A Viewpoint on the Supposedly Lost Gospel Q

Thomas A. Wayment

Thomas A Wayment, "A Viewpoint on the Supposedly Lost Gospel Q," Religious Educator 5, no. 2 (2004): 105–115.

Thomas A. Wayment was an assistant professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University when this was published

Over the past few years, it has become increasingly obvious that apathy toward the issues raised by biblical scholars is costing believing Christians a great deal more than we may have anticipated. Of major concern for scholars the past two centuries is the issue of the compositional order of the New Testament and the literary relationship among Matthew, Mark, and Luke—commonly referred to as the synoptic Gospels. The theories presented by scholars are, in some fields of New Testament studies, becoming more controversial, more hostile to faith, and more reform oriented. One such field of study considers the issue now known as the “synoptic problem.” The “synoptic problem” refers to the discussion surrounding how the authors of the synoptic Gospels—Matthew, Mark, and Luke—used and referred to one another in the process of writing their own accounts.

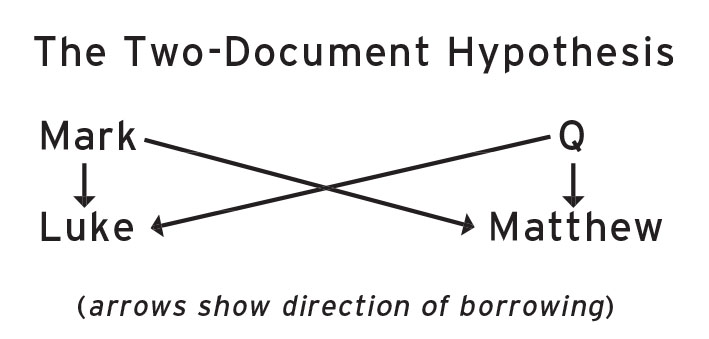

Scholarship is quite polarized over how to resolve this issue. Those who advocate a “two-document hypothesis” have heavily influenced the debate among scholars concerning how the Gospels were written and what sources were used in their composition.[1] Their theory is that the Gospel of Mark was the earliest to be written and that it was subsequently used and borrowed from during the composition of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. This theory can adequately explain how the synoptic Gospels contain much of the same material, but there are also significant portions of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke that are not found in Mark. After looking at those passages where Matthew and Luke contain the same account or saying, for which there is no corresponding account in Mark, scholars concluded that Matthew and Luke borrowed from a second earlier source that has been dubbed “Q,” from the German Quelle or “source,” and hence the idea of two source documents, Mark and Q, from which the “two-document hypothesis” derives its name. The following visual depicts the “borrowing” as reflected in the two-document hypothesis:

The Two-Document Hypothesis

The compositional theory proposed by many scholars of the New Testament is that Matthew and Luke each independently borrowed a significant amount of their text and order from Mark and that, interspersed between their borrowings from Mark, each evangelist added passages from the theoretical document Q. Scholars determine Q passages by comparing those instances where Matthew and Luke have a verbatim or nearly verbatim parallel between them that is not recorded in Mark. According to the theory, Q can be determined only when Matthew and Luke have copied from it directly and have not altered the saying substantially.

A discussion of Q may appear to many to be merely an academic enterprise, the work of scholars, and to go beyond the realm of faithful scripture searching. In its initial stages, Q was nearly a purely academic enterprise. Today, however, conclusions drawn from it are influencing the faith of thousands and altering the way the New Testament is taught and preached throughout the world. As Latter-day Saints, we have been relatively unaware of this heated discussion among scholars and have often viewed their proceedings as suspicious or beyond the realm of interest.[2] We are rapidly losing ground in this discussion, and, without some opposing influence, scholars may soon declare the two-document hypothesis a proven fact.[3] The issues that this article seeks to address are whether the two-document hypothesis conflicts with Latter-day Saint viewpoints of the New Testament and what ramifications the study of Q could have, if accepted, on our understanding of Jesus of Nazareth.

A Defense of Q?

The idea that the Bible may be incomplete can immediately be defended on the grounds of the eighth Article of Faith, which states, “We believe the Bible to be the word of God as far as it is translated correctly; we also believe the Book of Mormon to be the word of God.” The Latter-day Saint belief that the Bible is not infallible and that errors have crept in because of misinformed or intentionally erroneous translations would facilitate our agreement with biblical scholars who likewise argue that the Bible has been corrupted during the process of transmission.[4] The Q theory, however, is much more than the simple corruption of scripture and mistranslation of texts. Q theorists suggest that the authors of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke knowingly altered and enhanced the teachings they received from Q and Mark. The work of the Evangelists, they propose, as well as their various focal points, can be determined by how the Evangelists changed the materials they received and what materials they added to Mark and Q.

In its most basic form, Q studies have nothing to do with mistranslation but instead lead into a discussion of the tendencies of each author and their different treatments of received traditions. Such a use of biblical traditions could be justified using the model of the Book of Mormon and the way in which Mormon and later Moroni edited the traditions from the large plates of Nephi and the book of Ether. We cannot entirely object to what Q scholars are saying about the way in which Matthew and Luke have handled the traditions that were passed on to them; in fact, we would have to learn to accept the idea that the authors of Matthew and Luke were second-generation Christians who edited the texts of the previous generation and were not eyewitnesses themselves.[5]

Q may also be defended on the grounds that it contains the words of Jesus in their earliest form, and its composition therefore reveals an interest by the earliest disciples of Jesus to record accurately His sayings. One would expect, from a logical standpoint, that the disciples of any great religious leader would collect and gather the sayings of their master immediately upon his death or even during his lifetime. It could be argued that Q represents just such a document. The difficulty with this thesis, however, is that the inner logic of the theoretical Q document would suggest otherwise. Using only those passages contained in Q, scholars have proposed that the Jesus of Q was a wandering teacher of wisdom who did little to cultivate the master-disciple relationship. The proposed Jesus of Q also had no expectations of a future church or kingdom on the earth and did little if anything to train His disciples for His impending death. Therefore, by the logic of Q, could we really suggest that Jesus had a devout group of followers who worshipped Him and who would have been careful to preserve His teachings? The contents of Q suggest that Jesus had very few personal disciples, and therefore it would be difficult using Q alone to suggest that anyone would be greatly interested in collecting the sayings of Jesus and preserving His name and authority within that collection.

Challenges to Q—The Sermon to the Nephites

One of the founding principles in determining Q and which author of the New Testament most accurately preserved its contents is the belief that the Sermon on the Mount was a composition by the author of the Gospel of Matthew. As is well known among readers of the New Testament, Matthew and Luke contain two very similar sermons: the Sermon on the Mount (see Matthew 5–7) and the Sermon on the Plain (see Luke 6:20–49). The large overlap in wording and order of passages has led to the conclusion that many of the passages of the Sermon on the Mount or Plain were originally contained in Q. By Q’s definition, this would be a logical conclusion. The author of the Gospel of Matthew, in this way of thinking, is, in reality, the author of the Sermon on the Mount and qualifies for the honor of having compiled one of the most memorable discourses in history.

This view, however, faces a considerable challenge in the Book of Mormon through Jesus’s Sermon to the Nephites (see 3 Nephi 12–14). Scholars argue that the Sermon on the Mount is a composition from the late 70s AD by a second-generation Christian believer. They maintain that Q contained no distinctly organized sermon and that perhaps the Gospel of Luke has given us the most accurate depiction of what Q contained relating to this sermon. The parallel Sermon to the Nephites, however, was given shortly after the death of Jesus. The similarity of wording suggests that the Sermon on the Mount was composed no later than a few years after Christ’s death, not forty years later as Q scholars maintain.[6] Latter-day Saints also believe that the composition of the Sermon on the Mount was made during Jesus’s own lifetime and that the sermon was actually delivered to an audience of His disciples, although this thinking cannot be absolutely “proven” in a scientific sense.

Evangelists as Editors and Authors

Q in its simplest form raises serious doubts concerning our traditional understanding of who the Evangelists were and what their work consisted of. We would not be surprised to learn their views that the disciple Matthew did not personally pen the Gospel of Matthew or that the Gospel of Luke was penned by another one of Paul’s traveling companions whose name has now been lost, but we would be surprised to 108 read that the authors of the New Testament had complete freedom in composing their books and in altering the words of Jesus. Those who advocate Q claim that the earliest historical collection of Jesus’s life was devoid of narrative, told no miracles, and contained only short random sayings from Jesus Himself.[7]

Q scholars propose that the Evangelists used this collection of sayings, or logia, liberally and that neither Luke nor Matthew showed any great respect for its order, or wording, or tried to transmit it in its entirety. Theoretically, Matthew and Luke used this source freely in their composition and created narrative settings of their own accord, independently inserting passages from Q into their framework, which they had adapted from Mark. What type of record was this that contained the words of Jesus but for which a second-generation Christian author had little, if any, respect for as a valid representation of the life of Jesus? Scholars are arguing with more vigor that the Jesus of Q is the Jesus of history and that the Jesus of the Gospels is the Jesus created by the Church. If the Q theory were indeed valid, then this viewpoint would need to be seriously considered.

An Evolutionary Model

The theory of Q works on an evolutionary model of history, in which the most primitive and concise records were the earliest, and then later authors and editors expanded the history to adapt it for their own circumstances. Q and Mark, the most “primitive” of the Gospels, were the first to be written in this sequence, and the longer Gospels of Matthew and Luke are seen as the final product in the evolution of the Gospel genre. Scholars have argued that Matthew and Luke went through various stages or recensions and that the version we now have is the one that was finally accepted by the church. Such an understanding of textual history may be acceptable to some scholars, but there is an entire stratum of textual critics who defend the position that scribes, especially in the earliest period of textual transmission, tended to delete portions of text rather than expand and enhance.[8] The normal work of the scribe in correcting the text and harmonizing it to the other New Testament texts is easily identifiable through a study of the textual variants of the New Testament. The opposite, namely the removal of large portions of text, is also easily identifiable in the study of the New Testament. A few examples may suffice:

1. In John 5:2, Jesus performs a miracle at the pool of Bethesda in the city of Jerusalem, but John 6:1 states that “after these things Jesus went over the sea of Galilee,” a distance of nearly two hundred miles. The temporal connective “after” suggests that after Jesus did X he did Y, but the two scenes are very different from one another, and it appears that the intervening explanatory text or travel narrative has been removed.

2. In Acts 20:35, we have the statement, “Remember the words of the Lord Jesus, how he said, It is more blessed to give than to receive,” yet this saying does not appear in any of the canonical Gospels.

3. From an even earlier period, Paul taught the Thessalonian Saints ”by the word of the Lord, that we which are alive and remain unto the coming of the Lord shall not prevent them which are asleep. For the Lord himself shall descend from heaven with a shout, with the voice of the archangel, and with the trump of God: and the dead in Christ shall rise first: then we which are alive and remain shall be caught up together with them in the clouds, to meet the Lord in the air: and so shall we ever be with the Lord.” (1 Thessalonians 4:15–17). The Apostle Paul stated in the preceding text that these words originated with the Lord Jesus Christ, yet they are nowhere to be found in the Gospels of the New Testament.

The evidence of the Book of Mormon teaches us that scripture also undergoes corruption through the process of deletions. In Nephi’s inspired account, he stated that “the book proceeded forth from the mouth of a Jew; and when it proceeded forth from the mouth of a Jew it contained the fulness of the gospel of the Lord. . . . Wherefore, these things go forth from the Jews in purity unto the Gentiles” (1 Nephi 13:24–25). Although not by any means an absolute statement on all textual variation in the New Testament, the Book of Mormon testifies that the text of the Bible would suffer from deletions but does not mention the proposed expansion of the text as proposed by Q scholars. The transmission process of the Book of Mormon also suggests that inspired records are created through inspired editorial condensation and that the longer text of the Book of Mormon was the earliest. Luke may have had just such a situation in mind when he states, “Forasmuch as many have taken in hand to set forth in order a declaration of those things which are most surely believed among us” (Luke 1:1). Like Mormon, Luke may be giving us an inspired and edited condensation of the traditions that he has received.[9] The evolutionary model should not confine us into thinking that all texts start out primitive and develop over time through the process of uninspired additions.

Ipsissima Vox Iesou—The Very Words of Jesus

An issue that needs to be raised is what relationship the proposed Q document has to the life and teachings of the historical Jesus. Scholars 110 fall into several camps on this issue, with essentially every nuance in between being advocated. The most immediate reaction to the evidence presented by those expounding the two-document hypothesis is that the words of Q most accurately reflect the words of Jesus. This is a logical corollary—if Q is proven to be correct—as Q bears greater chronological proximity to the life of Jesus. We should expect that the earliest accounts would have had access to eyewitness accounts and to those who had been in direct contact with Jesus Himself. If Q represents the most correct collection of the words of Jesus, then we should likely view the later Gospel compilations as confusions of the truth. The editors of Q, namely Matthew and Luke, would, therefore, be the generation of Christians who modified and altered the teachings of Jesus. Almost all additions to Q, unless a historically valid claim can be made for independent reliability, could be understood as alterations of the truth.

This way of thinking leads us to ask ourselves whether our reliance upon the New Testament Gospels is a matter of tradition or whether our reliance upon them as accurate accounts of the life of Jesus is based upon their truthful representation of the facts. Nearly everywhere, Christians today are bristling at the suggestion of such a question, and Q scholars are forcing a decision on the issue. Unfortunately, as believing christians we are losing the battle in this area, and our silence on this issue is permitting those who would construe things otherwise to gain precedence. For example, a recently aired special on the life of Jesus by Peter Jennings entitled The Search for Jesus retold the life of Jesus based on the work of Q scholars. Jennings presented for the first time on national television a documentary on Jesus’s life using Q as though it were in many instances a proven fact.[10]

We will never be able to “prove” the historical accuracy of the New Testament, but, as a corollary, it will never be disproved either unless substantial firsthand, eyewitness accounts are discovered. We might rely on the eighth Article of Faith to affirm our belief in the Bible or the testimonies given in the Book of Mormon, but these witnesses as well as those of the living prophets will never suffice to yield scientific proof. We need to be reminded that the New Testament is not without errors, and those who propose the two-document hypothesis need to be reminded that their proposal is at this stage a theory and that while Q scholars are attempting to reconstruct Christianity upon that new theory, it will always remain simply that, a theory with significant detractors.[11] Faith is not a science, and theory is not an absolute.

Separate and Competing Christianities

The “discovery” of Q has led to a belief that the Gospels represent types or communities of Christian believers and that those communities were in conversation and discourse with one another—for example, in the secondary literature anyone can read about Matthean, Markan, Lukan, and especially Johannine Christianity. Q scholars have proposed that the Gospels represent the work of these communities, and their various alterations to received traditions, namely Q and Mark, help manifest their doctrinal leanings and tendencies. Matthean Christianity is more oriented, for example, to issues of ritual purity, whereas the Gospel of Luke has an overt concern for poverty and the economic poor. This view obliterates the standpoint that all the authors of the New Testament were working within and toward the establishment of the Church left behind in the wake of Jesus’s death. The Church, many believe, developed over time and was the product of a dominant group that marginalized its opponents. Scholars have pointed to the conclusion that various early Christian heretical groups could be viewed as more ”orthodox” or more historically correct in their understanding of Jesus than those who ultimately triumphed and wrote the New Testament.

There are some points that we should consider before joining these people on the bandwagon. New Testament authors and modern prophets have taught concerning the Apostasy that enveloped the early church. Although we cannot fix the moment of the beginning of the Apostasy, we have traditionally ascribed it to the postapostolic era after the death of the first Quorum of Twelve Apostles. We believe that the Church was organized in the days of the Apostles and that Peter and the other eleven Apostles administered to the needs of the growing Church. Q would radically alter our portrait of the early Church and undermine our belief that Jesus left behind an organized religious community.

Those who advocate that Christian origins should be thus reconstructed often fail to notice that their proposed reconstruction is based on circular reasoning. All passages wherein Jesus overtly teaches, trains, and prepares the Apostles for His upcoming death either derive from Mark or do not originate in Q. Therefore, scholars dismiss those passages that have Church organization, or teachings concerning the future Church as late and secondary, but the criteria established by those scholars is the very reason that such evidence has been removed. Their judgment is circular at best because we cannot establish a theoretical document, one in which we have determined its contents, and then make negative statements regarding other traditions based on 112 what was supposedly not in that document. There is no scientific way to verify what was not in Q, and, in fact, if only one author quoted from Q, our methods of detecting Q passages would prove useless because Q passages are determined by verbal similarity between Matthew and Luke. If Luke or Matthew quoted independently from Q, we would never know it. Therefore, many of those passages that speak of Church organization, the training of the Twelve, and what the disciples should do after Jesus’s death could derive from Q if they could be shown to not derive from Mark. In reality, only sixty-eight passages are ascribed to Q, but the number could be much greater since Q can be detected only when Matthew and Luke both quote the same passage nearly verbatim.[12]

Paul

Although Paul might first appear to be beyond a discussion of Q, he is not. Paul is our earliest author in the New Testament, and he wrote contemporaneously with the theoretical Q. Therefore, these two sources for the study of the New Testament should be viewed on equal footing. In the era after the “discovery” of Q, scholars began to take a second look at Paul and his familiarity with the traditions of Jesus’s life. As is well known, Paul tells us almost nothing of Jesus’s ministry or of what Jesus taught.[13]

Two views of this phenomenon have emerged; either Paul did not tell of the traditions of Jesus’s life because they were so familiar to his audience or he was unfamiliar with them because they had not been established by his day. Although not unanimously, Q scholars tend to favor the latter possibility because it lends tacit support to their theory that Christianity was being invented and shaped by the events of the 50s, 60s, and 70s. Paul, in this way of thinking, was a Christian maverick who saw things quite differently from the authors of the synoptic traditions and who was largely responsible for imposing on the early Christian communities a sense of church and central organization.

Conclusion

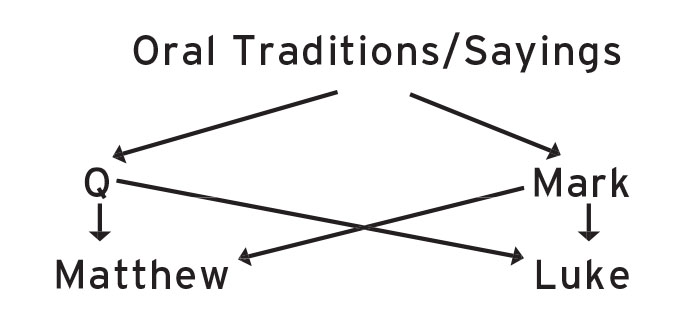

Q has become many things in our day, probably most of them unanticipated by its original proponents. In reading the early literature on Q, scholars can sense of open debate and concern to establish whether the authors of Matthew and Luke had access to earlier written or oral traditions. The first generation of Q scholars debated whether Q was even a written tradition. Unfortunately, Q has become something unwieldy—a beast with a spirit of its own. Q scholars want to alter our understanding of who Jesus was and present to us a Jesus who did no miracles, did not anticipate His death, did not understand He was the Messiah, and did not leave behind an organized church. The Jesus of Q is essentially a scholar’s Jesus who wandered the countryside and taught using conventional wisdom. He had no power to save Himself, and He had no power to save others. Scholars call this the Jesus of history, whereas we worship the Jesus of faith. The following chart shows the directions of borrowing from Q and Mark by Matthew and Luke as proposed by Q scholars.

Oral Traditions/

Q studies face serious challenges both from within the ranks and from without. Significant work is being done that reconstructs the textual history of the New Testament using Mark as the first Gospel but without postulating a source such as Q. Others have gone back to the Augustinian hypothesis—that the Gospels were composed in their canonical order. While these arguments may appear too nuanced to be meaningful, the stakes are great. Silence on issues such as Q has permitted those who see things otherwise to have an almost unimpeded voice, which has led many to believe that a consensus is emerging. We as Latter-day Saints have a great interest in Christian origins, probably more so than most.

We do not object to the possible use of sources by the Evangelists, and we expect that if such sources were available to them in the earliest years of the Church, they would make good use of them. We object, however, to what is being said concerning the items that those early sources did not contain, and we openly question whether such a document actually existed. The problem lies not necessarily in Q but in what Q has become.

Notes

[1] The “two-document hypothesis” affirms that Matthew and Luke each used the Gospel of Mark as a source in composing their own Gospels as well as an earlier unknown source called Q from the German word for “source,” Quelle.

[2] A great deal of suspicion has surrounded the work of the Jesus Seminar, founded in 1985 by Robert Funk and currently located in Santa Rosa, California. 114 Q Mark Matthew Luke The work of the seminar focuses on ascertaining the origins and validity of all traditions about Jesus of Nazareth from His birth until AD 200. The participants of the seminar have garnered a great deal of criticism and suspicion because of their often countercultural theories and dismissal of many of Jesus’s sayings as inauthentic and secondary.

[3] This trend is hinted at by John S. Kloppenborg in Excavating Q (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2000), 11–54.

[4] This sentiment was recently expressed by John H. Vandenberg, “What Is Truth?” Ensign, May 1978, 54. He states, “We know that the Bible is a compilation of the available messages received by the prophets.”

[5] I see almost no way of maintaining the tradition that the author of the Gospel of Matthew was an eyewitness if the two-document hypothesis is correct. The only way that he could still be claimed to have any access to eyewitness traditions is through Q and the detection of the method in which he rearranges the material from Mark and Q.

[6] John W. Welch, The Sermon at the Temple and the Sermon on the Mount (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1990), 164–77.

[7] The one instance of a healing in Q is the healing of the centurion’s son (see Matthew 8:5–13; Luke 7:1–10). The account of the miracle itself, however, cannot be ascribed to Q because there is little, if any, verbal similarity in the account of the miracle. Q, by definition, contained only the request of the centurion and not the subsequent miracle (see John S. Kloppenborg, Q Parallels [Sonoma, CA: Polebridge, 1988], 48–51).

[8] Eldon J. Epp, “Issues in New Testament Textual Criticism: Moving from the Nineteenth Century to the Twenty-First Century,” in Rethinking New Testament Textual Criticism, ed. David A. Black (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2002), 17–76.

[9] This has been consistently pointed out by Q scholars, who note that Luke is referring to Q. It may also contain a broader perspective—that Matthew, Mark, and maybe even John had been written and that now Luke proposes to give his account.

[10] For the work of the Jesus Seminar, see note 2 above. Jennings has received substantial criticism for his decision to present the Jesus of Q as the accurate, unadulterated Jesus. For some of his responses and his impetus for completing such a project, see abcnews.go.com/

[11] A growing number of scholars are being won over to the Farrer-Goulder hypothesis, made most recently by Mark Goodacre, in The Case Against Q (Harrisburg, PA: Trinity, 2002).

[12] Kloppenborg, Q Parallels, xxxi–xxxiii.

[13] For a balanced discussion of what Paul knew and taught concerning Jesus of Nazareth, see Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, “Early Accounts of the Story,” in From the Last Supper through the Resurrection: The Savior’s Final Hours, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Thomas A. Wayment (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003), 401–21.