Teachers as Torchbearers

Michael K. Parson

Michael K. Parson, “Teachers as Torchbearers,” ReligiousEducator 7, no. 1 (2006): 63–78.

Michael K. Parson was an institute director in Los Angeles, California when this was written.

I don’t know exactly when I developed the dream of being a teacher. I would like to think I was born with it, but I just don’t remember. I do remember when I developed the dream to be an Olympic runner; that started in high school. As I look back after over forty years, I can see how those two dreams have molded my life.

My earliest recollection of a desire to teach was also in high school. I remember talking to my sophomore math teacher, Mrs. Shearer, about wanting to be a teacher. And I recently discovered in my senior year high school annual, Hoofprints (we were the Mira Costa Mustangs), a note from my English teacher that said the following: “Best wishes for a successful career in teaching, and a happy future. Sincerely, Margaret Nicholson.”

I must have developed an early desire to teach religion too because I also have clear recollections of sitting in the high school stadium bleachers with a group of other runners and track club members during lunch time. Apparently we must have discussed religion on more than one occasion because I can remember one of my friends asking me, “Mike, explain to me again which kingdom I am going to.”

During my sophomore year, I tried out for football. There were four football teams; varsity, junior varsity, B, and C. I was fourth-string wingback on the B team. Following the regular season of games, since we still had to suit up for P.E. and do something physical, I began running with a friend who had just finished the cross-country season. The track coach saw me running and thought I had a good running stride and invited me to join the track team. Seeing that I had no realistic future in football, I decided to take up running.

My track season was less than remarkable, but I did well enough that a fire began to burn within—a love for running and a desire to run. It seemed to become the most important thing in my life at that time, and it began to consume me. I became totally dedicated in my workouts and eating habits. In fact, nearly everything I thought about all day long had something to do with running. If I wasn’t running or at least thinking about running, I was probably studying the Track and Field News. I had an insatiable appetite for the world of running.

I must confess that if it were not for this tremendous interest I am not sure I would have made it through high school. To be eligible to compete, I had to maintain at least a C grade average. This was very important because I had always had difficulty with academics in both grade school and high school. I was a very slow reader and only read what I had to.

In high school we were required to take yearly aptitude tests. They were referred to as the Iowa tests. Since I was a slow reader, it would always take me longer to answer the questions than most of the other students. To avoid the embarrassment of being one of the last to finish, I began answering a few of the questions, then randomly marking several, then answering a few more, then again marking several without even reading them. This solved the embarrassment problem since I was able to finish when about half of the other students did.

After the testing was completed, I forgot about the whole thing until my counselor called me in and advised me that due to my low Iowa test scores I should not plan to attend college but should try to learn a trade or some marketable skill. This was devastating. I already had a self-image that I could not succeed academically, and even though I knew the reason for the low scores, the counselor’s advice merely confirmed what I had believed for years—that I just couldn’t make the grade. I have often wondered if this incident may have given me greater determination to be a teacher, thinking that since there must be many other students like me, maybe I could somehow apply my experience to others and help them.

Mission

My bishop called me in to his office one Sunday and discussed with me the possibility of serving a mission. I knew I should go so I told him I would. Leaving his office, I had two major concerns. I was in excellent condition and felt I was well on my way to realizing an Olympic dream. I was concerned with what would happen to my dream if I went on a mission. Would I lose all that conditioning? Secondly, I had always believed that the Church was true but I had never read the Book of Mormon. I decided that if I was going out to teach I needed to know for myself.

For the spring semester of 1965, I decided not to attend school but to prepare for my mission by attending the institute full-time. Whatever class was being offered, I was there. When a class was not being taught I was in the library, reading principally the Book of Mormon and A Marvelous Work and a Wonder.

As I read the Book of Mormon for the first time, I was overwhelmed by what was happening to me. The Holy Ghost bore witness to me continually that what I was reading was true, that the people in the Book of Mormon were real and had lived here, and that Jesus Christ really had visited them. I now had a burning desire to serve a mission and share what I knew and felt.

I remember what my experience at the institute of religion did for me in giving me a great love for the scriptures, the gospel, and the institute program. I wanted to do for others what my institute instructors were doing for me. Great men such as Marv Higbee, Joe Muren, and Chess Gottfredsen, for example, were my heroes in a more significant way than Olympic runner Herb Elliott was, and I wanted to be like them.

My experience as a missionary only enhanced my desire to teach religion. On more than one occasion, after teaching a discussion and explaining a principle of the gospel, my companion seemed impressed and asked me where I learned those things. I told him, “At the institute!”

When I returned from my mission, I was again concerned that I had lost all my conditioning and worried how much of a setback this would be to my Olympic goal. To say that I was pleasantly surprised with what happened next would be an understatement. Within a few weeks after returning home, I was outrunning everyone on the college cross-country team! I was amazed. I had not lost it. I was still on track. All that tracting and bicycling paid unimagined dividends. I was happy, and I looked forward to my future, never imagining what twists and turns it would take.

Vietnam

When I returned from my mission to Canada in July of 1967, the Vietnam War was in full swing. While on my mission, we had been counseled by our mission president not to concern ourselves with world affairs, so I tried not to worry too much about it. However, after returning home, the Vietnam situation began to weigh heavily upon my mind. One thought that continually came to me was that thousands of young men were being sent over there and were going through severe hardships and trials and were making great sacrifices while I was relatively comfortable at home. I often thought, “Why shouldn’t I make a similar sacrifice?” This impression continued with me rather constantly through the fall semester at El Camino Junior College, and even after meeting my future wife, Terry Bickmore, I still had these impressions. I felt prompted (more than prompted—compelled) to enter the armed forces and go to Vietnam. The thought of going frightened me and I did not desire to go, but I honestly felt I was supposed to go.

While attending the fall 1967 semester, I received a letter from the Selective Service (draft board) inquiring as to whether or not I wanted a student deferment. The letter explained that if I chose to take one, according to a new law signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson, when I turned twenty-four I would be placed on the top of the list to be drafted.

I thought about this a great deal. At that time I was turning twenty-three and had no real commitments. I was not married or engaged; I was not in any certain program at school; and I had no idea what my situation would be when I turned twenty-four. These thoughts, coupled with the promptings and impressions previously referred to, led me to make my decision. I concluded to go to the Selective Service office and “volunteer.” This essentially meant they would put me on the top of the list to be drafted.

It was not long before I received my letter from the president of the United States. I was ordered to report to the induction center in Los Angeles on January 24, 1968. Following my basic training at Fort Lewis, Washington, I was sent to Fort Polk, Louisiana, for advanced infantry training. I had only been there a short while when the battalion commander spoke to all of the trainees in a large auditorium. His blunt message was that we were there to prepare to go to Vietnam and that we were all going. He said that many of us would not come back and that we needed to be prepared for that possibility. He told us that we should all write a will. His message was sobering, to say the least. We all knew that we were there to prepare for combat in Vietnam, but we assumed that some might go to Germany or elsewhere. It was very quiet as we exited the building and returned to our barracks.

This happened a few days before general conference of April 1968. I remember thinking, If I’m going to Vietnam and might not come back, then I want to go to conference before I go. Both Terry’s family and my family were already planning to attend conference, and I was determined to be there also. Based on what was said to us in that auditorium, I felt sure I would not be denied the opportunity to attend a “religious retreat” before going to war.

I asked my company commander for permission to go, but my request was denied. He said the training was too important for me to leave even for a weekend. I expected that response, but I had a plan. I asked to see the battalion commander, knowing my company commander could not deny that request. As he handed me the pass, he said, “All right, go ahead and see him.” Then he added, “But it won’t do any good.”

As I left his office, I was quite confident that I would get permission. I believed there was not a chance of being denied at the next level since the officer I was about to see was the man who had given the sobering speech.

I walked into his office, saluted him, and introduced myself. I had barely made the request when he said, “Oh, sure; that would be a good experience for you,” and he signed the papers. I was in and out of his office, with a smile on my face, in less than five minutes.

Terry and I had a great time visiting both of our families, attending my missionary reunion, visiting places in Salt Lake City, and attending conference. During that weekend one of the most significant events of my life took place. On Saturday, April 6, 1968, I asked Terry to marry me. She did not give me her answer then, but the next day as she and her father took me to the airport, she told me she had prayed and had received confirmation from the Lord and would marry me. I finished my training, and after a very short two-week leave, during which we announced our engagement, I was off to war.

When I arrived in Vietnam, I was assigned to the First Air Cavalry Division, stationed outside of Quang Tri, near the demilitarized zone. Word came to us that my company had made contact with the enemy and that a firefight was going on. I remember thinking, How did I ever get into this? Because of the enemy contact, we were not able to go out that evening but waited till morning—I was relieved!

When I arrived the next morning, I was greeted by my new company and surroundings. Many of the guys were lying around, some sleeping, others eating C-rations. They had surrounded a small village where some of the Viet Cong had been hiding. The inhabitants had been evacuated the day before, and rounds had been fired into the village all night. Later that day we marched through the village to inspect. Everything was destroyed, with bodies scattered here and there. This was my eye-opening introduction to the war, which caused me to conclude: “War really is hell!” The next eight months simply reinforced that fact.

Meeting with the Saints

One of the very positive experiences I had in Vietnam was associating with Captain Craig Cowley. Between the two of us, we organized Latter-day Saint Church services. He was set apart by the district president as the leader of our servicemen’s group, and I was his assistant. Since I had already gone on a mission, I would give one of the missionary discussions each week for a sacrament meeting talk. It was comforting to meet together as Saints and partake of the sacrament.

I suppose the best experience I had during my tour of duty occurred sometime later. I was riding in a large Chinook helicopter, which carried a lot of personnel, and sitting across from me was a guy who had BYU written on his helmet. I was excited to have found another Latter-day Saint, so when we got on the ground I asked him if he had gone to BYU, but he said no. I asked if he was LDS; he said no. I asked him why he had BYU on his helmet, and he explained that his girlfriend was LDS and was a student there. I asked how much he knew about the Church and if he had read the Book of Mormon. He said that he did not know much and that his girlfriend was going to send him a copy. I had my small servicemen’s copy with me and gave it to him. We became friends, and at night, after camp was set up, I taught him the missionary discussions. It was not long before he had gained a testimony and wanted to be baptized. By this time the entire First Air Cavalry Division had moved south to a location near the city of Tay Ninh. On the base at Tay Ninh was a rather large portable swimming pool. After David Moss had an interview and obtained permission to perform the baptism, I baptized him into the Church. We then went to a chapel nearby, where he was confirmed and ordained to the priesthood. It was such a contrast to be participating in the ordinances of the kingdom of God amidst war and wickedness all around. I am grateful to my Heavenly Father to have been given this experience.

Mortar Attack

Sometime in February 1969, I was assigned to be a radio operator on the helicopter pad of a forward landing zone. It was my job to communicate with the helicopter pilots when they approached the landing zone and find out what they were carrying and tell them where to land. I would actually show them where to land by throwing a colored smoke grenade to the landing spot.

Around March 18, 1969, after working on the helicopter pad on the Tracy for a while, the entire battalion moved back to Landing Zone White, where we had been a month before. When we first arrived back on Landing Zone White there was no bunker for the radio operators. The first few nights we slept in the supply tent while we slowly built a bunker in our spare time.

On the night of March 20, 1969, I retired as usual to a cot in the supply tent. I was awakened about four o’clock in the morning by the sound of explosions and flying debris. The first thing I did was to get down on the ground. We were in the middle of a mortar attack!

After a few minutes, a mortar landed near my feet. I was sure my legs had been blown off because the pain was so excruciating. I screamed and screamed. After a moment or two, I gained control of myself and looked down at my feet. I realized they had not been blown off but that the mortar had sprayed my lower legs with fragments.

I called for a medic, not thinking that a medic wouldn’t be foolish enough to run around in the middle of a mortar attack. While I was lying there on the ground, I could hear the screams of others who were wounded also. I clearly remember one young man scream, “My eyes, my eyes! I can’t see.”

I distinctly remember offering a prayer at that moment. I asked the Lord to please not let me die in that land but to please let me go home. Even if I had to lose my legs, I did not want to die in Vietnam. I asked Him to please spare my life, and if He did I promised to always put the Church first in my life.

Within moments, perhaps only seconds, I heard a sound that brought me great relief. It was the sound of helicopters, Cobra gun-ships. We called them the ARA, for Ariel Rocket Artillery. They were equipped with rockets and miniguns, which could spray a football field and not miss much. I knew that the attack was over because at night when the mortars fired there would be a flash that could be seen from the air. So as soon as the enemy heard the helicopters, they quit firing.

Once the attack had stopped, a medic got to me, gave me a shot of morphine, and started bandaging my legs. I was carried to the aid station, where the doctor was checking others who had been wounded. I remember him reprimanding those who were bringing in the casualties, telling them to leave the dead ones and bring in only those who were still alive. When I was carried in, I noticed that all around the inside of this hospital tent were wounded men.

About 4:20 a.m.—all this happened in less than thirty minutes, although it seemed at the time to be hours—I heard another helicopter. This time it was a medevac. When it had landed, I heard the doctor say to them to get the most seriously injured out first, and then he pointed to me and said, “Take him first.”

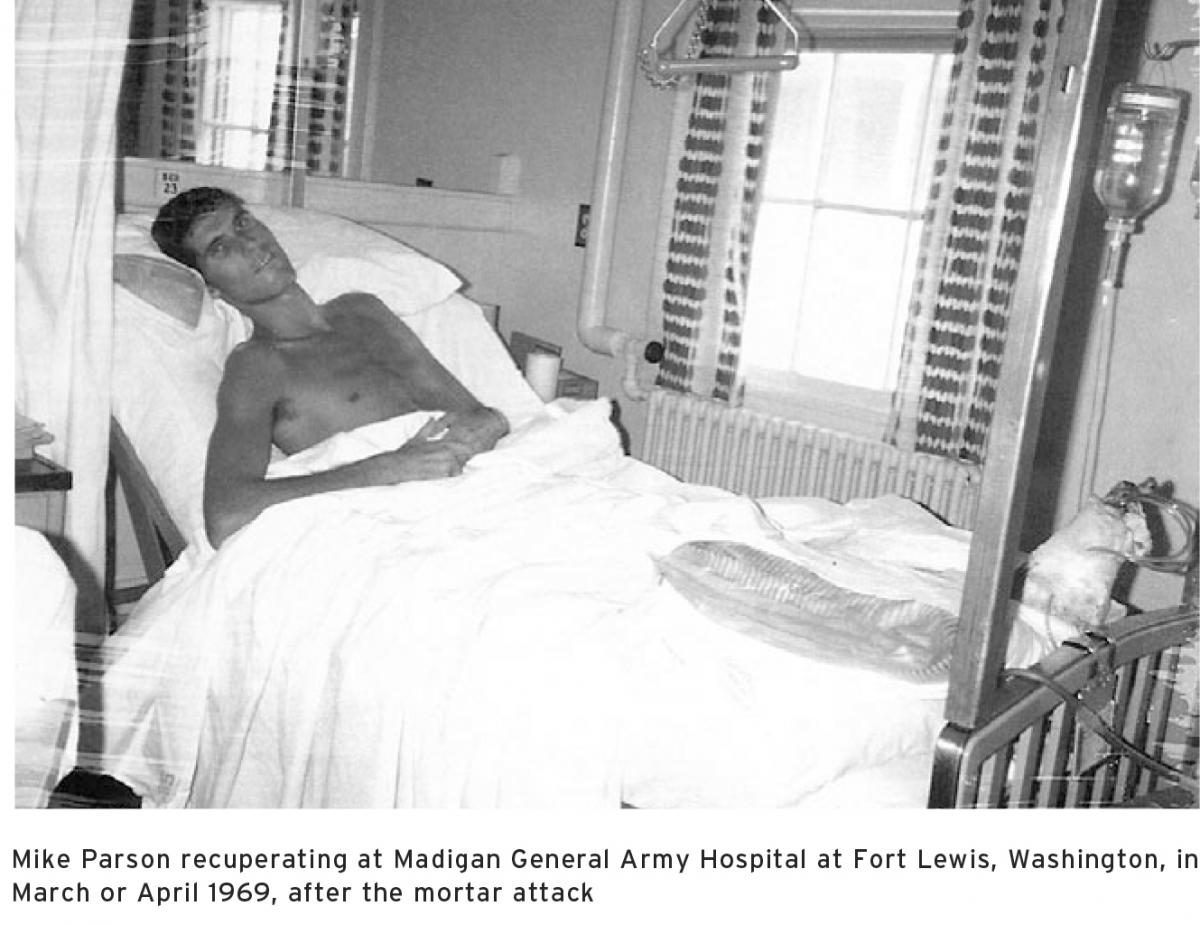

I woke up the following morning in a hospital ward, with a full leg cast on my right leg and bandages to the hip on my left. I asked a nurse what damage was done—she wouldn’t tell me. Soon a doctor came and told me I had a broken leg. I remember thinking, That’s not too bad! Lots of people get broken legs. I felt greatly relieved and encouraged by this report. It seemed to assure me that I would be able to run again. That same morning some officers came to see me. There at my bedside they thanked me for my sacrifice and gave me my purple heart without much ceremony.

I was at that hospital for only a short time. I was told that because of the danger of infection they did not want to close up serious wounds in Vietnam, so they sent me to a hospital in Japan. I remember thinking as we flew out over the ocean that for me, the war was over!

Soon after I arrived in Japan, I was taken into surgery. Up to this time I was under the impression that the extent of my injuries was a broken leg. When I was taken into the operating room, they gave me a spinal so I would not feel any thing from the waist down. They had also, however, hooked up an IV with a syringe of sodium pentothal attached, ready to inject if needed. A towel was draped over my waist so I could not see what they were doing. I was to be awake for the operation. They could see that I had some concern about being awake for the surgery, so they poked my legs with a pin to show me that I could not feel any pain.

I remember that while they were scrubbing down my legs to make them as sterile as possible, they made the mistake of raising my right leg up high enough for me to see my right foot. They could tell from the heart monitor that I had gone into shock. As soon as I saw it, all I had time to say was, “I saw my foot,” before they immediately gave me the sodium pentothal. Within seconds I was out.

I now had a clearer indication as to the seriousness of my wounds. What I saw looked like a scene from a horror movie. All I saw was bone, tendons, and raw flesh. The entire top of my foot had been blown off. In that second I knew that I had something far more serious than a broken leg.

From the moment I awoke and for several days following, I was greatly depressed. Prior to the surgery I had written home that since I only had a broken leg there was nothing to be overly concerned about. Now I feared that I would never be able to run again.

I was sent back to the States with more surgeries at Madigan General Army Hospital, at Fort Lewis, Washington. The doctors there had suggested the possibility of amputation before my medical discharge and transfer to the Long Beach Veterans Affairs Hospital.

Early in 1970 following my discharge, I had just about concluded that amputation was probably my most reasonable option. My right ankle was fused in a “drop-foot” position. I felt very handicapped, and medical science had not given me much hope of being otherwise. However, before giving up my foot, I needed additional medical advice. In checking around, I was informed that the foremost amputee clinic was at University of California Los Angeles. I made an appointment for a consultation. I wanted to know if I would be better off medically with or without my foot. The doctor studied my x-rays and other medical records, and made the following conclusions: I had severe bone damage, with the ankle fused in a drop-foot position; I had severe nerve damage, with no feeling on the top of my foot; and I had severe circulatory damage, which would lead to serious problems in the future. He strongly advised amputation.

Sometime in May of 1970 I was again wheeled into surgery, this time for the amputation of my right foot. It was taken off about seven inches below the knee, and with it was cut away my dream of ever running again.

I suppose if it had been taken in March of 1969, it would have been a greater shock and a more difficult adjustment for me. Since I felt that I had the ability to compete in the Olympic Games, to awake and find my foot gone would have overwhelmed me. However, by May of 1970 I was resigned to the fact that if my foot was not amputated, I would be even more handicapped for the rest of my life. It was my choice, and I have never regretted my decision.

A Slow Recovery

I have always felt very grateful to have been blessed with Terry as a companion. She was an anchor, a great stabilizing influence, and source of strength during those first couple of years, and has been since. I have observed that many other wounded veterans did not have a loving wife, a family, and a church, and they did not adjust nearly as well. I am aware of a young man who lost both legs and did not have the support of his family. He tried to commit suicide twice and succeeded the second time.

From May of 1970, I had many adjustments with many months of therapy, but after a few setbacks I was fitted for an artificial leg. It was awkward at first but also exciting to be able to walk again. Gradually I could do it easier and longer and with less pain.

I used crutches at first; then, after a while I used a cane. Gradually I used it less and finally got around without it. I was very fortunate to be able to walk as well as I did. From that time until now, unless I’m having some discomfort or a fit of illness, most people cannot tell that I am wearing a prosthesis.

My hardships and trials since March 21, 1969, have often caused me to reflect upon Joseph Smith’s experience in Liberty Jail, where he pleaded to know why he and the Saints were suffering so much. Part of the Lord’s answer, as recorded in Doctrine and Covenants 122, has always intrigued me. After recounting many of the terrible things which had already happened to Joseph and referring to some worse things that could happen, the Lord made this profound statement—”Know thou, my son, that all these things shall give thee experience, and shall be for thy good” (v. 7).

As I have read over this statement and wondered how this could be, I have thought back over my own life. When I went to Vietnam, I considered myself to be a good person. I was a returned missionary and active in the Church. I believe I would continue to be active without this trial in my life. Yet, I know that I am a better man today because of my experience. I am not sure of all the reasons why this is true; I just know it. And so, as I look back on this entire experience, there are two facts that stand out in my mind that I am sure of: I was supposed to go to Vietnam, and I am a better man and a better teacher because of that experience.

Each day as I feel pain due to my prosthesis, I am constantly reminded of the commitment I made to the Lord while lying on the battlefield of Vietnam—that I would always put the Church first in my life. I fully realize that in a sense I was bargaining with the Lord. I also fully realize that I had already made that promise when I was baptized and that I have renewed that promise thousands of times as I have partaken of the sacrament. And I also realize that I may have lived anyway, without making the promise. Nevertheless, my life was spared, and I did make the promise, and I intended to keep it.

Back to School

I was a bit apprehensive in starting back to school. My academic history was nothing to be proud of. I had been on extended probation—academic disqualification—and now after two and a half years I was coming back on probation.

But this time I had some advantages that I did not have before. I was now much older and, I hoped, wiser. I had gained the experience of a mission; plus, my military and war experience had a very maturing effect upon me. One additional factor that made a great deal of difference was the fact that I was married. I have often thought that it is one thing to come home and tell your mother that you are failing in school and quite another to have to tell it to your wife, who is working so you can go to school.

At the end of my first semester, I received a letter from the college. I thought, Oh great, here we go again. But then the thought came, My grades couldn’t have been that bad. When I opened the letter, I was shocked to read that I had made the dean’s list. I first checked to be sure it was addressed to the right person. The dean’s list! Nothing like that had ever happened to me, but it completely changed my academic future. I never again had a poor grade in school, and I eventually earned three college degrees; a bachelor’s, master’s, and a Juris Doctorate. I would love to have the opportunity to see my old high school counselor now. I would like him to see my grades and degrees so that he might learn the principle, “Never write anyone off!”

While I was in college, I taught three years of early-morning seminary, which again fanned the flames of my teaching desire. While doing so, I went through the Church Educational System (CES) preservice program with A. Paul King, my mentor. After completing the preservice program, Paul recommended me for hire. However, he explained that the Church was going to fill all of the overseas assignments with indigenous personnel and that the American personnel would be brought back to fill any vacancies here in the States. That meant that my chances of being hired were almost zero. Paul advised me to look for something else, but if I still wanted to try again the following year he would recommend me. I was extremely disappointed. I had been looking forward to this for years, but now my dream was beginning to fade right before my eyes.

The vice president of personnel at Western Airlines lived in our stake. He invited me to come in for an interview. When I was getting ready to go, I had an impression like, “Why are you doing this? You’re supposed to teach in CES.” I went to the interview and was offered a job to start right away. I told them I could not start until June (this was April), when I would graduate with my bachelor’s degree. They told me to come back then and they would hire me.

Determined as ever to get into CES, rather than take the job, I began a one-year master’s degree program. I still felt quite discouraged, not being sure I would get hired the next year either. I remember writing a letter to Frank Bradshaw, in the central office, explaining my situation, and hoping he could be of help. He wrote me an encouraging letter but could not make any promises.

The following year I was hired to teach released-time seminary in Mesa, Arizona. During that first year, I saw how my fellow teachers were struggling to work on their master’s degrees and how relieved I was not to have to worry about mine. I quickly realized how fortunate it was that everything had worked out the way it had. My great disappointment in not being hired the year before turned out to be one of the great blessings of my professional career.

Through many years of teaching, I greatly missed running. Whenever the Olympics were on television, it would be too difficult to watch the track events because that is what I wanted to do, and I knew I could not. But after seventeen years, I began to hear of new developments in prosthetics. I made some inquiries and eventually was fitted with a new leg designed for running.

On a quiet Saturday morning, on the playground of the elementary school my children attended, I had another life-altering experience that placed me on a thrilling new path. For the first time in seventeen years, I actually ran. It was not a skip or a hop but an actual running stride. I was anxious to pursue this new-found freedom and thought I would gradually start running on a regular basis.

About that time I received a letter from the U.S. Amputee Athletic Association. I did not even know there was such an organization. They were inviting me to attend the upcoming National Championships in Nashville, Tennessee. I thought how much fun it would be to run and compete again. The problem was that the event was in six weeks, and I had not even run in seventeen years. There was no way that I could get into shape in that amount of time. Plus, being a law student I couldn’t afford to make the trip to Nashville. So I decided to forget about it.

But I couldn’t forget about it. I was aware of the winning time in the two-hundred-meter run in the previous year’s competition: thirty-five seconds. I decided to have a time trial to see if I was anywhere close to that. I ran it in forty-two seconds. Not good enough, I thought, and again decided to forget about it.

But I still couldn’t forget about it and decided to have one more time trial. This time I ran it in thirty-eight seconds! The following Monday I met with my prosthetist and told him I was planning to make the trip. I asked him if he knew anyone in any service clubs in the community who might be willing to sponsor me. He said he did not and left the room. When he returned, he handed me a check for one hundred dollars. I knew that a door was being opened for me to pursue this.

Now, with only three weeks to train, I did as much as I could. I competed in the two-hundred-meter race and got third place, running it in thirty-four seconds. I also took second place in the four-hundred-meter race. I thought, If I can do that in only three weeks, what could I do if I trained all year?

The following year I did well enough to qualify as a member of the U.S. team to compete in the Paralympic Games in Seoul, South Korea, following the Olympic Games. These were to be held in the same facilities used by the Olympic athletes.

The Paralympics are, essentially, the Olympic Games for disabled athletes. It is an elite competition to see who is the best in the world among different levels of disabilities, amputees being only one of the disability groups. It was a thrill to represent the United States in an international competition. When the team would arrive at Olympic Stadium, school children would flock around us and ask for our autographs or to have their pictures taken with us. I felt like Carl Lewis!

Through these experiences I have learned that even though our dreams may have been blown apart by catastrophic circumstances, the Lord has a way of helping us to realize those dreams in ways we may not have imagined. If someone had said to me a year before I began to run again, “Mike, in a couple of years you’ll be in Olympic Stadium, competing in an international track competition,” I would not have believed them. But there I was, in the Olympic Stadium in Seoul, Korea, in 1988. It is truly amazing how the Lord works.

We all have some type of disability. Some disabilities physical, but many are not. We all have spiritual disabilities. I do not think that the Lord is nearly as concerned with what our disabilities are as He is with what we do about them. With the Lord’s help, we can make more out of our lives than we ever thought possible. He can help us to overcome our disabilities and realize our goals and dreams.

After the Paralympic Games in October 1988, I essentially retired from my “running career” due to some pain I was having in my leg. I could not run one hundred yards without severe pain. I eventually had surgery, but that did not solve the problem, and rather than undergo additional surgery to try to improve the situation, I just resigned myself to not running again.

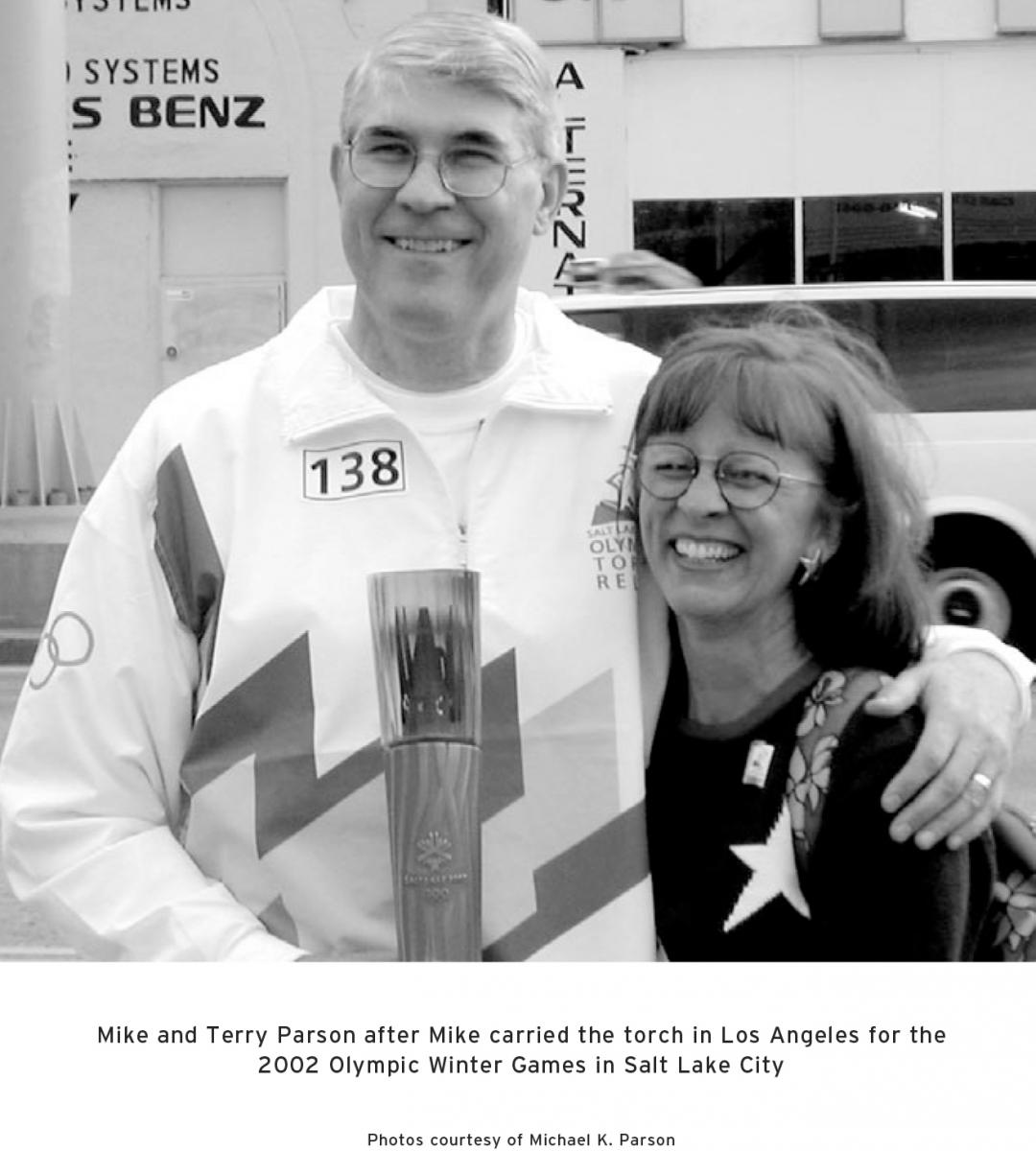

Olympic Torch Relay in 2002

Approximately ten years later, as the 2002 Salt Lake Winter Olympics approached, something happened that is an epilogue to this story. Chevrolet and Coca Cola, as the sponsors for the Olympic torch relay, invited the public to nominate individuals who might have inspiring stories and who could be considered good candidates to carry the Olympic torch. Unbeknownst to me, my wife and children submitted my name. When I finally found out what they had done, I asked them why and said, “I can’t do that!” The idea was exciting on the one hand, but I felt fearful on the other. I knew I could not run with the torch, and I thought, What if they pick me? What will I do? My wife thought that the names would be selected randomly and that I was only one of many thousands. She tried to comfort me by saying, “Oh, don’t worry; you’ll never get picked!”

While we were in Nauvoo, Illinois, on a Church history tour in July 2001, my daughter called with the news that I had received a letter from the Salt Lake Olympic Committee. I told her to open it and read it to me. It was from Mitt Romney, inviting me to be a member of the Olympic torch relay team. I felt overwhelmed by the honor but still wondered what I would do. When we returned home, I went to see my orthopedic doctor, Paul Gilbert. When he walked into the room, I said to him, “Dr. Gilbert, of all the orthopedic doctors in southern California, you have been chosen to perform a miracle!” He just smiled and asked what I was talking about. When I told him, his smile broadened. He was very excited at the prospect. He said it was quite common to give a shot of Marcaine to athletes who were in pain, which would give temporary relief and allow them to continue competing. He thought we should try it and see if I was able to run. It was successful enough that I was able to carry the torch through the streets of Los Angeles, just a few blocks from my institute at USC. Being able to carry the Olympic torch was truly a thrilling experience.

The Torchbearer

There are some great principles related to carrying the torch. I was privileged to be one of the many to carry the Olympic flame as it traveled throughout the United States. What a thrill to know that I was representing not only our country but the entire world as I carried the flame. Even though there were thousands of torchbearers, for that one moment in time, I was the Olympic torchbearer.

The purpose of the torchbearer is to run through the community, lighting the way and announcing to all that the Olympics will soon begin. Since then, I have thought how in a very real way all of us are torchbearers. In our own special way we have the responsibility of carrying the light of the gospel to a darkened world and announcing, “The Restoration has taken place; Christ will soon come, and the Millennium will begin!” Think of what the scriptures tell us about being torchbearers: “Therefore, hold up your light that it may shine unto the world. Behold I am the light which ye shall hold up—that which ye have seen me do” (3 Nephi 18:24). “Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in heaven” (Matthew 5:16).

Teachers as Torchbearers

All of us are in a position to light the way for our students. For this moment in time, in your own sphere of influence, you are the torchbearer. May you hold up that light, that Jesus Christ may shine unto the world.

And now, after thirty years of teaching, I realize that I am approaching the end of my formal career. As a torchbearer of a different sort, I’d like to feel that I will be passing the torch, the flame and passion for teaching, on to the rising generation of teachers who will carry it for a short distance until it will be time for them to pass it on. May they let their light so shine before their students that their students will see the goodness of the message they bear and the truthfulness of their teachings, causing their students to glorify our Father in Heaven.