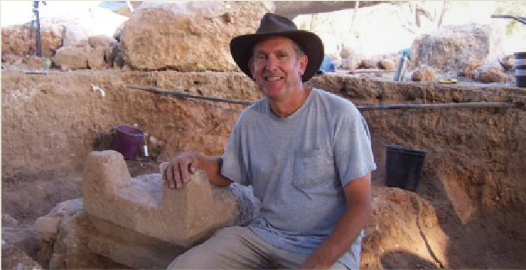

Jeffrey R. Chadwick (jrchadwick@byu.edu) was an associate professor of Religious Education and Jerusalem Center Professor of Archaeology and Near Eastern Studies when this was written.

“Go down to Gath of the Philistines,” said Amos the prophet (Amos 6:2). For the last dozen years, that’s exactly what I have done each summer, leaving the comfort of the BYU Jerusalem Center for an hour’s drive through the picturesque countryside of Israel down to Tell es-Safi, the huge mound that was once the capital city of Philistia. As senior field archaeologist for the Tell es-Safi/

Since 2001, it has been my privilege to represent BYU in excavating and researching at Gath. My participation has been supported by the BYU Religious Studies Center and generous donors to BYU Religious Education and facilitated by the BYU Jerusalem Center. I also represent BYU as a senior research fellow at the highly respected W. F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research in Jerusalem. The Tell es-Safi/

We opened Area F in 2004 at the very top of the 150-acre site, a 300-foot-high mound at the west end of Israel’s famous Valley of Elah. This hilltop was the elite zone of Gath, the place where the Philistine king Achish maintained his palace three thousand years ago when he hosted the young warrior David, who was on the run from King Saul. The ruins of that palace were obliterated in the twelfth century AD when Crusaders built their own fortress complex on the hilltop. But the remains of Canaanite and Philistine houses ring the site on the terrace below the summit. As my crew of twenty-five Jewish and Christian graduate student supervisors and undergraduate volunteers carefully unearth the wall foundations of those structures, I cannot help but occasionally wonder whether one of these was the home of the city’s most famous elite warrior—Goliath of Gath.

Excavations at Gath have shown that the ancient city was inhabited from the Early Bronze Age forward, beginning around 3000 BC. Both its prime location in Canaan’s coastal plain, which foots the hill country of Judah, and its massive size and impressive height made it the most powerful and influential site in the entire region. Gath was the largest city in the entire southern area of the country during several ancient periods. Results from the scientific excavation efforts of the Tell es-Safi/

1. The Middle Bronze Age city wall of Gath. Built around 1600 BC, the wall served the city for nearly 800 years—four centuries through the Canaanite periods and four centuries through the Philistine periods. The wall foundations were three meters thick and supported a massive brick superstructure which rose an estimated ten meters high, protecting the houses built on the terraced levels inside the city. This was the very type of fortification spoken of in the Bible; the Israelites were intimidated by Canaanite cities which were “walled up to heaven” (Deuteronomy 1:28).

2. Houses from the Late Bronze Age city of King Shuwardata. The rogue king of Canaanite Gath (ca. 1350 BC) mentioned in the famous El-Amarna letters from Egypt. Pharaoh Akhenaten simply could not maintain control over Shuwardata and Gath at that time, to the chagrin of the other Canaanite kings. The Canaanite houses we are still excavating were built right up against the inside of the city wall, just like Rahab’s house at Canaanite Jericho (see Joshua 2:15).

3. A short Egyptian inscription mentioning the “prince of Tzafit,” which sheds light on a biblical passage. Judges 1:17 mentions a city that can only be Gath but calls it Tzafit (Hebrew Tzafit is rendered as “Zephath” in the King James Version). Ancient biblical cities often had dual names (such as Hebron/

4. Houses from the Iron Age Philistine city of Gath, beginning in the twelfth century BC. This was the period of the Judges, when the Philistines invaded Canaan from the sea and became the new foe of the biblical Israelites. The story of Samson (see Judges 13–16) involves the Philistines, and the lost ark of the covenant was kept at Gath during this period (see 1 Samuel 5:8). Goliath came from this city (see 1 Samuel 17:4), and David stayed at Gath with King Achish (see 1 Samuel 27).

5. The destruction of Philistine Gath by King Hazael of Syria. In Area F, and indeed over the entire site of Tell es-Safi, a thick destruction layer bears witness to the devastating attack and siege on Gath which took place around 840 BC and which was mentioned in 2 Kings 12:17. At 130 acres, Iron Age IIA Gath was the largest city in the entire land (larger than Jerusalem or Samaria). The Syrian attack destroyed Gath so thoroughly that the Philistine capital never recovered, and it lay desolate thereafter for decades. Its devastation is alluded to in Amos 6:2.

6. Widespread evidence of the earthquake mentioned in Amos 1:1. We have unearthed piles of broken and scatted brick from the walls of abandoned Philistine buildings which collapsed in the strong earthquake that struck around 760 BC. Our engineering assessment of the g-force that produced the collapses suggests a devastating earthquake of about 8 on the Richter scale.

7. The Judahite houses at Gath from the time of King Hezekiah of Judah. We have learned much from excavating two houses from the late eighth century BC, when Iron Age IIB Gath was a border town of the kingdom of Judah. When Sennacherib attacked Judah in 701 BC, the town was destroyed and its Israelite inhabitants were carried away to Assyria (see 2 Kings 18:13).

8. An impressive kitchen and bakery from Judahite Gath. We uncovered a large baking hearth, a huge basalt millstone installation, and a seven-handled “barrel pithos” jar (200-quart capacity!) for grain storage, along with numerous other pottery vessels, including intact olive oil juglets, the biblical “cruse.” These reminded us of the words of Elijah: “the barrel of meal shall not waste, neither shall the cruse of oil fail” (1 Kings 17:14).

9. Houses from the Persian and Roman periods. These structures date to the times of Malachi in the Old Testament to Matthew in the New Testament, when Gath was known as Safita in Greek.

10. The wall and tower of the Crusader fortress Blanche Garde. Built around AD 1140 to control the road from the coast to Jerusalem, Blanche Garde was a fortress where the English king and warrior-knight Richard the Lionheart stayed on his way to Jerusalem to battle against the Muslim warrior Saladin.

We will be back in the field in July 2013 for our tenth season of excavation in Area F at Gath, and I am again grateful for the generous support of donors to BYU Religious Education which makes teaching, research, and outreach efforts such as these possible. We will keep you informed on what we find!