The Scattering and Gathering of Israel

God’s Covenant with Abraham Remembered through the Ages

Victor L. Ludlow

Victor L. Ludlow, “The Scattering and Gathering of Israel: God’s Covenant with Abraham Remembered through the Ages,” in Window of Faith: Latter-day Saint Perspectives on World History, ed. Roy A. Prete (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005), 97–120.

As Latter-day Saints study world history of the past few centuries, they naturally look at these historical events from their own contemporary perspective. They also tend to search for connections between ancient scriptural prophecies and modern historical events that relate to the restoration of Christ’s church and its growth. Indeed, to better appreciate some key historical events of recent centuries, one should step back—way back in time—and look at these occurrences from the ancient perspective of Abraham, the patriarch-prophet, who received unique covenant promises from God.

The Abrahamic Covenant

God instructed Adam and Eve, and they in turn taught their posterity concerning Christ’s atoning sacrifice and relevant gospel principles and practices (see Moses 5:5–12, 13–15, 58–59; 6:1). The ancient patriarch-prophets taught the gospel to succeeding generations throughout the ages (see Moses 6:22–23, 27–30; 8:13, 16, 19–24). Eventually, Abraham sought for the blessings, truths, and priesthood that his ancestors had received from God (see Abraham 1:2–4). He was told by the Lord that he would be taken with God’s blessings and power to another land (see Abraham 1:16, 18–19). The Lord later told Abraham that he would become a great nation with numberless posterity that would be a blessing unto all nations (see Abraham 2:9–10; 3:14).

By the time of Abraham’s entrance into Canaan, it appears that some faithful communities of children of God were scattered throughout the world. The Jaredites, a Semitic people of Book of Mormon fame, had left Babylonia much earlier and were already well established in the Americas (see Ether 1–2, 6). And as Abraham left Ur and traveled southwestwards towards the western regions of the Fertile Crescent, Melchizedek, the righteous high priest, reigned over Salem in Canaan (see Genesis 14:17–20). Also around this time, Job was a just and faithful patriarch in Uz, a land eastward of Canaan (see Job 1:1–5). Abraham was selected to receive special covenant promises that would carry through to the end of this earth’s history and into eternity.

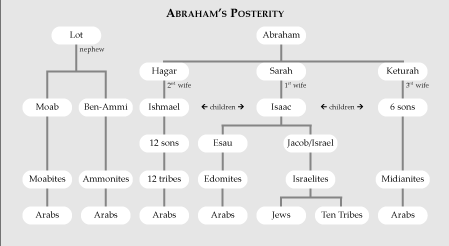

God entered into His special covenant with Abraham around 1900 BC, and His covenant included three major promises. First, Abraham was promised a numberless posterity (see Genesis 13:16), one that started slowly with eight sons through three wives and that gradually grew to include several million Arabs, some two million Jews, and unknown millions of other descendants (such as the ten tribes and other scattered remnants of Israel). With the Industrial Revolution and improved living and health standards, Abraham’s posterity has exploded into hundreds of millions of living descendants today (see chart on page 3).

Second, Abraham was given a promised land (see Genesis 15:18), a region in the Middle East between Egypt and the Euphrates River that the empires of Egypt, Assyria, Babylon, Persia, Greece, and Rome controlled during most of the ancient era. Abraham’s descendants briefly controlled this region in medieval times as Islamic armies established an Arab empire in southwest Asia and north Africa during the ninth and tenth centuries. But foreign armies, especially the Turks from central Asia, then invaded and controlled this region for many centuries. After the British defeated the Turks during World War I, they gave political control of the lands promised to Abraham to various Arab and Jewish groups, who now argue and war over these “promised” lands.

The third promise to Abraham was that his descendants would be a blessing to all nations and families of the earth (see Genesis 12:2–3; 22:16–18). Most importantly, Jesus Christ, who atoned for the sins of all mankind, was born through his lineage. Other important spiritual blessings were delivered by the ancient prophets and other righteous descendants of Abraham. Eventually, Abraham’s posterity was to bear the priesthood and the gospel to all nations so that “the blessings of salvation, even of life eternal” might be extended to “all the families of the earth” (Abraham 2:9–11). And, as will be highlighted later, Abraham’s posterity has provided many religious blessings as well as significant secular advancements to the world through the ages.

These three covenant promises made to Abraham were only partially fulfilled some 3,500 years later as Europe came out of the dark ages of medieval feudalism. Since the middle of the fifteenth century, these three divine promises with Abraham have rapidly moved toward their fulfillment. It seems that the greatest blessings of Abraham’s posterity to the earth will occur in latter days as enlightened and righteous descendants fulfill special missions to God’s children. The house of Israel indeed has the mission in our times of taking the gospel message to all the world.

Although the Lord promised the house of Israel great blessings as the heirs through Isaac and Jacob of the full Abrahamic covenant, these blessings were conditional upon their exercising their agency in righteousness as they honored their covenants with God. Because of Israel’s disobedience to covenant promises with the Lord, the children of Israel were scattered among the nations of the earth, as the Lord had warned, but with the promise of an eventual gathering (see Deuteronomy 29–30).

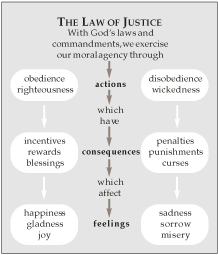

Israel’s punishments follow the classic pattern of the law of justice: our actions or reactions to the laws of God and the universe lead to certain consequences, which will result in experiences and feelings, which bring either happiness or sorrow into our lives. The law of justice relates to the other divine laws and provides the means by which people receive their just reward. In essence, the law of justice might be summarized as follows:

Every law has both a blessing and a punishment attached to it.

Whenever a law is obeyed, a reward must be given.

Whenever the law is transgressed, a punishment must be inflicted.

The choice between good and evil presupposes agency; the exercise of our agency activates the law of justice and its resulting blessings and punishments. Without choices, we cannot exercise agency and experience the full range of blessings and punishments (see 2 Nephi 2:5–27; Alma 12:31–32; 42:17–25). The Prophet Joseph Smith’s teachings as recorded in the Doctrine and Covenants indicate that blessings and punishments are predicated upon compliance or non-compliance with divine laws, commandments, and judgments (see D&C 82:10; 121:36–37; 130:20–21). The Lord is absolutely just in rewarding each individual according to his or her works based upon individual levels of knowledge, accountability, and motivation (see Romans 2:5–6; 2 Nephi 9:25; Mosiah 3:11; Alma 41:2–6; 3 Nephi 27:14). In essence, the law of justice might be illustrated as follows:

The Law of Justice

Abraham’s posterity was free to choose between good and evil after they obtained God’s laws and covenants. They were promised they would either become a great nation or be scattered among the nations as they received either blessings and joy for their obedience or punishment and misery for their disobedience (see Deuteronomy 26–30). Abraham’s family was directed to the western regions of the Fertile Crescent, an area where the crossroads of commerce and ideas connected the peoples of Asia, Africa, and Europe. The land of Canaan and the cities of Hebron and Salem (later known as Jerusalem) could have become as famous and significant to the whole world in the moral and spiritual realm as Athens and Rome would later be in the philosophical and political realms. Unfortunately, as a whole, Abraham’s ancient posterity did not live true to their covenants, and they did not provide an exemplary role model to other peoples of the earth. Indeed, the Old Testament record is a witness of their continual disregard for the prophetic word and their disobedience to the commandments and covenants which the Lord had given them.

Although, as will be highlighted later, some of Abraham’s descendants provided wonderful blessings and advancements to civilization in later times, the great potential for good which they could have shown the world was not fulfilled in ancient times. Indeed, Abraham’s descendants tended to follow the wicked ways of the world, and thus their influence for good did not reach its full potential. The Ishmaelites, Edomites, Israelites, and others of Abraham’s posterity suffered repeated conquest and subjection. The house of Israel in particular forfeited her presence in her original lands of inheritance and was scattered among the nations. Although remnants of Israel, the Jews, would return in latter days, they still are not fully living the laws and commandments of God. In addition, some of Abraham’s contemporary descendants (especially the fanatical zealots among the Arabs and Jews) seem to be more of a curse than a blessing to the world community as their regional disputes and the aggressive actions of their leaders escalate into international conflicts.

We now need to review how these three promises of posterity, land, and being a blessing as given in the Abrahamic covenant have evolved over the centuries. First, we will summarize how Abraham’s posterity has multiplied into key peoples and nations of the latter days. Then, we will highlight the major historical events concerning Abraham’s posterity and their promised land during the past four millennia, especially in connection with the scattering and gathering of the house of Israel as the earth and her inhabitants were prepared for the gospel restoration. Finally, the effects and blessings of Abraham’s descendants will be discussed so that we can better understand their special influence upon latter-day events. Discerning how the three great Abrahamic promises have unfolded over the past four millennia, especially in more recent times, helps us recognize their pivotal role and significance in contemporary events.

Abraham’s Posterity through the Ages

Abraham was a Hebrew Semite born around 2000 BC in the eastern regions of the Fertile Crescent along the Euphrates River, the heartland of the Middle East. After the Great Flood, many Semites (the descendants of Shem, the son of Noah) had populated lands throughout southwest Asia, especially the Middle East. Among the Semites were the descendants of a patriarch-king named Iber (or Heber). Many of them were traveling merchants known as the Ibiru (or Hebrews), also called “donkey men” because of the primary means of transporting their goods throughout the Middle East. The most famous Hebrew of all was Abraham, who married three women: Sarah, Hagar, and Keturah. As listed in Genesis, Abraham had eight sons and almost two dozen grandsons. As promised by the Lord, Abraham’s posterity gave rise to many nations. The following chart shows how the Arabs and Israelites, including the Jews, descended from Abraham

As seen from the chart above, the later Arab tribes included descendants of both Abraham (primarily through Ishmael’s lineage) and Lot. Note how the ancestors of the Arabs multiplied into more nations and greater numbers far more rapidly and extensively than the Israelites, who were descendants of Jacob, just one of the twenty-one known grandsons of Abraham (see 1 Chronicles 1:29–34). [1]

The Israelites themselves divided into two smaller kingdoms of ten and three Israelite tribes around 930 BC. [2] The Ishmaelites, Edomites, Midianites, and other related tribes who would later become the foundation for the Arab peoples remained in the regions of the Middle East, while the two Israelite nations were conquered by the Assyrians and the Babylonians, and many Israelites were transported throughout the empires of their conquerors. Other Israelites relocated to foreign lands, such as Lehi’s family and the Mulekites to the Americas, Jeremiah and many Jews to Egypt, the ten tribes northward into Asia and Europe, and any number of other families to different corners of the world as the Israelite people scattered among the nations. This dispersal of Israelites continued for centuries, and as they intermarried and assimilated among the peoples of the earth, most of them lost their identity with the house of Israel. But they were known to their Heavenly Father, who had covenanted with their ancestors that He would remember them and bring them back into His favor, gathering them to their promised lands in the last days (see 3 Nephi 21:26–29).

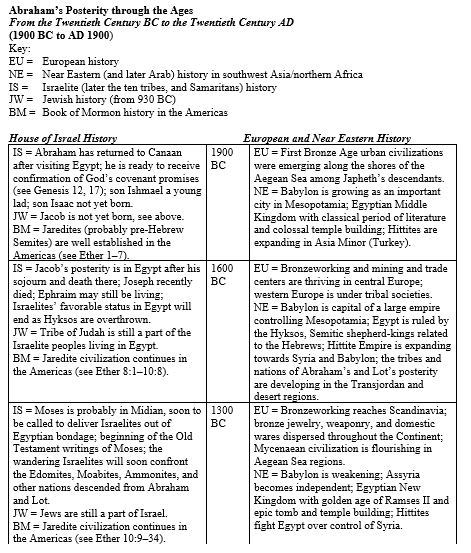

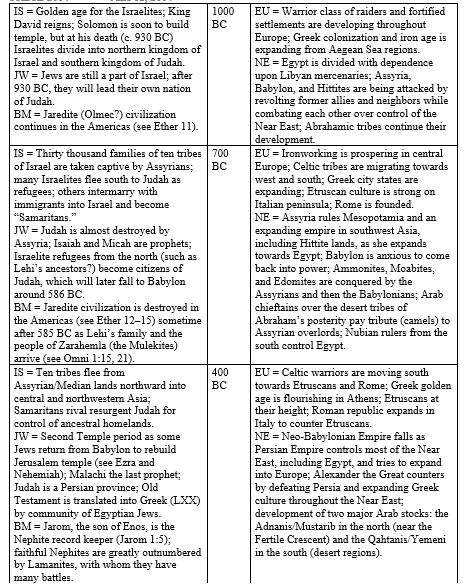

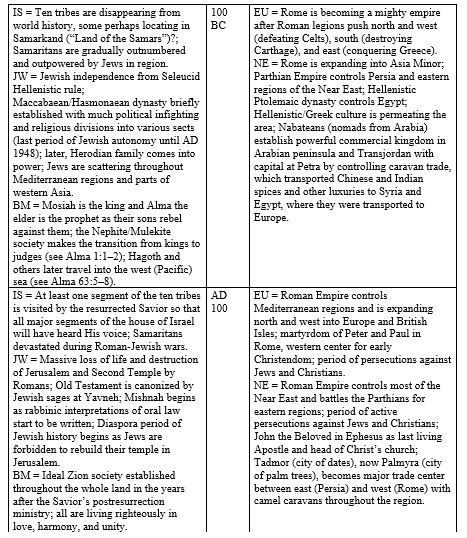

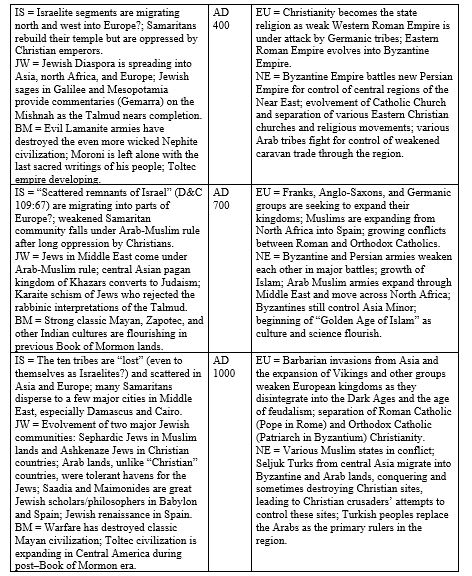

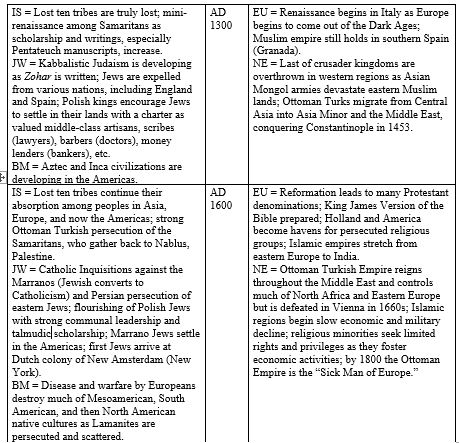

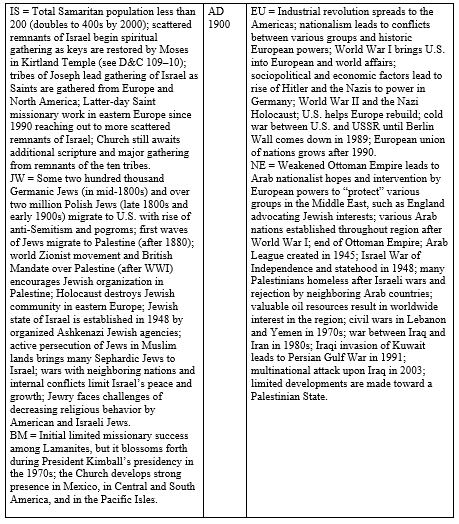

The following chart highlights some pivotal historical events during the millennia since God gave His promises to Abraham. To provide a consistent historical framework for these events, the historical context of Europe and the Middle East is also given. Note how the status of the three major segments of the house of Israel (ten tribes, Jews, and Nephites/

Though cursory, this chart gives us a quick overview of what has happened to Abraham’s posterity, especially among segments of the house of Israel, over the past four millennia. It also highlights political and other developments in the ancient lands promised to Abraham’s posterity. As in the scriptures, the central focus is upon connections and developments with the house of Israel.

Allegory of the olive tree. A symbolic portrayal of these events is found in Zenos’s allegory of the olive tree. Zenos provides a profound prophetic overview of essential elements about the scattering and gathering of Israel. Although the scattering and gathering are literal, historical, physical events, they also reflect a more important dimension of a spiritual scattering, and in the latter days their gathering as seen in the mission of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The mission of the Church is to bring us unto Christ through missionary work, perfecting the Saints, and temple work. The inseparable relationship between the concept of gathering and the spiritual mission of spreading the gospel, nurturing members in the Church, and maintaining family ties is beautifully illustrated in the allegory of the vineyard recorded and commented upon in Jacob 5–6 in the Book of Mormon. Jacob records this allegory from the writings of an otherwise unknown prophet Zenos of the Old Testament period. The allegory is summarized in the following paragraphs, with a historical interpretation written in italics.

Zenos compares the house of Israel to an olive tree that the Lord planted and nourished in the good soil of His vineyard. After a time, despite the Lord’s persistent care, the tree began to decay and the main branches started to wither (verses 1–7). Though settled and preserved in the promised land of Canaan, Israel rejected the word of the Lord until she was nearly destroyed. To preserve what He could of the tree, the Lord took some surviving branches and planted them in various places throughout the vineyard (verses 8, 13–14). The ten tribes, Lehi’s family, the Jews, and other remnants of Israel were scattered throughout the world.

In place of the original tree’s natural branches, the Lord grafted in branches of wild trees as a stimulant in hope that they might bear good fruit if nourished by strong roots (verses 9–12). Rejected by Israel, the gospel was given to the gentiles in Palestine and throughout the world. For a while, the wild branches did bear good fruit, but in time they began to overrun and sap the strength of the roots (verses 15–18; 29–37). The early apostolic Christian Church flourished among the gentiles but soon fell into apostasy. The natural branches scattered through four parts of the vineyard also started to bear good fruit, but in time they all turned wild (verses 19–29, 38–47). Scattered Israel also received Christ and His gospel but fell into apostasy.

Later, to preserve the roots, the Lord cast off the wild branches and grafted in again from the natural branches (verses 48–59). The Lord then started to gather the house of Israel again into the gospel fold and their lands of inheritance. The Lord seeks to preserve the best of the natural and wild branches. These can yet bear an abundance of good fruit, which He will gather in and store against coming seasons (verses 60–68). The Lord gathers and restores Israel to her lands of promise as He fulfills the ancient covenants. Gentiles who embrace the gospel are numbered among the redeemed house of Israel. The restoration of the vineyard takes place as the wild branches are burned and the Lord enjoys His bounteous harvest (verses 69–77). The Lord destroys the remainder of the wicked world prior to His Second Coming and glorious millennial reign.

In Zenos’s extensive allegory, the roots of the natural tree were the only thing that could ultimately produce and preserve good fruit. These roots are the Abrahamic covenant and our ancestral ties to it. We nurture these roots as we perform vicarious ordinances for our deceased ancestors through temple work. The natural branches of the olive tree, like our established families in the Church, propagate themselves abundantly, complementing and reinforcing each other while drawing their strength from the roots of faith and righteous tradition. We nourish these branches as we perfect the Saints in the household of faith. The grafted branches that also bear good fruit are converts to the Church from among the gentiles. We multiply and strengthen these branches as we proclaim the gospel to all peoples through missionary work. Thus, Zenos’s allegory of the olive tree portrays the threefold dimension of fulfilling the mission of the Church. [3]

The holy scriptures and historical facts combine to give us insight to how the disobedience and wickedness of the house of Israel led to the Israelites forfeiting their promised lands and divine protection as they were scattered throughout the earth. Although this scattering was a punishment to the unfaithful Israelites, it did provide some blessings to other peoples as these Israelites carried scriptures, gospel teachings, moral-ethical values, and other blessings of the house of Israel to various peoples and nations. But the house of Israel was not to remain forever scattered among other nations. God had promised that He would return them to their lands of inheritance. Just as a spiritual wickedness had led to the physical scattering, in the latter days a spiritual awakening would lead to the physical return of the remnants of Israel to their lands, where they could become a righteous nation again.

Pattern of scattering and gathering. Of particular interest is the notable pattern of the scattering, which began in the eighth century BC, and the gathering of the house of Israel, which began with the Restoration and has not yet been completed. The pattern is found often in the scriptures: the first shall be last and the last shall be first (see Matthew 19:30; D&C 29:30). This pattern was also prophesied concerning the scattering and gathering of Israel (see Jacob 5:63).

Because of many generations of wickedness, the nation of Israel was broken up into four main parts: (1) the “lost” ten tribes, some of whom disseminated throughout the Middle East and others of whom fled from the Assyrian yoke after their deportation from Israel in 721 BC; (2) the Book of Mormon exiles (Nephites, Lamanites, and the people of Zarahemla or the so-called Mulekites), who fled Jerusalem around 600 BC (and whose descendants are now usually called Lamanites); (3) the house of Judah (the Jews), which was scattered by the Babylonians (586 BC) and the Romans (AD 70); (4) and other scattered remnants of Israelites (particularly the house of Ephraim) who mixed in among the Gentiles over the course of many centuries.

Except for the Jews, the great majority of the descendants of these ancient Israelite groups lost their distinctive identity. They became “lost” as they mixed in among the nations of the earth or forgot their religious heritage. With the passage of time, they forgot their origins in Samaria and Judea as they blended in among other religions and cultures. But they were not hidden to the Lord.

In reverse order, Israel would be gathered, starting with the scattered remnants of Ephraim among the Gentiles (in the early and mid-1800s, with the keys of the gathering of Israel being restored by Moses to Joseph Smith in the Kirtland Temple in 1936) and continuing with the Jews gathering to their land of inheritance (from the 1880s until today, with the modern state of Israel being founded in 1948). The descendants of Lehi, now known as Lamanites, started blossoming as a rose and coming into the gospel fold in the 1970s, highlighted with the organization of nine new Latter-day Saint stakes in Mexico City in the fall of 1975. As we now come into the present, perhaps the dismantling of the iron curtain and missionary work in eastern Europe and central Asia will lead to the gathering of remnants of the ten tribes.

Thus, the first group scattered (the ten tribes) will be the last group gathered as the New Jerusalem is finally established and the Savior’s millennial reign begins. And the last group scattered (the remnants of Israel, especially descendants from Ephraim, who are probably a sub-group split off from the ten tribes that settled among the gentile nations) would be the first group gathered as the early Church leaders, who come from this group, began the restoration of all things and received the keys for the gathering of Israel (see D&C 109:57–60). This distinctive pattern of scattering and gathering is illustrated in the following chart:

The Scattering and Gathering of the House of Israel

The first shall be last and the last shall be first!

(see Jacob 5:63; Matthew 19:30; Ether 13:12; D&C 29:30)

Scattering

This pattern of Israel’s scattering and gathering can be illustrated in a simple chiastic pattern. Chiasmus is a stylistic pattern in which a series of words or ideas is stated and then repeated, but in a reverse order. Chiastic parallelism is a common literary and public communications style used by Israelite poets and prophets. A chiasmus can transmit sublime, divine teachings that are relevant for God’s children upon the earth today. A chiastic pattern of A–B–C–D–D’–C’–B’–A’ is seen in the chart above.

As can be seen by the earlier historical review and the basic outlines shown above, important elements of the gathering of the house of Israel have occurred in the past few centuries, especially since the Church was established in 1830. Significant historical events in Church history, Jewish history, and Nephite/

Abraham’s Posterity Blesses the Nations of the Earth

As the Savior told the people at Bountiful, God’s covenant with the house of Israel had not yet been fulfilled when He visited them during His resurrection ministry (see 3 Nephi 15:8). Before the covenant could near completion, key promises concerning Abraham’s descendants, their promised lands in the Middle East, and their potential blessings and contributions to the world had to be fulfilled. First, hundreds of millions, even billions, of people needed to become Abraham’s posterity. Much of this descendant growth has happened with the population explosion of the past few centuries. Also, the land promised Abraham needed to come under the control of his posterity. As the Savior delivered these teachings in AD 34, Rome governed these Middle Eastern lands and centuries later the Ottoman Turks and the British ruled them, but within the past century they have come under the control of Abraham’s descendants, the Arabs and Jews. Finally, many of the blessings that Abraham’s posterity were to give to the nations and families of the earth had not yet been delivered two thousand years ago; they would come forth in connection the establishment of God’s final gospel dispensation in the latter days.

The following is just a brief sampling of how Abraham’s descendants (including the Arabs, Israelites, and Jews) have blessed the peoples of the earth, especially since the Savior’s earthly ministry. Abraham’s posterity has blessed humankind through three great religions—Christianity, Islam, and Judaism—and these blessings have reached into all dimensions of our lives.

In the spiritual and religious realm, Christianity, which had its roots in earlier Judaic practice, has become the religion of 1.9 billion people, or 31.1 percent of the population of the world. The Judeo-Christian tradition, which derives from the spiritual labor of Abraham’s descendants, is a foundation of Western civilization, providing social and political values and the moral and ethical basis of the legal systems. That same tradition has made an emotional and psychological contribution in defining the value and purpose of life, the goodness of God, His love for all, and the Golden Rule as a guide for human conduct. In the social and cultural realm, the themes of the Bible have provided inspiration for great works of architecture, music, art, literature, and entertainment.

A second great world religion, that of Islam, arose among the Arab descendants of Abraham in the seventh century and has become the second largest world religion, with 1.2 billion followers, or 19.7 percent of the world’s population. The contributions of Islam in the areas of science, mathematics, philosophy, art, literature, architecture, and technology have been considerable. Islam has served as the moral and ethical basis of many nations, and its leavening influence has been felt in several empires, including those of the Turks, Persians, and Mughals.

The Jewish contribution, in addition to the spiritual and religious realm, has been remarkable in many areas, including discoveries in natural and social sciences, medicine, and philosophy. Although Jews make up fewer than one out of every five hundred people on the earth, individuals of Jewish descent typically receive one of every every five Nobel Prizes. These descendants of Abraham have also made important contributions in their professions as merchants, businessmen, and bankers; in accountability; and in the improved lifestyle and the moral-ethical values of our society.

The following chart summarizes how Abraham’s family has contributed to the different important areas of our lives:

Spiritual/

Moral/

Intellectual/

Social/

Emotional/

Physical/

Material/

Starting with the atoning sacrifice of Jesus, one of Abraham’s descendants, and continuing to the Judeo-Christian foundation of Western civilization, to the Arabic development of numbers and algebra, to the discovery of the polio vaccine by the Jewish doctor Jonas Salk, to the efforts of Ephraim’s descendants to restore Christ’s Church and to build His kingdom on earth—the seed of Abraham have blessed the people of the earth abundantly over the past two millennia. The Restoration of the gospel through his descendants has brought modern prophets, priesthood, new scriptures, temples, and missionary work. Of special significance is the role his descendants are filling in bringing about the gathering of the house of Israel in these latter days. Missionary work and other programs of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints assist in the gathering and blessing of the house of Israel. This gathering and eventual restoration of the major segments of Israel to their promised lands of inheritance are necessary preparations for Christ’s Second Coming and the establishment of His millennial reign.

Key Scriptural Promises of the Gathering and Restoration

Multiple prophetic viewpoints of a latter-day return of the house of Israel are provided in the Bible and other scriptures. [5] Major scriptural passages concern not just the gathering to their lands of inheritance but, more importantly, the restoration of the covenant house of Israel to their promised lands in the latter days. The return of the house of Israel in the last days seems to be in two phases: a gathering phase and a restoration phase. Gathering refers to their being brought together from their scattered places, whereas restoration refers to God’s renewal of covenants with them unto their lands of inheritance. This return of the house of Israel will reveal God’s great power and promises. As Jeremiah prophesied:

Assuredly, days are coming—declares the Lord—when it will no more be said, As the Lord lives who brought the Israelites out of the land of Egypt, but rather, As the Lord lives who brought the Israelites out of the northland, and out of all the lands to which he had banished them. . . . Lo, I am sending for many fishermen—declares the Lord—. . . . And after that I will send for many hunters. . . . For My eyes are on all their ways, they are not hidden from My presence, their iniquity is not concealed from my sight. . . . Assuredly, I will teach them, once and for all I will teach them My power and My might. And they shall learn that My name is Lord [Jehovah or Yahweh] (Jeremiah 16:14–21). [6]

Thus, the gathering of Israel in the last days will be recognized as a greater miracle than when the Lord earlier delivered Israel out of Egypt.

As discussed earlier in this chapter, the prophet Zenos, in his allegory of the olive tree, foretells the natural branches (house of Israel) being scattered and transplanted in four different parts of the vineyard (see Jacob 5:8, 13–14, 20, 23, 24, 25). He then prophesies their later gathering and being grafted back into the mother tree (see verses 52–60). This gathering phase was to be in reverse order of the scattering (see verse 63) until all segments would bring forth natural fruit (see verses 68, 74).

In the Book of Mormon, Lehi speaks of all Israel in 1 Nephi 10:14: “And after the house of Israel should be scattered they should be gathered together again.” Then, three later successive passages in the Book of Mormon highlight three stages or conditions that precede the gathering and restoration of the Jews in the last days. These events open the way for all of the house of Israel to be gathered and restored to the lands of their inheritance.

1. The prophet Zenos talks about the Jews in 1 Nephi 19:15–16: “Nevertheless, when that day cometh, saith the prophet, that they no more turn aside their hearts against the Holy One of Israel, then will he remember the covenants which he made to their fathers. . . . And all the people who are of the house of Israel, will I gather in, saith the Lord” (emphasis added). The first condition and promise identified is a change of attitude that leads to a gathering phase for the house of Israel to the lands of their inheritance.

2. Jacob, Nephi’s brother, records his vision of the Jews in 2 Nephi 6:11: “Wherefore, after they are driven to and fro, for thus saith the angel, many shall be afflicted in the flesh, and shall not be suffered to perish, because of the prayers of the faithful; they shall be scattered, and smitten, and hated; nevertheless, the Lord will be merciful unto them, that when they shall come to the knowledge of their Redeemer, they shall be gathered together again to the lands of their inheritance” (emphasis added). In this second condition and promise, a change of knowledge also leads to a gathering phase for Israel.

3. Jacob later says more about the Jews in 2 Nephi 10:7–9: “But behold, thus saith the Lord God: When the day cometh that they shall believe in me, that I am Christ, then have I covenanted with their fathers that they shall be restored in the flesh, upon the earth, unto the lands of their inheritance” (emphasis added). Finally, in this third condition and promise, a change of belief leads to a restoration phase for the house of Israel as they are blessed and protected in their promised lands.

The Savior foretells how the coming forth of the Book of Mormon among the Lamanites leads to the gathering of the house of Israel as God remembers His covenants with Israel (see 3 Nephi 21:1–7). And Mormon also tells how his records (the Book of Mormon) will influence the Jews as they are restored to their lands in fulfillment of God’s covenant (see Mormon 5:14). [7]

A common phrase Mormon used to summarize sections of his abridgment helps us focus our Latter-day Saint perspective of history. And thus we see the events of the past few centuries from a different perspective—from God’s prophetic view. We should study our era not just from a contemporary historical viewpoint but from Abraham’s perspective of thousands of years ago. As we look at historical events related to the house of Israel, we need to ask ourselves at least two questions: how do these events demonstrate the power and mercy of God? (see Moroni 10:3), and especially, how do these events help fulfill God’s promises concerning the scattering and gathering of the house of Israel?

Let me share my personal perspective of how prophecies related to the house of Israel help me understand two complex, puzzling events of modern Church and secular history. The first is the marvelous miracle of missionary work—the foundation of Church growth, the spiritual gathering of millions of covenant Israel. And the second is a catastrophic event of modern history—the Nazi Holocaust of the Jews, the physical destruction of millions of lineage Israel.

The Spiritual Gathering of Millions of Covenant Israel

From Zenos’s allegory and other scriptures, we know that the gospel of Jesus Christ was first preached to the Israelites, who rejected it. Christ’s Apostles then took the word to the Gentiles. When restored in the latter days, however, the gospel was first preached in the gentile nations, especially to the scattered remnants of Israel among the Gentiles (see D&C 109:57–67). It is only now being taken in force to other more identifiable remnants of the house of Israel, such as the Lamanites. Thus, as discussed earlier, the prophecy is being fulfilled that says, “The last shall be first, and the first shall be last” (1 Nephi 13:42).

The Lord has used prophets and scriptures to reveal where and how these various remnants of Israel will be gathered back together again into one flock (see 3 Nephi 15:15–17:4). Also, the Book of Mormon has revealed the location of the Lamanites in the Americas, and early missionary work quickly began to let these scattered remnants of Ephraim and Manasseh know of their Israelite ancestry. Prophets are also preparing the ten tribes for their return since, as prophesied, a remnant of them and their special set of scriptures will come forth in the last days (D&C 77:9, 14; 2 Nephi 29:11–14; 3 Nephi 21:26).

The Church’s avowed goal has been the same as that of early Christianity: to take the gospel to every nation, kindred, tongue, and people. From the 1700s to the 1900s, most Christian missionary societies concentrated on taking the gospel to the pagan and heathen nations of Africa and Asia. Joseph Smith was definitely inspired in his early missionary decisions, as he did not follow this accepted practice of the nineteenth-century Protestant missionary societies. Instead, Joseph Smith received divine inspiration to send the missionaries of the restored gospel to the Christian countries of North America and Europe, where other Christians often rebuked them and challenged them to go to the pagans instead. However, the success in the numbers of early converts from other Christian denominations and their migration to the Rocky Mountains provided the nucleus for eventual missionary work in other, non-Christian nations, especially after World War II.

From the 1950s through the 1980s, the Church steadily grew in western Europe, South Africa, and some nations along the Pacific rim. Stakes were established and temples were built to provide centers of strength. By the mid-1980s, the Church had the organization and numbers of close, strong Church members ready to take the gospel to nations formerly under the communist yoke and to other countries in Africa and mainland Asia that had earlier prohibited our activities. Now, missionary success is rapidly growing in eastern Europe, in a variety of central African nations, and in some Asian countries—all with local government recognition and full Church organizational support readily available. With further growth from Church centers of strength and with the aid of modern media and other helps, Latter-day Saints will continue their expansion into the rest of the world until the gospel message is heard by all people. In contrast, after many centuries of Catholic and Protestant missionary work, only small fractions of the “pagan and heathen” people are practicing Christians today, and their numbers do not seem to be growing.

An additional component in this pattern of missionary work is that until the 1970s the vast majority of converts to the Church came from Christian-Protestant backgrounds. These converts consisted of gentiles and scattered remnants of Israel living among the gentile nations of North America and northern Europe. Very few Catholics and non-Christians joined the Church prior to the 1960s. Today, many Protestant converts still join the Church, but many more new members come from Christian-Catholic backgrounds, primarily in Central and South America and the Philippines. For example, since the 1980s, the top baptizing missions of the Church have consistently been in these Latin countries and the Philippines. The Latin members, often called Lamanites by the Latter-day Saints, are among the descendants of the Book of Mormon community. We are also beginning to see increasing numbers of non-Christians join the Church. If this pattern continues, we can soon expect growing numbers of baptisms among the other groups of scattered Israel, such as those descendants of the ten tribes living among Muslim or formerly communist peoples. Also, other non-Christians residing in Africa and Asia will come into Christ’s Church in increasing numbers.

Thus, through modern prophets following the Lord’s way of missionary work, the goal of Christianity to take the gospel to the whole world will finally be fulfilled as people everywhere will have the opportunity to hear the restored gospel!

The Physical Destruction of Millions of Lineage Israel

As a historian with special training in Jewish history, I have attended and participated in numerous conferences, symposiums, workshops, and classes where the Holocaust has been discussed and analyzed. Although myriad facts and a great variety of explanations have been presented, we scholars feel that we may have learned a little more but that we still do not fully understand why the German people could ever have perpetuated such an atrocity. It is even more personal for me since I have lived for five and a half years in Germany and I have a deep love of the Germans and their culture. I have also lived with my family on three occasions in Israel, and I have visited that land almost thirty times over the past three decades. I have studied and associated with Jews in North America, Europe, Asia, and Africa in a great variety of settings, and I have an abiding appreciation for the Jews and their heritage. These two peoples so close to my heart share an infamous chapter of human history.

One hundred years ago, Germany was the most advanced nation on the earth. German engineering and advancements in science and medicine were renowned. The German culture had brought us Bach, Brahms, and Beethoven. How could such a cultured, advanced people ever have deliberately exterminated over six million Jews and millions of others? The question begs for answers that cannot be fully found in historical, social, political, and economical studies. However, a key perspective from a viewpoint of some prophecies concerning the house of Israel might give a valuable answer. Looking at these prophecies from the viewpoint of Satan reveals a growing mood of desperation as God’s covenants are being fulfilled in the latter days. You must remember that Satan is like a convicted felon on death row awaiting his final destiny. Satan’s punishment for his rebellion in heaven is twofold: he is cast out of heaven forever, and he will eventually be sent into outer darkness for the rest of eternity. He is awaiting the second punishment as he generates lies, rebellion, apostasy, and wickedness here on earth. From the prophecies of the scriptures, he knows his final punishment will be delivered after the Millennium. He also knows that before the Millennium can begin, some central prophecies must be fulfilled, including the Jews returning to their land and building a temple in Jerusalem prior to the Messiah’s return. Consider the implications if Satan and his forces could destroy the Jews before they returned to their promised land. With no Jews to return and build a temple, this prophecy could not be fulfilled in preparation for the Savior’s coming, and God’s word and work would have been frustrated.

In 1830, as the Restoration of the gospel was formally begun, over two million of the world’s three and a half million Jews resided in the Polish-Russian areas of eastern Europe. This eastern European Jewish community grew over subsequent generations, and the world Jewish population peaked at around 18 million in 1939. The Polish Jewish community was completely destroyed by Satan’s henchman, Adolf Hitler, and his minions during World War II. Yet the Lord’s work was not halted. Prior to the Holocaust, a few million Jews had left Europe for the United States and other nations. Also, tens of thousands of Jews migrated to the Palestine province of the Ottoman Turkish Empire. Horrendously devastating, the Nazi genocide succeeded in killing six million Jews, one-third of the world Jewish community. Nevertheless, the surviving Jews, with worldwide sympathy and politics, shortly thereafter established the Jewish state of Israel in 1948. Given the dynamics and politics surrounding the Middle East, it is doubtful if a Jewish state would ever have been established as soon as it was without the empathy engendered by the Holocaust. This failure is another bitter pill Lucifer must taste throughout eternity as he contemplates how his ambition and plans miscarried once again.

Thus, Satan’s efforts to thwart God’s prophecies not only failed, but the effects of his failed attempt helped bring about the creation of the state of Israel more quickly than it otherwise would have occurred.

Conclusion

In contrast to Satan’s failures in his attempts to thwart God’s work, Heavenly Father and His servants in His vineyard are overcoming many challenges as they fulfill His ancient promises to the house of Israel. One may well ponder how many human events have been shaped by God for the fulfillment of these promises. Throughout eternity, God and His righteous children will remember how His covenant promises were accomplished, especially as exemplified in the scattering and gathering of the house of Israel. We who live as His words are being fulfilled can either study and observe these accomplishments from the sidelines or actively participate in bringing about His work on earth. Missionary work, temple work, and our efforts in assisting one another as we build Christ’s kingdom and bring ourselves and others to Him—these are the noble labors that will help bring about the gathering and restoration of the house of Israel. Let us each do our part!

Notes

[1] The name change of Jacob to Israel is very symbolic. No longer was he to be the “supplanter” of his older brother as the recipient of the birthright, but he was to be known as “one who prevails with God,” the one who administers the covenant keys with God.

[2] Jacob’s posterity, the Israelites, evolved into thirteen tribes, one each from eleven of his sons and two (Manasseh and Ephraim) from Joseph. The northern kingdom of Israel consisted of eight whole tribes and portions of three tribes: Benjamin, Dan, and Levi. Two whole tribes, Judah and Simeon, and the remaining portions of the divided tribes resided in the southern kingdom of Judah. Thus, approximately ten tribes were in the north, and three tribes were in the south.

[3] This material is adapted from Victor L. Ludlow, Principles and Practices of the Restored Gospel (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 564–68.

[4] See “Israel, Scattering of;” “Israel, Gathering of;” and “Israel, Restoration of” in the Topical Guide of the Latter-day Saint version of the Bible for helpful lists of many scriptures relating to these topics.

[5] See 1 Kings 22:17; Isaiah 11:12, 32:15–20; Ezekiel 22:15; Zechariah 2:11–12, 7:13–14, 10:6–9, 12 and their accompanying footnotes in the Latter-day Saint edition of the King James Bible.

[6] This translation comes from The Book of Jeremiah: A New Translation (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1973).

[7] See 2 Nephi 9:2, 25:11, 16–18, 26:12, 30:7; 3 Nephi 5:26, 20:10–46 (especially verses 13 and 25), 21:1–7; Mormon 3:21, 5:14–24; Ether 13:11–12. See also D&C 35:25, 45:16–25, 43–53, 110:11 (keys of Moses); Articles of Faith 1:10; Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed., rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957), 5:336–337; Orson Hyde, Dedicatory Prayer, in Smith, History of the Church, 4:456.

Annotated Bibliography

(Books on the Middle East covering, in rough chronological sequence, ancient times to the recent conflicts)

Chahin, M. Before the Greeks. Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press, 1996. 144 pp. This book provides a brief introduction to the ancient history of the Near East as it demonstrates the cultural debt of Western society to the people of this region. It gives background information on several population groups and empires, ending about the time of Alexander the Great. It is a good introductory book as it goes into some depth but is not overwhelming.

Hoerth, Alfred J., Gerald L. Mattingly, and Edwin M. Yamauchi, eds. Peoples of the Old Testament World. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1994. 400 pp. This book takes the areas of Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Syria-Palestine, Egypt, and Transjordan and discusses the population groups found in those areas from the Early Bronze Age to the Roman period. It goes on to give good information on the history of these peoples and increases understanding when reading the Bible. A fairly easy read, it also includes major groups not mentioned in the Bible.

Knapp, A. Bernard. The History and Culture of Ancient Western Asia and Egypt. Chicago: Dorsey, 1988. 284 pp. This book provides a survey introduction to the ancient world. The time frame extends from prehistoric times to the death of Alexander the Great and extends geographically from western Asia to the borders of Greece. This book focuses specifically on social and economic aspects of ancient history, but it is presented as a political history. The book is divided into major time periods, and within each of these sections the progress of different regions is addressed. The last chapter addresses specific topics such as science, math, art, and technology rather than geographical areas.

Kuhrt, Amelie. The Ancient Near East. London: Routledge, 1995. 2 vols. 782 pp. Extending from 3000 to 330 BC, this book claims to be an introduction to Near Eastern history but is really a definitive source on the topic. There is a certain degree of selective coverage, and Egypt is excluded, but it is still a very detailed work. The author claims her target audience is undergraduates and classical ancient historians; it is strongly recommended that the reader have a previous introduction to ancient history and be ready for a challenging book. It takes some discipline to get through this work, but it is one of the most informative sources on the topic.

Sicker, Martin. The Pre-Islamic Middle East. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2000. 231 pp. Focusing on Iran, the Persian Gulf, and the Fertile Crescent, which in this case extends all the way to Israel, this book explains the interaction of simultaneous events in the region, showing the flow of geopolitical history. The book claims it is good for nonspecialists looking for an understanding of the area’s long, complex history that created today’s Middle East. The book alternately focuses on specific regions, peoples, and events, ending with the Byzantine Empire.

Van De Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004. 313 pp. The most recent publication on the ancient Near East, this book has extensive illustrations, charts, and maps as well as a good geographical introduction to the region. The time frame of the book extends from 3000 to 323 BC, progressing chronologically by major developments. The first section deals with the rise of city-states, the second with territorial states, and the third with empire building. The book excludes Egypt and is not a definitive history, but it is a good summary work on the subject.

Cleveland, William L. A History of the Modern Middle East. Boulder: Westview, 1994. 503 pp. This book gives a historical overview from the rise of Islam to the signing of the Oslo Accords, but it focuses on the past two centuries of conflict. The book sets up the framework of today’s conflict, explaining it in historical terms. It centers on political events but also integrates social, cultural, and economic development. The book also includes a glossary of terms and an annotated bibliography for further reading. A more difficult read than many other books, it includes detailed information but only assumes a basic knowledge on the part of the reader.

Fromkin, David. Cradle and Crucible. Washington DC: National Geographic, 2002. 255 pp. Including some of the best illustrations and maps of any book on the topic, this book emphasizes the history of the region in the first section, beginning in ancient times. It then moves on to the last century of conflict before addressing the three major religions of the region in the second section. Aimed at an audience with a basic knowledge of the Middle East, it is a good introductory book to the history of the region.

Weatherby, Joseph. The Middle East and North Africa: A Political Primer. New York: Longman, 2002. 244 pp. This book presents the geography, religion, culture, history, and politics of the region to readers who have little or no familiarity with the Middle East or North Africa. It provides good background information to better understand more advanced works on the region. With an emphasis on Iran, Turkey, Egypt, and Israel, it covers each area in the Middle East including forms of government, with two chapters devoted to recent issues.

Johnson, Paul. A History of the Jews. New York: Harper and Row, 1987. 644 pp. This is a well-written and accurate book of Jewish history from Old Testament times to the present. A national bestseller, it covers not only Jewish history but also the impact of Jewish genius and imagination on the world. It was clearly written for an educated general audience.

Dosick, Wayne. Living Judaism. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1995. 385 pp. Rabbi Dosick provides a sensitive, enlightening perspective into Jewish philosophy, theology, rituals, and customs. His personal essays are especially insightful. This is a very helpful book for those who want to understand Judaism and its faith and practices.

Cahill, Thomas. The Gifts of the Jews. New York: Nan A. Talese, 1998. 291 pp. Cahill highlights some crucial Jewish contributions to Western history, recreating a time when the actions of a small band of people had repercussions that are still felt today. This is a popular account of Jewish culture that provides interesting perspectives into the Old Testament and Jewish society.

Blumberg, Arnold. The History of Israel. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1998. 218pp. Blumberg begins with the early history of Jews in the Holy Land, but he focuses on the rise of the modern state of Israel. He covers each aliyah and continues through the mid-1990s, presenting an analytical history that he claims is appropriate for both students and lay people interested in the origins and development of the state.

Hourani, Albert. A History of the Arab Peoples. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1991. 551 pp. Hourani writes the history of the Arabic-speaking parts of the Islamic world, from the rise of Islam to the present day. This work is intended for general readers who wish to learn something about the Arab world, especially for those beginning to study the subject. The book is divided into sections by century groupings with the last two centuries receiving a more detailed focus.

Mansfield, Peter. The Arabs. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1985. 510 pp. In this book, Mansfield uses the first portion to define the Arabs and give a survey history from the death of Mohammad until the present day. The second section addresses individual Arab countries in the Middle East and North Africa, providing specific historic information for those countries as well as more recent issues. The last section of the book addresses Arabs today from both western and Arab perspectives. An easy read, this work appeals to a wide audience of readers.

Ahmed, Akbar S. Islam Today: A Short Introduction to the Muslim World. London: I. B. Tauris, 1999. 253 pp. This work covers several topics including what Islam is, Muhammad’s life, the message of the Qur’an, Sunni and Shi’a divisions, with a much longer section on Muslim history from the early Arab dynasties to the mid-nineteenth century. It also focuses on Muslim nations in contrast to western modernity and Muslims as a minority group in different areas of the world. Written from the perspective of a Muslim, the book does not claim to be purely academic but part travelogue and part history as it extends far beyond the religious sphere of Islam. Appealing to a wide audience, it is appropriate for newcomers to the subject as well as those with some previous background.

Esposito, John L. Islam: The Straight Path. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. 286 pp. This book is accompanied by several good illustrations, and in it Esposito covers several areas of Islam including the basic topics of Muhammad, the Qur’an, and the fundamental beliefs; he also explores modern interpretations of Islam and contemporary politics. This edition gives more attention to global Islam, especially in Asia and the West. Esposito’s goal is to help readers understand the faith and practice of Muslims, making this a good introductory text on Islam.

Fraser, T. G. The Arab-Israeli Conflict. New York: St. Martin’s, 1995. 165 pp. A concise history, this book provides the origins of the conflict prior to World War I and continues through World War II, the Partition, the establishment of the state of Israel, the series of Israeli-Arab wars, and finally the Oslo Accords. It is a good basic book for those beginning their study of the topic, and it has an especially helpful glossary.

Goldscheider, Calvin. The Arab-Israeli Conflict. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2002. 228 pp. This book gives a brief historical overview with a chronology of events. The author presents viewpoints from each side and also addresses both the Palestinian and Jewish diasporas—a unique feature in this book. The second section is filled with firsthand accounts taken from letters and diaries of those who were involved with the conflict, adding some flavor to the times and events. This work assumes that the reader has a good knowledge of the conflict, as it does not spend a lot of time going over basics.

Lesch, Ann M. and Dan Tschirgi. Origins and Development of the Arab-Israeli Conflict. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1998. 191 pp. This book is concise with a brief historical overview, but its main goal is to describe the conflict itself. The role of the United States is addressed as well as major personalities that have been involved. A section of primary documents, a glossary, and an annotated bibliography round out the book, making it a good choice for those just beginning or those who already have some background knowledge of the conflict.

Bickerton, Ian J. and Carla L. Klausner. Arab-Israeli Conflict. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1998. 335 pp. This book, which comes in textbook format, is excellent for several levels of readers: it allows for beginners but also is very informative for those with more in-depth knowledge. The book defines the sides of the conflict and gives detailed historical background beginning with Palestine in the nineteenth century and continuing through the Intifada, which receives its own chapter. Each of the Arab-Israeli wars receives its own chapter, as does the peace process. There are extensive maps and charts, but the book, like most textbooks, is not a fast read.