The First Seminary Teacher

Casey Paul Griffiths

Casey Paul Griffiths, "The First Seminary Teacher" Religious Educator 9, no. 3 (2008): 115–130.

Casey Paul Griffiths (griffithscp@ldsces.com) was a seminary teacher at Alta Seminary in Sandy, Utah when this was written.

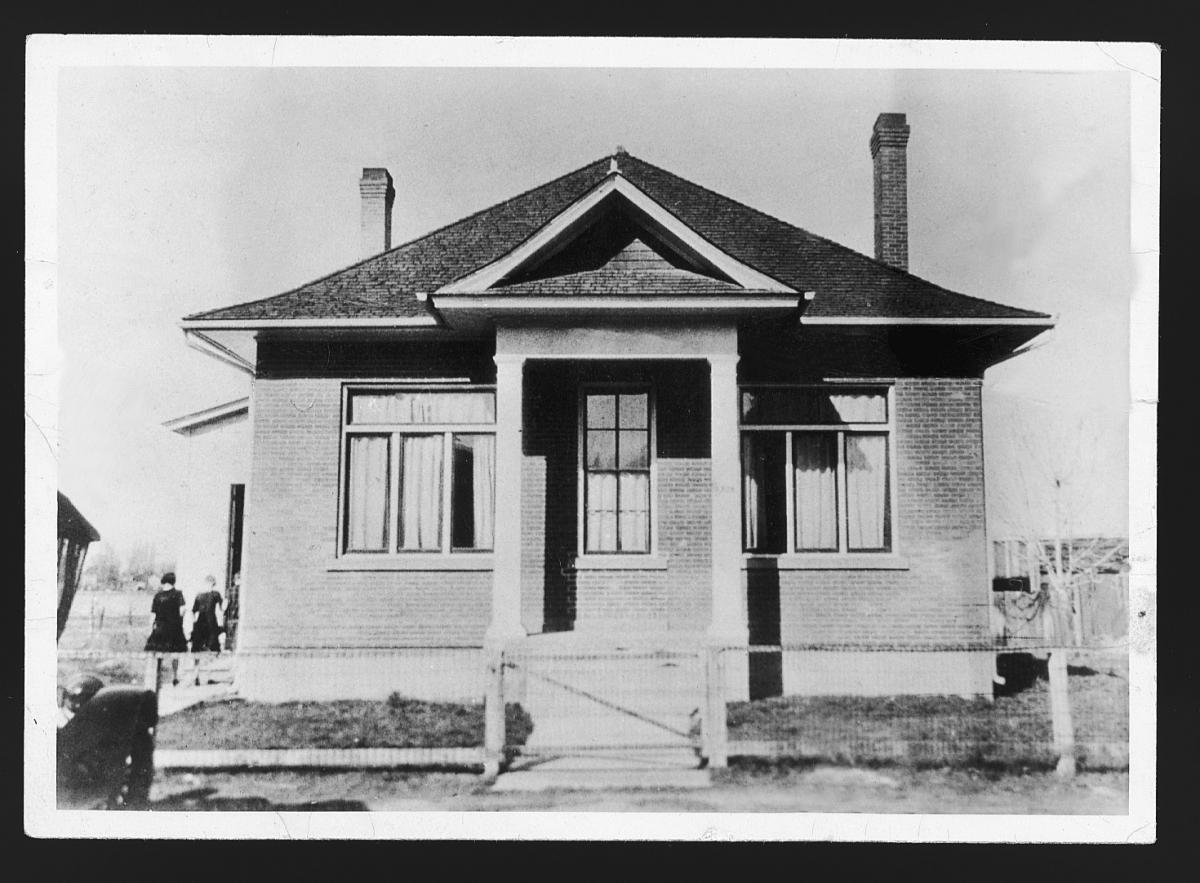

Granite High Seminary Building, 1912. Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Granite High Seminary Building, 1912. Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

When the first released-time seminary program was launched at Granite High School in 1911, it faced a number of challenges. Joseph F. Merrill, the member of the Granite Stake presidency who had first conceived of the program, faced the overwhelming task of building an entirely new form of religious education from scratch. Curriculum, facilities, and the legality of the fledgling program all weighed heavily on his mind. Chief among his concerns was the task of finding the right man to launch the program—the first seminary teacher. Writing to the stake presidency, Merrill gave his qualifications for the position as follows:

May I suggest it is the desire of the presidency of the stake to have a strong young man who is properly qualified to do the work in a most satisfactory manner. By young we do not necessarily mean a teacher who is young in years, but a man who is young in his feelings, who loves young people, who delights in their company, who can command their respect and admiration and exercise a great influence over them. . . . We want a man who is a thorough student, one who will not teach in a perfunctory way, but who will enliven his instructions by a strong, winning personality and give evidence of a thorough understanding of and scholarship in the things he teaches. . . . A teacher is wanted who is a leader and who will be universally regarded as the inferior of no teacher in the high school.[1]

The man ultimately picked for this position was Thomas J. Yates.[2] The following study is an attempt to shed some light on the background and labors of this pioneer of education in the Church.

Thomas J. Yates and the Modern Religious Educator

Thomas J. Yates does not fit the mold of the typical professional religious educator. In fact, Yates shares more in common with the average early-morning seminary teacher than his modern professional counterparts. He was by no means an expert in religion, nor even a career educator. At the time he began his first assignment, Yates was working as an engineer on the Murray power plant. He did not have, nor would he ever have, any kind of professional training in how to teach religion. His stint as the instructor at Granite seminary lasted only one year, after which he was replaced by Guy C. Wilson, a full-time teacher from the Church academy. With no professional training or teaching experience, what did Yates bring to the position? The qualities which won him the job may hopefully be found in any of his current successors: a love of the gospel, a passion for the scriptures, and a willingness to serve at the Lord’s call.

A Faithful Upbringing

Thomas J. Yates was born to Thomas and Elizabeth Yates in 1870. He spent the early years of his life in Scipio, Utah, where his father served as bishop of the local ward. During his adolescence he developed a puckish sense of humor and was involved in many pranks. Every year around Halloween, Thomas and his friends would engage in mischief. A favorite prank consisted of taking apart a neighbor’s wagon, then reassembling it on top of a nearby shed. Some of his more outrageous exploits involved such unsavory activity as tipping over nearby outhouses.[3] But alongside this youthful exuberance there was a deep spirituality developing in young Thomas. He later recalled the first stirrings of testimony as he sat in his Primary classes. He later wrote: “My first testimony was gained while a member of the Primary Association. Through the teachings there and by fasting and prayer the spirit of testimony was received. There was no remarkable demonstration but a positive assurance was given me that the Gospel was true. No doubt has ever entered my mind from that day to this. I have beheld many manifestations of God’s power since; all of which simply add to this childhood testimony.”[4]

At the time of Thomas’s childhood, Scipio was still a part of the frontier, and his reminiscences abound with memories of cowboy adventures. On one excursion to retrieve some stray horses, he was startled to see a bear, only to be further terrified when several Native Americans appeared and began firing their guns at the animal. Assuming he was their real target, Thomas beat a quick retreat out of the area. His father refused to believe such a tall tale. Later that day when several of the Native Americans came to his father’s store to trade a bear skin, Thomas’s father asked them if they had seen a boy on a horse nearby. The Native Americans began laughing and responded that the only evidence of his son’s presence had been a dust trail leading out of the valley. Similar stories of Yates’s adventurous youth fill the pages of his personal writings. It is no stretch of the imagination to picture Thomas regaling his seminary classes with tales of his encounters with bears and Native Americans during the lighter moments of class.[5]

Education and Mission

When Yates was sixteen, he left Scipio to attend Brigham Young Academy in Provo, Utah. The academy was still in its formative stages, meeting in the ZCMI warehouse. Here he benefited from the instruction of Karl G. Maeser, the school’s first principal, and skilled teachers, among them future Apostle James E. Talmage and Benjamin Cluff Jr., who later served as the first president of Brigham Young University. Yates paid tribute to Maeser’s hand in his spiritual development, saying, “Dr. Maeser was one of the greatest spiritual teachers I have ever met. He left a spiritual imprint in most all the students that came under his influence.”[6]

The next few years consisted of intensive studies at the academy, broken up by summers in Scipio working in the family businesses. When he graduated from Brigham Young Academy four years later, Yates, at age twenty, was hired as principal of a school in Deseret, Utah. Yates noted his intimidation at supervising teachers who were much older than he was. He even had several students who were older than he was. Nonetheless, he dove into the assignment with enthusiasm. Within a year he had been given supervisory responsibilities over local schools in Oasis, Hinckley, and Delta, becoming the assistant superintendent for all Millard County schools. Despite these successes, Yates felt a need to continue his schooling. Though a natural teacher, he did not see his professional future as being in education. He returned to the Brigham Young Academy and began preparations to travel to the eastern United States for further education.[7]

During the next year at the academy, Yates fell in love with Lydia Horne, a fellow academy student. They planned to marry in the summer of 1895, after which they would travel to Cornell University, where both would further their education. Yates’s plans were interrupted when he returned to his parents’ home and found a letter issuing a mission call. When his mother asked if he would accept the call despite his educational plans, his career, and his engagement, Yates showed his devotion to the gospel: “I told her there was only one answer; I would go on a mission. She said what about college? I said this is more important. I accept[ed] the call. [The] next morning my answer was on its way to Salt Lake.”[8]

Contrary to the practices of modern missionaries, Yates pressed on with his engagement plans after he received his call. He and Lydia decided to marry before he left on his mission. They were wed on March 20, 1895. After a little over two months of matrimony, Yates left for his mission at the beginning of June the same year. He spent the next three years serving in the Southern States Mission.[9]

He later offered a brief summary of his service. Yates’s experiences offer an intriguing window into missionary service at the turn of the century:

Our only means of travel was walking. We made it our custom in our travels, either in canvassing or going from branch to branch of the church to do a full days work regardless of where we would end the day. When night came we were often long distances from acquaintances, or friends, but we would work to the end of the day without knowledge where or with whom we would stay that night. We had full confidence that the Lord would raise up a friend when we needed it, for our Mission President had promised us He would, and He never failed us. During the thirty seven months of my mission I did not have to sleep out once and during the last thirty months we never paid for food or lodging but went entirely depending upon the Lord.[10]

When Yates returned in 1898, he and Lydia left for their studies at Cornell. Arriving in the East at a time when Latter-day Saint beliefs were still largely misunderstood, and in a place where the Church had yet to establish a strong presence, the young couple saw an opportunity to open doors for their religion. Yates felt his time at Cornell to be an extension of his missionary experience and took it upon himself to share the gospel with his professors and fellow students.[11]

Yates excelled in his studies at Cornell. He also recorded an encounter widely shared in Latter-day Saint history but little associated with his name. At a reception honoring Andrew D. White, the former American ambassador to Russia, White discovered Yates’s Utah background and immediately asked if he was a Mormon. When he replied in the affirmative, White then asked if he could meet with him again and set up an appointment for the following Sunday evening. Yates, bewildered by this invitation, went away wondering if his status at the university was about to be called into question because of his faith. Nevertheless he arrived at the appointed hour the next Sunday, where he recorded the following experience:

Sunday came, and at five o’clock I was ushered into the study of Dr. White. Strangely enough, I learned that the invitation had grown out of a resolution formed several years before in Russia, where, in 1892, he had served as U. S. Foreign Minister.

It was while there that he had become acquainted with Count Leo Tolstoi, the great Russian author, statesman, and philosopher. A warm friendship existed between the two men, and Dr. White often visited Count Tolstoi, who had very decided views about certain social and economic problems.

On one occasion when Dr. White called on Count Tolstoi he was informed that the Count, who among other things taught that every man should wrest from the earth enough food to keep himself and family, was out in the fields plowing, for he practised what he preached. When Tolstoi saw him, he stopped long enough for a greeting, and then stated with characteristic frankness: “I am very busy today, but if you wish to walk beside me while I am plowing, I shall be pleased to talk with you.”

As the two men walked up and down the field, they discussed many subjects, and among these, religion.

“Dr. White,” said Count Tolstoi, “I wish you would tell me about your American religion.”

“We have no state church in America,” replied Dr. White.

“I know that, but what about your American religion?”

Patiently then Dr. White explained to the Count that in America there are many religions, and that each person is free to belong to the particular church in which he is interested.

To this Tolstoi impatiently replied: “I know all of this, but I want to know about the American religion. Catholicism originated in Rome; the Episcopal Church originated in England; the Lutheran Church in Germany, but the Church to which I refer originated in America, and is commonly known as the Mormon Church. What can you tell me of the teachings of the Mormons?”

“Well,” said Dr. White, “I know very little concerning them. They have an unsavory reputation, they practice polygamy, and are very superstitous.”

Then Count Leo Tolstoi, in his honest and stern, but lovable, manner, rebuked the ambassador. “Dr. White, I am greatly surprised and disappointed that a man of your great learning and position should be so ignorant on this important subject. The Mormon people teach the American religion; their principles teach the people not only of Heaven and its attendant glories, but how to live so that their social and economic relations with each other are placed on a sound basis. If the people follow the teachings of this Church, nothing can stop their progress—it will be limitless. There have been great movements started in the past but they have died or been modified before they reached maturity. If Mormonism is able to endure, unmodified, until it reaches the third and fourth generation, it is destined to become the greatest power the world has ever known.”[12]

White said that his greater desire to learn about Mormonism had stemmed from this experience, and Yates stayed into the morning hours answering his questions and teaching the fundamentals of the gospel. Later, as he prepared to depart from Cornell, Yates decided to place some Church books in the school’s library, but was surprised to see that the standard works, along with several other books and pamphlets on Mormonism were already there.

Decades later, Yates would relate this experience in an article published in the Improvement Era, which would later find wide readership when LeGrand Richards included it in his classic missionary treatise, A Marvelous Work and Wonder.[13] Some scholars would later question Yates’s memory on the subject,[14] but the basic facts related in the story are completely consistent, and the tale would become one of the most oft-quoted stories on the potential of Mormonism. Literary critic Harold Bloom would later draw on this experience for the title and central ideas of his book, The American Religion, which was largely a critique of Mormonism.[15]

Innovations in the Granite Stake

Yates graduated from Cornell in 1902 in mechanical engineering and electrical engineering.[16] He and Lydia returned to Utah, and Yates began working for several different power companies. Lydia passed away in 1903, leaving Yates alone to raise two daughters. He remarried the next year to Lily Fairbanks.[17]

During this time, Yates became deeply involved in his work in the Granite Stake, which was a hotbed of innovation in the Church. In the early twentieth century, the Granite Stake, led by President Frank Y. Taylor, developed a number of programs which soon spread throughout the Church. Found among these programs were the establishment of teacher-training classes, systematization of temple work under the direction of the priesthood, and the establishment of a stake amusement committee. All of these programs, while commonplace throughout the Church today, represented pioneering movements in the early part of the century.[18]

The most far-reaching invention of the Granite stake, family home evening, gave birth to perhaps its second-most influential creation, released-time seminary. In 1909 the Granite Stake held a meeting to announce the beginning of a family night program. The meeting drew over two thousand people, among them Church president Joseph F. Smith, who spoke to the group, declaring the inspiration of the stake presidency in launching the program. The program flourished in the Granite Stake, which undoubtedly influenced the First Presidency when they commended it to the rest of the Church in 1915.[19]

During one of these family nights, Joseph F. Merrill, a counselor in the Granite stake presidency, became enamored with the stories his wife, Annie Hyde Merrill, began telling their children from the Bible and the Book of Mormon.[20] In his own words, “her list of these stories were was so long that her husband often marveled at their number, and frequently sat as spellbound as were the children as she skillfully related them.”[21] When Merrill asked his wife where she learned how to teach these stories, she replied it was in James E. Talmage’s class at the Salt Lake Stake Academy. Realizing the academies were rapidly being replaced in Utah by the spread of public high schools, Merrill began to wrestle with the problem of how Latter-day Saint children who attended these schools might receive similar religious instruction. Inspired by his wife’s teaching and partially by seminaries seen during his graduate studies at the University of Chicago, Merrill began forming a bold plan to bring religion to public school students without violating the barriers between church and state.[22]

The plan was simple in its execution. A facility could be built adjacent to Granite High School where students, temporarily released from school custody, could receive religious training. Merrill presented his plan to the presidency and high council of the Granite Stake, the superintendent of Church schools, and the Utah superintendent of public instruction. With all these groups granting approval, Merrill moved ahead. He was granted general supervision over the work and the authority to select a proper teacher, with the stake presidency’s approval. It was under these circumstances that Merrill penned the letter referred to at the beginning of this article, requesting a man who would “be universally regarded as the inferior of no teacher in the high school.”[23] The man selected was Thomas J. Yates.

The Right Man

Why choose Yates? There were several reasons not to, the most important being that Yates was not a professional educator. True, he held some experience from his work in the Church academies in Millard County, but his stint as a teacher there had been twenty years prior and had only lasted one year. Yates also held a full-time position working as an engineer on the construction of the nearby Murray power plant. Finally, a man in his forties, Yates apparently did not fit the bill as the “young man” Merrill was looking for.

Why, then, was Yates chosen? In a word, discipleship. As a member of the Granite Stake high council, Yates was chosen to be the point man in nearly every type of new program the stake launched. The year before his call to serve as the seminary teacher, Yates was called as the chairman of the high council missionary committee. Under his direction, every seventy in the stake was called on a mission, beginning the first organized missionary work performed by a local missionary organization.[24] Merrill may also have been impressed by Yates’s integrity during his schooling in the East. Merrill had also been among the first Latter-day Saint students to venture to the eastern United States seeking higher education. He graduated from Johns Hopkins University in 1899 and knew the dangerous spiritual shoals of higher learning. Seeing how Yates, a fellow scholar, had maintained his faith in the gospel through his education outside the geographic centers of Mormonism may have made a strong impression on Merrill. Lastly, President Taylor saw Yates as a man with the utmost integrity. In a stake conference, Taylor commented, “Brother Yates always reminds me of Joseph who was sold into Egypt, he is a tower of purity and strength.”[25] Yates showed a great willingness to see that plan succeed. As soon as he was informed of his call, he arranged his schedule so he could still work full time in the morning and Saturdays and teach in the afternoon.

Laying the Foundations

Once the approval was given, Yates and Merrill launched headlong into preparations to have the new program ready by the fall. Yates was optimistic about the possibilities, though he recognized the difficulties involved in launching a whole new educational program. “This was a new venture. It had never been tried before. We could see wonderful possibilities if it were successful it would mean a complete change in the Church.”[26]

The first problem they chose to tackle involved the new curriculum. After some discussion, they made the vital decision to center the student’s studies around the standard works, with one class in Old Testament, one centered on the New Testament, and one combining study of the Book of Mormon with a course in Church history. Once the general subjects were selected, Yates and Merrill faced the daunting task of deciding which incidents in each book were most important to learn and which could be taught in an interesting way. The finished product was based roughly on the religion classes taught at the Latter-day Saint academies.[27]

All the while, Merrill and Yates continued to meet with school officials to smooth over any legal concerns and to coordinate the students’ schedules so that released-time seminary would be possible. The high school schedule of a typical student in 1912 consisted of a six-class day. Each student took five classes, then had one period to use for study. Merrill and Yates worked with the school’s principal, James E. Moss, to see if it would be allowed to have students attend religion classes during their free period if their parents requested it. Through several meetings, Yates was able to secure full cooperation from Moss and the faculty of the school. Attending seminary meant the students would have to sacrifice their study time, but Yates felt their sacrifice would be rewarded.[28]

Along with these intellectual and spiritual challenges, a few physical ones arose. Since it was decided to keep the seminary program completely separate from the high school, a new building had to be built. Yates took part in purchasing the land, designing the building, and even overseeing its construction. He later wrote, “It required considerable thought to plan this building. We did not know the number of students to provide for, and therefore the size of the class rooms, or the number of rooms. Provision had to be made for hanging wraps and boots etc. There was no precedent to guide us.”[29] President Taylor borrowed $2,500 from Zion’s Savings Bank in the fall of 1912. The Church general board of education paid interest on the note, and when the Granite Stake could not pay, the board was compelled to pay the principal. The first seminary building was begun only a few weeks before the beginning of school and was not finished until several weeks into the school year. Even when the structure was completed, its accommodations were spartan. The building consisted of four rooms, a cloak room, an office, a small library, and a classroom. Furnishings in the classroom consisted of blackboards, armrest seats, and a stove. There were no lights. There were no regular textbooks other than the scriptures. The seminary’s entire library consisted of a Bible dictionary owned by Yates. The students made their own maps of the Holy Land, North America, South America, Mesopotamia, and Arabia.[30]

The First Class—1912

When the seminary opened in the fall of 1912, seventy students were enrolled. Construction on the seminary building was not complete until the third week of school. Many students who wanted to take seminary could not because by that point in the school year they already had full academic schedules.[31] Yates himself was a making a tremendous sacrifice in time and effort just to get to the building and teach. He would spend every morning working at the Murray power plant and ride his horse to the seminary in time to teach during the last two periods of the day.[32] His salary for the first year was one hundred dollars a month.[33]

What was the first seminary class like? Yates’s own recollections from a 1950 interview provide some insight into how the students’ studies were conducted:

Students were asked to prepare a whole chapter in the Bible and then report to the class. Then the class would discuss it.

No textbooks were used.

The students did not have any form of recreation, there were no parties, no dances, no class affairs or anything in recreation to deviate from the regular pattern of things.

Graduation was a simple procedure; only a diploma was given. Neither did they present any awards.

They had no officers. The students who were allowed to belong to the Seminary considered it a great honor, and they realized that they were starting something new and different in the school system.

All students had to keep a complete notebook on all material given in class. They were checked regularly, and tests were given. The course was a much stricter one then. The seminary classes were much on the order of the Sunday School class. A general opening session, and then the classwork.[34]

Yates’s academic approach to learning was paralleled by a philosophy of friendship and love. He was expected to be not only a teacher but also a guide to show how the gospel could be practically applied in the lives of the students. In this bare-bones environment, the teaching strategy boiled down to little more than a steady diet of the scriptures, seasoned with the friendship of a loving teacher. William E. Berrett, himself an early seminary teacher and later head of the Church Educational system, summed up the strategy of that first crucial year as follows: “There were no texts or outlines as are found in the Seminary System of the Church today. Emphasis was given to teacher-student rapport. ‘Go to the football games with them and do whatever is necessary to show to them the relationship of life and their religion.’ The scriptures were the texts.”[35]

At the end of the school year, President Taylor offered Yates the same position and urged him to continue. However, the strain of traveling back and forth from Murray everyday proved to be too much, and Yates declined. Asked to recommend his own replacement, Yates chose Guy C. Wilson, a professional educator recently moved to Salt Lake from Colonia Juárez, where he had served as principal of the local Church academy. He left Mexico after the 1912–13 revolution forced most of the Mormon colonists out of Mexico, leaving Wilson without a school. His replacement chosen, Yates handed over the reins and went on to other responsibilities in the Granite Stake.

After Granite Seminary—A Lifetime of Devotion

Several of those affiliated with the launch of the Granite Seminary went on to notable futures in Church education. Joseph F. Merrill became the Church commissioner of education in 1928. Serving in this capacity, he oversaw the final closure or transfer of nearly all the remaining Church academies, in favor of the less-expensive seminary program he had developed. He also supervised the transfer of nearly all of the Church-owned junior colleges to state control. These schools were replaced by the institute program, also begun under Merrill’s leadership. Institute, first launched in 1929 at the University of Idaho in Moscow, Idaho, was largely an application of the principles of the seminary program applied on the collegiate level. Merrill also played a crucial role in defending the legality of released-time seminary and credit for biblical studies in the early 1930s.[36] He was ordained an Apostle in 1931, serving with distinction until his death in 1952. Shortly after his call to the Twelve he was called as president of the European Mission, where he served as a mentor to a number of future Church leaders, including future Church President Gordon B. Hinckley.

For Guy C. Wilson, Yates’s replacement, the Granite Seminary was one notable stop in a long and distinguished career in religious education. In fact, Wilson may rightly be called the Church’s first professional religious educator. Prior to the advent of seminary, religion was taught as a part-time subject by other teachers who during the rest of the day may have taught chemistry, arithmetic, or whatever subject was called for. After Granite Seminary, Wilson formed the center of corps of teachers in the Church who were trained and employed solely to teach religion during the school day. As the seminary program expanded, this corps of professional religious educators expanded. Wilson stayed at Granite for two years, moving on in 1915 to become the principal of LDS College in Salt Lake City. Upon the closure of that school in 1930, he transferred to Brigham Young University, becoming the school’s first full-time religion teacher.[37] He and former Brigham Young University president George H. Brimhall effectively functioned as the religion department. The letterhead from the Church department of education in the 1920s and 30s identified Wilson as a “supervisor” over seminary teachers in the system.[38]

The seminary program itself caught on until it became the preferred method of religious education throughout the Church. The system of Church schools which had been functioning since the 1890s was largely dismantled in the 1920s in favor of the less-expensive seminary system. Merrill, Yates, and the other founders of released-time seminary did not found the venture with the intent to replace the academies; it had been merely to provide a supplement form of religious study for those students without an opportunity to attend Church schools. Merrill summed up his own surprise by saying: “We sometimes build better than we know. It was so in this case. [The Granite Seminary’s] promoters had no thought or desire that it should have any influence in closing LDS academies. But if it were successful at Granite they did hope that sooner or later LDS students in other public high schools might have the privilege of attending a seminary. The Church Board of Education must have had that same hope.”[39] Without realizing it at the time, Yates, Merrill, and President Taylor inadvertently gave birth to the system which would revolutionize Church education.

What of Thomas Yates? While his associates moved on to positions of distinction in Church education, he returned to his private life and continued to labor diligently on other Church assignments. In his autobiography, he briefly describes his work with the seminary, but spends the majority of his time detailing other work in the Granite Stake and giving his professional history. His own writings contain no evaluation of that first, critical year of seminary. Other sources indicate that Yates’s struggles during the year were difficult. Speaking of his arrival at the seminary in 1913, Guy Wilson wrote, “Brother Thomas Yates had the previous year conducted classes in the Seminary, but it was felt that a lack of funds and other facilities had prevented him from giving the work a fair trial.”[40]

If Yates felt he hadn’t given the work a “fair trial,” he makes no mention of it in his own writings. Instead, he moved breathlessly into another series of callings he enthusiastically undertook, first as a Sunday School teacher, then as a teacher for the Granite Stake genealogical society. He continued to teach in the Church all his life, later serving as a teacher in Gospel Doctrine class, the Mutual program, and a high priests group instructor.[41] He authored several articles for the Church magazines, including one detailing his encounter with President White at Cornell.[42] He remained an enthusiastic student of the scriptures, especially the Book of Mormon, which he wrote his own concordance for. After forty years of scripture study and research, he wrote and published his only book, A Brief History of the Origin of the Nations, an ambitious work that sought to explain the beginnings of every national and ethnic group on earth and give a brief history of each.[43] Throughout this work Yates’s unquestioning faith in the divinity and truth of the scriptures, both ancient and modern, seems to breathe from the pages.[44] During the last years of his life, Yates worked as a tour guide on Temple Square.[45] At the time of his death in 1958, he had served as a temple worker for ten years.[46]

How did Yates feel about his own legacy? At the commencement ceremony for the Granite Seminary held in 1954, Yates was invited to watch as a statue of his own likeness was unveiled in the very building he had taught in forty-two years earlier. The statue would help to preserve him as an icon of latter-day education for succeeding generations. Even the building he helped design stood as a monument to the work of the Granite Stake for almost eighty years. Undergoing several renovations along the way, it continued to house the Granite Seminary until a more modern structure was completed in 1994.[47] A history completed in honor of the commencement contained Yates’s own sentiments on the legacy he began.

In the olden days, the church dominated the school, and when American freedom was established the pendulum swung to other extreme and the church was eliminated completely from the school. Those responsible for our educational system failed to differentiate between the church and religious education and in excluding the church, they also eliminated religious education.

They failed to realize that moral training and religious education are so interwoven that the exclusion of one carries the other with it.

The seminary is the answer to this question. This institution which originated at the Granite High School has spread its influence throughout our state and into other states. It is destined to become not only national, but a great international institution, for it is supplying that other half to our educational system, which has been neglected until our penitentiaries are being filled with youths who have gone wrong, not because they were inherently bad, but because the moral and spiritual part of their education has been neglected.

Long live the Granite seminary, the “trail blazer” marking the way for youth of all lands into that training that develops character, through moral and religious education.[48]

Within the brief seminary career of Thomas J. Yates, we find several apparent contradictions. He was a product of the Church academies and yet was instrumental in creating the program that would lead to their demise. He was a highly educated man, trained at the finest universities in the nation, yet he demonstrated a simple, unassuming faith in the gospel. He was perhaps the first professional religious educator, yet he was not a professional educator by trade. He launched a program which would bring monumental changes in the way that the Church provides religious education for its youth, yet he never saw it as the crowning achievement of his own Church service; it was just another calling performed faithfully. Today the obscurity of the origins of Church education may mean that the name Thomas Yates is only known to those who have chosen Church education as their profession. Yet Thomas Yates is the ultimate model for those who today are the unsung heroes, and the majority of those who work in the seminary program: the volunteer teachers. Like those volunteer teachers, he sometimes struggled to maintain the balance between his calling as a teacher and his career and family. In the end, his illustrious seminary career lasted only one year, not a lifetime. It is perhaps in the lives of those volunteer teachers who arise early in the morning, teach with little or no financial compensation, and rely on the Spirit and the word to motivate students that the legacy of the first seminary teacher may best be found.

Notes

[1] Joseph F. Merrill, “A New Institution in Religious Education,” Improvement Era, January 1938, 55.

[2] Sadly, Yates has received little recognition for this achievement. The last article published in a Church magazine to describe the history of seminary lists many details of the first seminary program but names Yates’s successor, Guy C. Wilson, as the first seminary teacher (see Janet Thomas, “A Century of Seminary,” New Era, January 2000, 26).

[3] Thomas J. Yates, Autobiography and Biography of Thomas J. Yates, Church Archives, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, 127.

[4] Yates, Autobiography, 3.

[5] Yates, Autobiography, 10.

[6] Yates, Autobiography, 14–15.

[7] Yates, Autobiography, 17–18.

[8] Yates, Autobiography, 45.

[9] Yates, Autobiography, 46.

[10] Yates, Autobiography, 57. Original punctuation preserved.

[11] Yates, Autobiography, 60.

[12] Thomas J. Yates, “Count Tolstoi and the ‘American Religion,’” Improvement Era, February 1939, 94.

[13] See LeGrand Richards, A Marvelous Work and Wonder (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1950), 413–14.

[14] See Leland A. Fetzer, “Tolstoy and Mormonsim,” Dialogue 6, no. 1 (Spring 1971): 13–29.

[15] See Harold Bloom, The American Religion: Emergence of the Post-Christian Nation (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992).

[16] Yates, Autobiography, 89.

[17] Yates, Autobiography, 5.

[18] An Expression of Appreciation to President Frank Y. Taylor, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

[19] Richard O. Cowan, The Church in the Twentieth Century (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1985), 322–323

[20] William E. Berrett, A Miracle in Weekday Religious Education (Salt Lake City: Salt Lake Printing Center, 1988), 28.

[21] Merrill, “A New Institution,” 12.

[22] Cowan, The Church in the Twentieth Century, 89.

[23] Merrill, “A New Institution,” 12.

[24] Yates, Autobiography, 61.

[25] Yates, Autobiography, 42.

[26] Yates, Autobiography, 79.

[27] Merrill, “A New Institution,” 55–56.

[28] Berrett, A Miracle, 30; Yates, Autobiography, 80.

[29] Yates, Autobiography, 80.

[30] Charles Coleman and Dwight Jones, comp., History of Granite Seminary, unpublished manuscript, 1933, Church Archives.

[31] Yates, Autobiography, 80.

[32] “New Building Dedicated at Granite, the Oldest Seminary in the Church,” Church News, September 10, 1994.

[33] Ward H. Magleby, “Granite Seminary, 1912,” Impact 1, no. 2 (Winter 1968): 9.

[34] LeRoi B. Groberg, as cited in Magleby, “Granite Seminary, 1912,” 9, 15.

[35] Merrill Briggs, A History of the Development of the Curriculum of the Seminaries of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, unpublished manuscript, Special Collections, BYU.

[36] For an overview of Merrill’s service to Church education, see Casey P. Griffiths, “Joseph F. Merrill: Latter-day Saint Commissioner of Education, 1928–1933,” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2007).

[37] Richard O. Cowan, The Latter-day Saint Century (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1999), 86.

[38] “Joseph F. Merrill to George H. Brimhall, Salt Lake City, Nov. 26, 1928, Box 33, Folder 4, George A. Brimhall Collection, UA 1092, Special Collections, BYU.

[39] Merrill, “A New Institution,” 55.

[40] Charles Coleman and Dwight Jones, comp., History of Granite Seminary, 1933, Church Archives, 32.

[41] Yates, Autobiography, 81–83.

[42] Yates, “Count Tolstoi and the ‘American Religion,’” 94.

[43] Yates, Autobiography, 131.

[44] See Thomas J. Yates, Origin and Brief History of Nations (Salt Lake City: Paragon Press, 1956).

[45] Gordon B. Hinckley, “Early Teacher Taught Many Noted Youths,” Deseret News, September 8, 1948.

[46] Yates, Autobiography, 132.

[47] “New Building Dedicated at Granite.”

[48] Groberg, as cited in Magleby, “Granite Seminary, 1912,” 9.