BYU–Hawaii: A Conversation with Eric B. Shumway

Fred E. Woods

Fred E. Woods, "BYU-Hawaii: A Conversation with Eric B. Shumway," Religious Educator 6, no. 3 (2005): 1–22.

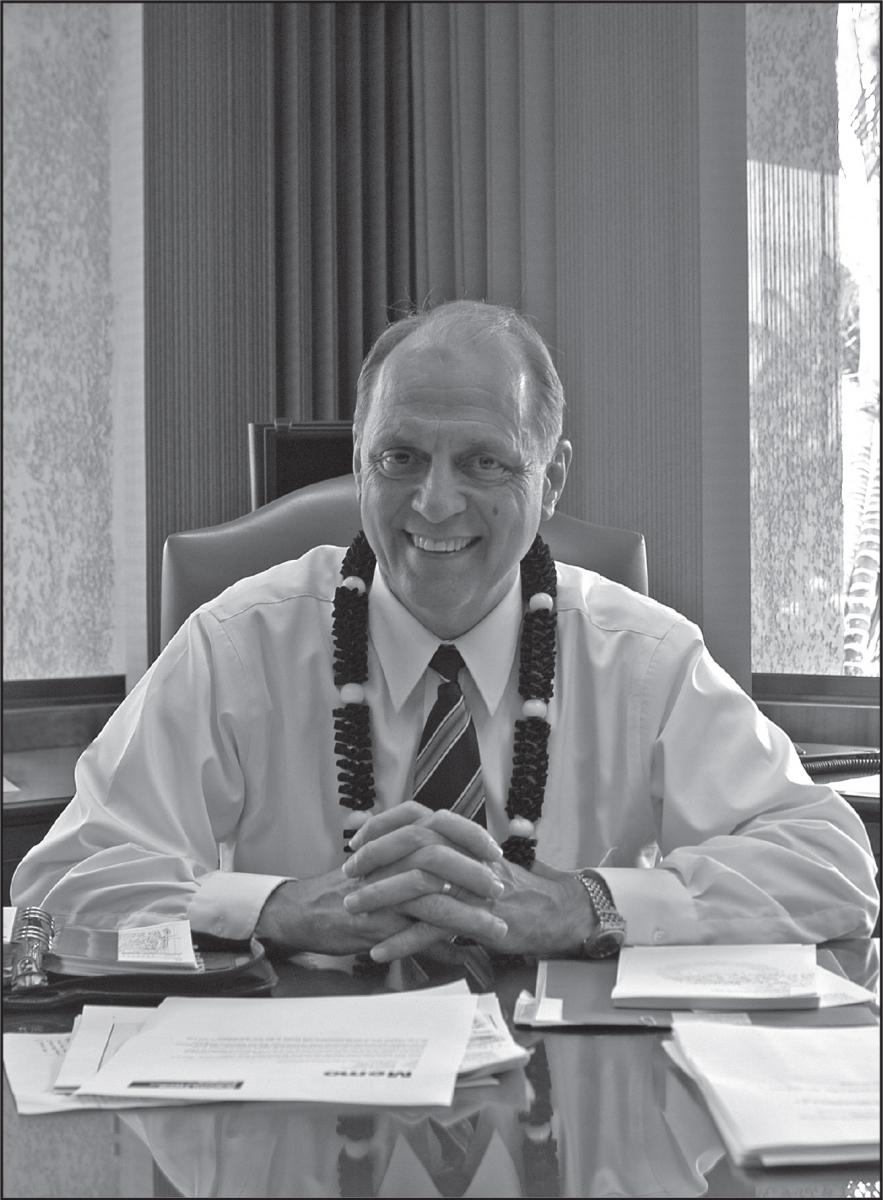

Eric B. Shumway was president of BYU–Hawaii when this was written.

Fred E. Woods was a professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU, Provo campus when this was written

President Eric B. Shumway. Photographs by Akiko Sawada. Courtesy of BYU-Hawaii

President Eric B. Shumway. Photographs by Akiko Sawada. Courtesy of BYU-Hawaii

Woods: I am meeting with President Eric B. Shumway in his office in Laie on August 6, 2004, and I want to provide a brief life sketch of President Shumway. Born in 1939, he grew up in St. Johns, Arizona. In 1957 he was voted the most valuable player in the high school all-star game in the state of Arizona. In addition, he had an athletic scholarship at BYU, Provo, and played basketball there before serving a mission to Tonga. He received a bachelor’s and master’s degree from BYU in English (1964, 1966) prior to serving as a language coordinator for the Peace Corps. He wrote the Tongan language text for the Peace Corps (1967-68), which was later published by the University of Hawaii. In 1973, he received his PhD from the University of Virginia. He served as a bishop, a stake high counselor, and the first BYU–Hawaii stake president, a position he held prior to being called as a mission president to Tonga in 1986. He is the eighth president of BYU–Hawaii. He has been serving in this capacity for the last decade, and in addition, is serving as an Area Seventy. He is married to the former Carolyn Merrill, they have seven children and twenty grandchildren.

President Shumway, as a child or youth in your home, what were some of the most valuable lessons you learned that shaped your behavior as an adult?

Shumway: A thousand things touched my life in the little community where I grew up, but if I were to pinpoint a few, I would say that one of the fist is associated with my getting up early every day. I had responsibilities early in the morning—to milk the cows and do the chores—rain or shine, cold or not. Of course that was so commonplace a few years ago in rural communities, but the fact that I loved to get up early and loved to get going early has made a big difference in my life. I enjoyed learning to work and doing whatever it took to get the job done rather than simply spending time. If we have a task that needs to be done, we shouldn't merely think in terms of hours or energy or whatever it takes to get it done.

Another thing that helped me was having a father, Carroll Shumway, who taught me what a good job looks like. When he taught me how to work, he wouldn’t just say, “Do this.” He would show me what the end result would look like. For example, if he wanted me to weed an area, he would weed about half of it himself, and then he would say, “Now, this is the result I want when you get done. The whole area should look exactly like this.” So I had an order, I had a responsibility, and I had a model.

I'll share a little story that has become kind of a signature experience with my father. He managed two service stations, a Standard Oil and a Richfield service station, located at separate spots in St. John's. I worked hard for him, but it wasn’t for money. I got my first paying building fence and stretching barbed wire for a local rancher, Harbon Heap. We worked for maybe fourteen hours, pulling barbed wire, tying stays, and getting our hands were bloody. I was really looking forward to getting my first paycheck.

After the day was over, Mr. Heap wrote a check for each one of us. It was a real rush for me. For those fourteen hours of hard work I got seven dollars—fifty cents an hour. Man, I was so excited. But my buddies grumbled under their breath, “We worked that hard—for only fifty cents an hour?” By the time I got home, I was upset that it was only fifty cents an hour. I complained to Dad. I did not expect his response. He said, in effect, “Don’t complain. You may have deserved more. But that’s great. The day your performance exactly meets your salary is the day you disappoint your dad. You should work so no employer can pay you what you’re really worth.” I was impressed with his tone and attitude. When I was complaining I’d been underpaid, he was saying, “That’s good. I hope you have a lifetime of that so you’re always performing ahead of your pay.” That lesson stayed with me.

My mother, Merle Kartchner Shumway, was a public person and a very tenacious teacher, in school and in Church, she taught children to sing, dance, and play musical instruments. We had a very happy home full of music and love. Dad worshiped Mom. Mom had a college degree. Dad did not have the degree, but he was 100 percent supportive. People would sometimes ask, “Carroll, aren’t you ever jealous about all of the glory your wife gets?” He would say, “She is my glory. Her glory is my glory.”

I came home one night and Dad was in the kitchen. It was about 9:30 at night. He had worked long hours that day at the service station. He was still in his greasy Richfield uniform and he was doing Mom’s dishes. I was incensed and said, “Dad, why don't you make mom come home and do her dishes?” Mom was at choir practice, preparing for some upcoming event. Dad just turned to me and said, “Sonny, I can’t teach kids how to sing. But I sure as heck can do dishes. So quit your complaining about your mother and come help me do the dishes.” So I had the sense growing up that Dad really loved my mother and that Mother’s talent was a gift to the community. I also learned that even though Dad had a business to run, he was still very concerned about taking care of the home. He could cook and clean, and even change diapers. In fact, he told me once, “I’d be ashamed if a woman could do something that I couldn’t do–other than have kids.” That was kind of the atmosphere I grew up in.

Woods: What are a few of the important lessons you have gleaned from your callings at BYU–Provo or BYU–Hawaii that have left a lasting impression on you?

Shumway: I have learned may lessons, and most of them have to do with humility and love. I have learned just how precious students are in the sight of God.

I have witnesses how the Lord has guided students and faculty members to this campus. Nearly every faculty person has had some reassuring spiritual experience that affirmed that they were led to this campus for a special purpose. I have learned also to appreciate the several intellectual and spiritual gifts of colleagues, gifts far superior to my own.

I have been profoundly moved by the quality of service by faculty who were stricken by one impediment or another but continued to serve faithfully to the end. Some taught from wheelchairs, others fought terminal cancer. But as their health waned their spirits were purified and their influence for good became more profound. I'm thinking of Dr. Lance Chance, Dr. David Chen, Dr. Ronald Jackson, and others.

I have learned that a powerful intellect without a divinely anchored conscience can be a pestilence in the world.

I have come to understand that character and testimony constitute learning outcomes far more valuable than material success. I have also come to know that in the learning process love motivates and empowers more than fear or enticements of material reward.

I remember a student who left school just before she graduated to live with her auntie. One course remained for her to complete her degree. She had struggled from past scars and depression. She was allowed to take the course by independent study but not allowed to come on campus because of a serious honor code violation. Nearing the deadline for completing the course, she was unable to rally her spirits or concentrate on the course. It looked like she would fail and never graduate.

I mentioned the situation to one of our faculty members. He said, “Well, let me see what I can do.” He found the girl’s phone number, called her, and said, "Since you can't come on campus, I will meet you anywhere, anytime, to get you through this course, if you will let me." And, he did. He went way out of his way. He stuck with her and helped her, and she finally finished the course and got her degree. She's back on track now, married with four children. She is active in the Church, and a college graduate thanks to this teacher who extended himself. She was a wounded soul, lost in the desert, as it were, but retrieved by a loving conscientious teacher.

Woods: What are some of the tutorials that you have learned from the words or examples of modern-day apostles and prophets that have left an indelible impression on you?

Shumway: When I was a mission president in Tonga, Elder M. Russell Ballard came down to preside over two stake conferences on the same day in Vava’u. He invited me to go along with him. We started about 7:30 in the morning—held the leadership meetings, did all of the training, and the main session—and then we went to another stake and did the same thing all the way up to about 9:30 at night.

When we got back to the hotel, I was absolutely exhausted. I was in my pajamas ready for bed when a knock came at the door. It was my first counselor, Bill Afeaki, who said that Elder Ballard would like to see me in the grill. I said, “Are you sure?” He said, “Oh yes, he asked me to come and get you.”

I found Elder Ballard at the rill. He was talking to a man had had just met, standing in line to get a soft drink. The man was a “yachtie,” who was leaving the very next morning his yacht. Elder Ballard said, “Oh, President Shumway, so glad you could be here. This is John, and I’ve been talking with him about the gospel. I’ve asked him if he would like to hear the message, and he said yes, and I said he’s in luck because there’s an authorized servant of the Lord in this very hotel who is eager to teach him. Will you find a room somewhere in the hotel where you can pray with this man and teach him the gospel?” I said I would be absolutely delighted to do so.

That was a wonderful experience for me and for the man, but the thing that was indelibly impressed on my mind was that here was an Apostle, older than I was, who at the very moment he was exhausted and wanted a little bit of refreshment before he went to bed, was still talking about the gospel and asking the golden question. Now every time Elder Ballard speaks about anything, I perk up with an extra bit of attention, knowing that this man practices what he preaches.

Elder Ballard has been on our campus may times since them. I introduced him to Nina Mu, a Muslim student from Western China. A number of students had lined up to see him, but when I presented him to Nina, he turned around and whispered to somebody who was with him to run to the bookstore and buy his book, Our Search for Happiness. He wrote his testimony and signed it right there and gave it to her. He knew he may never see her again. As I think of that, I realize that Elder Ballard has a very public ministry of speaking at conferences, presiding at meetings and heading up important Church committees, but he also has a private ministry that he is very attentive too and he’s looking out for the souls of others. That is very important to him. By the way, Nina is now married with a child. She and her husband, John Foster, were baptized into the Church on July 4, 2005.

Another powerful experience was with Elder Philip T. Sonntag. He was in the Area Presidency in Australia when I was mission president, but he was also one of the leaders who interviewed us before we were called. Elder Sonntag is a bit rough-and-tumble guy, but he and his wife, Valoy, had the most amazing ability to distill sweetness and lobe on their audiences. After one BYU-Hawaii stake fireside, they invited the young people to come forward so that he and Sister Sonntag could get a look at them and give them a hug. What seemed like hundreds of students lined up, and every one of them got a big bear hug and a look in the eye and an “I love you.”

Many of these were international students who were homesick. Some had never experienced that kind of affection. A number of then just fell into Elder and Sister Sonntag’s arms and sobbed. The impression, the indelible impression, was that the Sonntags are blessed with the gift of expressing love. They were a conduit through which the lobe of Heavenly Father could flow. Their talks were excellent. They could have shaken a few hands, but that wasn’t enough for them. The Spirit told them that there were young people in the audience who needed more than that.

Another wonderful experience was with Elder David B. Haight. I one of the first Board of Education meeting I attended as president of the campus, he was invited to pray by President Hinckley. I had to make a presentation, so I was preoccupied with what I was going to say. Elder Haight stood and prayed. Now we know that leaders pray many times a day to begin and end meetings. But to hear Elder Haight was to hear a pray that went beyond that particular setting. He poured out his hear to Heavenly Father pleading for the young people of the Church, and then he went beyond the stewardship of the church Educational System to the whole world. I dropped whatever I was thinking and just concentrated on the prayer of this wonderful man. As he was praying, the thought occurred to me, “We meet to pray. Whatever else is on the agenda, we meet to pray. And then we talk and then we pray again, and everything we do, we do in that special format of prayer, beginning and ending.” I learned the importance of listening to prayers, of making them my own personal prayer, repeating them in my mind as we learn in the temple.

Another time Elder Robert D. Hales called me and said, “I’m going to be in Laie for a day or two. Would you mind inviting all the religion faculty and their wives together for lunch so we can enjoy each other and have a discussion?” I did it. I was thinking, of course, that I would call these people together and Elder Hales would give a wonderful talk.

Instead, the opposite happened. When the luncheon was over, he said, “Now, you are some of the finest teaches in the Church. You have had years of teaching experience. Will you share with me those things that have been most successful in your teaching. How do you reach the minds and the hearts of young people?”

At first there was a bit of hesitation among this group, but soon they started talking, while he took notes. The Spirit was present as they teachers shared their ideas. He also invited wives and secretaries to offer suggestions and many good ideas were shared. In the end, Elder Halves stood and gave the sweetest thank-you expression. “You know, next week I have to teach missionaries at the MTC how to teach. I just wanted to consult the experts today, and you have provided me with a lot of ideas. Thank you very much.” (He had about four pages of notes.)

Woods: What humility

Shumway: Yes, that was very toughing to me. Elder Joseph B. Wirthlin visited us in Tonga and expressed the same kind of humility. He said, “Now, President Shumway, this is the first time I’ve been in Tonga. Tell me about this place. You need to make sure that I don’t commit any gages—that I don’t do anything inappropriate. You need to guide me. There’s and air of sweetness about that. Of course, I was very gentle in how I guided him because I didn’t feel like he needed much guidance, but I was impresses that he would recognize his newness and that the apostleship, even though it meant authority and responsibility, did not mean he automatically knew everything. He was an eager leaner—the same way Elder Hales wan an eager learner.

Woods: What general advice would you offer to instructors in Church-sponsored institutions or to teachers in ecclesiastical settings that would enable them to be more effective in the classroom?

Shumway: I would offer the following suggestions. First, we must always remember feeling that as teaches we are in the service not only of our students but also of the Master Teacher Himself. The entire thrust of our teaching, whether by word or example, must be calculated to draw “all men” (our students) unto Christ. Preparation through study and prayer is essential.

The Lord admonishes us to “seek, knock, and ask.” Besides seeking knowledge of content and teaching techniques, we need to see, “knock, and ask for the ability to see and discern each student as God sees and discerns that student. We need to have God’s love as well as God’s perspective of those whom we teach. So many times we see students only in their irritating or naive adolescents. We should see them as God sees them, in their divine potential. We should see them as they are going to be in twenty years, see them both in terms of the lord’s expectations and the challenges they will have to face. I have encountered former students who are doing absolutely amazing things now—things I never would have guessed when I knew them twenty years ago. As I meet one of them I say, “Oh, so you’re so-and-so.” And then I remember, “He’s the student who always goofed off in class or who performed below expectation or irritated me by off-the –wall questions.” But now he’s doing this wonderful thing. If I had only seen what he was going to do and be, then I might have been a little more conscientious. I’d have been a little more attentive to his needs.

Second, keep your eyes and ears open beyond the lesson. I remember Elder Henry B. Eyring saying, “Do something for the students besides simply talking to them.” Talking, discussion, and even bearing testimony—all those are very important—but do something for them beyond threat. Go the extra mile in some way. I remember an experience I had at the University of Virginia in graduate school working on my PhD. I had just humiliated myself by giving a poor class report in a seminar. I felt it was a real flop, and I was still in shock. The following weekend, I received a phone call from my professor. It was about 5:30 Saturday afternoon. He said, “Mr. Shumway, I thought you’d like to know you just received n A on you r paper. I thought knowing that might make your weekend.”

What occurred to me was, first, he knew his call would indeed “make my weekend.” Second, I think he was still feeling for me because of my embarrassment in class. His call was his way of remaining completely professorial but showing compassion proactively. For me, the clouds parted and the sun shone. This was the professor who spent the first thirty minutes of the first day of class going through this funny little routine of memorizing our names. He was kind of a bouncing ball. But after that day, we were all on a name basis with him. The importance of that stayed with me.

So we must see students as God sees them, and so things for them beyond the expected. Also w must never forget that the influence and power of one’s life is often greater than the power of the lesson and the discussion—the personal worthiness that shines through the countenance, the tone of one’s expression, the body language.

Years ago, I home taught a man who abused his wife verbally and emotionally. They were on the verge of divorce. One day I confronted him saying he had cut himself off from the Spirit. “How can you say that?” he argued, “I walk into my class and the Spirit is so strong everyone feels it. And those kids, they are in tears. They are just thrilled. I can’t keep the Spirit back.”

This man was truly skilled in what Mark Twain called “getting up an effect.” He could generate a thrilling performance including student tears. But I believe there is a difference between a person who is truly righteous land living the gospel so the Spirit though them can communicate truth, and a person who in a moment of acting can create a tearful emotion or a sensation. The one is divine instruction; the other is priestcraft.

I’ll never forget a moment at BYU-Provo when I was taking a course from Brother Rodney Turner. He was an intellectual, spirited kind of guy. The “argumentative edge” was often present in his lectures and in the student responses. He said things interestingly and provocatively. One day in the middle of a lecture, he suddenly stopped in his tracks and said, “Brothers and sisters, I feel that I should like to bear my testimony.” It was kind of out of the blue. He bore the sweetest, humblest, most powerful testimony. The thing that touched me was that his action was not orchestrated. It just happened; the Spirit touched him maybe for some person or group in the class. The effect was very powerful.

I also remember listening to a talk by Leonard Arrington in which he did the same thing. He was giving a scholarly paper when suddenly he stopped and said, “I feel like I must bear by testimony.” In that testimony, as I recall, he said, “All of my experiences with Church History, everything I’ve looked at, everything I’ve read, everything I’ve touched, all of it fits so nicely. And I have found nothing that would affect my testimony negative in any way’ in fact, it’s the opposite.” Perhaps it was the surprise that moved me so much.

Every teacher essentially needs to be in tune with the Spirit and with the Spirit’s timing, to bear testimony so that every young person knows without any doubt how he feels and how he knows the Church is true.

Don’t be discouraged by bored and solemn faces in the classroom. Something is sinking in. I learned that over and over again tin teaching religion as well as English. I think about the story President Hinckley told recently about his experience back East as a young Apostle. He came away from a stake conference feeling that he was a failure. But a few years late he met a man who was transformed, whose life was changed by his address in that conference.

Keep track of the stores you tell in classes so that you don’t repeat the same ones from course to course. Students remember them and when a teacher changes or embellishes, particularly a personal narrative, a disconnect occurs and students become cynical. Avoid teaching the “same course” by telling the same stores from course to course. Also, as we should avoid gospel thrillers for sensations sake, so should we confirm spiritual events that we share with our classes. When in doubt, leave it out, especially when the narrative tends to aggrandize the teller.

Help students love the scriptures and use them to solve problems. Scriptures are the handbook of life. Help students understand that the scriptures are a truly relevant, pertinent guide for action today. I think students need to know that the scriptures themselves are a miracle. We have a whole library right there in the standard works—annotations, indexes, cross-references, and maps.

Make sure you come prepared for class. An unprepared teacher, a “winger,” is often a plague in the classroom. A story is told of a very bright student who was goofing off in class. Irritated, the teacher said, “Billy, when are you going to come prepared to class?” Billy looked at him and said, “I will if you will.” As the teacher was telling the story later, he said, “First I felt a flash of anger, but then there was a moment of enlightenment, and I realized Billy was right. So instead of kicking him out, I said, ‘Billy it’s a deal.’” The teacher was true to this word. He said, “After that, I came prepared—overprepared—and made sure that everybody knew I wars reading new things.” Be sure you teach a class in a way that makes it very clear to the students that you’ve reviewed this material, that you’ve brought additional things into the lesson, and that you’ve thoroughly prepared the lesson. Of course, be open to how the Spirit may guide you to depart from your preparation.

Keep an eye out for the underdog: Don’t let any student get lost. On our campus, we have students from all over the world. Many of the struggle with English, which is their second, third, or fourth language. Their lack of proficiency is humiliating to them. They seek the shadows in the classroom. Our job is to help them perform in the light, as it were.

One of my favorite courses to teach was Introduction to Literature for non-English majors, a General Education course that was scary to a lot of international students who had never taken literature before. I tried to make it as fun a s possible, including having a dinner at our home at the conclusion of our section on poetry. This section focused on love poems. One of the requirements was that they each write a love poems to recite the night of our little banquet. One of my Fijian students was absolutely incensed. “I can’t do this. I’ve never done it before. It’s English. Why don’t you let me do something else?” I wouldn’t let him off the hook, saying, “No you will write a love poem in English. Are you married?”

“Yes.’

“Well, you know something about love then. I’ve never met a Polynesian who wasn’t a lover in some way.”

When we gathered at our home, each student presented his or her composition, including the reluctant Fijian husband. Eh entitle his poem, “My Laie Morning.” It was a tribute to his wife, who was sitting right there. He read it with feeling and with intelligence. Later that evening his wife said to me in tears, “President Shumway, I don’t know what grade you’re going to give my husband on this poem, but I just want you to know it has saved our marriage.”

Woods: What does it mean to love the Lord our God with all our mind in an academic setting?

Shumway: One way to love God with all our mid is that we unleash the powers of imagination and analysis in the service of the Lord. When you consider the mental and intellectual energy that successful people put into a business or a hobby, I think we should give that much intellectual vigor and more to a Church assignment or Sunday School class preparation. More than that, we must remember that to love God with all our mind is to love His nature with all of our mind, the majesty of His goodness, the magnitude of His eternal love for us as His children, and the extent of His mercy. I believe a fully engaged intellect and imagination in exploring that majesty is vital for us, not just as a mental exercise but as a sincere, full-minded striving to become as He is. For to understand God fully is to be like Him (see 1 John 3:1-3). This final realization is the ultimate objective of His plan of happiness for all of us.

I suppose we serve God best in an academic setting wen we are in the service of truth and when we help young minds to hunger and thirst after truth, guided by the revelation of God and the counsel of living prophets.

Woods: President Shumway, members of the Kirtland School of the Prophets were told to “seek ye out of the best books words of wisdom” (D&C 88:118). As a former BYU English professor and now as president of BYU-Hawaii, what do you think are some of the best books we should be seeking after?

Shumway: I don’t have a list of the “best” books, but I do believe the best books are the books of scripture. In my mind, everyone needs to thoroughly immerse himself or herself in works of scripture—not just in doctrine per se but even in the language and the stories. The scriptures have some of the most magnificent stories that are truly at the center of human existence.

The older I get, the more I love to read biographies to learn about the lives of great men and great women. It is now a personal requirement for me that any book I read must contain materials that will fill me spiritually and expand my vision and lobe of humanity. Years ago, as I was contemplating a dissertation topic, I decided to concentrate on a person whom many people had already written about: Robert Browning. I felt that if I were going to spend that much time and that much energy on a project, I wanted to be studying a person who was immensely bright, powerfully intellectual, and deeply religious-though not necessarily in a denominational way. I came away from that scholarly experience feeling as if my own spirit had been richly nourished.

We must not narrow ourselves in what we read. There is so much good and great literature beyond Western literature, including literature from India, Asia, and of the Middle East. For example, I’ve been reading the Qur’an lately. Wonderful editions of the Qur’an are available with great notes. I have become more aware of the spiritual foundations of the descendants of Abraham who are now very important on the international scene.

I’ve read works by other non-Western authors and have been moved by their insights and perspectives. Of course, what education does is to give us new eyes and new perspectives. For example, it’s instructive for us to read about our U.S. history from the point of view of Native Americans. It is valuable to know about the colonialism from the point of view of the colonized as well as the colonizers.

But whatever we read we must realize we don’t have the whole story. Modestly, as Will and Ariel Durrant would suggest, is the first requirement of reading and writing history.

Woods: Who are some of the academic-setting mentors you have most appreciated who have exemplified what a “disciple-scholar” should be—those who you think model the scriptural injunction to “seek learning by study and also by faith” (D&C 88:118)?

Shumway: there were many. One of my great teaches at BYU-Provo was Bruce Clark, who taught literature. He was a grand, noble human being with a great voice, and he could read poetry to make you feel like the ground was shaking underneath your feet. He was a great mentor to me.

And among my fellow students there, I think of Jeffrey R. Holland, who has a cerebral quality about his approach to scripture, life, and teaching that is extremely refreshing. It doesn’t come across as pedantic in any way. I am uplifted and strengthened by the way he uses language.

Of course, I naturally think of Elder Neal A. Maxwell, Elder Dallin H. Oaks, and Elder Russell M. Nelson. These are men of great intellect who have studies widely, who are models to me. The scholarship of the gospel and the scholarship of the world as Eder Maxwell would insist must meld and blend. He referred to it as a necessary “bilingualism” all LDS scholars must achieve. You have to be bilingual in the language of scholarship and the language of the gospel.

Woods: Your last comment reminded me of Elder Bruce C. Hafen’s statement that we must have our passport in Athens but our citizenship in Zion.

Shumway: That’s right, and Matthew Arnold put it another way. There needs to be a blending of a strictness of conscience and spontaneity of consciousness. Ti’s where Sinai and Olympus come together.

Woods: In your estimation, what does it mean for a person to be truly educated?

Shumway: That’s a loaded question in a way. Becoming educated is exactly that. It’s becoming. It’s a process. And it has to do with attitude. It has to do with the desire to know. It has to do with continually learning. It has to do with a reading life. We talk about one’s prayer life or religious life. I think a person has to have a reading life, something that is essential to becoming a truly educated person.

More than that, becoming educated has to do with the attendant increase in the individual’s quality of character. Learning must be linked to Godlike character development to be widely read and widely traveled but lacking in fellow feeling and the love of God and His children constitutes tragedy. One of the great ironies is that many artists and intellectuals who have given their energies to creating beauty and discovering truth are themselves morally deficient. Truth and beauty are still external to them. They are conduits, not repositories. What intellectual and creative gift passes though them but for whatever reason does not grow into moral fiber. Pride, self-sufficiency, and the three comprehensive lusts—for acclaim, power, and sex—overwhelm them. Goethe’s Faust is a prime example.

Woods: As a follow-up question, what do you think are some of the greatest obstacles to becoming truly educated?

Shumway: Besides immorality and dishonesty, there are obviously a number of obstacles to the process of becoming educated. One of them certainly is our society’s vast “play culture,” from incessant sports and TV to video games and movies. We are so “anxiously engaged” in amusement that we fill our thoughts and our calendars with activities that keep us away from serious thought and mind improvement. Similarly, the drive for more and more material possessions keeps us poor intellectually and spiritually poor. We become victims of a self-satisfied, narrow provincialism that can snuff out curiosity and harden our opinions into prejudices. There is a provocative Tongan saying that wars against the dangers of a “small fish” perspective. “The lokua [a tiny reef fish] thinks his tidal pool is the vast ocean.

Woods: It has been over a decade since you were inaugurated as the eighth president of BYU-Hawaii. Let’s go back to November, 18, 1994, when you were given a charge by President Howard W. Hunter to find better ways to help students learn and to inspire the faculty so they facilitate student success in learning here and throughout their lifetimes. What are some of the things you have done during the past decade to increase student learning and to inspire your faculty?

Shumway: Some of these things have to do with what we’ve already talked about. First, we try to help our faculty become sensitive to different ways of learning and not to judge students by their accent or by their lack of experience. Actually, our students have an amazing impact on our faculty. They have wonderful stories about conversion, suffering, faith. The important things for faculty are awareness, sensitivity, and compassion for our students, for their origins, for their brightness, their potential—and the fact they are the “chosen” of their generation.

We also try to put together a curriculum that is not prejudicial or in favor strictly of Western constructs and culture. We encourage our faculty to learn about the countries from which students come and to travel there. Right now we’re interested in projects that will take the faculty to these countries as mentors for students going back home to do internships.

Also, we have overhauled the entire curriculum giving us stronger programs in General Education and in various majors. We have increased the numbers of students who complete their degree. Five years ago we were graduating about 300 students a year. Most of them had excessive hours—sometimes thirty or forty hours beyond what was required for graduation. We were restrictive in accepting transfer credit. Many majors were overloaded with requirements. We trimmed all of that down to a 120-hour, four-year curriculum. With General Education requirements, major classes, religion courses, and eighteen to twenty hours of elective credit, students can still graduate in 120 hours. We can say to students that if they stay on task, taking fifteen hours a semester, we guarantee that they can graduate in four years. Now, that doesn’t mean we don’t have flexibility to allow them to take more, but it means that we graduate more students faster.

Since the beginning of the school, the return of our international students to their home areas to build up Zion has been at the core of our mission as a university. We have given new impetus and energy to that mission in our efforts to create for them a “culture of returnability.” That is, from the moment of their recruitment and admission until they graduate, these students receive the mentoring and encouragement to return.

An international internship program has been put into place to allow students, after completing 80 to 90 credit hours, to return to their countries as interns, to work in settings that allow them to reconnect with their home economy and to establish networks with local alumni and businesses. Over 130 international students a year take advantage of this internship program. Significantly, it is almost entirely funded by donors who are committed to help our students return. Also a new placement office has been created and staffed with a director and internship coordinator to help facilitate the goals of returnability.

Woods: You are president of the most ethnically diverse school per capita in the United States. With that setting in mind, I was intrigued with the charge that President Howard W. Hunter gave you at your inauguration especially when referred to this campus a “laboratory for living.” I was aware of President Marion G. Romney referring to BYU-Hawaii as a living laboratory. Anyway, President Hunter charged you to find better ways to allow the diversity of cultures from which students come an to which they go to be an effective and important part of the educational resources of this campus. My questions are along with what you’ve just said: What are some of the other ways you consider BYU-Hawaii a living laboratory? And in what ways does the cultural diversity serve as an educational resource?

Shumway: The “living laboratory” phrase comes from Elder Romney in his address at the dedication of the Aloha Center in 1973, in which he says that we are a living laboratory in which the teachings of the Master Teacher will be infused in our student body in such a way that the campus will become a model for the whole world; and that what we do in a small way on this campus, the world must do in a large way if we’re ever to have peace on earth. That’s the context. So BYU-Hawaii is a living laboratory where people of many cultures experience a transformation, where they shed prejudices, misunderstandings, and historical baggage, if you will, and lean about the world from their fellow students.

A case in point: a young man came here from Korea whose father was conscripted into the Japanese army. The father hated the Japanese and taught his children to hate them. The young man came to BYU-Hawaii, where we have a significant number of Japanese students. He wondered before he arrived, “Am I going to fit in over there? I hope they don’t force me to mingle with Japanese.”

He came anyway, and in a short time, his best friends were Japanese. He liked them so much that he decided to take courses in the Japanese language. He became fluent in Japanese and ended up being a Japanese guide t the Polynesian Culture Center, where he took Japanese tourists around telling them about Polynesia and speaking to them in their own language. He told me, “My life has transformed. I came with a certain mindset. I now have new eyes. My life and attitude are changed at BYU-Hawaii.”

In another instance, a new student from Utah called her mom the day after she arrived and said, “Mom, do you know what they’ve done? They’ve given me a roommate who can’t speak English! I want to go home.” Well, she stayed and loved it. Yes, we see some pain and consternation in the “laboratory,” but we also see a lot of learning as a result of students’ being put in a situation where they are eating, rooming, studying, and worshipping with people who have a different skin color, accent, or dialect and who eat different foods. As you can see, BYU-Hawaii is a laboratory. This is where we are gaining experience and learning—not only to tolerate each other and get along, but also to appreciate and love others across cultures. I’m also thinking of the Japanese student who became an expert in the Hawaiian chant and the Korean student who is a fine Tahitian dancer at the Polynesian Cultural Center.

A few years ago, Dr. Hazen Symonette, a consultant to a number of U.S. universities on race relations, visited BYU-Hawaii. She had heard about the campus’s diversity and was curious. Dr. Symonette told me later, she could hardly believe what she saw. The wide involvement and inclusion of all our students was amazing to her, in student governments, as well as the social and spiritual events on campus. She intended on a one day visit, but stayed four days. She went to a devotional, attended a ball, visited classes and, in the end, she told me there’s no place like BYU-Hawaii anywhere else in the United States. She said that many universities have what she calls ‘gilded mission statements” about diversity. But BYU-Hawaii walks the talk. It’s a living reality here.

The living laboratory idea is significant in that the gospel of Jesus Christ is at the center. The gospel is the overriding culture.

There are many element sin various cultures, including American culture, that people must discard when they join the Church. In fact, a Chinese, Cambodian, or Samoan probably doesn’t give up any more cultural things than an American does when any of them joins the Church. By “culture” in America, I’m talking about the “liberal” culture and the “party culture,” sports on Sunday, drinking alcohol, gambling, aggressive individualism and so forth—things that many people think of when they define America as the empire of indulgence. To move out of that into a gospel culture requires almost the same kind of jarring transformation for an American as for a person from Cambodia or China. In fact, for an international convert, in some ways it’s easier. We see this in China, for example. China is a communist country, but people over there are hungering for spirituality. They are yearning and eager for spiritual change, but unfortunately the invasion of American goods has tended to promote the indulgent side of our culture rather than the spiritual side, which is disheartening.

Woods: You mentioned that things work quite well when the gospel is at the center of bringing these cultures together. But what happens when people fall into the trap of sifting the gospel through their cultures rather than their cultures through the gospel?

Shumway: That may cause a problem for some. But in the end, it is quite easy to understand behavior in a gospel culture. Take the issue of violence. Some cultures allow wife beating and heavy spanking of children. It is seen as the husband or father’s role—the fathers’ responsibility. Not so in gospel culture. We have learned that a person’s trying to hide behind his culture or excusing bad behavior by pointing to his culture is best addressed in a straightforward manner.

Sometimes false history is an issue. For example, years ago, there were some fights between our Samoan and Tongans students. One perpetrator tried to minimize the confrontation by saying, “Well, we were just repeating history. Tongans and Samoans have always been enemies from the time Tonga ruled Samoa centuries ago.” Well, I pointed out that that was false history. Tonga and Samoa have been on good terms all these years. In fact, the present royal dynasty in Tonga, the Tu’i Kanokupolu (king, body from Upolu) descended from Samoan ancestors. The Samoans and Tongans have interacted peacefully and intermarried for years. The present king’s son Ma’atu married a Samoan princess, granddaughter of Samoa’s Head of State, Mālietoa.

I still cherish a moment in our home with students from Southeast Asia. They told of their conversion to the gospel and shared their testimonies. One student from Cambodia said, “I sit here tonight between two traditional enemies, a Vietnamese and a Thai. Cambodia as you know is sandwiched between these mighty people and has suffered intensely over the centuries from their aggression. But in the church and at BYU-Hawaii we are brothers and sisters. I feel perfectly safe. It seems like I represent all of Cambodia sitting between Thailand and Vietnam. I hope that lobe and peace will exist forever as I feel it tonight between our peoples.”

Sometimes certain cultures are so powerful that a student finds himself in a serious dilemma, whether to follow the dictates of his cultural conscience or his “gospel conscience.” For example, in Polynesia, if a man’s sister or her children makes a request, he feels duty bound to meet that request no matter what the cost or inconvenience. This, If I am a Tongan supervisor at PCC and I have a cousin whose mother is my dad’s sister, it means that anything have she has access to. And so the cousin comes and says, “Uncle, I really want to go to the luau and see the show tonight, but I don’t have any money.” I let him in, which is viewed by the PCC as an act of dishonesty, but in my culture, I’m absolutely obligated to help. I can’t say no. So in desperation I let go of one value to embrace another.

That’s why intermarriages can be very rocky unless the persons really understand each other’s culture. For example, the Asian wife may discover that their whole savings is gone because her Polynesian husband has withdrawn the money to buy airfare for his parents who wanted to go visit somebody. They called and said, “Get us tickets.” The husband could not say no. That’s just one picture.

Woods: Sounds like the gospel culture is the key. In 2005, we’re having the Jubilee Commemoration, which I know you have probably been doing a lot of reading about as a reflection of the last fifty years of the history of the Church College of Hawaii and BYU-Hawaii. If you were to project fifty years into the future, what do you see? What do you think BYU-Hawaii is going to be like fifty years from now, or what would you like to see? What do you envision in the future for this place?

Shumway: I’m not sure I can envision a physical university in terms of size, numbers of students, and so on. I think we are going to grow, and I think we are going to be more and more critical to the unfolding of the Restoration across the world. I truly believe the campus will continue to provide a model education for diverse people who come together in one faith, one Lord, and one baptism. I believe that BYU-Hawaii will be considered more and more as an ideal spot for the kind of education that will facilitate peace and harmony around the world. I believe that BYU-Hawaii will also continue to produce programs, faculty, students, and graduates who will be strong in the gospel, have strong testimonies, and have strong commitments to living the gospel. I believe that if the university and P”CC leaders will continue to leverage the amazing power of the original vision by President David O. McKay, which he has articulated in many ways, as well as follow the counsel of the living prophets the university will continue to increase its influence “for good toward the establishment of peace internationally.”

The work to do is gradually unfolding. We have just barely scratched the surface with China, Japan and India. I believe that BYU-Hawaii must maintain, along with the community of Laie and the Polynesian Cultural Center, the core leadership and the kinds of students who are fully committed to the gospel of Jesus Christ. It has to be focused on not only righteous intent but righteous living in actuality. I believe people who come here need to have a sense of vision, and they have to believe it. President McKay said that “no person should teach on this campus who does not have an assurance, not a mere belief, but an assurance that God has had His hand on this valley from the very beginning.” In other words, you have to embrace the vision. The vision of the campus, the vision of President McKay, has to become part of your own private vision if you are going to reach here and if you are going to be able to discern who these students are, what they mean to the Church, and what they are going to do in the world. I think he has laid the groundwork that will help BYU-Hawaii avoid becoming what other universities have become—that is, clones of each other in a world of indulgence, materialism, and mutated individualism that discards the need to engage in the kind of love and inclusion that we have here on this campus.

Woods: If you could write your own epitaph, what would you want it to say about Eric B. Shumway?

Shumway: One of the things you learn when you are working in a setting like this is that the Lord makes things happen. The worst thing you can do is try to take any credit for this or that. But I hope I can be one of the many who served on this campus who is considered to be a person who did his best. Whatever modicum of success there might have been, it is the way the Lord works—not just through me but through everybody. I do know that we all are on the Lord’s errand and we have great responsibility. And with that great responsibility, we have great accountability. Whatever I do professionally, I am going to have to account for it spiritually because Heavenly Father does not distinguish between professional and personal responsibility. It is all about serving His children and preparing them for eternal life.