Profiles of the Prophets: Wilford Woodruff

Lawrence R. Flake

Lawrence R. Flake, “Profiles of the Prophets: Wilford Woodruff,” Religious Educator 7, no. 2 (2006): 137–149.

Lawrence R. Flake was a teaching professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this was written.

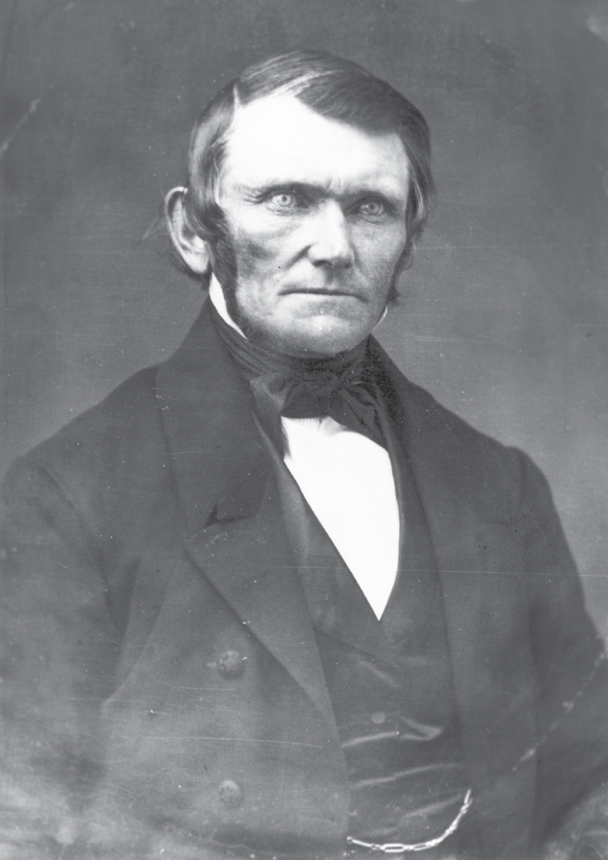

Wilford Woodruff, about 1894. Courtesy of Church Archives.

Wilford Woodruff, about 1894. Courtesy of Church Archives.

Wilford Woodruff was born March 1, 1807, in the tiny Connecticut town of Avon (Farmington). His earthly sojourn ended September 2, 1898, three thousand miles to the west in San Francisco, California. Wilford was the son of Aphek and Bulah Thompson Woodruff and the third of nine children born to Aphek. His mother died at age twenty-six when he was just fifteen months old. His father’s second wife, Azubah Hart, lovingly raised Wilford and his two older brothers. Aphek and Azubah had six children born to them, four of which died before adulthood.[1]

From an early age, Wilford labored long hours in the family flour mill beside his father and brothers, many times putting in eighteen-hour days.[2] He learned to enjoy physical labor and engaged in it throughout his long life. In his childhood, he acquired a passion for fishing. Of his early love for fishing and the outdoors, he wrote: “My mind was rather more taken up upon these subjects in my boyhood than it was in learning my books at school.”[3] Highly accident prone, he later recorded in his journal twenty-seven life-threatening incidents from which he was miraculously spared. He noted, “There has seemed to be two powers constantly watching me and at work with me: one to kill me and the other to save me.”[4]

At age fourteen, while living with a neighboring farmer and attending school in the winter, Wilford read the scriptures and participated in Presbyterian prayer meetings, but Protestantism left him feeling empty. The preaching, he later wrote, “created darkness and not light, misery and not happiness and their teachings did not seem to enlighten my mind or do me good, although I laboured hard to obtain benefit from it.”[5] As he grew older, he continued to have very strong religious feelings.

A Witness by the Spirit

In 1832, while he was still working as a miller in Connecticut, Wilford first became acquainted with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints by reading a newspaper article ridiculing the founding movement. He had a strong desire at that time to meet some “Mormons.” About a year later, after Wilford and his brother Azmon had moved to Richland, New York, two missionaries, Zera Pulsipher and Elijah Cheney, came to the home of Azmon and his wife, where Wilford was also living. The two elders extended an invitation to the family to attend a public meeting at the schoolhouse in Richland. At that first meeting, Wilford received a powerful witness of the Spirit, and before the proceedings ended he was on his feet, testifying to the audience that what the missionaries were preaching was true.[6] Shortly afterward, on December 31, 1833, at the age of twenty-six, he was baptized in an icy stream. He described his baptism in these words: “The snow was about three feet deep, the day was cold, and the water was mixed with ice and snow, yet I did not feel the cold.”[7]

Missionary Work

Ten of Wilford Woodruff’s first fifteen years in the Church were spent almost exclusively serving missions.[8] Following his baptism, he traveled to Kirtland, Ohio, where he met the Prophet Joseph Smith. Soon after his arrival there, he responded to the Prophet’s call for volunteers to join a military company called Zion’s Camp, its purpose being to make a nine-hundred-mile trek to Missouri to assist members of the Church who had been driven from their homes in Jackson County. The Prophet hoped to reinstate the refugees’ usurped property. While this mission was unsuccessful in its stated goal, it was very effective in demonstrating the character and leadership of the men who made the trip. The Prophet Joseph Smith, who led the expedition, recognized greatness in the new convert from Richland, New York, and five years later Joseph received a revelation from God calling Wilford Woodruff to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.

But in 1835, prior to his call to the apostleship, Wilford accepted an assignment to fill his first extensive mission for the Church to the southern states, where he served mostly in Kentucky and Tennessee. Reflecting on this mission, he declared that he “had traveled more than 8,000 miles and had baptized seventy people.”[9] When he returned to Kirtland, he met and married Phebe Carter, a convert to the Church and a native of Maine.

His next mission, in 1836, was to the eastern states. He labored mostly on the Fox Islands just off the coast of Maine near his wife’s family home. It was while serving as a missionary in the Fox Islands that he received a letter informing him of his call to fill one of the vacancies in the Quorum of the Twelve. He soon left the eastern states, bringing about fifty of his converts from the New England area to gather with the Saints.

Gadfield Elm Chapel in Herefordshire, England. Courtesy of Alexander L. Baugh.

Gadfield Elm Chapel in Herefordshire, England. Courtesy of Alexander L. Baugh.

In 1839, Elder Woodruff, along with several of his fellow Apostles and under very adverse circumstances, departed to fulfill a groundbreaking mission to Great Britain. In England, Elder Woodruff became the most productive missionary in this dispensation, baptizing or assisting to baptize over 1,800 converts in an eight-month period.[10] A large number of these converts were members of a congregation of United Brethren, whom he baptized in a pond on the John Benbow farm in Herefordshire.

John Benbow farm in Herefordshire. Courtesy of Alexander L. Baugh

John Benbow farm in Herefordshire. Courtesy of Alexander L. Baugh

After nearly two years of remarkable service in England, Elder Woodruff returned to the United States. In Nauvoo, he worked diligently at his calling as an Apostle and also served as business manager for the Church’s newspaper, the Times and Seasons. His dedication prompted Joseph Smith to refer to him as “Wilford the Faithful,” a title that remained with him for the rest of his life.

In 1843 and then again in 1844, Wilford accepted two more mission calls to the eastern states. During the second of these missions, while serving in Scarboro, Maine, he received the staggering news that his beloved leader and friend, the Prophet Joseph Smith, had been murdered with his brother Hyrum in Carthage Jail near Nauvoo. This devastating information came as a shock even though Joseph had given many indications and prophecies that his life would be cut short. Indeed, this very mission to the East was an effort by the Prophet to get Elder Woodruff and other Apostles out of Nauvoo for their own safety.

Elder Woodruff, about 1850. Marsena Cannon, Courtesy of Church Archives.

Elder Woodruff, about 1850. Marsena Cannon, Courtesy of Church Archives.

Presiding over the European Mission

Following the death of the Prophet, Elder Woodruff returned to Nauvoo, but very soon his talents and leadership were sorely needed again in England. In August of that same year, only two months after the death of Joseph and Hyrum, Wilford and Phebe departed for the British Isles to preside over the European Mission headquartered in London. They took their one-year-old daughter with them but had to leave their other two children in the care of relatives and friends.

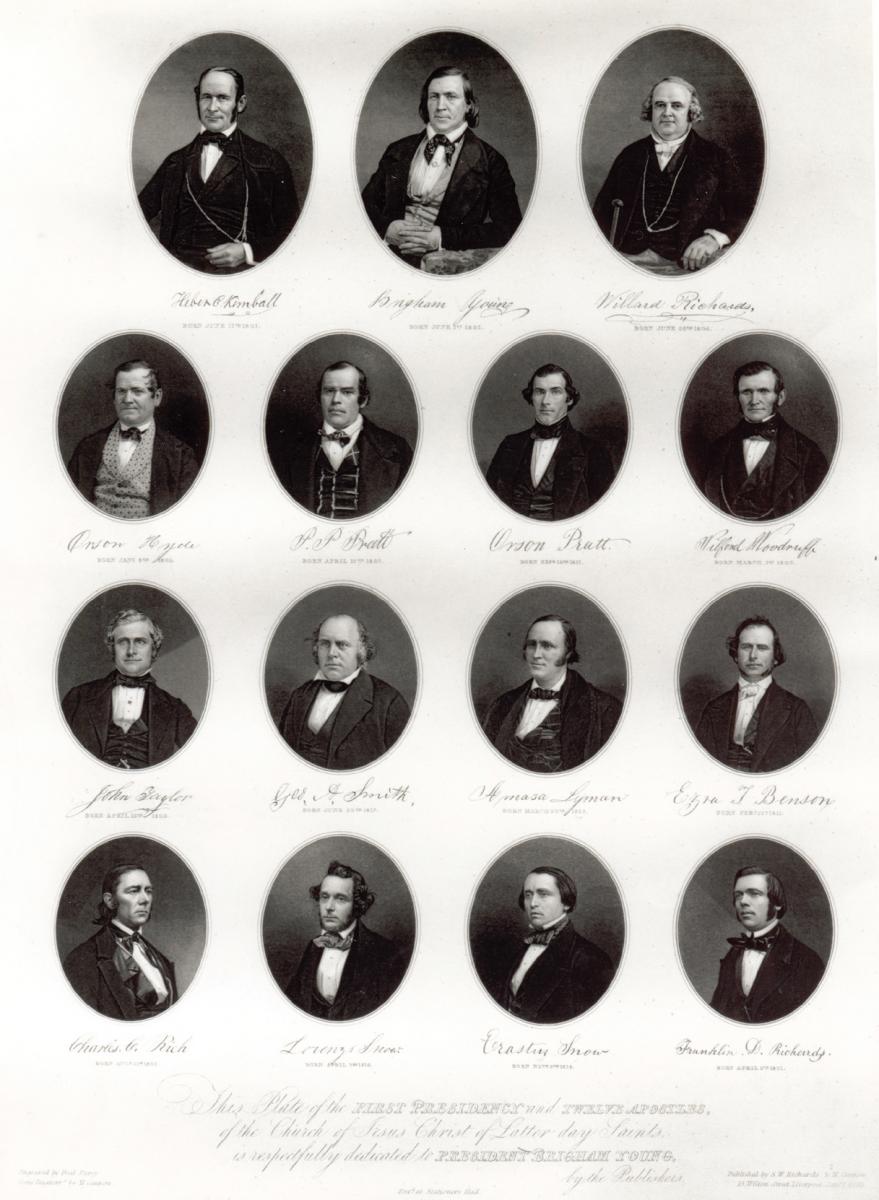

The First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, 1853. Courtesy of Church Archives.

The First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, 1853. Courtesy of Church Archives.

Salt Lake Valley

Upon his return from Great Britain nineteen months later, on April 13, 1846, Elder Woodruff worked closely and tirelessly with Joseph Smith’s successor, President Brigham Young, to accomplish the overwhelming task of moving thousands of Saints across the continent to the valley of the Great Salt Lake. In the spring of 1846, Elder Woodruff, along with many other refugees from Nauvoo, moved his family across the Mississippi River to Mount Pisgah, Iowa, and from there traveled to Winter Quarters, Nebraska, where they remained for the winter. In the spring, he traveled west with the advance pioneer company and was among the first Latter-day Saints to enter the Salt Lake Valley.

During the approximately forty years from his arrival in the Salt Lake Valley until he became President of the Church in 1889, Elder Woodruff engaged in a variety of pursuits. He was passionate about improving the level of education for himself and the Saints throughout the valley and participated in several organizations to advance learning. Among these were the Universal Scientific Society and the Polysophical Society, the latter designed to promote the theater and other fine arts. His real passion, however, seemed to lie in improving the quality of crops in the new territory. He tirelessly studied scientific farming methods, led the way in Utah in importing seeds, grafts, and superior strains of plants from places as far away as England, and established the Horticultural Society.[11]

In 1856, he became assistant Church historian and made extensive collections and revisions of historical Church documents, continuing almost single-handedly to keep the current Church records. During this same period, Elder Woodruff was a key figure in a movement known as the “Reformation” which called the general members of the Church to repentance and recommitment. He was often credited with lending a more “fatherly” edge to what some considered too harsh an approach.[12]

In 1876 and 1877, Elder Woodruff’s life became focused on the completion of the first temple in the West in the southern Utah settlement of St. George. President Young asked him to offer the dedicatory prayer for the temple and to serve as its first president. He was an ardent promoter of temple work, officiating in hundreds of baptisms, endowments, and sealings, particularly on behalf of the dead, and urging his fellow Saints to do the same. It was in this temple that he had the glorious experience of performing vicarious ordinances on behalf of many deceased American patriots and “eminent men.”[13]

Following the death of President Young in 1877, the Church entered a particularly turbulent era. For three years, John Taylor led the Church as president of the Twelve until 1880, when the First Presidency was reorganized. In 1885, raids and convictions of Utah polygamists forced Elder Woodruff into hiding. He spent much of his time in St. George until President Taylor’s death in 1887. In spite of precedent, there was still some confusion over the procedure for succession to the presidency of the Church. An awkward period called an “interregnum,” where the Twelve governed the Church for a few years between Presidents, occurred following the deaths of the first three Presidents of the Church: Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, and John Taylor. While it did not seem to serve any real purpose in Wilford Woodruff’s case, this precedent was followed once again for two years, from 1887 to 1889, when the First Presidency was finally reorganized.

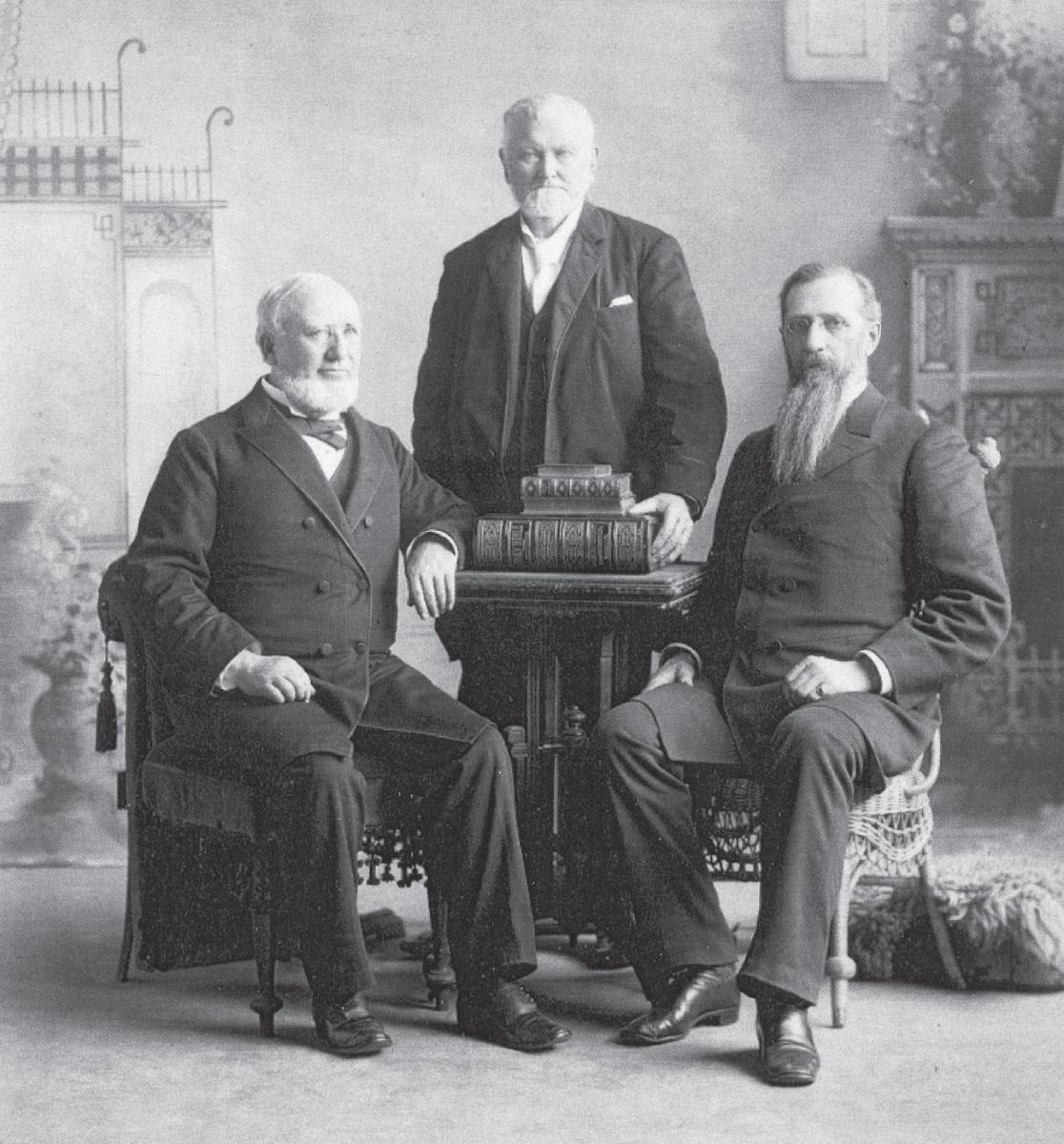

President Woodruff and counselors in the First Presidency, George Q. Cannon (left) and Joseph F. Smith (right), 1894. Courtesy of Church Archives.

President Woodruff and counselors in the First Presidency, George Q. Cannon (left) and Joseph F. Smith (right), 1894. Courtesy of Church Archives.

President of the Church

On April 7, 1889, after the two-year interregnum, Elder Woodruff assumed the role of prophet, seer, and revelator of the Church. He was eighty-two years old but still in vigorous health. His decade as President encompassed three remarkable developments in the kingdom. First, in 1890 he received the revelations that led to the issuing of the Manifesto, which ended the contracting of plural marriages. Second, in 1893 he oversaw the completion and dedication of the magnificent Salt Lake Temple. And third, in 1896, after nearly half a century of failed attempts, he helped to finally attain statehood for Utah.

Manifesto

When John Taylor died in 1887, the Saints were in the midst of severe persecutions as a result of congressional antipolygamy legislation. Fear of arrest kept Elder Woodruff from attending President Taylor’s funeral as it previously had prevented him attending the funeral of his first wife, Phebe Carter, who died two years earlier in 1885. The government continued its abuses against the Church, bombarding it with accusations, property confiscation, and imprisonment of its members.

For many agonizing months, President Woodruff petitioned the Lord for a solution to the plight of the Church. Finally, the Lord answered his prayers through a series of revelations, which opened up a sobering vision to him. He saw clearly how dire the future of the Church would be if the members continued to practice plural marriage. After receiving these pivotal revelations, President Woodruff made the wrenching decision to officially end the contracting of all plural marriages. Despite the intense unpopularity of this decision with many members of the Church and even with some members of the Twelve, the prophet fearlessly defended it and eventually convinced most Latter-day Saints of its validity. The official announcement of this monumental decision was called the Manifesto of 1890 and stated emphatically that no further plural marriages would be sanctioned or contracted by the Church.

Completion of the Salt Lake Temple

Although the 1890s opened with a great deal of political and social turmoil, President Woodruff felt inspired to make finishing the Salt Lake Temple a priority. In the 1891 October conference, he announced his determination to complete the temple and dedicate it on April 6, 1893, forty years to the day that the cornerstone was laid. He solicited the support of the Saints, both spiritually and financially. President Woodruff became very involved personally in seeing that the work went forward. The physical advantages of finishing the temple were dwarfed in comparison to the spiritual dimensions President Woodruff hoped to achieve by dedicating it at that time. He saw in its completion the opportunity to promote unity in the Quorum of the Twelve where some dissention over the discontinuation of polygamy still lingered. Some members of the Church were also flagging in their commitment and unity. President Woodruff had faith that the temple dedication would bolster their spirituality and bring down upon all of them much-needed blessings from heaven. With the Saints putting forth a decidedly superhuman effort and with many blessings from the Lord, the temple was in fact finished and ready for dedication on April 6, 1893.

Forty-six years earlier, just two days after their arrival in the Salt Lake Valley, Wilford Woodruff stood with Brigham Young on the temple site, saw the prophet put his cane into the ground, and heard him declare, “I am going to build a temple here.”[14] The prophecy was at last fulfilled, and the presence of the glorious temple blessed the Church with the strength they needed to endure the many trials that still lay ahead.

Statehood

In 1861, following the failure of repeated attempts to attain statehood, President Brigham Young and other General Authorities reconstituted a group of men, mostly Church leaders, and called it the “Council of Fifty,” the name by which a former governing body in Nauvoo was known. The First Presidency also reactivated the School of the Prophets, which was first held in Kirtland. These two organizations served as a means for Latter-day Saint leaders to maintain some influence over Church members in public matters. Wilford Woodruff played a prominent part in both of these groups.[15]

For many years after President Young’s death in 1877, the problems with antipolygamy legislation completely dominated Utah politics and scuttled every attempt to achieve statehood. In 1872, Utahns attempted again to obtain statehood. This time, they drew upon the influence of non-Mormon friends of the Church, such as former territorial appointees who had lived in Utah, but again the effort was unsuccessful. During 1887, and in a desperate effort to make some progress toward their goal, Church leaders began to “court” political leaders, especially Democrats, who seemed sympathetic to the Latter-day Saint plight. They even urged missionaries to soften their proselytizing approach in order to lessen what Democratic supporters of the Church in Congress, especially southerners, considered insults to their churches.[16]

Following the publication of the Manifesto of 1890, which signaled the official end of plural marriage, the goal of achieving statehood finally became realistic. At that time, nearly all members of the Church belonged to a political party called the People’s Party. Members of other persuasions were by and large marshaled against them in what was called the Liberal Party. It was apparent to President Woodruff and other Utah leaders, both ecclesiastical and political, that Utahns needed to align themselves with the two prevalent parties of the United States, Democrats and Republicans. President Woodruff urged members of the Church to disband the People’s Party and affiliate with either of the two established national parties. In fact, in some cases, Church leaders almost “assigned” Church members to one group or the other in order to form an equal division between the two. Accomplishing this revolutionary realignment was a major shift in Church policy and inevitably caused many points of contention over politics between members of the Church, which had not existed to this great an extent previously. But this radical change in Utah politics, along with the ending of plural marriage and what proved to be the invaluable influence of their friends from other faiths, turned the tide of popular opinion in Utah’s favor. Following the return to power of a Democratic congress in the election of 1892, Joseph L. Rawlins, the newly elected delegate from Utah Territory, once again introduced the petition for Utah statehood to the House of Representatives. It passed on December 13, 1893, practically without opposition.[17] Largely due to President Woodruff’s efforts in settling the plural marriage issue, the stormy, half-century struggle to be freed at least in part from the oppressive rule of the federal government finally met with success. Consequently, an incredibly far-reaching change was wrought in the future of Utah and the Church.

Later Years

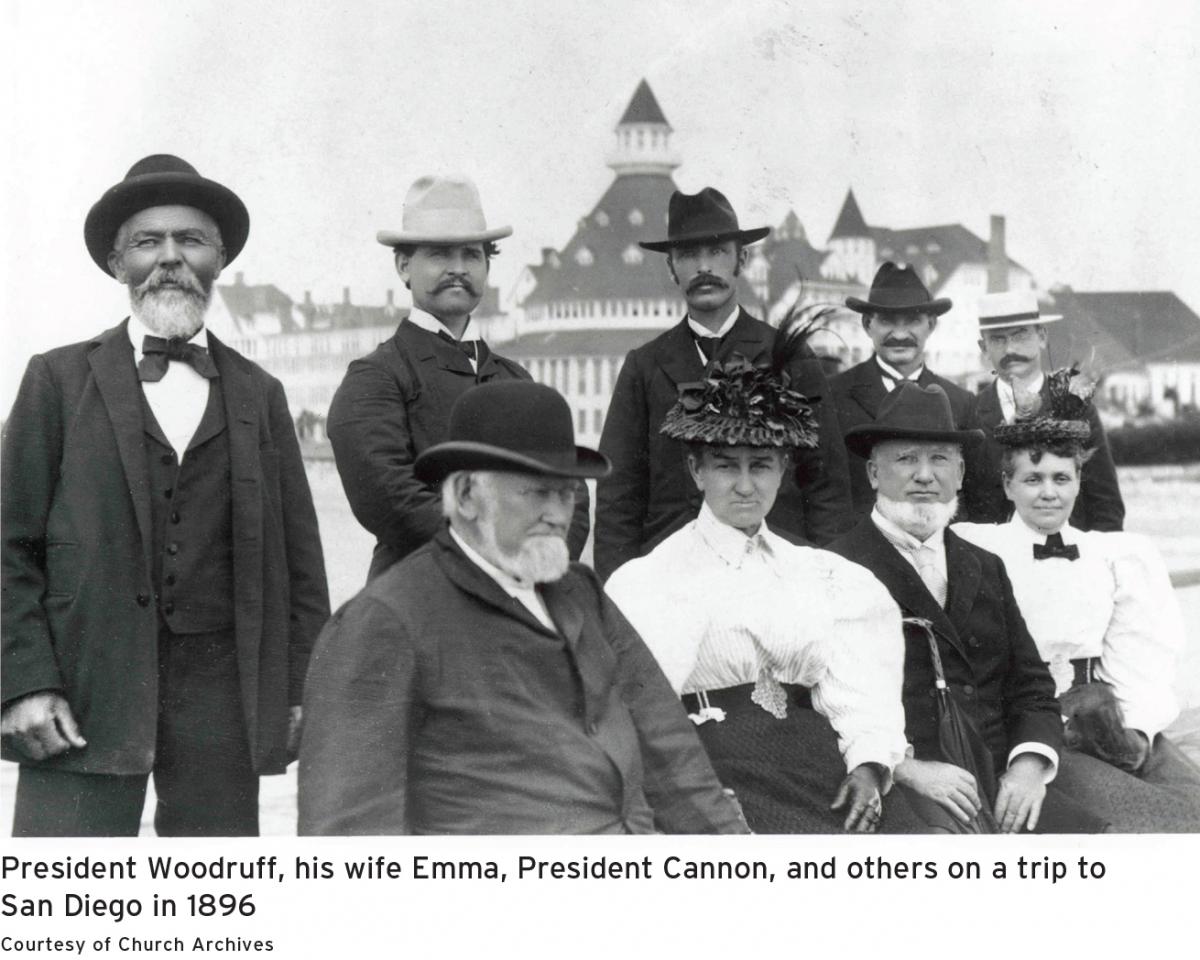

During his later years, President Woodruff was afflicted with poor health. Though not incapacitated, he suffered many bouts of illness. It was following an attack that he sought rest in the favorable climate of California, a place he had grown to love. Arriving in San Francisco in August 1898, he underwent an extremely painful bladder operation. He appeared to be recuperating and participated in a number of civic activities with some of the many friends and acquaintances he had made in that state. One of his biographers wrote, “Then suddenly on September 1, he experienced complete kidney and bladder failure, and he rapidly lapsed into a coma. Doctors and those with him recognized that he could not survive such a crisis and he died at the Trumbo home at 6:40 a.m. on Friday, September 2.”[18] He was ninety-one. This man whom the Lord had preserved through so many accidents of childhood and trials of adulthood lived nearly a century and served Him valiantly, distinguishing himself as one of the great Presidents of the Church.

Notes

[1] Thomas G. Alexander, Things in Heaven and Earth: The Life and Times of Wilford Woodruff, a Mormon Prophet (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1991), 6.

[2] Susan Arrington Madsen, The Lord Needed a Prophet (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1990), 61.

[3] Dean C. Jessee, “Wilford Woodruff,” in The Presidents of the Church, ed. Leonard J. Arrington (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1986), 117.

[4] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, ed. Scott G. Kenney (Midvale, UT: Signature Books, 1983), 4:414–15; spelling and punctuation modernized.

[5] Jessee, “Wilford Woodruff,” 118.

[6] Madsen, The Lord Needed a Prophet, 63–64.

[7] Matthias F. Cowley, Wilford Woodruff: History of His Life and Labors (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1984), 35.

[8] Lawrence R. Flake, Prophets and Apostles of the Last Dispensation (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2001), 44.

[9] Alexander, Things in Heaven and Earth, 42; see also Journal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, November 25, 1836, Church Archives, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

[10] Woodruff diary, synopsis following the year 1885; in Dean C. Jessee, “Wilford Woodruff: A Man of Record,” Ensign, July 1993, 30.

[11] See Alexander, Things in Heaven and Earth, 170–73.

[12] Alexander, Things in Heaven and Earth, 184.

[13] Bryant S. Hinckley, The Faith of Our Pioneer Fathers (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1956), 41.

[14] The Discourses of Wilford Woodruff, ed. G. Homer Durham (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1998), 322–23.

[15] Alexander, Things in Heaven and Earth, 206–7.

[16] Alexander, Things in Heaven and Earth, 248.

[17] Alexander, Things in Heaven and Earth, 282.

[18] Alexander, Things in Heaven and Earth, 330.

Appendix: Life and Times of Wilford Woodruff

| 1807, March 1 | Born in Farmington, Hartford County, Connecticut |

| 1832 | Moved to Richland, New York, with his brother Azmon |

| 1833, December 31 | Baptized into the Church |

| 1834 | Met Joseph Smith and participates in Zion’s Camp march to Missouri |

| 1837, April 13 | Married Phebe Carter in Kirtland, Ohio |

| 1838 | Received a letter advising him of his call to be an Apostle |

| 1838 | Raised his wife Phebe from the dead following a severe illness |

| 1839, April 26 | Ordained an Apostle in Far West, Missouri |

| 1839–41 | Served a mission to Great Britain |

| 1844–46 | Presided over the British Mission with his wife Phebe |

| 1847, July 24 | Entered the Salt Lake Valley with Brigham Young |

| 1851 | Appointed to the Utah Territorial Legislature |

| 1856 | Appointed Assistant Church Historian |

| 1867 | Participated in the reestablishment of a School of the Prophets |

| 1876 | Called as first president of the St. George Temple |

| 1877 | Provided temple ordinances for prominent American patriots and leaders |

| 1889, April 7 | Sustained as President of the Church |

| 1890 | Issued the Manifesto concerning plural marriage |

| 1896, April 6 | Dedicated the Salt Lake Temple |

| 1898, September 2 | Died in San Francisco, California, at age ninety-one |