Welcoming All of God’s Children in His House: Supporting Members with Disabilities

Tina Taylor Dyches

Tina Taylor Dyches, “Welcome All of God's Children in His House: Supporting Members with Disabilities,” Religious Educator 7, no. 1 (2006): 91–102.

Tina Taylor Dyches was an associate professor of special education at BYU when this was written.

Ability and disability are inherent parts of our mortal existence. While some people are born with disabilities, many acquire them through accidents, illnesses, or conditions incident to aging. Disabilities are conditions that hinder adequate or normal functioning of the mind and body, and they are often chronic in nature.

One great way to help our ward family grow closer together is to consider the needs of others, especially families who have children with disabilities.

Members with Disabilities in Our Wards

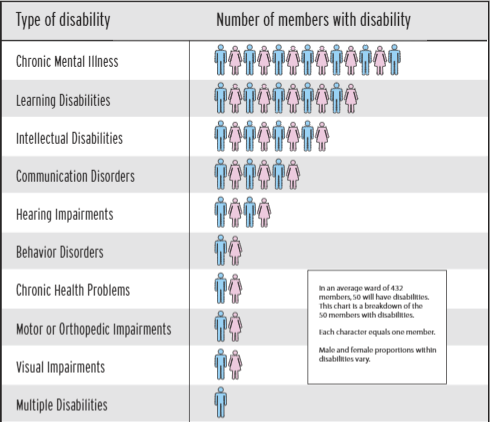

Many Church members may be able to identify only a few in their ward with disabilities. Often, the most visible disabilities come to mind (e.g., those who are blind, deaf, who have significant intellectual disabilities, or who are in wheelchairs). However, if general population statistics are reflected in the average North American ward of 432 members, 50 (or approximately 12 percent) would have disabilities that warrant special attention. Of these 50, 13 would have a chronic mental illness, 10 would have learning disabilities, 8 would have intellectual disabilities, 6 would have communication disorders, and 4 would have hearing impairments. Two would have behavior disorders, 2 would have chronic health impairments, 2 would have motor and orthopedic impairments, 2 would have visual impairments, and 1 would have multiple disabilities.[1]

If you are in a leadership position in your ward, you should be aware of the special needs of all of the members in your organization. Is there an empty pew that should be filled by one of these fifty members? Ask yourself these questions: “Where are the people with disabilities in my ward?” “Are some invisible to me?” and “Are some not attending church?”

A personal example illustrates the need to answer these questions. I am the Sunbeam teacher in my ward. Part of my stewardship is to know the individual nature of each of the eight children in my class. I may not know if these youngsters have a disability because most mild disabilities are not detectable at the age of three or four. However, I could choose to ignore the individual ways my Sunbeams learn the gospel of Jesus Christ, or I could pay particular attention to how Samantha needs to change activities every two to three minutes, how Cabe needs pictures to help me understand his speech, and how Max needs to sit on my lap while I draw pictures of dinosaurs during sharing time to keep him from getting his head stuck in the back of his chair! I also need to know why Tasha has not come to Primary since her name appeared on my roll. Does she have a special circumstance that makes it difficult for her and her family to feel welcome at church?

Welcoming All Members in God’s House

Our Heavenly Father desires that His children no longer be “strangers and foreigners, but fellow citizens with the saints, and of the household of God” (Ephesians 2:19). Those of us who are active in the household of God have an obligation to provide an environment in which all of His children are welcome. We can begin to fulfill this obligation by asking these questions regarding those under our stewardship: “Are they attending sacrament meeting?” “Are they attending priesthood, Relief Society, Young Men or Young Women, Primary, seminary, and institute meetings and activities?” “Are they visited by sensitive home teachers or visiting teachers?” “Are they given callings to serve others in the ward or stake?” “Are they receiving all the blessings of the gospel afforded to those without disabilities?”

The blessings of the gospel are intended for all of God’s children, not just for those who are physically, intellectually, and emotionally astute. A personal example illustrates this concept. When I was a young college student earning my degree in special education, I met Carol at a school for students with intellectual and multiple disabilities. Our interactions were brief because I spent most of my volunteer time with children younger than Carol. I finished my volunteer work at the school and moved on to other learning and teaching experiences in locations far from this special school. Fifteen years later, while I was with my two-year-old son at McDonald’s, I saw Carol again. Nearing our table to clean it, she immediately recognized me, and I her. When I realized she had previously attended the special school, I was amazed! She was doing so well with her life. This was not the expected outcome for many of these students at that time. After doting on my son she told me, in simple but sincere words, how the gospel had blessed her life. She showed me her wedding ring and informed me that she had married a fine man in the temple, that she had helped support her brother on a mission, and that after her shift at work, she often took the bus to the temple where she served diligently. Although her intellectual capabilities are impaired, her spirit and determination to follow the counsel of the prophet have been magnified.

Carol had intellectual disabilities that limited some of her life experiences; yet, she and her family felt blessed. These feelings are present in many families who report unique spiritual blessings that come from raising a child with disabilities. In some of our research regarding how families adapt to raising a child with special needs, parents offered comments regarding how their spiritual and religious perspective facilitated positive adaptation.[2]

Many indicated that raising a child with special needs is a spiritual experience. Parents described the spiritual experience as part of a journey to a unique perspective. They also adapted positively over time after the initial crisis of learning about the child’s disability. However, they also described fluctuating spirituality, ranging from heightened experiences of personal knowledge to depths of despair regarding whether religion provided any support.

Parents reported a sense of unique knowledge, or insights that were “beyond” others who were either not of their faith or who were not raising a child with disabilities. Almost every couple expressed this sense of uniqueness, that “because of our beliefs, our family is different from others.”[3]

Three themes helped parents build and expand their personal faith. These were shared family beliefs in Church tenets, social support from members of the Church community, and family unity in Church participation. Personal faith was developed when families shared theological perspectives regarding the experience of raising a child with disabilities and when they could rely on community members for support. However, when parents differed in their level of religious participation, they experienced a degree of dissonance.

Parents described an ongoing process of transformation based on faith and religious belief. One father stated: “I look at these poor families that sit and say that it’s not fair and that God’s cursing them. It’s so meaningless. We don’t know exactly why we have him, but our base feeling is that we’re fortunate to have him; we’re not cursed or [have] bad luck. We didn’t do anything wrong; [neither are we] being punished. . . . It makes a big difference in our day-to-day outlook; and the frustrations we have with him affect us less because we know we have this basic belief and faith.”[4]

Some parents expressed that they feel blessed to parent their disabled child, and that this perspective allows them to view their child’s special worth and helps them deal with any hardships that come. Parents often “referred to their children as a ‘blessing,’ having a special purpose, helping the family to view an ‘eternal perspective,’ and ‘having it made’ or assured blessings in heaven.”[5]

Yet not all families have spiritual confirmations regarding the special challenges God gives to His children. Some families experience challenges that may keep them from enjoying the blessings of the gospel.

Spiritual Challenges of Families with Children Having Disabilities

In some of our research, parents offered information regarding how religion can help them cope with the challenges of raising a child with a disability.[6] Some families are challenged by their desire to find meaning in the experience of raising a child with disabilities, by feelings of ambivalence regarding how religion can help, by the fear of not fitting into the Church community, and by family dissonance in Church participation.

Finding meaning in the experience. President Thomas S. Monson has given advice to families who struggle to find meaning in the experience of raising a child with a disability or other chronic illness. He stated:

In our lives, sickness comes to loved ones, accidents leave their cruel marks of remembrance, and tiny legs that once ran are imprisoned in a wheelchair.

Mothers and fathers who anxiously await the arrival of a precious child sometimes learn that all is not well with this tiny infant. A missing limb, sightless eyes, a damaged brain, or the term “Down’s syndrome” greets the parents, leaving them baffled, filled with sorrow, and reaching out for hope.

There follows the inevitable blaming of oneself, the condemnation of a careless action, and the perennial questions: “Why such a tragedy in our family?” “Why didn’t I keep her home?” “If only he hadn’t gone to that party.” “How did this happen?” “Where was God?” “Where was a protecting angel?” If, why, where, how—those recurring words—do not bring back the lost son, the perfect body, the plans of parents, or the dreams of youth. Self-pity, personal withdrawal, or deep despair will not bring the peace, the assurance, or help which are needed. Rather, we must go forward, look upward, move onward, and rise heavenward.[7]

Ambivalence regarding how religion can help. While some parents perceive their religiosity as a benefit in raising a child with a disability, some feel ambivalent regarding the helpfulness of the Church.

Some parents receive misguided advice from members of the Church community. One father said, “At first it was tough. People would say that we were blessed, and we’d look at each other and say, ‘Do you feel blessed? I don’t.’ One mother expressed, ‘Sometimes you feel really blessed, but you don’t want to hear it from everyone 10 times a day. I’ve talked to a couple of other moms, and they don’t see it as a blessing.’ Parents recognized that Church members were trying to be supportive but noted that such statements are not helpful and that a realization of a blessing emerged from within the family’s own belief system and time period and not from suggestion or advice from other church members.”[8]

Another mother regretted, “My mom said if I prayed enough he would be fine. Then after he was born and he had problems, she said if I had more faith it would have been OK.”[9]

Fear of not fitting into the Church community. Some parents felt isolated because they feared their child would behave inappropriately at Church meetings, or that they might be treated unkindly by Church members. “A father related, ‘A kid [at church] turned around and called her “flat face.”‘ In another home, a mother reported that the . . . parents alternated church attendance to allow one parent to stay home to care for the child with the disability, thus avoiding situations where the family did not fit.”[10] Unfortunately, this experience is all too common for families raising children with significant disabilities.

Family dissonance in Church participation. Some families felt dissonance in their family, particularly when one spouse is actively involved in the Church and the other is not. Another type of dissonance was based on their expectations for the child with disabilities as they participated in specific church ceremonies. Some parents wondered how, when, or whether their child might participate in priesthood ordinations and saving ordinances such as baptism. Some parents were concerned that their child not being involved in these ceremonies would call attention to how their child was different from others.

The Church’s Unique Role

While many governmental programs exist to help people with disabilities and their families with their temporal needs, the Church exists to help them with their spiritual needs. This leads members to ask whether we in the Church are fulfilling our obligations to “succor those that stand in need of succor” (Mosiah 4:16).

We asked ninety-seven sets of parents who were raising a child with a disability regarding the services they found helpful. They noted that the following services and organizations were most helpful: schools, government services, private organizations, extended family, friends and neighbors, medical professionals, and support groups. Interestingly, Church members and wards were rarely mentioned, and 90 percent of these parents were Latter-day Saints.[11]

Barriers to full participation in the Church may be substantial for many families raising a child with disabilities. Yet our Heavenly Father wants them to enjoy all of the blessings of the gospel.

“None Are Forbidden”

“Behold, hath he commanded any that they should depart out of the synagogues, or out of the houses of worship? Behold, I say unto you, Nay. Hath he commanded any that they should not partake of his salvation? Behold I say unto you, Nay; but he hath given it free for all men. . . . But all men are privileged the one like unto the other, and none are forbidden” (2 Nephi 26:26–28).

Elder W. Craig Zwick has noted what we as members and leaders in the Lord’s household must do in order to invite all of His children to participate: “Our task, facilitated by prayer, is to recognize even the slight limitations of each person who may be suffering pain or discouragement. It may be a minor learning disability, dyslexia, or a slight hearing impairment. Without our help, they may be unable to partake of the Savior’s goodness or enjoy the fulness of life.”[12]

How Church Members Can Help

Members of the Church can welcome those with disabilities into the Church by knowing and loving the families of the child with special needs, inviting them to participate and contribute in Church activities, providing respite care, helping each member learn about the Savior and His gospel, and making the church building accessible.

Know and love the families. The best vehicle for knowing and loving families is home teaching and visiting teaching. These teachers should be selected with care because they need to be sensitive to the special conditions of the child and the family. The family may also need to rely upon these teachers more than families who are not in similar circumstances.

In some of our research, we had children with moderate to severe disabilities take pictures of what was important to them. One boy with Down syndrome took several pictures of his home teachers, noting they were loved as dearly as family. It was clear by the joy Dallin expressed when he showed us his snapshots that he felt valued and cared for by these home teachers. They were there for him at the many important junctures of his life, not just for important religious events.[13]

By ascertaining the needs of the family, members can find ways to help them participate more fully. Home teachers and visiting teachers and other Church leaders should get a clear sense of the spiritual needs of the family. Can they participate in their church meetings, attend the temple, fulfill their church callings? Their social needs also should be met. The Church is a society of brothers and sisters. Often, these parents feel so burdened by the daily demands of their child with disabilities that they haven’t the time to be “fellow citizens with the saints” (Ephesians 2:19). Once the participation patterns of the family are known, then the leader can work to reduce barriers to full access.

Members can also work to reduce the barriers that prevent the families from attending church. Two types of barriers may prohibit full access to Church participation: access barriers and opportunity barriers.[14]

Access barriers are those that hinder access to the environment, such as steps leading into the chapel, narrow bathroom stalls, and poor lighting. The standard design of modern Latter-day Saint church buildings is generally compliant with laws for accessibility, although older buildings may have access barriers that prevent the full participation of some members.

Opportunity barriers hinder full participation due to policy, practice, attitudes, knowledge, and skills of those in the community. For example, when Primary leaders require the mother of the child with a disability to be the child’s one-on-one teacher, the child is not able to fully participate with her peers in Primary, nor is the mother allowed to fully participate in Relief Society. Further, other Primary children are not given the opportunity to learn to learn alongside those who may appear to be different from them.

Opportunity barriers are not the responsibility of the general contractors of the Church. We, as members, must recognize the barriers we place on those with special needs, and work to reduce and even eliminate those barriers.

Invite them to participate and contribute. Some families may need transportation to get to church, seminary, institute, or other Church-related activities. Others may just need an invitation—to feel that somebody cares about them and their spiritual welfare. Leaders can provide callings or responsibilities that fit the needs of the member with disabilities and of the Church alike.

For many years in my ward, Mark’s calling was to place the hymn numbers on the board for our sacrament meeting. He was dedicated and accurate in his calling. When Mark’s parents left for a mission and Mark moved to live in a group home, we felt a deep void in our ward. I was the music leader and missed him the most, I think, because I couldn’t quite reach the top of the hymn board!

We shouldn’t assume that just because members have a disability they cannot enjoy the blessings of the gospel. Elder James E. Faust said, speaking of those with disabilities: “Many . . . are superior in many ways. They, too, are in a life of progression, and new things unfold for them each day as with us all. They can be extraordinary in their faith and spirit. Some are able, through their prayers, to communicate with the infinite in a most remarkable way. Many have a pure faith in others and a powerful belief in God. They can give their spiritual strength to others around them.”[15]

Provide respite care. Members can tend the child with a disability so the parents can attend their church meetings. They can sit with the family and help if the child is restless or disruptive in church. Members should avoid giving harsh looks when a child is disruptive in church; instead, show increased love and understanding. It is natural to turn and look when a peaceful environment is disrupted. However, when the look is one of compassion rather than disdain, the family is more likely to continue to participate in church services. When feelings of compassion elicit acts of service, the reward is even greater.

Help each member learn about the Savior and His gospel. Members, leaders, or parents can invite a disability specialist to provide an in-service to Church leaders and teachers. Special educators are employed at almost every public school in the United States. Also, many universities have special education departments with professors who could provide ward members with effective strategies for teaching those with disabilities. Further, the greatest experts regarding children with disabilities are the children’s parents. They may be willing and anxious to provide ward members and leaders with instruction that is relevant to their child.

Members and leaders can consider integrating children with disabilities with nondisabled peers to the maximum extent appropriate. Most people don’t like to be singled out, particularly for their deficits. When we integrate individuals with disabilities with members of the ward who do not have disabilities, all members can benefit. Expectations are raised, normal patterns of behavior are modeled, love and compassion are shared.

As Elder Marion D. Hanks was reflecting on Joseph Smith’s revelation that “all the minds and spirits that God ever sent into the world are susceptible of enlargement,”[16] he received a forceful impression that “God expects that His handicapped children will be given an opportunity for that enlargement, and that His disciples will accept the great responsibility to be concerned that they are. ‘Bear ye one another’s burdens, and so fulfill the law of Christ.’ (Gal. 6:2.).” [17]

Those in teaching positions can use ideas from Teaching—No Greater Call, and resources from LDS Special Curriculum. They can also adapt curriculum as necessary (for example, using materials adapted for those with specific disabilities, or using the Beginning Course Kit, which introduces the scriptures to beginning learners, helping them understand and read the scriptures).

Make the Church building accessible. Members can ask themselves, “Does my ward provide transportation? Marked accessible parking places? A ramp with a reasonable slope and sufficient width? Pews cut at scattered sites? Accessible bathrooms? Accessible water fountains? An elevator or chair lift? Air filters or fragrance-free sections? Large print materials, sign language interpreters, and sound amplification?” If the answer is “no” for any of these questions, then ward or stake leaders should find ways to eliminate these barriers so that every member can fully participate. For “the body hath need of every member, that all may be edified together, that the system may be kept perfect” (D&C 84:110).

Church Resources

Many resources exist for members with disabilities and those who serve them. Some are available through Special Curriculum, while most are available through the distribution centers or the online catalog. Examples include the Including Those with Disabilities packet and the materials listings for those with hearing impairments, intellectual impairments, and visual and physical disabilities.

The Church catalog offers various materials to alleviate the barriers those with disabilities face in accessing the curriculum and standard works of the Church. Many materials are available in Braille, large print, half- or standard-speed cassette tapes, and American Sign Language, including the Dictionary of Church Sign Language Terms, Interpreting for Deaf Members Handbook, CDs, music, hymns, and The Children’s Songbook.

Also, materials are available from the Boy Scouts of America to help Scouts learn about those with disabilities through a “disabilities awareness” merit badge. This merit badge requires scouts to visit an agency that serves people with disabilities, interact with someone with a disability, spend fifteen hours helping a scout with disabilities, study the accessibility of public and private community places, display a summary of what was learned, and make a commitment to help people with disabilities. Several booklets are available to help leaders understand and serve scouts with disabilities in their troops. Although outdated, these booklets may be a good starting point for serving Scouts who have learning disabilities, physical disabilities, hearing impairments, and visual impairments. The intent of these booklets is to ensure that all boys who want to be a Scout will have the opportunity to do so and to have it be a successful experience.[18]

Come unto Christ

The gospel is preached so that all may come unto Christ. The Apostle Paul, in writing to the Corinthians, explains that we are all “the body of Christ, and members in particular” (1 Corinthians 12:27). He explains, “For the body is not one member, but many. If the foot shall say, Because I am not the hand, I am not of the body; is it therefore not of the body? . . . If the whole body were an eye, where were the hearing? If the whole body were hearing, where were the smelling? But now hath God set the members every one of them in the body, as it hath pleased him. And if they were all one member, where were the body? But now are they many members, yet but one body” (1 Corinthians 12:14–15, 17–20).

The Lord has need of all members of His Church to fulfill His purposes. I have indeed been blessed by so many members of the Church who have special needs. When we were teenagers, John taught me about courage and perseverance. He came to church week after week although others teased him about his dress, hygiene, and intellectual capabilities. My Sunday School teacher, Sister Poor, taught me to seek true meaning from the word of the Lord. Her diligent reading of the standard works in Braille taught me to not just read the word of the Lord, but to truly feast on it. James, my Sunday School classmate, taught me to ask thoughtful questions about the gospel and to break through the barriers of deafness to communicate spirit to spirit. Max, one of my Sunbeams, taught me to always keep an eye on my students—to never let them out of my sight—for all are precious in the sight of God and it is my stewardship to include, teach, and love them. It is my prayer that we will do our part to welcome all of God’s children into His house.

Notes

[1] Members with Disabilities, LDS Special Curriculum, 2.

[2] Elaine S. Marshall and others, “‘This Is a Spiritual Experience’: Perspectives of Latter-Day Saint Families Living with a Child with Disabilities,” Qualitative Health Research 13, no. 1 (2003): 57–76.

[3] Marshall, “‘This Is a Spiritual Experience,’” 63–65.

[4] Marshall, “‘This Is a Spiritual Experience,’” 67.

[5] Marshall, “‘This Is a Spiritual Experience,’” 68.

[6] Marshall, “‘This Is a Spiritual Experience,’” 70.

[7] Thomas S. Monson, “Miracles—Then and Now,” Ensign, November 1992, 68.

[8] Marshall, “‘This Is a Spiritual Experience,’” 65.

[9] Marshall, “‘This Is a Spiritual Experience,’” 65.

[10] Marshall, “‘This Is a Spiritual Experience,’” 65–66.

[11] Tina Taylor Dyches, Barbara Mandleco, and Susanne F. Olsen, “Helpful Services for Families with Children with Developmental Disabilities,” working paper, 2004.

[12] W. Craig Zwick, “Encircled in the Savior’s Love,” Ensign, November 1995, 13.

[13] Tina Taylor Dyches and others, “Snapshots of Life: Perspectives of Children with Developmental Disabilities,” Research and Practice in Severe Disabilities 29, no. 3 (2004): 70.

[14] David R. Beukelman and Pat Mirenda, Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Management of Severe Communication Disorders in Children and Adults, 2nd ed. (Baltimore: Brookes, 1998), 6:153–57.

[15] James E. Faust, “The Works of God,” Ensign, November 1984, 54.

[16] Joseph Smith, The Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, comp. Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 2002), 367.

[17] Marion D. Hanks, “More Joy and Rejoicing,” Ensign, November 1976, 31.

[18] Boy Scouts of America, Understanding Cub Scouts with Disabilities (Irving, TX: Boy Scouts of America, 1995).