Harvest of Faith in Abundancia

Kathy Kipp Clayton

Kathy K. Clayton, "Harvest of Faith in Abundancia," Religious Educator 6, no. 2 (2005): 117–128.

Kathy K. Clayton was a seminary and institute teacher in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where she was serving with her husband, Elder L. Whitney Clayton of the Seventy when this was written.

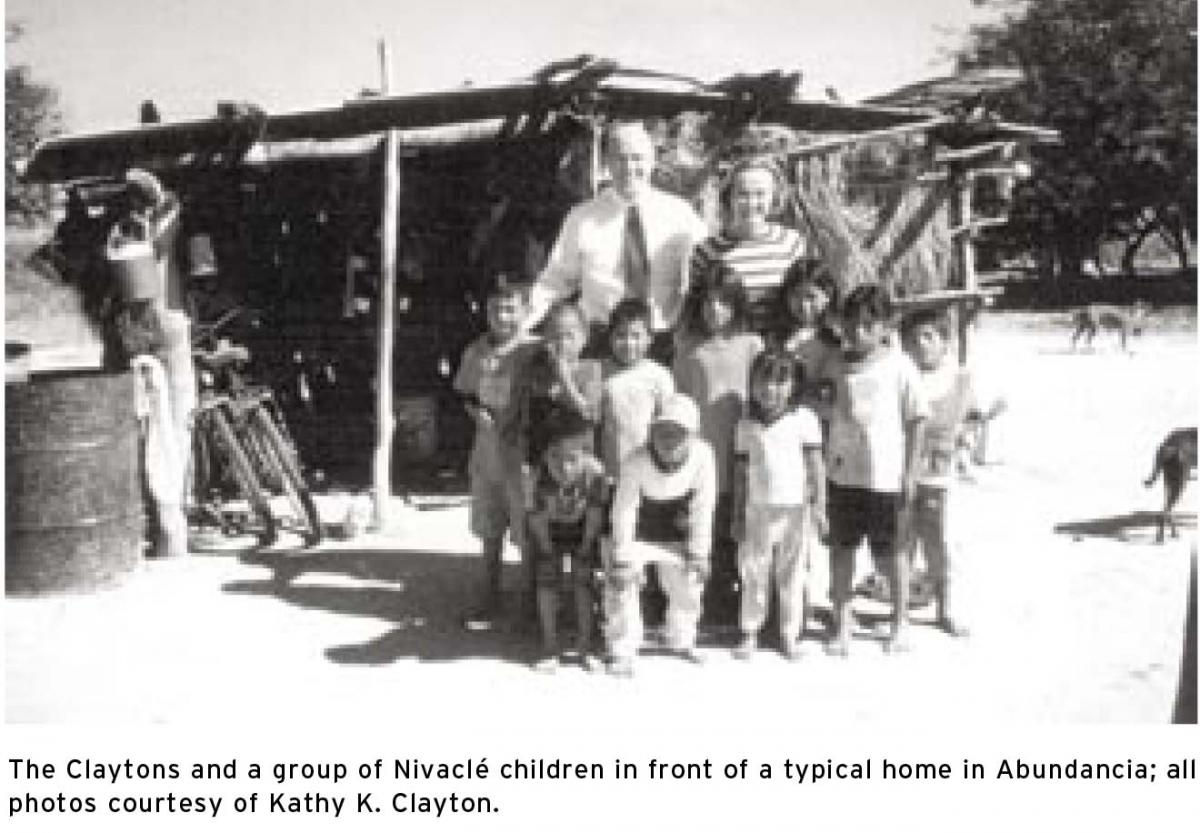

Our experiences in Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay while my husband serves in the South America South Area Presidency are varied and engaging. None, however, has been quite so thought-provoking for me personally as the first visit we made early in our tenure here during a tour of the Asunción Paraguay North Mission to a remarkable community of Nivaclé Indian Saints living in the sparse wilderness of northwestern Paraguay called the Chaco. The village of approximately three hundred Nivaclé residents is ironically named “Abundancia,” or “Bountiful.” The community is not abundant in any material regard, but inasmuch as all the residents of Abundancia are members of the Church, they live with the fullness of the gospel even in the absence of modern conveniences like running water and electricity. Their material possessions are sparse; their spiritual willingness of heart is abundant.

Mistolar, Paraguay—the Predecessor to Abundancia

A then-member of the Area Presidency of the South America South Area, Elder Ted E. Brewerton of the Seventy wrote of the beginnings of the community of Abundancia by recounting the origin of its ancestor, the village called Mistolar:

Mistolar had its beginnings in 1977. At that time, the Paraguayan mission president, Merle Bair, saw Walter Flores, a man from the deserts of the Chaco in Paraguay, on a television program in Asunción. President Bair felt impressed to find the man and share the gospel with him. In 1980, the missionaries located Flores. He was very receptive to the gospel message, and was soon baptized. Brother Flores’ testimony was so profound and clear, he knew he had to share the gospel with his fellow Indians. Several hundred joined the Church.

One group of some 214 Nivaclé Saints (formerly Chulupi), wanted to be free from

worldly influences and settled a large piece of land in an uninhabited, remote area of Paraguay. They named their settlement Mistolar. At first, they were totally self-sufficient in their gardening, hunting and fishing, and had little communication with other people. But the massive Pilcomayo River, between Mistolar and the northern border of Argentina, challenged their self-sufficiency and their faith.

One year as the snows of the Andes Mountains melted, the swollen Pilcomayo overflowed its banks and flooded Mistolar. The Saints were forced the move and they relocated ten kilometers away from the river’s edge. But even there, they were not safe. Another disastrous flood left their land more than knee-deep in water for a month. They lost the beautiful chapel they had built, their homes, their gardens, their clothing—almost everything they owned. But they still had their faith.[1]

Walter Flores, the First Convert

Walter Flores, that pioneering convert, recorded his recollections of the story of his conversion in a written testimony he prepared in January 2002:

President Bair, or President Oso, as he called himself, saw me in a television program. Immediately he said, “This has got to be a man who will work with me.” It was three days before he ended his mission. He was the first president here in Paraguay. He went right to my business (I worked with the Indians), and he left me his card and told me that he was the president of the mission. I didn’t know what that meant, so I just kept working.

Three days later, I was in my office. I was restless, so I decided to look at the business cards I had from people. I had a lot of them. The first card I saw was from President Bair. The card said “Mission President” and I wondered what kind of a calling that was. So I grabbed the phone and I called him. The president told me that I could go to his office anytime I wanted to. I found the office easily, and the president let me in. I saw a lot of people all dressed nicely in white shirts and ties. It made a big impression on me, so I said to myself, “It looks like I put my foot where few people come.” The president was a friendly man, and we spoke with one another for some time. He told me that he was going to send the missionaries to come visit me.

The missionaries came and they spoke to me about the gospel. I asked so many questions. I felt that I had found the truth, and I made my decision immediately. Ten days later I was baptized. I started to think about my brethren, the Nivaclé, because the gospel hadn’t arrived to them in the Chaco. Taking the gospel to them was a great goal of mine. We went to my people in Mistolar, and I gave my first testimony. They didn’t want to believe me at first, but they spoke with the missionaries, we worked together, and in fifteen days there were more than 160 who were receiving the discussions.

The first baptism was on Christmas Day, at an early hour. We dug a little pool, put a tarp inside it, and there was a long line waiting to be baptized. One baptism after another after another. They kept changing their baptismal clothes. The river wasn’t so white, so their white clothes turned brown. It was a very special day. This was in December of 1980. Four days later we had another sixty who were baptized. Then we baptized another forty. There were only a few left to be baptized, and then it would be everyone.

The Creation of Abundancia

The new Saints in Mistolar were perpetually subject to natural disasters. When the river overflowed its banks and flooded their village yet again, the Church helped them to relocate. Mistolar is a difficult two-day drive from Asunción. Concerned for the welfare of this faithful tribe of Church members, the Church purchased a plot of land near the pitted, two-lane Trans-Chaco Highway to allow the Nivaclé to esátablish a community in a locale that would be more accessible to Church leaders traveling from Asunción. Although still a difficult drive, the new village, called Abundancia, is seven to nine hours nearer to Asunción than Mistolar.

Eventually approximately one hundred people, about half of the residents of Abundancia, returned to their original home of Mistolar to reclaim the distance from worldly influences. The rest, approximately 150 people, remained in Abundancia to benefit from the increased access to more leadership, as well as educational and medical help from the Church and government personnel in Asunción. Due to the influx of neighboring Nivaclé and improved health care, the population of Abundancia has grown to approximately three hundred.

Today Abundancia exists as a dramatic contrast of a nearly unchanged tradition juxtaposed with modernity. The original community of Abundancia consists of a single mile-long dirt road lined on either side by primitive dwelling places made from mud, sticks, metal sheeting, and straw. The quiet community includes occasional armadillos and assorted stray dogs seeking to escape the stifling heat in the rare shade of a rusty donated picnic bench. Barefoot children of all sizes are dressed in colorful secondhand clothing with bold labels representing the donations of a globalized world.

At the east end of the road is the growing site of the tidy, beautiful buildings erected by the Church. Among the structures are the old chapel now remodeled to serve as a school, a simple brick dormitory to house the teachers imported from Asunción by the government, a small health center, and the Church’s humanitarian project 20031178—a promising new bakery. Most stunning is the magnificent orange brick chapel with its stunning white steeple dedicated last year. Those few buildings have the only electricity or running water in the village. On Sundays and Wednesdays, without either the bother or the benefit of clocks to prompt them, nearly all the residents of Abundancia walk, parade like, down the single road to worship together and, in the process, to indulge in the wonder of videotapes and flush toilets.

Issues Facing Abundancia

While the community of Mistolar has remained nearly entirely self-sustaining, the community of Abundancia has required and received more assistance. That increasing connection to a more modern world has introduced into the community compelling and complicated issues.

The Trans-Chaco Highway brings commodities and conveniences to the people of Abundancia from Asunción. That modernity clashes with their simple tradition and creates a cultural dissonance as they live with the gap. As the Nivaclé in Abundancia receive formal education from the Paraguayan teachers provided by the government in facilities constructed by the Church, the students are taught in Spanish. The preservation of their original Nivaclé language for future generations is uncertain. Furthermore, considering the formidable task of securing a dependable water source in that arid land and given the absence of a tradition of commerce among the Nivaclé, promoting self-reliance for the community is challenging. The concepts of money, commerce, and even farming are foreign to the hunter-gatherer people of Abundancia.

On May 9, 1991, Elder and Sister L. Vernon Cook were assigned to serve in Abundancia as Church welfare missionaries to help the Nivaclé develop clean drinking water and to learn to cultivate the soil. They described the challenge in a personal reflection paper Elder Cook wrote in May 1992: “We had thought that shouldn’t be too hard, for we had spent the past forty-two years developing irrigation water and putting new land under cultivation. We thought, ‘Let’s get started before dark.’ That afternoon was quite a day for us. Sure enough, there was a chapel at the edge of the road, and there was a trail which was shown on the survey sheet as a straight road but in reality was a trail that was somewhat straight but very rough in that you had to dodge deep ruts, tree stumps, and roots. What a challenge.” The Cooks’ service in Abundancia was a first step in a long, complicated journey to identify the best, most enduring ways to help the Nivaclé toward material self-reliance.

The physical conditions of that dry land continue to prove daunting obstacles to sustained and successful farming. According to Elder Cook, the average annual rainfall in Abundancia is only about twenty-three inches. Both during the tenure of the Cooks’ service and later, much has been done to seek to provide the community of Abundancia with water, but the problem continues to prove elusive. A basic system of collecting rain from roofs is impossible in a community where there are nearly no roofs. Commercial pumps have been difficult to maintain due to the minerals and salt in the well water. The quest for a dependable source of water continues to be paramount.

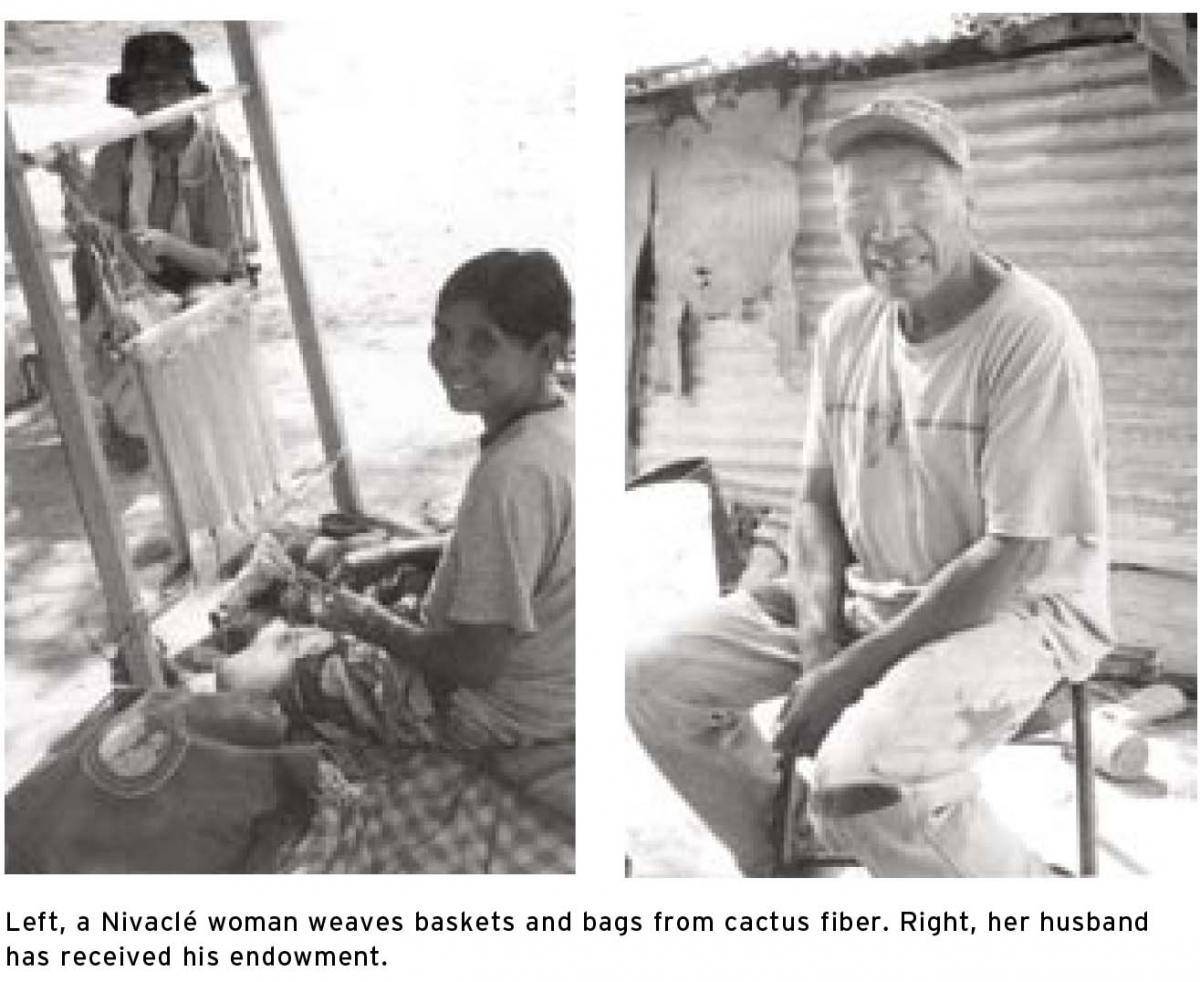

Abundancia and the Asunción Paraguay Temple

Elder and Sister Cook brought their vision and expertise to the people of Abundancia as well as their lasting love, a commitment that would eventually bless the lives of the Nivaclé Saints in an unanticipated way. Reflecting on their early service in Abundancia, the couple later wrote: “There we were, and they didn’t need our soil probe, plastic bags, etc., but what they needed was our love. Looking back, I must say, that element of love has set deep, both our love for them and theirs for us.” A decade later, Elder and Sister Cook were called to serve in the Asunción Paraguay Temple. Their persistent love for the people of Abundancia motivated them to seek ways to bring those faithful Saints to the temple to receive their endowments. Prompted by the encouragement of Elder and Sister Cook, the district president has been accompanying worthy members and families on trips to the temple, a few at a time each week, in a bus provided for by budget funds. Since few Nivaclé people read, and since they have only the Gospel Essentials manual published in their native language, the Nivaclé have no need for extensive purchase of printed materials. They also have no interest in regular branch social events, so the district president has elected to commit some of their budget allowance, accrued from nearly 100 percent sacrament meeting attendance every week, to temple trips for first endowments.

The Abundancia School

Among the triumphs during the Cooks’ missionary service was the opening of a small school in March 1992, the first month of the school year in the Southern Hemisphere. Initially the children shared the space for their academic instruction with Church services in the meetinghouse. With the completion of a beautiful new chapel last year, 161 Nivaclé children, ages five through twenty-five, have exclusive use of the old church building remodeled to serve as their school. The government of Paraguay sends pioneering young teachers to instruct the students and live in the dormitory built by the Church. In the context of the sparse Chaco, the school complex is famous. Other Nivaclé students walk or ride their bicycles up to eight kilometers daily to benefit from the well-organized program that includes the distinction of offering classes up to the ninth grade.

On my visit to Abundancia in February 2004, I admired both imported and Nivaclé workers putting the finishing touches on the refurbished church building with recycled windows, reused lumber, and discarded fixtures brought from other church buildings in Paraguay. Javier Vitale, the Church’s Paraguay Country Service Center manager, had committed his remarkable vision and expertise to providing worthy, functional facilities for the children. Everything looked promising, but I was struck by the conspicuous absence of desks and chairs. Consistent with Southern Hemisphere calendaring, classes were scheduled to begin the following Monday, with the humble expectation that the students would simply sit on the floor. Furniture was promptly assembled from other locations and delivered to Abundancia to enable those grateful students to begin their school year seated at desks.

Later that Monday, I wandered down the single dirt road lined on either side with multigenerational residents of Abundancia and their assorted shelters. I stopped to visit with a bevy of smiling, shy, teenaged young women who were sitting shoulder to shoulder on a rusty picnic table in the dusty summer heat with their bare feet resting on the bench. They had been watching me with sidelong looks evidencing friendly curiosity. With the help of one of the few Abundancia residents who spoke Spanish, I sought to engage those pretty, giggling girls in conversation. After years of both formal and informal association with young women, I felt immediately close to those young women, who were in so many ways like all others. Their beaded necklaces, donated Old Navy t-shirts, and girlish whispering were familiar, but the translation from my imperfect Spanish to a Nivaclé interpreter’s imperfect Spanish to their exclusive language of Nivaclé created a gap between us. Nevertheless, I sought to supplement our connection with the nonverbal help of eye contact and a smile and proceeded to trust my earnest interpreter to provide us a linguistic bridge. I learned that those young women had come from Mistolar, the parent community of Abundancia, to stay in Abundancia Monday through Friday to benefit from the unique ninth grade class offered at the new school.

I began, “What do you like most about school?” Having previously spoken with the engaging young teachers who were already on location and moving into the dormitory from Asunción, I had been assured that all the students liked school. “Why wouldn’t they?” those teachers asked me. “They are learning.” The students likely didn’t understand the potential ramifications of their educational opportunities, but their lack of discipline problems and eager interest in learning revealed a desire to be in class.

The shy young women avoided my eye contact and exchanged glances and giggles. I suspect they expected and probably hoped I would go away and allow them to observe me from afar, but I outlasted them. I was eager to learn from their response. The bravest among them, as a spokesperson for the group, finally offered a single, certain answer in a voice that was quiet but confident: “Spanish.” Perhaps that reluctant spokesperson revealed in her sure answer her own sense that learning Spanish may be, for her and for others like her, a key to the future.

For the young people who function as the first bridges to new cultures, there is always the profound challenge to embrace a new, dominant language and culture without parting entirely with the old. Young people like her are in a difficult position that requires extraordinary balance and flexibility to enable them to welcome a new way of speaking and living without losing the precious expressions and traditions of the past.

“Who Is My Neighbor?”—Abundancia as a Community

An unusually tall Nivaclé man with a welcoming grin beckoned me next door to chat with his family group, who were seated in a casual circle outside their home on assorted second-hand aluminum lawn chairs and small blankets spread on the dirt. His wife was meticulously spinning fiber from local cactus into thread, then weaving the scratchy fibers on a handmade loom into intricate patterns in baskets and small bags. The determination and ability of women to create beauty seems to be persistent and universal. Her husband had lived for a season in Argentina in an attempt to earn money for his family and had learned some Spanish. He was eager to practice. Besides the children of all ages who were surrounding us, the family includes an older son who served a mission in Uruguay and is now working on a neighboring farm to help provide for the family. When I asked the father how many children they had, he was slow to answer. Trying to be more specific, I pointed to the amused young faces encircling us and asked which were his sons and daughters. He was slow to distinguish his family from the rest.

The district president, and later Nelson Dibble, the CES director for Paraguay and a thoughtful student of the community of Abundancia, explained to me that the Nivaclé concept of family is very inclusive. They care for each other—literally. As a close community, they all belong to each other. It’s not that their ability to do arithmetic is halting, but they seem to think in terms of geometry rather than arithmetic. Their notion of a family is not a family line but rather a community circle with everyone having a space within. If a baby cries, the nearest nursing mother feeds the baby; if a child needs disciplining, the nearest attentive parent offers the correction. The residents of Abundancia don’t seem to engage in any self-scrutiny regarding “Who is my neighbor?” They tend whoever needs tending with no apparent regard for whether that person appears on their home teaching list as a formal assignment.

Convergence of the Past, the Present, and the Future

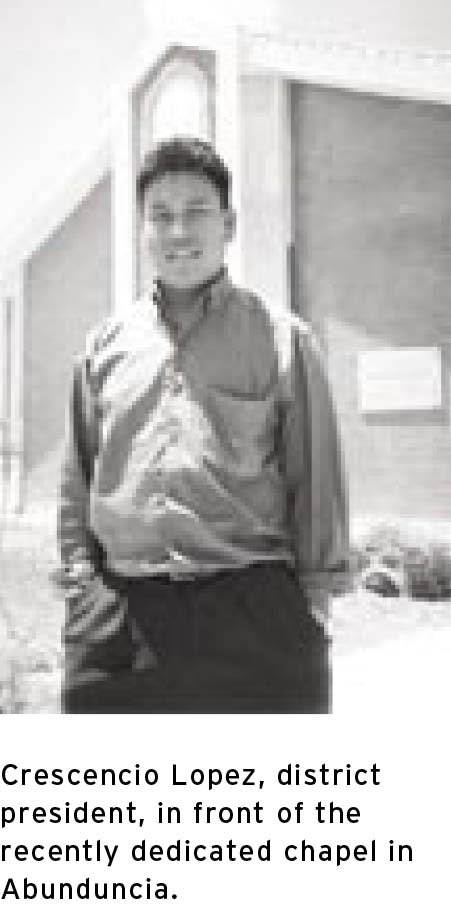

Among the few residents of the community fluent in Spanish is the young district president, Crescencio Lopez, one of five recently returned missionaries in Abundancia. President Lopez spoke almost no Spanish before his service in the Paraguay Asunción Mission. The father of President Lopez was among the original converts with Walter Flores. The family lived in Mistolar until the time of the flooding. At age five, President Lopez moved with his family of four brothers and two sisters to settle and remain in the newer community of Abundancia. President Lopez will complete his ninth grade and final year at the Abundancia school this year.

When I asked President Lopez if it had been difficult to return to Abundancia after his mission, he hesitated and looked at me with a puzzled expression. Assuming I had asked the question poorly, I rephrased it and tried again, “After you had lived two years with things like electricity and running water and box springs and mattresses, was it hard to leave those conveniences?” He understood linguistically but not emotionally. “Sister,” he patiently responded, “when missionaries complete their service, they are happy and eager to return home. Abundancia is my home.”

My next question was obvious. “President, what do you especially love about Abundancia?” I could hardly write quickly enough to record his enthusiastic response. “We have a church and a school. I want to teach in that school. My parents, my family, my people live here. Most of the children who are born here live here their whole lives. Our life is peaceful.” Having affirmed enthusiastically his affection for Abundancia as it has been for years, President Lopez proceeded to express something of the complicated tension that inevitably exists between preserving the status quo and embracing growth, which implies change.

He continued in another vein: “Our community is becoming more beautiful still. We have a health center now, with a member of our group who has traveled to Asunción to study medicine. The Church has built for us a bakery and taught us to bake bread. Others come to Abundancia to buy our bread and to enjoy our beautiful new buildings.”

The President proudly took me to tour the bakery recently completed as a Church Humanitarian Service project. I opened the door adjacent the bright plaque that read “Servicios Humanitarios Proyecto No. 20031178” to find a calm Nivaclé man patiently awaiting the arrival of local residents and occasional customers who would wander in from surrounding villages. The bakery is an impressive curiosity and attracts, via word of mouth through the Chaco, interested and hungry neighbors. That young man carefully accepts Paraguayan coins in exchange for baguettes cut into six-inch segments, bagged in plastic, and displayed on metal shelves.

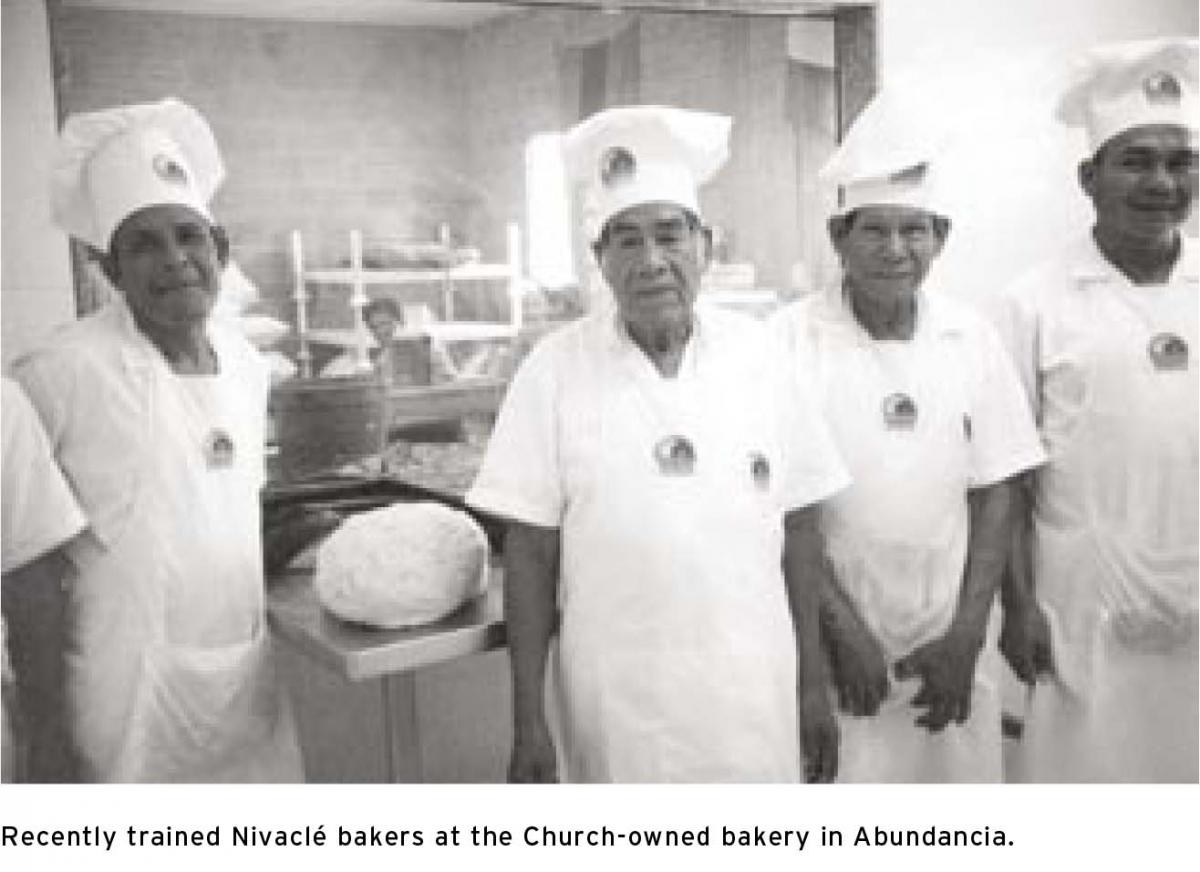

The adjoining room houses a multi-shelved electrical baking unit with its racks perpetually filled with uniform loaves of French bread. In a third room, newly trained bakers, dressed in white outfits from tall bakers hats to rubber-soled shoes, all hover over a grand lump of elastic dough and pound it into the proscribed shape. All of them pool their physical resources to pummel that massive lump of promising dough. Formal matters of modern commerce are new considerations for the Nivaclé, who have been hunter-gatherers for generations. Unfamiliar with any concepts of formal commerce, those workers simply patiently wait for more supplies to be delivered when the flour runs out. With no previous experience with business management, they have no understanding of the relationship between profit and expense.

I concluded my February visit to Abundancia where I had begun—in the tidy, tiled office of the district president in the magnificent new meetinghouse. In response to my prompting, President Lopez, that characteristically peaceful Nivaclé leader, offered his final comments regarding his remarkable community. Protected under the glass covering his simple desk were photos of members of his community in front of the Asunción temple. President Lopez noted, “They return from the temple happier. Of course we have challenges, but before our people had been to the temple, we suffered more. With the help of the temple endowment, we understand the purpose of life much more fully. Most of these people will likely attend the temple only once in their lives, but it is enough. They accept callings to serve in the Church and they work at them. They feel happy.” The community of Abundancia is a complicated but promising microcosm of the meeting of the old and the new, the past and the future.

I left the impressive Church building followed by a family of kittens, a few stray dogs, and several constantly curious children. With one last look at that promising edifice, President Vaughn R. Anderson of the Paraguay Asunción North Mission appropriately noted, “This chapel has served as a symbol of godliness.” Like the spires on the church, the Nivaclé of Abundancia will continue to reach heavenward.

Notes

[1] Ted E. Brewerton, “Mistolar: Spiritual Oasis,” Tambuli, September 1990, 11–12.