentally different from his human surroundings (as seen in traditional film depictions), that is going to have an impact on their religious experience, including ways they view God and their relationship to him. On the other hand, as Latter-day Saints interact with films that try to bridge the gap between Jesus’s divinity and humanity (as many are beginning to do), that can have an effect on their spiritual experience as well; only now they can start relating to Jesus on a human level—fully appreciating his divine qualities, but also seeing visually that Jesus knows what it’s like to walk on a dirty street, laugh at a dinner table with his friends, be disappointed when something doesn’t go quite right, and experience complex relationships.

Also, now that Latter-day Saint audiences are beginning to see films in which Jesus more fully engages with his Jewish surroundings and appreciates the richness of his Jewish heritage, it can refine the way they view Jesus’s teachings and their perception of other faith communities. This can help inspire them to experience holy envy and to see the beauty in other faith traditions (such as early Judaism) while still recognizing the distinction of their own. These are all ways in which the powerful medium of film can affect our scriptural literacy, our historical awareness, our religious experience, and our approach to Christian discipleship.

Esplin: What can you share with us about Church efforts to produce films about Jesus?

Grey: For many years, Latter-day Saints mostly relied on “outside” productions for their biblical media. In the early 1990s, though, the Church began to produce its own Jesus films for use in seminary classes, missionary efforts, and home instruction. The first of these was a short video called the Lamb of God which, as hoped, inspired many students, missionaries, and families by showing scenes from the ministry, suffering, and resurrection of Christ from a Latter-day Saint perspective. It is interesting to note, however, that when the Church began producing its own material, its depiction of Jesus and its approach to scripture followed the most conservative trends of traditional Jesus films. For example, in the Lamb of God Jesus has only a few lines (all of which are reverently spoken in King James English), the orchestral musical score carries most of the film’s emotional weight, and it takes great care to not diverge from the biblical text, all of which reflects a respectfully cautious treatment of the scriptural content but at the same time limits the film’s ability to tell a compelling story (as good cinema is meant to do).

This challenging tension between scriptural cautiousness and cinematic appeal continued into the early 2000s when the Church produced its next major Jesus film, The Testaments. While mostly a Book of Mormon film, it occasionally depicts scenes from Jesus’s New Testament ministry. These scenes mostly attempted to recreate traditional pieces of art (such as the well-known Carl Bloch paintings), and thus offered a more familiar portrait of Jesus rather than one that challenged viewers to think about him in new ways. These approaches to depicting Jesus continued in the Life of Jesus Christ Bible videos (2011–13), for which the Church built an elaborate Jerusalem set in Goshen, Utah, to film over a hundred Gospel scenes, all shown with strict adherence to the King James text of the New Testament.

The most recent and innovative development among Church-produced Jesus films was The Christ Child—a twenty-minute film about the birth of Jesus for the Church’s 2019 Light the World campaign. This production represented an important step forward for biblical storytelling in Church media in several ways. First, in The Christ Child we begin to see more of the complexity of scriptural characters, such as Mary and Joseph who laugh and smile at one another and who clearly connect to each other on an emotional level. There’s also some fictional dialogue, which is very rare in Latter-day Saint Bible films; this dialogue is in Aramaic, but it’s inspiring to see, hear, and feel aspects of the story’s first-century setting. Finally, The Christ Child made an unprecedented effort to present a historically informed portrayal of the Christmas story by incorporating several refinements to the traditional story based on historical or archaeological research. All of these facets of The Christ Child contributed to the success and enthusiastic reception of the film, both within and outside of the Latter-day Saint community.

Esplin: What role do scholars like yourself play in these productions? How have you and others been personally involved?

Grey: Scholars are often involved at various levels in these films, typically to offer scriptural or historical advice to the directors, screenwriters, set designers, or actors. For instance, I was honored to be invited as one of the historical consultants on The Christ Child, along with colleagues such as Richard Holzapfel (a former BYU professor who provided valuable guidance throughout the production process), David Calabro (an ancient language expert who wrote the Aramaic dialogue), and Jason Combs (an ancient scripture professor who offered insightful “behind the scenes” commentary). For me, involvement in The Christ Child began in the scriptwriting phase when I was asked to review an early draft and offer feedback. It was gratifying to help with some of the scriptural and historical aspects of the script, such as maintaining the film’s scriptural integrity by separating Luke’s account of Jesus’s birth from Matthew’s account. As a result, the first half of the film shows the story from Luke 2 of Mary and Joseph coming to Bethlehem and finding that there was no room in the family house (which is a more historically plausible scenario than traditional depictions of this scene), as well as the experience of the shepherds with their witness of the newborn Jesus. In the second half, the film shifts to the story in Matthew 2 by showing the wise men follow the star until they come to the house in Bethlehem where Joseph, Mary, and “the young child” Jesus are living (details from Matthew’s account that do not often appear in film). In these ways, we were able to feature some interesting scriptural perspectives and try to make the film more historically informed in terms of the family situation, travel dynamics, and even the different ages of Jesus, while at the same time telling an emotionally compelling story.

Matthew Grey with Brooklyn McDaris (the actress who played Mary) on the film set for The Christ Child. Photos courtesy of Matthew Grey.

Matthew Grey with Brooklyn McDaris (the actress who played Mary) on the film set for The Christ Child. Photos courtesy of Matthew Grey.

As the film moved on to production, I was also able to be on set, interact with the actors, and have some rich conversations with the production team about various historical and scriptural issues the film could address. For example, in between scenes I was talking with Brooklyn McDaris (the actress who played Mary) and, when I found out that she was a professional singer, shared with her the story from Luke 1 of Mary singing a scripturally informed hymn (the “Magnificat”) in response to her miraculous conception; even though that particular story was not a part of the script, both Brooklyn and John Foss (the film’s director) became excited about the scriptural possibility it opened up and spontaneously added a beautiful scene in which Mary sings a Hebrew lullaby to the baby Jesus as a nod to her expression of praise in Luke 1. This type of interaction between filmmakers and historians can result in powerful media that is both historically informed and emotionally compelling, thus representing the best of both worlds.

Esplin: What do you hope viewers learn from these productions?

Grey: One of the great strengths of cinema is its ability to bring a topic to life for its audiences. In the case of Jesus films, such productions have a remarkable potential to connect modern viewers with ancient scripture in an emotional and visual way that sometimes the biblical text can’t do alone. Along with recognizing this great strength of biblical cinema, however, I would also hope that students or viewers of these films recognize that film is ultimately an artistic medium. Like other forms of art, film excels at being able to provide emotional resonance, symbolic reflection, and creative beauty for its viewers (all of which should be fully appreciated in its own right), but film is not typically meant to be a historical documentary that presents the most current research on its subject (that is the work of trained historians). As a result, I would hope that—along with enjoying the various artistic aspects of what they are watching—viewers allow Jesus films to point them toward the most reliable scriptural sources and biblical scholarship for a more robust, informed, and nuanced understanding of the story. Learning to appreciate these various layers of film can deeply enrich the viewing experience and help facilitate a deeper level of scriptural literacy.

Esplin: There has been great interest in a recent television show called The Chosen. What can you share with our readers about this most recent attempt to depict the life of Jesus?

Grey: The Chosen is the first multiseason television drama (by evangelical filmmaker Dallas Jenkins) that seeks to tell the story of Jesus “through the eyes of those who knew him.” The series is an inspiring attempt to imagine in fictional ways the backstories of Jesus’s earliest disciples, their complex personalities and relationships, and their transformative encounters with Jesus. In the process, it offers a portrayal of scriptural characters with their strengths, weaknesses, triumphs, and struggles that allows viewers to see themselves on the challenging but joyful path of discipleship. It also explores the humanness of Jesus in a relatable way that goes beyond more traditional depictions by allowing him to feel joy in his miracles, wrestle with God in knowing how to fulfill his mission, laugh, joke, sing, and dance with his disciples, and extend compassion to those who are broken, marginalized, or longing for a sense of purpose, all while maintaining a deep respect for Jesus’s divine identity and mission.

This compelling portrayal of Jesus and the disciples in The Chosen definitely belongs in the category of “scriptural fiction” (it takes several liberties with the Gospel texts) and struggles to accurately depict various historical matters (such as the nature of early Judaism, daily life in first-century Galilee, and the extent of Roman military occupation in the region), but its relatable style of biblical storytelling offers many viewers their first opportunity to connect deeply with the characters and world of the New Testament on screen; as such, The Chosen represents an important step forward in faith-based biblical cinema. It has also been interesting to watch this series become one of the rare “outside” scriptural media projects embraced within the Latter-day Saint community in recent decades, as reflected in its sponsorship by VidAngel (a streaming service owned by Latter-day Saints), its now-regular appearances on BYUtv, and the official invitation by the Church to film its second season at the Jerusalem set in Goshen.

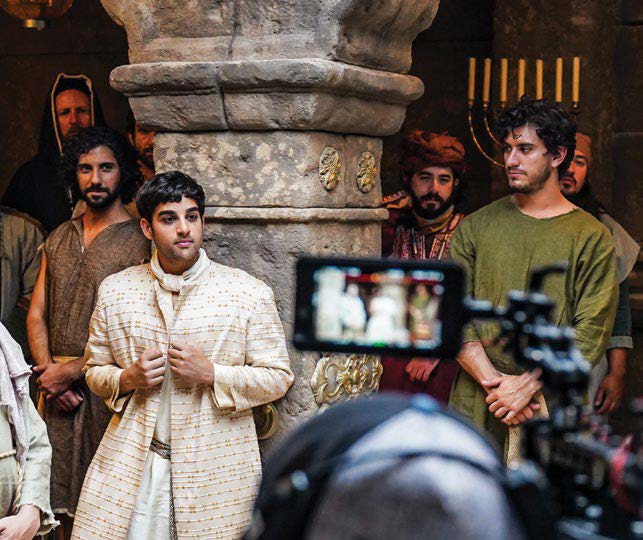

Filming The Chosen television series. © 2020 VidAngel. All rights reserved.

Filming The Chosen television series. © 2020 VidAngel. All rights reserved.

Esplin: As one who studies the context, history, and life of Jesus, what do you hope to see in future films depicting him?

Grey: As a historian of early Judaism and an archaeologist who focuses on Roman Palestine, it has been great to see the increasing interest by filmmakers in depicting Jesus in ethnically appropriate ways, showing more realistic recreations of daily life in first-century Galilee, and placing Jesus within his Jewish context. I would hope that, going forward, future films build on these trends and that we continue to see even higher levels of historical accuracy in terms of casting, costuming, sets and props, and the social, political, and religious setting of the Jesus story. These are all aspects of the New Testament world we continue to learn more about through historical, archaeological, and biblical research, and it would be fun to see more of this scholarship being incorporated in Jesus films—both as a way to show a respect for the Jesus story by getting it right and to better contextualize Jesus’s teachings for audiences by showing their originally intended significance.

Also, now that Jesus films are starting to move past some of the pageantry of previous generations, I would hope that future projects continue to boldly explore aspects of Jesus’s personality, ministry and teachings that we have not often seen on screen. For example, very few films have attempted to reflect Jesus’s apocalyptic worldview, have fully engaged his more challenging social commentary, or have shown him immersed in first-century Jewish religious debate. These are all aspects of Jesus’s life and message that are prominent in the New Testament Gospels but that have, for the most part, yet to be explored in film. Incorporating them into the more familiar cinematic portraits could be a powerful way for future films to help modern audiences more fully appreciate, understand, and relate to Jesus.

Esplin: As we conclude, how has your study of films about Jesus helped you come closer to the Savior?

Grey: For me, placing Jesus films, the New Testament text, and historical sources into thoughtful conversation has prompted valuable questions that I might not otherwise have asked about a wide range of issues, including Jesus’s appearance, personality, teachings, and ongoing social relevance, as well as the nature of scriptural writings. Often these questions come as I find myself wondering why film directors made certain decisions, how I might have presented things differently as a believing historian, and what the implications of those decisions might be for the spiritual experience of the viewers. I often find that asking those type of questions facilitates richer inspiration as a teacher, academic insights as a scholar, and spiritual experiences as a believer, all of which have been a great blessing in my personal efforts to get to know Jesus better, to help increase the faith and scriptural literacy of my students, and to strengthen my own discipleship.