The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Roundtable Discussion Celebrating the 60th Anniversary of Their Discovery, Part 1

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, Donald W. Parry, Dana M. Pike, and David Rolph Seely

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, Donald W. Parry, Dana M. Pike, and David Rolph Seely, “The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Roundtable Discussion Celebrating the 60th Anniversary of Their Discovery, Part 1,” Religious Educator 8, no. 3 (2007): 127–146.

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, Donald W. Parry, Dana M. Pike, and David Rolph Seely

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel (holzapfel@byu.edu) was a professor of Church history and the manager and director of the Religious Studies Center when this was written.

Donald W. Parry (donald_parry@byu.edu) was a professor of Hebrew Bible studies at Brigham Young University when this was written.

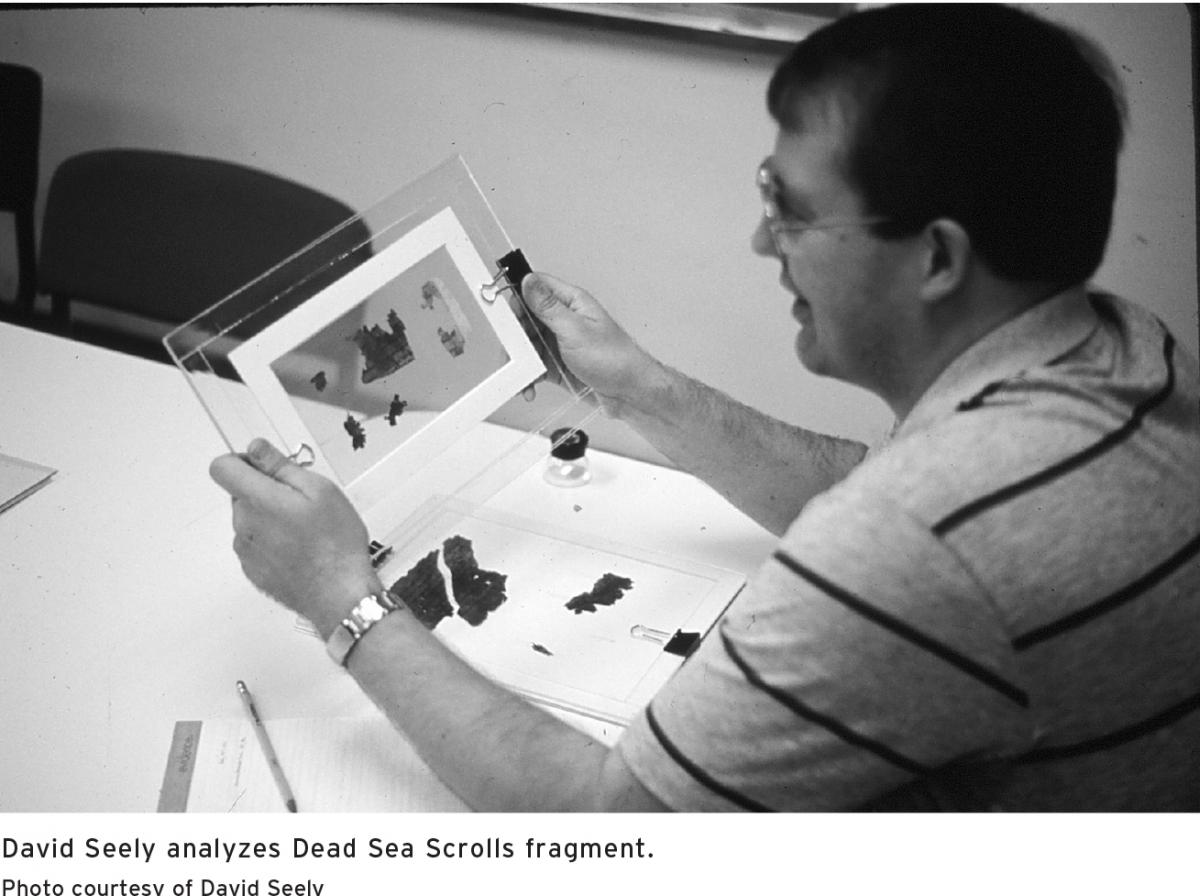

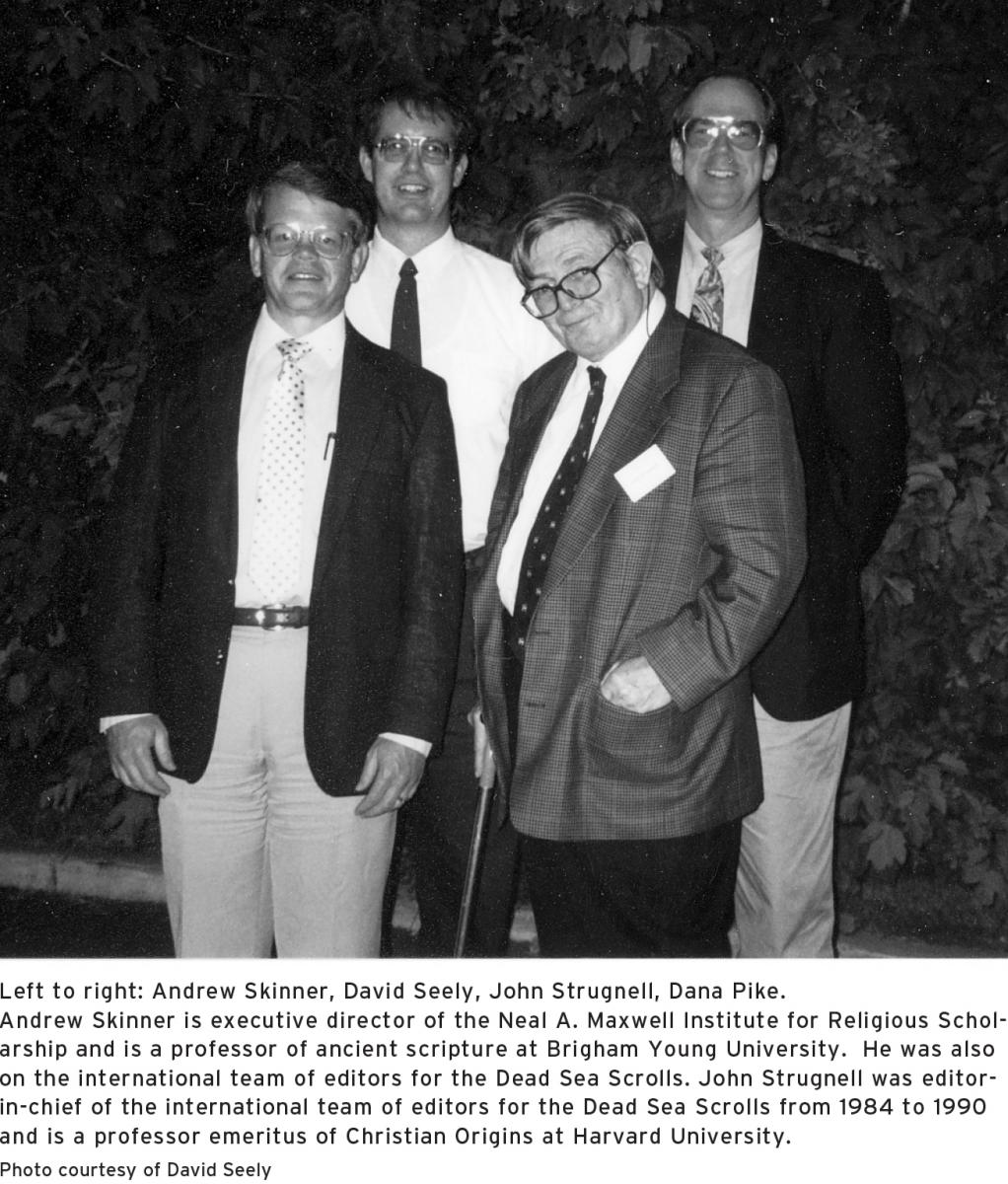

Dana M. Pike (dana_pike@byu.edu) and David Rolph Seely (david_seely@byu.edu) were professors of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University when this was written as well as members of the international team of translators of the Dead Sea Scrolls who have contributed to the official scroll publication series, Discoveries in the Judaean Desert, published by Oxford University Press.

Donald W. Parry researching the Great Isaiah Scroll in the scrollery of the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem. Photo courtesy of Donald W. Parry.

Donald W. Parry researching the Great Isaiah Scroll in the scrollery of the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem. Photo courtesy of Donald W. Parry.

Holzapfel: Since their discovery in the Judaean desert sixty years ago, the Dead Sea Scrolls have both enlightened and perplexed scholars and laymen alike. Between 1947 and 1956, Bedouins and archaeologists found around 930 fragmented documents near the archaeological site called “Qumran,” about ten miles south of Jericho and thirteen miles east of Jerusalem. Each composition is numbered by the cave where it was found and then named according to the scroll’s contents; for example, scroll 11QTemple is from Cave 11 in Qumran and is called the Temple Scroll, while 4Q252 is from Cave 4 in Qumran and is composition number 252. Most of the scrolls were produced in Hebrew or Aramaic between 250 BC and AD 68. The scrolls include books from the Old Testament (except the book of Esther), the apocrypha and other contemporary Jewish pseudepigraphal texts, and sectarian texts unique to the Qumran community. Additionally, scholars found an ancient cemetery near the archaeological ruins of Qumran that raises questions about the cemetery’s relationship to the scrolls, caves, and the archaeological site.

Because misconceptions about the contents and spiritual significance of the Dead Sea Scrolls have sprung up over the years and have spread among Christians, including some Latter-day Saints, I invited three colleagues who have been involved in the Dead Sea Scrolls research to join me in a roundtable discussion to answer some important questions regarding the Dead Sea Scrolls, placing the scrolls in context after sixty years of scholarly and popular discussions regarding the importance of these ancient texts. Because of the many questions that surround the Dead Sea Scrolls, this discussion has been divided into two parts to give an opportunity for these three scholars to share their knowledge. This is the first article in a two-part series on the Dead Sea Scrolls, focusing mainly on those texts discovered around Qumran. The second part will be published in the next issue of the Religious Educator. We have added suggested readings at the end of this article for further study on the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Creation of the Dead Sea Scrolls

Holzapfel: What are the general theories on who collected or copied the Dead Sea Scrolls and when?

Pike: The dominant theory is that the scrolls were collected and copied by a group of Jews called Essenes. However, the Essenes did not compose the contents of most of the scrolls. Some scrolls were brought to the site, some were copied at the site, and some may have been composed at the site. But composition at the site was probably limited. Thus, the collection of scrolls probably came from a number of places, ending up at Qumran during the last three centuries BC and the first century AD.

Parry: The earliest scroll (4QSamb) dates to about 250 BC, and the latest scroll dates to about AD 67–70. Regarding the scrolls’ authorship, Magen Broshi and Hanan Eshel have collected twelve different opinions and theories about who lived at Qumran.[1] Some of those theories also pertain to who owned the scrolls.

I am currently studying controversies and puzzles in the Dead Sea Scrolls, in which I have identified about twenty-five controversies and questions that have remained unresolved among scholars: Who owned the scrolls? Did the Essenes own the scrolls? Did the Pharisees own the Scrolls? Did the Sadducees, or did another group? These are some very important questions that we face.

Site of the Dead Sea Scrolls

Holzapfel: What is the general consensus about the scrolls’ relationship to the caves and the nearby graves and ruins?

Pike: The general consensus is that the Qumran ruins and the scrolls are connected. Every few years something comes up—some new maverick proposition that somehow the scrolls and the site are not connected, such as the suggestion that the site was a fort or a villa. It is true that scroll fragments were found only in the caves near the ruins, not in the ruins themselves. But the majority of scholars have believed for the last fifty years or more that the scrolls and the site are integrally connected. This is primarily because the pottery types found in the caves, such as the jars in which some of the scrolls were found, match the pottery types found in the ruins. Since some of these types are not found elsewhere in Israel, it strongly suggests a link between those who lived at Qumran and those who deposited the scrolls in the caves. And some of the caves are quite close to the site, so the proximity argues in favor of a connection. It is also important to remember that the site was burned and destroyed around AD 68, so it is not surprising that no scroll fragments were found in the Qumran ruins. Very little organic material of any sort was found there.

Seely: Excavating the graves has been a problem because of a religious law in Israel, but some of these graves appear to be later Bedouin graves.

Parry: We have such a small sampling of the graves that have been uncovered and excavated that it is hard to make any solid statements about who was buried in the graves: what sex, what age group, and so on.

Holzapfel: Did the Essenes inhabit the ruins and use the caves?

Parry: That is the consensus among scholars.

Seely: The people who lived at the site had something do to with at least some of the scrolls.

Holzapfel: Was Qumran an administrative center with people living in caves, tents, and huts outside, or did people live in Qumran as well?

Seely: Scholars disagree about exactly how they are related, but Qumran seems to be a satellite community of the greater Essene community spread throughout Israel. First archaeologists thought that everyone lived in this big center, but the current view now is that people actually lived in caves around it and used the center for communal meetings, where they would write the scrolls and have their communal meal. I think the people probably lived in the caves or in tents around the area. The consensus is that this community at Qumran apparently demanded some sort of celibacy; it was not like other family-oriented Essene communities that existed elsewhere in bigger cities.

History of the Essenes

Holzapfel: If they were Essenes, we know of them in other sources: Josephus, Pliny the Elder, and Philo. Some of the Dead Sea Scrolls represent the first hint of the Essenes’ own writings: writings they produced and collected that talked about them. In other words, is there nothing else that can give us an insider’s view of who the Essenes were or what they thought?

Seely: Other than Josephus, Pliny, and Philo and the scrolls themselves, there are no other sources. All we know is that sometime in the second century BC, the Essene movement was started by someone called the Teacher of Righteousness.

Pike: At least some of the Qumran documents—such as the Rule of the Community (1QS); the War Scroll (1QM); the Thanksgiving Hymns (1QH); the pesherim, or commentaries on prophetic books; and probably the Temple Scroll (11QTemple)—these so-called sectarian texts tell us about some of the distinctive beliefs and practices of the Qumran community. For example, they believed, based on their interpretation of prophecy in the Hebrew Bible, that they were living in the evil period of the last days—the “end of days”—and that God would shortly destroy evil from the earth. They believed that they were the chosen ones of God with whom He had renewed His covenant and that there would be a great and decisive battle between the “sons of lights,” as they termed themselves, and the “sons of darkness,” as all others were called—both wicked Jews as well as Gentiles. Some of the sectarian scrolls mention the coming of two messiahs, a priestly one and a royal one. Unique among Jews of their era, the Qumran community believed in the doctrine of determinism, or predestination. They had a particular initiation process for anyone wanting to join their group by having a communal meal, referred to in one passage as “the pure meal of the saints.”

These sectarian scrolls thus help us see not only how the Qumran community was connected to the larger world of Judaism at the time but also what made them distinct. However, we do not clearly understand the relationship between these Qumran Essenes and the Essenes who had families and lived throughout the land. The so-called Damascus Document at one point provides regulations for those living in “towns” and “camps.” These are distinct from those who lived at Qumran, and many of the regulations governing them were different.

The reality is that just as there were different major factions within Judaism at the turn of the era, such as the Pharisees, Sadducees, and Essenes, there were also other, smaller factions as well, and there were further subgroups within many of these factions. And as seems to be the case, many Jewish people of the day were oriented toward one or another of these groups or subgroups but were not necessarily “card-carrying members” of any one group. Most people believe that the Qumran community represents one particular group or branch of Essenes. I consider them to have been an extradevoted Essene supersect.

Holzapfel: Do the Essenes appear in the New Testament? Can we say that a passage is probably Essene or that it refers to an Essene belief?

Pike: The standard example that I always cite is Matthew 5:43–44. In this passage, Jesus says, “Ye have heard that it hath been said, Thou shalt love thy neighbour, and hate thine enemy. But I say unto you, Love your enemies.” Jesus is somehow responding to and contradicting what appears to have been a strongly held belief unique to the Essenes, or at least unique to those at Qumran. This idea of hating one’s enemies is not attested in the Hebrew scriptures or other Jewish writings but is clearly taught in several different passages in texts that appear to have been unique to the Qumran community and may have been accepted by the wider Essene group in general. Beyond this there is not much that is Essene in the New Testament, but there are some very interesting parallels between certain Qumran and New Testament texts.

Seely: One of these parallels is found in the Qumran and Christian interpretations of the fulfillment of the prophecy in Isaiah 40:3: “The voice of him that crieth in the wilderness, Prepare ye the way of the Lord.” The Gospel writers teach that “the voice of him that crieth in the wilderness” is John the Baptist in the wilderness (see Matthew 3:3; Mark 1:3; Luke 3:4; John 1:23), preparing the way for the coming of the Messiah. In the Rule of the Community, a sectarian text from Qumran, it says about the Community, “They shall separate from the session of perverse men to go to the wilderness, there to prepare the way of truth, as it is written, ‘In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord, make straight in the desert a highway for our God’” (Rule of the Community 8.12–16). They both agreed, then, that the way of the Lord would be prepared in the wilderness.

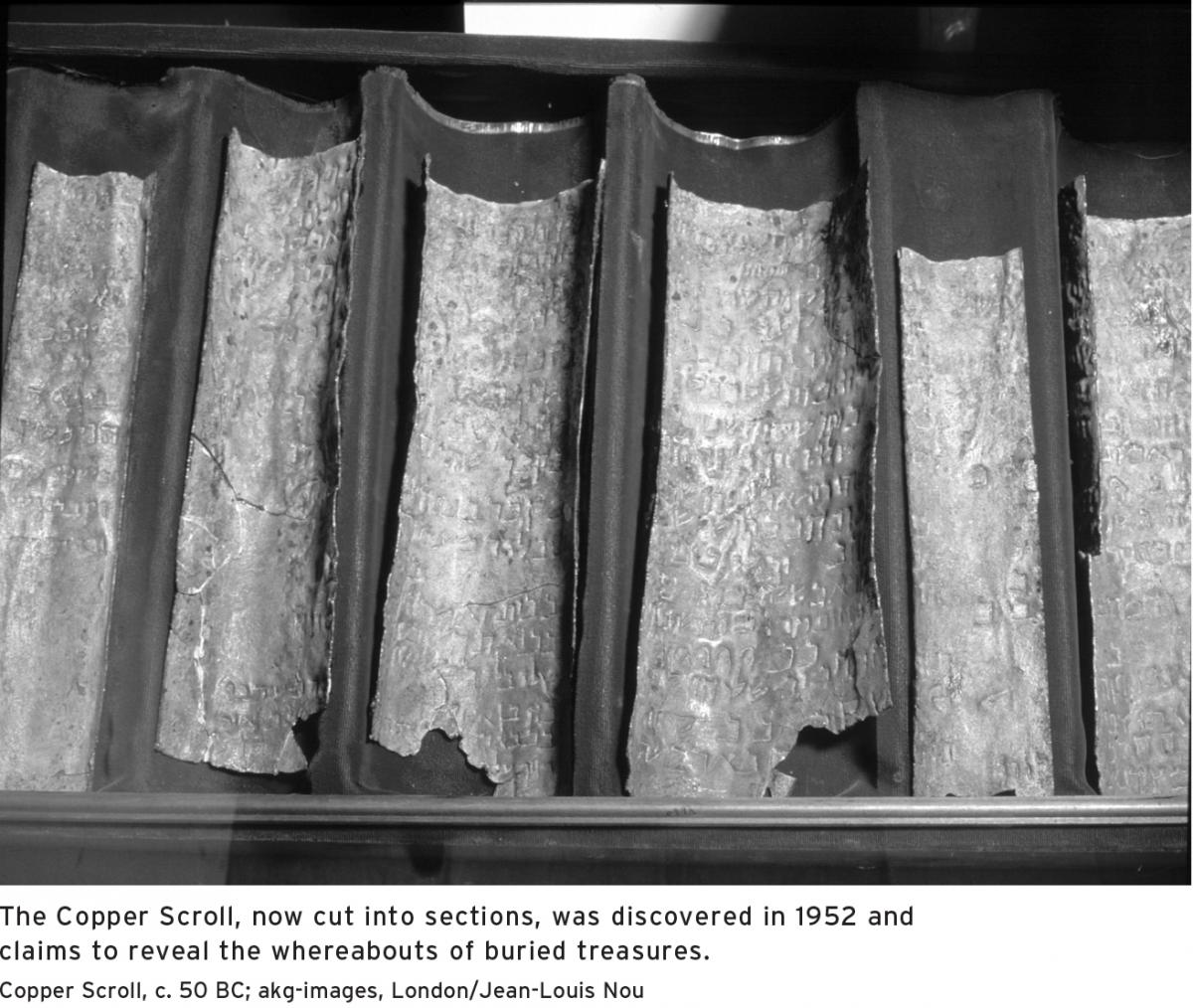

Treasure of the Copper Scroll

Holzapfel: Let us turn our attention to the Copper Scroll (3QTreasure). Because it is metal, it has captured the attention of many Latter-day Saints. What is the significance of the text? What is the controversy? Is there a question about the translation of the Copper Scroll?

Parry: The Copper Scroll lists sixty-four treasure deposits, and there is absolutely a question about its translation. In 1998, I attended a conference in Manchester, England, the place where the scroll was cut into pieces several years ago. During the conference we discussed the Copper Scroll for three days. Just that scroll. Our biggest question was, “Is the copper scroll a genuine composition, or is it fraudulent work?” The scholars at the conference voted on this issue, and the consensus was that it is a genuine composition. It is a genuine treasure map, so to speak.

But there are other questions. For instance, the Hebrew on the scroll is of questionable quality. We think the Hebrew is questionable because it was written on copper. The people who prepared the scroll engraved letters on it, but this is a very difficult process.

Holzapfel: Have the readings been basically similar? Are the differences just in some nuances?

Parry: Many scholars believe that the Copper Scroll represents the temple treasure from the second temple, or Herod’s Temple. The treasury was quite large and administered by seven priests who were appointed to be treasurers.

Seely: One of the controversies is, is it real treasure, and if so, where is it? Most of the places described on the scroll are so obscure that we cannot find them. Some people think they really do know where a couple of the places are. None of the treasure has been found, so if the scroll is truly about treasure, it is very possible that someone has already found it. Vendyl Jones caused a fair amount of destruction of geographical landmarks and caves in that area over the last twenty years by looking for the treasure. I think Jones was finally stopped by the Israel Antiquities Authority. His followers did find a vial of what they called balsam oil.

Parry: I believe that Jones also found some incense, did he not?

Seely: Or what looked like incense—it is somewhat disputed. This treasure is a serious issue, and people really have been looking for it. They really have some strong opinions about this.

Also, a lot of scholars do not consider the Copper Scroll to be a scroll. They consider it a plaque that was rolled up. Rolling it up actually started ruining it. So to call it a scroll is a little misleading.

Parry: Yes, it is a plaque or a plate.

Seely: It was not common for people to write on metal scrolls. It was rolled up for the sake of depositing.

Parry: I think that this scroll has interested Latter-day Saints because it is written on metal.

Pike: So, for Latter-day Saints, did people write on metal in antiquity? Yes, but we have examples that are closer to the time of Nephi and Lehi than the Copper Scroll from Qumran Cave 3.

Parry: And that are also scriptural, such as a very small, seventh-century BC silver scroll found in west Jerusalem that contains Numbers 6:24–26.

Pike: The Copper Scroll dates to five or six centuries after Nephi’s time. In my mind the scroll is a curiosity. I do not think that it was connected with the Qumran community; it just ended up in a cave with some other things that were connected to the Qumran community. But not everybody shares that opinion. Either way, there are better examples of records on metal that are closer to the time of Nephi than is the Copper Scroll, if that is the connection that people are interested in.

The Bible in the Dead Sea Scrolls

Holzapfel: We talked a little about some of the so-called sectarian texts that were found, but we know that all the books of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) except Esther are attested at least once, and in some cases many copies are preserved of what were considered the more important biblical books. What do the scrolls teach us about the ancient Bible, either the Old or New Testament?

Pike: There are no remains of New Testament books found in the Qumran caves, despite some claims a few years ago that some New Testament passages were preserved on small fragments from Cave 7.

Parry: The scrolls have provoked new questions about what the biblical canon looked like in antiquity. Depending on their religious backgrounds, some scholars believe that the Qumran canon was an open canon that included books beyond what is in the present Hebrew Bible, or Old Testament, while others say that those who owned the scrolls possessed the same Hebrew Bible that we have now. By way of example, some scholars attribute canonical or religious authority to the Temple Scroll. Yigael Yadin, B. Z. Wacholder, and Hartmut Stegemann have all argued that the Temple Scroll was a text that held religious authority. I am talking in general terms here because we could talk the whole time about just the canon or what the book of Psalms or some other biblical book looked like.

Holzapfel: The Dead Sea Scrolls seem to represent a remarkably creative period. These people could even have two different versions of the same text. In other words, were they not as firm in fixing a text? Could they live comfortably with two different readings?

Parry: According to scholars, the biblical text was quite fluid at that time. Take one of the Dead Sea Scrolls’ book of Samuel (4QSama), for example. It has almost five hundred variant readings different from the Masoretic text, or Septuagint. Scholars disagree about whether the variations are major or minor, but some are more or less theological. The large number is even more significant when you consider that only 10 percent of this particular book of Samuel is extant. Samuel, however, is exceptional with its many variants. Most biblical books are very close to the Bible from which came the King James Version.

Holzapfel: Is the multi-attestation of some biblical texts significant? Do more copies of a certain text suggest that it was more important to those who owned the scrolls?

Pike: Today we are used to having all of our scriptures under one or two covers. The Qumran biblical texts demonstrate that the practice in that day, for very practical reasons, was to copy the text of only one or two of the longer biblical books on a scroll. So while several shorter books would be copied onto one scroll, the book of Isaiah, for example, required a scroll about twenty-three feet long all by itself, as indicated by the nearly complete Isaiah scroll from Cave 1 (1QIsaa). Another example is a scroll that contains only Leviticus and Numbers (4QLev-Numa). Therefore it was more practical for them to copy and study those biblical texts that were of greatest interest. And we think that there is a correlation between the multiple copies of certain biblical books attested at Qumran and the importance the content of these books had for those people. Most people today do not sit down and read Chronicles or Ecclesiastes over and over. So it is easier to appreciate why there were multiple copies of certain books when we know that only one or a few biblical books were on one scroll and when we appreciate what it was that the community considered to be most important in the biblical books.

Seely: Related to that, the importance of these books can also be measured by the number of times they are quoted in significant sectarian documents. I think that the texts that are attested in multiple copies are cited more. I know it is true for Isaiah and Psalms.

Parry: Yes, and Deuteronomy. Isaiah, Psalms, and Deuteronomy are also the three most frequently cited books in the New Testament.

Pike: And that says a lot about the nature of the Qumran community. They believed themselves to be true Israel, the people of the renewed covenant, and thought the prophecies about Israel were going to be fulfilled through them in their day, with the coming of the Messiah or Messiahs. And so, as Don mentioned, the three books of the Hebrew Bible best attested at Qumran (and in the New Testament) are Psalms, with the remains of thirty-six copies found; Deuteronomy, with the remains of thirty copies; and Isaiah, with the remains of twenty-one copies. It is no surprise that all three of these books contain important messianic texts.

Holzapfel: As we have already noted, the only book among our current Old Testament that is not found among the Dead Sea Scrolls is the book of Esther. Should we conclude that these people did not accept Esther as part of their canon, or is it a fluke that we did not find it among the fragments?

Parry: In my opinion it is a fluke. Some opine that the book of Esther was not in the collection of texts because it does not mention a name of God anywhere in the text or that its story lacked significance to those who owned the scrolls. But I believe the Esther scroll was probably accidentally destroyed through time. Compare it to the scroll of Samuel, which was originally about fifty-five feet long. One of the copies of Samuel discovered in Cave 4 now survives only in a few small fragments. Since the Esther scroll was much smaller than Samuel, I suppose that the Esther text could have been destroyed over a two-thousand-year period.

Seely: I tend to agree with you. There is a scholarly argument based on the fact that in all the sectarian texts at Qumran there is no mention of Purim, the celebration of Esther delivering the Jews from Haman’s plot. Not celebrating Purim is probably significant.

Pike: If they did not celebrate Purim, then they would have been less inclined to read Esther.

Seely: Then it might indicate a bias against the book of Esther. We did find some texts that refer to Esther, so they were aware of the biblical book of Esther. I tend to agree with Don that the book of Esther may have been destroyed, just as Ezra and Nehemiah are only recognized in the scrolls by one tiny piece of evidence. Technically, Nehemiah is not represented at all. In the scrolls, Ezra and Nehemiah are in one book.

Pike: I think that it is quite possible that a copy of Esther was originally there, but we cannot be sure. Since we have found at Qumran the fragmentary remains of only one copy of the biblical books of Chronicles and Ezra/

Judaism in the Dead Sea Scrolls

Holzapfel: What do we now know about first-century Judaism that we would not have known before the discovery of these ancient texts?

Seely: We have untouched first-century sources on a movement of Judaism. I say “untouched” because almost everything else came through the Rabbinic tradition, which was not even written down for hundreds of years but which was then edited and recorded by Jews with somewhat different beliefs. So the Dead Sea Scrolls are primary source materials from that period. From the Qumran we now have an instant first-century attestation of what Judaism was like in Israel at the time of the New Testament.

Holzapfel: What information about ancient Judaism do the scrolls contribute?

Parry: We have so many more texts that were previously unknown to the world, such as the Temple Scroll, the War Scroll, and a copy of a composition called the Beatitudes, different from what was given on the Sermon on the Mount. We also know much more about the Hebrew and Aramaic languages. We have scores of previously unattested words from that period that help us to better understand biblical and Mishnaic Hebrew. We know much more about a number of fields and topics. For example, a brand new field that has recently opened up in Dead Sea Scrolls studies is corpus linguistics, in which we use a computer database to study languages and texts. We also know much more about the coming forth of the Hebrew Bible—scribal conventions and scribal approaches. We know what an ancient scroll looks like. We know what the Bible looks like from this time period.

Seely: In rabbinic Judaism the liturgical prayers were not written down before the ninth century AD. Therefore, before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls we did not have any examples of Jewish prayer besides those few scattered in the apocryphal and pseudepigraphical writings. In the Dead Sea Scrolls, we have numerous ancient Jewish prayers that give us a real glimpse into Jewish spirituality and into the origins of some of the prayers that are attested later in the Rabbinic prayer book. We now know that they worshiped with tefillin (phylacteries) one hundred years before Christ. We just couldn’t know that without these scrolls.

Parry: In addition, the scrolls present us with a greater view of the variety of religious beliefs and practices that existed in the first century AD—well beyond what we thought we knew before the discovery of the scrolls. We are also able to understand how Jewish groups interpreted the biblical texts—what they considered to be holy writings and how they applied it to their situations, their lives, and their time period. The scrolls present us with these insights and much more.

Holzapfel: Many people view Judaism as a homogenous religion during the first century AD. Does the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls smash that assumption?

Pike: If we understand what the scrolls have to say, yes. We know that there were many different factions during this time, including the Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes, and other smaller groups. Most Jews of the period identified with a certain group, but they were not necessarily full members of the group. People now talk about Judaisms (plural) during the period prior to the destruction of the Temple in AD 70.

Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls

Holzapfel: How do the Dead Sea Scrolls contribute to our understanding of the historical context of the rise of Christianity that we would not have known before their discovery?

Parry: We can see what the Bible looked like at the time of Jesus Christ. We can ask, perhaps, about the Isaiah scroll that Jesus read from in the synagogue of Nazareth (see Luke 4:16–20). What did it look like? How long was it? How were the chapters written? Then we can look at the Great Isaiah Scroll, for instance, and determine what a biblical scroll looked like at the time of Jesus and His Apostles. The Great Isaiah Scroll was twenty-three feet six inches long; it lacked verses and chapters. It was written in Hebrew without vowels, without punctuation, without capitalization of any Hebrew characters. How did Jesus locate the reference that we now call Isaiah 61:1–2? He had to find it by context or some other means, for He couldn’t go to the chapter and verse.

Pike: He knew His scriptures!

Parry: Yes, He knew His scriptures in a remarkable way. Knowing about these scrolls or scriptural books teaches us much about Jesus Christ’s great knowledge of the scriptures.

Seely: The bigger mystery worth considering is why, when the people of Qumran were so close geographically to Christians for thirty years, they do not seem to have mentioned each other.

Holzapfel: Perhaps because Christianity did not become a dominant missionary project until after these people died in the first Roman-Jewish War? Even the Pharisees did not mention the Jesus movement until much later.

Pike: Well, the early chapters in the book of Acts indicate there was quite a bit of missionary activity going on in the land of Israel in the several years just after Jesus’s Resurrection. I have always supposed the reason for these groups not mentioning each other is a matter of focus and distribution. These texts were for internal use, meaning for members of the group. They focus on what is distinctive about the group that produced and accepted them, and only by implication do they illustrate how the group that accepts them is different from other groups. Also, none of the Qumran sectarian texts or early Christian texts were produced and disseminated for public consumption. For example, the synoptic Gospel accounts, which no doubt helped introduce people to Jesus and His message, were not sold at the corner store. They were intended, in this example, to be used by Christians to teach others about Christ, as well as for Christians to reinforce their own understanding of and commitment to Christ.

John the Baptist and the People of Qumran

Holzapfel: There has been some speculation that John the Baptist had a relationship with or was somehow influenced by the people at Qumran. What are scholars saying about John and Qumran today?

Parry: Stephen Pfann gave a lecture here on campus in 1996 on the question “Was John the Baptist associated with the group who owned the scrolls?” His presentation focused on John and baptism as compared and contrasted with the Essenes’ view of what Pfann calls the “Essene Renewal Ceremony.” Pfann concludes that, although there are definitely similarities between the Christian baptism and the Essene ritual immersion, there are also some key differences.

Pike: On this point, I agree with Pfann. But I think it is safe to say that many scholars, probably most scholars, think that John did have an organic connection with the Qumran community and then broke away from them and started his own movement. At the official Israeli national park site at Qumran, you can watch a movie suggesting that John learned his baptizing technique there. In my mind, I imagine that John was familiar with the community, maybe even visited there. However, it has been pointed out that the people at Qumran had separated themselves from Jerusalem, whereas John had people coming from Jerusalem to him and he talked with crowds (see Matthew 3:5–12). There are enough significant differences for me to confidently say that John did not study or learn his craft at Qumran—although many scholars would say that he did. One of these differences, from a Latter-day Saint perspective, is that the ongoing ritual immersions that were taking place at Qumran were different from the one-time ordinance of baptism that John was performing with legitimate priesthood authority.

Seely: John was in the same area as the Dead Sea Scrolls writers; that’s always worth noting. Israel is a much smaller country than most people think. However, a fair amount of angst has built up over the fact that John’s baptisms were different from those happening in Qumran.

Holzapfel: True, John was physically immersing other people, whereas at Qumran they immersed themselves.

Seely: Also, John performed baptisms for repentance, while in Qumran immersion was an important ritual washing.

Pike: But a passage in the Rule of the Community (1QS 3:4–6) implies that ritual washings were of no effect if one’s heart was not right with God, so the washing did have spiritual meaning.

Jesus and the People of Qumran

Holzapfel: What is the general consensus today about Jesus’s association or contact with the Essenes? What issues are still unresolved?

Seely: The simple issue is that the New Testament gives the impression that all of Israel is flocking to Jesus, so what we picture is probably exaggerated. In reality, Jesus did not have a huge impact on the Essenes, at least not that they mentioned. And I do not know if another specific mention of the Essenes exists in the New Testament besides the passage that we quoted. However, the reason becomes more clear when we see that the Essenes believed in about 70 percent of standard Judaism. Therefore, the New Testament mentions many beliefs and attitudes common to the Essenes and to many other Jewish groups. The Essenes are just not always distinctive.

Parry: I see no evidence that Jesus was affiliated with the Essenes or with the Qumran community, even though some have argued that perhaps He was.

Pike: I concur. A number of sensational theories have been published, all without substantiation, connecting Jesus and the Qumran community. But it is very unlikely that Jesus and the Qumran community were connected in any way. Some Essenes must have heard and seen Jesus, and some may have even believed Him; we just do not know. While we can cite some similarities in belief, growing out of their shared Jewish, biblical heritage, there are serious differences between some of the things Jesus taught and some of the teachings in the Qumran texts. I think Jesus had even less interaction with the Qumran community than did John the Baptist. John was working in the area close to Qumran much more regularly than was Jesus.

Suppression of the Dead Sea Scrolls

Holzapfel: The popular media has highlighted the controversy concerning scroll research and publication. Why did it take so long to get the Dead Sea Scrolls published? Was there a conspiracy to hide them?

Seely: I think it is really simple. The seven scholars who were originally involved with the scrolls did not want to give up any rights of publication. They were overly optimistic about their own ability to publish the scrolls, and they did not allow other people to see the scrolls. And of course, people like John Strugnell and John Allegro, who had sorted all the fragments of these collections, had a vested interest and a sense of ownership of the texts. They had invested some time into these scrolls.

Pike: He had invested a great deal of labor and time.

Seely: And energy. But they did not have the energy to publish the scrolls. There came a point when they had to give them up, but they did not do that willingly. But I do not think there was any kind of religious conspiracy.

Parry: There was no conspiracy, and the authors that write of such are sensationalists; I think they write about Dead Sea Scrolls conspiracies to sell books. Controversy and sensationalism sells books. It is true that the scholars did hold the scrolls close to their hearts. They shared the scrolls and byline credit with their doctoral students. They were also aware of many texts that we knew about in the 1950s but that were not published until forty years later.

Holzapfel: Do you believe that the plan was always to publish all of the scrolls and that they underestimated the amount of time and energy it would take to release them? Did it just take longer than expected?

Parry: It took a lot longer.

Pike: There were too few people trying to accomplish too large a task. In the first ten years, an enormous amount of work was done. The sorting and the organizing and the publishing just got bogged down.

Holzapfel: Do we have all the texts now? Are there any scrolls still in private possession that scholars have not had access to? Should we expect some news in the future about additional scrolls?

Pike: There are rumors that this or that scroll is floating around somewhere on the antiquities market. But as far as I know, all the scrolls that are legally owned by government entities have been or shortly will be published.

Parry: I’d say that is true. In addition, a few fragments are floating around in private collections.

Holzapfel: So any unavailable scrolls are the result of private parties owning some pieces. Is some entity like the Roman Catholic Church holding certain scrolls because the scrolls contain some great theological surprise?

Parry: No, I am unaware of any mainstream scholars who believe that the Roman Catholic Church is holding certain scrolls.

Seely: The conspiracy theories really went to pot when everything was published because the published scrolls did not support any of the rumors—nothing in the texts destroyed the Catholic Church, nothing destroyed Christianity.

Pike: Or Judaism.

Seely: Boredom set in for the alarmists once the scrolls were published because there just was not anything like that.

Brigham Young University’s Contribution to Dead Sea Scrolls Studies

Holzapfel: What significant contributions to Dead Sea Scrolls research has BYU made?

Seely: The most significant contribution is the four translators: Dana Pike, Don Parry, Andy Skinner, and myself. Our work continues beyond the publication of the work assigned to us. Other contributions include FARMS’s Dead Sea Scrolls Electronic Library.

Parry: BYU professors have made several contributions to Dead Sea Scrolls scholarship, but the most lasting seems to be those belonging to the four translators.

Pike: I agree. The four of us from BYU who were part of the international team of editors worked on the Discoveries in the Judaean Desert series and the Dead Sea Scrolls Electronic Library; these are probably the largest and most lasting contributions by BYU personnel to this point.

Holzapfel: Certainly members of the Church and BYU have provided financial and academic support to the project. Imaging and computer technology developed and highlighted at BYU have been used to push the program forward, providing the potential for a Dead Sea Scrolls database. What do you think about your invitations to participate in the official publication project, Discoveries in the Judaean Desert?

Parry: I’ve thought about this for years because people occasionally ask me, “How come you were invited to join the team of translators?” In addition to what you mentioned, I also see it as providential: I see God’s hand in all of the work here. And I want to give Him more credit, far and above any of my academic credentials. I think my own invitation to participate as a Dead Sea Scrolls scholar was an act of God.

Seely: I will speak for myself here too: it was not my credentials.

Holzapfel: However, if you had not earned good degrees, done solid work, and put in long hours, the door would have never opened.

Pike: Latter-day Saint scholarship in the areas of biblical and Dead Sea Scrolls studies is somewhere it has never been before. As in any situation, a number of factors, such as academic training and acquaintances, worked together to bring this opportunity about for us. The journey for each of us has been providential, as well. As a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania, I took a class on biblical textual criticism from Professor Emanuel Tov, who was a visiting professor there one year. Several years went by, during which we did not communicate, but he gave a presentation here at BYU in 1994, a few years after he had been appointed editor-in-chief of the Dead Sea Scrolls publication project. I saw him at a reception afterward. I walked in the room, and he said, “Dana, I didn’t know you were here.” He even remembered my first name! Later that year he invited me to participate in the official publication of the scroll fragments as a member of the international team of editors. I couldn’t have planned that if I had tried.

Parry: I see a great series of miracles, all brought forth from the Lord, that brought the four of us to the translation team.

Seely: I think BYU faculty members have worked on the scrolls because of the influence of other people: Frank Moore Cross, Moshe Weinfeld, Emanuel Tov, and others. The very act of working with scholars of other faiths is a really remarkable thing and bodes well for the future. If we continue to reach out to scholars in other areas, many good things will come of it. Reaching out like this is unprecedented.

Holzapfel: What will historians and scholars say about BYU’s efforts concerning the Dead Sea Scrolls ten or twenty years from now?

Parry: This project has helped us gain respect in many areas of the world. Internationally, many religious scholars now see the work of BYU scholars as legitimate, competent, and a contribution to knowledge.

Holzapfel: So BYU scholars have become part of the dialogue?

Parry: Yes, we have become part of the dialogue, contributing to academic journals and scholarly symposia. We are doing research and publishing our findings in scholarly journals. It is a remarkable thing.

Dead Sea Scrolls Contributions to Latter-day Saint Scholarship

Holzapfel: How are Dead Sea Scrolls studies affecting Latter-day Saint scholarship?

Seely: Until now most religion scholars at BYU, even with their training, have worked in a vacuum, largely because they were interested only in Latter-day Saint topics. Working with the Discoveries in the Judaean Desert series has been a remarkable opportunity for all of us to work not only with the text but also with the scholars. I have gained humility from working with people who are infinitely smarter than me.

Holzapfel: What do you think about the younger generation of Latter-day Saint scholars, like Thomas Wayment, Frank Judd, Eric Huntsman, Jared Ludlow, Kerry Muhlestein, and others?

Pike: When I consider our younger colleagues and others who are still in graduate school, I expect that the number of respected Latter-day Saint scholars will continue growing. More qualified Latter-day Saints will participate in Dead Sea Scrolls and Bible scholarship and related fields in the future.

Parry: There is a host of scholars in the religion departments here, specializing in all fields: Church history, Doctrine and Covenants, modern prophets, New Testament, Old Testament, Book of Mormon. It is just very impressive.

Further Reading on the Dead Sea Scrolls

Abegg, Martin, Peter Flint, and Eugene Ulrich. The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1999.

Brown, S. Kent, and Richard Neitzel Holzapfel. “The Dead Sea Scrolls.” Chap. 9 in The Lost 500 Years: What Happened between the Old and New Testaments. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2006.

Collins, John J., and Craig A. Evans, eds. Christian Beginnings and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Acadia Studies in Bible and Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2006, is an up-to-date, balanced view of the current status of scholarship about the Dead Sea Scrolls, including discussions of the Messiah at Qumran and of the Scrolls and Jesus, John the Baptist, Paul, and James.

Davies, Philip R., George J. Brooke, and Phillip R. Callaway. The Complete World of the Dead Sea Scrolls. London: Thames and Hudson, 2002.

Magness, Jodi. The Archaeology of Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003.

Parry, Donald W., and Dana M. Pike, eds. LDS Perspectives on the Dead Sea Scrolls. Provo, UT: FARMS, 1997.

Parry, Donald W., and Stephen D. Ricks, The Dead Sea Scrolls: Questions and Responses for Latter-day Saints. Provo, UT: FARMS, 2000.

Tov, Emanuel. Dead Sea Scrolls Electronic Reference Library. CD-ROM. Prepared by the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2006.

VanderKam, James C. The Dead Sea Scrolls Today. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1994.

VanderKam, James C., and Peter Flint. The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls: Their Significance for Understanding the Bible, Judaism, Jesus, and Christianity. San Francisco: Harper, 2002, contains an introduction to the discovery and history of the Qumran community, a survey of the manuscripts, and a discussion of the Dead Sea Scrolls and their significance for the study of the Old and New Testaments.

Vermes, Geza, trans. The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English, rev. ed. London: Penguin, 2004. Besides English translations of the nonbiblical texts from Qumran, this book includes an introduction to the scholarship of the scrolls, the basic scholarly issues, and the history and religious thought of the Qumran community.

Notes

[1] See Magen Broshi and Hanan Eshel, “Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls: The Contention of Twelve Theories,” in Douglas R. Edwards, ed., Religion and Society in Roman Palestine: Old Questions, New Approaches (London: Routledge, 2004), 162–69.